Scipionyx on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Scipionyx'' ( ) was a

''Scipionyx'' was discovered in the spring of 1981 by Giovanni Todesco, an amateur

''Scipionyx'' was discovered in the spring of 1981 by Giovanni Todesco, an amateur  In 1993 Teruzzi and Leonardi scientifically reported the find, which generated some publicity as it was the very first dinosaur found in Italy. The popular magazine '' Oggi'' simultaneously nicknamed the animal ''Ciro'', a typical Neapolitan boy's name, an idea by chief-editor Pino Aprile.Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2011) ''Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages.'' In 1994 Leonardi published a larger article about the discovery. In 1995 Marco Signore of the

In 1993 Teruzzi and Leonardi scientifically reported the find, which generated some publicity as it was the very first dinosaur found in Italy. The popular magazine '' Oggi'' simultaneously nicknamed the animal ''Ciro'', a typical Neapolitan boy's name, an idea by chief-editor Pino Aprile.Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2011) ''Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages.'' In 1994 Leonardi published a larger article about the discovery. In 1995 Marco Signore of the

The holotype of ''Scipionyx'' represents a very small individual, the preserved length being just 237 millimetres. In 2011 dal Sasso & Maganuco estimated its total length, including the missing tail section, at 461 millimetres. The specimen was not much smaller than known embryos or hatchlings of ''

The holotype of ''Scipionyx'' represents a very small individual, the preserved length being just 237 millimetres. In 2011 dal Sasso & Maganuco estimated its total length, including the missing tail section, at 461 millimetres. The specimen was not much smaller than known embryos or hatchlings of ''

Because the holotype is a hatchling of perhaps only a few days old, it is hard to determine the build of the adult animal but some general conclusions can be reliably made. ''Scipionyx'' was a small bipedal predator. Its horizontal rump was balanced by a long tail. The neck was relatively long and slender. The hindlimbs and especially the forelimbs were rather elongated. Dal Sasso & Maganuco considered it likely that a coat of primitive protofeathers was present, as these are also known from some direct relatives.

Because the holotype is a hatchling of perhaps only a few days old, it is hard to determine the build of the adult animal but some general conclusions can be reliably made. ''Scipionyx'' was a small bipedal predator. Its horizontal rump was balanced by a long tail. The neck was relatively long and slender. The hindlimbs and especially the forelimbs were rather elongated. Dal Sasso & Maganuco considered it likely that a coat of primitive protofeathers was present, as these are also known from some direct relatives.

The skull of the holotype is large, compared to the size of the body, and short with very large eye-sockets. This is largely due to its young age. Accordingly, the semi-circular

The skull of the holotype is large, compared to the size of the body, and short with very large eye-sockets. This is largely due to its young age. Accordingly, the semi-circular

The

The

The fossil preserves no traces of any skin, scales or feathers. In 1999

The fossil preserves no traces of any skin, scales or feathers. In 1999

The location where ''Scipionyx'' was found, in the Albian was part of the

The location where ''Scipionyx'' was found, in the Albian was part of the

genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nom ...

of theropod

Theropoda (; ), whose members are known as theropods, is a dinosaur clade that is characterized by hollow bones and three toes and claws on each limb. Theropods are generally classed as a group of saurischian dinosaurs. They were ancestrally c ...

dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

from the Early Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

of Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, around 113 million years ago

The abbreviation Myr, "million years", is a unit of a quantity of (i.e. ) years, or 31.556926 teraseconds.

Usage

Myr (million years) is in common use in fields such as Earth science and cosmology. Myr is also used with Mya (million years ago ...

.

There is only one fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

known of ''Scipionyx'', discovered in 1981 by an amateur paleontologist and brought to the attention of science in 1993. In 1998 the type species

In zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the species that contains the biological type specim ...

''Scipionyx samniticus'' was named, the generic name meaning "Scipio's claw". The find generated much publicity because of the unique preservation of large areas of petrified soft tissue and internal organs such as muscles and intestines. The fossil shows many details of these, even the internal structure of some muscle and bone cells. It was also the first dinosaur found in Italy. Because of the importance of the specimen, it has been intensely studied.

The fossil is that of a juvenile only half a metre (twenty inches) long and perhaps just three days old. Its adult size is unknown. ''Scipionyx'' was a bipedal predator, its horizontal rump balanced by a long tail. Its body was probably covered by primitive feathers but these have not been found in the fossil, that is without any skin remains.

In the guts of the fossil some half-digested meals are still present, indicating ''Scipionyx'' ate lizards and fish. Perhaps these had been fed to the young animal by its parents. Several scientists have tried to learn from the position of the internal organs how ''Scipionyx'' breathed, but their conclusions often disagree.

The classification of ''Scipionyx'' is uncertain, due to the difficulties of classifying a taxon known only from such a young specimen. Most paleontologists have classified it as a member of Compsognathidae

Compsognathidae is a family of coelurosaurian theropod dinosaurs. Compsognathids were small carnivores, generally conservative in form, hailing from the Jurassic and Cretaceous Periods. The bird-like features of these species, along with other d ...

, a family of small coelurosaurs

Coelurosauria (; from Greek, meaning "hollow tailed lizards") is the clade containing all theropod dinosaurs more closely related to birds than to carnosaurs.

Coelurosauria is a subgroup of theropod dinosaurs that includes compsognathids, tyran ...

, but the paleontologist Andrea Cau has proposed it may belong to Carcharodontosauridae

Carcharodontosauridae (carcharodontosaurids; from the Greek καρχαροδοντόσαυρος, ''carcharodontósauros'': "shark-toothed lizards") is a group of carnivorous theropod dinosaurs. In 1931, Ernst Stromer named Carcharodontosauridae ...

, a family of large carnosaurs

Carnosauria is an extinct large group of predatory dinosaurs that lived during the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. Starting from the 1990s, scientists have discovered some very large carnosaurs in the carcharodontosaurid family, such as ''Gi ...

.

History of discovery and naming

paleontologist

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

, in the small ''Le Cavere'' quarry at the edge of the village of Pietraroja

Pietraroja is a mountain '' comune'' (municipality) in the province of Benevento in Campania, southern Italy. It is approximately 50 km by car from Benevento, in direction north-west, 83 km from Naples in direction north-east and app ...

, approximately seventy kilometers northeast of Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adm ...

. The specimen was preserved in the marine Pietraroja Formation, well known for unusually well-conserved fossils. Todesco thought the remains belonged to an extinct bird. He prepared the strange discovery in the basement of his house in San Giovanni Ilarione

San Giovanni Ilarione is a '' comune'' (municipality) in the Province of Verona in the Italian region Veneto, located about west of Venice and about northeast of Verona.

San Giovanni Ilarione borders the following municipalities: Cazzano di Tr ...

near Verona

Verona ( , ; vec, Verona or ) is a city on the Adige River in Veneto, Italy, with 258,031 inhabitants. It is one of the seven provincial capitals of the region. It is the largest city municipality in the region and the second largest in nor ...

, removing, without the use of any optical instrument, part of the chalk matrix from the top of the bones and covering them with vinyl glue. He strengthened the stone plate by adding pieces to its rim and on one of these he added a fake tail made from polyester resin as that of the fossil was largely lacking because he had failed to recover it completely. In early 1993 Todesco, who had nicknamed the animal ''cagnolino'', "little doggie", after its toothy jaws, brought the specimen to the attention of paleontologist Giorgio Teruzzi of the ''Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Milano

The Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Milano (Milan Natural History Museum) is a museum in Milan, Italy. It was founded in 1838 when

naturalist Giuseppe de Cristoforis donated his collections to the city. Its first director was Giorgio Jan. ...

'', who identified it as the juvenile of a theropod dinosaur and nicknamed it ''Ambrogio'' after the patron saint

A patron saint, patroness saint, patron hallow or heavenly protector is a saint who in Catholicism, Anglicanism, or Eastern Orthodoxy is regarded as the heavenly advocate of a nation, place, craft, activity, class, clan, family, or perso ...

of Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city ...

, Ambrose

Ambrose of Milan ( la, Aurelius Ambrosius; ), venerated as Saint Ambrose, ; lmo, Sant Ambroeus . was a theologian and statesman who served as Bishop of Milan from 374 to 397. He expressed himself prominently as a public figure, fiercely promot ...

. Not being an expert in the field of dinosaur studies himself, he called in the help of colleague Father Giuseppe Leonardi

Giuseppe Leonardi (born 31 July 1996) is an Italian sprinter, selected to be part of the Italian athletics team for the Tokyo 2020 Olympics, as a possible member of the relay team

A relay race is a racing competition where members of a team ...

. In Italy such finds are by law State property and Todesco was convinced by science reporter Franco Capone to report the discovery to the authorities: on 15 October 1993 Todesco personally delivered the fossil to the Archaeological Directorship at Naples. The specimen was added to the collection of the regional ''Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici di Salerno, Avellino, Benevento e Caserta'' in Salerno

Salerno (, , ; nap, label= Salernitano, Saliernë, ) is an ancient city and ''comune'' in Campania (southwestern Italy) and is the capital of the namesake province, being the second largest city in the region by number of inhabitants, after ...

, to which it officially still belongs; on 19 April 2002 it was given its own display at the '' Museo Archeologico di Benevento''.

In 1993 Teruzzi and Leonardi scientifically reported the find, which generated some publicity as it was the very first dinosaur found in Italy. The popular magazine '' Oggi'' simultaneously nicknamed the animal ''Ciro'', a typical Neapolitan boy's name, an idea by chief-editor Pino Aprile.Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2011) ''Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages.'' In 1994 Leonardi published a larger article about the discovery. In 1995 Marco Signore of the

In 1993 Teruzzi and Leonardi scientifically reported the find, which generated some publicity as it was the very first dinosaur found in Italy. The popular magazine '' Oggi'' simultaneously nicknamed the animal ''Ciro'', a typical Neapolitan boy's name, an idea by chief-editor Pino Aprile.Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2011) ''Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages.'' In 1994 Leonardi published a larger article about the discovery. In 1995 Marco Signore of the University of Naples Federico II

The University of Naples Federico II ( it, Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II) is a public university in Naples, Italy. Founded in 1224, it is the oldest public non-sectarian university in the world, and is now organized into 26 depar ...

submitted a thesis

A thesis ( : theses), or dissertation (abbreviated diss.), is a document submitted in support of candidature for an academic degree or professional qualification presenting the author's research and findings.International Standard ISO 7144 ...

containing a lengthy description of the fossil, in which he named it "Dromaeodaimon irene". Because the thesis was unpublished this remained an invalid ''nomen ex dissertatione''. Meanwhile, in Salerno, Sergio Rampinelli had begun a further preparation of the fossil, during three hundred hours of work removing the fake tail, replacing the vinyl glue with a modern resin preservative and finishing the uncovering of the bones. On this occasion it was discovered that large parts of the soft tissues had been preserved.

In 1998, ''Ciro'' because of this made the front cover of ''Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are ...

'', when the type species

In zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the species that contains the biological type specim ...

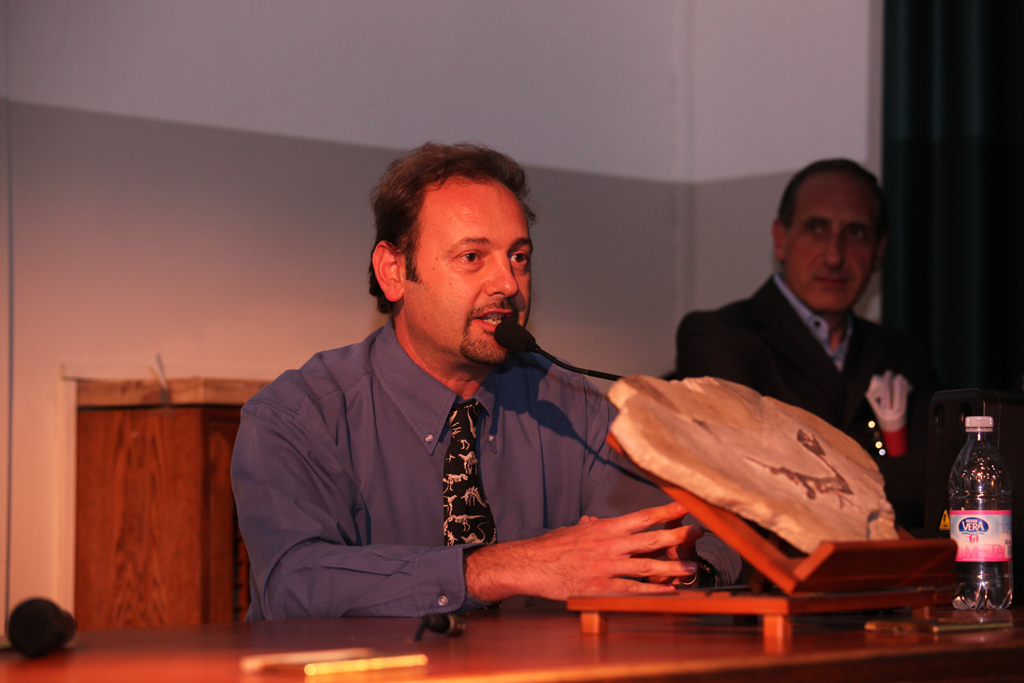

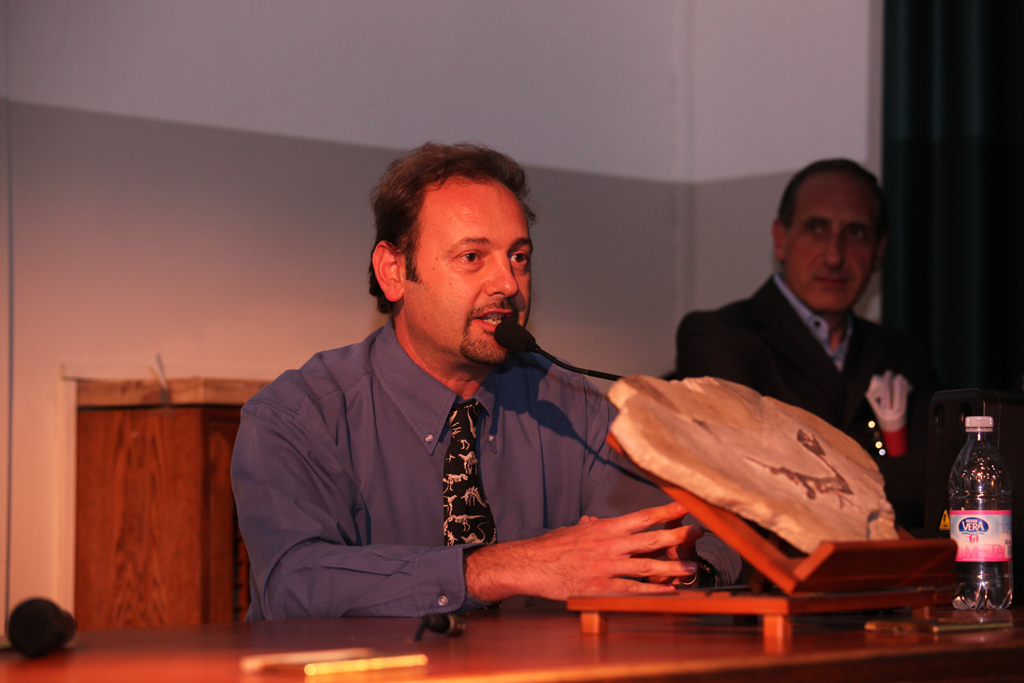

''Scipionyx samniticus'' was named and described by Marco Signore and Cristiano Dal Sasso

Cristiano Dal Sasso (born 12 September 1965) is an Italian paleontologist.

Biography

He was born in Monza, Italy and has been working since 1991 for the Milan Natural History Museum where he is the curator of fossil reptiles and birds. He was ...

. The generic name ''Scipionyx'' comes from the Latin name ''Scipio'' and the Greek ὄνυξ, ''onyx'', the combination meaning "Scipio's claw". "Scipio" refers to both Scipione Breislak, the 18th century geologist who wrote the first description of the formation in which the fossil was found and Scipio Africanus

Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus (, , ; 236/235–183 BC) was a Roman general and statesman, most notable as one of the main architects of Rome's victory against Carthage in the Second Punic War. Often regarded as one of the best military co ...

, the famous Roman consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states throu ...

fighting Hannibal

Hannibal (; xpu, 𐤇𐤍𐤁𐤏𐤋, ''Ḥannibaʿl''; 247 – between 183 and 181 BC) was a Carthaginian general and statesman who commanded the forces of Carthage in their battle against the Roman Republic during the Second Pu ...

. The specific name ''samniticus'' means "From Samnium

Samnium ( it, Sannio) is a Latin exonym for a region of Southern Italy anciently inhabited by the Samnites. Their own endonyms were ''Safinim'' for the country (attested in one inscription and one coin legend) and ''Safineis'' for the Th ...

", the Latin name of the region around Pietraroja. Several other names had been considered but rejected, such as "Italosaurus", "Italoraptor" and "Microraptor". The last name has since been used for a genus of "four-winged" dromaeosaurid discovered in China a few years later.

The holotype

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of seve ...

, SBA-SA 163760, dates from the early Albian

The Albian is both an age of the geologic timescale and a stage in the stratigraphic column. It is the youngest or uppermost subdivision of the Early/Lower Cretaceous Epoch/ Series. Its approximate time range is 113.0 ± 1.0 Ma to 100.5 ± 0 ...

, about 110 million years old, and consists of an almost complete skeleton of a juvenile individual, lacking only the end of the tail, the lower legs and the claw of the right second finger. Extensive soft tissues have been preserved but no parts of the skin or any integument such as scales or feathers.

In view of the exceptional importance of the find, between December 2005 and October 2008 the fossil was intensively studied in Milan resulting in a monograph

A monograph is a specialist work of writing (in contrast to reference works) or exhibition on a single subject or an aspect of a subject, often by a single author or artist, and usually on a scholarly subject.

In library cataloging, ''monogra ...

by dal Sasso and Simone Maganuco published in 2011,Cristiano dal Sasso & Simone Maganuco, 2011, '' ''Scipionyx samniticus'' (Theropoda: Compsognathidae) from the Lower Cretaceous of Italy — Osteology, ontogenetic assessment, phylogeny, soft tissue anatomy, taphonomy and palaeobiology'', Memorie della Società Italiana de Scienze Naturali e del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Milano XXXVII(I): 1-281 containing the most extensive description of a single dinosaur species ever.

In 2021, the Italian paleontologist Andrea Cau proposed that the holotype of ''Scipionyx'' is a hatchling carcharodontosaur.Description

Size

The holotype of ''Scipionyx'' represents a very small individual, the preserved length being just 237 millimetres. In 2011 dal Sasso & Maganuco estimated its total length, including the missing tail section, at 461 millimetres. The specimen was not much smaller than known embryos or hatchlings of ''

The holotype of ''Scipionyx'' represents a very small individual, the preserved length being just 237 millimetres. In 2011 dal Sasso & Maganuco estimated its total length, including the missing tail section, at 461 millimetres. The specimen was not much smaller than known embryos or hatchlings of ''Lourinhasaurus

''Lourinhasaurus'' (meaning "Lourinhã lizard") was an herbivorous sauropod dinosaur genus dating from Late Jurassic strata of Estremadura, Portugal.

Discovery

The first find in 1949 by Harold Weston Robbins, a partial fossil skeleton fou ...

'' and ''Allosaurus

''Allosaurus'' () is a genus of large carnosaurian theropod dinosaur that lived 155 to 145 million years ago during the Late Jurassic epoch ( Kimmeridgian to late Tithonian). The name "''Allosaurus''" means "different lizard" alludin ...

'', theropods of considerable magnitude. However, given its affinities with the Compsognathidae

Compsognathidae is a family of coelurosaurian theropod dinosaurs. Compsognathids were small carnivores, generally conservative in form, hailing from the Jurassic and Cretaceous Periods. The bird-like features of these species, along with other d ...

, it is likely that the adult size of ''Scipionyx'' did not surpass that of the largest known compsognathid, ''Sinocalliopteryx

''Sinocalliopteryx'' (meaning 'Chinese beautiful feather') is a genus of carnivorous compsognathid theropod dinosaurs from the Lower Cretaceous Yixian Formation of China (Jianshangou Beds, dating to 124.6 Ma).

While similar to the related ' ...

'' of 237 centimetres length. As the hatchling would have fitted within an egg about eleven centimetres long and six centimetres wide, this would have implied a rather high egg size compared to the adult body length.

General build

Because the holotype is a hatchling of perhaps only a few days old, it is hard to determine the build of the adult animal but some general conclusions can be reliably made. ''Scipionyx'' was a small bipedal predator. Its horizontal rump was balanced by a long tail. The neck was relatively long and slender. The hindlimbs and especially the forelimbs were rather elongated. Dal Sasso & Maganuco considered it likely that a coat of primitive protofeathers was present, as these are also known from some direct relatives.

Because the holotype is a hatchling of perhaps only a few days old, it is hard to determine the build of the adult animal but some general conclusions can be reliably made. ''Scipionyx'' was a small bipedal predator. Its horizontal rump was balanced by a long tail. The neck was relatively long and slender. The hindlimbs and especially the forelimbs were rather elongated. Dal Sasso & Maganuco considered it likely that a coat of primitive protofeathers was present, as these are also known from some direct relatives.

Diagnostic traits

The 2011 study established eight unique derived traits orautapomorphies

In phylogenetics, an autapomorphy is a distinctive feature, known as a derived trait, that is unique to a given taxon. That is, it is found only in one taxon, but not found in any others or outgroup taxa, not even those most closely related to t ...

in which ''Scipionyx'' differed from its closest relatives. The praemaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammal has ...

has five teeth. Where the parietal and the frontal

Front may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''The Front'' (1943 film), a 1943 Soviet drama film

* ''The Front'', 1976 film

Music

*The Front (band), an American rock band signed to Columbia Records and active in the 1980s and ea ...

bone make contact, the depression in which the supratemporal fenestra, a skull roof opening, was present, shows a sinuous ridge on the postorbital

The ''postorbital'' is one of the bones in vertebrate skulls which forms a portion of the dermal skull roof and, sometimes, a ring about the orbit. Generally, it is located behind the postfrontal and posteriorly to the orbital fenestra. In some ...

. The lower branch of the squamosal The squamosal is a skull bone found in most reptiles, amphibians, and birds. In fishes, it is also called the pterotic bone.

In most tetrapods, the squamosal and quadratojugal bones form the cheek series of the skull. The bone forms an ancestral co ...

has a rectangular end. The wrist consists of just two, superimposed, bones: a radial and a lower element formed by a fusion of the first and second carpal. This last element has the shape of a lens, not a crescent; is flattened; and is fused seamlessly. The first finger is conspicuously elongated, 23% longer than the third finger. The notch in the front edge of the ilium is directed to the front and only weakly developed. The front edge of the ischium

The ischium () form ...

shaft has a long obturator process with a rectangular end.

Skull

The skull of the holotype is large, compared to the size of the body, and short with very large eye-sockets. This is largely due to its young age. Accordingly, the semi-circular

The skull of the holotype is large, compared to the size of the body, and short with very large eye-sockets. This is largely due to its young age. Accordingly, the semi-circular antorbital fenestra

An antorbital fenestra (plural: fenestrae) is an opening in the skull that is in front of the eye sockets. This skull character is largely associated with archosauriforms, first appearing during the Triassic Period. Among extant archosaurs, bird ...

, the normally largest skull opening, is short too and smaller than the eye-socket. In front of it two smaller openings are present: the maxillary and promaxillary. The snout is pointed with a low rounded tip. The premaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammal has ...

, the bone forming the front of the snout, carries five teeth. The maxilla

The maxilla (plural: ''maxillae'' ) in vertebrates is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. T ...

behind it, is deep with a very short front branch. It carries seven teeth. The depression in its surface for the antorbital opening is bounded by a ridge. The lacrimal is robust and lacks a horn; its side is not pierced by a foramen. The prefrontal is exceptionally large, forming a large part of the front upper edge of the eye-socket. The frontal

Front may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''The Front'' (1943 film), a 1943 Soviet drama film

* ''The Front'', 1976 film

Music

*The Front (band), an American rock band signed to Columbia Records and active in the 1980s and ea ...

bones have a transverse ridge at their back. Between the frontals and the parietals the skull roof over a limited distance has not closed yet, resulting in a conspicuous diamond-shaped opening, a fontanelle

A fontanelle (or fontanel) (colloquially, soft spot) is an anatomical feature of the infant human skull comprising soft membranous gaps ( sutures) between the cranial bones that make up the calvaria of a fetus or an infant. Fontanelles allow ...

that was first mistaken for damage inflicted on the fossil during the first preparation. On its inner side the supratemporal fenestra has no depression, being bounded by a high edge of the parietal. The jugal

The jugal is a skull bone found in most reptiles, amphibians and birds. In mammals, the jugal is often called the malar or zygomatic. It is connected to the quadratojugal and maxilla, as well as other bones, which may vary by species.

Anatomy ...

has no front vertical branch towards the lacrimal. The quadrate bone

The quadrate bone is a skull bone in most tetrapods, including amphibians, sauropsids (reptiles, birds), and early synapsids.

In most tetrapods, the quadrate bone connects to the quadratojugal and squamosal bones in the skull, and forms upper pa ...

has on its front edge a large wing-like expansion, touching the pterygoid Pterygoid, from the Greek for 'winglike', may refer to:

* Pterygoid bone, a bone of the palate of many vertebrates

* Pterygoid processes of the sphenoid bone

** Lateral pterygoid plate

** Medial pterygoid plate

* Lateral pterygoid muscle

* Medi ...

. The bones of the braincase are largely inaccessible but a small inner ear opening, the ''recessus tympanicus dorsalis'', is visible. The underside of the braincase lacks an inflated part or ''bulla''.

The lower jaw is straight and elongated. The jaw bone is rather low: the specimen creates the illusion of a strong jaw because the left jaw is visible below the right one. It bears ten teeth. In the 1998 description a part of the splenial

The splenial is a small bone in the lower jaw of reptiles, amphibians and birds, usually located on the lingual side (closest to the tongue) between the angular and surangular

The suprangular or surangular is a jaw bone found in most land ver ...

was mistaken for a supradentarium and the angular was misidentified as the surangular

The suprangular or surangular is a jaw bone found in most land vertebrates, except mammals. Usually in the back of the jaw, on the upper edge, it is connected to all other jaw bones: dentary, angular, splenial and articular. It is often a mu ...

because in the fossil it had been displaced upwards, creating the false impression an external mandibular fenestra, an opening in the outer side of the jaw, would be present.

''Scipionyx'' has five teeth in the premaxilla, seven in the maxilla and ten in the dentary

In anatomy, the mandible, lower jaw or jawbone is the largest, strongest and lowest bone in the human facial skeleton. It forms the lower jaw and holds the lower teeth in place. The mandible sits beneath the maxilla. It is the only movable bone ...

of the lower jaw for a total of twenty-two per side and a grand total for the head of forty-four. The number of five premaxillary teeth is surprising, as a total of four is normal for compsognathids: otherwise, only some Carnosauria

Carnosauria is an extinct large group of predatory dinosaurs that lived during the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. Starting from the 1990s, scientists have discovered some very large carnosaurs in the carcharodontosaurid family, such as '' G ...

have five. Due to the young age of the specimen, the tooth replacement cycle had not started yet, causing a perfect dental symmetry between the left and the right jaws. The teeth lack the typical compsognathid shape with a suddenly recurving apex of the tooth crown. Instead, in general they curve gradually; only the largest teeth show something of a "kink". Exceptionally, the tooth row of the lower jaw extends further to the back than that of the upper jaw. The premaxillary teeth are pointed and lack denticles. The first four have an oval cross-section; the fifth is more flattened near its apex. The second and fifth teeth are the largest. The maxillary teeth are flattened with denticles on their trailing edges. The second and fourth maxillary teeth are the largest; the latter being the largest tooth of all. Of the ten teeth of the lower jaw, the first two are rather straight with an oval cross-section and lack denticles. The third tooth has denticles at its base and a flatter top; the other seven are more recurved and flattened along their entire height; gradually the denticles reach the apex.

Postcrania

Thevertebral column

The vertebral column, also known as the backbone or spine, is part of the axial skeleton. The vertebral column is the defining characteristic of a vertebrate in which the notochord (a flexible rod of uniform composition) found in all chordate ...

of ''Scipionyx'' probably includes ten cervical vertebrae and thirteen dorsal vertebrae; due to the fact the specimen is just a hatchling, the differentiation between the two categories has not fully developed, making any distinction rather arbitrary. With certainty five sacral vertebrae are present. The fossil has preserved just nine tail vertebrae; likely fifty or more had been originally present. The neck vertebrae are opisthocoelous. The axis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rotation around a fixed axis

* Axis (mathematics), a designator for a Cartesian-coordinat ...

is pneumatised as a pneumatopore, an opening through which a diverticulum of the air sack of the neck base could reach its hollow interior, is visible on its side. The third, fourth and fifth vertebrae also show pneumatopores but the consecutive series lacks them, which is surprising as it had been assumed the pneumatisation process would have started at the back, working itself forward. Contrary to what was stated by the 1998 study, the cervical ribs are very elongated, with a length of up to three vertebral centra.

The vertebrae of the back are not pneumatised. They are amphiplatyan with an oval cross-section and bear low spines with a hexagonal profile. Just below the top of the spine on the front and back edge a small beak-shaped process is present. In 1998 interpreted as a reduced hyposphene- hypantrum complex, a system of secondary vertebral joints shown by many theropods, it was by the 2011 study seen as a pair of attachment points for tendons, as identified in 2006 in ''Compsognathus''. Exceptionally, with the thirteenth vertebra the two rib joint processes, the parapophysis and the diapophysis, are positioned at the same level. The five sacral vertebrae have not yet fused into a real sacrum

The sacrum (plural: ''sacra'' or ''sacrums''), in human anatomy, is a large, triangular bone at the base of the spine that forms by the fusing of the sacral vertebrae (S1S5) between ages 18 and 30.

The sacrum situates at the upper, back part o ...

. The tail vertebrae are platycoelous with low spines and backward slanting chevrons.

There are at least twelve pairs of dorsal ribs; some displaced elements might represent a thirteenth pair. The third and fourth rib have expanded lower ends that in life probably were attached to cartilaginous sternal ribs, themselves connected to sterna

''Sterna'' is a genus of terns in the bird family Laridae. The genus used to encompass most "white" terns indiscriminately, but mtDNA sequence comparisons have recently determined that this arrangement is paraphyletic. It is now restricted to t ...

that in the holotype specimen have not (yet) ossified. The lower rump is covered by a basket of eighteen pairs of gastralia

Gastralia (singular gastralium) are dermal bones found in the ventral body wall of modern crocodilians and tuatara, and many prehistoric tetrapods. They are found between the sternum and pelvis, and do not articulate with the vertebrae. In thes ...

or belly ribs. Mysterious shaft parts present near the forelimbs are by Dal Sasso & Maganuco interpreted as the remains of a nineteenth frontmost element consisting of two completely fused shafts homologous to the normal medial elements of a pair of gastralia; such a chevron-like bone has also been reported with ''Juravenator

''Juravenator'' is a genus of small (75 cm long) coelurosaurian theropod dinosaur (although a 2020 study proposed it to be a hatchling megalosauroid), which lived in the area which would someday become the top of the Franconian Jura of Ger ...

''. The gastralia form a herringbone pattern, the left and right medial elements overlapping each other at their forked ends in order that the basket can expand and contract to accommodate the breathing movements of the abdomen.

The scapula

The scapula (plural scapulae or scapulas), also known as the shoulder blade, is the bone that connects the humerus (upper arm bone) with the clavicle (collar bone). Like their connected bones, the scapulae are paired, with each scapula on eith ...

is relatively straight and about six to seven times longer than wide; its upper end is missing. Its lower end is connected to a semicircular coracoid

A coracoid (from Greek κόραξ, ''koraks'', raven) is a paired bone which is part of the shoulder assembly in all vertebrates except therian mammals (marsupials and placentals). In therian mammals (including humans), a coracoid process is prese ...

. The furcula

The (Latin for "little fork") or wishbone is a forked bone found in most birds and some species of non-avian dinosaurs, and is formed by the fusion of the two pink

clavicles. In birds, its primary function is in the strengthening of the thoracic ...

is broad and more or less U-shaped with its two branches angled at 125°. The forelimb is rather long; its length is equal to 48% of the body length in front of the pelvis. Especially the hand is elongated as is typical for compsognathids; for a member of that group ''Scipionyx'' has a relatively short hand, however. The humerus

The humerus (; ) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extremity consists of a r ...

is straight with a moderately developed deltopectoral crest. The ulna

The ulna (''pl''. ulnae or ulnas) is a long bone found in the forearm that stretches from the elbow to the smallest finger, and when in anatomical position, is found on the medial side of the forearm. That is, the ulna is on the same side of t ...

is slender and cylinder-shaped with a length of 70% of that of the humerus. The wrist consists of two elements only: a radial bone capping the lower end of the radius

In classical geometry, a radius (plural, : radii) of a circle or sphere is any of the line segments from its Centre (geometry), center to its perimeter, and in more modern usage, it is also their length. The name comes from the latin ''radius'', ...

and a disc-shaped bone below it; this is either the enlarged first lower carpal or a perfect seamless fusion of the first and second lower carpal. The metacarpus

In human anatomy, the metacarpal bones or metacarpus form the intermediate part of the skeletal hand located between the phalanges of the fingers and the carpal bones of the wrist, which forms the connection to the forearm. The metacarpal bones ...

is compact and moderately elongated. Its three elements mirror the shape of the fingers they bear: the first is the shortest en thickest; the second the longest; and the third is intermediate in length and thickness. The third finger is exceptionally long for a comspognathid, with 123% of thumb length. As the lower joint of the first metacarpal

In human anatomy, the metacarpal bones or metacarpus form the intermediate part of the skeletal hand located between the phalanges of the fingers and the carpal bones of the wrist, which forms the connection to the forearm. The metacarpal bones ar ...

is bevelled, the thumb diverges medially. Its claw is no larger than that of the second finger. The hand claws are moderately curved.

In the pelvis the ilium is short and flat with a slightly convex upper profile. The back end is rectangular, the front edge has an appending hook-shaped point and near its top a circular notch, a trait that is usually considered a synapomorphy

In phylogenetics, an apomorphy (or derived trait) is a novel character or character state that has evolved from its ancestral form (or plesiomorphy). A synapomorphy is an apomorphy shared by two or more taxa and is therefore hypothesized to hav ...

of the Tyrannosauroidea

Tyrannosauroidea (meaning 'tyrant lizard forms') is a superfamily (or clade) of coelurosaurian theropod dinosaurs that includes the family Tyrannosauridae as well as more basal relatives. Tyrannosauroids lived on the Laurasian supercontin ...

. The pubic bone

In vertebrates, the pubic region ( la, pubis) is the most forward-facing ( ventral and anterior) of the three main regions making up the coxal bone. The left and right pubic regions are each made up of three sections, a superior ramus, inferior ...

points almost vertically downwards and is thus "mesopubic" or "orthopubic". It is relatively short with about two thirds of the length of the femur. It has a short "foot" shaped like a golf club. The ischium

The ischium () form ...

has three quarters the length of the pubis, set at an angle of 54° to it. It ends in a small expansion. On the front of its shaft a large hatchet-shaped obturator process is present, the attachment for the '' Musculus puboischiofemoralis externus'', that lacks a small circular notch between its lower edge and the shaft, though this lack is normally associated with the possession of a lower triangular ''processus obturatorius''.

Of the hindlimb, the lower leg is missing. The femur

The femur (; ), or thigh bone, is the proximal bone of the hindlimb in tetrapod vertebrates. The head of the femur articulates with the acetabulum in the pelvic bone forming the hip joint, while the distal part of the femur articulates ...

or thigh bone is straight and robust. The lesser trochanter is markedly lower than the greater trochanter and separated from it by a narrow cleft. It has the shape of a wing-like expansion to the front. An accessory or posterior trochanter is lacking; likewise a fourth trochanter on the back shaft is absent. The tibia

The tibia (; ), also known as the shinbone or shankbone, is the larger, stronger, and anterior (frontal) of the two bones in the leg below the knee in vertebrates (the other being the fibula, behind and to the outside of the tibia); it conn ...

has only a weak cnemial crest, separated from its outer condyle by a deep narrow groove, the ''incisura tibialis''. The fibula

The fibula or calf bone is a leg bone on the lateral side of the tibia, to which it is connected above and below. It is the smaller of the two bones and, in proportion to its length, the most slender of all the long bones. Its upper extremity ...

is broad on top but has a slender shaft.

Soft tissues

The holotype preserves an exceptionally large set of soft tissues for a fossil dinosaur. Although some muscle tissue ('' Santanaraptor'', ''Pelecanimimus

''Pelecanimimus'' (meaning " pelican mimic") is an extinct genus of basal ("primitive") ornithomimosaurian dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous of Spain. It is notable for possessing more teeth than any other member of the Ornithomimosauria ...

''), cartilage

Cartilage is a resilient and smooth type of connective tissue. In tetrapods, it covers and protects the ends of long bones at the joints as articular cartilage, and is a structural component of many body parts including the rib cage, the neck ...

(''Juravenator

''Juravenator'' is a genus of small (75 cm long) coelurosaurian theropod dinosaur (although a 2020 study proposed it to be a hatchling megalosauroid), which lived in the area which would someday become the top of the Franconian Jura of Ger ...

'', ''Aucasaurus

''Aucasaurus'' is a genus of medium-sized abelisaurid theropod dinosaur from Argentina that lived during the Late Cretaceous (Santonian to Campanian stage) of the Anacleto Formation. It was smaller than the related ''Carnotaurus'', although m ...

'') or an intestine ('' Mirischia'', ''Daurlong

''Daurlong'' (meaning " Daur dragon") is an extinct genus of dromaeosaurid dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous (Aptian) Longjiang Formation of China. The genus contains a single species, ''D. wangi'', known from a nearly complete skeleton. ''Dau ...

'') have been reported from other dinosaurs, ''Scipionyx'' is unique in preserving in some form examples from most major internal organ groups: blood, blood vessels, cartilage, connective tissues, bone tissue, muscle tissue, horn sheaths, the respiratory system and the digestive system. Nervous tissue and the external skin, including possible scales or feathers, are absent.

The soft tissues are not present in the form of imprints but as three-dimensional petrifications, having been replaced by calcium phosphate

The term calcium phosphate refers to a family of materials and minerals containing calcium ions (Ca2+) together with inorganic phosphate anions. Some so-called calcium phosphates contain oxide and hydroxide as well. Calcium phosphates are whi ...

in amazing detail, even to the subcellular level; or as transformed remains of the original biomolecular components.

Bone tissue

The original bone tissue is no longer present but the calcium phosphate mineralisation has preserved the structure of original bone cells, showing individualosteocyte

An osteocyte, an oblate shaped type of bone cell with dendritic processes, is the most commonly found cell in mature bone. It can live as long as the organism itself. The adult human body has about 42 billion of them. Osteocytes do not divide an ...

s including their inner hollow spaces and the ''canaliculi''. Also the internal blood vessels of the bone have been preserved, in some cases still empty inside. On some bones, including some of the skull and lower jaws, the periosteum

The periosteum is a membrane that covers the outer surface of all bones, except at the articular surfaces (i.e. the parts within a joint space) of long bones. Endosteum lines the inner surface of the medullary cavity of all long bones.

Structu ...

is still visible.

Ligaments and cartilage

From the ninth cervical vertebra to the back, the vertebral joints show the remains ofarticular capsule

In anatomy, a joint capsule or articular capsule is an envelope surrounding a synovial joint.ligaments

A ligament is the fibrous connective tissue that connects bones to other bones. It is also known as ''articular ligament'', ''articular larua'', ''fibrous ligament'', or ''true ligament''. Other ligaments in the body include the:

* Peritoneal ...

are visible. Six vertebrae are visibly capped by cartilaginous synchondroses, a typical juvenile feature. Cartilaginous caps are also present on all limb joints, even the smallest, and are especially thick in the shoulder, elbow and wrist joints. Also the pubic foot is capped and the ilium and pubic bone are separated by cartilage.

Respiratory system

Of therespiratory system

The respiratory system (also respiratory apparatus, ventilatory system) is a biological system consisting of specific organs and structures used for gas exchange in animals and plants. The anatomy and physiology that make this happen varies g ...

little has been preserved. No traces of the lungs have survived, nor of any air sacks. The sole element still present consists of a seven millimetre long piece of the trachea

The trachea, also known as the windpipe, is a cartilaginous tube that connects the larynx to the bronchi of the lungs, allowing the passage of air, and so is present in almost all air- breathing animals with lungs. The trachea extends from t ...

of which about ten tracheal rings are visible, the most anterior of which are open at the top, giving them a C-shape. They have an average length of 0.33 millimetres and are separated by 0.17 millimetre thick interspaces. The trachea is quite thin, with a preserved width of one millimetre about half as wide as would be expected for an animal the size of the holotype, and positioned rather low in the neck base, embedded in connective tissue.

Liver, heart, spleen and thymus

In the front part of thethorax

The thorax or chest is a part of the anatomy of humans, mammals, and other tetrapod animals located between the neck and the abdomen. In insects, crustaceans, and the extinct trilobites, the thorax is one of the three main divisions of the c ...

a conspicuous red halo is visible, forming a roughly circular stain with a diameter of seventeen millimetres. In 1998 it was suggested this might represent the remains of the decayed liver

The liver is a major organ only found in vertebrates which performs many essential biological functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the synthesis of proteins and biochemicals necessary for digestion and growth. In humans, it i ...

, a blood-rich organ. That the red pigment was indeed derived from blood, was confirmed in 2011: a scanning electron microscope analysis indicated that the substance consisted of limonite

Limonite () is an iron ore consisting of a mixture of hydrated iron(III) oxide-hydroxides in varying composition. The generic formula is frequently written as FeO(OH)·H2O, although this is not entirely accurate as the ratio of oxide to hydroxide ...

, hydrated iron oxide

Iron oxides are chemical compounds composed of iron and oxygen. Several iron oxides are recognized. All are black magnetic solids. Often they are non-stoichiometric. Oxyhydroxides are a related class of compounds, perhaps the best known of wh ...

, a likely transformation product of the original haemoglobin

Hemoglobin (haemoglobin BrE) (from the Greek word αἷμα, ''haîma'' 'blood' + Latin ''globus'' 'ball, sphere' + ''-in'') (), abbreviated Hb or Hgb, is the iron-containing oxygen-transport metalloprotein present in red blood cells (erythrocyte ...

. Also biliverdine was present, a bile

Bile (from Latin ''bilis''), or gall, is a dark-green-to-yellowish-brown fluid produced by the liver of most vertebrates that aids the digestion of lipids in the small intestine. In humans, bile is produced continuously by the liver (liver bi ...

component expected in the liver. The blood might also partly have originated from the heart

The heart is a muscular Organ (biology), organ in most animals. This organ pumps blood through the blood vessels of the circulatory system. The pumped blood carries oxygen and nutrients to the body, while carrying metabolic waste such as ca ...

and the spleen

The spleen is an organ found in almost all vertebrates. Similar in structure to a large lymph node, it acts primarily as a blood filter. The word spleen comes .

, two similarly blood-rich organs, with reptiles positioned between the two lobes of the liver.

Another organ in the thorax, traces of which might be present, is the thymus

The thymus is a specialized primary lymphoid organ of the immune system. Within the thymus, thymus cell lymphocytes or '' T cells'' mature. T cells are critical to the adaptive immune system, where the body adapts to specific foreign invaders ...

, which might have contributed to a greyish mass of organic origin visible in the neck base; this also contains connective and muscle tissue.

Digestive system

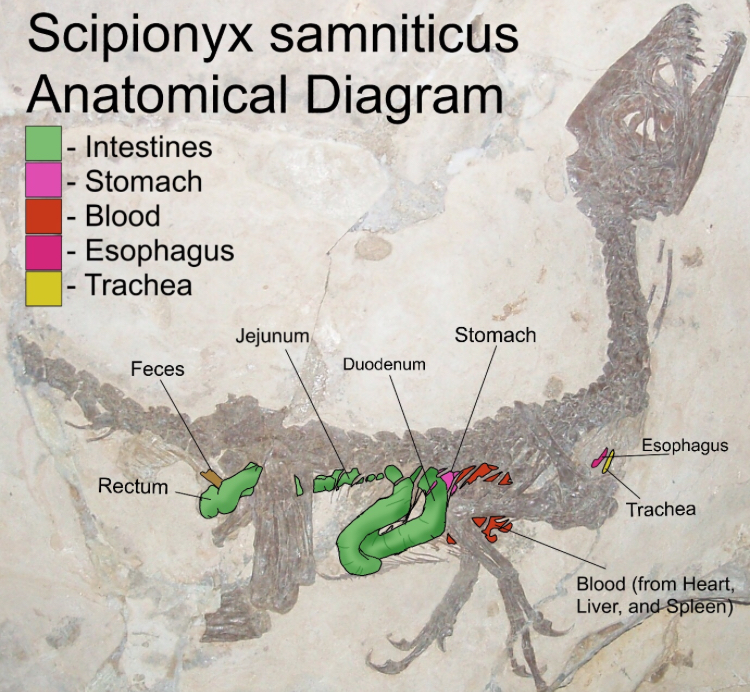

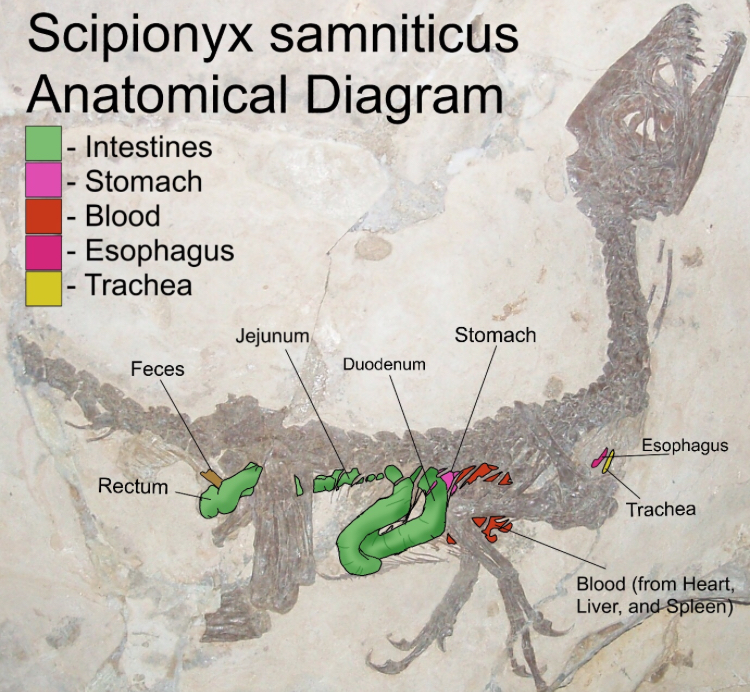

The

The digestive tract

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans and ...

can mostly be traced, either because the intestines are still present or by the presence of food items. The position of the oesophagus

The esophagus ( American English) or oesophagus (British English; both ), non-technically known also as the food pipe or gullet, is an organ in vertebrates through which food passes, aided by peristaltic contractions, from the pharynx to ...

is indicated by a five millimetre long series of small food particles. Below the ninth dorsal vertebra the location of the stomach is shown by a cluster of bones of prey animals, the organ itself likely having been dissolved by its own stomach acid

Gastric acid, gastric juice, or stomach acid is a digestive fluid formed within the stomach lining. With a pH between 1 and 3, gastric acid plays a key role in digestion of proteins by activating digestive enzymes, which together break down the ...

shortly after death. The rather backward position of the cluster suggests the stomach was dual in structure, with a forward enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products ...

-secreting proventriculus preceding a muscular gizzard

The gizzard, also referred to as the ventriculus, gastric mill, and gigerium, is an organ found in the digestive tract of some animals, including archosaurs (pterosaurs, crocodiles, alligators, dinosaurs, birds), earthworms, some gastropods, so ...

. Gastroliths

A gastrolith, also called a stomach stone or gizzard stone, is a rock held inside a gastrointestinal tract. Gastroliths in some species are retained in the muscular gizzard and used to grind food in animals lacking suitable grinding teeth. In othe ...

have not been reported.

Just behind the presumed position of the stomach a very conspicuous large and thick intestine is visible, that has been identified as the duodenum

The duodenum is the first section of the small intestine in most higher vertebrates, including mammals, reptiles, and birds. In fish, the divisions of the small intestine are not as clear, and the terms anterior intestine or proximal intestine m ...

. It is preserved partly in the form of a natural endocast

An endocast is the internal cast of a hollow object, often referring to the cranial vault in the study of brain development in humans and other organisms. Endocasts can be artificially made for examining the properties of a hollow, inaccessible sp ...

, partly as a petrification still showing the cellular structure, including the mucosa

A mucous membrane or mucosa is a membrane that lines various cavities in the body of an organism and covers the surface of internal organs. It consists of one or more layers of epithelial cells overlying a layer of loose connective tissue. It i ...

and connective tissue. Some mesenteric

The mesentery is an organ that attaches the intestines to the posterior abdominal wall in humans and is formed by the double fold of peritoneum. It helps in storing fat and allowing blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves to supply the intestine ...

blood vessels cover the intestine in the form of up to a centimetre long and 0.02 to 0.1 millimetre wide hollow tubes. The duodenum forms a large loop, the descending part of which first is directed downwards towards the gastralia and then runs to the back. There in a sharp bend, the folds of which are clearly visible, it turns to the front, proceeding as an ascending tract, its visible part ending near the stomach. At this point the tract is directed to the left of the body, perpendicular to the fossil slab, and its course can thus no longer be followed. Nearby and slightly above, a subsequent intestine part surfaces that has been interpreted as the jejunum

The jejunum is the second part of the small intestine in humans and most higher vertebrates, including mammals, reptiles, and birds. Its lining is specialised for the absorption by enterocytes of small nutrient molecules which have been previou ...

. This thinner intestine turns to the back, running parallel to the ascending tract of the duodenum and ultimately disappearing under it, at the level of the twelfth dorsal vertebra. Apparently a loop to the front is made because it resurfaces below the tenth dorsal vertebra, first running upwards and then turning to the back below the hind vertebral column — or at places even over it: probably after death its position partly shifted upwards. The jejunum seems to blend with an exceptionally short ileum

The ileum () is the final section of the small intestine in most higher vertebrates, including mammals, reptiles, and birds. In fish, the divisions of the small intestine are not as clear and the terms posterior intestine or distal intestine m ...

. A contraction below the thirteenth dorsal vertebra might indicate the transition to the rectum

The rectum is the final straight portion of the large intestine in humans and some other mammals, and the gut in others. The adult human rectum is about long, and begins at the rectosigmoid junction (the end of the sigmoid colon) at the l ...

. A caecum

The cecum or caecum is a pouch within the peritoneum that is considered to be the beginning of the large intestine. It is typically located on the right side of the body (the same side of the body as the appendix, to which it is joined). The wo ...

seems absent. The rectum runs to the back between the upper shafts of the pubes and ischia. Then it bends downwards parallel to the ischium shaft, at the end of it turning upwards again. In this final part faeces

Feces ( or faeces), known colloquially and in slang as poo and poop, are the solid or semi-solid remains of food that was not digested in the small intestine, and has been broken down by bacteria in the large intestine. Feces contain a relati ...

are still present. The cloaca

In animal anatomy, a cloaca ( ), plural cloacae ( or ), is the posterior orifice that serves as the only opening for the digestive, reproductive, and urinary tracts (if present) of many vertebrate animals. All amphibians, reptiles and birds, ...

is lacking. Dal Sasso & Maganuco suggested the cloaca exit was rather low, at the level of the ischial feet and that a rectocoprodaeal valve separated faeces and urine.

Between the front edge of the pubic shafts and the back of the intestines a large empty space is present. Also, the rectum seems to run in a very high position as if it were forced upwards by something. According to Dal Sasso & Maganuco, in life this space would have been filled by the yolk sac

The yolk sac is a membranous wikt:sac, sac attached to an embryo, formed by cells of the hypoblast layer of the bilaminar embryonic disc. This is alternatively called the umbilical vesicle by the Terminologia Embryologica (TE), though ''yolk sac' ...

of the hatchling; on hatching the juveniles of reptiles typically have not absorbed all the yolk and use the residual nutrients to supplement the food intake during their first weeks.

Muscle tissue

At several places on the fossilmuscle tissue

Muscle tissue (or muscular tissue) is soft tissue that makes up the different types of muscles in most animals, and give the ability of muscles to contract. Muscle tissue is formed during embryonic development, in a process known as myogenesis. ...

is present. The degree of preservation is often exceptional, with not only the individual fibres still discernible but also the individual cells and even the subcellular sarcomere

A sarcomere (Greek σάρξ ''sarx'' "flesh", μέρος ''meros'' "part") is the smallest functional unit of striated muscle tissue. It is the repeating unit between two Z-lines. Skeletal muscles are composed of tubular muscle cells (called mus ...

s. Among dinosaur fossils such sarcomeres are only known from ''Santanaraptor'', whose muscle fibres are four times as thick. The original organic material has been replaced by small hollow globes, the walls of which consist of euhedric crystals of apatite

Apatite is a group of phosphate minerals, usually hydroxyapatite, fluorapatite and chlorapatite, with high concentrations of OH−, F− and Cl− ions, respectively, in the crystal. The formula of the admixture of the three most common ...

.

In the grey organic mass at the neck base, muscle fibres are present that have been identified as belonging to the '' Musculus sternohyoideus'' and the '' Musculus sternotrachealis''. Between the sixth and seventh dorsal vertebra a patch of muscle fibres is visible belonging to either the '' Musculus transversospinalis'' or the '' Musculus longissimus dorsi''. In front of the right ischium muscle fibres are present running from the ischial foot in the direction of the femur. Their identity is uncertain: they could belong to the '' Musculus puboischiofemoralis pars medialis'' (the ''Musculus adductor femoris I'' of crocodiles) but in that case this muscle with (some) non-avian theropods would not be anchored on the obturator process. The fibres could also represent an unknown muscle. In any case they refute a conjecture by Gregory S. Paul

Gregory Scott Paul (born December 24, 1954) is an American freelance researcher, author and illustrator who works in paleontology, and more recently has examined sociology and theology. He is best known for his work and research on theropod dino ...

that there would be no muscle connection between the ischium and the femur at all. Above the rectum tract a large area of horizontal unsegmented muscle fibres is present, probably representing the unsegmented '' Musculus caudofemoralis longus'' of the tail base, the main retractor muscle operating on the thighbone. These fibres are polygonal in cross-section and show the intercellular spaces also. Below some tail base vertebrae the connective ligaments between the chevrons are present, forming the ''ligmamentum interhaemale'', but also some small muscle fibres and some mysterious hollow tubes arranged in a herringbone pattern; the latter perhaps represent the myosepta of the myotome

A myotome is the group of muscles that a single spinal nerve innervates. Similarly a dermatome is an area of skin that a single nerve innervates with sensory fibers. Myotomes are separated by myosepta (singular: myoseptum). In vertebrate embryon ...

s, the segments of the '' Musculus iliocaudalis'' or the '' Musculus ischiocaudalis''.

Horn sheaths

On all claws preserved in the fossil — those of the feet have all been lost — horn sheaths are visible. These have a darker colouration on top than on the bottom which suggests that the original horn material is still present — but this has not yet been directly tested by a chemical analysis for fear of damaging these delicate structures that were seen as forming an essential part of the integrity of the precious specimen. The horn sheaths of the hand claws extend the bony cores by about 40%, scythe-like continuing the bone curve and ending in sharp points. On some claws the sheaths have partly detached; on others they have been flattened or split.Integument

The fossil preserves no traces of any skin, scales or feathers. In 1999

The fossil preserves no traces of any skin, scales or feathers. In 1999 Philip J. Currie

Philip John Currie (born March 13, 1949) is a Canadian palaeontologist and museum curator who helped found the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology in Drumheller, Alberta and is now a professor at the University of Alberta in Edmonton. In the ...

hypothesised this might be otherwise, suggesting the tubes found on the tail base would represent the filaments of protofeathers. In 2011, however, Dal Sasso & Maganuco rejected this interpretation because the tubes taper at both ends, while integument filaments are expected to have only a tapered top end. Nevertheless, they considered it likely that ''Scipionyx'' in life had protofeathers as these are known to be present with the compsognathids ''Sinosauropteryx

''Sinosauropteryx'' (meaning "Chinese reptilian wing", ) is a compsognathid dinosaur. Described in 1996, it was the first dinosaur taxon outside of Avialae (birds and their immediate relatives) to be found with evidence of feathers. It was cover ...

'' and ''Sinocalliopteryx

''Sinocalliopteryx'' (meaning 'Chinese beautiful feather') is a genus of carnivorous compsognathid theropod dinosaurs from the Lower Cretaceous Yixian Formation of China (Jianshangou Beds, dating to 124.6 Ma).

While similar to the related ' ...

''.

Phylogeny

''Scipionyx'' was by the describers assigned to theCoelurosauria

Coelurosauria (; from Greek, meaning "hollow tailed lizards") is the clade containing all theropod dinosaurs more closely related to birds than to carnosaurs.

Coelurosauria is a subgroup of theropod dinosaurs that includes compsognathids, t ...

, a group of theropod

Theropoda (; ), whose members are known as theropods, is a dinosaur clade that is characterized by hollow bones and three toes and claws on each limb. Theropods are generally classed as a group of saurischian dinosaurs. They were ancestrally c ...

s. Because the only remains recovered belong to that of a juvenile, it has proven difficult to assign this dinosaur to a more specific group. One problem is that in the build of a juvenile animal the original traits of ancestor groups are more likely to be expressed, suggesting a too basal position in the evolutionary tree. Part of the 2011 monograph was a cladistic

Cladistics (; ) is an approach to biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups ("clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesized relationships is typically shared derived char ...

analysis which indicated that ''Scipionyx'' was a basal member of the Compsognathidae

Compsognathidae is a family of coelurosaurian theropod dinosaurs. Compsognathids were small carnivores, generally conservative in form, hailing from the Jurassic and Cretaceous Periods. The bird-like features of these species, along with other d ...

and the sister species of ''Orkoraptor

''Orkoraptor'' is a genus of medium-sized megaraptoran theropod dinosaur from the late Cretaceous Period of Argentina. It is known from incomplete fossil remains including parts of the skull, teeth, tail vertebrae, and a partial tibia. The speci ...

''. Dal Sasso & Maganuco emphasised that, due to its limited remains, the position of ''Orkoraptor'' is tentative.

This cladogram shows the position of ''Scipionyx'' in the coelurosaurian tree, according to the 2011 study:

In 2021, a study proposed by Andrea Cau re-evaluated the classification of this specimen and the classification of compsognathids

Compsognathidae is a family of coelurosaurian theropod dinosaurs. Compsognathids were small carnivores, generally conservative in form, hailing from the Jurassic and Cretaceous Periods. The bird-like features of these species, along with other d ...

in general. According to Cau's study, compsognathids would be a "false clade" (a polyphyletic

A polyphyletic group is an assemblage of organisms or other evolving elements that is of mixed evolutionary origin. The term is often applied to groups that share similar features known as homoplasies, which are explained as a result of conver ...

assemblage) and most of the ascribed genera would actually represent juvenile forms or chicks of other tetanuran

Tetanurae (/ˌtɛtəˈnjuːriː/ or "stiff tails") is a clade that includes most theropod dinosaurs, including megalosauroids, allosauroids, tyrannosauroids, ornithomimosaurs, compsognathids and maniraptorans (including birds). Tetanurans ar ...

theropod clades, stating that the same characteristics used to differentiate the group from other families of theropods, are actually the typical characteristics of the chicks of the large basal tetanurae. In his study, Cau proposes a new procedure to classify these animals, applying it to ''Juravenator

''Juravenator'' is a genus of small (75 cm long) coelurosaurian theropod dinosaur (although a 2020 study proposed it to be a hatchling megalosauroid), which lived in the area which would someday become the top of the Franconian Jura of Ger ...

'', ''Scipionyx'' and ''Sciurumimus

''Sciurumimus'' ("Squirrel-mimic," named for its tail's resemblance to that of the tree squirrel, ''Sciurus'') is an extinct genus of Tetanurae, tetanuran Theropoda, theropod from the Late Jurassic of Germany. It is known from a single juvenile s ...

'', obtaining a possible phylogenetic position that was not affected by the immaturity of the specimens. According to this new procedure, ''Juravenator'' and ''Sciurumimus'' turn out to be megalosauroids, while ''Scipionyx'' turns out to be a carcharodontosaurid

Carcharodontosauridae (carcharodontosaurids; from the Greek καρχαροδοντόσαυρος, ''carcharodontósauros'': "shark-toothed lizards") is a group of carnivorous theropod dinosaurs. In 1931, Ernst Stromer named Carcharodontosauridae ...

. This interpretation would also be supported by the similarity of the jaw

The jaw is any opposable articulated structure at the entrance of the mouth, typically used for grasping and manipulating food. The term ''jaws'' is also broadly applied to the whole of the structures constituting the vault of the mouth and serv ...

of ''Scipionyx'' with that of an ''Allosaurus

''Allosaurus'' () is a genus of large carnosaurian theropod dinosaur that lived 155 to 145 million years ago during the Late Jurassic epoch ( Kimmeridgian to late Tithonian). The name "''Allosaurus''" means "different lizard" alludin ...

'' chick. Furthermore, this location would explain the size discrepancy between the ''Scipionyx'' type specimen and the estimated adult size for the presumed adult compsognathids, more in line with the size of the large carcharodontosaurids.

Paleobiology

Habitat

The location where ''Scipionyx'' was found, in the Albian was part of the

The location where ''Scipionyx'' was found, in the Albian was part of the Apulian Plate

The Adriatic or Apulian Plate is a small tectonic plate carrying primarily continental crust that broke away from the African Plate along a large transform fault in the Cretaceous period. The name Adriatic Plate is usually used when referring ...

, at the time largely covered by the shallow Paratethys

The Paratethys sea, Paratethys ocean, Paratethys realm or just Paratethys was a large shallow inland sea that stretched from the region north of the Alps over Central Europe to the Aral Sea in Central Asia.

Paratethys was peculiar due to its p ...

. Some dry land was present however, but it is uncertain how extensive or connected the several terrane

In geology, a terrane (; in full, a tectonostratigraphic terrane) is a crust fragment formed on a tectonic plate (or broken off from it) and accreted or " sutured" to crust lying on another plate. The crustal block or fragment preserves its ow ...

s were. The marine sediments of the Pietraroja ''Plattenkalk'' were probably deposited closely to a piece of the Apennine Platform, which piece possibly formed a small island between the present middle of Italy and Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

. From this it has been concluded that the habitat of ''Scipionyx'' in general consisted of small islands and it represented one of the larger animals of its ecosystem

An ecosystem (or ecological system) consists of all the organisms and the physical environment with which they interact. These biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and energy flows. Energy enters the syst ...

.

However, there are also indications that the terranes regularly interconnected to form far more extensive islands, land bridge

In biogeography, a land bridge is an isthmus or wider land connection between otherwise separate areas, over which animals and plants are able to cross and colonize new lands. A land bridge can be created by marine regression, in which sea leve ...

s allowing a dispersal of much larger animals, such as sauropods

Sauropoda (), whose members are known as sauropods (; from '' sauro-'' + '' -pod'', 'lizard-footed'), is a clade of saurischian ('lizard-hipped') dinosaurs. Sauropods had very long necks, long tails, small heads (relative to the rest of their b ...

and large theropods. If so, they were not present for long when the land surface fragmented again, because there are no signs of insular dwarfism

Insular dwarfism, a form of phyletic dwarfism, is the process and condition of large animals evolving or having a reduced body size when their population's range is limited to a small environment, primarily islands. This natural process is disti ...

, a size reduction as an adaptation to decreased resources. Likewise, ''Scipionyx'' itself is no dwarf among its relatives. Due to its small absolute size, ''Scipionyx'' would have been able to maintain itself when the dry land shrank. Nevertheless, Dal Sasso & Maganuco did not consider ''Scipionyx'' to have been a permanent resident of small islands throughout tens of millions of years, but more likely a recent immigrant arriving during a dispersal wave, probably from North-Africa. They admitted this was at odds with their own phylogenetic analysis, showing ''Scipionyx'' to be a basal compsognathid, but they pointed out that the phylogeny found was uncertain due to the juvenile status of the fossil.

Land animals actually found in the Pietraroja deposits are all small. They include the lizards

Lizards are a widespread group of squamate reptiles, with over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most oceanic island chains. The group is paraphyletic since it excludes the snakes and Amphisbaenia altho ...

'' Chometokadmon'' and ''Eichstaettisaurus

''Eichstaettisaurus'' (meaning "Eichstätt lizard") is a genus of lizards from the Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous of Germany, Spain, and Italy. With a flattened head, forward-oriented and partially symmetrical feet, and tall claws, ''Eichstae ...

gouldi'', a relative of the forty million years older German ''Eichstaettisaurus schroederi''; the rhynchocephalian '' Derasmosaurus'' and the amphibian

Amphibians are four-limbed and ectothermic vertebrates of the class Amphibia. All living amphibians belong to the group Lissamphibia. They inhabit a wide variety of habitats, with most species living within terrestrial, fossorial, arbo ...

''Celtedens

''Celtedens'' is an extinct genus of albanerpetontid amphibian from the Early Cretaceous of England, Spain, Sweden and Italy, and the Late Jurassic of Portugal.

Taxonomy

* †''Celtedens ibericus'' McGowan and Evans 1995 La Huérguina Format ...

megacephalus''.

Food

The fossil provides direct information about the diet of ''Scipionyx'' because remains of a complete series of consecutive meals have been preserved, perhaps everything the animal ate during its short life. These confirm what already could be concluded from its phylogenetic affinities and general build: that ''Scipionyx'' was a predator. In the oesophagus tract about eight scales and some bone fragments are present. Dal Sasso & Maganuco considered it likely that these had not been swallowed as loose elements but were the remains of a meal, partly regurgitated from the stomach in the final death throes. In the stomach position itself, a cluster of small bones is visible. These include an ankle with a three millimetre widemetatarsus

The metatarsal bones, or metatarsus, are a group of five long bones in the foot, located between the tarsal bones of the hind- and mid-foot and the phalanges of the toes. Lacking individual names, the metatarsal bones are numbered from the me ...

consisting of five metatarsal

The metatarsal bones, or metatarsus, are a group of five long bones in the foot, located between the tarsal bones of the hind- and mid-foot and the phalanges of the toes. Lacking individual names, the metatarsal bones are numbered from the me ...

s attached, a tail vertebra and the upper end of an ulna. If the remains represent a single prey animal, it is likely either a member of the Mesoeucrocodylia

Mesoeucrocodylia is the clade that includes Eusuchia and crocodyliforms formerly placed in the paraphyletic group Mesosuchia. The group appeared during the Early Jurassic, and continues to the present day.

Diagnosis

It was long known that Mes ...

or some lepidosaurian lizard-like animal; the size indicates the last possibility. In the descending tract of the duodenum two clusters of lizard scales are present and, more below, a fish vertebra. The jejunum shows a cluster of dozens of fish vertebrae, likely having belonged to a member of the Clupeomorpha. A second cluster of vertebrae was found at the jejunum-ileum boundary. The final tract of the rectum still holds faeces in which a piece of skin is visible showing seventeen scales of a fish of the Osteoglossiformes

Osteoglossiformes (Greek: "bony tongues") is a relatively primitive order of ray-finned fish that contains two sub-orders, the Osteoglossoidei and the Notopteroidei. All of at least 245 living species inhabit freshwater. They are found in South ...

that was nine seasons old, judging from the growth lines on the scales.

The food items found allow to reconstruct a sequence of food intakes: first a four to five centimetres long fish; secondly a smaller fish of two to three centimetres; next a ten to twelve centimetres long lizard; then a fifteen to forty, depending on the identification, centimetres long lepidosaurian lizard; and finally some indeterminate vertebrate(s). Together they represent a varied diet showing that ''Scipionyx'' was an opportunistic generalist. That swift lizards had been caught and sea fish washed ashore had been gathered necessitating a prolonged patrolling of the flood line, both indicate a good mobility. If the prey animal in the stomach really was forty centimetres long, it is highly unlikely that the equally-sized hatchling had been able to subdue it, indicating parental care.

Physiology

''Scipionyx'' is considered one of the most important fossil vertebrates ever discovered, after a long and painstaking "autopsy" revealed the unique fossilisation of portions of its internal organs. It is believed ''Scipionyx'' lived in a region filled with shallowlagoon

A lagoon is a shallow body of water separated from a larger body of water by a narrow landform, such as reefs, barrier islands, barrier peninsulas, or isthmuses. Lagoons are commonly divided into '' coastal lagoons'' (or ''barrier lagoons ...

s. These bodies of water were oxygen deficient, leading to the well-preserved ''Scipionyx'' specimen, much like the fine fossil preservation seen in Germany's ''Archaeopteryx