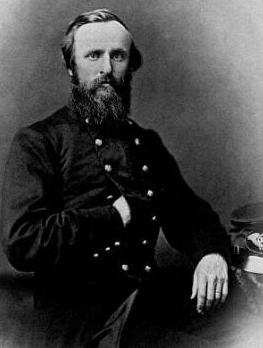

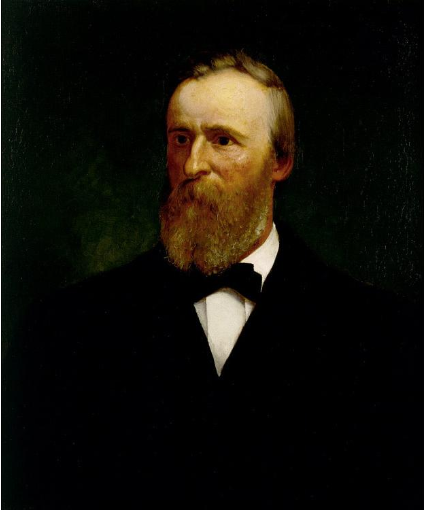

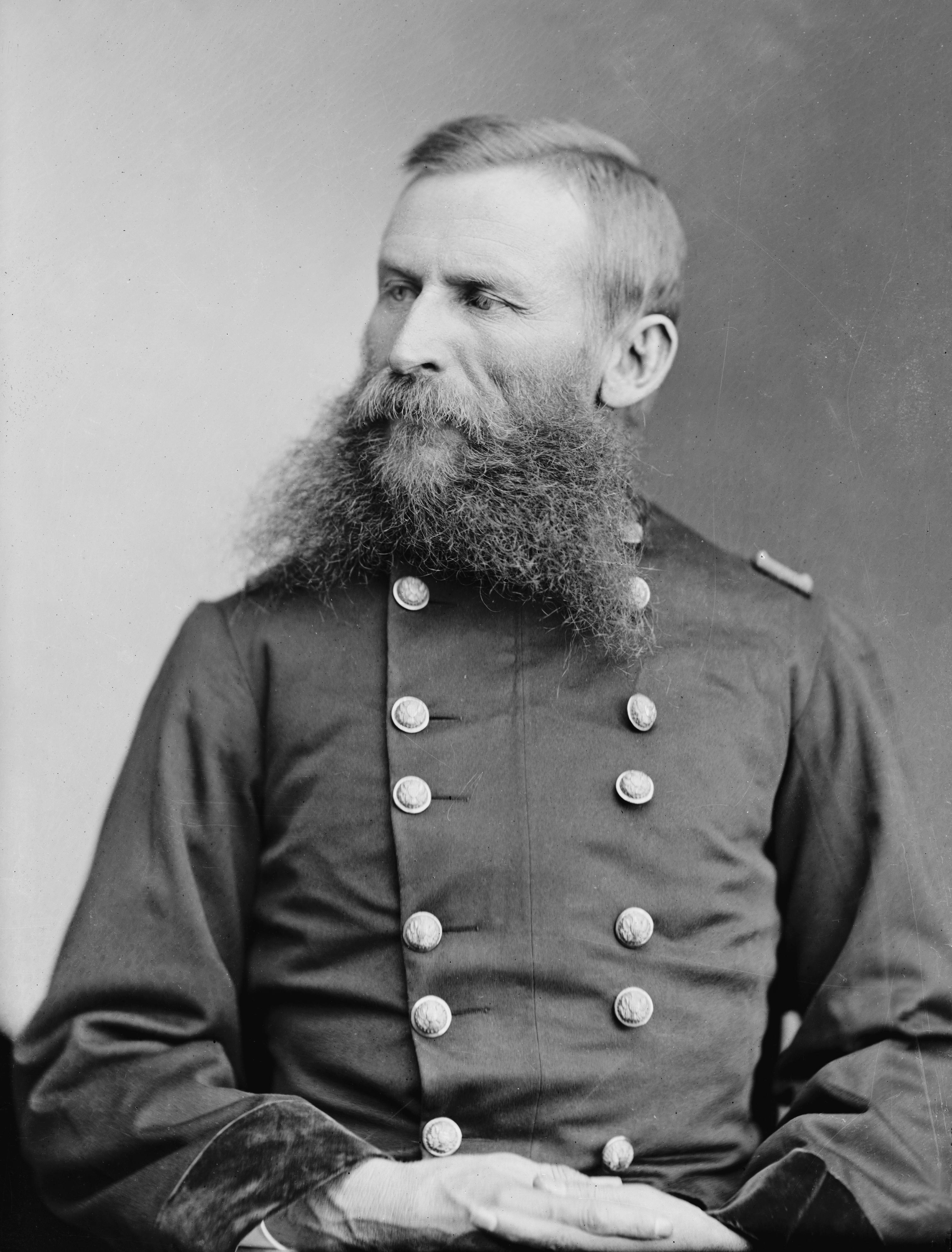

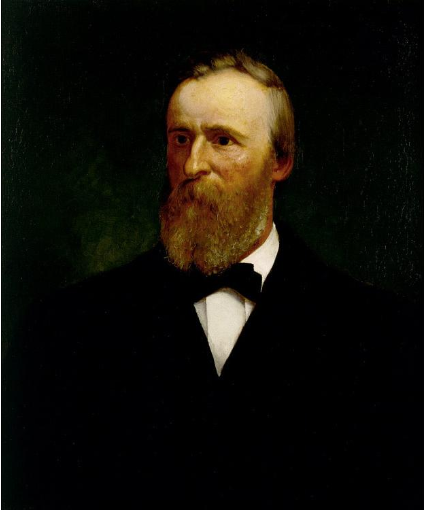

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th

president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal gove ...

from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the

U.S. House of Representatives and as

governor of Ohio

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

. Before the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

, Hayes was a lawyer and staunch

abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

who defended refugee slaves in court proceedings. He served in the

Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

and the House of Representatives before assuming the presidency. His presidency represents a turning point in U.S. history, as historians consider it the formal end of

Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

* Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

. Hayes, a prominent member of the Republican "

Half-Breed" faction, placated both Southern Democrats and

Whiggish

Whig history (or Whig historiography) is an approach to historiography that presents history as a journey from an oppressive and benighted past to a "glorious present". The present described is generally one with modern forms of liberal democrac ...

Republican businessmen by ending the federal government's involvement in attempting to bring racial equality in

the South.

As an attorney in Ohio, Hayes served as

Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line w ...

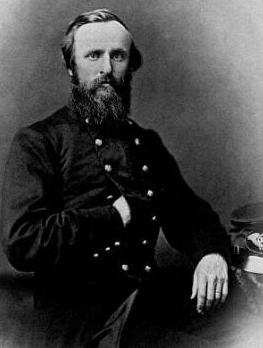

's city solicitor from 1858 to 1861. At the start of the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

, he left a fledgling political career to join the Union Army as an officer. Hayes was wounded five times, most seriously at the

Battle of South Mountain

The Battle of South Mountain—known in several early Southern accounts as the Battle of Boonsboro Gap—was fought on September 14, 1862, as part of the Maryland campaign of the American Civil War. Three pitched battles were fought for posses ...

in 1862. He earned a reputation for bravery in combat and was promoted to

brevet major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

. After the war, he served in Congress from 1865 to 1867 as a Republican. Hayes left Congress to run for governor of Ohio and was elected to two consecutive terms, from 1868 to 1872. He served half of a third two-year term from 1876 to 1877 before his swearing-in as president.

In 1877, Hayes assumed the presidency following the

1876 United States presidential election

The 1876 United States presidential election was the 23rd quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 7, 1876, in which Republican nominee Rutherford B. Hayes faced Democrat Samuel J. Tilden. It was one of the most contentio ...

, one of the most contentious in U.S. history. Hayes lost the popular vote to Democrat

Samuel J. Tilden, and neither candidate secured enough electoral votes. According to the

U.S. Constitution, if no candidate wins the Electoral College, the

House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

is tasked with selecting the new president. Hayes secured a victory when a

Congressional Commission awarded him 20 contested electoral votes in the

Compromise of 1877

The Compromise of 1877, also known as the Wormley Agreement or the Bargain of 1877, was an unwritten deal, informally arranged among members of the United States Congress, to settle the intensely disputed 1876 presidential election between Ruth ...

. The electoral dispute was resolved with a backroom deal whereby the southern Democrats acquiesced to Hayes's election on the condition that he end both federal support for

Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

* Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

and the military occupation in the former

Confederate States

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

.

Hayes's administration was influenced by his belief in

meritocratic

Meritocracy (''merit'', from Latin , and ''-cracy'', from Ancient Greek 'strength, power') is the notion of a political system in which economic goods and/or political power are vested in individual people based on talent, effort, and ac ...

government and in equal treatment without regard to wealth, social standing, or race. One of the defining events of his presidency was the

Great Railroad Strike of 1877, which he resolved by calling in the

US Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

against the railroad workers. It remains the deadliest conflict between workers and strikebreakers in American history. As president, Hayes implemented modest civil-service reforms that laid the groundwork for further reform in the 1880s and 1890s. He vetoed the

Bland–Allison Act of 1878, which put silver money into circulation and raised nominal prices; Hayes saw the maintenance of the

gold standard

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from th ...

as essential to economic recovery. His policy toward western

Indians anticipated the assimilationist program of the

Dawes Act of 1887.

At the end of his term, Hayes kept his pledge not to run for reelection and retired to his home in Ohio. He became an advocate of social and educational reform. Biographer

Ari Hoogenboom has written that Hayes's greatest achievement was to restore popular faith in the presidency and to reverse the deterioration of executive power that had established itself after the

assassination of Abraham Lincoln

On April 14, 1865, Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president of the United States, was assassinated by well-known stage actor John Wilkes Booth, while attending the play '' Our American Cousin'' at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C.

Shot in the ...

in 1865. His supporters have praised his commitment to civil-service reform; his critics have derided his leniency toward former Confederate states as well as his withdrawal of federal support for

African Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

' voting and civil rights. Historians and scholars generally

rank

Rank is the relative position, value, worth, complexity, power, importance, authority, level, etc. of a person or object within a ranking, such as:

Level or position in a hierarchical organization

* Academic rank

* Diplomatic rank

* Hierarchy

* ...

Hayes as an average to below-average president.

Family and early life

Childhood and family history

Rutherford Birchard Hayes was born in

Delaware, Ohio, on October 4, 1822, to Rutherford Hayes, Jr. and Sophia Birchard. Hayes's father, a

Vermont

Vermont () is a U.S. state, state in the northeast New England region of the United States. Vermont is bordered by the states of Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, and New York (state), New York to the west, and the Provin ...

storekeeper, had taken the family to Ohio in 1817. He died ten weeks before Rutherford's birth. Sophia took charge of the family, raising Hayes and his sister, Fanny, the only two of the four children to survive to adulthood. She never remarried, and Sophia's younger brother, Sardis Birchard, lived with the family for a time. He was always close to Hayes and became a father figure to him, contributing to his early education.

Through each of his parents, Hayes was descended from

New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

colonists. His earliest immigrant ancestor came to

Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the ...

from

Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

in 1625. Hayes's great-grandfather Ezekiel Hayes was a militia captain in Connecticut in the

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, but Ezekiel's son (Hayes's grandfather, also named Rutherford) left his

Branford home during the war for the relative peace of Vermont. His mother's ancestors migrated to Vermont at a similar time. Hayes wrote: "I have always thought of myself as Scotch, but of the fathers of my family who came to America about thirty were English and two only, Hayes and Rutherford, were of Scotch descent. This, on my father's side. On my mother's side, the whole thirty-two were probably all of other peoples beside the Scotch." Most of his close relatives outside Ohio continued to live there.

John Noyes, an uncle by marriage, had been his father's business partner in Vermont and was later elected to Congress. His first cousin, Mary Jane Mead, was the mother of sculptor

Larkin Goldsmith Mead and architect

William Rutherford Mead.

John Humphrey Noyes, the founder of the

Oneida Community, was also a first cousin.

Education and early law career

Hayes attended the

common school A common school was a public school in the United States during the 19th century. Horace Mann (1796–1859) was a strong advocate for public education and the common school. In 1837, the state of Massachusetts appointed Mann as the first secretar ...

s in Delaware, Ohio, and enrolled in 1836 at the

Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's ...

Norwalk Seminary

Norwalk Seminary was a private, Methodist school in Norwalk, Ohio. Opening in 1838 with Edward Thomson as principal, by 1842 it had an attendance of nearly four hundred. Nonetheless, the school was unsuccessful financially, and it was forced to ...

in

Norwalk, Ohio. He did well at Norwalk, and the next year transferred to the Webb School, a

preparatory school in

Middletown, Connecticut, where he studied

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

and

Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic pe ...

. Returning to Ohio, he attended

Kenyon College

Kenyon College is a private liberal arts college in Gambier, Ohio. It was founded in 1824 by Philander Chase. Kenyon College is accredited by the Higher Learning Commission.

Kenyon has 1,708 undergraduates enrolled. Its 1,000-acre campus is s ...

in

Gambier in 1838. He enjoyed his time at Kenyon, and was successful scholastically; while there, he joined several student societies and became interested in

Whig politics. His classmates included

Stanley Matthews

Sir Stanley Matthews, CBE (1 February 1915 – 23 February 2000) was an English footballer who played as an outside right. Often regarded as one of the greatest players of the British game, he is the only player to have been knighted while sti ...

and

John Celivergos Zachos.

["Topping, Eva Catafygiotu"](_blank)

''John Zachos Cincinnatian from Constantinople'' The Cincinnati Historical Society Bulletin Volumes 33–34 Cincinnati Historical Society 1975: p. 51 He graduated

Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States, and the most prestigious, due in part to its long history and academic selectivity. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal ...

and with highest honors in 1842 and addressed the class as its

valedictorian

Valedictorian is an academic title for the highest-performing student of a graduating class of an academic institution.

The valedictorian is commonly determined by a numerical formula, generally an academic institution's grade point average (GPA) ...

.

After briefly

reading law

Reading law was the method used in common law countries, particularly the United States, for people to prepare for and enter the legal profession before the advent of law schools. It consisted of an extended internship or apprenticeship under th ...

in

Columbus

Columbus is a Latinized version of the Italian surname "''Colombo''". It most commonly refers to:

* Christopher Columbus (1451-1506), the Italian explorer

* Columbus, Ohio, capital of the U.S. state of Ohio

Columbus may also refer to:

Places ...

, Ohio, Hayes moved east to attend

Harvard Law School

Harvard Law School (Harvard Law or HLS) is the law school of Harvard University, a private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1817, it is the oldest continuously operating law school in the United States.

Each c ...

in 1843. Graduating with an

LL.B, he was

admitted to the Ohio bar in 1845 and opened his own law office in Lower Sandusky (now

Fremont). Business was slow at first, but he gradually attracted clients and also represented his uncle Sardis in real estate litigation. In 1847 Hayes became ill with what his doctor thought was

tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, ...

. Thinking a change in climate would help, he considered enlisting in the

Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the ...

, but on his doctor's advice instead visited family in New England. Returning from there, Hayes and his uncle Sardis made a long journey to

Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

, where Hayes visited with

Guy M. Bryan, a Kenyon classmate and distant relative. Business remained meager on his return to Lower Sandusky, and Hayes decided to move to

Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line w ...

.

Cincinnati law practice and marriage

Hayes moved to Cincinnati in 1850, and opened a law office with John W. Herron, a lawyer from

Chillicothe. Herron later joined a more established firm and Hayes formed a new partnership with William K. Rogers and Richard M. Corwine. He found business better in Cincinnati, and enjoyed its social attractions, joining the

Cincinnati Literary Society and the

Odd Fellows Club. He also attended the

Episcopal Church in Cincinnati but did not become a member.

Hayes courted his future wife,

Lucy Webb, during his time there. His mother had encouraged him to get to know Lucy years earlier, but Hayes had believed she was too young and focused his attention on other women. Four years later, Hayes began to spend more time with Lucy. They became engaged in 1851 and married on December 30, 1852, at Lucy's mother's house. Over the next five years, Lucy gave birth to three sons: Birchard Austin (1853),

Webb Cook (1856), and

Rutherford Platt (1858). A

Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's ...

, Lucy was a

teetotaler

Teetotalism is the practice or promotion of total personal abstinence from the psychoactive drug alcohol, specifically in alcoholic drinks. A person who practices (and possibly advocates) teetotalism is called a teetotaler or teetotaller, or is ...

and

abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

. She influenced her husband's views on those issues, though he never formally joined her church.

Hayes had begun his law practice dealing primarily with commercial issues but won greater prominence in Cincinnati as a criminal defense attorney, defending several people accused of murder. In one case, he used a form of the

insanity defense

The insanity defense, also known as the mental disorder defense, is an affirmative defense by excuse in a criminal case, arguing that the defendant is not responsible for their actions due to an episodic psychiatric disease at the time of the ...

that saved the accused from the gallows; she was instead confined to a mental institution. Hayes also defended slaves who had escaped and been accused under the

Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

The Fugitive Slave Act or Fugitive Slave Law was passed by the United States Congress on September 18, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850 between Southern interests in slavery and Northern Free-Soilers.

The Act was one of the most con ...

. As Cincinnati was just across the

Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of ...

from

Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia ...

, a slave state, it was a destination for escaping slaves and many such cases were tried in its courts. A staunch abolitionist, Hayes found his work on behalf of fugitive slaves personally gratifying as well as politically useful, as it raised his profile in the newly formed

Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

* Republican Party (Liberia)

*Republican Party ...

.

His political reputation rose with his professional plaudits. Hayes declined a Republican nomination for a judgeship in 1856. Two years later, some Republicans proposed Hayes to fill a vacancy on the bench and he considered accepting the appointment until the office of

city solicitor also became vacant. The city council elected Hayes city solicitor to fill the vacancy, and voters elected him to a full two-year term in April 1859 with a larger majority than other Republicans on the ticket.

Civil War

West Virginia and South Mountain

As the Southern states quickly began to secede after

Lincoln's election to the presidency in 1860, Hayes was lukewarm about

civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

to restore the Union. Considering that the two sides might be irreconcilable, he suggested that the Union "

t them go." Though Ohio had voted for Lincoln in 1860, Cincinnati voters turned against the Republican party after secession. Its residents included many from the

Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

, and they voted for the Democrats and

Know-Nothing

The Know Nothing party was a nativist political party and movement in the United States in the mid-1850s. The party was officially known as the "Native American Party" prior to 1855 and thereafter, it was simply known as the "American Party". ...

s, who combined to sweep the city elections in April 1861, ejecting Hayes from the city solicitor's office.

Returning to private practice, Hayes formed a very brief law partnership with

Leopold Markbreit, lasting three days before the war began. After the

Confederates fired on Fort Sumter, Hayes resolved his doubts and joined a volunteer company composed of his Literary Society friends. That June, Governor

William Dennison appointed several of the officers of the volunteer company to positions in the

23rd Regiment of Ohio Volunteer Infantry. Hayes was promoted to

major

Major ( commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicato ...

, and his friend and college classmate

Stanley Matthews

Sir Stanley Matthews, CBE (1 February 1915 – 23 February 2000) was an English footballer who played as an outside right. Often regarded as one of the greatest players of the British game, he is the only player to have been knighted while sti ...

was appointed

lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colon ...

. Joining the regiment as a

private

Private or privates may refer to:

Music

* " In Private", by Dusty Springfield from the 1990 album ''Reputation''

* Private (band), a Denmark-based band

* "Private" (Ryōko Hirosue song), from the 1999 album ''Private'', written and also recorde ...

was another future president,

William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in t ...

.

After a month of training, Hayes and the 23rd Ohio set out for western Virginia in July 1861 as a part of the

Kanawha Division

The Kanawha Division was a Union Army division which could trace its origins back to a brigade originally commanded by Jacob D. Cox. This division served in western Virginia and Maryland and was at times led by such famous personalities as George ...

. They did not meet the enemy until September, when the regiment encountered Confederates at

Carnifex Ferry in present-day

West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the ...

and drove them back. In November, Hayes was promoted to lieutenant colonel (Matthews having been promoted to colonel of another regiment) and led his troops deeper into western Virginia, where they entered winter quarters. The division resumed its advance the following spring, and Hayes led several raids against the rebel forces, on one of which he sustained a minor injury to his knee. That September, Hayes's regiment was called east to reinforce General

John Pope's

Army of Virginia at the

Second Battle of Bull Run

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Battle of Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, in Prince William County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of the Northern Virginia Campaign waged by Confedera ...

. Hayes and his troops did not arrive in time for the battle, but joined the

Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confede ...

as it hurried north to cut off

Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, towards the end of which he was appointed the overall commander of the Confederate States Army. He led the Army of Nor ...

's

Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the primary military force of the Confederate States of America in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most oft ...

, which was advancing into

Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean t ...

. Marching north, the 23rd was the lead regiment encountering the Confederates at the

Battle of South Mountain

The Battle of South Mountain—known in several early Southern accounts as the Battle of Boonsboro Gap—was fought on September 14, 1862, as part of the Maryland campaign of the American Civil War. Three pitched battles were fought for posses ...

on September 14. Hayes led a charge against an entrenched position and was shot through his left arm, fracturing the bone. He had one of his men tie a handkerchief above the wound in an effort to stop the bleeding, and continued to lead his men in the battle. While resting, he ordered his men to meet a flanking attack, but instead his entire command moved backward, leaving Hayes lying in between the lines.

Eventually, his men brought Hayes back behind their lines, and he was taken to hospital. The regiment continued on to

Antietam

The Battle of Antietam (), or Battle of Sharpsburg particularly in the Southern United States, was a battle of the American Civil War fought on September 17, 1862, between Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union G ...

, but Hayes was out of action for the rest of the campaign. In October, he was promoted to

colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge ...

and assigned to command of the first brigade of the Kanawha Division as a

brevet brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointe ...

.

Army of the Shenandoah

The division spent the following winter and spring near

Charleston, Virginia (present-day West Virginia), out of contact with the enemy. Hayes saw little action until July 1863, when the division skirmished with

John Hunt Morgan's cavalry at the

Battle of Buffington Island. Returning to Charleston for the rest of the summer, Hayes spent the fall encouraging the men of the 23rd Ohio to reenlist, and many did. In 1864, the Army command structure in West Virginia was reorganized, and Hayes's division was assigned to

George Crook

George R. Crook (September 8, 1828 – March 21, 1890) was a career United States Army officer, most noted for his distinguished service during the American Civil War and the Indian Wars. During the 1880s, the Apache nicknamed Crook ''Nanta ...

's

Army of West Virginia. Advancing into southwestern Virginia, they destroyed Confederate salt and lead mines there. On May 9, they engaged Confederate troops at

Cloyd's Mountain, where Hayes and his men charged the enemy entrenchments and drove the rebels from the field. Following the rout, the Union forces destroyed Confederate supplies and again successfully skirmished with the enemy.

Hayes and his brigade moved to the

Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley () is a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia. The valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the eastern front of the Ridg ...

for the

Valley Campaigns of 1864. Crook's corps was attached to Major General

David Hunter

David Hunter (July 21, 1802 – February 2, 1886) was an American military officer. He served as a Union general during the American Civil War. He achieved notability for his unauthorized 1862 order (immediately rescinded) emancipating slaves ...

's

Army of the Shenandoah and soon back in contact with Confederate forces, capturing

Lexington, Virginia

Lexington is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia. At the 2020 census, the population was 7,320. It is the county seat of Rockbridge County, although the two are separate jurisdictions. The Bureau of Economic Analysis combines ...

on June 11. They continued south toward

Lynchburg, tearing up railroad track as they advanced, but Hunter believed the troops at Lynchburg were too powerful, and Hayes and his brigade returned to West Virginia. Hayes thought Hunter lacked aggression, writing in a letter home that "General Crook would have taken Lynchburg." Before the army could make another attempt, Confederate General

Jubal Early's raid into Maryland forced their recall to the north. Early's army surprised them at

Kernstown on July 24, where Hayes was slightly wounded by a bullet to the shoulder. He also had a horse shot out from under him, and the army was defeated. Retreating to Maryland, the army was reorganized again, with Major General

Philip Sheridan

General of the Army Philip Henry Sheridan (March 6, 1831 – August 5, 1888) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the American Civil War. His career was noted for his rapid rise to major general and his close a ...

replacing Hunter. By August, Early was retreating up the valley, with Sheridan in pursuit. Hayes's troops fended off a Confederate assault at

Berryville and advanced to

Opequon Creek, where they broke the enemy lines and pursued them farther south. They followed up the victory with another at

Fisher's Hill on September 22, and one more at

Cedar Creek on October 19. At Cedar Creek, Hayes sprained his ankle after being thrown from a horse and was struck in the head by a spent round, which did not cause serious damage. His leadership and bravery drew his superiors' attention, with

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

later writing of Hayes, "

s conduct on the field was marked by conspicuous gallantry as well as the display of qualities of a higher order than that of mere personal daring."

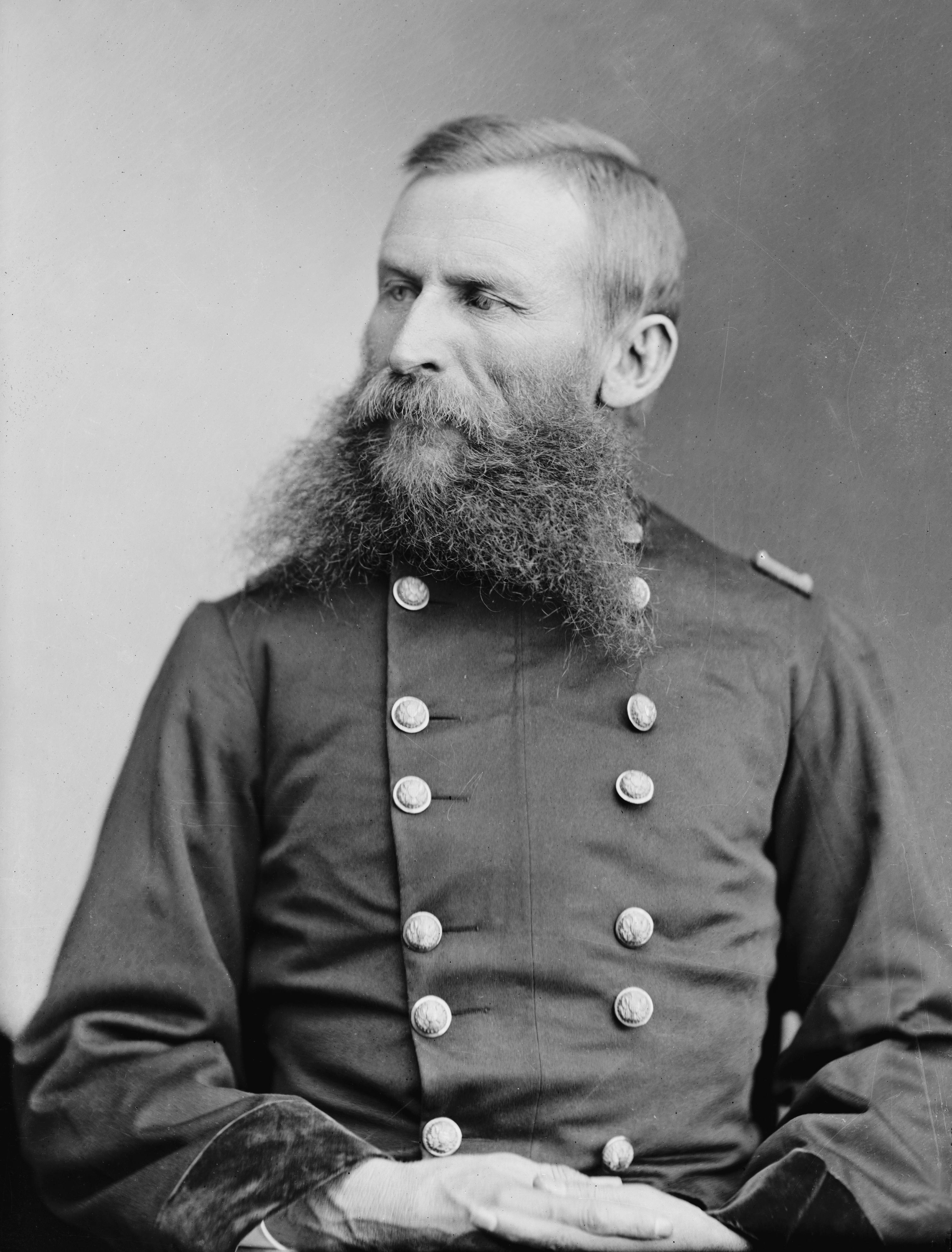

Cedar Creek marked the end of the campaign. Hayes was promoted to

brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointe ...

in October 1864 and brevetted

major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

. Around this time, Hayes learned of the birth of his fourth son, George Crook Hayes. The army went into winter quarters once more, and in spring 1865 the war quickly came to a close with Lee's surrender to Grant at Appomattox. Hayes visited

Washington, D.C. that May and observed the

Grand Review of the Armies

The Grand Review of the Armies was a military procession and celebration in the national capital city of Washington, D.C., on May 23–24, 1865, following the Union victory in the American Civil War (1861–1865). Elements of the Union Army in t ...

, after which he and the 23rd Ohio returned to their home state to be mustered out of the service.

Post-war politics

U.S. Representative from Ohio

While serving in the

Army of the Shenandoah in 1864, Hayes was nominated by Republicans for the

House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

from

Ohio's 2nd congressional district

Ohio's 2nd congressional district is a district in southern Ohio. It is currently represented by Republican Brad Wenstrup.

The district includes all of Adams, Brown, Pike, Clermont, Highland, Clinton, Ross, Pickaway, Hocking, Vinton, ...

. Asked by friends in Cincinnati to leave the army to campaign, he refused, saying that an "officer fit for duty who at this crisis would abandon his post to electioneer for a seat in Congress ought to be scalped." Instead, Hayes wrote several letters to the voters explaining his political positions and was elected by a 2,400-vote majority over the incumbent, Democrat

Alexander Long

Alexander Long (December 24, 1816 – November 28, 1886) was a Democratic United States Congressman who served in Congress from March 4, 1863, to March 3, 1865. During the Civil War, Long was a prominent "Copperhead", a member of the peace move ...

.

When the

39th Congress

The 39th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1865 ...

assembled in December 1865, Hayes was sworn in as a part of a large Republican majority. Hayes identified with the party's

moderate

Moderate is an ideological category which designates a rejection of radical or extreme views, especially in regard to politics and religion. A moderate is considered someone occupying any mainstream position avoiding extreme views. In American ...

wing, but was willing to vote with the

radicals

Radical may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change

*Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and ...

for the sake of party unity. The major legislative effort of the Congress was the

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fourteenth Amendment (Amendment XIV) to the United States Constitution was adopted on July 9, 1868, as one of the Reconstruction Amendments. Often considered as one of the most consequential amendments, it addresses citizenship rights and ...

, for which Hayes voted and which passed both houses of Congress in June 1866. Hayes's beliefs were in line with his fellow Republicans on

Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

* Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

issues: that the South should be restored to the Union, but not without adequate protections for

freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), emancipation (granted freedom ...

and other black southerners. President

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a De ...

, who succeeded to office following Lincoln's assassination, to the contrary wanted to readmit the seceded states quickly without first ensuring that they adopted laws protecting the newly freed slaves' civil rights; he also granted pardons to many of the leading former Confederates. Hayes, along with congressional Republicans, disagreed. They worked to reject Johnson's vision of Reconstruction and to pass the

Civil Rights Act of 1866

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 (, enacted April 9, 1866, reenacted 1870) was the first United States federal law to define citizenship and affirm that all citizens are equally protected by the law. It was mainly intended, in the wake of the Ame ...

.

Reelected in 1866, Hayes returned to the

lame-duck session. On January 7, 1867, he voted for the resolution that authorized the

first impeachment inquiry against Andrew Johnson

The first impeachment inquiry against Andrew Johnson was launched by a vote of the United States House of Representatives on January 7, 1867 to investigate the potential impeachment of Andrew Johnson, the president of the United States. It was ...

. He also voted during this time for the

Tenure of Office Act, which ensured that Johnson could not remove administration officials without the Senate's consent, and unsuccessfully pressed for a

civil service reform bill that attracted the votes of many reform-minded Republicans. Hayes continued to vote with the majority in the

40th Congress on the

Reconstruction Acts, but resigned in July 1867 to run for governor of Ohio.

Governor of Ohio

A popular Congressman and former Army officer, Hayes was considered by Ohio Republicans to be an excellent standard-bearer for the 1867 election campaign. His political views were more moderate than the Republican party's platform, although he agreed with the proposed amendment to the Ohio state constitution that would guarantee

suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

to black male Ohioans. Hayes's opponent,

Allen G. Thurman, made the proposed amendment the centerpiece of the campaign and opposed

black suffrage

Black suffrage refers to black people's right to vote and has long been an issue in countries established under conditions of black minorities.

United States

Suffrage in the United States has had many advances and setbacks. Prior to the Civil ...

. Both men campaigned vigorously, making speeches across the state, mostly focusing on the suffrage question. The election was mostly a disappointment to Republicans, as the amendment failed to pass and Democrats gained a majority in the

state legislature

A state legislature is a legislative branch or body of a political subdivision in a federal system.

Two federations literally use the term "state legislature":

* The legislative branches of each of the fifty state governments of the United Sta ...

. Hayes thought at first that he, too, had lost, but the final tally showed that he had won the election by 2,983 votes of 484,603 votes cast.

As a Republican governor with a Democratic legislature, Hayes had a limited role in governing, especially since

Ohio's governor had no

veto

A veto is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a president or monarch vetoes a bill to stop it from becoming law. In many countries, veto powers are established in the country's constitution. Veto ...

power. Despite these constraints, he oversaw the establishment of a school for deaf-mutes and a

reform school

A reform school was a penal institution, generally for teenagers mainly operating between 1830 and 1900.

In the United Kingdom and its colonies reformatories commonly called reform schools were set up from 1854 onwards for youngsters who wer ...

for girls. He endorsed the

impeachment of President Andrew Johnson and urged his conviction, which failed by one vote in the United States Senate. Nominated for a second term in 1869, Hayes campaigned again for equal rights for black Ohioans and sought to associate his Democratic opponent,

George H. Pendleton, with disunion and Confederate sympathies. Hayes was reelected with an increased majority, and the Republicans took the legislature, ensuring Ohio's ratification of the

Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fifteenth Amendment (Amendment XV) to the United States Constitution prohibits the federal government and each state from denying or abridging a citizen's right to vote "on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude." It was ...

, which guaranteed black (male) suffrage. With a Republican legislature, Hayes's second term was more enjoyable. Suffrage was expanded and a state Agricultural and Mechanical College (later to become The

Ohio State University

The Ohio State University, commonly called Ohio State or OSU, is a public land-grant research university in Columbus, Ohio. A member of the University System of Ohio, it has been ranked by major institutional rankings among the best pub ...

) established. He also proposed a reduction in state taxes and reform of the state prison system. Choosing not to seek reelection, Hayes looked forward to retiring from politics in 1872.

Private life and return to politics

As Hayes prepared to leave office, several delegations of reform-minded Republicans urged him to run for

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and po ...

against the incumbent Republican,

John Sherman

John Sherman (May 10, 1823October 22, 1900) was an American politician from Ohio throughout the Civil War and into the late nineteenth century. A member of the Republican Party, he served in both houses of the U.S. Congress. He also served as ...

. Hayes declined, preferring to preserve party unity and retire to private life. He especially looked forward to spending time with his children, two of whom (daughter Fanny and son Scott) had been born in the past five years. Initially, Hayes tried to promote railway extensions to his hometown, Fremont. He also managed some real estate he had acquired in

Duluth, Minnesota

, settlement_type = City

, nicknames = Twin Ports (with Superior, Wisconsin, Superior), Zenith City

, motto =

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top: Downtown Dul ...

. Not entirely removed from politics, Hayes held out some hope of a

cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filin ...

appointment, but was disappointed to receive only an appointment as assistant U.S. treasurer at Cincinnati, which he turned down. He agreed to be nominated for his old House seat in 1872 but was not disappointed when he lost the election to

Henry B. Banning, a fellow

Kenyon College

Kenyon College is a private liberal arts college in Gambier, Ohio. It was founded in 1824 by Philander Chase. Kenyon College is accredited by the Higher Learning Commission.

Kenyon has 1,708 undergraduates enrolled. Its 1,000-acre campus is s ...

alumnus.

In 1873, Lucy gave birth to another son, Manning Force Hayes. That same year, the

Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the ...

hurt business prospects across the nation, including Hayes's. His uncle Sardis Birchard died that year, and the Hayes family moved into

Spiegel Grove, the grand house Birchard had built with them in mind. That year Hayes announced his uncle's bequest of $50,000 in assets to endow a public library for Fremont, to be called the Birchard Library. It opened in 1874 on Front Street, and a new building was completed and opened in 1878 in Fort Stephenson State Park. (This site was per the terms of the bequest.) Hayes served as chairman of the library's board of trustees until his death.

Hayes hoped to stay out of politics in order to pay off the debts he had incurred during the Panic, but when the Republican state convention nominated him for governor in 1875, he accepted. His campaign against Democratic nominee

William Allen focused primarily on Protestant fears about the possibility of

state aid to Catholic schools. Hayes was against such funding and, while not known to be personally

anti-Catholic, he allowed anti-Catholic fervor to contribute to the enthusiasm for his candidacy. The campaign was a success, and on October 12, 1875 Hayes was returned to the governorship by a 5,544-vote majority. The first person to earn a third term as governor of Ohio, Hayes reduced the state debt, reestablished the Board of Charities, and repealed the Geghan Bill, which had allowed for the appointment of Catholic priests to schools and penitentiaries.

Election of 1876

Republican nomination and campaign against Tilden

Hayes's success in Ohio immediately elevated him to the top ranks of Republican politicians under consideration for the presidency in 1876. The Ohio delegation to the

1876 Republican National Convention

The 1876 Republican National Convention was a presidential nominating convention held at the Exposition Hall in Cincinnati, Ohio on June 14–16, 1876. President Ulysses S. Grant had considered seeking a third term, but with various scandals, a ...

was united behind him, and Senator

John Sherman

John Sherman (May 10, 1823October 22, 1900) was an American politician from Ohio throughout the Civil War and into the late nineteenth century. A member of the Republican Party, he served in both houses of the U.S. Congress. He also served as ...

did all in his power to get Hayes the nomination. In June 1876, the convention assembled with

James G. Blaine

James Gillespie Blaine (January 31, 1830January 27, 1893) was an American statesman and Republican politician who represented Maine in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1863 to 1876, serving as Speaker of the U.S. House of Representati ...

of

Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and nor ...

as the favorite. Blaine started with a significant lead in the delegate count, but could not muster a majority. As he failed to gain votes, the delegates looked elsewhere for a nominee and settled on Hayes on the seventh ballot. The convention selected Representative

William A. Wheeler

William Almon Wheeler (June 30, 1819June 4, 1887) was an American politician and attorney. He served as a United States representative from New York from 1861 to 1863 and 1869 to 1877, and the 19th vice president of the United States from 1877 t ...

from

New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

for vice president, a man about whom Hayes had recently asked, "I am ashamed to say: who is Wheeler?"

The campaign strategy of Hayes and Wheeler emphasized conciliatory appeals to the Southern Whiggish element, attempting to "detach" old Southern Whigs from Southern Democrats. When

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

asked whether the Republican Party would continue its devotion to protecting black civil rights or "get along without the vote of the black man in the South", Hayes and Wheeler advocated the latter.

The Democratic nominee was

Samuel J. Tilden, the governor of New York. Tilden was considered a formidable adversary who, like Hayes, had a reputation for honesty. Also like Hayes, Tilden was a

hard-money man and supported civil service reform. In accordance with the custom of the time, the campaign was conducted by surrogates, with Hayes and Tilden remaining in their respective hometowns. The poor economic conditions made the party in power unpopular and made Hayes suspect he would lose the election. Both candidates concentrated on the swing states of

New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

and

Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th ...

, as well as the three southern states—

Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is bord ...

,

South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

, and

Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and ...

—where

Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

* Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

Republican governments still barely ruled, amid recurring political violence, including widespread efforts to suppress

freedman

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), emancipation (granted freedom ...

voting. The Republicans emphasized the danger of letting Democrats run the nation so soon after southern Democrats had provoked the Civil War and, to a lesser extent, the danger a Democratic administration would pose to the recently won civil rights of southern blacks. Democrats, for their part, trumpeted Tilden's record of reform and contrasted it with the

corruption of the incumbent Grant administration.

As the returns were tallied on election day, it was clear that the race was close: Democrats had carried most of the South, as well as New York, Indiana,

Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the ...

, and

New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delawa ...

. In the

Northeastern United States

The Northeastern United States, also referred to as the Northeast, the East Coast, or the American Northeast, is a geographic region of the United States. It is located on the Atlantic coast of North America, with Canada to its north, the Southe ...

, an increasing number of immigrants and their descendants voted Democratic. Although Tilden won the popular vote and claimed 184 electoral votes, Republican leaders challenged the results and charged Democrats with fraud and voter suppression of blacks (who would otherwise have voted Republican) in Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina. Republicans realized that if they held the three disputed

unredeemed southern states together with some of the western states, they would emerge with an

electoral college majority.

Disputed electoral votes

On November 11, three days after election day, Tilden appeared to have won 184 electoral votes, one short of a majority. Hayes appeared to have 166, with the 19 votes of Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina still in doubt. Republicans and Democrats each claimed victory in the three latter states, but the results in those states were rendered uncertain because of fraud by both parties. To further complicate matters, one of the three electors from

Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

(a state Hayes had won) was disqualified, reducing Hayes's total to 165, and raising the disputed votes to 20. If Hayes was not awarded all 20 disputed votes, Tilden would be elected president.

There was considerable debate about which person or house of Congress was authorized to decide between the competing slates of electors, with the Republican Senate and the Democratic House each claiming priority. By January 1877, with the question still unresolved, Congress and President

Grant agreed to submit the matter to a bipartisan

Electoral Commission, which would be authorized to determine the fate of the disputed electoral votes. The Commission was to be made up of five

representatives, five

senators, and five

Supreme Court justices. To ensure partisan balance, there would be seven Democrats and seven Republicans, with Justice

David Davis, an independent respected by both parties, as the 15th member. The balance was upset when Democrats in the

Illinois legislature

The Illinois General Assembly is the state legislature (United States), legislature of the U.S. state of Illinois. It has Bicameralism, two chambers, the Illinois House of Representatives and the Illinois Senate. The General Assembly was created ...

elected Davis to the Senate, hoping to sway his vote. Davis disappointed Democrats by refusing to serve on the Commission because of his election to the Senate. As all the remaining Justices were Republicans, Justice

Joseph P. Bradley, believed to be the most independent-minded of them, was selected to take Davis's place on the Commission. The Commission met in February and the eight Republicans voted to award all 20 electoral votes to Hayes. Democrats, outraged by the result, attempted a

filibuster

A filibuster is a political procedure in which one or more members of a legislative body prolong debate on proposed legislation so as to delay or entirely prevent decision. It is sometimes referred to as "talking a bill to death" or "talking out ...

to prevent Congress from accepting the Commission's findings. Eventually, the filibusterers gave up, allowing the House to reject the objection in the early hours of March 2. The House and Senate then reassembled to complete the count of the electoral votes. At 4:10 am on March 2,

Senator Thomas Ferry announced that Hayes and Wheeler had been elected to the presidency and vice presidency, by an electoral margin of 185–184.

As inauguration day neared, Republican and Democratic Congressional leaders met at

Wormley's Hotel in Washington to negotiate a

compromise

To compromise is to make a deal between different parties where each party gives up part of their demand. In arguments, compromise is a concept of finding agreement through communication, through a mutual acceptance of terms—often involving va ...

. Republicans promised concessions in exchange for Democratic acquiescence to the Committee's decision. The main concession Hayes promised was the withdrawal of federal troops from the South and an acceptance of the election of Democratic governments in the remaining "unredeemed" southern states. The Democrats agreed, and on March 2, the filibuster was ended. Hayes was elected, but Reconstruction was finished, and freedmen were left at the mercy of white Democrats who did not intend to preserve their rights. On April 3, Hayes ordered Secretary of War

George W. McCrary

George Washington McCrary (August 29, 1835 – June 23, 1890) was a United States representative from Iowa, the 33rd United States Secretary of War and a United States circuit judge of the United States Circuit Courts for the Eighth Circuit.

Ed ...

to withdraw federal troops stationed at the

South Carolina State House

The South Carolina State House is the building housing the government of the U.S. state of South Carolina, which includes the South Carolina General Assembly and the offices of the Governor and Lieutenant Governor of South Carolina. Located in th ...

to their barracks. On April 20, he ordered McCrary to send the federal troops stationed at

's St. Louis Hotel to

Jackson Barracks

Jackson Barracks is the headquarters of the Louisiana National Guard. It is located in the Lower 9th Ward of New Orleans, Louisiana. The base was established in 1834 and was originally known as New Orleans Barracks. On July 7, 1866, it was ren ...

.

Presidency (1877–1881)

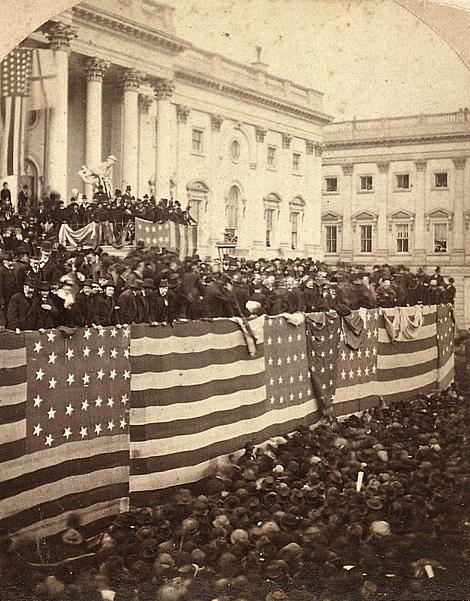

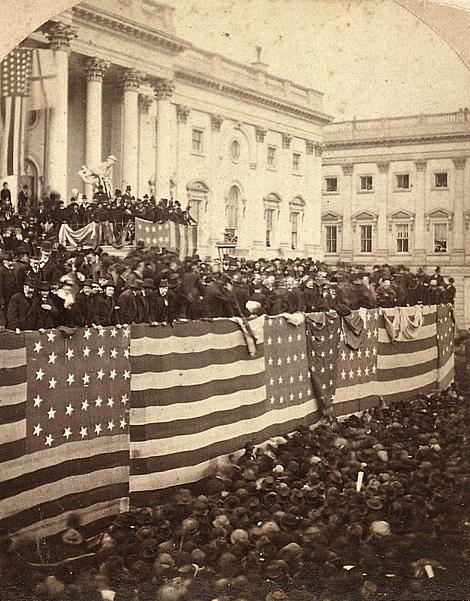

Inauguration

Because March 4, 1877, was a Sunday, Hayes took the oath of office privately on Saturday, March 3, in the

Red Room of the

White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in ...

, the first president to do so in the Executive Mansion. He took the oath publicly on March 5 on the East Portico of the

United States Capitol

The United States Capitol, often called The Capitol or the Capitol Building, is the seat of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, which is formally known as the United States Congress. It is located on Capitol Hill ...

. In his inaugural address, Hayes attempted to soothe the passions of the past few months, saying that "he serves his party best who serves his country best". He pledged to support "wise, honest, and peaceful local self-government" in the South, as well as reform of the

civil service

The civil service is a collective term for a sector of government composed mainly of career civil servants hired on professional merit rather than appointed or elected, whose institutional tenure typically survives transitions of political leaders ...

and a full return to the

gold standard

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from th ...

. Despite his message of conciliation, many Democrats never considered Hayes's election legitimate and referred to him as "Rutherfraud" or "His Fraudulency" for the next four years.

The South and the end of Reconstruction

Hayes had firmly supported Republican

Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

* Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

policies throughout his career, but the first major act of his presidency was an end to Reconstruction and the return of the South to "home rule". Even without the conditions of the Wormley's Hotel agreement, Hayes would have been hard-pressed to continue his predecessors' policies. The House of Representatives in the

45th Congress

The 45th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1877, ...

was controlled by a majority of Democrats, and they refused to appropriate enough funds for the army to continue to garrison the South. Even among Republicans, devotion to continued military Reconstruction was fading in the face of persistent Southern insurgency and violence. Only two states were still under Reconstruction's sway when Hayes assumed the presidency and, without troops to enforce the voting rights laws, these soon fell to Democratic control.

Hayes's later attempts to protect the rights of southern blacks were ineffective, as were his attempts to rebuild Republican strength in the South. He did, however, defeat Congress's efforts to curtail federal power to monitor federal elections. Democrats in Congress passed an army

appropriation bill

An appropriation, also known as supply bill or spending bill, is a proposed law that authorizes the expenditure of government funds. It is a bill that sets money aside for specific spending. In some democracies, approval of the legislature is ne ...

in 1879 with a

rider that repealed the

Enforcement Acts

The Enforcement Acts were three bills that were passed by the United States Congress between 1870 and 1871. They were criminal codes that protected African Americans’ right to vote, to hold office, to serve on juries, and receive equal protect ...

, which had been used to suppress the

Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Cat ...

. Chapters had flourished across the South and it had been one of the insurgent groups that attacked and suppressed freedmen. Those Acts, passed during Reconstruction, made it a crime to prevent someone from voting because of his race. Other paramilitary groups, such as the

Red Shirts in the Carolinas, however, had intimidated freedmen and suppressed the vote. Hayes was determined to preserve the law protecting black voters, and vetoed the appropriation.

The Democrats did not have enough votes to override the veto, but they passed a new bill with the same rider. Hayes vetoed that bill too, and the process was repeated three times more. Finally, Hayes signed an appropriation without the offensive rider, but Congress refused to pass another bill to fund federal marshals, who were vital to the enforcement of the Enforcement Acts. The election laws remained in effect, but the funds to enforce them were curtailed for the time being.

Hayes tried to reconcile the social

mores

Mores (, sometimes ; , plural form of singular , meaning "manner, custom, usage, or habit") are social norms that are widely observed within a particular society or culture. Mores determine what is considered morally acceptable or unacceptable ...

of the South with the recently passed civil rights laws by distributing patronage among southern Democrats. "My task was to wipe out the color line, to abolish sectionalism, to end the war and bring peace," he wrote in his diary. "To do this, I was ready to resort to unusual measures and to risk my own standing and reputation within my party and the country." All his efforts were in vain; Hayes failed to persuade the South to accept legal racial equality or to convince Congress to appropriate funds to enforce the

civil rights laws.

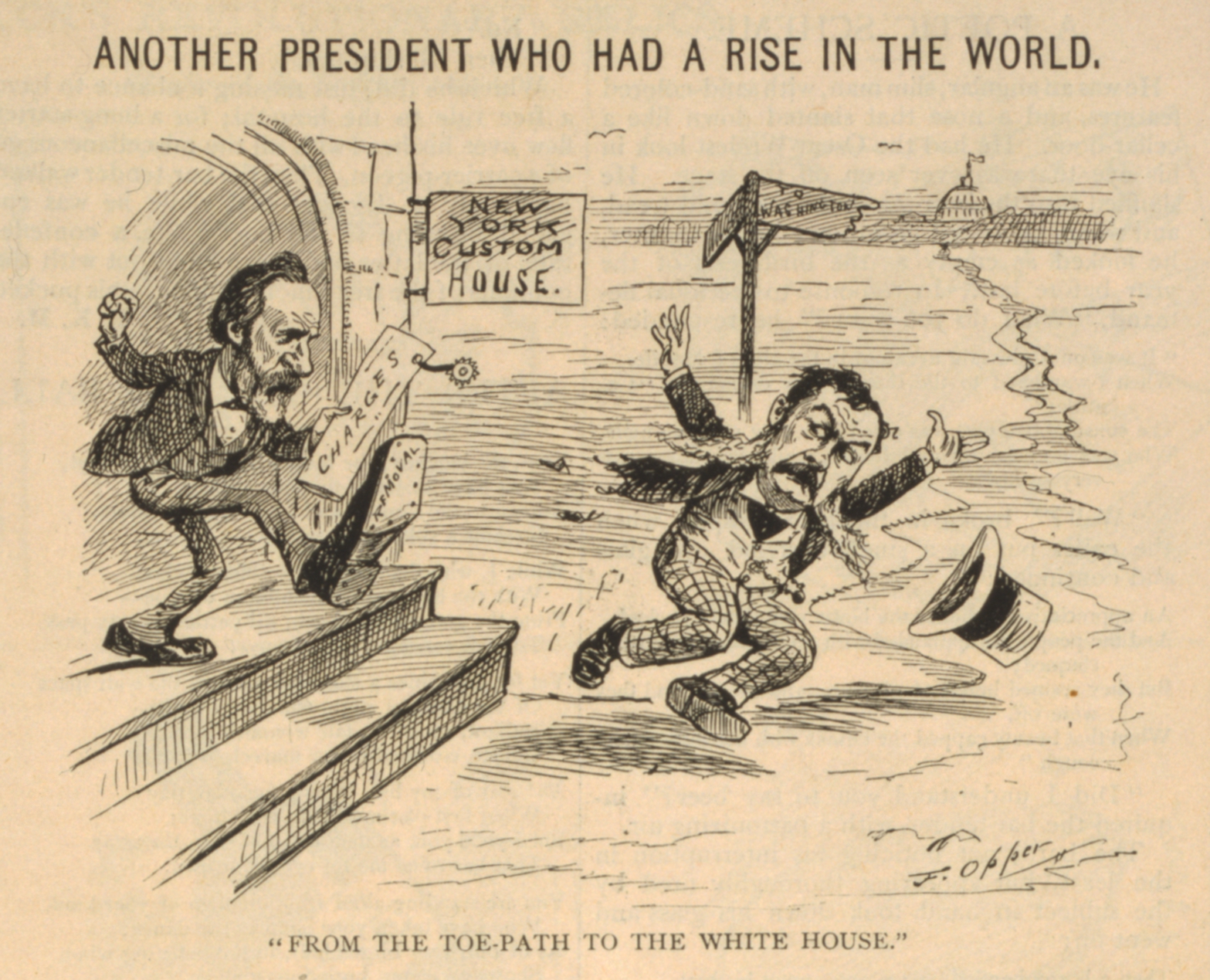

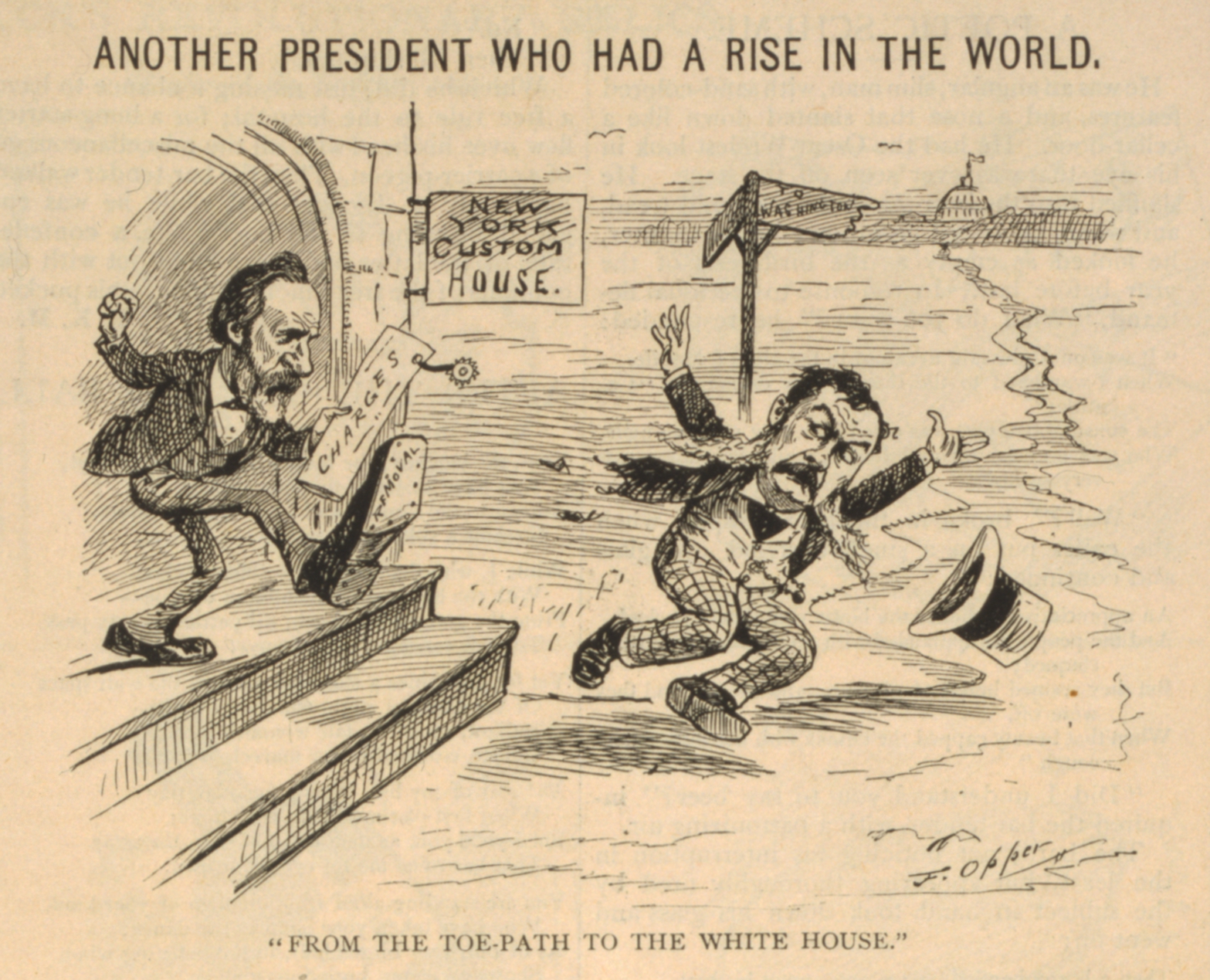

Civil service reform

Hayes took office determined to reform the system of civil service appointments, which had been based on the

spoils system since

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

's presidency. Instead of giving federal jobs to political supporters, Hayes wished to award them by merit according to an

examination that all applicants would take. Hayes's call for reform immediately brought him into conflict with the

Stalwart, or pro-spoils, branch of the Republican party. Senators of both parties were accustomed to being consulted about political appointments and turned against Hayes. Foremost among his enemies was New York Senator

Roscoe Conkling

Roscoe Conkling (October 30, 1829April 18, 1888) was an American lawyer and Republican politician who represented New York in the United States House of Representatives and the United States Senate. He is remembered today as the leader of the ...

, who fought Hayes's reform efforts at every turn.

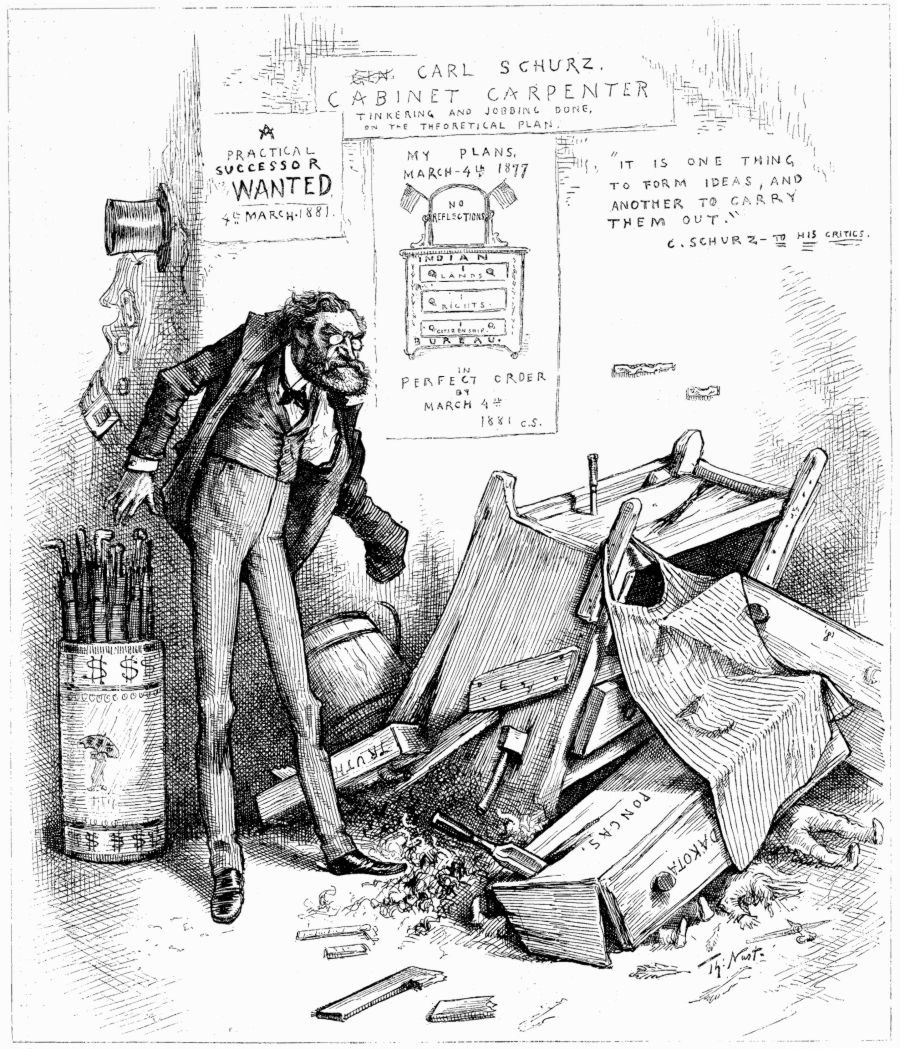

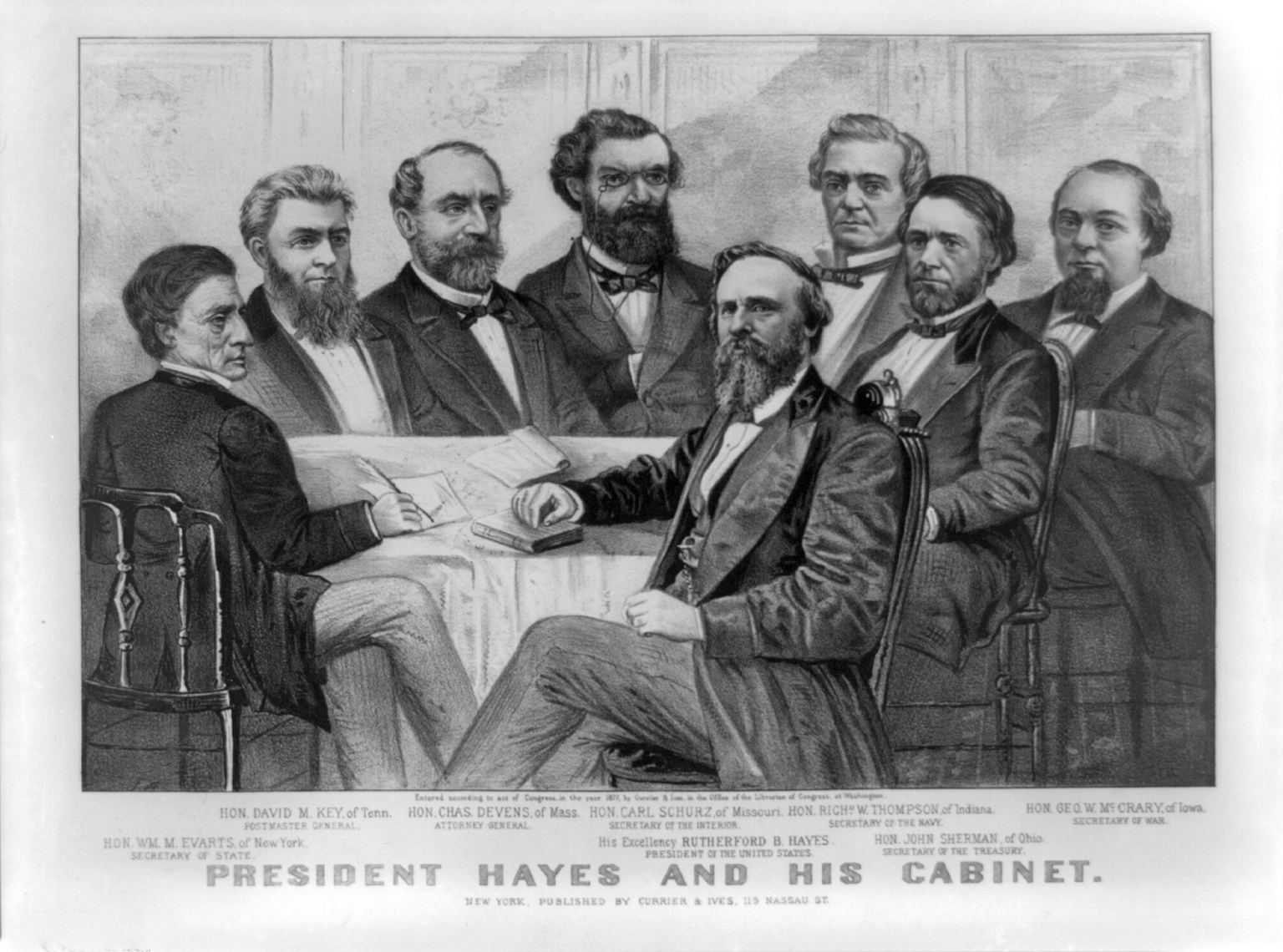

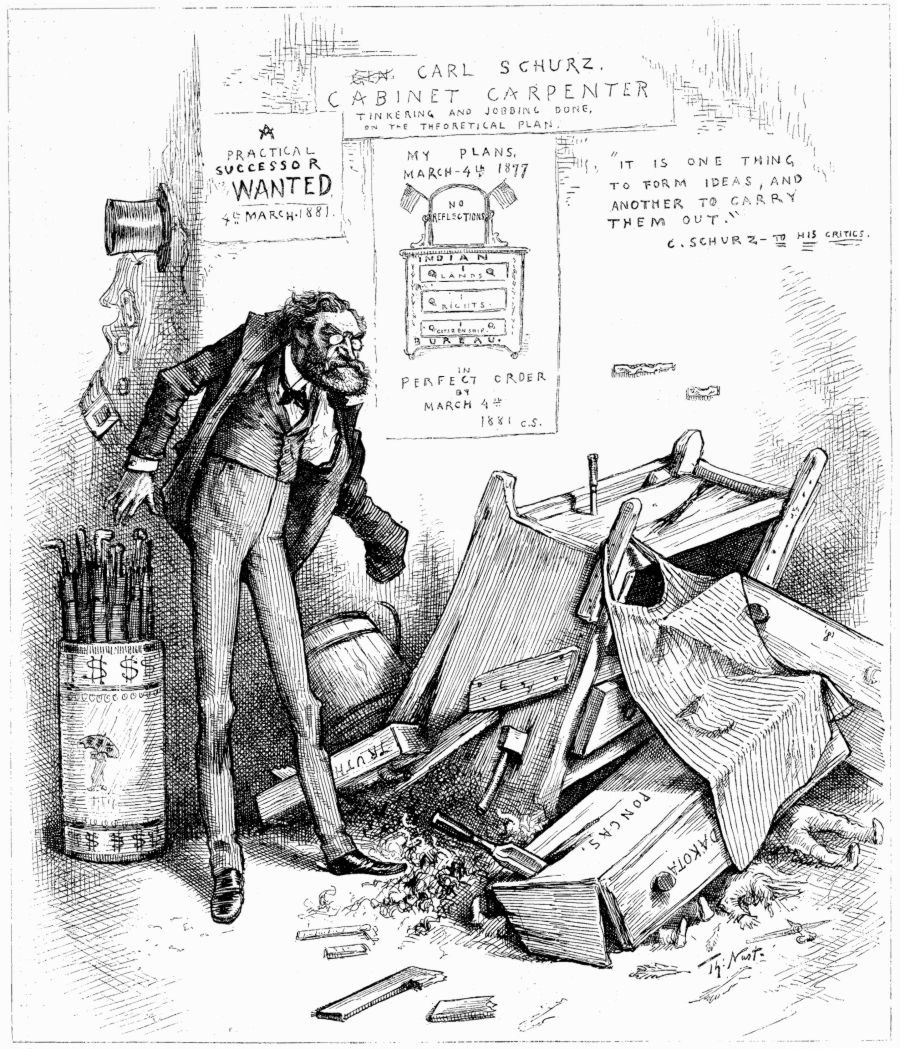

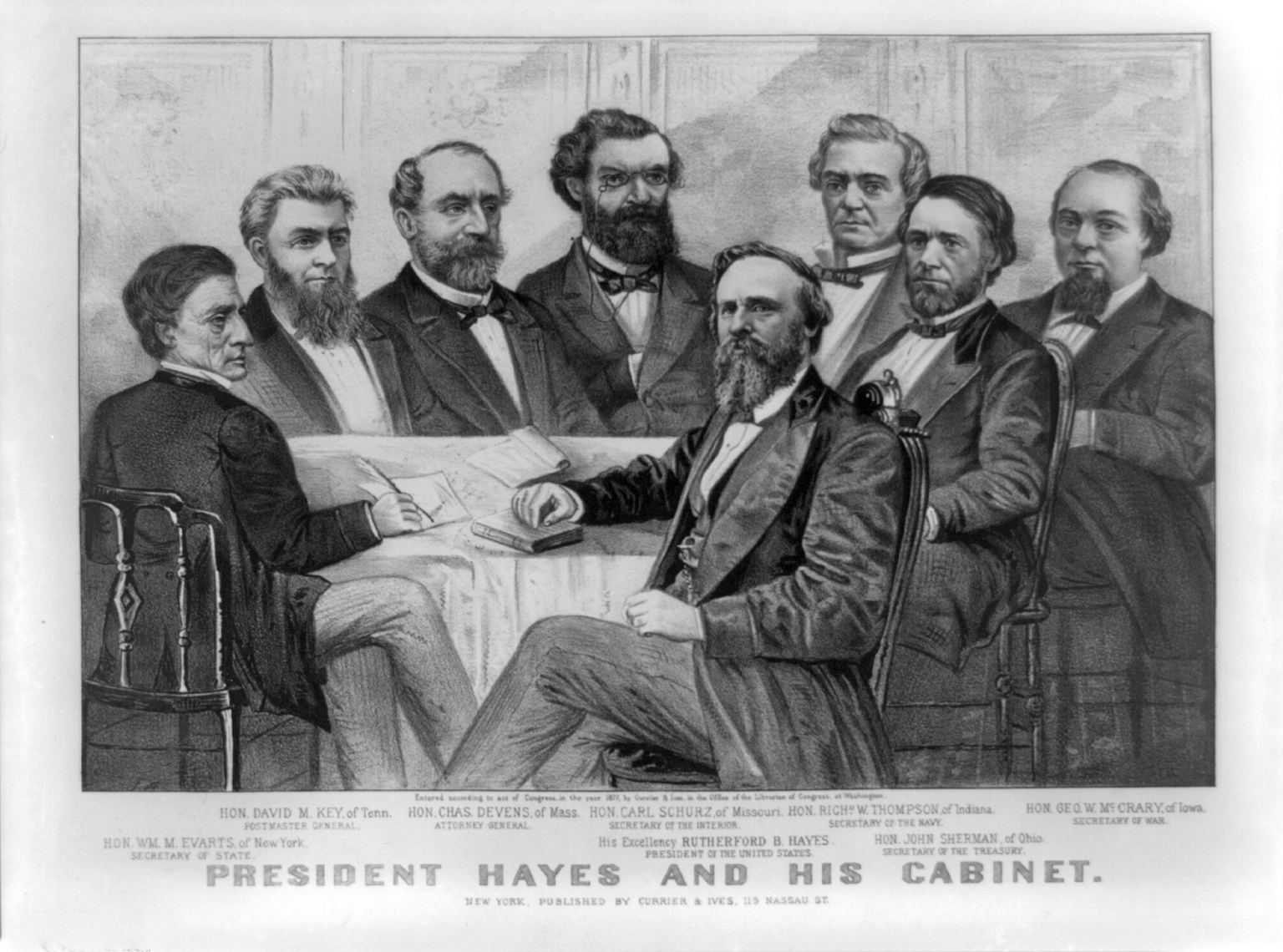

To show his commitment to reform, Hayes appointed one of the best-known advocates of reform at the time,

Carl Schurz

Carl Schurz (; March 2, 1829 – May 14, 1906) was a German revolutionary and an American statesman, journalist, and reformer. He immigrated to the United States after the German revolutions of 1848–1849 and became a prominent member of the new ...

, to be

Secretary of the Interior Secretary of the Interior may refer to:

* Secretary of the Interior (Mexico)

* Interior Secretary of Pakistan

* Secretary of the Interior and Local Government (Philippines)

* United States Secretary of the Interior

See also

*Interior ministry

An ...

and asked Schurz and

Secretary of State William M. Evarts

William Maxwell Evarts (February 6, 1818February 28, 1901) was an American lawyer and statesman from New York who served as U.S. Secretary of State, U.S. Attorney General and U.S. Senator from New York. He was renowned for his skills as a litig ...

to lead a special cabinet committee charged with drawing up new rules for federal appointments.

Treasury Secretary John Sherman

John Sherman (May 10, 1823October 22, 1900) was an American politician from Ohio throughout the Civil War and into the late nineteenth century. A member of the Republican Party, he served in both houses of the U.S. Congress. He also served as ...

ordered

John Jay

John Jay (December 12, 1745 – May 17, 1829) was an American statesman, patriot, diplomat, abolitionist, signatory of the Treaty of Paris, and a Founding Father of the United States. He served as the second governor of New York and the f ...

to investigate the

New York Custom House

The United States Custom House, sometimes referred to as the New York Custom House, was the place where the United States Customs Service collected federal customs duties on imported goods within New York City.

Locations

The Custom House ...

, which was stacked with Conkling's spoilsmen. Jay's report suggested that the New York Custom House was so overstaffed with political appointees that 20% of the employees were expendable.

Although he could not convince Congress to prohibit the spoils system, Hayes issued an

executive order

In the United States, an executive order is a directive by the president of the United States that manages operations of the federal government. The legal or constitutional basis for executive orders has multiple sources. Article Two of t ...

that forbade federal office holders from being required to make campaign contributions or otherwise taking part in party politics.

Chester A. Arthur, the

Collector of the Port of New York, and his subordinates

Alonzo B. Cornell and

George H. Sharpe

George Henry Sharpe (February 26, 1828 – January 13, 1900) was an American lawyer, soldier, Secret Service officer, diplomat, politician, and Member of the Board of General Appraisers.

Sharpe was born in 1828, in Kingston, New York, into a p ...

, all Conkling supporters, refused to obey the order. In September 1877, Hayes demanded their resignations, which they refused to give. He submitted appointments of

Theodore Roosevelt, Sr.,

L. Bradford Prince, and

Edwin Merritt—all supporters of Evarts, Conkling's New York rival—to the Senate for confirmation as their replacements. The Senate's Commerce Committee, chaired by Conkling, voted unanimously to reject the nominees. The full Senate rejected Roosevelt and Prince by a vote of 31–25, and confirmed Merritt only because Sharpe's term had expired.

Hayes was forced to wait until July 1878, when he fired Arthur and Cornell during a Congressional recess and replaced them with

recess appointment

In the United States, a recess appointment is an appointment by the president of a federal official when the U.S. Senate is in recess. Under the U.S. Constitution's Appointments Clause, the President is empowered to nominate, and with the a ...

s of Merritt and

Silas W. Burt, respectively. Conkling opposed confirmation of the appointees when the Senate reconvened in February 1879, but Merritt was approved by a vote of 31–25 and Burt by 31–19, giving Hayes his most significant civil service reform victory.

For the remainder of his term, Hayes pressed Congress to enact permanent reform legislation and fund the

United States Civil Service Commission

The United States Civil Service Commission was a government agency of the federal government of the United States and was created to select employees of federal government on merit rather than relationships. In 1979, it was dissolved as part of t ...

, even using his last

annual message to Congress in 1880 to appeal for reform. Reform legislation did not pass during Hayes's presidency, but his advocacy provided "a significant precedent as well as the political impetus for the

Pendleton Act of 1883," which was signed into law by President Chester Arthur. Hayes allowed some exceptions to the ban on assessments, permitting

George Congdon Gorham, secretary of the Republican Congressional Committee, to solicit campaign contributions from federal officeholders during the Congressional elections of 1878. In 1880, Hayes quickly forced

Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

Richard W. Thompson to resign after Thompson accepted a $25,000 salary for a nominal job offered by French engineer

Ferdinand de Lesseps

Ferdinand Marie, Comte de Lesseps (; 19 November 1805 – 7 December 1894) was a French diplomat and later developer of the Suez Canal, which in 1869 joined the Mediterranean and Red Seas, substantially reducing sailing distances and times ...

to promote a French canal in Panama.

Hayes also dealt with

corruption in the postal service. In 1880, Schurz and Senator

John A. Logan asked Hayes to shut down the "

star route Star routes is a term used in connection with the United States postal service and the contracting of mail delivery services. The term is defunct as of 1970, but still is occasionally used to refer to Highway Contract Routes (HCRs), which replaced t ...

" rings, a system of corrupt contract profiteering in the Postal Service, and to fire Second Assistant Postmaster-General

Thomas J. Brady

Thomas Jefferson Brady (February 12, 1839 – April 22, 1904) was an American Republican politician and Civil War officer.

Early life

Brady was born in Muncie, Indiana in 1839, the son of John Brady, the first mayor of Muncie, and his wife, Ma ...

, the alleged ringleader. Hayes stopped granting new star route contracts but let existing contracts continue to be enforced. Democrats accused him of delaying proper investigation so as not to damage Republicans' chances in the 1880 elections but did not press the issue in their campaign literature, as members of both parties were implicated in the corruption. Historian

Hans L. Trefousse

Hans Louis Trefousse (December 18, 1921, Frankfurt/Main, Germany – January 8, 2010, Staten Island, NY) was a German-born American author and historian of the Reconstruction Era and World War II. He was a long time professor (and professor emerit ...

later wrote that Hayes "hardly knew the chief suspect

radyand certainly had no connection with the

tar routecorruption." Although Hayes and the Congress both investigated the contracts and found no compelling evidence of wrongdoing, Brady and others were indicted for conspiracy in 1882. After two trials, the defendants were acquitted in 1883.