SMS Yorck on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

SMS ("

The two -class cruisers were ordered in 1902 as part of the fleet expansion program specified by the Second Naval Law of 1900. The two ships were incremental developments of the preceding s, the most significant difference being a longer hull; the extra space was used to add a pair of boilers, which increased horsepower by and speed by . The launch of the British battlecruiser in 1907 quickly rendered all of the armored cruisers that had been built by the world's navies obsolescent.

was

The two -class cruisers were ordered in 1902 as part of the fleet expansion program specified by the Second Naval Law of 1900. The two ships were incremental developments of the preceding s, the most significant difference being a longer hull; the extra space was used to add a pair of boilers, which increased horsepower by and speed by . The launch of the British battlecruiser in 1907 quickly rendered all of the armored cruisers that had been built by the world's navies obsolescent.

was

His Majesty's Ship

His (or Her) Majesty's Ship, abbreviated HMS and H.M.S., is the ship prefix used for ships of the navy in some monarchies. Derived terms such as HMAS and equivalents in other languages such as SMS are used.

United Kingdom

With regard to the se ...

Yorck") was the second and final ship of the of armored cruiser

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a battleship and fast eno ...

s built for the German (Imperial Navy) as part of a major naval expansion program aimed at strengthening the fleet. was named for Ludwig Yorck von Wartenburg

Johann David Ludwig Graf Yorck von Wartenburg (born von Yorck; 26 September 1759 – 4 October 1830) was a Prussian ''Generalfeldmarschall'' instrumental in the switching of the Kingdom of Prussia from a French alliance to a Russian allianc ...

, a Prussian field marshal. She was laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

in 1903 at the Blohm & Voss shipyard in Hamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

, launched in May 1904, and commissioned in November 1905. The ship was armed with a main battery of four guns and had a top speed of . Like many of the late armored cruisers, was quickly rendered obsolescent by the advent of the battlecruiser; as a result, her peacetime career was limited.

spent the first seven years of her career in I Scouting Group

The I Scouting Group (german: I. Aufklärungsgruppe) was a special reconnaissance unit within the German Kaiserliche Marine. The unit was famously commanded by Admiral Franz von Hipper during World War I. The I Scouting Group was one of the most ...

, the reconnaissance force for the High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet (''Hochseeflotte'') was the battle fleet of the German Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. The formation was created in February 1907, when the Home Fleet (''Heimatflotte'') was renamed as the High Seas ...

, initially as the group flagship. She undertook training exercises and made several cruises in the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

. was involved in several accidents, including an accidental explosion aboard the ship in 1911 and a collision with a torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of ...

in 1913. In May 1913, she was decommissioned and placed in reserve until the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in July 1914. She was then mobilized

Mobilization is the act of assembling and readying military troops and supplies for war. The word ''mobilization'' was first used in a military context in the 1850s to describe the preparation of the Prussian Army. Mobilization theories and ...

and assigned to III Scouting Group. On 3 November, she formed part of the screen for the High Seas Fleet as it sailed to support a German raid on Yarmouth

The Raid on Yarmouth, on 3 November 1914, was an attack by the Imperial German Navy on the British North Sea port and town of Great Yarmouth. German shells only landed on the beach causing little damage to the town, after German ships laying m ...

; on the return of the fleet to Wilhelmshaven

Wilhelmshaven (, ''Wilhelm's Harbour''; Northern Low Saxon: ''Willemshaven'') is a coastal town in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is situated on the western side of the Jade Bight, a bay of the North Sea, and has a population of 76,089. Wilhelmsh ...

, the ships encountered heavy fog and anchored in the Schillig Roads

Schillig is a village in the Friesland district of Lower Saxony in Germany. It is situated on the west coast of Jade Bay and is north of the town of Wilhelmshaven

Wilhelmshaven (, ''Wilhelm's Harbour''; Northern Low Saxon: ''Willemshaven'') ...

to await better visibility. Believing the fog to have cleared sufficiently, the ship's commander ordered to get underway in the early hours of 4 November. She entered a German minefield in the haze, struck two mines, and sank with heavy loss of life. The wreck was dismantled progressively between the 1920s and 1980s to reduce the navigational hazard it posed.

Design

The two -class cruisers were ordered in 1902 as part of the fleet expansion program specified by the Second Naval Law of 1900. The two ships were incremental developments of the preceding s, the most significant difference being a longer hull; the extra space was used to add a pair of boilers, which increased horsepower by and speed by . The launch of the British battlecruiser in 1907 quickly rendered all of the armored cruisers that had been built by the world's navies obsolescent.

was

The two -class cruisers were ordered in 1902 as part of the fleet expansion program specified by the Second Naval Law of 1900. The two ships were incremental developments of the preceding s, the most significant difference being a longer hull; the extra space was used to add a pair of boilers, which increased horsepower by and speed by . The launch of the British battlecruiser in 1907 quickly rendered all of the armored cruisers that had been built by the world's navies obsolescent.

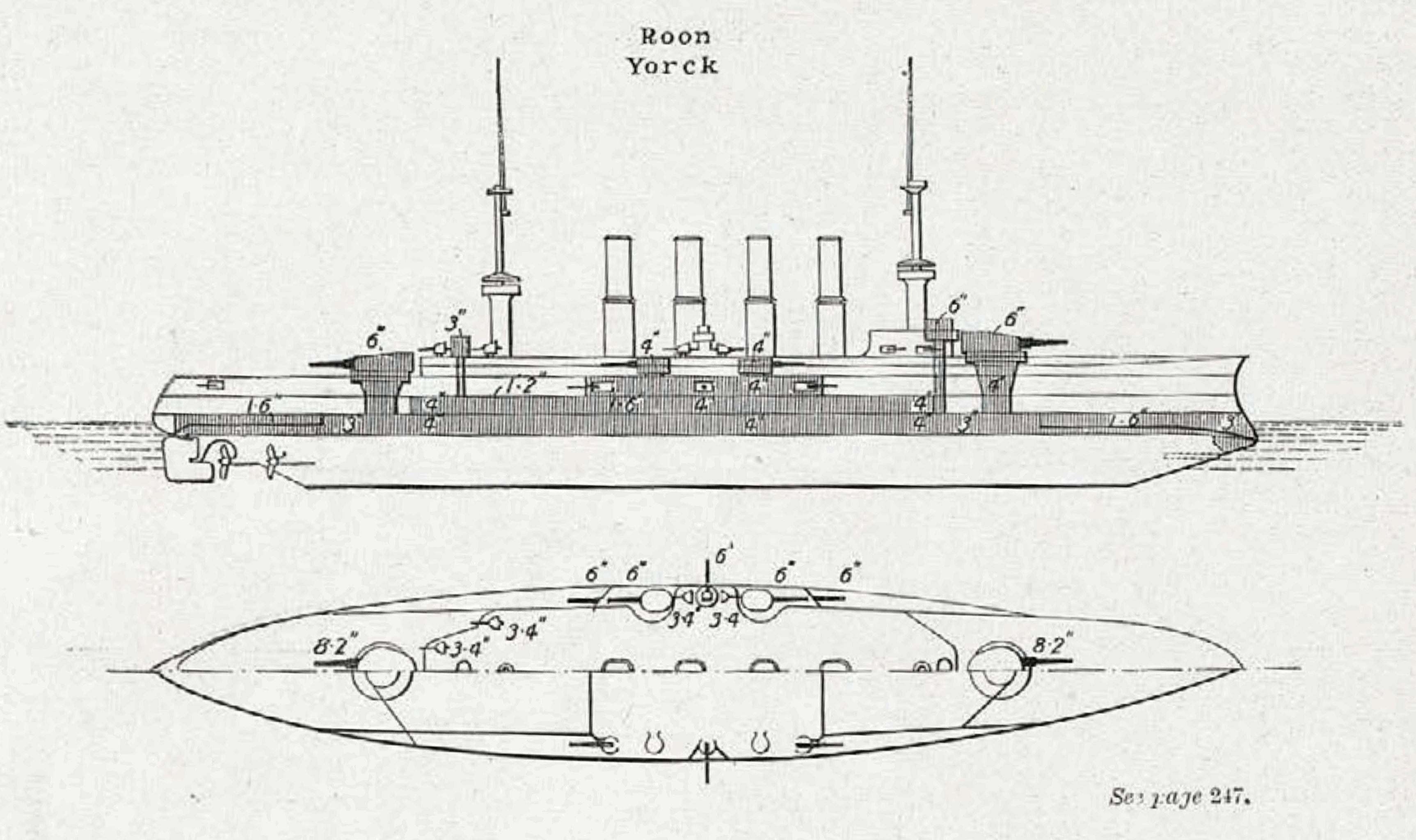

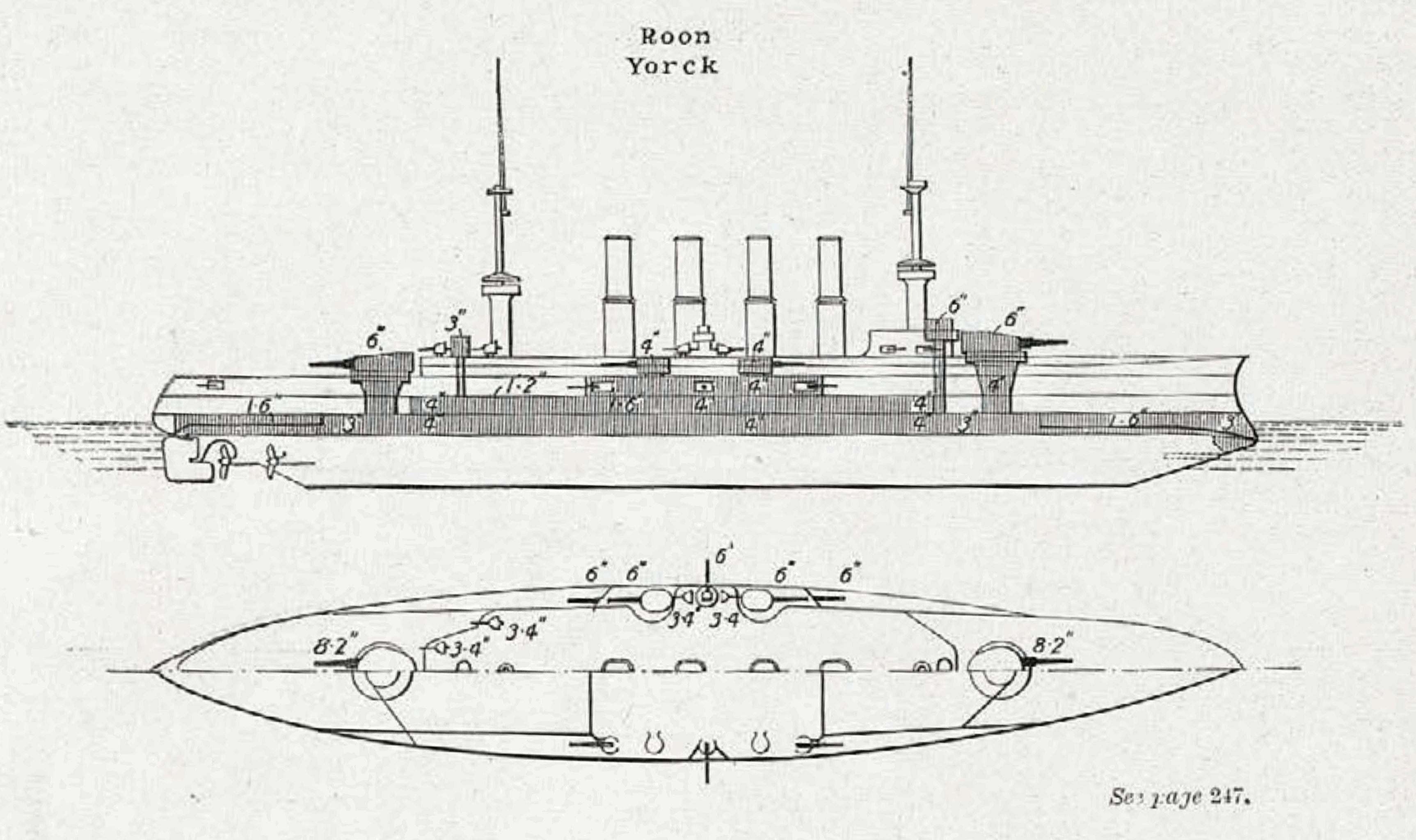

was long overall

__NOTOC__

Length overall (LOA, o/a, o.a. or oa) is the maximum length of a vessel's hull measured parallel to the waterline. This length is important while docking the ship. It is the most commonly used way of expressing the size of a ship, an ...

and had a beam of and a draft

Draft, The Draft, or Draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a vesse ...

of forward. She displaced as built and fully loaded. The ship had a crew of 35 officers and 598 enlisted men, though this was frequently augmented with an admiral's staff during periods when she served as a flagship.

The ship was propelled by three vertical triple-expansion steam engine

A compound steam engine unit is a type of steam engine where steam is expanded in two or more stages.

A typical arrangement for a compound engine is that the steam is first expanded in a high-pressure ''(HP)'' cylinder, then having given up ...

s, steam being provided by sixteen coal-fired water-tube boiler

A high pressure watertube boiler (also spelled water-tube and water tube) is a type of boiler in which water circulates in tubes heated externally by the fire. Fuel is burned inside the furnace, creating hot gas which boils water in the steam-gen ...

s. s propulsion system developed a total of and yielded a maximum speed of on trials, falling short of her intended speed of . She carried up to of coal, which enabled a maximum range of up to at a cruising speed of .

was armed with four SK L/40 guns arranged in two twin-gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechani ...

s, one on either end of the superstructure. Her secondary armament

Secondary armament is a term used to refer to smaller, faster-firing weapons that were typically effective at a shorter range than the main (heavy) weapons on military systems, including battleship- and cruiser-type warships, tanks/armored ...

consisted of ten SK L/40 guns; four were in single-gun turrets on the upper deck and the remaining six were in casemates in a main-deck battery. For close-range defense against torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of ...

s, she carried fourteen SK L/35 guns, all in individual mounts in the superstructure and in the hull. She also had four underwater torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s, one in the bow, one in the stern, and one on each broadside. She carried a total of eleven torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, and with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, s ...

es.

The ship was protected with Krupp cemented armor

Krupp armour was a type of steel naval armour used in the construction of capital ships starting shortly before the end of the nineteenth century. It was developed by Germany's Krupp Arms Works in 1893 and quickly replaced Harvey armour as the ...

, the belt armor

Belt armor is a layer of heavy metal armor plated onto or within the outer hulls of warships, typically on battleships, battlecruisers and cruisers, and aircraft carriers.

The belt armor is designed to prevent projectiles from penetrating to ...

being thick amidships

This glossary of nautical terms is an alphabetical listing of terms and expressions connected with ships, shipping, seamanship and navigation on water (mostly though not necessarily on the sea). Some remain current, while many date from the 17th ...

and reduced to on either end. The main battery turrets had thick faces. Her deck was thick, connected to the lower edge of the belt by thick sloped armor.

Service history

Construction – 1908

was ordered under the provisional name and built at the Blohm & Voss shipyard inHamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

under construction number 167. Her keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element on a vessel. On some sailboats, it may have a hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose, as well. As the laying down of the keel is the initial step in the construction of a ship, in Br ...

was laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

on 25 April 1903 and she was launched on 14 May 1904. General Wilhelm von Hahnke

Wilhelm Gustav Karl Bernhard von Hahnke (1 October 1833 in Berlin – 8 February 1912) was a Prussian Field Marshal, and Chief of the German Imperial Military Cabinet from 1888 to 1901.

Biography

Born into an old Prussian family of offic ...

gave a speech at the launching ceremony and the vessel was christened after Ludwig Yorck von Wartenburg

Johann David Ludwig Graf Yorck von Wartenburg (born von Yorck; 26 September 1759 – 4 October 1830) was a Prussian ''Generalfeldmarschall'' instrumental in the switching of the Kingdom of Prussia from a French alliance to a Russian allianc ...

, a Prussian general during the Napoleonic Wars by Josephine Yorck von Wartenburg, one of his descendants. Fitting-out

Fitting out, or outfitting, is the process in shipbuilding that follows the float-out/launching of a vessel and precedes sea trials. It is the period when all the remaining construction of the ship is completed and readied for delivery to her o ...

work was completed by late 1905, when the ship began builder's trials, after which a shipyard crew transferred the vessel to Kiel

Kiel () is the capital and most populous city in the northern German state of Schleswig-Holstein, with a population of 246,243 (2021).

Kiel lies approximately north of Hamburg. Due to its geographic location in the southeast of the Jutland ...

, where she was commissioned into the fleet on 21 November. After her commissioning, served with the fleet in I Scouting Group

The I Scouting Group (german: I. Aufklärungsgruppe) was a special reconnaissance unit within the German Kaiserliche Marine. The unit was famously commanded by Admiral Franz von Hipper during World War I. The I Scouting Group was one of the most ...

, which she formally joined on 27 March 1906. On 2 April, she replaced the armored cruiser as the group flagship, under the command of (''VAdm''—Vice Admiral) Gustav Schmidt. Over the next several years, took part in the peacetime routine of training exercises with the fleet reconnaissance forces and with the entire High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet (''Hochseeflotte'') was the battle fleet of the German Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. The formation was created in February 1907, when the Home Fleet (''Heimatflotte'') was renamed as the High Seas ...

, including major fleet exercises every autumn in late August and early September.

On 29 September, (''KAdm''—Rear Admiral) Hugo von Pohl

Hugo von Pohl (25 August 1855 – 23 February 1916) was a German admiral who served during the First World War. He joined the Navy in 1872 and served in various capacities, including with the new torpedo boats in the 1880s, and in the ''Reic ...

replaced Schmidt as the group commander. After 1907's autumn maneuvers, went into drydock for an extensive overhaul from 11 September to 28 October, during which time temporarily replaced her as the flagship. While she was out of service, Pohl was replaced by ''KAdm'' August von Heeringen, who raised his flag aboard upon her return from the shipyard. The ship went on a major cruise into the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

from 7 to 28 February 1908 with the other ships of the scouting group. During the cruise, the ships conducted various tactical exercises and experimented with using their wireless telegraphy

Wireless telegraphy or radiotelegraphy is transmission of text messages by radio waves, analogous to electrical telegraphy using cables. Before about 1910, the term ''wireless telegraphy'' was also used for other experimental technologies for ...

equipment at long distances. They stopped in Vigo

Vigo ( , , , ) is a city and municipality in the province of Pontevedra, within the autonomous community of Galicia, Spain. Located in the northwest of the Iberian Peninsula, it sits on the southern shore of an inlet of the Atlantic Ocean, the ...

, Spain, to replenish their coal for the voyage home. On 1 May, the new armored cruiser joined I Scouting Group, replacing as the group flagship.

Another Atlantic cruise followed in July and August; this time, the cruise was made in company with the battleship squadrons of the High Seas Fleet. Prince Heinrich had pressed for such a cruise the previous year, arguing that it would prepare the fleet for overseas operations and would break up the monotony of training in German waters, though tensions with Britain over the developing Anglo-German naval arms race

The arms race between Great Britain and Germany that occurred from the last decade of the nineteenth century until the advent of World War I in 1914 was one of the intertwined causes of that conflict. While based in a bilateral relationship tha ...

were high. The fleet departed Kiel on 17 July, passed through the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal

The Kiel Canal (german: Nord-Ostsee-Kanal, literally "North- oEast alticSea canal", formerly known as the ) is a long freshwater canal in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein. The canal was finished in 1895, but later widened, and links the ...

to the North Sea, and continued to the Atlantic. stopped in Funchal

Funchal () is the largest city, the municipal seat and the capital of Portugal's Autonomous Region of Madeira, bordered by the Atlantic Ocean. The city has a population of 105,795, making it the sixth largest city in Portugal. Because of its high ...

in Madeira and A Coruña

A Coruña (; es, La Coruña ; historical English: Corunna or The Groyne) is a city and municipality of Galicia, Spain. A Coruña is the most populated city in Galicia and the second most populated municipality in the autonomous community and s ...

, Spain during the cruise. The fleet returned to Germany on 13 August. The autumn maneuvers followed from 27 August to 12 September. won the Kaiser's (Shooting Prize) for excellent shooting among armored cruisers for the 1907–1908 training year. During this period, Erich Raeder

Erich Johann Albert Raeder (24 April 1876 – 6 November 1960) was a German admiral who played a major role in the naval history of World War II. Raeder attained the highest possible naval rank, that of grand admiral, in 1939, becoming the f ...

served as the ship's navigation officer. In October, (''KzS''—Captain at Sea) Arthur Tapken took command of the ship; he served as the ship's commander until September 1909.

1909–1913

In February 1909, I Scouting Group went on another training cruise in the Atlantic; again stopped in Vigo from 17 to 23 February. After the ships' return to Germany, was detached to theEast Asia Squadron

The German East Asia Squadron (german: Kreuzergeschwader / Ostasiengeschwader) was an Imperial German Navy cruiser squadron which operated mainly in the Pacific Ocean between the mid-1890s until 1914, when it was destroyed at the Battle of the ...

on 11 March, vacating the flagship role, which again filled. Heeringen and the command staff returned to the ship the same day. The cruisers joined the High Seas Fleet for another Atlantic cruise in July and August, and visited Vilagarcía de Arousa

Vilagarcía de Arousa is a Spanish municipality in the Province of Pontevedra, Galicia. As of 2014 it has a population of 37,712, being ninth largest town in Galicia.

History

The present site of Vilagarcía has been occupied since prehistori ...

from 18 to 26 July. On the way back to Germany, the fleet stopped in Spithead

Spithead is an area of the Solent and a roadstead off Gilkicker Point in Hampshire, England. It is protected from all winds except those from the southeast. It receives its name from the Spit, a sandbank stretching south from the Hampshire ...

, Britain, where it was received by the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

. By early 1910, the new armored cruiser was ready for service with the fleet, and so now-''VAdm'' Heeringen hauled down his flag from on 25 April and transferred to the new vessel two days later. thereafter became the flagship of ''KAdm'' Reinhard Koch, the deputy commander of the group. Already on 16 May, Koch was replaced by ''KAdm'' Gustav Bachmann

Gustav Bachmann (July 13, 1860 in Cammin, Rostock – August 31, 1943 in Kiel) was a German naval officer, and an admiral in World War I.

Life

Family

Bachmann was the son of the farmer Julius Bachmann (1828—1890) and his wife Anna Bachman ...

, who was in turn replaced by ''KAdm'' Maximilian von Spee

Maximilian Johannes Maria Hubert Reichsgraf von Spee (22 June 1861 – 8 December 1914) was a naval officer of the German ''Kaiserliche Marine'' (Imperial Navy), who commanded the East Asia Squadron during World War I. Spee entered the navy in ...

on 15 September when Bachmann succeeded Heeringen as the group commander. won the for the 1909–1910 year. ''KzS'' Ludwig von Reuter served as the ship's commander from September 1910.

While in the shipyard for maintenance on 31 March 1911, a benzene

Benzene is an organic chemical compound with the molecular formula C6H6. The benzene molecule is composed of six carbon atoms joined in a planar ring with one hydrogen atom attached to each. Because it contains only carbon and hydrogen atoms ...

explosion in the ship's aft-most boiler room killed one man and injured several, preventing from taking part in unit maneuvers. On 1 October, ''KzS'' and (Commodore) Franz von Hipper

Franz Ritter von Hipper (13 September 1863 – 25 May 1932) was an admiral in the German Imperial Navy (''Kaiserliche Marine''). Franz von Hipper joined the German Navy in 1881 as an officer cadet. He commanded several torpedo boat units an ...

replaced Spee, after which the ship joined a cruise to Norway and Sweden in November. She visited Uddevalla

Uddevalla (old no, Oddevold) is a town and the seat of Uddevalla Municipality in Västra Götaland County, Sweden. In 2015, it had a population of 34 781.

It is located at a bay of the south-eastern part of Skagerrak. The beaches of Uddevalla ar ...

, Sweden from 3 to 6 November during the cruise. did not take part in the unit maneuvers conducted in February 1912. In March, and four light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to th ...

s filled I Scouting Group's role during fleet exercises, and during the maneuvers now-''VAdm'' Bachmann came aboard to direct their participation. During the exercises, Hipper temporarily transferred his flag to the new battlecruiser , but returned thereafter until 28 August. In September, (Frigate Captain) Max Köthner replaced Reuter as the ship's captain, though he served in the role only briefly before departing in November. The ship suffered an accident on 2 November when one of her pinnaces

Pinnace may refer to:

* Pinnace (ship's boat), a small vessel used as a tender to larger vessels among other things

* Full-rigged pinnace

The full-rigged pinnace was the larger of two types of vessel called a pinnace in use from the sixteenth c ...

accidentally detonated a naval mine

A naval mine is a self-contained explosive device placed in water to damage or destroy surface ships or submarines. Unlike depth charges, mines are deposited and left to wait until they are triggered by the approach of, or contact with, any ...

, killing two men and injuring two more.

was involved in another serious accident on 4 March 1913 during training exercises off Helgoland

Heligoland (; german: Helgoland, ; Heligolandic Frisian: , , Mooring Frisian: , da, Helgoland) is a small archipelago in the North Sea. A part of the German state of Schleswig-Holstein since 1890, the islands were historically possessions ...

. The torpedo boat attempted to pass in front of the ship but failed to clear her in time; s bow tore a hole into ''S178'' that flooded her engine and boiler rooms. ''S178'' sank within a few minutes of the accident and 69 men were killed in the accident. , the battleship , and the torpedo boat were only able to pull fifteen men from the sea. was only slightly damaged in the accident and continued with the maneuvers. ''KAdm'' Felix Funke and Bachmann alternated periods aboard , with Funke flying his flag from 7 to 14 March, followed by Bachmann from 14 March to 1 May, and finally Funke from 1 to 17 May. thereafter steamed to Kiel, where on 21 May she was decommissioned, the last armored cruiser to serve with I Scouting Group. She thereafter underwent an overhaul and was placed in reserve. Most of her crew transferred to the newly completed battlecruiser .

World War I

Following the outbreak ofWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in July 1914, was mobilized

Mobilization is the act of assembling and readying military troops and supplies for war. The word ''mobilization'' was first used in a military context in the 1850s to describe the preparation of the Prussian Army. Mobilization theories and ...

for active service; she was recommissioned on 12 August. Initially assigned to IV Scouting Group, on 25 August she was transferred to III Scouting Group, under the command of ''KAdm'' Hubert von Rebeur-Paschwitz

''Vizeadmiral'' Hubert von Rebeur-Paschwitz (14 August 1863 Frankfurt (Oder) – 16 February 1933 (Dresden)) was a German admiral. In 1899 he served as the German Naval attaché to Washington and later in 1912 commanded a flotilla of German ves ...

. Beginning on 20 September, she was tasked with guarding the German Bight

The German Bight (german: Deutsche Bucht; da, tyske bugt; nl, Duitse bocht; fry, Dútske bocht; ; sometimes also the German Bay) is the southeastern bight of the North Sea bounded by the Netherlands and Germany to the south, and Denmark and ...

. The ships of III Scouting Group transferred temporarily to the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and ...

two days later for a sortie into the central Baltic, as far north as Östergarn

Östergarn () is a populated area, a ''socken'' (not to be confused with parish), on the Swedish island of Gotland. It comprises the same area as the administrative Östergarn District, established on 1January 2016.

Geography

Östergarn is sit ...

, from 22 to 29 September. They then returned to the North Sea and rejoined the High Seas Fleet.

On 3 November, participated in the first offensive operation of the war conducted by the German fleet. I Scouting Group, by now commanded by ''RAdm'' Hipper, was to bombard Yarmouth on the British coast while the bulk of the High Seas Fleet sailed behind, providing distant support in the event that the raid provoked a British counterattack. and the rest of III Scouting Group provided the reconnaissance screen for the main fleet. Hipper's ships inflicted little damage and minelayer

A minelayer is any warship, submarine or military aircraft deploying explosive mines. Since World War I the term "minelayer" refers specifically to a naval ship used for deploying naval mines. "Mine planting" was the term for installing control ...

s laid minefields off the coast, which later sank the British submarine . Upon returning to Wilhelmshaven

Wilhelmshaven (, ''Wilhelm's Harbour''; Northern Low Saxon: ''Willemshaven'') is a coastal town in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is situated on the western side of the Jade Bight, a bay of the North Sea, and has a population of 76,089. Wilhelmsh ...

late that day, the German ships encountered heavy fog that prevented them from safely navigating the defensive minefields that had been laid outside the port. Instead, they anchored in the Schillig

Schillig is a village in the Friesland district of Lower Saxony in Germany. It is situated on the west coast of Jade Bay and is north of the town of Wilhelmshaven

Wilhelmshaven (, ''Wilhelm's Harbour''; Northern Low Saxon: ''Willemshaven'' ...

roadstead.

s commander, ''KzS'' Pieper, believed the fog to have cleared sufficiently to allow the vessel to return to port, so he ordered the ship to get underway. The pilot

An aircraft pilot or aviator is a person who controls the flight of an aircraft by operating its directional flight controls. Some other aircrew members, such as navigators or flight engineers, are also considered aviators, because they a ...

refused to take responsibility for maneuvering the ship owing to the great danger of trying to pass through the minefields under the foggy conditions. At 04:10, struck a mine and began to turn to exit the minefield, striking a second mine shortly thereafter. She quickly sank with heavy loss of life, though sources disagree on the number of fatalities. The naval historian V. E. Tarrant states that 127 out of a crew of 629 were rescued; Erich Gröner contends that there were only 336 deaths. The naval historians Hans Hildebrand, Albert Röhr, and Hans-Otto Steinmetz concur with Gröner on the number of fatalities and note that 381 men, including Pieper, were rescued by the coastal defense ship

Coastal defence ships (sometimes called coastal battleships or coast defence ships) were warships built for the purpose of coastal defence, mostly during the period from 1860 to 1920. They were small, often cruiser-sized warships that sacrifi ...

.

For his reckless handling of the ship, Pieper was tried in a court-martial, convicted, and sentenced to two years' imprisonment for negligence, disobedience of orders, and homicide through negligence. The wreck, located between Horumersiel and Hooksiel

Wangerland is a municipality in the district of Friesland, Lower Saxony, Germany. It is situated on the North Sea coast, approximately 20 km northwest of Wilhelmshaven, and 10 km north of Jever

Jever () is the capital of the district o ...

, was initially marked to allow vessels to pass safely. Beginning in 1926, the wreck was partially scrapped to reduce the navigational hazard to deeper-draft vessels. More work was done in 1936–1937 for the same reason. During a series of construction programs to expand the entrance to the Jade after World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, the ship's turrets were removed in 1969 and the remaining parts of the hull were demolished in 1983 to further clear the sea floor.

Notes

Footnotes

Citations

References

* * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Yorck Roon-class cruisers Ships built in Hamburg 1904 ships World War I cruisers of Germany World War I shipwrecks in the North Sea Maritime incidents in November 1914 Ships sunk by mines