SMS Derfflinger on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

SMS was a

was

was

Built by

Built by

During the night of 15 December, the main body of the High Seas Fleet encountered British destroyers. Fearing a nighttime torpedo attack, Admiral Ingenohl ordered the ships to retreat. Hipper was unaware of Ingenohl's reversal, and so he continued with the bombardment. Upon reaching the British coast, Hipper's battlecruisers split into two groups. and went south to shell Scarborough and Whitby while , , and went north to shell Hartlepool. By 09:45 on the 16th, the two groups had reassembled, and they began to retreat eastward.

By this time, Beatty's battlecruisers were positioned to block Hipper's chosen withdrawal route, while other forces were en route to complete the encirclement. At 12:25, the light cruisers of II Scouting Group began to pass through the British forces searching for Hipper. One of the cruisers in the 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron spotted and signaled a report to Beatty. At 12:30, Beatty turned his battlecruisers towards the German ships. Beatty presumed the German cruisers were the advance screen for Hipper's ships; however, those were some 50 km (31 mi) ahead. The 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron, which had been screening for Beatty's ships, detached to pursue the German cruisers, but a misinterpreted signal from the British battlecruisers sent them back to their screening positions. This confusion allowed the German light cruisers to slip away and alerted Hipper to the location of the British battlecruisers. The German battlecruisers wheeled to the northeast of the British forces and escaped.

Both the British and the Germans were disappointed that they failed to effectively engage their opponents. Admiral Ingenohl's reputation suffered greatly as a result of his timidity. s captain was furious; he said Ingenohl had turned back "because he was afraid of 11 British destroyers which could have been eliminated... under the present leadership we will accomplish nothing." The official German history criticized Ingenohl for failing to use his light forces to determine the size of the British fleet, stating: "he decided on a measure which not only seriously jeopardized his advance forces off the English coast but also deprived the German Fleet of a signal and certain victory."

During the night of 15 December, the main body of the High Seas Fleet encountered British destroyers. Fearing a nighttime torpedo attack, Admiral Ingenohl ordered the ships to retreat. Hipper was unaware of Ingenohl's reversal, and so he continued with the bombardment. Upon reaching the British coast, Hipper's battlecruisers split into two groups. and went south to shell Scarborough and Whitby while , , and went north to shell Hartlepool. By 09:45 on the 16th, the two groups had reassembled, and they began to retreat eastward.

By this time, Beatty's battlecruisers were positioned to block Hipper's chosen withdrawal route, while other forces were en route to complete the encirclement. At 12:25, the light cruisers of II Scouting Group began to pass through the British forces searching for Hipper. One of the cruisers in the 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron spotted and signaled a report to Beatty. At 12:30, Beatty turned his battlecruisers towards the German ships. Beatty presumed the German cruisers were the advance screen for Hipper's ships; however, those were some 50 km (31 mi) ahead. The 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron, which had been screening for Beatty's ships, detached to pursue the German cruisers, but a misinterpreted signal from the British battlecruisers sent them back to their screening positions. This confusion allowed the German light cruisers to slip away and alerted Hipper to the location of the British battlecruisers. The German battlecruisers wheeled to the northeast of the British forces and escaped.

Both the British and the Germans were disappointed that they failed to effectively engage their opponents. Admiral Ingenohl's reputation suffered greatly as a result of his timidity. s captain was furious; he said Ingenohl had turned back "because he was afraid of 11 British destroyers which could have been eliminated... under the present leadership we will accomplish nothing." The official German history criticized Ingenohl for failing to use his light forces to determine the size of the British fleet, stating: "he decided on a measure which not only seriously jeopardized his advance forces off the English coast but also deprived the German Fleet of a signal and certain victory."

Hipper turned south to flee, but was limited to , which was the maximum speed of the older armored cruiser . The pursuing British battlecruisers were steaming at , and quickly caught up to the German ships. At 09:52, the battlecruiser opened fire on from a range of approximately ; shortly thereafter, and began firing as well. At 10:09, the British guns made their first hit on . Two minutes later, the German ships began returning fire, primarily concentrating on ''Lion'', from a range of . At 10:28, ''Lion'' was struck on the waterline, which tore a hole in the side of the ship and flooded a coal bunker. At 10:30, , the fourth ship in Beatty's line, came within range of and opened fire. By 10:35, the range had closed to , at which point the entire German line was within the effective range of the British ships. Beatty ordered his battlecruisers to engage their German counterparts. Confusion aboard ''Tiger'' led the captain to believe he was to fire on , which left able to fire without distraction. During this period of the battle, was hit once, but the shell did only minor damage. Two armor plates in the hull were forced inward and some of the protective coal bunkers were flooded.

At 10:40, one of ''Lion''s shells struck causing nearly catastrophic damage that knocked out both rear turrets and killed 159 men. The executive officer ordered both magazines flooded to avoid a flash fire that would have destroyed the ship. By this time, the German battlecruisers had zeroed in on ''Lion'', scoring repeated hits. At 11:01, an shell from struck ''Lion'' and knocked out two of her dynamos. At 11:18, two of shells hit ''Lion'', one of which struck the waterline and penetrated the belt, allowing seawater to enter the port feed tank. ''Lion'' had to turn off its engines due to seawater contamination and as a result fell out of the line.

By this time, was severely damaged after having been pounded by heavy shells. The chase ended when there were several reports of U-boats ahead of the British ships; Beatty quickly ordered evasive maneuvers, which allowed the German ships to increase the distance to their pursuers. At this time, ''Lion''s last operational dynamo failed, which dropped her speed to . Beatty, in the stricken ''Lion'', ordered the remaining battlecruisers to "engage the enemy's rear," but signal confusion caused the ships to solely target , allowing , , and to escape. was hit by more than 70 shells from the British battlecruisers over the course of the battle. The severely damaged warship capsized and sank at approximately 13:10. By the time Beatty regained control over his ships, after having boarded ''Princess Royal'', the German ships had too great a lead for the British to catch them; at 13:50, he broke off the chase.

Hipper turned south to flee, but was limited to , which was the maximum speed of the older armored cruiser . The pursuing British battlecruisers were steaming at , and quickly caught up to the German ships. At 09:52, the battlecruiser opened fire on from a range of approximately ; shortly thereafter, and began firing as well. At 10:09, the British guns made their first hit on . Two minutes later, the German ships began returning fire, primarily concentrating on ''Lion'', from a range of . At 10:28, ''Lion'' was struck on the waterline, which tore a hole in the side of the ship and flooded a coal bunker. At 10:30, , the fourth ship in Beatty's line, came within range of and opened fire. By 10:35, the range had closed to , at which point the entire German line was within the effective range of the British ships. Beatty ordered his battlecruisers to engage their German counterparts. Confusion aboard ''Tiger'' led the captain to believe he was to fire on , which left able to fire without distraction. During this period of the battle, was hit once, but the shell did only minor damage. Two armor plates in the hull were forced inward and some of the protective coal bunkers were flooded.

At 10:40, one of ''Lion''s shells struck causing nearly catastrophic damage that knocked out both rear turrets and killed 159 men. The executive officer ordered both magazines flooded to avoid a flash fire that would have destroyed the ship. By this time, the German battlecruisers had zeroed in on ''Lion'', scoring repeated hits. At 11:01, an shell from struck ''Lion'' and knocked out two of her dynamos. At 11:18, two of shells hit ''Lion'', one of which struck the waterline and penetrated the belt, allowing seawater to enter the port feed tank. ''Lion'' had to turn off its engines due to seawater contamination and as a result fell out of the line.

By this time, was severely damaged after having been pounded by heavy shells. The chase ended when there were several reports of U-boats ahead of the British ships; Beatty quickly ordered evasive maneuvers, which allowed the German ships to increase the distance to their pursuers. At this time, ''Lion''s last operational dynamo failed, which dropped her speed to . Beatty, in the stricken ''Lion'', ordered the remaining battlecruisers to "engage the enemy's rear," but signal confusion caused the ships to solely target , allowing , , and to escape. was hit by more than 70 shells from the British battlecruisers over the course of the battle. The severely damaged warship capsized and sank at approximately 13:10. By the time Beatty regained control over his ships, after having boarded ''Princess Royal'', the German ships had too great a lead for the British to catch them; at 13:50, he broke off the chase.

also took part in the bombardment of Yarmouth and Lowestoft on 24–25 April 1916. Hipper was away on sick leave, so the German ships were under the command of Konteradmiral

also took part in the bombardment of Yarmouth and Lowestoft on 24–25 April 1916. Hipper was away on sick leave, so the German ships were under the command of Konteradmiral

Almost immediately after the Lowestoft raid, Scheer began planning another foray into the North Sea. He had initially intended to launch the operation in mid-May, but the mine damage to had proved difficult to repair, and Scheer was unwilling to embark on a major raid without his battlecruiser forces at full strength. At noon on 28 May, the repairs to were finally completed, and the ship returned to I Scouting Group.

and the rest of Hipper's I Scouting Group battlecruisers lay anchored in the outer Jade

Almost immediately after the Lowestoft raid, Scheer began planning another foray into the North Sea. He had initially intended to launch the operation in mid-May, but the mine damage to had proved difficult to repair, and Scheer was unwilling to embark on a major raid without his battlecruiser forces at full strength. At noon on 28 May, the repairs to were finally completed, and the ship returned to I Scouting Group.

and the rest of Hipper's I Scouting Group battlecruisers lay anchored in the outer Jade

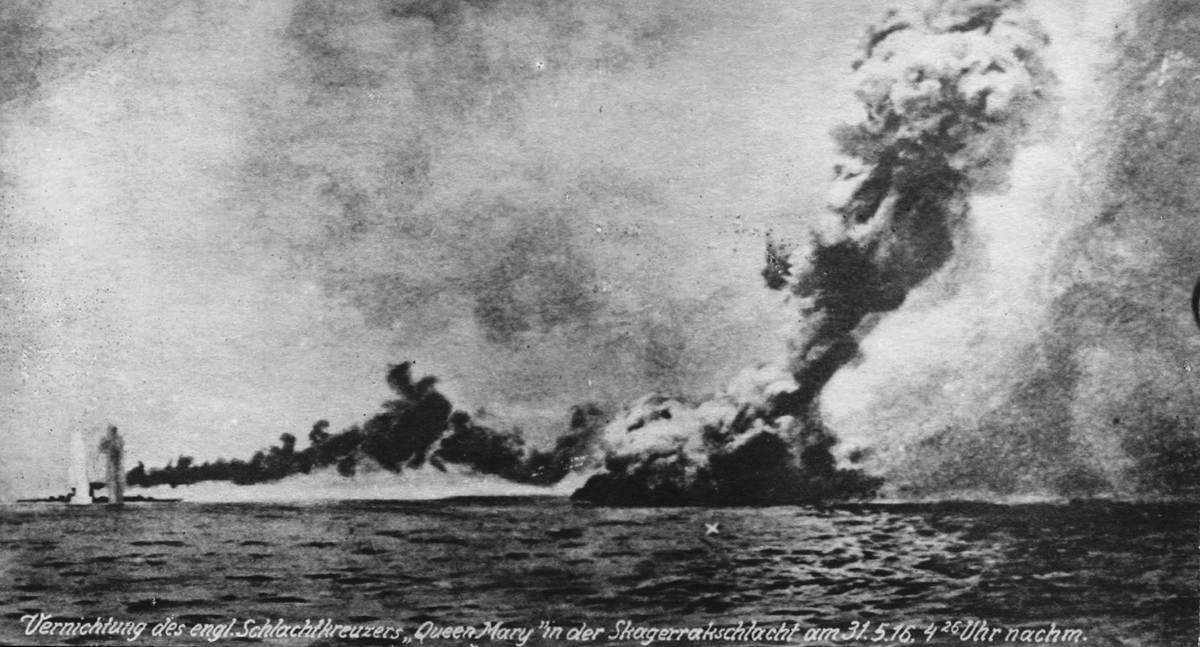

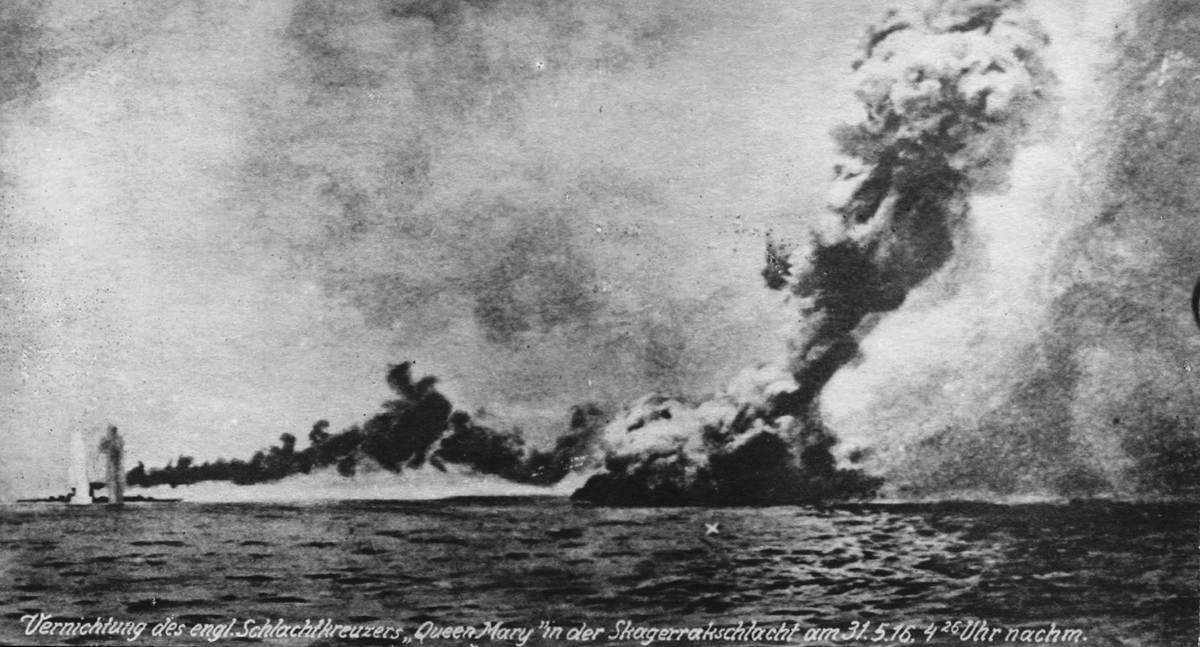

Shortly before 16:00, Hipper's force encountered the six ships of Vice Admiral Beatty's 1st and 2nd Battlecruiser Squadrons. The German ships were the first to open fire, at a range of approximately . When the British ships began returning fire, confusion among the British battlecruisers resulted in being engaged by both ''New Zealand'' and ''Tiger''. The British rangefinders had misread the range to their German targets, and so the first salvos fired by the British ships fell a mile past the German battlecruisers. Due to errors in British communication, was not engaged during the first ten minutes of the battle. s gunnery officer, Georg von Hase later remarked "By some mistake we were being left out. I laughed grimly and now I began to engage our enemy with complete calm, as at gun practice, and with continually increasing accuracy." At 17:03, the British battlecruiser exploded after fifteen minutes of gunfire from . Shortly thereafter the second half of Beatty's force, the four s of the

Shortly before 16:00, Hipper's force encountered the six ships of Vice Admiral Beatty's 1st and 2nd Battlecruiser Squadrons. The German ships were the first to open fire, at a range of approximately . When the British ships began returning fire, confusion among the British battlecruisers resulted in being engaged by both ''New Zealand'' and ''Tiger''. The British rangefinders had misread the range to their German targets, and so the first salvos fired by the British ships fell a mile past the German battlecruisers. Due to errors in British communication, was not engaged during the first ten minutes of the battle. s gunnery officer, Georg von Hase later remarked "By some mistake we were being left out. I laughed grimly and now I began to engage our enemy with complete calm, as at gun practice, and with continually increasing accuracy." At 17:03, the British battlecruiser exploded after fifteen minutes of gunfire from . Shortly thereafter the second half of Beatty's force, the four s of the

Following Germany's capitulation, the Allies demanded that the majority of the High Seas Fleet be interned in the British naval base at

Following Germany's capitulation, the Allies demanded that the majority of the High Seas Fleet be interned in the British naval base at

battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of attr ...

of the German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

(Imperial Navy) built in the early 1910s during the Anglo-German naval arms race

The arms race between Great Britain and Germany that occurred from the last decade of the nineteenth century until the advent of World War I in 1914 was one of the intertwined causes of that conflict. While based in a bilateral relationship that ...

. She was the lead ship

The lead ship, name ship, or class leader is the first of a series or class of ships all constructed according to the same general design. The term is applicable to naval ships and large civilian vessels.

Large ships are very complex and may ...

of her class

Class or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used differentl ...

of three ships; her sister ship

A sister ship is a ship of the same class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They often share a ...

s were and . The s were larger and featured significant improvements over the previous German battlecruisers, carrying larger guns in a more efficient superfiring

Superfiring armament is a naval military building technique in which two (or more) turrets are located in a line, one behind the other, with the second turret located above ("super") the one in front so that the second turret can fire over the ...

arrangement. was armed with a main battery

A main battery is the primary weapon or group of weapons around which a warship is designed. As such, a main battery was historically a gun or group of guns, as in the broadsides of cannon on a ship of the line. Later, this came to be turreted ...

of eight guns, compared to the guns of earlier battlecruisers. She had a top speed of and carried heavy protection, including a thick armored belt

Belt armor is a layer of heavy metal vehicle armor, armor plated onto or within the outer hulls of warships, typically on battleships, battlecruisers and cruisers, and aircraft carriers.

The belt armor is designed to prevent projectiles from p ...

.

was completed shortly after the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in 1914; after entering service, she joined the other German battlecruisers in I Scouting Group

The I Scouting Group (german: I. Aufklärungsgruppe) was a special reconnaissance unit within the German Kaiserliche Marine. The unit was famously commanded by Admiral Franz von Hipper during World War I. The I Scouting Group was one of the most ...

of the High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet (''Hochseeflotte'') was the battle fleet of the German Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. The formation was created in February 1907, when the Home Fleet (''Heimatflotte'') was renamed as the High Seas ...

, where she served for the duration of the conflict. As part of this force, she took part in numerous operations in the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

, including the Raid on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby

The Raid on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby on 16 December 1914 was an attack by the Imperial German Navy on the British ports of Scarborough, Hartlepool, West Hartlepool and Whitby. The bombardments caused hundreds of civilian casualties an ...

in December 1914, the Battle of Dogger Bank in January 1915, and the Bombardment of Yarmouth and Lowestoft

The Bombardment of Yarmouth and Lowestoft, often referred to as the Lowestoft Raid, was a naval battle fought during the First World War between the German Empire and the British Empire in the North Sea.

The German fleet sent a battlecruiser ...

in April 1916. These operations culminated in the Battle of Jutland

The Battle of Jutland (german: Skagerrakschlacht, the Battle of the Skagerrak) was a naval battle fought between Britain's Royal Navy Grand Fleet, under Admiral John Jellicoe, 1st Earl Jellicoe, Sir John Jellicoe, and the Imperial German Navy ...

on 31 May – 1 June 1916, where helped to sink the British battlecruisers and . was seriously damaged in the action and was out of service for repairs for several months afterward.

The ship rejoined the fleet in late 1916, though by this time the Germans had abandoned their strategy of raids with the surface fleet in favor of the U-boat campaign

The U-boat Campaign from 1914 to 1918 was the World War I naval campaign fought by German U-boats against the trade routes of the Allies. It took place largely in the seas around the British Isles and in the Mediterranean.

The German Empire r ...

. As a result, and the rest of the High Seas Fleet saw little activity for the last two years of the war apart from patrol duty in the German Bight

The German Bight (german: Deutsche Bucht; da, tyske bugt; nl, Duitse bocht; fry, Dútske bocht; ; sometimes also the German Bay) is the southeastern bight of the North Sea bounded by the Netherlands and Germany to the south, and Denmark and ...

. The fleet conducted one final operation in April 1918 in an unsuccessful attempt to intercept a British convoy to Norway. After the end of the war in November 1918, the fleet was interned in Scapa Flow

Scapa Flow viewed from its eastern end in June 2009

Scapa Flow (; ) is a body of water in the Orkney Islands, Scotland, sheltered by the islands of Mainland, Graemsay, Burray,S. C. George, ''Jutland to Junkyard'', 1973. South Ronaldsay and ...

. On the order of Rear Admiral Ludwig von Reuter

Hans Hermann Ludwig von Reuter (9 February 1869 – 18 December 1943) was a German admiral who commanded the High Seas Fleet when it was interned at Scapa Flow in the north of Scotland at the end of World War I. On 21 June 1919 he ordered ...

, the interned ships were scuttled on 21 June 1919 to prevent them from being seized by the Allied powers.

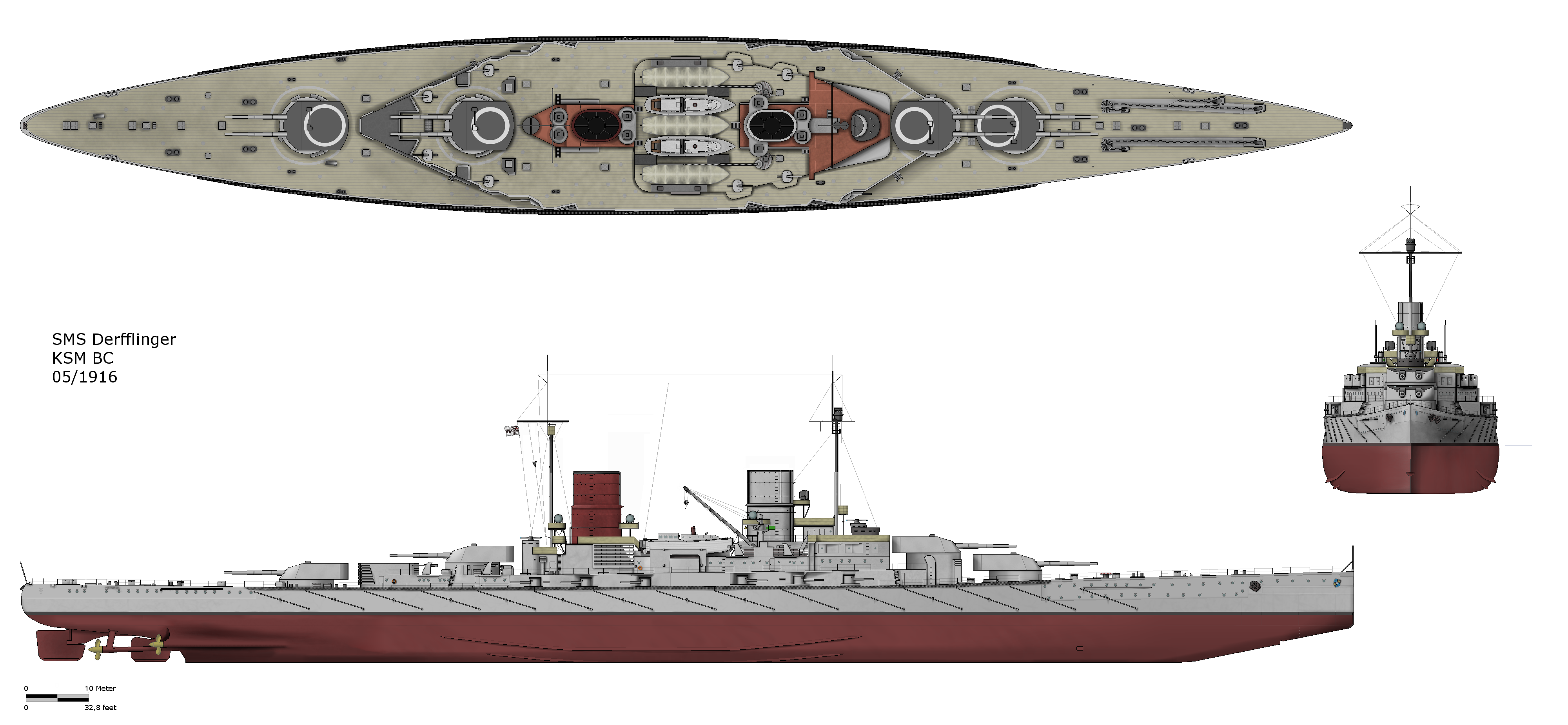

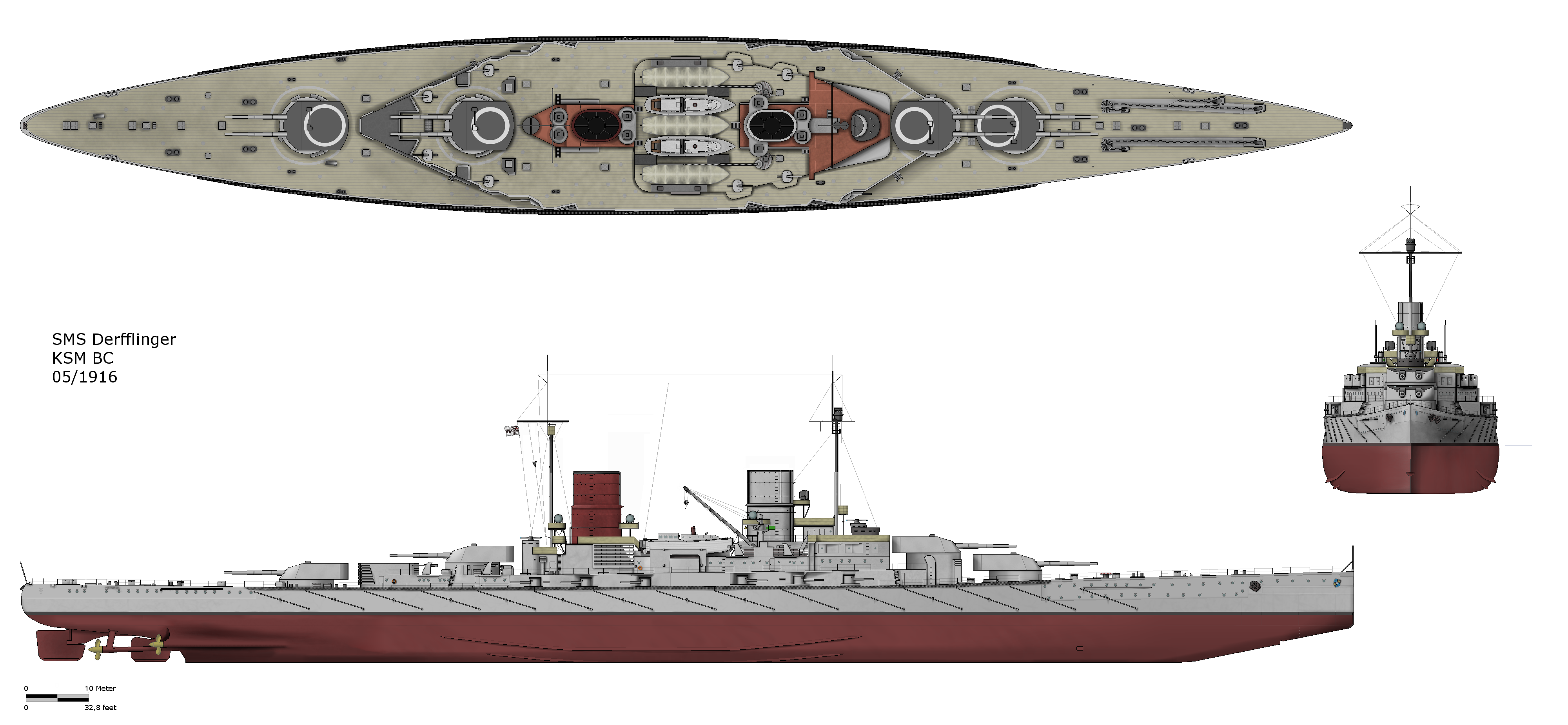

Design

The class was authorized for the 1911 fiscal year as part of the 1906 naval law; design work had begun in early 1910. After their British counterparts had begun installing guns in theirbattlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of attr ...

s, senior officers in the German naval command concluded that an increase in the caliber of the main battery

A main battery is the primary weapon or group of weapons around which a warship is designed. As such, a main battery was historically a gun or group of guns, as in the broadsides of cannon on a ship of the line. Later, this came to be turreted ...

guns from to would be necessary. To keep costs from growing too quickly, the number of guns was reduced from ten to eight, compared to the earlier , but a more efficient superfiring

Superfiring armament is a naval military building technique in which two (or more) turrets are located in a line, one behind the other, with the second turret located above ("super") the one in front so that the second turret can fire over the ...

arrangement was adopted.

Characteristics

was

was long overall

__NOTOC__

Length overall (LOA, o/a, o.a. or oa) is the maximum length of a vessel's hull measured parallel to the waterline. This length is important while docking the ship. It is the most commonly used way of expressing the size of a ship, an ...

, with a beam

Beam may refer to:

Streams of particles or energy

*Light beam, or beam of light, a directional projection of light energy

**Laser beam

*Particle beam, a stream of charged or neutral particles

**Charged particle beam, a spatially localized grou ...

of and a draft

Draft, The Draft, or Draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a vessel ...

of . She displaced normally and up to at full load

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into wei ...

. The ship had a crew of 44 officers and 1,068 enlisted men. In early August 1915, a derrick

A derrick is a lifting device composed at minimum of one guyed mast, as in a gin pole, which may be articulated over a load by adjusting its guys. Most derricks have at least two components, either a guyed mast or self-supporting tower, and a ...

was mounted amidships, and tests with Hansa-Brandenburg W

The Hansa-Brandenburg W was a reconnaissance floatplane produced in Germany in 1914 to equip the Imperial German Navy. Similar in general layout to the Hansa-Brandenburg B.I landplane, the W was a conventional three-bay biplane with unstaggered ...

seaplane

A seaplane is a powered fixed-wing aircraft capable of takeoff, taking off and water landing, landing (alighting) on water.Gunston, "The Cambridge Aerospace Dictionary", 2009. Seaplanes are usually divided into two categories based on their tec ...

s were conducted.

was propelled by two pairs of high- and low-pressure steam turbine

A steam turbine is a machine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work on a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Charles Parsons in 1884. Fabrication of a modern steam turbin ...

s that drove four screw propeller

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon ...

s, with steam provided by fourteen coal-burning water-tube boiler

A high pressure watertube boiler (also spelled water-tube and water tube) is a type of boiler in which water circulates in tubes heated externally by the fire. Fuel is burned inside the furnace, creating hot gas which boils water in the steam-gene ...

s ducted into two funnels

A funnel is a tube or pipe that is wide at the top and narrow at the bottom, used for guiding liquid or powder into a small opening.

Funnels are usually made of stainless steel, aluminium, glass, or plastic. The material used in its construc ...

. Her engines were rated to produce for a top speed of . She could steam for at a cruising speed of .

Mounting a main battery of eight 30.5 cm (12 in) guns, was the largest and most powerful German battlecruiser at the time. The ship's secondary battery

A rechargeable battery, storage battery, or secondary cell (formally a type of energy accumulator), is a type of electrical battery which can be charged, discharged into a load, and recharged many times, as opposed to a disposable or prima ...

consisted of twelve SK L/45 guns in single casemate

A casemate is a fortified gun emplacement or armored structure from which artillery, guns are fired, in a fortification, warship, or armoured fighting vehicle.Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary

When referring to Ancient history, antiquity, th ...

s in the superstructure

A superstructure is an upward extension of an existing structure above a baseline. This term is applied to various kinds of physical structures such as buildings, bridges, or ships.

Aboard ships and large boats

On water craft, the superstruct ...

, six per broadside

Broadside or broadsides may refer to:

Naval

* Broadside (naval), terminology for the side of a ship, the battery of cannon on one side of a warship, or their near simultaneous fire on naval warfare

Printing and literature

* Broadside (comic ...

. For defense against torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of se ...

s, she carried eight SK L/45 guns in individual pivot mount

A pivot gun was a type of cannon mounted on a fixed central emplacement which permitted it to be moved through a wide horizontal arc. They were a common weapon aboard ships and in land fortifications for several centuries but became obsolete aft ...

s on the superstructure, four of which were removed in 1916. An additional four 8.8 cm flak

Anti-aircraft warfare, counter-air or air defence forces is the battlespace response to aerial warfare, defined by NATO as "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It includes surface based, ...

guns were installed amidships. Four submerged torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s were carried; one was located in the bow, two on the broadside, and one in the stern.

was protected by an armor belt

Belt armor is a layer of heavy metal armor plated onto or within the outer hulls of warships, typically on battleships, battlecruisers and cruisers, and aircraft carriers.

The belt armor is designed to prevent projectiles from penetrating to t ...

that was thick in the central citadel

A citadel is the core fortified area of a town or city. It may be a castle, fortress, or fortified center. The term is a diminutive of "city", meaning "little city", because it is a smaller part of the city of which it is the defensive core.

In ...

of the ship where it protected the ammunition magazines

A magazine is a periodical publication, generally published on a regular schedule (often weekly or monthly), containing a variety of content. They are generally financed by advertising, purchase price, prepaid subscriptions, or by a combination ...

and propulsion machinery spaces. Her deck was thick, with the thicker armor sloping down at the sides to connect to the lower edge of the belt. Her main battery turrets had thick faces. Her secondary casemates received of armor protection. The forward conning tower

A conning tower is a raised platform on a ship or submarine, often armored, from which an officer in charge can conn the vessel, controlling movements of the ship by giving orders to those responsible for the ship's engine, rudder, lines, and gro ...

, where the ship's commander controlled the vessel, had 300 mm walls.

Service

Built by

Built by Blohm & Voss

Blohm+Voss (B+V), also written historically as Blohm & Voss, Blohm und Voß etc., is a German shipbuilding and engineering company. Founded in Hamburg in 1877 to specialise in steel-hulled ships, its most famous product was the World War II battle ...

at their yard in Hamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

, s keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element on a vessel. On some sailboats, it may have a hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose, as well. As the laying down of the keel is the initial step in the construction of a ship, in Br ...

was laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

in January 1912. The ship was named for Georg von Derfflinger

Georg von Derfflinger (20 March 1606 – 14 February 1695) was a field marshal in the army of Brandenburg-Prussia during and after the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648).

Early years

Born 1606 at Neuhofen an der Krems in Austria, into a family o ...

, a Prussian field marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, ordinarily senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army and as such few persons are appointed to it. It is considered as ...

during the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (80 ...

. She was to have been launched on 14 June 1913, and at the launching ceremony, the German General August von Mackensen

Anton Ludwig Friedrich August von Mackensen (born Mackensen; 6 December 1849 – 8 November 1945), ennobled as "von Mackensen" in 1899, was a German field marshal. He commanded successfully during World War I of 1914–1918 and became one of the ...

gave a speech. The wooden sledges upon which the ship rested became jammed; the ship moved only . A second attempt was successful on 12 July 1913. A crew composed of dockyard workers took the ship around the Skagen

Skagen () is Denmark's northernmost town, on the east coast of the Skagen Odde peninsula in the far north of Jutland, part of Frederikshavn Municipality in Nordjylland, north of Frederikshavn and northeast of Aalborg. The Port of Skagen is ...

to Kiel in early 1914; there she would complete fitting out

Fitting out, or outfitting, is the process in shipbuilding that follows the float-out/launching of a vessel and precedes sea trials. It is the period when all the remaining construction of the ship is completed and readied for delivery to her o ...

. As Europe drifted toward war during the July Crisis

The July Crisis was a series of interrelated diplomatic and military escalations among the major powers of Europe in the summer of 1914, Causes of World War I, which led to the outbreak of World War I (1914–1918). The crisis began on 28 June 1 ...

, the German naval command issued orders on the 27th placing the fleet on a state of heightened alert, though was not yet complete. The Germans feared that the Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

Baltic Fleet

, image = Great emblem of the Baltic fleet.svg

, image_size = 150

, caption = Baltic Fleet Great ensign

, dates = 18 May 1703 – present

, country =

, allegiance = (1703–1721) (1721–1917) (1917–1922) (1922–1991)(1991–present)

...

would launch a surprise torpedo-boat attack at the start of the war, as the Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

navy had done to the Russians in the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

, but the attack did not materialize when World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

broke out the next day.

The ship was placed in commission on 1September to begin sea trial

A sea trial is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a " shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on open water, and ...

s. In late October, the vessel was assigned to I Scouting Group

The I Scouting Group (german: I. Aufklärungsgruppe) was a special reconnaissance unit within the German Kaiserliche Marine. The unit was famously commanded by Admiral Franz von Hipper during World War I. The I Scouting Group was one of the most ...

, but damage to the ship's turbines during trials prevented her from joining the unit until 16 November. The ship's first wartime operation took place on 20 November; sortied with the light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to thi ...

s and and V Torpedoboat Flotilla for a sweep some northwest of the island of Helgoland

Heligoland (; german: Helgoland, ; Heligolandic Frisian: , , Mooring Frisian: , da, Helgoland) is a small archipelago in the North Sea. A part of the German state of Schleswig-Holstein since 1890, the islands were historically possessions ...

. They failed to locate any British forces and thereafter returned to port.

Bombardment of Scarborough, Hartlepool, and Whitby

s first combat operation was a raid on the English coastal towns ofScarborough Scarborough or Scarboro may refer to:

People

* Scarborough (surname)

* Earl of Scarbrough

Places Australia

* Scarborough, Western Australia, suburb of Perth

* Scarborough, New South Wales, suburb of Wollongong

* Scarborough, Queensland, su ...

, Hartlepool

Hartlepool () is a seaside and port town in County Durham, England. It is the largest settlement and administrative centre of the Borough of Hartlepool. With an estimated population of 90,123, it is the second-largest settlement in County ...

, and Whitby

Whitby is a seaside town, port and civil parish in the Scarborough borough of North Yorkshire, England. Situated on the east coast of Yorkshire at the mouth of the River Esk, Whitby has a maritime, mineral and tourist heritage. Its East Clif ...

. One raid had already been conducted by the battlecruisers of I Scouting Group, on the town of Yarmouth

Yarmouth may refer to:

Places Canada

*Yarmouth County, Nova Scotia

**Yarmouth, Nova Scotia

**Municipality of the District of Yarmouth

**Yarmouth (provincial electoral district)

**Yarmouth (electoral district)

* Yarmouth Township, Ontario

*New ...

in late 1914. Admiral Friedrich von Ingenohl

Gustav Heinrich Ernst Friedrich von Ingenohl (30 June 1857 – 19 December 1933) was a German admiral from Neuwied best known for his command of the German High Seas Fleet at the beginning of World War I.

He was the son of a tradesman. H ...

, the commander of the High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet (''Hochseeflotte'') was the battle fleet of the German Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. The formation was created in February 1907, when the Home Fleet (''Heimatflotte'') was renamed as the High Seas ...

, decided to conduct another raid on the English coast. His goal was to lure a portion of the Grand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from the ...

into combat where it could be isolated and destroyed. At 03:20 on 15 December, Rear Admiral Franz von Hipper

Franz Ritter von Hipper (13 September 1863 – 25 May 1932) was an admiral in the German Imperial Navy (''Kaiserliche Marine''). Franz von Hipper joined the German Navy in 1881 as an officer cadet. He commanded several torpedo boat units an ...

, with his flag aboard , departed the Jade estuary. Following were , , , and , along with the light cruisers , , , and , and two squadrons of torpedo boats. The ships sailed north past the island of Heligoland

Heligoland (; german: Helgoland, ; Heligolandic Frisian: , , Mooring Frisian: , da, Helgoland) is a small archipelago in the North Sea. A part of the German state of Schleswig-Holstein since 1890, the islands were historically possessions ...

, until they reached the Horns Reef

Horns Rev is a shallow sandy reef of glacial deposits in the eastern North Sea, about off the westernmost point of Denmark, Blåvands Huk.

lighthouse, at which point they turned west towards Scarborough. Twelve hours after Hipper left the Jade, the High Seas Fleet departed to provide distant cover. The main fleet consisted of 14 dreadnought

The dreadnought (alternatively spelled dreadnaught) was the predominant type of battleship in the early 20th century. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's , had such an impact when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her ...

s, eight pre-dreadnought

Pre-dreadnought battleships were sea-going battleships built between the mid- to late- 1880s and 1905, before the launch of in 1906. The pre-dreadnought ships replaced the ironclad battleships of the 1870s and 1880s. Built from steel, prote ...

s and a screening force of two armored cruiser

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a battleship and fast eno ...

s, seven light cruisers, and fifty-four torpedo boats.

On 26 August 1914, the German light cruiser had run aground in the Gulf of Finland

The Gulf of Finland ( fi, Suomenlahti; et, Soome laht; rus, Фи́нский зали́в, r=Finskiy zaliv, p=ˈfʲinskʲɪj zɐˈlʲif; sv, Finska viken) is the easternmost arm of the Baltic Sea. It extends between Finland to the north and E ...

; the wreck was captured by the Russian navy, which found code books used by the German navy, along with navigational charts for the North Sea. The Russians passed these documents to the Royal Navy, whose cryptographic unit—Room 40

Room 40, also known as 40 O.B. (old building; officially part of NID25), was the cryptanalysis section of the British Admiralty during the First World War.

The group, which was formed in October 1914, began when Rear-Admiral Henry Oliver, the ...

—began decrypting German signals. On 14 December, they intercepted messages relating to the planned bombardment of Scarborough. The exact details of the plan were unknown, and the British assumed the High Seas Fleet would remain safely in port, as in the previous bombardment. Vice Admiral David Beatty's four battlecruisers, supported by the 3rd Cruiser Squadron and the 1st Light Cruiser Squadron, along with the 2nd Battle Squadron

The 2nd Battle Squadron was a naval squadron of the British Royal Navy consisting of battleships. The 2nd Battle Squadron was initially part of the Royal Navy's Grand Fleet. After World War I the Grand Fleet was reverted to its original name, t ...

's six dreadnoughts, were to ambush Hipper's battlecruisers.

Battle of Dogger Bank

In early January 1915, the German naval command became aware that British ships were reconnoitering in theDogger Bank

Dogger Bank (Dutch: ''Doggersbank'', German: ''Doggerbank'', Danish: ''Doggerbanke'') is a large sandbank in a shallow area of the North Sea about off the east coast of England.

During the last ice age the bank was part of a large landmass c ...

area. Admiral Ingenohl was initially reluctant to attempt to destroy these forces, because I Scouting Group was temporarily weakened while was in drydock for periodic maintenance. Richard Eckermann, the Chief of Staff of the High Seas Fleet, insisted on the operation, and so Ingenohl relented and ordered Hipper to take his battlecruisers to the Dogger Bank. On 23 January, Hipper sortied, with in the lead, followed by , , and , along with the light cruisers , , , and and 19 torpedo boats from V Flotilla and II and XVIII Half-Flotillas. and were assigned to the forward screen, while and were assigned to the starboard and port, respectively. Each light cruiser had a half-flotilla of torpedo boats attached.

Again, interception and decryption of German wireless signals played an important role. Although they were unaware of the exact plans, the cryptographers of Room 40 deduced that Hipper would be conducting an operation in the Dogger Bank area. To counter it, Beatty's 1st Battlecruiser Squadron

The First Battlecruiser Squadron was a Royal Navy squadron of battlecruisers that saw service as part of the Grand Fleet during the First World War. It was created in 1909 as the First Cruiser Squadron and was renamed in 1913 to First Battle Cru ...

, Rear Admiral Archibald Moore's 2nd Battlecruiser Squadron and Commodore William Goodenough

Admiral Sir William Edmund Goodenough (2 June 1867 – 30 January 1945) was a senior Royal Navy officer of World War I. He was the son of James Graham Goodenough.

Naval career

Goodenough joined the Royal Navy in 1882. He was appointed Commande ...

's 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron were to rendezvous with Commodore Reginald Tyrwhitt

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Reginald Yorke Tyrwhitt, 1st Baronet, (; 10 May 1870 – 30 May 1951) was a Royal Navy officer. During the First World War he served as commander of the Harwich Force. He led a supporting naval force of 31 destroyers a ...

's Harwich Force

The Harwich Force originally called Harwich Striking Force was a squadron of the Royal Navy, formed during the First World War and based in Harwich. It played a significant role in the war.

History

After the outbreak of the First World War, a p ...

at 08:00 on 24 January, approximately north of the Dogger Bank.

At 08:14, spotted the light cruiser and several destroyers from the Harwich Force. ''Aurora'' challenged with a search light, at which point attacked ''Aurora'' and scored two hits. ''Aurora'' returned fire and scored two hits on in retaliation. Hipper immediately turned his battlecruisers towards the gunfire, when, almost simultaneously, spotted a large amount of smoke to the northwest of her position. This was identified as a number of large British warships steaming towards Hipper's ships.

Hipper turned south to flee, but was limited to , which was the maximum speed of the older armored cruiser . The pursuing British battlecruisers were steaming at , and quickly caught up to the German ships. At 09:52, the battlecruiser opened fire on from a range of approximately ; shortly thereafter, and began firing as well. At 10:09, the British guns made their first hit on . Two minutes later, the German ships began returning fire, primarily concentrating on ''Lion'', from a range of . At 10:28, ''Lion'' was struck on the waterline, which tore a hole in the side of the ship and flooded a coal bunker. At 10:30, , the fourth ship in Beatty's line, came within range of and opened fire. By 10:35, the range had closed to , at which point the entire German line was within the effective range of the British ships. Beatty ordered his battlecruisers to engage their German counterparts. Confusion aboard ''Tiger'' led the captain to believe he was to fire on , which left able to fire without distraction. During this period of the battle, was hit once, but the shell did only minor damage. Two armor plates in the hull were forced inward and some of the protective coal bunkers were flooded.

At 10:40, one of ''Lion''s shells struck causing nearly catastrophic damage that knocked out both rear turrets and killed 159 men. The executive officer ordered both magazines flooded to avoid a flash fire that would have destroyed the ship. By this time, the German battlecruisers had zeroed in on ''Lion'', scoring repeated hits. At 11:01, an shell from struck ''Lion'' and knocked out two of her dynamos. At 11:18, two of shells hit ''Lion'', one of which struck the waterline and penetrated the belt, allowing seawater to enter the port feed tank. ''Lion'' had to turn off its engines due to seawater contamination and as a result fell out of the line.

By this time, was severely damaged after having been pounded by heavy shells. The chase ended when there were several reports of U-boats ahead of the British ships; Beatty quickly ordered evasive maneuvers, which allowed the German ships to increase the distance to their pursuers. At this time, ''Lion''s last operational dynamo failed, which dropped her speed to . Beatty, in the stricken ''Lion'', ordered the remaining battlecruisers to "engage the enemy's rear," but signal confusion caused the ships to solely target , allowing , , and to escape. was hit by more than 70 shells from the British battlecruisers over the course of the battle. The severely damaged warship capsized and sank at approximately 13:10. By the time Beatty regained control over his ships, after having boarded ''Princess Royal'', the German ships had too great a lead for the British to catch them; at 13:50, he broke off the chase.

Hipper turned south to flee, but was limited to , which was the maximum speed of the older armored cruiser . The pursuing British battlecruisers were steaming at , and quickly caught up to the German ships. At 09:52, the battlecruiser opened fire on from a range of approximately ; shortly thereafter, and began firing as well. At 10:09, the British guns made their first hit on . Two minutes later, the German ships began returning fire, primarily concentrating on ''Lion'', from a range of . At 10:28, ''Lion'' was struck on the waterline, which tore a hole in the side of the ship and flooded a coal bunker. At 10:30, , the fourth ship in Beatty's line, came within range of and opened fire. By 10:35, the range had closed to , at which point the entire German line was within the effective range of the British ships. Beatty ordered his battlecruisers to engage their German counterparts. Confusion aboard ''Tiger'' led the captain to believe he was to fire on , which left able to fire without distraction. During this period of the battle, was hit once, but the shell did only minor damage. Two armor plates in the hull were forced inward and some of the protective coal bunkers were flooded.

At 10:40, one of ''Lion''s shells struck causing nearly catastrophic damage that knocked out both rear turrets and killed 159 men. The executive officer ordered both magazines flooded to avoid a flash fire that would have destroyed the ship. By this time, the German battlecruisers had zeroed in on ''Lion'', scoring repeated hits. At 11:01, an shell from struck ''Lion'' and knocked out two of her dynamos. At 11:18, two of shells hit ''Lion'', one of which struck the waterline and penetrated the belt, allowing seawater to enter the port feed tank. ''Lion'' had to turn off its engines due to seawater contamination and as a result fell out of the line.

By this time, was severely damaged after having been pounded by heavy shells. The chase ended when there were several reports of U-boats ahead of the British ships; Beatty quickly ordered evasive maneuvers, which allowed the German ships to increase the distance to their pursuers. At this time, ''Lion''s last operational dynamo failed, which dropped her speed to . Beatty, in the stricken ''Lion'', ordered the remaining battlecruisers to "engage the enemy's rear," but signal confusion caused the ships to solely target , allowing , , and to escape. was hit by more than 70 shells from the British battlecruisers over the course of the battle. The severely damaged warship capsized and sank at approximately 13:10. By the time Beatty regained control over his ships, after having boarded ''Princess Royal'', the German ships had too great a lead for the British to catch them; at 13:50, he broke off the chase.

Bombardment of Yarmouth and Lowestoft

also took part in the bombardment of Yarmouth and Lowestoft on 24–25 April 1916. Hipper was away on sick leave, so the German ships were under the command of Konteradmiral

also took part in the bombardment of Yarmouth and Lowestoft on 24–25 April 1916. Hipper was away on sick leave, so the German ships were under the command of Konteradmiral Friedrich Boedicker

Friedrich Boedicker, (13 March 1866, in Kassel – 20 September 1944) was a '' Vizeadmiral'' (vice admiral) of the Kaiserliche Marine during the First World War.

Biography

Boedicker is perhaps best known for being present at the Battle of Jutla ...

. , her newly commissioned sister ship

A sister ship is a ship of the same class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They often share a ...

, and the veterans , and left the Jade Estuary at 10:55 on 24 April. They were supported by a screening force of six light cruisers and two torpedo boat flotillas. The heavy units of the High Seas Fleet, under the command of Admiral Reinhard Scheer

Carl Friedrich Heinrich Reinhard Scheer (30 September 1863 – 26 November 1928) was an Admiral in the Imperial German Navy (''Kaiserliche Marine''). Scheer joined the navy in 1879 as an officer cadet and progressed through the ranks, commandin ...

, sailed at 13:40, with the objective to provide distant support for Boedicker's ships. The British Admiralty was made aware of the German sortie through the interception of German wireless

Wireless communication (or just wireless, when the context allows) is the transfer of information between two or more points without the use of an electrical conductor, optical fiber or other continuous guided medium for the transfer. The most ...

signals, and deployed the Grand Fleet at 15:50.

By 14:00, Boedicker's ships had reached a position off Norderney

Norderney ( nds, Nördernee) is one of the seven populated East Frisian Islands off the North Sea coast of Germany.

The island is , having a total area of about and is therefore Germany's ninth-largest island. Norderney's population amounts ...

, at which point he turned his ships northward to avoid the Dutch observers on the island of Terschelling

Terschelling (; fry, Skylge; Terschelling dialect: ''Schylge'') is a municipality and an island in the northern Netherlands, one of the West Frisian Islands. It is situated between the islands of Vlieland and Ameland.

Wadden Islanders are k ...

. At 15:38, struck a naval mine

A naval mine is a self-contained explosive device placed in water to damage or destroy surface ships or submarines. Unlike depth charges, mines are deposited and left to wait until they are triggered by the approach of, or contact with, any ...

, which tore a hole in her hull, just abaft the starboard broadside torpedo tube, allowing of water to enter the ship. turned back, with the screen of light cruisers, at a speed of . The four remaining battlecruisers turned south immediately in the direction of Norderney to avoid further mine damage. By 16:00, was clear of imminent danger, so the ship stopped to allow Boedicker to disembark. The torpedo boat brought Boedicker to .

At 04:50 on 25 April, the German battlecruisers were approaching Lowestoft when the light cruisers and , which had been covering the southern flank, spotted the light cruisers and destroyers of Commodore Tyrwhitt's Harwich Force. Boedicker refused to be distracted by the British ships, and instead trained his ships' guns on Lowestoft. At a range of approximately , the German battlecruisers destroyed two shore batteries and inflicted other damage to the town, including the destruction of some 200 houses.

At 05:20, the German raiders turned north, towards Yarmouth, which they reached by 05:42. The visibility was so poor that the German ships fired one salvo

A salvo is the simultaneous discharge of artillery or firearms including the firing of guns either to hit a target or to perform a salute. As a tactic in warfare, the intent is to cripple an enemy in one blow and prevent them from fighting b ...

each, with the exception of , which fired fourteen rounds from her main battery. The German ships turned back south, and at 05:47 encountered for the second time the Harwich Force, which had by then been engaged by the six light cruisers of the screening force. Boedicker's ships opened fire from a range of . Tyrwhitt immediately turned his ships around and fled south, but not before the cruiser sustained severe damage. Due to reports of British submarines and torpedo attacks, Boedicker broke off the chase and turned back east towards the High Seas Fleet. At this point, Scheer, who had been warned of the Grand Fleet's sortie from Scapa Flow, turned back towards Germany.

Battle of Jutland

Almost immediately after the Lowestoft raid, Scheer began planning another foray into the North Sea. He had initially intended to launch the operation in mid-May, but the mine damage to had proved difficult to repair, and Scheer was unwilling to embark on a major raid without his battlecruiser forces at full strength. At noon on 28 May, the repairs to were finally completed, and the ship returned to I Scouting Group.

and the rest of Hipper's I Scouting Group battlecruisers lay anchored in the outer Jade

Almost immediately after the Lowestoft raid, Scheer began planning another foray into the North Sea. He had initially intended to launch the operation in mid-May, but the mine damage to had proved difficult to repair, and Scheer was unwilling to embark on a major raid without his battlecruiser forces at full strength. At noon on 28 May, the repairs to were finally completed, and the ship returned to I Scouting Group.

and the rest of Hipper's I Scouting Group battlecruisers lay anchored in the outer Jade roadstead

A roadstead (or ''roads'' – the earlier form) is a body of water sheltered from rip currents, spring tides, or ocean swell where ships can lie reasonably safely at anchor without dragging or snatching.United States Army technical manual, TM 5- ...

on the night of 30 May. At 02:00 CET

CET or cet may refer to:

Places

* Cet, Albania

* Cet, standard astronomical abbreviation for the constellation Cetus

* Colchester Town railway station (National Rail code CET), in Colchester, England

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Comcast Ente ...

, the ships steamed out towards the Skagerrak

The Skagerrak (, , ) is a strait running between the Jutland peninsula of Denmark, the southeast coast of Norway and the west coast of Sweden, connecting the North Sea and the Kattegat sea area through the Danish Straits to the Baltic Sea.

The ...

at a speed of . was the second ship in the line of five, ahead of , and to the rear of , which had by that time become the group flagship. II Scouting Group, consisting of the light cruisers , Boedicker's flagship, , , and , and 30 torpedo boats of II, VI, and IX Flotillas, accompanied Hipper's battlecruisers.

An hour and a half later, the High Seas Fleet left the Jade; the force was composed of 16 dreadnoughts. The High Seas Fleet was accompanied by IV Scouting Group, composed of the light cruisers , , , , and , and 31 torpedo boats of I, III, V, and VII Flotillas, led by the light cruiser . The six pre-dreadnoughts of II Battle Squadron had departed from the Elbe roads at 02:45, and rendezvoused with the battle fleet at 05:00.

Run to the south

Shortly before 16:00, Hipper's force encountered the six ships of Vice Admiral Beatty's 1st and 2nd Battlecruiser Squadrons. The German ships were the first to open fire, at a range of approximately . When the British ships began returning fire, confusion among the British battlecruisers resulted in being engaged by both ''New Zealand'' and ''Tiger''. The British rangefinders had misread the range to their German targets, and so the first salvos fired by the British ships fell a mile past the German battlecruisers. Due to errors in British communication, was not engaged during the first ten minutes of the battle. s gunnery officer, Georg von Hase later remarked "By some mistake we were being left out. I laughed grimly and now I began to engage our enemy with complete calm, as at gun practice, and with continually increasing accuracy." At 17:03, the British battlecruiser exploded after fifteen minutes of gunfire from . Shortly thereafter the second half of Beatty's force, the four s of the

Shortly before 16:00, Hipper's force encountered the six ships of Vice Admiral Beatty's 1st and 2nd Battlecruiser Squadrons. The German ships were the first to open fire, at a range of approximately . When the British ships began returning fire, confusion among the British battlecruisers resulted in being engaged by both ''New Zealand'' and ''Tiger''. The British rangefinders had misread the range to their German targets, and so the first salvos fired by the British ships fell a mile past the German battlecruisers. Due to errors in British communication, was not engaged during the first ten minutes of the battle. s gunnery officer, Georg von Hase later remarked "By some mistake we were being left out. I laughed grimly and now I began to engage our enemy with complete calm, as at gun practice, and with continually increasing accuracy." At 17:03, the British battlecruiser exploded after fifteen minutes of gunfire from . Shortly thereafter the second half of Beatty's force, the four s of the 5th Battle Squadron

The 5th Battle Squadron was a squadron of the British Royal Navy consisting of battleships. The 5th Battle Squadron was initially part of the Royal Navy's Second Fleet. During the First World War, the Home Fleet was renamed the Grand Fleet.

Hist ...

, came into range and began firing at and .

Following severe damage inflicted by on ''Lion'', lost sight of the British ship, and so at 17:16 transferred her fire to ''Queen Mary''. was also engaging ''Queen Mary'', and under the combined fire of the two battlecruisers, ''Queen Mary'' was hit repeatedly in quick succession. Observers on ''New Zealand'' and ''Tiger'', the ships behind and ahead respectively, reported three shells from a salvo of four struck the ship at the same time. Two more hits followed, and a gigantic explosion erupted amidships; a billowing cloud of black smoke poured from the burning ship, which had broken in two. The leading ships of the German High Seas fleet had by 18:00 come within effective range of the British battlecruisers and ''Queen Elizabeth''-class battleships and had begun trading shots with them. Between 18:09 and 18:19, was hit by a shell from either or . At 18:55, was hit again; this shell struck the bow and tore a hole that allowed some 300 tons of water to enter the ship.

Battlefleets engage

Shortly after 19:00, the German cruiser had become disabled by a shell from the battlecruiser ; the German battlecruisers made a 16-point turn to the northeast and made for the crippled cruiser at high speed. At 19:15, they spotted the British armored cruiser , which had joined the attack on . Hipper initially hesitated, believing the ship was the German cruiser , but at 19:16, Harder, s commanding officer, ordered his ships' guns to fire. The other German battlecruisers and battleships joined in the melee; ''Defence'' was struck by several heavy-caliber shells from the German ships. One salvo penetrated the ship's ammunition magazines and a massive explosion destroyed the cruiser. By 19:24, the3rd Battlecruiser Squadron

The 3rd Battlecruiser Squadron was a short-lived Royal Navy squadron of battlecruisers that saw service as part of the Grand Fleet during the First World War.

Creation

The 3rd Battlecruiser Squadron was created in 1915, with the return to home ...

had formed up with Beatty's remaining battlecruisers ahead of the German line. The leading British ships spotted and and began firing on them. In the span of eight minutes, the battlecruiser ''Invincible'' scored eight hits on . In return, both and concentrated their fire on their antagonist, and at 19:31 fired her final salvo at ''Invincible''. Shortly thereafter the forward magazine detonated and the ship disappeared in a series of massive explosions.

By 19:30, the High Seas Fleet, which was by that point pursuing the British battlecruisers, had not yet encountered the Grand Fleet. Scheer had been considering retiring his forces before darkness exposed his ships to torpedo boat attack. He had not yet made a decision when his leading battleships encountered the main body of the Grand Fleet. This development made it impossible for Scheer to retreat, for doing so would have sacrificed the slower pre-dreadnought battleships of II Battle Squadron. If he chose to use his dreadnoughts and battlecruisers to cover their retreat, he would have subjected his strongest ships to overwhelming British fire. Instead, Scheer ordered his ships to turn 16 points to starboard, which would bring the pre-dreadnoughts to the relative safety of the disengaged side of the German battle line.

and the other battlecruisers followed the move, which put them astern of the leading German battleship, . Hipper's badly battered ships gained a temporary moment of respite, and uncertainty over the exact location and course of Scheer's ships led Admiral Jellicoe to turn his ships eastward, towards what he thought was the likely path of the German retreat. The German fleet was instead sailing west, but Scheer ordered a second 16-point turn, which reversed course and pointed his ships at the center of the British fleet. The German fleet came under intense fire from the British line, and Scheer sent , , , and at high speed towards the British fleet, in an attempt to disrupt their formation and gain time for his main force to retreat. By 20:17, the German battlecruisers had closed to within of , at which point Scheer directed the ships to engage the lead ship of the British line. Three minutes later, the German battlecruisers turned in retreat, covered by a torpedo boat attack.

Withdrawal

A pause in the battle at dusk (approximately 20:20 to 21:10) allowed and the other German battlecruisers to cut away wreckage that interfered with the main guns, extinguish fires, repair the fire control and signal equipment, and prepare the searchlights for nighttime action. During this period, the German fleet reorganized into a well-ordered formation in reverse order, when the German light forces encountered the British screen shortly after 21:00. The renewed gunfire gained Beatty's attention, so he turned his battlecruisers westward. At 21:09, he sighted the German battlecruisers, and drew to within before opening fire at 21:20. In the ensuing melee, was hit several times; at 21:34, a heavy shell struck her last operational gun turret and put it out of action. The German ships returned fire with every gun available, and at 21:32 hit both ''Lion'' and ''Princess Royal'' in the darkness. The maneuvering of the German battlecruisers forced the leading I Battle Squadron to turn westward to avoid collision. This brought the pre-dreadnoughts of II Battle Squadron directly between the two lines of battlecruisers. In doing so, this prevented the British ships from pursuing their German counterparts when they turned southward. The British battlecruisers opened fire on the old battleships; the German ships turned southwest to bring all their guns to bear against the British ships. This engagement lasted only a few minutes before Admiral Mauve turned his ships 8 points to starboard; the British inexplicably did not pursue. Close to the end of the battle, at 03:55, Hipper transmitted a report to Admiral Scheer informing him of the tremendous damage his ships had suffered. By that time, and had only two operational guns each, was flooded with 1,000 tons of water, had sunk, and was severely damaged. Hipper reported: "I Scouting Group was therefore no longer of any value for a serious engagement, and was consequently directed to return to harbor by the Commander-in-Chief, while he himself determined to await developments off Horns Reef with the battlefleet." During the course of the battle, was hit 17 times by heavy caliber shells and nine times by secondary guns. She was in dock for repairs until 15 October. fired 385 shells from her main battery, another 235 rounds from her secondary guns, and one torpedo. Her crew suffered 157 men killed and another 26 men wounded; this was the highest casualty rate on any ship not sunk during the battle. Because of her stalwart resistance at Jutland, the British nicknamed her "Iron Dog".Later operations

After returning to the fleet, conducted battle readiness training in the Baltic Sea for the rest of October and all of November. By this time, the Germans had abandoned offensive use of the surface fleet, favoring instead theU-boat campaign

The U-boat Campaign from 1914 to 1918 was the World War I naval campaign fought by German U-boats against the trade routes of the Allies. It took place largely in the seas around the British Isles and in the Mediterranean.

The German Empire r ...

against British merchant shipping. and the rest of the fleet were used to defend German waters so the U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare role ...

s could continue to operate. During the Second Battle of Heligoland Bight

The Second Battle of Heligoland Bight, also the Action in the Helgoland Bight and the , was an inconclusive naval engagement fought between British and German squadrons on 17 November 1917 during the First World War.

Background

British minela ...

in November 1917, sailed from port to assist the German light cruisers of II Scouting Group, but by the time she and the other battlecruisers arrived on the scene, the British raiders had fled northward. On 20 April 1918, covered a minelaying operation off Terschelling.

Beginning in late 1917, the High Seas Fleet had begun to conduct raids on the supply convoy

A convoy is a group of vehicles, typically motor vehicles or ships, traveling together for mutual support and protection. Often, a convoy is organized with armed defensive support and can help maintain cohesion within a unit. It may also be used ...

s between Britain and Norway. In October and December, German cruisers and destroyers intercepted and destroyed two British convoys to Norway. This prompted Beatty, now the Commander in Chief of the Grand Fleet, to detach several battleships and battlecruisers to protect the convoys. This presented to Scheer the opportunity for which he had been waiting the entire war: the chance to isolate and eliminate a portion of the Grand Fleet. Hipper planned the operation: the battlecruisers, including , and their escorting light cruisers and destroyers, would attack one of the large convoys, while the rest of the High Seas Fleet stood by, ready to attack the British battleship squadron.

At 05:00 on 23 April 1918, the German fleet departed from the Schillig roadstead. Hipper ordered wireless transmissions be kept to a minimum to prevent radio intercepts by British intelligence. At 06:10 the German battlecruisers had reached a position approximately southwest of Bergen

Bergen (), historically Bjørgvin, is a city and municipality in Vestland county on the west coast of Norway. , its population is roughly 285,900. Bergen is the second-largest city in Norway. The municipality covers and is on the peninsula of ...

when lost her inner starboard propeller, which severely damaged the ship's engines. The crew effected temporary repairs that allowed the ship to steam at , but it was decided to take the ship under tow. Despite this setback, Hipper continued northward. By 14:00, Hipper's force had crossed the convoy route several times but had found nothing. At 14:10, Hipper turned his ships southward. By 18:37, the German fleet had made it back to the defensive minefields surrounding their bases. It was later discovered that the convoy had left port a day later than expected by the German planning staff.

Fate

was to have taken part in what would have amounted to the "death ride" of the High Seas Fleet shortly before the end of World War I. The bulk of the High Seas Fleet was to have sortied from its base in Wilhelmshaven to engage the British Grand Fleet; Scheer—by now the of the fleet—intended to inflict as much damage as possible on the British navy, in order to retain a better bargaining position for Germany, whatever the cost to the fleet. While the fleet was consolidating in Wilhelmshaven, war-weary sailors began deserting ''en masse''. As and passed through the locks that separated Wilhelmshaven's inner harbor and roadstead, some 300 men from both ships climbed over the side and disappeared ashore. On 24 October 1918, the order was given to sail from Wilhelmshaven. Starting on the night of 29 October, sailorsmutinied

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military, of a crew or of a crew of pirates) to oppose, change, or overthrow an organization to which they were previously loyal. The term is commonly used for a rebellion among members ...

on several battleships; three ships from III Squadron refused to weigh anchor, and the battleships and reported acts of sabotage. The order to sail was rescinded in the face of this open revolt. The following month, the German Revolution

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

toppled the monarchy and was quickly followed by the Armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the La ...

that ended the war.

Following Germany's capitulation, the Allies demanded that the majority of the High Seas Fleet be interned in the British naval base at

Following Germany's capitulation, the Allies demanded that the majority of the High Seas Fleet be interned in the British naval base at Scapa Flow

Scapa Flow viewed from its eastern end in June 2009

Scapa Flow (; ) is a body of water in the Orkney Islands, Scotland, sheltered by the islands of Mainland, Graemsay, Burray,S. C. George, ''Jutland to Junkyard'', 1973. South Ronaldsay and ...

pending an ultimate resolution of their fate. On 21 November 1918, under the command of Rear Admiral Ludwig von Reuter

Hans Hermann Ludwig von Reuter (9 February 1869 – 18 December 1943) was a German admiral who commanded the High Seas Fleet when it was interned at Scapa Flow in the north of Scotland at the end of World War I. On 21 June 1919 he ordered ...

, the ships sailed from their base in Germany for the last time. The fleet rendezvoused with the light cruiser , before meeting a flotilla of 370 British, American, and French warships for the voyage to Scapa Flow. Once the ships were interned, their breech block

A breechblock (or breech block) is the part of the firearm action that closes the breech of a breech loading weapon (whether small arms or artillery) before or at the moment of firing. It seals the breech and contains the pressure generated by t ...

s were removed, which disabled their guns.

The fleet remained in captivity during the negotiations that ultimately produced the Versailles Treaty

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

. It became apparent to Reuter that the British intended to seize the German ships on 21 June 1919, which was the deadline by which Germany was to have signed the peace treaty. Unaware the deadline had been extended to 23 June, Reuter ordered his ships be sunk. On the morning of 21 June, the British fleet left Scapa Flow to conduct training maneuvers. With the majority of the British fleet away, Reuter transmitted the order to his ships at 11:20. sank at 14:45. The ship was raised in 1939 and was anchored, still capsized, off the island of Risa Risa may refer to:

* Risa (given name), a feminine given name

* Risa (Star Trek), a fictional planet

* Radioiodinated serum albumin

* Recording Industry of South Africa

* Ribosomal Intergenic Spacer analysis

See also

*

*

* Rise (disambiguation) ...

until 1946, at which point the ship gained the dubious distinction of having spent more time afloat upside down than she had right way up. was then sent to Faslane Port

His Majesty's Naval Base, Clyde (HMNB Clyde; also HMS ''Neptune''), primarily sited at Faslane on the Gare Loch, is one of three operating bases in the United Kingdom for the Royal Navy (the others being HMNB Devonport and HMNB Portsmouth). It ...

and broken up by 1948. One of the ship's bells was delivered to the German Federal Navy on 30 August 1965; the other is exhibited outside St Michael's Roman Catholic Church on the Outer Hebrides island of Eriskay

Eriskay ( gd, Èirisgeigh), from the Old Norse for "Eric's Isle", is an island and community council area of the Outer Hebrides in northern Scotland with a population of 143, as of the 2011 census. It lies between South Uist and Barra and is ...

.

Notes

Footnotes

Citations

References

* * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Derfflinger Derfflinger-class battlecruisers World War I battlecruisers of Germany Ships built in Hamburg 1913 ships World War I warships scuttled at Scapa Flow Maritime incidents in 1919