SM U-21 (Germany) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

SM ''U-21'' was a

On 5 September 1914, ''U-21'' encountered the British

On 5 September 1914, ''U-21'' encountered the British  ''U-21'' caught the French steamer on 14 November; Hersing forced the ship to stop and examined her cargo manifest, ordered the crew to abandon ship, then sank ''Malachite'' with his

''U-21'' caught the French steamer on 14 November; Hersing forced the ship to stop and examined her cargo manifest, ordered the crew to abandon ship, then sank ''Malachite'' with his

''U-21'' arrived in her operational area off Gallipoli on 25 May; that day, she encountered the British

''U-21'' arrived in her operational area off Gallipoli on 25 May; that day, she encountered the British

U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare ro ...

built for the Imperial German Navy

The Imperial German Navy or the Imperial Navy () was the navy of the German Empire, which existed between 1871 and 1919. It grew out of the small Prussian Navy (from 1867 the North German Federal Navy), which was mainly for coast defence. Kaise ...

shortly before World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. The third of four Type U-19-class submarines, these were the first U-boats in German service to be equipped with diesel engines. ''U-21'' was built between 1911 and October 1913 at the ''Kaiserliche Werft'' (Imperial Shipyard) in Danzig. She was armed with four torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s and a single deck gun

A deck gun is a type of naval artillery mounted on the deck of a submarine. Most submarine deck guns were open, with or without a shield; however, a few larger submarines placed these guns in a turret.

The main deck gun was a dual-purpose ...

; a second gun was added during her career.

In September 1914, ''U-21'' became the first submarine to sink a ship with a self-propelled torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, and with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, s ...

when she destroyed the cruiser off the Firth of Forth. She also sank several transports in the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

and the Irish Sea

The Irish Sea or , gv, Y Keayn Yernagh, sco, Erse Sie, gd, Muir Èireann , Ulster-Scots: ''Airish Sea'', cy, Môr Iwerddon . is an extensive body of water that separates the islands of Ireland and Great Britain. It is linked to the Ce ...

later in the year, all in accordance with the cruiser rules

Cruiser rules is a colloquial phrase referring to the conventions regarding the attacking of a merchant ship by an armed vessel. Here ''cruiser'' is meant in its original meaning of a ship sent on an independent mission such as commerce raiding. ...

then in effect. In early 1915, ''U-21'' was transferred to the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

to support the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

against the Anglo-French attacks during the Gallipoli Campaign. Shortly after her arrival, she sank the British battleships

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1880s to describe a type o ...

and while they were bombarding Ottoman positions at Gallipoli. Further successes followed in the Mediterranean in 1916, including the sinking of the French armoured cruiser ''Amiral Charner'' in February.

Throughout 1916, ''U-21'' served in the Austro-Hungarian Navy as ''U-36'', since Germany was not yet at war with Italy and thus could not legally attack Italian warships under the German flag. She returned to Germany in March 1917 to join the unrestricted commerce war against British maritime trade. In 1918, she was withdrawn from front line service and was employed as a training submarine for new crews. She survived the war and sank while under tow by a British warship in 1919.

Design

''U-21'' waslong overall

__NOTOC__

Length overall (LOA, o/a, o.a. or oa) is the maximum length of a vessel's hull measured parallel to the waterline. This length is important while docking the ship. It is the most commonly used way of expressing the size of a ship, an ...

with a beam of and a height of . She displaced surfaced and submerged. The boat's propulsion system consisted of a pair of 8-cylinder 2-stroke diesel engine

The diesel engine, named after Rudolf Diesel, is an internal combustion engine in which ignition of the fuel is caused by the elevated temperature of the air in the cylinder due to mechanical compression; thus, the diesel engine is a so-ca ...

s manufactured by MAN

A man is an adult male human. Prior to adulthood, a male human is referred to as a boy (a male child or adolescent). Like most other male mammals, a man's genome usually inherits an X chromosome from the mother and a Y chromo ...

for use on the surface, and two electric double motor-dynamos built by AEG for use while submerged. ''U-21'' and her sister boats were the first German submarines to be equipped with diesel engines. The electric motors were powered by a bank of two 110-cell batteries. ''U-21'' could cruise at a top speed of on the surface and submerged. Steering was controlled by a pair of hydroplanes

Hydroplaning and hydroplane may refer to:

* Aquaplaning or hydroplaning, a loss of steering or braking due to water on the road

* Hydroplane (boat), a fast motor boat used in racing

** Hydroplane racing, a sport involving racing hydroplanes on lak ...

forward and another pair aft, and a single rudder

A rudder is a primary control surface used to steer a ship, boat, submarine, hovercraft, aircraft, or other vehicle that moves through a fluid medium (generally air or water). On an aircraft the rudder is used primarily to counter adve ...

.Gröner, p. 4

''U-21'' was armed with four torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s, which were supplied with a total of six torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, and with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, s ...

es. One pair was located in the bow and the other was in the stern. She was initially fitted with a machine gun for use on the surface; by the end of 1914 this was replaced with a SK L/30 gun. In 1916, a second 8.8 cm gun was added. ''U-21'' had a crew of four officers and twenty-five enlisted sailors.Gröner, p. 5

Service history

''U-21'' was built at the ''Kaiserliche Werft'' (Imperial Shipyard) in Danzig (now Gdańsk, Poland). She waslaid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

in 27 October 1911 and launched on 8 February 1913. After fitting-out

Fitting out, or outfitting, is the process in shipbuilding that follows the float-out/launching of a vessel and precedes sea trials. It is the period when all the remaining construction of the ship is completed and readied for delivery to her o ...

work was completed, she was commissioned into the fleet on 22 October 1913.

North Sea operations

At the outbreak ofWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in August 1914, ''U-21'' was based at Heligoland

Heligoland (; german: Helgoland, ; Heligolandic Frisian: , , Mooring Frisian: , da, Helgoland) is a small archipelago in the North Sea. A part of the German state of Schleswig-Holstein since 1890, the islands were historically possessions ...

in the German Bight

The German Bight (german: Deutsche Bucht; da, tyske bugt; nl, Duitse bocht; fry, Dútske bocht; ; sometimes also the German Bay) is the southeastern bight of the North Sea bounded by the Netherlands and Germany to the south, and Denmark and ...

, commanded by ''Kapitänleutnant

''Kapitänleutnant'', short: KptLt/in lists: KL, ( en, captain lieutenant) is an officer grade of the captains' military hierarchy group () of the German Bundeswehr. The rank is rated OF-2 in NATO, and equivalent to Hauptmann in the Heer an ...

'' (Captain Lieutenant) Otto Hersing. In early August, Hersing took ''U-21'' on a patrol into the Dover Straits but he found no British vessels. On 14 August ''U-21'' went on a second patrol, this time with her sister boats and , to the northern North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea, epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the ...

between Norway and Scotland. The patrol was an attempt to locate the British blockade line and gather intelligence, but they spotted only a single cruiser and a destroyer off the Norwegian coast. Hersing attempted to enter the Firth of Forth—a major Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

fleet base—later in the month but was unsuccessful.

On 5 September 1914, ''U-21'' encountered the British

On 5 September 1914, ''U-21'' encountered the British scout cruiser

A scout cruiser was a type of warship of the early 20th century, which were smaller, faster, more lightly armed and armoured than protected cruisers or light cruisers, but larger than contemporary destroyers. Intended for fleet scouting duties a ...

off the Isle of May

The Isle of May is located in the north of the outer Firth of Forth, approximately off the coast of mainland Scotland. It is about long and wide. The island is owned and managed by NatureScot as a national nature reserve. There are now no ...

. Hersing had surfaced his U-boat to recharge his batteries when a lookout spotted smoke from ''Pathfinder''s funnels on the horizon. ''U-21'' submerged to make an attack, but ''Pathfinder'' turned away on her patrol line; ''U-21'' could not hope to keep up with the cruiser while submerged, so Hersing broke off the chase and resumed recharging his batteries. Shortly thereafter, ''Pathfinder'' reversed course again and headed back toward ''U-21''. Hersing manoeuvred into an attack position and fired a single torpedo, which hit ''Pathfinder'' just aft of her conning tower. The torpedo detonated one of the cruiser's magazines

A magazine is a periodical publication, generally published on a regular schedule (often weekly or monthly), containing a variety of content. They are generally financed by advertising, purchase price, prepaid subscriptions, or by a combination ...

, which destroyed the ship in a large explosion. The British were able to lower only a single lifeboat

Lifeboat may refer to:

Rescue vessels

* Lifeboat (shipboard), a small craft aboard a ship to allow for emergency escape

* Lifeboat (rescue), a boat designed for sea rescues

* Airborne lifeboat, an air-dropped boat used to save downed airmen

...

before ''Pathfinder'' sank. Other survivors were found clinging to wreckage by torpedo boats that rushed to the scene. ''Pathfinder'' was the first warship to be sunk by a modern submarine. A total of 261 sailors were killed in the attack.

''U-21'' caught the French steamer on 14 November; Hersing forced the ship to stop and examined her cargo manifest, ordered the crew to abandon ship, then sank ''Malachite'' with his

''U-21'' caught the French steamer on 14 November; Hersing forced the ship to stop and examined her cargo manifest, ordered the crew to abandon ship, then sank ''Malachite'' with his deck gun

A deck gun is a type of naval artillery mounted on the deck of a submarine. Most submarine deck guns were open, with or without a shield; however, a few larger submarines placed these guns in a turret.

The main deck gun was a dual-purpose ...

. ''U-21''s next success came three days later with the British collier , which he also sank in accordance with the cruiser rules

Cruiser rules is a colloquial phrase referring to the conventions regarding the attacking of a merchant ship by an armed vessel. Here ''cruiser'' is meant in its original meaning of a ship sent on an independent mission such as commerce raiding. ...

that governed commerce raiding

Commerce raiding (french: guerre de course, "war of the chase"; german: Handelskrieg, "trade war") is a form of naval warfare used to destroy or disrupt logistics of the enemy on the open sea by attacking its merchant shipping, rather than en ...

. These two ships were the first vessels to be sunk in the restricted German submarine offensive against British and French merchant shipping.

On 22 January, Hersing took his U-boat through the Dover Barrage

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maidston ...

in the Channel before turning into the Irish Sea

The Irish Sea or , gv, Y Keayn Yernagh, sco, Erse Sie, gd, Muir Èireann , Ulster-Scots: ''Airish Sea'', cy, Môr Iwerddon . is an extensive body of water that separates the islands of Ireland and Great Britain. It is linked to the Ce ...

. He shelled the airfield on Walney Island

Walney Island, also known as the Isle of Walney, is an island off the west coast of England, at the western end of Morecambe Bay in the Irish Sea. It is part of Barrow-in-Furness, separated from the mainland by Walney Channel, which is spanned b ...

, though a coastal battery quickly forced him to withdraw. The next week, ''U-21'' stopped the collier ; after evacuating her crew, the Germans sank her with scuttling charges. Later that day, 30 January 1915, ''U-21'' stopped and sank the steamers and . In both cases, Hersing adhered to the prize rules, including flagging down a passing trawler to pick up the ships' crews. After these successes, ''U-21'' withdrew from the area to avoid the British patrols that would arrive in the aftermath of the sinkings. After passing back through the Dover Barrage, ''U-21'' cruised back to Wilhelmshaven

Wilhelmshaven (, ''Wilhelm's Harbour''; Northern Low Saxon: ''Willemshaven'') is a coastal town in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is situated on the western side of the Jade Bight, a bay of the North Sea, and has a population of 76,089. Wilhelmsh ...

.

In the Mediterranean 1915–1917

In April 1915, ''U-21'' was transferred to theMediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

to support Germany's ally, Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula in ...

. She left Kiel on 25 April, and the first leg of the voyage, from Germany to Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, took eighteen days. Hersing took his submarine north around Scotland to avoid the Dover patrols, and rendezvoused with the supply ship off Cape Finisterre to refuel. Unfortunately for the Germans, ''Marzala'' carried poor quality oil that could not be burned in the boat's diesel engines; ''U-21'' had less than half of her fuel supply remaining, and was only halfway on the voyage to Austria-Hungary. Hersing was forced to run his U-boat on the surface to conserve fuel, which increased the risk of detection by Allied forces. While en route the Germans managed to avoid patrolling British and French torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of ...

s and transport ships that might have reported their location.Gray, pp. 121–122

''U-21'' finally arrived in Cattaro

Kotor (Montenegrin Cyrillic: Котор, ), historically known as Cattaro (from Italian: ), is a coastal town in Montenegro. It is located in a secluded part of the Bay of Kotor. The city has a population of 13,510 and is the administrative ...

on 13 May, with only of fuel left in her tanks—she had left Germany with . She spent a week at the Austro-Hungarian submarine bases at Pola Pola or POLA may refer to:

People

* House of Pola, an Italian noble family

* Pola Alonso (1923–2004), Argentine actress

* Pola Brändle (born 1980), German artist and photographer

* Pola Gauguin (1883–1961), Danish painter

* Pola Gojawiczyńsk ...

and Cattaro in mid-May, where she was visited by Georg von Trapp

Georg Ludwig Ritter von Trapp (4 April 1880 – 30 May 1947) was an officer in the Austro-Hungarian Navy who later became the patriarch of the Trapp Family, Trapp Family Singers. Trapp was the most successful Austro-Hungarian submarine command ...

, an Austro-Hungarian U-boat commander.O'Connell, pp. 144, 190 Several other German submarines joined ''U-21'' in the following months, after calls for assistance from the Ottoman ground forces on the Gallipoli peninsula, who were taking heavy casualties from the bombardments from Allied warships. These U-boats included , , , and .

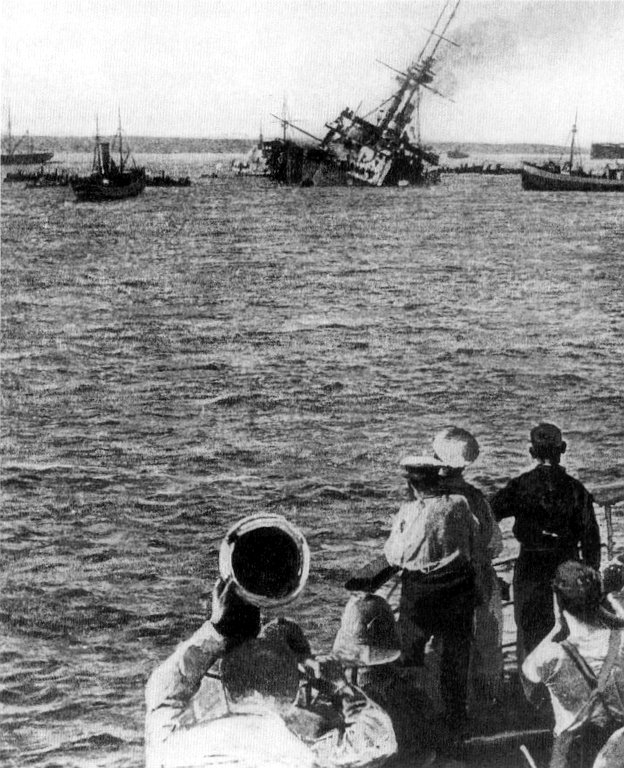

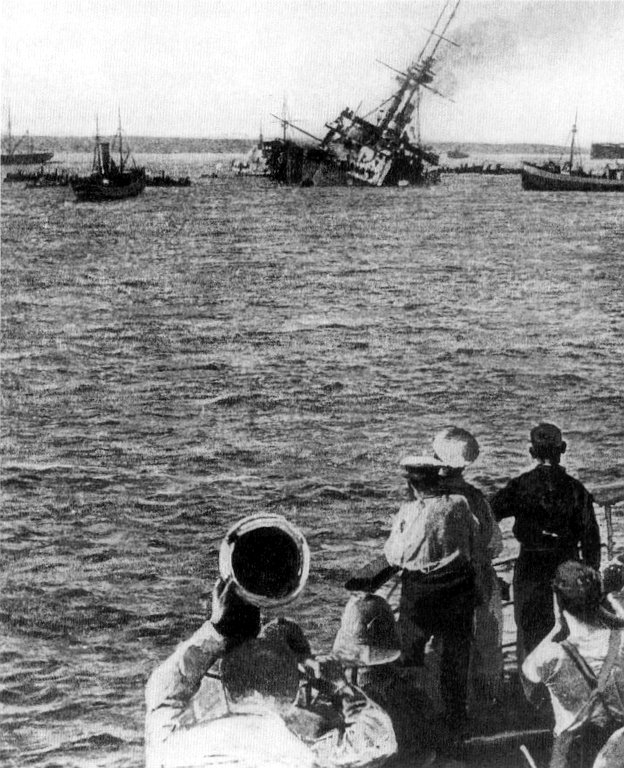

''U-21'' arrived in her operational area off Gallipoli on 25 May; that day, she encountered the British

''U-21'' arrived in her operational area off Gallipoli on 25 May; that day, she encountered the British pre-dreadnought battleship

Pre-dreadnought battleships were sea-going battleships built between the mid- to late- 1880s and 1905, before the launch of in 1906. The pre-dreadnought ships replaced the ironclad battleships of the 1870s and 1880s. Built from steel, protec ...

. Hersing brought his U-boat to within of his target and fired a single torpedo, which hit ''Triumph''. ''U-21'' then dived under the sinking battleship to escape the destroyers hunting her. Hersing took his boat to the sea floor to wait for the Allied forces to abandon the chase. After twenty-eight hours on the bottom, ''U-21'' surfaced to recharge her batteries and bring in fresh air. On 27 May, Hersing attacked and sank his second battleship, . This time, the British had attempted to protect her with torpedo net

Torpedo nets were a passive ship defensive device against torpedoes. They were in common use from the 1890s until the Second World War. They were superseded by the anti-torpedo bulge and torpedo belts.

Origins

With the introduction of the White ...

s and several small ships, but Hersing was able to aim a torpedo through the defences. ''Majestic'' sank in four minutes. These two successes brought significant dividends: all Allied capital ships were withdrawn to protected anchorages and were thus unable to bombard Ottoman positions on the peninsula. For these two successes, the crew of ''U-21'' was awarded the Iron Cross

The Iron Cross (german: link=no, Eisernes Kreuz, , abbreviated EK) was a military decoration in the Kingdom of Prussia, and later in the German Empire (1871–1918) and Nazi Germany (1933–1945). King Frederick William III of Prussia es ...

by Kaiser Wilhelm II

, house = Hohenzollern

, father = Frederick III, German Emperor

, mother = Victoria, Princess Royal

, religion = Lutheranism (Prussian United)

, signature = Wilhelm II, German Emperor Signature-.svg

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor ...

, while Hersing himself received the Pour le Mérite

The ' (; , ) is an order of merit (german: Verdienstorden) established in 1740 by King Frederick II of Prussia. The was awarded as both a military and civil honour and ranked, along with the Order of the Black Eagle, the Order of the Red Eag ...

, Germany's highest award for valour.

After sinking ''Majestic'', Hersing took his submarine to refuel at a Turkish port before attempting the dangerous route through the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

to Constantinople. While transiting the straits, ''U-21'' was nearly pulled into a whirlpool but the Germans managed to escape. After arriving in the Ottoman capital, the crew were given a large welcoming ceremony attended by Enver Pasha. ''U-21'' required significant maintenance, and so the crew was given a month of shore leave while the repairs were carried out. Once the repair work was finished, ''U-21'' sortied through the Dardanelles for another patrol. Hersing spotted the Allied munitions ship ''Carthage'', which he sank with a single torpedo. Later on the patrol, a lookout on an Allied trawler spotted ''U-21''s periscope; the Germans had to crash-dive to escape being rammed, but doing so brought them into a minefield. One mine exploded off the U-boat's stern but it caused no significant damage, and ''U-21'' was able to withdraw to Constantinople.

''U-21'' thereafter moved to the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

where she and served as the nucleus of the newly formed Black Sea Flotilla. In September, ''U-21'' undertook another patrol in the eastern Mediterranean. In the meantime, the Allies had established a complete blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are leg ...

of the Dardanelles with mines and nets to prevent submarines from operating out of Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya ( Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

. Unable to return to Constantinople, Hersing instead took his U-boat back to Cattaro. Germany would not be in a formal state of war with Italy until August 1916. As a result, German U-boats could not legally attack Italian ships, despite the fact that Italy was at war with Austria-Hungary. To circumvent this restriction, German submarines operating in the Mediterranean were commissioned into the Austro-Hungarian Navy, though their German crews remained aboard. Following her arrival in Cattaro, ''U-21'' was commissioned as the Austro-Hungarian ''U-36''. She served under this name until Italy declared war on Germany on 27 August 1916.

In the meantime, ''U-36'' began to have further successes against Allied maritime trade. On 1 February 1916, she sank the British steamer . A week later, ''U-36'' torpedoed and sank the French armoured cruiser ''Amiral Charner'' off the Syrian coast. The cruiser sank quickly with heavy loss of life; 427 men went down with their ship. In early 1916, while patrolling off Sicily, ''U-36'' encountered an Allied Q-ship

Q-ships, also known as Q-boats, decoy vessels, special service ships, or mystery ships, were heavily armed merchant ships with concealed weaponry, designed to lure submarines into making surface attacks. This gave Q-ships the chance to open f ...

, an auxiliary cruiser

An armed merchantman is a merchant ship equipped with guns, usually for defensive purposes, either by design or after the fact. In the days of sail, piracy and privateers, many merchantmen would be routinely armed, especially those engaging in ...

disguised as an unarmed merchant ship. ''U-36'' fired a shot across the Q-ship's bow, but it refused to stop and returned fire with a small deck gun. Hersing decided to close and sink the ship, which then revealed her heavy armament. Wounded by shell splinters, Hersing withdrew his submarine under cover of a smoke screen before submerging.

On 30 April, Hersing sank the British steamer . He sank three small Italian sailing vessels off Corsica between 26 and 28 October, and on 31 October ''U-21'' sent the 5,838 grt steamship to the bottom. Over the next three days, another four Italian ships—the steamships and and two small sailing vessels—were sunk off Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

. On 23 December, ''U-21'' torpedoed the British steamer east of Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

, but the ship managed to reach Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

.

Return to the North Sea

In early 1917, ''U-21'' was recalled to Germany to join theunrestricted submarine warfare

Unrestricted submarine warfare is a type of naval warfare in which submarines sink merchant ships such as freighters and tankers without warning, as opposed to attacks per prize rules (also known as "cruiser rules") that call for warships to s ...

campaign being waged against Britain. While en route, she stopped and sank a pair of British sailing vessels off Oporto

Porto or Oporto () is the second-largest city in Portugal, the capital of the Porto District, and one of the Iberian Peninsula's major urban areas. Porto city proper, which is the entire municipality of Porto, is small compared to its metropo ...

on 16 February and another pair of Portuguese sailing ships the next day. On 20 February, ''U-21'' sank the French steamer in the Bay of Biscay. Two days later in the Western Approaches

The Western Approaches is an approximately rectangular area of the Atlantic Ocean lying immediately to the west of Ireland and parts of Great Britain. Its north and south boundaries are defined by the corresponding extremities of Britain. The c ...

, she finished off the Dutch steamer , which had been damaged by the submarine on 15 February. Seven more ships followed ''Bandoeng'' that day. They included six more Dutch steamers—, , , , , and —and the Norwegian steamer . On another patrol in late April, Hersing caught four more ships: the Norwegian and on 22 April and on 29 April, along with the Russian on 30 April. Another Russian vessel, , followed on 3 May. The British steamers and were sunk on 6 and 8 May, respectively. The Swedish ''Baltic'', which proved to be Hersing's last victory, was sunk on 27 June.

Hersing attacked a convoy of fifteen merchant ships escorted by fourteen destroyers in August south-west of Ireland. He took ''U-21'' between two of the escorting destroyers and briefly used his periscope to gauge the speed and course of the transports before firing two torpedoes and diving. Hersing reported both torpedoes hit and the destroyers immediately rushed to begin their depth charge attacks. After a five-hour hunt, the destroyers withdrew to rejoin the convoy. The experience led Hersing to change tactics in future attacks on escorted convoys; instead of attacking the ships from as far away as possible, he chose to fire his torpedoes at closer range and then dive under the transport ships, where the destroyers would be unable to launch their depth charges for fear of damaging the transports. As of 1918, she was assigned to the III U-boat Flotilla. Later in 1918, the submarine was used as a training boat for new crews. She survived the war, but on 22 February 1919, she accidentally sank in the North Sea while under tow to Britain, where she was to be formally surrendered.Gröner, p. 6

In the course of her commerce raiding, ''U-21'' sank forty ships for a combined , and damaged two more for a total of . The ships sunk included two battleships and two cruisers.

Summary of raiding history

Footnotes

Notes

Citations

References

* * * * * * * * *External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:U0021 Type U 19 submarines World War I submarines of Germany 1913 ships Ships built in Danzig U-boats commissioned in 1913 U-boats sunk in 1919 Maritime incidents in 1919 U-boat accidents World War I shipwrecks in the North Sea