Sandford Fleming on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Sandford Fleming (January 7, 1827 – July 22, 1915) was a Scottish Canadian

As soon as he arrived in

As soon as he arrived in

In 1862 he placed before the government a plan for a transcontinental railway connecting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The first part, between Halifax and

In 1862 he placed before the government a plan for a transcontinental railway connecting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The first part, between Halifax and

sandfordfleming.ca: Sources

* *

Heritage Minutes: Sir Sandford Fleming

Biography from ''Sir Sandford Fleming College'' website

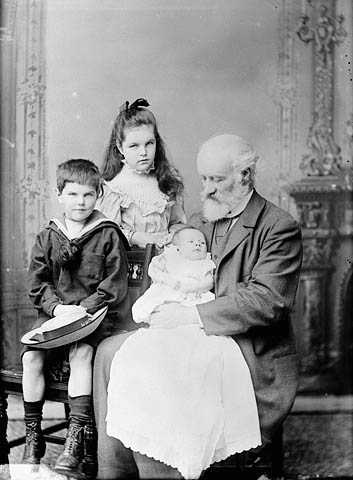

Sir Sandford Fleming circa 1885

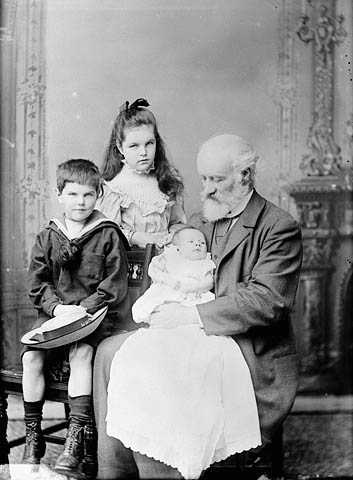

Sir Sandford Fleming in 1903

The Canadian Encyclopedia, Sir Sandford Fleming

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Fleming, Sandford 1827 births 1915 deaths Scottish inventors Canadian engineers 19th-century Canadian inventors Canadian Presbyterians Canadian surveyors Chancellors of Queen's University at Kingston Canadian Knights Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George People from Peterborough, Ontario Scottish emigrants to pre-Confederation Ontario Pre-Confederation Ontario people People from Kirkcaldy Persons of National Historic Significance (Canada) Immigrants to the Province of Canada Canadian Freemasons Burials at Beechwood Cemetery (Ottawa)

engineer

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who Invention, invent, design, analyze, build and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while considerin ...

and inventor

An invention is a unique or novel device, method, composition, idea or process. An invention may be an improvement upon a machine, product, or process for increasing efficiency or lowering cost. It may also be an entirely new concept. If an ...

. Born and raised in Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, he emigrated to colonial Canada at the age of 18. He promoted worldwide standard time zones

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, t ...

, a prime meridian

A prime meridian is an arbitrary meridian (a line of longitude) in a geographic coordinate system at which longitude is defined to be 0°. Together, a prime meridian and its anti-meridian (the 180th meridian in a 360°-system) form a great ...

, and use of the 24-hour clock

The modern 24-hour clock, popularly referred to in the United States as military time, is the convention of timekeeping in which the day runs from midnight to midnight and is divided into 24 hours. This is indicated by the hours (and minutes) pa ...

as key elements to communicating the accurate time, all of which influenced the creation of Coordinated Universal Time

Coordinated Universal Time or UTC is the primary time standard by which the world regulates clocks and time. It is within about one second of Solar time#Mean solar time, mean solar time (such as Universal Time, UT1) at 0° longitude (at the I ...

. He designed Canada's first postage stamp

A postage stamp is a small piece of paper issued by a post office, postal administration, or other authorized vendors to customers who pay postage (the cost involved in moving, insuring, or registering mail), who then affix the stamp to the f ...

, produced a great deal of work in the fields of land surveying

Surveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, art, and science of determining the terrestrial two-dimensional or three-dimensional positions of points and the distances and angles between them. A land surveying professional is ...

and map making

Cartography (; from grc, χάρτης , "papyrus, sheet of paper, map"; and , "write") is the study and practice of making and using maps. Combining science, aesthetics and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality (or an im ...

, engineered much of the Intercolonial Railway

The Intercolonial Railway of Canada , also referred to as the Intercolonial Railway (ICR), was a historic Canadian railway that operated from 1872 to 1918, when it became part of Canadian National Railways. As the railway was also completely ow ...

and the first several hundred kilometers of the Canadian Pacific Railway

The Canadian Pacific Railway (french: Chemin de fer Canadien Pacifique) , also known simply as CPR or Canadian Pacific and formerly as CP Rail (1968–1996), is a Canadian Class I railway incorporated in 1881. The railway is owned by Canad ...

, and was a founding member of the Royal Society of Canada

The Royal Society of Canada (RSC; french: Société royale du Canada, SRC), also known as the Academies of Arts, Humanities and Sciences of Canada (French: ''Académies des arts, des lettres et des sciences du Canada''), is the senior national, bil ...

and founder of the Canadian Institute

The Royal Canadian Institute for Science (RCIScience), known also as the Royal Canadian Institute, is a Canadian nonprofit organization dedicated to connecting the public with Canadian science.

History

The organization was formed in Toronto a ...

(a science organization in Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the anch ...

).

Early life

In 1827, Fleming was born in Kirkcaldy, Fife, Scotland to Andrew and Elizabeth Fleming. At the age of 14 he was apprenticed as a surveyor and in 1845, at the age of 18, he emigrated with his older brother David to colonialCanada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

. Their route took them through many cities of the Canadian colonies: Quebec City

Quebec City ( or ; french: Ville de Québec), officially Québec (), is the capital city of the Canadian province of Quebec. As of July 2021, the city had a population of 549,459, and the metropolitan area had a population of 839,311. It is t ...

, Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple- ...

, and Kingston, before settling in Peterborough

Peterborough () is a cathedral city in Cambridgeshire, east of England. It is the largest part of the City of Peterborough unitary authority district (which covers a larger area than Peterborough itself). It was part of Northamptonshire unti ...

with their cousins two years later in 1847. He qualified as a surveyor in Canada in 1849.

In 1849 he created the Royal Canadian Institute

The Royal Canadian Institute for Science (RCIScience), known also as the Royal Canadian Institute, is a Canadian nonprofit organization dedicated to connecting the public with Canadian science.

History

The organization was formed in Toronto as t ...

with several friends, which was formally incorporated on November 4, 1851. Although initially intended as a professional institute for surveyors and engineers it became a more general scientific society. In 1851 he designed the ''Threepenny Beaver'', the first Canadian postage stamp, for the Province of Canada

The Province of Canada (or the United Province of Canada or the United Canadas) was a British colony in North America from 1841 to 1867. Its formation reflected recommendations made by John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham, in the Report on the ...

(today's southern portions of Ontario and Quebec). Throughout this time he was fully employed as a surveyor

Surveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, art, and science of determining the terrestrial two-dimensional or three-dimensional positions of points and the distances and angles between them. A land surveying professional is ...

, mostly for the Grand Trunk Railway

The Grand Trunk Railway (; french: Grand Tronc) was a railway system that operated in the Canadian provinces of Quebec and Ontario and in the American states of Connecticut, Maine, Michigan, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont. The rail ...

. His work for them eventually gained him the position as ''Chief Engineer'' of the Northern Railway of Canada in 1855, where he advocated the construction of iron

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in ...

bridge

A bridge is a structure built to span a physical obstacle (such as a body of water, valley, road, or rail) without blocking the way underneath. It is constructed for the purpose of providing passage over the obstacle, which is usually someth ...

s instead of wood for safety reasons.

Fleming served in the 10th Battalion Volunteer Rifles of Canada (later known as the Royal Regiment of Canada) and was appointed to the rank of captain on January 1, 1862. He retired from the militia in 1865.

Family

As soon as he arrived in

As soon as he arrived in Peterborough, Ontario

Peterborough ( ) is a city on the Otonabee River in Ontario, Canada, about 125 kilometres (78 miles) northeast of Toronto. According to the 2021 Census, the population of the City of Peterborough was 83,651. The population of the Peterborough ...

in 1845, Fleming became friendly with the family of his future wife, the Halls, and was attracted to Ann Jane (Jeanie) Hall. However, it was not until a sleigh accident almost ten years later that the young people's love for each other was revealed. A year after this incident, in January 1855, Sandford married Ann Jane (Jean) Hall, daughter of Sheriff James Hall. They were to have nine children of whom two died young. The oldest son, Frank Andrew, accompanied Fleming in his great Western expedition of 1872. A family man, deeply attached to his wife and children, he also welcomed his father Andrew Greig Fleming, Andrew's wife and six of their other children who came to join him in Canada two years after his arrival. The Fleming and Hall families saw each other often.

After the death of his wife Jeanie in 1888, Fleming's niece Miss Elsie Smith, daughter of Alexander and Lily Smith, of Kingussie, Scotland, presided over his household at "Winterholme" 213 Chapel Street, Ottawa, Ontario.

Railway engineer

His time at the Northern Railway was marked by conflict with the architectFrederick William Cumberland

:''See also Cumberland (disambiguation), Cumberland (surname).''

Frederick William Cumberland (10 April 1821 – 5 August 1881) was a Canadian engineer, architect and politician. He represented the riding of Algoma in the 1st and 2nd Ontari ...

, with whom he started the Canadian Institute and who was general manager of the railway until 1855. Starting as assistant engineer in 1852, Fleming replaced Cumberland in 1855 but was in turn ousted by him in 1862. In 1863 he became the chief government surveyor of Nova Scotia charged with the construction of a line from Truro to Pictou

Pictou ( ; Canadian Gaelic: ''Baile Phiogto'') is a town in Pictou County, in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia. Located on the north shore of Pictou Harbour, the town is approximately 10 km (6 miles) north of the larger town of New Gla ...

. When he would not accept the tenders from contractors that he considered too high, he was asked to bid for the work himself and completed the line by 1867 with both savings for the government and profit for himself.

In 1862 he placed before the government a plan for a transcontinental railway connecting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The first part, between Halifax and

In 1862 he placed before the government a plan for a transcontinental railway connecting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The first part, between Halifax and Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirte ...

became an important part of the preconditions for New Brunswick

New Brunswick (french: Nouveau-Brunswick, , locally ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. It is the only province with both English and ...

and Nova Scotia to join the Canadian Federation

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by total ...

because of the uncertainties of travel through Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and nor ...

because of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

. In 1867 he was appointed engineer-in-chief of the Intercolonial Railway

The Intercolonial Railway of Canada , also referred to as the Intercolonial Railway (ICR), was a historic Canadian railway that operated from 1872 to 1918, when it became part of Canadian National Railways. As the railway was also completely ow ...

which became a federal project and he continued in this post until 1876. His insistence on building the bridges of iron and stone instead of wood was controversial at the time, but was soon vindicated by their resistance to fire.

By 1871, the strategy of a railway connection was being used to bring British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, for ...

into federation and Fleming was offered the chief engineer post on the Canadian Pacific Railway

The Canadian Pacific Railway (french: Chemin de fer Canadien Pacifique) , also known simply as CPR or Canadian Pacific and formerly as CP Rail (1968–1996), is a Canadian Class I railway incorporated in 1881. The railway is owned by Canad ...

. Although he hesitated because of the amount of work he had, in 1872 he set off with a small party to survey the route, particularly through the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico ...

, finding a practicable route through the Yellowhead Pass

The Yellowhead Pass is a mountain pass across the Continental Divide of the Americas in the Canadian Rockies. It is located on the provincial boundary between the Canadian provinces of Alberta and British Columbia, and lies within Jasper ...

. One of his companions, George Monro Grant

George Monro Grant (December 22, 1835 – May 10, 1902) was a Canadian church minister, writer, and political activist. He served as principal of Queen's College, Kingston, Ontario, for 25 years, from 1877 until 1902.

Early life, education

Gr ...

wrote an account of the trip, which became a best-seller. In June 1880, Fleming was dismissed by Sir Charles Tupper, with a $30,000 payoff. It was the hardest blow of Fleming's life, though he obtained a promise of monopoly, later revoked, on his next project, a trans-pacific telegraph cable. Nevertheless, in 1884 he became a director of the Canadian Pacific Railway and was present as the last spike was driven.

Inventor of worldwide standard time

Fleming is credited with "the initial effort that led to the adoption of the present time meridians". After missing a train while travelling inIreland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

in 1876 because a printed schedule listed p.m. instead of a.m., he proposed a single 24-hour clock for the entire world, conceptually located at the centre of the Earth and not linked to any surface meridian. He later called this time "Cosmopolitan time" and later still "Cosmic Time". In 1876 he wrote a memoir "Terrestrial Time" where he proposed 24 time zone

A time zone is an area which observes a uniform standard time for legal, commercial and social purposes. Time zones tend to follow the boundaries between countries and their subdivisions instead of strictly following longitude, because it ...

s, each an hour wide or 15 degrees of longitude. The zones were labelled A-Y, excluding J, and arbitrarily linked to the Greenwich meridian, which was designated G. All clocks within each zone would be set to the same time as the others, and between zones the alphabetic labels could be used as common notation. So for example cosmopolitan time G:45 would map to local time 14:45 in one zone and 15:45 in the next.

In two papers "Time reckoning" and "Longitude and Time Reckoning" presented at a meeting of the Canadian Institute in Toronto on February 8, 1879, Fleming revised his system to link with the anti-meridian of Greenwich

Greenwich ( , ,) is a town in south-east London, England, within the ceremonial county of Greater London. It is situated east-southeast of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime history and for giving its name to the Greenwich ...

(the 180th meridian

The 180th meridian or antimeridian is the meridian 180° both east and west of the prime meridian in a geographical coordinate system. The longitude at this line can be given as either east or west.

On Earth, these two meridians form a ...

). He suggested that a prime meridian

A prime meridian is an arbitrary meridian (a line of longitude) in a geographic coordinate system at which longitude is defined to be 0°. Together, a prime meridian and its anti-meridian (the 180th meridian in a 360°-system) form a great ...

be chosen and analyzed shipping numbers to suggest Greenwich as the meridian. Fleming's two papers were considered so important that in June 1879 the British Government forwarded copies to eighteen foreign countries and to various scientific bodies in England.

Fleming went on to advocate his system at several major international conferences including Geographical Congress at Venice in 1881, a meeting of the Geodetic Association at Rome in 1883, and the International Meridian Conference

The International Meridian Conference was a conference held in October 1884 in Washington, D.C., in the United States, to determine a prime meridian for international use. The conference was held at the request of U.S. President Chester A. ...

of 1884. The International Meridian Conference

The International Meridian Conference was a conference held in October 1884 in Washington, D.C., in the United States, to determine a prime meridian for international use. The conference was held at the request of U.S. President Chester A. ...

accepted the Greenwich Meridian

The historic prime meridian or Greenwich meridian is a geographical reference line that passes through the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, in London, England. The modern IERS Reference Meridian widely used today is based on the Greenwich m ...

and a universal day of 24 hours beginning at Greenwich midnight. However, the conference's resolution specified that the universal day "shall not interfere with the use of local or standard time where desirable". The conference also refused to accept his zones, stating that they were a local issue outside its purview.

In 1886 Fleming authored the pamphlet "Time-Reckoning for the 20th Century," published by the Smithsonian Institute.

By 1929, all major countries in the world had accepted time zones. In the present day, UTC offsets

The UTC offset is the difference in hours and minutes between Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) and local solar time, at a particular place. This difference is expressed with respect to UTC and is generally shown in the format , , or . So if the tim ...

divide the world into zones, and military time zones assign letters to the 24 hourly zones, similarly to Fleming's system.

Later life

When the railway privatization instituted by Tupper in 1880 forced him out of a job with government, he retired from the world of surveying, and took the position of Chancellor of Queen's University inKingston, Ontario

Kingston is a city in Ontario, Canada. It is located on the north-eastern end of Lake Ontario, at the beginning of the St. Lawrence River and at the mouth of the Cataraqui River (south end of the Rideau Canal). The city is midway between Tor ...

. He held this position for his last 35 years, where his former Minister George Monro Grant

George Monro Grant (December 22, 1835 – May 10, 1902) was a Canadian church minister, writer, and political activist. He served as principal of Queen's College, Kingston, Ontario, for 25 years, from 1877 until 1902.

Early life, education

Gr ...

was principal from 1877 until Grant's death in 1902. Not content to leave well enough alone, he tirelessly advocated the construction of a submarine telegraph cable connecting all of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

, the All Red Line

The All Red Line was a system of electrical telegraphs that linked much of the British Empire. It was inaugurated on 31 October 1902. The informal name derives from the common practice of colouring the territory of the British Empire red or ...

, which was completed in 1902.

Being a man of ideas, in 1882 he authored a book on the land policy of the HBC.

He also kept up with business ventures, becoming in 1882 one of the founding owners of the Nova Scotia Cotton Manufacturing Company in Halifax. He was a member of the North British Society. He also helped found the Western Canada Cement and Coal Company, which spawned the company town of Exshaw, Alberta. In 1910, this business was captured in a hostile take-over by stock manipulators acting under the name Canada Cement Company, which action was said by some to lead to an emotional depression that would contribute to Fleming's death a short time later.

In 1880 he served as the vice president of the Ottawa Horticultural Society

The Ottawa Horticultural Society was founded in 1892. It is a non-profit organization that exists to promote gardening and horticulture in Ottawa. This is done through a series of presentations, flower shows and workshops. The Society also car ...

. In 1888, he became the first president of the Rideau Curling Club

The Rideau Curling Club is a curling facility and organization located in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Founded in 1888, the Rideau Curling Club maintains a rivalry with the Ottawa Curling Club.

History

The original club began operation in November, ...

, after leaving the Ottawa Curling Club in protest of its temperance

Temperance may refer to:

Moderation

*Temperance movement, movement to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed

*Temperance (virtue), habitual moderation in the indulgence of a natural appetite or passion

Culture

* Temperance (group), Canadian dan ...

policy.

In early 1890s he turned his attention to electoral reform and the need for proportional representation

Proportional representation (PR) refers to a type of electoral system under which subgroups of an electorate are reflected proportionately in the elected body. The concept applies mainly to geographical (e.g. states, regions) and political divis ...

. He authored two books on the subject "An Appeal to the Canadian Institute on the Rectification of Parliament" (1892) and "Essays on the Rectification of Parliament" (1893), which included an essay by Australian reformer Catherine Helen Spence

Catherine Helen Spence (31 October 1825 – 3 April 1910) was a Scottish-born Australian author, teacher, journalist, politician, leading suffragist, and Georgist. Spence was also a minister of religion and social worker, and supporter of e ...

.

He became a strong advocate of a telecommunications cable from Canada to Australia, which he believed would become a vital communications link of the British Empire. The Pacific Cable was successfully laid in 1902. He authored the book "Canada and British Imperial Cables" in 1900.

His accomplishments were well known worldwide, and in 1897 he was knighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the G ...

by Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previ ...

. He was a freemason

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

, having joined St Andrew's Lodge No 1 ow No 16in York ow Toronto

In 1883, while surveying the route of the Canadian Pacific Railway

The Canadian Pacific Railway (french: Chemin de fer Canadien Pacifique) , also known simply as CPR or Canadian Pacific and formerly as CP Rail (1968–1996), is a Canadian Class I railway incorporated in 1881. The railway is owned by Canad ...

with George Monro Grant

George Monro Grant (December 22, 1835 – May 10, 1902) was a Canadian church minister, writer, and political activist. He served as principal of Queen's College, Kingston, Ontario, for 25 years, from 1877 until 1902.

Early life, education

Gr ...

, he met Major A. B. Rogers near the summit of Rogers Pass (British Columbia) and co-founded the first "Alpine Club of Canada". That early alpine club was short-lived, but in 1906 the modern Alpine Club of Canada

The Alpine Club of Canada (ACC) is an amateur athletic association with its national office in Canmore, Alberta that has been a focal point for Canadian mountaineering since its founding in 1906. The club was co-founded by Arthur Oliver Wheeler, ...

was founded in Winnipeg, and the by then Sir Sandford Fleming became the club's first Patron and Honorary President.

In his later years he retired to his house in Halifax, later deeding the house and the 95 acres (38 hectares) to the city, now known as Sir Sandford Fleming Park (Dingle Park). He also kept a residence in Ottawa

Ottawa (, ; Canadian French: ) is the capital city of Canada. It is located at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River in the southern portion of the province of Ontario. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the c ...

, and was buried there, in the Beechwood Cemetery

Beechwood Cemetery, located in the former city of Vanier in Ottawa, Ontario, is the National Cemetery of Canada. It is the final resting place for over 82,000 Canadians from all walks of life, such as important politicians like Governor Genera ...

.

Legacy

Fleming was designated a National Historic Person in 1950, on the advice of the national Historic Sites and Monuments Board. On January 7, 2017,Google

Google LLC () is an American Multinational corporation, multinational technology company focusing on Search Engine, search engine technology, online advertising, cloud computing, software, computer software, quantum computing, e-commerce, ar ...

celebrated Sandford Fleming's 190th birthday with a Google Doodle

A Google Doodle is a special, temporary alteration of the logo on Google's homepages intended to commemorate holidays, events, achievements, and notable historical figures. The first Google Doodle honored the 1998 edition of the long-running an ...

.

Things named after Fleming

Geographical features

*The town ofFleming, Saskatchewan

Fleming is a town in Saskatchewan, Canada. Per the 2021 census, with a population of 70 inhabitants, Fleming was the smallest official town in Saskatchewan by population. It is bordered primarily by the Rural Municipality of Moosomin No. 121, ...

(located on the Canadian Pacific Railway) was named in his honour in 1882.

* Mount Sir Sandford, which is the highest mountain in the Sir Sandford Range of the Selkirk Mountains

The Selkirk Mountains are a mountain range spanning the northern portion of the Idaho Panhandle, eastern Washington, and southeastern British Columbia which are part of a larger grouping of mountains, the Columbia Mountains. They begin at Mica ...

, and the 12th highest peak in British Columbia, is named after him.

*Sandford Island and Fleming Island in Barkley Sound, British Columbia were named after him.

* Sir Sandford Fleming Park, a Canadian urban park in Halifax, also known as “The Dingle” (as shown above under "Later life").

*Sandford Fleming Avenue, a street in Ottawa, home to the city's main post office.

Buildings and institutions

* Fleming Hall was built in his honour at Queen's in 1901, and rebuilt after a fire in 1933. It was the home of the university's Electrical Engineering department. * InPeterborough, Ontario

Peterborough ( ) is a city on the Otonabee River in Ontario, Canada, about 125 kilometres (78 miles) northeast of Toronto. According to the 2021 Census, the population of the City of Peterborough was 83,651. The population of the Peterborough ...

, Fleming College

Fleming College, also known as Sir Sandford Fleming College, is an Ontario College of Applied Arts and Technology located in Peterborough, Ontario, Canada. The college has an enrollment of more than 6,800 full-time and 10,000 part-time studen ...

, a Community College of Applied Arts and Technology bearing his name, was opened in 1967, with additional campuses in Lindsay/Kawartha Lakes, Haliburton, and Cobourg

Cobourg ( ) is a town in the Canadian province of Ontario, located in Southern Ontario east of Toronto and east of Oshawa. It is the largest town in and seat of Northumberland County. Its nearest neighbour is Port Hope, to the west. It ...

.

* The Sandford Fleming building of the University of Toronto Faculty of Applied Science and Engineering (Sandford Fleming building)

* Sir Sandford Fleming elementary school was built in Vancouver in 1913.

* Sir Sanford Fleming Academy, located in North York, Ontario was built in 1964 and was renamed to John Polanyi Collegiate Institute in 2011.

Postage stamps

Fleming has been honoured on two Canadian postage stamps: one from 1977 features his image and a railroad bridge of Fleming's design; another in 2002 reflects his promotion of the Pacific Cable. In addition, his design of the Three Penny Beaver, the first postage stamp for the Province of Canada (today's southern portions of Ontario and Quebec), has been used on seven stamp issues—in 1851, 1852, 1859, 1951, and 2001.See also

*Sandford Fleming Award

The Sandford Fleming Medal was instituted in 1982 by the Royal Canadian Institute. It consists of the Sandford Fleming Medal with Citation. It is awarded annually to a Canadian who has made outstanding contributions to the public understanding of s ...

Archives

There is a Sandford Fleming fonds atLibrary and Archives Canada

Library and Archives Canada (LAC; french: Bibliothèque et Archives Canada) is the federal institution, tasked with acquiring, preserving, and providing accessibility to the documentary heritage of Canada. The national archive and library is t ...

. Archival reference number is R7666.

References

* * *Further reading

* ''Time Lord: Sir Sandford Fleming and the Creation of Standard Time''.External links

*sandfordfleming.ca: Sources

* *

Heritage Minutes: Sir Sandford Fleming

Biography from ''Sir Sandford Fleming College'' website

Sir Sandford Fleming circa 1885

Sir Sandford Fleming in 1903

The Canadian Encyclopedia, Sir Sandford Fleming

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Fleming, Sandford 1827 births 1915 deaths Scottish inventors Canadian engineers 19th-century Canadian inventors Canadian Presbyterians Canadian surveyors Chancellors of Queen's University at Kingston Canadian Knights Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George People from Peterborough, Ontario Scottish emigrants to pre-Confederation Ontario Pre-Confederation Ontario people People from Kirkcaldy Persons of National Historic Significance (Canada) Immigrants to the Province of Canada Canadian Freemasons Burials at Beechwood Cemetery (Ottawa)