Rodrigo Borgia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Pope Alexander VI ( it, Alessandro VI, va, Alexandre VI, es, Alejandro VI; born Rodrigo de Borja; ca-valencia, Roderic Llançol i de Borja ; es, Rodrigo Lanzol y de Borja, lang ; 1431 – 18 August 1503) was head of the

volumes 1–5

/ref> The election of his uncle, Alfons Cardinal de Borja, as

vol. 6, p. 50

In contrast to the preceding pontificate, Pope Alexander VI adhered initially to strict administration of justice and orderly government. Before long, though, he began endowing his relatives at the Church's and at his neighbours' expense.

In contrast to the preceding pontificate, Pope Alexander VI adhered initially to strict administration of justice and orderly government. Before long, though, he began endowing his relatives at the Church's and at his neighbours' expense.

Pope Alexander VI made many alliances to secure his position. He sought help from

Pope Alexander VI made many alliances to secure his position. He sought help from

Virginio Orsini, who had been captured by the Spanish, died a prisoner at Naples, and the Pope confiscated his property. The rest of the Orsini clan still held out, defeating the papal troops sent against them under

Virginio Orsini, who had been captured by the Spanish, died a prisoner at Naples, and the Pope confiscated his property. The rest of the Orsini clan still held out, defeating the papal troops sent against them under

The debased state of the curia was a major scandal. Opponents, such as the powerful Florentine friar

The debased state of the curia was a major scandal. Opponents, such as the powerful Florentine friar

Of Alexander's many mistresses, one of his favourites was Vannozza dei Cattanei, born in 1442, and wife of three successive husbands. The connection began in 1470, and she had four children whom the pope openly acknowledged as his own: Cesare (born 1475), Giovanni, afterwards duke of

Of Alexander's many mistresses, one of his favourites was Vannozza dei Cattanei, born in 1442, and wife of three successive husbands. The connection began in 1470, and she had four children whom the pope openly acknowledged as his own: Cesare (born 1475), Giovanni, afterwards duke of

File:Buch2-318.jpg, Giovanni Borgia, 2nd Duke of Gandia.

File:Cesareborgia.jpg, '' Portrait of a Gentleman'' (

Six other children, Girolama, Isabella, Pedro-Luiz, Giovanni the "Infans Romanus", Rodrigo and Bernardo, were of uncertain maternal parentage. His daughter Isabella was the great-great-grandmother of

File:DomenichinounicornPalFarnese.jpg,

Cesare was preparing for another expedition in August 1503 when, after he and his father had dined with Cardinal Adriano Castellesi on 6 August, they were taken ill with fever a few days later. Cesare, who "lay in bed, his skin peeling and his face suffused to a violet colour" as a consequence of certain drastic measures to save him, eventually recovered; but the aged Pontiff apparently had little chance. Burchard's ''Diary'' provides a few details of the pope's final illness and death at age 72:

Cesare was preparing for another expedition in August 1503 when, after he and his father had dined with Cardinal Adriano Castellesi on 6 August, they were taken ill with fever a few days later. Cesare, who "lay in bed, his skin peeling and his face suffused to a violet colour" as a consequence of certain drastic measures to save him, eventually recovered; but the aged Pontiff apparently had little chance. Burchard's ''Diary'' provides a few details of the pope's final illness and death at age 72:

Following the death of Alexander VI, his rival and successor

Following the death of Alexander VI, his rival and successor

Burkle-Young, Francis A., "The election of Pope Alexander VI (1492)", in Miranda, Salvador. ''Cardinals of the Holy Roman Church''

*

Volume V

Saint Louis: B. Herder 1902. * Pastor, Ludwig von. ''The History of the Popes, from the close of the Middle Ages'', second edition

Volume VI

Saint Louis: B. Herder 1902. * Weckman-Muñoz, Luis. "The Alexandrine Bulls of 1493" in ''First Images of America: The Impact of the New World on the Old''. Edited by Fredi Chiappelli. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 1976, pp. 201–210.

DIARIO BORJA BORGIA (Spanish)

* Thirty-Two Years with Alexander VI, ''The Catholic Historical Review'', vol. 8, no. 1, April 1922, pp. 55–5

Thirty-Two Years with Alexander VIThe Catholic Historical Review

Diario Borja – Borgia

Francisco Fernández de Bethencourt – Historia Genealógica y Heráldica Española, Casa Real y Grandes de España, tomo cuarto

Una rama subsistente del linaje Borja en América española, por Jaime de Salazar y Acha, Académico de Número de la Real Academia Matritense de Heráldica y Genealogía

Boletín de la Real Academia Matritense de Heráldica y Genealogía

* * * * (spanisch) * {{DEFAULTSORT:Alexander 06 15th-century Roman Catholic archbishops in the Kingdom of Aragon 16th-century Spanish people Archbishops of Valencia Burials at Santa Maria in Monserrato degli Spagnoli Cardinal-bishops of Albano Cardinal-bishops of Porto Cardinal-nephews Deans of the College of Cardinals House of Borgia People from Xàtiva Popes Renaissance Papacy Spanish popes University of Bologna alumni 1431 births 1503 deaths Simony 15th-century popes 16th-century popes Spanish art patrons

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

and ruler of the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope fro ...

from 11 August 1492 until his death in 1503.

Born into the prominent Borgia family in Xàtiva under the Crown of Aragon

The Crown of Aragon ( , ) an, Corona d'Aragón ; ca, Corona d'Aragó, , , ; es, Corona de Aragón ; la, Corona Aragonum . was a composite monarchy ruled by one king, originated by the dynastic union of the Kingdom of Aragon and the County of ...

(now Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

), Rodrigo studied law at the University of Bologna

The University of Bologna ( it, Alma Mater Studiorum – Università di Bologna, UNIBO) is a public research university in Bologna, Italy. Founded in 1088 by an organised guild of students (''studiorum''), it is the oldest university in contin ...

. He was ordained deacon

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions. Major Christian churches, such as the Catholic Chur ...

and made a cardinal

Cardinal or The Cardinal may refer to:

Animals

* Cardinal (bird) or Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**''Cardinalis'', genus of cardinal in the family Cardinalidae

**''Cardinalis cardinalis'', or northern cardinal, the ...

in 1456 after the election of his uncle as Pope Callixtus III

Pope Callixtus III ( it, Callisto III, va, Calixt III, es, Calixto III; 31 December 1378 – 6 August 1458), born Alfonso de Borgia ( va, Alfons de Borja), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 April 1455 to his ...

, and a year later he became vice-chancellor

A chancellor is a leader of a college or university, usually either the executive or ceremonial head of the university or of a university campus within a university system.

In most Commonwealth and former Commonwealth nations, the chancellor ...

of the Catholic Church. He proceeded to serve in the Curia

Curia (Latin plural curiae) in ancient Rome referred to one of the original groupings of the citizenry, eventually numbering 30, and later every Roman citizen was presumed to belong to one. While they originally likely had wider powers, they came ...

under the next four popes, acquiring significant influence and wealth in the process. In 1492, Rodrigo was elected pope, taking the name Alexander VI.

Alexander's papal bulls of 1493 confirmed or reconfirmed the rights of the Spanish crown in the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

following the finds of Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

in 1492. During the second Italian war

The second (symbol: s) is the unit of time in the International System of Units (SI), historically defined as of a day – this factor derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes and finally to 60 seconds each ...

, Alexander VI supported his son Cesare Borgia

Cesare Borgia (; ca-valencia, Cèsar Borja ; es, link=no, César Borja ; 13 September 1475 – 12 March 1507) was an Italian ex-cardinal and ''condottiero'' (mercenary leader) of Aragonese (Spanish) origin, whose fight for power was a major i ...

as a condottiero

''Condottieri'' (; singular ''condottiero'' or ''condottiere'') were Italian captains in command of mercenary companies during the Middle Ages and of multinational armies during the early modern period. They notably served popes and other Euro ...

for the French king. The scope of his foreign policy was to gain the most advantageous terms for his family.

Alexander is considered one of the most controversial of the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

popes, partly because he acknowledged fathering several children by his mistresses. As a result, his Italianized Valencian

Valencian () or Valencian language () is the official, historical and traditional name used in the Valencian Community (Spain), and unofficially in the El Carche comarca in Murcia (Spain), to refer to the Romance language also known as Catal ...

surname, ''Borgia'', became a byword for libertinism

A libertine is a person devoid of most moral principles, a sense of responsibility, or sexual restraints, which they see as unnecessary or undesirable, and is especially someone who ignores or even spurns accepted morals and forms of behaviour o ...

and nepotism

Nepotism is an advantage, privilege, or position that is granted to relatives and friends in an occupation or field. These fields may include but are not limited to, business, politics, academia, entertainment, sports, fitness, religion, an ...

, which are traditionally considered as characterizing his pontificate. On the other hand, two of Alexander's successors, Sixtus V

Pope Sixtus V ( it, Sisto V; 13 December 1521 – 27 August 1590), born Felice Piergentile, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 24 April 1585 to his death in August 1590. As a youth, he joined the Franciscan order ...

and Urban VIII

Pope Urban VIII ( la, Urbanus VIII; it, Urbano VIII; baptised 5 April 1568 – 29 July 1644), born Maffeo Vincenzo Barberini, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 6 August 1623 to his death in July 1644. As p ...

, described him as one of the most outstanding popes since Saint Peter

) (Simeon, Simon)

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Bethsaida, Gaulanitis, Syria, Roman Empire

, death_date = Between AD 64–68

, death_place = probably Vatican Hill, Rome, Italia, Roman Empire

, parents = John (or Jonah; Jona)

, occupat ...

.

Birth and family

Rodrigo de Borja was born in 1431, in the town of Xàtiva nearValencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the autonomous community of Valencia and the third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is also the capital of the province of the same name. The wider urban area al ...

, one of the component realms of the Crown of Aragon

The Crown of Aragon ( , ) an, Corona d'Aragón ; ca, Corona d'Aragó, , , ; es, Corona de Aragón ; la, Corona Aragonum . was a composite monarchy ruled by one king, originated by the dynastic union of the Kingdom of Aragon and the County of ...

, in what is now Spain. He was named for his paternal grandfather, Rodrigo Gil de Borja y Fennolet

Roderic Gil de Borja i Fennolet was a Valencian noble from Xàtiva, Kingdom of Valencia, with origins in the town of Borja, Zaragoza. He held the title of the Jurat de l'Estament Militar de Xàtiva in 1395, 1406 and 1407 respectively, a title tha ...

. His parents were Jofré Llançol i Escrivà

Jofré Llançol i Escrivà, (c. 1390 - 1436/37), also known as Jofré de Borja y Escrivà and Jofré de Borja y Doms, was a Spanish noble from Xàtiva, Kingdom of Valencia. He was related by marriage to the Borgia family. He was an uncle of Card ...

(died bef. 24 March 1437) and his Aragonese wife and distant cousin Isabel de Borja y Cavanilles (died 19 October 1468), daughter of Juan Domingo de Borja y Doncel Juan Domingo de Borja y Doncel (b. circa 1357 - d. ?) was the father of future Pope Callixtus III. He held the title over the Barony La Torre de Canals. He was a member of the House of Borja.

Biography

Domènec made his fortune in Xàtiva, where ...

. He had a younger brother, Pedro

Pedro is a masculine given name. Pedro is the Spanish, Portuguese, and Galician name for '' Peter''. Its French equivalent is Pierre while its English and Germanic form is Peter.

The counterpart patronymic surname of the name Pedro, mean ...

. His family name is written ''Llançol'' in Valencian

Valencian () or Valencian language () is the official, historical and traditional name used in the Valencian Community (Spain), and unofficially in the El Carche comarca in Murcia (Spain), to refer to the Romance language also known as Catal ...

and ''Lanzol'' in Castillian. Rodrigo adopted his mother's family name of Borja in 1455 following the elevation to the papacy

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

of maternal uncle Alonso de Borja (Italianized to Alfonso Borgia) as Calixtus III

Pope Callixtus III ( it, Callisto III, va, Calixt III, es, Calixto III; 31 December 1378 – 6 August 1458), born Alfonso de Borgia ( va, Alfons de Borja), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 April 1455 to his ...

. His cousin and Calixtus's nephew Luis de Milà y de Borja

Luis Julian de Milà y de Borja (1432 Xàtiva, Kingdom of Valencia, Crown of Aragon – 1510 Bèlgida, Kingdom of Valencia, Crown of Aragon) was a cardinal of the Catholic Church.

His parents were Juan de Milà and Catalina de Borja, daughter ...

became a cardinal.

Gerard Noel writes that Rodrigo's father was Jofré de Borja y Escrivà, making Rodrigo a Borja from his mother and father's side. However, Cesare, Lucrezia and Jofre were known to be of Llançol paternal lineage. G. J. Meyer

Gerald J. Meyer (born 1940), author and journalist, is a writer of historical non-fiction, a former Woodrow Wilson Fellow with an M.A. in English literature from the University of Minnesota. He holds a Harvard University's Nieman Fellowship in ...

suggests that Rodrigo would have likely been uncle (from a shared female family member) to the children, and attributes the confusion to attempts to connect Rodrigo as the father of Giovanni (Juan), Cesare, Lucrezia, and Gioffre (Jofré in Valencian

Valencian () or Valencian language () is the official, historical and traditional name used in the Valencian Community (Spain), and unofficially in the El Carche comarca in Murcia (Spain), to refer to the Romance language also known as Catal ...

), who were surnamed ''Llançol i Borja''.

Career

Rodrigo de Borja's career in the Church began in 1445 at the age of 14 when he was appointedsacristan

A sacristan is an officer charged with care of the sacristy, the church, and their contents.

In ancient times, many duties of the sacrist were performed by the doorkeepers ( ostiarii), and later by the treasurers and mansionarii. The Decreta ...

at the Cathedral of Valencia

Valencia Cathedral, at greater length the Metropolitan Cathedral–Basilica of the Assumption of Our Lady of Valencia ( es, Iglesia Catedral-Basílica Metropolitana de la Asunción de Nuestra Señora de Valencia, ca-valencia, Església Cated ...

by his influential uncle, Alfons Cardinal de Borja, who had been appointed a cardinal

Cardinal or The Cardinal may refer to:

Animals

* Cardinal (bird) or Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**''Cardinalis'', genus of cardinal in the family Cardinalidae

**''Cardinalis cardinalis'', or northern cardinal, the ...

by Pope Eugene IV

Pope Eugene IV ( la, Eugenius IV; it, Eugenio IV; 1383 – 23 February 1447), born Gabriele Condulmer, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 3 March 1431 to his death in February 1447. Condulmer was a Venetian, and ...

the previous year. In 1448, Borja became canon at the cathedrals of Valencia, Barcelona, and Segorbe. His uncle, Cardinal de Borja, persuaded Pope Nicholas V

Pope Nicholas V ( la, Nicholaus V; it, Niccolò V; 13 November 1397 – 24 March 1455), born Tommaso Parentucelli, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 6 March 1447 until his death in March 1455. Pope Eugene made ...

to allow young Borja to perform this role ''in absentia

is Latin for absence. , a legal term, is Latin for "in the absence" or "while absent".

may also refer to:

* Award in absentia

* Declared death in absentia, or simply, death in absentia, legally declared death without a body

* Election in ab ...

'' and receive the associated income, so that Borja could travel to Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

. While in Rome, Rodrigo Borgia (as his surname was usually spelled in Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

) studied under Gaspare da Verona, a humanist tutor. He then studied law at Bologna

Bologna (, , ; egl, label= Emilian, Bulåggna ; lat, Bononia) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in Northern Italy. It is the seventh most populous city in Italy with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different na ...

where he graduated, not simply as Doctor of Law

A Doctor of Law is a degree in law. The application of the term varies from country to country and includes degrees such as the Doctor of Juridical Science (J.S.D. or S.J.D), Juris Doctor (J.D.), Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.), and Legum Doctor (LL ...

, but as "the most eminent and judicious jurisprudent."Monsignor Peter de Roo (1924), ''Material for a History of Pope Alexander VI, His Relatives and His Time'', (5 vols.), Bruges, Desclée, De Brouwer, volume 2, p. 29/ref> The election of his uncle, Alfons Cardinal de Borja, as

Pope Callixtus III

Pope Callixtus III ( it, Callisto III, va, Calixt III, es, Calixto III; 31 December 1378 – 6 August 1458), born Alfonso de Borgia ( va, Alfons de Borja), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 April 1455 to his ...

in 1455 enabled Borgia's appointments to other positions in the Church. These Nepotism, nepotistic appointments were characteristic of the era. Each pope during this period inevitably found himself surrounded by the servants and retainers of his predecessors who often owed their loyalty to the family of the pontiff who had appointed them. In 1455, he inherited his uncle's post as bishop of Valencia, and Callixtus appointed him Dean of Santa Maria in Játiva. The following year, he was ordained deacon

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions. Major Christian churches, such as the Catholic Chur ...

and created cardinal-deacon

A cardinal ( la, Sanctae Romanae Ecclesiae cardinalis, literally 'cardinal of the Holy Roman Church') is a senior member of the clergy of the Catholic Church. Cardinals are created by the ruling pope and typically hold the title for life. Col ...

of San Nicola in Carcere

San Nicola in Carcere (Italian, "St Nicholas in prison") is a titular church in Rome near the Forum Boarium in rione Sant'Angelo. It is one of the traditional stational churches of Lent.

History

The first church on the site was probably bui ...

. Rodrigo Borgia's appointment as cardinal only occurred after Callixtus III asked the cardinals in Rome to create three new positions in the College of Cardinals

The College of Cardinals, or more formally the Sacred College of Cardinals, is the body of all cardinals of the Catholic Church. its current membership is , of whom are eligible to vote in a conclave to elect a new pope. Cardinals are app ...

, two for his nephews Rodrigo and Luis Juan de Milà, and one for the Prince Jaime of Portugal.

In 1457, Callixtus III assigned the young Cardinal de Borja (or Borgia in Italian) to go to Ancona as a Papal legate to quell a revolt. Borgia was successful in his mission, and his uncle rewarded him with his appointment as vice-chancellor

A chancellor is a leader of a college or university, usually either the executive or ceremonial head of the university or of a university campus within a university system.

In most Commonwealth and former Commonwealth nations, the chancellor ...

of the Holy Roman Church. The position of vice-chancellor

A chancellor is a leader of a college or university, usually either the executive or ceremonial head of the university or of a university campus within a university system.

In most Commonwealth and former Commonwealth nations, the chancellor ...

was both incredibly powerful and lucrative, and Borgia held this post for 35 years until his own election to the papacy in 1492. At the end of 1457, Rodrigo Cardinal Borgia's elder brother, Pedro Luis Borgia, fell ill, so Rodrigo temporarily filled Pedro Luis' position as captain-general

Captain general (and its literal equivalent in several languages) is a high military rank of general officer grade, and a gubernatorial title.

History

The term "Captain General" started to appear in the 14th century, with the meaning of Command ...

of the papal army until he recovered. In 1458, Cardinal Borgia's uncle and greatest benefactor, Pope Callixtus, died.

In the papal election of 1458, Rodrigo Borgia was too young to seek the papacy himself, so he sought to support a cardinal who would maintain him as vice-chancellor. Borgia was one of the deciding votes in the election of Cardinal Piccolomini as Pope Pius II

Pope Pius II ( la, Pius PP. II, it, Pio II), born Enea Silvio Bartolomeo Piccolomini ( la, Aeneas Silvius Bartholomeus, links=no; 18 October 1405 – 14 August 1464), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 Augu ...

, and the new pope rewarded Borgia not only with maintaining the chancellorship but also with a lucrative abbey benefice and another titular church. In 1460, Pope Pius rebuked Cardinal Borgia for attending a private party which Pius had heard turned into an orgy. Borgia apologized for the incident but denied that there had been an orgy. Pope Pius forgave him, and the true events of the evening remain unknown. In 1462, Rodrigo Borgia had his first son, Pedro Luis, with an unknown mistress. He sent Pedro Luis to grow up in Spain. The following year, Borgia acceded to Pope Pius's call for cardinals to help fund a new crusade. Before embarking to lead the crusade personally, Pope Pius II fell ill and died, so Borgia would need to ensure the election of yet another ally to the papacy to maintain his position as vice-chancellor.

On the first ballot, the conclave of 1464 elected Borgia's friend Pietro Barbo as Pope Paul II

Pope Paul II ( la, Paulus II; it, Paolo II; 23 February 1417 – 26 July 1471), born Pietro Barbo, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States

from 30 August 1464 to his death in July 1471. When his maternal uncle Eugene IV ...

. Borgia was in high standing with the new pope and retained his positions, including that of vice-chancellor. Paul II reversed some of his predecessor's reforms that diminished the power of the chancellory. Following the election, Borgia fell ill of the plague but recovered. Borgia had two daughters, Isabella (*1467) and Girolama (*1469), with an unknown mistress. He openly acknowledged all three of his children. Pope Paul II died suddenly in 1471.

While Borgia had acquired the reputation and wealth to mount a bid for the papacy in this conclave, there were only three non-Italians, making his election a near-impossibility. Consequently, Borgia continued his previous strategy of positioning himself as kingmaker. This time, Borgia gathered the votes to make Francesco della Rovere (the uncle of future Borgia rival Giuliano della Rovere) Pope Sixtus IV

Pope Sixtus IV ( it, Sisto IV: 21 July 1414 – 12 August 1484), born Francesco della Rovere, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 August 1471 to his death in August 1484. His accomplishments as pope include ...

. Della Rovere's appeal was that he was a pious and brilliant Franciscan

, image = FrancescoCoA PioM.svg

, image_size = 200px

, caption = A cross, Christ's arm and Saint Francis's arm, a universal symbol of the Franciscans

, abbreviation = OFM

, predecessor =

, ...

monk who lacked many political connections in Rome. He seemed to be the perfect cardinal to reform the Church, and the perfect cardinal for Borgia to maintain his influence. Sixtus IV rewarded Borgia for his support by promoting him to cardinal-bishop and consecrating him as the Cardinal-Bishop of Albano

The Diocese of Albano ( la, Albanensis) is a suburbicarian see of the Roman Catholic Church in a diocese in Italy, comprising seven towns in the Province of Rome. Albano Laziale is situated some 15 kilometers from Rome, on the Appian Way.

Under ...

, requiring Borgia's ordination as a priest. Borgia also received a lucrative abbey from the pope and remained vice-chancellor. At the end of the year, the pope appointed Borgia to be the papal legate for Spain to negotiate a peace treaty between Castile and Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to s ...

and to solicit their support for another crusade. In 1472, Borgia was appointed to be the papal chamberlain until his departure to Spain. Borgia arrived in his native Aragon in the summer, reuniting with family and meeting with King Juan II and Prince Ferdinand. The pope gave Cardinal Borgia discretion over whether to give dispensation for Ferdinand

Ferdinand is a Germanic name composed of the elements "protection", "peace" (PIE "to love, to make peace") or alternatively "journey, travel", Proto-Germanic , abstract noun from root "to fare, travel" (PIE , "to lead, pass over"), and "co ...

's marriage to his first cousin Isabella of Castile

Isabella I ( es, Isabel I; 22 April 1451 – 26 November 1504), also called Isabella the Catholic (Spanish: ''la Católica''), was Queen of Castile from 1474 until her death in 1504, as well as Queen consort of Aragon from 1479 until 1504 b ...

, and Borgia decided in favour of approving the marriage. The couple named Borgia to be the godfather of their first son in recognition of this decision. The marriage of Ferdinand and Isabella was critical in the unification of Castile and Aragon into Spain. Borgia also negotiated peace between Castile and Aragon and an end to the civil wars in the latter Kingdom, gaining the favour of the future King Ferdinand who would go on to promote the interests of the Borgia family in Aragon. Borgia returned to Rome the following year, narrowly surviving a storm that sunk a nearby galley that was carrying 200 men of the Borgia household. Back in Rome, Borgia began his affair with Vannozza dei Cattenei which would yield four children: Cesare in 1475, Giovanni in 1474 or 1476, Lucrezia in 1480, and Gioffre in 1482. In 1476, Pope Sixtus appointed Borgia to be the cardinal-bishop of Porto. In 1480, the pope legitimized Cesare as a favour to Cardinal Borgia, and in 1482, the pope began to appoint the seven-year-old to church positions, demonstrating Borgia's intention to use his influence to promote his children. Contemporaneously, Borgia continued to add to his list of benefices, becoming the wealthiest cardinal by 1483. He also become Dean of the College of Cardinals

The dean of the College of Cardinals ( la, Decanus Collegii Sanctae Romanae Ecclesiae Cardinalium) presides over the College of Cardinals in the Roman Catholic Church, serving as ''primus inter pares'' (first among equals). The position was establi ...

in that year. In 1484, Pope Sixtus IV died, necessitating another election for Borgia to manipulate to his advantage.

Borgia was wealthy and powerful enough to mount a bid, but he faced competition from Giuliano della Rovere, the late pope's nephew. Della Rovere's faction had the advantage of being incredibly large as Sixtus had appointed many of the cardinals who would participate in the election. Borgia's attempts to gather enough votes included bribery and leveraging his close ties to Naples and Aragon. However, many of the Spanish cardinals were absent from the conclave and della Rovere's faction had an overwhelming advantage. Della Rovere chose to promote Cardinal Cibo as his preferred candidate, and Cibo wrote to the Borgia faction wanting to strike a deal. Once again, Borgia played kingmaker and conceded to Cardinal Cibo who became Pope Innocent VIII

Pope Innocent VIII ( la, Innocentius VIII; it, Innocenzo VIII; 1432 – 25 July 1492), born Giovanni Battista Cybo (or Cibo), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 29 August 1484 to his death in July 1492. Son of th ...

. Again, Borgia retained his position of vice-chancellor, successfully holding this position over the course of five papacies and four elections.

In 1485, Pope Innocent VIII nominated Borgia to become the Archbishop of Seville

The Archdiocese of Seville is part of the Catholic Church in Seville, Spain. The Diocese of Seville was founded in the 3rd century. It was raised to the level of an archdiocese in the 4th century. The current archbishop is José Ángel Saiz Mene ...

, a position that King Ferdinand II

Ferdinand II ( an, Ferrando; ca, Ferran; eu, Errando; it, Ferdinando; la, Ferdinandus; es, Fernando; 10 March 1452 – 23 January 1516), also called Ferdinand the Catholic (Spanish: ''el Católico''), was King of Aragon and Sardinia from ...

wanted for his own son. In response, Ferdinand angrily seized the Borgia estates in Aragon and imprisoned Borgia's son Pedro Luis. However, Borgia healed the relationship by turning down this appointment. Pope Innocent, at the urging of his close ally Giuliano della Rovere, decided to declare war against Naples, but Milan, Florence, and Aragon chose to support Naples over the pope. Borgia led the opposition within the College of Cardinals to this war, and King Ferdinand rewarded Borgia by making his son Pedro Luis the Duke of Gandia

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are ranke ...

and arranging a marriage between his cousin Maria Enriquez and the new duke. Now, the Borgia family was directly tied to the royal families of Spain and Naples. While Borgia gained the favour of Spain, he stood opposed to the pope and the della Rovere family. As a part of his war opposition, Borgia sought to obstruct an alliance negotiation between the papacy and France. These negotiations were unsuccessful and in July 1486, the pope capitulated and ended the war. In 1488, Borgia's son Pedro Luis died, and Juan Borgia became the new duke of Gandia. In the following year, Borgia hosted the wedding ceremony between Orsino Orsini

Orsino Orsini Migliorati (1473–1500) was the husband of Giulia "La Bella" Farnese (1474–1524), the mistress of Pope Alexander VI.

Family

The only son of Ludovico Orsini Migliorati (1425-1489) and Adriana de Mila (b. 1434), Orsino was relate ...

and Giulia Farnese

Giulia Farnese (1474 – 23 March 1524) was an Italian noblewoman, a mistress to Pope Alexander VI, and the sister of Pope Paul III. Known as ''Giulia la bella'', meaning "Julia the beautiful" in Italian, Giulia was a member of the noble Farnese ...

, and within a few months, Farnese had become Borgia's new mistress. She was 15, and he was 58. Borgia continued to acquire new benefices with their large streams of income, including the bishopric of Majorca and Eger in Hungary. In 1492, Pope Innocent VIII died. Since Borgia was 61, this was likely his last chance to become pope.

Appearance and personality

Peter de Roo gives a flattering summary of contemporary descriptions of Alexander, relating him to have been "of a medium complexion, with dark eyes and slightly full lips, of robust health ..; in later life, he reports that "his aspectas declared

As, AS, A. S., A/S or similar may refer to:

Art, entertainment, and media

* A. S. Byatt (born 1936), English critic, novelist, poet and short story writer

* "As" (song), by Stevie Wonder

* , a Spanish sports newspaper

* , an academic male voice ...

to be venerable and far more

august than an ordinary human appearance", and that he was "so familiar with Holy Writ

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They differ from literature by being a compilation or discussion of beliefs, mythologies, ritual pra ...

, that his speeches were fairly sparkling with well-chosen texts of the Sacred Books".

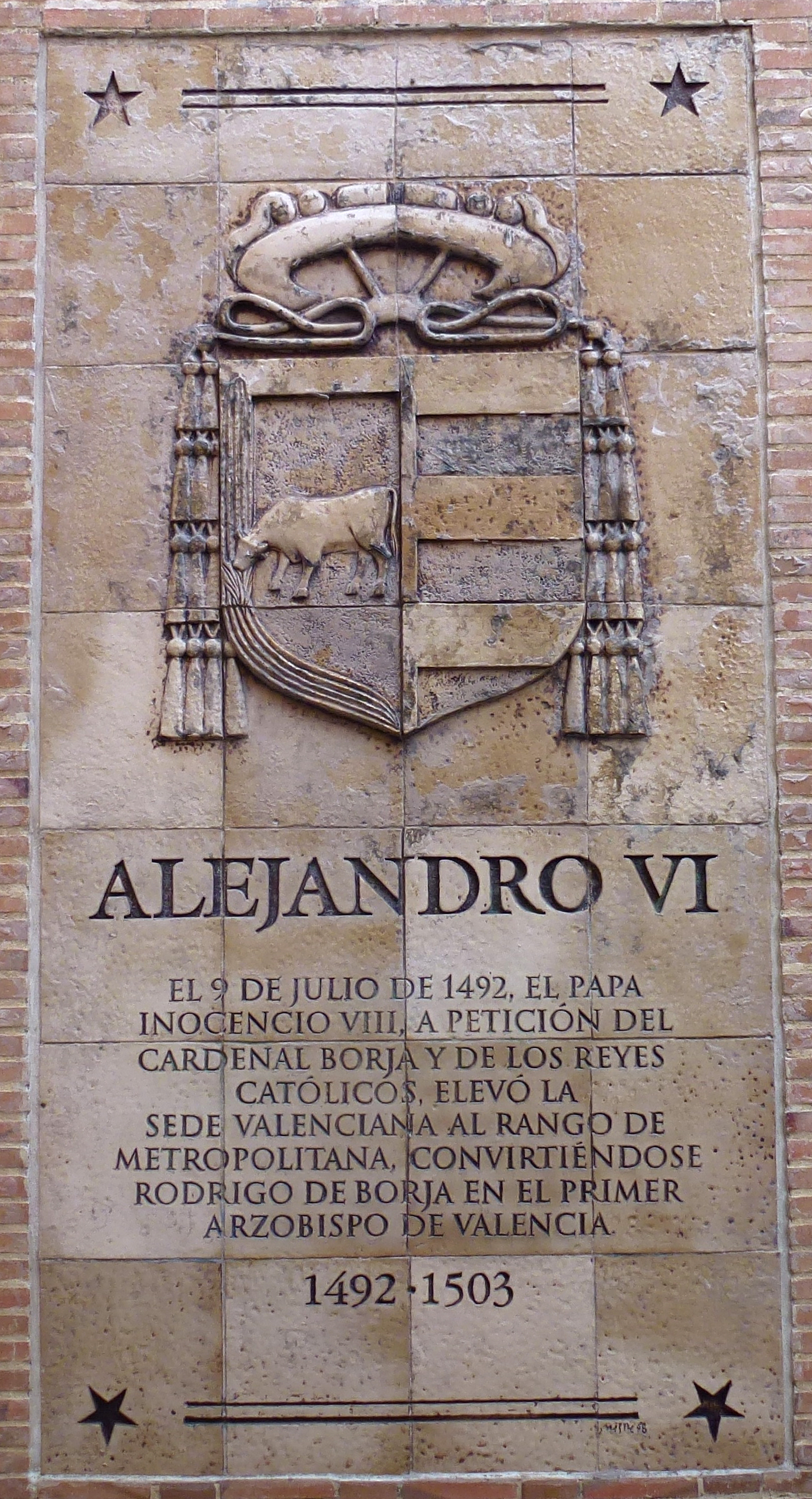

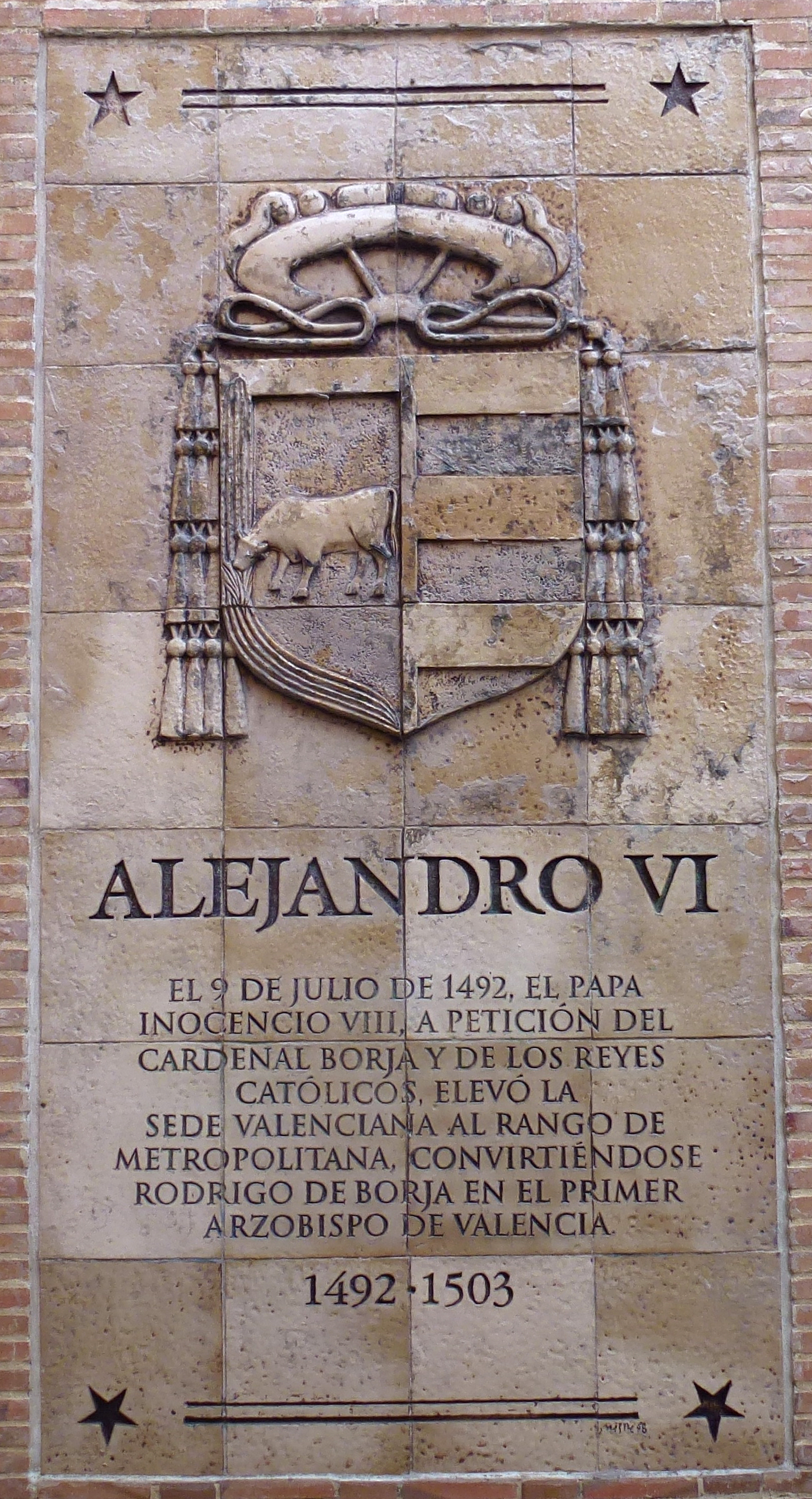

Archbishop of Valencia

When his uncle Alonso de Borja ( bishop of Valencia) was elected Pope Callixtus III, he "inherited" the post of bishop of Valencia. Sixteen days before the death ofPope Innocent VIII

Pope Innocent VIII ( la, Innocentius VIII; it, Innocenzo VIII; 1432 – 25 July 1492), born Giovanni Battista Cybo (or Cibo), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 29 August 1484 to his death in July 1492. Son of th ...

, he proposed Valencia as a metropolitan

Metropolitan may refer to:

* Metropolitan area, a region consisting of a densely populated urban core and its less-populated surrounding territories

* Metropolitan borough, a form of local government district in England

* Metropolitan county, a typ ...

see and became the first archbishop of Valencia. When Rodrigo de Borgia was elected pope as Alexander VI following the death of Innocent VIII, his son Cesare Borgia "inherited" the post as second archbishop of Valencia. The third and the fourth archbishops of Valencia were Juan de Borja and Pedro Luis de Borja

Pedro Luis de Borja, Duke of Spoleto and Marquess of Civitavecchia (1432 – 26 September 1458) was the younger brother of Rodrigo Borgia and nephew of Cardinal Alonso de Borja, who in 1455 became Pope Callixtus III. He was called Don Pedro Luis.

...

, grand-nephews of Alexander VI.Gaetano Moroni

Gaetano Moroni (17 October 1802, Rome – 3 November 1883, Rome) was an Italian writer on the history and contemporary structure of the Catholic Church and an official of the papal court in Rome. He was the author of the well-known ''Dizionari ...

, ''Dizionario di Erudizione Storico-Ecclesiastica da S. Pietro sino ai nostri giorni''vol. 6, p. 50

Election

There was change in the constitution of the College of Cardinals during the course of the 15th century, especially under Sixtus IV and Innocent VIII. Of the 27 cardinals alive in the closing months of the reign of Innocent VIII no fewer than 10 werecardinal-nephew

A cardinal-nephew ( la, cardinalis nepos; it, cardinale nipote; es, valido de su tío; pt, cardeal-sobrinho; french: prince de fortune)Signorotto and Visceglia, 2002, p. 114. Modern French scholarly literature uses the term "cardinal-neveu'". ...

s, eight were crown nominees, four were Roman nobles and one other had been given the cardinalate in recompense for his family's service to the Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of R ...

; only four were able career churchmen.

On the death of Pope Innocent VIII

Pope Innocent VIII ( la, Innocentius VIII; it, Innocenzo VIII; 1432 – 25 July 1492), born Giovanni Battista Cybo (or Cibo), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 29 August 1484 to his death in July 1492. Son of th ...

on 25 July 1492, the three likely candidates for the Papacy

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

were the 61-year-old Borgia, seen as an independent candidate, Ascanio Sforza

Ascanio Maria Sforza Visconti (3 March 1455 – 28 May 1505) was an Italian Cardinal of the Catholic Church. Generally known as a skilled diplomat who played a major role in the election of Rodrigo Borgia as Pope Alexander VI, Sforza served a ...

for the Milanese, and Giuliano della Rovere, seen as a pro-French candidate.

It was rumoured but not substantiated that Borgia succeeded in buying the largest number of votes and Sforza, in particular, was bribed with four mule-loads of silver. Mallett shows that Borgia was in the lead from the start and that the rumours of bribery began after the election with the distribution of benefices; Sforza and della Rovere were just as willing and able to bribe as anyone else. The benefices and offices granted to Sforza, moreover, would be worth considerably more than four mule-loads of silver. Johann Burchard

Johann Burchard, also spelled Johannes Burchart or Burkhart (c.1450–1506) was an Alsatian-born priest and chronicler during the Italian Renaissance. He spent his entire career at the papal Courts of Sixtus IV, Innocent VIII, Alexander VI, Piu ...

, the conclave's master of ceremonies and a leading figure of the papal household under several popes, recorded in his diary that the 1492 conclave was a particularly expensive campaign. Della Rovere was bankrolled to the cost of 200,000 gold ducat

The ducat () coin was used as a trade coin in Europe from the later Middle Ages from the 13th to 19th centuries. Its most familiar version, the gold ducat or sequin containing around of 98.6% fine gold, originated in Venice in 1284 and gained ...

s by King Charles VIII of France, with another 100,000 supplied by the Republic of Genoa

The Republic of Genoa ( lij, Repúbrica de Zêna ; it, Repubblica di Genova; la, Res Publica Ianuensis) was a medieval and early modern maritime republic from the 11th century to 1797 in Liguria on the northwestern Italian coast. During the La ...

.Johann Burchard, ''Diaries 1483–1492'' (translation: A.H. Matthew, London, 1910)

The leading candidates in the first ballot were Oliviero Carafa of Sforza's party with nine votes, and Giovanni Michiel and Jorge Costa, both of della Rovere's party with seven votes each. Borgia himself gathered seven votes. However, Borgia convinced Sforza to join with his camp through the promise of being appointed vice-chancellor as well as bribes that included benefices and perhaps four mule-loads of silver. With Sforza now canvassing for votes, Borgia's election was assured. Borgia was elected on 11 August 1492 and assumed the name of Alexander VI (due to confusion about the status of Pope Alexander V

Peter of Candia, also known as Peter Phillarges (c. 1339 – May 3, 1410), named as Alexander V ( la, Alexander PP.

V; it, Alessandro V), was an antipope elected by the Council of Pisa during the Western Schism (1378–1417). He reigned briefly ...

, elected by the Council of Pisa

The Council of Pisa was a controversial ecumenical council of the Catholic Church held in 1409. It attempted to end the Western Schism by deposing Benedict XIII (Avignon) and Gregory XII (Rome) for schism and manifest heresy. The College o ...

). Many inhabitants of Rome were happy with their new pope because he was a generous and competent administrator who had served for decades as vice-chancellor.

Early years in office

In contrast to the preceding pontificate, Pope Alexander VI adhered initially to strict administration of justice and orderly government. Before long, though, he began endowing his relatives at the Church's and at his neighbours' expense.

In contrast to the preceding pontificate, Pope Alexander VI adhered initially to strict administration of justice and orderly government. Before long, though, he began endowing his relatives at the Church's and at his neighbours' expense. Cesare Borgia

Cesare Borgia (; ca-valencia, Cèsar Borja ; es, link=no, César Borja ; 13 September 1475 – 12 March 1507) was an Italian ex-cardinal and ''condottiero'' (mercenary leader) of Aragonese (Spanish) origin, whose fight for power was a major i ...

, his son, while a youth of seventeen and a student at Pisa

Pisa ( , or ) is a city and ''comune'' in Tuscany, central Italy, straddling the Arno just before it empties into the Ligurian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa. Although Pisa is known worldwide for its leaning tower, the ci ...

, was made Archbishop

In Christian denominations, an archbishop is a bishop of higher rank or office. In most cases, such as the Catholic Church, there are many archbishops who either have jurisdiction over an ecclesiastical province in addition to their own archdio ...

of Valencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the autonomous community of Valencia and the third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is also the capital of the province of the same name. The wider urban area al ...

, and Giovanni Borgia inherited the Spanish Dukedom of Gandia

Gandia ( es, Gandía) is a city and municipality in the Valencian Community, eastern Spain on the Mediterranean. Gandia is located on the Costa del Azahar (or ''Costa dels Tarongers''), south of Valencia and north of Alicante. Vehicles can acc ...

, the Borgias' ancestral home in Spain. For the Duke of Gandia and for Gioffre, also known as Goffredo, the Pope proposed to carve fiefs out of the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope fro ...

and the Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples ( la, Regnum Neapolitanum; it, Regno di Napoli; nap, Regno 'e Napule), also known as the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was ...

. Among the fiefs destined for the duke of Gandia were Cerveteri

Cerveteri () is a town and '' comune'' of northern Lazio in the region of the Metropolitan City of Rome. Known by the ancient Romans as Caere, and previously by the Etruscans as Caisra or Cisra, and as Agylla (or ) by the Greeks, its modern na ...

and Anguillara, lately acquired by Virginio Orsini, head of that powerful house. This policy brought Ferdinand I of Naples

Ferdinando Trastámara d'Aragona, of the Naples branch, universally known as Ferrante and also called by his contemporaries Don Ferrando and Don Ferrante (2 June 1424, in Valencia – 25 January 1494, in Naples), was the only son, illegitimate, of ...

into conflict with Alexander, as well as with Cardinal della Rovere, whose candidature for the papacy had been backed by Ferdinand. Della Rovere fortified himself in his bishopric of Ostia at the Tiber

The Tiber ( ; it, Tevere ; la, Tiberis) is the third-longest river in Italy and the longest in Central Italy, rising in the Apennine Mountains in Emilia-Romagna and flowing through Tuscany, Umbria, and Lazio, where it is joined by th ...

's mouth as Alexander formed a league against Naples (25 April 1493) and prepared for war.

Ferdinand allied himself with Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico ...

, Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city ...

and Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

. He also appealed to Spain for help, but Spain was eager to be on good terms with the papacy to obtain the title to the recently discovered New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

. Alexander, in the bull ''Inter caetera

''Inter caetera'' ('Among other orks) was a papal bull issued by Pope Alexander VI on the 4 May () 1493, which granted to the Catholic Monarchs King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile all lands to the "west and south" of ...

'' on 4 May 1493, divided the title between Spain and Portugal along a demarcation line. This became the basis of the Treaty of Tordesillas

The Treaty of Tordesillas, ; pt, Tratado de Tordesilhas . signed in Tordesillas, Spain on 7 June 1494, and authenticated in Setúbal, Portugal, divided the newly discovered lands outside Europe between the Portuguese Empire and the Spanish Em ...

.

French involvement

Pope Alexander VI made many alliances to secure his position. He sought help from

Pope Alexander VI made many alliances to secure his position. He sought help from Charles VIII of France

Charles VIII, called the Affable (french: l'Affable; 30 June 1470 – 7 April 1498), was King of France from 1483 to his death in 1498. He succeeded his father Louis XI at the age of 13.Paul Murray Kendall, ''Louis XI: The Universal Spider'' (Ne ...

(1483–1498), who was allied to Ludovico "il Moro" Sforza (the Moor, so-called because of his swarthy complexion), the ''de facto'' Duke of Milan, who needed French support to legitimise his rule. As King Ferdinand I of Naples

Ferdinando Trastámara d'Aragona, of the Naples branch, universally known as Ferrante and also called by his contemporaries Don Ferrando and Don Ferrante (2 June 1424, in Valencia – 25 January 1494, in Naples), was the only son, illegitimate, of ...

was threatening to come to the aid of the rightful duke Gian Galeazzo Sforza

Gian Galeazzo Sforza (20 June 1469 – 21 October 1494), also known as Giovan Galeazzo Sforza, was the sixth Duke of Milan.

Early life

Born in Abbiategrasso, he was only seven years old when in 1476 his father, Galeazzo Maria Sforza, was assas ...

, the husband of his granddaughter Isabella, Alexander encouraged the French king in his plan for the conquest of Naples.

But Alexander, always ready to seize opportunities to aggrandize his family, then adopted a double policy. Through the intervention of the Spanish ambassador he made peace with Naples in July 1493 and cemented the peace by a marriage between his son Gioffre and Doña Sancha, another granddaughter of Ferdinand I. In order to dominate the College of Cardinals

The College of Cardinals, or more formally the Sacred College of Cardinals, is the body of all cardinals of the Catholic Church. its current membership is , of whom are eligible to vote in a conclave to elect a new pope. Cardinals are app ...

more completely, Alexander, in a move that created much scandal, created 12 new cardinals. Among the new cardinals was his own son Cesare, then only 18 years old. Alessandro Farnese (later Pope Paul III), the brother of one of the Pope's mistresses, Giulia Farnese

Giulia Farnese (1474 – 23 March 1524) was an Italian noblewoman, a mistress to Pope Alexander VI, and the sister of Pope Paul III. Known as ''Giulia la bella'', meaning "Julia the beautiful" in Italian, Giulia was a member of the noble Farnese ...

, was also among the newly created cardinals.

On 25 January 1494, Ferdinand I died and was succeeded by his son Alfonso II (1494–1495). Charles VIII of France

Charles VIII, called the Affable (french: l'Affable; 30 June 1470 – 7 April 1498), was King of France from 1483 to his death in 1498. He succeeded his father Louis XI at the age of 13.Paul Murray Kendall, ''Louis XI: The Universal Spider'' (Ne ...

now advanced formal claims on the Kingdom of Naples. Alexander authorised him to pass through Rome, ostensibly on a crusade

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were ...

against the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

, without mentioning Naples. But when the French invasion became a reality Pope Alexander VI became alarmed, recognised Alfonso II as king of Naples, and concluded an alliance with him in exchange for various fiefs for his sons (July 1494). A military response to the French threat was set in motion: a Neapolitan army was to advance through Romagna

Romagna ( rgn, Rumâgna) is an Italian historical region that approximately corresponds to the south-eastern portion of present-day Emilia-Romagna, North Italy. Traditionally, it is limited by the Apennines to the south-west, the Adriatic to th ...

and attack Milan, while the fleet was to seize Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

. Both expeditions were badly conducted and failed, and on 8 September Charles VIII crossed the Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Sw ...

and joined Ludovico il Moro at Milan. The Papal States were in turmoil, and the powerful Colonna

The House of Colonna, also known as ''Sciarrillo'' or ''Sciarra'', is an Italian noble family, forming part of the papal nobility. It was powerful in medieval and Renaissance Rome, supplying one pope (Martin V) and many other church and pol ...

faction seized Ostia in the name of France. Charles VIII rapidly advanced southward, and after a short stay in Florence, set out for Rome (November 1494).

Alexander appealed to Ascanio Sforza

Ascanio Maria Sforza Visconti (3 March 1455 – 28 May 1505) was an Italian Cardinal of the Catholic Church. Generally known as a skilled diplomat who played a major role in the election of Rodrigo Borgia as Pope Alexander VI, Sforza served a ...

and even to the Ottoman Sultan

Sultan (; ar, سلطان ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it c ...

Bayazid II

Bayezid II ( ota, بايزيد ثانى, Bāyezīd-i s̱ānī, 3 December 1447 – 26 May 1512, Turkish: ''II. Bayezid'') was the eldest son and successor of Mehmed II, ruling as Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1481 to 1512. During his reign, B ...

for help. He tried to collect troops and put Rome in a state of defence, but his position was precarious. When the Orsini offered to admit the French to their castles, Alexander had no choice but to come to terms with Charles. On 31 December, Charles VIII entered Rome with his troops, the cardinals of the French faction, and Giuliano della Rovere. Alexander now feared that Charles might depose him for simony

Simony () is the act of selling church offices and roles or sacred things. It is named after Simon Magus, who is described in the Acts of the Apostles as having offered two disciples of Jesus payment in exchange for their empowering him to i ...

, and that the king would summon a council to nominate a new pope. Alexander was able to win over the bishop of Saint-Malo

The former Breton and French Catholic Diocese of Saint-Malo ( la, Dioecesis Alethensis, then la, Dioecesis Macloviensis, label=none) existed from at least the 7th century until the French Revolution. Its seat was at Aleth up to some point in th ...

, who had much influence over the king, by making him a cardinal. Alexander agreed to send Cesare as legate to Naples with the French army; to deliver Cem Sultan

Cem Sultan (also spelled Djem or Jem) or Sultan Cem or Şehzade Cem (December 22, 1459 – February 25, 1495, ; ota, جم سلطان, Cem sulṭān; tr, Cem Sultan; french: Zizim), was a claimant to the Ottoman throne in the 15th century.

Ce ...

, held as a hostage, to Charles VIII, and to give Charles Civitavecchia

Civitavecchia (; meaning "ancient town") is a city and ''comune'' of the Metropolitan City of Rome in the central Italian region of Lazio. A sea port on the Tyrrhenian Sea, it is located west-north-west of Rome. The harbour is formed by two pier ...

(16 January 1495). On 28 January Charles VIII departed for Naples with Cem and Cesare, but the latter slipped away to Spoleto

Spoleto (, also , , ; la, Spoletum) is an ancient city in the Italian province of Perugia in east-central Umbria on a foothill of the Apennines. It is S. of Trevi, N. of Terni, SE of Perugia; SE of Florence; and N of Rome.

History

Sp ...

. Neapolitan resistance collapsed, and Alfonso II fled and abdicated in favour of his son Ferdinand II. Ferdinand was abandoned by all and also had to escape, and the Kingdom of Naples was conquered with surprising ease.

French in retreat

A reaction against Charles VIII soon set in, for all the European powers were alarmed at his success. On 31 March 1495 the Holy League was formed between the pope, the emperor,Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

, Ludovico il Moro and Ferdinand of Spain

Ferdinand II ( an, Ferrando; ca, Ferran; eu, Errando; it, Ferdinando; la, Ferdinandus; es, Fernando; 10 March 1452 – 23 January 1516), also called Ferdinand the Catholic (Spanish: ''el Católico''), was King of Aragon and Sardinia from ...

. The League was ostensibly formed against the Turks, but in reality it was made to expel the French from Italy. Charles VIII had himself crowned King of Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adm ...

on 12 May, but a few days later began his retreat northward. He met the League at Fornovo and cut his way through them and was back in France by November. Ferdinand II was reinstated at Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adm ...

soon afterwards, with Spanish help. The expedition, if it produced no material results, demonstrated the foolishness of the so-called "politics of equilibrium", the Medicean doctrine of preventing one of the Italian principates from overwhelming the rest and uniting them under its hegemony.

Charles VIII's belligerence in Italy had made it transparent that the "politics of equilibrium" did nothing but render the country unable to defend itself against a powerful invading force. Italy was shown to be very vulnerable to the predations of the powerful nation-states, France and Spain, that had forged themselves during the previous century. Alexander VI now followed the general tendency of all the princes of the day to crush the great feudatories and establish a centralized despotism. In this manner, he was able to take advantage of the defeat of the French in order to break the power of the Orsini. From that time on, Alexander was able to build himself an effective power base in the Papal States.

Virginio Orsini, who had been captured by the Spanish, died a prisoner at Naples, and the Pope confiscated his property. The rest of the Orsini clan still held out, defeating the papal troops sent against them under

Virginio Orsini, who had been captured by the Spanish, died a prisoner at Naples, and the Pope confiscated his property. The rest of the Orsini clan still held out, defeating the papal troops sent against them under Guidobaldo da Montefeltro

Guidobaldo (Guido Ubaldo) da Montefeltro (25 January 1472 – 10 April 1508), also known as Guidobaldo I, was an Italian condottiero and the Duke of Urbino from 1482 to 1508.

Biography

Born in Gubbio, he succeeded his father Federico da Montefe ...

, Duke of Urbino

Urbino ( ; ; Romagnol: ''Urbìn'') is a walled city in the Marche region of Italy, south-west of Pesaro, a World Heritage Site notable for a remarkable historical legacy of independent Renaissance culture, especially under the patronage of F ...

and Giovanni Borgia, Duke of Gandia, at Soriano (January 1497). Peace was made through Venetian mediation, the Orsini paying 50,000 ducats in exchange for their confiscated lands; the Duke of Urbino, whom they had captured, was left by the pope to pay his own ransom. The Orsini remained very powerful, and Pope Alexander VI could count on none but his 3,000 Spanish troops. His only success had been the capture of Ostia and the submission of the Francophile cardinals Colonna and Savelli.

Then occurred a major domestic tragedy for the house of Borgia. On 14 June, his son the Duke of Gandia

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are ranke ...

, who was lately created Duke of Benevento

Benevento (, , ; la, Beneventum) is a city and '' comune'' of Campania, Italy, capital of the province of Benevento, northeast of Naples. It is situated on a hill above sea level at the confluence of the Calore Irpino (or Beneventano) and the ...

and had a questionable lifestyle, disappeared; the next day, his corpse was found in the Tiber. Alexander, overwhelmed with grief, shut himself up in Castel Sant'Angelo

The Mausoleum of Hadrian, usually known as Castel Sant'Angelo (; English: ''Castle of the Holy Angel''), is a towering cylindrical building in Parco Adriano, Rome, Italy. It was initially commissioned by the Roman Emperor Hadrian as a mausol ...

. He declared that henceforth the moral reform of the Church would be the sole object of his life. Every effort was made to discover the assassin. No conclusive explanation was ever reached, and it may be that the crime was simply as a result of one of the Duke's sexual liaisons.

Crime

There is no evidence that the Borgias resorted to poisoning, judicial murder, or extortion to fund their schemes and the defense of the Papal States. The only contemporary accusations of poisoning were from some of their servants, extracted under torture by Alexander's bitter enemy Della Rovere, who succeeded him as PopeJulius II

Pope Julius II ( la, Iulius II; it, Giulio II; born Giuliano della Rovere; 5 December 144321 February 1513) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 1503 to his death in February 1513. Nicknamed the Warrior Pope or the ...

.

Savonarola

The debased state of the curia was a major scandal. Opponents, such as the powerful Florentine friar

The debased state of the curia was a major scandal. Opponents, such as the powerful Florentine friar Girolamo Savonarola

Girolamo Savonarola, OP (, , ; 21 September 1452 – 23 May 1498) or Jerome Savonarola was an Italian Dominican friar from Ferrara and preacher active in Renaissance Florence. He was known for his prophecies of civic glory, the destruction of ...

, launched invectives against papal corruption and appealed for a general council to confront the papal abuses. Alexander is reported to have been reduced to laughter when Savonarola's denunciations were related to him. Nevertheless, he appointed Sebastian Maggi to investigate the friar, and he responded on 16 October 1495:

The hostility of Savonarola seems to have been political rather than personal, and the friar sent a letter of condolence to the pope on the death of the Duke of Gandia; "Faith, most Holy Father, is the one and true source of peace and consolation... Faith alone brings consolation from a far-off country." But eventually the Florentines tired of the friar's moralising and the Florentine government condemned the reformer to death, executing him on 23 May 1498.

Familial aggrandizement

The prominent Italian families looked down on the Spanish Borgia family, and they resented their power, which they sought for themselves. This is, at least partially, why both Pope Callixtus III and Pope Alexander VI gave powers to family members whom they could trust. In these circumstances, Alexander, feeling more than ever that he could rely only on his own kin, turned his thoughts to further family aggrandizement. He had annulled Lucrezia's marriage toGiovanni Sforza Giovanni Sforza d'Aragona (5 July 1466 – 27 July 1510) was an Italian condottiero, lord of Pesaro and Gradara from 1483 until his death. He is best known as the first husband of Lucrezia Borgia. Their marriage was annulled on claims of his impote ...

, who had responded to the suggestion that he was impotent with the unsubstantiated counter-claim that Alexander and Cesare indulged in incestuous relations with Lucrezia, in 1497. Unable to arrange a union between Cesare and the daughter of King Frederick IV of Naples

Frederick (April 19, 1452 – November 9, 1504), sometimes called Frederick IV or Frederick of Aragon, was the last Kingdom of Naples, King of Naples from the Neapolitan branch of the House of Trastámara, ruling from 1496 to 1501. He was the seco ...

(who had succeeded Ferdinand II the previous year), he induced Frederick by threats to agree to a marriage between the Duke of Bisceglie

Bisceglie (; nap, label= Biscegliese, Vescégghie) is a city and municipality of 55,251 inhabitants in the province of Barletta-Andria-Trani, in the Apulia region (''Italian'': ''Puglia''), in southern Italy. The municipality has the fourth h ...

, a natural son of Alfonso II, and Lucrezia. Alexander and the new French king Louis XII

Louis XII (27 June 14621 January 1515), was King of France from 1498 to 1515 and King of Naples from 1501 to 1504. The son of Charles, Duke of Orléans, and Maria of Cleves, he succeeded his 2nd cousin once removed and brother in law at the tim ...

entered a secret agreement; in exchange for a bull of divorce between the king and Joan of France (so he could marry Anne of Brittany

Anne of Brittany (; 25/26 January 1477 – 9 January 1514) was reigning Duchess of Brittany from 1488 until her death, and Queen of France from 1491 to 1498 and from 1499 to her death. She is the only woman to have been queen consort of France ...

) and making Georges d'Amboise

Georges d'Amboise (1460 – May 25, 1510) was a French Roman Catholic cardinal and minister of state. He belonged to the house of Amboise, a noble family possessed of considerable influence: of his nine brothers, four were bishops. His father, ...

(the king's chief advisor) the cardinal of Rouen

Rouen (, ; or ) is a city on the River Seine in northern France. It is the prefecture of the region of Normandy and the department of Seine-Maritime. Formerly one of the largest and most prosperous cities of medieval Europe, the population ...

, Cesare was given the duchy of Valentinois (chosen because it was consistent with his nickname, Valentino), military assistance to help him subjugate the feudal princelings of papal Romagna, and a princess bride, Charlotte of Albret

Charlotte of Albret (1480 – 11 March 1514), Dame de Châlus, was a wealthy French noblewoman of the Albret family. She was the sister of King John III of Navarre and the wife of the widely notorious Cesare Borgia, whom she married in 1499. She ...

from the Kingdom of Navarre

The Kingdom of Navarre (; , , , ), originally the Kingdom of Pamplona (), was a Basque kingdom that occupied lands on both sides of the western Pyrenees, alongside the Atlantic Ocean between present-day Spain and France.

The medieval state took ...

.

Alexander hoped that Louis XII's help would be more profitable to his house than that of Charles VIII had been. In spite of the remonstrances of Spain and of the Sforza, he allied himself with France in January 1499 and was joined by Venice. By autumn Louis XII was in Italy expelling Lodovico Sforza from Milan. With French success seemingly assured, the Pope determined to deal drastically with Romagna, which although nominally under papal rule was divided into a number of practically independent lordships on which Venice, Milan, and Florence cast hungry eyes. Cesare, empowered by the support of the French, began to attack the turbulent cities one by one in his capacity as nominated ''gonfaloniere

The Gonfalonier (in Italian: ''Gonfaloniere'') was the holder of a highly prestigious communal office in medieval and Renaissance Italy, notably in Florence and the Papal States. The name derives from ''gonfalone'' (in English, gonfalon), the t ...

'' (standard bearer) of the church. But the expulsion of the French from Milan and the return of Lodovico Sforza interrupted his conquests, and he returned to Rome early in 1500.

The Jubilee (1500)

In the Jubilee year 1500, Alexander ushered in the custom of opening a holy door on Christmas Eve and closing it on Christmas Day the following year. After consulting with his Master of Ceremonies,Johann Burchard

Johann Burchard, also spelled Johannes Burchart or Burkhart (c.1450–1506) was an Alsatian-born priest and chronicler during the Italian Renaissance. He spent his entire career at the papal Courts of Sixtus IV, Innocent VIII, Alexander VI, Piu ...

, Pope Alexander VI opened the first holy door in St. Peter's Basilica

The Papal Basilica of Saint Peter in the Vatican ( it, Basilica Papale di San Pietro in Vaticano), or simply Saint Peter's Basilica ( la, Basilica Sancti Petri), is a church built in the Renaissance style located in Vatican City, the papal e ...

on Christmas Eve 1499, and papal representatives opened the doors in the other three patriarchal basilicas. For this, Pope Alexander had a new opening created in the ''portico

A portico is a porch leading to the entrance of a building, or extended as a colonnade, with a roof structure over a walkway, supported by columns or enclosed by walls. This idea was widely used in ancient Greece and has influenced many cul ...

'' of St. Peter's and commissioned a marble door.

Alexander was carried in the ''sedia gestatoria

The ''sedia gestatoria'' (, literally 'chair for carrying') or gestatorial chair is a ceremonial throne on which popes were carried on shoulders until 1978, which was later replaced outdoors in part with the popemobile. It consists of a richly a ...

'' to St. Peter's. He and his assistants, bearing candles, processed to the holy door, as the choir chanted Psalm 118:19–20. The pope knocked on the door three times, workers moved it from the inside, and everyone then crossed the threshold to enter into a period of penance and reconciliation. Thus, Pope Alexander formalized the rite and began a longstanding tradition that is still in practice. Similar ceremonies were held at the other three basilicas.

Alexander instituted a special rite for the closing of a holy door, as well. On the Feast of the Epiphany

Epiphany ( ), also known as Theophany in Eastern Christian traditions, is a Christian feast day that celebrates the revelation (theophany) of God incarnate as Jesus Christ.

In Western Christianity, the feast commemorates principally (but not ...

in 1501, two cardinals began to seal the holy door with two bricks, one silver and one gold. ''Sampietrini'' (basilica workers) completed the seal, placing specially-minted coins and medals inside the wall.

Slavery

While the explorers of Spain imposed a form of slavery called "encomienda

The ''encomienda'' () was a Spanish labour system that rewarded conquerors with the labour of conquered non-Christian peoples. The labourers, in theory, were provided with benefits by the conquerors for whom they laboured, including military ...

" on the indigenous peoples they met in the New World, some popes had spoken out against the practice of slavery. In 1435, Pope Eugene IV

Pope Eugene IV ( la, Eugenius IV; it, Eugenio IV; 1383 – 23 February 1447), born Gabriele Condulmer, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 3 March 1431 to his death in February 1447. Condulmer was a Venetian, and ...

had issued an attack on slavery in the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; es, :es:Canarias, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to ...

in his papal bull '' Sicut dudum'', which included the excommunication of all those who engaged in the slave trade with native chiefs there. A form of indentured servitude

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an " indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repayme ...

was allowed, being similar to a peasant's duty to his liege lord

Homage (from Medieval Latin , lit. "pertaining to a man") in the Middle Ages was the ceremony in which a feudal tenant or vassal pledged reverence and submission to his feudal lord, receiving in exchange the symbolic title to his new position (inv ...

in Europe.

In the wake of Columbus

Columbus is a Latinized version of the Italian surname "''Colombo''". It most commonly refers to:

* Christopher Columbus (1451-1506), the Italian explorer

* Columbus, Ohio, capital of the U.S. state of Ohio

Columbus may also refer to:

Places ...

's landing in the New World, Pope Alexander was asked by the Spanish monarchy to confirm their ownership of these newly found lands. The bulls issued by Pope Alexander VI: ''Eximiae devotionis

''Eximiae devotionis'' declared on 3 May 1493 is one of three papal bulls of Pope Alexander VI delivered purporting to grant any and all overseas territories in the west and ocean to kings of Castile and León that were found by the kings of Casti ...

'' (3 May 1493), ''Inter caetera

''Inter caetera'' ('Among other orks) was a papal bull issued by Pope Alexander VI on the 4 May () 1493, which granted to the Catholic Monarchs King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile all lands to the "west and south" of ...

'' (4 May 1493) and ''Dudum siquidem

''Dudum siquidem'' (Latin for "A short while ago") is a papal bull issued by Pope Alexander VI Borgia on , one of the Bulls of Donation addressed to the Catholic Monarchs Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon which supplemented ...

'' (23 September 1493), granted rights to Spain with respect to the newly discovered lands in the Americas similar to those Pope Nicholas V

Pope Nicholas V ( la, Nicholaus V; it, Niccolò V; 13 November 1397 – 24 March 1455), born Tommaso Parentucelli, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 6 March 1447 until his death in March 1455. Pope Eugene made ...

had previously conferred on Portugal with the bulls ''Romanus Pontifex

(from Latin: "The Roman Pontiff") are papal bulls issued in 1436 by Pope Eugenius IV and in 1455 by Pope Nicholas V praising catholic King Afonso V of Portugal for his battles against the Muslims, endorsing his military expeditions into Weste ...

'' and '' Dum Diversas''. Morales Padron (1979) concludes that these bulls gave power to enslave the natives. Minnich (2010) asserts that this "slave trade" was permitted to facilitate conversions to Christianity. Other historians and Vatican scholars strongly disagree with these accusations and assert that Alexander never gave his approval to the practice of slavery. Other later popes, such as Pope Paul III

Pope Paul III ( la, Paulus III; it, Paolo III; 29 February 1468 – 10 November 1549), born Alessandro Farnese, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 13 October 1534 to his death in November 1549.

He came to ...

in ''Sublimis Deus

''Sublimis Deus'' (English: ''The sublime God''; erroneously cited as ''Sublimus Dei'' and occasionally as ''Sic Dilexit'') is a bull promulgated by Pope Paul III on June 2, 1537, which forbids the enslavement of the indigenous peoples of the Am ...

'' (1537), Pope Benedict XIV

Pope Benedict XIV ( la, Benedictus XIV; it, Benedetto XIV; 31 March 1675 – 3 May 1758), born Prospero Lorenzo Lambertini, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 17 August 1740 to his death in May 1758. Pope Be ...

in ''Immensa Pastorium'' (1741), and Pope Gregory XVI

Pope Gregory XVI ( la, Gregorius XVI; it, Gregorio XVI; born Bartolomeo Alberto Cappellari; 18 September 1765 – 1 June 1846) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 2 February 1831 to his death in 1 June 1846. He ...

in his letter '' In supremo apostolatus'' (1839), continued to condemn slavery.

Thornberry (2002) asserts that ''Inter caetera'' was applied in the Spanish Requirement of 1513

The Spanish Requirement of 1513 (''Requerimiento'') was a declaration by the Spanish monarchy, written by the Council of Castile jurist Juan López de Palacios Rubios, of Castile's divinely ordained right to take possession of the territories o ...

, which was read to American Indians (who could not understand the colonisers' language) before hostilities against them began. They were given the option to accept the authority of the pope and Spanish crown or face being attacked and subjugated. In 1993, the Indigenous Law Institute called on Pope John Paul II to revoke ''Inter caetera'' and to make reparation for "this unreasonable historical grief". This was followed by a similar appeal in 1994 by the Parliament of World Religions

There have been several meetings referred to as a Parliament of the World's Religions, the first being the World's Parliament of Religions of 1893, which was an attempt to create a global dialogue of faiths. The event was celebrated by another c ...

.

Last years

A danger now arose in the shape of a conspiracy by the deposed despots, the Orsini, and of some of Cesare's own ''condottieri

''Condottieri'' (; singular ''condottiero'' or ''condottiere'') were Italian captains in command of mercenary companies during the Middle Ages and of multinational armies during the early modern period. They notably served popes and other Europ ...