Roman-British on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Roman Britain was the period in

Britain was known to the

Britain was known to the

The invasion force in 43 AD was led by

The invasion force in 43 AD was led by  The Catuvellauni and their allies were defeated in two battles: the first, assuming a Richborough landing, on the river Medway, the second on the

The Catuvellauni and their allies were defeated in two battles: the first, assuming a Richborough landing, on the river Medway, the second on the

A new crisis occurred at the beginning of Hadrian's reign (117): a rising in the north which was suppressed by

A new crisis occurred at the beginning of Hadrian's reign (117): a rising in the north which was suppressed by

An invasion of Caledonia led by Severus and probably numbering around 20,000 troops moved north in 208 or 209, crossing the Wall and passing through eastern Scotland on a route similar to that used by Agricola. Harried by punishing guerrilla raids by the northern tribes and slowed by an unforgiving terrain, Severus was unable to meet the Caledonians on a battlefield. The emperor's forces pushed north as far as the River Tay, but little appears to have been achieved by the invasion, as peace treaties were signed with the Caledonians. By 210 Severus had returned to York, and the frontier had once again become Hadrian's Wall. He assumed the title ' but the title meant little with regard to the unconquered north, which clearly remained outside the authority of the Empire. Almost immediately, another northern tribe, the Maeatae, went to war. Caracalla left with a

An invasion of Caledonia led by Severus and probably numbering around 20,000 troops moved north in 208 or 209, crossing the Wall and passing through eastern Scotland on a route similar to that used by Agricola. Harried by punishing guerrilla raids by the northern tribes and slowed by an unforgiving terrain, Severus was unable to meet the Caledonians on a battlefield. The emperor's forces pushed north as far as the River Tay, but little appears to have been achieved by the invasion, as peace treaties were signed with the Caledonians. By 210 Severus had returned to York, and the frontier had once again become Hadrian's Wall. He assumed the title ' but the title meant little with regard to the unconquered north, which clearly remained outside the authority of the Empire. Almost immediately, another northern tribe, the Maeatae, went to war. Caracalla left with a

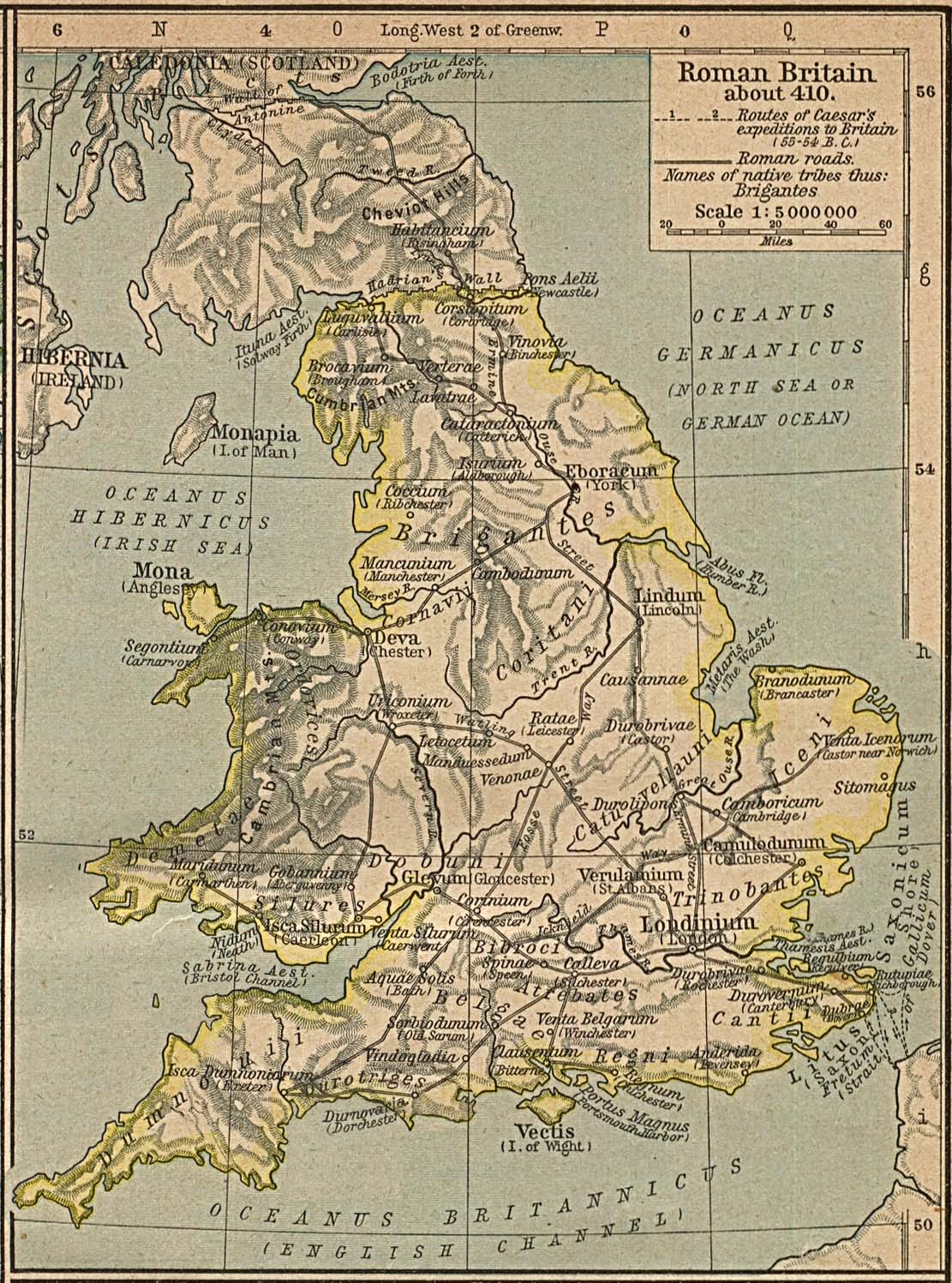

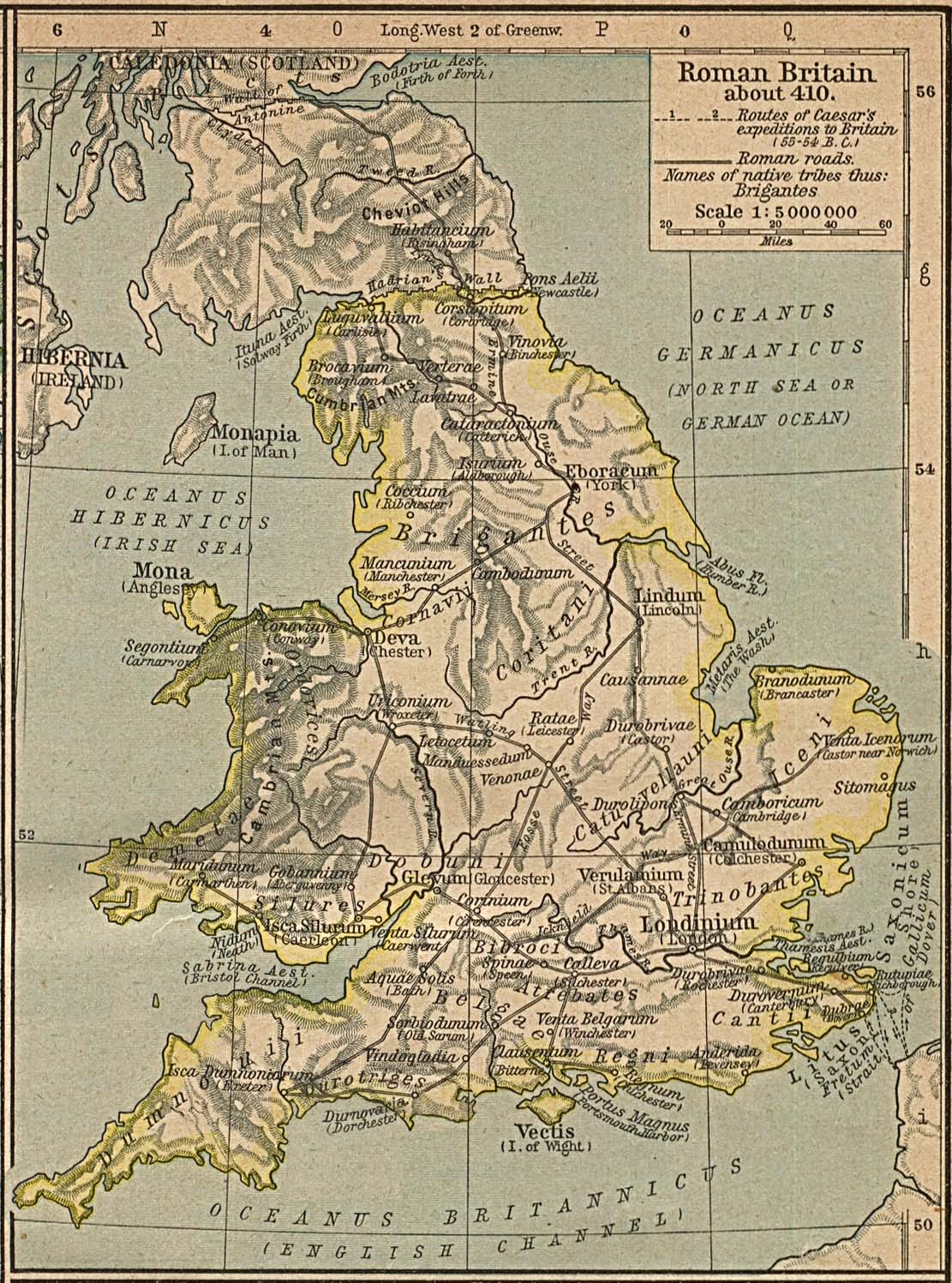

As part of Diocletian's reforms, the provinces of Roman Britain were organized as a

As part of Diocletian's reforms, the provinces of Roman Britain were organized as a

The Romans in Britain

– Information on the Romans in Britain, including everyday life

Roman Britain

– everything to do with Roman Britain, especially geographic, military, and administrative

The Roman Army and Navy in Britain

by Peter Green

Roman Britain

by Guy de la Bédoyère

Roman Britain at LacusCurtius

* by Kevin Flude

Roman Britain – History

Roman Colchester

Roman Wales RCAHMWThe Rural Settlement of Roman Britain

- database of excavated evidence for rural settlements {{Authority control 1st century in England 2nd century in England 3rd century in England 4th century in England 5th century in England States and territories established in the 40s States and territories disestablished in the 5th century * * 410 disestablishments

classical antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

when large parts of the island of Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It i ...

were under occupation

Occupation commonly refers to:

*Occupation (human activity), or job, one's role in society, often a regular activity performed for payment

*Occupation (protest), political demonstration by holding public or symbolic spaces

*Military occupation, th ...

by the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediter ...

. The occupation lasted from AD 43 to AD 410. During that time, the territory conquered was raised to the status of a Roman province

The Roman provinces (Latin: ''provincia'', pl. ''provinciae'') were the administrative regions of Ancient Rome outside Roman Italy that were controlled by the Romans under the Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire. Each province was rule ...

.

Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, ...

invaded Britain in 55 and 54 BC as part of his Gallic Wars

The Gallic Wars were waged between 58 and 50 BC by the Roman general Julius Caesar against the peoples of Gaul (present-day France, Belgium, Germany and Switzerland). Gallic, Germanic, and British tribes fought to defend their homel ...

. According to Caesar, the Britons

British people or Britons, also known colloquially as Brits, are the citizens of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the British Overseas Territories, and the Crown dependencies.: British nationality law governs mod ...

had been overrun or culturally assimilated by other Celtic tribes during the British Iron Age and had been aiding Caesar's enemies. He received tribute, installed the friendly king Mandubracius

Mandubracius or Mandubratius was a king of the Trinovantes of south-eastern Britain in the 1st century BC.

History

Mandubracius was the son of a Trinovantian king, named Imanuentius in some manuscripts of Julius Caesar's ''De Bello Gallico'', ...

over the Trinovantes

The Trinovantēs (Common Brittonic: *''Trinowantī'') or Trinobantes were one of the Celtic tribes of Pre-Roman Britain. Their territory was on the north side of the Thames estuary in current Essex, Hertfordshire and Suffolk, and included land ...

, and returned to Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

. Planned invasions under Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

were called off in 34, 27, and 25 BC. In 40 AD, Caligula assembled 200,000 men at the Channel on the continent, only to have them gather seashells ('' musculi'') according to Suetonius, perhaps as a symbolic gesture to proclaim Caligula's victory over the sea. Three years later, Claudius directed four legions to invade Britain and restore the exiled king Verica

Verica (early 1st century AD) was a British client king of the Roman Empire in the years preceding the Claudian invasion of 43 AD.

From his coinage, he appears to have been king of the, probably Belgic, Atrebates tribe and a son of Commius. Th ...

over the Atrebates. The Romans defeated the Catuvellauni

The Catuvellauni (Common Brittonic: *''Catu-wellaunī'', "war-chiefs") were a Celtic tribe or state of southeastern Britain before the Roman conquest, attested by inscriptions into the 4th century.

The fortunes of the Catuvellauni and their ...

, and then organized their conquests as the Province of Britain (). By 47 AD, the Romans held the lands southeast of the Fosse Way. Control over Wales was delayed by reverses and the effects of Boudica's uprising, but the Romans expanded steadily northward.

The conquest of Britain continued under command of Gnaeus Julius Agricola

Gnaeus Julius Agricola (; 13 June 40 – 23 August 93) was a Roman general and politician responsible for much of the Roman conquest of Britain. Born to a political family of senatorial rank, Agricola began his military career as a military tribu ...

(77–84), who expanded the Roman Empire as far as Caledonia. In mid-84 AD, Agricola faced the armies of the Caledonians, led by Calgacus, at the Battle of Mons Graupius

The Battle of Mons Graupius was, according to Tacitus, a Roman Empire, Roman military victory in what is now Scotland, taking place in AD 83 or, less probably, 84. The exact location of the battle is a matter of debate. Historians have long que ...

. Battle casualties were estimated by Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his two major works—the ...

to be upwards of 10,000 on the Caledonian side and about 360 on the Roman side. The bloodbath at Mons Graupius concluded the forty-year conquest of Britain, a period that possibly saw between 100,000 and 250,000 Britons killed. In the context of pre-industrial warfare and of a total population of Britain of 2 million, these are very high figures.

Under the 2nd-century emperors Hadrian and Antoninus Pius

Antoninus Pius ( Latin: ''Titus Aelius Hadrianus Antoninus Pius''; 19 September 86 – 7 March 161) was Roman emperor from 138 to 161. He was the fourth of the Five Good Emperors from the Nerva–Antonine dynasty.

Born into a senatori ...

, two walls were built to defend the Roman province from the Caledonians, whose realms in the Scottish Highlands

The Highlands ( sco, the Hielands; gd, a’ Ghàidhealtachd , 'the place of the Gaels') is a historical region of Scotland. Culturally, the Highlands and the Lowlands diverged from the Late Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowland S ...

were never controlled. Around 197 AD, the Severan Reforms

Lucius Septimius Severus (; 11 April 145 – 4 February 211) was Roman emperor from 193 to 211. He was born in Leptis Magna (present-day Al-Khums, Libya) in the Roman province of Africa. As a young man he advanced through the customary succe ...

divided Britain into two provinces: Britannia Superior and Britannia Inferior. During the Diocletian Reforms, at the end of the 3rd century, Britannia was divided into four provinces under the direction of a vicarius

''Vicarius'' is a Latin word, meaning ''substitute'' or ''deputy''. It is the root of the English word "vicar".

History

Originally, in ancient Rome, this office was equivalent to the later English " vice-" (as in "deputy"), used as part of th ...

, who administered the . A fifth province, Valentia, is attested in the later 4th century. For much of the later period of the Roman occupation, Britannia was subject to barbarian invasions and often came under the control of imperial usurpers and imperial pretenders. The final Roman withdrawal from Britain occurred around 410; the native kingdoms are considered to have formed Sub-Roman Britain after that.

Following the conquest of the Britons, a distinctive Romano-British culture emerged as the Romans introduced improved agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people t ...

, urban planning

Urban planning, also known as town planning, city planning, regional planning, or rural planning, is a technical and political process that is focused on the development and design of land use and the built environment, including air, water, ...

, industrial production, and architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and constructing building ...

. The Roman goddess Britannia

Britannia () is the national personification of Britain as a helmeted female warrior holding a trident and shield. An image first used in classical antiquity, the Latin ''Britannia'' was the name variously applied to the British Isles, Great ...

became the female personification of Britain. After the initial invasions, Roman historians Roman historiography stretches back to at least the 3rd century BC and was indebted to earlier Greek historiography. The Romans relied on previous models in the Greek tradition such as the works of Herodotus (c. 484 – 425 BC) and Thucydides (c. ...

generally only mention Britain in passing. Thus, most present knowledge derives from archaeological investigations and occasional epigraphic evidence lauding the Britannic achievements of an emperor

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereignty, sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), ...

. Roman citizens settled in Britain from many parts of the Empire.

History

Early contact

Britain was known to the

Britain was known to the Classical world

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

. The Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, oth ...

, the Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their histor ...

ns and the Carthaginians

The Punic people, or western Phoenicians, were a Semitic people in the Western Mediterranean who migrated from Tyre, Phoenicia to North Africa during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' – the Latin equivalent of the ...

traded for Cornish tin

Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn (from la, stannum) and atomic number 50. Tin is a silvery-coloured metal.

Tin is soft enough to be cut with little force and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, t ...

in the 4th century BC. The Greeks referred to the ', or "tin islands", and placed them near the west coast of Europe. The Carthaginian sailor Himilco is said to have visited the island in the 6th or 5th century BC and the Greek explorer Pytheas in the 4th. It was regarded as a place of mystery, with some writers refusing to believe it existed.

The first direct Roman contact was when Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, ...

undertook two expeditions in 55 and 54 BC, as part of his conquest of Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

, believing the Britons were helping the Gallic resistance. The first expedition was more a reconnaissance than a full invasion and gained a foothold on the coast of Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

but was unable to advance further because of storm damage to the ships and a lack of cavalry. Despite the military failure, it was a political success, with the Roman Senate

The Roman Senate ( la, Senātus Rōmānus) was a governing and advisory assembly in ancient Rome. It was one of the most enduring institutions in Roman history, being established in the first days of the city of Rome (traditionally founded in ...

declaring a 20-day public holiday in Rome to honour the unprecedented achievement of obtaining hostages from Britain and defeating Belgic tribes on returning to the continent.

The second invasion involved a substantially larger force and Caesar coerced or invited many of the native Celtic tribes to pay tribute and give hostages in return for peace. A friendly local king, Mandubracius

Mandubracius or Mandubratius was a king of the Trinovantes of south-eastern Britain in the 1st century BC.

History

Mandubracius was the son of a Trinovantian king, named Imanuentius in some manuscripts of Julius Caesar's ''De Bello Gallico'', ...

, was installed, and his rival, Cassivellaunus

Cassivellaunus was a historical Celtic Britons, British military leader who led the defence against Caesar's invasions of Britain, Julius Caesar's second expedition to Britain in 54 BC. He led an alliance of tribes against Ancient Rome, Roman for ...

, was brought to terms. Hostages were taken, but historians disagree over whether any tribute was paid after Caesar returned to Gaul.

Caesar conquered no territory and left no troops behind, but he established clients and brought Britain into Rome's sphere of influence. Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

planned invasions in 34, 27 and 25 BC, but circumstances were never favourable, and the relationship between Britain and Rome settled into one of diplomacy and trade. Strabo, writing late in Augustus's reign, claimed that taxes on trade brought in more annual revenue than any conquest could. Archaeology shows that there was an increase in imported luxury goods in southeastern Britain. Strabo also mentions British kings who sent embassies to Augustus, and Augustus's own ' refers to two British kings he received as refugees. When some of Tiberius

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus (; 16 November 42 BC – 16 March AD 37) was the second Roman emperor. He reigned from AD 14 until 37, succeeding his stepfather, the first Roman emperor Augustus. Tiberius was born in Rome in 42 BC. His father ...

's ships were carried to Britain in a storm during his campaigns in Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

in 16 AD, they came back with tales of monsters.

Rome appears to have encouraged a balance of power in southern Britain, supporting two powerful kingdoms: the Catuvellauni

The Catuvellauni (Common Brittonic: *''Catu-wellaunī'', "war-chiefs") were a Celtic tribe or state of southeastern Britain before the Roman conquest, attested by inscriptions into the 4th century.

The fortunes of the Catuvellauni and their ...

, ruled by the descendants of Tasciovanus

Tasciovanus (died c. 9 AD) was a historical king of the Catuvellauni tribe before the Roman conquest of Britain.

History

Tasciovanus is known only through numismatic evidence. He appears to have become king of the Catuvellauni c. 20 BC, ruling ...

, and the Atrebates, ruled by the descendants of Commius

Commius (Commios, Comius, Comnios) was a king of the Belgic nation of the Atrebates, initially in Gaul, then in Britain, in the 1st century BC.

Ally of Caesar

When Julius Caesar conquered the Atrebates in Gaul in 57 BC, as recounted in his ...

. This policy was followed until 39 or 40 AD, when Caligula received an exiled member of the Catuvellaunian dynasty and planned an invasion of Britain that collapsed in farcical circumstances before it left Gaul. When Claudius successfully invaded in 43 AD, it was in aid of another fugitive British ruler, Verica

Verica (early 1st century AD) was a British client king of the Roman Empire in the years preceding the Claudian invasion of 43 AD.

From his coinage, he appears to have been king of the, probably Belgic, Atrebates tribe and a son of Commius. Th ...

of the Atrebates.

Roman invasion

The invasion force in 43 AD was led by

The invasion force in 43 AD was led by Aulus Plautius

Aulus Plautius was a Roman politician and general of the mid-1st century. He began the Roman conquest of Britain in 43, and became the first governor of the new province, serving from 43 to 46 CE.

Career

Little is known of Aulus Plautius's e ...

, but it is unclear how many legions were sent. The ', commanded by future emperor Vespasian

Vespasian (; la, Vespasianus ; 17 November AD 9 – 23/24 June 79) was a Roman emperor who reigned from AD 69 to 79. The fourth and last emperor who reigned in the Year of the Four Emperors, he founded the Flavian dynasty that ruled the Empi ...

, was the only one directly attested to have taken part. The ', the ' (later styled ') and the ' (later styled ') are known to have served during the Boudican Revolt of 60/61, and were probably there since the initial invasion. This is not certain because the Roman army

The Roman army (Latin: ) was the armed forces deployed by the Romans throughout the duration of Ancient Rome, from the Roman Kingdom (c. 500 BC) to the Roman Republic (500–31 BC) and the Roman Empire (31 BC–395 AD), and its medieval contin ...

was flexible, with units being moved around whenever necessary. The ' may have been permanently stationed, with records showing it at Eboracum

Eboracum () was a fort and later a city in the Roman province of Britannia. In its prime it was the largest town in northern Britain and a provincial capital. The site remained occupied after the decline of the Western Roman Empire and ultimat ...

(York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

) in 71 and on a building inscription there dated 108, before being destroyed in the east of the Empire, possibly during the Bar Kokhba revolt.

The invasion was delayed by a troop mutiny until an imperial freedman persuaded them to overcome their fear of crossing the Ocean

The ocean (also the sea or the world ocean) is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of the surface of Earth and contains 97% of Earth's water. An ocean can also refer to any of the large bodies of water into which the wo ...

and campaigning beyond the limits of the known world. They sailed in three divisions, and probably landed at Richborough

Richborough () is a settlement north of Sandwich on the east coast of the county of Kent, England. Richborough lies close to the Isle of Thanet. The population of the settlement is included in the civil parish of Ash.

Although now some dist ...

in Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

; at least part of the force may have landed near Fishbourne, West Sussex

Fishbourne is a village and civil parish in the Chichester District of West Sussex, England and is situated two miles () west of Chichester.

The Anglican parish of Fishbourne, formerly New Fishbourne, is in the Diocese of Chichester. The populat ...

.

The Catuvellauni and their allies were defeated in two battles: the first, assuming a Richborough landing, on the river Medway, the second on the

The Catuvellauni and their allies were defeated in two battles: the first, assuming a Richborough landing, on the river Medway, the second on the river Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the R ...

. One of their leaders, Togodumnus

Togodumnus (died AD 43) was king of the British Catuvellauni tribe, whose capital was at St. Albans, at the time of the Roman conquest. He can probably be identified with the legendary British king Guiderius.

He is usually thought to have led t ...

, was killed, but his brother Caratacus

Caratacus (Brythonic ''*Caratācos'', Middle Welsh ''Caratawc''; Welsh ''Caradog''; Breton ''Karadeg''; Greek ''Καράτακος''; variants Latin ''Caractacus'', Greek ''Καρτάκης'') was a 1st-century AD British chieftain of the ...

survived to continue resistance elsewhere. Plautius halted at the Thames and sent for Claudius, who arrived with reinforcements, including artillery and elephants, for the final march to the Catuvellaunian capital, Camulodunum

Camulodunum (; la, ), the Ancient Roman name for what is now Colchester in Essex, was an important castrum and city in Roman Britain, and the first capital of the province. A temporary "strapline" in the 1960s identifying it as the "oldest re ...

(Colchester

Colchester ( ) is a city in Essex, in the East of England. It had a population of 122,000 in 2011. The demonym is Colcestrian.

Colchester occupies the site of Camulodunum, the first major city in Roman Britain and its first capital. Colch ...

). Vespasian subdued the southwest, Cogidubnus

Tiberius Claudius Cogidubnus (or Togidubnus, Togidumnus or similar; see naming difficulties) was a 1st-century king of the Regni or Regnenses tribe in early Roman Britain.

Chichester and the nearby Roman villa at Fishbourne, believed by some t ...

was set up as a friendly king of several territories, and treaties were made with tribes outside direct Roman control.

Establishment of Roman rule

After capturing the south of the island, the Romans turned their attention to what is nowWales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the Bristol Channel to the south. It had a population in ...

. The Silures, Ordovices and Deceangli

The Deceangli or Deceangi (Welsh: Tegeingl) were one of the Celtic tribes living in Britain, prior to the Roman invasion of the island. The tribe lived in the region near the modern city of Chester but it is uncertain whether their territory co ...

remained implacably opposed to the invaders and for the first few decades were the focus of Roman military attention, despite occasional minor revolts among Roman allies like the Brigantes and the Iceni

The Iceni ( , ) or Eceni were a Brittonic tribe of eastern Britain during the Iron Age and early Roman era. Their territory included present-day Norfolk and parts of Suffolk and Cambridgeshire, and bordered the area of the Corieltauvi to the we ...

. The Silures were led by Caratacus

Caratacus (Brythonic ''*Caratācos'', Middle Welsh ''Caratawc''; Welsh ''Caradog''; Breton ''Karadeg''; Greek ''Καράτακος''; variants Latin ''Caractacus'', Greek ''Καρτάκης'') was a 1st-century AD British chieftain of the ...

, and he carried out an effective guerrilla campaign against Governor Publius Ostorius Scapula

Publius Ostorius Scapula standing at the terrace of the Roman Baths (Bath)

Publius Ostorius Scapula (died 52) was a Roman statesman and general who governed Britain from 47 until his death, and was responsible for the defeat and capture of Ca ...

. Finally, in 51, Ostorius lured Caratacus into a set-piece battle and defeated him. The British leader sought refuge among the Brigantes, but their queen, Cartimandua

Cartimandua or Cartismandua (reigned ) was a 1st-century queen of the Brigantes, a Celtic people living in what is now northern England. She came to power around the time of the Roman conquest of Britain, and formed a large tribal agglomeration ...

, proved her loyalty by surrendering him to the Romans. He was brought as a captive to Rome, where a dignified speech he made during Claudius's triumph persuaded the emperor to spare his life. The Silures were still not pacified, and Cartimandua's ex-husband Venutius

Venutius was a 1st-century king of the Brigantes in northern Britain at the time of the Roman conquest. Some have suggested he may have belonged to the Carvetii, a tribe that probably formed part of the Brigantes confederation.

History first b ...

replaced Caratacus as the most prominent leader of British resistance.

On Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68), was the fifth Roman emperor and final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 unti ...

's accession Roman Britain extended as far north as Lindum

Lindum Colonia was the Latin name for the settlement which is now the City of Lincoln in Lincolnshire. It was founded as a Roman Legionary Fortress during the reign of the Emperor Nero (58–68 AD) or possibly later. Evidence from Roman tomb ...

. Gaius Suetonius Paulinus, the conqueror of Mauretania (modern day Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

and Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria t ...

), then became governor of Britain, and in 60 and 61 he moved against Mona (Anglesey

Anglesey (; cy, (Ynys) Môn ) is an island off the north-west coast of Wales. It forms a principal area known as the Isle of Anglesey, that includes Holy Island across the narrow Cymyran Strait and some islets and skerries. Anglesey island ...

) to settle accounts with Druidism once and for all. Paulinus led his army across the Menai Strait and massacred the Druids and burnt their sacred groves.

While Paulinus was campaigning in Mona, the southeast of Britain rose in revolt under the leadership of Boudica. She was the widow of the recently deceased king of the Iceni, Prasutagus. The Roman historian Tacitus reports that Prasutagus had left a will leaving half his kingdom to Nero in the hope that the remainder would be left untouched. He was wrong. When his will was enforced, Rome responded by violently seizing the tribe's lands in full. Boudica protested. In consequence, Rome punished her and her daughters by flogging and rape. In response, the Iceni, joined by the Trinovantes

The Trinovantēs (Common Brittonic: *''Trinowantī'') or Trinobantes were one of the Celtic tribes of Pre-Roman Britain. Their territory was on the north side of the Thames estuary in current Essex, Hertfordshire and Suffolk, and included land ...

, destroyed the Roman colony at Camulodunum (Colchester

Colchester ( ) is a city in Essex, in the East of England. It had a population of 122,000 in 2011. The demonym is Colcestrian.

Colchester occupies the site of Camulodunum, the first major city in Roman Britain and its first capital. Colch ...

) and routed the part of the IXth Legion that was sent to relieve it. Paulinus rode to London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

(then called Londinium), the rebels' next target, but concluded it could not be defended. Abandoned, it was destroyed, as was Verulamium

Verulamium was a town in Roman Britain. It was sited southwest of the modern city of St Albans in Hertfordshire, England. A large portion of the Roman city remains unexcavated, being now park and agricultural land, though much has been built upon ...

(St. Albans). Between seventy and eighty thousand people are said to have been killed in the three cities. But Paulinus regrouped with two of the three legions still available to him, chose a battlefield, and, despite being outnumbered by more than twenty to one, defeated the rebels in the Battle of Watling Street

The Boudican revolt was an armed uprising by native Celtic tribes against the Roman Empire. It took place c. 60–61 AD in the Roman province of Britain, and was led by Boudica, the Queen of the Iceni. The uprising was motivated by the Romans' ...

. Boudica died not long afterwards, by self-administered poison or by illness. During this time, the Emperor Nero considered withdrawing Roman forces from Britain altogether.

There was further turmoil in 69, the "Year of the Four Emperors

The Year of the Four Emperors, AD 69, was the first civil war of the Roman Empire, during which four emperors ruled in succession: Galba, Otho, Vitellius, and Vespasian. It is considered an important interval, marking the transition from the ...

". As civil war raged in Rome, weak governors were unable to control the legions in Britain, and Venutius of the Brigantes seized his chance. The Romans had previously defended Cartimandua against him, but this time were unable to do so. Cartimandua was evacuated, and Venutius was left in control of the north of the country. After Vespasian secured the empire, his first two appointments as governor, Quintus Petillius Cerialis and Sextus Julius Frontinus, took on the task of subduing the Brigantes and Silures respectively. Frontinus extended Roman rule to all of South Wales, and initiated exploitation of the mineral resources, such as the gold mines

Gold mining is the extraction of gold resources by mining. Historically, mining gold from alluvial deposits used manual separation processes, such as gold panning. However, with the expansion of gold mining to ores that are not on the surface, ...

at Dolaucothi

The Dolaucothi Gold Mines (; cy, Mwynfeydd Aur Dolaucothi) (), also known as the Ogofau Gold Mine, are ancient Roman surface and underground mines located in the valley of the River Cothi, near Pumsaint, Carmarthenshire, Wales. The gold mi ...

.

In the following years, the Romans conquered more of the island, increasing the size of Roman Britain. Governor Gnaeus Julius Agricola

Gnaeus Julius Agricola (; 13 June 40 – 23 August 93) was a Roman general and politician responsible for much of the Roman conquest of Britain. Born to a political family of senatorial rank, Agricola began his military career as a military tribu ...

, father-in-law to the historian Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his two major works—the ...

, conquered the Ordovices in 78. With the ' legion, Agricola defeated the Caledonians in 84 at the Battle of Mons Graupius

The Battle of Mons Graupius was, according to Tacitus, a Roman Empire, Roman military victory in what is now Scotland, taking place in AD 83 or, less probably, 84. The exact location of the battle is a matter of debate. Historians have long que ...

, in north-east Scotland. This was the high-water mark of Roman territory in Britain: shortly after his victory, Agricola was recalled from Britain back to Rome, and the Romans initially retired to a more defensible line along the Forth–Clyde Clyde may refer to:

People

* Clyde (given name)

* Clyde (surname)

Places

For townships see also Clyde Township

Australia

* Clyde, New South Wales

* Clyde, Victoria

* Clyde River, New South Wales

Canada

* Clyde, Alberta

* Clyde, Ontario, a tow ...

isthmus, freeing soldiers badly needed along other frontiers.

For much of the history of Roman Britain, a large number of soldiers were garrisoned on the island. This required that the emperor station a trusted senior man as governor of the province. As a result, many future emperors served as governors or legates in this province, including Vespasian

Vespasian (; la, Vespasianus ; 17 November AD 9 – 23/24 June 79) was a Roman emperor who reigned from AD 69 to 79. The fourth and last emperor who reigned in the Year of the Four Emperors, he founded the Flavian dynasty that ruled the Empi ...

, Pertinax

Publius Helvius Pertinax (; 1 August 126 – 28 March 193) was Roman emperor for the first three months of 193. He succeeded Commodus to become the first emperor during the tumultuous Year of the Five Emperors.

Born the son of a freed slav ...

, and Gordian I.

Occupation of and retreat from southern Scotland

There is no historical source describing the decades that followed Agricola's recall. Even the name of his replacement is unknown. Archaeology has shown that someRoman forts

In the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire, the Latin word ''castrum'', plural ''castra'', was a military-related term.

In Latin usage, the singular form ''castrum'' meant 'fort', while the plural form ''castra'' meant 'camp'. The singular and ...

south of the Forth–Clyde isthmus were rebuilt and enlarged; others appear to have been abandoned. By 87 the frontier had been consolidated on the Stanegate

The Stanegate (meaning "stone road" in Northumbrian dialect) was an important Roman road built in what is now northern England. It linked many forts including two that guarded important river crossings: Corstopitum (Corbridge) on the River Ty ...

. Roman coins and pottery have been found circulating at native settlement sites in the Scottish Lowlands in the years before 100, indicating growing Romanisation

Romanization or romanisation, in linguistics, is the conversion of text from a different writing system to the Roman (Latin) script, or a system for doing so. Methods of romanization include transliteration, for representing written text, and ...

. Some of the most important sources for this era are the writing tablets from the fort at Vindolanda

Vindolanda was a Roman auxiliary fort ('' castrum'') just south of Hadrian's Wall in northern England, which it originally pre-dated.British windo- 'fair, white, blessed', landa 'enclosure/meadow/prairie/grassy plain' (the modern Welsh word ...

in Northumberland

Northumberland () is a county in Northern England, one of two counties in England which border with Scotland. Notable landmarks in the county include Alnwick Castle, Bamburgh Castle, Hadrian's Wall and Hexham Abbey.

It is bordered by land ...

, mostly dating to 90–110. These tablets provide evidence for the operation of a Roman fort at the edge of the Roman Empire, where officers' wives maintained polite society while merchants, hauliers and military personnel kept the fort operational and supplied.

Around 105 there appears to have been a serious setback at the hands of the tribes of the Picts

The Picts were a group of peoples who lived in what is now northern and eastern Scotland (north of the Firth of Forth) during Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Where they lived and what their culture was like can be inferred from e ...

: several Roman forts were destroyed by fire, with human remains and damaged armour at '' Trimontium'' (at modern Newstead, in SE Scotland) indicating hostilities at least at that site. There is also circumstantial evidence that auxiliary reinforcements were sent from Germany, and an unnamed British war of the period is mentioned on the gravestone of a tribune

Tribune () was the title of various elected officials in ancient Rome. The two most important were the tribunes of the plebs and the military tribunes. For most of Roman history, a college of ten tribunes of the plebs acted as a check on th ...

of Cyrene. Trajan's Dacian Wars

The Dacian Wars (101–102, 105–106) were two military campaigns fought between the Roman Empire and Dacia during Emperor Trajan's rule. The conflicts were triggered by the constant Dacian threat on the Danubian province of Moesia and also b ...

may have led to troop reductions in the area or even total withdrawal followed by slighting of the forts by the Picts rather than an unrecorded military defeat. The Romans were also in the habit of destroying their own forts during an orderly withdrawal, in order to deny resources to an enemy. In either case, the frontier probably moved south to the line of the Stanegate

The Stanegate (meaning "stone road" in Northumbrian dialect) was an important Roman road built in what is now northern England. It linked many forts including two that guarded important river crossings: Corstopitum (Corbridge) on the River Ty ...

at the Solway– Tyne isthmus around this time.

A new crisis occurred at the beginning of Hadrian's reign (117): a rising in the north which was suppressed by

A new crisis occurred at the beginning of Hadrian's reign (117): a rising in the north which was suppressed by Quintus Pompeius Falco

Quintus Pompeius Falco (c. 70after 140 AD) was a Roman senator and general of the early 2nd century AD. He was governor of several provinces, most notably Roman Britain, where he hosted a visit to the province by the Emperor Hadrian in the last ...

. When Hadrian reached Britannia on his famous tour of the Roman provinces around 120, he directed an extensive defensive wall, known to posterity as Hadrian's Wall, to be built close to the line of the Stanegate frontier. Hadrian appointed Aulus Platorius Nepos

Aulus Platorius Nepos was a Roman senator who held a number of appointments in the imperial service, including the governorship of Britain. He was suffect consul succeeding the ''consul posterior'' Publius Dasumius Rusticus as the colleague of ...

as governor to undertake this work who brought the ' legion with him from '. This replaced the famous ', whose disappearance has been much discussed. Archaeology indicates considerable political instability in Scotland during the first half of the 2nd century, and the shifting frontier at this time should be seen in this context.

In the reign of Antoninus Pius

Antoninus Pius ( Latin: ''Titus Aelius Hadrianus Antoninus Pius''; 19 September 86 – 7 March 161) was Roman emperor from 138 to 161. He was the fourth of the Five Good Emperors from the Nerva–Antonine dynasty.

Born into a senatori ...

(138–161) the Hadrianic border was briefly extended north to the Forth–Clyde isthmus, where the Antonine Wall was built around 142 following the military reoccupation of the Scottish lowlands by a new governor, Quintus Lollius Urbicus

Quintus Lollius Urbicus was a Numidian Berber governor of Roman Britain between the years 139 and 142, during the reign of the Emperor Antoninus Pius. He is named in the ''Historia Augusta'', although it is not entirely historical, and his name ...

.

The first Antonine occupation of Scotland ended as a result of a further crisis in 155–157, when the Brigantes revolted. With limited options to despatch reinforcements, the Romans moved their troops south, and this rising was suppressed by Governor Gnaeus Julius Verus

Gnaeus Julius Verus was Roman senator and general of the mid-2nd century AD. He was suffect consul, and governed several important imperial provinces: Germania Inferior, Britain, and Syria.

Life

Verus came from Aequum in Dalmatia; this has ...

. Within a year the Antonine Wall was recaptured, but by 163 or 164 it was abandoned. The second occupation was probably connected with Antoninus's undertakings to protect the Votadini or his pride in enlarging the empire, since the retreat to the Hadrianic frontier occurred not long after his death when a more objective strategic assessment of the benefits of the Antonine Wall could be made. The Romans did not entirely withdraw from Scotland at this time: the large fort at Newstead was maintained along with seven smaller outposts until at least 180.

During the twenty-year period following the reversion of the frontier to Hadrian's Wall in 163/4, Rome was concerned with continental issues, primarily problems in the Danubian provinces. Increasing numbers of hoards of buried coins in Britain at this time indicate that peace was not entirely achieved. Sufficient Roman silver has been found in Scotland to suggest more than ordinary trade, and it is likely that the Romans were reinforcing treaty agreements by paying tribute to their implacable enemies, the Picts

The Picts were a group of peoples who lived in what is now northern and eastern Scotland (north of the Firth of Forth) during Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Where they lived and what their culture was like can be inferred from e ...

.

In 175, a large force of Sarmatian

The Sarmatians (; grc, Σαρμαται, Sarmatai; Latin: ) were a large confederation of ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic peoples of classical antiquity who dominated the Pontic steppe from about the 3rd century BC to the 4th cen ...

cavalry, consisting of 5,500 men, arrived in Britannia, probably to reinforce troops fighting unrecorded uprisings. In 180, Hadrian's Wall was breached by the Picts and the commanding officer or governor was killed there in what Cassius Dio

Lucius Cassius Dio (), also known as Dio Cassius ( ), was a Roman historian and senator of maternal Greek origin. He published 80 volumes of the history on ancient Rome, beginning with the arrival of Aeneas in Italy. The volumes documented the ...

described as the most serious war of the reign of Commodus. Ulpius Marcellus

Ulpius Marcellus was a Roman consular governor of Britannia who returned there as general of the later 2nd century.

Ulpius Marcellus is recorded as governor of Roman Britain in an inscription of 176–80, and apparently returned to Rome after a te ...

was sent as replacement governor and by 184 he had won a new peace, only to be faced with a mutiny from his own troops. Unhappy with Marcellus's strictness, they tried to elect a legate named Priscus

Priscus of Panium (; el, Πρίσκος; 410s AD/420s AD-after 472 AD) was a 5th-century Eastern Roman diplomat and Greek historian and rhetorician (or sophist)...: "For information about Attila, his court and the organization of life general ...

as usurper governor; he refused, but Marcellus was lucky to leave the province alive. The Roman army in Britannia continued its insubordination: they sent a delegation of 1,500 to Rome to demand the execution of Tigidius Perennis

Sextus Tigidius Perennis (died 185) served as Praetorian Prefect under the Roman emperor Commodus. Perennis exercised an outsized influence over Commodus and was the effective ruler of the Roman Empire. In 185, Perennis was implicated in a plot ...

, a Praetorian prefect who they felt had earlier wronged them by posting lowly equites to legate ranks in Britannia. Commodus met the party outside Rome and agreed to have Perennis killed, but this only made them feel more secure in their mutiny.

The future emperor Pertinax

Publius Helvius Pertinax (; 1 August 126 – 28 March 193) was Roman emperor for the first three months of 193. He succeeded Commodus to become the first emperor during the tumultuous Year of the Five Emperors.

Born the son of a freed slav ...

was sent to Britannia to quell the mutiny and was initially successful in regaining control, but a riot broke out among the troops. Pertinax was attacked and left for dead, and asked to be recalled to Rome, where he briefly succeeded Commodus as emperor in 192.

3rd century

The death of Commodus put into motion a series of events which eventually led to civil war. Following the short reign of Pertinax, several rivals for the emperorship emerged, includingSeptimius Severus

Lucius Septimius Severus (; 11 April 145 – 4 February 211) was Roman emperor from 193 to 211. He was born in Leptis Magna (present-day Al-Khums, Libya) in the Roman province of Africa. As a young man he advanced through the customary suc ...

and Clodius Albinus

Decimus Clodius Albinus ( 150 – 19 February 197) was a Roman imperial pretender between 193 and 197. He was proclaimed emperor by the legions in Britain and Hispania (the Iberian Peninsula, comprising modern Spain and Portugal) after the murder ...

. The latter was the new governor of Britannia, and had seemingly won the natives over after their earlier rebellions; he also controlled three legions, making him a potentially significant claimant. His sometime rival Severus promised him the title of Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

in return for Albinus's support against Pescennius Niger in the east. Once Niger was neutralised, Severus turned on his ally in Britannia; it is likely that Albinus saw he would be the next target and was already preparing for war.

Albinus crossed to Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

in 195, where the provinces were also sympathetic to him, and set up at Lugdunum

Lugdunum (also spelled Lugudunum, ; modern Lyon, France) was an important Roman city in Gaul, established on the current site of Lyon. The Roman city was founded in 43 BC by Lucius Munatius Plancus, but continued an existing Gallic settle ...

. Severus arrived in February 196, and the ensuing battle was decisive. Albinus came close to victory, but Severus's reinforcements won the day, and the British governor committed suicide. Severus soon purged Albinus's sympathisers and perhaps confiscated large tracts of land in Britain as punishment. Albinus had demonstrated the major problem posed by Roman Britain. In order to maintain security, the province required the presence of three legions, but command of these forces provided an ideal power base for ambitious rivals. Deploying those legions elsewhere would strip the island of its garrison, leaving the province defenceless against uprisings by the native Celtic tribes and against invasion by the Picts

The Picts were a group of peoples who lived in what is now northern and eastern Scotland (north of the Firth of Forth) during Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Where they lived and what their culture was like can be inferred from e ...

and Scots.

The traditional view is that northern Britain descended into anarchy during Albinus's absence. Cassius Dio records that the new Governor, Virius Lupus

Virius Lupus ( – after 205) (possibly Lucius Virius Lupus) was a Roman soldier and politician of the late 2nd and early 3rd century.

Biography

Virius Lupus was the first member of the ''gens Virii'' to attain high office in the Roman Em ...

, was obliged to buy peace from a fractious northern tribe known as the Maeatae

The Maeatae were a confederation of tribes that probably lived beyond the Antonine Wall in Roman Britain.

The historical sources are vague as to the exact region they inhabited, but an association is thought to be indicated in the names of two h ...

. The succession of militarily distinguished governors who were subsequently appointed suggests that enemies of Rome were posing a difficult challenge, and Lucius Alfenus Senecio's report to Rome in 207 describes barbarians "rebelling, over-running the land, taking loot and creating destruction". In order to rebel, of course, one must be a subject – the Maeatae clearly did not consider themselves such. Senecio requested either reinforcements or an Imperial expedition, and Severus chose the latter, despite being 62 years old. Archaeological evidence shows that Senecio had been rebuilding the defences of Hadrian's Wall and the forts beyond it, and Severus's arrival in Britain prompted the enemy tribes to sue for peace immediately. The emperor had not come all that way to leave without a victory, and it is likely that he wished to provide his teenage sons Caracalla

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (born Lucius Septimius Bassianus, 4 April 188 – 8 April 217), better known by his nickname "Caracalla" () was Roman emperor from 198 to 217. He was a member of the Severan dynasty, the elder son of Emperor S ...

and Geta

Geta may refer to:

Places

*Geta (woreda), a woreda in Ethiopia's Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples' Region

*Geta, Åland, a municipality in Finland

*Geta, Nepal, a town in Attariya Municipality, Kailali District, Seti Zone, Nepal

*Get� ...

with first-hand experience of controlling a hostile barbarian land.

An invasion of Caledonia led by Severus and probably numbering around 20,000 troops moved north in 208 or 209, crossing the Wall and passing through eastern Scotland on a route similar to that used by Agricola. Harried by punishing guerrilla raids by the northern tribes and slowed by an unforgiving terrain, Severus was unable to meet the Caledonians on a battlefield. The emperor's forces pushed north as far as the River Tay, but little appears to have been achieved by the invasion, as peace treaties were signed with the Caledonians. By 210 Severus had returned to York, and the frontier had once again become Hadrian's Wall. He assumed the title ' but the title meant little with regard to the unconquered north, which clearly remained outside the authority of the Empire. Almost immediately, another northern tribe, the Maeatae, went to war. Caracalla left with a

An invasion of Caledonia led by Severus and probably numbering around 20,000 troops moved north in 208 or 209, crossing the Wall and passing through eastern Scotland on a route similar to that used by Agricola. Harried by punishing guerrilla raids by the northern tribes and slowed by an unforgiving terrain, Severus was unable to meet the Caledonians on a battlefield. The emperor's forces pushed north as far as the River Tay, but little appears to have been achieved by the invasion, as peace treaties were signed with the Caledonians. By 210 Severus had returned to York, and the frontier had once again become Hadrian's Wall. He assumed the title ' but the title meant little with regard to the unconquered north, which clearly remained outside the authority of the Empire. Almost immediately, another northern tribe, the Maeatae, went to war. Caracalla left with a punitive expedition

A punitive expedition is a military journey undertaken to punish a political entity or any group of people outside the borders of the punishing state or union. It is usually undertaken in response to perceived disobedient or morally wrong beh ...

, but by the following year his ailing father had died and he and his brother left the province to press their claim to the throne.

As one of his last acts, Severus tried to solve the problem of powerful and rebellious governors in Britain by dividing the province into ' and '. This kept the potential for rebellion in check for almost a century. Historical sources provide little information on the following decades, a period known as the Long Peace. Even so, the number of buried hoards found from this period rises, suggesting continuing unrest. A string of forts were built along the coast of southern Britain to control piracy; and over the following hundred years they increased in number, becoming the Saxon Shore Forts

The Saxon Shore ( la, litus Saxonicum) was a military command of the late Roman Empire, consisting of a series of fortifications on both sides of the Channel. It was established in the late 3rd century and was led by the "Count of the Saxon Sho ...

.

During the middle of the 3rd century, the Roman Empire was convulsed by barbarian invasions, rebellions and new imperial pretenders. Britannia apparently avoided these troubles, but increasing inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reduct ...

had its economic effect. In 259 a so-called Gallic Empire was established when Postumus

Marcus Cassianius Latinius Postumus was a Roman commander of Batavian origin, who ruled as Emperor of the splinter state of the Roman Empire known to modern historians as the Gallic Empire. The Roman army in Gaul threw off its allegiance to Ga ...

rebelled against Gallienus

Publius Licinius Egnatius Gallienus (; c. 218 – September 268) was Roman emperor with his father Valerian from 253 to 260 and alone from 260 to 268. He ruled during the Crisis of the Third Century that nearly caused the collapse of the empi ...

. Britannia was part of this until 274 when Aurelian reunited the empire.

Around the year 280, a half-British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

officer named Bonosus was in command of the Roman's Rhenish fleet when the Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

managed to burn it at anchor. To avoid punishment, he proclaimed himself emperor at Colonia Agrippina

Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium was the Roman colony in the Rhineland from which the city of Cologne, now in Germany, developed.

It was usually called ''Colonia'' (colony) and was the capital of the Roman province of Germania Inferior and t ...

(Cologne

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 million inhabitants in the city proper and 3.6 millio ...

) but was crushed by Marcus Aurelius Probus

Marcus Aurelius Probus (; 230–235 – September 282) was Roman emperor from 276 to 282. Probus was an active and successful general as well as a conscientious administrator, and in his reign of six years he secured prosperity for the inner pr ...

. Soon afterwards, an unnamed governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

of one of the British provinces also attempted an uprising. Probus put it down by sending irregular troops of Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The Vandals migrated to the area betw ...

and Burgundians across the Channel.

The Carausian Revolt led to a short-lived Britannic Empire from 286 to 296. Carausius was a Menapian

The Menapii were a Belgic tribe dwelling near the North Sea, around present-day Cassel, during the Iron Age and the Roman period.

Name Attestations

They are mentioned as ''Menapii'' by Caesar (mid-1st c. BC) and Orosius (early 5th c. AD), ...

naval commander of the Britannic fleet; he revolted upon learning of a death sentence ordered by the emperor Maximian on charges of having abetted Frankish

Frankish may refer to:

* Franks, a Germanic tribe and their culture

** Frankish language or its modern descendants, Franconian languages

* Francia, a post-Roman state in France and Germany

* East Francia, the successor state to Francia in Germany ...

and Saxon pirates and having embezzled recovered treasure. He consolidated control over all the provinces of Britain and some of northern Gaul while Maximian dealt with other uprisings. An invasion in 288 failed to unseat him and an uneasy peace ensued, with Carausius issuing coins and inviting official recognition. In 293, the junior emperor Constantius Chlorus

Flavius Valerius Constantius "Chlorus" ( – 25 July 306), also called Constantius I, was Roman emperor from 305 to 306. He was one of the four original members of the Tetrarchy established by Diocletian, first serving as caesar from 293 ...

launched a second offensive, besieging the rebel port of Gesoriacum (Boulogne-sur-Mer

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; pcd, Boulonne-su-Mér; nl, Bonen; la, Gesoriacum or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Northern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department of Pas-de-Calais. Boulogne lies on the C ...

) by land and sea. After it fell, Constantius attacked Carausius's other Gallic holdings and Frankish allies and Carausius was usurped by his treasurer, Allectus. Julius Asclepiodotus Julius Asclepiodotus was a Roman praetorian prefect who, according to the ''Historia Augusta'', served under the emperors Aurelian, Probus and Diocletian, and was consul in 292. In 296, he assisted the western Caesar Constantius Chlorus in re-establ ...

landed an invasion fleet near Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

and defeated Allectus in a land battle.

Diocletian's reforms

As part of Diocletian's reforms, the provinces of Roman Britain were organized as a

As part of Diocletian's reforms, the provinces of Roman Britain were organized as a diocese

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associa ...

governed by a ''vicarius

''Vicarius'' is a Latin word, meaning ''substitute'' or ''deputy''. It is the root of the English word "vicar".

History

Originally, in ancient Rome, this office was equivalent to the later English " vice-" (as in "deputy"), used as part of th ...

'' under a praetorian prefect who, from 318 to 331, was Junius Bassus who was based at Augusta Treverorum

Trier in Rhineland-Palatinate, whose history dates to the Roman Empire, is often claimed to be the oldest city in Germany. Traditionally it was known in English by its French name of Treves.

Prehistory

The first traces of human settlement in ...

(Trier

Trier ( , ; lb, Tréier ), formerly known in English as Trèves ( ;) and Triers (see also names in other languages), is a city on the banks of the Moselle in Germany. It lies in a valley between low vine-covered hills of red sandstone in the ...

).

The ''vicarius'' was based at Londinium as the principal city of the diocese. Londinium and Eboracum continued as provincial capitals and the territory was divided up into smaller provinces for administrative efficiency.

Civilian and military authority of a province was no longer exercised by one official and the governor was stripped of military command which was handed over to the ''Dux Britanniarum

''Dux Britanniarum'' was a military post in Roman Britain, probably created by Emperor Diocletian or Constantine I during the late third or early fourth century. The ''Dux'' (literally, "(military) leader" was a senior officer in the late Roma ...

'' by 314. The governor of a province assumed more financial duties (the procurators of the Treasury ministry were slowly phased out in the first three decades of the 4th century). The Dux was commander of the troops of the Northern Region, primarily along Hadrian's Wall and his responsibilities included protection of the frontier. He had significant autonomy due in part to the distance from his superiors.

The tasks of the ''vicarius'' were to control and coordinate the activities of governors; monitor but not interfere with the daily functioning of the Treasury and Crown Estates, which had their own administrative infrastructure; and act as the regional quartermaster-general of the armed forces. In short, as the sole civilian official with superior authority, he had general oversight of the administration, as well as direct control, while not absolute, over governors who were part of the prefecture; the other two fiscal departments were not.

The early-4th-century Verona List

The ''Laterculus Veronensis'' or Verona List is a list of Roman provinces and barbarian peoples from the time of the emperors Diocletian and Constantine I, most likely from AD 314.

The list is transmitted only in a 7th-century manuscript preser ...

, the late-4th-century work of Sextus Rufus, and the early-5th-century List of Offices and work of Polemius Silvius

Polemius Silvius (''fl.'' 5th century) was the author of an annotated Julian calendar that attempted to integrate the traditional Roman festival cycle with the new Christian holy days. His calendar, also referred to as a laterculus or ''fasti'', ...

all list four provinces by some variation of the names Britannia I, Britannia II, Maxima Caesariensis

Maxima Caesariensis (Latin for "The Caesarian province of Maximus"), also known as Britannia Maxima, was one of the provinces of the Diocese of " the Britains" created during the Diocletian Reforms at the end of the 3rd century. It was probably cre ...

, and Flavia Caesariensis; all of these seem to have initially been directed by a governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

(''praeses

''Praeses'' (Latin ''praesides'') is a Latin word meaning "placed before" or "at the head". In antiquity, notably under the Roman Dominate, it was used to refer to Roman governors; it continues to see some use for various modern positions.

...

'') of equestrian

The word equestrian is a reference to equestrianism, or horseback riding, derived from Latin ' and ', "horse".

Horseback riding (or Riding in British English)

Examples of this are:

* Equestrian sports

*Equestrian order, one of the upper classes i ...

rank. The 5th-century sources list a fifth province named Valentia and give its governor and Maxima's a consular

A consul is an official representative of the government of one state in the territory of another, normally acting to assist and protect the citizens of the consul's own country, as well as to facilitate trade and friendship between the people ...

rank. Ammianus

Ammianus Marcellinus (occasionally anglicised as Ammian) (born , died 400) was a Roman soldier and historian who wrote the penultimate major historical account surviving from antiquity (preceding Procopius). His work, known as the ''Res Gest ...

mentions Valentia as well, describing its creation by Count Theodosius

Flavius Theodosius (died 376), also known as Count Theodosius ( la, Theodosius comes) or Theodosius the Elder ( la, Theodosius Major), was a senior military officer serving Valentinian I () and the western Roman empire during Late Antiquity. Unde ...

in 369 after the quelling of the Great Conspiracy

The Great Conspiracy was a year-long state of war and disorder that occurred near the end of Roman Britain. The historian Ammianus Marcellinus described it as a ''barbarica conspiratio'', which capitalised on a depleted military force in the p ...

. Ammianus considered it a re-creation of a formerly lost province, leading some to think there had been an earlier fifth province under another name (may be the enigmatic "Vespasiana"?), and leading others to place Valentia beyond Hadrian's Wall, in the territory abandoned south of the Antonine Wall.

Reconstructions of the provinces and provincial capitals during this period partially rely on ecclesiastical records. On the assumption that the early bishoprics mimicked the imperial hierarchy, scholars use the list of bishops for the 314 Council of Arles. Unfortunately, the list is patently corrupt: the British delegation is given as including a Bishop "Eborius" of Eboracum

Eboracum () was a fort and later a city in the Roman province of Britannia. In its prime it was the largest town in northern Britain and a provincial capital. The site remained occupied after the decline of the Western Roman Empire and ultimat ...

and two bishops "from Londinium" (one ' and the other '). The error is variously emended: Bishop Ussher

James Ussher (or Usher; 4 January 1581 – 21 March 1656) was the Church of Ireland Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of All Ireland between 1625 and 1656. He was a prolific scholar and church leader, who today is most famous for his ident ...

proposed '' Colonia'', Selden ''Col.'' or '' Colon. Camalodun.'', and Spelman '' Colonia Cameloduni'' (all various names of Colchester

Colchester ( ) is a city in Essex, in the East of England. It had a population of 122,000 in 2011. The demonym is Colcestrian.

Colchester occupies the site of Camulodunum, the first major city in Roman Britain and its first capital. Colch ...

); Gale

A gale is a strong wind; the word is typically used as a descriptor in nautical contexts. The U.S. National Weather Service defines a gale as sustained surface winds moving at a speed of between 34 and 47 knots (, or ).Gale, Thomæ [

''Antonini Iter Britanniarum'' [''Antoninus's Route of the Britains''], "Iter V. A Londinio Lugvvallium Ad Vallum" [Route 5: From Londinium to Luguvalium at the Wall], p. 96.

Published posthumously & edited by R. Gale. M. Atkins (London), 1709. and Bingham offered ' and

''Researches into the Ecclesiastical and Political State of Ancient Britain under the Roman Emperors: with Observations upon the Principal Events and Characters Connected with the Christian Religion, during the First Five Centuries'', pp. 272 ff.

T. Cadell (London), 1843. On the basis of the Verona List, the priest and deacon who accompanied the bishops in some manuscripts are ascribed to the fourth province. In the 12th century,

George Simpson & Co. (Devizes), 1920. ;

''The Book of Invectives of Giraldus Cambrensis'' in ''Y Cymmrodor: The Magazine of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion'', Vol. XXX, p. 16.

George Simpson & Co. (Devizes), 1920. Modern scholars generally dispute the last: some place Valentia at or beyond Hadrian's Wall but St Andrews is beyond even the Antonine Wall and Gerald seems to have simply been supporting the antiquity of its church for political reasons. A common modern reconstruction places the consular province of Maxima at Londinium, on the basis of its status as the seat of the diocesan ''vicarius''; places Prima in the west according to Gerald's traditional account but moves its capital to

Emperor Constantius returned to Britain in 306, despite his poor health, with an army aiming to invade northern Britain, the provincial defences having been rebuilt in the preceding years. Little is known of his campaigns with scant archaeological evidence, but fragmentary historical sources suggest he reached the far north of Britain and won a major battle in early summer before returning south. His son Constantine (later

Emperor Constantius returned to Britain in 306, despite his poor health, with an army aiming to invade northern Britain, the provincial defences having been rebuilt in the preceding years. Little is known of his campaigns with scant archaeological evidence, but fragmentary historical sources suggest he reached the far north of Britain and won a major battle in early summer before returning south. His son Constantine (later

The traditional view of historians, informed by the work of

The traditional view of historians, informed by the work of

Mineral extraction sites such as the Dolaucothi gold mine were probably first worked by the Roman army from c. 75, and at some later stage passed to civilian operators. The mine developed as a series of opencast workings, mainly by the use of hydraulic mining methods. They are described by

Mineral extraction sites such as the Dolaucothi gold mine were probably first worked by the Roman army from c. 75, and at some later stage passed to civilian operators. The mine developed as a series of opencast workings, mainly by the use of hydraulic mining methods. They are described by

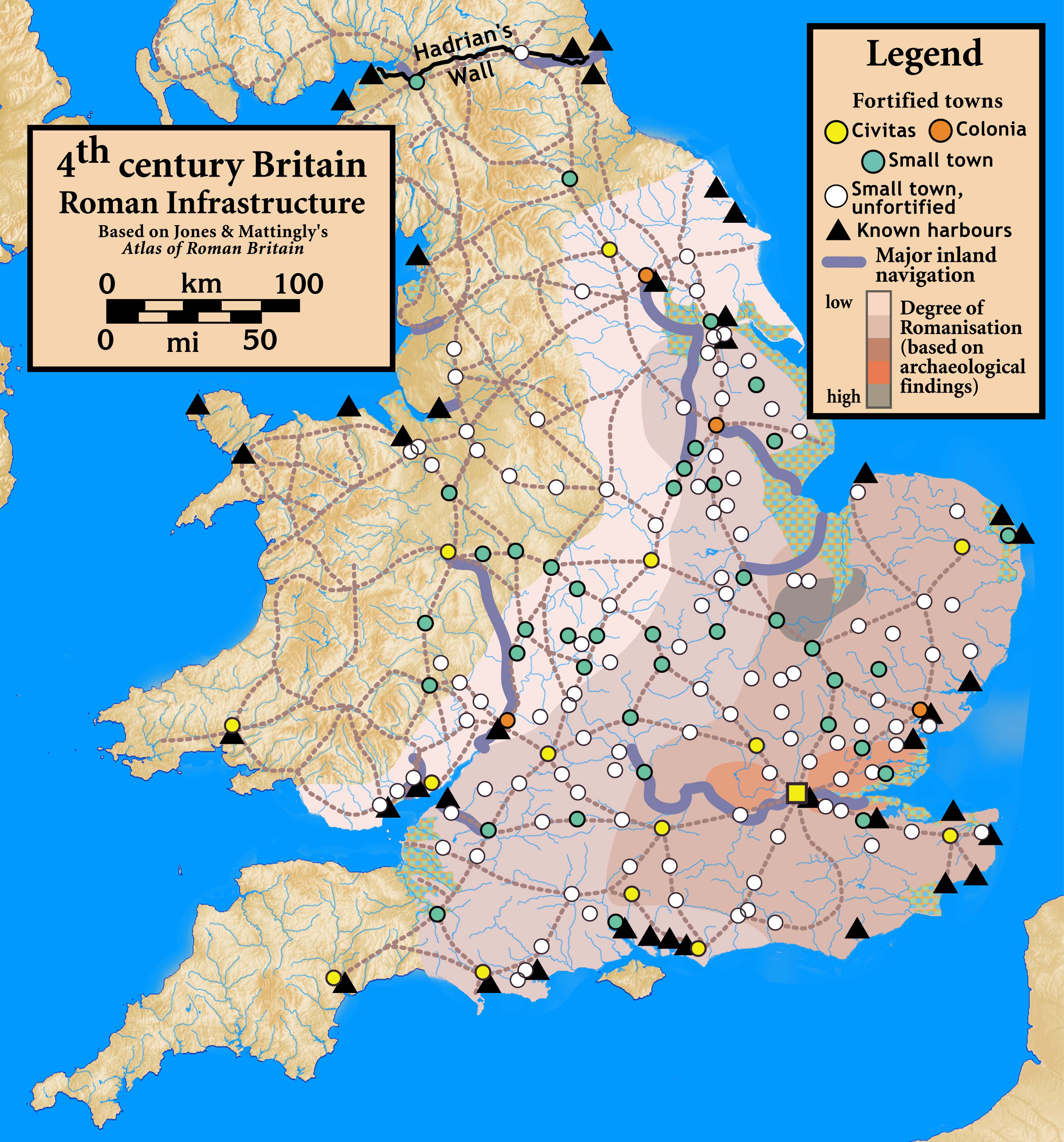

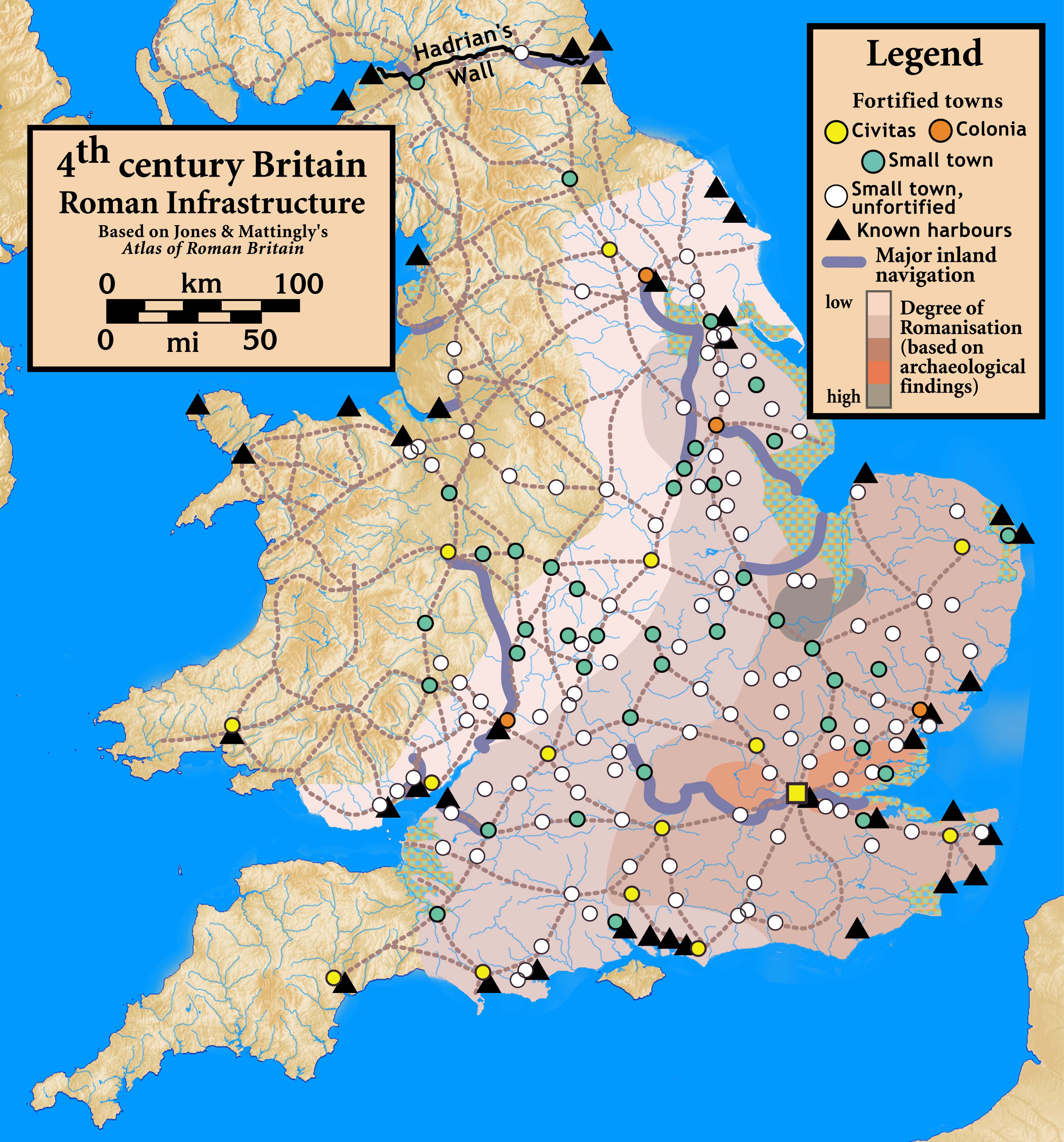

During their occupation of Britain the Romans founded a number of important settlements, many of which still survive. The towns suffered attrition in the later 4th century, when public building ceased and some were abandoned to private uses. Place names survived the deurbanised Sub-Roman and early Anglo-Saxon periods, and historiography has been at pains to signal the expected survivals, but archaeology shows that a bare handful of Roman towns were continuously occupied. According to S.T. Loseby, the very idea of a town as a centre of power and administration was reintroduced to England by the Roman Christianising mission to Canterbury, and its urban revival was delayed to the 10th century.

Roman towns can be broadly grouped in two categories. ', "public towns" were formally laid out on a grid plan, and their role in imperial administration occasioned the construction of public buildings. The much more numerous category of ', "small towns" grew on informal plans, often round a camp or at a ford or crossroads; some were not small, others were scarcely urban, some not even defended by a wall, the characteristic feature of a place of any importance.

Cities and towns which have Roman origins, or were extensively developed by them are listed with their Latin names in brackets; ' are marked C

During their occupation of Britain the Romans founded a number of important settlements, many of which still survive. The towns suffered attrition in the later 4th century, when public building ceased and some were abandoned to private uses. Place names survived the deurbanised Sub-Roman and early Anglo-Saxon periods, and historiography has been at pains to signal the expected survivals, but archaeology shows that a bare handful of Roman towns were continuously occupied. According to S.T. Loseby, the very idea of a town as a centre of power and administration was reintroduced to England by the Roman Christianising mission to Canterbury, and its urban revival was delayed to the 10th century.

Roman towns can be broadly grouped in two categories. ', "public towns" were formally laid out on a grid plan, and their role in imperial administration occasioned the construction of public buildings. The much more numerous category of ', "small towns" grew on informal plans, often round a camp or at a ford or crossroads; some were not small, others were scarcely urban, some not even defended by a wall, the characteristic feature of a place of any importance.

Cities and towns which have Roman origins, or were extensively developed by them are listed with their Latin names in brackets; ' are marked C

The druids, the Celtic priestly caste who were believed to originate in Britain, were outlawed by Claudius, and in 61 they vainly defended their

The druids, the Celtic priestly caste who were believed to originate in Britain, were outlawed by Claudius, and in 61 they vainly defended their

It is not clear when or how Christianity came to Britain. A 2nd-century "word square" has been discovered in

It is not clear when or how Christianity came to Britain. A 2nd-century "word square" has been discovered in

* .

* .

* .

* .

* .

* .

* .

* .

* .

* .

* .

* .

Timeline of Roman Britain

at

Thomas Gale

Thomas Gale (1635/1636?7 or 8 April 1702) was an English classical scholar, antiquarian and cleric.

Life

Gale was born at Scruton, Yorkshire. He was educated at Westminster School and Trinity College, Cambridge, of which he became a fellow ...

]''Antonini Iter Britanniarum'' [''Antoninus's Route of the Britains''], "Iter V. A Londinio Lugvvallium Ad Vallum" [Route 5: From Londinium to Luguvalium at the Wall], p. 96.

Published posthumously & edited by R. Gale. M. Atkins (London), 1709. and Bingham offered ' and

Henry

Henry may refer to:

People

*Henry (given name)

* Henry (surname)

* Henry Lau, Canadian singer and musician who performs under the mononym Henry

Royalty

* Portuguese royalty

** King-Cardinal Henry, King of Portugal

** Henry, Count of Portugal, ...

' (both Lincoln

Lincoln most commonly refers to:

* Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865), the sixteenth president of the United States

* Lincoln, England, cathedral city and county town of Lincolnshire, England

* Lincoln, Nebraska, the capital of Nebraska, U.S.

* Lincol ...

); and Bishop Stillingfleet and Francis Thackeray read it as a scribal error