Robert Rogers (soldier) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

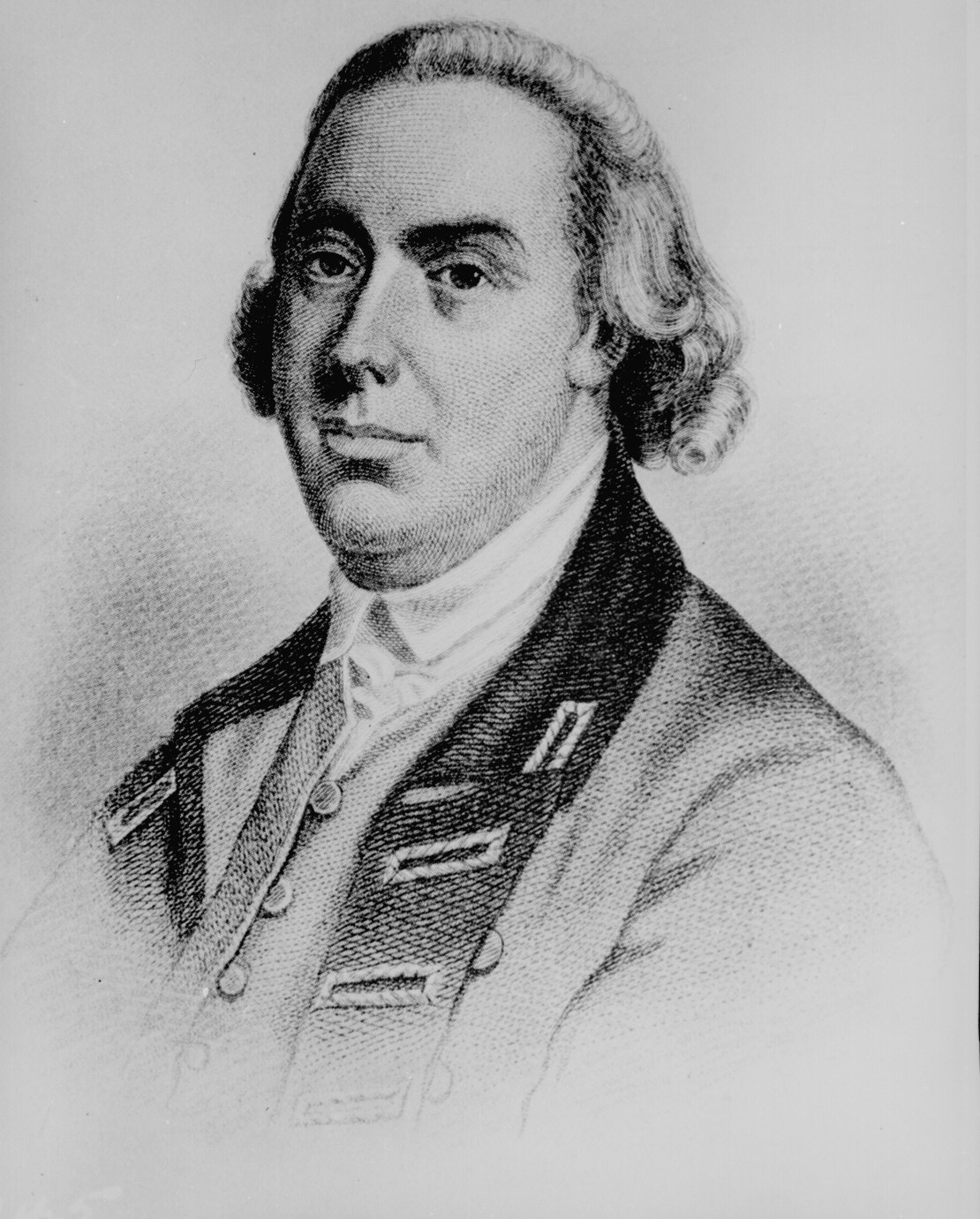

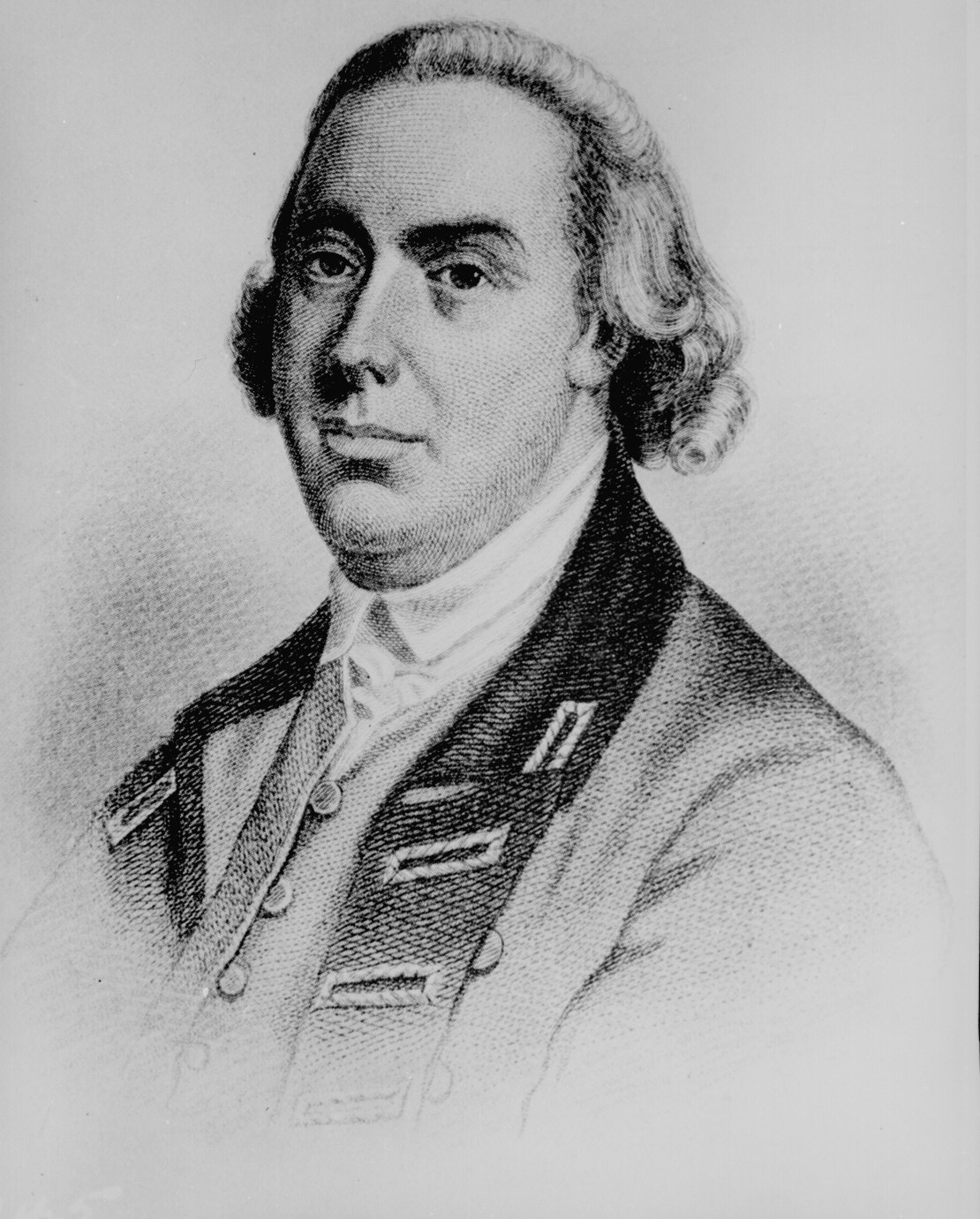

Robert Rogers (7 November 1731 – 18 May 1795) was an

In 1755, war engulfed the colonies, spreading also to Europe. Britain and France declared war on each other. The British in America suffered a string of defeats including Braddock's at the Battle of the Monongahela trying to capture

In 1755, war engulfed the colonies, spreading also to Europe. Britain and France declared war on each other. The British in America suffered a string of defeats including Braddock's at the Battle of the Monongahela trying to capture

In 1756, Rogers arrived in

In 1756, Rogers arrived in

In 1758, Abercromby recognized Rogers' accomplishments by promoting him to

In 1758, Abercromby recognized Rogers' accomplishments by promoting him to

File:Ticonderoga1.jpg,

(

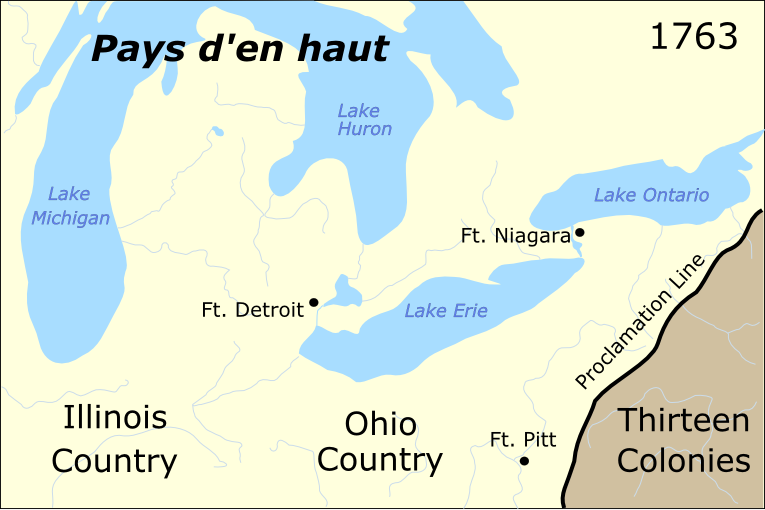

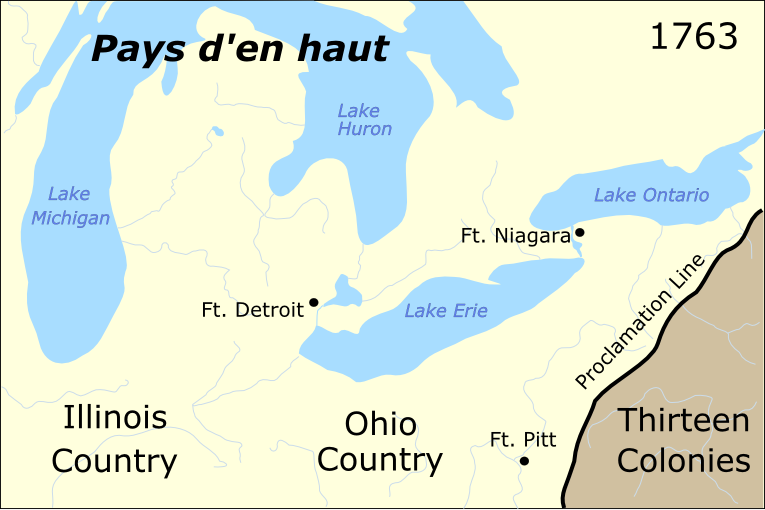

On 7 May 1763,

On 7 May 1763,

As an aristocrat and political intriguer, Gage viewed Rogers as a provincial upstart who posed a threat to his newly acquired power, due to his friendship with Amherst. At the time, Rogers was still a half-pay captain in the British army and, to some degree, under Gage's military jurisdiction. However, Gage could not challenge Rogers, the king's appointee, unless he could find a good reason, as the king would countermand any legal process in order to save his favorites. Knowing this, Gage actively set about finding a solid justification to remove Rogers as royal governor in a way that would forestall royal intervention.

Unaware of Gage's plotting, Rogers continued performing his administrative duties with considerable zest. He dispatched expeditions to search for the fabled

As an aristocrat and political intriguer, Gage viewed Rogers as a provincial upstart who posed a threat to his newly acquired power, due to his friendship with Amherst. At the time, Rogers was still a half-pay captain in the British army and, to some degree, under Gage's military jurisdiction. However, Gage could not challenge Rogers, the king's appointee, unless he could find a good reason, as the king would countermand any legal process in order to save his favorites. Knowing this, Gage actively set about finding a solid justification to remove Rogers as royal governor in a way that would forestall royal intervention.

Unaware of Gage's plotting, Rogers continued performing his administrative duties with considerable zest. He dispatched expeditions to search for the fabled

Gage sent Rogers to Montreal to stand trial but, once there, Rogers was among friends of Amherst. Due to Amherst's influence, Rogers was acquitted of all charges and the verdict was sent to King George III for approval. The king approved, but could not call Gage a liar openly. Instead, he made a note that there was reason to think Rogers might have been treasonous.

Returning to Michigan under the power of Gage was unthinkable; hence, Rogers went to England in 1769 to petition again for debt relief. However, the king had decided that he could do nothing more to help Rogers, and had become preoccupied by the issue of the disaffected colonies. Rogers went again to debtors' prison and tried suing Gage for false imprisonment. Gage settled out of court by offering Rogers the half-pay of a major in return for dropping the suit.

Gage sent Rogers to Montreal to stand trial but, once there, Rogers was among friends of Amherst. Due to Amherst's influence, Rogers was acquitted of all charges and the verdict was sent to King George III for approval. The king approved, but could not call Gage a liar openly. Instead, he made a note that there was reason to think Rogers might have been treasonous.

Returning to Michigan under the power of Gage was unthinkable; hence, Rogers went to England in 1769 to petition again for debt relief. However, the king had decided that he could do nothing more to help Rogers, and had become preoccupied by the issue of the disaffected colonies. Rogers went again to debtors' prison and tried suing Gage for false imprisonment. Gage settled out of court by offering Rogers the half-pay of a major in return for dropping the suit.

Author Interview

at the

American colonial

American colonial architecture includes several building design styles associated with the colonial period of the United States, including First Period English (late-medieval), French Colonial, Spanish Colonial, Dutch Colonial, and Georgian. ...

frontiersman. Rogers served in the British army during both the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the st ...

and the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

. During the French and Indian War, Rogers raised and commanded the famous Rogers' Rangers

Rogers' Rangers was a company of soldiers from the Province of New Hampshire raised by Major Robert Rogers and attached to the British Army during the Seven Years' War ( French and Indian War). The unit was quickly adopted into the British arm ...

, trained for raiding and close combat behind enemy lines.

Early life

Robert Rogers was born to Ulster-Scots settlers, James and Mary McFatridge Rogers on 7 November 1731 in Methuen, a small town in northeasternMassachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

. At that time, the town served as a staging point for Scots-Irish settlers bound for the wilderness of New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

.

In 1739 when Rogers was eight years old, his family relocated to the Great Meadow district of New Hampshire near present-day Concord

Concord may refer to:

Meaning "agreement"

* Pact or treaty, frequently between nations (indicating a condition of harmony)

* Harmony, in music

* Agreement (linguistics), a change in the form of a word depending on grammatical features of other ...

, where James founded a settlement on of land which he called Munterloney, after a hilly place in County Londonderry

County Londonderry ( Ulster-Scots: ''Coontie Lunnonderrie''), also known as County Derry ( ga, Contae Dhoire), is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland, one of the thirty two counties of Ireland and one of the nine counties of Ulster. ...

, Ireland. Rogers referred to this childhood residence as "Mountalona". It was later renamed Dunbarton, New Hampshire.

In 1740, the War of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession () was a European conflict that took place between 1740 and 1748. Fought primarily in Central Europe, the Austrian Netherlands, Italy, the Atlantic and Mediterranean, related conflicts included King George ...

(1740–1748) broke out in Europe and, in 1744, the war spread to North America, where it was known as King George's War

King George's War (1744–1748) is the name given to the military operations in North America that formed part of the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748). It was the third of the four French and Indian Wars. It took place primarily in t ...

(1744–1748). During Rogers' youth (1746), he saw service in the New Hampshire militia as a private in Captain Daniel Ladd's Scouting Company and, in 1747, also as a private in Ebenezer Eastman's Scouting Company, both times guarding the New Hampshire frontier.

In 1754, Rogers became involved with a gang of counterfeiters. He was indicted but the case was never brought to trial.

French and Indian War

In 1755, war engulfed the colonies, spreading also to Europe. Britain and France declared war on each other. The British in America suffered a string of defeats including Braddock's at the Battle of the Monongahela trying to capture

In 1755, war engulfed the colonies, spreading also to Europe. Britain and France declared war on each other. The British in America suffered a string of defeats including Braddock's at the Battle of the Monongahela trying to capture Fort Duquesne

Fort Duquesne (, ; originally called ''Fort Du Quesne'') was a fort established by the French in 1754, at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers. It was later taken over by the British, and later the Americans, and developed a ...

. Encouraged by the French victories, American Indians launched a series of attacks along the colonial frontier. During the French and Indian War, Israel Putnam (who would go on to later fame in the Revolutionary War) fought as a Connecticut militia captain in conjunction with Rogers, and at one point saved his life.

Ranger recruiter

In 1756, Rogers arrived in

In 1756, Rogers arrived in Portsmouth, New Hampshire

Portsmouth is a city in Rockingham County, New Hampshire, United States. At the 2020 census it had a population of 21,956. A historic seaport and popular summer tourist destination on the Piscataqua River bordering the state of Maine, Portsm ...

, and began to muster soldiers for the British Crown, using the authority vested in him by Colonel Winslow. Rogers' recruitment drive was well supported by the frightened and angry provincials due to attacks by American Indians along the frontier. In Portsmouth, he also met his future wife Elizabeth Browne, the youngest daughter of Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of t ...

Reverend Arthur Browne.

Robert's brothers James, Richard, and possibly John all served in Rogers' Rangers. Richard died of small pox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) ce ...

in 1757 at Fort William Henry. His corpse was later disinterred and mutilated by hostile Indians.

Rogers and the Rangers

Rogers raised and commanded the famousRogers' Rangers

Rogers' Rangers was a company of soldiers from the Province of New Hampshire raised by Major Robert Rogers and attached to the British Army during the Seven Years' War ( French and Indian War). The unit was quickly adopted into the British arm ...

that fought for the British during the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the st ...

. This militia unit operated primarily in the Lake George and Lake Champlain

, native_name_lang =

, image = Champlainmap.svg

, caption = Lake Champlain-River Richelieu watershed

, image_bathymetry =

, caption_bathymetry =

, location = New York/ Vermont in the United States; and Quebec in Canada

, coords =

, type ...

regions of New York. They frequently undertook winter raids against French towns and military emplacements, traveling on sleds, crude snowshoes, and even ice skates across frozen rivers. Rogers' Rangers were never fully respected by the British regulars, yet they were one of the few non-Indian forces able to operate in the inhospitable region despite harsh winter conditions and mountainous terrain.

Rogers showed an unusual talent for commanding his unit in conditions to which the regular armies of the day were unaccustomed. He took the initiative in mustering, equipping, and commanding ranger units. He wrote an early guide for commanding such units as Robert Rogers' 28 "Rules of Ranging"

The 28 "Rules of Ranging" are a series of rules and guidelines created by Major Robert Rogers in 1757, during the French and Indian War (1754–63).

The rules were originally written at Rogers Island in the Hudson River near Fort Edward. They ...

. The Queen's York Rangers

la, celer et audax, lit=swift and bold

, colors = Green and amethyst blue

, identification_symbol =

, identification_symbol_label =

, march = "Braganza"

, notable_commanders ...

of the Canadian Army, the U.S. Army Rangers

United States Army Rangers, according to the US Army's definition, are personnel, past or present, in any unit that has the official designation "Ranger". The term is commonly used to include graduates of the US Army Ranger School, even if t ...

, and the 1st Battalion 119th Field Artillery all claim Rogers as their founder, and " Rogers' Standing Orders" are still quoted on the first page of the U.S. Army's Ranger handbook.

Rogers was personally responsible for paying his soldiers, and he went deeply into debt and took loans to ensure that they were paid properly after their regular pay was raided during transport. He was never compensated by the British Army or government, though he had reason to believe that he should have his expenses reimbursed.

Northern campaign

From 1755 to 1758, Rogers and his rangers served under a series of unsuccessful British commanders operating over the northern accesses to the British colonies: Major General William Johnson, Major General William Shirley, ColonelWilliam Haviland

William Haviland (1718 – 16 September 1784) was an Irish-born general in the British Army. He is best known for his service in North America during the Seven Years' War.

Life

William Haviland was born in Ireland in 1718. He entered milita ...

, and Major General James Abercromby. At the time, the British could do little more than fight defensive campaigns around Lake Champlain

, native_name_lang =

, image = Champlainmap.svg

, caption = Lake Champlain-River Richelieu watershed

, image_bathymetry =

, caption_bathymetry =

, location = New York/ Vermont in the United States; and Quebec in Canada

, coords =

, type ...

, Crown Point, Ticonderoga, and the upper Hudson.

During this time, the rangers proved indispensable; they grew gradually to twelve companies, as well as several additional contingents of Indians who had pledged their allegiance to the British cause. The rangers were kept organizationally distinct from British regulars. Rogers was their acting commandant, as well as the direct commander of his own company.

On 21 January 1757 at the First Battle of the Snowshoes, Rogers' Rangers ambushed and captured seven Canadians

Canadians (french: Canadiens) are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of ...

near Fort Carillon

Fort Carillon, presently known as Fort Ticonderoga, was constructed by Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil, Governor of French Canada, to protect Lake Champlain from a British invasion. Situated on the lake some south of Fort Saint Frédéric, it ...

but then encountered a hundred French and Canadian militia and Ottawa Indians from the Ohio Country. Roger's forces retreated after taking casualties of 14 killed, nine wounded, and six missing or captured; the French-Indian forces were 11 killed, 27 wounded.

British forces surrendered Fort William Henry in August 1757, after which the Rangers were stationed on Rogers Island near Fort Edward. This allowed them to train and operate with more freedom than the regular British forces.

On 13 March 1758 at the Second Battle of the Snowshoes, Rogers' Rangers ambushed a French and Indian column and, in turn, were ambushed by enemy forces. The Rangers lost 125 men in this encounter, as well as eight men wounded, with 52 surviving. Rogers estimated 100 killed and nearly 100 wounded of the French-Indian forces; however, the French listed casualties as a total of ten Indians killed and seventeen wounded.

On 7 July 1758, Rogers' Rangers took part in the Battle of Carillon

The Battle of Carillon, also known as the 1758 Battle of Ticonderoga, Chartrand (2000), p. 57 was fought on July 8, 1758, during the French and Indian War (which was part of the global Seven Years' War). It was fought near Fort Carillon (now ...

.

In 1758, Abercromby recognized Rogers' accomplishments by promoting him to

In 1758, Abercromby recognized Rogers' accomplishments by promoting him to Major

Major ( commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicato ...

, with the equally famous John Stark as his second in command. Rogers now held two ranks appropriate to his double role: Captain and Major.

In 1759, the tide of the war turned and the British advanced on the city of Quebec. Major General Jeffrey Amherst, the newly appointed Commander-in-Chief of British forces in North America, had a brilliant and definitive idea. He dispatched Rogers and his rangers on an expedition far behind enemy lines to the west against the Abenaki

The Abenaki ( Abenaki: ''Wαpánahki'') are an Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands of Canada and the United States. They are an Algonquian-speaking people and part of the Wabanaki Confederacy. The Eastern Abenaki language was pre ...

s at Saint-Francis in Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirte ...

, a staging base for Indian raids into New England. Rogers led a force of two hundred rangers from Crown Point, New York, deep into French territory to Saint-Francis.

At this time, the Indians near Saint-Francis had given up their aboriginal way of life and were living in a town next to a French mission. Rogers burned the town and claimed to have killed 200; the actual number was 30 killed and 5 captured. Rogers losses were 41 killed; 7 wounded 10 captured. Following the 3 October 1759 attack and successful destruction of Saint-Francis, Rogers' force ran out of food during their retreat back through the rugged wilderness of northern Vermont

Vermont () is a U.S. state, state in the northeast New England region of the United States. Vermont is bordered by the states of Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, and New York (state), New York to the west, and the Provin ...

. The Rangers reached a safe location along the Connecticut River

The Connecticut River is the longest river in the New England region of the United States, flowing roughly southward for through four states. It rises 300 yards (270 m) south of the U.S. border with Quebec, Canada, and discharges at Long Islan ...

at the abandoned Fort Wentworth

Fort Wentworth was built by order of Benning Wentworth in 1755. The fort was built at the junction of the Upper Ammonoosuc River and Connecticut River, in Northumberland, New Hampshire, by soldiers of Colonel Joseph Blanchard's New Hampshire Prov ...

. Rogers left them encamped, and returned a few days later with food and relief forces from Fort at Number 4, now Charlestown, New Hampshire

Charlestown is a town in Sullivan County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 4,806 at the 2020 census, down from 5,114 at the 2010 census. The town is home to Hubbard State Forest and the headquarters of the Student Conservation A ...

, the nearest British town.

The destruction of Saint-Francis by Rogers was a major psychological victory, as the colonists no longer felt that they were helpless. The residents of Saint-Francis, a combined group of Abenakis and others, understood that they were no longer beyond reach. Abenaki raids along the frontier did not cease, but significantly diminished.

Fort Ticonderoga

Fort Ticonderoga (), formerly Fort Carillon, is a large 18th-century star fort built by the French at a narrows near the south end of Lake Champlain, in northern New York, in the United States. It was constructed by Canadian-born French milit ...

(

Fort Carillon

Fort Carillon, presently known as Fort Ticonderoga, was constructed by Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil, Governor of French Canada, to protect Lake Champlain from a British invasion. Situated on the lake some south of Fort Saint Frédéric, it ...

)

File:Dscn3099_connecticut_river_french_king_bridge.jpg, Connecticut River

The Connecticut River is the longest river in the New England region of the United States, flowing roughly southward for through four states. It rises 300 yards (270 m) south of the U.S. border with Quebec, Canada, and discharges at Long Islan ...

in Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

File:Plaine_abraham_quebec.jpg, Plains of Abraham in Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirte ...

Montreal Campaign

Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirte ...

fell in 1759 and in the Spring of 1760 Rogers joined in Amherst's campaign on Montreal but before doing so conducted a successful preemptive raid on Fort Sainte Thérèse

Fort Sainte Thérèse is the name given to three different forts built successively on one site, among a series of fortifications constructed during the 17th century by France along the Richelieu River, in the province of Quebec, in Montérégie.

...

in June which was used to supply the French army as well as being a vital link in the communication and supply line between Fort Saint-Jean and the French forces at Île aux Noix.

Roger's was then part of William Haviland

William Haviland (1718 – 16 September 1784) was an Irish-born general in the British Army. He is best known for his service in North America during the Seven Years' War.

Life

William Haviland was born in Ireland in 1718. He entered milita ...

's thrust (one of three all led by Amherst) on Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple- ...

in August where it marched from Lake Ontario

Lake Ontario is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is bounded on the north, west, and southwest by the Canadian province of Ontario, and on the south and east by the U.S. state of New York. The Canada–United States border sp ...

in the west along the Saint Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (french: Fleuve Saint-Laurent, ) is a large river in the middle latitudes of North America. Its headwaters begin flowing from Lake Ontario in a (roughly) northeasterly direction, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, connecting ...

and from upper New York via the Richelieu River

The Richelieu River () is a river of Quebec, Canada, and a major right-bank tributary of the St. Lawrence River. It rises at Lake Champlain, from which it flows northward through Quebec and empties into the St. Lawrence. It was formerly kn ...

. Along the way Rogers fought to reduce Île aux Noix which succeeded in a ruse attack. Soon after Fort Saint Jean was burned by the French; and Chambly was seized. The Rangers then led the final advance on Montreal which surrendered without a fight the following month.

Western campaign

Rogers then advanced when Indian activity ceased against colonials in the east, and Rogers' service there was over. General Amherst transferred him to Brigadier General Robert Monckton, commanding at Fort Pitt (formerlyFort Duquesne

Fort Duquesne (, ; originally called ''Fort Du Quesne'') was a fort established by the French in 1754, at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers. It was later taken over by the British, and later the Americans, and developed a ...

). Following Amherst's advice, Monckton sent the rangers to capture Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at t ...

, far to the north, which they did.

On 29 November 1760 in Detroit, Rogers received the submission of the French posts on the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lakes ...

; during the spring 1761, Rogers and his Rangers occupied Fort Michilimackinac and Fort St. Joseph. It was the final act of his command. Shortly thereafter, his rangers were disbanded. Monckton offered Rogers command of a company of regulars in South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

but, after visiting the place, Rogers chose instead to command another company in New York. That unit was soon disbanded, however, and Rogers was forced into retirement at half-pay.

No longer preoccupied with military affairs, Rogers returned to New England to marry Elizabeth Browne in June, 1761, and set up housekeeping with her in Concord, New Hampshire

Concord () is the capital city of the U.S. state of New Hampshire and the county seat, seat of Merrimack County, New Hampshire, Merrimack County. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census the population was 43,976, making it the third larg ...

. Like many New Englanders, they had indentured servants

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repayment, ...

and slaves, including an Indian boy captured at Saint-Francis.

Some historians claim that the state of Rogers' finances at this time is not compatible with what he and others professed it to be later. Rogers received large grants of land in southern New Hampshire in compensation for his services. He sold much of it at a profit and was able to purchase and maintain slaves. He deeded much of his land to his wife's family, which served to support her later.

In 1761, Rogers purchased a commission commanding a British Independent Company serving in South Carolina during the Anglo-Cherokee War. While Rogers never commanded his men in the field, his company participated in the 1761 Grant Campaign which destroyed the homes and food of more than 5000 Cherokee men, women, and children.

On 10 February 1763, the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the st ...

came to an end with the Treaty of Paris (also known as the ''Treaty of 1763''). Rogers found himself once more a soldier of fortune, still on half-pay. Later, General Thomas Gage

General Thomas Gage (10 March 1718/192 April 1787) was a British Army general officer and colonial official best known for his many years of service in North America, including his role as British commander-in-chief in the early days of t ...

remarked that, if the army had put him on whole pay, they could have prevented his later unfit employment (Gage's terms).

Pontiac's War

On 7 May 1763,

On 7 May 1763, Pontiac's War

Pontiac's War (also known as Pontiac's Conspiracy or Pontiac's Rebellion) was launched in 1763 by a loose confederation of Native Americans dissatisfied with British rule in the Great Lakes region following the French and Indian War (1754–17 ...

broke out in the Ohio Country. Odawa

The Odawa (also Ottawa or Odaawaa ), said to mean "traders", are an Indigenous American ethnic group who primarily inhabit land in the Eastern Woodlands region, commonly known as the northeastern United States and southeastern Canada. They h ...

leader Pontiac Pontiac may refer to:

*Pontiac (automobile), a car brand

*Pontiac (Ottawa leader) ( – 1769), a Native American war chief

Places and jurisdictions Canada

*Pontiac, Quebec, a municipality

** Apostolic Vicariate of Pontiac, now the Roman Catholic D ...

attempted to capture Fort Detroit

Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit or Fort Detroit (1701–1796) was a fort established on the north bank of the Detroit River by the French officer Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac and the Italian Alphonse de Tonty in 1701. In the 18th century, Fre ...

by surprise with a force of 300 warriors. However, the British commander was aware of Pontiac's plan, and his garrison was armed and ready. Undaunted, Pontiac withdrew and laid siege to the fort. Eventually, more than 900 Indian warriors from a half-dozen tribes joined the siege of Fort Detroit.

Upon hearing this news, Rogers offered his services to General Jeffrey Amherst. Rogers then accompanied Captain James Dalyell with a relief force to Fort Detroit

Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit or Fort Detroit (1701–1796) was a fort established on the north bank of the Detroit River by the French officer Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac and the Italian Alphonse de Tonty in 1701. In the 18th century, Fre ...

. Their ill-fated mission was terminated at the Battle of Bloody Run

The Battle of Bloody Run was fought during Pontiac's War on July 31, 1763, on what now is the site of Elmwood Cemetery in the Eastside Historic Cemetery District of Detroit, Michigan. In an attempt to break Pontiac's siege of Fort Detroit ...

on 31 July 1763.

In an attempt to break Pontiac's siege

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict characteriz ...

, about 250 British troops led by Dalyell and Rogers attempted a surprise attack on his encampment. However, Pontiac was ready, supposedly alerted by French settlers, and he defeated the British at Parent's Creek two miles north of the fort. The creek or ''run'' was said to have run red with the blood of the 20 dead and 34 wounded British soldiers and was henceforth known as Bloody Run. Captain James Dalyell was one of those killed.

Soon after these events, Pontiac's war effort collapsed and Pontiac himself faded away into obscurity and death. Surprisingly, Rogers later memorialized Pontiac and his conflict in a stage play during his sojourn in England.

Post-war success and failure

Rogers had brought total dedication to his position as commander of the rangers. As was often the custom in the British and American armies, he had spent his own money to equip the rangers when needed and consequently had gone into debt. In 1764, he was faced with the problem of repaying his creditors. To recoup his finances, Robert engaged briefly in a business venture with the fur trader,John Askin

John Askin (1739–1815) was an Irish fur trader, merchant, and colonial official. He was instrumental in the establishment of British rule in Upper Canada.

Early years

He was born in Aughnacloy, Ireland in 1739; his ancestors are believed to ...

, near Detroit. After it failed, he hoped to win the money by gambling, with the result that he was totally ruined. His creditors put him in prison for debt in New York, but he escaped.

Author in Britain

In 1765, Rogers voyaged to England to obtain pay for his service and capitalize on his fame. His journals and ''A Concise Account of North America'' were published. Immediately thereafter, he wrote the stage play ''Ponteach '' ontiac': or the Savages of America'' (1766), significant as an early American drama and for its sympathetic portrayal of American Indians. He enjoyed some moderate success with his publications (though Ponteach was condemned by the critics) and attracted royal attention. He had an audience with KingGeorge III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

, to whom he proposed undertaking an expedition to find the Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The eastern route along the ...

. The King appointed Rogers governor of Michilimackinac

Michilimackinac ( ) is derived from an Ottawa Ojibwe name for present-day Mackinac Island and the region around the Straits of Mackinac between Lake Huron and Lake Michigan.. Early settlers of North America applied the term to the entire region ...

(Mackinaw City, Michigan

Mackinaw City ( ) is a village in Emmet and Cheboygan counties in the U.S. state of Michigan. The population was 846 at the 2010 census, the population increases during summertime, including an influx of tourists and seasonal workers who serve ...

) with a charter to look for the passage, and he returned to North America.

Royal Governor

Upon his return to America, Rogers moved with his wife to the fur-trading outpost of Fort Michilimackinac and began his duties as royal governor. During Rogers' absence, Amherst had been replaced byThomas Gage

General Thomas Gage (10 March 1718/192 April 1787) was a British Army general officer and colonial official best known for his many years of service in North America, including his role as British commander-in-chief in the early days of t ...

as commander of the British forces in America, and Gage was a bitter rival of Amherst. Rogers was a loyal friend of Amherst and was consequently hated by Gage.

As an aristocrat and political intriguer, Gage viewed Rogers as a provincial upstart who posed a threat to his newly acquired power, due to his friendship with Amherst. At the time, Rogers was still a half-pay captain in the British army and, to some degree, under Gage's military jurisdiction. However, Gage could not challenge Rogers, the king's appointee, unless he could find a good reason, as the king would countermand any legal process in order to save his favorites. Knowing this, Gage actively set about finding a solid justification to remove Rogers as royal governor in a way that would forestall royal intervention.

Unaware of Gage's plotting, Rogers continued performing his administrative duties with considerable zest. He dispatched expeditions to search for the fabled

As an aristocrat and political intriguer, Gage viewed Rogers as a provincial upstart who posed a threat to his newly acquired power, due to his friendship with Amherst. At the time, Rogers was still a half-pay captain in the British army and, to some degree, under Gage's military jurisdiction. However, Gage could not challenge Rogers, the king's appointee, unless he could find a good reason, as the king would countermand any legal process in order to save his favorites. Knowing this, Gage actively set about finding a solid justification to remove Rogers as royal governor in a way that would forestall royal intervention.

Unaware of Gage's plotting, Rogers continued performing his administrative duties with considerable zest. He dispatched expeditions to search for the fabled Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The eastern route along the ...

under Jonathan Carver and James Tute, but they were unsuccessful and the path to the Pacific Ocean remained undiscovered until the expedition led by Alexander MacKenzie in 1793.

Rogers perceived a need for unity and a stronger government, and he negotiated with the Indians, parlayed with the French, and developed a plan for a province in Michigan to be administered by a governor and Privy Council reporting to the king. This plan was supported by George III, but had little chance of being adopted, since Parliament had no intention of increasing the king's power.

Meanwhile, Gage used every opportunity to defame Rogers, portraying him as an opportunist who had gotten rich on the war only to gamble away his money as a profligate. It is difficult to say how many of these allegations were true and how much Gage believed them to be true. Gage apparently saw Rogers as of questionable loyalty—certainly he was not loyal to Gage—and therefore he needed watching. Rogers' dealings with the American Indians troubled Gage, as he and many other British officers in America had come to regard the Indians with great suspicion.

Arrest for treason

Gage hired spies to intercept Rogers' mail and suborned his subordinates. Unfortunately, Rogers offended his private secretary, Nathaniel Potter, who subsequently gave Gage the excuse that he needed. Potter swore in an affidavit that Rogers had said that he would offer his province to the French if the British authorities failed to approve his method of governance. Potter's claims were questionable. The French were not in any position to receive Rogers, particularly with a British governor sitting in Montreal. Nevertheless, on the strength of Potter's affidavit, Rogers was arrested in 1767, charged with treason, and taken to Montreal in chains for trial. However, the trial was postponed until 1768. Elizabeth, carrying their only child, went home toPortsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most d ...

. There she gave birth to a son; he was named Arthur. After reaching adulthood, Arthur decided to become a lawyer based in his home town of Portsmouth. He also chose to start a family, the descendants of whom are still living today.

Vindication

Gage sent Rogers to Montreal to stand trial but, once there, Rogers was among friends of Amherst. Due to Amherst's influence, Rogers was acquitted of all charges and the verdict was sent to King George III for approval. The king approved, but could not call Gage a liar openly. Instead, he made a note that there was reason to think Rogers might have been treasonous.

Returning to Michigan under the power of Gage was unthinkable; hence, Rogers went to England in 1769 to petition again for debt relief. However, the king had decided that he could do nothing more to help Rogers, and had become preoccupied by the issue of the disaffected colonies. Rogers went again to debtors' prison and tried suing Gage for false imprisonment. Gage settled out of court by offering Rogers the half-pay of a major in return for dropping the suit.

Gage sent Rogers to Montreal to stand trial but, once there, Rogers was among friends of Amherst. Due to Amherst's influence, Rogers was acquitted of all charges and the verdict was sent to King George III for approval. The king approved, but could not call Gage a liar openly. Instead, he made a note that there was reason to think Rogers might have been treasonous.

Returning to Michigan under the power of Gage was unthinkable; hence, Rogers went to England in 1769 to petition again for debt relief. However, the king had decided that he could do nothing more to help Rogers, and had become preoccupied by the issue of the disaffected colonies. Rogers went again to debtors' prison and tried suing Gage for false imprisonment. Gage settled out of court by offering Rogers the half-pay of a major in return for dropping the suit.

American Revolutionary War

Because of his legal troubles in England, Robert Rogers missed the major events in the disaffected colonies. He heard that revolution was likely to break out and returned to America in 1775. The Americans were as out of touch with Rogers as he was with them, looking upon him as the noted ranger leader and expecting him to behave as one; they were at a total loss to explain his drunken and licentious behavior. At that time, Rogers was perhaps suffering from the alcoholism that blighted his later life and led to the loss of his family, land, money, and friends. It is unclear exactly what transpired between the revolutionary leaders and Rogers. Rogers was arrested by the local Committee of Safety as a possible spy and released on parole that he would not serve against the colonies. He was offered a commission in the Revolutionary Army by theContinental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislative bodies, with some executive function, for thirteen of Britain's colonies in North America, and the newly declared United States just before, during, and after the American Revolutionary War. ...

, but declined on the grounds that he was a British officer. He later wrote to George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

asking for a command, but instead Washington had him arrested.

He escaped from Washington's custody only to find revolutionary ranks firm against him, so he offered his services to the British Army. They also were hoping that he would live up to his reputation. In August 1776, he formed another ranger-type unit called the Queen's Rangers

The Queen's Rangers, also known as the Queen's American Rangers, and later Simcoe's Rangers, were a Loyalist military unit of the American Revolutionary War. Formed in 1776, they were named for Queen Charlotte, consort of George III. The Queen ...

as its colonel. In September 1776, Rogers assisted in the capture of Nathan Hale

Nathan Hale (June 6, 1755 – September 22, 1776) was an American Patriot, soldier and spy for the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. He volunteered for an intelligence-gathering mission in New York City but was captured ...

, a spy for the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

. A contemporaneous account of Hale's capture is in the Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The libra ...

, written by Consider Tiffany

Consider Tiffany (March 15, 1732 – June 19, 1796) was a British loyalist and storekeeper in Colonial America. He also served as a sergeant during the French and Indian War. He is described in the book ''The Tiffanys of America'' by Nelson Otis ...

, a Connecticut shopkeeper and Loyalist. In Tiffany's account, Rogers did not believe Hale's cover story that he was a teacher, and lured him into his own betrayal by pretending to be a patriot spy himself.

In May 1777, the British Army forcibly retired Rogers on grounds of "poor health". A return home now was impossible; Hale's execution and Rogers raising troops against the colonials seemed to confirm Washington's suspicions. At Washington's prompting, the New Hampshire legislature passed two decrees regarding Rogers: one a proscription, and the other a divorce from his wife on grounds of abandonment and infidelity. She could not afford any friendship or mercy toward Robert now if she expected to remain in New Hampshire. Later, Elizabeth married American naval officer John Roche. She died in 1811.

Later life and death

After a brief sojourn in England, Rogers returned in 1779 to raise theKing's Rangers

The King's Rangers, also known as the King's American Rangers, was a Loyalist provincial ranger unit raised in Nova Scotia for service during the American Revolutionary War.

Formation

After Colonel Robert Rogers left the Queen's Rangers in 177 ...

in Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

for General Sir Henry Clinton. He was unable to keep the position due to his alcoholism, so his place was taken by his brother James. Robert Rogers played no further part in the war.

Rogers was captured by an American privateer and spent some time in a prison in New York, escaping in 1782. In 1783, he was evacuated with other British troops to England. There, he was unable to earn a living or to defeat his alcoholism. He died in obscurity and debt in 1795, what little money he had going to pay an arrears in rent. He was buried in London but his gravesite has been lost.

Legacy

Maj. Rogers is an inaugural inductee into the United States Army Ranger Hall of Fame in 1992, for tactics and success as a Ranger, setting the standard for today's U.S. Army Rangers. Camp Rogers, on the eastern edge ofFort Benning

Fort Benning is a United States Army post near Columbus, Georgia, adjacent to the Alabama– Georgia border. Fort Benning supports more than 120,000 active-duty military, family members, reserve component soldiers, retirees and civilian employee ...

, is the location of the Ranger Assessment Phase of U.S. Army Ranger School

The United States Army Ranger School is a 62-day small unit tactics and leadership course that develops functional skills directly related to units whose mission is to engage the enemy in close combat and direct fire battles.

Ranger training wa ...

, and the headquarters compound for the United States Army Airborne and Ranger Training Brigade.

On 30 May 2005, (Memorial Day

Memorial Day (originally known as Decoration Day) is a federal holiday in the United States for mourning the U.S. military personnel who have fought and died while serving in the United States armed forces. It is observed on the last Monda ...

in the U.S.), a statue of Rogers was unveiled during a ceremony on Rogers Island in the Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between Ne ...

, north of Albany, New York

Albany ( ) is the capital of the U.S. state of New York, also the seat and largest city of Albany County. Albany is on the west bank of the Hudson River, about south of its confluence with the Mohawk River, and about north of New York Cit ...

. This is near to the site where Rogers penned his " Rules of Ranging".

Rogers is mentioned respectfully in "The Ranger Handbook" which is given to every soldier in the U.S. Army's Ranger School, and is referred to in that publication as the originator of ranger tactics in the American military. The Handbook summarizes Rogers' principles of irregular warfare

Irregular warfare (IW) is defined in United States joint doctrine as "a violent struggle among state and non-state actors for legitimacy and influence over the relevant populations." Concepts associated with irregular warfare are older than the te ...

as presented in "Rules of Ranging"."

Methuen High School, in the town in which Rogers was born, uses the "Rangers" as their mascot.

In fiction

Rogers' heroics in the French and Indian War, including the search for theNorthwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The eastern route along the ...

, and his later life are depicted in the novel ''Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The eastern route along the ...

'' (1936) by Kenneth Roberts. The novel inspired the 1940 film ''Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The eastern route along the ...

'', starring Spencer Tracy

Spencer Bonaventure Tracy (April 5, 1900 – June 10, 1967) was an American actor. He was known for his natural performing style and versatility. One of the major stars of Hollywood's Golden Age, Tracy was the first actor to win two cons ...

as Major Rogers. The novel and film inspired the 1958–1959 NBC

The National Broadcasting Company (NBC) is an American English-language commercial broadcast television and radio network. The flagship property of the NBC Entertainment division of NBCUniversal, a division of Comcast, its headquarters are l ...

TV series ''Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The eastern route along the ...

'', starring Keith Larsen as Rogers.

Rogers appears in Diana Gabaldon's historical novel ''An'' ''Echo in'' ''the Bone'', which includes a dramatization of Rogers' capture of Nathan Hale

Nathan Hale (June 6, 1755 – September 22, 1776) was an American Patriot, soldier and spy for the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. He volunteered for an intelligence-gathering mission in New York City but was captured ...

.

Angus Macfadyen.portrays Rogers as a central antihero in the 2014-2017 AMC drama series '' Turn: Washington's Spies.''

See also

*Long-range reconnaissance patrol

A long-range reconnaissance patrol, or LRRP (pronounced "lurp"), is a small, well-armed reconnaissance team that patrols deep in enemy-held territory.Ankony, Robert C., ''Lurps: A Ranger's Diary of Tet, Khe Sanh, A Shau, and Quang Tri,'' revised ...

* United States Army Rangers

United States Army Rangers, according to the US Army's definition, are personnel, past or present, in any unit that has the official designation "Ranger". The term is commonly used to include graduates of the US Army Ranger School, even if t ...

References

Further reading

* Beattie, Daniel J. (1986). “The Adaptation of the British Army to Wilderness Warfare, 1755-1763”, Adapting to Conditions: War and Society in the Eighteenth Century, ed. Maarten Ultee (University of Alabama Press), 56–83. * Chet, Guy. “The Literary and Military Career of Benjamin Church: Change or Continuity in Early American Warfare,” Historical Journal of Massachusetts 35:2 (Summer 2007): 105-112 * Chet, Guy (2003). Conquering the American Wilderness: The Triumph of European Warfare in the Colonial Northeast. University of Massachusetts Press. * * * Pargellis, Stanley McCrory. “Braddock’s Defeat”, American Historical Review 41 (1936): 253–269. * Pargellis, Stanley McCrory (1933). Lord Loudoun in North America. Yale University Press. * Potter, Tiffany, ed. Robert Rogers' ''Ponteach, or the Savages of America: A Tragedy''. University of Toronto Press, 2010. * pluAuthor Interview

at the

Pritzker Military Museum & Library

The Pritzker Military Museum & Library (formerly Pritzker Military Library) is a non-profit museum and a research library for the study of military history on Michigan Avenue in Chicago, Illinois. The institution was founded in 2003, and its sp ...

on 27 March 2010

*

*

External links

* * * Contains descendants of Robert Rogers, James Rogers, Samuel Rogers and his other siblings. * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Rogers, Robert 1731 births 1795 deaths American people of Scotch-Irish descent British America army officers British people of Pontiac's War Loyalists in the American Revolution from New Hampshire People acquitted of treason People from Dunbarton, New Hampshire People from Methuen, Massachusetts People of colonial Massachusetts People of colonial New Hampshire People of Massachusetts in the French and Indian War Military personnel from Massachusetts