Romain Rolland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Romain Rolland (; 29 January 1866 – 30 December 1944) was a French dramatist, novelist, essayist,

In 1937, he came back to live in

In 1937, he came back to live in

2 Apr. 2007

Online

* Zweig, Stephan. ''Romain Rolland: The Man and His Work'' (1921)

online

List of Works

Romain Rolland at Goodreads

Association Romain Rolland

on

art historian

Art history is the study of aesthetic objects and visual expression in historical and stylistic context. Traditionally, the discipline of art history emphasized painting, drawing, sculpture, architecture, ceramics and decorative arts; yet today, ...

and mystic who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1915 "as a tribute to the lofty idealism of his literary production and to the sympathy and love of truth with which he has described different types of human beings".

He was a leading supporter of Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

in France and is also noted for his correspondence with and influence on Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud ( , ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating pathologies explained as originating in conflicts i ...

.

Biography

Rolland was born in Clamecy, Nièvre into a family that had both wealthy townspeople and farmers in its lineage. Writing introspectively in his ''Voyage intérieur'' (1942), he sees himself as a representative of an "antique species". He would cast these ancestors in ''Colas Breugnon'' (1919). Accepted to theÉcole normale supérieure

École may refer to:

* an elementary school in the French educational stages normally followed by secondary education establishments (collège and lycée)

* École (river), a tributary of the Seine flowing in région Île-de-France

* École, S ...

in 1886, he first studied philosophy, but his independence of spirit led him to abandon that so as not to submit to the dominant ideology. He received his degree in history in 1889 and spent two years in Rome, where his encounter with Malwida von Meysenbug–who had been a friend of Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (; or ; 15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist, and composer whose work has exerted a profound influence on contemporary philosophy. He began his car ...

and of Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most op ...

–and his discovery of Italian masterpieces were decisive for the development of his thought. When he returned to France in 1895, he received his doctoral degree with his thesis ''Les origines du théâtre lyrique moderne. Histoire de l’opéra en Europe avant Lulli et Scarlatti'' (''The origins of modern lyric theatre. A History of Opera in Europe before Lully and Scarlatti''). For the next two decades, he taught at various lycées in Paris before directing the newly established music school of the École des Hautes Études Sociales from 1902 to 1911. In 1903 he was appointed to the first chair of music history at the Sorbonne, he also directed briefly in 1911 the musical section at the French Institute in Florence.

His first book was published in 1902, when he was 36 years old. Through his advocacy for a 'people's theatre', he made a significant contribution towards the democratization

Democratization, or democratisation, is the transition to a more democratic political regime, including substantive political changes moving in a democratic direction. It may be a hybrid regime in transition from an authoritarian regime to a full ...

of the theatre. As a humanist, he embraced the work of the philosophers of India ("Conversations with Rabindranath Tagore

Rabindranath Tagore (; bn, রবীন্দ্রনাথ ঠাকুর; 7 May 1861 – 7 August 1941) was a Bengali polymath who worked as a poet, writer, playwright, composer, philosopher, social reformer and painter. He resh ...

" and Mohandas Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

). Rolland was strongly influenced by the Vedanta

''Vedanta'' (; sa, वेदान्त, ), also ''Uttara Mīmāṃsā'', is one of the six (''āstika'') schools of Hindu philosophy. Literally meaning "end of the Vedas", Vedanta reflects ideas that emerged from, or were aligned with, ...

philosophy of India, primarily through the works of Swami Vivekananda

Swami Vivekananda (; ; 12 January 1863 – 4 July 1902), born Narendranath Datta (), was an Indian Hindu monk, philosopher, author, religious teacher, and the chief disciple of the Indian mystic Ramakrishna. He was a key figure in the intr ...

.

A demanding, yet timid, young man, he did not like teaching. He was not indifferent to youth: Jean-Christophe, Olivier and their friends, the heroes of his novels, are young people. But with real-life persons, youths as well as adults, Rolland maintained only a distant relationship. He was first and foremost a writer. Assured that literature would provide him with a modest income, he resigned from the university in 1912.

Romain Rolland was a lifelong pacifist. He was one of the few major French writers to retain his pacifist internationalist values; he moved to Switzerland. He protested against the first World War in ' (1915), ''Above the Battle'' (Chicago, 1916). In 1924, his book on Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

contributed to the Indian nonviolent

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

leader's reputation and the two men met in 1931. Rolland was a vegetarian

Vegetarianism is the practice of abstaining from the consumption of meat (red meat, poultry, seafood, insects, and the flesh of any other animal). It may also include abstaining from eating all by-products of animal slaughter.

Vegetariani ...

.

In May 1922 he attended the International Congress of Progressive Artists and signed the "Founding Proclamation of the Union of Progressive International Artists".

In 1928 Rolland and Hungarian scholar, philosopher and natural living experimenter Edmund Bordeaux Szekely founded the International Biogenic Society to promote and expand on their ideas of the integration of mind, body and spirit.

In 1932 Rolland was among the first members of the World Committee Against War and Fascism, organized by Willi Münzenberg. Rolland criticized the control Münzenberg assumed over the committee and was against it being based in Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

.

Rolland moved to Villeneuve, on the shores of Lake Geneva

, image = Lake Geneva by Sentinel-2.jpg

, caption = Satellite image

, image_bathymetry =

, caption_bathymetry =

, location = Switzerland, France

, coords =

, lake_type = Glacial lak ...

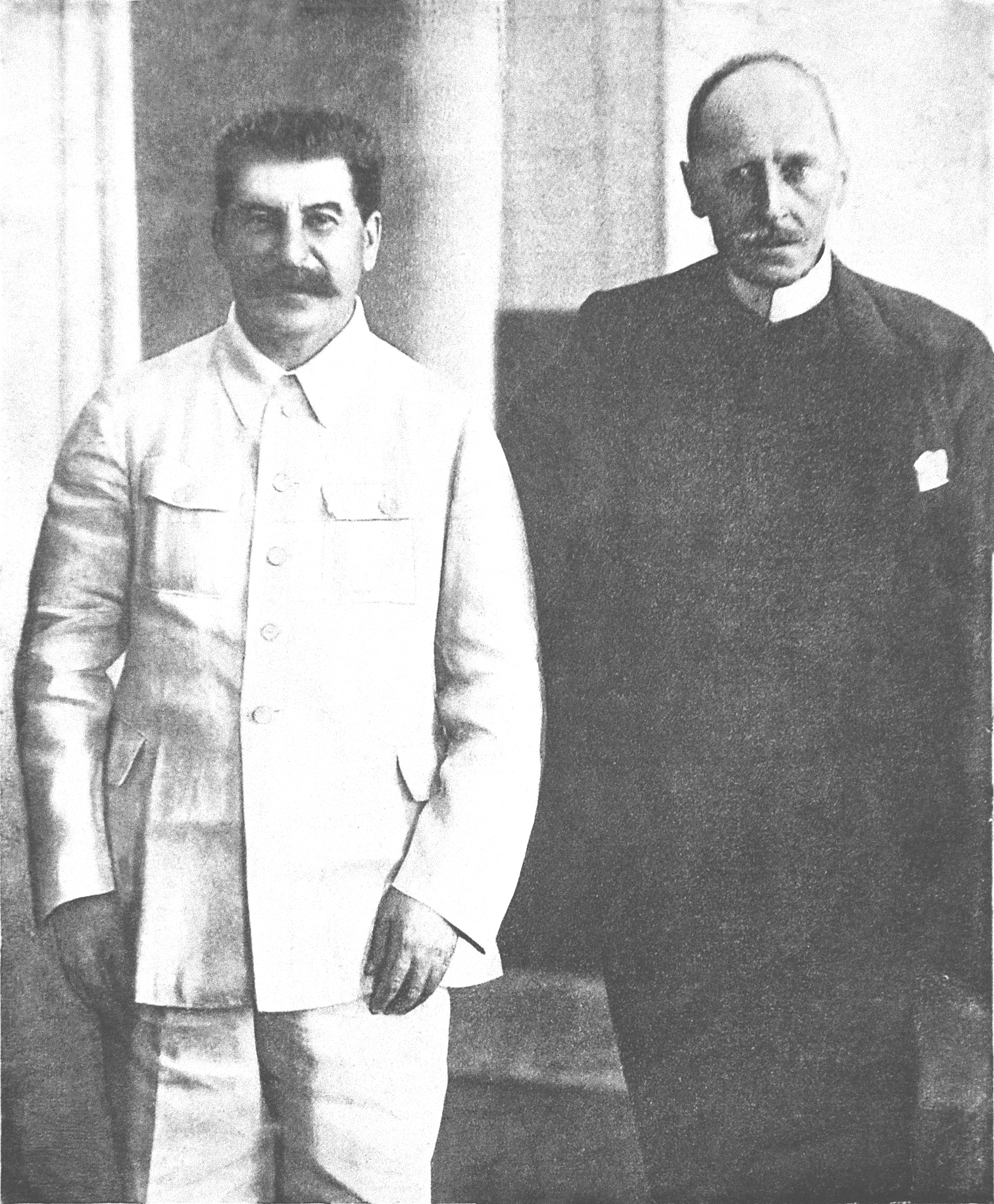

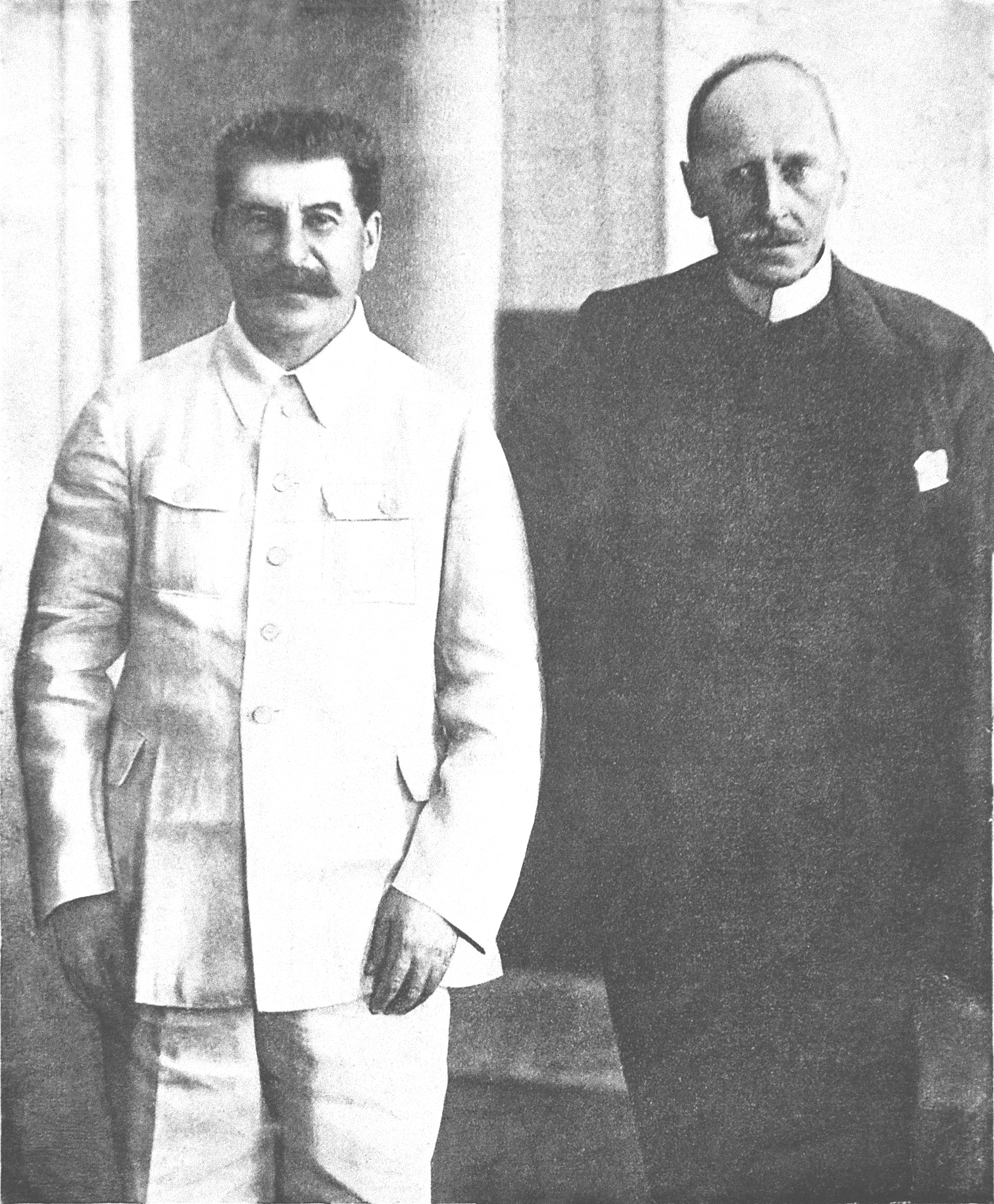

to devote himself to writing. His life was interrupted by health problems, and by travels to art exhibitions. His visit to Moscow (1935), on the invitation of Maxim Gorky

Alexei Maximovich Peshkov (russian: link=no, Алексе́й Макси́мович Пешко́в; – 18 June 1936), popularly known as Maxim Gorky (russian: Макси́м Го́рький, link=no), was a Russian writer and social ...

, was an opportunity to meet Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

, whom he considered the greatest man of his time. Rolland served unofficially as ambassador of French artists to the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

. Although he admired Stalin, he attempted to intervene against the persecution of his friends. He attempted to discuss his concerns with Stalin, and was involved in the campaign for the release of the Left Opposition activist and writer Victor Serge and wrote to Stalin begging clemency for Nikolai Bukharin

Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin (russian: Никола́й Ива́нович Буха́рин) ( – 15 March 1938) was a Bolshevik revolutionary, Soviet politician, Marxist philosopher and economist and prolific author on revolutionary theory. ...

. During Serge's imprisonment (1933–1936), Rolland had agreed to handle the publications of Serge's writings in France, despite their political disagreements.

In 1937, he came back to live in

In 1937, he came back to live in Vézelay

Vézelay () is a commune in the department of Yonne in the north-central French region of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté. It is a defensible hill town famous for Vézelay Abbey. The town and its 11th-century Romanesque Basilica of St Magdalene ar ...

, which, in 1940, was occupied by the Germans. During the occupation, he isolated himself in complete solitude. Never stopping his work, in 1940, he finished his memoirs. He also placed the finishing touches on his musical research on the life of Ludwig van Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classic ...

. Shortly before his death, he wrote '' Péguy'' (1944), in which he examines religion and socialism through the context of his memories. He died on 30 December 1944 in Vézelay.

In 1921, his close friend the Austrian writer Stefan Zweig

Stefan Zweig (; ; 28 November 1881 – 22 February 1942) was an Austrian novelist, playwright, journalist, and biographer. At the height of his literary career, in the 1920s and 1930s, he was one of the most widely translated and popular write ...

published his biography (in English ''Romain Rolland: The Man and His Works''). Zweig profoundly admired Rolland, whom he once described as "the moral consciousness of Europe" during the years of turmoil and War in Europe. Zweig wrote at length about his friendship with Rolland in his own autobiography (in English '' The World of Yesterday'').

Victor Serge was appreciative of Rolland's interventions on his behalf but ultimately thoroughly disappointed by Rolland's refusal to break publicly with Stalin and the repressive Soviet regime. The entry for 4 May 1945, a few weeks after Rolland's death, in Serge's ''Notebooks: 1936-1947'' notes acidly that "At age seventy the author of ''Jean-Christophe'' allowed himself to be covered with the blood spilled by a tyranny of which he was a faithful adulator."

Hermann Hesse

Hermann Karl Hesse (; 2 July 1877 – 9 August 1962) was a German-Swiss poet, novelist, and painter. His best-known works include '' Demian'', '' Steppenwolf'', '' Siddhartha'', and '' The Glass Bead Game'', each of which explores an individual ...

dedicated '' Siddhartha'' to Romain Rolland "my dear friend".

People's theatre

Rolland's most significant contribution to the theatre lies in his advocacy for a "popular theatre" in his essay ''The People's Theatre'' (''Le Théâtre du peuple'', 1902).David Bradby, "Rolland, Romain". In ''The Cambridge Guide to Theatre.'' Ed. Martin Banham. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998). . p.930. "There is only one necessary condition for the emergence of a new theatre", he wrote, "that the stage andauditorium

An auditorium is a room built to enable an audience to hear and watch performances. For movie theatres, the number of auditoria (or auditoriums) is expressed as the number of screens. Auditoria can be found in entertainment venues, communit ...

should be open to the masses, should be able to contain a people and the actions of a people". The book was not published until 1913, but most of its contents had appeared in the ''Revue d'Art Dramatique'' between 1900 and 1903. Rolland attempted to put his theory into practice with his melodrama

A modern melodrama is a dramatic work in which the plot, typically sensationalized and for a strong emotional appeal, takes precedence over detailed characterization. Melodramas typically concentrate on dialogue that is often bombastic or exce ...

tic dramas about the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

, ''Danton'' (1900) and ''The Fourteenth of July'' (1902), but it was his ideas that formed a major reference point for subsequent practitioners.

The essay is part of a more general movement around the turn of that century towards the democratization

Democratization, or democratisation, is the transition to a more democratic political regime, including substantive political changes moving in a democratic direction. It may be a hybrid regime in transition from an authoritarian regime to a full ...

of the theatre. The ''Revue'' had held a competition and tried to organize a "World Congress on People's Theatre", and a number of People's Theatres had opened across Europe, including the Freie Volksbühne movement ('Free People's Theatre') in Germany and Maurice Pottecher's Théâtre du Peuple in France. Rolland was a disciple of Pottecher and dedicated ''The People's Theatre'' to him.

Rolland's approach is more aggressive, though, than Pottecher's poetic vision of theatre as a substitute 'social religion' bringing unity to the nation. Rolland indicts the bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. Th ...

for its appropriation of the theatre, causing it to slide into decadence

The word decadence, which at first meant simply "decline" in an abstract sense, is now most often used to refer to a perceived decay in standards, morals, dignity, religious faith, honor, discipline, or skill at governing among the members ...

, and the deleterious effects of its ideological dominance. In proposing a suitable repertoire

A repertoire () is a list or set of dramas, operas, musical compositions or roles which a company or person is prepared to perform.

Musicians often have a musical repertoire. The first known use of the word ''repertoire'' was in 1847. It is a ...

for his people's theatre, Rolland rejects classical drama in the belief that it is either too difficult or too static to be of interest to the masses. Drawing on the ideas of Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

, he proposes instead "an epic historical theatre of 'joy, force and intelligence' which will remind the people of its revolutionary heritage and revitalize the forces working for a new society" (in the words of Bradby and McCormick, quoting Rolland). Rolland believed that the people would be improved by seeing heroic images of their past. Rousseau's influence may be detected in Rolland's conception of theatre-as- festivity, an emphasis that reveals a fundamental anti-theatrical prejudice

Antitheatricality is any form of opposition or hostility to theater. Such opposition is as old as theater itself, suggesting a deep-seated ambivalence in human nature about the dramatic arts. Jonas Barish's 1981 book, ''The Antitheatrical Prejudice ...

: "Theatre supposes lives that are poor and agitated, a people searching in dreams for a refuge from thought. If we were happier and freer we should not feel hungry for theatre. ..A people that is happy and free has need of festivities more than of theatres; it will always see in itself the finest spectacle

In general, spectacle refers to an event that is memorable for the appearance it creates. Derived in Middle English from c. 1340 as "specially prepared or arranged display" it was borrowed from Old French ''spectacle'', itself a reflection of t ...

".

Rolland's dramas have been staged by some of the most influential theatre directors of the twentieth century, including Max Reinhardt

Max Reinhardt (; born Maximilian Goldmann; 9 September 1873 – 30 October 1943) was an Austrian-born theatre and film director, intendant, and theatrical producer. With his innovative stage productions, he is regarded as one of the most pr ...

and Erwin Piscator

Erwin Friedrich Maximilian Piscator (17 December 1893 – 30 March 1966) was a German theatre director and producer. Along with Bertolt Brecht, he was the foremost exponent of epic theatre, a form that emphasizes the socio-political content o ...

. Piscator directed the world première of Rolland's pacifist drama ''The Time Will Come'' (''Le Temps viendra'', written in 1903) at Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

's Central-Theater, which opened on 17 November 1922 with music by K Pringsheim and scenic design

Scenic design (also known as scenography, stage design, or set design) is the creation of theatrical, as well as film or television scenery. Scenic designers come from a variety of artistic backgrounds, but in recent years, are mostly train ...

by O Schmalhausen and M Meier. The play addresses the connections between imperialism

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic powe ...

and capitalism, the treatment of enemy civilians, and the use of concentration camp

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simpl ...

s, all of which are dramatised via an episode in the Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sou ...

.Hugh Rorrison, in Piscator (1929, 55–56). Piscator described his treatment of the play as "thoroughly naturalistic", whereby he sought "to achieve the greatest possible realism

Realism, Realistic, or Realists may refer to:

In the arts

*Realism (arts), the general attempt to depict subjects truthfully in different forms of the arts

Arts movements related to realism include:

* Classical Realism

*Literary realism, a mov ...

in acting and decor". Despite the play's overly-rhetoric

Rhetoric () is the art of persuasion, which along with grammar and logic (or dialectic), is one of the three ancient arts of discourse. Rhetoric aims to study the techniques writers or speakers utilize to inform, persuade, or motivate par ...

al style, the production was reviewed positively.

Novels

Rolland's most famous novel is the 10-volume novel sequence '' Jean-Christophe'' (1904–1912), which brings "together his interests and ideals in the story of a German musical genius who makes France his second home and becomes a vehicle for Rolland's views on music, social matters and understanding between nations". His other novels are ''Colas Breugnon'' (1919), '' Clérambault'' (1920), '' Pierre et Luce'' (1920) and his second roman-fleuve, the 7-volume ''L'âme enchantée'' (1922–1933).Academic career

He became a history teacher atLycée Henri IV

In France, secondary education is in two stages:

* ''Collèges'' () cater for the first four years of secondary education from the ages of 11 to 15.

* ''Lycées'' () provide a three-year course of further secondary education for children betwee ...

, then at the Lycée Louis le Grand

In France, secondary education is in two stages:

* ''Collèges'' () cater for the first four years of secondary education from the ages of 11 to 15.

* ''Lycées'' () provide a three-year course of further secondary education for children betwee ...

, and member of the École française de Rome, then a professor of the History of Music at the Sorbonne, and History Professor at the École Normale Supérieure.

Correspondence with Richard Strauss

In 1899 Rolland started what became a voluminous correspondence with the German composerRichard Strauss

Richard Georg Strauss (; 11 June 1864 – 8 September 1949) was a German composer, conductor, pianist, and violinist. Considered a leading composer of the late Romantic and early modern eras, he has been described as a successor of Richard Wag ...

(the English translation, edited by Rollo Myers, runs to 239 pages, including some diary entries). At the time, Strauss was a celebrated conductor of works by Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most op ...

, Liszt

Franz Liszt, in modern usage ''Liszt Ferenc'' . Liszt's Hungarian passport spelled his given name as "Ferencz". An orthographic reform of the Hungarian language in 1922 (which was 36 years after Liszt's death) changed the letter "cz" to simpl ...

, Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 17565 December 1791), baptised as Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart, was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period. Despite his short life, his rapid pace of composition r ...

, and of his own tone poems. In 1905, Strauss had completed his opera ''Salome'', based on the verse play by Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular playwrights in London in the early 1890s. He is ...

, originally written in French. Strauss based his version of ''Salome'' on Hedwig Lachmann's German translation which he had seen performed in Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

in 1902. Out of respect for Wilde, Strauss wanted to create a parallel French version, to be as close as possible to Wilde's original text, and he wrote to Rolland requesting his help on this project.

Rolland was initially reluctant, but a lengthy exchange ensued, occupying 50 pages of the Myers edition, and in the end Rolland made 191 suggestions for improving the Strauss/Wilde libretto. The resulting French version of ''Salome'' received its first performance in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

in 1907, two years after the German premiere. Thereafter, Rolland's letters regularly discussed Strauss's operas, including the occasional criticism of Strauss's librettist, Hugo von Hoffmannsthal: "I only regret that the great writer who gives you such brilliant libretti too often lacks a sense of the theatre."

Rolland was a pacifist, and concurred with Strauss when the latter refused to sign the Manifesto of German artists and intellectuals supporting the German role in World War I. Rolland noted Strauss's response in his diary entry for October 1914: "Declarations about war and politics are not fitting for an artist, who must give his attention to his creations and his works."(''Myers p. 160'')

Correspondence with Freud

1923 saw the beginning of a correspondence between psychoanalystSigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud ( , ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating pathologies explained as originating in conflicts i ...

and Rolland, who found that the admiration that he showed for Freud was reciprocated in equal measures (Freud proclaiming in a letter to him: "That I have been allowed to exchange a greeting with you will remain a happy memory to the end of my days."). This correspondence introduced Freud to the concept of the "oceanic feeling

In a 1927 letter to Sigmund Freud, Romain Rolland coined the phrase "oceanic feeling" to refer to "a sensation of ' eternity, a feeling of " being one with the external world as a whole", inspired by the example of Ramakrishna, among other mys ...

" that Rolland had developed through his study of Eastern mysticism. Freud opened his next book '' Civilization and its Discontents'' (1929) with a debate on the nature of this feeling, which he mentioned had been noted to him by an anonymous "friend". This friend was Rolland. Rolland would remain a major influence on Freud's work, continuing their correspondence right up to Freud's death in 1939.William B. Parsons, ''The Enigma of the Oceanic Feeling: Revisioning the Psychoanalytic Theory of Mysticism'' (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999) 19,2 Apr. 2007

Bibliography

See also

*List of peace activists

This list of peace activists includes people who have proactively advocated diplomatic, philosophical, and non-military resolution of major territorial or ideological disputes through nonviolent means and methods. Peace activists usually work wi ...

References

Further reading

* Fisher, David James. ''Romain Rolland and the Politics of the Intellectual Engagement'' (2003) * David-Fox, Michael. "The 'Heroic Life' of a Friend of Stalinism: Romain Rolland and Soviet Culture." ''Slavonica'' 11.1 (2005): 3-29Online

* Zweig, Stephan. ''Romain Rolland: The Man and His Work'' (1921)

online

External links

* * * * *List of Works

Romain Rolland at Goodreads

Association Romain Rolland

on

Vedanta

''Vedanta'' (; sa, वेदान्त, ), also ''Uttara Mīmāṃsā'', is one of the six (''āstika'') schools of Hindu philosophy. Literally meaning "end of the Vedas", Vedanta reflects ideas that emerged from, or were aligned with, ...

*

*

Electronic editions

* * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Rolland, Romain 1866 births 1944 deaths 19th-century French dramatists and playwrights 19th-century French novelists 20th-century French dramatists and playwrights 20th-century French novelists École Normale Supérieure alumni French expatriates in the Soviet Union French male novelists French Nobel laureates French pacifists Honorary Members of the USSR Academy of Sciences Lycée Louis-le-Grand alumni Nobel laureates in Literature Nonviolence advocates People from Nièvre Prix Femina winners Spinozists Writers about the Soviet Union Writers from Bourgogne-Franche-Comté Gandhians