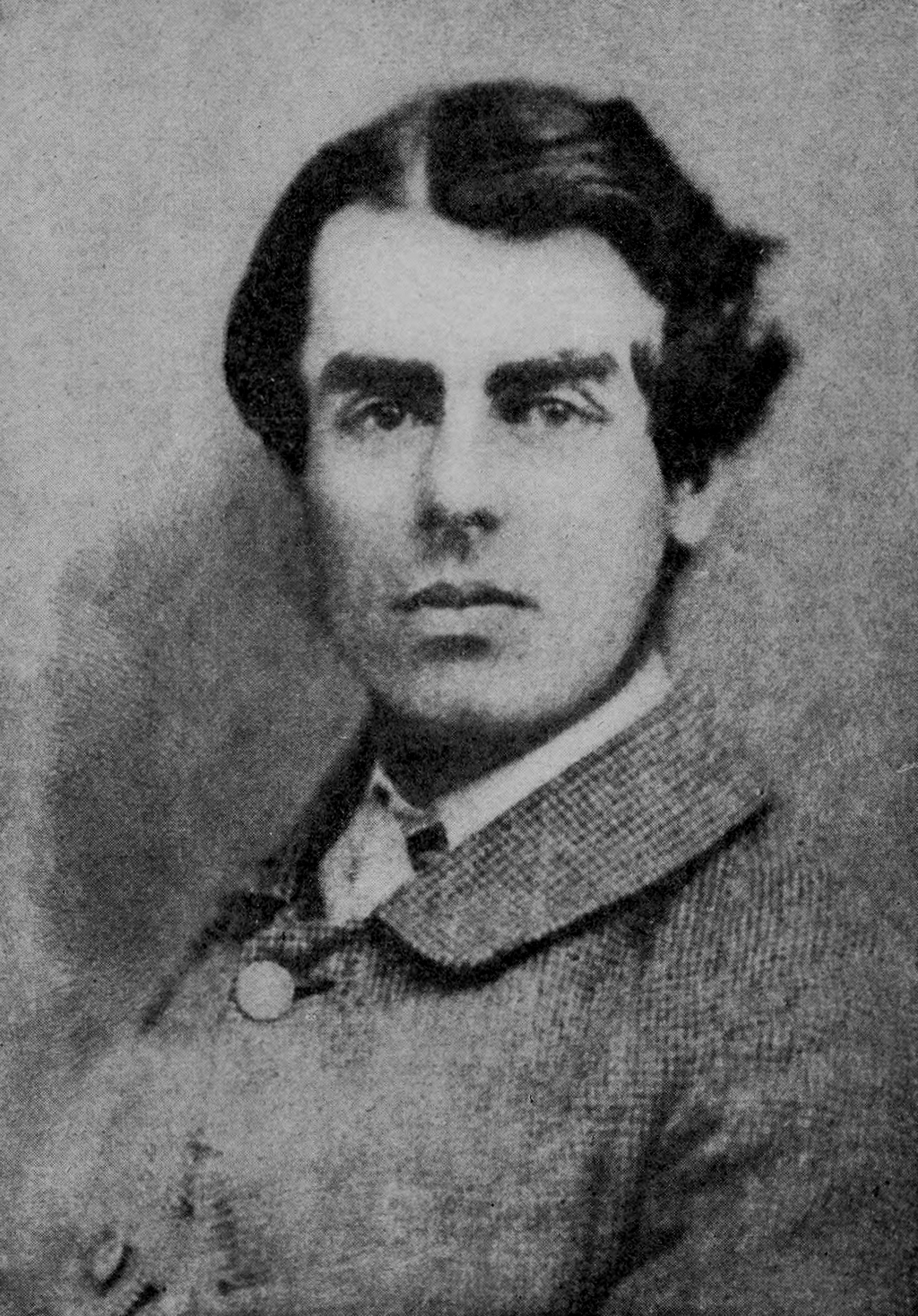

Samuel Butler (1835–1902) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Samuel Butler (4 December 1835 – 18 June 1902) was an English novelist and critic, best known for the satirical

Butler was born on 4 December 1835 at the rectory in the village of

Butler was born on 4 December 1835 at the rectory in the village of

/ref> Samuel Butler's relations with his parents, especially with his father, were largely antagonistic. His education began at home and included frequent beatings, as was not uncommon at the time. Samuel wrote later that his parents were "brutal and stupid by nature". He later recorded that his father "never liked me, nor I him; from my earliest recollections I can call to mind no time when I did not fear him and dislike him.... I have never passed a day without thinking of him many times over as the man who was sure to be against me." Under his parents' influence, he was set on course to follow his father into the priesthood. He was sent to Shrewsbury at age twelve, where he did not enjoy the hard life under its headmaster

After Cambridge, he went to live in a low-income parish in London 1858–1859 as preparation for his

After Cambridge, he went to live in a low-income parish in London 1858–1859 as preparation for his

''Alps and Sanctuaries of Piedmont and the Canton Ticino''

(1881) and ''Ex Voto'' (1888). He wrote a number of other books, including a less successful sequel, '' Erewhon Revisited''. His semi-autobiographical novel, ''The Way of All Flesh'', did not appear in print until after his death, as he considered its tone of satirical attack on

''Samuel Butler: Victorian against the Grain, a Critical Overview''. Ed. James G. Paradis. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2007. His first significant male friendship was with the young Charles Pauli, son of a German businessman in London, whom Butler met in New Zealand. They returned to England together in 1864 and took neighbouring apartments in Clifford's Inn. Butler had made a large profit from the sale of his New Zealand farm and undertook to finance Pauli's study of law by paying him a regular sum, which Butler continued to do long after the friendship had cooled, until Butler had spent all his savings. On Pauli's death in 1892, Butler was shocked to learn that Pauli had benefited from similar arrangements with other men and had died wealthy, but without leaving Butler anything in his will.

''glbtq: An Encyclopedia of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Culture'', glbtq.com, 21 July 2006, accessed 8 May 2012.Robinson, J. Z. "Samuel Butler." ''Who's Who in Gay and Lesbian History: From Antiquity to World War II'', Robert Aldrich and Garry Wotherspoon, eds.

New York: Routledge, 2001, pp. 90–91. After 1878, Butler became close friends with Henry Festing Jones, whom Butler persuaded to give up his job as a solicitor to be Butler's personal literary assistant and travelling companion, at a salary of £200 a year. Although Jones kept his own lodgings at

London: Macmillan, 1919. instructing his literary agent to offer it for publication to several leading English magazines. However, once the Oscar Wilde trial began in the spring of that year, with revelations of homosexual behaviour among the literati, Butler feared being associated with the widely reported scandal and in a panic wrote to all the magazines, withdrawing his poem. A number of critics, beginning with

Samuel Butler: English author [1835-1902]

''Britannica'' etrieved 2016-06-13/ref> *''Lucubratio Ebria'' (1865) *''

''Life and Habit''

(1878). Trubner (reissued by

''Evolution, Old and New; Or, the Theories of Buffon, Dr. Erasmus Darwin, and Lamarck, as compared with that of Charles Darwin''

(1879) *''Unconscious Memory'' (1880) *''Alps and Sanctuaries of Piedmont and the Canton Ticino'' (1881)

''Luck or Cunning as the Main Means of Organic Modification?''

(1887) *''Ex Voto; An Account of the Sacro Monte or New Jerusalem at Verallo-Sesia. With some notice of Tabachetti's remaining work at the Sanctuary of Crea'' (1888) *''The Life and Letters of Dr. Samuel Butler, Head-Master of Shrewsbury School 1798–1836, and Afterwards Bishop of Lichfield, In So Far as They Illustrate the Scholastic, Religious, and Social Life of England, 1790–1840. By His Grandson, Samuel Butler'' (1896, two volumes) *''The Authoress of the Odyssey'' (1897) *''The Iliad of Homer, Rendered into English Prose'' (1898) *''Shakespeare's Sonnets Reconsidered'' (1899) *''The Odyssey of Homer, Rendered into English Prose'' (1900) *'' Erewhon Revisited Twenty Years Later: Both by the Original Discoverer of the Country and by His Son'' (1901) *''

''God the Known and God the Unknown''

(1909). This is a revised edition, posthumously published. R.A. Streatfeild's "Prefatory Note" to it states that the original edition "first appeared in the form of a series of articles which were published in 'The Examiner' in May, June and July, 1879."The revised edition was also published as ''God: Known and Unknown'' (Girard, Kansas: Haldeman-Julius Company, no date).

''The Note-Books of Samuel Butler''

Selections arranged and edited by Henry Festing Jones (1912) *''Further Extracts from the Note-Books of Samuel Butler'' chosen and edited by A.T. Bartholomew (1934) *''Samuel Butler's Notebooks'' Selections edited by Geoffrey Keynes and Brian Hill (1951) *''The Family Letters of Samuel Butler 1841-1886'' Selected, Edited and Introduced by Arnold Silver (1962) *''The Correspondence of Samuel Butler with His Sister May'' Edited with an Introduction by Daniel F. Howard (1962) *''The Fair Haven'' (1873, new edition 1913, revised and corrected edition 1923; considers inconsistencies between the Gospels) *

' (1914) *''Selected Essays'' (1927) *''Butleriana'', A. T. Bartholomew, ed. (1932). Bloomsbury: The Nonesuch Press *''The Essential Samuel Butler'' Selected with an Introduction by G. D. H. Cole (1950)

''Samuel Butler's God''

''

Official English website for European Sacred MountsDarwin Among the Machines: Russian translation «Дарвин среди Машин»

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Butler, Samuel 1835 births 1902 deaths Alumni of St John's College, Cambridge English satirists Writers from London People educated at Shrewsbury School People from Bingham, Nottinghamshire New Zealand farmers Victorian novelists 19th-century English novelists Charles Darwin biographers English male novelists Lamarckism Theistic evolutionists Translators of Ancient Greek texts Translators of Homer

utopian

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imaginary community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book ''Utopia'', describing a fictional island society ...

novel ''Erewhon

''Erewhon: or, Over the Range'' () is a novel by English writer Samuel Butler, first published anonymously in 1872, set in a fictional country discovered and explored by the protagonist. The book is a satire on Victorian society.

The fir ...

'' (1872) and the semi-autobiographical novel ''Ernest Pontifex or The Way of All Flesh

''The Way of All Flesh'' (sometimes called ''Ernest Pontifex, or the Way of All Flesh'') is a semi-autobiographical novel by Samuel Butler that attacks Victorian-era hypocrisy. Written between 1873 and 1884, it traces four generations of the ...

'', published posthumously in 1903 in an altered version titled ''The Way of All Flesh'', and published in 1964 as he wrote it. Both novels have remained in print since their initial publication. In other studies he examined Christian orthodoxy, evolutionary thought, and Italian art, and made prose translations of the ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the '' Odys ...

'' and ''Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; grc, Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia, ) is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Iliad'', th ...

'' that are still consulted.

Early life

Butler was born on 4 December 1835 at the rectory in the village of

Butler was born on 4 December 1835 at the rectory in the village of Langar, Nottinghamshire

Langar is an English village in the Vale of Belvoir, about four miles (6.4 km) south of Bingham, in the Rushcliffe borough of Nottinghamshire. The civil parish of Langar cum Barnstone had a population of 980 at the 2011 Census. This was estim ...

. His father was Rev. Thomas Butler, son of Dr. Samuel Butler, then headmaster of Shrewsbury School

Shrewsbury School is a public school (English independent boarding school for pupils aged 13 –18) in Shrewsbury.

Founded in 1552 by Edward VI by Royal Charter, it was originally a boarding school for boys; girls have been admitted into ...

and later Bishop of Lichfield

The Bishop of Lichfield is the ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Lichfield in the Province of Canterbury. The diocese covers 4,516 km2 (1,744 sq. mi.) of the counties of Powys, Staffordshire, Shropshire, Warwickshire and Wes ...

. Dr. Butler was the son of a tradesman and descended from a line of yeomen

Yeoman is a noun originally referring either to one who owns and cultivates land or to the middle ranks of servants in an English royal or noble household. The term was first documented in mid-14th-century England. The 14th century also witn ...

, but his scholarly aptitude being recognised at a young age, he had been sent to Rugby

Rugby may refer to:

Sport

* Rugby football in many forms:

** Rugby league: 13 players per side

*** Masters Rugby League

*** Mod league

*** Rugby league nines

*** Rugby league sevens

*** Touch (sport)

*** Wheelchair rugby league

** Rugby union: 1 ...

and Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a College town, university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cam ...

, where he distinguished himself.

His only son, Thomas, wished to go into the Navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It in ...

but succumbed to paternal pressure and entered the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

, in which he led an undistinguished career, in contrast to his father's. Samuel's immediate family created for him an oppressive home environment (chronicled in ''The Way of All Flesh

''The Way of All Flesh'' (sometimes called ''Ernest Pontifex, or the Way of All Flesh'') is a semi-autobiographical novel by Samuel Butler that attacks Victorian-era hypocrisy. Written between 1873 and 1884, it traces four generations of the ...

''). Thomas Butler, states one critic, "to make up for having been a servile son, became a bullying father."Clara G. Stillman, ''Samuel Butler, a Mid-Victorian Modern'' Retrieved 11 May 2020./ref> Samuel Butler's relations with his parents, especially with his father, were largely antagonistic. His education began at home and included frequent beatings, as was not uncommon at the time. Samuel wrote later that his parents were "brutal and stupid by nature". He later recorded that his father "never liked me, nor I him; from my earliest recollections I can call to mind no time when I did not fear him and dislike him.... I have never passed a day without thinking of him many times over as the man who was sure to be against me." Under his parents' influence, he was set on course to follow his father into the priesthood. He was sent to Shrewsbury at age twelve, where he did not enjoy the hard life under its headmaster

Benjamin Hall Kennedy

Benjamin Hall Kennedy (6 November 1804 – 6 April 1889) was an English scholar and schoolmaster, known for his work in the teaching of the Latin language. He was an active supporter of Newnham College and Girton College as Cambridge University ...

, whom he later drew as "Dr. Skinner" in ''The Way of All Flesh''. Then in 1854 he went up to St John's College, Cambridge, where he obtained a first

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

in Classics in 1858. (The graduate society of St John's is named the Samuel Butler Room (SBR) in his honour.)

Career

After Cambridge, he went to live in a low-income parish in London 1858–1859 as preparation for his

After Cambridge, he went to live in a low-income parish in London 1858–1859 as preparation for his ordination

Ordination is the process by which individuals are consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the denominational hierarchy composed of other clergy) to perform v ...

into the Anglican clergy; there he discovered that infant baptism

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost ...

made no apparent difference to the morals and behaviour of his peers and began questioning his faith. This experience would later serve as inspiration for his work ''The Fair Haven''. Correspondence with his father about the issue failed to set his mind at peace, instead inciting his father's wrath. As a result, in September 1859, on the ship ''Roman Emperor'', he emigrated to New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

.

Butler went there, like many early British settlers of materially privileged origins, to maximise distance between himself and his family. He wrote of his arrival and life as a sheep farmer on Mesopotamia Station

Mesopotamia Station is a high-country station in New Zealand's South Island. Known mainly for one of its first owners, the novelist Samuel Butler, it is probably the country's best known station. Despite popular belief, Butler was not the stati ...

in ''A First Year in Canterbury Settlement'' (1863), and he made a handsome profit when he sold his farm, but his chief achievement during his time there consisted of drafts and source material for much of his masterpiece ''Erewhon

''Erewhon: or, Over the Range'' () is a novel by English writer Samuel Butler, first published anonymously in 1872, set in a fictional country discovered and explored by the protagonist. The book is a satire on Victorian society.

The fir ...

''.

''Erewhon'' revealed Butler's long interest in Darwin's theories of biological evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

. In 1863, four years after Darwin published ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life''),The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by Me ...

'', the editor of a New Zealand newspaper, ''The Press

''The Press'' is a daily newspaper published in Christchurch, New Zealand owned by media business Stuff Ltd. First published in 1861, the newspaper is the largest circulating daily in the South Island and publishes Monday to Saturday. One comm ...

'', published a letter captioned "Darwin among the Machines

"Darwin among the Machines" is an article published in ''The Press'' newspaper on 13 June 1863 in Christchurch, New Zealand, which references the work of Charles Darwin in the title. Written by Samuel Butler but signed '' Cellarius'' (q.v.), the ...

", written by Butler, but signed ''Cellarius''. It compares human evolution to machine evolution, prophesying that machines would eventually replace humans in the supremacy of the earth: "In the course of ages we shall find ourselves the inferior race". The letter raises many of the themes now debated by proponents of the technological singularity

The technological singularity—or simply the singularity—is a hypothetical future point in time at which technological growth becomes uncontrollable and irreversible, resulting in unforeseeable changes to human civilization. According to the m ...

, for example that computers evolve much faster than humans and that we are racing toward an unknowable future through explosive technological change.

Butler also spent time criticising Darwin, partly because Butler (in the shadow of a previous Samuel Butler) believed that Darwin had not sufficiently acknowledged his grandfather Erasmus Darwin's contribution to his theory.

Butler returned to England in 1864, settling in rooms in Clifford's Inn

Clifford's Inn is a former Inn of Chancery in London. It was located between Fetter Lane, Clifford's Inn Passage, leading off Fleet Street and Chancery Lane in the City of London. The Inn was founded in 1344 and refounded 15 June 1668. It was d ...

(near Fleet Street), where he lived for the rest of his life. In 1872, the Utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imaginary community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book '' Utopia'', describing a fictional island societ ...

n novel ''Erewhon

''Erewhon: or, Over the Range'' () is a novel by English writer Samuel Butler, first published anonymously in 1872, set in a fictional country discovered and explored by the protagonist. The book is a satire on Victorian society.

The fir ...

'' appeared anonymously, causing some speculation as to who the author was. When Butler revealed himself, ''Erewhon'' made him a well-known figure, more because of this speculation than for its literary merits, which have been undisputed.

He was less successful when he lost money investing in a Canadian steamship company and in the Canada Tanning Extract Company, in which he and his friend Charles Pauli were made nominal directors. In 1874 Butler went to Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

, "fighting fraud of every kind" in an attempt to save the company, which collapsed, reducing his own capital to £2,000.

In 1839 his grandfather Dr Butler had left Samuel property at Whitehall in Abbey Foregate, Shrewsbury, so long as he survived his own father and his aunt, Dr Butler's daughter Harriet Lloyd. While at Cambridge in 1857 he sold the Whitehall mansion and six acres to his cousin Thomas Bucknall Lloyd, but kept the remaining land surrounding the mansion. His aunt died in 1880 and his father's death in 1886 resolved his financial problems for the last 16 years of his own life. The land at Whitehall was sold for housing development; he laid out and named four roads – Bishop and Canon Streets after his grandfather's and father's clerical titles, Clifford Street after his London home, and Alfred Street in gratitude to his clerk. When in the 1870s his old Shrewsbury School proposed to relocate to a site at Whitehall, Butler publicly opposed it and the school ultimately moved elsewhere.

Butler indulged himself, holidaying in Italy every summer and while there, producing his works on the Italian landscape and art. His close interest in the art of the Sacri Monti

The (plural of , Italian for "Sacred Mountain") of Piedmont and Lombardy are a series of nine calvaries or groups of chapels and other architectural features created in northern Italy during the late sixteenth century and the seventeenth century ...

is reflected i''Alps and Sanctuaries of Piedmont and the Canton Ticino''

(1881) and ''Ex Voto'' (1888). He wrote a number of other books, including a less successful sequel, '' Erewhon Revisited''. His semi-autobiographical novel, ''The Way of All Flesh'', did not appear in print until after his death, as he considered its tone of satirical attack on

Victorian morality

Victorian morality is a distillation of the moral views of the middle class in 19th-century Britain, the Victorian era.

Victorian values emerged in all classes and reached all facets of Victorian living. The values of the period—which can be ...

too contentious at the time.

Butler died on 18 June 1902, aged 66, in a nursing home Article by "E. M. L." (Colonel E. M. Lloyd). in St. John's Wood Road, London.Article by Elinor Shaffer. By his wish, he was cremated at Woking Crematorium

Woking Crematorium is a crematorium in Woking, a large town in the west of Surrey, England. Established in 1878, it was the first custom-built crematorium in the United Kingdom and is closely linked to the history of cremation in the UK.

Loc ...

and by differing accounts, his ashes were dispersed or buried in an unmarked grave.

George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

and E. M. Forster

Edward Morgan Forster (1 January 1879 – 7 June 1970) was an English author, best known for his novels, particularly ''A Room with a View'' (1908), ''Howards End'' (1910), and ''A Passage to India'' (1924). He also wrote numerous short stori ...

were great admirers of the later Samuel Butler, who brought a new tone into Victorian literature and began a long tradition of New Zealand utopian/dystopian literature that culminated in works by Jack Ross, William Direen, Alan Marshall and Scott Hamilton.

Sexuality

Butler's sexuality has been the subject of academic speculation and debate. Butler never married, although for years he made regular visits to a woman, Lucie Dumas. Herbert Sussman, having arrived at the conclusion that Butler was homosexual, opined that Butler's sexual association with Dumas was merely an outlet for his "intense same-sex desire". Sussman's theory calls Butler's assumption of "bachelorhood" merely a means to retain middle-class respectability in the absence of matrimony; he observes that there is no evidence of Butler's having any "genital contact with other men," but alleges that the "temptations of overstepping the line strained his close male relationships."Sussman, Herbert. "Samuel Butler as Late-Victorian Bachelor: Regulating and Representing the Homoerotic."''Samuel Butler: Victorian against the Grain, a Critical Overview''. Ed. James G. Paradis. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2007. His first significant male friendship was with the young Charles Pauli, son of a German businessman in London, whom Butler met in New Zealand. They returned to England together in 1864 and took neighbouring apartments in Clifford's Inn. Butler had made a large profit from the sale of his New Zealand farm and undertook to finance Pauli's study of law by paying him a regular sum, which Butler continued to do long after the friendship had cooled, until Butler had spent all his savings. On Pauli's death in 1892, Butler was shocked to learn that Pauli had benefited from similar arrangements with other men and had died wealthy, but without leaving Butler anything in his will.

''glbtq: An Encyclopedia of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Culture'', glbtq.com, 21 July 2006, accessed 8 May 2012.Robinson, J. Z. "Samuel Butler." ''Who's Who in Gay and Lesbian History: From Antiquity to World War II'', Robert Aldrich and Garry Wotherspoon, eds.

New York: Routledge, 2001, pp. 90–91. After 1878, Butler became close friends with Henry Festing Jones, whom Butler persuaded to give up his job as a solicitor to be Butler's personal literary assistant and travelling companion, at a salary of £200 a year. Although Jones kept his own lodgings at

Barnard's Inn

Barnard's Inn is a former Inn of Chancery in Holborn, London. It is now the home of Gresham College, an institution of higher learning established in 1597 that hosts public lectures.

History

Barnard's Inn dates back at least to the mid-thirt ...

, the two men saw each other daily until Butler's death in 1902, collaborating on music and writing projects in the daytime, and attending concerts and theatres in the evenings; they also frequently toured Italy and other favourite parts of Europe together. After Butler's death, Jones edited Butler's notebooks for publication and published his own biography of him in 1919.

Another friendship was with Hans Rudolf Faesch, a Swiss student who stayed with Butler and Jones in London for two years, improving his English, before departing for Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, bor ...

. Both Butler and Jones wept when they saw him off at the railway station in early 1895, and Butler subsequently wrote an emotional poem, "In Memoriam H. R. F.," Henry Festing Jones, ''Samuel Butler, Author of'' Erewhon ''(1835–1902): A Memoir''."> Henry Festing Jones, ''Samuel Butler, Author of'' Erewhon ''(1835–1902): A Memoir''.London: Macmillan, 1919. instructing his literary agent to offer it for publication to several leading English magazines. However, once the Oscar Wilde trial began in the spring of that year, with revelations of homosexual behaviour among the literati, Butler feared being associated with the widely reported scandal and in a panic wrote to all the magazines, withdrawing his poem. A number of critics, beginning with

Malcolm Muggeridge

Thomas Malcolm Muggeridge (24 March 1903 – 14 November 1990) was an English journalist and satirist. His father, H. T. Muggeridge, was a socialist politician and one of the early Labour Party Members of Parliament (for Romford, in Essex). In ...

in ''The Earnest Atheist: A Study of Samuel Butler'' (1936), concluded that Butler was a sublimated or repressed homosexual and that his lifelong status as an "incarnate bachelor" was comparable to that of his writer contemporaries Walter Pater

Walter Horatio Pater (4 August 1839 – 30 July 1894) was an English essayist, art critic and literary critic, and fiction writer, regarded as one of the great stylists. His first and most often reprinted book, ''Studies in the History of the Re ...

, Henry James

Henry James ( – ) was an American-British author. He is regarded as a key transitional figure between literary realism and literary modernism, and is considered by many to be among the greatest novelists in the English language. He was the ...

, and E. M. Forster

Edward Morgan Forster (1 January 1879 – 7 June 1970) was an English author, best known for his novels, particularly ''A Room with a View'' (1908), ''Howards End'' (1910), and ''A Passage to India'' (1924). He also wrote numerous short stori ...

, also assumed to be closeted homosexuals.

Literary history and criticism

Butler developed a theory that the ''Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; grc, Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia, ) is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Iliad'', th ...

'' came from the pen of a young Sicilian woman, and that the scenes of the poem reflected the coast of Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

(especially the territory of Trapani

Trapani ( , ; scn, Tràpani ; lat, Drepanum; grc, Δρέπανον) is a city and municipality (''comune'') on the west coast of Sicily, in Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Trapani. Founded by Elymians, the city is still an imp ...

) and its nearby islands. He described his evidence for this in ''The Authoress of the Odyssey'' (1897) and in the introduction and footnotes to his prose translation of the ''Odyssey'' (1900). Robert Graves elaborated on the hypothesis in his novel ''Homer's Daughter

''Homer's Daughter'' is a 1955 novel by British author Robert Graves, famous for ''I, Claudius'' and ''The White Goddess''.

The novel starts from the idea that Homer's ''Odyssey'' was written by a princess in the Greek settlements in Sicily. Th ...

''.

Butler argued in a lecture entitled "The Humour of Homer", delivered at The Working Men's College in London, 1892, that Homer's deities in the ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the '' Odys ...

'' are like humans, but "without the virtue", and that he "must have desired his listeners not to take them seriously." Butler translated the ''Iliad'' (1898). His other works include '' Shakespeare's Sonnets Reconsidered'' (1899), a theory that the sonnets, if rearranged, tell a story about a homosexual affair.

The English novelist Aldous Huxley

Aldous Leonard Huxley (26 July 1894 – 22 November 1963) was an English writer and philosopher. He wrote nearly 50 books, both novels and non-fiction works, as well as wide-ranging essays, narratives, and poems.

Born into the prominent Huxle ...

acknowledged the influence of ''Erewhon

''Erewhon: or, Over the Range'' () is a novel by English writer Samuel Butler, first published anonymously in 1872, set in a fictional country discovered and explored by the protagonist. The book is a satire on Victorian society.

The fir ...

'' on his novel ''Brave New World

''Brave New World'' is a dystopian novel by English author Aldous Huxley, written in 1931 and published in 1932. Largely set in a futuristic World State, whose citizens are environmentally engineered into an intelligence-based social hiera ...

''. Huxley's Utopian counterpart to ''Brave New World'', ''Island

An island (or isle) is an isolated piece of habitat that is surrounded by a dramatically different habitat, such as water. Very small islands such as emergent land features on atolls can be called islets, skerries, cays or keys. An island ...

'', also refers prominently to ''Erewhon''. In ''From Dawn to Decadence

''From Dawn to Decadence: 500 Years of Western Cultural Life'' is a book written by Jacques Barzun. Published in 2000, it is a large-scale survey history of trends in history, politics, culture, and ideas in Western civilization, and argues that, ...

'', Jacques Barzun

Jacques Martin Barzun (; November 30, 1907 – October 25, 2012) was a French-American historian known for his studies of the history of ideas and cultural history. He wrote about a wide range of subjects, including baseball, mystery novels, and ...

asks, "Could a man do more to bewilder the public?"

Assessment

Butler belonged to no literary school and spawned no followers in his lifetime. He was a serious but amateur student of the subjects he undertook, especially religious orthodoxy and evolutionary thought, and his controversial assertions effectively shut him out from both the opposing factions of church and science that played such a large role in late Victorian cultural life: "In those days one was either a religionist or aDarwinian

Darwinism is a theory of biological evolution developed by the English naturalist Charles Darwin (1809–1882) and others, stating that all species of organisms arise and develop through the natural selection of small, inherited variations that ...

, but he was neither."

His influence on literature, such as it was, came through ''The Way of All Flesh'', which Butler completed in the 1880s, but left unpublished to protect his family, yet the novel, "begun in 1870 and not touched after 1885, was so modern when it was published in 1903, that it may be said to have started a new school," particularly for its use of psychoanalysis

PsychoanalysisFrom Greek: + . is a set of theories and therapeutic techniques"What is psychoanalysis? Of course, one is supposed to answer that it is many things — a theory, a research method, a therapy, a body of knowledge. In what might b ...

in fiction, which "his treatment of Ernest Pontifex he heroforeshadows."

Philosophy and personal thought

Whether in hissatire

Satire is a genre of the visual, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, often with the intent of shaming ...

and fiction, Butler's studies on the evidences for Christianity, his works on evolutionary thought, or in his miscellaneous other writings, a consistent theme runs through, stemming largely from his personal struggle against the stifling of his own nature by his parents, which led him to seek more general principles of growth, development, and purpose: "What concerned him was to establish his nature, his aspirations and their fulfillment upon a philosophic basis, to identify them with the nature, the aspirations, the fulfillment of all humanity – and more than that – with the fulfillment of the universe.... His struggle became generalized, symbolic, tremendous."

The form that this search took was principally philosophical and – given the interests of the day – biological: "Satirist, novelist, artist and critic that he was, he was primarily a philosopher," and in particular, a philosopher who looked for biological foundations for his work: "His biology was a bridge to a philosophy of life which sought a scientific basis for religion and endowed a naturalistically conceived universe with a soul." Indeed, "philosophical writer" was ultimately the self-description Butler chose as most fitting to his work.

Theology

In a book of essays published after his death entitled ''God the Known and God the Unknown'', Samuel Butler argued for the existence of a single, corporeal deity, declaring belief in an incorporeal deity to be essentially the same as atheism. He asserted that this "body" of God was, in fact, composed of the bodies of all living things on earth, a belief that may be classed as " panzoism". He later changed his views and decided that God was composed not only of all living things, but of all non-living things as well. He argued, however, that "some vaster Person ayloom ... out behind our God, and ... stand in relation to him as he to us. And behind this vaster and more unknown God there may be yet another, and another, and another."Heredity

Samuel Butler argued that each organism was not, in fact, distinct from its parents. Instead, he asserted that each being was merely an extension of its parents at a later stage of evolution. "Birth," he once quipped, "has been made too much of."Evolution

Butler accepted evolution, but rejected Darwin's theory ofnatural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Cha ...

.Mark A. Bedau, Carol E. Cleland. (2010). ''The Nature of Life: Classical and Contemporary Perspectives from Philosophy and Science''. Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press is the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted letters patent by King Henry VIII in 1534, it is the oldest university press in the world. It is also the King's Printer.

Cambridge University Pre ...

. pp. 344–345. In his book ''Evolution, Old and New'' (1879) he accused Darwin of borrowing heavily from Buffon, Erasmus Darwin, and Lamarck

Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, chevalier de Lamarck (1 August 1744 – 18 December 1829), often known simply as Lamarck (; ), was a French naturalist, biologist, academic, and soldier. He was an early proponent of the idea that biolo ...

, while playing down these influences and giving them little credit.Peter J. Bowler (2003), ''Evolution: The History of an Idea''. University of California Press

The University of California Press, otherwise known as UC Press, is a publishing house associated with the University of California that engages in academic publishing. It was founded in 1893 to publish scholarly and scientific works by facult ...

. p. 259. . In 1912, the biologist Vernon Kellogg summed up Butler's views:

Butler, though strongly anti-Darwinian (that is, anti-natural selection and anti-Charles Darwin) is not anti-evolutionist. He professes, indeed, to be very much of an evolutionist, and in particular one who has taken it upon his shoulders to reinstate Buffon and Erasmus Darwin, and, as a follower of these two, Lamarck, in their rightful place as the most believable explainers of the factors and method of evolution. His evolution belief is a sort of Butlerized Lamarckism, tracing back originally to Buffon and Erasmus Darwin.Historian Peter J. Bowler has described Butler as a defender of neo-Lamarckian evolution. Bowler noted that "Butler began to see in Lamarckism the prospect of retaining an indirect form of the design argument. Instead of creating from without, God might exist within the process of living development, represented by its innate creativity." Butler's writings on evolution were criticized by scientists. Critics have pointed out that Butler admitted to be writing entertainment rather than science and his writings were not taken seriously by most professional biologists. Butler's books were negatively reviewed in ''

Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are ...

'' by George Romanes

George John Romanes FRS (20 May 1848 – 23 May 1894) was a Canadian-Scots evolutionary biologist and physiologist who laid the foundation of what he called comparative psychology, postulating a similarity of cognitive processes and mechanism ...

and Alfred Russel Wallace. Romanes stated that Butler's views on evolution had no basis from science.

Gregory Bateson often mentioned Butler and saw value in some of his ideas, calling him "the ablest contemporary critic of Darwinian evolution". He noted Butler's insight into the efficiencies of habit formation (patterns of behaviour and mental processes) in adapting to an environment:

...mind and pattern as the explanatory principles which, above all, required investigation were pushed out of biological thinking in the later evolutionary theories which were developed in the mid-nineteenth century by Darwin, Huxley, etc. There were still some naughty boys, like Samuel Butler, who said that mind could not be ignored in this way – but they were weak voices, and incidentally, they never looked at organisms. I don't think Butler ever looked at anything except his own cat, but he still knew more about evolution than some of the more conventional thinkers.

Music

In ''Ernest Pontifex or The Way of All Flesh'', protagonist Ernest Pontifex says that he had been trying all his life to like modern music but succeeded less and less as he grew older. On being asked when he considers modern music to have begun, he says, "withSebastian Bach

Sebastian Philip Bierk (born April 3, 1968), known professionally as Sebastian Bach, is a Canadian-American singer who achieved mainstream success as the frontman of the hard rock band Skid Row from 1987 to 1996. He has acted on Broadway and ha ...

". Butler liked only Handel, and in a letter to Miss Savage said, "I only want Handel's Oratorios. I would have said and things of that sort, but there are no 'things of that sort' except Handel's." With Henry Festing Jones, Butler composed choral works that Eric Blom characterized as "imitation Handel", although with satirical texts. Two of the works they collaborated on were the cantatas ''Narcissus'' (private rehearsal 1886, published 1888), and ''Ulysses'' (published posthumously in 1904), both for solo voices, chorus, and orchestra. George Bernard Shaw wrote in a private letter that the music was invested with "a ridiculously complete command of the Handelian manner and technique." Around 1871 Butler was engaged as music critic by ''The Drawing Room Gazette''. From 1890 he took counterpoint lessons with W. S. Rockstro

William Smith Rockstro (5 January 1823 – 1 July 1895) was an English musicologist, teacher, pianist and composer. He is best remembered for his books, including music textbooks, music history and biographies of famous musicians.

Life and caree ...

.

Biography and criticism

Butler's friend Henry Festing Jones wrote the authoritativebiography

A biography, or simply bio, is a detailed description of a person's life. It involves more than just the basic facts like education, work, relationships, and death; it portrays a person's experience of these life events. Unlike a profile or ...

: the two-volume ''Samuel Butler, Author of Erewhon (1835–1902): A Memoir'' (commonly known as Jones's ''Memoir''), published in 1919 and reissued by HardPress Publishing in 2013. Project Gutenberg hosts a shorter "Sketch" by Jones. More recently, Peter Raby has written a life: ''Samuel Butler: A Biography'' (Hogarth Press, 1991).

''The Way of All Flesh'' was published after Butler's death by his literary executor, R. A. Streatfeild, in 1903. This version, however, altered Butler's text in many ways and cut important material. The manuscript was edited by Daniel F. Howard as ''Ernest Pontifex or The Way of All Flesh'' (Butler's original title) and published for the first time in 1964.

Main works

*''Darwin among the Machines

"Darwin among the Machines" is an article published in ''The Press'' newspaper on 13 June 1863 in Christchurch, New Zealand, which references the work of Charles Darwin in the title. Written by Samuel Butler but signed '' Cellarius'' (q.v.), the ...

'' (1863, largely incorporated into ''Erewhon'') Basil Willey �Samuel Butler: English author [1835-1902]

''Britannica'' etrieved 2016-06-13/ref> *''Lucubratio Ebria'' (1865) *''

Erewhon

''Erewhon: or, Over the Range'' () is a novel by English writer Samuel Butler, first published anonymously in 1872, set in a fictional country discovered and explored by the protagonist. The book is a satire on Victorian society.

The fir ...

, or Over the Range'' (1872)''Life and Habit''

(1878). Trubner (reissued by

Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press is the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted letters patent by King Henry VIII in 1534, it is the oldest university press in the world. It is also the King's Printer.

Cambridge University Pre ...

, 2009; )''Evolution, Old and New; Or, the Theories of Buffon, Dr. Erasmus Darwin, and Lamarck, as compared with that of Charles Darwin''

(1879) *''Unconscious Memory'' (1880) *''Alps and Sanctuaries of Piedmont and the Canton Ticino'' (1881)

''Luck or Cunning as the Main Means of Organic Modification?''

(1887) *''Ex Voto; An Account of the Sacro Monte or New Jerusalem at Verallo-Sesia. With some notice of Tabachetti's remaining work at the Sanctuary of Crea'' (1888) *''The Life and Letters of Dr. Samuel Butler, Head-Master of Shrewsbury School 1798–1836, and Afterwards Bishop of Lichfield, In So Far as They Illustrate the Scholastic, Religious, and Social Life of England, 1790–1840. By His Grandson, Samuel Butler'' (1896, two volumes) *''The Authoress of the Odyssey'' (1897) *''The Iliad of Homer, Rendered into English Prose'' (1898) *''Shakespeare's Sonnets Reconsidered'' (1899) *''The Odyssey of Homer, Rendered into English Prose'' (1900) *'' Erewhon Revisited Twenty Years Later: Both by the Original Discoverer of the Country and by His Son'' (1901) *''

The Way of All Flesh

''The Way of All Flesh'' (sometimes called ''Ernest Pontifex, or the Way of All Flesh'') is a semi-autobiographical novel by Samuel Butler that attacks Victorian-era hypocrisy. Written between 1873 and 1884, it traces four generations of the ...

'' (1903), text of original manuscript published as ''Ernest Pontifex or The Way of All Flesh'' (1964)''God the Known and God the Unknown''

(1909). This is a revised edition, posthumously published. R.A. Streatfeild's "Prefatory Note" to it states that the original edition "first appeared in the form of a series of articles which were published in 'The Examiner' in May, June and July, 1879."The revised edition was also published as ''God: Known and Unknown'' (Girard, Kansas: Haldeman-Julius Company, no date).

''The Note-Books of Samuel Butler''

Selections arranged and edited by Henry Festing Jones (1912) *''Further Extracts from the Note-Books of Samuel Butler'' chosen and edited by A.T. Bartholomew (1934) *''Samuel Butler's Notebooks'' Selections edited by Geoffrey Keynes and Brian Hill (1951) *''The Family Letters of Samuel Butler 1841-1886'' Selected, Edited and Introduced by Arnold Silver (1962) *''The Correspondence of Samuel Butler with His Sister May'' Edited with an Introduction by Daniel F. Howard (1962) *''The Fair Haven'' (1873, new edition 1913, revised and corrected edition 1923; considers inconsistencies between the Gospels) *

' (1914) *''Selected Essays'' (1927) *''Butleriana'', A. T. Bartholomew, ed. (1932). Bloomsbury: The Nonesuch Press *''The Essential Samuel Butler'' Selected with an Introduction by G. D. H. Cole (1950)

References

Further reading

*G. D. H. Cole

George Douglas Howard Cole (25 September 1889 – 14 January 1959) was an English political theorist, economist, and historian. As a believer in common ownership of the means of production, he theorised guild socialism (production organised ...

(1947), ''Samuel Butler and The Way of All Flesh''. London: Home & Van Thal Ltd

*Mrs. R. S. Garnett (1926), ''Samuel Butler and His Family Relations''. London/Toronto: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd

* Phyllis Greenacre, M.D. (1963), ''The Quest for the Father: A Study of the Darwin-Butler Controversy, As a Contribution to the Understanding of the Creative Individual''. New York: International Universities Press, Inc.

*Felix Grendon (1918)''Samuel Butler's God''

''

North American Review

The ''North American Review'' (NAR) was the first literary magazine in the United States. It was founded in Boston in 1815 by journalist Nathan Hale and others. It was published continuously until 1940, after which it was inactive until revived at ...

'', Vol. 208, No. 753, pp. 277–286

*John F. Harris (1916), ''Samuel Butler, Author of Erewhon: The Man and His Work''. London: Grant Richards Ltd

*Philip Henderson (1954), ''Samuel Butler: The Incarnate Bachelor''. Bloomington: Indiana University Press

*Lee Elbert Holt (1941), ''Samuel Butler and His Victorian Critics''. '' ELH'', Vol. 8, No. 2, pp. 146–159. The Johns Hopkins University Press

*Lee Elbert Holt (1964), ''Samuel Butler''. New York: Twayne Publishers, Inc.

*Thomas L. Jeffers (1981), ''Samuel Butler Revalued''. University Park: Penn State University Press

The Penn State University Press, also known as The Pennsylvania State University Press, was established in 1956 and is a non-profit publisher of scholarly books and journals. It is the independent publishing branch of the Pennsylvania State Un ...

* C. E. M. Joad (1924), ''Samuel Butler (1835–1902)''. London: Leonard Parsons

*Joseph Jones (1959), ''The Cradle of'' Erewhon: ''Samuel Butler in New Zealand''. Austin: University of Texas Press

*Malcolm Muggeridge

Thomas Malcolm Muggeridge (24 March 1903 – 14 November 1990) was an English journalist and satirist. His father, H. T. Muggeridge, was a socialist politician and one of the early Labour Party Members of Parliament (for Romford, in Essex). In ...

(1936), ''The Earnest Atheist: A Study of Samuel Butler''. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode

*James G. Paradis, ed. (2007), ''Samuel Butler, Victorian Against the Grain: A Critical Overview''. University of Toronto Press

The University of Toronto Press is a Canadian university press founded in 1901. Although it was founded in 1901, the press did not actually publish any books until 1911.

The press originally printed only examination books and the university cale ...

*Peter Raby (1991), ''Samuel Butler: A Biography''. University of Iowa Press The University of Iowa Press is a university press that is part of the University of Iowa.

Established in 1969, thUniversity of Iowa Pressis an academic publisher of poetry, short fiction, and creative nonfiction. The UI Press is the only universit ...

.

*Robert F. Rattray (1914), ''The Philosophy of Samuel Butler''. '' Mind'', Vol. 23, No. 91, pp. 371–385

*Robert F. Rattray (1935), ''Samuel Butler: A Chronicle and an Introduction''. London: Duckworth

*Elinor Shaffer (1988), ''Erewhons of the Eye: Samuel Butler as Painter, Photographer and Art Critic''. London: Reaktion Books

*George Gaylord Simpson (1961), ''Lamarck, Darwin and Butler: Three Approaches to Evolution''. ''The American Scholar

"The American Scholar" was a speech given by Ralph Waldo Emerson on August 31, 1837, to the Phi Beta Kappa Society of Harvard College at the First Parish in Cambridge in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He was invited to speak in recognition of his gro ...

'', Vol. 30, No. 2, pp. 238–249

*Clara G. Stillman (1932), ''Samuel Butler: A Mid-Victorian Modern''. New York: The Viking Press

* Basil Willey (1960), ''Darwin and Butler: Two Views of Evolution''. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company

External links

* * * * *Official English website for European Sacred Mounts

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Butler, Samuel 1835 births 1902 deaths Alumni of St John's College, Cambridge English satirists Writers from London People educated at Shrewsbury School People from Bingham, Nottinghamshire New Zealand farmers Victorian novelists 19th-century English novelists Charles Darwin biographers English male novelists Lamarckism Theistic evolutionists Translators of Ancient Greek texts Translators of Homer