Samuel Richardson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Samuel Richardson (baptised 19 August 1689 – 4 July 1761) was an English writer and printer known for three

In 1733, Richardson was granted a contract with the

In 1733, Richardson was granted a contract with the

Work continued to improve, and Richardson printed the ''Daily Journal'' between 1736 and 1737, and the '' Daily Gazetteer'' in 1738. During his time printing the ''Daily Journal'', he was also printer to the "Society for the Encouragement of Learning", a group that tried to help authors become independent from publishers, but collapsed soon after. In December 1738, Richardson's printing business was successful enough to allow him to lease a house in Fulham. This house, which would be Richardson's residence from 1739 to 1754, was later named "The Grange" in 1836. In 1739, Richardson was asked by his friends Charles Rivington and John Osborn to write "a little volume of Letters, in a common style, on such subjects as might be of use to those country readers, who were unable to indite for themselves". While writing this volume, Richardson was inspired to write his first novel.

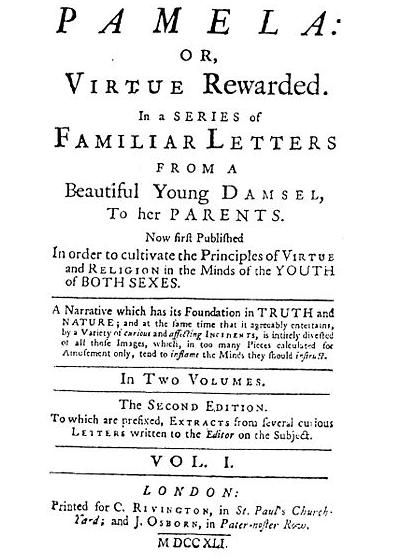

Richardson made the transition from master printer to novelist on 6 November 1740 with the publication of '' Pamela: or, Virtue Rewarded''. ''Pamela'' was sometimes regarded as "the

Work continued to improve, and Richardson printed the ''Daily Journal'' between 1736 and 1737, and the '' Daily Gazetteer'' in 1738. During his time printing the ''Daily Journal'', he was also printer to the "Society for the Encouragement of Learning", a group that tried to help authors become independent from publishers, but collapsed soon after. In December 1738, Richardson's printing business was successful enough to allow him to lease a house in Fulham. This house, which would be Richardson's residence from 1739 to 1754, was later named "The Grange" in 1836. In 1739, Richardson was asked by his friends Charles Rivington and John Osborn to write "a little volume of Letters, in a common style, on such subjects as might be of use to those country readers, who were unable to indite for themselves". While writing this volume, Richardson was inspired to write his first novel.

Richardson made the transition from master printer to novelist on 6 November 1740 with the publication of '' Pamela: or, Virtue Rewarded''. ''Pamela'' was sometimes regarded as "the  After Richardson started the work on 10 November 1739, his wife and her friends became so interested in the story that he finished it on 10 January 1740. Pamela Andrews, the heroine of ''Pamela'', represented "Richardson's insistence upon well-defined feminine roles" and was part of a common fear held during the 18th century that women were "too bold". In particular, her "zeal for housewifery" was included as a proper role of women in society. Although ''Pamela'' and the title heroine were popular and gave a proper model for how women should act, they inspired "a storm of anti-Pamelas" (like Henry Fielding's ''

After Richardson started the work on 10 November 1739, his wife and her friends became so interested in the story that he finished it on 10 January 1740. Pamela Andrews, the heroine of ''Pamela'', represented "Richardson's insistence upon well-defined feminine roles" and was part of a common fear held during the 18th century that women were "too bold". In particular, her "zeal for housewifery" was included as a proper role of women in society. Although ''Pamela'' and the title heroine were popular and gave a proper model for how women should act, they inspired "a storm of anti-Pamelas" (like Henry Fielding's ''

In July, Richardson sent Hill a complete "design" of the story, and asked Hill to try again, but Hill responded, "It is impossible, after the wonders you have shown in ''Pamela'', to question your infallible success in this new, natural, attempt" and that "you must give me leave to be astonished, when you tell me that you have finished it already". However, the novel was not complete to Richardson's satisfaction until October 1746. Between 1744 and 1746, Richardson tried to find readers who could help him shorten the work, but his readers wanted to keep the work in its entirety. A frustrated Richardson wrote to

In July, Richardson sent Hill a complete "design" of the story, and asked Hill to try again, but Hill responded, "It is impossible, after the wonders you have shown in ''Pamela'', to question your infallible success in this new, natural, attempt" and that "you must give me leave to be astonished, when you tell me that you have finished it already". However, the novel was not complete to Richardson's satisfaction until October 1746. Between 1744 and 1746, Richardson tried to find readers who could help him shorten the work, but his readers wanted to keep the work in its entirety. A frustrated Richardson wrote to  However, his condition did not stop him from continuing to release the final volumes ''Clarissa'' after November 1748. To Hill he wrote: "The Whole will make Seven; that is, one more to attend these two. Eight crouded into Seven, by a smaller Type. Ashamed as I am of the Prolixity, I thought I owed the Public Eight Vols. in Quantity for the Price of Seven". Richardson later made it up to the public with "deferred Restorations" of the fourth edition of the novel being printed in larger print with eight volumes and a preface that reads: "It is proper to observe with regard to the ''present Edition'' that it has been thought fit to restore many Passages, and several Letters which were omitted in the former merely for shortening-sake."

The response to the novel was positive, and the public began to describe the title heroine as "divine Clarissa". It was soon considered Richardson's "masterpiece", his greatest work, and was rapidly translated into French in part or in full, for instance by the abbé Antoine François Prévost, as well as into German. The Dutch translator of ''Clarissa'' was the distinguished Mennonite preacher, Johannes Stinstra (1708–1790), who as a champion of

However, his condition did not stop him from continuing to release the final volumes ''Clarissa'' after November 1748. To Hill he wrote: "The Whole will make Seven; that is, one more to attend these two. Eight crouded into Seven, by a smaller Type. Ashamed as I am of the Prolixity, I thought I owed the Public Eight Vols. in Quantity for the Price of Seven". Richardson later made it up to the public with "deferred Restorations" of the fourth edition of the novel being printed in larger print with eight volumes and a preface that reads: "It is proper to observe with regard to the ''present Edition'' that it has been thought fit to restore many Passages, and several Letters which were omitted in the former merely for shortening-sake."

The response to the novel was positive, and the public began to describe the title heroine as "divine Clarissa". It was soon considered Richardson's "masterpiece", his greatest work, and was rapidly translated into French in part or in full, for instance by the abbé Antoine François Prévost, as well as into German. The Dutch translator of ''Clarissa'' was the distinguished Mennonite preacher, Johannes Stinstra (1708–1790), who as a champion of  However, some did question the propriety of having Lovelace, the villain of the novel, act in such an immoral fashion. The novel avoids glorifying Lovelace, as Carol Flynn puts it,

But Richardson still felt the need to respond by writing a pamphlet called ''Answer to the Letter of a Very Reverend and Worthy Gentleman''. In the pamphlet, he defends his characterizations and explains that he took great pains to avoid any glorification of scandalous behaviour, unlike the authors of many other novels that rely on characters of such low quality.

In 1749, Richardson's female friends started asking him to create a male figure as virtuous as his heroines "Pamela" and "Clarissa" in order to "give the world his idea of a good man and fine gentleman combined". Although he did not at first agree, he eventually complied, starting work on a book in this vein in June 1750. Near the end of 1751, Richardson sent a draft of the novel ''

However, some did question the propriety of having Lovelace, the villain of the novel, act in such an immoral fashion. The novel avoids glorifying Lovelace, as Carol Flynn puts it,

But Richardson still felt the need to respond by writing a pamphlet called ''Answer to the Letter of a Very Reverend and Worthy Gentleman''. In the pamphlet, he defends his characterizations and explains that he took great pains to avoid any glorification of scandalous behaviour, unlike the authors of many other novels that rely on characters of such low quality.

In 1749, Richardson's female friends started asking him to create a male figure as virtuous as his heroines "Pamela" and "Clarissa" in order to "give the world his idea of a good man and fine gentleman combined". Although he did not at first agree, he eventually complied, starting work on a book in this vein in June 1750. Near the end of 1751, Richardson sent a draft of the novel ''

In his final years, Richardson received visits from

In his final years, Richardson received visits from

Samuel Richardson

at the

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Richardson, Samuel English printers English Anglicans People from Mackworth People from Parsons Green 1689 births 1761 deaths 18th-century English writers 18th-century English male writers 18th-century English novelists English male novelists

epistolary novel

An epistolary novel is a novel written as a series of letters. The term is often extended to cover novels that intersperse documents of other kinds with the letters, most commonly diary entries and newspaper clippings, and sometimes considered ...

s: ''Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded

''Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded'' is an epistolary novel first published in 1740 by English writer Samuel Richardson. Considered one of the first true English novels, it serves as Richardson's version of conduct literature about marriage. ''Pame ...

'' (1740), '' Clarissa: Or the History of a Young Lady'' (1748) and ''The History of Sir Charles Grandison

''The History of Sir Charles Grandison'', commonly called ''Sir Charles Grandison'', is an epistolary novel by English writer Samuel Richardson first published in February 1753. The book was a response to Henry Fielding's ''The History of Tom ...

'' (1753). He printed almost 500 works, including journals and magazines, working periodically with the London bookseller Andrew Millar

Andrew Millar (17058 June 1768) was a British publisher in the eighteenth century.

Biography

In 1725, as a twenty-year-old bookseller apprentice, he evaded Edinburgh city printing restrictions by going to Leith to print, which was considered b ...

. Richardson had been apprenticed to a printer, whose daughter he eventually married. He lost her along with their six children, but remarried and had six more children, of which four daughters reached adulthood, leaving no male heirs to continue the print shop. As it ran down, he wrote his first novel at the age of 51 and joined the admired writers of his day. Leading acquaintances included Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson (18 September 1709 – 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer. The ''Oxford ...

and Sarah Fielding

Sarah Fielding (8 November 1710 – 9 April 1768) was an English author and sister of the novelist Henry Fielding. She wrote '' The Governess, or The Little Female Academy'' (1749), thought to be the first novel in English aimed expressly at chi ...

, the physician and Behmenist George Cheyne, and the theologian and writer William Law

William Law (16869 April 1761) was a Church of England priest who lost his position at Emmanuel College, Cambridge when his conscience would not allow him to take the required oath of allegiance to the first Hanoverian monarch, King George I. P ...

, whose books he printed. At Law's request, Richardson printed some poems by John Byrom. In literature, he rivalled Henry Fielding

Henry Fielding (22 April 1707 – 8 October 1754) was an English novelist, irony writer, and dramatist known for earthy humour and satire. His comic novel ''Tom Jones'' is still widely appreciated. He and Samuel Richardson are seen as founders ...

; the two responded to each other's literary styles.

Biography

Richardson, one of nine children, was probably born in 1689 in Mackworth, Derbyshire, to Samuel and Elizabeth Richardson. It is unsure where in Derbyshire he was born because Richardson always concealed the location, but it has recently been discovered that Richardson probably lived in poverty as a child. The older Richardson was, according to the younger: His mother, according to Richardson, "was also a good woman, of a family not ungenteel; but whose father and mother died in her infancy, within half-an-hour of each other, in the London pestilence of 1665". The trade his father pursued was that of a joiner (a type of carpenter, but Richardson explains that it was "then more distinct from that of a carpenter than now it is with us"). In describing his father's occupation, Richardson stated that "he was a good draughtsman and understood architecture", and it was suggested by Samuel Richardson's son-in-law that the senior Richardson was a cabinetmaker and an exporter of mahogany while working at Aldersgate-street. The abilities and position of his father brought him to the attention ofJames Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth

James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth, 1st Duke of Buccleuch, KG, PC (9 April 1649 – 15 July 1685) was a Dutch-born English nobleman and military officer. Originally called James Crofts or James Fitzroy, he was born in Rotterdam in the Netherlan ...

. However, as Richardson claims, this was to Richardson senior's "great detriment" because of the failure of the Monmouth Rebellion

The Monmouth Rebellion, also known as the Pitchfork Rebellion, the Revolt of the West or the West Country rebellion, was an attempt to depose James II, who in February 1685 succeeded his brother Charles II as king of England, Scotland and Ir ...

, which ended in the death of Scott in 1685. After Scott's death, the elder Richardson was forced to abandon his business in London and live a modest life in Derbyshire.

Early life

The Richardsons were not exiled forever from London; they eventually returned, and the young Richardson was educated atChrist's Hospital

Christ's Hospital is a public school (English independent boarding school for pupils aged 11–18) with a royal charter located to the south of Horsham in West Sussex. The school was founded in 1552 and received its first royal charter in 1553. ...

grammar school. The extent that he was educated at the school is uncertain, and Leigh Hunt

James Henry Leigh Hunt (19 October 178428 August 1859), best known as Leigh Hunt, was an English critic, essayist and poet.

Hunt co-founded '' The Examiner'', a leading intellectual journal expounding radical principles. He was the centre ...

wrote years later:

However, this conflicts with Richardson's nephew's account that "'it is certain that ichardsonwas never sent to a more respectable seminary' than 'a private grammar school' located in Derbyshire".

Little is known of Richardson's early years beyond the few things that Richardson was willing to share. Although he was not forthcoming with specific events and incidents, he did talk about the origins of his writing ability; Richardson would tell stories to his friends and spent his youth constantly writing letters. One such letter, written when Richardson was almost 11, was directed to a woman in her 50s who was in the habit of constantly criticizing others. "Assuming the style and address of a person in years", Richardson cautioned her about her actions. However, his handwriting was used to determine that it was his work, and the woman complained to his mother. The result was, as he explains, that "my mother chid me for the freedom taken by such a boy with a woman of her years" but also "commended my principles, though she censured the liberty taken".

After his writing ability was known, he began to help others in the community write letters. In particular, Richardson, at the age of 13, helped many of the girls that he associated with to write responses to various love letters they received. As Richardson claims, "I have been directed to chide, and even repulse, when an offence was either taken or given, at the very time that the heart of the chider or repulser was open before me, overflowing with esteem and affect". Although this helped his writing ability, he in 1753 advised the Dutch minister Stinstra not to draw large conclusions from these early actions:

He continued to explain that he did not fully understand females until writing ''Clarissa'', and these letters were only a beginning.

Early career

The elder Richardson originally wanted his son to become a clergyman, but he was not able to afford the education that the younger Richardson would require, so he let his son pick his own profession. He selected the profession of printing because he hoped to "gratify a thirst for reading, which, in after years, he disclaimed". At the age of 17, in 1706, Richardson was bound in seven-year apprenticeship under John Wilde as a printer. Wilde's printing shop was in Golden Lion Court on Aldersgate Street, and Wilde had a reputation as "a master who grudged every hour... that tended not to his profit".. While working for Wilde, he met a rich gentleman who took an interest in Richardson's writing abilities and the two began to correspond with each other. When the gentleman died a few years later, Richardson lost a potential patron, which delayed his ability to pursue his own writing career. He decided to devote himself completely to his apprenticeship, and he worked his way up to a position as a compositor and a corrector of the shop's printing press. In 1713, Richardson left Wilde to become "Overseer and Corrector of a Printing-Office". This meant that Richardson ran his own shop, but the location of that shop is unknown. It is possible that the shop was located in Staining Lane or may have been jointly run with John Leake in Jewin Street. In 1719, Richardson was able to take his freedom from being an apprentice and was soon able to afford to set up his own printing shop, which he did after he moved near the Salisbury Court district close to Fleet Street. Although he claimed to business associates that he was working out of the well-known Salisbury Court, his printing shop was more accurately located on the corner of Blue Ball Court and Dorset Street in a house that later became Bell's Building. On 23 November 1721, Richardson married Martha Wilde, the daughter of his former employer. The match was "prompted mainly by prudential considerations", although Richardson would claim later that there was a strong love-affair between Martha and him. He soon brought her to live with him in the printing shop that served also as his home. A key moment in Richardson's career came on 6 August 1722 when he took on his first apprentices: Thomas Gover, George Mitchell, and Joseph Chrichley. He would later take on William Price (2 May 1727), Samuel Jolley (5 September 1727), Bethell Wellington (2 September 1729), and Halhed Garland (5 May 1730). One of Richardson's first major printing contracts came in June 1723 when he began to print the bi-weekly ''The True Briton'' for Philip Wharton, 1st Duke of Wharton. This was a Jacobite political paper which attacked the government and was soon censored for printing "common libels". However, Richardson's name was not on the publication, and he was able to escape any of the negative fallout, although it is possible that Richardson participated in the papers as far as actually writing one himself. The only lasting effect from the paper would be the incorporation of Wharton's libertine characteristics in the character of Lovelace in Richardson's ''Clarissa'', although Wharton would be only one of many models of libertine behaviour that Richardson would find in his life. In 1724, Richardson befriended Thomas Gent, Henry Woodfall, and Arthur Onslow, the latter of those would become the Speaker of the House of Commons. Over their ten years of marriage, the Richardsons had five sons and one daughter – three of the boys were successively named Samuel after their father, but all three died young. Soon after the death of William, their fourth child, Martha died on 25 January 1731. Their youngest son, Samuel, was to live past his mother for a year longer, but succumbed to illness in 1732. After his final son died, Richardson attempted to move on with his life. He married Elizabeth Leake, whose father was a printer, and the two moved into another house on Blue Ball Court. However, Elizabeth and his daughter were not the only ones living with him because Richardson allowed five of his apprentices to lodge in his home. Elizabeth had six children (five daughters and one son) with Richardson; four of their daughters, Mary, Martha, Anne, and Sarah, reached adulthood and survived their father. Their son, another Samuel, was born in 1739 and died in 1740. In 1733, Richardson was granted a contract with the

In 1733, Richardson was granted a contract with the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

, with help from Onslow, to print the ''Journals of the House''. The 26 volumes of the work soon improved his business. Later in 1733, he wrote ''The Apprentice's Vade Mecum'', urging young men like himself to be diligent and self-denying.. The work was intended to "create the perfect apprentice". Written in response to the "epidemick Evils of the present Age", the text is best known for its condemnation of popular forms of entertainment including theatres, taverns and gambling. The manual targets the apprentice as the focal point for the moral improvement of society, not because he is most susceptible to vice, but because, Richardson suggests, he is more responsive to moral improvement than his social betters. During this time, Richardson took on five more apprentices: Thomas Verren (1 August 1732), Richard Smith (6 February 1733), Matthew Stimson (7 August 1733), Bethell Wellington (7 May 1734), and Daniel Green (1 October 1734). His total staff during the 1730s numbered seven, as his first three apprentices were free by 1728, and two of his apprentices, Verren and Smith, died soon into their apprenticeship. The loss of Verren was particularly devastating to Richardson because Verren was his nephew and his hope for a male heir that would take over the press.

First novel

Work continued to improve, and Richardson printed the ''Daily Journal'' between 1736 and 1737, and the '' Daily Gazetteer'' in 1738. During his time printing the ''Daily Journal'', he was also printer to the "Society for the Encouragement of Learning", a group that tried to help authors become independent from publishers, but collapsed soon after. In December 1738, Richardson's printing business was successful enough to allow him to lease a house in Fulham. This house, which would be Richardson's residence from 1739 to 1754, was later named "The Grange" in 1836. In 1739, Richardson was asked by his friends Charles Rivington and John Osborn to write "a little volume of Letters, in a common style, on such subjects as might be of use to those country readers, who were unable to indite for themselves". While writing this volume, Richardson was inspired to write his first novel.

Richardson made the transition from master printer to novelist on 6 November 1740 with the publication of '' Pamela: or, Virtue Rewarded''. ''Pamela'' was sometimes regarded as "the

Work continued to improve, and Richardson printed the ''Daily Journal'' between 1736 and 1737, and the '' Daily Gazetteer'' in 1738. During his time printing the ''Daily Journal'', he was also printer to the "Society for the Encouragement of Learning", a group that tried to help authors become independent from publishers, but collapsed soon after. In December 1738, Richardson's printing business was successful enough to allow him to lease a house in Fulham. This house, which would be Richardson's residence from 1739 to 1754, was later named "The Grange" in 1836. In 1739, Richardson was asked by his friends Charles Rivington and John Osborn to write "a little volume of Letters, in a common style, on such subjects as might be of use to those country readers, who were unable to indite for themselves". While writing this volume, Richardson was inspired to write his first novel.

Richardson made the transition from master printer to novelist on 6 November 1740 with the publication of '' Pamela: or, Virtue Rewarded''. ''Pamela'' was sometimes regarded as "the first novel in English

A number of works of literature have been claimed to be the first novel in English.

List of candidates

* Thomas Malory, ''Le Morte d'Arthur'' (a.k.a. ''Le Morte Darthur''), (written c. 1470, published 1485)

* William Baldwin, ''Beware the Cat'', ( ...

" or the first modern novel

A novel is a relatively long work of narrative fiction, typically written in prose and published as a book. The present English word for a long work of prose fiction derives from the for "new", "news", or "short story of something new", its ...

. Richardson explained the origins of the work:

After Richardson started the work on 10 November 1739, his wife and her friends became so interested in the story that he finished it on 10 January 1740. Pamela Andrews, the heroine of ''Pamela'', represented "Richardson's insistence upon well-defined feminine roles" and was part of a common fear held during the 18th century that women were "too bold". In particular, her "zeal for housewifery" was included as a proper role of women in society. Although ''Pamela'' and the title heroine were popular and gave a proper model for how women should act, they inspired "a storm of anti-Pamelas" (like Henry Fielding's ''

After Richardson started the work on 10 November 1739, his wife and her friends became so interested in the story that he finished it on 10 January 1740. Pamela Andrews, the heroine of ''Pamela'', represented "Richardson's insistence upon well-defined feminine roles" and was part of a common fear held during the 18th century that women were "too bold". In particular, her "zeal for housewifery" was included as a proper role of women in society. Although ''Pamela'' and the title heroine were popular and gave a proper model for how women should act, they inspired "a storm of anti-Pamelas" (like Henry Fielding's ''Shamela

''An Apology for the Life of Mrs. Shamela Andrews'', or simply ''Shamela'', as it is more commonly known, is a satirical burlesque novella by English writer Henry Fielding. It was first published in April 1741 under the name of ''Mr. Conny Key ...

'' and ''Joseph Andrews

''The History of the Adventures of Joseph Andrews and of his Friend Mr. Abraham Adams'', was the first full-length novel by the English author Henry Fielding to be published and among the early novels in the English language. Appearing in 1742 ...

'' and Eliza Haywood

Eliza Haywood (c. 1693 – 25 February 1756), born Elizabeth Fowler, was an English writer, actress and publisher. An increase in interest and recognition of Haywood's literary works began in the 1980s. Described as "prolific even by the standar ...

's '' The Anti-Pamela'') because the character "perfectly played her part".

Later that year, Richardson printed Rivington and Osborn's book which inspired ''Pamela'' under the title of ''Letters written to and for particular Friends, on the most important Occasions. Directing not only the requisite Style and Forms to be observed in writing'' Familiar Letters; ''but how to think and act justly and prudently, in the common Concerns of Human Life''. The book contained many anecdotes and lessons on how to live, but Richardson did not care for the work and it was never expanded even though it went into six editions during his life. He went so far as to tell a friend, "This volume of letters is not worthy of your perusal" because they were "intended for the lower classes of people".

Multiple sequels to Pamela were written by other writers, such as ''Pamela’s Conduct in High Life'', which was written by John Kelly and published by Ward and Chandler in September 1741. Published that same year were two anonymous sequels: ''Pamela in High Life'' and ''The Life of Pamela'', the latter being a third-person retelling of both Richardson's original novel and Kelly's continuation. These unofficial sequels capitalized off the character’s popularity and readers desire to learn what happened to Pamela and Mr. B after the conclusion of Richardson’s novel.Sabor, Peter. "Samuel Richardson." ''The Cambridge Companion to English Novelists, Cambridge.'' Edited by Adrian Poole. Cambridge University Press, 2009''. ProQuest.'' This compelled Richardson to write a sequel to the novel, '' Pamela in her Exalted Condition'', in December 1741. The novel had a poorer reception than the first, as Peter Sabor writes, “the continuation is a far blander affair than the original work,” focusing on Pamela’s gentility and married life. The public's interest in the characters was waning, and this was only furthered by Richardson's focusing on Pamela discussing morality, literature, and philosophy.

Later career

After the failures of the ''Pamela'' sequels, Richardson began to compose a new novel. It was not until early 1744 that the content of the plot was known, and this happened when he sent Aaron Hill two chapters to read. In particular, Richardson asked Hill if he could help shorten the chapters because Richardson was worried about the length of the novel. Hill refused, saying, In July, Richardson sent Hill a complete "design" of the story, and asked Hill to try again, but Hill responded, "It is impossible, after the wonders you have shown in ''Pamela'', to question your infallible success in this new, natural, attempt" and that "you must give me leave to be astonished, when you tell me that you have finished it already". However, the novel was not complete to Richardson's satisfaction until October 1746. Between 1744 and 1746, Richardson tried to find readers who could help him shorten the work, but his readers wanted to keep the work in its entirety. A frustrated Richardson wrote to

In July, Richardson sent Hill a complete "design" of the story, and asked Hill to try again, but Hill responded, "It is impossible, after the wonders you have shown in ''Pamela'', to question your infallible success in this new, natural, attempt" and that "you must give me leave to be astonished, when you tell me that you have finished it already". However, the novel was not complete to Richardson's satisfaction until October 1746. Between 1744 and 1746, Richardson tried to find readers who could help him shorten the work, but his readers wanted to keep the work in its entirety. A frustrated Richardson wrote to Edward Young

Edward Young (c. 3 July 1683 – 5 April 1765) was an English poet, best remembered for ''Night-Thoughts'', a series of philosophical writings in blank verse, reflecting his state of mind following several bereavements. It was one of the mo ...

in November 1747:

Richardson did not devote all of his time just to working on his new novel, but was busy printing various works for other authors that he knew. In 1742, he printed the third edition of Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe (; born Daniel Foe; – 24 April 1731) was an English writer, trader, journalist, pamphleteer and spy. He is most famous for his novel '' Robinson Crusoe'', published in 1719, which is claimed to be second only to the Bible in its ...

's ''Tour through Great Britain''. He filled his few further years with smaller works for his friends until 1748, when Richardson started helping Sarah Fielding

Sarah Fielding (8 November 1710 – 9 April 1768) was an English author and sister of the novelist Henry Fielding. She wrote '' The Governess, or The Little Female Academy'' (1749), thought to be the first novel in English aimed expressly at chi ...

and her friend Jane Collier to write novels.. By 1748, Richardson was so impressed with Collier that he accepted her as the governess to his daughters.. In 1753, she wrote '' An Essay on the Art of Ingeniously Tormenting'' with the help of Sarah Fielding and possibly James Harris or Richardson, and it was Richardson who printed the work. But Collier was not the only author to be helped by Richardson, as he printed an edition of Young's ''Night Thoughts'' in 1749.

By 1748 his novel ''Clarissa'' was published in full: two volumes appeared in November 1747, two in April 1748, and three in December 1748. Unlike the novel, the author was not faring well at this time. By August 1748, Richardson was in poor health. He had a sparse diet that consisted mostly of vegetables and drinking vast amounts of water, and was not robust enough to prevent the effects of being bled upon the advice of various doctors throughout his life. He was known for "vague 'startings' and 'paroxysms'", along with experiencing tremors. Richardson once wrote to a friend that "my nervous disorders will permit me to write with more impunity than to read" and that writing allowed him a "freedom he could find nowhere else".

However, his condition did not stop him from continuing to release the final volumes ''Clarissa'' after November 1748. To Hill he wrote: "The Whole will make Seven; that is, one more to attend these two. Eight crouded into Seven, by a smaller Type. Ashamed as I am of the Prolixity, I thought I owed the Public Eight Vols. in Quantity for the Price of Seven". Richardson later made it up to the public with "deferred Restorations" of the fourth edition of the novel being printed in larger print with eight volumes and a preface that reads: "It is proper to observe with regard to the ''present Edition'' that it has been thought fit to restore many Passages, and several Letters which were omitted in the former merely for shortening-sake."

The response to the novel was positive, and the public began to describe the title heroine as "divine Clarissa". It was soon considered Richardson's "masterpiece", his greatest work, and was rapidly translated into French in part or in full, for instance by the abbé Antoine François Prévost, as well as into German. The Dutch translator of ''Clarissa'' was the distinguished Mennonite preacher, Johannes Stinstra (1708–1790), who as a champion of

However, his condition did not stop him from continuing to release the final volumes ''Clarissa'' after November 1748. To Hill he wrote: "The Whole will make Seven; that is, one more to attend these two. Eight crouded into Seven, by a smaller Type. Ashamed as I am of the Prolixity, I thought I owed the Public Eight Vols. in Quantity for the Price of Seven". Richardson later made it up to the public with "deferred Restorations" of the fourth edition of the novel being printed in larger print with eight volumes and a preface that reads: "It is proper to observe with regard to the ''present Edition'' that it has been thought fit to restore many Passages, and several Letters which were omitted in the former merely for shortening-sake."

The response to the novel was positive, and the public began to describe the title heroine as "divine Clarissa". It was soon considered Richardson's "masterpiece", his greatest work, and was rapidly translated into French in part or in full, for instance by the abbé Antoine François Prévost, as well as into German. The Dutch translator of ''Clarissa'' was the distinguished Mennonite preacher, Johannes Stinstra (1708–1790), who as a champion of Socinianism

Socinianism () is a nontrinitarian belief system deemed heretical by the Catholic Church and other Christian traditions. Named after the Italian theologians Lelio Sozzini (Latin: Laelius Socinus) and Fausto Sozzini (Latin: Faustus Socinus), un ...

had been suspended from the ministry in 1742. This gave him sufficient leisure to translate ''Clarissa'', which was published in eight volumes between 1752–1755. However, Stinstra later wrote in a letter to Richardson of 24 December 1753 that the translation had been "a burden too heavy for isshoulders". In England there was particular emphasis on Richardson's "natural creativity" and his ability to incorporate daily life experience into the novel. However, the final three volumes were delayed, and many of the readers began to "anticipate" the concluding story and some demanded that Richardson write a happy ending. One such advocate of the happy ending was Henry Fielding, who had previously written ''Joseph Andrews'' to mock Richardson's ''Pamela''. Although Fielding was originally opposed to Richardson, Fielding supported the original volumes of ''Clarissa'' and thought a happy ending would be "poetical justice". Those who disagreed included the Sussex

Sussex (), from the Old English (), is a historic county in South East England that was formerly an independent medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom. It is bounded to the west by Hampshire, north by Surrey, northeast by Kent, south by the Englis ...

diarist Thomas Turner, writing in about July 1754: "''Clarissa Harlow'' ic I look upon as a very well-wrote thing, tho' it must be allowed it is too prolix. The author keeps up the character of every person in all places; and as to the maner icof its ending, I like it better than if it had terminated in more happy consequences."

Others wanted Lovelace to be reformed and for him and Clarissa to marry, but Richardson would not allow a "reformed rake" to be her husband, and was unwilling to change the ending. In a postscript to ''Clarissa'', Richardson wrote:

Although few were bothered by the epistolary style, Richardson feels obliged to continue his postscript with a defence of the form based on the success of it in ''Pamela''.

However, some did question the propriety of having Lovelace, the villain of the novel, act in such an immoral fashion. The novel avoids glorifying Lovelace, as Carol Flynn puts it,

But Richardson still felt the need to respond by writing a pamphlet called ''Answer to the Letter of a Very Reverend and Worthy Gentleman''. In the pamphlet, he defends his characterizations and explains that he took great pains to avoid any glorification of scandalous behaviour, unlike the authors of many other novels that rely on characters of such low quality.

In 1749, Richardson's female friends started asking him to create a male figure as virtuous as his heroines "Pamela" and "Clarissa" in order to "give the world his idea of a good man and fine gentleman combined". Although he did not at first agree, he eventually complied, starting work on a book in this vein in June 1750. Near the end of 1751, Richardson sent a draft of the novel ''

However, some did question the propriety of having Lovelace, the villain of the novel, act in such an immoral fashion. The novel avoids glorifying Lovelace, as Carol Flynn puts it,

But Richardson still felt the need to respond by writing a pamphlet called ''Answer to the Letter of a Very Reverend and Worthy Gentleman''. In the pamphlet, he defends his characterizations and explains that he took great pains to avoid any glorification of scandalous behaviour, unlike the authors of many other novels that rely on characters of such low quality.

In 1749, Richardson's female friends started asking him to create a male figure as virtuous as his heroines "Pamela" and "Clarissa" in order to "give the world his idea of a good man and fine gentleman combined". Although he did not at first agree, he eventually complied, starting work on a book in this vein in June 1750. Near the end of 1751, Richardson sent a draft of the novel ''The History of Sir Charles Grandison

''The History of Sir Charles Grandison'', commonly called ''Sir Charles Grandison'', is an epistolary novel by English writer Samuel Richardson first published in February 1753. The book was a response to Henry Fielding's ''The History of Tom ...

'' to Mrs. Donnellan, and the novel was being finalized in the middle of 1752. When the novel was being printed in 1753, Richardson discovered that Irish printers were trying to pirate the work. He immediately fired those he suspected of giving the printers advanced copies of ''Grandison'' and relied on multiple London printing firms to help him produce an authentic edition before the pirated version was sold. The first four volumes were published on 13 November 1753, and in December the next two would follow. The remaining volume was published in March to complete a seven-volume series while a six-volume set was simultaneously published, and these met success. In ''Grandison'', Richardson was unwilling to risk having a negative response to any "rakish" characteristics that Lovelace embodied and denigrated the immoral characters "to show those mischievous young admirers of Lovelace once and for all that the rake should be avoided".

Death

In his final years, Richardson received visits from

In his final years, Richardson received visits from Archbishop Secker

Thomas Secker (21 September 16933 August 1768) was the Archbishop of Canterbury in the Church of England.

Early life and studies

Secker was born in Sibthorpe, Nottinghamshire. In 1699, he went to Richard Brown's free school in Chesterfield, ...

, other important political figures, and many London writers. By that time, he enjoyed a high social position and was Master of the Stationers' Company. In early November 1754, Richardson and his family moved from the Grange to a home at Parsons Green

Parsons Green is a mainly residential district in the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham. The Green itself, which is roughly triangular, is bounded on two of its three sides by the New King's Road section of the King's Road, A308 road ...

, now in west London. During this time Richardson received a letter from Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson (18 September 1709 – 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer. The ''Oxford ...

asking for money to pay a debt that Johnson was unable to afford. On 16 March 1756, Richardson responded with more than enough money and their friendship was certain by this time.

At the same time as he was associating with important figures of the day, Richardson's career as a novelist drew to a close. ''Grandison'' was his final novel, and he stopped writing fiction afterwards. It was ''Grandison'' that set the tone for Richardson's followers after his death. However, he was continually prompted by various friends and admirers to continue to write along with suggested topics. Richardson did not like any of the topics, and chose to spend all of his time composing letters to his friends and associates. The only major work that Richardson would write would be ''A Collection of the Moral and Instruction Sentiments, Maxims, Cautions, and Reflexions, contained in the Histories of Pamela, Clarissa, and Sir Charles Grandison''. Although it is possible that this work was inspired by Johnson asking for an "index rerum" for Richardson's novels, the ''Collection'' contains more of a focus on "moral and instructive" lessons than the index that Johnson sought.

After June 1758, Richardson began to suffer from insomnia, and in June 1761, he was afflicted with apoplexy

Apoplexy () is rupture of an internal organ and the accompanying symptoms. The term formerly referred to what is now called a stroke. Nowadays, health care professionals do not use the term, but instead specify the anatomic location of the bleedi ...

. This moment was described by his friend, Miss Talbot, on 2 July 1761:

Two days later, aged 71, on 4 July 1761, Richardson died at Parsons Green and was buried at St. Bride's Church in Fleet Street

Fleet Street is a major street mostly in the City of London. It runs west to east from Temple Bar at the boundary with the City of Westminster to Ludgate Circus at the site of the London Wall and the River Fleet from which the street was n ...

near his first wife Martha.

During Richardson's life, his printing press produced about 10,000 pieces, including novels, historical texts, Acts of Parliament, and newspapers, making his print house one of the most productive and diverse in the 18th century. He wanted to keep the press in his family, but after the death of his four sons and a nephew, his printing press would be left in his will to his only surviving male heir, a second nephew. This happened to be a nephew whom Richardson did not trust, doubting his abilities as a printer. Richardson's fears proved well-founded, for after his death the press stopped producing quality works and eventually stopped printing altogether. Richardson owned copyrights to most of his works, and these were sold after his death, in twenty-fourth share issues, with shares in ''Clarissa'' bringing in 25 pounds each and those for ''Grandison'' bringing in 20 pounds each. Shares in ''Pamela'', sold in sixteenths, went for 18 pounds each.

Epistolary novel

Richardson was a skilled letter writer and his talent traces back to his childhood. Throughout his whole life, he would constantly write to his various associates. Richardson had a "faith" in the act of letter writing, and believed that letters could be used to accurately portray character traits. He quickly adopted theepistolary novel

An epistolary novel is a novel written as a series of letters. The term is often extended to cover novels that intersperse documents of other kinds with the letters, most commonly diary entries and newspaper clippings, and sometimes considered ...

form, which granted him "the tools, the space, and the freedom to develop distinctly different characters speaking directly to the reader". The epistolary form gave Richardson, as well as others, the means to impact his audience more effectively as readers were able to get a more intimate insight into a novel’s characters. This allowed a stronger sense of engagement with the text to develop. Richardson structured his epistolary work to offer multiple perspectives so readers could interpret the text in varied ways. However, Richardson “hoped he would eventually convince his audience to read in the ways that he chose—ways that he hoped would lead to moral regeneration.”Whyman, Susan E. "Letter Writing and the Rise of the Novel: The Epistolary Literacy of Jane Johnson and Samuel Richardson." ''The Huntington Library Quarterly'', vol. 70, no. 4, 2007, pp. 577-VII''. ProQuest.'' These epistolary novels were a “moral project” as well as a literary one; Susan Whyman writes that Richardson’s “goal was not only to reform reading practices but to reform lives as well.”

In his first novel, ''Pamela'', he explored the various complexities of the title character's life, and the letters allow the reader to witness her develop and progress over time. The novel was an experiment, but it allowed Richardson to create a complex heroine through a series of her letters. When Richardson wrote ''Clarissa'', he had more experience in the form and expanded the letter writing to four different correspondents, which created a complex system of characters encouraging each other to grow and develop over time. However, the villain of the story, Lovelace, is also involved in the letter writing, and this leads to tragedy. Leo Braudy described the benefits of the epistolary form of ''Clarissa'' as, "Language can work: letters can be ways to communicate and justify".. By the time Richardson writes ''Grandison'', he transforms the letter writing from telling of personal insights and explaining feelings into a means for people to communicate their thoughts on the actions of others and for the public to celebrate virtue. The letters are no longer written for a few people, but are passed along in order for all to see. The characters of ''Pamela'', ''Clarissa'', and ''Grandison'' are revealed in a personal way, with the first two using the epistolary form for "dramatic" purposes, and the last for "celebratory" purposes.

Works

Novels

*''Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded

''Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded'' is an epistolary novel first published in 1740 by English writer Samuel Richardson. Considered one of the first true English novels, it serves as Richardson's version of conduct literature about marriage. ''Pame ...

'' (1740–1761)

*'' Pamela in her Exalted Condition'' (1741–1761) – the sequel to Pamela, usually published together in 4 Volumes – revised through 14 editions

*'' Clarissa, or, the History of a Young Lady'' (1747–61) – revised through 4 editions

**''Letters and Passages Restored to Clarissa

''Clarissa; or, The History of a Young Lady: Comprehending the Most Important Concerns of Private Life. And Particularly Shewing, the Distresses that May Attend the Misconduct Both of Parents and Children, In Relation to Marriage'' is an epist ...

'' (1751)

*''The History of Sir Charles Grandison

''The History of Sir Charles Grandison'', commonly called ''Sir Charles Grandison'', is an epistolary novel by English writer Samuel Richardson first published in February 1753. The book was a response to Henry Fielding's ''The History of Tom ...

'' (1753–1761) – restored and corrected through 4 editions

*''The History of Mrs. Beaumont – A Fragment'' – unfinished

Supplements

*''A Reply to the Criticism ofClarissa

''Clarissa; or, The History of a Young Lady: Comprehending the Most Important Concerns of Private Life. And Particularly Shewing, the Distresses that May Attend the Misconduct Both of Parents and Children, In Relation to Marriage'' is an epist ...

'' (1749)

*''Meditations on Clarissa

''Clarissa; or, The History of a Young Lady: Comprehending the Most Important Concerns of Private Life. And Particularly Shewing, the Distresses that May Attend the Misconduct Both of Parents and Children, In Relation to Marriage'' is an epist ...

'' (1751)

*''The Case of Samuel Richardson'' (1753)

*''An Address to the Public'' (1754)

*''2 Letters Concerning Sir Charles Grandison'' (1754)

*''A Collection of Moral Sentiments'' (1755)

*''Conjectures on Original Composition in a Letter to the Author'' 1st and 2nd editions (1759) (with Edward Young

Edward Young (c. 3 July 1683 – 5 April 1765) was an English poet, best remembered for ''Night-Thoughts'', a series of philosophical writings in blank verse, reflecting his state of mind following several bereavements. It was one of the mo ...

)

As editor

*''Aesop's Fables

Aesop's Fables, or the Aesopica, is a collection of fables credited to Aesop, a slave and storyteller believed to have lived in ancient Greece between 620 and 564 BCE. Of diverse origins, the stories associated with his name have descended to ...

'' – 1st, 2nd, and 3rd editions (1739–1753)

*''The Negotiations of Thomas Roe'' (1740)

*''A Tour through Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

'' (4 Volumes) by Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe (; born Daniel Foe; – 24 April 1731) was an English writer, trader, journalist, pamphleteer and spy. He is most famous for his novel '' Robinson Crusoe'', published in 1719, which is claimed to be second only to the Bible in its ...

– 3rd, 4th, 5th, and 6th editions (1742–1761)

*''The Life of Sir William Harrington (knight)'' by Anna Meades – revised and corrected

Other works

*''The Apprentice's Vade Mecum'' (1734) *''A Seasonable Examination of the Pleas and Pretensions Of the Proprietors of, and Subscribers to, Play-Houses, Erected in Defiance of the Royal License. With Observations on the Printed Case of the Players belonging to Drury-Lane and Covent-Garden Theatres'' (1735) *''Verses Addressed to Edward Cave and William Bowyer'' (1736) *''A compilation of letters published as a manual, with directions on How to think and act justly and prudently in the Common Concerns of Human Life'' (1741) *''The Familiar Letters'' 6 Editions (1741–1755) *''The Life and heroic Actions of Balbe Berton, Chevalier de Grillon'' (2 volumes) 1st and 2nd Editions by Lady Marguerite de Lussan (as assistant translator of an anonymous female translator) *''No. 97, The Rambler'' (1751)Posthumous Works

*''6 Letters upon Duelling'' (1765) *''Letter from an Uncle to his Nephew'' (1804)Notes

References

*Braudy, Leo. "Penetration and Impenetrability in ''Clarissa''," ''New Approaches to Eighteenth-Century Literature: Selected Papers from the English Institute'' edited by Philip Harth. New York: Columbia University Press, 1974 * *Flynn, Carol, ''Samuel Richardson: A Man of Letters''. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982 * * * * *Rizzo, Betty. ''Companions Without Vows: Relationships Among Eighteenth–Century British Women''. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 1994. 439 pp. * * * *Townsend, Alex, Autonomous Voices: An Exploration of Polyphony in the Novels of Samuel Richardson, 2003, Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt/M., New York, Wien, 2003,External links

* * * * * * *Samuel Richardson

at the

National Portrait Gallery, London

The National Portrait Gallery (NPG) is an art gallery in London housing a collection of portraits of historically important and famous British people. It was arguably the first national public gallery dedicated to portraits in the world when it ...

*''The Spiritual Side of Samuel Richardson: Mysticism, Behmenism and Millenarianism in an Eighteenth–Century English Novelist'', G. J. Joling–van der Sar, 200* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Richardson, Samuel English printers English Anglicans People from Mackworth People from Parsons Green 1689 births 1761 deaths 18th-century English writers 18th-century English male writers 18th-century English novelists English male novelists