SMS Zähringen on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

SMS (

was ordered under the contract name "E", as a new unit for the fleet. Her

was ordered under the contract name "E", as a new unit for the fleet. Her

took part in a pair of training cruises with I Squadron during 9–19 January and 27 February – 16 March 1905. Individual and squadron training followed, with an emphasis on gunnery drills. On 12 July, the fleet began a major training exercise in the North Sea. The fleet then cruised through the

took part in a pair of training cruises with I Squadron during 9–19 January and 27 February – 16 March 1905. Individual and squadron training followed, with an emphasis on gunnery drills. On 12 July, the fleet began a major training exercise in the North Sea. The fleet then cruised through the

At the start of World War I, was mobilized as part of IV Battle Squadron, along with her four sister ships and the battleships and . The squadron was divided into VII and VIII Divisions, with assigned to the former. On 26 August, the ships were sent to rescue the stranded

At the start of World War I, was mobilized as part of IV Battle Squadron, along with her four sister ships and the battleships and . The squadron was divided into VII and VIII Divisions, with assigned to the former. On 26 August, the ships were sent to rescue the stranded

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

: Seiner Majestät Schiff

His (or Her) Majesty's Ship, abbreviated HMS and H.M.S., is the ship prefix used for ships of the navy in some monarchies. Derived terms such as HMAS and equivalents in other languages such as SMS are used.

United Kingdom

With regard to the se ...

; English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

: His Majesty's Ship ) was the third pre-dreadnought

Pre-dreadnought battleships were sea-going battleships built between the mid- to late- 1880s and 1905, before the launch of in 1906. The pre-dreadnought ships replaced the ironclad battleships of the 1870s and 1880s. Built from steel, protec ...

battleship of the German Imperial Navy (). Laid down in 1899 at the Germaniawerft shipyard in Kiel

Kiel () is the capital and most populous city in the northern German state of Schleswig-Holstein, with a population of 246,243 (2021).

Kiel lies approximately north of Hamburg. Due to its geographic location in the southeast of the Jutland ...

, she was launched on 12 June 1901 and commissioned on 25 October 1902. Her sisters were , , and ; they were the first capital ships built under the Navy Law of 1898, brought about by Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz

Alfred Peter Friedrich von Tirpitz (19 March 1849 – 6 March 1930) was a German grand admiral, Secretary of State of the German Imperial Naval Office, the powerful administrative branch of the German Imperial Navy from 1897 until 1916. Prussi ...

. The ship, named for the former royal House of Zähringen, was armed with a main battery

A main battery is the primary weapon or group of weapons around which a warship is designed. As such, a main battery was historically a gun or group of guns, as in the broadsides of cannon on a ship of the line. Later, this came to be turreted ...

of four guns and had a top speed of .

saw active duty in I Squadron of the German fleet for the majority of her career. During this period, she was occupied with extensive annual training and making good-will visits to foreign countries. The training exercises conducted during this period provided the framework for the High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet (''Hochseeflotte'') was the battle fleet of the German Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. The formation was created in February 1907, when the Home Fleet (''Heimatflotte'') was renamed as the High Seas ...

's operations during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. She was decommissioned in September 1910, but returned to service briefly for training in 1912, where she accidentally rammed and sank a torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of ...

. After the start of World War I in August 1914, was brought back to active duty in IV Battle Squadron

IV may refer to:

Businesses and organizations

*Immigration Voice, an activist organization

*Industrievereinigung, Federation of Austrian Industry

*Intellectual Ventures, a privately held intellectual property company

*InterVarsity Christian Fello ...

. The ship saw limited duty in the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and ...

, including during the Battle of the Gulf of Riga

The Battle of the Gulf of Riga was a World War I naval operation of the German High Seas Fleet against the Russian Baltic Fleet in the Gulf of Riga in the Baltic Sea in August 1915. The operation's objective was to destroy the Russian naval for ...

in August 1915, but saw no combat with Russian forces. By late 1915, crew shortages and the threat of British submarines forced the to withdraw older battleships like .

Instead, was relegated to a target ship

A target ship is a vessel — typically an obsolete or captured warship — used as a seaborne target for naval gunnery practice or for weapons testing. Targets may be used with the intention of testing effectiveness of specific types of ammunit ...

for torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, and with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, s ...

training in 1917. In the mid-1920s, she was heavily reconstructed and equipped for use as a radio-controlled target ship. She served in this capacity until 1944, when she was sunk in Gotenhafen

Gdynia ( ; ; german: Gdingen (currently), (1939–1945); csb, Gdiniô, , , ) is a city in northern Poland and a seaport on the Baltic Sea coast. With a population of 243,918, it is the 12th-largest city in Poland and the second-largest in th ...

by British bomber

A bomber is a military combat aircraft designed to attack ground and naval targets by dropping air-to-ground weaponry (such as bombs), launching torpedoes, or deploying air-launched cruise missiles. The first use of bombs dropped from an air ...

s during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

. The retreating Germans raised the ship and moved her to the harbor mouth, where they scuttled

Scuttling is the deliberate sinking of a ship. Scuttling may be performed to dispose of an abandoned, old, or captured vessel; to prevent the vessel from becoming a navigation hazard; as an act of self-destruction to prevent the ship from being ...

her to block the port. was broken up ''in situ'' in 1949–50.

Description

After the German (Imperial Navy) ordered the four s in 1889, a combination of budgetary constraints, opposition in the (Imperial Diet), and a lack of a coherent fleet plan delayed the acquisition of further battleships. The Secretary of the (Imperial Navy Office), (''VAdm''—Vice Admiral) Friedrich von Hollmann struggled throughout the early and mid-1890s to secure parliamentary approval for the first three s. In June 1897, Hollmann was replaced by (''KAdm''—Rear Admiral)Alfred von Tirpitz

Alfred Peter Friedrich von Tirpitz (19 March 1849 – 6 March 1930) was a German grand admiral, Secretary of State of the German Imperial Naval Office, the powerful administrative branch of the German Imperial Navy from 1897 until 1916. Prussi ...

, who quickly proposed and secured approval for the first Naval Law in early 1898. The law authorized the last two ships of the class, as well as the five ships of the , the first class of battleship built under Tirpitz's tenure. The s were broadly similar to the s, carrying the same armament but with a more comprehensive armor layout.

was long overall

__NOTOC__

Length overall (LOA, o/a, o.a. or oa) is the maximum length of a vessel's hull measured parallel to the waterline. This length is important while docking the ship. It is the most commonly used way of expressing the size of a ship, an ...

and had a beam of and a draft

Draft, The Draft, or Draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a vesse ...

of forward. She displaced as designed and up to at full load

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into wei ...

. The ship was powered by three 3-cylinder vertical triple expansion engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be tr ...

s that drove three screws. Steam was provided by six naval and six cylindrical boilers, all of which burned coal. s powerplant was rated at , which generated a top speed of . The ship had a cruising radius of at a speed of . She had a crew of 30 officers and 650 enlisted men.

s armament consisted of a main battery

A main battery is the primary weapon or group of weapons around which a warship is designed. As such, a main battery was historically a gun or group of guns, as in the broadsides of cannon on a ship of the line. Later, this came to be turreted ...

of four 24 cm (9.4 in) SK L/40 guns in twin-gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechani ...

s, one fore and one aft of the central superstructure. Her secondary armament

Secondary armament is a term used to refer to smaller, faster-firing weapons that were typically effective at a shorter range than the main (heavy) weapons on military systems, including battleship- and cruiser-type warships, tanks/armored ...

consisted of eighteen 15 cm (5.9 inch) SK L/40 guns and twelve 8.8 cm (3.45 in) SK L/30 quick-firing guns. The armament suite was rounded out with six torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s, all submerged in the hull; one was in the bow, one in the stern, and the other four were on the broadside. was protected with Krupp armor. Her armored belt was thick in the central citadel

A citadel is the core fortified area of a town or city. It may be a castle, fortress, or fortified center. The term is a diminutive of "city", meaning "little city", because it is a smaller part of the city of which it is the defensive core.

I ...

that protected her magazines

A magazine is a periodical publication, generally published on a regular schedule (often weekly or monthly), containing a variety of content. They are generally financed by advertising, purchase price, prepaid subscriptions, or by a combination ...

and machinery spaces, and the deck was thick. The main battery turrets had of armor plating.

Service history

Construction to 1904

was ordered under the contract name "E", as a new unit for the fleet. Her

was ordered under the contract name "E", as a new unit for the fleet. Her keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element on a vessel. On some sailboats, it may have a hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose, as well. As the laying down of the keel is the initial step in the construction of a ship, in Br ...

was laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

on 21 November 1899, at Friedrich Krupp

Friedrich Carl Krupp (Essen, 17 July 1787 – Essen, 8 October 1826) was a German steel manufacturer and founder of the Krupp family commercial empire that is now subsumed into ThyssenKrupp AG.

Biography

After the death of his father, he was bro ...

's Germaniawerft dockyard in Kiel

Kiel () is the capital and most populous city in the northern German state of Schleswig-Holstein, with a population of 246,243 (2021).

Kiel lies approximately north of Hamburg. Due to its geographic location in the southeast of the Jutland ...

. was launched on 12 June 1901, with her launching speech given by Frederick I, Grand Duke of Baden

Frederick I (german: Friedrich Wilhelm Ludwig; 9 September 1826 – 28 September 1907) was the Grand Duke of Baden from 1858 to 1907.

Life

Frederick was born in Karlsruhe, Baden, on 9 September 1826. He was the third son of Leopold, Gr ...

and head of the House of Zähringen; his wife, Grand Duchess Louise, christened the ship. was commissioned on 25 October 1902, and began her sea trials, which lasted until 10 February 1903. She thereafter replaced the battleship in I Squadron of the Active Fleet. On 2 April 1903, the squadron went to sea and began gunnery training two days later. These exercises continued for the rest of the month, interrupted only by heavy storms.

A major training cruise followed the next month; on 10 May the ships departed the Elbe river

The Elbe (; cs, Labe ; nds, Ilv or ''Elv''; Upper Sorbian, Upper and dsb, Łobjo) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of ...

and made their way into the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

. They cruised south to Spain, passing Ushant

Ushant (; br, Eusa, ; french: Ouessant, ) is a French island at the southwestern end of the English Channel which marks the westernmost point of metropolitan France. It belongs to Brittany and, in medieval terms, Léon. In lower tiers of govern ...

on 14 May and reaching the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, def ...

five days later. There, they conducted a reconnaissance exercise off Pontevedra

Pontevedra (, ) is a Spanish city in the north-west of the Iberian Peninsula. It is the capital of both the '' Comarca'' (County) and Province of Pontevedra, and of the Rías Baixas in Galicia. It is also the capital of its own municipality wh ...

before anchoring in Vigo

Vigo ( , , , ) is a city and municipality in the province of Pontevedra, within the autonomous community of Galicia, Spain. Located in the northwest of the Iberian Peninsula, it sits on the southern shore of an inlet of the Atlantic Ocean, the ...

on 20 May. The squadron departed Spain on 30 May. The ships passed through the Strait of Dover on 3 June and continued into the Kattegat

The Kattegat (; sv, Kattegatt ) is a sea area bounded by the Jutlandic peninsula in the west, the Danish Straits islands of Denmark and the Baltic Sea to the south and the provinces of Bohuslän, Västergötland, Halland and Skåne in Sweden ...

. There, they rendezvoused with the torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of ...

s of I (Torpedo Boat Flotilla)—commanded by (Lieutenant Commander) Franz von Hipper

Franz Ritter von Hipper (13 September 1863 – 25 May 1932) was an admiral in the German Imperial Navy (''Kaiserliche Marine''). Franz von Hipper joined the German Navy in 1881 as an officer cadet. He commanded several torpedo boat units an ...

—for a mock attack on the fortifications at Kiel. Later in June, the ships took part in additional gunnery training and were present at the Kiel Week

The Kiel Week (german: Kieler Woche) or Kiel Regatta is an annual sailing event in Kiel, the capital of Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. It is the largest sailing event in Europe, and also one of the largest Volksfeste in Germany, attracting ...

sailing regatta. During Kiel Week, an American squadron that included the battleship and four cruisers visited. Following the end of Kiel Week, I Squadron, which had been strengthened with the new cruiser , and I went to sea for more tactical and gunnery exercises in the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea, epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the ...

, which lasted from 6 to 28 July. The annual fleet maneuvers began on 15 August; they consisted of a blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are leg ...

exercise in the North Sea, a cruise of the entire fleet first to Norwegian waters and then to Kiel in early September, and finally a mock attack on Kiel. The exercises concluded on 12 September. The year's training schedule concluded with a cruise into the eastern Baltic that started on 23 November and a cruise into the Skagerrak

The Skagerrak (, , ) is a strait running between the Jutland peninsula of Denmark, the southeast coast of Norway and the west coast of Sweden, connecting the North Sea and the Kattegat sea area through the Danish Straits to the Baltic Sea.

T ...

that began on 1 December.

and the rest of I Squadron participated in an exercise in the Skagerrak from 11 to 21 January 1904. Further squadron exercises followed from 8 to 17 March, and a major fleet exercise took place in the North Sea in May. In July, I Squadron and I Scouting Group

The I Scouting Group (german: I. Aufklärungsgruppe) was a special reconnaissance unit within the German Kaiserliche Marine. The unit was famously commanded by Admiral Franz von Hipper during World War I. The I Scouting Group was one of the most ...

visited Britain, including a stop at Plymouth on 10 July. The German fleet departed on 13 July, bound for the Netherlands; I Squadron anchored in Vlissingen

Vlissingen (; zea, label= Zeelandic, Vlissienge), historically known in English as Flushing, is a municipality and a city in the southwestern Netherlands on the former island of Walcheren. With its strategic location between the Scheldt river ...

the following day. There, the ships were visited by Queen Wilhelmina. I Squadron remained in Vlissingen until 20 July, when they departed for a cruise in the northern North Sea with the rest of the fleet. The squadron stopped in Molde, Norway, on 29 July, while the other units went to other ports. The fleet reassembled on 6 August and steamed back to Kiel, where it conducted a mock attack on the harbor on 12 August. During its cruise in the North Sea, the fleet experimented with wireless telegraphy

Wireless telegraphy or radiotelegraphy is transmission of text messages by radio waves, analogous to electrical telegraphy using cables. Before about 1910, the term ''wireless telegraphy'' was also used for other experimental technologies for ...

on a large scale and searchlights at night for communication and recognition signals. Immediately after returning to Kiel, the fleet began preparations for the autumn maneuvers, which began on 29 August in the Baltic. The fleet moved to the North Sea on 3 September, where it took part in a major landing operation

A landing operation is a military

action during which a landing force, usually utilizing landing craft, is transferred to land with the purpose of power projection ashore. With the proliferation of aircraft, a landing may refer to amphibious force ...

, after which the ships took the ground troops from IX Corps 9 Corps, 9th Corps, Ninth Corps, or IX Corps may refer to:

France

* 9th Army Corps (France)

* IX Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

Germany

* IX Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial Germ ...

that participated in the exercises to Altona for a parade for Wilhelm II. The ships then conducted their own parade for the Kaiser off the island of Helgoland

Heligoland (; german: Helgoland, ; Heligolandic Frisian: , , Mooring Frisian: , da, Helgoland) is a small archipelago in the North Sea. A part of the German state of Schleswig-Holstein since 1890, the islands were historically possessions ...

on 6 September. Three days later, the fleet returned to the Baltic via the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal

The Kiel Canal (german: Nord-Ostsee-Kanal, literally "North- oEast alticSea canal", formerly known as the ) is a long freshwater canal in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein. The canal was finished in 1895, but later widened, and links the ...

, where it participated in further landing operations with IX Corps and the Guards Corps. On 15 September, the maneuvers came to an end.

1905–1914

took part in a pair of training cruises with I Squadron during 9–19 January and 27 February – 16 March 1905. Individual and squadron training followed, with an emphasis on gunnery drills. On 12 July, the fleet began a major training exercise in the North Sea. The fleet then cruised through the

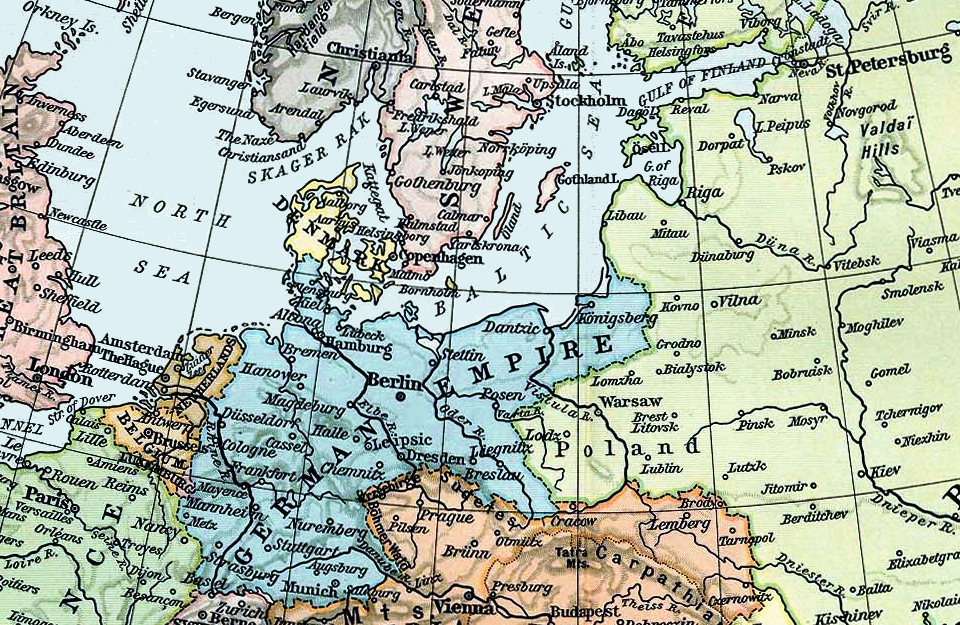

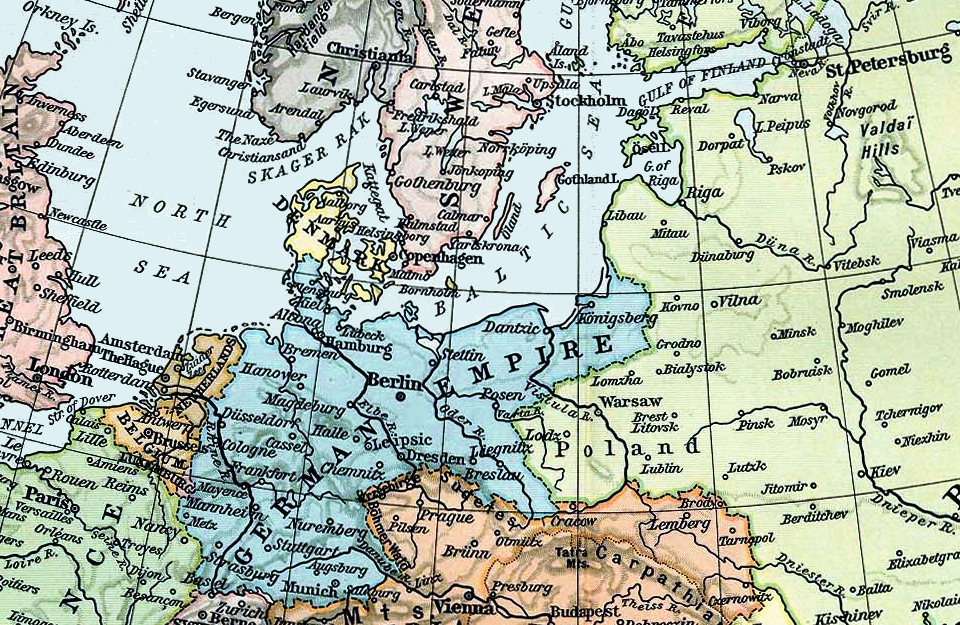

took part in a pair of training cruises with I Squadron during 9–19 January and 27 February – 16 March 1905. Individual and squadron training followed, with an emphasis on gunnery drills. On 12 July, the fleet began a major training exercise in the North Sea. The fleet then cruised through the Kattegat

The Kattegat (; sv, Kattegatt ) is a sea area bounded by the Jutlandic peninsula in the west, the Danish Straits islands of Denmark and the Baltic Sea to the south and the provinces of Bohuslän, Västergötland, Halland and Skåne in Sweden ...

and stopped in Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( or .; da, København ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a proper population of around 815.000 in the last quarter of 2022; and some 1.370,000 in the urban area; and the wider Copenhagen metropolitan ar ...

and Stockholm. The summer cruise ended on 9 August, though the autumn maneuvers that would normally have begun shortly thereafter were delayed by a visit from the British Channel Fleet that month. The British fleet stopped in Danzig, Swinemünde, and Flensburg, where it was greeted by units of the German Navy; and the main German fleet was anchored at Swinemünde for the occasion. The visit was strained by the Anglo-German naval arms race

The arms race between Great Britain and Germany that occurred from the last decade of the nineteenth century until the advent of World War I in 1914 was one of the intertwined causes of that conflict. While based in a bilateral relationship tha ...

. As a result of the British visit, the 1905 autumn maneuvers were shortened considerably, from 6 to 13 September, and consisted only of exercises in the North Sea. The first exercise presumed a naval blockade in the German Bight, and the second envisioned a hostile fleet attempting to force the defenses of the Elbe. In October, I Squadron went on a cruise in the Baltic. In early December, I and II Squadrons went on their regular winter cruise, this time to Danzig, where they arrived on 12 December. While on the return trip to Kiel, the fleet conducted tactical exercises.

The fleet undertook a heavier training schedule in 1906 than in previous years. The ships were occupied with individual, division and squadron exercises throughout April. Starting on 13 May, major fleet exercises took place in the North Sea and lasted until 8 June with a cruise around the Skagen

Skagen () is Denmark's northernmost town, on the east coast of the Skagen Odde peninsula in the far north of Jutland, part of Frederikshavn Municipality in Nordjylland, north of Frederikshavn and northeast of Aalborg. The Port of Skage ...

into the Baltic. The fleet began its usual summer cruise to Norway in mid-July. The fleet was present for the birthday of Norwegian King Haakon VII

Haakon VII (; born Prince Carl of Denmark; 3 August 187221 September 1957) was the King of Norway from November 1905 until his death in September 1957.

Originally a Danish prince, he was born in Copenhagen as the son of the future Frederick ...

on 3 August. The German ships departed the following day for Helgoland, to join exercises being conducted there. The fleet was back in Kiel by 15 August, where preparations for the autumn maneuvers began. On 22–24 August, the fleet took part in landing exercises in Eckernförde Bay

Eckernförde Bay (german: Eckernförder Bucht; da, Egernførde Fjord or Egernfjord) is a firth and a branch of the Bay of Kiel between the Danish Wahld peninsula in the south and the Schwansen peninsula in the north in the Baltic Sea off the land ...

outside Kiel. The maneuvers were paused from 31 August to 3 September when the fleet hosted vessels from Denmark and Sweden, along with a Russian squadron from 3 to 9 September in Kiel. The maneuvers resumed on 8 September and lasted five more days. The ship participated in the uneventful winter cruise into the Kattegat and Skagerrak from 8 to 16 December.

The first quarter of 1907 followed the previous pattern and, on 16 February, the Active Battle Fleet was re-designated the High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet (''Hochseeflotte'') was the battle fleet of the German Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. The formation was created in February 1907, when the Home Fleet (''Heimatflotte'') was renamed as the High Seas ...

. From the end of May to early June the fleet went on its summer cruise in the North Sea, returning to the Baltic via the Kattegat. This was followed by the regular cruise to Norway from 12 July to 10 August. During the autumn maneuvers, which lasted from 26 August to 6 September, the fleet conducted landing exercises in northern Schleswig

The Duchy of Schleswig ( da, Hertugdømmet Slesvig; german: Herzogtum Schleswig; nds, Hartogdom Sleswig; frr, Härtochduum Slaswik) was a duchy in Southern Jutland () covering the area between about 60 km (35 miles) north and 70 km ...

with IX Corps. The winter training cruise went into the Kattegat from 22 to 30 November. In May 1908, the fleet went on a major cruise into the Atlantic instead of its normal voyage in the North Sea, which included a stop in Horta in the Azores

)

, motto =( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem= ( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

. The fleet returned to Kiel on 13 August to prepare for the autumn maneuvers, which lasted from 27 August to 7 September. Division exercises in the Baltic immediately followed from 7 to 13 September. In February 1909, was employed as an icebreaker

An icebreaker is a special-purpose ship or boat designed to move and navigate through ice-covered waters, and provide safe waterways for other boats and ships. Although the term usually refers to ice-breaking ships, it may also refer to smaller ...

for the ports of the western Baltic.

On 21 September 1910, was decommissioned and her crew was transferred to the new dreadnought battleship

The dreadnought (alternatively spelled dreadnaught) was the predominant type of battleship in the early 20th century. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's , had such an impact when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her ...

, which had recently been completed. was then assigned to the Reserve Division of the North Sea, though the unit was dissolved on 12 May 1912, and its ships transferred to the Reserve Division of the Baltic Sea. was recommissioned briefly, from 9 to 12 May, to transfer her to Kiel. She returned to service again later that year, from 14 August to 28 September, to take part in that year's fleet maneuvers as part of III Squadron. While exercising on 4 September, accidentally rammed and sank the torpedo boat . Seven men from ''G171'' were killed in the accident. was again decommissioned after the conclusion of the exercises, and did not return to service until the start of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in August 1914.

World War I

At the start of World War I, was mobilized as part of IV Battle Squadron, along with her four sister ships and the battleships and . The squadron was divided into VII and VIII Divisions, with assigned to the former. On 26 August, the ships were sent to rescue the stranded

At the start of World War I, was mobilized as part of IV Battle Squadron, along with her four sister ships and the battleships and . The squadron was divided into VII and VIII Divisions, with assigned to the former. On 26 August, the ships were sent to rescue the stranded light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to th ...

, which had run aground off the island of Odensholm in the eastern Baltic, but by 28 August, the ship's crew had been forced to detonate explosives to destroy before the relief force had arrived. As a result, and the rest of the squadron cruised back toward Bornholm that day.

Starting on 3 September, IV Squadron, assisted by the armored cruiser

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a battleship and fast eno ...

, conducted a sweep into the Baltic. The operation lasted until 9 September and failed to bring Russian naval units to battle. Two days later the ships were transferred to the North Sea, though they stayed there only briefly, returning to the Baltic on 20 September. From 22 to 26 September, the squadron took part in a sweep into the eastern Baltic in an unsuccessful attempt to find and destroy Russian warships. From 4 December 1914 to 2 April 1915, the ships of IV Squadron were tasked with coastal defense duties along Germany's North Sea coast against incursions from the British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

.

The German Army requested naval assistance for its campaign against Russia; Prince Heinrich, the commander of all naval forces in the Baltic, made VII Division, IV Scouting Group, and the torpedo boats of the Baltic fleet available for the operation. On 6 May, the IV Squadron ships were tasked with providing support to the assault on Libau. and the other ships were stationed off Gotland to intercept any Russian cruisers that might attempt to intervene in the landings; the Russians did not do so. After cruisers from IV Scouting Group encountered Russian cruisers off Gotland, the ships of VII Division deployed—with a third dummy funnel

A funnel is a tube or pipe that is wide at the top and narrow at the bottom, used for guiding liquid or powder into a small opening.

Funnels are usually made of stainless steel, aluminium, glass, or plastic. The material used in its construct ...

erected to disguise them as the more powerful s—along with the cruiser . The ships advanced as far as the island of Utö on 9 May and to Kopparstenarna the following day, but by then the Russian cruisers had withdrawn. Later that day, the British submarines and spotted IV Squadron, but were too far away to attack them.

From 27 May to 4 July, was back in the North Sea, patrolling the mouths of the Jade, Ems, and Elbe

The Elbe (; cs, Labe ; nds, Ilv or ''Elv''; Upper and dsb, Łobjo) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Re ...

rivers. During this period, the naval high command realized that the old -class ships would be useless in action against the Royal Navy, but could be effectively used against the much weaker Russian forces in the Baltic. As a result, the ships were transferred back to the Baltic in July, and they departed Kiel on the 7th, bound for Danzig. On 10 July, the ships proceeded further east to Neufahrwassar, along with VIII Torpedo-boat Flotilla. The IV Squadron ships sortied on 12 July to make a demonstration, returning to Danzig on 21 July without encountering Russian forces.

The following month, the naval high command began an operation against the Gulf of Riga

The Gulf of Riga, Bay of Riga, or Gulf of Livonia ( lv, Rīgas līcis, et, Liivi laht) is a bay of the Baltic Sea between Latvia and Estonia.

The island of Saaremaa (Estonia) partially separates it from the rest of the Baltic Sea. The main c ...

in support of the Gorlice–Tarnów Offensive

The Gorlice–Tarnów offensive during World War I was initially conceived as a minor German offensive to relieve Russian pressure on the Austro-Hungarians to their south on the Eastern Front, but resulted in the Central Powers' chief offensi ...

. The Baltic naval forces were reinforced with significant elements of the High Seas Fleet, including I Battle Squadron

The I Battle Squadron was a unit of the German Imperial Navy before and during World War I. Being part of the High Seas Fleet, the squadron saw action throughout the war, including the Battle of Jutland on 31 May – 1 June 1916, where it for ...

, I Scouting Group, II Scouting Group

II is the Roman numeral for 2.

II may also refer to:

Biology and medicine

* Image intensifier, medical imaging equipment

* Invariant chain, a polypeptide involved in the formation and transport of MHC class II protein

*Optic nerve, the second ...

, and II Torpedo-boat Flotilla. Prince Heinrich planned that Schmidt's ships would force their way into the Gulf and destroy the Russian warships in Riga, while the heavy units of the High Seas Fleet would patrol to the north to prevent any of the main Russian Baltic Fleet that might try to interfere with the operation.

The Germans launched their attack on 8 August, initiating the Battle of the Gulf of Riga

The Battle of the Gulf of Riga was a World War I naval operation of the German High Seas Fleet against the Russian Baltic Fleet in the Gulf of Riga in the Baltic Sea in August 1915. The operation's objective was to destroy the Russian naval for ...

. Minesweeper

A minesweeper is a small warship designed to remove or detonate naval mines. Using various mechanisms intended to counter the threat posed by naval mines, minesweepers keep waterways clear for safe shipping.

History

The earliest known usage of ...

s attempted to clear a path through the Irbe Strait

Irbe Strait, also known as Irben Strait ( et, Kura kurk, lv, Irbes jūras šaurums, liv, Sūr mer), forms the main exit out of the Gulf of Riga to the Baltic Sea, between the Sõrve Peninsula forming the southern end of the island Saaremaa in ...

, covered by and , while and the rest of the squadron remained outside the strait. The Russian battleship attacked the Germans in the strait, forcing them to withdraw. During the action, the cruiser and the torpedo boat were damaged by mines and the torpedo boats and were mined and sunk. Schmidt withdrew his ships to re-coal and Prince Heinrich debated making another attempt, as by that time it had become clear that the German Army's advance toward Riga had stalled. Nevertheless, Prince Heinrich decided to try to force the channel a second time, but now two dreadnought battleships from I Squadron would cover the minesweepers. was instead left behind in Libau.

On 9 September, and her four sisters sortied in an attempt to locate Russian warships off Gotland, but returned to port two days later without having engaged any opponents. Additionally, the threat from submarines in the Baltic convinced the German navy to withdraw the elderly -class ships from active service. and most of the other IV Squadron ships left Libau on 10 November, bound for Kiel; upon arrival the following day, they were designated the Reserve Division of the Baltic. The ships were anchored in Schilksee in Kiel. On 31 January 1916, the division was dissolved, and the ships were dispersed for subsidiary duties.

was initially used as a training ship in Kiel. In 1917, the ship was used to train stokers but then became a target ship for torpedo boats and the old ironclad , which had by that time become a torpedo training ship. Later, the considered replacing the cruiser , then the gunnery training ship, with , and work began to refit her for this duty on 22 July 1918. The repairs and modifications had not been completed by the end of the war. The ship was left in Germany, and on 13 December was placed out of service.

and

According to Article 181 of theTreaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

, and her sisters were to be demilitarized. This would permit the newly reorganized to retain the vessels for auxiliary purposes. was therefore stricken from the navy list on 11 March 1920 and disarmed. She was then used as a hulk in Wilhelmshaven until 1926. That year, the decided to rebuild into a radio-controlled target ship

A target ship is a vessel — typically an obsolete or captured warship — used as a seaborne target for naval gunnery practice or for weapons testing. Targets may be used with the intention of testing effectiveness of specific types of ammunit ...

, similar to vessels operated by the Royal Navy and the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

. The conversion work lasted through 1928.

The ship had its engine system overhauled; the three-shaft arrangement was replaced by a pair of 3-cylinder, vertical triple expansion engines. These were supplied with steam by two naval oil-fired, water-tube boilers. The system was designed to be operated remotely via wireless telegraph, with the receiver located deep inside the ship behind heavy armor protection so it would not be damaged by fire. The new propulsion system provided a top speed of . The superstructure was also cut down, removing all extraneous structures, and the hull was extensively modified. The watertight subdivisions were significantly increased, openings in the hull were sealed, and the ship was filled with some of cork. When the conversion was completed, displaced . While not in use as a target, the ship was operated by a crew of 67. The torpedo boat was converted for use as s control vessel, and was renamed . She was later replaced by , which was also renamed .

participated in her first gunfire training session on 8 August 1928, in a ceremony held for President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Paul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (; abbreviated ; 2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German field marshal and statesman who led the Imperial German Army during World War I and later became President of Germany fr ...

. During the exercise, the old battleship fired at . Over the course of the next sixteen years, she served as a target vessel for the and then the of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, together with the old battleship . This period revealed that the addition of cork, meant to help keep the ship afloat in the event of a major hull breach, was a poor choice, as it caught fire easily. The modification of the ship's propulsion system also proved to be a mistake, as the ship's speed was too low, and it hindered her maneuverability. These experiences affected the conversion of , and neither mistake was repeated when that vessel was converted in the mid-1930s.

continued on in service through World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, initially based in Wilhelmshaven. , , and their radio control boats were assigned to the Inspectorate of Naval Artillery on 1 August 1942. On 18 December 1944, the old ship was hit by bombs during an air raid on Gotenhafen

Gdynia ( ; ; german: Gdingen (currently), (1939–1945); csb, Gdiniô, , , ) is a city in northern Poland and a seaport on the Baltic Sea coast. With a population of 243,918, it is the 12th-largest city in Poland and the second-largest in th ...

and sank in shallow water. She was temporarily refloated and towed to the harbor entrance, where she was scuttled to block the port on 26 March 1945. The wreck was broken up in situ starting in 1949; work lasted until 1950.

Footnotes

Notes

Citations

References

* * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Zahringen Wittelsbach-class battleships World War I battleships of Germany World War II auxiliary ships of Germany World War II shipwrecks in the Baltic Sea 1901 ships Auxiliary ships of the Reichsmarine Auxiliary ships of the Kriegsmarine Ships built in Kiel Ships sunk by British aircraft Maritime incidents in December 1944 Maritime incidents in March 1945