Ring of Pietroassa on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Ring of Pietroassa or Buzău torc is a gold

The Ring of Pietroassa or Buzău torc is a gold

The original hoard, discovered within a large ring barrow known as Istriţa Hill near Pietroasele, Romania, consisted of 22 pieces, comprising a wide assortment of gold vessels, plates and cups as well as jewellery, including two rings with inscriptions. When first uncovered, the objects were found stuck together by an unidentifiable black mass, leading to the assumption that the hoard might have been covered in some kind of organic material (e.g. cloth or leather) prior to being interred. The total weight of the find was approximately 20 kg (44 lb.).

Ten objects, among them one of the inscribed rings, were stolen shortly after the find was made, and when the remaining objects were recovered, it was discovered that the other ring had been cut into at least four pieces by a Bucharest goldsmith, whereby one of the inscribed characters had become damaged to the point of illegibility. Fortunately, detailed drawings, a cast, and a photograph made by London's Arundel Society of the ring before it was damaged survive, and the nature of the lost character can be established with relative certainty.

The remaining objects in the collection display a high quality of craftsmanship such that scholars doubt an indigenous origin.

The original hoard, discovered within a large ring barrow known as Istriţa Hill near Pietroasele, Romania, consisted of 22 pieces, comprising a wide assortment of gold vessels, plates and cups as well as jewellery, including two rings with inscriptions. When first uncovered, the objects were found stuck together by an unidentifiable black mass, leading to the assumption that the hoard might have been covered in some kind of organic material (e.g. cloth or leather) prior to being interred. The total weight of the find was approximately 20 kg (44 lb.).

Ten objects, among them one of the inscribed rings, were stolen shortly after the find was made, and when the remaining objects were recovered, it was discovered that the other ring had been cut into at least four pieces by a Bucharest goldsmith, whereby one of the inscribed characters had become damaged to the point of illegibility. Fortunately, detailed drawings, a cast, and a photograph made by London's Arundel Society of the ring before it was damaged survive, and the nature of the lost character can be established with relative certainty.

The remaining objects in the collection display a high quality of craftsmanship such that scholars doubt an indigenous origin.

PDF

*

PDFSummary

* * * . * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * . * * . * . * * * *

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ring Of Pietroassa Germanic paganism Goths Germanic archaeological artifacts Elder Futhark inscriptions Individual necklaces Torcs Gold objects Archaeological discoveries in Romania Buzău County

The Ring of Pietroassa or Buzău torc is a gold

The Ring of Pietroassa or Buzău torc is a gold torc

A torc, also spelled torq or torque, is a large rigid or stiff neck ring in metal, made either as a single piece or from strands twisted together. The great majority are open at the front, although some had hook and ring closures and a few had ...

-like necklace found in a ring barrow in Pietroassa (now Pietroasele), Buzău County

Buzău County () is a county (județ) of Romania, in the historical region Muntenia, with the capital city at Buzău.

Demographics

In 2011, it had a population of 432,054 and the population density was 70.7/km2.

* Romanians – 97%

* Roma ...

, southern Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, and ...

(formerly Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia (; ro, Țara Românească, lit=The Romanian Land' or 'The Romanian Country, ; archaic: ', Romanian Cyrillic alphabet: ) is a historical and geographical region of Romania. It is situated north of the Lower Danube and s ...

), in 1837. It formed part of a large gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile me ...

hoard (the Pietroasele treasure) dated to between 250 and 400 AD. The ring itself is generally assumed to be of Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

-Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western Europe, Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa ...

origin, and features a Gothic language

Gothic is an extinct East Germanic language that was spoken by the Goths. It is known primarily from the ''Codex Argenteus'', a 6th-century copy of a 4th-century Bible translation, and is the only East Germanic language with a sizeable text c ...

inscription in the Elder Futhark runic alphabet

Runes are the letters in a set of related alphabets known as runic alphabets native to the Germanic peoples. Runes were used to write various Germanic languages (with some exceptions) before they adopted the Latin alphabet, and for specialised ...

.

The inscribed ring remains the subject of considerable academic interest, and a number of theories regarding its origin, the reason for its burial and its date have been proposed. The inscription, which sustained irreparable damage shortly after its discovery, can no longer be read with certainty, and has been subjected to various attempts at reconstruction and interpretation. Recently, however, it has become possible to reconstruct the damaged portion with the aid of rediscovered depictions of the ring in its original state. Taken as a whole, the inscribed ring may offer insight into the nature of the pre-Christian pagan religion of the Goths.

History

Origin

Taylor

Taylor, Taylors or Taylor's may refer to:

People

* Taylor (surname)

** List of people with surname Taylor

* Taylor (given name), including Tayla and Taylah

* Taylor sept, a branch of Scottish clan Cameron

* Justice Taylor (disambiguation)

Pl ...

(1879), in one of the earliest works discussing the find, speculates that the objects could represent a part of the plunder acquired by Goths in the raids made on the Roman provinces of Moesia and Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to ...

(238 - 251). Another early theory, probably first proposed by Odobescu (1889) and picked up again by Giurascu (1976), identifies Athanaric

Athanaric or Atanaric ( la, Athanaricus; died 381) was king of several branches of the Thervingian Goths () for at least two decades in the 4th century. Throughout his reign, Athanaric was faced with invasions by the Roman Empire, the Huns and a c ...

, pagan king of the Gothic Thervingi

The Thervingi, Tervingi, or Teruingi (sometimes pluralised Tervings or Thervings) were a Gothic people of the plains north of the Lower Danube and west of the Dniester River in the 3rd and the 4th centuries.

They had close contacts with the G ...

, as the likely owner of the hoard, presumably acquired through the conflict with the Roman Emperor Valens

Valens ( grc-gre, Ουάλης, Ouálēs; 328 – 9 August 378) was Roman emperor from 364 to 378. Following a largely unremarkable military career, he was named co-emperor by his elder brother Valentinian I, who gave him the eastern half of ...

in 369. The ''Goldhelm'' catalogue (1994) suggests that the objects could also be viewed as having been gifts made by Roman leaders to allied Germanic princes.

Recent mineralogical

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifacts. Specific studies within mineralogy include the p ...

studies performed on the objects indicate at least three geographically disparate origins for the gold ore itself: the Southern Ural Mountains

The Ural Mountains ( ; rus, Ура́льские го́ры, r=Uralskiye gory, p=ʊˈralʲskʲɪjə ˈɡorɨ; ba, Урал тауҙары) or simply the Urals, are a mountain range that runs approximately from north to south through western ...

, Nubia

Nubia () (Nobiin: Nobīn, ) is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the first cataract of the Nile (just south of Aswan in southern Egypt) and the confluence of the Blue and White Niles (in Khartoum in central Sudan), or ...

( Sudan), and Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

. An indigenous Dacia

Dacia (, ; ) was the land inhabited by the Dacians, its core in Transylvania, stretching to the Danube in the south, the Black Sea in the east, and the Tisza in the west. The Carpathian Mountains were located in the middle of Dacia. It ...

n origin for the ore has been ruled out. Though Cojocaru (1999) rejects the possibility of Roman imperial coins having been melted down and used for some of the objects, Constantinescu (2003) comes to the opposite conclusion.

A comparison of mineralogical composition, smelting and forging techniques, and earlier typological analysis indicates that the gold used to make the inscribed ring, classified as Celto-Germanic, is neither as pure as that of the Graeco-Roman, nor as alloyed as that found in the Polychrome Germanic objects. These results seem to indicate that at least part of the hoard — including the inscribed ring — was composed of gold ore mined far north of Dacia

Dacia (, ; ) was the land inhabited by the Dacians, its core in Transylvania, stretching to the Danube in the south, the Black Sea in the east, and the Tisza in the west. The Carpathian Mountains were located in the middle of Dacia. It ...

, and could therefore represent objects that had been in Gothic possession prior to their southward migration (see Wielbark culture

The Wielbark culture (german: Wielbark-Willenberg-Kultur; pl, Kultura wielbarska) or East Pomeranian-Mazovian is an Iron Age archaeological complex which flourished on the territory of today's Poland from the 1st century AD to the 5th century AD. ...

, Chernyakhov culture

The Chernyakhov culture, Cherniakhiv culture or Sântana de Mureș—Chernyakhov culture was an archaeological culture that flourished between the 2nd and 5th centuries CE in a wide area of Eastern Europe, specifically in what is now Ukraine, Rom ...

). While this may cast some doubt on the traditional theory regarding a Roman-Mediterranean origin for the ring, further research is necessary before the origin of the material used in its manufacture can be identified conclusively.

Burial

As with most finds of this type, it remains unclear as to why the objects were placed within the barrow, though several plausible reasons have been proposed. Taylor argues that the ring-barrow in which the objects were found was likely the site of a pagan temple, and that, based on an analysis of the surviving inscription (see below), they were part of a votive hoard indicative of a still-active paganism.Taylor (1879:8). Though this theory has been largely ignored, later research, notably that of Looijenga (1997), has observed that all of the remaining objects in the hoard possess a "definite ceremonial character". Particularly noteworthy in this connection is thePatera

In the material culture of classical antiquity, a ''phiale'' ( ) or ''patera'' () is a shallow ceramic or metal libation bowl. It often has a bulbous indentation (''omphalos'', "bellybutton") in the center underside to facilitate holding it, in ...

, or libation dish, which is decorated with depictions of (probably Germanic) deities.

Those in favour of viewing the objects as the personal hoard of Athanaric suggest that the gold was buried in an attempt to hide it from the Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part ...

, who had defeated the Gothic Greuthungi

The Greuthungi (also spelled Greutungi) were a Gothic people who lived on the Pontic steppe between the Dniester and Don rivers in what is now Ukraine, in the 3rd and the 4th centuries. They had close contacts with the Tervingi, another Gothic ...

north of the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

and began moving down into Thervingian Dacia

Dacia (, ; ) was the land inhabited by the Dacians, its core in Transylvania, stretching to the Danube in the south, the Black Sea in the east, and the Tisza in the west. The Carpathian Mountains were located in the middle of Dacia. It ...

around 375. However, it remains unclear why the gold would have remained buried, as Athanaric's treaty

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal pe ...

with Theodosius I

Theodosius I ( grc-gre, Θεοδόσιος ; 11 January 347 – 17 January 395), also called Theodosius the Great, was Roman emperor from 379 to 395. During his reign, he succeeded in a crucial war against the Goths, as well as in two ...

(380) enabled him to bring his tribesmen under the protection of Roman rule prior to his death in 381. Other researchers have suggested that the hoard was that of an Ostrogothic

The Ostrogoths ( la, Ostrogothi, Austrogothi) were a Roman-era Germanic people. In the 5th century, they followed the Visigoths in creating one of the two great Gothic kingdoms within the Roman Empire, based upon the large Gothic populations who ...

king, with Rusu (1984) specifically identifying Gainnas, a Gothic general in the Roman army who was killed by the Huns around 400, as the owner of the hoard. Although this would help explain why the hoard remained buried, it fails to account for the conspicuous ring-barrow having been chosen as the site to hide such a large and valuable treasure.

Date

Various dates for the burial of the hoard have been proposed, largely derived from considerations regarding the origin of the objects themselves and their manner of burial, though the inscription has also been an important factor (see below). Taylor suggests a range from 210 to 250. In more recent studies, scholars have proposed slightly later dates, with supporters of the Athanaric theory suggesting the end of the 4th century, the date also proposed by Constantinescu, and Tomescu suggesting the early 5th century.Inscription

Reconstruction and interpretation

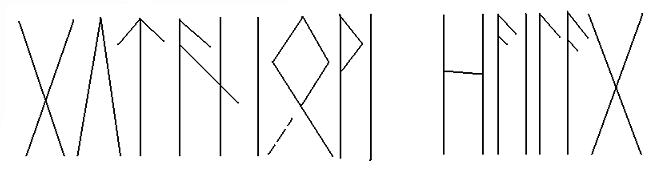

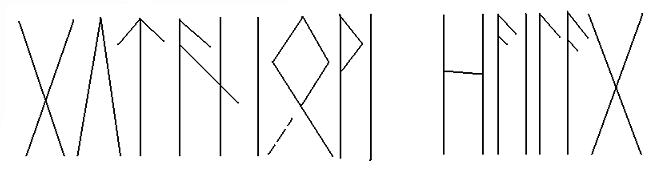

The gold ring bears an Elder Futhark runic inscription of 15 characters, with the 7th (probably ᛟ /o/) having been mostly destroyed when the ring was cut in half by thieves. The damaged rune has been the object of some scholarly debate, and is variously interpreted as indicating ᛃ /j/ (Reichert 1993, Nedoma 1993) or possibly ᛋ /s/ (Looijenga 1997). If the photograph of the Arundel Society is to be taken as a guide, then the inscription originally read as follows: : gutaniowi hailag : This reading was followed by early scholars, notably Taylor, who translates "dedicated to the temple of the Goths", and Diculescu (1923), who translates "sacred (''hailag'') to the Jove (''iowī'', i.e.Thor

Thor (; from non, Þórr ) is a prominent god in Germanic paganism. In Norse mythology, he is a hammer-wielding god associated with lightning, thunder, storms, sacred groves and trees, strength, the protection of humankind, hallowing, an ...

) of the Goths". Düwel (2001), commenting upon the same reading, suggests interpreting ᛟ as indicative of ''ō'' 'þal''thus:

: ''gutanī ō'' 'þal''''wī'' 'h''''hailag''

This, following Krause (1966), translates as "sacred (and) inviolable inheritance of the Goths". Other scholars have interpreted the ᛟ as indicative of a feminine ending: Johnsen (1971) translates "the holy relic (= the ltarring) of Gutaniō"; Krogmann (1978), reading ᛗ /m/ for ᚹᛁ /wi/, translates "dedicated to the Gothic Mothers (= female guardian spirits of the Goths)"; Antonsen (2002) translates "Sacrosanct of Gothic women/ female warriors". Construing the damaged rune as ᛋ /s/, Looijenga (1997) reads:

: ''gutanīs wī'' 'h''' hailag''

She comments that ''gutanīs'' should be understood as an early form of Gothic ''gutaneis'', "Gothic", and ''wī'' 'h''as early Gothic ''weih'', "sanctuary". Following this reading, she translates the whole inscription "Gothic (object). Sacrosanct." Reichert (1993) suggests that it is also possible to read the damaged rune as ᛃ /j/, and interprets it as representative of ''j'' 'ēra'' thus:

: ''gutanī j'' 'era''''wī'' 'h''''hailag''

Reichert translates this as "(good) year of the Goths, sacred (and) inviolable ''hailag''". Though Düwel (2001) has expressed doubts regarding the meaning of such a statement, Nordgren (2004) supports Reichert's reading, viewing the ring as connected to a sacral

Sacral may refer to:

*Sacred

Sacred describes something that is dedicated or set apart for the service or worship of a deity; is considered worthy of spiritual respect or devotion; or inspires awe or reverence among believers. The property ...

king in his role of ensuring an abundant harvest (represented by ᛃ jera). Pieper (2003) reads the damaged rune as ᛝ /ŋ/, thus:

: ''gutanī'' 'i''(''ng'')'wi'' 'n''''hailag''

He translates this " oIngwin

Old Norse Yngvi , Old High German Ing/Ingwi and Old English Ingƿine are names that relate to a theonym which appears to have been the older name for the god Freyr. Proto-Germanic *Ingwaz was the legendary ancestor of the Ingaevones, or more acc ...

of the Goths. Holy."

Meaning

Despite the lack of consensus regarding the exact import of the inscription, scholars seem to agree that its language is some form of Gothic and that the intent behind it was religious. Taylor interprets the inscription as being clearly pagan in nature and indicative of the existence of a temple to which the ring was avotive offering

A votive offering or votive deposit is one or more objects displayed or deposited, without the intention of recovery or use, in a sacred place for religious purposes. Such items are a feature of modern and ancient societies and are generally ...

. He derives his date for the burial (210 to 250) from the fact that the Christianizing of the Goths along the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , p ...

is generally considered to have been almost complete within a few generations after their having arrived there in 238. Though paganism among the Goths did survive the initial conversion phase of 250 to 300 – as the martyring of the converted Christian Goths Wereka, Batwin (370) and Sabbas Sabbas (Σάββας pronounced Sávvas) is a Greek masculine given name.

Variant forms or transliterations include Sabas, Savas, Savvas, Saba, Sava, Savva, Savo and Sawa.

Sabbas may refer to, chronologically:

* Sabbas Stratelates (died 272), ...

(372) at the hands of the indigenously pagan Goths (in the latter case Athanaric

Athanaric or Atanaric ( la, Athanaricus; died 381) was king of several branches of the Thervingian Goths () for at least two decades in the 4th century. Throughout his reign, Athanaric was faced with invasions by the Roman Empire, the Huns and a c ...

) shows – it was weakened considerably in the following years, and the likelihood of such a deposit being made would have been greatly diminished.

MacLeod and Mees (2006), following Mees (2004), interpret the ring as possibly representing either a "temple-ring" or a "sacred oath-ring", the existence of which in pagan times is documented in Old Norse literature

Old Norse literature refers to the vernacular literature of the Scandinavian peoples up to c. 1350. It chiefly consists of Icelandic writings.

In Britain

From the 8th to the 15th centuries, Vikings and Norse settlers and their descendants colon ...

and archaeological finds. Furthermore, they suggest that the inscription could be proof of the existence of "mother goddess" worship among the Goths – echoing the well-documented worship of " mother goddesses" in other parts of the Germanic North. MacLeod and Mees also propose that the appearance of both of the Common Germanic terms denoting "holiness" (''wīh'' and ''hailag'') may help to clarify the distinction between the two concepts in the Gothic language, implying that the ring was considered holy, not only for its being connected to one or more divinities, but also in and of itself.MacLeod and Mees (2006:174) write: "The Pietroassa inscription may indicate that something associated with Gutanio was holy in one sense, then, and that something else was holy in another – the distinction may well originally have been that ''wīh'' was originally the type of holiness connected with the gods and goddesses (and hence holy sites) and ''hailag'' that of sacred or consecrated (essentially human-fashioned or used) objects in Gothic." For further discussion on the distinction between ''wīh'' and ''hailag'' in Gothic, see Green (2000:360-361)

See also

*Almáttki áss

''Almáttki áss'' (the almighty '' áss'' "god") is an unknown Norse god evoked in an Icelandic legal oath sworn on a temple ring, mentioned in Landnámabók (Hauksbók 268).

Attestations

The reference in Landnámabók is found in a section des ...

* Elder Futhark

* Gothic runic inscriptions

* Pietroasele Treasure

* Treasure of Osztrópataka

* Pietroasele

Notes

References

* * **

* * * . * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * . * * . * . * * * *

External links

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ring Of Pietroassa Germanic paganism Goths Germanic archaeological artifacts Elder Futhark inscriptions Individual necklaces Torcs Gold objects Archaeological discoveries in Romania Buzău County