Scelidosaurus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Scelidosaurus'' (; with the intended meaning of "limb lizard", from

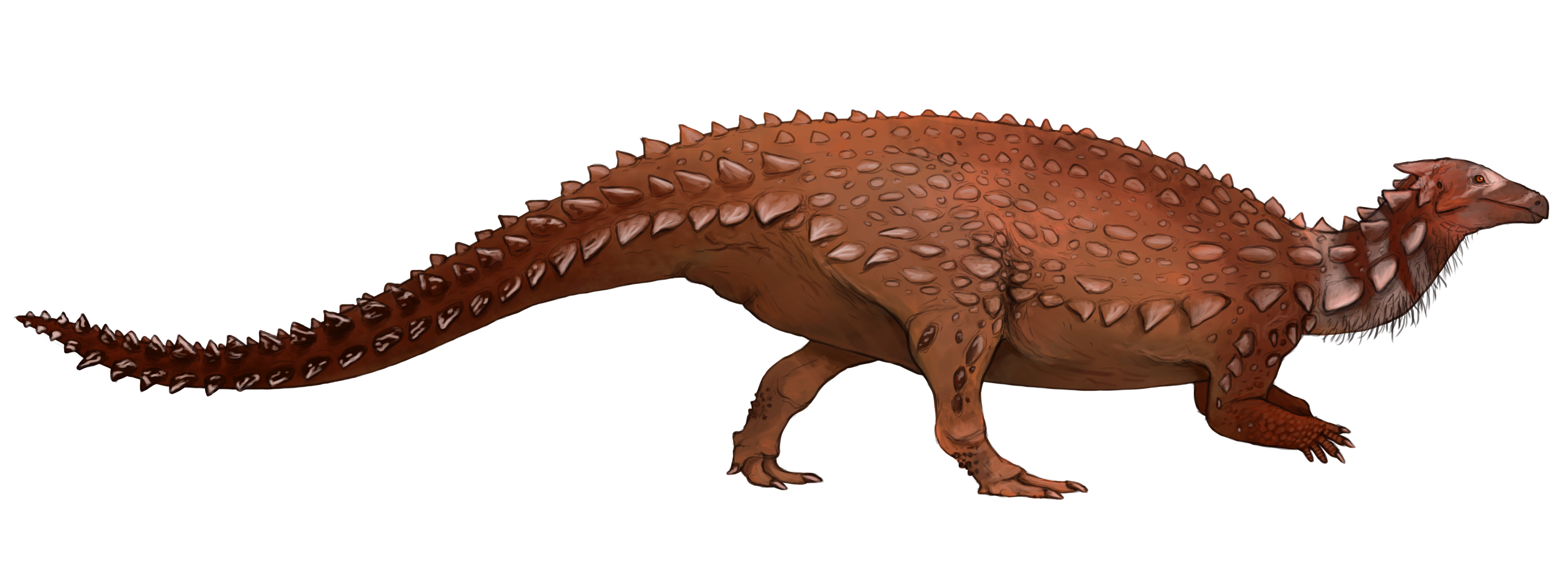

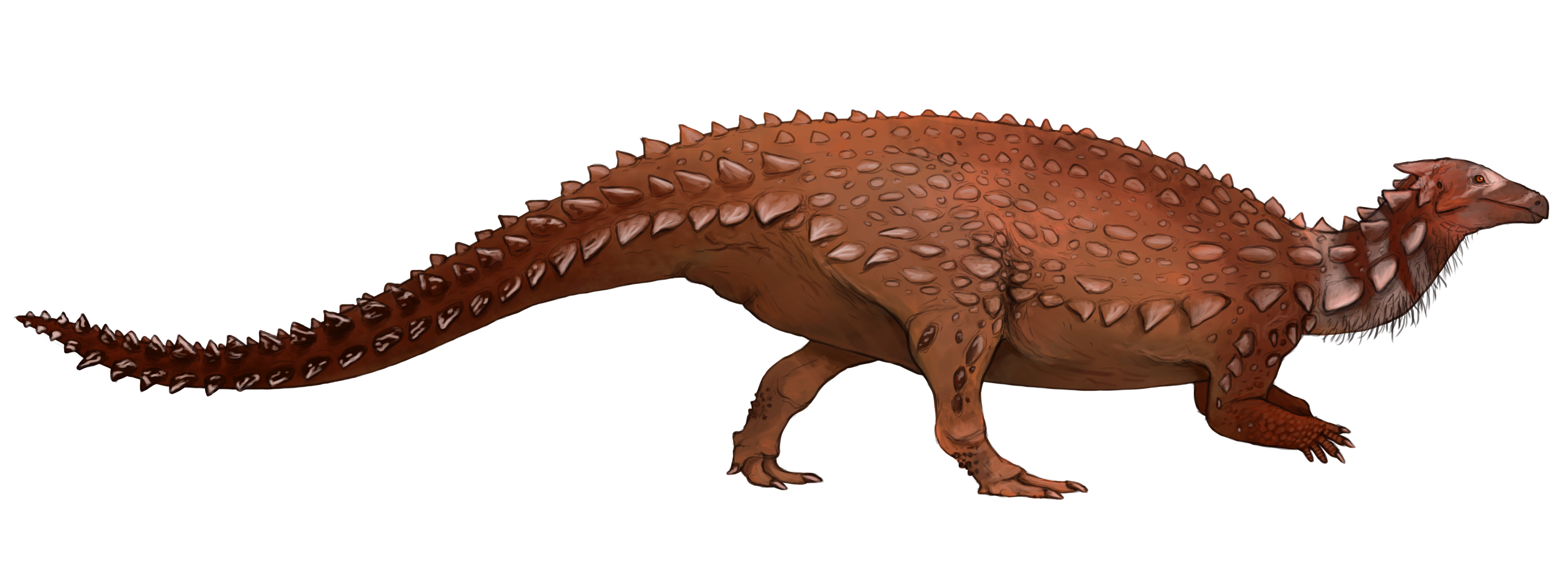

A full-grown ''Scelidosaurus'' was rather small compared to most later non-avian dinosaurs, but it was a medium-sized species in the Early Jurassic. Some scientists have estimated a length of 4 metres (13 ft). In 2010, Gregory S. Paul gave a body length of 3.8 metres (12.5 ft) and a weight of . ''Scelidosaurus'' was

A full-grown ''Scelidosaurus'' was rather small compared to most later non-avian dinosaurs, but it was a medium-sized species in the Early Jurassic. Some scientists have estimated a length of 4 metres (13 ft). In 2010, Gregory S. Paul gave a body length of 3.8 metres (12.5 ft) and a weight of . ''Scelidosaurus'' was

The head of ''Scelidosaurus'' was small, about twenty centimetres long, and elongated. The

The head of ''Scelidosaurus'' was small, about twenty centimetres long, and elongated. The

The

The  The

The

The most obvious feature of ''Scelidosaurus'' is its armour, consisting of bony

The most obvious feature of ''Scelidosaurus'' is its armour, consisting of bony  The neck had at each side two rows of large scutes. The osteoderms of the lower neck row were very large, flat and plate-like. The first osteoderms of the top neck rows formed a pair of unique three-pointed scutes directly behind the head. These points seem to have been connected by tendons to the rear joint processes, the postzygapophyses, of the axis vertebra. In general the scutes were larger at the front of the torso, the osteoderms diminishing towards the rear, especially on the surface of the thighs. The smallest flat round scutes might have filled the room between the larger osteoderm rows. Perhaps a row of vertical osteoderms was present on the upper arms. Compared to the later

The neck had at each side two rows of large scutes. The osteoderms of the lower neck row were very large, flat and plate-like. The first osteoderms of the top neck rows formed a pair of unique three-pointed scutes directly behind the head. These points seem to have been connected by tendons to the rear joint processes, the postzygapophyses, of the axis vertebra. In general the scutes were larger at the front of the torso, the osteoderms diminishing towards the rear, especially on the surface of the thighs. The smallest flat round scutes might have filled the room between the larger osteoderm rows. Perhaps a row of vertical osteoderms was present on the upper arms. Compared to the later

During the 1850s, quarry owner James Harrison of

During the 1850s, quarry owner James Harrison of  Owen had not indicated a

Owen had not indicated a  The neotype skeleton had been uncovered in the Black Ven Marl or Woodstone Nodule Bed, marine deposits of the

The neotype skeleton had been uncovered in the Black Ven Marl or Woodstone Nodule Bed, marine deposits of the

Apart from the neotype, other fossils are known of ''Scelidosaurus''. In 1888 Lydekker catalogued a large number of single bones, largely limb elements, and osteoderms, that had been acquired by the BMNH from the Norris collection. Owen in 1861 described a second, partial, skeleton of a juvenile animal, that later was added to the collection of Elizabeth Philpot and today is registered in the Lyme Regis Museum as specimen LYMPH 1997.37.4-10. As it was relatively large, Owen speculated, in the context of its presumed marine lifestyle, that ''Scelidosaurus'' might have been ovoviviparous. The short prepubis in this specimen convinced scientists that this process did not represent the main pubic body as some had thought, who had been unable to believe that the thin, backward-pointing, pubis with the Ornithischia was homologous to the forward-pointing much larger

Apart from the neotype, other fossils are known of ''Scelidosaurus''. In 1888 Lydekker catalogued a large number of single bones, largely limb elements, and osteoderms, that had been acquired by the BMNH from the Norris collection. Owen in 1861 described a second, partial, skeleton of a juvenile animal, that later was added to the collection of Elizabeth Philpot and today is registered in the Lyme Regis Museum as specimen LYMPH 1997.37.4-10. As it was relatively large, Owen speculated, in the context of its presumed marine lifestyle, that ''Scelidosaurus'' might have been ovoviviparous. The short prepubis in this specimen convinced scientists that this process did not represent the main pubic body as some had thought, who had been unable to believe that the thin, backward-pointing, pubis with the Ornithischia was homologous to the forward-pointing much larger  Between the years 1980 and 2000, three assumed fossils were discovered on a beach near The Gobbins in

Between the years 1980 and 2000, three assumed fossils were discovered on a beach near The Gobbins in

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

/ meaning 'rib of beef' and ''sauros''/ meaning 'lizard')Liddell & Scott (1980). Greek-English Lexicon, Abridged Edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK. is a genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nom ...

of herbivorous

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically adapted to eating plant material, for example foliage or marine algae, for the main component of its diet. As a result of their plant diet, herbivorous animals typically have mouthpar ...

armoured ornithischian

Ornithischia () is an extinct order of mainly herbivorous dinosaurs characterized by a pelvic structure superficially similar to that of birds. The name ''Ornithischia'', or "bird-hipped", reflects this similarity and is derived from the Greek st ...

dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

from the Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The Jurassic constitutes the middle period of ...

of the British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isl ...

.

''Scelidosaurus'' lived during the Early Jurassic

The Early Jurassic Epoch (geology), Epoch (in chronostratigraphy corresponding to the Lower Jurassic series (stratigraphy), Series) is the earliest of three epochs of the Jurassic Period. The Early Jurassic starts immediately after the Triassic-J ...

Period, during the Sinemurian

In the geologic timescale, the Sinemurian is an age and stage in the Early or Lower Jurassic Epoch or Series. It spans the time between 199.3 ± 2 Ma and 190.8 ± 1.5 Ma (million years ago). The Sinemurian is preceded by the Hettangian and ...

to Pliensbachian

The Pliensbachian is an age (geology), age of the geologic timescale and stage (stratigraphy), stage in the stratigraphic column. It is part of the Early Jurassic, Early or Lower Jurassic epoch (geology), Epoch or series (stratigraphy), Series an ...

stages around 191 million years ago

The abbreviation Myr, "million years", is a unit of a quantity of (i.e. ) years, or 31.556926 teraseconds.

Usage

Myr (million years) is in common use in fields such as Earth science and cosmology. Myr is also used with Mya (million years ago ...

. This genus and related genera at the time lived on the supercontinent

In geology, a supercontinent is the assembly of most or all of Earth's continental blocks or cratons to form a single large landmass. However, some geologists use a different definition, "a grouping of formerly dispersed continents", which leav ...

Laurasia

Laurasia () was the more northern of two large landmasses that formed part of the Pangaea supercontinent from around ( Mya), the other being Gondwana. It separated from Gondwana (beginning in the late Triassic period) during the breakup of Pa ...

. Its fossils have been found in the Charmouth Mudstone Formation

The Charmouth Mudstone Formation is a geological formation in England. It preserves fossils dating back to the early part of the Jurassic period (Sinemurian– Pliensbachian). It forms part of the lower Lias Group. It is most prominently expose ...

near Charmouth

Charmouth is a village and civil parish in west Dorset, England. The village is situated on the mouth of the River Char, around north-east of Lyme Regis. Dorset County Council estimated that in 2013 the population of the civil parish was 1,31 ...

in Dorset

Dorset ( ; archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the unitary authority areas of Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole and Dorset. Covering an area of , ...

, England, and these fossils are known for their excellent preservation. ''Scelidosaurus'' has been called the earliest complete dinosaur.Norman, David (2001). "''Scelidosaurus'', the earliest complete dinosaur" in ''The Armored Dinosaurs'', pp 3-24. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. . It is the most completely known dinosaur of the British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isl ...

. ''Scelidosaurus'' is currently the only classified dinosaur found in Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

. Despite this, a modern description only materialised in 2020. After initial finds in the 1850s, comparative anatomist Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomist and paleontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils.

Ow ...

named and described ''Scelidosaurus'' in 1859. Only one species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriat ...

, ''Scelidosaurus harrisonii'' named by Owen in 1861, is considered valid today, although one other species was proposed in 1996.

''Scelidosaurus'' was about long. It was a largely quadrupedal

Quadrupedalism is a form of locomotion where four limbs are used to bear weight and move around. An animal or machine that usually maintains a four-legged posture and moves using all four limbs is said to be a quadruped (from Latin ''quattuor ...

animal, feeding on low scrubby plants, the parts of which were bitten off by the small, elongated head to be processed in the large gut. ''Scelidosaurus'' was lightly armoured, protected by long horizontal rows of keeled oval scutes that stretched along the neck, back and tail.

One of the oldest known and most "primitive" of the thyreophora

Thyreophora ("shield bearers", often known simply as "armored dinosaurs") is a group of armored ornithischian dinosaurs that lived from the Early Jurassic until the end of the Cretaceous.

Thyreophorans are characterized by the presence of body ...

ns, the exact placement of ''Scelidosaurus'' within this group has been the subject of debate for nearly 150 years. This was not helped by the limited additional knowledge about the early evolution of armoured dinosaurs. Today most evidence suggests that Scelidosaurus is the most derived

Derive may refer to:

*Derive (computer algebra system), a commercial system made by Texas Instruments

* ''Dérive'' (magazine), an Austrian science magazine on urbanism

*Dérive, a psychogeographical concept

See also

*

*Derivation (disambiguation ...

of the known basal thyreophorans, either closely related to Ankylosauria

Ankylosauria is a group of herbivorous dinosaurs of the order Ornithischia. It includes the great majority of dinosaurs with armor in the form of bony osteoderms, similar to turtles. Ankylosaurs were bulky quadrupeds, with short, powerful limbs. ...

or Stegosauria

Stegosauria is a group of herbivorous ornithischian dinosaurs that lived during the Jurassic and early Cretaceous periods. Stegosaurian fossils have been found mostly in the Northern Hemisphere, predominantly in what is now North America, Europ ...

+Ankylosauria.

Description

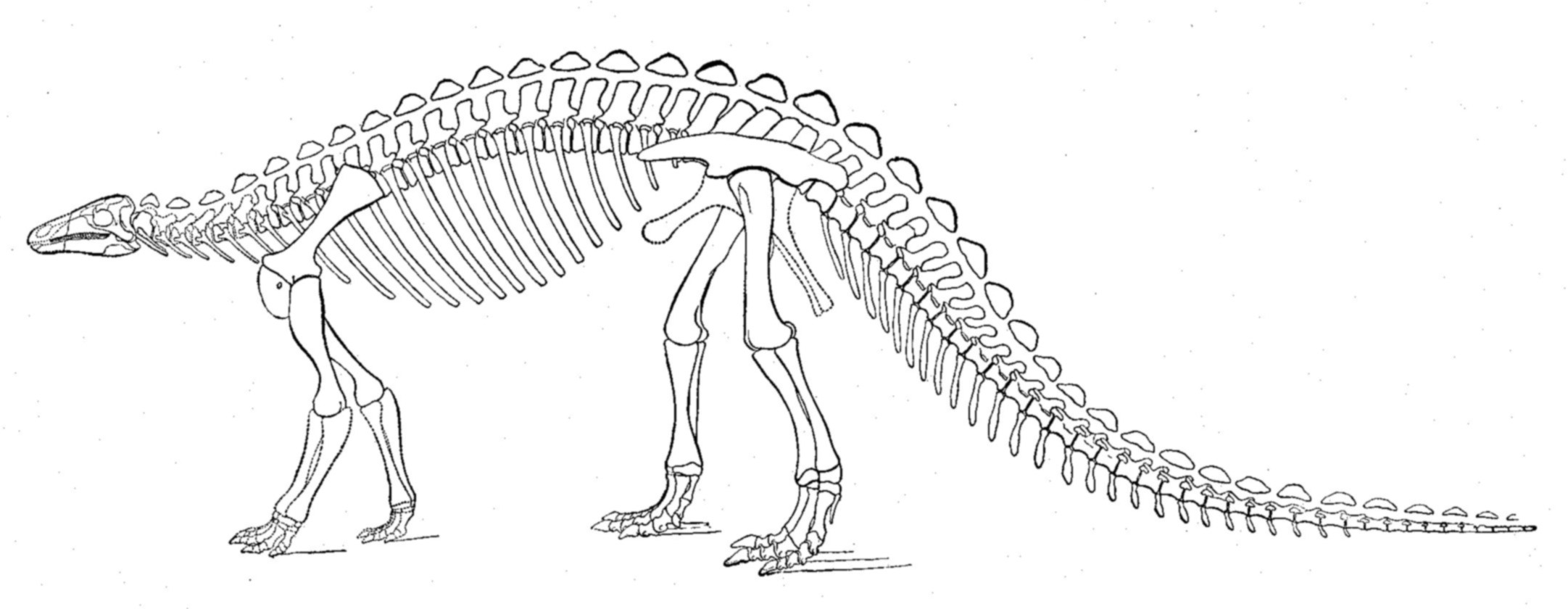

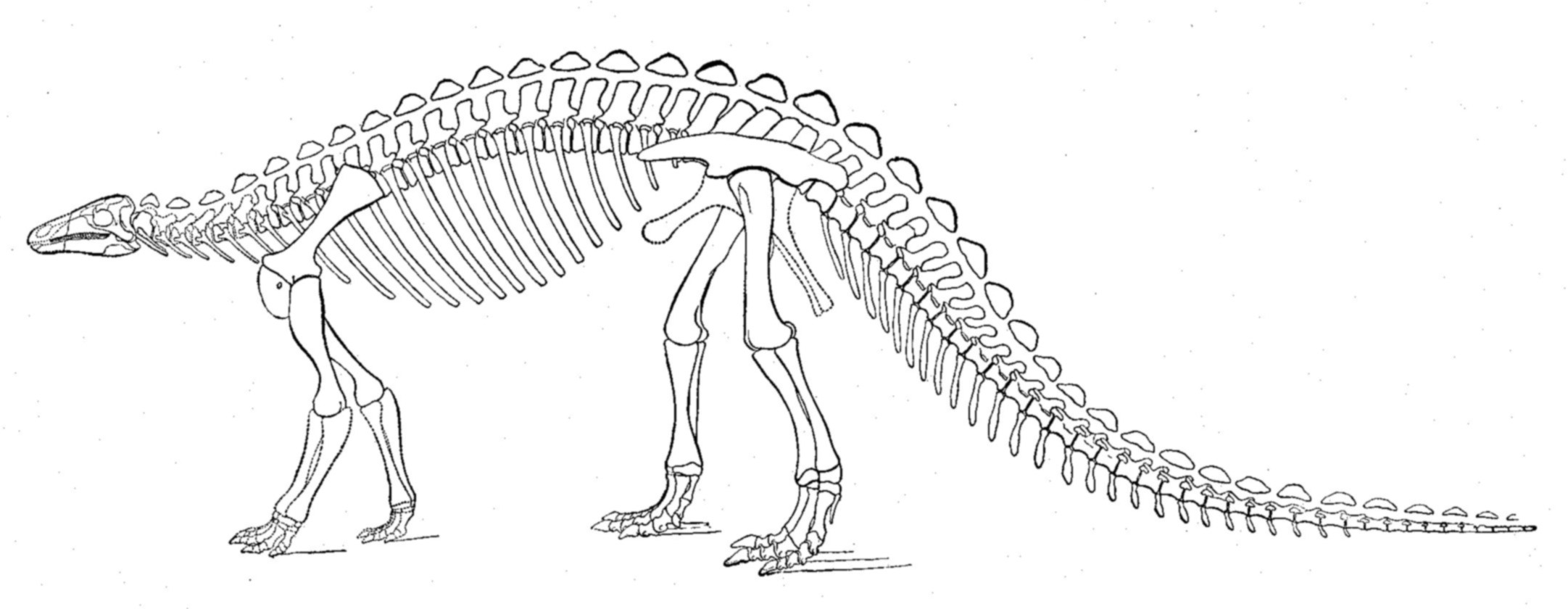

Size and posture

quadruped

Quadrupedalism is a form of locomotion where four limbs are used to bear weight and move around. An animal or machine that usually maintains a four-legged posture and moves using all four limbs is said to be a quadruped (from Latin ''quattuor' ...

al, with the hindlimbs longer than the forelimbs. It may have reared up on its hind legs to browse on foliage from trees, but its arms were relatively long, indicating a mostly quadrupedal posture. A trackway from the Holy Cross Mountains of Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

shows a scelidosaur like animal walking in a bipedal manner, hinting that ''Scelidosaurus'' may have been more proficient at bipedalism than previously thought.

Distinguishing traits

The first modern diagnosis was provided by David Bruce Norman in 2020. In a first article, Norman providedautapomorphies

In phylogenetics, an autapomorphy is a distinctive feature, known as a derived trait, that is unique to a given taxon. That is, it is found only in one taxon, but not found in any others or outgroup taxa, not even those most closely related to t ...

, unique derived characters, of the skull. The front snout bones, the premaxillae, have a common central rough extension, in life bearing a small upper beak. The nasal bone has on its upper outside a facet touching the inner side of the ascending branch of the premaxilla. The antorbital fenestra

An antorbital fenestra (plural: fenestrae) is an opening in the skull that is in front of the eye sockets. This skull character is largely associated with archosauriforms, first appearing during the Triassic Period. Among extant archosaurs, bird ...

is present as a bean-shaped depression, its lower edge formed by a sharp ridge. The central parietal crest on the skull roof is formed by two parallel crests separated by a narrow trough on the midline. The roof of the nasal cavity is formed by special plates above the vomers, called the "epivomers". The epipterygoid bone is shaped as a small conical vertical structure of which the base connects to the upper side of the pterygoid bone by means of a lateral flat surface. The basioccipital has large oblique facets on the lower sides. The opisthotic has an expanded pedicel with facets on its underside. Elongated epistyloid bones project obliquely to the rear and below, from the back of the skull. A small spur-like structure on the upper edge of the paroccipital process encases the posttemporal fenestra. The rear of the skull is fused on its upper edge with a pair of large curved horn-shaped osteoderms. The lower jaw shows only little exostosis, limited to the angular, and lacking an attached osteoderm.

Skull

The head of ''Scelidosaurus'' was small, about twenty centimetres long, and elongated. The

The head of ''Scelidosaurus'' was small, about twenty centimetres long, and elongated. The skull

The skull is a bone protective cavity for the brain. The skull is composed of four types of bone i.e., cranial bones, facial bones, ear ossicles and hyoid bone. However two parts are more prominent: the cranium and the mandible. In humans, th ...

was low in side view and triangular in top view, longer than it was wide, similar to that of earlier ornithischian

Ornithischia () is an extinct order of mainly herbivorous dinosaurs characterized by a pelvic structure superficially similar to that of birds. The name ''Ornithischia'', or "bird-hipped", reflects this similarity and is derived from the Greek st ...

s. The snout, largely formed by the nasal bone

The nasal bones are two small oblong bones, varying in size and form in different individuals; they are placed side by side at the middle and upper part of the face and by their junction, form the bridge of the upper one third of the nose.

Ea ...

s, was flat on top. ''Scelidosaurus'' still had the five pairs of fenestra

A fenestra (fenestration; plural fenestrae or fenestrations) is any small opening or pore, commonly used as a term in the biological sciences. It is the Latin word for "window", and is used in various fields to describe a pore in an anatomical st ...

e (skull openings) seen in basal ornithischians: apart from the nostrils and eye sockets which are present in all basal dinosaurs, the '' fenestra antorbitalis'' and the upper and lower temporal fenestrae were not closed or overgrown, as with many later armoured forms. In fact, the upper temporal fenestrae were very large, forming conspicuous round openings in the top of the rear skull, serving as attachment areas for the powerful muscles that closed the lower jaws. The eye socket was slightly overshadowed in its front part by a brow ridge that has been seen as the prefrontal bone

The prefrontal bone is a bone separating the lacrimal and frontal bones in many tetrapod skulls. It first evolved in the sarcopterygian clade Rhipidistia, which includes lungfish and the Tetrapodomorpha. The prefrontal is found in most mo ...

. In 2020, Norman concluded that it was a fused palpebral bone. Behind it, the upper rim of the eye socket was formed by the supraorbital bone

Supraorbital refers to the region immediately above the eye sockets, where in humans the eyebrows are located. It denotes several anatomical features, such as:

*Supraorbital artery

*Supraorbital foramen

* Supraorbital gland

*Supraorbital nerve

...

. A study by Susannah Maidment e.a. concluded that juvenile specimens show that this bone was a fusion of three elements, one in front, the next in rear, and the third at the inner side.

The premaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammal has ...

, the bone forming the snout tip, was short and no predentary, the bone core of the lower beak on the tip of the stout lower jaws, has been found, so the horny beak that is assumed present with all ornithischians was likely very short. Its teeth were longer and more triangular in side view than in later armoured dinosaurs. There were at least five teeth in each premaxilla, and at least nineteen in the maxilla

The maxilla (plural: ''maxillae'' ) in vertebrates is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. T ...

and sixteen in the dentary

In anatomy, the mandible, lower jaw or jawbone is the largest, strongest and lowest bone in the human facial skeleton. It forms the lower jaw and holds the lower teeth in place. The mandible sits beneath the maxilla. It is the only movable bone ...

of the lower jaw. However, the number of maxillary and dentary teeth were established with the incomplete skull of one of the first specimens found; the actual numbers might have ranged up to about two dozen, perhaps twenty-six for the lower jaw. The premaxillary teeth were somewhat longer and recurved. To the rear, they gradually approach the form of the maxillary teeth, beginning to show denticles. The crowns of the maxillary and dentary teeth have denticles on their edges and a swollen basis

The ascending branches of the paired premaxillae notched the combined nasal bones, whereas the opposite was usual in ornithischians. The frontal bones were covered by a halo of fine ridges; these indicate the presence of keratin

Keratin () is one of a family of structural fibrous proteins also known as ''scleroproteins''. Alpha-keratin (α-keratin) is a type of keratin found in vertebrates. It is the key structural material making up Scale (anatomy), scales, hair, Nail ...

ous plates, as with modern turtles

Turtles are an order of reptiles known as Testudines, characterized by a special shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Cryptodira (hidden necked tu ...

. At the front of the braincase, paired hatchet-shaped ossified orbitosphenoid

The lesser wings of the sphenoid or orbito-sphenoids are two thin triangular plates, which arise from the upper and anterior parts of the body, and, projecting lateralward, end in sharp points ig. 1

In some animals they remain as separate bones c ...

s formed the floor of the olfactory lobes of the brain. The skull of the neotype was damaged by a paleoichthyologist resulting in the detachment of triangular plates from the palate. These elements had been sketched by Norman in the seventies prior to the incident and interpreted as parts of the pterygoids, but in 2020 he concluded that they were special bones covering the roof of the nasal cavity, which he named the "epivomers". These are not known from any other animal.

Postcranial skeleton

The

The vertebral column

The vertebral column, also known as the backbone or spine, is part of the axial skeleton. The vertebral column is the defining characteristic of a vertebrate in which the notochord (a flexible rod of uniform composition) found in all chordate ...

of ''Scelidosaurus'' contained at least six neck vertebrae, seventeen dorsal vertebra

In vertebrates, thoracic vertebrae compose the middle segment of the vertebral column, between the cervical vertebrae and the lumbar vertebrae. In humans, there are twelve thoracic vertebrae and they are intermediate in size between the cervical ...

e, four sacral vertebra

The sacrum (plural: ''sacra'' or ''sacrums''), in human anatomy, is a large, triangular bone at the base of the spine that forms by the fusing of the sacral vertebrae (S1S5) between ages 18 and 30.

The sacrum situates at the upper, back part ...

e and at least thirty-five tail vertebrae.

Though perhaps the actual total of cervical vertebra

In tetrapods, cervical vertebrae (singular: vertebra) are the vertebrae of the neck, immediately below the skull. Truncal vertebrae (divided into thoracic and lumbar vertebrae in mammals) lie caudal (toward the tail) of cervical vertebrae. In sa ...

e was as high as seven or eight, the neck was only moderately long. The torso

The torso or trunk is an anatomical term for the central part, or the core, of the body of many animals (including humans), from which the head, neck, limbs, tail and other appendages extend. The tetrapod torso — including that of a hu ...

was relatively flat in side view, however, despite the belly being broad, it was not extremely vertically compressed as with ankylosaurs but taller than wide. The last three dorsal vertebrae had no ribs. The spines of the sacral vertebrae touched each other but were not fused into a supraneural plate. The quickly tapering tail was relatively short, probably representing about half of body length. The tail chevrons were strongly inclined to the rear. The hip area and tail base were stiffened by large numbers of ossified tendons.

The

The scapula

The scapula (plural scapulae or scapulas), also known as the shoulder blade, is the bone that connects the humerus (upper arm bone) with the clavicle (collar bone). Like their connected bones, the scapulae are paired, with each scapula on eith ...

was short with a moderately expanded upper end. The coracoid

A coracoid (from Greek κόραξ, ''koraks'', raven) is a paired bone which is part of the shoulder assembly in all vertebrates except therian mammals (marsupials and placentals). In therian mammals (including humans), a coracoid process is prese ...

was circular in side view. The elements of the forelimb were generally moderately long, straight and stout. The hand is only known from recent discoveries and has not yet been described. In the rather wide pelvis

The pelvis (plural pelves or pelvises) is the lower part of the trunk, between the abdomen and the thighs (sometimes also called pelvic region), together with its embedded skeleton (sometimes also called bony pelvis, or pelvic skeleton).

The ...

, the ilium was straight in side view. Its front blade was rod-shaped and moderately splayed to the outside, creating room for the belly. This was reinforced by the sacral ribs becoming longer towards the front. The sacral ribs were wider at their attachment areas with the ilium, but were not fused into a sacral yoke. The pubis featured a short prepubis. The pubis shaft was straight, running parallel to a straight ischium

The ischium () form ...

shaft that was transversely flattened at its lower end. The thighbone was straight in side view, in front view it was somewhat bowed to the outside. Its head was not separated from the shaft by a real neck. While the major trochanter

A trochanter is a tubercle of the femur near its joint with the hip bone. In humans and most mammals, the trochanters serve as important muscle attachment sites. Humans are known to have three trochanters, though the anatomic "normal" includes ...

was at about the same level as the head, the lower minor trochanter was separated from both by a deep cleft. At it rear side, the femur

The femur (; ), or thigh bone, is the proximal bone of the hindlimb in tetrapod vertebrates. The head of the femur articulates with the acetabulum in the pelvic bone forming the hip joint, while the distal part of the femur articulates ...

mid-shaft featured a well-developed drooping fourth trochanter, a process for the attachment of the retractor tail muscle, the '' Musculus caudofemoralis longus''. The lower leg was somewhat shorter than the thighbone. The tibia

The tibia (; ), also known as the shinbone or shankbone, is the larger, stronger, and anterior (frontal) of the two bones in the leg below the knee in vertebrates (the other being the fibula, behind and to the outside of the tibia); it conn ...

had a wide upper end, with a cnemial crest The cnemial crest is a crestlike prominence located at the front side of the head of the tibiotarsus or tibia in the legs of many mammals and reptiles (including birds and other dinosaurs). The main extensor muscle of the thigh

In human anat ...

protruding well to the front. The tibia lower end was also robust and rotated about 70° compared to the upper part, turning the foot strongly to the outside. The foot was very large and wide. The fifth metatarsal

The metatarsal bones, or metatarsus, are a group of five long bones in the foot, located between the tarsal bones of the hind- and mid-foot and the phalanges of the toes. Lacking individual names, the metatarsal bones are numbered from the me ...

was only rudimentary but the other four were robust. ''Scelidosaurus'' had four large toes, with the innermost digit being the smallest. The fourth metatarsal was short but its toe was long and built to be splayed to the outside of the foot, to improve the stability. The claws were flat, hoof-shaped and curved to the inside.

Armour

The most obvious feature of ''Scelidosaurus'' is its armour, consisting of bony

The most obvious feature of ''Scelidosaurus'' is its armour, consisting of bony scute

A scute or scutum (Latin: ''scutum''; plural: ''scuta'' "shield") is a bony external plate or scale overlaid with horn, as on the shell of a turtle, the skin of crocodilians, and the feet of birds. The term is also used to describe the anterior po ...

s embedded in the skin. These osteoderm

Osteoderms are bony deposits forming scales, plates, or other structures based in the dermis. Osteoderms are found in many groups of extant and extinct reptiles and amphibians, including lizards, crocodilians, frogs, temnospondyls (extinct amp ...

s were arranged in horizontal parallel rows down the animal's body. Osteoderms are today found in the skin of crocodile

Crocodiles (family Crocodylidae) or true crocodiles are large semiaquatic reptiles that live throughout the tropics in Africa, Asia, the Americas and Australia. The term crocodile is sometimes used even more loosely to include all extant me ...

s, armadillo

Armadillos (meaning "little armored ones" in Spanish) are New World placental mammals in the order Cingulata. The Chlamyphoridae and Dasypodidae are the only surviving families in the order, which is part of the superorder Xenarthra, alo ...

s and some lizard

Lizards are a widespread group of squamate reptiles, with over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most oceanic island chains. The group is paraphyletic since it excludes the snakes and Amphisbaenia altho ...

s. The osteoderms of ''Scelidosaurus'' ranged in both size and shape. Most were smaller or larger oval plates with a high keel on the outside, the highest point of the keel positioned more to the rear. Some scutes were small, flat and hollowed-out at the inside. The larger keeled scutes were aligned in regular horizontal rows. There were three rows of these along each side of the torso. The scutes of the lowest, lateral, row were more conical, rather than the blade-like osteoderms of ''Scutellosaurus

''Scutellosaurus'' ( ) is a genus of thyreophoran ornithischian dinosaur that lived approximately 196 million years ago during the early part of the Jurassic Period in what is now Arizona, USA. It is classified in Thyreophora, the armoured di ...

''.Martill, D.M., Batten, D.J., and Loydell, D.K. (2000). A New Specimen of the Thyreophoran Dinosaur cf. ''Scelidosaurus'' with Soft Tissue Preservation. ''Palaeontology'', Vol. 43, Part 3, 2000, pp. 549-559. Between these main series, one or two rows of smaller oval keeled scutes were present. There were in total four rows of large scutes on the tail: one at the top midline, one at the midline of the underside, and one at each tail side. Whether the midline tail scutes continued over the torso and neck to the front is unknown and unlikely for the neck, though ''Scelidosaurus'' is often pictured this way.

The neck had at each side two rows of large scutes. The osteoderms of the lower neck row were very large, flat and plate-like. The first osteoderms of the top neck rows formed a pair of unique three-pointed scutes directly behind the head. These points seem to have been connected by tendons to the rear joint processes, the postzygapophyses, of the axis vertebra. In general the scutes were larger at the front of the torso, the osteoderms diminishing towards the rear, especially on the surface of the thighs. The smallest flat round scutes might have filled the room between the larger osteoderm rows. Perhaps a row of vertical osteoderms was present on the upper arms. Compared to the later

The neck had at each side two rows of large scutes. The osteoderms of the lower neck row were very large, flat and plate-like. The first osteoderms of the top neck rows formed a pair of unique three-pointed scutes directly behind the head. These points seem to have been connected by tendons to the rear joint processes, the postzygapophyses, of the axis vertebra. In general the scutes were larger at the front of the torso, the osteoderms diminishing towards the rear, especially on the surface of the thighs. The smallest flat round scutes might have filled the room between the larger osteoderm rows. Perhaps a row of vertical osteoderms was present on the upper arms. Compared to the later Ankylosauria

Ankylosauria is a group of herbivorous dinosaurs of the order Ornithischia. It includes the great majority of dinosaurs with armor in the form of bony osteoderms, similar to turtles. Ankylosaurs were bulky quadrupeds, with short, powerful limbs. ...

, ''Scelidosaurus'' was lightly armoured, without continuous plating, spikes or pelvic shield. Rough areas on the skull and lower jaws indicate the presence of skin ossifications.

Some of the latest specimens found show partly different osteoderms including scutes on which the keel is more like a thorn or spike. These specimens also seem to have little horns on the rear corners of the head, placed on the squamosal bone The squamosal is a skull bone found in most reptiles, amphibians, and birds. In fishes, it is also called the pterotic bone.

In most tetrapods, the squamosal and quadratojugal bones form the cheek series of the skull. The bone forms an ancestral c ...

s.

Fossilized skin impressions have also been found. Between the bony scutes, ''Scelidosaurus'' had rounded non-overlapping scales like the present Gila monster.Lambert D (1993). ''The Ultimate Dinosaur Book''. Dorling Kindersley, New York, 110-113. Between the large scutes, very small (5-10 millimetres .2-0.4 in flat "granules" of bone were perhaps distributed within the skin. In the later Ankylosauria, these small scutes may have developed into larger scutes, fusing into the multi-osteodermal plate armour seen in genera such as ''Ankylosaurus

''Ankylosaurus'' is a genus of armored dinosaur. Its fossils have been found in geological formations dating to the very end of the Cretaceous Period, about 68–66 million years ago, in western North America, making it among the last of th ...

''.

History of study

Discovery, naming, and type specimens

During the 1850s, quarry owner James Harrison of

During the 1850s, quarry owner James Harrison of Charmouth

Charmouth is a village and civil parish in west Dorset, England. The village is situated on the mouth of the River Char, around north-east of Lyme Regis. Dorset County Council estimated that in 2013 the population of the civil parish was 1,31 ...

, West Dorset of England found fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

s from the cliffs of Black Ven

Black Ven is a cliff in Dorset, England between the towns of Charmouth and Lyme Regis. The cliffs reach a height of . It is part of the Jurassic Coast World Heritage Site. Nearby is an undercliff with an ammonite pavement. The area is popular wit ...

between Charmouth and Lyme Regis

Lyme Regis is a town in west Dorset, England, west of Dorchester and east of Exeter. Sometimes dubbed the "Pearl of Dorset", it lies by the English Channel at the Dorset– Devon border. It has noted fossils in cliffs and beaches on the He ...

, that were quarried, possibly for raw material for the manufacture of cement

A cement is a binder, a chemical substance used for construction that sets, hardens, and adheres to other materials to bind them together. Cement is seldom used on its own, but rather to bind sand and gravel (aggregate) together. Cement mixe ...

. Some of these he gave to the collector and retired general surgeon

General surgery is a surgical specialty that focuses on alimentary canal and abdominal contents including the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, liver, pancreas, gallbladder, appendix and bile ducts, and often the thyroid g ...

Henry Norris. In 1858, Norris and Harrison sent some fragmentary limb bones to Professor Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomist and paleontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils.

Ow ...

of the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

(Natural History), London (today the Natural History Museum

A natural history museum or museum of natural history is a scientific institution with natural history collections that include current and historical records of animals, plants, fungi, ecosystems, geology, paleontology, climatology, and more. ...

). Among them was a left thighbone, specimen GSM 109560. In 1859, Owen named the genus ''Scelidosaurus'' in an entry about palaeontology in the ''Encyclopædia Britannica

The (Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various t ...

''. The lemma

Lemma may refer to:

Language and linguistics

* Lemma (morphology), the canonical, dictionary or citation form of a word

* Lemma (psycholinguistics), a mental abstraction of a word about to be uttered

Science and mathematics

* Lemma (botany), ...

text contained a diagnosis, implicating that the genus was validly named and was not a ''nomen nudum

In taxonomy, a ''nomen nudum'' ('naked name'; plural ''nomina nuda'') is a designation which looks exactly like a scientific name of an organism, and may have originally been intended to be one, but it has not been published with an adequate desc ...

'', despite the fact that the definition was vague and no specimens were identified.Charig, A.J. & Newman, B.H.†, 1992, "''Scelidosaurus harrisonii'' Owen, 1861 (Reptilia, Ornithischia): proposed replacement in inappropriate lectotype", ''Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature'', 49: 280–283 Owen intended to call the dinosaur "hindlimb saurian" but confused the Greek word σκέλος, , "hindlimb", with σκελίς, , "rib of beef".R. Owen, 1861, ''A monograph of a fossil dinosaur (Scelidosaurus harrisonii, Owen) of the Lower Lias, part I. Monographs on the British fossil Reptilia from the Oolitic Formations 1'' pp 14 The name was inspired by the strong development of the hind leg. Afterwards Harrison sent a knee joint, a claw (GSM 109561), a juvenile specimen and a skull to Owen, that were described in 1861. On that occasion the type species

In zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the species that contains the biological type specim ...

''Scelidosaurus harrisonii'' was named, the specific name honouring Harrison. The skull later was revealed to be part of a nearly complete skeleton, that was described by Owen in 1863.

British palaeontologist David Bruce Norman has stressed how remarkable it is that Owen, who previously had propounded that dinosaurs were active quadrupedal animals, largely neglected ''Scelidosaurus'' though it could serve as a prime example of this hypothesis and its fossil was one of the most complete dinosaurs found at that time. Norman explained this by Owen's excessive workload in this period, including several administrative functions, polemics with fellow-scientists and the study of a large number of even more interesting newly discovered extinct animals, such as ''Archaeopteryx

''Archaeopteryx'' (; ), sometimes referred to by its German name, "" ( ''Primeval Bird''), is a genus of bird-like dinosaurs. The name derives from the ancient Greek (''archaīos''), meaning "ancient", and (''ptéryx''), meaning "feather" ...

''. Norman also pointed out that Owen in 1861 suggested a lifestyle for ''Scelidosaurus'' that is very different from present ideas: it would have been a fish-eater and partially sea-dwelling.

Owen had not indicated a

Owen had not indicated a holotype

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of seve ...

. In 1888, Richard Lydekker

Richard Lydekker (; 25 July 1849 – 16 April 1915) was an English naturalist, geologist and writer of numerous books on natural history.

Biography

Richard Lydekker was born at Tavistock Square in London. His father was Gerard Wolfe Lydekker ...

while cataloguing the BMNH fossils, designated some of the hindlimb fragments described in 1861, specimen BMNH 39496 consisting of a lower part of a femur and an upper part of the tibia and fibula, together forming a knee joint, as the type specimen, hereby implicitly choosing them as the lectotype

In biology, a type is a particular specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally attached. In other words, a type is an example that serves to anchor or centralizes the ...

of ''Scelidosaurus''. Lydekker gave no reason for this choice;Lydekker, R., 1888, ''Catalogue of the Fossil Reptilia and Amphibia in the British Museum. Part 1. Containing the Orders Ornithosauria, Crocodilia, Dinosauria, Squamata, Rhynchocephalia and Proterosauria. British Museum (Natural History)'' perhaps he was motivated by their larger size. Unfortunately, mixed in with the ''Scelidosaurus'' fossils had been the partial remains of a theropod dinosaur and the femur and tibia thus belonged to such a carnivore; this was not discovered until 1968 by Bernard Newman.Newman, B.H. (1968) The Jurassic dinosaur ''Scelidosaurus harrisoni'', Owen. ''Palaeontology'' 11 (1), 40-3. The same year, B. H. Newman suggested to have Lydekker's selection of the knee joint as the lectotype officially rescinded by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature

The International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) is an organization dedicated to "achieving stability and sense in the scientific naming of animals". Founded in 1895, it currently comprises 26 commissioners from 20 countries.

Orga ...

, as the joint was in his opinion from a species related to ''Megalosaurus

''Megalosaurus'' (meaning "great lizard", from Greek , ', meaning 'big', 'tall' or 'great' and , ', meaning 'lizard') is an extinct genus of large carnivorous theropod dinosaurs of the Middle Jurassic period (Bathonian stage, 166 million years ...

''. Eventually, after Newman had already died, Alan Jack Charig actually filed a request in 1992. In 1994 the ICZN reacted positively, in Opinion 1788 deciding that the skull and skeleton, specimen BMNH R.1111, would be the neotype

In biology, a type is a particular specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally attached. In other words, a type is an example that serves to anchor or centralizes the ...

of ''Scelidosaurus''. The knee joint was in 1995 by Samuel Welles ''et al.'' informally assigned to a " Merosaurus", which name has not yet been validly published. It more likely belongs to some member of the Coelophysoidea

Coelophysoidea were common dinosaurs of the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic periods. They were widespread geographically, probably living on all continents. Coelophysoids were all slender, carnivorous forms with a superficial similarity to the ...

or Neoceratosauria. It has also been established by Newman and confirmed by Roger Benson

Roger is a given name, usually masculine, and a surname. The given name is derived from the Old French personal names ' and '. These names are of Germanic origin, derived from the elements ', ''χrōþi'' ("fame", "renown", "honour") and ', ' ( ...

that the original left thighbone, GSM 109560, belonged to a theropod.Benson, R., 2010, "The osteology of ''Magnosaurus nethercombensis'' (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Bajocian (Middle Jurassic) of the United Kingdom and a re-examination of the oldest records of tetanurans", ''Journal of Systematic Palaeontology'' 8(1): 131-146

The neotype skeleton had been uncovered in the Black Ven Marl or Woodstone Nodule Bed, marine deposits of the

The neotype skeleton had been uncovered in the Black Ven Marl or Woodstone Nodule Bed, marine deposits of the Charmouth Mudstone Formation

The Charmouth Mudstone Formation is a geological formation in England. It preserves fossils dating back to the early part of the Jurassic period (Sinemurian– Pliensbachian). It forms part of the lower Lias Group. It is most prominently expose ...

, dating from the late Sinemurian

In the geologic timescale, the Sinemurian is an age and stage in the Early or Lower Jurassic Epoch or Series. It spans the time between 199.3 ± 2 Ma and 190.8 ± 1.5 Ma (million years ago). The Sinemurian is preceded by the Hettangian and ...

stage, about 191 million years ago.Barrett, P.M. and Maidment, S.C.R., 2011, "Dinosaurs of Dorset: Part III, the ornithischian dinosaurs (Dinosauria, Ornithischia) with additional comments on the sauropods", ''Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society'' 132: 145–163 It consists of a rather complete skeleton with skull and lower jaws. Only the snout tip, the neck base, the forelimbs and the tail end are missing. Hundreds of osteoderms were found in connection with the skeleton, many more or less in their original position. From the 1960s onward, this fossil was further prepared by Ronald Croucher using acid baths to free the bones from the surrounding matrix, a method perfected for the Charmouth fossils. In 1992, Charig reported that only a single block had yet to be treated, but he died before the results could be published. Norman, who intended to complete this task, had revealed some new anatomical details in 2004. Apart from these, a modern description was largely lacking. In 2020, Norman published articles on the skull and the postcrania, also taking later finds into account. It transpired that the acid baths had, through leakages, severely deteriorated the condition of the bones, further mishandling leading to breakage and crumbling.

Additional specimens

Apart from the neotype, other fossils are known of ''Scelidosaurus''. In 1888 Lydekker catalogued a large number of single bones, largely limb elements, and osteoderms, that had been acquired by the BMNH from the Norris collection. Owen in 1861 described a second, partial, skeleton of a juvenile animal, that later was added to the collection of Elizabeth Philpot and today is registered in the Lyme Regis Museum as specimen LYMPH 1997.37.4-10. As it was relatively large, Owen speculated, in the context of its presumed marine lifestyle, that ''Scelidosaurus'' might have been ovoviviparous. The short prepubis in this specimen convinced scientists that this process did not represent the main pubic body as some had thought, who had been unable to believe that the thin, backward-pointing, pubis with the Ornithischia was homologous to the forward-pointing much larger

Apart from the neotype, other fossils are known of ''Scelidosaurus''. In 1888 Lydekker catalogued a large number of single bones, largely limb elements, and osteoderms, that had been acquired by the BMNH from the Norris collection. Owen in 1861 described a second, partial, skeleton of a juvenile animal, that later was added to the collection of Elizabeth Philpot and today is registered in the Lyme Regis Museum as specimen LYMPH 1997.37.4-10. As it was relatively large, Owen speculated, in the context of its presumed marine lifestyle, that ''Scelidosaurus'' might have been ovoviviparous. The short prepubis in this specimen convinced scientists that this process did not represent the main pubic body as some had thought, who had been unable to believe that the thin, backward-pointing, pubis with the Ornithischia was homologous to the forward-pointing much larger pubic bone

In vertebrates, the pubic region ( la, pubis) is the most forward-facing ( ventral and anterior) of the three main regions making up the coxal bone. The left and right pubic regions are each made up of three sections, a superior ramus, inferior ...

in most reptilian groups.

In more recent times, new discoveries have been made at Charmouth, not through commercial quarrying but by the efforts of amateur palaeontologists. In 1968 a second partial juvenile skeleton was described, specimen BMNH R6704, that had already been reported in 1959. Found by geologist James Frederick Jackson (1894-1966) of Charmouth, it is from a slightly younger layer, the Stonebarrow Marl Member dating to the early Pliensbachian

The Pliensbachian is an age (geology), age of the geologic timescale and stage (stratigraphy), stage in the stratigraphic column. It is part of the Early Jurassic, Early or Lower Jurassic epoch (geology), Epoch or series (stratigraphy), Series an ...

, about 190 million years old. In 1985 Simon Barnsley, David Costain and Peter Langham excavated a partial skeleton including a very complete skull and skin impressions, which was sold to the Bristol Museum

Bristol Museum & Art Gallery is a large museum and art gallery in Bristol, England. The museum is situated in Clifton, about from the city centre. As part of Bristol Culture it is run by the Bristol City Council with no entrance fee. It holds ...

where it is registered as specimen BRSMG CE12785. Specimen CAMSMX.39256 is part of the collection of the Sedgwick Museum

The Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences, is the geology museum of the University of Cambridge. It is part of the Department of Earth Sciences and is located on the university's Downing Site in Downing Street, central Cambridge, England. The Sedgw ...

at Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

. Several specimens remain undescribed because they are in private collections. These include a 3.1 metres (ten feet) long skeleton found by David Sole in 2000, perhaps the most complete non-avian dinosaur exemplar ever discovered in the British Isles. All elements of the skeleton are now known. The finds by Sole differ from the neotype in details of the armour and might represent a separate taxon or reflect sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where the sexes of the same animal and/or plant species exhibit different morphological characteristics, particularly characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most an ...

.Naish, D. & Martill, D.M., 2007, "Dinosaurs of Great Britain and the role of the Geological Society of London in their discovery: basal Dinosauria and Saurischia", ''Journal of the Geological Society, London'', 164: 493–510 In 2020, Norman denied this.

Between the years 1980 and 2000, three assumed fossils were discovered on a beach near The Gobbins in

Between the years 1980 and 2000, three assumed fossils were discovered on a beach near The Gobbins in Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label=Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is #Descriptions, variously described as ...

by palaeontologist Roger Byrne. Exact geologic provenance is not reported for any of the specimens, but the very dark colouration of the specimens indicate (through means of comparison to marine fossils in other Northern Irish localities) they hail from Lias Group

The Lias Group or Lias is a lithostratigraphic unit (a sequence of rock strata) found in a large area of western Europe, including the British Isles, the North Sea, the Low Countries and the north of Germany. It consists of marine limestones, sh ...

rocks, likely from either the Planorbis Zone or the Pre-planorbis Zone of the Waterloo Mudstone Formation. The specimens include BELUM K3998, a proximal femur fragment discovered in January 1980; BELUM K12493, the fragment of a tibia shaft discovered in April 1981; and BELUM K2015.1.54, a small pentagonal object discovered in 2000. Histologist Robin Reid recognized the first specimen as dinosaurian due to its bone texture and structure, and reported it as such in 1989, suspecting it may have belonged to ''Scelidosaurus'' or a similar animal. Byrne then recognized the tibia specimen as dinosaurian using similar identifiers; it was assumed, based on association, the two specimens came from the same animal. The pentagonal specimen was then assumed to be a scelidosaur osteoderm on the same logic. These specimens, alongside another discovered by fossil collector William Gray sometime in the late 19th or early 20th century, were formally studied by Michael J. Simms and colleagues and a study was published on them in the journal ''Proceedings of the Geologists' Association'' in December 2021. The assignment of the femoral fragment was upheld, with a clear ornithischian identity and with size and morphology specifically very similar to ''Scelidosaurus'' and unlike close relative ''Scutellosaurus

''Scutellosaurus'' ( ) is a genus of thyreophoran ornithischian dinosaur that lived approximately 196 million years ago during the early part of the Jurassic Period in what is now Arizona, USA. It is classified in Thyreophora, the armoured di ...

''. However, the tibia was reinterpreted as that of an indeterminate neotheropod, the pentagonal object as a mere piece of basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the surface of a rocky planet or moon. More than 90 ...

resembling a fossil, and Grey's specimen as belonging to an ichthyosaur

Ichthyosaurs (Ancient Greek for "fish lizard" – and ) are large extinct marine reptiles. Ichthyosaurs belong to the order known as Ichthyosauria or Ichthyopterygia ('fish flippers' – a designation introduced by Sir Richard Owen in 1842, alt ...

. The scelidosaur femur and theropod tibia are the only known remains of dinosaurs from Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

, which has a poor Mesozoic fossil record entirely consisting of marine localities, and the scelidosaur specimen was the first ever reported from the island.

In 2000, David Martill

{{Short pages monitor