Sagan's number on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Carl Edward Sagan (; ; November 9, 1934December 20, 1996) was an American

Initially an assistant professor at Harvard, Sagan later moved to

astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses their studies on a specific question or field outside the scope of Earth. They observe astronomical objects such as stars, planets, moons, comets and galaxies – in either ...

, planetary scientist

Planetary science (or more rarely, planetology) is the scientific study of planets (including Earth), celestial bodies (such as moons, asteroids, comets) and planetary systems (in particular those of the Solar System) and the processes of their ...

, cosmologist

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', and in 1731 taken up in Latin by German philosopher ...

, astrophysicist, astrobiologist

Astrobiology, and the related field of exobiology, is an interdisciplinary scientific field that studies the origins, early evolution, distribution, and future of life in the universe. Astrobiology is the multidisciplinary field that inves ...

, author, and science communicator

Science communication is the practice of informing, educating, raising awareness of science-related topics, and increasing the sense of wonder about scientific discoveries and arguments. Science communicators and audiences are ambiguously def ...

. His best known scientific contribution is research on extraterrestrial life, including experimental demonstration of the production of amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha a ...

s from basic chemicals by radiation. Sagan assembled the first physical messages sent into space, the Pioneer plaque

The Pioneer plaques are a pair of gold-anodized aluminum plaques that were placed on board the 1972 ''Pioneer 10'' and 1973 ''Pioneer 11'' spacecraft, featuring a pictorial message, in case either ''Pioneer 10'' or ''11'' is intercepted by inte ...

and the Voyager Golden Record

The Voyager Golden Records are two phonograph records that were included aboard both Voyager spacecraft launched in 1977. The records contain sounds and images selected to portray the diversity of life and culture on Earth, and are intended for ...

, universal messages that could potentially be understood by any extraterrestrial intelligence that might find them. Sagan argued the hypothesis, accepted since, that the high surface temperatures of Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never f ...

can be attributed to, and calculated using, the greenhouse effect

The greenhouse effect is a process that occurs when energy from a planet's host star goes through the planet's atmosphere and heats the planet's surface, but greenhouse gases in the atmosphere prevent some of the heat from returning directly ...

.Extract of page 14Initially an assistant professor at Harvard, Sagan later moved to

Cornell

Cornell University is a private statutory land-grant research university based in Ithaca, New York. It is a member of the Ivy League. Founded in 1865 by Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, Cornell was founded with the intention to teach a ...

where he would spend the majority of his career. Sagan published more than 600 scientific papers and articles and was author, co-author or editor of more than 20 books. He wrote many popular science books, such as ''The Dragons of Eden

''The Dragons of Eden: Speculations on the Evolution of Human Intelligence'' is a 1977 book by Carl Sagan, in which the author combines the fields of anthropology, evolutionary biology, psychology, and computer science to give a perspective on ho ...

'', ''Broca's Brain

''Broca's Brain: Reflections on the Romance of Science'' is a 1979 book by the astrophysicist Carl Sagan. Its chapters were originally articles published between 1974 and 1979 in various magazines, including ''The Atlantic Monthly'', ''The New R ...

'', ''Pale Blue Dot

''Pale Blue Dot'' is a photograph of planet Earth taken on February 14, 1990, by the ''Voyager 1'' space probe from a record distance of about kilometers ( miles, 40.5 AU), as part of that day's ''Family Portrait'' series of images of the ...

'' and narrated and co-wrote the award-winning 1980 television series '' Cosmos: A Personal Voyage''. The most widely watched series in the history of American public television

Public broadcasting involves radio, television and other electronic media outlets whose primary mission is public service. Public broadcasters receive funding from diverse sources including license fees, individual contributions, public financing ...

, ''Cosmos'' has been seen by at least 500 million people in 60 countries. The book ''Cosmos

The cosmos (, ) is another name for the Universe. Using the word ''cosmos'' implies viewing the universe as a complex and orderly system or entity.

The cosmos, and understandings of the reasons for its existence and significance, are studied in ...

'' was published to accompany the series. He also wrote the 1985 science fiction novel ''Contact

Contact may refer to:

Interaction Physical interaction

* Contact (geology), a common geological feature

* Contact lens or contact, a lens placed on the eye

* Contact sport, a sport in which players make contact with other players or objects

* ...

'', the basis for a 1997 film of the same name. His papers, containing 595,000 items, are archived at The Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The library ...

.

Sagan advocated scientific skeptical inquiry and the scientific method

The scientific method is an empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article history of scientific ...

, pioneered exobiology

Astrobiology, and the related field of exobiology, is an interdisciplinary scientific field that studies the origins, early evolution, distribution, and future of life in the universe. Astrobiology is the multidisciplinary field that investig ...

and promoted the Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence (SETI

The search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI) is a collective term for scientific searches for intelligent extraterrestrial life, for example, monitoring electromagnetic radiation for signs of transmissions from civilizations on other pl ...

). He spent most of his career as a professor of astronomy at Cornell University

Cornell University is a private statutory land-grant research university based in Ithaca, New York. It is a member of the Ivy League. Founded in 1865 by Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, Cornell was founded with the intention to tea ...

, where he directed the Laboratory for Planetary Studies. Sagan and his works received numerous awards and honors, including the NASA Distinguished Public Service Medal

The NASA Distinguished Public Service Medal is an award similar to the NASA Distinguished Service Medal, but awarded to non-government personnel. This is the highest honor NASA awards to anyone who was not a government employee when the service ...

, the National Academy of Sciences Public Welfare Medal The Public Welfare Medal is awarded by the U.S. National Academy of Sciences "in recognition of distinguished contributions in the application of science to the public welfare." It is the most prestigious honor conferred by the academy. First award ...

, the Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction

The Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction is one of the seven American Pulitzer Prizes that are awarded annually for the "Letters, Drama, and Music" category. The award is given to a nonfiction book written by an American author and published duri ...

for his book ''The Dragons of Eden'', and, regarding ''Cosmos: A Personal Voyage'', two Emmy Awards, the Peabody Award, and the Hugo Award. He married three times and had five children. After developing myelodysplasia

A myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) is one of a group of cancers in which immature blood cells in the bone marrow do not mature, and as a result, do not develop into healthy blood cells. Early on, no symptoms typically are seen. Later, symptoms may ...

, Sagan died of pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severi ...

at the age of 62, on December 20, 1996.

Early life and education

Sagan was born in theBensonhurst

Bensonhurst is a residential neighborhood in the southwestern section of the New York City borough of Brooklyn. The neighborhood is bordered on the northwest by 14th Avenue, on the northeast by 60th Street, on the southeast by Avenue P and 22n ...

neighborhood of Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

, New York, on November 9, 1934. Poundstone 1999, pp. 363–364, 374–375. His father, Samuel Sagan, was an immigrant garment worker from Kamianets-Podilskyi

Kamianets-Podilskyi ( uk, Ка́м'яне́ць-Поді́льський, russian: Каменец-Подольский, Kamenets-Podolskiy, pl, Kamieniec Podolski, ro, Camenița, yi, קאַמענעץ־פּאָדאָלסק / קאַמעניץ, ...

, then in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

, in today's Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

. His mother, Rachel Molly Gruber, was a housewife from New York. Carl was named in honor of Rachel's biological mother

]

A mother is the female parent of a child. A woman may be considered a mother by virtue of having given birth, by raising a child who may or may not be her biological offspring, or by supplying her ovum for fertilisation in the case of gesta ...

, Chaiya Clara, in Sagan's words, "the mother she never knew", #Davidson, Davidson 1999. because she died while giving birth to her second child. Rachel's father remarried a woman named Rose. According to Carol (Carl's sister), Rachel "never accepted Rose as her mother. She knew she wasn't her birth mother... She was a rather rebellious child and young adult ... 'emancipated woman', we'd call her now."

The family lived in a modest apartment near the Atlantic Ocean, in Bensonhurst

Bensonhurst is a residential neighborhood in the southwestern section of the New York City borough of Brooklyn. The neighborhood is bordered on the northwest by 14th Avenue, on the northeast by 60th Street, on the southeast by Avenue P and 22n ...

, a Brooklyn neighborhood. According to Sagan, they were Reform Jews

Reform Judaism, also known as Liberal Judaism or Progressive Judaism, is a major Jewish denomination that emphasizes the evolving nature of Judaism, the superiority of its ethical aspects to its ceremonial ones, and belief in a continuous searc ...

, the most liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

of North American Judaism's four main groups. Carl and his sister agreed that their father was not especially religious, but that their mother "definitely believed in God, and was active in the temple; ... and served only kosher meat". During the depths of the Depression, his father worked as a theater usher.

According to biographer Keay Davidson, Sagan's "inner war" was a result of his close relationship with both of his parents, who were in many ways "opposites". Sagan traced his later analytical urges to his mother, a woman who had been extremely poor as a child in New York City during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and the 1920s. As a young woman, she had held her own intellectual ambitions, but they were frustrated by social restrictions: her poverty, her status as a woman and a wife, and her Jewish ethnicity

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

. Davidson notes that she therefore "worshipped her only son, Carl. He would fulfill her unfulfilled dreams."

However, he claimed that his sense of wonder came from his father, who in his free time gave apples to the poor or helped soothe labor-management tensions within New York's garment industry. Although he was awed by Carl's intellectual abilities, he took his son's inquisitiveness in stride and saw it as part of his growing up. In his later years as a writer and scientist, Sagan would often draw on his childhood memories to illustrate scientific points, as he did in his book '' Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors''. Sagan describes his parents' influence on his later thinking: Spangenburg & Moser 2004, pp. 2–5.

Sagan recalls that one of his most defining moments was when his parents took him to the 1939 New York World's Fair when he was four years old. The exhibits became a turning point in his life. He later recalled the moving map of the '' America of Tomorrow'' exhibit: "It showed beautiful highways and cloverleaves and little General Motors cars all carrying people to skyscrapers, buildings with lovely spires, flying buttresses—and it looked great!" At other exhibits, he remembered how a flashlight that shone on a photoelectric cell

A solar cell, or photovoltaic cell, is an electronic device that converts the energy of light directly into electricity by the photovoltaic effect, which is a physical and chemical phenomenon.

created a crackling sound, and how the sound from a tuning fork

A tuning fork is an acoustic resonator in the form of a two-pronged fork with the prongs ( tines) formed from a U-shaped bar of elastic metal (usually steel). It resonates at a specific constant pitch when set vibrating by striking it agains ...

became a wave on an oscilloscope. He also witnessed the future media technology that would replace radio: television. Sagan wrote:

He also saw one of the Fair's most publicized events, the burial of a time capsule

A time capsule is a historic cache of goods or information, usually intended as a deliberate method of communication with future people, and to help future archaeologists, anthropologists, or historians. The preservation of holy relics dates ...

at Flushing Meadows

Flushing may refer to:

Places

* Flushing, Cornwall, a village in the United Kingdom

* Flushing, Queens, New York City

** Flushing Bay, a bay off the north shore of Queens

** Flushing Chinatown (法拉盛華埠), a community in Queens

** Flushin ...

, which contained mementos of the 1930s to be recovered by Earth's descendants in a future millennium. "The time capsule thrilled Carl", writes Davidson. As an adult, Sagan and his colleagues would create similar time capsules—capsules that would be sent out into the galaxy; these were the Pioneer plaque

The Pioneer plaques are a pair of gold-anodized aluminum plaques that were placed on board the 1972 ''Pioneer 10'' and 1973 ''Pioneer 11'' spacecraft, featuring a pictorial message, in case either ''Pioneer 10'' or ''11'' is intercepted by inte ...

and the ''Voyager Golden Record

The Voyager Golden Records are two phonograph records that were included aboard both Voyager spacecraft launched in 1977. The records contain sounds and images selected to portray the diversity of life and culture on Earth, and are intended for ...

'' précis, all of which were spinoffs of Sagan's memories of the World's Fair.

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

Sagan's family worried about the fate of their European relatives. Sagan, however, was generally unaware of the details of the ongoing war. He wrote, "Sure, we had relatives who were caught up in the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

. Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

was not a popular fellow in our household... But on the other hand, I was fairly insulated from the horrors of the war." His sister, Carol, said that their mother "above all wanted to protect Carl... She had an extraordinarily difficult time dealing with World War II and the Holocaust." Sagan's book ''The Demon-Haunted World

''The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark'' is a 1995 book by the astrophysicist Carl Sagan and co-authored by Ann Druyan, in which the authors aim to explain the scientific method to laypeople and to encourage people to learn c ...

'' (1996) included his memories of this conflicted period, when his family dealt with the realities of the war in Europe but tried to prevent it from undermining his optimistic spirit.

Inquisitiveness about nature

Soon after entering elementary school he began to express a strong inquisitiveness about nature. Sagan recalled taking his first trips to the public library alone, at the age of five, when his mother got him a library card. He wanted to learn what stars were, since none of his friends or their parents could give him a clear answer: At about age six or seven, he and a close friend took trips to the American Museum of Natural History across the East River inManhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

. While there, they went to the Hayden Planetarium

The Rose Center for Earth and Space is a part of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. The Center's complete name is The Frederick Phineas and Sandra Priest Rose Center for Earth and Space. The main entrance is located on the n ...

and walked around the museum's exhibits of space

Space is the boundless three-dimensional extent in which objects and events have relative position and direction. In classical physics, physical space is often conceived in three linear dimensions, although modern physicists usually cons ...

objects, such as meteorites, and displays of dinosaurs and animals in natural settings. Sagan writes about those visits:

His parents helped nurture his growing interest in science by buying him chemistry sets and reading materials. His interest in space, however, was his primary focus, especially after reading science fiction stories by writers such as H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells"Wells, H. G."

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

Edgar Rice Burroughs, which stirred his imagination about life on other planets such as

Sagan had lived in Bensonhurst, where he went to David A. Boody Junior High School. He had his bar mitzvah in Bensonhurst when he turned 13. The following year, 1948, his family moved to the town of

Sagan had lived in Bensonhurst, where he went to David A. Boody Junior High School. He had his bar mitzvah in Bensonhurst when he turned 13. The following year, 1948, his family moved to the town of

Sagan attended the

Sagan attended the

Sagan's ability to convey his ideas allowed many people to understand the cosmos better—simultaneously emphasizing the value and worthiness of the human race, and the relative insignificance of the Earth in comparison to the

Sagan's ability to convey his ideas allowed many people to understand the cosmos better—simultaneously emphasizing the value and worthiness of the human race, and the relative insignificance of the Earth in comparison to the  At the height of the Cold War, Sagan became involved in

At the height of the Cold War, Sagan became involved in  Sagan wrote a sequel to ''Cosmos'', '' Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space'', which was selected as a notable book of 1995 by ''

Sagan wrote a sequel to ''Cosmos'', '' Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space'', which was selected as a notable book of 1995 by '' In the televised debate, Sagan argued that the effects of the smoke would be similar to the effects of a

In the televised debate, Sagan argued that the effects of the smoke would be similar to the effects of a

In March 1983, Reagan announced the Strategic Defense Initiative—a multibillion-dollar project to develop a comprehensive defense against attack by

In March 1983, Reagan announced the Strategic Defense Initiative—a multibillion-dollar project to develop a comprehensive defense against attack by

Sagan also commented on Christianity and the

Sagan also commented on Christianity and the  Sagan is also widely regarded as a

Sagan is also widely regarded as a

After having

After having

* Annual Award for Television Excellence—1981—

* Annual Award for Television Excellence—1981—

David Morrison, "Carl Sagan", Biographical Memoirs of the National Academy of Sciences (2014)Sagan interviewed by Ted Turner

''CNN'', 1989, video: 44 minutes.

BBC Radio program "Great Lives" on Carl Sagan's life

"A man whose time has come"

��Interview with Carl Sagan by

"Carl Sagan's Life and Legacy as Scientist, Teacher, and Skeptic"

by David Morrison, Committee for Skeptical Inquiry

FBI Records: The Vault – Carl Sagan

at fbi.gov

"NASA Technical Reports Server (NTRS) 19630011050: Direct Contact Among Galactic Civilizations by Relativistic Interstellar Spaceflight"

Carl Sagan, when he was at Stanford University, in 1962, produced a controversial paper funded by a NASA research grant that concludes ancient alien intervention may have sparked human civilization.

Scientist of the Day-Carl Sagan

at

demonstrates

how Eratosthenes determined that the Earth was round and the approximate circumference of the earth {{DEFAULTSORT:Sagan, Carl 1934 births 1996 deaths 20th-century American astronomers 20th-century American male writers 20th-century American novelists 20th-century naturalists American agnostics American anti–nuclear weapons activists American anti–Vietnam War activists American astrophysicists American cannabis activists American cosmologists American humanists American male non-fiction writers American male novelists American naturalists American nature writers American pacifists American people of Russian-Jewish descent American people of Ukrainian-Jewish descent American science fiction writers American science writers American skeptics American social commentators American UFO writers Articles containing video clips Astrobiologists Astrochemists Burials in New York (state) Cornell University faculty Critics of alternative medicine Critics of creationism Critics of parapsychology Critics of religions Cultural critics Deaths from myelodysplastic syndrome Deaths from pneumonia in Washington (state) Fellows of the American Physical Society Grand Crosses of the Order of Saint James of the Sword Harvard University faculty Hugo Award-winning writers Interstellar messages Jewish activists Jewish agnostics Jewish American scientists Jewish astronomers Jewish skeptics Members of the American Philosophical Society Novelists from New York (state) Pantheists People associated with the American Museum of Natural History People from Bensonhurst, Brooklyn Planetary scientists Presidents of The Planetary Society Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction winners Rahway High School alumni Sagan family Science communicators Scientists from New York (state) Search for extraterrestrial intelligence Secular humanists Social critics Space advocates Spinozists University of California, Berkeley fellows University of Chicago alumni Writers about religion and science Writers from Brooklyn

Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Roman god of war. Mars is a terrestrial planet with a thin at ...

. According to biographer Ray Spangenburg, these early years as Sagan tried to understand the mysteries of the planets became a "driving force in his life, a continual spark to his intellect, and a quest that would never be forgotten".

In 1947 he discovered '' Astounding Science Fiction'' magazine, which introduced him to more hard science fiction

Hard science fiction is a category of science fiction characterized by concern for scientific accuracy and logic. The term was first used in print in 1957 by P. Schuyler Miller in a review of John W. Campbell's ''Islands of Space'' in the Novemb ...

speculations than those in Burroughs's novels. That same year inaugurated the "flying saucer

A flying saucer (also referred to as "a flying disc") is a descriptive term for a type of flying craft having a disc or saucer-shaped body, commonly used generically to refer to an anomalous flying object. The term was coined in 1947 but has g ...

" mass hysteria

Mass psychogenic illness (MPI), also called mass sociogenic illness, mass psychogenic disorder, epidemic hysteria, or mass hysteria, involves the spread of illness symptoms through a population where there is no infectious agent responsible for c ...

with the young Carl suspecting that the "discs" might be alien spaceships.

High-school years

Sagan had lived in Bensonhurst, where he went to David A. Boody Junior High School. He had his bar mitzvah in Bensonhurst when he turned 13. The following year, 1948, his family moved to the town of

Sagan had lived in Bensonhurst, where he went to David A. Boody Junior High School. He had his bar mitzvah in Bensonhurst when he turned 13. The following year, 1948, his family moved to the town of Rahway, New Jersey

Rahway () is a city in southern Union County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. A bedroom community of New York City, it is centrally located in the Rahway Valley region, in the New York metropolitan area. The city is southwest of Manhattan ...

, for his father's work, where Sagan then entered Rahway High School

Rahway High School is a four-year public high school that serves students in ninth through twelfth grades from Rahway, in Union County, New Jersey, United States, operating as the lone secondary school of the Rahway Public Schools. The high s ...

. He graduated in 1951. Rahway was an older semi-industrial town.

Sagan was a straight-A student but was bored due to unchallenging classes and uninspiring teachers. His teachers realized this and tried to convince his parents to send him to a private school, the administrator telling them, "This kid ought to go to a school for gifted children, he has something really remarkable." However, his parents could not afford it.

Sagan was made president of the school's chemistry club, and at home he set up his own laboratory. He taught himself about molecules by making cardboard cutouts to help him visualize how molecules were formed: "I found that about as interesting as doing hemicalexperiments," he said. Sagan remained mostly interested in astronomy as a hobby and in his junior year made it a career goal after he learned that astronomers were paid for doing what he always enjoyed: "That was a splendid day—when I began to suspect that if I tried hard I could do astronomy full-time, not just part-time."

Before the end of high school, he entered an essay contest in which he posed the question of whether human contact with advanced life forms from another planet might be as disastrous for people on Earth as it was for Native Americans when they first had contact with Europeans. Poundstone 1999, p. 15. The subject was considered controversial, but his rhetorical skill won over the judges, and they awarded him first prize. By graduation, his classmates had voted him "most likely to succeed" and put him in line to be valedictorian.

University education

Sagan attended the

Sagan attended the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chic ...

, which was one of the few colleges he applied to that would, despite his excellent high-school grades, consider admitting a 16-year-old. Its chancellor, Robert Maynard Hutchins

Robert Maynard Hutchins (January 17, 1899 – May 14, 1977) was an American educational philosopher. He was president (1929–1945) and chancellor (1945–1951) of the University of Chicago, and earlier dean of Yale Law School (1927–1929). His& ...

, had recently retooled the undergraduate College of the University of Chicago

The College of the University of Chicago is the university's sole undergraduate institution and one of its oldest components, emerging contemporaneously with the university's Hyde Park campus in 1892. Instruction is provided by faculty from acros ...

into an "ideal meritocracy" built on Great Books

A classic is a book accepted as being exemplary or particularly noteworthy. What makes a book "classic" is a concern that has occurred to various authors ranging from Italo Calvino to Mark Twain and the related questions of "Why Read the Cl ...

, Socratic dialogue, comprehensive examination

In higher education, a comprehensive examination (or comprehensive exam or exams), often abbreviated as "comps", is a specific type of examination that must be completed by graduate students in some disciplines and courses of study, and also by un ...

s and early entrance to college with no age requirement. Poundstone 1999, p. 14. The school also employed a number of the nation's leading scientists, including Enrico Fermi and Edward Teller

Edward Teller ( hu, Teller Ede; January 15, 1908 – September 9, 2003) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist who is known colloquially as "the father of the hydrogen bomb" (see the Teller–Ulam design), although he did not care for ...

, and operated the famous Yerkes Observatory

Yerkes Observatory ( ) is an astronomical observatory located in Williams Bay, Wisconsin, United States. The observatory was operated by the University of Chicago Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics from its founding in 1897 to 2018. Owner ...

.

During his time as an honors program undergraduate

Undergraduate education is education conducted after secondary education and before postgraduate education. It typically includes all postsecondary programs up to the level of a bachelor's degree. For example, in the United States, an entry-le ...

, Sagan worked in the laboratory of the geneticist

A geneticist is a biologist or physician who studies genetics, the science of genes, heredity, and variation of organisms. A geneticist can be employed as a scientist or a lecturer. Geneticists may perform general research on genetic processes ...

H. J. Muller and wrote a thesis on the origins of life

In biology, abiogenesis (from a- 'not' + Greek bios 'life' + genesis 'origin') or the origin of life is the natural process by which life has arisen from non-living matter, such as simple organic compounds. The prevailing scientific hypothes ...

with physical chemist

Physical chemistry is the study of macroscopic and microscopic phenomena in chemical systems in terms of the principles, practices, and concepts of physics such as motion, energy, force, time, thermodynamics, quantum chemistry, statistical mech ...

Harold Urey

Harold Clayton Urey ( ; April 29, 1893 – January 5, 1981) was an American physical chemist whose pioneering work on isotopes earned him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1934 for the discovery of deuterium. He played a significant role in th ...

. Sagan joined the Ryerson Astronomical Society, received a B.A.

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four yea ...

degree in laughingly self-proclaimed "nothing" with general and special honors in 1954, and a B.S.

A Bachelor of Science (BS, BSc, SB, or ScB; from the Latin ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for programs that generally last three to five years.

The first university to admit a student to the degree of Bachelor of Science was the University ...

degree in physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

in 1955. He went on to earn a M.S.

A Master of Science ( la, Magisterii Scientiae; abbreviated MS, M.S., MSc, M.Sc., SM, S.M., ScM or Sc.M.) is a master's degree in the field of science awarded by universities in many countries or a person holding such a degree. In contrast to ...

degree in physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

in 1956, before earning a PhD degree in 1960 with his thesis ''Physical Studies of the Planets'' submitted to the Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics.

He used the summer months of his graduate studies

Postgraduate or graduate education refers to academic or professional degrees, certificates, diplomas, or other qualifications pursued by post-secondary students who have earned an undergraduate (bachelor's) degree.

The organization and stru ...

to work with his dissertation director, planetary scientist

Planetary science (or more rarely, planetology) is the scientific study of planets (including Earth), celestial bodies (such as moons, asteroids, comets) and planetary systems (in particular those of the Solar System) and the processes of their ...

Gerard Kuiper

Gerard Peter Kuiper (; ; born Gerrit Pieter Kuiper; 7 December 1905 – 23 December 1973) was a Dutch astronomer, planetary scientist, selenographer, author and professor. He is the eponymous namesake of the Kuiper belt.

Kuiper is ...

, as well as physicist George Gamow

George Gamow (March 4, 1904 – August 19, 1968), born Georgiy Antonovich Gamov ( uk, Георгій Антонович Гамов, russian: Георгий Антонович Гамов), was a Russian-born Soviet and American polymath, theoret ...

and chemist Melvin Calvin

Melvin Ellis Calvin (April 8, 1912 – January 8, 1997) was an American biochemist known for discovering the Calvin cycle along with Andrew Benson and James Bassham, for which he was awarded the 1961 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. He spent most of h ...

. The title of Sagan's dissertation reflects his shared interests with Kuiper, who throughout the 1950s had been president of the International Astronomical Union

The International Astronomical Union (IAU; french: link=yes, Union astronomique internationale, UAI) is a nongovernmental organisation with the objective of advancing astronomy in all aspects, including promoting astronomical research, outreac ...

's commission on "Physical Studies of Planets and Satellites". In 1958, the two worked on the classified military Project A119

Project A119, also known as A Study of Lunar Research Flights, was a top-secret plan developed in 1958 by the United States Air Force. The aim of the project was to detonate a nuclear bomb on the Moon, which would help in answering some of th ...

, the secret Air Force plan to detonate a nuclear warhead on the Moon.

Sagan had a Top Secret

Classified information is material that a government body deems to be sensitive information that must be protected. Access is restricted by law or regulation to particular groups of people with the necessary security clearance and need to kn ...

clearance at the U.S. Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the air service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part of the United States Army Sign ...

and a Secret

Secrecy is the practice of hiding information from certain individuals or groups who do not have the "need to know", perhaps while sharing it with other individuals. That which is kept hidden is known as the secret.

Secrecy is often controvers ...

clearance with NASA. While working on his doctoral dissertation, Sagan revealed US Government classified titles of two Project A119

Project A119, also known as A Study of Lunar Research Flights, was a top-secret plan developed in 1958 by the United States Air Force. The aim of the project was to detonate a nuclear bomb on the Moon, which would help in answering some of th ...

papers when he applied for a University of California, Berkeley scholarship in 1959. The leak was not publicly revealed until 1999, when it was published in the journal ''Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are ...

''. A follow-up letter to the journal by project leader Leonard Reiffel confirmed Sagan's security leak.

Career and research

From 1960 to 1962 Sagan was aMiller Fellow The Miller Research Fellows program is the central program of the Adolph C. and Mary Sprague Miller Institute for Basic Research in Science on the University of California Berkeley campus. The program constitutes the support of Research Fellows - ...

at the University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of California, it is the state's first land-grant u ...

. Meanwhile, he published an article in 1961 in the journal ''Science'' on the atmosphere of Venus, while also working with NASA's Mariner 2

Mariner 2 (Mariner-Venus 1962), an American space probe to Venus, was the first robotic space probe to conduct a successful planetary encounter. The first successful spacecraft in the NASA Mariner program, it was a simplified version of the B ...

team, and served as a "Planetary Sciences Consultant" to the RAND Corporation.

After the publication of Sagan's ''Science'' article, in 1961 Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of high ...

astronomers Fred Whipple

Fred Lawrence Whipple (November 5, 1906 – August 30, 2004) was an American astronomer, who worked at the Harvard College Observatory for more than 70 years. Amongst his achievements were asteroid and comet discoveries, the " dirty snowball" h ...

and Donald Menzel

Donald Howard Menzel (April 11, 1901 – December 14, 1976) was one of the first theoretical astronomers and astrophysicists in the United States. He discovered the physical properties of the solar chromosphere, the chemistry of stars, the atmos ...

offered Sagan the opportunity to give a colloquium at Harvard and subsequently offered him a lecturer position at the institution. Sagan instead asked to be made an assistant professor, and eventually Whipple and Menzel were able to convince Harvard to offer Sagan the assistant professor position he requested. Sagan lectured, performed research, and advised graduate students at the institution from 1963 until 1968, as well as working at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, also located in Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. As part of the Boston metropolitan area, the cities population of the 2020 U.S. census was 118,403, making it the fourth most populous city in the state, behind Boston ...

.

In 1968, Sagan was denied tenure

Tenure is a category of academic appointment existing in some countries. A tenured post is an indefinite academic appointment that can be terminated only for cause or under extraordinary circumstances, such as financial exigency or program disco ...

at Harvard. He later indicated that the decision was very much unexpected. The tenure denial has been blamed on several factors, including that he focused his interests too broadly across a number of areas (while the norm in academia is to become a renowned expert in a narrow specialty), and perhaps because of his well-publicized scientific advocacy, which some scientists perceived as borrowing the ideas of others for little more than self-promotion. An advisor from his years as an undergraduate student, Harold Urey

Harold Clayton Urey ( ; April 29, 1893 – January 5, 1981) was an American physical chemist whose pioneering work on isotopes earned him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1934 for the discovery of deuterium. He played a significant role in th ...

, wrote a letter to the tenure committee recommending strongly against tenure for Sagan.

Long before the ill-fated tenure process, Cornell University astronomer Thomas Gold

Thomas Gold (May 22, 1920 – June 22, 2004) was an Austrian-born American astrophysicist, a professor of astronomy at Cornell University, a member of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, and a Fellow of the Royal Society (London). Gold was ...

had courted Sagan to move to Ithaca, New York

Ithaca is a city in the Finger Lakes region of New York, United States. Situated on the southern shore of Cayuga Lake, Ithaca is the seat of Tompkins County and the largest community in the Ithaca metropolitan statistical area. It is named ...

, and join the faculty at Cornell. Following the denial of tenure from Harvard, Sagan accepted Gold's offer and remained a faculty member at Cornell for nearly 30 years until his death in 1996. Unlike Harvard, the smaller and more laid-back astronomy department at Cornell welcomed Sagan's growing celebrity status. Following two years as an associate professor, Sagan became a full professor

Professor (commonly abbreviated as Prof.) is an academic rank at universities and other post-secondary education and research institutions in most countries. Literally, ''professor'' derives from Latin as a "person who professes". Professors ...

at Cornell in 1970 and directed the Laboratory for Planetary Studies there. From 1972 to 1981, he was associate director of the Center for Radiophysics and Space Research (CRSR) at Cornell. In 1976, he became the David Duncan Professor of Astronomy and Space Sciences, a position he held for the remainder of his life.

Sagan was associated with the U.S. space program from its inception. From the 1950s onward, he worked as an advisor to NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil List of government space agencies, space program ...

, where one of his duties included briefing the Apollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label= Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label ...

astronauts before their flights to the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width of ...

. Sagan contributed to many of the robotic spacecraft missions that explored the Solar System

The Solar System Capitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Solar ...

, arranging experiments on many of the expeditions. Sagan assembled the first physical message that was sent into space: a gold-plated plaque

Plaque may refer to:

Commemorations or awards

* Commemorative plaque, a plate or tablet fixed to a wall to mark an event, person, etc.

* Memorial Plaque (medallion), issued to next-of-kin of dead British military personnel after World War I

* Pl ...

, attached to the space probe '' Pioneer 10'', launched in 1972. '' Pioneer 11'', also carrying another copy of the plaque, was launched the following year. He continued to refine his designs; the most elaborate message he helped to develop and assemble was the Voyager Golden Record

The Voyager Golden Records are two phonograph records that were included aboard both Voyager spacecraft launched in 1977. The records contain sounds and images selected to portray the diversity of life and culture on Earth, and are intended for ...

, which was sent out with the Voyager space probes in 1977. Sagan often challenged the decisions to fund the Space Shuttle

The Space Shuttle is a retired, partially reusable low Earth orbital spacecraft system operated from 1981 to 2011 by the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) as part of the Space Shuttle program. Its official program ...

and the International Space Station

The International Space Station (ISS) is the largest modular space station currently in low Earth orbit. It is a multinational collaborative project involving five participating space agencies: NASA (United States), Roscosmos (Russia), JAXA ( ...

at the expense of further robotic missions.

Scientific achievements

Former studentDavid Morrison

Lieutenant General David Lindsay Morrison (born 24 May 1956) is a retired senior officer of the Australian Army. He served as Chief of Army from June 2011 until his retirement in May 2015. He was named Australian of the Year for 2016.

Early ...

described Sagan as "an 'idea person' and a master of intuitive physical arguments and ' back of the envelope' calculations", and Gerard Kuiper

Gerard Peter Kuiper (; ; born Gerrit Pieter Kuiper; 7 December 1905 – 23 December 1973) was a Dutch astronomer, planetary scientist, selenographer, author and professor. He is the eponymous namesake of the Kuiper belt.

Kuiper is ...

said that "Some persons work best in specializing on a major program in the laboratory; others are best in liaison between sciences. Dr. Sagan belongs in the latter group."

Sagan's contributions were central to the discovery of the high surface temperatures of the planet Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never f ...

. In the early 1960s no one knew for certain the basic conditions of Venus' surface, and Sagan listed the possibilities in a report later depicted for popularization in a Time Life

Time Life, with sister subsidiaries StarVista Live and Lifestyle Products Group, a holding of Direct Holdings Global LLC, is an American production company and direct marketer conglomerate, that is known for selling books, music, video/DVD, ...

book ''Planets''. His own view was that Venus was dry and very hot as opposed to the balmy paradise others had imagined. He had investigated radio waves from Venus and concluded that there was a surface temperature of . As a visiting scientist to NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory

The Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) is a federally funded research and development center and NASA field center in the City of La Cañada Flintridge, California, United States.

Founded in the 1930s by Caltech researchers, JPL is owned by NASA an ...

, he contributed to the first Mariner

A sailor, seaman, mariner, or seafarer is a person who works aboard a watercraft as part of its crew, and may work in any one of a number of different fields that are related to the operation and maintenance of a ship.

The profession of the ...

missions to Venus, working on the design and management of the project. Mariner 2

Mariner 2 (Mariner-Venus 1962), an American space probe to Venus, was the first robotic space probe to conduct a successful planetary encounter. The first successful spacecraft in the NASA Mariner program, it was a simplified version of the B ...

confirmed his conclusions on the surface conditions of Venus in 1962.

Sagan was among the first to hypothesize that Saturn's moon Titan might possess oceans of liquid compounds on its surface and that Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but slightly less than one-thousandth t ...

's moon Europa might possess subsurface oceans of water. This would make Europa potentially habitable. Europa's subsurface ocean of water was later indirectly confirmed by the spacecraft '' Galileo''. The mystery of Titan's reddish haze was also solved with Sagan's help. The reddish haze was revealed to be due to complex organic molecules constantly raining down onto Titan's surface.

Sagan further contributed insights regarding the atmospheres of Venus and Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but slightly less than one-thousandth t ...

, as well as seasonal changes on Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Roman god of war. Mars is a terrestrial planet with a thin at ...

. He also perceived global warming

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to E ...

as a growing, man-made danger and likened it to the natural development of Venus into a hot, life-hostile planet through a kind of runaway greenhouse effect

A runaway greenhouse effect occurs when a planet's atmosphere contains greenhouse gas in an amount sufficient to block thermal radiation from leaving the planet, preventing the planet from cooling and from having liquid water on its surface. A ...

. He testified to the US Congress in 1985 that the greenhouse effect would change the earth's climate system. Sagan and his Cornell colleague Edwin Ernest Salpeter

Edwin Ernest Salpeter (3 December 1924 – 26 November 2008,) was an Austrian–Australian–American astrophysicist.

Life

Born in Vienna to a Jewish family, Salpeter emigrated from Austria to Australia while in his teens to escape the Nazis. He ...

speculated about life in Jupiter's clouds, given the planet's dense atmospheric composition rich in organic molecules. He studied the observed color variations on Mars' surface and concluded that they were not seasonal or vegetational changes as most believed, but shifts in surface dust caused by windstorms.

Sagan is also known for his research on the possibilities of extraterrestrial life, including experimental demonstration of the production of amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha a ...

s from basic chemicals by radiation.

He is also the 1994 recipient of the Public Welfare Medal The Public Welfare Medal is awarded by the U.S. National Academy of Sciences "in recognition of distinguished contributions in the application of science to the public welfare." It is the most prestigious honor conferred by the academy. First award ...

, the highest award of the National Academy of Sciences for "distinguished contributions in the application of science to the public welfare". He was denied membership in the academy, reportedly because his media activities made him unpopular with many other scientists.

, Sagan is the most cited SETI scientist and one of the most cited planetary scientists.

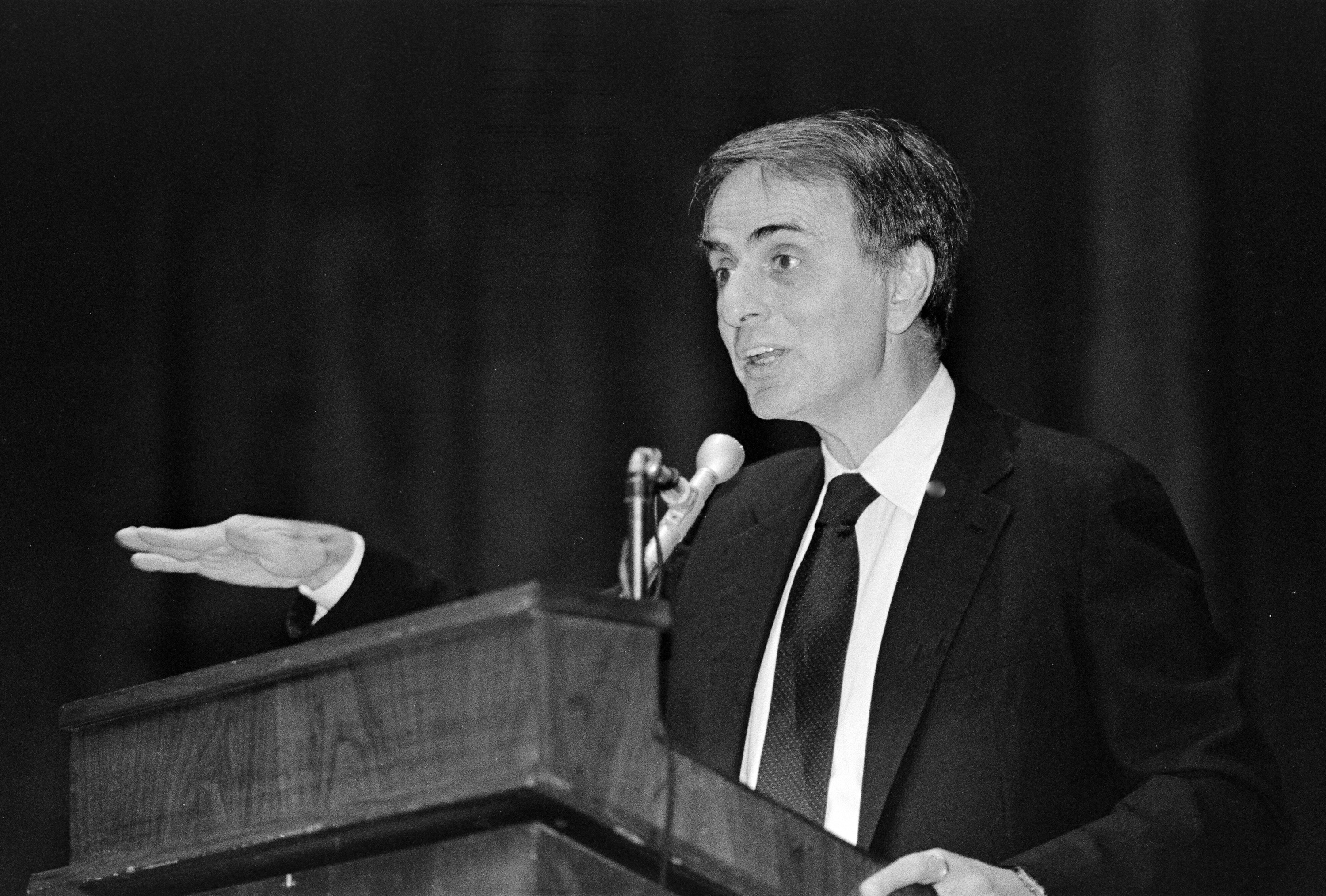

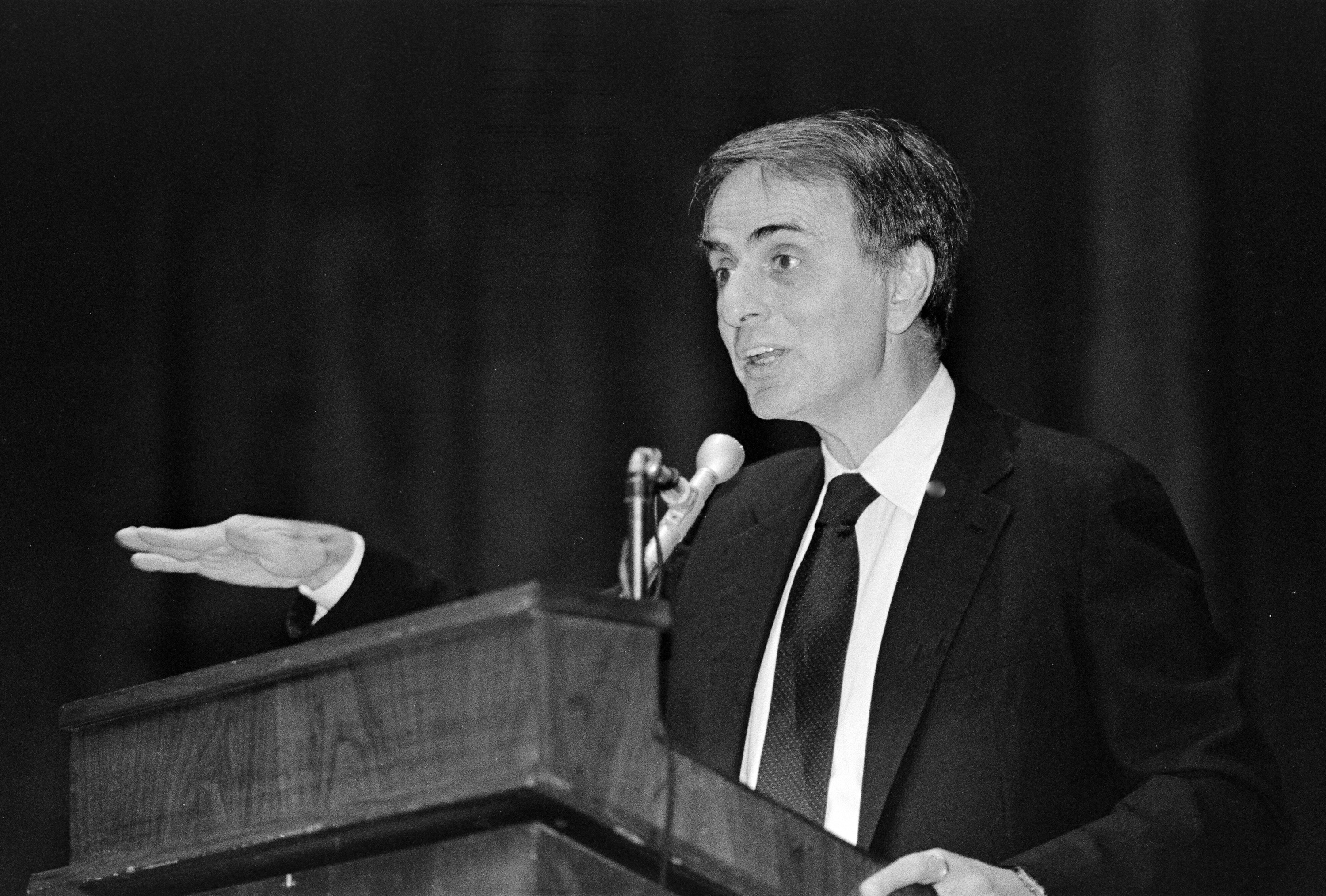

''Cosmos'': popularizing science on TV

In 1980 Sagan co-wrote and narrated the award-winning 13-partPBS

The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) is an American public broadcaster and non-commercial, free-to-air television network based in Arlington, Virginia. PBS is a publicly funded nonprofit organization and the most prominent provider of educat ...

television series '' Cosmos: A Personal Voyage'', which became the most widely watched series in the history of American public television until 1990. The show has been seen by at least 500 million people across 60 countries. The book, ''Cosmos'', written by Sagan, was published to accompany the series.

Because of his earlier popularity as a science writer from his best-selling books, including ''The Dragons of Eden'', which won him a Pulitzer Prize in 1977, he was asked to write and narrate the show. It was targeted to a general audience of viewers, whom Sagan felt had lost interest in science, partly due to a stifled educational system.Browne, Ray Broadus. ''The Guide to United States Popular Culture'', ''Popular Press'' (2001) p. 704.

Each of the 13 episodes was created to focus on a particular subject or person, thereby demonstrating the synergy of the universe. They covered a wide range of scientific subjects including the origin of life

In biology, abiogenesis (from a- 'not' + Greek bios 'life' + genesis 'origin') or the origin of life is the natural process by which life has arisen from non-living matter, such as simple organic compounds. The prevailing scientific hypothes ...

and a perspective of humans' place on Earth.

The show won an Emmy, along with a Peabody Award, and transformed Sagan from an obscure astronomer into a pop-culture icon. ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, ...

'' magazine ran a cover story about Sagan soon after the show broadcast, referring to him as "creator, chief writer and host-narrator of the show". In 2000, "Cosmos" was released on a remastered set of DVDs.

"Billions and billions"

After ''Cosmos'' aired, Sagan became associated with thecatchphrase

A catchphrase (alternatively spelled catch phrase) is a phrase or expression recognized by its repeated utterance. Such phrases often originate in popular culture and in the arts, and typically spread through word of mouth and a variety of mass ...

"billions and billions," although he never actually used the phrase in the ''Cosmos'' series. Sagan & Druyan 1997, pp. 3–4. He rather used the term "billions ''upon'' billions."

Richard Feynman

Richard Phillips Feynman (; May 11, 1918 – February 15, 1988) was an American theoretical physicist, known for his work in the path integral formulation of quantum mechanics, the theory of quantum electrodynamics, the physics of the superfl ...

, a precursor to Sagan, was observed to have used the phrase "billions and billions" many times in his " red books". However, Sagan's frequent use of the word ''billions'' and distinctive delivery emphasizing the "b" (which he did intentionally, in place of more cumbersome alternatives such as "billions with a 'b, in order to distinguish the word from "millions") made him a favorite target of comic performers, including Johnny Carson, Gary Kroeger

Gary Kroeger (born April 13, 1957) is an American businessman, columnist, and actor best known for his work as a cast member on ''Saturday Night Live'' from 1982 to 1985, and his work on various game shows. He ran in the Democratic Congressional ...

, Mike Myers

Michael John Myers OC (born May 25, 1963) is a Canadian actor, comedian, screenwriter, and producer. His accolades include seven MTV Awards, a Primetime Emmy Award, and a Screen Actors Guild Award. In 2002, he was awarded a star on the Hollywoo ...

, Bronson Pinchot, Penn Jillette

Penn Fraser Jillette (born March 5, 1955) is an American magician, actor, musician, inventor, television presenter, and author, best known for his work with fellow magician Teller as half of the team Penn & Teller. The duo has been featured ...

, Harry Shearer

Harry Julius Shearer (born December 23, 1943) is an American actor, comedian, writer, musician, radio host, director and producer. Born in Los Angeles, California, Shearer began his career as a child actor. From 1969 to 1976, Shearer was a member ...

, and others. Frank Zappa satirized the line in the song "Be in My Video", noting as well "atomic light". Sagan took this all in good humor, and his final book was entitled ''Billions and Billions

''Billions and Billions: Thoughts on Life and Death at the Brink of the Millennium'' is a 1997 book by the American astronomer and science popularizer Carl Sagan. The last book written by Sagan before his death in 1996, it was published by Rando ...

'', which opened with a tongue-in-cheek discussion of this catchphrase, observing that Carson was an amateur astronomer and that Carson's comic caricature often included real science.

Sagan unit

As a humorous tribute to Sagan and his association with the catchphrase "billions and billions", a '' sagan'' has been defined as aunit of measurement

A unit of measurement is a definite magnitude of a quantity, defined and adopted by convention or by law, that is used as a standard for measurement of the same kind of quantity. Any other quantity of that kind can be expressed as a multi ...

equivalent to a very large number – technically at least four billion (two billion plus two billion) – of anything.

Sagan's number

Sagan's number is the number of stars in theobservable universe

The observable universe is a ball-shaped region of the universe comprising all matter that can be observed from Earth or its space-based telescopes and exploratory probes at the present time, because the electromagnetic radiation from these ob ...

. This number is reasonably well defined, because it is known what stars are and what the observable universe is, but its value is highly uncertain.

* In 1980, Sagan estimated it to be 10 sextillion

Two naming scales for large numbers have been used in English and other European languages since the early modern era: the long and short scales. Most English variants use the short scale today, but the long scale remains dominant in many non-Eng ...

in short scale

The long and short scales are two of several naming systems for integer powers of ten which use some of the same terms for different magnitudes.

For whole numbers smaller than 1,000,000,000 (109), such as one thousand or one million, the t ...

(1022).

* In 2003, it was estimated to be 70 sextillion (7 × 1022).

* In 2010, it was estimated to be 300 sextillion (3 × 1023).

Scientific and critical thinking advocacy

Sagan's ability to convey his ideas allowed many people to understand the cosmos better—simultaneously emphasizing the value and worthiness of the human race, and the relative insignificance of the Earth in comparison to the

Sagan's ability to convey his ideas allowed many people to understand the cosmos better—simultaneously emphasizing the value and worthiness of the human race, and the relative insignificance of the Earth in comparison to the Universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the universe. ...

. He delivered the 1977 series of Royal Institution Christmas Lectures

The Royal Institution Christmas Lectures are a series of lectures on a single topic each, which have been held at the Royal Institution in London each year since 1825, missing 1939–1942 because of the Second World War. The lectures present sc ...

in London.

Sagan was a proponent of the search for extraterrestrial life. He urged the scientific community to listen with radio telescopes for signals from potential intelligent extraterrestrial life-forms. Sagan was so persuasive that by 1982 he was able to get a petition advocating SETI published in the journal ''Science

Science is a systematic endeavor that Scientific method, builds and organizes knowledge in the form of Testability, testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earli ...

'', signed by 70 scientists, including seven Nobel Prize winners. This signaled a tremendous increase in the respectability of a then-controversial field. Sagan also helped Frank Drake

Frank Donald Drake (May 28, 1930 – September 2, 2022) was an American astrophysicist and astrobiologist.

He began his career as a radio astronomer, studying the planets of the Solar System and later pulsars. Drake expanded his interests ...

write the Arecibo message, a radio message beamed into space from the Arecibo radio telescope

The Arecibo Telescope was a spherical reflector radio telescope built into a natural sinkhole at the Arecibo Observatory located near Arecibo, Puerto Rico. A cable-mount steerable receiver and several radar transmitters for emitting signals we ...

on November 16, 1974, aimed at informing potential extraterrestrials about Earth.

Sagan was chief technology officer of the professional planetary research journal '' Icarus'' for 12 years. He co-founded The Planetary Society

The Planetary Society is an American internationally-active non-governmental nonprofit organization. It is involved in research, public outreach, and political space advocacy for engineering projects related to astronomy, planetary science, a ...

and was a member of the SETI Institute

The SETI Institute is a not-for-profit research organization incorporated in 1984 whose mission is to explore, understand, and explain the origin and nature of life in the universe, and to use this knowledge to inspire and guide present and futu ...

Board of Trustees. Sagan served as Chairman of the Division for Planetary Science of the American Astronomical Society, as President of the Planetology Section of the American Geophysical Union

The American Geophysical Union (AGU) is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization of Earth, atmospheric, ocean, hydrologic, space, and planetary scientists and enthusiasts that according to their website includes 130,000 people (not members). AGU's a ...

, and as Chairman of the Astronomy Section of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

At the height of the Cold War, Sagan became involved in

At the height of the Cold War, Sagan became involved in nuclear disarmament

Nuclear may refer to:

Physics

Relating to the nucleus of the atom:

*Nuclear engineering

*Nuclear physics

*Nuclear power

*Nuclear reactor

*Nuclear weapon

*Nuclear medicine

*Radiation therapy

*Nuclear warfare

Mathematics

* Nuclear space

* Nuclea ...

efforts by promoting hypotheses on the effects of nuclear war, when Paul Crutzen's "Twilight at Noon" concept suggested that a substantial nuclear exchange could trigger a nuclear twilight and upset the delicate balance of life on Earth by cooling the surface. In 1983 he was one of five authors—the "S"—in the follow-up "TTAPS" model (as the research article came to be known), which contained the first use of the term "nuclear winter

Nuclear winter is a severe and prolonged global climatic cooling effect that is hypothesized to occur after widespread firestorms following a large-scale nuclear war. The hypothesis is based on the fact that such fires can inject soot into t ...

", which his colleague Richard P. Turco had coined. In 1984 he co-authored the book '' The Cold and the Dark: The World after Nuclear War'' and in 1990 the book ''A Path Where No Man Thought: Nuclear Winter and the End of the Arms Race'', which explains the nuclear-winter hypothesis and advocates nuclear disarmament

Nuclear may refer to:

Physics

Relating to the nucleus of the atom:

*Nuclear engineering

*Nuclear physics

*Nuclear power

*Nuclear reactor

*Nuclear weapon

*Nuclear medicine

*Radiation therapy

*Nuclear warfare

Mathematics

* Nuclear space

* Nuclea ...

. Sagan received a great deal of skepticism and disdain for the use of media to disseminate a very uncertain hypothesis. A personal correspondence with nuclear physicist Edward Teller

Edward Teller ( hu, Teller Ede; January 15, 1908 – September 9, 2003) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist who is known colloquially as "the father of the hydrogen bomb" (see the Teller–Ulam design), although he did not care for ...

around 1983 began amicably, with Teller expressing support for continued research to ascertain the credibility of the winter hypothesis. However, Sagan and Teller's correspondence would ultimately result in Teller writing: "A propagandist is one who uses incomplete information to produce maximum persuasion. I can compliment you on being, indeed, an excellent propagandist, remembering that a propagandist is the better the less he appears to be one". Biographers of Sagan would also comment that from a scientific viewpoint, nuclear winter was a low point for Sagan, although, politically speaking, it popularized his image amongst the public.

The adult Sagan remained a fan of science fiction, although disliking stories that were not realistic (such as ignoring the inverse-square law) or, he said, did not include "thoughtful pursuit of alternative futures". He wrote books to popularize science, such as ''Cosmos'', which reflected and expanded upon some of the themes of ''A Personal Voyage'' and became the best-selling science book ever published in English; ''The Dragons of Eden

''The Dragons of Eden: Speculations on the Evolution of Human Intelligence'' is a 1977 book by Carl Sagan, in which the author combines the fields of anthropology, evolutionary biology, psychology, and computer science to give a perspective on ho ...

: Speculations on the Evolution of Human Intelligence'', which won a Pulitzer Prize; and '' Broca's Brain: Reflections on the Romance of Science''. Sagan also wrote the best-selling science fiction novel ''Contact'' in 1985, based on a film treatment

A film treatment (or simply treatment) is a piece of prose, typically the step between scene cards (index cards) and the first draft of a screenplay for a motion picture, television program, or radio play. It is generally longer and more detail ...

he wrote with his wife, Ann Druyan, in 1979, but he did not live to see the book's 1997 motion-picture adaptation, which starred Jodie Foster

Alicia Christian "Jodie" Foster (born November 19, 1962) is an American actress and filmmaker. She is the recipient of numerous accolades, including two Academy Awards, three British Academy Film Awards, three Golden Globe Awards, and the hono ...

and won the 1998 Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation.

Sagan wrote a sequel to ''Cosmos'', '' Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space'', which was selected as a notable book of 1995 by ''

Sagan wrote a sequel to ''Cosmos'', '' Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space'', which was selected as a notable book of 1995 by ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

''. He appeared on PBS's '' Charlie Rose'' program in January 1995. Sagan also wrote the introduction for Stephen Hawking's bestseller '' A Brief History of Time''. Sagan was also known for his popularization of science, his efforts to increase scientific understanding among the general public, and his positions in favor of scientific skepticism

Scientific skepticism or rational skepticism (also spelled scepticism), sometimes referred to as skeptical inquiry, is a position in which one questions the veracity of claims lacking empirical evidence. In practice, the term most commonly refe ...

and against pseudoscience

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or unfalsifiable clai ...

, such as his debunking of the Betty and Barney Hill abduction. To mark the tenth anniversary of Sagan's death, David Morrison

Lieutenant General David Lindsay Morrison (born 24 May 1956) is a retired senior officer of the Australian Army. He served as Chief of Army from June 2011 until his retirement in May 2015. He was named Australian of the Year for 2016.

Early ...

, a former student of Sagan, recalled "Sagan's immense contributions to planetary research, the public understanding of science, and the skeptical movement" in ''Skeptical Inquirer

''Skeptical Inquirer'' is a bimonthly American general-audience magazine published by the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry (CSI) with the subtitle: ''The Magazine for Science and Reason''.

Mission statement and goals

Daniel Loxton, writing in 2 ...

''.

Following Saddam Hussein

Saddam Hussein ( ; ar, صدام حسين, Ṣaddām Ḥusayn; 28 April 1937 – 30 December 2006) was an Iraqi politician who served as the fifth president of Iraq from 16 July 1979 until 9 April 2003. A leading member of the revolutio ...

's threats to light Kuwait

Kuwait (; ar, الكويت ', or ), officially the State of Kuwait ( ar, دولة الكويت '), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated in the northern edge of Eastern Arabia at the tip of the Persian Gulf, bordering Iraq to the nort ...

's oil wells on fire in response to any physical challenge to Iraqi control of the oil assets, Sagan together with his "TTAPS" colleagues and Paul Crutzen, warned in January 1991 in ''The Baltimore Sun

''The Baltimore Sun'' is the largest general-circulation daily newspaper based in the U.S. state of Maryland and provides coverage of local and regional news, events, issues, people, and industries.

Founded in 1837, it is currently owned by T ...

'' and ''Wilmington Morning Star

''Star-News'' is an American, English language daily newspaper for Wilmington, North Carolina, and its surrounding area (known as the Lower Cape Fear). It is North Carolina's oldest newspaper in continuous publication. It was owned by Halifax ...

'' newspapers that if the fires were left to burn over a period of several months, enough smoke from the 600 or so 1991 Kuwaiti oil fires

The Kuwaiti oil fires were caused by the Iraqi military setting fire to a reported 605 to 732 oil wells along with an unspecified number of oil filled low-lying areas, such as oil lakes and fire trenches, as part of a scorched earth policy while ...

"might get so high as to disrupt agriculture in much of South Asia ..." and that this possibility should "affect the war plans"; these claims were also the subject of a televised debate between Sagan and physicist Fred Singer

Siegfried Fred Singer (September 27, 1924 – April 6, 2020) was an Austrian-born American physicist and emeritus professor of environmental science at the University of Virginia, trained as an atmospheric physicist. He was known for rejecti ...

on January 22, aired on the ABC News

ABC News is the news division of the American broadcast network ABC. Its flagship program is the daily evening newscast ''ABC World News Tonight, ABC World News Tonight with David Muir''; other programs include Breakfast television, morning ...

program '' Nightline''.nuclear winter

Nuclear winter is a severe and prolonged global climatic cooling effect that is hypothesized to occur after widespread firestorms following a large-scale nuclear war. The hypothesis is based on the fact that such fires can inject soot into t ...

, with Singer arguing to the contrary. After the debate, the fires burnt for many months before extinguishing efforts were complete. The results of the smoke did not produce continental-sized cooling. Sagan later conceded in ''The Demon-Haunted World'' that the prediction did not turn out to be correct: "it ''was'' pitch black at noon and temperatures dropped 4–6 °C over the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a mediterranean sea in Western Asia. The bod ...

, but not much smoke reached stratospheric altitudes and Asia was spared".

In his later years Sagan advocated the creation of an organized search for asteroids/near-Earth object

A near-Earth object (NEO) is any small Solar System body whose orbit brings it into proximity with Earth. By convention, a Solar System body is a NEO if its closest approach to the Sun (perihelion) is less than 1.3 astronomical units (AU). ...

s (NEOs) that might impact the Earth but to forestall or postpone developing the technological methods that would be needed to defend against them. He argued that all of the numerous methods proposed to alter the orbit of an asteroid, including the employment of nuclear detonations, created a deflection dilemma: if the ability to deflect an asteroid away from the Earth exists, then one would also have the ability to divert a non-threatening object towards Earth, creating an immensely destructive weapon. In a 1994 paper he co-authored, he ridiculed a 3-day long " Near-Earth Object Interception Workshop" held by Los Alamos National Laboratory

Los Alamos National Laboratory (often shortened as Los Alamos and LANL) is one of the sixteen research and development laboratories of the United States Department of Energy (DOE), located a short distance northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico, ...

(LANL) in 1993 that did not, "even in passing" state that such interception and deflection technologies could have these "ancillary dangers".

Sagan remained hopeful that the natural NEO impact threat and the intrinsically double-edged essence of the methods to prevent these threats would serve as a "new and potent motivation to maturing international relations". Later acknowledging that, with sufficient international oversight, in the future a "work our way up" approach to implementing nuclear explosive deflection methods could be fielded, and when sufficient knowledge was gained, to use them to aid in mining asteroids. His interest in the use of nuclear detonations in space grew out of his work in 1958 for the Armour Research Foundation's Project A119

Project A119, also known as A Study of Lunar Research Flights, was a top-secret plan developed in 1958 by the United States Air Force. The aim of the project was to detonate a nuclear bomb on the Moon, which would help in answering some of th ...

, concerning the possibility of detonating a nuclear device on the lunar surface.

Sagan was a critic of Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...