SMS Moltke on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

SMS was the

In July 1912, escorted Kaiser Wilhelm II's yacht to

In July 1912, escorted Kaiser Wilhelm II's yacht to

During the night of 15 December, the main body of the High Seas Fleet encountered British destroyers. Fearing the prospect of a nighttime torpedo attack, Ingenohl ordered the ships to retreat. Hipper was unaware of Ingenohl's reversal, and so he continued with the bombardment. Upon reaching the British coast, Hipper's battlecruisers split into two groups. , , and went north to shell Hartlepool, while and went south to shell Scarborough and Whitby. During the bombardment of Hartlepool, was struck by a shell from a coastal battery, which caused minor damage between decks, but no casualties. was hit six times and three times by the coastal battery. By 09:45 on the 16th, the two groups had reassembled, and they began to retreat eastward.

By this time, Beatty's battlecruisers were in position to block Hipper's chosen egress route, while other forces were en route to complete the encirclement. At 12:25, the light cruisers of II Scouting Group began to pass through the British forces searching for Hipper. One of the cruisers in the

During the night of 15 December, the main body of the High Seas Fleet encountered British destroyers. Fearing the prospect of a nighttime torpedo attack, Ingenohl ordered the ships to retreat. Hipper was unaware of Ingenohl's reversal, and so he continued with the bombardment. Upon reaching the British coast, Hipper's battlecruisers split into two groups. , , and went north to shell Hartlepool, while and went south to shell Scarborough and Whitby. During the bombardment of Hartlepool, was struck by a shell from a coastal battery, which caused minor damage between decks, but no casualties. was hit six times and three times by the coastal battery. By 09:45 on the 16th, the two groups had reassembled, and they began to retreat eastward.

By this time, Beatty's battlecruisers were in position to block Hipper's chosen egress route, while other forces were en route to complete the encirclement. At 12:25, the light cruisers of II Scouting Group began to pass through the British forces searching for Hipper. One of the cruisers in the

also took part in the bombardment of Yarmouth and Lowestoft on 24–25 April. Hipper was away on sick leave, so the German ships were under the command of ''KAdm'' Friedrich Boedicker. The German battlecruisers , , , and left the Jade Estuary at 10:55 on 24 April, and were supported by a screening force of six light cruisers and two torpedo boat flotillas. The heavy units of the High Seas Fleet sailed at 13:40, with the objective to provide distant support for Boedicker's ships. The British Admiralty was made aware of the German sortie through the interception of German

also took part in the bombardment of Yarmouth and Lowestoft on 24–25 April. Hipper was away on sick leave, so the German ships were under the command of ''KAdm'' Friedrich Boedicker. The German battlecruisers , , , and left the Jade Estuary at 10:55 on 24 April, and were supported by a screening force of six light cruisers and two torpedo boat flotillas. The heavy units of the High Seas Fleet sailed at 13:40, with the objective to provide distant support for Boedicker's ships. The British Admiralty was made aware of the German sortie through the interception of German

, and the rest of Hipper's battlecruisers in I Scouting Group, lay anchored in the outer Jade Roads on the night of 30 May 1916. The following morning, at 02:00 CEST, the ships slowly steamed out towards the Skagerrak at a speed of . was the fourth ship in the line of five, ahead of , and to the rear of . II Scouting Group, consisting of the light cruisers , Boedicker's flagship, , , and , and 30 torpedo boats of II, VI, and IX Flotillas, accompanied Hipper's battlecruisers.

An hour and a half later, the High Seas Fleet under the command of Admiral Reinhard Scheer left the Jade; the force was composed of 16 dreadnoughts. The High Seas Fleet was accompanied by IV Scouting Group, composed of the light cruisers , , , , and , and 31 torpedo boats of I, III, V, and VII Flotillas, led by the light cruiser . The six pre-dreadnoughts of II Battle Squadron had departed from the Elbe roads at 02:45, and rendezvoused with the battle fleet at 5:00.

, and the rest of Hipper's battlecruisers in I Scouting Group, lay anchored in the outer Jade Roads on the night of 30 May 1916. The following morning, at 02:00 CEST, the ships slowly steamed out towards the Skagerrak at a speed of . was the fourth ship in the line of five, ahead of , and to the rear of . II Scouting Group, consisting of the light cruisers , Boedicker's flagship, , , and , and 30 torpedo boats of II, VI, and IX Flotillas, accompanied Hipper's battlecruisers.

An hour and a half later, the High Seas Fleet under the command of Admiral Reinhard Scheer left the Jade; the force was composed of 16 dreadnoughts. The High Seas Fleet was accompanied by IV Scouting Group, composed of the light cruisers , , , , and , and 31 torpedo boats of I, III, V, and VII Flotillas, led by the light cruiser . The six pre-dreadnoughts of II Battle Squadron had departed from the Elbe roads at 02:45, and rendezvoused with the battle fleet at 5:00.

Shortly before 16:00, Hipper's force encountered Beatty's battlecruiser squadron. The German ships were the first to open fire, at a range of approximately 15,000 yards (14,000 m). When the British ships began returning fire, confusion amongst the British battlecruisers resulted in being engaged by both ''New Zealand'' and ''Tiger''. The British rangefinders had misread the range to their German targets, and so the first salvos fired by the British ships fell a mile past the German battlecruisers. At 16:52, hit ''Tiger'' with two main gun shells, but neither of these hits caused any significant damage. then fired a further four shells, two of which hit simultaneously on the midships and after turrets, knocking both out for a significant period of the battle.

Approximately 15 minutes later, the British battlecruiser was suddenly destroyed by . Shortly thereafter, fired four torpedoes at ''Queen Mary'' at a range between . This caused the British line to fall into disarray, as the torpedoes were thought to have been fired by U-boats. At this point, Hipper's battlecruisers had come into range of the V Battle Squadron, composed of the new s, which mounted powerful guns. At 17:06, opened fire on . She was joined a few minutes later by , ''Malaya'', and ; the ships concentrated their fire on and . At 17:16, one of the 15 in shells from the fast battleships struck , where it pierced a coal bunker, tore into a casemate deck, and ignited ammunition stored therein. The explosion burned the ammunition hoist down to the magazine.

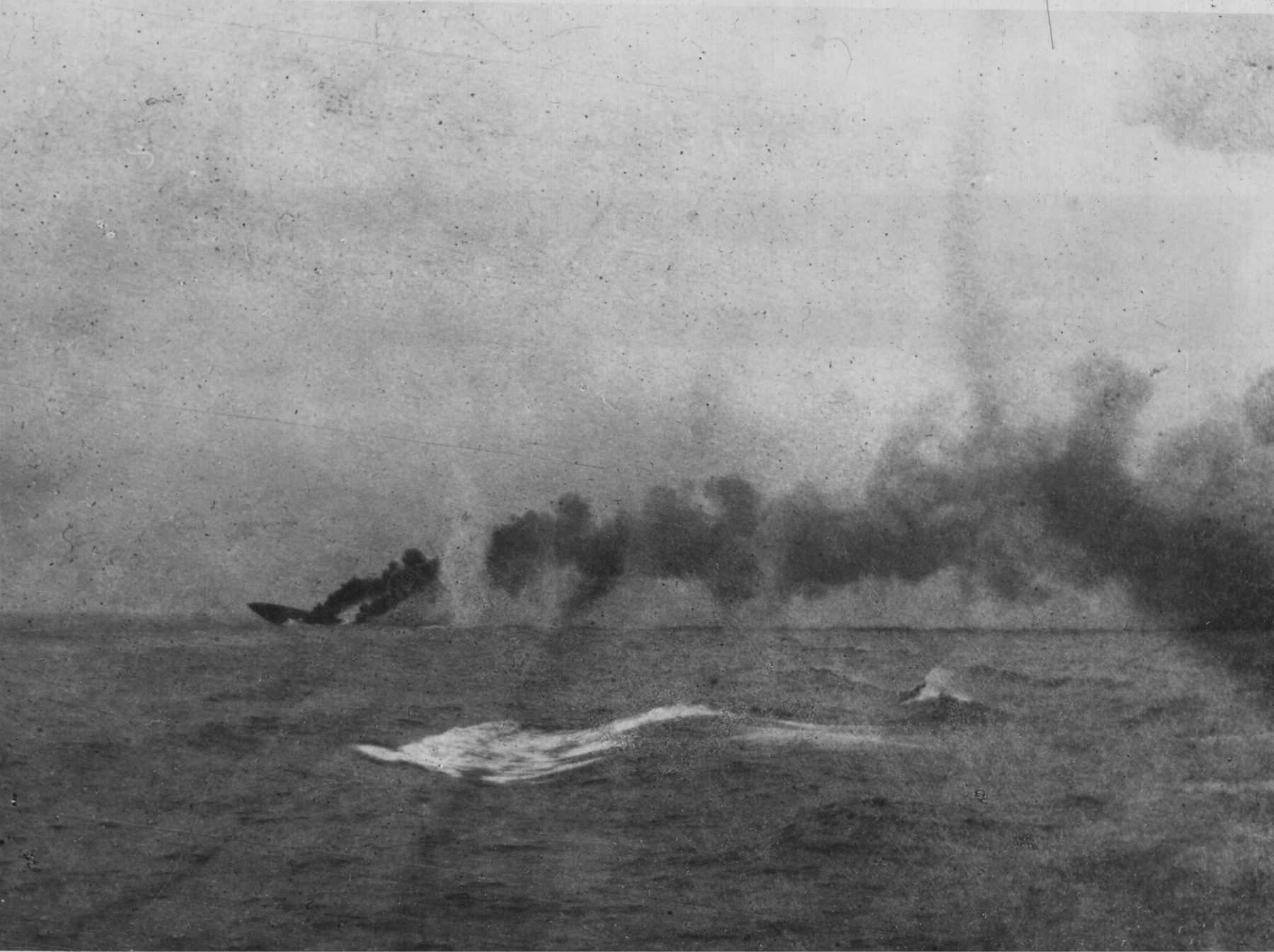

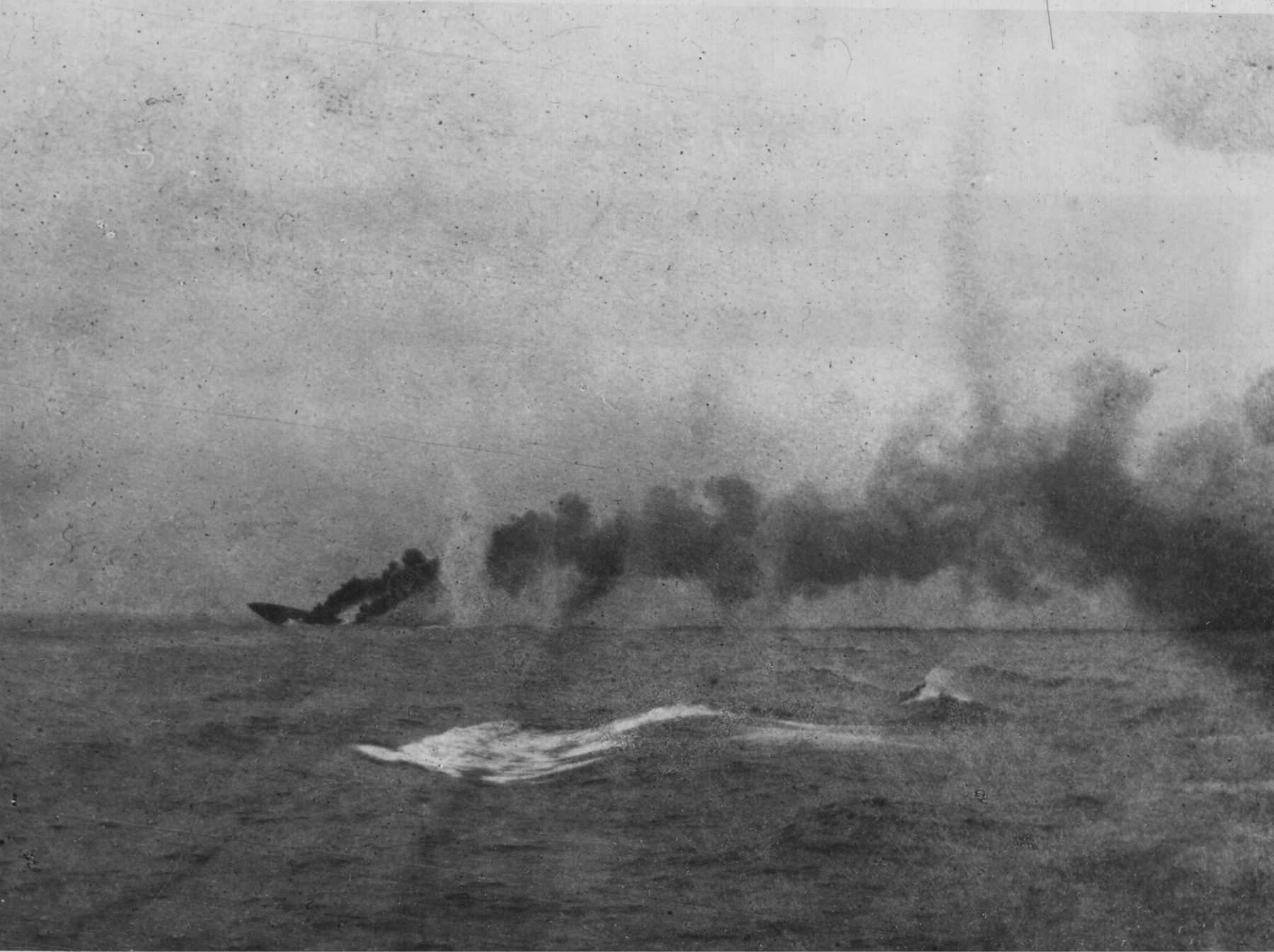

and changed their speed and direction, which threw off the aim of the V Battle Squadron and earned the battered ships a short respite. While and were drawing the fire of the V Battle Squadron battleships, and were able to concentrate their fire on the British battlecruisers; between 17:25 and 17:30, at least five shells from and struck ''Queen Mary'', causing a catastrophic explosion that destroyed the ship. s commander, von Karpf, remarked that "The enemy's salvos lie well and close; their salvos are fired in rapid succession, the fire discipline is excellent!"

Shortly before 16:00, Hipper's force encountered Beatty's battlecruiser squadron. The German ships were the first to open fire, at a range of approximately 15,000 yards (14,000 m). When the British ships began returning fire, confusion amongst the British battlecruisers resulted in being engaged by both ''New Zealand'' and ''Tiger''. The British rangefinders had misread the range to their German targets, and so the first salvos fired by the British ships fell a mile past the German battlecruisers. At 16:52, hit ''Tiger'' with two main gun shells, but neither of these hits caused any significant damage. then fired a further four shells, two of which hit simultaneously on the midships and after turrets, knocking both out for a significant period of the battle.

Approximately 15 minutes later, the British battlecruiser was suddenly destroyed by . Shortly thereafter, fired four torpedoes at ''Queen Mary'' at a range between . This caused the British line to fall into disarray, as the torpedoes were thought to have been fired by U-boats. At this point, Hipper's battlecruisers had come into range of the V Battle Squadron, composed of the new s, which mounted powerful guns. At 17:06, opened fire on . She was joined a few minutes later by , ''Malaya'', and ; the ships concentrated their fire on and . At 17:16, one of the 15 in shells from the fast battleships struck , where it pierced a coal bunker, tore into a casemate deck, and ignited ammunition stored therein. The explosion burned the ammunition hoist down to the magazine.

and changed their speed and direction, which threw off the aim of the V Battle Squadron and earned the battered ships a short respite. While and were drawing the fire of the V Battle Squadron battleships, and were able to concentrate their fire on the British battlecruisers; between 17:25 and 17:30, at least five shells from and struck ''Queen Mary'', causing a catastrophic explosion that destroyed the ship. s commander, von Karpf, remarked that "The enemy's salvos lie well and close; their salvos are fired in rapid succession, the fire discipline is excellent!"

A pause in the battle at dusk allowed and the other German battlecruisers to cut away wreckage that interfered with the main guns, extinguish fires, repair the fire control and signal equipment, and ready the searchlights for nighttime action. During this period, the German fleet reorganized into a well-ordered formation in reverse order, when the German light forces encountered the British screen shortly after 21:00. The renewed gunfire gained Beatty's attention, so he turned his battlecruisers westward. At 21:09, he sighted the German battlecruisers, and drew to within before opening fire at 20:20. The attack from the British battlecruisers completely surprised Hipper, who had been in the process of boarding from the torpedo boat . The German ships returned fire with every gun available, and at 21:32 hit both ''Lion'' and ''Princess Royal'' in the darkness. The maneuvering of the German battlecruisers forced the leading I Battle Squadron to turn westward to avoid collision. This brought the pre-dreadnoughts of II Battle Squadron directly behind the battlecruisers, and prevented the British ships from pursuing the German battlecruisers when they turned southward. The British battlecruisers opened fire on the old battleships; the German ships turned southwest to bring all of their guns to bear against the British ships.

By 22:15, Hipper was finally able to transfer to , and then ordered his ships to steam at towards the head of the German line. However, only and were in condition to comply; and could make at most 18 knots, and so these ships lagged behind. and were in the process of steaming to the front of the line when the ships passed close to , which forced the ship to drastically slow down to avoid collision. This forced , , and to turn to port, which led them into contact with the 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron; at a range of , the cruisers on both sides pummeled each other. ''KADm''

A pause in the battle at dusk allowed and the other German battlecruisers to cut away wreckage that interfered with the main guns, extinguish fires, repair the fire control and signal equipment, and ready the searchlights for nighttime action. During this period, the German fleet reorganized into a well-ordered formation in reverse order, when the German light forces encountered the British screen shortly after 21:00. The renewed gunfire gained Beatty's attention, so he turned his battlecruisers westward. At 21:09, he sighted the German battlecruisers, and drew to within before opening fire at 20:20. The attack from the British battlecruisers completely surprised Hipper, who had been in the process of boarding from the torpedo boat . The German ships returned fire with every gun available, and at 21:32 hit both ''Lion'' and ''Princess Royal'' in the darkness. The maneuvering of the German battlecruisers forced the leading I Battle Squadron to turn westward to avoid collision. This brought the pre-dreadnoughts of II Battle Squadron directly behind the battlecruisers, and prevented the British ships from pursuing the German battlecruisers when they turned southward. The British battlecruisers opened fire on the old battleships; the German ships turned southwest to bring all of their guns to bear against the British ships.

By 22:15, Hipper was finally able to transfer to , and then ordered his ships to steam at towards the head of the German line. However, only and were in condition to comply; and could make at most 18 knots, and so these ships lagged behind. and were in the process of steaming to the front of the line when the ships passed close to , which forced the ship to drastically slow down to avoid collision. This forced , , and to turn to port, which led them into contact with the 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron; at a range of , the cruisers on both sides pummeled each other. ''KADm''  Close to the end of the battle, at 03:55, Hipper transmitted a report to Scheer informing him of the tremendous damage his ships had suffered. By that time, and each had only two guns in operation, was flooded with 1,000 tons of water, and was severely damaged. Hipper reported: "I Scouting Group was therefore no longer of any value for a serious engagement, and was consequently directed to return to harbour by the Commander-in-Chief, while he himself determined to await developments off Horns Reef with the battlefleet."

During the course of the battle, had hit ''Tiger'' 13 times, and was hit herself 4 times, all by shells. The No. 5 starboard 15 cm gun was struck by one of the 15 in shells and put out of action for the remainder of the battle. The ship suffered 16 dead and 20 wounded, the majority of which were due to the hit on the 15 cm gun. Flooding and counter-flooding efforts caused 1,000 tons of water to enter the ship.

Close to the end of the battle, at 03:55, Hipper transmitted a report to Scheer informing him of the tremendous damage his ships had suffered. By that time, and each had only two guns in operation, was flooded with 1,000 tons of water, and was severely damaged. Hipper reported: "I Scouting Group was therefore no longer of any value for a serious engagement, and was consequently directed to return to harbour by the Commander-in-Chief, while he himself determined to await developments off Horns Reef with the battlefleet."

During the course of the battle, had hit ''Tiger'' 13 times, and was hit herself 4 times, all by shells. The No. 5 starboard 15 cm gun was struck by one of the 15 in shells and put out of action for the remainder of the battle. The ship suffered 16 dead and 20 wounded, the majority of which were due to the hit on the 15 cm gun. Flooding and counter-flooding efforts caused 1,000 tons of water to enter the ship.

was to have taken part in what would have amounted to the "death ride" of the High Seas Fleet shortly before the end of World War I. The bulk of the High Seas Fleet was to have sortied from their base in Wilhelmshaven to engage the British Grand Fleet; Scheer—by now the (Grand Admiral) of the fleet—intended to inflict as much damage as possible on the British navy, in order to retain a better bargaining position for Germany, whatever the cost to the fleet. However, while the fleet was consolidating in Wilhelmshaven, war-weary sailors began deserting en masse. As and passed through the locks that separated Wilhelmshaven's inner harbor and roadstead, some 300 men from both ships climbed over the side and disappeared ashore.

On 24 October 1918, the order was given to sail from Wilhelmshaven. Starting on the night of 29 October, sailors on several battleships

was to have taken part in what would have amounted to the "death ride" of the High Seas Fleet shortly before the end of World War I. The bulk of the High Seas Fleet was to have sortied from their base in Wilhelmshaven to engage the British Grand Fleet; Scheer—by now the (Grand Admiral) of the fleet—intended to inflict as much damage as possible on the British navy, in order to retain a better bargaining position for Germany, whatever the cost to the fleet. However, while the fleet was consolidating in Wilhelmshaven, war-weary sailors began deserting en masse. As and passed through the locks that separated Wilhelmshaven's inner harbor and roadstead, some 300 men from both ships climbed over the side and disappeared ashore.

On 24 October 1918, the order was given to sail from Wilhelmshaven. Starting on the night of 29 October, sailors on several battleships

lead ship

The lead ship, name ship, or class leader is the first of a series or class of ships all constructed according to the same general design. The term is applicable to naval ships and large civilian vessels.

Large ships are very complex and may ...

of the s of the German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

Imperial Navy, named after the 19th-century German Field Marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, ordinarily senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army and as such few persons are appointed to it. It is considered as ...

Helmuth von Moltke. Commissioned on 30 September 1911, the ship was the second battlecruiser of the Imperial Navy. , along with her sister ship

A sister ship is a ship of the same class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They often share a ...

, was an enlarged version of the previous German battlecruiser design, , with increased armor protection and two more main guns in an additional turret

Turret may refer to:

* Turret (architecture), a small tower that projects above the wall of a building

* Gun turret, a mechanism of a projectile-firing weapon

* Objective turret, an indexable holder of multiple lenses in an optical microscope

* M ...

. Compared to her British rivals—the — and her sister were significantly larger and better armored.

The ship participated in most of the major fleet actions conducted by the German Navy during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, including the Battles of Dogger Bank

Dogger Bank ( Dutch: ''Doggersbank'', German: ''Doggerbank'', Danish: ''Doggerbanke'') is a large sandbank in a shallow area of the North Sea about off the east coast of England.

During the last ice age the bank was part of a large landmass ...

and Jutland

Jutland ( da, Jylland ; german: Jütland ; ang, Ēota land ), known anciently as the Cimbric or Cimbrian Peninsula ( la, Cimbricus Chersonesus; da, den Kimbriske Halvø, links=no or ; german: Kimbrische Halbinsel, links=no), is a peninsula of ...

in the North Sea in 1915 and 1916, respectively. She also took part in the Battle of the Gulf of Riga

The Battle of the Gulf of Riga was a World War I naval operation of the German High Seas Fleet against the Russian Baltic Fleet in the Gulf of Riga in the Baltic Sea in August 1915. The operation's objective was to destroy the Russian naval for ...

in 1915 and Operation Albion

Operation Albion was a World War I German air, land and naval operation against the Russian forces in October 1917 to occupy the West Estonian Archipelago. The land campaign opened with German landings at the Tagalaht bay on the island o ...

in 1917 in the Baltic. was damaged several times during the war: the ship was hit by heavy-caliber gunfire at Jutland, and torpedoed twice by British submarines while on fleet advances.

Following the end of the war in 1918, , along with most of the High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet (''Hochseeflotte'') was the battle fleet of the German Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. The formation was created in February 1907, when the Home Fleet (''Heimatflotte'') was renamed as the High Seas ...

, was interned at Scapa Flow

Scapa Flow viewed from its eastern end in June 2009

Scapa Flow (; ) is a body of water in the Orkney Islands, Scotland, sheltered by the islands of Mainland, Graemsay, Burray,S. C. George, ''Jutland to Junkyard'', 1973. South Ronaldsay a ...

pending a decision by the Allies as to the fate of the fleet. The ship met her end when she was scuttled

Scuttling is the deliberate sinking of a ship. Scuttling may be performed to dispose of an abandoned, old, or captured vessel; to prevent the vessel from becoming a navigation hazard; as an act of self-destruction to prevent the ship from being ...

, along with the rest of the High Seas Fleet in 1919 to prevent them from falling into Allied hands. The wreck of was raised in 1927 and scrapped at Rosyth

Rosyth ( gd, Ros Fhìobh, "headland of Fife") is a town on the Firth of Forth, south of the centre of Dunfermline. According to the census of 2011, the town has a population of 13,440.

The new town was founded as a Garden city-style suburb ...

from 1927 to 1929.

Design

As the German (Imperial Navy) continued in itsarms race

An arms race occurs when two or more groups compete in military superiority. It consists of a competition between two or more states to have superior armed forces; a competition concerning production of weapons, the growth of a military, and ...

with the British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

in 1907, the (Imperial Navy Office) considered plans for the battlecruiser that was to be built for the following year. An increase in the budget raised the possibility of increasing the caliber of the main battery

A main battery is the primary weapon or group of weapons around which a warship is designed. As such, a main battery was historically a gun or group of guns, as in the broadsides of cannon on a ship of the line. Later, this came to be turreted ...

from the guns used in the previous battlecruiser, , to , but Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz

Alfred Peter Friedrich von Tirpitz (19 March 1849 – 6 March 1930) was a German grand admiral, Secretary of State of the German Imperial Naval Office, the powerful administrative branch of the German Imperial Navy from 1897 until 1916. Prussi ...

, the State Secretary of the Navy, opposed the increase, preferring to add a pair of 28 cm guns instead. The Construction Department supported the change, and ultimately two ships were authorized for the 1908 and 1909 building years; was the first, followed by .

was long overall, with a beam of and a draft

Draft, The Draft, or Draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a vesse ...

of fully loaded. The ship displaced normally, and at full load

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into wei ...

. was powered by four Parsons

Parsons may refer to:

Places

In the United States:

* Parsons, Kansas, a city

* Parsons, Missouri, an unincorporated community

* Parsons, Tennessee, a city

* Parsons, West Virginia, a town

* Camp Parsons, a Boy Scout camp in the state of Washingt ...

steam turbine

A steam turbine is a machine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work on a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Charles Parsons in 1884. Fabrication of a modern steam tu ...

s, with steam provided by twenty-four coal-fired Schulz-Thornycroft water-tube boiler

A high pressure watertube boiler (also spelled water-tube and water tube) is a type of boiler in which water circulates in tubes heated externally by the fire. Fuel is burned inside the furnace, creating hot gas which boils water in the steam-gen ...

s. The propulsion system was rated at and a top speed of . At , the ship had a range of . Her crew consisted on 43 officers and 1,010 enlisted men.

The ship was armed with a main battery of ten SK L/50 guns mounted in five twin-gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechanis ...

s; of these, one was placed forward, two were ''en echelon

An echelon formation () is a (usually military) formation in which its units are arranged diagonally. Each unit is stationed behind and to the right (a "right echelon"), or behind and to the left ("left echelon"), of the unit ahead. The name of ...

'' amidships

This glossary of nautical terms is an alphabetical listing of terms and expressions connected with ships, shipping, seamanship and navigation on water (mostly though not necessarily on the sea). Some remain current, while many date from the 17t ...

, and the other two were in a superfiring pair aft. Her secondary armament

Secondary armament is a term used to refer to smaller, faster-firing weapons that were typically effective at a shorter range than the main (heavy) weapons on military systems, including battleship- and cruiser-type warships, tanks/armored p ...

consisted of twelve SK L/45 guns placed in individual casemate

A casemate is a fortified gun emplacement or armored structure from which guns are fired, in a fortification, warship, or armoured fighting vehicle.Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary

When referring to antiquity, the term "casemate wall" me ...

s in the central portion of the ship and twelve SK L/45 guns, also in individual mounts in the bow, the stern, and around the forward conning tower

A conning tower is a raised platform on a ship or submarine, often armored, from which an officer in charge can conn the vessel, controlling movements of the ship by giving orders to those responsible for the ship's engine, rudder, lines, and gro ...

. She was also equipped with four submerged torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s, one in the bow, one in the stern, and one on each broadside

Broadside or broadsides may refer to:

Naval

* Broadside (naval), terminology for the side of a ship, the battery of cannon on one side of a warship, or their near simultaneous fire on naval warfare

Printing and literature

* Broadside (comic ...

.

The ship's armor consisted of Krupp cemented steel. The belt

Belt may refer to:

Apparel

* Belt (clothing), a leather or fabric band worn around the waist

* Championship belt, a type of trophy used primarily in combat sports

* Colored belts, such as a black belt or red belt, worn by martial arts practiti ...

was thick in the citadel

A citadel is the core fortified area of a town or city. It may be a castle, fortress, or fortified center. The term is a diminutive of "city", meaning "little city", because it is a smaller part of the city of which it is the defensive core.

In ...

where it covered the ship's ammunition magazines

A magazine is a periodical publication, generally published on a regular schedule (often weekly or monthly), containing a variety of content. They are generally financed by advertising, purchase price, prepaid subscriptions, or by a combination ...

and propulsion machinery spaces. The belt tapered down to on either end. The deck was thick, sloping downward at the side to connect to the bottom edge of the belt. The main battery gun turrets had faces, and they sat atop barbette

Barbettes are several types of gun emplacement in terrestrial fortifications or on naval ships.

In recent naval usage, a barbette is a protective circular armour support for a heavy gun turret. This evolved from earlier forms of gun protectio ...

s that were equally thick.

Service history

Pre-war

The contract for "Cruiser G" was awarded on 17 September 1908, and thekeel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element on a vessel. On some sailboats, it may have a hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose, as well. As the laying down of the keel is the initial step in the construction of a ship, in Br ...

was laid on 23 January 1909. Her launching

Ceremonial ship launching involves the performance of ceremonies associated with the process of transferring a vessel to the water. It is a nautical tradition in many cultures, dating back thousands of years, to accompany the physical pro ...

was scheduled for 22 March 1910, but work was delayed somewhat and the ceremony took place on 7 April 1910. At the launching of the ship on 7 April 1910, Helmuth von Moltke the Younger

Graf Helmuth Johannes Ludwig von Moltke (; 25 May 1848 – 18 June 1916), also known as Moltke the Younger, was a German general and Chief of the Great German General Staff. He was also the nephew of '' Generalfeldmarschall'' ''Graf'' Helmuth ...

christened her after his uncle, Helmuth von Moltke the Elder Helmuth is both a masculine German given name and a surname. Notable people with the name include:

Given name;

* Helmuth Theodor Bossert (1889–1961), German art historian, philologist and archaeologist

*Helmuth Duckadam (born 1959), Romanian form ...

, the chief of staff of the Prussian and later German General Staff during the wars of German unification

The unification of Germany (, ) was the process of building the modern German nation state with federal features based on the concept of Lesser Germany (one without multinational Austria), which commenced on 18 August 1866 with adoption of t ...

. On 11 September 1911, a crew composed of dockyard workers transferred the ship from Hamburg

Hamburg (, ; nds, label=Hamburg German, Low Saxon, Hamborg ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg (german: Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg; nds, label=Low Saxon, Friee un Hansestadt Hamborg),. is the List of cities in Germany by popul ...

to Kiel

Kiel () is the capital and most populous city in the northern German state of Schleswig-Holstein, with a population of 246,243 (2021).

Kiel lies approximately north of Hamburg. Due to its geographic location in the southeast of the Jutland ...

through the Skagerrak

The Skagerrak (, , ) is a strait running between the Jutland peninsula of Denmark, the southeast coast of Norway and the west coast of Sweden, connecting the North Sea and the Kattegat sea area through the Danish Straits to the Baltic Sea.

T ...

. On 30 September, the ship was commissioned, under the command of (''KzS''—Captain at Sea) Ernst von Mann. She thereafter began sea trials

A sea trial is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a "shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on open water, and i ...

, and though she had not yet formally entered service, the ship joined I Scouting Group

The I Scouting Group (german: I. Aufklärungsgruppe) was a special reconnaissance unit within the German Kaiserliche Marine. The unit was famously commanded by Admiral Franz von Hipper during World War I. The I Scouting Group was one of the most ...

, the fleet's main reconnaissance force. There she replaced the armored cruiser , which had been decommissioned on 22 September. In early November, the ships of I SG conducted a training cruise in the Kattegat

The Kattegat (; sv, Kattegatt ) is a sea area bounded by the Jutlandic peninsula in the west, the Danish Straits islands of Denmark and the Baltic Sea to the south and the provinces of Bohuslän, Västergötland, Halland and Skåne in Sweden ...

; a serious storm forced to shelter in Uddevalla

Uddevalla (old no, Oddevold) is a town and the seat of Uddevalla Municipality in Västra Götaland County, Sweden. In 2015, it had a population of 34 781.

It is located at a bay of the south-eastern part of Skagerrak. The beaches of Uddevalla ar ...

, Sweden, from 3 to 6 November. She spent the next several months completing her trials in the Danziger Bucht, and on 1 April 1912 the ship was pronounced ready for service.

The navy had intended to become the flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the ...

of I SG upon entering active service, but she instead received orders for a special voyage. In mid-1911, an American squadron had visited Kiel, and the Germans wanted to reciprocate by sending a group of German vessels to the United States. They selected and the light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to th ...

s and . The latter was already stationed in the waters off South America, and was to meet and at their destination, as part of a temporary cruiser division commanded by (''KAdm''—Rear Admiral) Hubert von Rebeur-Paschwitz

''Vizeadmiral'' Hubert von Rebeur-Paschwitz (14 August 1863 Frankfurt (Oder) – 16 February 1933 (Dresden)) was a German admiral. In 1899 he served as the German Naval attaché to Washington and later in 1912 commanded a flotilla of German vess ...

. On 11 May, the two ships left Kiel, passed through the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; es, :es:Canarias, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to ...

, and arrived off Cape Henry

Cape Henry is a cape on the Atlantic shore of Virginia located in the northeast corner of Virginia Beach. It is the southern boundary of the entrance to the long estuary of the Chesapeake Bay.

Across the mouth of the bay to the north is Cape Ch ...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

, on 30 May, where joined them. The three ships then entered Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads is the name of both a body of water in the United States that serves as a wide channel for the James, Nansemond and Elizabeth rivers between Old Point Comfort and Sewell's Point where the Chesapeake Bay flows into the Atlantic ...

on 3 June; the President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal gove ...

, William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

, received the ships aboard the presidential yacht

A yacht is a sailing or power vessel used for pleasure, cruising, or racing. There is no standard definition, though the term generally applies to vessels with a cabin intended for overnight use. To be termed a , as opposed to a , such a pleasu ...

. Also present was a contingent from the Atlantic Fleet. On 8–9 June, the ships sailed to New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, where the crews were well-received by both local German clubs and the upper class

Upper class in modern societies is the social class composed of people who hold the highest social status, usually are the wealthiest members of class society, and wield the greatest political power. According to this view, the upper class is gen ...

. The ships departed New York on 13 June, sailing for Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore was ...

while and returned to Kiel. They arrived there on 24 June, and the following day, the cruiser squadron was dissolved. was the only German capital ship

The capital ships of a navy are its most important warships; they are generally the larger ships when compared to other warships in their respective fleet. A capital ship is generally a leading or a primary ship in a naval fleet.

Strategic im ...

to ever visit the United States.

In July 1912, escorted Kaiser Wilhelm II's yacht to

In July 1912, escorted Kaiser Wilhelm II's yacht to Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

to meet Czar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East and South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word '' caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" in the European medieval sense of the t ...

Nicholas II

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov; spelled in pre-revolutionary script. ( 186817 July 1918), known in the Russian Orthodox Church as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer,. was the last Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Pol ...

. The voyage lasted from 4 to 6 July. Upon returning, s commander was replaced by ''KzS'' Magnus von Levetzow, and the ship began her tenure as flagship of I SG, under the command of (''VAdm''—Vice Admiral) Gustav Bachmann

Gustav Bachmann (July 13, 1860 in Cammin, Rostock – August 31, 1943 in Kiel) was a German naval officer, and an admiral in World War I.

Life

Family

Bachmann was the son of the farmer Julius Bachmann (1828—1890) and his wife Anna Bachman ...

. At that time, the unit consisted of , , the armored cruiser , the light cruisers , , , , , and , and the aviso

An ''aviso'' was originally a kind of dispatch boat or "advice boat", carrying orders before the development of effective remote communication.

The term, derived from the Portuguese and Spanish word for "advice", "notice" or "warning", an ...

, then serving as a tender. The ships took part in the annual fleet maneuvers held in August and September, which concluded with a naval review

A fleet review or naval review is an event where a gathering of ships from a particular navy is paraded and reviewed by an incumbent head of state and/or other official civilian and military dignitaries. A number of national navies continue to ...

for Kaiser

''Kaiser'' is the German word for "emperor" (female Kaiserin). In general, the German title in principle applies to rulers anywhere in the world above the rank of king (''König''). In English, the (untranslated) word ''Kaiser'' is mainly ap ...

Wilhelm II

, house = Hohenzollern

, father = Frederick III, German Emperor

, mother = Victoria, Princess Royal

, religion = Lutheranism (Prussian United)

, signature = Wilhelm II, German Emperor Signature-.svg

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor ...

in the German Bight

The German Bight (german: Deutsche Bucht; da, tyske bugt; nl, Duitse bocht; fry, Dútske bocht; ; sometimes also the German Bay) is the southeastern bight of the North Sea bounded by the Netherlands and Germany to the south, and Denmark and ...

. On 19 September, was awarded the Kaiser's (Shooting Prize) for large cruisers. visited Malmö

Malmö (, ; da, Malmø ) is the largest city in the Swedish county (län) of Scania (Skåne). It is the third-largest city in Sweden, after Stockholm and Gothenburg, and the sixth-largest city in the Nordic region, with a municipal popul ...

, Sweden, and took part in training exercises later that year. In December, the ship was dry dock

A dry dock (sometimes drydock or dry-dock) is a narrow basin or vessel that can be flooded to allow a load to be floated in, then drained to allow that load to come to rest on a dry platform. Dry docks are used for the construction, maintenance, ...

ed in Wilhelmshaven

Wilhelmshaven (, ''Wilhelm's Harbour''; Northern Low Saxon: ''Willemshaven'') is a coastal town in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is situated on the western side of the Jade Bight, a bay of the North Sea, and has a population of 76,089. Wilhelmsh ...

for periodic maintenance that lasted until February 1913.

While underwent maintenance, Bachmann transferred his flag to until 19 February, when he returned to . Upon returning to service, the ship took part in squadron and fleet training exercises in the KAttegat and the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian ...

in February and March. On 14 March, Bachmann temporarily transferred back to before returning to on 1 May. By that time, and the new light cruiser had been sent to the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

in response to the First Balkan War

The First Balkan War ( sr, Први балкански рат, ''Prvi balkanski rat''; bg, Балканска война; el, Αʹ Βαλκανικός πόλεμος; tr, Birinci Balkan Savaşı) lasted from October 1912 to May 1913 and invo ...

, was out of service for maintenance, had been decommissioned, and the new battlecruiser had not yet commissioned, leaving I SG under strength for the fleet maneuvers scheduled for May. The large armored cruiser , then serving as the artillery school training ship

A training ship is a ship used to train students as sailors. The term is mostly used to describe ships employed by navies to train future officers. Essentially there are two types: those used for training at sea and old hulks used to house class ...

, was temporarily assigned to I SG to make up the shortfall. Following the maneuvers, the unit cruised with the rest of the High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet (''Hochseeflotte'') was the battle fleet of the German Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. The formation was created in February 1907, when the Home Fleet (''Heimatflotte'') was renamed as the High Seas ...

from 15 July to 10 August, which included a lengthy visit to Norway. During this period, visited Lærdalsøyri

Lærdalsøyri is the administrative centre of Lærdal Municipality in Vestland county, Norway. The village is located along the Lærdalselvi river where it empties into the Lærdalsfjorden, a branch off of the main Sognefjorden. The village is l ...

, Norway, from 27 July to 3 August. After the unit returned home, joined it on 17 August. ''KAdm'' Franz Hipper replaced Bachmann as the unit commander on 30 September, though he did not arrive aboard the ship until 15 October, as he had been on vacation at the time.

In November, was present for fleet exercises in the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

. The ships of I SG conducted unit maneuvers in February 1914 in the North and Baltic Seas. In late March, the fleet assembled for another period of training exercises that lasted into early May. On 23 June, Hipper transferred his flag to . There was some consideration given to deploying to the Far East in order to replace the armored cruiser , but the plan was abandoned when it became apparent that needed a major overhaul and would need to be replaced in the Mediterranean. was then scheduled to transfer to replace her sister ship, but this plan was interrupted by the outbreak of World War I in July.

World War I

Battle of Heligoland Bight

Shortly after the outbreak of World War I, on 28 August 1914, participated in the Battle of Heligoland Bight. During the morning, British cruisers from theHarwich Force

The Harwich Force originally called Harwich Striking Force was a squadron of the Royal Navy, formed during the First World War and based in Harwich. It played a significant role in the war.

History

After the outbreak of the First World War, a ...

attacked the German destroyers patrolling the Heligoland Bight. Six German light cruisers—, , , , , and —responded to the attack and inflicted serious damage to the British raiders. However, the arrival at approximately 13:37 of the British 1st Battlecruiser Squadron, under the command of Vice Admiral David Beatty, quickly put the German ships at a disadvantage.

Along with the rest of the I Scouting Group battlecruisers, was stationed in the Wilhelmshaven Roads on the morning of the battle. By 08:50, Hipper had requested permission from Admiral Friedrich von Ingenohl

Gustav Heinrich Ernst Friedrich von Ingenohl (30 June 1857 – 19 December 1933) was a German admiral from Neuwied best known for his command of the German High Seas Fleet at the beginning of World War I.

He was the son of a tradesman. ...

, the commander of the High Seas Fleet, to send and to relieve the beleaguered German cruisers. was ready to sail by 12:10, but the low tide

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

Tide tables ...

prevented the ships from being able to pass over the sand bar

In oceanography, geomorphology, and geoscience, a shoal is a natural submerged ridge, bank, or bar that consists of, or is covered by, sand or other unconsolidated material and rises from the bed of a body of water to near the surface. It ...

at the mouth of the Jade Estuary safely. At 14:10, and were able to cross the Jade bar; Hipper ordered the German cruisers to fall back to his ships, while Hipper himself was about an hour behind in the battlecruiser . At 14:25, the remaining light cruisers—, , , , and —rendezvoused with the battlecruisers. arrived on the scene by 15:10, while succumbed to battle damage and sank. Hipper ventured forth cautiously to search for the two missing light cruisers, and , which had already sunk. By 16:00, the German flotilla turned around to return to the Jade Estuary, arriving at approximately 20:23.

Bombardment of Yarmouth

On 2 November 1914, , Hipper's flagship , , and , along with four light cruisers, left the Jade Estuary and steamed towards the English coast. The flotilla arrived offGreat Yarmouth

Great Yarmouth (), often called Yarmouth, is a seaside town and unparished area in, and the main administrative centre of, the Borough of Great Yarmouth in Norfolk, England; it straddles the River Yare and is located east of Norwich. A pop ...

at daybreak the following morning and bombarded the port, while the light cruiser laid a minefield. The British submarine responded to the bombardment, but struck one of the mines laid by and sank. Shortly thereafter, Hipper ordered his ships to turn back to German waters. However, while Hipper's ships were returning to German waters, a heavy fog covered the Heligoland Bight, so the ships were ordered to halt until visibility improved so they could safely navigate the defensive minefields. left the Jade without permission, and while en route to Wilhelmshaven made a navigational error that led the ship into one of the German minefields. struck two mines and quickly sank; the coastal defense ship was able to save 127 men of the crew.

Bombardment of Scarborough, Hartlepool, and Whitby

It was decided by Ingenohl that another raid on the English coast was to be carried out, in the hopes of luring a portion of theGrand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from the F ...

into combat, where it could be destroyed. At 03:20 on 15 December, , , , , and , along with the light cruisers , , , and , and two squadrons of torpedo boats left the Jade. The ships sailed north past the island of Heligoland, until they reached the Horns Reef lighthouse, at which point the ships turned west towards Scarborough. Twelve hours after Hipper left the Jade, the High Seas Fleet, consisting of 14 dreadnought

The dreadnought (alternatively spelled dreadnaught) was the predominant type of battleship in the early 20th century. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's , had such an impact when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her ...

s and 8 pre-dreadnought

Pre-dreadnought battleships were sea-going battleships built between the mid- to late- 1880s and 1905, before the launch of in 1906. The pre-dreadnought ships replaced the ironclad battleships of the 1870s and 1880s. Built from steel, protec ...

s and a screening force of 2 armored cruisers, 7 light cruisers, and 54 torpedo boats, departed to provide distant cover.

On 26 August 1914, the German light cruiser had run aground in the Gulf of Finland

The Gulf of Finland ( fi, Suomenlahti; et, Soome laht; rus, Фи́нский зали́в, r=Finskiy zaliv, p=ˈfʲinskʲɪj zɐˈlʲif; sv, Finska viken) is the easternmost arm of the Baltic Sea. It extends between Finland to the north and ...

; the wreck was captured by the Russian navy, which found codebooks used by the German navy, along with navigational charts for the North Sea. These documents were then passed on to the Royal Navy. Room 40 began decrypting German signals, and on 14 December, intercepted messages relating to the plan to bombard Scarborough. However, the exact details of the plan were unknown, and it was assumed that the High Seas Fleet would remain safely in port, as in the previous bombardment. Beatty's four battlecruisers, supported by the 3rd Cruiser Squadron and the 1st Light Cruiser Squadron

The 1st Light Cruiser Squadron was a naval unit of the Royal Navy from 1913 to 1924.

History

The 1st Light Cruiser Squadron was a Royal Navy unit of the Grand Fleet during World War I. Four of its ships ('' Inconstant'', '' Galatea'', '' Cordeli ...

, along with the 2nd Battle Squadron

The 2nd Battle Squadron was a naval squadron of the British Royal Navy consisting of battleships. The 2nd Battle Squadron was initially part of the Royal Navy's Grand Fleet. After World War I the Grand Fleet was reverted to its original name, ...

's six dreadnoughts, were to ambush Hipper's battlecruisers.

2nd Light Cruiser Squadron

The 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron was a naval formation of light cruisers of the Royal Navy from 1914 to 1925.

History World War One

Originally part of the Grand Fleet, the squadron fought at the Battle of Jutland, where it was commanded by William ...

spotted and signaled a report to Beatty. At 12:30, Beatty turned his battlecruisers towards the German ships. Beatty presumed that the German cruisers were the advance screen for Hipper's ships, however those were some ahead. The 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron, which had been screening for Beatty's ships, detached to pursue the German cruisers, but a misinterpreted signal from the British battlecruisers sent them back to their screening positions. This confusion allowed the German light cruisers to escape and alerted Hipper to the location of the British battlecruisers. The German battlecruisers wheeled to the northeast of the British forces and made good their escape.

Both the British and the Germans were disappointed that they failed to effectively engage their opponents. Ingenohl's reputation suffered greatly as a result of his timidity. The captain of was furious; he stated that Ingenohl had turned back "because he was afraid of eleven British destroyers which could have been eliminated ... under the present leadership we will accomplish nothing." The official German history criticized Ingenohl for failing to use his light forces to determine the size of the British fleet, stating: "he decided on a measure which not only seriously jeopardized his advance forces off the English coast but also deprived the German Fleet of a signal and certain victory."

Battle of Dogger Bank

In early January 1915, it became known that British ships were conducting reconnaissance in theDogger Bank

Dogger Bank ( Dutch: ''Doggersbank'', German: ''Doggerbank'', Danish: ''Doggerbanke'') is a large sandbank in a shallow area of the North Sea about off the east coast of England.

During the last ice age the bank was part of a large landmass ...

area. Ingenohl was initially reluctant to destroy these forces, because I Scouting Group was temporarily weakened while was in drydock for periodic maintenance. However, ''KAdm'' Richard Eckermann, the Chief of Staff of the High Seas Fleet, insisted on the operation, and so Ingenohl relented and ordered Hipper to take his battlecruisers to the Dogger Bank.

On 23 January, Hipper sortied, with his flag in , followed by , , and , along with the light cruisers , , , and and 19 torpedo boats from V Flotilla and II and XVIII Half-Flotillas. and were assigned to the forward screen, while and were assigned to the starboard and port, respectively. Each light cruiser had a half-flotilla of torpedo boats attached.

Again, interception and decryption of German wireless signals played an important role. Although they were unaware of the exact plans, the cryptographers of Room 40 were able to deduce that Hipper would be conducting an operation in the Dogger Bank area. To counter it, Beatty's 1st Battlecruiser Squadron

The First Battlecruiser Squadron was a Royal Navy squadron of battlecruisers that saw service as part of the Grand Fleet during the First World War. It was created in 1909 as the First Cruiser Squadron and was renamed in 1913 to First Battle Cr ...

, Rear Admiral Archibald Moore's 2nd Battlecruiser Squadron and Commodore William Goodenough

Admiral Sir William Edmund Goodenough (2 June 1867 – 30 January 1945) was a senior Royal Navy officer of World War I. He was the son of James Graham Goodenough.

Naval career

Goodenough joined the Royal Navy in 1882. He was appointed Command ...

's 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron were to rendezvous with Commodore Reginald Tyrwhitt

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Reginald Yorke Tyrwhitt, 1st Baronet, (; 10 May 1870 – 30 May 1951) was a Royal Navy officer. During the First World War he served as commander of the Harwich Force. He led a supporting naval force of 31 destroyers a ...

's Harwich Force at 08:00 on 24 January, approximately north of the Dogger Bank.

At 08:14, spotted the light cruiser and several destroyers from the Harwich Force. ''Aurora'' challenged with a searchlight, at which point attacked ''Aurora'' and scored two hits. ''Aurora'' returned fire and scored two hits on in retaliation. Hipper immediately turned his battlecruisers towards the gunfire, when, almost simultaneously, spotted a large amount of smoke to the northwest of her position. This was identified as a number of large British warships steaming towards Hipper's ships.

Hipper turned south to flee, but was limited to , which was the maximum speed of the older armored cruiser . The pursuing British battlecruisers were steaming at , and quickly caught up to the German ships. At 09:52, opened fire on from a range of approximately 20,000 yards (18,300 m); shortly thereafter, and began firing as well. At 10:09, the British guns made their first hit on . Two minutes later, the German ships began returning fire, primarily concentrating on ''Lion'', from a range of 18,000 yards (15,460 m). At 10:28, ''Lion'' was struck on the waterline, which tore a hole in the side of the ship and flooded a coal bunker. At 10:30, , the fourth ship in Beatty's line, came within range of and opened fire. By 10:35, the range had closed to 17,500 yards (16,000 m), at which point the entire German line was within the effective range of the British ships. Beatty ordered his battlecruisers to engage their German counterparts. However, confusion aboard ''Tiger'' led the captain to believe he was to fire on , which left able to fire without distraction.

At 10:40, one of ''Lion''s shells struck causing nearly catastrophic damage that knocked out both of the rear turrets and killed 159 men. Disaster was averted when the executive officer ordered the flooding of both magazines to avoid a flash fire that would have destroyed the ship. By this time, the German battlecruisers had zeroed in on ''Lion'' and began scoring repeated hits. At 11:01, an shell from struck ''Lion'' and knocked out two of her dynamos. At 11:18, ''Lion'' was hit by two shells from , one of which struck the waterline and penetrated the belt, allowing seawater to enter the port feed tank. This shell eventually crippled ''Lion'' by forcing the ship to turn off its engines because of seawater contamination.

By this time, was severely damaged after having been pounded by heavy shells. However, the chase ended when there were several reports of U-boats ahead of the British ships; Beatty quickly ordered evasive maneuvers, which allowed the German ships to increase the distance from their pursuers. At this time, ''Lion''s last operational dynamo failed, which dropped her speed to 15 knots. Beatty, in the stricken ''Lion'', ordered the remaining battlecruisers to "Engage the enemy's rear," but signal confusion caused the ships to solely target , allowing , , and to escape. By the time Beatty regained control over his ships, after having boarded ''Princess Royal'', the German ships had too far a lead for the British to catch them; at 13:50, he broke off the chase.

Battle of the Gulf of Riga

On 3 August 1915, was transferred to the Baltic with I Reconnaissance Group (AG) to participate in the foray into theRiga Gulf

The Gulf of Riga, Bay of Riga, or Gulf of Livonia ( lv, Rīgas līcis, et, Liivi laht) is a bay of the Baltic Sea between Latvia and Estonia.

The island of Saaremaa (Estonia) partially separates it from the rest of the Baltic Sea. The main con ...

. The intention was to destroy the Russian naval forces in the area, including the pre-dreadnought , and to use the minelayer to block the entrance to Moon Sound with naval mines. The German forces, under the command of now ''VAdm'' Hipper, included the four and four s, the battlecruisers , , and , and a number of smaller craft.

On 8 August, the first attempt to clear the gulf was made; the old battleships and kept at bay while minesweepers cleared a path through the inner belt of mines. During this period, the rest of the German fleet remained in the Baltic and provided protection against other units of the Russian fleet. However, the approach of nightfall meant that would be unable to mine the entrance to Moon Sound in time, and so the operation was broken off.

On 16 August, a second attempt was made to enter the gulf. The dreadnoughts and , four light cruisers, and 31 torpedo boats breached the defenses to the gulf. and engaged in an artillery duel with , resulting in three hits on the Russian ship that prompted her withdrawal. After three days, the Russian minefields had been cleared, and the flotilla entered the gulf on 19 August, but reports of Allied submarines in the area prompted a German withdrawal from the gulf the following day.

Throughout the operation, remained in the Baltic and provided cover for the assault into the Gulf of Riga. On the morning of the 19th, was torpedoed by the British E-class submarine . The torpedo was not spotted until it was approximately 200 yards (183 m) away; without time to maneuver, the ship was struck in the bow torpedo room. The explosion damaged several torpedoes in the ship, but they did not detonate themselves. Eight men were killed, and of water entered the ship. The ship was repaired at Blohm & Voss in Hamburg, between 23 August and 20 September. In January 1916, ''KzS'' Johannes von Karpf relieved Levetzow as the ship's commander.

Bombardment of Yarmouth and Lowestoft

also took part in the bombardment of Yarmouth and Lowestoft on 24–25 April. Hipper was away on sick leave, so the German ships were under the command of ''KAdm'' Friedrich Boedicker. The German battlecruisers , , , and left the Jade Estuary at 10:55 on 24 April, and were supported by a screening force of six light cruisers and two torpedo boat flotillas. The heavy units of the High Seas Fleet sailed at 13:40, with the objective to provide distant support for Boedicker's ships. The British Admiralty was made aware of the German sortie through the interception of German

also took part in the bombardment of Yarmouth and Lowestoft on 24–25 April. Hipper was away on sick leave, so the German ships were under the command of ''KAdm'' Friedrich Boedicker. The German battlecruisers , , , and left the Jade Estuary at 10:55 on 24 April, and were supported by a screening force of six light cruisers and two torpedo boat flotillas. The heavy units of the High Seas Fleet sailed at 13:40, with the objective to provide distant support for Boedicker's ships. The British Admiralty was made aware of the German sortie through the interception of German wireless

Wireless communication (or just wireless, when the context allows) is the transfer of information between two or more points without the use of an electrical conductor, optical fiber or other continuous guided medium for the transfer. The most ...

signals, and deployed the Grand Fleet at 15:50.

By 14:00, Boedicker's ships had reached a position off Norderney

Norderney ( nds, Nördernee) is one of the seven populated East Frisian Islands off the North Sea coast of Germany.

The island is , having a total area of about and is therefore Germany's ninth-largest island. Norderney's population amounts ...

, at which point he turned his ships northward to avoid the Dutch observers on the island of Terschelling

Terschelling (; fry, Skylge; Terschelling dialect: ''Schylge'') is a municipality and an island in the northern Netherlands, one of the West Frisian Islands. It is situated between the islands of Vlieland and Ameland.

Wadden Islanders are k ...

. At 15:38, struck a naval mine

A naval mine is a self-contained explosive device placed in water to damage or destroy surface ships or submarines. Unlike depth charges, mines are deposited and left to wait until they are triggered by the approach of, or contact with, an ...

, which tore a 50-foot (15 m) hole in her hull, just abaft of the starboard broadside torpedo tube, allowing 1,400 short tons (1,250 long tons) of water to enter the ship. turned back, with the screen of light cruisers, at a speed of . The four remaining battlecruisers turned south immediately in the direction of Norderney to avoid further mine damage. By 16:00, was clear of imminent danger, so the ship stopped to allow Boedicker to disembark. The torpedo boat brought Boedicker to .

At 04:50 on 25 April, the German battlecruisers were approaching Lowestoft when the light cruisers and , which had been covering the southern flank, spotted the light cruisers and destroyers of Commodore Tyrwhitt's Harwich Force. Boedicker refused to be distracted by the British ships, and instead trained his ships' guns on Lowestoft. The German battlecruisers destroyed two 6 in (15 cm) shore batteries and inflicted other damage to the town. In the process, a single 6 in shell from one of the shore batteries struck , but the ship sustained no significant damage.

At 05:20, the German raiders turned north, towards Yarmouth, which they reached by 05:42. The visibility was so poor that the German ships fired one salvo

A salvo is the simultaneous discharge of artillery or firearms including the firing of guns either to hit a target or to perform a salute. As a tactic in warfare, the intent is to cripple an enemy in one blow and prevent them from fightin ...

each, with the exception of , which fired fourteen rounds from her main battery. The German ships turned back south, and at 05:47 encountered for the second time the Harwich Force, which had by then been engaged by the six light cruisers of the screening force. Boedicker's ships opened fire from a range of 13,000 yards (12,000 m). Tyrwhitt immediately turned his ships around and fled south, but not before the cruiser sustained severe damage. Due to reports of British submarines and torpedo attacks, Boedicker broke off the chase and turned back east towards the High Seas Fleet. At this point, Scheer, who had been warned of the Grand Fleet's sortie from Scapa Flow, turned back towards Germany.

Battle of Jutland

=Run to the south

= Shortly before 16:00, Hipper's force encountered Beatty's battlecruiser squadron. The German ships were the first to open fire, at a range of approximately 15,000 yards (14,000 m). When the British ships began returning fire, confusion amongst the British battlecruisers resulted in being engaged by both ''New Zealand'' and ''Tiger''. The British rangefinders had misread the range to their German targets, and so the first salvos fired by the British ships fell a mile past the German battlecruisers. At 16:52, hit ''Tiger'' with two main gun shells, but neither of these hits caused any significant damage. then fired a further four shells, two of which hit simultaneously on the midships and after turrets, knocking both out for a significant period of the battle.

Approximately 15 minutes later, the British battlecruiser was suddenly destroyed by . Shortly thereafter, fired four torpedoes at ''Queen Mary'' at a range between . This caused the British line to fall into disarray, as the torpedoes were thought to have been fired by U-boats. At this point, Hipper's battlecruisers had come into range of the V Battle Squadron, composed of the new s, which mounted powerful guns. At 17:06, opened fire on . She was joined a few minutes later by , ''Malaya'', and ; the ships concentrated their fire on and . At 17:16, one of the 15 in shells from the fast battleships struck , where it pierced a coal bunker, tore into a casemate deck, and ignited ammunition stored therein. The explosion burned the ammunition hoist down to the magazine.

and changed their speed and direction, which threw off the aim of the V Battle Squadron and earned the battered ships a short respite. While and were drawing the fire of the V Battle Squadron battleships, and were able to concentrate their fire on the British battlecruisers; between 17:25 and 17:30, at least five shells from and struck ''Queen Mary'', causing a catastrophic explosion that destroyed the ship. s commander, von Karpf, remarked that "The enemy's salvos lie well and close; their salvos are fired in rapid succession, the fire discipline is excellent!"

Shortly before 16:00, Hipper's force encountered Beatty's battlecruiser squadron. The German ships were the first to open fire, at a range of approximately 15,000 yards (14,000 m). When the British ships began returning fire, confusion amongst the British battlecruisers resulted in being engaged by both ''New Zealand'' and ''Tiger''. The British rangefinders had misread the range to their German targets, and so the first salvos fired by the British ships fell a mile past the German battlecruisers. At 16:52, hit ''Tiger'' with two main gun shells, but neither of these hits caused any significant damage. then fired a further four shells, two of which hit simultaneously on the midships and after turrets, knocking both out for a significant period of the battle.

Approximately 15 minutes later, the British battlecruiser was suddenly destroyed by . Shortly thereafter, fired four torpedoes at ''Queen Mary'' at a range between . This caused the British line to fall into disarray, as the torpedoes were thought to have been fired by U-boats. At this point, Hipper's battlecruisers had come into range of the V Battle Squadron, composed of the new s, which mounted powerful guns. At 17:06, opened fire on . She was joined a few minutes later by , ''Malaya'', and ; the ships concentrated their fire on and . At 17:16, one of the 15 in shells from the fast battleships struck , where it pierced a coal bunker, tore into a casemate deck, and ignited ammunition stored therein. The explosion burned the ammunition hoist down to the magazine.

and changed their speed and direction, which threw off the aim of the V Battle Squadron and earned the battered ships a short respite. While and were drawing the fire of the V Battle Squadron battleships, and were able to concentrate their fire on the British battlecruisers; between 17:25 and 17:30, at least five shells from and struck ''Queen Mary'', causing a catastrophic explosion that destroyed the ship. s commander, von Karpf, remarked that "The enemy's salvos lie well and close; their salvos are fired in rapid succession, the fire discipline is excellent!"

=Battlefleets engage

= By 19:30, the High Seas Fleet, which was by that point pursuing the British battlecruisers, had not yet encountered the Grand Fleet. Scheer had been considering retiring his forces before darkness exposed his ships to torpedo boat attack. However, he had not yet made a decision when his leading battleships encountered the main body of the Grand Fleet. This development made it impossible for Scheer to retreat, for doing so would have sacrificed the slower pre-dreadnought battleships of II Battle Squadron, while using his dreadnoughts and battlecruisers to cover their retreat would have subjected his strongest ships to overwhelming British fire. Instead, Scheer ordered his ships to turn 16 points to starboard, which would bring the pre-dreadnoughts to the relative safety of the disengaged side of the German battle line. and the other battlecruisers followed the move, which put them astern of . Hipper's badly battered ships gained a temporary moment of respite, and uncertainty over the exact location and course of Scheer's ships led AdmiralJohn Jellicoe

Admiral of the Fleet John Rushworth Jellicoe, 1st Earl Jellicoe, (5 December 1859 – 20 November 1935) was a Royal Navy officer. He fought in the Anglo-Egyptian War and the Boxer Rebellion and commanded the Grand Fleet at the Battle of Jutlan ...

to turn his ships eastward, towards what he thought was the likely path of the German retreat. The German fleet was instead sailing west, but Scheer ordered a second 16-point turn, which reversed course and pointed his ships at the center of the British fleet. The German fleet came under intense fire from the British line, and Scheer sent , , , and at high speed towards the British fleet, in an attempt to disrupt their formation and gain time for his main force to retreat. By 20:17, the German battlecruisers had closed to within 7,700 yards (7,040 m) of , at which point Scheer directed the ships to engage the lead ship of the British line. However, three minutes later, the German battlecruisers turned in retreat, covered by a torpedo boat attack.

=Withdrawal

= A pause in the battle at dusk allowed and the other German battlecruisers to cut away wreckage that interfered with the main guns, extinguish fires, repair the fire control and signal equipment, and ready the searchlights for nighttime action. During this period, the German fleet reorganized into a well-ordered formation in reverse order, when the German light forces encountered the British screen shortly after 21:00. The renewed gunfire gained Beatty's attention, so he turned his battlecruisers westward. At 21:09, he sighted the German battlecruisers, and drew to within before opening fire at 20:20. The attack from the British battlecruisers completely surprised Hipper, who had been in the process of boarding from the torpedo boat . The German ships returned fire with every gun available, and at 21:32 hit both ''Lion'' and ''Princess Royal'' in the darkness. The maneuvering of the German battlecruisers forced the leading I Battle Squadron to turn westward to avoid collision. This brought the pre-dreadnoughts of II Battle Squadron directly behind the battlecruisers, and prevented the British ships from pursuing the German battlecruisers when they turned southward. The British battlecruisers opened fire on the old battleships; the German ships turned southwest to bring all of their guns to bear against the British ships.

By 22:15, Hipper was finally able to transfer to , and then ordered his ships to steam at towards the head of the German line. However, only and were in condition to comply; and could make at most 18 knots, and so these ships lagged behind. and were in the process of steaming to the front of the line when the ships passed close to , which forced the ship to drastically slow down to avoid collision. This forced , , and to turn to port, which led them into contact with the 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron; at a range of , the cruisers on both sides pummeled each other. ''KADm''

A pause in the battle at dusk allowed and the other German battlecruisers to cut away wreckage that interfered with the main guns, extinguish fires, repair the fire control and signal equipment, and ready the searchlights for nighttime action. During this period, the German fleet reorganized into a well-ordered formation in reverse order, when the German light forces encountered the British screen shortly after 21:00. The renewed gunfire gained Beatty's attention, so he turned his battlecruisers westward. At 21:09, he sighted the German battlecruisers, and drew to within before opening fire at 20:20. The attack from the British battlecruisers completely surprised Hipper, who had been in the process of boarding from the torpedo boat . The German ships returned fire with every gun available, and at 21:32 hit both ''Lion'' and ''Princess Royal'' in the darkness. The maneuvering of the German battlecruisers forced the leading I Battle Squadron to turn westward to avoid collision. This brought the pre-dreadnoughts of II Battle Squadron directly behind the battlecruisers, and prevented the British ships from pursuing the German battlecruisers when they turned southward. The British battlecruisers opened fire on the old battleships; the German ships turned southwest to bring all of their guns to bear against the British ships.

By 22:15, Hipper was finally able to transfer to , and then ordered his ships to steam at towards the head of the German line. However, only and were in condition to comply; and could make at most 18 knots, and so these ships lagged behind. and were in the process of steaming to the front of the line when the ships passed close to , which forced the ship to drastically slow down to avoid collision. This forced , , and to turn to port, which led them into contact with the 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron; at a range of , the cruisers on both sides pummeled each other. ''KADm'' Ludwig von Reuter

Hans Hermann Ludwig von Reuter (9 February 1869 – 18 December 1943) was a German admiral who commanded the High Seas Fleet when it was interned at Scapa Flow in the north of Scotland at the end of World War I. On 21 June 1919 he ordered t ...

decided to attempt to lure the British cruisers towards and . However, nearly simultaneously, the heavily damaged British cruisers broke off the attack. As the light cruisers were disengaging, a torpedo fired by struck , and the ship exploded. The German formation fell into disarray, and in the confusion, lost sight of . was no longer able to keep up with s , and so detached herself to proceed to the Horns Reef lighthouse independently.

By 23:30 on her own, encountered four British dreadnoughts, from the rear division of the 2nd Battle Squadron. Karpf ordered the ship to swing away, hoping he had not been detected. The British ships in fact had seen , but had decided to not open fire in order to not reveal their location to the entire German fleet. At 23:55, and again at 00:20, Karpf tried to find a path through the British fleet, but both times was unable to do so. It was not until 01:00, after having steamed far ahead of the Grand Fleet, that was able to make good her escape.