Samhain on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Samhain ( , , , ; gv, Sauin ) is a

On

On

While Irish mythology was originally a spoken tradition, much of it was eventually written down in the Middle Ages by Christian

While Irish mythology was originally a spoken tradition, much of it was eventually written down in the Middle Ages by Christian  The legendary kings Diarmait mac Cerbaill and Muirchertach mac Ercae each die a threefold death on Samhain, which involves wounding, burning and drowning, and of which they are forewarned. In the tale '' Togail Bruidne Dá Derga'' ('The Destruction of Dá Derga's Hostel'), king

The legendary kings Diarmait mac Cerbaill and Muirchertach mac Ercae each die a threefold death on Samhain, which involves wounding, burning and drowning, and of which they are forewarned. In the tale '' Togail Bruidne Dá Derga'' ('The Destruction of Dá Derga's Hostel'), king  Several sites in Ireland are especially linked to Samhain. Each Samhain a host of otherworldly beings was said to emerge from the

Several sites in Ireland are especially linked to Samhain. Each Samhain a host of otherworldly beings was said to emerge from the

It is mentioned in Geoffrey Keating's '' Foras Feasa ar Éirinn'', which was written in the early 1600s but draws on earlier medieval sources, some of which are unknown. He claims that the '' feis'' of Tara was held for a week every third Samhain, when the nobles and ollams of Ireland met to lay down and renew the laws, and to feast. He also claims that the

Similar to Bealtaine, bonfires were lit on hilltops at Samhain and there were rituals involving them. By the early modern era, they were most common in parts of the

Similar to Bealtaine, bonfires were lit on hilltops at Samhain and there were rituals involving them. By the early modern era, they were most common in parts of the

Chapter 63, Part 1: On the Fire-festivals in general

They may also have served to symbolically "burn up and destroy all harmful influences". Accounts from the 18th and 19th centuries suggest that the fires (as well as their smoke and ashes) were deemed to have protective and cleansing powers.Hutton, pp. 365–68 In 19th-century

The bonfires were used in

The bonfires were used in  At household festivities throughout the Gaelic regions and Wales, there were many rituals intended to divine the future of those gathered, especially with regard to death and marriage. Apples and hazelnuts were often used in these divination rituals and games. In

At household festivities throughout the Gaelic regions and Wales, there were many rituals intended to divine the future of those gathered, especially with regard to death and marriage. Apples and hazelnuts were often used in these divination rituals and games. In

People also took special care not to offend the ''aos sí'' and sought to ward-off any who were out to cause mischief. They stayed near to home or, if forced to walk in the darkness, turned their clothing inside-out or carried iron or salt to keep them at bay. In southern Ireland, it was customary on Samhain to weave a small cross of sticks and straw called a 'parshell' or 'parshall', which was similar to the Brigid's cross and

People also took special care not to offend the ''aos sí'' and sought to ward-off any who were out to cause mischief. They stayed near to home or, if forced to walk in the darkness, turned their clothing inside-out or carried iron or salt to keep them at bay. In southern Ireland, it was customary on Samhain to weave a small cross of sticks and straw called a 'parshell' or 'parshall', which was similar to the Brigid's cross and

Chapter 10: The Cult of the Dead

The souls of the dead were thought to revisit their homes seeking hospitality. Places were set at the dinner table and by the fire to welcome them.McNeill, ''The Silver Bough, Volume 3'', pp. 11–46 The belief that the souls of the dead return home on one night of the year and must be appeased seems to have ancient origins and is found in many cultures throughout the world.Miles, Clement A. (1912). ''Christmas in Ritual and Tradition''

James Frazer suggests "It was perhaps a natural thought that the approach of winter should drive the poor, shivering, hungry ghosts from the bare fields and the leafless woodlands to the shelter of the cottage".Frazer, James George (1922). '' The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion''

Chapter 62, Part 6: The Hallowe'en Fires

However, the souls of thankful kin could return to bestow blessings just as easily as that of a wronged person could return to wreak revenge.

In some areas, mumming and guising was a part of Samhain. It was first recorded in 16th century Scotland and later in parts of Ireland, Mann and Wales.Hutton, pp. 380–82 It involved people going from house to house in costume (or in disguise), usually reciting songs or verses in exchange for food. It may have evolved from a tradition whereby people impersonated the ''aos sí'', or the souls of the dead, and received offerings on their behalf. Impersonating these spirits or souls was also believed to protect oneself from them. S. V. Peddle suggests the guisers "personify the old spirits of the winter, who demanded reward in exchange for good fortune". McNeill suggests that the ancient festival included people in masks or costumes representing these spirits and that the modern custom came from this.McNeill, F. Marian. ''Hallowe'en: its origin, rites and ceremonies in the Scottish tradition''. Albyn Press, 1970. pp. 29–31 In Ireland, costumes were sometimes worn by those who went about before nightfall collecting for a Samhain feast.

In Scotland, young men went house-to-house with masked, veiled, painted or blackened faces, often threatening to do mischief if they were not welcomed. This was common in the 16th century in the Scottish countryside and persisted into the 20th.Bannatyne, Lesley Pratt (1998

In some areas, mumming and guising was a part of Samhain. It was first recorded in 16th century Scotland and later in parts of Ireland, Mann and Wales.Hutton, pp. 380–82 It involved people going from house to house in costume (or in disguise), usually reciting songs or verses in exchange for food. It may have evolved from a tradition whereby people impersonated the ''aos sí'', or the souls of the dead, and received offerings on their behalf. Impersonating these spirits or souls was also believed to protect oneself from them. S. V. Peddle suggests the guisers "personify the old spirits of the winter, who demanded reward in exchange for good fortune". McNeill suggests that the ancient festival included people in masks or costumes representing these spirits and that the modern custom came from this.McNeill, F. Marian. ''Hallowe'en: its origin, rites and ceremonies in the Scottish tradition''. Albyn Press, 1970. pp. 29–31 In Ireland, costumes were sometimes worn by those who went about before nightfall collecting for a Samhain feast.

In Scotland, young men went house-to-house with masked, veiled, painted or blackened faces, often threatening to do mischief if they were not welcomed. This was common in the 16th century in the Scottish countryside and persisted into the 20th.Bannatyne, Lesley Pratt (1998

Forerunners to Halloween

Pelican Publishing Company. p. 44 It is suggested that the blackened faces comes from using the bonfire's ashes for protection. In Ireland in the late 18th century, peasants carrying sticks went house-to-house on Samhain collecting food for the feast. Hutton writes: "When imitating malignant spirits it was a very short step from guising to playing pranks". Playing pranks at Samhain is recorded in the Scottish Highlands as far back as 1736 and was also common in Ireland, which led to Samhain being nicknamed "Mischief Night" in some parts. Wearing costumes at Halloween spread to England in the 20th century, as did the custom of playing pranks, though there had been mumming at other festivals. At the time of mass transatlantic Irish and Scottish immigration, which popularised Halloween in North America, Halloween in Ireland and Scotland had a strong tradition of guising and pranks.

Hutton writes: "When imitating malignant spirits it was a very short step from guising to playing pranks". Playing pranks at Samhain is recorded in the Scottish Highlands as far back as 1736 and was also common in Ireland, which led to Samhain being nicknamed "Mischief Night" in some parts. Wearing costumes at Halloween spread to England in the 20th century, as did the custom of playing pranks, though there had been mumming at other festivals. At the time of mass transatlantic Irish and Scottish immigration, which popularised Halloween in North America, Halloween in Ireland and Scotland had a strong tradition of guising and pranks.

Chapter 18: Festivals

and it was then eaten as part of a feast. This custom was common in parts of Ireland until the 19th century, and was found in some other parts of Europe. At New Year in the

In the Brittonic branch of the Celtic languages, Samhain is known as the "calends of winter". The Brittonic lands of Wales, Cornwall and

In the Brittonic branch of the Celtic languages, Samhain is known as the "calends of winter". The Brittonic lands of Wales, Cornwall and

Samhain and Samhain-based festivals are held by some Neopagans. As there are many kinds of Neopaganism, their Samhain celebrations can be very different despite the shared name. Some try to emulate the historic festival as much as possible. Other Neopagans base their celebrations on sundry unrelated sources, Gaelic culture being only one of the sources.Adler, Margot (1979, revised edition 2006) ''Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshippers, and Other Pagans in America Today''. Boston: Beacon Press . pp. 3, 243–99McColman, Carl (2003) ''Complete Idiot's Guide to Celtic Wisdom''. Alpha Press . pp. 12, 51 Folklorist Jenny Butler describes how Irish pagans pick some elements of historic Samhain celebrations and meld them with references to the Celtic past, making a new festival of Samhain that is inimitably part of neo-pagan culture.

Neopagans usually celebrate Samhain on 31 October–1 November in the Northern Hemisphere and 30 April–1 May in the Southern Hemisphere, beginning and ending at sundown. Some Neopagans celebrate it at the astronomical midpoint between the autumnal equinox and

Samhain and Samhain-based festivals are held by some Neopagans. As there are many kinds of Neopaganism, their Samhain celebrations can be very different despite the shared name. Some try to emulate the historic festival as much as possible. Other Neopagans base their celebrations on sundry unrelated sources, Gaelic culture being only one of the sources.Adler, Margot (1979, revised edition 2006) ''Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshippers, and Other Pagans in America Today''. Boston: Beacon Press . pp. 3, 243–99McColman, Carl (2003) ''Complete Idiot's Guide to Celtic Wisdom''. Alpha Press . pp. 12, 51 Folklorist Jenny Butler describes how Irish pagans pick some elements of historic Samhain celebrations and meld them with references to the Celtic past, making a new festival of Samhain that is inimitably part of neo-pagan culture.

Neopagans usually celebrate Samhain on 31 October–1 November in the Northern Hemisphere and 30 April–1 May in the Southern Hemisphere, beginning and ending at sundown. Some Neopagans celebrate it at the astronomical midpoint between the autumnal equinox and

Gaelic

Gaelic is an adjective that means "pertaining to the Gaels". As a noun it refers to the group of languages spoken by the Gaels, or to any one of the languages individually. Gaelic languages are spoken in Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man, an ...

festival on 1 NovemberÓ hÓgáin, Dáithí. ''Myth Legend and Romance: An Encyclopaedia of the Irish Folk Tradition''. Prentice Hall Press, 1991. p. 402. Quote: "The basic Irish division of the year was into two parts, the summer half beginning at Bealtaine (May 1st) and the winter half at Samhain (November 1st) ... The festivals properly began at sunset on the day before the actual date, evincing the Celtic tendency to regard the night as preceding the day". marking the end of the harvest

Harvesting is the process of gathering a ripe crop from the fields. Reaping is the cutting of grain or pulse for harvest, typically using a scythe, sickle, or reaper. On smaller farms with minimal mechanization, harvesting is the most l ...

season and beginning of winter or " darker half" of the year. Celebrations begin on the evening of 31 October, since the Celtic day began and ended at sunset. This is about halfway between the autumnal equinox and winter solstice

The winter solstice, also called the hibernal solstice, occurs when either of Earth's poles reaches its maximum tilt away from the Sun. This happens twice yearly, once in each hemisphere (Northern and Southern). For that hemisphere, the winter ...

. It is one of the four Gaelic seasonal festivals along with Imbolc, Beltaine and Lughnasa

Lughnasadh or Lughnasa ( , ) is a Gaelic festival marking the beginning of the harvest season. Historically, it was widely observed throughout Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man. In Modern Irish it is called , in gd, Lùnastal, and in gv, ...

. Historically it was widely observed throughout Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, Galicia

Galicia may refer to:

Geographic regions

* Galicia (Spain), a region and autonomous community of northwestern Spain

** Gallaecia, a Roman province

** The post-Roman Kingdom of the Suebi, also called the Kingdom of Gallaecia

** The medieval King ...

and the Isle of Man

)

, anthem = " O Land of Our Birth"

, image = Isle of Man by Sentinel-2.jpg

, image_map = Europe-Isle_of_Man.svg

, mapsize =

, map_alt = Location of the Isle of Man in Europe

, map_caption = Location of the Isle of Man (green)

in Europ ...

(where it is spelled Sauin). A similar festival was held by the Brittonic Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

*Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Foo ...

people, called '' Calan Gaeaf'' in Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the Bristol Channel to the south. It had a population in ...

, '' Kalan Gwav'' in Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a Historic counties of England, historic county and Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people ...

and ''Kalan Goañv'' in Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica during the period ...

.

Samhain is believed to have Celtic pagan

Ancient Celtic religion, commonly known as Celtic paganism, was the religion of the ancient Celtic peoples of Europe. Because the ancient Celts did not have writing, evidence about their religion is gleaned from archaeology, Greco-Roman accounts ...

origins and some Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several pa ...

passage tombs in Ireland are aligned with the sunrise at the time of Samhain. It is first mentioned in the earliest Irish literature, from the 9th century, and is associated with many important events in Irish mythology

Irish mythology is the body of myths native to the island of Ireland. It was originally oral tradition, passed down orally in the Prehistoric Ireland, prehistoric era, being part of ancient Celtic religion. Many myths were later Early Irish ...

. The early literature says Samhain was marked by great gatherings and feasts and was when the ancient burial mounds were open, which were seen as portals to the Otherworld

The concept of an otherworld in historical Indo-European religion is reconstructed in comparative mythology. Its name is a calque of ''orbis alius'' (Latin for "other Earth/world"), a term used by Lucan in his description of the Celtic Otherwor ...

. Some of the literature also associates Samhain with bonfires and sacrifices.

The festival was not recorded in detail until the early modern era. It was when cattle were brought down from the summer pastures and when livestock were slaughtered. As at Beltaine, special bonfire

A bonfire is a large and controlled outdoor fire, used either for informal disposal of burnable waste material or as part of a celebration.

Etymology

The earliest recorded uses of the word date back to the late 15th century, with the Catho ...

s were lit. These were deemed to have protective and cleansing powers and there were rituals involving them.O'Driscoll, Robert (ed.) (1981) ''The Celtic Consciousness'' New York: Braziller pp. 197–216: Ross, Anne "Material Culture, Myth and Folk Memory" (on modern survivals); pp. 217–42: Danaher, Kevin "Irish Folk Tradition and the Celtic Calendar" (on specific customs and rituals) Like Beltaine, Samhain was a liminal or threshold festival, when the boundary between this world and the Otherworld thinned, meaning the ''Aos Sí

' (; older form: ) is the Irish name for a supernatural race in Celtic mythology – spelled ''sìth'' by the Scots, but pronounced the same – comparable to fairies or elves. They are said to descend from either fallen angels or the ...

'' (the 'spirits' or 'fairies

A fairy (also fay, fae, fey, fair folk, or faerie) is a type of mythical being or legendary creature found in the folklore of multiple European cultures (including Celtic, Slavic, Germanic, English, and French folklore), a form of spirit, ...

') could more easily come into our world. Most scholars see the ''Aos Sí'' as remnants of pagan gods. At Samhain, they were appeased with offerings of food and drink, to ensure the people and their livestock survived the winter. The souls of dead kin were also thought to revisit their homes seeking hospitality, and a place was set at the table for them during a meal. Mumming and guising were part of the festival from at least the early modern era, whereby people went door-to-door in costume reciting verses in exchange for food. The costumes may have been a way of imitating, and disguising oneself from, the ''Aos Sí''. Divination

Divination (from Latin ''divinare'', 'to foresee, to foretell, to predict, to prophesy') is the attempt to gain insight into a question or situation by way of an occultic, standardized process or ritual. Used in various forms throughout history ...

was also a big part of the festival and often involved nuts and apples. In the late 19th century John Rhys

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Seco ...

and James Frazer suggested it had been the "Celtic New Year", but that is disputed.Hutton, Ronald (1996) ''Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain''. Oxford: Oxford University Press , p. 363.

In the 9th century the Western Church

Western Christianity is one of two sub-divisions of Christianity (Eastern Christianity being the other). Western Christianity is composed of the Latin Church and Western Protestantism, together with their offshoots such as the Old Catholic ...

endorsed 1 November as the date of All Saints' Day

All Saints' Day, also known as All Hallows' Day, the Feast of All Saints, the Feast of All Hallows, the Solemnity of All Saints, and Hallowmas, is a Christian solemnity celebrated in honour of all the saints of the church, whether they are k ...

, possibly due to the influence of Alcuin

Alcuin of York (; la, Flaccus Albinus Alcuinus; 735 – 19 May 804) – also called Ealhwine, Alhwin, or Alchoin – was a scholar, clergyman, poet, and teacher from York, Northumbria. He was born around 735 and became the student o ...

, and 2 November later became All Souls' Day. It is believed that over time Samhain and All Saints'/All Souls' influenced each other and eventually syncretised

Syncretism () is the practice of combining different beliefs and various schools of thought. Syncretism involves the merging or assimilation of several originally discrete traditions, especially in the theology and mythology of religion, th ...

into the modern Halloween

Halloween or Hallowe'en (less commonly known as Allhalloween, All Hallows' Eve, or All Saints' Eve) is a celebration observed in many countries on 31 October, the eve of the Western Christian feast of All Saints' Day. It begins the observan ...

. Most American Halloween traditions were inherited from Irish and Scottish immigrants.Brunvand, Jan (editor). ''American Folklore: An Encyclopedia''. Routledge, 2006. p.749 Folklorists have used the name 'Samhain' to refer to Gaelic 'Halloween' customs up until the 19th century. Hutton, Ronald. ''The Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain''. Oxford University Press, 1996. pp. 365–69

Since the later 20th century Celtic neopagans and Wicca

Wicca () is a modern Pagan religion. Scholars of religion categorise it as both a new religious movement and as part of the occultist stream of Western esotericism. It was developed in England during the first half of the 20th century and w ...

ns have observed Samhain, or something based on it, as a religious holiday.

Etymology

In Modern Irish andScottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic ( gd, Gàidhlig ), also known as Scots Gaelic and Gaelic, is a Goidelic language (in the Celtic branch of the Indo-European language family) native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a Goidelic language, Scottish Gaelic, as well as ...

the name is , while the traditional Manx Gaelic

Manx ( or , pronounced or ), also known as Manx Gaelic, is a Gaelic language of the insular Celtic branch of the Celtic language family, itself a branch of the Indo-European language family. Manx is the historical language of the Manx people ...

name is . It is usually written with the definite article (Irish), (Scottish Gaelic) and (Manx). Older forms of the word include the Scottish Gaelic spellings and . The Gaelic names for the month of November

November is the eleventh and penultimate month of the year in the Julian and Gregorian Calendars, the fourth and last of four months to have a length of 30 days and the fifth and last of five months to have a length of fewer than 31 days. Nov ...

are derived from ''Samhain''.

These names all come from the Middle Irish

Middle Irish, sometimes called Middle Gaelic ( ga, An Mheán-Ghaeilge, gd, Meadhan-Ghàidhlig), is the Goidelic language which was spoken in Ireland, most of Scotland and the Isle of Man from AD; it is therefore a contemporary of late Old Engl ...

''Samain'' or ''Samuin'' , the name for the festival held on 1 November in medieval Ireland, which has been traditionally derived from Proto-Indo-European

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European language family. Its proposed features have been derived by linguistic reconstruction from documented Indo-European languages. No direct record of Proto-Indo ...

(PIE) ''*semo-'' ('summer'). As John T. Koch

John T. Koch is an American academic, historian and linguist who specializes in Celtic studies, especially prehistory and the early Middle Ages. He is the editor of the five-volume ''Celtic Culture. A Historical Encyclopedia'' (2006, ABC Clio). He ...

notes, however, it is unclear why a festival marking the beginning of winter should include the word for 'summer'. Joseph Vendryes also contends that it is unrelated because the Celtic summer ended in August. According to linguists Xavier Delamarre

Xavier Delamarre (; born 5 June 1954) is a French linguist, lexicographer, and diplomat. He is regarded as one of the world's foremost authorities on the Gaulish language.

Since 2019, he has been an associate researcher for the CNRS- PSL AOrOc ...

and Ranko Matasović, links to Proto-Celtic

Proto-Celtic, or Common Celtic, is the ancestral proto-language of all known Celtic languages, and a descendant of Proto-Indo-European. It is not attested in writing but has been partly reconstructed through the comparative method. Proto-Celt ...

*''samon''- ('summer') appear to be folk etymologies

Folk etymology (also known as popular etymology, analogical reformation, reanalysis, morphological reanalysis or etymological reinterpretation) is a change in a word or phrase resulting from the replacement of an unfamiliar form by a more famili ...

. According to them, Gaulish ''Samon''- and Middle Irish ''Samain'' should rather be derived from Proto-Celtic *''samoni''- (< PIE *''smHon''- 'reunion, assembly'), whose original meaning is best explained as 'assembly, east of thefirst month of the year' (cf. Old Irish

Old Irish, also called Old Gaelic ( sga, Goídelc, Ogham script: ᚌᚑᚔᚇᚓᚂᚉ; ga, Sean-Ghaeilge; gd, Seann-Ghàidhlig; gv, Shenn Yernish or ), is the oldest form of the Goidelic/Gaelic language for which there are extensive writte ...

-''samain'' 'swarm'), perhaps referring to an 'assembly of the living and the dead'.'

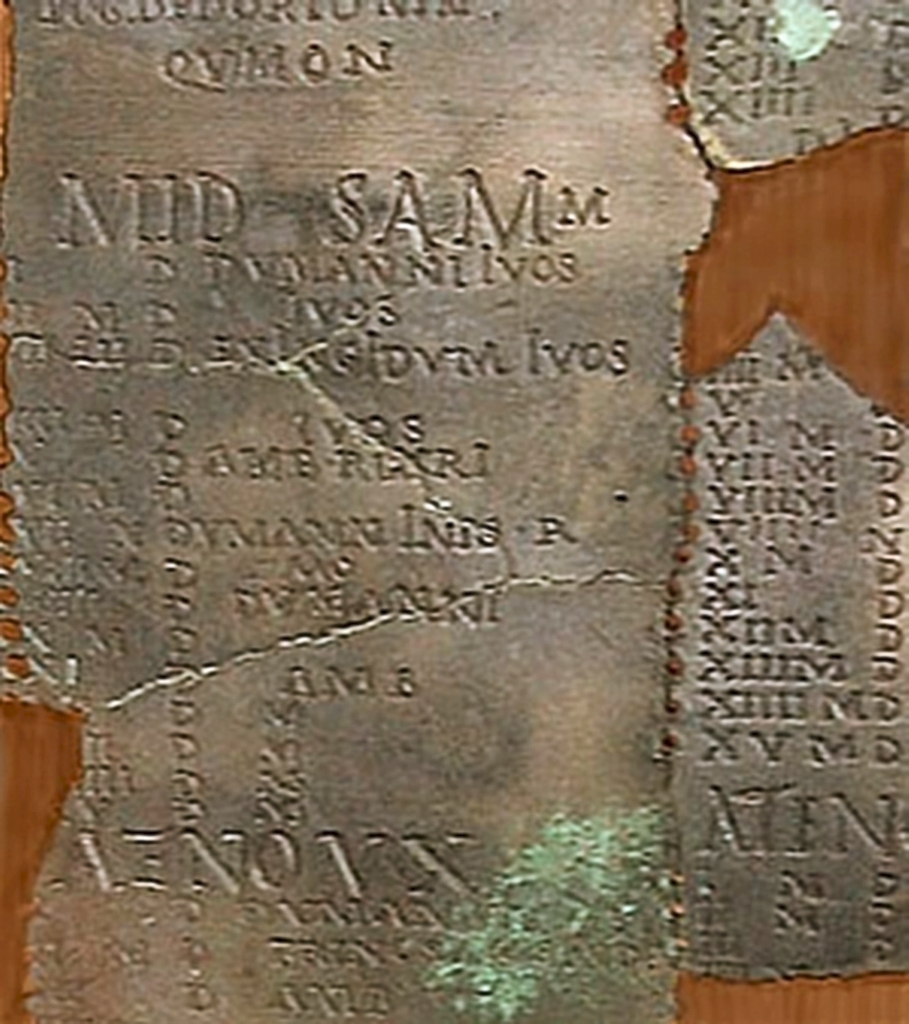

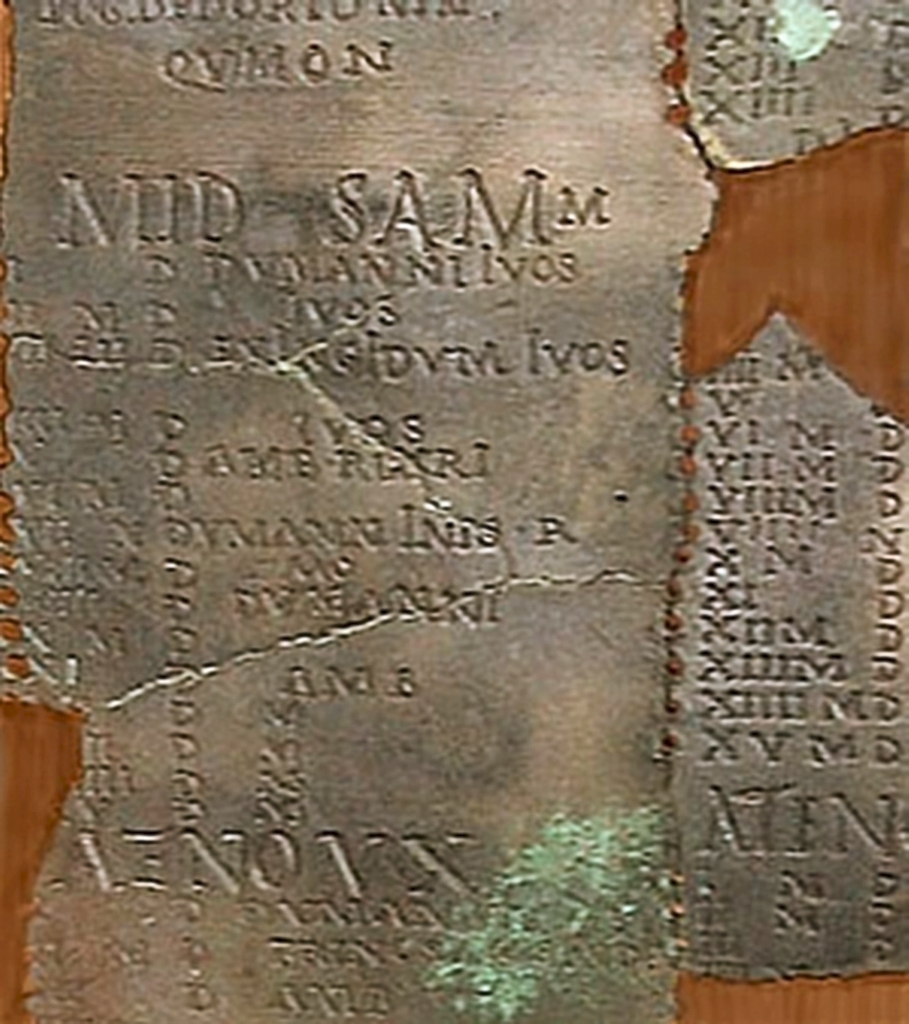

Coligny calendar

On

On Gaulish

Gaulish was an ancient Celtic language spoken in parts of Continental Europe before and during the period of the Roman Empire. In the narrow sense, Gaulish was the language of the Celts of Gaul (now France, Luxembourg, Belgium, most of Switze ...

Coligny calendar, dating from the 1st century BCE, the month name ''SAMONI'' is likely related to the word ''Samain''. A festival of some kind may have been held during the "three nights of ''Samoni''" (Gaulish ''TRINOX SAMONI''). The month name ''GIAMONI'', six months later, likely includes the word for "winter", but the starting point of the calendar is unclear.

Origins

''Samain'' or ''Samuin'' was the name of the festival (''feis'') marking the beginning of winter inGaelic Ireland

Gaelic Ireland ( ga, Éire Ghaelach) was the Gaelic political and social order, and associated culture, that existed in Ireland from the late prehistoric era until the early 17th century. It comprised the whole island before Anglo-Normans c ...

. It is attested in the earliest Old Irish literature, which dates from the 9th century onward. It was one of four Gaelic seasonal festivals: Samhain (~1 November), Imbolc (~1 February), Bealtaine (~1 May) and Lughnasa

Lughnasadh or Lughnasa ( , ) is a Gaelic festival marking the beginning of the harvest season. Historically, it was widely observed throughout Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man. In Modern Irish it is called , in gd, Lùnastal, and in gv, ...

(~1 August). Samhain and Bealtaine, at opposite sides of the year, are thought to have been the most important. Sir James George Frazer wrote in his 1890 book, '' The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion'', that 1 May and 1 November are of little importance to European crop-growers, but of great importance to herdsmen practising seasonal transhumance

Transhumance is a type of pastoralism or nomadism, a seasonal movement of livestock between fixed summer and winter pastures. In montane regions (''vertical transhumance''), it implies movement between higher pastures in summer and lower val ...

. It is at the beginning of summer that cattle are driven to the upland summer pastures and the beginning of winter that they are led back. Thus, Frazer suggests that halving the year at 1 May and 1 November dates from when the Celts were a mainly pastoral

A pastoral lifestyle is that of shepherds herding livestock around open areas of land according to seasons and the changing availability of water and pasture. It lends its name to a genre of literature, art, and music (pastorale) that depict ...

people, dependent on their herds.

Some Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several pa ...

passage tombs in Ireland are aligned with the sunrise around the times of Samhain and Imbolc. These include the Mound of the Hostages

The Mound of the Hostages () is an ancient passage tomb located in the Tara-Skryne Valley in County Meath, Leinster, Ireland.

The mound is a Neolithic structure, built between 3350 and 2800 BCE.http://spartanideas.msu.edu/2015/01/27/reuse-of-ce ...

(''Dumha na nGiall'') at the Hill of Tara, and Cairn L at Slieve na Calliagh

Slieve na Calliagh () are a range of hills and ancient burial site near Oldcastle, County Meath, Ireland. The summit is , the highest point in the county. On the hilltops are about twenty passage tombs, some decorated with rare megalithic art, ...

.

In Irish mythology

While Irish mythology was originally a spoken tradition, much of it was eventually written down in the Middle Ages by Christian

While Irish mythology was originally a spoken tradition, much of it was eventually written down in the Middle Ages by Christian monk

A monk (, from el, μοναχός, ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a person who practices religious asceticism by monastic living, either alone or with any number of other monks. A monk may be a person who decides to dedic ...

s. The tenth-century tale ''Tochmarc Emire

''Tochmarc Emire'' ("The Wooing of Emer") is one of the stories in the Ulster Cycle of Irish mythology and one of the longest when it received its form in the second recension (below). It concerns the efforts of the hero Cú Chulainn to marry E ...

'' ('The Wooing of Emer') lists Samhain as the first of the four seasonal festivals of the year.Hutton, Ronald (1996) ''Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain''. Oxford: Oxford University Press , p. 361. The literature says a peace would be declared and there were great gatherings where they held meetings, feasted, drank alcohol,Monaghan, p. 407 and held contests. These gatherings are a popular setting for early Irish tales. The tale ''Echtra Cormaic

''Echtra Cormaic'' or ''Echtra Cormaic i Tir Tairngiri'' (''Cormac's Adventure in the Land of Promise'') is a tale in Irish mythology which recounts the journey of the high-king Cormac mac Airt to the Land of Promise resided by the sea-god Man ...

'' ('Cormac's Adventure') says that the Feast of Tara was held every seventh Samhain, hosted by the High King of Ireland

High King of Ireland ( ga, Ardrí na hÉireann ) was a royal title in Gaelic Ireland held by those who had, or who are claimed to have had, lordship over all of Ireland. The title was held by historical kings and later sometimes assigned an ...

, during which new laws and duties were ordained; anyone who broke the laws established during this time would be banished.

According to Irish mythology, Samhain (like Bealtaine) was a time when the 'doorways' to the Otherworld

The concept of an otherworld in historical Indo-European religion is reconstructed in comparative mythology. Its name is a calque of ''orbis alius'' (Latin for "other Earth/world"), a term used by Lucan in his description of the Celtic Otherwor ...

opened, allowing supernatural beings and the souls of the dead to come into our world; while Bealtaine was a summer festival for the living, Samhain "was essentially a festival for the dead". '' The Boyhood Deeds of Fionn'' says that the '' sídhe'' (fairy mounds or portals to the Otherworld) "were always open at Samhain". Each year the fire-breather Aillen

Aillen or Áillen is an incendiary being in Irish mythology. He played the harp and was known to sing beautiful songs.

Character

Called "the burner", he is a member of the Tuatha Dé Danann who resides in Mag Mell, the underworld.

Deeds

Acc ...

emerges from the Otherworld and burns down the palace of Tara during the Samhain festival after lulling everyone to sleep with his music.

One Samhain, the young Fionn mac Cumhaill is able to stay awake and slays Aillen with a magical spear, for which he is made leader of the fianna

''Fianna'' ( , ; singular ''Fian''; gd, Fèinne ) were small warrior-hunter bands in Gaelic Ireland during the Iron Age and early Middle Ages. A ''fian'' was made up of freeborn young males, often aristocrats, "who had left fosterage but had ...

. In a similar tale, one Samhain the Otherworld being Cúldubh comes out of the burial mound on Slievenamon

Slievenamon or Slievenaman ( ga, Sliabh na mBan , "mountain of the women") is a mountain with a height of in County Tipperary, Ireland. It rises from a plain that includes the towns of Fethard, Clonmel and Carrick-on-Suir. The mountain is stee ...

and snatches a roast pig. Fionn kills Cúldubh with a spear throw as he re-enters the mound. Fionn's thumb is caught between the door and the post as it shuts, and he puts it in his mouth to ease the pain. As his thumb had been inside the Otherworld, Fionn is bestowed with great wisdom. This may refer to gaining knowledge from the ancestors. '' Acallam na Senórach'' ('Colloquy of the Elders') tells how three female werewolves

In folklore, a werewolf (), or occasionally lycanthrope (; ; uk, Вовкулака, Vovkulaka), is an individual that can shapeshift into a wolf (or, especially in modern film, a therianthropic hybrid wolf-like creature), either purposely ...

emerge from the cave of Cruachan (an Otherworld portal) each Samhain and kill livestock. When Cas Corach

In Irish mythology, Cas Corach was a hero who helped Caílte mac Rónáin kill three werewolf-like creatures, the daughters of Airitech who would come out of the Cave of Cruachan every year around Samhain and destroy sheep. The she-wolves li ...

plays his harp, they take on human form, and the fianna

''Fianna'' ( , ; singular ''Fian''; gd, Fèinne ) were small warrior-hunter bands in Gaelic Ireland during the Iron Age and early Middle Ages. A ''fian'' was made up of freeborn young males, often aristocrats, "who had left fosterage but had ...

warrior Caílte then slays them with a spear.

Some tales suggest that offerings or sacrifices were made at Samhain. In the ''Lebor Gabála Érenn

''Lebor Gabála Érenn'' (literally "The Book of the Taking of Ireland"), known in English as ''The Book of Invasions'', is a collection of poems and prose narratives in the Irish language intended to be a history of Ireland and the Irish fro ...

'' (or 'Book of Invasions'), each Samhain the people of Nemed had to give two-thirds of their children, their corn and their milk to the monstrous Fomorians. The Fomorians seem to represent the harmful or destructive powers of nature; personifications of chaos, darkness, death, blight and drought. This tribute

A tribute (; from Latin ''tributum'', "contribution") is wealth, often in kind, that a party gives to another as a sign of submission, allegiance or respect. Various ancient states exacted tribute from the rulers of land which the state conq ...

paid by Nemed's people may represent a "sacrifice offered at the beginning of winter, when the powers of darkness and blight are in the ascendant". According to the later '' Dindsenchas'' and the ''Annals of the Four Masters

The ''Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland'' ( ga, Annála Ríoghachta Éireann) or the ''Annals of the Four Masters'' (''Annála na gCeithre Máistrí'') are chronicles of medieval Irish history. The entries span from the Deluge, dated as 2,24 ...

''—which were written by Christian monks—Samhain in ancient Ireland was associated with a god or idol called Crom Cruach. The texts claim that a first-born child would be sacrificed at the stone idol of Crom Cruach in Magh Slécht. They say that King Tigernmas

Tigernmas, son of Follach, son of Ethriel, a descendant of Érimón, was, according to medieval Irish legend and historical traditions, an early High King of Ireland.

According to the ''Lebor Gabála Érenn'' he became king when he overthrew his ...

, and three-fourths of his people, died while worshiping Crom Cruach there one Samhain.

The legendary kings Diarmait mac Cerbaill and Muirchertach mac Ercae each die a threefold death on Samhain, which involves wounding, burning and drowning, and of which they are forewarned. In the tale '' Togail Bruidne Dá Derga'' ('The Destruction of Dá Derga's Hostel'), king

The legendary kings Diarmait mac Cerbaill and Muirchertach mac Ercae each die a threefold death on Samhain, which involves wounding, burning and drowning, and of which they are forewarned. In the tale '' Togail Bruidne Dá Derga'' ('The Destruction of Dá Derga's Hostel'), king Conaire Mór

Conaire Mór (the great), son of Eterscél, was, according to medieval Irish legend and historical tradition, a High King of Ireland. His mother was Mess Búachalla, who was either the daughter of Eochu Feidlech and Étaín, or of Eochu Airem and ...

also meets his death on Samhain after breaking his '' geasa'' (prohibitions or taboos). He is warned of his impending doom by three undead horsemen who are messengers of Donn, god of the dead. ''The Boyhood Deeds of Fionn'' tells how each Samhain the men of Ireland went to woo a beautiful maiden who lives in the fairy mound on Brí Eile (Croghan Hill). It says that each year someone would be killed "to mark the occasion", by persons unknown. Some academics suggest that these tales recall human sacrifice, and argue that several ancient Irish bog bodies (such as Old Croghan Man) appear to have been kings who were ritually killed, some of them around the time of Samhain.

In the '' Echtra Neraí'' ('The Adventure of Nera'), King Ailill of Connacht

Connacht ( ; ga, Connachta or ), is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the west of Ireland. Until the ninth century it consisted of several independent major Gaelic kingdoms ( Uí Fiachrach, Uí Briúin, Uí Maine, Conmhaícne, and ...

sets his retinue

A retinue is a body of persons "retained" in the service of a noble, royal personage, or dignitary; a ''suite'' (French "what follows") of retainers.

Etymology

The word, recorded in English since circa 1375, stems from Old French ''retenue'', ...

a test of bravery on Samhain night. He offers a prize to whoever can make it to a gallows

A gallows (or scaffold) is a frame or elevated beam, typically wooden, from which objects can be suspended (i.e., hung) or "weighed". Gallows were thus widely used to suspend public weighing scales for large and heavy objects such as sacks ...

and tie a band around a hanged man's ankle. Each challenger is thwarted by demons and runs back to the king's hall in fear. However, Nera succeeds, and the dead man then asks for a drink. Nera carries him on his back and they stop at three houses. They enter the third, where the dead man drinks and spits it on the householders, killing them. Returning, Nera sees a fairy host burning the king's hall and slaughtering those inside. He follows the host through a portal into the Otherworld. Nera learns that what he saw was only a vision of what will happen the next Samhain unless something is done. He is able to return to the hall and warns the king.

The tale ''Aided Chrimthainn maic Fidaig'' ('The Killing of Crimthann mac Fidaig') tells how Mongfind

Mongfind (or Mongfhionn in modern Irish)—meaning "fair hair" or "white hair"—is a figure from Irish legend. She is said to have been the wife, of apparent Munster origins, of the legendary High King Eochaid Mugmedón and mother of his eldes ...

kills her brother, king Crimthann of Munster, so that one of her sons might become king. Mongfind offers Crimthann a poisoned drink at a feast, but he asks her to drink from it first. Having no other choice but to drink the poison, she dies on Samhain eve. The Middle Irish

Middle Irish, sometimes called Middle Gaelic ( ga, An Mheán-Ghaeilge, gd, Meadhan-Ghàidhlig), is the Goidelic language which was spoken in Ireland, most of Scotland and the Isle of Man from AD; it is therefore a contemporary of late Old Engl ...

writer notes that Samhain is also called ''Féile Moingfhinne'' (the Festival of Mongfind or Mongfhionn), and that "women and the rabble make petitions to her" at Samhain.

Many other events in Irish mythology happen or begin on Samhain. The invasion of Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kin ...

that makes up the main action of the ''Táin Bó Cúailnge

(Modern ; "the driving-off of the cows of Cooley"), commonly known as ''The Táin'' or less commonly as ''The Cattle Raid of Cooley'', is an epic from Irish mythology. It is often called "The Irish Iliad", although like most other early Iri ...

'' ('Cattle Raid of Cooley') begins on Samhain. As cattle-raiding typically was a summer activity, the invasion during this off-season surprised the Ulstermen. The '' Second Battle of Magh Tuireadh'' also begins on Samhain. The Morrígan

The Morrígan or Mórrígan, also known as Morrígu, is a figure from Irish mythology. The name is Mór-Ríoghain in Modern Irish, and it has been translated as "great queen" or "phantom queen".

The Morrígan is mainly associated with war an ...

and The Dagda

The Dagda (Old Irish: ''In Dagda,'' ga, An Daghdha, ) is an important god in Irish mythology. One of the Tuatha Dé Danann, the Dagda is portrayed as a father-figure, king, and druid.Koch, John T. ''Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia ...

meet and have sex before the battle against the Fomorians; in this way the Morrígan acts as a sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

figure and gives the victory to the Dagda's people, the Tuatha Dé Danann

The Tuath(a) Dé Danann (, meaning "the folk of the goddess Danu"), also known by the earlier name Tuath Dé ("tribe of the gods"), are a supernatural race in Irish mythology. Many of them are thought to represent deities of pre-Christian Gae ...

. In ''Aislinge Óengusa'' ('The Dream of Óengus') it is when he and his bride-to-be switch from bird to human form, and in '' Tochmarc Étaíne'' ('The Wooing of Étaín') it is the day on which Óengus claims the kingship of Brú na Bóinne

(; 'Palace of the Boyne' or more properly 'Valley of the Boyne') or Boyne valley tombs, is an area in County Meath, Ireland, located in a bend of the River Boyne. It contains one of the world's most important prehistoric landscapes dating from ...

.

Several sites in Ireland are especially linked to Samhain. Each Samhain a host of otherworldly beings was said to emerge from the

Several sites in Ireland are especially linked to Samhain. Each Samhain a host of otherworldly beings was said to emerge from the Cave of Cruachan

A cave or cavern is a natural void in the ground, specifically a space large enough for a human to enter. Caves often form by the weathering of rock and often extend deep underground. The word ''cave'' can refer to smaller openings such as sea ...

in County Roscommon

"Steadfast Irish heart"

, image_map = Island of Ireland location map Roscommon.svg

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state, Country

, subdivision_name = Republic of Ireland, Ireland

, subdivision_type1 = Provinces of I ...

. The Hill of Ward (or Tlachtga) in County Meath

County Meath (; gle, Contae na Mí or simply ) is a county in the Eastern and Midland Region of Ireland, within the province of Leinster. It is bordered by Dublin to the southeast, Louth to the northeast, Kildare to the south, Offaly to the ...

is thought to have been the site of a great Samhain gathering and bonfire; the Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age ( Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age ( Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly ...

ringfort

Ringforts, ring forts or ring fortresses are circular fortified settlements that were mostly built during the Bronze Age up to about the year 1000. They are found in Northern Europe, especially in Ireland. There are also many in South Wale ...

is said to have been where the goddess or druid Tlachtga gave birth to triplets and where she later died.

In ''The Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain'' (1996), Ronald Hutton

Ronald Edmund Hutton (born 19 December 1953) is an English historian who specialises in Early Modern Britain, British folklore, pre-Christian religion and Contemporary Paganism. He is a professor at the University of Bristol, has written 14 ...

writes: "No doubt there were aganreligious observances as well, but none of the tales ever portrays any". The only historic reference to pagan religious rites is in the work of Geoffrey Keating (died 1644), but his source is unknown. Hutton says it may be that no religious rites are mentioned because, centuries after Christianization, the writers had no record of them. Hutton suggests Samhain may not have been ''particularly'' associated with the supernatural. He says that the gatherings of royalty and warriors on Samhain may simply have been an ideal setting for such tales, in the same way that many Arthurian tales are set at courtly gatherings at Christmas or Pentecost.Hutton, Ronald (1996) ''Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain.'' Oxford: Oxford University Press , p. 362.

Historic customs

Samhain was one of the four main festivals of the Gaelic calendar, marking the end of theharvest

Harvesting is the process of gathering a ripe crop from the fields. Reaping is the cutting of grain or pulse for harvest, typically using a scythe, sickle, or reaper. On smaller farms with minimal mechanization, harvesting is the most l ...

and beginning of winter. Samhain customs are mentioned in several medieval texts. In '' Serglige Con Culainn'' ('Cúchulainn's Sickbed'), it is said that the festival of the Ulaid

Ulaid (Old Irish, ) or Ulaidh ( Modern Irish, ) was a Gaelic over-kingdom in north-eastern Ireland during the Middle Ages made up of a confederation of dynastic groups. Alternative names include Ulidia, which is the Latin form of Ulaid, and in ...

at Samhain lasted a week: Samhain itself, and the three days before and after. It involved great gatherings at which they held meetings, feasted, drank alcohol, and held contests. The ''Togail Bruidne Dá Derga'' notes that bonfires were lit at Samhain and stones cast into the fires.The Destruction of Dá Derga's Hostel – Translated by Whitley StokesIt is mentioned in Geoffrey Keating's '' Foras Feasa ar Éirinn'', which was written in the early 1600s but draws on earlier medieval sources, some of which are unknown. He claims that the '' feis'' of Tara was held for a week every third Samhain, when the nobles and ollams of Ireland met to lay down and renew the laws, and to feast. He also claims that the

druid

A druid was a member of the high-ranking class in ancient Celtic cultures. Druids were religious leaders as well as legal authorities, adjudicators, lorekeepers, medical professionals and political advisors. Druids left no written accounts. Whi ...

s lit a sacred bonfire at Tlachtga and made sacrifices to the gods, sometimes by burning their sacrifices. He adds that all other fires were doused and then re-lit from this bonfire.

Ritual bonfires

Scottish Highlands

The Highlands ( sco, the Hielands; gd, a’ Ghàidhealtachd , 'the place of the Gaels') is a historical region of Scotland. Culturally, the Highlands and the Lowlands diverged from the Late Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowland S ...

, on the Isle of Man, in north and mid Wales, and in parts of Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kin ...

.Hutton, p. 369 F. Marian McNeill says that a force-fire (or need-fire) was the traditional way of lighting them, but notes that this method gradually died out. Likewise, only certain kinds of wood were traditionally used, but later records show that many kinds of flammable material were burnt. Campbell, John Gregorson (1900, 1902, 2005) ''The Gaelic Otherworld''. Edited by Ronald Black. Edinburgh: Birlinn Ltd. pp. 559–62 It is suggested that the fires were a kind of imitative or sympathetic magic—they mimicked the Sun, helping the "powers of growth" and holding back the decay and darkness of winter.Frazer, James George (1922). '' The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion''Chapter 63, Part 1: On the Fire-festivals in general

They may also have served to symbolically "burn up and destroy all harmful influences". Accounts from the 18th and 19th centuries suggest that the fires (as well as their smoke and ashes) were deemed to have protective and cleansing powers.Hutton, pp. 365–68 In 19th-century

Moray

Moray () gd, Moireibh or ') is one of the 32 local government council areas of Scotland. It lies in the north-east of the country, with a coastline on the Moray Firth, and borders the council areas of Aberdeenshire and Highland (council area), ...

, boys asked for bonfire fuel from each house in the village. When the fire was lit, "one after another of the youths laid himself down on the ground as near to the fire as possible so as not to be burned, and in such a position as to let the smoke roll over him. The others ran through the smoke and jumped over him". When the bonfire burnt down, they scattered the ashes, vying with each other who should scatter them most. In some areas, two bonfires would be built side by side, and the people—sometimes with their livestock—would walk between them as a cleansing ritual. The bones of slaughtered cattle were said to have been cast upon bonfires. In the Gaelic world, cattle were the main form of wealth and were the center of agricultural and pastoral life.

People also took flames from the bonfire back to their homes. During the 19th century in parts of Scotland, torches of burning fir or turf were carried sunwise

In Scottish folklore, sunwise, deosil or sunward (clockwise) was considered the “prosperous course”, turning from east to west in the direction of the sun. The opposite course, anticlockwise, was known as '' widdershins'' ( Lowland Scots), or ...

around homes and fields to protect them. In some places, people doused their hearth fires on Samhain night. Each family then solemnly re-lit its hearth from the communal bonfire, thus bonding the community together. The 17th century writer Geoffrey Keating claimed that this was an ancient tradition, instituted by the druids. Dousing the old fire and bringing in the new may have been a way of banishing evil, which was part of New Year festivals in many countries.

Divination

divination

Divination (from Latin ''divinare'', 'to foresee, to foretell, to predict, to prophesy') is the attempt to gain insight into a question or situation by way of an occultic, standardized process or ritual. Used in various forms throughout history ...

rituals, although not all divination involved fire. In 18th-century Ochtertyre, a ring of stones—one for each person—was laid round the fire, perhaps on a layer of ash. Everyone then ran round it with a torch, "exulting". In the morning, the stones were examined and if any were mislaid it was said that the person it represented would not live out the year. A similar custom was observed in northern Wales and in Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica during the period ...

. James Frazer suggests this may come from "an older custom of actually burning them" (i.e. human sacrifice

Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease gods, a human ruler, an authoritative/priestly figure or spirits of dead ancestors or as a retainer sacrifice, wherei ...

) or it may have always been symbolic. Divination has likely been a part of the festival since ancient times, and it has survived in some rural areas.

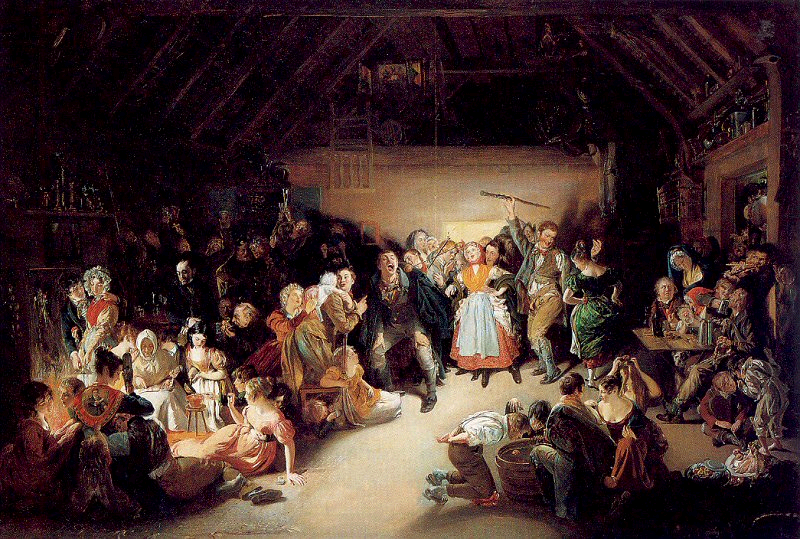

At household festivities throughout the Gaelic regions and Wales, there were many rituals intended to divine the future of those gathered, especially with regard to death and marriage. Apples and hazelnuts were often used in these divination rituals and games. In

At household festivities throughout the Gaelic regions and Wales, there were many rituals intended to divine the future of those gathered, especially with regard to death and marriage. Apples and hazelnuts were often used in these divination rituals and games. In Celtic mythology

Celtic mythology is the body of myths belonging to the Celtic peoples.Cunliffe, Barry, (1997) ''The Ancient Celts''. Oxford, Oxford University Press , pp. 183 (religion), 202, 204–8. Like other Iron Age Europeans, Celtic peoples followed ...

, apples were strongly associated with the Otherworld

The concept of an otherworld in historical Indo-European religion is reconstructed in comparative mythology. Its name is a calque of ''orbis alius'' (Latin for "other Earth/world"), a term used by Lucan in his description of the Celtic Otherwor ...

and immortality, while hazelnuts were associated with divine wisdom. One of the most common games was apple bobbing

Apple bobbing, also known as bobbing for apples, is a game often played on Halloween. The game is played by filling a tub or a large basin with water and putting apples in the water. Because apples are less dense than water, they will float at the ...

. Another involved hanging a small wooden rod from the ceiling at head height, with a lit candle on one end and an apple hanging from the other. The rod was spun round and everyone took turns to try to catch the apple with their teeth. Apples were peeled in one long strip, the peel tossed over the shoulder, and its shape was said to form the first letter of the future spouse's name.

Two hazelnuts were roasted near a fire; one named for the person roasting them and the other for the person they desired. If the nuts jumped away from the heat, it was a bad sign, but if the nuts roasted quietly it foretold a good match. Items were hidden in food—usually a cake, barmbrack, cranachan, champ or sowans

Sowans or sowens ( gd, sùghan), also called virpa, is a Scottish dish made using the starch remaining on the inner husks of oats after milling. The husks are allowed to soak in water and ferment for a few days. The liquor is strained off and al ...

—and portions of it served out at random. A person's future was foretold by the item they happened to find; for example a ring meant marriage and a coin meant wealth.McNeill (1961), ''The Silver Bough Volume III'', p. 34 A salty oatmeal bannock was baked; the person ate it in three bites and then went to bed in silence without anything to drink. This was said to result in a dream in which their future spouse offers them a drink to quench their thirst. Egg whites were dropped in water, and the shapes foretold the number of future children. Children would also chase crows and divine some of these things from the number of birds or the direction they flew.

Spirits and souls

As noted earlier, Samhain was seen as a liminal time, when the boundary between this world and theOtherworld

The concept of an otherworld in historical Indo-European religion is reconstructed in comparative mythology. Its name is a calque of ''orbis alius'' (Latin for "other Earth/world"), a term used by Lucan in his description of the Celtic Otherwor ...

could more easily be crossed. This meant the ''aos sí

' (; older form: ) is the Irish name for a supernatural race in Celtic mythology – spelled ''sìth'' by the Scots, but pronounced the same – comparable to fairies or elves. They are said to descend from either fallen angels or the ...

'', the 'spirits' or 'fairies' (the little folk), could more easily come into our world. Many scholars see the ''aos sí'' as remnants of pagan gods and nature spirits. At Samhain, it was believed that the ''aos sí'' needed to be propitiated to ensure that the people and their livestock survived the winter. Offerings of food and drink would be left outside for the ''aos sí'', and portions of the crops might be left in the ground for them.

One custom—described a "blatant example" of a "pagan rite surviving into the Christian epoch"—was recorded in the Outer Hebrides

The Outer Hebrides () or Western Isles ( gd, Na h-Eileanan Siar or or ("islands of the strangers"); sco, Waster Isles), sometimes known as the Long Isle/Long Island ( gd, An t-Eilean Fada, links=no), is an island chain off the west coas ...

and Iona

Iona (; gd, Ì Chaluim Chille (IPA: �iːˈxaɫ̪ɯimˈçiʎə, sometimes simply ''Ì''; sco, Iona) is a small island in the Inner Hebrides, off the Ross of Mull on the western coast of Scotland. It is mainly known for Iona Abbey, though ther ...

in the 17th century. On the night of 31 October, fishermen and their families would go down to the shore. One man would wade into the water up to his waist, where he would pour out a cup of ale and ask ' Seonaidh' ('Shoney'), whom he called "god of the sea", to bestow on them a good catch. The custom was ended in the 1670s after a campaign by ministers, but the ceremony shifted to the springtime and survived until the early 19th century.

People also took special care not to offend the ''aos sí'' and sought to ward-off any who were out to cause mischief. They stayed near to home or, if forced to walk in the darkness, turned their clothing inside-out or carried iron or salt to keep them at bay. In southern Ireland, it was customary on Samhain to weave a small cross of sticks and straw called a 'parshell' or 'parshall', which was similar to the Brigid's cross and

People also took special care not to offend the ''aos sí'' and sought to ward-off any who were out to cause mischief. They stayed near to home or, if forced to walk in the darkness, turned their clothing inside-out or carried iron or salt to keep them at bay. In southern Ireland, it was customary on Samhain to weave a small cross of sticks and straw called a 'parshell' or 'parshall', which was similar to the Brigid's cross and God's eye

A God's eye (in Spanish, ''Ojo de Dios'') is a spiritual and votive object made by weaving a design out of yarn upon a wooden cross. Often several colors are used. They are commonly found in Mexican, Peruvian people and Latin American communitie ...

. It was fixed over the doorway to ward-off bad luck, sickness and witchcraft

Witchcraft traditionally means the use of magic or supernatural powers to harm others. A practitioner is a witch. In medieval and early modern Europe, where the term originated, accused witches were usually women who were believed to have ...

, and would be replaced each Samhain.

The dead were also honoured at Samhain. The beginning of winter may have been seen as the most fitting time to do so, as it was a time of 'dying' in nature.MacCulloch, John Arnott (1911). ''The Religion of the Ancient Celts''Chapter 10: The Cult of the Dead

The souls of the dead were thought to revisit their homes seeking hospitality. Places were set at the dinner table and by the fire to welcome them.McNeill, ''The Silver Bough, Volume 3'', pp. 11–46 The belief that the souls of the dead return home on one night of the year and must be appeased seems to have ancient origins and is found in many cultures throughout the world.Miles, Clement A. (1912). ''Christmas in Ritual and Tradition''

James Frazer suggests "It was perhaps a natural thought that the approach of winter should drive the poor, shivering, hungry ghosts from the bare fields and the leafless woodlands to the shelter of the cottage".Frazer, James George (1922). '' The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion''

Chapter 62, Part 6: The Hallowe'en Fires

However, the souls of thankful kin could return to bestow blessings just as easily as that of a wronged person could return to wreak revenge.

Mumming and guising

In some areas, mumming and guising was a part of Samhain. It was first recorded in 16th century Scotland and later in parts of Ireland, Mann and Wales.Hutton, pp. 380–82 It involved people going from house to house in costume (or in disguise), usually reciting songs or verses in exchange for food. It may have evolved from a tradition whereby people impersonated the ''aos sí'', or the souls of the dead, and received offerings on their behalf. Impersonating these spirits or souls was also believed to protect oneself from them. S. V. Peddle suggests the guisers "personify the old spirits of the winter, who demanded reward in exchange for good fortune". McNeill suggests that the ancient festival included people in masks or costumes representing these spirits and that the modern custom came from this.McNeill, F. Marian. ''Hallowe'en: its origin, rites and ceremonies in the Scottish tradition''. Albyn Press, 1970. pp. 29–31 In Ireland, costumes were sometimes worn by those who went about before nightfall collecting for a Samhain feast.

In Scotland, young men went house-to-house with masked, veiled, painted or blackened faces, often threatening to do mischief if they were not welcomed. This was common in the 16th century in the Scottish countryside and persisted into the 20th.Bannatyne, Lesley Pratt (1998

In some areas, mumming and guising was a part of Samhain. It was first recorded in 16th century Scotland and later in parts of Ireland, Mann and Wales.Hutton, pp. 380–82 It involved people going from house to house in costume (or in disguise), usually reciting songs or verses in exchange for food. It may have evolved from a tradition whereby people impersonated the ''aos sí'', or the souls of the dead, and received offerings on their behalf. Impersonating these spirits or souls was also believed to protect oneself from them. S. V. Peddle suggests the guisers "personify the old spirits of the winter, who demanded reward in exchange for good fortune". McNeill suggests that the ancient festival included people in masks or costumes representing these spirits and that the modern custom came from this.McNeill, F. Marian. ''Hallowe'en: its origin, rites and ceremonies in the Scottish tradition''. Albyn Press, 1970. pp. 29–31 In Ireland, costumes were sometimes worn by those who went about before nightfall collecting for a Samhain feast.

In Scotland, young men went house-to-house with masked, veiled, painted or blackened faces, often threatening to do mischief if they were not welcomed. This was common in the 16th century in the Scottish countryside and persisted into the 20th.Bannatyne, Lesley Pratt (1998Forerunners to Halloween

Pelican Publishing Company. p. 44 It is suggested that the blackened faces comes from using the bonfire's ashes for protection. In Ireland in the late 18th century, peasants carrying sticks went house-to-house on Samhain collecting food for the feast.

Charles Vallancey

General Charles Vallancey FRS (6 April 1731 – 8 August 1812) was a British military surveyor sent to Ireland. He remained there and became an authority on Irish antiquities. Some of his theories would be rejected today, but his drawings, fo ...

wrote that they demanded this in the name of St Colm Cille

Columba or Colmcille; gd, Calum Cille; gv, Colum Keeilley; non, Kolban or at least partly reinterpreted as (7 December 521 – 9 June 597 AD) was an Irish abbot and missionary evangelist credited with spreading Christianity in what is tod ...

, asking people to "lay aside the fatted calf, and to bring forth the black sheep

In the English language, black sheep is an idiom that describes a member of a group who is different from the rest, especially a family member who does not fit in. The term stems from sheep whose fleece is colored black rather than the more comm ...

". In parts of southern Ireland during the 19th century, the guisers included a hobby horse known as the ''Láir Bhán'' (white mare

A mare is an adult female horse or other equine. In most cases, a mare is a female horse over the age of three, and a filly is a female horse three and younger. In Thoroughbred horse racing, a mare is defined as a female horse more than fo ...

). A man covered in a white sheet and carrying a decorated horse skull would lead a group of youths, blowing on cow horns, from farm to farm. At each they recited verses, some of which "savoured strongly of paganism", and the farmer was expected to donate food. If the farmer donated food he could expect good fortune from the 'Muck Olla'; not doing so would bring misfortune. This is akin to the '' Mari Lwyd'' (grey mare) procession in Wales, which takes place at Midwinter

Midwinter is the middle of the winter. The term is attested in the early Germanic calendars.

Attestations

Midwinter is attested in the early Germanic calendars, where it appears to have been a specific day or a number of days during the winter ha ...

. In Wales the white horse

A white horse is born predominantly white and stays white throughout its life. A white horse has mostly pink skin under its hair coat, and may have brown, blue, or hazel eyes. "True white" horses, especially those that carry one of the dominant ...

is often seen as an omen of death. Elsewhere in Europe, costumes, mumming and hobby horses were part of other yearly festivals. However, in the Celtic-speaking regions they were "particularly appropriate to a night upon which supernatural beings were said to be abroad and could be imitated or warded off by human wanderers".

Hutton writes: "When imitating malignant spirits it was a very short step from guising to playing pranks". Playing pranks at Samhain is recorded in the Scottish Highlands as far back as 1736 and was also common in Ireland, which led to Samhain being nicknamed "Mischief Night" in some parts. Wearing costumes at Halloween spread to England in the 20th century, as did the custom of playing pranks, though there had been mumming at other festivals. At the time of mass transatlantic Irish and Scottish immigration, which popularised Halloween in North America, Halloween in Ireland and Scotland had a strong tradition of guising and pranks.

Hutton writes: "When imitating malignant spirits it was a very short step from guising to playing pranks". Playing pranks at Samhain is recorded in the Scottish Highlands as far back as 1736 and was also common in Ireland, which led to Samhain being nicknamed "Mischief Night" in some parts. Wearing costumes at Halloween spread to England in the 20th century, as did the custom of playing pranks, though there had been mumming at other festivals. At the time of mass transatlantic Irish and Scottish immigration, which popularised Halloween in North America, Halloween in Ireland and Scotland had a strong tradition of guising and pranks. Trick-or-treating

Trick-or-treating is a traditional Halloween custom for children and adults in some countries. During the evening of Halloween, on October 31, people in costumes travel from house to house, asking for treats with the phrase "trick or treat". The ...

may have come from the custom of going door-to-door collecting food for Samhain feasts, fuel for Samhain bonfires and/or offerings for the ''aos sí''. Alternatively, it may have come from the Allhallowtide custom of collecting soul cakes.

The "traditional illumination for guisers or pranksters abroad on the night in some places was provided by turnip

The turnip or white turnip ('' Brassica rapa'' subsp. ''rapa'') is a root vegetable commonly grown in temperate climates worldwide for its white, fleshy taproot. The word ''turnip'' is a compound of ''turn'' as in turned/rounded on a lathe and ...

s or mangel wurzels, hollowed out to act as lanterns and often carved with grotesque faces". They were also set on windowsills. By those who made them, the lanterns were variously said to represent the spirits or supernatural beings, Hutton, Ronald. ''The Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain''. Oxford University Press, 1996. pp. 382–83 or were used to ward off evil spirits.Palmer, Kingsley. ''Oral folk-tales of Wessex''. David & Charles, 1973. pp. 87–88 These were common in parts of Ireland and the Scottish Highlands in the 19th century. They were also found in Somerset

( en, All The People of Somerset)

, locator_map =

, coordinates =

, region = South West England

, established_date = Ancient

, established_by =

, preceded_by =

, origin =

, lord_lieutenant_office =Lord Lieutenant of Somerset

, lor ...

(see Punkie Night). In the 20th century they spread to other parts of Britain and became generally known as jack-o'-lantern

A jack-o'-lantern (or jack o'lantern) is a carved lantern, most commonly made from a pumpkin or a root vegetable such as a rutabaga or turnip. Jack-o'-lanterns are associated with the Halloween holiday. Its name comes from the reported phen ...

s.

Livestock

Traditionally, Samhain was a time to take stock of the herds and food supplies. Cattle were brought down to the winter pastures after six months in the higher summer pastures (seetranshumance

Transhumance is a type of pastoralism or nomadism, a seasonal movement of livestock between fixed summer and winter pastures. In montane regions (''vertical transhumance''), it implies movement between higher pastures in summer and lower val ...

). It was also the time to choose which animals would be slaughtered. This custom is still observed by many who farm and raise livestock.McNeill, F. Marian (1961, 1990) ''The Silver Bough'', Vol. 3. William MacLellan, Glasgow pp. 11–46 It is thought that some of the rituals associated with the slaughter have been transferred to other winter holidays. On St. Martin's Day (11 November) in Ireland, an animal—usually a rooster, goose

A goose ( : geese) is a bird of any of several waterfowl species in the family Anatidae. This group comprises the genera '' Anser'' (the grey geese and white geese) and ''Branta'' (the black geese). Some other birds, mostly related to the ...

or sheep—would be slaughtered and some of its blood sprinkled on the threshold of the house. It was offered to Saint Martin, who may have taken the place of a god or gods,MacCulloch, John Arnott (1911). ''The Religion of the Ancient Celts''Chapter 18: Festivals

and it was then eaten as part of a feast. This custom was common in parts of Ireland until the 19th century, and was found in some other parts of Europe. At New Year in the

Hebrides

The Hebrides (; gd, Innse Gall, ; non, Suðreyjar, "southern isles") are an archipelago off the west coast of the Scottish mainland. The islands fall into two main groups, based on their proximity to the mainland: the Inner and Outer Hebri ...

, a man dressed in a cowhide would circle the township sunwise

In Scottish folklore, sunwise, deosil or sunward (clockwise) was considered the “prosperous course”, turning from east to west in the direction of the sun. The opposite course, anticlockwise, was known as '' widdershins'' ( Lowland Scots), or ...

. A bit of the hide would be burnt and everyone would breathe in the smoke. These customs were meant to keep away bad luck, and similar customs were found in other Celtic regions.

Celtic Revival

During the late 19th and early 20th centuryCeltic Revival

The Celtic Revival (also referred to as the Celtic Twilight) is a variety of movements and trends in the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries that see a renewed interest in aspects of Celtic culture. Artists and writers drew on the traditions of Gae ...

, there was an upswell of interest in Samhain and the other Celtic festivals. Sir John Rhys

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Seco ...

put forth that it had been the "Celtic New Year". He inferred it from contemporary folklore in Ireland and Wales, which he felt was "full of Hallowe'en customs associated with new beginnings". He visited Mann and found that the Manx sometimes called 31 October "New Year's Night" or ''Hog-unnaa''. The ''Tochmarc Emire

''Tochmarc Emire'' ("The Wooing of Emer") is one of the stories in the Ulster Cycle of Irish mythology and one of the longest when it received its form in the second recension (below). It concerns the efforts of the hero Cú Chulainn to marry E ...

'', written in the Middle Ages, reckoned the year around the four festivals at the beginning of the seasons, and put Samhain at the beginning of those. However, Hutton says that the evidence for it being the Celtic or Gaelic New Year's Day is flimsy.Hutton, p. 363 Rhys's theory was popularised by Sir James George Frazer

Sir James George Frazer (; 1 January 1854 – 7 May 1941) was a Scottish social anthropologist and folklorist influential in the early stages of the modern studies of mythology and comparative religion.

Personal life

He was born on 1 Jan ...

, though at times he did acknowledge that the evidence is inconclusive. Frazer also put forth that Samhain had been the pagan Celtic festival of the dead and that it had been Christianized as All Saints and All Souls. Since then, Samhain has been popularly seen as the Celtic New Year and an ancient festival of the dead. The calendar of the Celtic League, for example, begins and ends at Samhain.

Related festivals

In the Brittonic branch of the Celtic languages, Samhain is known as the "calends of winter". The Brittonic lands of Wales, Cornwall and

In the Brittonic branch of the Celtic languages, Samhain is known as the "calends of winter". The Brittonic lands of Wales, Cornwall and Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica during the period ...

held festivals on 31 October similar to the Gaelic one. In Wales it is '' Calan Gaeaf'', in Cornwall it is Allantide or ''Kalan Gwav'' and in Brittany it is ''Kalan Goañv''.

The Manx celebrate Hop-tu-Naa on 31 October, which is a celebration of the original New Year's Eve. Traditionally, children carve turnips rather than pumpkins and carry them around the neighbourhood singing traditional songs relating to hop-tu-naa.

Allhallowtide

In 609, Pope Boniface IV endorsed 13 May as a holy day commemorating all Christian martyrs.Hutton, p. 364 By 800, there is evidence that churches in Ireland,Farmer, David. ''The Oxford Dictionary of Saints'' (Fifth Edition, Revised). Oxford University Press, 2011. p. 14Northumbria

la, Regnum Northanhymbrorum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of Northumbria

, common_name = Northumbria

, status = State

, status_text = Unified Anglian kingdom (before 876)North: Anglian kingdom (af ...

(England) and Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total l ...

(Germany) were holding a feast commemorating all saints on 1 November, which became All Saints' Day

All Saints' Day, also known as All Hallows' Day, the Feast of All Saints, the Feast of All Hallows, the Solemnity of All Saints, and Hallowmas, is a Christian solemnity celebrated in honour of all the saints of the church, whether they are k ...

. Alcuin

Alcuin of York (; la, Flaccus Albinus Alcuinus; 735 – 19 May 804) – also called Ealhwine, Alhwin, or Alchoin – was a scholar, clergyman, poet, and teacher from York, Northumbria. He was born around 735 and became the student o ...

of Northumbria commended his friend Arno of Salzburg, Bavaria for holding the feast on this date. James Frazer suggests this date was a Celtic idea (being the date of Samhain), while Ronald Hutton

Ronald Edmund Hutton (born 19 December 1953) is an English historian who specialises in Early Modern Britain, British folklore, pre-Christian religion and Contemporary Paganism. He is a professor at the University of Bristol, has written 14 ...

suggests it was a Germanic idea, writing that the Irish church commemorated all saints on 20 April. Some manuscripts of the Irish ''Martyrology of Tallaght