Rigid-body dynamics on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In the physical science of dynamics, rigid-body dynamics studies the movement of systems of interconnected bodies under the action of external forces. The assumption that the bodies are ''rigid'' (i.e. they do not

In the physical science of dynamics, rigid-body dynamics studies the movement of systems of interconnected bodies under the action of external forces. The assumption that the bodies are ''rigid'' (i.e. they do not

File:Euler.png, Diagram of the Euler angles

File:Euler AxisAngle.png, Intrinsic rotation of a ball about a fixed axis.

File:ToupieEuler.png, Motion of a top in the Euler angles.

These are three angles, also known as yaw, pitch and roll, Navigation angles and Cardan angles. Mathematically they constitute a set of six possibilities inside the twelve possible sets of Euler angles, the ordering being the one best used for describing the orientation of a vehicle such as an airplane. In aerospace engineering they are usually referred to as Euler angles.

These are three angles, also known as yaw, pitch and roll, Navigation angles and Cardan angles. Mathematically they constitute a set of six possibilities inside the twelve possible sets of Euler angles, the ordering being the one best used for describing the orientation of a vehicle such as an airplane. In aerospace engineering they are usually referred to as Euler angles.

An important simplification to these force equations is obtained by introducing the

An important simplification to these force equations is obtained by introducing the

Chris Hecker's Rigid Body Dynamics Information

DigitalRune Knowledge Base

contains a master thesis and a collection of resources about rigid body dynamics.

F. Klein, "Note on the connection between line geometry and the mechanics of rigid bodies"

(English translation)

F. Klein, "On Sir Robert Ball's theory of screws"

(English translation)

E. Cotton, "Application of Cayley geometry to the geometric study of the displacement of a solid around a fixed point"

(English translation) {{DEFAULTSORT:Rigid Body Dynamics Rigid bodies Rigid bodies mechanics Engineering mechanics Rotational symmetry

In the physical science of dynamics, rigid-body dynamics studies the movement of systems of interconnected bodies under the action of external forces. The assumption that the bodies are ''rigid'' (i.e. they do not

In the physical science of dynamics, rigid-body dynamics studies the movement of systems of interconnected bodies under the action of external forces. The assumption that the bodies are ''rigid'' (i.e. they do not deform

Deformation can refer to:

* Deformation (engineering), changes in an object's shape or form due to the application of a force or forces.

** Deformation (physics), such changes considered and analyzed as displacements of continuum bodies.

* De ...

under the action of applied forces) simplifies analysis, by reducing the parameters that describe the configuration of the system to the translation and rotation of reference frames attached to each body. This excludes bodies that display fluid, highly elastic, and plastic

Plastics are a wide range of synthetic or semi-synthetic materials that use polymers as a main ingredient. Their plasticity makes it possible for plastics to be moulded, extruded or pressed into solid objects of various shapes. This adaptab ...

behavior.

The dynamics of a rigid body system is described by the laws of kinematics and by the application of Newton's second law ( kinetics) or their derivative form, Lagrangian mechanics

In physics, Lagrangian mechanics is a formulation of classical mechanics founded on the stationary-action principle (also known as the principle of least action). It was introduced by the Italian-French mathematician and astronomer Joseph- ...

. The solution of these equations of motion provides a description of the position, the motion and the acceleration of the individual components of the system, and overall the system itself, as a function of time. The formulation and solution of rigid body dynamics is an important tool in the computer simulation of mechanical systems.

Planar rigid body dynamics

If a system of particles moves parallel to a fixed plane, the system is said to be constrained to planar movement. In this case, Newton's laws (kinetics) for a rigid system of N particles, P, ''i''=1,...,''N'', simplify because there is no movement in the ''k'' direction. Determine theresultant force

In physics and engineering, a resultant force is the single force and associated torque obtained by combining a system of forces and torques acting on a rigid body via vector addition. The defining feature of a resultant force, or resultant for ...

and torque at a reference point R, to obtain

where r denotes the planar trajectory of each particle.

The kinematics of a rigid body yields the formula for the acceleration of the particle P in terms of the position R and acceleration A of the reference particle as well as the angular velocity vector ''ω'' and angular acceleration vector ''α'' of the rigid system of particles as,

For systems that are constrained to planar movement, the angular velocity and angular acceleration vectors are directed along k perpendicular to the plane of movement, which simplifies this acceleration equation. In this case, the acceleration vectors can be simplified by introducing the unit vectors e from the reference point R to a point r and the unit vectors , so

This yields the resultant force on the system as

and torque as

where and is the unit vector perpendicular to the plane for all of the particles P.

Use the center of mass C as the reference point, so these equations for Newton's laws simplify to become

where is the total mass and ''I'' is the moment of inertia about an axis perpendicular to the movement of the rigid system and through the center of mass.

Rigid body in three dimensions

Orientation or attitude descriptions

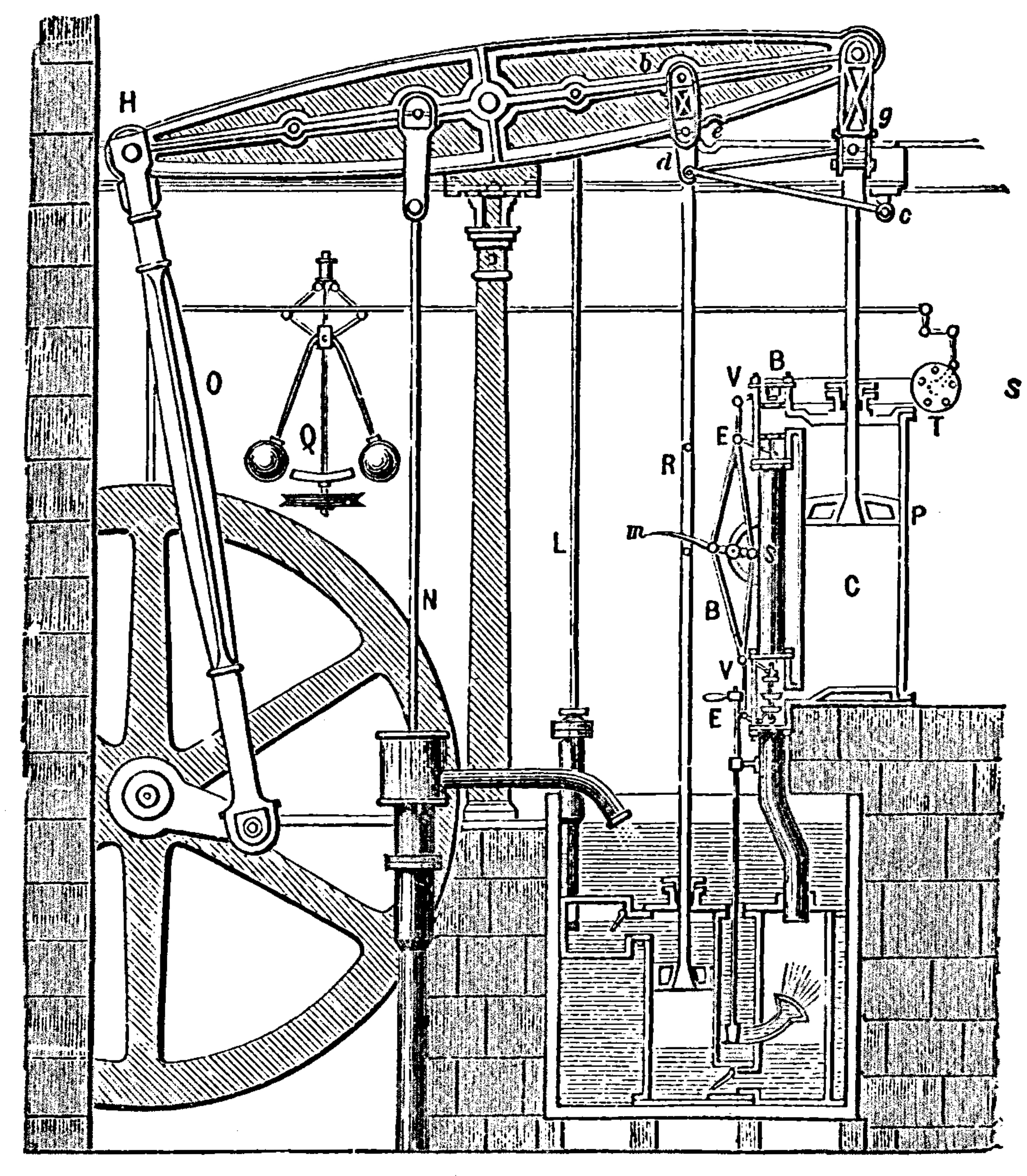

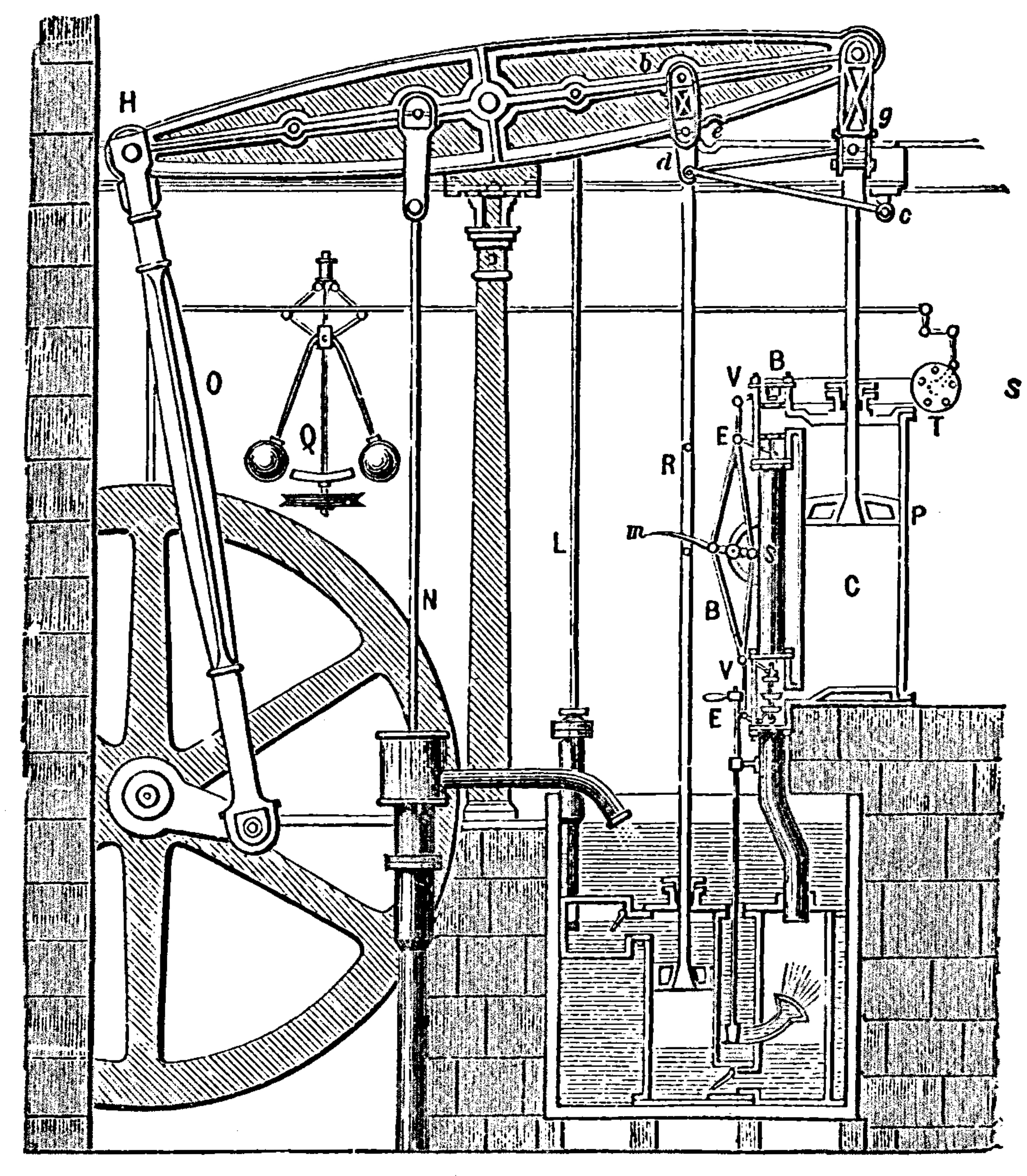

Several methods to describe orientations of a rigid body in three dimensions have been developed. They are summarized in the following sections.Euler angles

The first attempt to represent an orientation is attributed toLeonhard Euler

Leonhard Euler ( , ; 15 April 170718 September 1783) was a Swiss mathematician, physicist, astronomer, geographer, logician and engineer who founded the studies of graph theory and topology and made pioneering and influential discoveries in ma ...

. He imagined three reference frames that could rotate one around the other, and realized that by starting with a fixed reference frame and performing three rotations, he could get any other reference frame in the space (using two rotations to fix the vertical axis and another to fix the other two axes). The values of these three rotations are called Euler angles. Commonly, is used to denote precession, nutation, and intrinsic rotation.Tait–Bryan angles

Orientation vector

Euler also realized that the composition of two rotations is equivalent to a single rotation about a different fixed axis (Euler's rotation theorem

In geometry, Euler's rotation theorem states that, in three-dimensional space, any displacement of a rigid body such that a point on the rigid body remains fixed, is equivalent to a single rotation about some axis that runs through the fixed p ...

). Therefore, the composition of the former three angles has to be equal to only one rotation, whose axis was complicated to calculate until matrices were developed.

Based on this fact he introduced a vectorial way to describe any rotation, with a vector on the rotation axis and module equal to the value of the angle. Therefore, any orientation can be represented by a rotation vector (also called Euler vector) that leads to it from the reference frame. When used to represent an orientation, the rotation vector is commonly called orientation vector, or attitude vector.

A similar method, called axis-angle representation, describes a rotation or orientation using a unit vector

In mathematics, a unit vector in a normed vector space is a vector (often a spatial vector) of length 1. A unit vector is often denoted by a lowercase letter with a circumflex, or "hat", as in \hat (pronounced "v-hat").

The term ''direction v ...

aligned with the rotation axis, and a separate value to indicate the angle (see figure).

Orientation matrix

With the introduction of matrices the Euler theorems were rewritten. The rotations were described by orthogonal matrices referred to as rotation matrices or direction cosine matrices. When used to represent an orientation, a rotation matrix is commonly called orientation matrix, or attitude matrix. The above-mentioned Euler vector is theeigenvector

In linear algebra, an eigenvector () or characteristic vector of a linear transformation is a nonzero vector that changes at most by a scalar factor when that linear transformation is applied to it. The corresponding eigenvalue, often denoted ...

of a rotation matrix (a rotation matrix has a unique real eigenvalue

In linear algebra, an eigenvector () or characteristic vector of a linear transformation is a nonzero vector that changes at most by a scalar factor when that linear transformation is applied to it. The corresponding eigenvalue, often denoted ...

).

The product of two rotation matrices is the composition of rotations. Therefore, as before, the orientation can be given as the rotation from the initial frame to achieve the frame that we want to describe.

The configuration space of a non-symmetrical

Symmetry (from grc, συμμετρία "agreement in dimensions, due proportion, arrangement") in everyday language refers to a sense of harmonious and beautiful proportion and balance. In mathematics, "symmetry" has a more precise definiti ...

object in ''n''-dimensional space is SO(''n'') × R''n''. Orientation may be visualized by attaching a basis of tangent vectors

In mathematics, a tangent vector is a vector that is tangent to a curve or surface at a given point. Tangent vectors are described in the differential geometry of curves in the context of curves in R''n''. More generally, tangent vectors are eleme ...

to an object. The direction in which each vector points determines its orientation.

Orientation quaternion

Another way to describe rotations is using rotation quaternions, also called versors. They are equivalent to rotation matrices and rotation vectors. With respect to rotation vectors, they can be more easily converted to and from matrices. When used to represent orientations, rotation quaternions are typically called orientation quaternions or attitude quaternions.Newton's second law in three dimensions

To consider rigid body dynamics in three-dimensional space, Newton's second law must be extended to define the relationship between the movement of a rigid body and the system of forces and torques that act on it. Newton formulated his second law for a particle as, "The change of motion of an object is proportional to the force impressed and is made in the direction of the straight line in which the force is impressed." Because Newton generally referred to mass times velocity as the "motion" of a particle, the phrase "change of motion" refers to the mass times acceleration of the particle, and so this law is usually written as where F is understood to be the only external force acting on the particle, ''m'' is the mass of the particle, and a is its acceleration vector. The extension of Newton's second law to rigid bodies is achieved by considering a rigid system of particles.Rigid system of particles

If a system of ''N'' particles, Pi, i=1,...,''N'', are assembled into a rigid body, then Newton's second law can be applied to each of the particles in the body. If Fi is the external force applied to particle Pi with mass ''m''i, then where Fij is the internal force of particle Pj acting on particle Pi that maintains the constant distance between these particles. An important simplification to these force equations is obtained by introducing the

An important simplification to these force equations is obtained by introducing the resultant force

In physics and engineering, a resultant force is the single force and associated torque obtained by combining a system of forces and torques acting on a rigid body via vector addition. The defining feature of a resultant force, or resultant for ...

and torque that acts on the rigid system. This resultant force and torque is obtained by choosing one of the particles in the system as a reference point, R, where each of the external forces are applied with the addition of an associated torque. The resultant force F and torque T are given by the formulas,

where Ri is the vector that defines the position of particle Pi.

Newton's second law for a particle combines with these formulas for the resultant force and torque to yield,

where the internal forces F''ij'' cancel in pairs. The kinematics of a rigid body yields the formula for the acceleration of the particle Pi in terms of the position R and acceleration a of the reference particle as well as the angular velocity vector ω and angular acceleration vector α of the rigid system of particles as,

Mass properties

The mass properties of the rigid body are represented by its center of mass and inertia matrix. Choose the reference point R so that it satisfies the condition then it is known as the center of mass of the system. The inertia matrix Rof the system relative to the reference point R is defined by where is the column vector ; is its transpose, and is the 3 by 3 identity matrix. is the scalar product of with itself, while is the tensor product of with itself.Force-torque equations

Using the center of mass and inertia matrix, the force and torque equations for a single rigid body take the form and are known as Newton's second law of motion for a rigid body. The dynamics of an interconnected system of rigid bodies, , , is formulated by isolating each rigid body and introducing the interaction forces. The resultant of the external and interaction forces on each body, yields the force-torque equations Newton's formulation yields 6''M'' equations that define the dynamics of a system of ''M'' rigid bodies.Rotation in three dimensions

A rotating object, whether under the influence of torques or not, may exhibit the behaviours ofprecession

Precession is a change in the orientation of the rotational axis of a rotating body. In an appropriate reference frame it can be defined as a change in the first Euler angle, whereas the third Euler angle defines the rotation itself. In oth ...

and nutation

Nutation () is a rocking, swaying, or nodding motion in the axis of rotation of a largely axially symmetric object, such as a gyroscope, planet, or bullet in flight, or as an intended behaviour of a mechanism. In an appropriate reference frame ...

.

The fundamental equation describing the behavior of a rotating solid body is Euler's equation of motion:

where the pseudovectors τ and L are, respectively, the torque

In physics and mechanics, torque is the rotational equivalent of linear force. It is also referred to as the moment of force (also abbreviated to moment). It represents the capability of a force to produce change in the rotational motion of th ...

s on the body and its angular momentum

In physics, angular momentum (rarely, moment of momentum or rotational momentum) is the rotational analog of linear momentum. It is an important physical quantity because it is a conserved quantity—the total angular momentum of a closed syst ...

, the scalar ''I'' is its moment of inertia, the vector ω is its angular velocity, the vector α is its angular acceleration, D is the differential in an inertial reference frame and d is the differential in a relative reference frame fixed with the body.

The solution to this equation when there is no applied torque is discussed in the articles Euler's equation of motion and Poinsot's ellipsoid.

It follows from Euler's equation that a torque τ applied perpendicular to the axis of rotation, and therefore perpendicular to L, results in a rotation about an axis perpendicular to both τ and L. This motion is called ''precession''. The angular velocity of precession ΩP is given by the cross product:

Precession can be demonstrated by placing a spinning top with its axis horizontal and supported loosely (frictionless toward precession) at one end. Instead of falling, as might be expected, the top appears to defy gravity by remaining with its axis horizontal, when the other end of the axis is left unsupported and the free end of the axis slowly describes a circle in a horizontal plane, the resulting precession turning. This effect is explained by the above equations. The torque on the top is supplied by a couple of forces: gravity acting downward on the device's centre of mass, and an equal force acting upward to support one end of the device. The rotation resulting from this torque is not downward, as might be intuitively expected, causing the device to fall, but perpendicular to both the gravitational torque (horizontal and perpendicular to the axis of rotation) and the axis of rotation (horizontal and outwards from the point of support), i.e., about a vertical axis, causing the device to rotate slowly about the supporting point.

Under a constant torque of magnitude ''τ'', the speed of precession ''Ω''P is inversely proportional to ''L'', the magnitude of its angular momentum:

where ''θ'' is the angle between the vectors ΩP and L. Thus, if the top's spin slows down (for example, due to friction), its angular momentum decreases and so the rate of precession increases. This continues until the device is unable to rotate fast enough to support its own weight, when it stops precessing and falls off its support, mostly because friction against precession cause another precession that goes to cause the fall.

By convention, these three vectors - torque, spin, and precession - are all oriented with respect to each other according to the right-hand rule.

Virtual work of forces acting on a rigid body

An alternate formulation of rigid body dynamics that has a number of convenient features is obtained by considering the virtual work of forces acting on a rigid body. The virtual work of forces acting at various points on a single rigid body can be calculated using the velocities of their point of application and the resultant force and torque. To see this, let the forces F1, F2 ... F''n'' act on the points R1, R2 ... R''n'' in a rigid body. The trajectories of R''i'', are defined by the movement of the rigid body. The velocity of the points R''i'' along their trajectories are where ω is the angular velocity vector of the body.Virtual work

Work is computed from the dot product of each force with the displacement of its point of contact If the trajectory of a rigid body is defined by a set ofgeneralized coordinates

In analytical mechanics, generalized coordinates are a set of parameters used to represent the state of a system in a configuration space. These parameters must uniquely define the configuration of the system relative to a reference state.,p. 39 ...

, , then the virtual displacements are given by

The virtual work of this system of forces acting on the body in terms of the generalized coordinates becomes

or collecting the coefficients of

Generalized forces

For simplicity consider a trajectory of a rigid body that is specified by a single generalized coordinate q, such as a rotation angle, then the formula becomes Introduce the resultant force F and torque T so this equation takes the form The quantity ''Q'' defined by is known as the generalized force associated with the virtual displacement δq. This formula generalizes to the movement of a rigid body defined by more than one generalized coordinate, that is where It is useful to note that conservative forces such as gravity and spring forces are derivable from a potential function , known as a potential energy. In this case the generalized forces are given byD'Alembert's form of the principle of virtual work

The equations of motion for a mechanical system of rigid bodies can be determined using D'Alembert's form of the principle of virtual work. The principle of virtual work is used to study the static equilibrium of a system of rigid bodies, however by introducing acceleration terms in Newton's laws this approach is generalized to define dynamic equilibrium.Static equilibrium

The static equilibrium of a mechanical system rigid bodies is defined by the condition that the virtual work of the applied forces is zero for any virtual displacement of the system. This is known as the ''principle of virtual work.'' This is equivalent to the requirement that the generalized forces for any virtual displacement are zero, that is ''Q''''i''=0. Let a mechanical system be constructed from rigid bodies, B''i'', , and let the resultant of the applied forces on each body be the force-torque pairs, and , . Notice that these applied forces do not include the reaction forces where the bodies are connected. Finally, assume that the velocity and angular velocities , , for each rigid body, are defined by a single generalized coordinate q. Such a system of rigid bodies is said to have onedegree of freedom

Degrees of freedom (often abbreviated df or DOF) refers to the number of independent variables or parameters of a thermodynamic system. In various scientific fields, the word "freedom" is used to describe the limits to which physical movement or ...

.

The virtual work of the forces and torques, and , applied to this one degree of freedom system is given by

where

is the generalized force acting on this one degree of freedom system.

If the mechanical system is defined by m generalized coordinates, , , then the system has m degrees of freedom and the virtual work is given by,

where

is the generalized force associated with the generalized coordinate . The principle of virtual work states that static equilibrium occurs when these generalized forces acting on the system are zero, that is

These equations define the static equilibrium of the system of rigid bodies.

Generalized inertia forces

Consider a single rigid body which moves under the action of a resultant force F and torque T, with one degree of freedom defined by the generalized coordinate ''q''. Assume the reference point for the resultant force and torque is the center of mass of the body, then the generalized inertia force associated with the generalized coordinate is given by This inertia force can be computed from the kinetic energy of the rigid body, by using the formula A system of rigid bodies with m generalized coordinates has the kinetic energy which can be used to calculate the m generalized inertia forcesDynamic equilibrium

D'Alembert's form of the principle of virtual work states that a system of rigid bodies is in dynamic equilibrium when the virtual work of the sum of the applied forces and the inertial forces is zero for any virtual displacement of the system. Thus, dynamic equilibrium of a system of n rigid bodies with m generalized coordinates requires that for any set of virtual displacements . This condition yields equations, which can also be written as The result is a set of m equations of motion that define the dynamics of the rigid body system.Lagrange's equations

If the generalized forces Q''j'' are derivable from a potential energy , then these equations of motion take the form In this case, introduce theLagrangian

Lagrangian may refer to:

Mathematics

* Lagrangian function, used to solve constrained minimization problems in optimization theory; see Lagrange multiplier

** Lagrangian relaxation, the method of approximating a difficult constrained problem with ...

, , so these equations of motion become

These are known as Lagrange's equations of motion.

Linear and angular momentum

System of particles

The linear and angular momentum of a rigid system of particles is formulated by measuring the position and velocity of the particles relative to the center of mass. Let the system of particles Pi, be located at the coordinates r''i'' and velocities v''i''. Select a reference point R and compute the relative position and velocity vectors, The total linear and angular momentum vectors relative to the reference point R are and If R is chosen as the center of mass these equations simplify toRigid system of particles

To specialize these formulas to a rigid body, assume the particles are rigidly connected to each other so P, i=1,...,n are located by the coordinates r and velocities v. Select a reference point R and compute the relative position and velocity vectors, where ω is the angular velocity of the system. Thelinear momentum

In Newtonian mechanics, momentum (more specifically linear momentum or translational momentum) is the product of the mass and velocity of an object. It is a vector quantity, possessing a magnitude and a direction. If is an object's mass a ...

and angular momentum

In physics, angular momentum (rarely, moment of momentum or rotational momentum) is the rotational analog of linear momentum. It is an important physical quantity because it is a conserved quantity—the total angular momentum of a closed syst ...

of this rigid system measured relative to the center of mass R is

These equations simplify to become,

where M is the total mass of the system and is the moment of inertia matrix defined by

where ''i'' − Ris the skew-symmetric matrix constructed from the vector r''i'' − R.

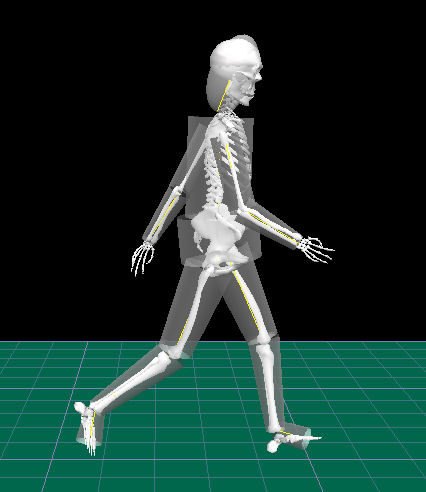

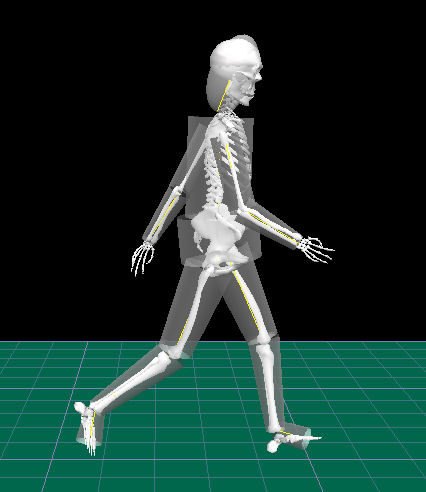

Applications

* For the analysis of robotic systems * For the biomechanical analysis of animals, humans or humanoid systems * For the analysis of space objects * For the understanding of strange motions of rigid bodies. * For the design and development of dynamics-based sensors, such as gyroscopic sensors. * For the design and development of various stability enhancement applications in automobiles. * For improving the graphics of video games which involves rigid bodiesSee also

* Analytical mechanics *Analytical dynamics

In classical mechanics, analytical dynamics, also known as classical dynamics or simply dynamics, is concerned with the relationship between Motion (physics), motion of bodies and its causes, namely the force (physics), forces acting on the bodies ...

* Calculus of variations

* Classical mechanics

Classical mechanics is a physical theory describing the motion of macroscopic objects, from projectiles to parts of machinery, and astronomical objects, such as spacecraft, planets, stars, and galaxies. For objects governed by classi ...

* Dynamics (physics)

Dynamics is the branch of classical mechanics that is concerned with the study of forces and their effects on motion. Isaac Newton was the first to formulate the fundamental physical laws that govern dynamics in classical non-relativistic physi ...

* History of classical mechanics

This article deals with the history of classical mechanics.

Precursors to classical mechanics

Antiquity

The ancient Greek philosophers, Aristotle in particular, were among the first to propose that abstract principles govern nature. Aris ...

* Lagrangian mechanics

In physics, Lagrangian mechanics is a formulation of classical mechanics founded on the stationary-action principle (also known as the principle of least action). It was introduced by the Italian-French mathematician and astronomer Joseph- ...

* Lagrangian

Lagrangian may refer to:

Mathematics

* Lagrangian function, used to solve constrained minimization problems in optimization theory; see Lagrange multiplier

** Lagrangian relaxation, the method of approximating a difficult constrained problem with ...

* Hamiltonian mechanics

Hamiltonian mechanics emerged in 1833 as a reformulation of Lagrangian mechanics. Introduced by Sir William Rowan Hamilton, Hamiltonian mechanics replaces (generalized) velocities \dot q^i used in Lagrangian mechanics with (generalized) ''momenta ...

* Rigid body

In physics, a rigid body (also known as a rigid object) is a solid body in which deformation is zero or so small it can be neglected. The distance between any two given points on a rigid body remains constant in time regardless of external fo ...

* Rigid rotor

In rotordynamics, the rigid rotor is a mechanical model of Rotation, rotating systems. An arbitrary rigid rotor is a 3-dimensional Rigid body, rigid object, such as a top. To orient such an object in space requires three angles, known as Euler an ...

* Soft body dynamics

Soft-body dynamics is a field of computer graphics that focuses on visually realistic physical simulations of the motion and properties of deformable objects (or ''soft bodies''). The applications are mostly in video games and films. Unlike in si ...

* Multibody dynamics

Multibody system is the study of the dynamic behavior of interconnected rigid or flexible bodies, each of which may undergo large translational and rotational displacements.

Introduction

The systematic treatment of the dynamic behavior of inter ...

* Polhode

* Herpolhode

* Precession

Precession is a change in the orientation of the rotational axis of a rotating body. In an appropriate reference frame it can be defined as a change in the first Euler angle, whereas the third Euler angle defines the rotation itself. In oth ...

* Poinsot's construction

* Gyroscope

* Physics engine

A physics engine is computer software that provides an approximate simulation of certain physical systems, such as rigid body dynamics (including collision detection), soft body dynamics, and fluid dynamics, of use in the domains of computer gr ...

* Physics processing unit

* Physics Abstraction Layer – Unified multibody simulator

* Dynamechs – Rigid-body simulator

* RigidChips – Japanese rigid-body simulator

* Euler's Equation

200px, Leonhard Euler (1707–1783)

In mathematics and physics, many topics are named in honor of Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler (1707–1783), who made many important discoveries and innovations. Many of these items named after Euler include ...

References

Further reading

* E. Leimanis (1965). ''The General Problem of the Motion of Coupled Rigid Bodies about a Fixed Point.'' (Springer

Springer or springers may refer to:

Publishers

* Springer Science+Business Media, aka Springer International Publishing, a worldwide publishing group founded in 1842 in Germany formerly known as Springer-Verlag.

** Springer Nature, a multinationa ...

, New York).

* W. B. Heard (2006). ''Rigid Body Mechanics: Mathematics, Physics and Applications.'' (Wiley-VCH

Wiley-VCH is a German publisher owned by John Wiley & Sons. It was founded in 1921 as Verlag Chemie (meaning "Chemistry Press": VCH stands for ''Verlag Chemie'') by two German learned societies. Later, it was merged into the German Chemical Soci ...

).

External links

Chris Hecker's Rigid Body Dynamics Information

contains a master thesis and a collection of resources about rigid body dynamics.

F. Klein, "Note on the connection between line geometry and the mechanics of rigid bodies"

(English translation)

F. Klein, "On Sir Robert Ball's theory of screws"

(English translation)

E. Cotton, "Application of Cayley geometry to the geometric study of the displacement of a solid around a fixed point"

(English translation) {{DEFAULTSORT:Rigid Body Dynamics Rigid bodies Rigid bodies mechanics Engineering mechanics Rotational symmetry