Roman Wales on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Roman era in the area of modern

The Roman era in the area of modern

/ref> The

On the eve of the Roman invasion of Wales, the Roman military under

On the eve of the Roman invasion of Wales, the Roman military under

There is uncertainty regarding which parts of Wales were invaded by the Romans prior to the conquest of Anglesey in AD 60. This uncertainty stems from a lack of written source material, with Tacitus as the only written source documenting this period.

Tacitus records that a tribe had attacked a Roman ally in Britain. According to Tacitus, the tribe that was responsible for this incursion was the 'Decangi', which scholars associate with the Welsh

There is uncertainty regarding which parts of Wales were invaded by the Romans prior to the conquest of Anglesey in AD 60. This uncertainty stems from a lack of written source material, with Tacitus as the only written source documenting this period.

Tacitus records that a tribe had attacked a Roman ally in Britain. According to Tacitus, the tribe that was responsible for this incursion was the 'Decangi', which scholars associate with the Welsh

The mineral wealth of Britain was well-known prior to the Roman invasion and was one of the expected benefits of conquest. All mineral extractions were state-sponsored and under military control, as mineral rights belonged to the emperor. His agents soon found substantial deposits of gold, copper, and lead in Wales, along with some

The mineral wealth of Britain was well-known prior to the Roman invasion and was one of the expected benefits of conquest. All mineral extractions were state-sponsored and under military control, as mineral rights belonged to the emperor. His agents soon found substantial deposits of gold, copper, and lead in Wales, along with some

The production of goods for trade and export in Roman Britain was concentrated in the south and east, with virtually none situated in Wales.

This was largely due to circumstance, with iron forges located near iron supplies,

The production of goods for trade and export in Roman Britain was concentrated in the south and east, with virtually none situated in Wales.

This was largely due to circumstance, with iron forges located near iron supplies,

The Romans occupied the whole of the area now known as Wales, where they built

The Romans occupied the whole of the area now known as Wales, where they built

In the ''

In the ''

By the middle of the 4th century the Roman presence in Britain was no longer vigorous. Once-unfortified towns were now being surrounded by defensive walls, including both

By the middle of the 4th century the Roman presence in Britain was no longer vigorous. Once-unfortified towns were now being surrounded by defensive walls, including both

Historical accounts tell of the upheavals in the

Historical accounts tell of the upheavals in the  Historically Magnus Maximus was a Roman general who served in Britain in the late 4th century, launching his successful bid for imperial power from Britain in 383. This is the last date for any evidence of a Roman military presence in Wales, the western

Historically Magnus Maximus was a Roman general who served in Britain in the late 4th century, launching his successful bid for imperial power from Britain in 383. This is the last date for any evidence of a Roman military presence in Wales, the western

Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of WalesRoman Wales on the RCAHMW websiteClwyd-Powys Archaeological Trust info on Roman Wales58 pages of artifacts and places associated with Roman Wales on Gathering the Jewels the website of Welsh cultural history

* ttps://www.britainexpress.com/attraction-map.htm?Country=Wales&Attraction=Roman Map of Roman localities in Wales (click on the arrows to get detailed information) {{Authority control Roman history of modern countries and territories w

The Roman era in the area of modern

The Roman era in the area of modern Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the Bristol Channel to the south. It had a population in ...

began in 48 AD, with a military invasion by the imperial governor of Roman Britain

Roman Britain was the period in classical antiquity when large parts of the island of Great Britain were under occupation by the Roman Empire. The occupation lasted from AD 43 to AD 410. During that time, the territory conquered wa ...

. The conquest was completed by 78 AD, and Roman rule endured until the region was abandoned in 383 AD."The Romans in Wales", by Ben Johnson/ref> The

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

held a military occupation in most of Wales, except for the southern coastal region of South Wales

South Wales ( cy, De Cymru) is a loosely defined region of Wales bordered by England to the east and mid Wales to the north. Generally considered to include the historic counties of Glamorgan and Monmouthshire, south Wales extends westwards ...

, east of the Gower Peninsula

Gower ( cy, Gŵyr) or the Gower Peninsula () in southwest Wales, projects towards the Bristol Channel. It is the most westerly part of the historic county of Glamorgan. In 1956, the majority of Gower became the first area in the United Kingdom ...

, where there is a legacy of Romanisation

Romanization or romanisation, in linguistics, is the conversion of text from a different writing system to the Roman (Latin) script, or a system for doing so. Methods of romanization include transliteration, for representing written text, and ...

in the region, and some southern sites such as Carmarthen

Carmarthen (, RP: ; cy, Caerfyrddin , "Merlin's fort" or "Sea-town fort") is the county town of Carmarthenshire and a community in Wales, lying on the River Towy. north of its estuary in Carmarthen Bay. The population was 14,185 in 2011, ...

, which was the civitas

In Ancient Rome, the Latin term (; plural ), according to Cicero in the time of the late Roman Republic, was the social body of the , or citizens, united by law (). It is the law that binds them together, giving them responsibilities () on th ...

capital of the Demetae tribe. The only town in Wales founded by the Romans, Caerwent

Caerwent ( cy, Caer-went) is a village and community in Monmouthshire, Wales. It is located about five miles west of Chepstow and 11 miles east of Newport. It was founded by the Romans as the market town of ''Venta Silurum'', an important sett ...

, is located in South Wales.

Wales was a rich source of mineral wealth, and the Romans used their engineering

Engineering is the use of scientific principles to design and build machines, structures, and other items, including bridges, tunnels, roads, vehicles, and buildings. The discipline of engineering encompasses a broad range of more speciali ...

technology

Technology is the application of knowledge to reach practical goals in a specifiable and reproducible way. The word ''technology'' may also mean the product of such an endeavor. The use of technology is widely prevalent in medicine, scien ...

to extract large amounts of gold, copper, and lead, as well as modest amounts of some other metals such as zinc

Zinc is a chemical element with the symbol Zn and atomic number 30. Zinc is a slightly brittle metal at room temperature and has a shiny-greyish appearance when oxidation is removed. It is the first element in group 12 (IIB) of the periodi ...

and silver.

The Roman campaigns of conquest in Wales appear in surviving ancient sources, who record in particular the resistance and ultimate conquest of two of the five native tribes, the Silures

The Silures ( , ) were a powerful and warlike tribe or tribal confederation of ancient Britain, occupying what is now south east Wales and perhaps some adjoining areas. They were bordered to the north by the Ordovices; to the east by the Dobun ...

of the south east, and the Ordovices

The Ordovīcēs (Common Brittonic: *''Ordowīcī'') were one of the Celtic tribes living in Great Britain before the Roman invasion. Their tribal lands were located in present-day North Wales and England, between the Silures to the south and the ...

of central and northern Wales.

Aside from the many Roman-related discoveries at sites along the southern coast, Roman archaeological remains in Wales consist almost entirely of military roads and fortifications.

Wales before the Roman conquest

Archaeologists generally agree that the majority of the British Isles were inhabited by speakers of Celtic languages (Celts

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient ...

) before the Roman invasion, organized into many tribes

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide usage of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. This definition is contested, in part due to confli ...

.Hayes, M.A.R.M., & Hayes, A. (1995). ''Archaeology of the British Isles'' (1st ed.). Routledge. Ch. 6. The area now known as Wales had no political or social unity and Romans did not give the area as a whole any distinctive name.Malcolm, Todd (2007). ''Companion to Roman Britain. Blackwell Companions to British History''. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons. Ch. 5.

Northern Wales and southern Wales have some notable cultural differences before the Roman invasion, and should not be considered one entity.Cunliffe, Barry. (2006) ''Iron Age Communities in Britain : An Account of England, Scotland and Wales from the Seventh Century BC until the Roman Conquest.'' Milton: Taylor & Francis Group. Ch. 5 Southern Wales was advancing along with the rest of Britain throughout the Iron Age, whereas the Northern parts of Wales were conservative and slower to advance. Along with their technological advancement, from the fifth to the first century BC, southern Wales became more heavily and densely populated. Southern Wales had more in common with the north than it did with the rest of Britain, and they saw little outside influence up until the Roman conquest.

Hill forts

A hillfort is a type of earthwork used as a fortified refuge or defended settlement, located to exploit a rise in elevation for defensive advantage. They are typically European and of the Bronze Age or Iron Age. Some were used in the post-Rom ...

are one of the most common sites found throughout Iron-Age Wales, and this is what archaeologists mostly rely on for most of their evidence. Nevertheless, due to the relative lack of archaeological activity, survey groupings of these forts throughout Wales can be uneven or misleading. Modern scholars theorize that Wales before the Roman conquest was similar to the rest of Iron Age Britain

The British Iron Age is a conventional name used in the archaeology of Great Britain, referring to the prehistoric and protohistoric phases of the Iron Age culture of the main island and the smaller islands, typically excluding prehistoric I ...

; however, this is still debated due to the sparsity of evidence.Cunliffe, Barry. (2006) ''Iron Age Communities in Britain : An Account of England, Scotland and Wales from the Seventh Century BC until the Roman Conquest.'' Milton: Taylor & Francis Group. Ch. 4 For the most part, the regions' archaeological legacy consists of burials and hill forts, Wales (along with more distant parts of Britain) gradually stopped making pottery throughout the Iron Age (which usually helps archaeologists explore the distant past). However, this is not to say that there was no trade within the region; evidenced by archaeological assemblages (such as the Wilburton complex) suggest that there was trade throughout all of Britain, connecting with Ireland and Northern France.

Britain in 47 AD

On the eve of the Roman invasion of Wales, the Roman military under

On the eve of the Roman invasion of Wales, the Roman military under Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

Aulus Plautius

Aulus Plautius was a Roman politician and general of the mid-1st century. He began the Roman conquest of Britain in 43, and became the first governor of the new province, serving from 43 to 46 CE.

Career

Little is known of Aulus Plautius's e ...

was in control of all of southeastern Britain as well as Dumnonia

Dumnonia is the Latinised name for a Brythonic kingdom that existed in Sub-Roman Britain between the late 4th and late 8th centuries CE in the more westerly parts of present-day South West England. It was centred in the area of modern Devon, ...

, perhaps including the lowland English Midlands

The Midlands (also referred to as Central England) are a part of England that broadly correspond to the Kingdom of Mercia of the Early Middle Ages, bordered by Wales, Northern England and Southern England. The Midlands were important in the ...

as far as the Dee Estuary

The Dee Estuary ( cy, Aber Dyfrdwy) is a large estuary by means of which the River Dee flows into Liverpool Bay. The estuary starts near Shotton after a five-mile (8 km) 'canalised' section and the river soon swells to be several mile ...

and the River Mersey

The River Mersey () is in North West England. Its name derives from Old English and means "boundary river", possibly referring to its having been a border between the ancient kingdoms of Mercia and Northumbria. For centuries it has formed par ...

, and having an understanding with the Brigantes

The Brigantes were Ancient Britons who in pre-Roman times controlled the largest section of what would become Northern England. Their territory, often referred to as Brigantia, was centred in what was later known as Yorkshire. The Greek geog ...

to the north. They controlled most of the island's centers of wealth, as well as much of its trade and resources.

In Wales the known tribes (the list may be incomplete) included the Ordovices

The Ordovīcēs (Common Brittonic: *''Ordowīcī'') were one of the Celtic tribes living in Great Britain before the Roman invasion. Their tribal lands were located in present-day North Wales and England, between the Silures to the south and the ...

and Deceangli

The Deceangli or Deceangi (Welsh: Tegeingl) were one of the Celtic tribes living in Britain, prior to the Roman invasion of the island. The tribe lived in the region near the modern city of Chester but it is uncertain whether their territory co ...

in the north, and the Silures

The Silures ( , ) were a powerful and warlike tribe or tribal confederation of ancient Britain, occupying what is now south east Wales and perhaps some adjoining areas. They were bordered to the north by the Ordovices; to the east by the Dobun ...

and Demetae in the south. Archaeology combined with ancient Greek and Roman accounts have shown that there was exploitation of natural resources, such as copper, gold, tin, lead and silver at multiple locations in Britain, including in Wales. Apart from this we have little knowledge of the Welsh tribes of this era.

Roman invasion and conquest

There is uncertainty regarding which parts of Wales were invaded by the Romans prior to the conquest of Anglesey in AD 60. This uncertainty stems from a lack of written source material, with Tacitus as the only written source documenting this period.

Tacitus records that a tribe had attacked a Roman ally in Britain. According to Tacitus, the tribe that was responsible for this incursion was the 'Decangi', which scholars associate with the Welsh

There is uncertainty regarding which parts of Wales were invaded by the Romans prior to the conquest of Anglesey in AD 60. This uncertainty stems from a lack of written source material, with Tacitus as the only written source documenting this period.

Tacitus records that a tribe had attacked a Roman ally in Britain. According to Tacitus, the tribe that was responsible for this incursion was the 'Decangi', which scholars associate with the Welsh Deceangli

The Deceangli or Deceangi (Welsh: Tegeingl) were one of the Celtic tribes living in Britain, prior to the Roman invasion of the island. The tribe lived in the region near the modern city of Chester but it is uncertain whether their territory co ...

. The Romans responded swiftly, imposing restrictions upon all of the suspected tribes, then they began to move against the Deceangli. The Roman conquest of this tribe is predicted to have been between the years AD 48 or 49.

Shortly following this, the Romans campaigned against the Silures

The Silures ( , ) were a powerful and warlike tribe or tribal confederation of ancient Britain, occupying what is now south east Wales and perhaps some adjoining areas. They were bordered to the north by the Ordovices; to the east by the Dobun ...

tribe of south-eastern Wales which must have had previous encounters with the Roman army. Due to the Silures' ferocity and insubordination, the Romans built a legionary fortress to suppress them. The Silures (and later the Ordovices) were led by Caratacus

Caratacus (Brythonic ''*Caratācos'', Middle Welsh ''Caratawc''; Welsh ''Caradog''; Breton ''Karadeg''; Greek ''Καράτακος''; variants Latin ''Caractacus'', Greek ''Καρτάκης'') was a 1st-century AD British chieftain of the ...

, a king who fled South-eastern England. Under Caratacus' rule, the Welsh fought the Romans in a pitched battle which resulted in the loss of all the Ordovician territory. This defeat was not crushing, and Caratacus continued to fight the Romans, defeating two auxiliary cohorts. Caratacus fled to the Queen of the Brigantes. Queen Cartimandua was loyal to the Romans and handed Caratacus over to Roman forces 51 AD.Cunliffe, Barry. (2006) ''Iron Age Communities in Britain : An Account of England, Scotland and Wales from the Seventh Century BC until the Roman Conquest.'' Milton: Taylor & Francis Group. Ch. 10 While dealing with all these problems, in AD 52, the Roman governor, Publius Ostorius Scapula

Publius Ostorius Scapula standing at the terrace of the Roman Baths (Bath)

Publius Ostorius Scapula (died 52) was a Roman statesman and general who governed Britain from 47 until his death, and was responsible for the defeat and capture of Ca ...

, died. His death gave the Silures a respite before Scapula's successor, Didius Gallus, would arrive. In that time, the Silures defeated a Roman legion led by Manlius Valens.

In AD 54, emperor Claudius

Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (; 1 August 10 BC – 13 October AD 54) was the fourth Roman emperor, ruling from AD 41 to 54. A member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, Claudius was born to Drusus and Antonia Minor ...

died and was succeeded by Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68), was the fifth Roman emperor and final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 un ...

. This caused the situation in Britain to change, and Rome began to focus more on consolidating their power in Britain instead of expanding their territory. This is evidenced from the archaeological record, which finds vexillation fortresses (small Roman forts) at the time of Nero's succession.

After a short period of relative inaction, Quintus Veranius became governor of Britain and decided it was time to conquer the rest of the British Isles. Veranius began to campaign against the Silures, but in AD 58 he died, one year after he was appointed to Britain. Suetonius Paulinus

Gaius Suetonius Paulinus (fl. AD 41–69) was a Roman general best known as the commander who defeated the rebellion of Boudica.

Early life

Little is known of Suetonius' family, but it likely came from Pisaurum (modern Pesaro), a town on the Adr ...

was his successor, and it would seem that Veranius had some success in his campaigns because Paulinus began to shift north (suggesting that there was no notable opposition in the south). Paulinus was quite successful in his conquest of northern Wales, and it would seem by AD 60 that he had pushed all the way to the Irish Sea

The Irish Sea or , gv, Y Keayn Yernagh, sco, Erse Sie, gd, Muir Èireann , Ulster-Scots: ''Airish Sea'', cy, Môr Iwerddon . is an extensive body of water that separates the islands of Ireland and Great Britain. It is linked to the C ...

because he was preparing for a conquest of Anglesey.

Anglesey was swelling with migrants fleeing from the Romans, and it had become a stronghold for the Druids. Despite the Romans initial fear and superstition of Anglesey, they were able to achieve victory and subdue the Welsh tribes. However, this victory was short lived and a massive British rebellion led by Boudica

Boudica or Boudicca (, known in Latin chronicles as Boadicea or Boudicea, and in Welsh as ()), was a queen of the ancient British Iceni tribe, who led a failed uprising against the conquering forces of the Roman Empire in AD 60 or 61. She ...

erupted in the east and interrupted the consolidation of Wales.

It was not until AD 74 that Julius Frontinus resumed the campaigns against Wales. By the end of his term in AD 77, he had subdued most of Wales.

Only one tribe was left mostly intact throughout the conquest - the Demetae. This tribe did not oppose Rome, and developed peacefully, isolated from its neighbors and the Roman Empire. The Demetae were the only pre-Roman Welsh tribe to emerge from Roman rule with their tribal name intact.

Wales in Roman Society

Mining

The mineral wealth of Britain was well-known prior to the Roman invasion and was one of the expected benefits of conquest. All mineral extractions were state-sponsored and under military control, as mineral rights belonged to the emperor. His agents soon found substantial deposits of gold, copper, and lead in Wales, along with some

The mineral wealth of Britain was well-known prior to the Roman invasion and was one of the expected benefits of conquest. All mineral extractions were state-sponsored and under military control, as mineral rights belonged to the emperor. His agents soon found substantial deposits of gold, copper, and lead in Wales, along with some zinc

Zinc is a chemical element with the symbol Zn and atomic number 30. Zinc is a slightly brittle metal at room temperature and has a shiny-greyish appearance when oxidation is removed. It is the first element in group 12 (IIB) of the periodi ...

and silver. Gold was mined at Dolaucothi

The Dolaucothi Gold Mines (; cy, Mwynfeydd Aur Dolaucothi) (), also known as the Ogofau Gold Mine, are ancient Roman surface and underground mines located in the valley of the River Cothi, near Pumsaint, Carmarthenshire, Wales. The gold mi ...

prior to the invasion, but Roman engineering

The ancient Romans were famous for their advanced engineering accomplishments. Technology for bringing running water into cities was developed in the east, but transformed by the Romans into a technology inconceivable in Greece. The architecture ...

would be applied to greatly increase the amount extracted, and to extract huge amounts of the other metals. This continued until the process was no longer practical or profitable, at which time the mine was abandoned., ''An Atlas of Roman Britain'', The Economy

Modern scholars have made efforts to quantify the value of these extracted metals to the Roman economy

The study of the Roman economy, which is, the economies of the ancient city-state of Rome and its empire during the Republican and Imperial periods remains highly speculative. There are no surviving records of business and government accounts, suc ...

, and to determine the point at which the Roman occupation of Britain was "profitable" to the Empire. While these efforts have not produced deterministic results, the benefits to Rome were substantial. The gold production at Dolaucothi alone may have been of economic significance.

Industrial production

The production of goods for trade and export in Roman Britain was concentrated in the south and east, with virtually none situated in Wales.

This was largely due to circumstance, with iron forges located near iron supplies,

The production of goods for trade and export in Roman Britain was concentrated in the south and east, with virtually none situated in Wales.

This was largely due to circumstance, with iron forges located near iron supplies, pewter

Pewter () is a malleable metal alloy consisting of tin (85–99%), antimony (approximately 5–10%), copper (2%), bismuth, and sometimes silver. Copper and antimony (and in antiquity lead) act as hardeners, but lead may be used in lower grades ...

(tin with some lead or copper) moulds located near the tin supplies and suitable soil (for the moulds), clusters of pottery

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other ceramic materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. Major types include earthenware, stoneware and ...

kiln

A kiln is a thermally insulated chamber, a type of oven, that produces temperatures sufficient to complete some process, such as hardening, drying, or chemical changes. Kilns have been used for millennia to turn objects made from clay int ...

s located near suitable clayey soil, grain-drying ovens located in agricultural areas where sheep raising (for wool) was also located, and salt production concentrated in its historical pre-Roman locations. Glass-making sites were located in or near urban centres.

In Wales none of the needed materials were available in suitable combination, and the forested, mountainous countryside was not amenable to this kind of industrialisation.

Clusters of tile

Tiles are usually thin, square or rectangular coverings manufactured from hard-wearing material such as ceramic, stone, metal, baked clay, or even glass. They are generally fixed in place in an array to cover roofs, floors, walls, edges, or ...

ries, both large and small, were at first operated by the Roman military to meet their own needs, and so there were temporary sites wherever the army went and could find suitable soil. This included a few places in Wales. However, as Roman influence grew, the army was able to obtain tiles from civilian sources who located their kilns in the lowland areas containing good soil, and then shipped the tiles to wherever they were needed.

Romanisation

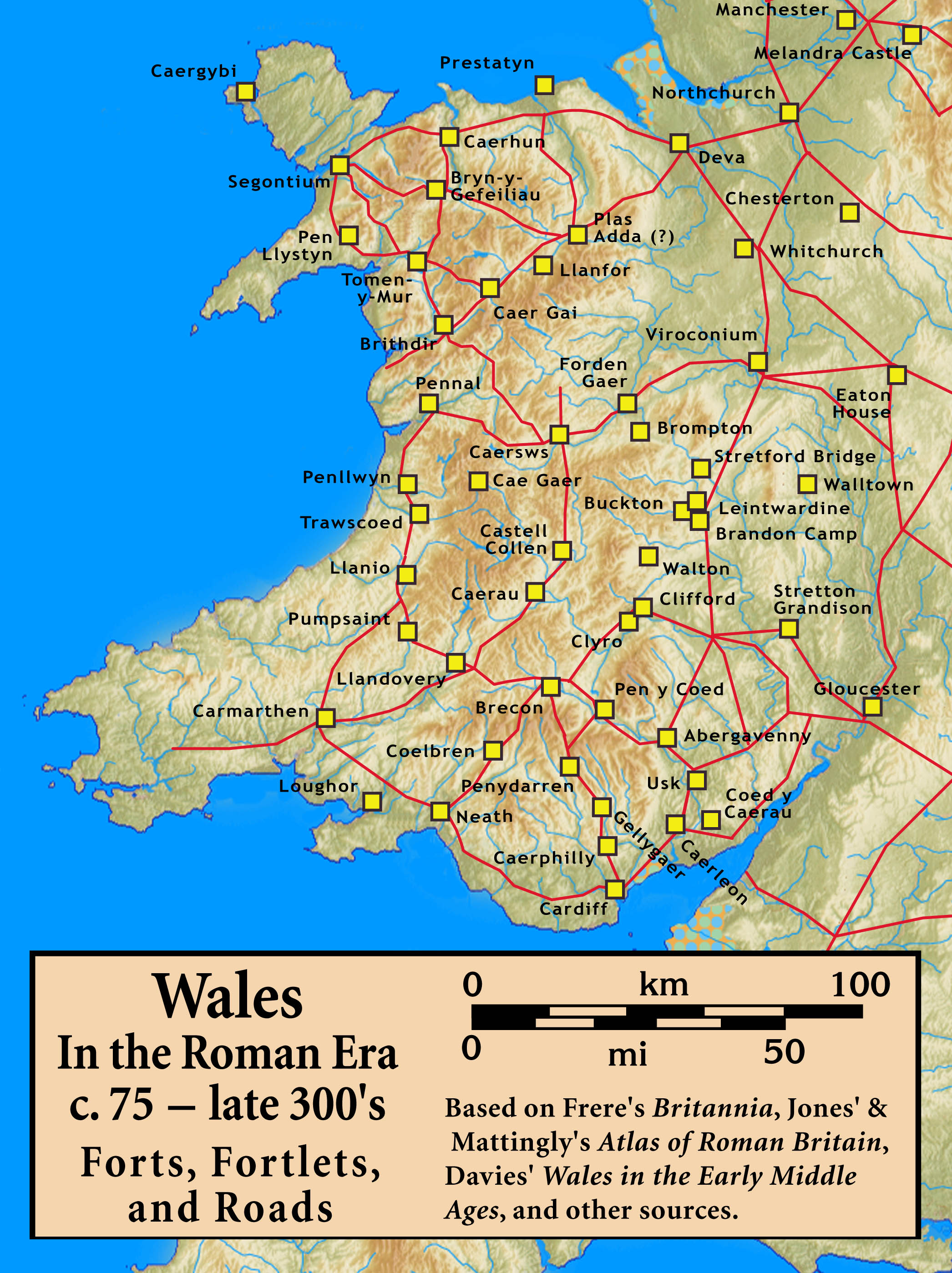

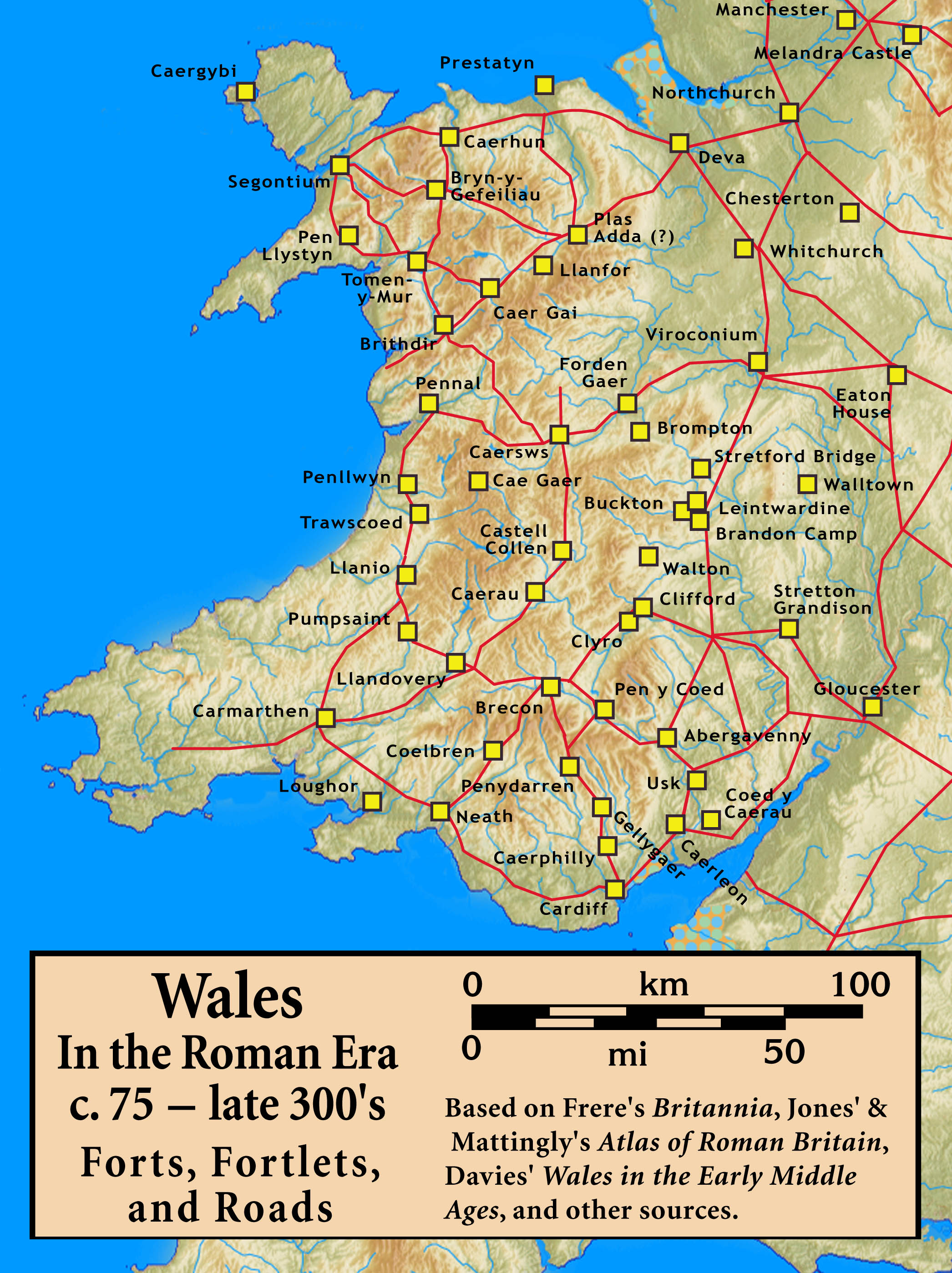

The Romans occupied the whole of the area now known as Wales, where they built

The Romans occupied the whole of the area now known as Wales, where they built Roman roads

Roman roads ( la, viae Romanae ; singular: ; meaning "Roman way") were physical infrastructure vital to the maintenance and development of the Roman state, and were built from about 300 BC through the expansion and consolidation of the Roman Re ...

and ''castra

In the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire, the Latin word ''castrum'', plural ''castra'', was a military-related term.

In Latin usage, the singular form ''castrum'' meant 'fort', while the plural form ''castra'' meant 'camp'. The singular a ...

'', mined gold at Luentinum and conducted commerce, but their interest in the area was limited because of the difficult geography and shortage of flat agricultural land. Most of the Roman remains in Wales are military in nature. Sarn Helen

Sarn Helen refers to several stretches of Roman road in Wales. The route, which follows a meandering course through central Wales, connects Aberconwy in the north with Carmarthen in the west. Despite its length, academic debate continues as t ...

, a major highway, linked the North with South Wales.

The area was controlled by Roman legion

The Roman legion ( la, legiō, ) was the largest military unit of the Roman army, composed of 5,200 infantry and 300 equites (cavalry) in the period of the Roman Republic (509 BC–27 BC) and of 5,600 infantry and 200 auxilia in the period o ...

ary bases at Deva Victrix

Deva Victrix, or simply Deva, was a legionary fortress and town in the Roman province of Britannia on the site of the modern city of Chester. The fortress was built by the Legio II ''Adiutrix'' in the 70s AD as the Roman army advanced north ag ...

(modern Chester

Chester is a cathedral city and the county town of Cheshire, England. It is located on the River Dee, close to the English–Welsh border. With a population of 79,645 in 2011,"2011 Census results: People and Population Profile: Chester Loca ...

) and Isca Augusta (Caerleon

Caerleon (; cy, Caerllion) is a town and community in Newport, Wales. Situated on the River Usk, it lies northeast of Newport city centre, and southeast of Cwmbran. Caerleon is of archaeological importance, being the site of a notable Roman ...

), two of the three such bases in Roman Britain, with roads linking these bases to auxiliaries' forts such as Segontium

Segontium ( owl, Cair Segeint) is a Roman fort on the outskirts of Caernarfon in Gwynedd, North Wales. The fort, which survived until the end of the Roman occupation of Britain, was garrisoned by Roman auxiliaries from present-day Belgium and Ge ...

(Caernarfon

Caernarfon (; ) is a royal town, community and port in Gwynedd, Wales, with a population of 9,852 (with Caeathro). It lies along the A487 road, on the eastern shore of the Menai Strait, opposite the Isle of Anglesey. The city of Bangor ...

) and Moridunum (Carmarthen

Carmarthen (, RP: ; cy, Caerfyrddin , "Merlin's fort" or "Sea-town fort") is the county town of Carmarthenshire and a community in Wales, lying on the River Towy. north of its estuary in Carmarthen Bay. The population was 14,185 in 2011, ...

).

Furthermore, South-east Wales was the most Romanised part of the country. It is possible that Roman estates in the area survived as recognisable units into the eighth century: the kingdom of Gwent is likely to have been founded by direct descendants of the (romanised) Silurian ruling class '

The best indicators of Romanising acculturation is the presence of urban sites (areas with towns, '' coloniae'', and tribal ''civitates

In Ancient Rome, the Latin term (; plural ), according to Cicero in the time of the late Roman Republic, was the social body of the , or citizens, united by law (). It is the law that binds them together, giving them responsibilities () on t ...

'') and ''villa

A villa is a type of house that was originally an ancient Roman upper class country house. Since its origins in the Roman villa, the idea and function of a villa have evolved considerably. After the fall of the Roman Republic, villas became ...

s'' in the countryside. In Wales, this can be said only of the southeasternmost coastal region of South Wales

South Wales ( cy, De Cymru) is a loosely defined region of Wales bordered by England to the east and mid Wales to the north. Generally considered to include the historic counties of Glamorgan and Monmouthshire, south Wales extends westwards ...

. The only ''civitates'' in Wales were at Carmarthen

Carmarthen (, RP: ; cy, Caerfyrddin , "Merlin's fort" or "Sea-town fort") is the county town of Carmarthenshire and a community in Wales, lying on the River Towy. north of its estuary in Carmarthen Bay. The population was 14,185 in 2011, ...

and Caerwent

Caerwent ( cy, Caer-went) is a village and community in Monmouthshire, Wales. It is located about five miles west of Chepstow and 11 miles east of Newport. It was founded by the Romans as the market town of ''Venta Silurum'', an important sett ...

. There were three small urban sites near Caerwent, and these and Roman Monmouth were the only other "urbanised" sites in Wales.

In the southwestern homeland of the Demetae, several sites have been classified as ''villas'' in the past, but excavation of these and examination of sites as yet unexcavated suggest that they are pre-Roman family homesteads, sometimes updated through Roman technology (such as stone masonry), but having a native character quite different from the true Roman-derived ''villas'' that are found to the east, such as in Oxfordshire

Oxfordshire is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the north west of South East England. It is a mainly rural county, with its largest settlement being the city of Oxford. The county is a centre of research and development, primaril ...

.

Perhaps surprisingly, the presence of Roman-era Latin inscriptions is not suggestive of full Romanisation. They are most numerous at military sites, and their occurrence elsewhere depended on access to suitable stone and the presence of stonemasons, as well as patronage. The Roman fort complex at Tomen y Mur

Tomen y Mur is a First Century AD Roman fort in Snowdonia, Gwynedd, Wales. The fortification, which lies on the slope of an isolated spur northeast of Llyn Trawsfynydd, was constructed during the North Wales campaigns of governor Gnaeus Juliu ...

near the coast of northwestern Wales has produced more inscriptions than either Segontium

Segontium ( owl, Cair Segeint) is a Roman fort on the outskirts of Caernarfon in Gwynedd, North Wales. The fort, which survived until the end of the Roman occupation of Britain, was garrisoned by Roman auxiliaries from present-day Belgium and Ge ...

(near modern Caernarfon) or Noviomagus Reginorum

Noviomagus Reginorum was Chichester's Roman heart, very little of which survives above ground. It lay in the land of the friendly Atrebates and is in the early medieval-founded English county of West Sussex. On the English Channel, Chichester ...

(Chichester

Chichester () is a cathedral city and civil parish in West Sussex, England.OS Explorer map 120: Chichester, South Harting and Selsey Scale: 1:25 000. Publisher:Ordnance Survey – Southampton B2 edition. Publishing Date:2009. It is the only ...

).

Hill forts

In areas of civil control, such as the territories of a ''civitas

In Ancient Rome, the Latin term (; plural ), according to Cicero in the time of the late Roman Republic, was the social body of the , or citizens, united by law (). It is the law that binds them together, giving them responsibilities () on th ...

'', the fortification and occupation of hill fort

A hillfort is a type of earthwork used as a fortified refuge or defended settlement, located to exploit a rise in elevation for defensive advantage. They are typically European and of the Bronze Age or Iron Age. Some were used in the post-Roma ...

s was banned as a matter of Roman policy. However, further inland and northward, a number of pre-Roman hill forts continued to be used in the Roman Era, while others were abandoned during the Roman Era, and still others were newly occupied. The inference is that local leaders who were willing to accommodate Roman interests were encouraged and allowed to continue, providing local leadership under local law and custom.

Religion

There is virtually no evidence to shed light on the practice of religion in Wales during the Roman era, save the anecdotal account of the strange appearance and bloodthirsty customs of thedruid

A druid was a member of the high-ranking class in ancient Celtic cultures. Druids were religious leaders as well as legal authorities, adjudicators, lorekeepers, medical professionals and political advisors. Druids left no written accounts. Whi ...

s of Anglesey by Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his two major works—the ...

during the conquest of Wales. It is fortunate for Rome's reputation that Tacitus described the druids as horrible, else it would be a story of the Roman massacre of defenceless, unarmed men and women. The likelihood of partisan propaganda and an appeal to salacious interests combine to suggest that the account merits suspicion.

The Welsh region of Britain was not significant to the Romanisation of the island and contains almost no buildings related to religious practice, save where the Roman military was located, and these reflect the practices of non-native soldiers. Any native religious sites would have been constructed of wood that has not survived and so are difficult to locate anywhere in Britain, let alone in mountainous, forest-covered Wales.

The time of the arrival of Christianity to Wales is unknown. Archaeology suggests that it came to Roman Britain slowly, gaining adherents among coastal merchants and in the upper classes first, and never becoming widespread outside of the southeast in the Roman Era. There is also evidence of a preference for non-Christian devotion in parts of Britain, such as in the upper regions of the Severn Estuary

The Severn Estuary ( cy, Aber Hafren) is the estuary of the River Severn, flowing into the Bristol Channel between South West England and South Wales. Its high tidal range, approximately , means that it has been at the centre of discussions in t ...

in the 4th century, from the Forest of Dean

The Forest of Dean is a geographical, historical and cultural region in the western part of the county of Gloucestershire, England. It forms a roughly triangular plateau bounded by the River Wye to the west and northwest, Herefordshire to ...

east of the River Wye

The River Wye (; cy, Afon Gwy ) is the fourth-longest river in the UK, stretching some from its source on Plynlimon in mid Wales to the Severn estuary. For much of its length the river forms part of the border between England and Wales ...

continuously around the coast of the estuary, up to and including Somerset

( en, All The People of Somerset)

, locator_map =

, coordinates =

, region = South West England

, established_date = Ancient

, established_by =

, preceded_by =

, origin =

, lord_lieutenant_office =Lord Lieutenant of Somerset

, lor ...

.

In the ''

In the ''De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae

''De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae'' ( la, On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain, sometimes just ''On the Ruin of Britain'') is a work written in Latin by the 6th-century AD British cleric St Gildas. It is a sermon in three parts condemning ...

'', written c. 540, Gildas

Gildas ( Breton: ''Gweltaz''; c. 450/500 – c. 570) — also known as Gildas the Wise or ''Gildas Sapiens'' — was a 6th-century British monk best known for his scathing religious polemic ''De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae'', which recount ...

provides a story of the martyrdom of Saint Alban

Saint Alban (; la, Albanus) is venerated as the first-recorded British Christian martyr, for which reason he is considered to be the British protomartyr. Along with fellow Saints Julius and Aaron, Alban is one of three named martyrs rec ...

at Verulamium

Verulamium was a town in Roman Britain. It was sited southwest of the modern city of St Albans in Hertfordshire, England. A large portion of the Roman city remains unexcavated, being now park and agricultural land, though much has been built upon ...

, and of Julius and Aaron at ''Legionum Urbis'', the 'City of the Legion', saying that this occurred during a persecution of Christians at a time when 'decrees' against them were issued. Bede

Bede ( ; ang, Bǣda , ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, The Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable ( la, Beda Venerabilis), was an English monk at the monastery of St Peter and its companion monastery of St Paul in the Kingdom ...

repeats the story in his ''Ecclesiastical History

__NOTOC__

Church history or ecclesiastical history as an academic discipline studies the history of Christianity and the way the Christian Church has developed since its inception.

Henry Melvill Gwatkin defined church history as "the spiritua ...

'', written c. 731. The otherwise unspecified 'City of the Legion' is arguably Caerleon

Caerleon (; cy, Caerllion) is a town and community in Newport, Wales. Situated on the River Usk, it lies northeast of Newport city centre, and southeast of Cwmbran. Caerleon is of archaeological importance, being the site of a notable Roman ...

, Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peopl ...

''Caerllion'', the 'Fortress of the Legion', and the only candidate with a long and continuous military presence that lay within a Romanised region of Britain, with nearby towns and a Roman ''civitas

In Ancient Rome, the Latin term (; plural ), according to Cicero in the time of the late Roman Republic, was the social body of the , or citizens, united by law (). It is the law that binds them together, giving them responsibilities () on th ...

''. Other candidates are Chester

Chester is a cathedral city and the county town of Cheshire, England. It is located on the River Dee, close to the English–Welsh border. With a population of 79,645 in 2011,"2011 Census results: People and Population Profile: Chester Loca ...

and Carlisle

Carlisle ( , ; from xcb, Caer Luel) is a city that lies within the Northern English county of Cumbria, south of the Scottish border at the confluence of the rivers Eden, Caldew and Petteril. It is the administrative centre of the City ...

, though both were located far from the Romanised area of Britain and had a transitory, more military-oriented history.

A parenthetical note concerns Saint Patrick

Saint Patrick ( la, Patricius; ga, Pádraig ; cy, Padrig) was a fifth-century Romano-British Christian missionary and bishop in Ireland. Known as the "Apostle of Ireland", he is the primary patron saint of Ireland, the other patron saints b ...

, a patron saint of Ireland. He was a Briton

British people or Britons, also known colloquially as Brits, are the citizens of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the British Overseas Territories, and the Crown dependencies.: British nationality law governs mod ...

born c. 387 in ''Banna Venta Berniae'', a location that is unknown due to the transcription errors in surviving manuscripts. His home is a matter of conjecture, with sites near Carlisle

Carlisle ( , ; from xcb, Caer Luel) is a city that lies within the Northern English county of Cumbria, south of the Scottish border at the confluence of the rivers Eden, Caldew and Petteril. It is the administrative centre of the City ...

favoured by some, while coastal South Wales

South Wales ( cy, De Cymru) is a loosely defined region of Wales bordered by England to the east and mid Wales to the north. Generally considered to include the historic counties of Glamorgan and Monmouthshire, south Wales extends westwards ...

is favoured by others.

Irish settlement

By the middle of the 4th century the Roman presence in Britain was no longer vigorous. Once-unfortified towns were now being surrounded by defensive walls, including both

By the middle of the 4th century the Roman presence in Britain was no longer vigorous. Once-unfortified towns were now being surrounded by defensive walls, including both Carmarthen

Carmarthen (, RP: ; cy, Caerfyrddin , "Merlin's fort" or "Sea-town fort") is the county town of Carmarthenshire and a community in Wales, lying on the River Towy. north of its estuary in Carmarthen Bay. The population was 14,185 in 2011, ...

and Caerwent

Caerwent ( cy, Caer-went) is a village and community in Monmouthshire, Wales. It is located about five miles west of Chepstow and 11 miles east of Newport. It was founded by the Romans as the market town of ''Venta Silurum'', an important sett ...

. Political control finally collapsed and a number of alien tribes then took advantage of the situation, raiding widely throughout the island, joined by Roman soldiers who had deserted and by elements of the native Britons themselves. Order was restored in 369, but Roman Britain would not recover.

It was at this time that Wales received an infusion of settlers from southern Ireland, the Uí Liatháin, Laigin

The Laigin, modern spelling Laighin (), were a Gaelic population group of early Ireland. They gave their name to the Kingdom of Leinster, which in the medieval era was known in Irish as ''Cóiced Laigen'', meaning "Fifth/province of the Leinsterm ...

, and possibly Déisi

The ''Déisi'' were a socially powerful class of peoples from Ireland that settled in Wales and western England between the ancient and early medieval period. The various peoples listed under the heading ''déis'' shared the same status in Gaeli ...

, the last no longer seen as certain, with only the first two verified by reliable sources and place-name evidence. The Irish were concentrated along the southern and western coasts, in Anglesey and Gwynedd

Gwynedd (; ) is a county and preserved county (latter with differing boundaries; includes the Isle of Anglesey) in the north-west of Wales. It shares borders with Powys, Conwy County Borough, Denbighshire, Anglesey over the Menai Strait, an ...

(excepting the cantref

A cantref ( ; ; plural cantrefi or cantrefs; also rendered as ''cantred'') was a medieval Welsh land division, particularly important in the administration of Welsh law.

Description

Land in medieval Wales was divided into ''cantrefi'', which wer ...

i of Arfon and Arllechwedd

The ancient Welsh cantref of Arllechwedd in north-west Wales was part of the kingdom of Gwynedd for much of its history until it was included in the new county of Caernarfonshire, together with Arfon and Llŷn under the terms of the Statute ...

), and in the territory of the Demetae.

The circumstances of their arrival are unknown, and theories include categorising them as "raiders", as "invaders" who established a hegemony, and as "foederati

''Foederati'' (, singular: ''foederatus'' ) were peoples and cities bound by a treaty, known as ''foedus'', with Rome. During the Roman Republic, the term identified the ''socii'', but during the Roman Empire, it was used to describe foreign stat ...

" invited by the Romans. It might as easily have been the consequence of a depopulation in Wales caused by plague or famine, both of which were usually ignored by ancient chroniclers.

What is known is that their characteristically Irish circular huts are found where they settled; that the inscription stones found in Wales, whether in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

or ogham

Ogham ( Modern Irish: ; mga, ogum, ogom, later mga, ogam, label=none ) is an Early Medieval alphabet used primarily to write the early Irish language (in the "orthodox" inscriptions, 4th to 6th centuries AD), and later the Old Irish langu ...

or both, are characteristically Irish; that when both Latin and ogham are present on a stone, the name in the Latin text is given in Brittonic form while the same name is given in Irish form in ogham; and that medieval Welsh royal genealogies include Irish-named ancestors who also appear in the native Irish narrative '' The Expulsion of the Déisi''. This phenomenon may however be the result of later influences and again only the presence of the Uí Liatháin and Laigin in Wales has been verified.

End of the Roman era

Historical accounts tell of the upheavals in the

Historical accounts tell of the upheavals in the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

during the 3rd and 4th centuries, with notice of the withdrawal of troops from Roman Britain

Roman Britain was the period in classical antiquity when large parts of the island of Great Britain were under occupation by the Roman Empire. The occupation lasted from AD 43 to AD 410. During that time, the territory conquered wa ...

in support of the imperial ambitions of Roman generals stationed there. In much of Wales, where Roman troops were the only indication of Roman rule, that rule ended when troops left and did not return. The end came to different regions at different times.

Tradition holds that Roman customs held on for several years in southern Wales, lasting into the end of the 5th century and early 6th century, and that is true in part. Caerwent continued to be occupied after the Roman departure, while Carmarthen was probably abandoned in the late 4th century. In addition, southwestern Wales was the tribal territory of the Demetae, who had never become thoroughly Romanised. The entire region of southwestern Wales had been settled by Irish newcomers in the late 4th century, and it seems far-fetched to suggest that they were ever fully Romanised.

However, in the southeast Wales, following the withdrawal of the Roman legions from Britain, the town of Venta Silurum

Venta Silurum was a town in the Roman province of ''Britannia'' or Britain. Today it consists of remains in the village of Caerwent in Monmouthshire, south east Wales. Much of it has been archaeologically excavated and is on display to the publ ...

(Caerwent) remained occupied by Romano-Britons until at least the early sixth century: Early Christian

Early Christianity (up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325) spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and beyond. Originally, this progression was closely connected to already established Jewish centers in the Holy Land and the Jewis ...

worship was still established in the town, that might have had a bishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ...

with a monastery in the second half of that century.

Magnus Maximus

In Welsh literary tradition, Magnus Maximus

Magnus Maximus (; cy, Macsen Wledig ; died 8 August 388) was Roman emperor of the Western Roman Empire from 383 to 388. He usurped the throne from emperor Gratian in 383 through negotiation with emperor Theodosius I.

He was made emperor in B ...

is the central figure in the emergence of a free Britain in the post-Roman era. Royal and religious genealogies compiled in the Middle Ages have him as the ancestor of kings and saints. In the Welsh story of ''Breuddwyd Macsen Wledig'' (''The Dream of Emperor Maximus''), he is Emperor of Rome and marries a wondrous British woman, telling her that she may name her desires, to be received as a wedding portion. She asks that her father be given sovereignty over Britain, thus formalising the transfer of authority from Rome back to the Britons themselves.

Historically Magnus Maximus was a Roman general who served in Britain in the late 4th century, launching his successful bid for imperial power from Britain in 383. This is the last date for any evidence of a Roman military presence in Wales, the western

Historically Magnus Maximus was a Roman general who served in Britain in the late 4th century, launching his successful bid for imperial power from Britain in 383. This is the last date for any evidence of a Roman military presence in Wales, the western Pennines

The Pennines (), also known as the Pennine Chain or Pennine Hills, are a range of uplands running between three regions of Northern England: North West England on the west, North East England and Yorkshire and the Humber on the east. Common ...

, and Deva (i.e., the entire non-Romanised region of Britain south of Hadrian's Wall

Hadrian's Wall ( la, Vallum Aelium), also known as the Roman Wall, Picts' Wall, or ''Vallum Hadriani'' in Latin, is a former defensive fortification of the Roman province of Britannia, begun in AD 122 in the reign of the Emperor Hadrian. Ru ...

). Coins dated later than 383 have been excavated along the Wall, suggesting that troops were not stripped from it, as was once thought., ''Britannia'', The End of Roman Britain. In the ''De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae

''De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae'' ( la, On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain, sometimes just ''On the Ruin of Britain'') is a work written in Latin by the 6th-century AD British cleric St Gildas. It is a sermon in three parts condemning ...

'' written c. 540, Gildas

Gildas ( Breton: ''Gweltaz''; c. 450/500 – c. 570) — also known as Gildas the Wise or ''Gildas Sapiens'' — was a 6th-century British monk best known for his scathing religious polemic ''De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae'', which recount ...

says that Maximus left Britain not only with all of its Roman troops, but also with all of its armed bands, governors, and the flower of its youth, never to return. Having left with the troops and senior administrators, and planning to continue as the ruler of Britain, his practical course was to transfer local authority to local rulers. Welsh legend provides a mythic story that says he did exactly that.

After he became emperor of the Western Roman Empire, Maximus would return to Britain to campaign against the Picts

The Picts were a group of peoples who lived in what is now northern and eastern Scotland (north of the Firth of Forth) during Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Where they lived and what their culture was like can be inferred from ea ...

and Scots (i.e., Irish), probably in support of Rome's long-standing allies the Damnonii, Votadini

The Votadini, also known as the ''Uotadini'', ''Wotādīni'', ''Votādīni'', or ''Otadini'' were a Celtic Britons, Brittonic people of the British Iron Age, Iron Age in Great Britain. Their territory was in what is now south-east Scotland and ...

, and Novantae (all located in modern Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

). While there he likely made similar arrangements for a formal transfer of authority to local chiefs: the later rulers of Galloway

Galloway ( ; sco, Gallowa; la, Gallovidia) is a region in southwestern Scotland comprising the historic counties of Wigtownshire and Kirkcudbrightshire. It is administered as part of the council area of Dumfries and Galloway.

A native or ...

, home to the Novantae, would claim Maximus as the founder of their line, the same as did the Welsh kings.

Maximus would rule the Roman West until he was killed in 388. A succession of governors would rule southeastern Britain until 407, but there is nothing to suggest that any Roman effort was made to regain control of the west or north after 383, and that year would be the definitive end of the Roman era in Wales.

Legacy

Wendy Davies has argued that the later medieval Welsh approach to property and estates was a Roman legacy, but this issue and others related to legacy are not yet resolved. For example,Leslie Alcock

Leslie Alcock (24 April 1925 – 6 June 2006) was Professor of Archaeology at the University of Glasgow, and one of the leading archaeologists of Early Medieval Britain. His major excavations included Dinas Powys hill fort in Wales, Cadbury C ...

has argued that that approach to property and estates cannot pre-date the 6th century and is thus post-Roman.

There was little Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

linguistic heritage left to the Welsh language

Welsh ( or ) is a Celtic language of the Brittonic subgroup that is native to the Welsh people. Welsh is spoken natively in Wales, by some in England, and in Y Wladfa (the Welsh colony in Chubut Province, Argentina). Historically, it h ...

, only a number of borrowings from the Latin lexicon

A lexicon is the vocabulary of a language or branch of knowledge (such as nautical or medical). In linguistics, a lexicon is a language's inventory of lexemes. The word ''lexicon'' derives from Greek word (), neuter of () meaning 'of or fo ...

. With the absence of early written Welsh sources there is no way of knowing when these borrowings were incorporated into Welsh, and may date from a later post-Roman era when the language of literacy was still Latin. Borrowings include a few common words and word forms. For example, Welsh ''ffenestr'' is from Latin ''fenestra'', 'window'; ''llyfr'' is from ''liber'', 'book'; ''ysgrif'' is from ''scribo'', 'scribe'; and the suffix ''-wys'' found in Welsh folk names is derived from the Latin suffix ''-ēnsēs''. There are a few military terms, such as ''caer'' from Latin ''castra'', 'fortress'. ''Eglwys'', meaning 'church', is ultimately derived from the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

''klēros''.

Welsh kings would later use the authority of Magnus Maximus

Magnus Maximus (; cy, Macsen Wledig ; died 8 August 388) was Roman emperor of the Western Roman Empire from 383 to 388. He usurped the throne from emperor Gratian in 383 through negotiation with emperor Theodosius I.

He was made emperor in B ...

as the basis of their inherited political legitimacy. While imperial Roman entries in Welsh royal genealogies lack any historical foundation, they serve to illustrate the belief that legitimate royal authority began with Magnus Maximus. As told in ''The Dream of Emperor Maximus'', Maximus married a Briton, and their supposed children are given in genealogies as the ancestors of kings. Tracing ancestries back further, Roman emperors are listed as the sons of earlier Roman emperors, thus incorporating many famous Romans (e.g., Constantine the Great

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to convert to Christianity. Born in Naissus, Dacia Mediterran ...

) into the royal genealogies.

The kings of medieval Gwynedd

Gwynedd (; ) is a county and preserved county (latter with differing boundaries; includes the Isle of Anglesey) in the north-west of Wales. It shares borders with Powys, Conwy County Borough, Denbighshire, Anglesey over the Menai Strait, an ...

trace their origins to the northern British kingdom of Manaw Gododdin

Manaw Gododdin was the narrow coastal region on the south side of the Firth of Forth, part of the Brythonic-speaking Kingdom of Gododdin in the post-Roman Era. It is notable as the homeland of Cunedda prior to his conquest of North Wales, and ...

(located in modern Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

), and they also claim a connection to Roman authority in their genealogies ("Eternus son of Paternus son of Tacitus"). This claim may be either an independent one, or was perhaps an invention intended to rival the legitimacy of kings claiming descent from the historical Maximus.

Gwyn A. Williams argues that even at the time of the erection of Offa's Dyke

Offa's Dyke ( cy, Clawdd Offa) is a large linear earthwork that roughly follows the border between England and Wales. The structure is named after Offa, the Anglo-Saxon king of Mercia from AD 757 until 796, who is traditionally believed to ha ...

(that divided Wales from medieval England) the people to its west saw themselves as "Roman", citing the number of Latin inscriptions still being made into the 8th century.Williams, Gwyn A., ''The Welsh in their History'', published 1982 by Croom Helm,

Works cited

* * * * * * * * * * * * *References

External links

Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales

* ttps://www.britainexpress.com/attraction-map.htm?Country=Wales&Attraction=Roman Map of Roman localities in Wales (click on the arrows to get detailed information) {{Authority control Roman history of modern countries and territories w