Salem witch trials on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Salem witch trials were a series of hearings and prosecutions of people accused of

The Salem witch trials were a series of hearings and prosecutions of people accused of

''UVA Today,'' 16 January 2016, accessed 28 April 2016

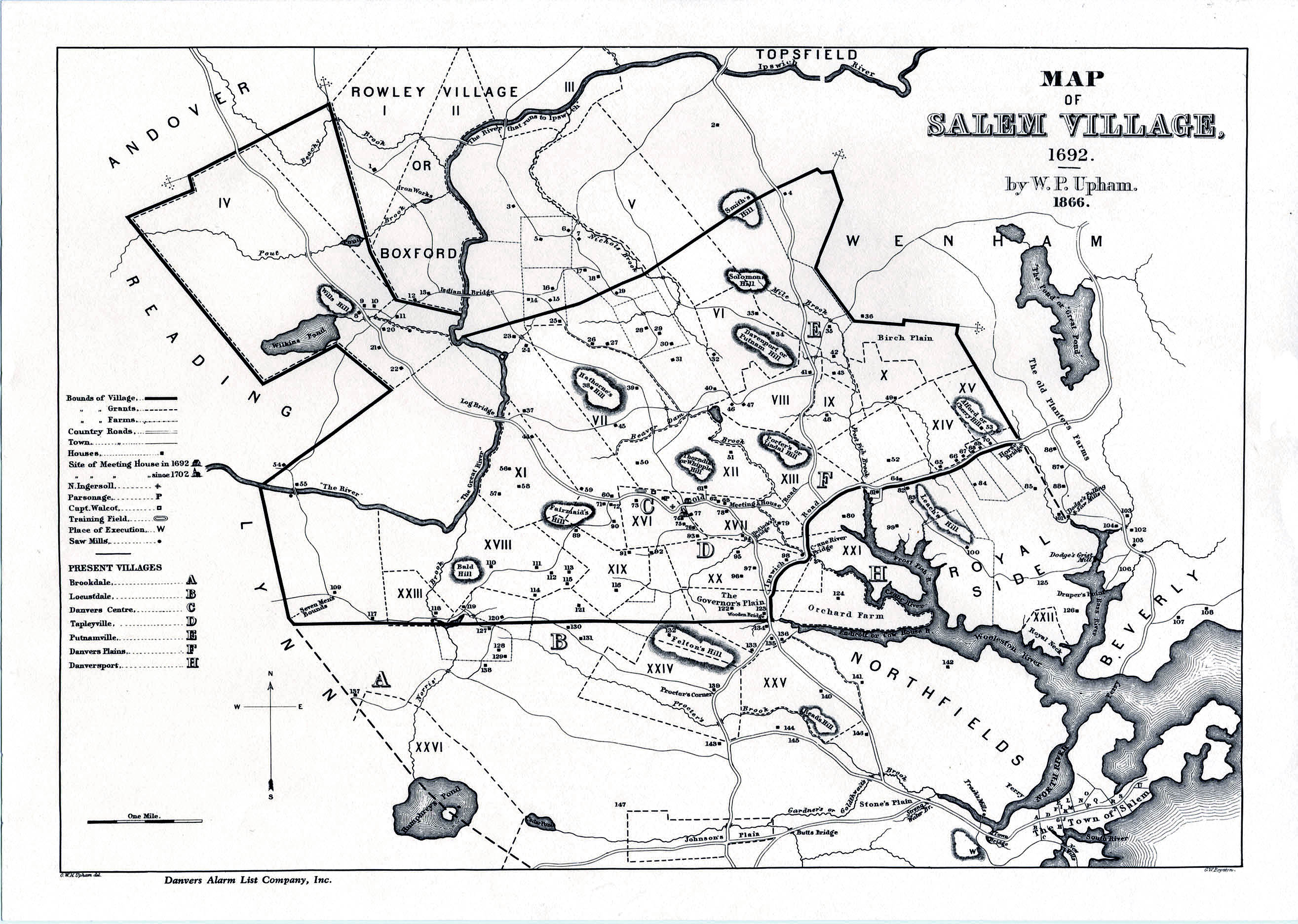

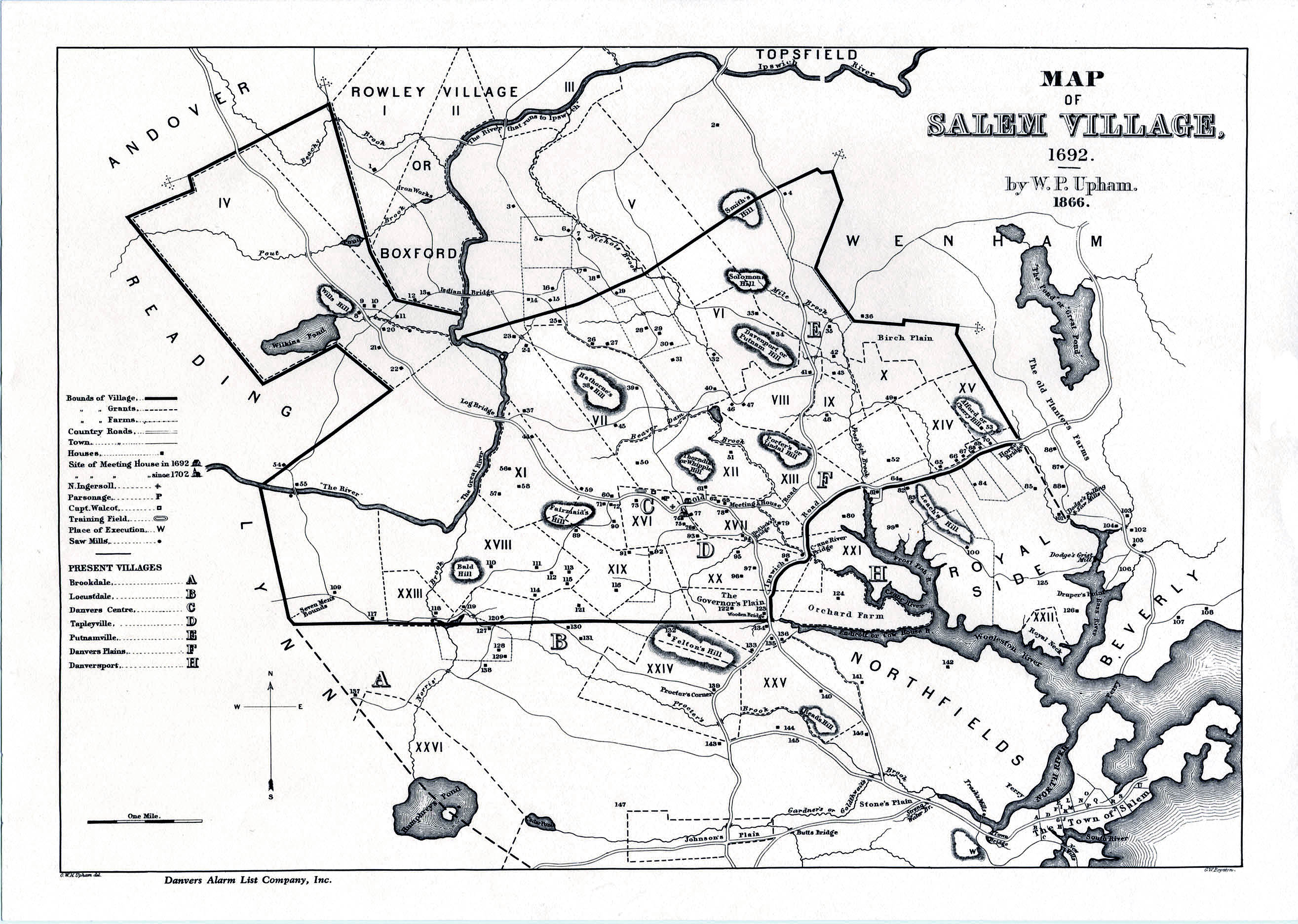

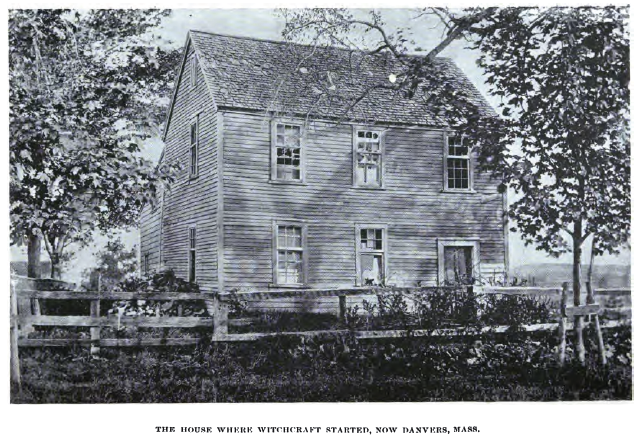

Salem Village (present-day

Salem Village (present-day

Prior to the constitutional turmoil of the 1680s, the Massachusetts government had been dominated by conservative

Prior to the constitutional turmoil of the 1680s, the Massachusetts government had been dominated by conservative

law.umkc.edu

; accessed January 18, 2019. Mather illustrates how the Goodwins' eldest child had been tempted by the devil and had stolen linen from the washerwoman Goody Glover.''Records of the Salem Witch-Hunt'', Rosenthal, et al., 2009, p. 15, n2 Glover, of Irish Catholic descent, was characterized as a disagreeable old woman and described by her husband as a witch; this may have been why she was accused of casting spells on the Goodwin children. After the event, four out of six Goodwin children began to have strange fits, or what some people referred to as "the disease of astonishment." The manifestations attributed to the disease quickly became associated with witchcraft. Symptoms included neck and back pains, tongues being drawn from their throats, and loud random outcries; other symptoms included having no control over their bodies such as becoming limber, flapping their arms like birds, or trying to harm others as well as themselves. These symptoms fuelled the craze of 1692.

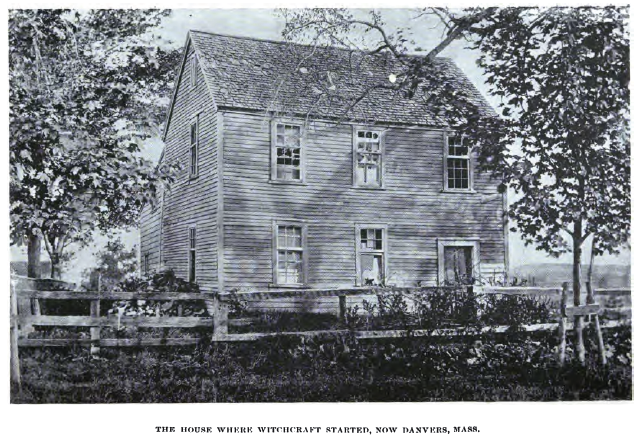

In Salem Village in February 1692, Betty Parris (age 9) and her cousin

In Salem Village in February 1692, Betty Parris (age 9) and her cousin

When

When

The Court of Oyer and Terminer convened in Salem Town on June 2, 1692, with William Stoughton, the new Lieutenant Governor, as Chief Magistrate, Thomas Newton as the Crown's Attorney prosecuting the cases, and Stephen Sewall as clerk. Bridget Bishop's case was the first brought to the grand jury, who endorsed all the indictments against her. Bishop was described as not living a Puritan lifestyle, for she wore black clothing and odd costumes, which was against the Puritan code. When she was examined before her trial, Bishop was asked about her coat, which had been awkwardly "cut or torn in two ways".

This, along with her "immoral" lifestyle, affirmed to the jury that Bishop was a witch. She went to trial the same day and was convicted. On June 3, the grand jury endorsed indictments against Rebecca Nurse and John Willard, but they did not go to trial immediately, for reasons which are unclear. Bishop was executed by hanging on June 10, 1692.

Immediately following this execution, the court adjourned for 20 days (until June 30) while it sought advice from New England's most influential ministers "upon the state of things as they then stood." Their collective response came back dated June 15 and composed by Cotton Mather:

Hutchinson sums the letter, "The two first and the last sections of this advice took away the force of all the others, and the prosecutions went on with more vigor than before." (Reprinting the letter years later in ''Magnalia'', Cotton Mather left out these "two first and the last" sections.) Major Nathaniel Saltonstall, Esq., resigned from the court on or about June 16, presumably dissatisfied with the letter and that it had not outright barred the admission of

The Court of Oyer and Terminer convened in Salem Town on June 2, 1692, with William Stoughton, the new Lieutenant Governor, as Chief Magistrate, Thomas Newton as the Crown's Attorney prosecuting the cases, and Stephen Sewall as clerk. Bridget Bishop's case was the first brought to the grand jury, who endorsed all the indictments against her. Bishop was described as not living a Puritan lifestyle, for she wore black clothing and odd costumes, which was against the Puritan code. When she was examined before her trial, Bishop was asked about her coat, which had been awkwardly "cut or torn in two ways".

This, along with her "immoral" lifestyle, affirmed to the jury that Bishop was a witch. She went to trial the same day and was convicted. On June 3, the grand jury endorsed indictments against Rebecca Nurse and John Willard, but they did not go to trial immediately, for reasons which are unclear. Bishop was executed by hanging on June 10, 1692.

Immediately following this execution, the court adjourned for 20 days (until June 30) while it sought advice from New England's most influential ministers "upon the state of things as they then stood." Their collective response came back dated June 15 and composed by Cotton Mather:

Hutchinson sums the letter, "The two first and the last sections of this advice took away the force of all the others, and the prosecutions went on with more vigor than before." (Reprinting the letter years later in ''Magnalia'', Cotton Mather left out these "two first and the last" sections.) Major Nathaniel Saltonstall, Esq., resigned from the court on or about June 16, presumably dissatisfied with the letter and that it had not outright barred the admission of

In September, grand juries indicted 18 more people. The grand jury failed to indict William Proctor, who was re-arrested on new charges. On September 19, 1692, Giles Corey refused to plead at trial, and was killed by ''

In September, grand juries indicted 18 more people. The grand jury failed to indict William Proctor, who was re-arrested on new charges. On September 19, 1692, Giles Corey refused to plead at trial, and was killed by ''

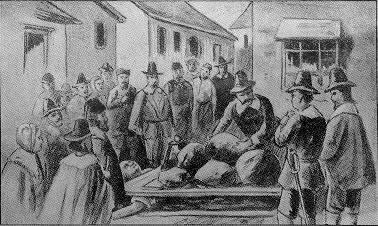

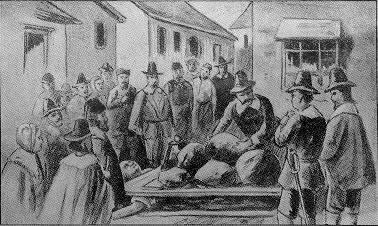

Giles Corey, an 81-year-old farmer from the southeast end of Salem (called Salem Farms), refused to enter a plea when he came to trial in September. The judges applied an archaic form of punishment called ''peine forte et dure,'' in which stones were piled on his chest until he could no longer breathe. After two days of ''peine fort et dure,'' Corey died without entering a plea.Boyer, p. 8. His refusal to plead is usually explained as a way of preventing his estate from being confiscated by the Crown, but, according to historian Chadwick Hansen, much of Corey's property had already been seized, and he had made a will in prison: "His death was a protest ... against the methods of the court". A contemporary critic of the trials,

Giles Corey, an 81-year-old farmer from the southeast end of Salem (called Salem Farms), refused to enter a plea when he came to trial in September. The judges applied an archaic form of punishment called ''peine forte et dure,'' in which stones were piled on his chest until he could no longer breathe. After two days of ''peine fort et dure,'' Corey died without entering a plea.Boyer, p. 8. His refusal to plead is usually explained as a way of preventing his estate from being confiscated by the Crown, but, according to historian Chadwick Hansen, much of Corey's property had already been seized, and he had made a will in prison: "His death was a protest ... against the methods of the court". A contemporary critic of the trials,

Much, but not all, of the evidence used against the accused was ''

Much, but not all, of the evidence used against the accused was ''

According to a March 27, 1692 entry by Parris in the ''Records of the Salem-Village Church'', a church member and close neighbor of Rev. Parris, Mary Sibley (aunt of

According to a March 27, 1692 entry by Parris in the ''Records of the Salem-Village Church'', a church member and close neighbor of Rev. Parris, Mary Sibley (aunt of

Church Records, pp. 10–12.

/ref> This may have been a superstitious attempt to ward off evil spirits. According to an account attributed to Deodat Lawson ("collected by Deodat Lawson") this happened around March 8, over a week after the first complaints had gone out and three women were arrested. Lawson's account describes this cake "a means to discover witchcraft" and provides other details such as that it was made from rye meal and urine from the afflicted girls and was fed to a dog. In the Church Records, Parris describes speaking with Sibley privately on March 25, 1692, about her "grand error" and accepted her "sorrowful confession." After the main sermon on March 27, and the wider congregation was dismissed, Parris addressed covenanted church-members about it and admonished all the congregation against "going to the Devil for help against the Devil." He stated that while "calamities" that had begun in his own household "it never brake forth to any considerable light, until diabolical means were used, by the making of a cake by my Indian man, who had his direction from this our sister, Mary Sibley." This doesn't seem to square with Lawson's account dating it around March 8. The first complaints were February 29 and the first arrests were March 1. Traditionally, the allegedly afflicted girls are said to have been entertained by Parris' slave, Tituba. A variety of secondary sources, starting with

Traditionally, the allegedly afflicted girls are said to have been entertained by Parris' slave, Tituba. A variety of secondary sources, starting with

Puritan ministers throughout the Massachusetts Bay Colony were exceedingly interested in the trial. Several traveled to Salem in order to gather information about the trial. After witnessing the trials first-hand and gathering accounts, these ministers presented various opinions about the trial starting in 1692.

Deodat Lawson, a former minister in Salem Village, visited Salem Village in March and April 1692. The resulting publication, entitled ''A Brief and True Narrative of Some Remarkable Passages Relating to Sundry Persons Afflicted by Witchcraft, at Salem Village: Which happened from the Nineteenth of March, to the Fifth of April 1692'', was published while the trials were ongoing and relates evidence meant to convict the accused. Simultaneous with Lawson, William Milbourne, a Baptist minister in Boston, publicly petitioned the General Assembly in early June 1692, challenging the use of spectral evidence by the Court. Milbourne had to post £200 bond (equal to £, or about US$42,000 today) or be arrested for "contriving, writing and publishing the said scandalous Papers".

Puritan ministers throughout the Massachusetts Bay Colony were exceedingly interested in the trial. Several traveled to Salem in order to gather information about the trial. After witnessing the trials first-hand and gathering accounts, these ministers presented various opinions about the trial starting in 1692.

Deodat Lawson, a former minister in Salem Village, visited Salem Village in March and April 1692. The resulting publication, entitled ''A Brief and True Narrative of Some Remarkable Passages Relating to Sundry Persons Afflicted by Witchcraft, at Salem Village: Which happened from the Nineteenth of March, to the Fifth of April 1692'', was published while the trials were ongoing and relates evidence meant to convict the accused. Simultaneous with Lawson, William Milbourne, a Baptist minister in Boston, publicly petitioned the General Assembly in early June 1692, challenging the use of spectral evidence by the Court. Milbourne had to post £200 bond (equal to £, or about US$42,000 today) or be arrested for "contriving, writing and publishing the said scandalous Papers".

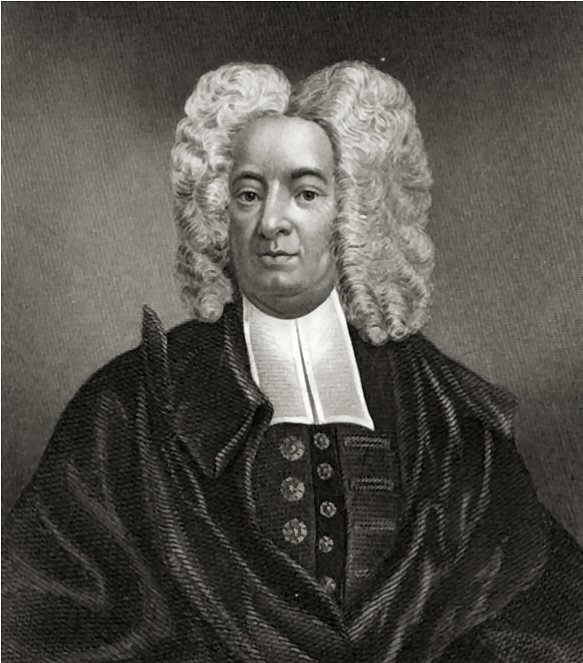

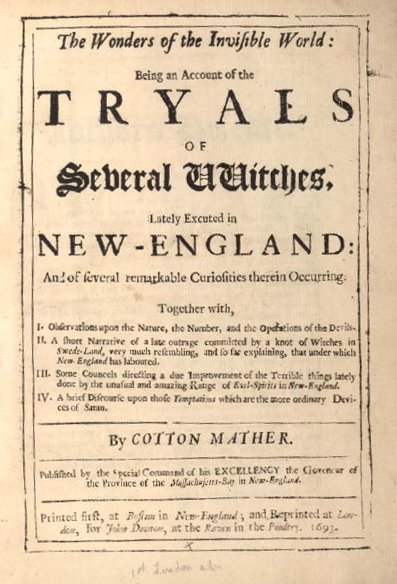

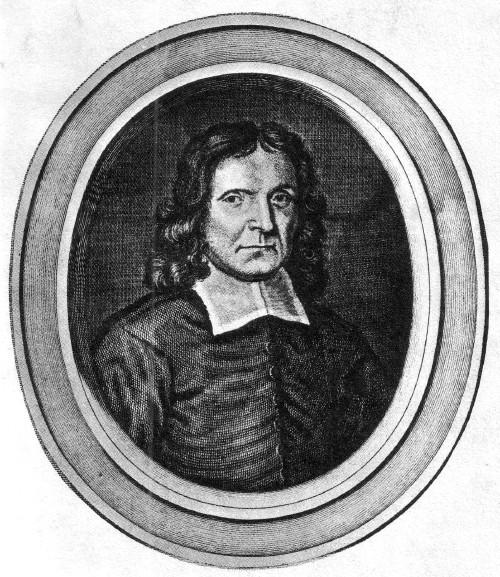

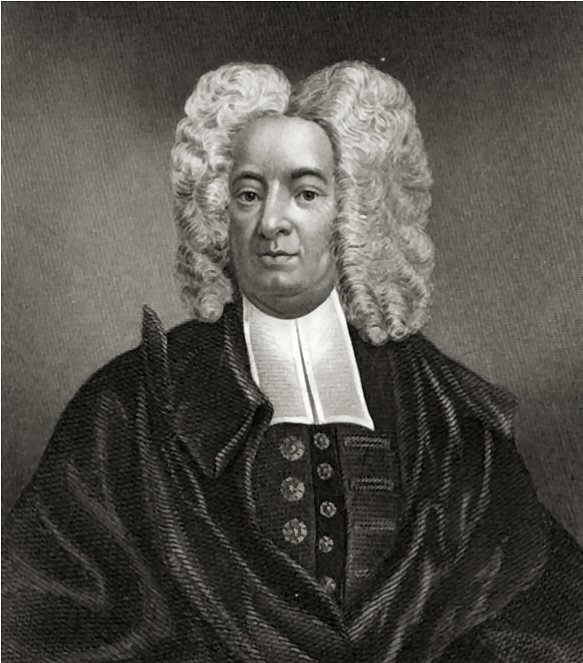

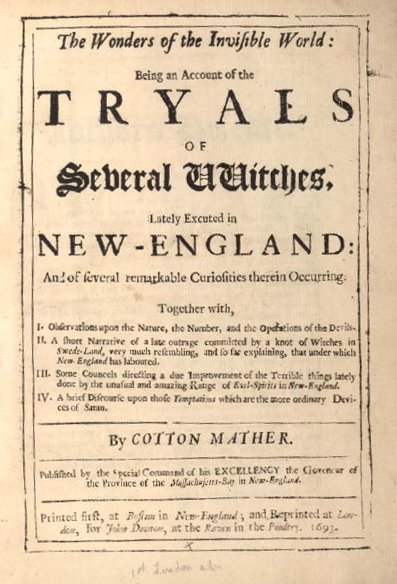

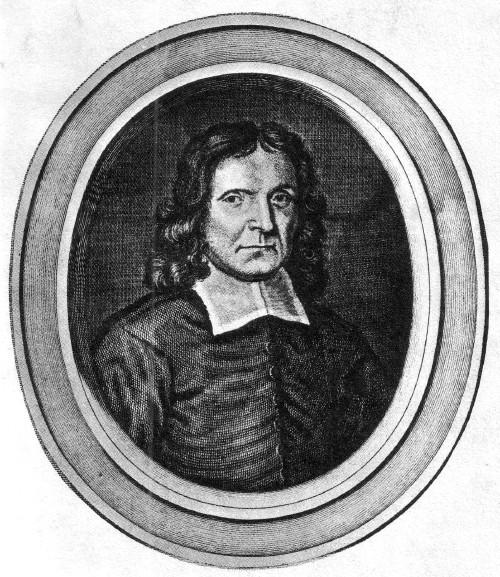

The most famous primary source about the trials is Cotton Mather's ''Wonders of the Invisible World: Being an Account of the Tryals of Several Witches, Lately Executed in New-England'', printed in October 1692. This text had a tortured path to publication. Initially conceived as a promotion of the trials and a triumphant celebration of Mather's leadership, Mather had to rewrite the text and disclaim personal involvement as suspicion about spectral evidence started to build. Regardless, it was published in both Boston and London, with an introductory letter of endorsement by William Stoughton, the Chief Magistrate. The book included accounts of five trials, with much of the material copied directly from the court records, which were supplied to Mather by Stephen Sewall, a clerk in the court.

The most famous primary source about the trials is Cotton Mather's ''Wonders of the Invisible World: Being an Account of the Tryals of Several Witches, Lately Executed in New-England'', printed in October 1692. This text had a tortured path to publication. Initially conceived as a promotion of the trials and a triumphant celebration of Mather's leadership, Mather had to rewrite the text and disclaim personal involvement as suspicion about spectral evidence started to build. Regardless, it was published in both Boston and London, with an introductory letter of endorsement by William Stoughton, the Chief Magistrate. The book included accounts of five trials, with much of the material copied directly from the court records, which were supplied to Mather by Stephen Sewall, a clerk in the court.

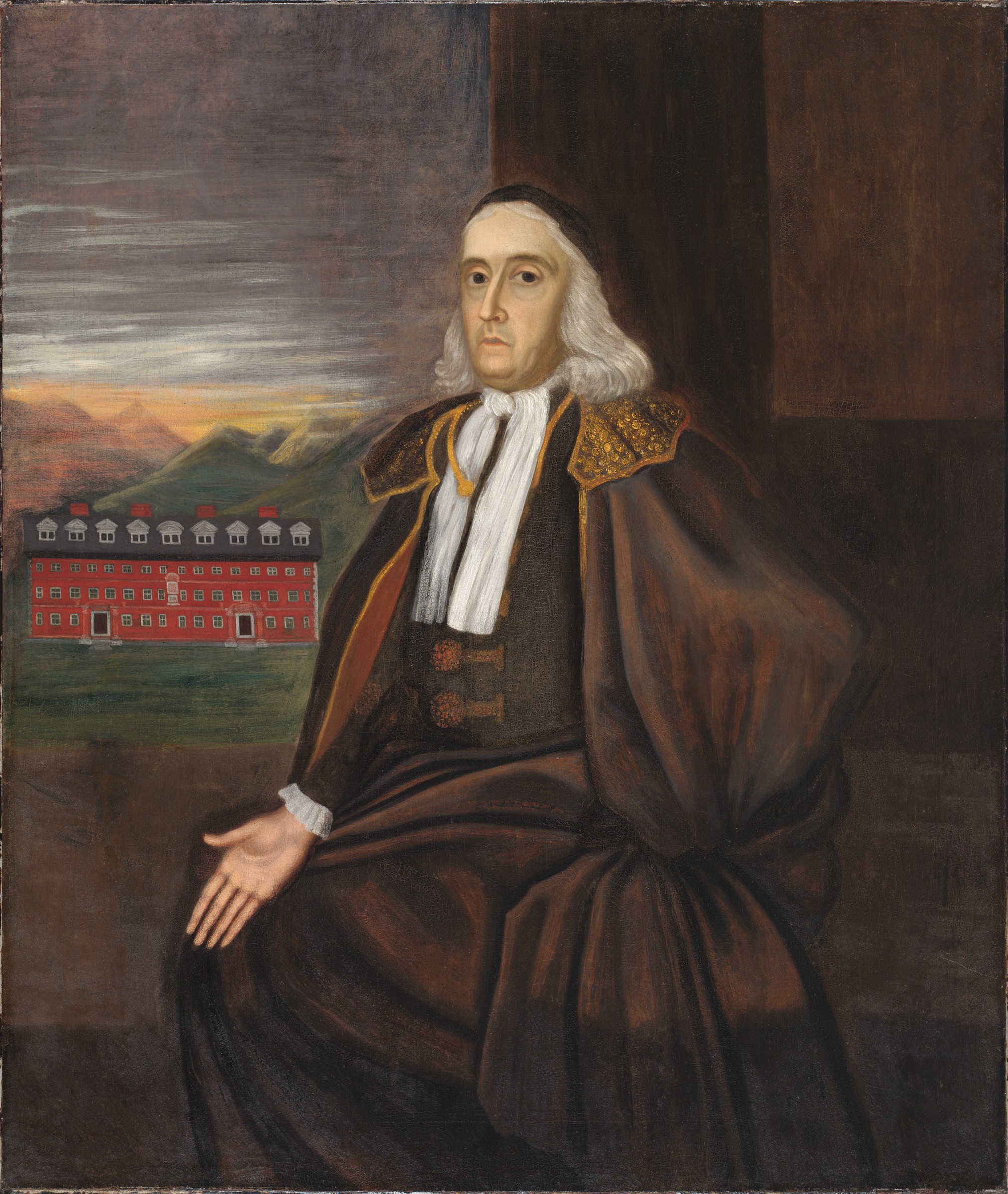

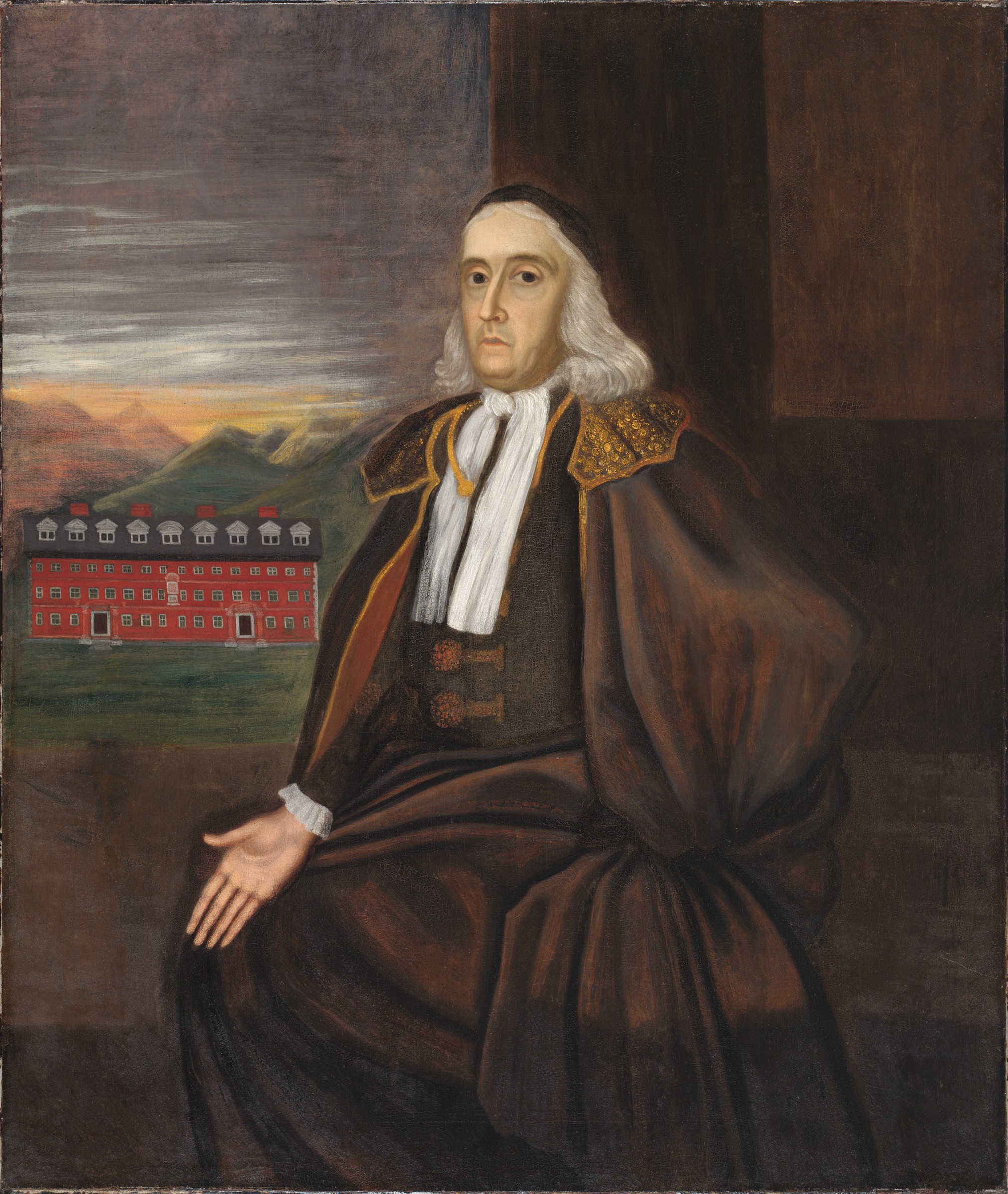

Cotton Mather's father,

Cotton Mather's father,

The first indication that public calls for justice were not over occurred in 1695 when Thomas Maule, a noted Quaker, publicly criticized the handling of the trials by the Puritan leaders in Chapter 29 of his book ''Truth Held Forth and Maintained'', expanding on

The first indication that public calls for justice were not over occurred in 1695 when Thomas Maule, a noted Quaker, publicly criticized the handling of the trials by the Puritan leaders in Chapter 29 of his book ''Truth Held Forth and Maintained'', expanding on  On December 17, 1696, the General Court ruled that there would be a fast day on January 14, 1697, "referring to the late Tragedy, raised among us by Satan and his Instruments." On that day, Samuel Sewall asked Rev. Samuel Willard to read aloud his apology to the congregation of Boston's South Church, "to take the Blame & Shame" of the "late Commission of Oyer & Terminer at Salem". Thomas Fiske and eleven other trial jurors also asked forgiveness.

From 1693 to 1697,

On December 17, 1696, the General Court ruled that there would be a fast day on January 14, 1697, "referring to the late Tragedy, raised among us by Satan and his Instruments." On that day, Samuel Sewall asked Rev. Samuel Willard to read aloud his apology to the congregation of Boston's South Church, "to take the Blame & Shame" of the "late Commission of Oyer & Terminer at Salem". Thomas Fiske and eleven other trial jurors also asked forgiveness.

From 1693 to 1697,

/ref> Calef could not get it published in Boston and he had to take it to London, where it was published in 1700. Scholars of the trials—Hutchinson, Upham, Burr, and even Poole—have relied on Calef's compilation of documents. John Hale, a minister in Beverly who was present at many of the proceedings, had completed his book, ''A Modest Enquiry into the Nature of Witchcraft'' in 1697, which was not published until 1702, after his death, and perhaps in response to Calef's book. Expressing regret over the actions taken, Hale admitted, "Such was the darkness of that day, the tortures and lamentations of the afflicted, and the power of former presidents, that we walked in the clouds, and could not see our way." Various petitions were filed between 1700 and 1703 with the Massachusetts government, demanding that the convictions be formally reversed. Those tried and found guilty were considered dead in the eyes of the law, and with convictions still on the books, those not executed were vulnerable to further accusations. The General Court initially reversed the attainder only for those who had filed petitions, only three people who had been convicted but not executed: Abigail Faulkner Sr., Elizabeth Proctor and Sarah Wardwell. In 1703, another petition was filed, requesting a more equitable settlement for those wrongly accused, but it was not until 1709, when the General Court received a further request, that it took action on this proposal. In May 1709, 22 people who had been convicted of witchcraft, or whose relatives had been convicted of witchcraft, presented the government with a petition in which they demanded both a reversal of attainder and compensation for financial losses. Repentance was evident within the Salem Village church. Rev. Joseph Green and the members of the church voted on February 14, 1703, after nearly two months of consideration, to reverse the excommunication of Martha Corey. On August 25, 1706, when

Repentance was evident within the Salem Village church. Rev. Joseph Green and the members of the church voted on February 14, 1703, after nearly two months of consideration, to reverse the excommunication of Martha Corey. On August 25, 1706, when

, rebeccanurse.org; accessed December 24, 2014. Not all the condemned had been exonerated in the early 18th century. In 1957, descendants of the six people who had been wrongly convicted and executed but who had not been included in the bill for a reversal of

Not all the condemned had been exonerated in the early 18th century. In 1957, descendants of the six people who had been wrongly convicted and executed but who had not been included in the bill for a reversal of

The 300th anniversary of the trials was marked in 1992 in Salem and Danvers by a variety of events. A memorial park was dedicated in Salem which included stone slab benches inserted in the stone wall of the park for each of those executed in 1692. Speakers at the ceremony in August included playwright

The 300th anniversary of the trials was marked in 1992 in Salem and Danvers by a variety of events. A memorial park was dedicated in Salem which included stone slab benches inserted in the stone wall of the park for each of those executed in 1692. Speakers at the ceremony in August included playwright

newspapers.com

"New Law Exonerates", ''Boston Globe'', 1 November 2001. Land in the area was purchased by the city of Salem in 1936 and renamed "Witch Memorial Land" but no memorial was constructed on the site, and popular misconception persisted that the executions had occurred at the top of Gallows Hill. Rebecca Eames of Boxford, who was brought to Salem for questioning, stated that she was held at "the house below the hill" where she could see people attending executions. This helped researchers rule out the summit as the execution site. In January 2016, the

Land in the area was purchased by the city of Salem in 1936 and renamed "Witch Memorial Land" but no memorial was constructed on the site, and popular misconception persisted that the executions had occurred at the top of Gallows Hill. Rebecca Eames of Boxford, who was brought to Salem for questioning, stated that she was held at "the house below the hill" where she could see people attending executions. This helped researchers rule out the summit as the execution site. In January 2016, the

Salem Witchcraft Trials: The Perception Of Women In History, Literature And Culture

University of Niš, Serbia, 2010, pp. 2–4.

law.umkc.edu

(accessed June 5, 2010) * Trans. Montague Summer. Questions VII & XI. "Maleus Maleficarum Part I.

sacred-texts.com

June 9, 2010. * * * * * * * * The Examination of Bridget Bishop, April 19, 1692. "Examination and Evidence of Some Accused Witches in Salem, 1692

law.umkc.edu

(accessed June 5, 2010) * The Examination of Sarah Good, March 1, 1692. "Examination and Evidence of Some the Accused Witches in Salem, 1692

law.umkc.edu

(accessed June 6, 2010)

excerpt and text search

* Mappen, Marc, ed. ''Witches & Historians: Interpretations of Salem''. 2nd Edition. Keiger: Malabar, FL. 1996. * Miller, Arthur. '' The Crucible'' – a play which compares

Salem Witchcraft Trials of 1692

University of Missouri-Kansas City Law School

University of Virginia, archive of extensive primary sources, including court papers, maps, interactive maps, and biographies (includes former "Massachusetts Historical Society" link)

''Salem Witchcraft, Volumes I and II''

by Charles Upham, 1867,

SalemWitchTrials.com Essays, biographies of the accused and afflicted

Salem Witch Trials website

Cotton Mather, ''The Wonders of the Invisible World. Observations as Well Historical as Theological, upon the Nature, the Number, and the Operations of the Devils'' (1693)

(online pdf edition), at Digital Commons

Salem Witch Trials

, Salem website. {{DEFAULTSORT:Salem Witch Trials 1692 in Massachusetts 1693 in Massachusetts History of Salem, Massachusetts Mass psychogenic illness Religiously motivated violence in the United States Salem, Massachusetts Trials in the United States Women sentenced to death Men sentenced to death

The Salem witch trials were a series of hearings and prosecutions of people accused of

The Salem witch trials were a series of hearings and prosecutions of people accused of witchcraft

Witchcraft traditionally means the use of magic or supernatural powers to harm others. A practitioner is a witch. In medieval and early modern Europe, where the term originated, accused witches were usually women who were believed to have ...

in colonial Massachusetts

Colonial or The Colonial may refer to:

* Colonial, of, relating to, or characteristic of a colony or colony (biology)

Architecture

* American colonial architecture

* French Colonial

* Spanish Colonial architecture

Automobiles

* Colonial (1920 a ...

between February 1692 and May 1693. More than 200 people were accused. Thirty people were found guilty, 19 of whom were executed by hanging

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging ...

(14 women and five men). One other man, Giles Corey, was pressed to death after refusing to enter a plea, and at least five people died in jail.

Arrests were made in numerous towns beyond Salem and Salem Village (known today as Danvers), notably Andover

Andover may refer to:

Places Australia

*Andover, Tasmania

Canada

* Andover Parish, New Brunswick

* Perth-Andover, New Brunswick

United Kingdom

* Andover, Hampshire, England

** RAF Andover, a former Royal Air Force station

United States

* Andov ...

and Topsfield. The grand juries and trials for this capital crime

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that ...

were conducted by a Court of Oyer and Terminer in 1692 and by a Superior Court of Judicature in 1693, both held in Salem Town, where the hangings also took place. It was the deadliest witch hunt in the history of colonial North America. Only fourteen other women and two men had been executed in Massachusetts and Connecticut during the 17th century.

The episode is one of Colonial America's most notorious cases of mass hysteria. It has been used in political rhetoric and popular literature as a vivid cautionary tale about the dangers of isolation, religious extremism, false accusations, and lapses in due process. It was not unique, but a Colonial American example of the much broader phenomenon of witch trials in the early modern period

Witch trials in the early modern period saw that between 1400 to 1782, around 40,000 to 60,000 were killed due to suspicion that they were practicing witchcraft. Some sources estimate that a total of 100,000 trials occurred at its maximum for a s ...

, which took place also in Europe. Many historians consider the lasting effects of the trials to have been highly influential in the history of the United States

The history of the lands that became the United States began with the arrival of the first people in the Americas around 15,000 BC. Numerous indigenous cultures formed, and many saw transformations in the 16th century away from more densely ...

. According to historian George Lincoln Burr

George Lincoln Burr (January 30, 1857 – June 27, 1938) was a US historian, diplomat, author, and educator, best known as a Professor of History and Librarian at Cornell University, and as the closest collaborator of Andrew Dickson White, the ...

, "the Salem witchcraft was the rock on which the theocracy

Theocracy is a form of government in which one or more deities are recognized as supreme ruling authorities, giving divine guidance to human intermediaries who manage the government's daily affairs.

Etymology

The word theocracy originates fr ...

shattered."

At the 300th anniversary events in 1992 to commemorate the victims of the trials, a park was dedicated in Salem and a memorial in Danvers. In 1957, an act passed by the Massachusetts legislature absolved six people, while another one, passed in 2001, absolved five other victims. As of 2004, there was still talk about exonerating all of the victims, though some think that happened in the 18th century as the Massachusetts colonial legislature was asked to reverse the attainder

In English criminal law, attainder or attinctura was the metaphorical "stain" or "corruption of blood" which arose from being condemned for a serious capital crime (felony or treason). It entailed losing not only one's life, property and hereditar ...

s of "George Burroughs and others". In January 2016, the University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. Founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson, the university is ranked among the top academic institutions in the United States, with highly selective ad ...

announced its Gallows Hill Project team had determined the execution site in Salem, where the 19 "witches" had been hanged. The city dedicated the ''Proctor's Ledge Memorial'' to the victims there in 2017.Caroline Newman, "X Marks the Spot"''UVA Today,'' 16 January 2016, accessed 28 April 2016

Background

While witch trials had begun to fade out across much of Europe by the mid-17th century, they continued on the fringes of Europe and in the American Colonies. The events in 1692–1693 in Salem became a brief outburst of a sort of hysteria in the New World, while the practice was already waning in most of Europe. In 1668, in ''Against Modern Sadducism'',Joseph Glanvill

Joseph Glanvill (1636 – 4 November 1680) was an English writer, philosopher, and clergyman. Not himself a scientist, he has been called "the most skillful apologist of the virtuosi", or in other words the leading propagandist for the approa ...

claimed that he could prove the existence of witches and ghosts of the supernatural realm. Glanvill wrote about the "denial of the bodily resurrection, and the upernaturalspirits."Glanvill, Joseph. "Essay IV Against modern Sadducism in the matter of Witches and Apparitions", ''Essay on Several Important Subjects in Philosophy and Religion'', 2nd ed., London; printed by Jd for John Baker and H. Mortlock, 1676, pp. 1–4 (in the history 201 course-pack compiled by S. McSheffrey & T. McCormick), p. 26

In his treatise, Glanvill claimed that ingenious men should believe in witches and apparitions; if they doubted the reality of spirits, they not only denied demons but also the almighty God. Glanvill wanted to prove that the supernatural could not be denied; those who did deny apparitions were considered heretics, for it also disproved their beliefs in angels. Works by men such as Glanvill and Cotton Mather

Cotton Mather (; February 12, 1663 – February 13, 1728) was a New England Puritan clergyman and a prolific writer. Educated at Harvard College, in 1685 he joined his father Increase as minister of the Congregationalist Old North Meeting H ...

tried to prove that "demons were alive."

Accusations

The trials were started after people had been accused of witchcraft, primarily by teenage girls such as Elizabeth Hubbard, 17, as well as some who were younger. Dorothy Good was four or five years old when she was accused of witchcraft.Recorded witchcraft executions in New England

The earliest recorded witchcraft execution was that ofAlse Young

Alse Young (1615 – 26 May 1647) of Windsor, Connecticut — sometimes Achsah Young or Alice Young — was the first recorded instance of execution for witchcraft in the thirteen American colonies. She had one child, Alice Beamon (Young), b ...

in 1647 in Hartford, Connecticut

Hartford is the capital city of the U.S. state of Connecticut. It was the seat of Hartford County until Connecticut disbanded county government in 1960. It is the core city in the Greater Hartford metropolitan area. Census estimates since t ...

, the start of the Connecticut Witch Trials The Connecticut Witch Trials, also sometimes referred to as the Hartford witch trials, occurred from 1647 to 1663. They were the first large-scale witch trials in the American colonies, predating the Salem Witch Trials by nearly thirty years. John M ...

which lasted until 1663. Historian Clarence F. Jewett included a list of other people executed in New England in his 1881 book.

Political context

New England had been settled by religious dissenters seeking to build a Bible-based society according to their own chosen discipline. The original 1629Royal Charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, b ...

of the Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, the northernmost of the several colonies later reorganized as th ...

was vacated in 1684, after which King James II installed Sir Edmund Andros

Sir Edmund Andros (6 December 1637 – 24 February 1714) was an English colonial administrator in British America. He was the governor of the Dominion of New England during most of its three-year existence. At other times, Andros served ...

as the governor of the Dominion of New England

The Dominion of New England in America (1686–1689) was an administrative union of English colonies covering New England and the Mid-Atlantic Colonies (except for Delaware Colony and the Province of Pennsylvania). Its political structure repres ...

. Andros was ousted in 1689 after the "Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

" in England replaced the Catholic James II with the Protestant co-rulers William

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

and Mary.

Simon Bradstreet and Thomas Danforth, the colony's last leaders under the old charter, resumed their posts as governor and deputy governor, but lacked constitutional authority to rule because the old charter had been vacated. At the same time, tensions erupted between English colonists settling in "the Eastward" (the present-day coast of Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and nor ...

) and French-supported Wabanaki Indians of that territory in what came to be known as King William's War

King William's War (also known as the Second Indian War, Father Baudoin's War, Castin's War, or the First Intercolonial War in French) was the North American theater of the Nine Years' War (1688–1697), also known as the War of the Grand Alli ...

. This was 13 years after the devastating King Philip's War

King Philip's War (sometimes called the First Indian War, Metacom's War, Metacomet's War, Pometacomet's Rebellion, or Metacom's Rebellion) was an armed conflict in 1675–1676 between indigenous inhabitants of New England and New England coloni ...

with the Wampanoag

The Wampanoag , also rendered Wôpanâak, are an Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands based in southeastern Massachusetts and historically parts of eastern Rhode Island,Salwen, "Indians of Southern New England and Long Island," p. ...

and other indigenous tribes in southern and western New England. In October 1690, Sir William Phips

Sir William Phips (or Phipps; February 2, 1651 – February 18, 1695) was born in Maine in the Massachusetts Bay Colony and was of humble origin, uneducated, and fatherless from a young age but rapidly advanced from shepherd boy, to shipwright, s ...

led an unsuccessful attack on French-held Quebec. Between 1689 and 1692, Native Americans continued to attack many English settlements along the Maine coast, leading to the abandonment of some of the settlements and resulting in a flood of refugees into areas like Essex County.

A new charter for the enlarged Province of Massachusetts Bay

The Province of Massachusetts Bay was a colony in British America which became one of the thirteen original states of the United States. It was chartered on October 7, 1691, by William III and Mary II, the joint monarchs of the kingdoms of ...

was given final approval in England on October 16, 1691. Increase Mather

Increase Mather (; June 21, 1639 Old Style – August 23, 1723 Old Style) was a New England Puritan clergyman in the Massachusetts Bay Colony and president of Harvard College for twenty years (1681–1701). He was influential in the admini ...

had been working on obtaining the charter for four years, with William Phips often joining him in London and helping him gain entry to Whitehall. Increase Mather had published a book on witchcraft in 1684 and his son Cotton Mather

Cotton Mather (; February 12, 1663 – February 13, 1728) was a New England Puritan clergyman and a prolific writer. Educated at Harvard College, in 1685 he joined his father Increase as minister of the Congregationalist Old North Meeting H ...

published one in 1689. Increase Mather brought out a London edition of his son's book in 1690. Increase Mather claimed to have picked all the men to be included in the new government. News of Mather's charter and the appointment of Phips as the new governor had reached Boston by late January, and a copy of the new charter reached Boston on February 8, 1692. Phips arrived in Boston on May 14 and was sworn in as governor two days later, along with Lieutenant Governor William Stoughton. One of the first orders of business for the new governor and council on May 27, 1692, was the formal nomination of county justices of the peace

A justice of the peace (JP) is a judicial officer of a lower or '' puisne'' court, elected or appointed by means of a commission (letters patent) to keep the peace. In past centuries the term commissioner of the peace was often used with the sam ...

, sheriff

A sheriff is a government official, with varying duties, existing in some countries with historical ties to England where the office originated. There is an analogous, although independently developed, office in Iceland that is commonly transla ...

s, and the commission of a Special Court of Oyer and Terminer to handle the large numbers of people who were "thronging" the jails.

Local context

Salem Village (present-day

Salem Village (present-day Danvers, Massachusetts

Danvers is a town in Essex County, Massachusetts, United States, located on the Danvers River near the northeastern coast of Massachusetts. The suburb is a fairly short ride from Boston and is also in close proximity to the renowned beaches of Glo ...

) was known for its fractious population, who had many many disputes internally and with Salem Town (present-day Salem). Arguments about property lines, grazing rights, and church privileges were rife, and neighbors considered the population as "quarrelsome." In 1672, the villagers had voted to hire a minister of their own, apart from Salem Town. The first two ministers, James Bayley (1673–1679) and George Burroughs

George Burroughs ( 1650August 19, 1692) was an American religious leader who was the only minister executed for witchcraft during the course of the Salem witch trials. He is best known for reciting the Lord's Prayer during his execution, some ...

(1680–1683), stayed only a few years each, departing after the congregation failed to pay their full rate. (Burroughs was subsequently arrested at the height of the witchcraft hysteria and was hanged as a witch in August 1692.)

Despite the ministers' rights being upheld by the General Court and the parish being admonished, each of the two ministers still chose to leave. The third minister, Deodat Lawson (1684–1688), stayed for a short time, leaving after the church in Salem refused to ordain him—and therefore not over issues with the congregation. The parish disagreed about Salem Village's choice of Samuel Parris as its first ordained minister. On June 18, 1689, the villagers agreed to hire Parris for £66 annually, "one third part in money and the other two third parts in provisions," and use of the parsonage.

On October 10, 1689, however, they raised his benefits, voting to grant him the deed to the parsonage and two acres (0.8 hectares) of land. This conflicted with a 1681 village resolution which stated that "it shall not be lawful for the inhabitants of this village to convey the houses or lands or any other concerns belonging to the Ministry to any particular persons or person: not for any cause by vote or other ways".

Though the prior ministers' fates and the level of contention in Salem Village were valid reasons for caution in accepting the position, Rev. Parris increased the village's divisions by delaying his acceptance. He did not seem able to settle his new parishioners' disputes: by deliberately seeking out "iniquitous behavior" in his congregation and making church members in good standing suffer public penance for small infractions, he contributed significantly to the tension within the village. Its bickering increased unabated. Historian Marion Starkey suggests that, in this atmosphere, serious conflict may have been inevitable.

Religious context

Prior to the constitutional turmoil of the 1680s, the Massachusetts government had been dominated by conservative

Prior to the constitutional turmoil of the 1680s, the Massachusetts government had been dominated by conservative Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

secular leaders. While Puritans and the Church of England both shared a common influence in Calvinism

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John C ...

, Puritans had opposed many of the traditions of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Brit ...

, including use of the Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the name given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The original book, published in 1549 in the reign ...

, the use of clergy vestments during services, the use of the sign of the cross

Making the sign of the cross ( la, signum crucis), or blessing oneself or crossing oneself, is a ritual blessing made by members of some branches of Christianity. This blessing is made by the tracing of an upright cross or + across the body with ...

at baptism

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost ...

, and kneeling to receive communion, all of which they believed constituted popery. King Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

was hostile to this viewpoint, and Anglican church officials tried to repress these dissenting views during the 1620s and 1630s. Some Puritans and other religious minorities had sought refuge in the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

but ultimately many made a major migration to colonial North America to establish their own society.

These immigrants, who were mostly constituted of families, established several of the earliest colonies in New England, of which the Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, the northernmost of the several colonies later reorganized as th ...

was the largest and most economically important. They intended to build a society based on their religious beliefs. Colonial leaders were elected by the freemen of the colony, those individuals who had had their religious experiences formally examined and had been admitted to one of the colony's Puritan congregations. The colonial leadership were prominent members of their congregations and regularly consulted with the local ministers on issues facing the colony.

In the early 1640s, England erupted in civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

. The Puritan-dominated Parliamentarians emerged victorious, and the Crown was supplanted by the Protectorate

The Protectorate, officially the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland, refers to the period from 16 December 1653 to 25 May 1659 during which England, Wales, Scotland, Ireland and associated territories were joined together in the Co ...

of Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three ...

in 1653. Its failure led to restoration of the old order under Charles II. Emigration to New England slowed significantly in these years. In Massachusetts, a successful merchant class began to develop that was less religiously motivated than the colony's early settlers.

Gender context

An overwhelming majority of people accused and convicted of witchcraft were women (about 78%). Overall, the Puritan belief and prevailing New England culture was that women were inherently sinful and more susceptible to damnation than men were. Throughout their daily lives, Puritans, especially Puritan women, actively attempted to thwart attempts by the Devil to overtake them and their souls. Indeed, Puritans held the belief that men and women were equal in the eyes of God, but not in the eyes of the Devil. Women's souls were seen as unprotected in their weak and vulnerable bodies. Several factors may explain why women were more likely to admit guilt of witchcraft than men. Historian Elizabeth Reis asserts that some likely believed they had truly given in to the Devil, and others might have believed they had done so temporarily. However, because those who confessed were reintegrated into society, some women might have confessed in order to spare their own lives. Quarrels with neighbors often incited witchcraft allegations. One example of this is Abigail Faulkner, who was accused in 1692. Faulkner admitted she was "angry at what folk said," and the Devil may have temporarily overtaken her, causing harm to her neighbors. Women who did not conform to the norms of Puritan society were more likely to be the target of an accusation, especially those who were unmarried or did not have children.Publicising witchcraft

Cotton Mather

Cotton Mather (; February 12, 1663 – February 13, 1728) was a New England Puritan clergyman and a prolific writer. Educated at Harvard College, in 1685 he joined his father Increase as minister of the Congregationalist Old North Meeting H ...

, a minister of Boston's North Church, was a prolific publisher of pamphlets, including some that expressed his belief in witchcraft

Witchcraft traditionally means the use of magic or supernatural powers to harm others. A practitioner is a witch. In medieval and early modern Europe, where the term originated, accused witches were usually women who were believed to have ...

. In his book ''Memorable Providences Relating to Witchcrafts and Possessions'' (1689), Mather describes his "oracular observations" and how "stupendous witchcraft" had affected the children of Boston mason John Goodwin.Mather, Cotton. ''Memorable Providences, Relating to Witchcraft and Possessions. 1689'law.umkc.edu

; accessed January 18, 2019. Mather illustrates how the Goodwins' eldest child had been tempted by the devil and had stolen linen from the washerwoman Goody Glover.''Records of the Salem Witch-Hunt'', Rosenthal, et al., 2009, p. 15, n2 Glover, of Irish Catholic descent, was characterized as a disagreeable old woman and described by her husband as a witch; this may have been why she was accused of casting spells on the Goodwin children. After the event, four out of six Goodwin children began to have strange fits, or what some people referred to as "the disease of astonishment." The manifestations attributed to the disease quickly became associated with witchcraft. Symptoms included neck and back pains, tongues being drawn from their throats, and loud random outcries; other symptoms included having no control over their bodies such as becoming limber, flapping their arms like birds, or trying to harm others as well as themselves. These symptoms fuelled the craze of 1692.

Timeline

Initial events

Abigail Williams

Abigail Williams (born c. 1681, date of death unknown) was an 11- or 12-year-old girl who, along with nine-year-old Betty Parris, was among the first of the children to falsely accuse their neighbors of witchcraft in 1692; these accusations eve ...

(age 11), the daughter and the niece, respectively, of Reverend Samuel Parris, began to have fits described as "beyond the power of epileptic fits or natural disease to effect" by John Hale, the minister of the nearby town of Beverly. The girls screamed, threw things about the room, uttered strange sounds, crawled under furniture, and contorted themselves into peculiar positions, according to the eyewitness account of Reverend Deodat Lawson, a former minister in Salem Village.

The girls complained of being pinched and pricked with pins. A doctor, historically assumed to be William Griggs, could find no physical evidence of any ailment. Other young women in the village began to exhibit similar behaviors. When Lawson preached as a guest in the Salem Village meetinghouse, he was interrupted several times by the outbursts of the afflicted.

The first three people accused and arrested for allegedly afflicting Betty Parris, Abigail Williams, 12-year-old Ann Putnam, Jr., and Elizabeth Hubbard, were Sarah Good, Sarah Osborne, and Tituba—with Tituba being the first. Some historians believe that the accusation by Ann Putnam Jr. suggests that a family feud may have been a major cause of the witch trials. At the time, a vicious rivalry was underway between the Putnam and Porter families, one which deeply polarized the people of Salem. Citizens would often have heated debates, which escalated into full-fledged fighting, based solely on their opinion of the feud. Some of the physical symptoms resembled convulsive ergot poisoning, proposed 284 years later.

Good was a destitute woman accused of witchcraft because of her reputation. At her trial, she was accused of rejecting Puritan ideals of self-control and discipline when she chose to torment and "scorn hildreninstead of leading them towards the path of salvation".

Sarah Osborne rarely attended church meetings. She was accused of witchcraft because the Puritans believed that Osborne had her own self-interests in mind following her remarriage to an indentured servant

Indentured servitude is a form of Work (human activity), labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensa ...

. The citizens of the town disapproved of her trying to control her son's inheritance from her previous marriage.

Tituba, an enslaved South American Indian woman from the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greate ...

, likely became a target because of her ethnic differences from most of the other villagers. She was accused of attracting girls like Abigail Williams and Betty Parris with stories of enchantment from ''Malleus Maleficarum

The ''Malleus Maleficarum'', usually translated as the ''Hammer of Witches'', is the best known treatise on witchcraft. It was written by the German Catholic clergyman Heinrich Kramer (under his Latinized name ''Henricus Institor'') and first ...

''. These tales about sexual encounters with demons, swaying the minds of men, and fortune-telling were said to stimulate the imaginations of girls and made Tituba an obvious target of accusations.

Each of these women was a kind of outcast and exhibited many of the character traits typical of the "usual suspects" for witchcraft accusations; they were left to defend themselves. Brought before the local magistrates on the complaint of witchcraft, they were interrogated for several days, starting on March 1, 1692, then sent to jail.

In March, others were accused of witchcraft: Martha Corey, child Dorothy Good, and Rebecca Nurse in Salem Village, and Rachel Clinton in nearby Ipswich

Ipswich () is a port town and borough in Suffolk, England, of which it is the county town. The town is located in East Anglia about away from the mouth of the River Orwell and the North Sea. Ipswich is both on the Great Eastern Main Line ...

. Martha Corey had expressed skepticism about the credibility of the girls' accusations and thus drawn attention. The charges against her and Rebecca Nurse deeply troubled the community because Martha Corey was a full covenanted member of the Church in Salem Village, as was Rebecca Nurse in the Church in Salem Town. If such upstanding people could be witches, the townspeople thought, then anybody could be a witch, and church membership was no protection from accusation. Dorothy Good, the daughter of Sarah Good, was only four years old but was not exempted from questioning by the magistrates; her answers were construed as a confession that implicated her mother. In Ipswich, Rachel Clinton was arrested for witchcraft at the end of March on independent charges unrelated to the afflictions of the girls in Salem Village.

The initial examinations included physical exams where the accused were examined for unique markings such as moles, birth marks that were commonly believed to be associated with the Devil's influence. It was thought that those markings represented the Devil drinking the accused women's blood.

Accusations and examinations before local magistrates

When

When Sarah Cloyce

Sarah Cloyce (alt. Cloyes; Towne; c. 1641 – 1703) was among the many accused during Salem Witch Trials including two of her older sisters, Rebecca Nurse and Mary Eastey, who were both executed. Cloyce was about 50-years-old at the time and was ...

(Nurse's sister) and Elizabeth (Bassett) Proctor were arrested in April, they were brought before John Hathorne and Jonathan Corwin at a meeting in Salem Town. The men were both local magistrates and also members of the Governor's Council. Present for the examination were Deputy Governor Thomas Danforth, and Assistants Samuel Sewall, Samuel Appleton, James Russell and Isaac Addington. During the proceedings, objections by Elizabeth's husband, John Proctor, resulted in his arrest that day.

Within a week, Giles Corey (Martha's husband and a covenanted church member in Salem Town), Abigail Hobbs, Bridget Bishop

Bridget Bishop ( 1632 – 10 June 1692) was the first person executed for witchcraft during the Salem witch trials in 1692. Nineteen were hanged, and one, Giles Corey, was pressed to death. Altogether, about 200 people were tried.

Family life ...

, Mary Warren (a servant in the Proctor household and sometime accuser), and Deliverance Hobbs (stepmother of Abigail Hobbs), were arrested and examined. Abigail Hobbs, Mary Warren, and Deliverance Hobbs all confessed and began naming additional people as accomplices. More arrests followed: Sarah Wildes

Sarah Wildes (née Averell/Averill; baptized March 16, 1627 – ) was wrongly convicted of witchcraft during the Salem witch trials and was executed by hanging. She maintained her innocence throughout the process, and was later exonerated. Her hu ...

, William Hobbs (husband of Deliverance and father of Abigail), Nehemiah Abbott Jr., Mary Eastey

Mary Towne Eastey (also spelled Esty, Easty, Estey, Eastick, Eastie, or Estye) ( bap. August 24, 1634 – September 22, 1692) was a defendant in the Salem witch trials in colonial Massachusetts. She was executed by hanging in Salem in 1692.

...

(sister of Cloyce and Nurse), Edward Bishop Jr. and his wife Sarah Bishop, and Mary English.

On April 30, Reverend George Burroughs

George Burroughs ( 1650August 19, 1692) was an American religious leader who was the only minister executed for witchcraft during the course of the Salem witch trials. He is best known for reciting the Lord's Prayer during his execution, some ...

, Lydia Dustin, Susannah Martin

Susannah Martin (née North, baptized September 30, 1621 – July 19, 1692) was one of fourteen women executed for witchcraft during the Salem witch trials of colonial Massachusetts.

Early life

The English-born Martin was the fourth daughter ...

, Dorcas Hoar, Sarah Morey, and Philip English (Mary's husband) were arrested. Nehemiah Abbott Jr. was released because the accusers agreed he was not the person whose specter had afflicted them. Mary Eastey was released for a few days after her initial arrest because the accusers failed to confirm that it was she who had afflicted them; she was arrested again when the accusers reconsidered. In May, accusations continued to pour in, but some of the suspects began to evade apprehension. Multiple warrants were issued before John Willard and Elizabeth Colson were apprehended; George Jacobs Jr. and Daniel Andrews were not caught. Until this point, all the proceedings were investigative, but on May 27, 1692, William Phips ordered the establishment of a Special Court of Oyer and Terminer for Suffolk, Essex and Middlesex counties to prosecute the cases of those in jail. Warrants were issued for more people. Sarah Osborne, one of the first three persons accused, died in jail on May 10, 1692.

Warrants were issued for 36 more people, with examinations continuing to take place in Salem Village: Sarah Dustin (daughter of Lydia Dustin), Ann Sears, Bethiah Carter Sr. and her daughter Bethiah Carter Jr., George Jacobs Sr. and his granddaughter Margaret Jacobs, John Willard

John Willard ( 1657 - August 19, 1692) was one of the people executed for witchcraft in Salem, Massachusetts, during the Salem witch trials. He was hanged on Gallows Hill, Salem on August 19, 1692.

At the time of the first allegations of witchc ...

, Alice Parker

Alice Parker (born December 16, 1925) is an American composer, arranger, conductor, and teacher. She has authored five operas, eleven song-cycles, thirty-three cantatas, eleven works for chorus and orchestra, forty-seven choral suites, and ...

, Ann Pudeator

Ann Pudeator (November 13, 1621 – , 1692) was a wealthy septuagenarian widow who was accused of and convicted of witchcraft in the Salem witch trials in colonial Massachusetts. She was executed by hanging.

Personal life

Ann's maiden name is not ...

, Abigail Soames, George Jacobs Jr. (son of George Jacobs Sr. and father of Margaret Jacobs), Daniel Andrew, Rebecca Jacobs (wife of George Jacobs Jr. and sister of Daniel Andrew), Sarah Buckley and her daughter Mary Witheridge.

Also included were Elizabeth Colson, Elizabeth Hart, Thomas Farrar Sr. Roger Toothaker, Sarah Proctor (daughter of John and Elizabeth Proctor), Sarah Bassett (sister-in-law of Elizabeth Proctor), Susannah Roots, Mary DeRich (another sister-in-law of Elizabeth Proctor), Sarah Pease, Elizabeth Cary, Martha Carrier, Elizabeth Fosdick, Wilmot Redd, Sarah Rice, Elizabeth Howe, Capt. John Alden (son of John Alden and Priscilla Mullins), William Proctor (son of John and Elizabeth Proctor), John Flood, Mary Toothaker (wife of Roger Toothaker and sister of Martha Carrier) and her daughter Margaret Toothaker, and Arthur Abbott. When the Court of Oyer and Terminer convened at the end of May, the total number of people in custody was 62.

Cotton Mather wrote to one of the judges, John Richards, a member of his congregation, on May 31, 1692, expressing his support of the prosecutions, but cautioning him,

Formal prosecution: The Court of Oyer and Terminer

The Court of Oyer and Terminer convened in Salem Town on June 2, 1692, with William Stoughton, the new Lieutenant Governor, as Chief Magistrate, Thomas Newton as the Crown's Attorney prosecuting the cases, and Stephen Sewall as clerk. Bridget Bishop's case was the first brought to the grand jury, who endorsed all the indictments against her. Bishop was described as not living a Puritan lifestyle, for she wore black clothing and odd costumes, which was against the Puritan code. When she was examined before her trial, Bishop was asked about her coat, which had been awkwardly "cut or torn in two ways".

This, along with her "immoral" lifestyle, affirmed to the jury that Bishop was a witch. She went to trial the same day and was convicted. On June 3, the grand jury endorsed indictments against Rebecca Nurse and John Willard, but they did not go to trial immediately, for reasons which are unclear. Bishop was executed by hanging on June 10, 1692.

Immediately following this execution, the court adjourned for 20 days (until June 30) while it sought advice from New England's most influential ministers "upon the state of things as they then stood." Their collective response came back dated June 15 and composed by Cotton Mather:

Hutchinson sums the letter, "The two first and the last sections of this advice took away the force of all the others, and the prosecutions went on with more vigor than before." (Reprinting the letter years later in ''Magnalia'', Cotton Mather left out these "two first and the last" sections.) Major Nathaniel Saltonstall, Esq., resigned from the court on or about June 16, presumably dissatisfied with the letter and that it had not outright barred the admission of

The Court of Oyer and Terminer convened in Salem Town on June 2, 1692, with William Stoughton, the new Lieutenant Governor, as Chief Magistrate, Thomas Newton as the Crown's Attorney prosecuting the cases, and Stephen Sewall as clerk. Bridget Bishop's case was the first brought to the grand jury, who endorsed all the indictments against her. Bishop was described as not living a Puritan lifestyle, for she wore black clothing and odd costumes, which was against the Puritan code. When she was examined before her trial, Bishop was asked about her coat, which had been awkwardly "cut or torn in two ways".

This, along with her "immoral" lifestyle, affirmed to the jury that Bishop was a witch. She went to trial the same day and was convicted. On June 3, the grand jury endorsed indictments against Rebecca Nurse and John Willard, but they did not go to trial immediately, for reasons which are unclear. Bishop was executed by hanging on June 10, 1692.

Immediately following this execution, the court adjourned for 20 days (until June 30) while it sought advice from New England's most influential ministers "upon the state of things as they then stood." Their collective response came back dated June 15 and composed by Cotton Mather:

Hutchinson sums the letter, "The two first and the last sections of this advice took away the force of all the others, and the prosecutions went on with more vigor than before." (Reprinting the letter years later in ''Magnalia'', Cotton Mather left out these "two first and the last" sections.) Major Nathaniel Saltonstall, Esq., resigned from the court on or about June 16, presumably dissatisfied with the letter and that it had not outright barred the admission of spectral evidence Spectral evidence is a form of legal evidence based upon the testimony of those who claim to have experienced visions.

Such testimony was frequently given during the witch trials of the 16th and 17th centuries. The alleged victims of witchcraft w ...

. According to Upham, Saltonstall deserves the credit for "being the only public man of his day who had the sense or courage to condemn the proceedings, at the start." (chapt. VII) More people were accused, arrested and examined, but now in Salem Town, by former local magistrates John Hathorne, Jonathan Corwin, and Bartholomew Gedney, who had become judges of the Court of Oyer and Terminer. Suspect Roger Toothaker died in prison on June 16, 1692.

From June 30 through early July, grand juries endorsed indictments against Sarah Good, Elizabeth Howe, Susannah Martin, Elizabeth Proctor, John Proctor, Martha Carrier, Sarah Wildes and Dorcas Hoar. Sarah Good, Elizabeth Howe, Susannah Martin and Sarah Wildes, along with Rebecca Nurse, went to trial at this time, where they were found guilty. All five women were executed by hanging on July 19, 1692. In mid-July, the constable in Andover invited the afflicted girls from Salem Village to visit with his wife to try to determine who was causing her afflictions. Ann Foster, her daughter Mary Lacey Sr., and granddaughter Mary Lacey Jr. all confessed to being witches. Anthony Checkley was appointed by Governor Phips to replace Thomas Newton as the Crown's Attorney when Newton took an appointment in New Hampshire.

In August, grand juries indicted George Burroughs

George Burroughs ( 1650August 19, 1692) was an American religious leader who was the only minister executed for witchcraft during the course of the Salem witch trials. He is best known for reciting the Lord's Prayer during his execution, some ...

, Mary Eastey

Mary Towne Eastey (also spelled Esty, Easty, Estey, Eastick, Eastie, or Estye) ( bap. August 24, 1634 – September 22, 1692) was a defendant in the Salem witch trials in colonial Massachusetts. She was executed by hanging in Salem in 1692.

...

, Martha Corey and George Jacobs Sr. Trial juries convicted Martha Carrier, George Jacobs Sr., George Burroughs, John Willard, Elizabeth Proctor, and John Proctor. Elizabeth Proctor was given a temporary stay of execution because she was pregnant. On August 19, 1692, Martha Carrier, George Jacobs Sr., George Burroughs, John Willard, and John Proctor were executed.

September 1692

In September, grand juries indicted 18 more people. The grand jury failed to indict William Proctor, who was re-arrested on new charges. On September 19, 1692, Giles Corey refused to plead at trial, and was killed by ''

In September, grand juries indicted 18 more people. The grand jury failed to indict William Proctor, who was re-arrested on new charges. On September 19, 1692, Giles Corey refused to plead at trial, and was killed by ''peine forte et dure

' (Law French for "hard and forceful punishment") was a method of torture formerly used in the common law legal system, in which a defendant who refused to plead ("stood mute") would be subjected to having heavier and heavier stones placed upon ...

'', a form of torture in which the subject is pressed beneath an increasingly heavy load of stones, in an attempt to make him enter a plea. Four pleaded guilty and 11 others were tried and found guilty.

On September 20, Cotton Mather wrote to Stephen Sewall: "That I may be the more capable to assist in lifting up a standard against the infernal enemy", requesting "a narrative of the evidence given in at the trials of half a dozen, or if you please, a dozen, of the principal witches that have been condemned." On September 22, 1692, eight more persons were executed, "After Execution Mr. Noyes turning him to the Bodies, said, what a sad thing it is to see Eight Firebrands of Hell hanging there."

Dorcas Hoar was given a temporary reprieve, with the support of several ministers, to make a confession of being a witch. Mary Bradbury (aged 77) managed to escape with the help of family and friends. Abigail Faulkner Sr. was pregnant and given a temporary reprieve (some reports from that era say that Abigail's reprieve later became a stay of charges).

Mather quickly completed his account of the trials, ''Wonders of the Invisible World'' and it was given to Phips when he returned from the fighting in Maine in early October. Burr says both Phips' letter and Mather's manuscript "must have gone to London by the same ship" in mid-October.

On October 29, Judge Sewall wrote, "the Court of Oyer and Terminer count themselves thereby dismissed ... asked whether the Court of Oyer and Terminer should sit, expressing some fear of Inconvenience by its fall, heGovernour said it must fall". Perhaps by coincidence, Governor Phips' own wife, Lady Mary Phips, was among those who had been "called out upon" around this time. After Phips' order, there were no more executions.

Superior Court of Judicature, 1693

In January 1693, the new Superior Court of Judicature, Court of Assize and General Gaol ailDelivery convened in Salem, Essex County, again headed by William Stoughton, as Chief Justice, with Anthony Checkley continuing as the Attorney General, and Jonathan Elatson as Clerk of the Court. The first five cases tried in January 1693 were of the five people who had been indicted but not tried in September: Sarah Buckley, Margaret Jacobs, Rebecca Jacobs, Mary Whittredge (or Witheridge) and Job Tookey. All were found not guilty. Grand juries were held for many of those remaining in jail. Charges were dismissed against many, but 16 more people were indicted and tried, three of whom were found guilty: Elizabeth Johnson Jr., Sarah Wardwell, and Mary Post. When Stoughton wrote the warrants for the execution of these three and others remaining from the previous court, Governor Phips issued pardons, sparing their lives. In late January/early February, the Court sat again in Charlestown, Middlesex County, and held grand juries and tried five people: Sarah Cole (of Lynn), Lydia Dustin and Sarah Dustin, Mary Taylor and Mary Toothaker. All were found not guilty but were not released until they paid their jail fees. Lydia Dustin died in jail on March 10, 1693. At the end of April, the Court convened in Boston, Suffolk County, and cleared Capt. John Alden by proclamation. It heard charges against a servant girl, Mary Watkins, for falsely accusing her mistress of witchcraft. In May, the Court convened in Ipswich, Essex County, and held a variety of grand juries. They dismissed charges against all but five people. Susannah Post, Eunice Frye, Mary Bridges Jr., Mary Barker and William Barker Jr. were all found not guilty at trial, finally putting an end to the series of trials and executions.Legal procedures

Overview

After someone concluded that a loss, illness, or death had been caused by witchcraft, the accuser entered a complaint against the alleged witch with the local magistrates. If the complaint was deemed credible, the magistrates had the person arrested and brought in for a public examination—essentially an interrogation where the magistrates pressed the accused to confess. If the magistrates at this local level were satisfied that the complaint was well-founded, the prisoner was handed over to be dealt with by a superior court. In 1692, the magistrates opted to wait for the arrival of the new charter and governor, who would establish a Court of Oyer and Terminer to handle these cases. The next step, at the superior court level, was to summon witnesses before a grand jury. A person could be indicted on charges of afflicting with witchcraft, or for making an unlawful covenant with the Devil. Once indicted, the defendant went to trial, sometimes on the same day, as in the case of the first person indicted and tried on June 2, Bridget Bishop, who was executed eight days later, on June 10, 1692. There were four execution dates, with one person executed on June 10, 1692, five executed on July 19, 1692 (Sarah Good, Rebecca Nurse, Susannah Martin, Elizabeth Howe and Sarah Wildes), another five executed on August 19, 1692 (Martha Carrier, John Willard, George Burroughs, George Jacobs Sr., and John Proctor), and eight on September 22, 1692 (Mary Eastey, Martha Corey, Ann Pudeator, Samuel Wardwell, Mary Parker, Alice Parker, Wilmot Redd and Margaret Scott). Several others, including Elizabeth (Bassett) Proctor and Abigail Faulkner, were convicted but given temporary reprieves because they were pregnant. Five other women were convicted in 1692, but the death sentence was never carried out: Mary Bradbury (in absentia), Ann Foster (who later died in prison), Mary Lacey Sr. (Foster's daughter), Dorcas Hoar and Abigail Hobbs. Giles Corey, an 81-year-old farmer from the southeast end of Salem (called Salem Farms), refused to enter a plea when he came to trial in September. The judges applied an archaic form of punishment called ''peine forte et dure,'' in which stones were piled on his chest until he could no longer breathe. After two days of ''peine fort et dure,'' Corey died without entering a plea.Boyer, p. 8. His refusal to plead is usually explained as a way of preventing his estate from being confiscated by the Crown, but, according to historian Chadwick Hansen, much of Corey's property had already been seized, and he had made a will in prison: "His death was a protest ... against the methods of the court". A contemporary critic of the trials,

Giles Corey, an 81-year-old farmer from the southeast end of Salem (called Salem Farms), refused to enter a plea when he came to trial in September. The judges applied an archaic form of punishment called ''peine forte et dure,'' in which stones were piled on his chest until he could no longer breathe. After two days of ''peine fort et dure,'' Corey died without entering a plea.Boyer, p. 8. His refusal to plead is usually explained as a way of preventing his estate from being confiscated by the Crown, but, according to historian Chadwick Hansen, much of Corey's property had already been seized, and he had made a will in prison: "His death was a protest ... against the methods of the court". A contemporary critic of the trials, Robert Calef

Robert Calef (baptized 2 November 1648 – 13 April 1719) was a cloth merchant in colonial Boston. He was the author o''More Wonders of the Invisible World'' a book composed throughout the mid-1690s denouncing the recent Salem witch trials of 1692 ...

, wrote, "Giles Corey pleaded not Guilty to his Indictment, but would not put himself upon Tryal by the Jury (they having cleared none upon Tryal) and knowing there would be the same Witnesses against him, rather chose to undergo what Death they would put him to."

As convicted witches, Rebecca Nurse and Martha Corey had been excommunicated from their churches and denied proper burials. As soon as the bodies of the accused were cut down from the trees, they were thrown into a shallow grave, and the crowd dispersed. Oral history claims that the families of the dead reclaimed their bodies after dark and buried them in unmarked graves on family property. The record books of the time do not note the deaths of any of those executed.

Spectral evidence

Much, but not all, of the evidence used against the accused was ''

Much, but not all, of the evidence used against the accused was ''spectral evidence Spectral evidence is a form of legal evidence based upon the testimony of those who claim to have experienced visions.

Such testimony was frequently given during the witch trials of the 16th and 17th centuries. The alleged victims of witchcraft w ...

,'' or the testimony of the afflicted who claimed to see the apparition or the shape of the person who was allegedly afflicting them. The theological dispute that ensued about the use of this evidence was based on whether a person had to give permission to the Devil for his/her shape to be used to afflict. Opponents claimed that the Devil was able to use anyone's shape to afflict people, but the Court contended that the Devil could not use a person's shape without that person's permission; therefore, when the afflicted claimed to see the apparition of a specific person, that was accepted as evidence that the accused had been complicit with the Devil.

Cotton Mather's ''The Wonders of the Invisible World'' was written with the purpose to show how careful the court was in managing the trials. Unfortunately the work did not get released until after the trials had already ended. In his book, Mather explained how he felt spectral evidence was presumptive and that it alone was not enough to warrant a conviction. Robert Calef, a strong critic of Cotton Mather, stated in his own book titled ''More Wonders of the Invisible World'' that by confessing, an accused would not be brought to trial, such as in the cases of Tituba and Dorcas Good.

Increase Mather

Increase Mather (; June 21, 1639 Old Style – August 23, 1723 Old Style) was a New England Puritan clergyman in the Massachusetts Bay Colony and president of Harvard College for twenty years (1681–1701). He was influential in the admini ...

and other ministers sent a letter to the Court, "The Return of Several Ministers Consulted", urging the magistrates not to convict on spectral evidence alone. (The court later ruled that spectral evidence was inadmissible, which caused a dramatic reduction in the rate of convictions and may have hastened the end of the trials.) A copy of this letter was printed in Increase Mather

Increase Mather (; June 21, 1639 Old Style – August 23, 1723 Old Style) was a New England Puritan clergyman in the Massachusetts Bay Colony and president of Harvard College for twenty years (1681–1701). He was influential in the admini ...

's ''Cases of Conscience'', published in 1693. The publication ''A Tryal of Witches'', related to the 1662 Bury St Edmunds witch trial, was used by the magistrates at Salem when looking for a precedent in allowing spectral evidence. Since the jurist Sir Matthew Hale

Sir Matthew Hale (1 November 1609 – 25 December 1676) was an influential English barrister, judge and jurist most noted for his treatise '' Historia Placitorum Coronæ'', or ''The History of the Pleas of the Crown''.

Born to a barrister an ...

had permitted this evidence, supported by the eminent philosopher, physician and author Thomas Browne

Sir Thomas Browne (; 19 October 160519 October 1682) was an English polymath and author of varied works which reveal his wide learning in diverse fields including science and medicine, religion and the esoteric. His writings display a deep curi ...

, to be used in the Bury St Edmunds witch trial and the accusations against two Lowestoft

Lowestoft ( ) is a coastal town and civil parish in the East Suffolk (district), East Suffolk district of Suffolk, England.OS Explorer Map OL40: The Broads: (1:25 000) : . As the List of extreme points of the United Kingdom, most easterly UK se ...

women, the colonial magistrates also accepted its validity and their trials proceeded.

Witch cake

According to a March 27, 1692 entry by Parris in the ''Records of the Salem-Village Church'', a church member and close neighbor of Rev. Parris, Mary Sibley (aunt of

According to a March 27, 1692 entry by Parris in the ''Records of the Salem-Village Church'', a church member and close neighbor of Rev. Parris, Mary Sibley (aunt of Mary Walcott

Mary Walcott (July 5, 1675 – 1752) was one of the "afflicted" girls called as a witness at the Salem witch trials in early 1692-93.

Life

Born July 5, 1675, she was the daughter of Captain Jonathan Walcott (1639–1699), and his wife, Mary Sibl ...

), directed John Indian, a man enslaved by Parris, to make a ''witch cake.''Salem VillagChurch Records, pp. 10–12.