Rido on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A feud , referred to in more extreme cases as a blood feud, vendetta, faida, clan war, gang war, or private war, is a long-running argument or fight, often between social groups of people, especially family, families or clan, clans. Feuds begin because one party perceives itself to have been attacked, insulted, injured, or otherwise wronged by another. Intense feelings of resentment trigger an initial Retributive justice, retribution, which causes the other party to feel greatly aggrieved and revenge, vengeful. The dispute is subsequently fuelled by a long-running cycle of retaliatory violence. This continual cycle of provocation and retaliation usually makes it extremely difficult to end the feud peacefully. Feuds can persist for generation, generations and may result in extreme acts of violence. They can be interpreted as an extreme outgrowth of social relations based in family honor.

Until the early modern period, feuds were considered legitimate legal instruments and were regulated to some degree. For example, Montenegrin culture calls this ''krvna osveta'', meaning "blood revenge", which had unspoken but highly valued rules. In Culture of Albania, Albanian culture it is called ''Albanian blood feud, gjakmarrja'', which usually lasts for generations. In tribal societies, the blood feud, coupled with the practice of blood money (term), blood wealth, functioned as an effective form of social control for limiting and ending conflicts between individuals and groups who are related by kinship, as described by anthropologist Max Gluckman in his article "The Peace in the Feud" in 1955.

The practice has mostly disappeared with more centralized societies where law enforcement and criminal law take responsibility for punishing lawbreakers.

The practice has mostly disappeared with more centralized societies where law enforcement and criminal law take responsibility for punishing lawbreakers.

Rita of Cascia, a popular 15th-century Italian saint, was canonized by the Catholic Church due mainly to her great effort to end a feud in which her family was involved and which claimed the life of her husband.

Rita of Cascia, a popular 15th-century Italian saint, was canonized by the Catholic Church due mainly to her great effort to end a feud in which her family was involved and which claimed the life of her husband.

In Corsica, vendettas were a social code (mores) that required Corsicans to kill anyone who wronged the family honor. Between 1821 and 1852, no less than 4,300 murders were perpetrated in Corsica.

In the Spanish Late Middle Ages, the Basque Country (greater region), Vascongadas was ravaged by the War of the Bands, which were bitter partisan wars between local ruling families. In the region of Navarre, next to Vascongadas, these conflicts became polarised in a violent struggle between the Agramont and Beaumont parties. In Biscay, in Vascongadas, the two major warring factions were named Oinaz and Gamboa. (''Cf.'' the Guelphs and Ghibellines in Italy). High defensive structures ("towers") built by local noble families, few of which survive today, were frequently razed by fires, and sometimes by royal decree.

Leontiy Lyulye, an expert on conditions in the Caucasus, wrote in the mid-19th century: "Among the Peoples of the Caucasus, mountain people the blood feud is not an uncontrollable permanent feeling such as the vendetta is among the Corsicans. It is more like an obligation imposed by the public opinion." In the Dagestani ''aul'' of Kadar, Russia, Kadar, one such blood feud between two antagonistic clans lasted for nearly 260 years, from the 17th century until the 1860s.

In Corsica, vendettas were a social code (mores) that required Corsicans to kill anyone who wronged the family honor. Between 1821 and 1852, no less than 4,300 murders were perpetrated in Corsica.

In the Spanish Late Middle Ages, the Basque Country (greater region), Vascongadas was ravaged by the War of the Bands, which were bitter partisan wars between local ruling families. In the region of Navarre, next to Vascongadas, these conflicts became polarised in a violent struggle between the Agramont and Beaumont parties. In Biscay, in Vascongadas, the two major warring factions were named Oinaz and Gamboa. (''Cf.'' the Guelphs and Ghibellines in Italy). High defensive structures ("towers") built by local noble families, few of which survive today, were frequently razed by fires, and sometimes by royal decree.

Leontiy Lyulye, an expert on conditions in the Caucasus, wrote in the mid-19th century: "Among the Peoples of the Caucasus, mountain people the blood feud is not an uncontrollable permanent feeling such as the vendetta is among the Corsicans. It is more like an obligation imposed by the public opinion." In the Dagestani ''aul'' of Kadar, Russia, Kadar, one such blood feud between two antagonistic clans lasted for nearly 260 years, from the 17th century until the 1860s.

Blood feuds are still practised in some areas in:

* France (especially Corsica and within Sinti, Manush communities)

* Sardinia, where a blood feud is called Sardinian language, in the local language "Disamistade".

* Ireland (especially Dublin and Limerick)

* Southern Italy (especially Sicily, Campania, Calabria, Apulia and other areas of the same territory) and neighbouring Malta

* Greece (Mani Peninsula, Mani and Crete)

* Between White British, British Asian or Black British working-class families, crime groups and clans throughout Britain and Ireland. Feuds amongst Irish Travellers, Traveller clans are also relatively common throughout Britain and Ireland. Multiple diaspora communities also partake in feuding, such as British Turks, Turkish and British Kurds, Kurdish communities.

* Between rival Galician mafia, crime families in Galicia, Spain

* Between so-called ''woonwagenbewoners'' (ethnic Dutch people who live in mobile homes) in the Netherlands

* Among Kurdish people, Kurdish and Turkish people, Turkish clans in Turkey (as well as between Kurdish clans in Iraq and Iran)

* Between Turkish Cypriots

* Between rival clans in northern Albania and Kosovo

* Between Aboriginal peoples in Canada, Canadian Aboriginal tribes

* Among Pashtuns in Afghanistan

* Among tribes of Montenegro

*Among the Bosniaks of Sandžak, although to lesser extent in the present-day.

* Among Somali clans

* Among the Berber people, Berbers of Algeria and Morocco

* Between Yoruba people, Yoruba and Igbo people, Igbo clans over land in Nigeria

* Between clans in India and between rival tribes in the north-east Indian state of Assam

* Among Sikh clans in Punjab, India, Punjab

*Rayalaseema of Andhra Pradesh in India

* Between Mirpur, Azad Kashmir, Mirpuri clans in Azad Kashmir (as well as between British Pakistanis of Mirpuri descent in England)

* Among rival clans in China, and especially in Fujian and Guangdong provinces

* In the Philippines (especially in Mindanao between Muslim Moro people, Moro and Christian Cebuano people, Cebuano clans)

* Between Burakumin clans in Japan

* In the lawless Va people, Wa territories of northern Burma

* Among the Arab Bedouins and other Arab tribes inhabiting the mountains of Yemen

* Between Shiites and Sunnis in Iraq

* Among Palestinian people, Palestinian clans in Gaza City, Gaza

* Between Maronite clans, and between Shiites and Sunnis, in Lebanon

* Between Mhallami clans in Lebanon

* In northwest and southern Ethiopia

* Among the highland tribes of New Guinea

* In Svaneti, in Georgia (country), Georgia (especially between Svan people, Svan clans)

* In the mountainous areas of Dagestan

* Between Kyrgyz people, Kyrgyz and Uzbek people, Uzbek clans

* Between Yazidi clans in Armenia and Azerbaijan

* In republics of the northern Caucasus, such as Chechnya and Ingushetia

* Among Chechen people, Chechen teips where those seeking retribution do not accept or respect the local law enforcement authority

Blood feuds within Russian people, Russian communities do exist (mostly related to criminal gangs), but are neither as common nor as pervasive as they are in the Caucasus. In the United States, gang warfare also often takes the form of blood feuds. African-Americans, African-American, Italian-American Mafia, Italian-American, Khmer people, Cambodian, Cuban people, Cuban Marielito, Dominican people (Dominican Republic), Dominican, Guatemalan people, Guatemalan, Haitian people, Haitian, Hmong people, Hmong, Sino-Vietnamese Hoa people, Hoa, Irish Mob, Irish-American, Jamaican people, Jamaican, Korean people, Korean, Lao people, Laotian, Puerto Rican people, Puerto Rican, Salvadorans, Salvadoran and Vietnamese people, Vietnamese gangs and organized crime conflicts very often have taken the form of blood feuds, in which a family member in the gang is killed and a relative takes revenge by killing the murderer as well as other members of the rival gang. This can also be observed in particular cases in conflicts among Colombian, Mexicans, Mexican, Brazilians, Brazilian, and other Latin American gangs, drug cartels, and paramilitary groups; in turf wars among Cape Coloureds, Cape Coloured gangs in South Africa; in gang fights among Dutch Antilleans, Dutch Antillean, Surinamese people, Surinamese and Moluccans, Moluccan gangs in the Netherlands; and in criminal feuds between Scottish people, Scottish, White British, Black British, Black and Mixed British gangs in the UK. This has resulted in gun violence and murders in cities like Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles, Miami, Ciudad Juarez, Medellin, Rio de Janeiro, Cape Town, Amsterdam, London, Liverpool, and Glasgow, to name just a few.

Blood feuds also have a long history within the White Southerners, White Southerner population (and in particular among the Scots-Irish American, "Scots-Irish" or Ulster Scots American population) of the Southern United States, where it is called the "Culture of honor (Southern United States), culture of honor", and still exists to the present day.

Blood feuds are still practised in some areas in:

* France (especially Corsica and within Sinti, Manush communities)

* Sardinia, where a blood feud is called Sardinian language, in the local language "Disamistade".

* Ireland (especially Dublin and Limerick)

* Southern Italy (especially Sicily, Campania, Calabria, Apulia and other areas of the same territory) and neighbouring Malta

* Greece (Mani Peninsula, Mani and Crete)

* Between White British, British Asian or Black British working-class families, crime groups and clans throughout Britain and Ireland. Feuds amongst Irish Travellers, Traveller clans are also relatively common throughout Britain and Ireland. Multiple diaspora communities also partake in feuding, such as British Turks, Turkish and British Kurds, Kurdish communities.

* Between rival Galician mafia, crime families in Galicia, Spain

* Between so-called ''woonwagenbewoners'' (ethnic Dutch people who live in mobile homes) in the Netherlands

* Among Kurdish people, Kurdish and Turkish people, Turkish clans in Turkey (as well as between Kurdish clans in Iraq and Iran)

* Between Turkish Cypriots

* Between rival clans in northern Albania and Kosovo

* Between Aboriginal peoples in Canada, Canadian Aboriginal tribes

* Among Pashtuns in Afghanistan

* Among tribes of Montenegro

*Among the Bosniaks of Sandžak, although to lesser extent in the present-day.

* Among Somali clans

* Among the Berber people, Berbers of Algeria and Morocco

* Between Yoruba people, Yoruba and Igbo people, Igbo clans over land in Nigeria

* Between clans in India and between rival tribes in the north-east Indian state of Assam

* Among Sikh clans in Punjab, India, Punjab

*Rayalaseema of Andhra Pradesh in India

* Between Mirpur, Azad Kashmir, Mirpuri clans in Azad Kashmir (as well as between British Pakistanis of Mirpuri descent in England)

* Among rival clans in China, and especially in Fujian and Guangdong provinces

* In the Philippines (especially in Mindanao between Muslim Moro people, Moro and Christian Cebuano people, Cebuano clans)

* Between Burakumin clans in Japan

* In the lawless Va people, Wa territories of northern Burma

* Among the Arab Bedouins and other Arab tribes inhabiting the mountains of Yemen

* Between Shiites and Sunnis in Iraq

* Among Palestinian people, Palestinian clans in Gaza City, Gaza

* Between Maronite clans, and between Shiites and Sunnis, in Lebanon

* Between Mhallami clans in Lebanon

* In northwest and southern Ethiopia

* Among the highland tribes of New Guinea

* In Svaneti, in Georgia (country), Georgia (especially between Svan people, Svan clans)

* In the mountainous areas of Dagestan

* Between Kyrgyz people, Kyrgyz and Uzbek people, Uzbek clans

* Between Yazidi clans in Armenia and Azerbaijan

* In republics of the northern Caucasus, such as Chechnya and Ingushetia

* Among Chechen people, Chechen teips where those seeking retribution do not accept or respect the local law enforcement authority

Blood feuds within Russian people, Russian communities do exist (mostly related to criminal gangs), but are neither as common nor as pervasive as they are in the Caucasus. In the United States, gang warfare also often takes the form of blood feuds. African-Americans, African-American, Italian-American Mafia, Italian-American, Khmer people, Cambodian, Cuban people, Cuban Marielito, Dominican people (Dominican Republic), Dominican, Guatemalan people, Guatemalan, Haitian people, Haitian, Hmong people, Hmong, Sino-Vietnamese Hoa people, Hoa, Irish Mob, Irish-American, Jamaican people, Jamaican, Korean people, Korean, Lao people, Laotian, Puerto Rican people, Puerto Rican, Salvadorans, Salvadoran and Vietnamese people, Vietnamese gangs and organized crime conflicts very often have taken the form of blood feuds, in which a family member in the gang is killed and a relative takes revenge by killing the murderer as well as other members of the rival gang. This can also be observed in particular cases in conflicts among Colombian, Mexicans, Mexican, Brazilians, Brazilian, and other Latin American gangs, drug cartels, and paramilitary groups; in turf wars among Cape Coloureds, Cape Coloured gangs in South Africa; in gang fights among Dutch Antilleans, Dutch Antillean, Surinamese people, Surinamese and Moluccans, Moluccan gangs in the Netherlands; and in criminal feuds between Scottish people, Scottish, White British, Black British, Black and Mixed British gangs in the UK. This has resulted in gun violence and murders in cities like Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles, Miami, Ciudad Juarez, Medellin, Rio de Janeiro, Cape Town, Amsterdam, London, Liverpool, and Glasgow, to name just a few.

Blood feuds also have a long history within the White Southerners, White Southerner population (and in particular among the Scots-Irish American, "Scots-Irish" or Ulster Scots American population) of the Southern United States, where it is called the "Culture of honor (Southern United States), culture of honor", and still exists to the present day.

In Albania, ''gjakmarrja'' (blood feuding) is a tradition. Blood feuds in Albania trace back to the Kanun (Albania), Kanun, this custom is also practiced among the Albanians of Kosovo. It returned to rural areas after more than 40 years of being abolished by Albanian Communists led by Enver Hoxha.

In 1980, Albanian author Ismail Kadare published ''Broken April'', about the centuries-old tradition of hospitality, blood feuds, and revenge killing in the highlands of north Albania in the 1930s. ''The New York Times'', reviewing it, wrote: "''Broken April'' is written with masterly simplicity in a bardic style, as if the author is saying: Sit quietly and let me recite a terrible story about a blood feud and the inevitability of death by gunfire in my country. You know it must happen because that is the way life is lived in these mountains. Insults must be avenged; family honor must be upheld...." The novel was made into a 2001 movie entitled ''Behind the Sun (film), Behind the Sun'' by filmmaker Walter Salles, set in 1910 Brazil and starring Rodrigo Santoro, which was nominated for a BAFTA Award for Best Film Not in the English Language and a Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Language Film.

There are now more than 1,600 families who live under an ever-present death sentence because of feuds, and since 1992, at least 10,000 Albanians have been killed in them.

In Albania, ''gjakmarrja'' (blood feuding) is a tradition. Blood feuds in Albania trace back to the Kanun (Albania), Kanun, this custom is also practiced among the Albanians of Kosovo. It returned to rural areas after more than 40 years of being abolished by Albanian Communists led by Enver Hoxha.

In 1980, Albanian author Ismail Kadare published ''Broken April'', about the centuries-old tradition of hospitality, blood feuds, and revenge killing in the highlands of north Albania in the 1930s. ''The New York Times'', reviewing it, wrote: "''Broken April'' is written with masterly simplicity in a bardic style, as if the author is saying: Sit quietly and let me recite a terrible story about a blood feud and the inevitability of death by gunfire in my country. You know it must happen because that is the way life is lived in these mountains. Insults must be avenged; family honor must be upheld...." The novel was made into a 2001 movie entitled ''Behind the Sun (film), Behind the Sun'' by filmmaker Walter Salles, set in 1910 Brazil and starring Rodrigo Santoro, which was nominated for a BAFTA Award for Best Film Not in the English Language and a Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Language Film.

There are now more than 1,600 families who live under an ever-present death sentence because of feuds, and since 1992, at least 10,000 Albanians have been killed in them.

*Three Kingdoms period, feuding warlords during the fall of the Han Dynasty (184–280 AD; China)

*Njál's saga, an Icelandic account of a Norsemen, Norse blood feud (960–1020; Iceland, Ireland and Norway)

* (975/977–980) in Kyivan Rus'

*The Clan Mackintosh, Mackintosh-Clan Cameron, Cameron Stand-off at the Fords of Arkaig, feud (1290s–1665; Scotland)

*The Battle of the North Inch; the battle is fictionalised in the novel ''The Fair Maid of Perth'' by Sir Walter Scott (Michaelmas 1396; Scotland)

*The Krummedige-Tre Rosor feud (1448–1502; Norway)

*The Bonville–Courtenay feud (1450s; England)

*The Percy–Neville feud (1450s; England)

*The Wars of the Roses (1455–1487; England)

*The Viscount Lisle, Talbot–Baron Berkeley, Berkeley feud (1455–1485 England) (concurrent with the Wars of the Roses)

*The Clan Gunn, Gunn–Clan Keith, Keith feud (1464–1978; Scotland)

*The Clan Campbell, Campbell–Clan MacDonald, MacDonald feud, including the Massacre of Glencoe (1692; Scotland)

*The Clan Forbes–Clan Gordon feud, (1500s–1571; Scotland)

*The Clan Forbes–Clan Leslie feud, (1520s–1530s; Scotland)

*The Clan Forbes–City of Aberdeen feud, (1529–1539; Scotland)

*The Regulator-Moderator War, (1839–1844; Republic of Texas)

*The Punti–Hakka Clan Wars, (1855–1868; Guangdong, China)

*The Black Donnellys#The feud, Donnelly–Biddulph community feud (1857–1880; Ontario, Canada)

*The Lincoln County War (1878–1881; New Mexico, United States)

*The Lincoln County Feud (1878–1890; West Virginia, United States)

*The Hatfield-McCoy feud (1878–1891; West Virginia & Kentucky, United States)

*The Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, Clanton/McLaury–Earp feud (see also Earp Vendetta Ride), also known as the "Gunfight at the O.K. Corral" (1881; Arizona, United States)

*The Pleasant Valley War, also known as the "Tonto Basin Feud" (1882–1892; Arizona, United States)

*The Al Capone, Capone–Bugs Moran, Moran feud, including the St. Valentine's Day massacre (1925–1930; Chicago, Illinois, United States)

*The Castellammarese War (1929–1931; New York City, New York United States)

*The Cohen crime family, Battle of the Sunset Strip (1947–1951; Los Angeles, California United States)

*The First Colombo crime family, Colombo Family War (1960–1963; New York City, United States)

*The Second Colombo Family War (1971–1975; New York City, United States)

*The Philadelphia crime family, Riccobene War (1982–1984; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States)

*The Internal Patriarca crime family, Patriarca War (1991–1996; Boston, Massachusetts, United States)

*Second Mafia War, Great Mafia War (1981–1983; Sicily, Italy)

*The Feud of Scampia (2004–2005; Naples, Italy)

*The Maguindanao Massacre (2009; Ampatuan, Maguindanao, Ampatuan, Philippines)

*The Limerick feud (2000–present; Limerick, Ireland)

*The Rizzuto crime family, Montreal Mafia War (2009–present; mostly the Canada, Canadian provinces of Quebec and Ontario)

*Three Kingdoms period, feuding warlords during the fall of the Han Dynasty (184–280 AD; China)

*Njál's saga, an Icelandic account of a Norsemen, Norse blood feud (960–1020; Iceland, Ireland and Norway)

* (975/977–980) in Kyivan Rus'

*The Clan Mackintosh, Mackintosh-Clan Cameron, Cameron Stand-off at the Fords of Arkaig, feud (1290s–1665; Scotland)

*The Battle of the North Inch; the battle is fictionalised in the novel ''The Fair Maid of Perth'' by Sir Walter Scott (Michaelmas 1396; Scotland)

*The Krummedige-Tre Rosor feud (1448–1502; Norway)

*The Bonville–Courtenay feud (1450s; England)

*The Percy–Neville feud (1450s; England)

*The Wars of the Roses (1455–1487; England)

*The Viscount Lisle, Talbot–Baron Berkeley, Berkeley feud (1455–1485 England) (concurrent with the Wars of the Roses)

*The Clan Gunn, Gunn–Clan Keith, Keith feud (1464–1978; Scotland)

*The Clan Campbell, Campbell–Clan MacDonald, MacDonald feud, including the Massacre of Glencoe (1692; Scotland)

*The Clan Forbes–Clan Gordon feud, (1500s–1571; Scotland)

*The Clan Forbes–Clan Leslie feud, (1520s–1530s; Scotland)

*The Clan Forbes–City of Aberdeen feud, (1529–1539; Scotland)

*The Regulator-Moderator War, (1839–1844; Republic of Texas)

*The Punti–Hakka Clan Wars, (1855–1868; Guangdong, China)

*The Black Donnellys#The feud, Donnelly–Biddulph community feud (1857–1880; Ontario, Canada)

*The Lincoln County War (1878–1881; New Mexico, United States)

*The Lincoln County Feud (1878–1890; West Virginia, United States)

*The Hatfield-McCoy feud (1878–1891; West Virginia & Kentucky, United States)

*The Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, Clanton/McLaury–Earp feud (see also Earp Vendetta Ride), also known as the "Gunfight at the O.K. Corral" (1881; Arizona, United States)

*The Pleasant Valley War, also known as the "Tonto Basin Feud" (1882–1892; Arizona, United States)

*The Al Capone, Capone–Bugs Moran, Moran feud, including the St. Valentine's Day massacre (1925–1930; Chicago, Illinois, United States)

*The Castellammarese War (1929–1931; New York City, New York United States)

*The Cohen crime family, Battle of the Sunset Strip (1947–1951; Los Angeles, California United States)

*The First Colombo crime family, Colombo Family War (1960–1963; New York City, United States)

*The Second Colombo Family War (1971–1975; New York City, United States)

*The Philadelphia crime family, Riccobene War (1982–1984; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States)

*The Internal Patriarca crime family, Patriarca War (1991–1996; Boston, Massachusetts, United States)

*Second Mafia War, Great Mafia War (1981–1983; Sicily, Italy)

*The Feud of Scampia (2004–2005; Naples, Italy)

*The Maguindanao Massacre (2009; Ampatuan, Maguindanao, Ampatuan, Philippines)

*The Limerick feud (2000–present; Limerick, Ireland)

*The Rizzuto crime family, Montreal Mafia War (2009–present; mostly the Canada, Canadian provinces of Quebec and Ontario)

PDF

* Miller, William Ian. 1990. ''Bloodtaking and peacemaking : feud, law, and society in Saga Iceland''. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. * Torres, Wilfredo M. (ed). 2007. ''Rido: Clan Feuding and Conflict Management in Mindanao''. Makati: The Asia Foundation

PDF

* Torres, Wilfredo M. 2010. "Letting A Thousand Flowers Bloom: Clan Conflicts and their Management." ''Challenges to Human Security in Complex Situations: The Case of Conflict in the Southern Philippines''. Kuala Lumpur: Asian Disaster Reduction and Response Network (ADRRN)

PDF

* Boehm, Christopher. 1984. ''Blood Revenge: The Anthropology of Feuding in Montenegro and Other Tribal Societies''. Lawrence, Kansas, Lawrence: University of Kansas

at Google Books

BBC: "In pictures: Egypt vendetta ends"

May, 2005. "One of the most enduring and bloody family feuds of modern times in Upper Egypt has ended with a tense ceremony of humiliation and forgiveness. [...] Police are edgy. After lengthy peace talks, no one knows if the penance — and a large payment of blood money — will end the vendetta which began in 1991 with a children's fight."

15 clan feuds settled in Lanao; rido tops cause of evacuation more than war

from the MindaNews website. Posted on 13 July 2007.

2 clans in Matanog settle rido, sign peace pact

from the MindaNews website. Posted on 30 January 2008.

Albania: Feuding families…bitter livesBlood feuds blight Albanian livesBlood feuds tearing Gaza apartCalabrian clan feud suspected in slayings

Children as teacher-facilitators for peace

from the Inquirer website. Posted on 29 September 2007.

Family Feud in Ireland Involves 200 RiotersGangs clash in Nigerian oil cityIraq's death squads: On the brink of civil warMafia feuds bring bloodshed to Naples' streetsMaratabat and the Maranaos

from the blog of Datu Jamal Ashley Yahya Abbas, originally in "Reflections on the Bangsa Moro." Posted on 1 May 2007.

Mexico drugs cartels feud erupts

*

Rido

', from The Asia Foundation's ''Rido'' Map website.

''Rido'' and its Influence on the Academe, NGOs and the Military

an essay from the website of the Balay Mindanaw Foundation, Inc. Posted on 28 February 2007.

'Rido' seen [as] major Mindanao security concern

from the Inquirer website. Posted on 18 November 2006.

Thousands fear as blood feuds sweep AlbaniaTribal warfare kills nine in Indonesia's Papua

Villages in "rido" area return home

from the MindaNews website. Posted on 1 November 2007.

*[http://www.stippy.com/japan-news-and-media/a-yakuza-war-has-started-in-central-tokyo/ A "Yakuza War" has started in Central Tokyo] {{Authority control Feuds, Gangland warfare tactics Revenge Violence Violent crime Interpersonal conflict

Blood feuds

A blood feud is a feud with a cycle of retaliatory violence, with the relatives or associates of someone who has been killed or otherwise wronged or honor, dishonored seeking vengeance by killing or otherwise physically punishing the culprits or their relatives. In the English-speaking world, the Italian word ''vendetta'' is used to mean a blood feud; in Italian, however, it simply means (personal) "vengeance" or "revenge", originating from the Latin ''vindicta'' (wikt:vengeance, vengeance), while the word '':wiktionary:faida, faida'' would be more appropriate for a blood feud. In the English-speaking world, "vendetta" is sometimes extended to mean any other long-standing feud, not necessarily involving bloodshed. Sometimes it is not mutual, but rather refers to a prolonged series of hostile acts waged by one person against another without reciprocation.History

Blood feuds were common in societies with a weak rule of law (or where the state did not consider itself responsible for mediating this kind of dispute), where family and kinship ties were the main source of authority. An entire family was considered responsible for the actions of any of its members. Sometimes two separate branches of the same family even came to blows, or worse, over some dispute.Feuds in Antiquity

In Homeric ancient Greece, the practice of personal vengeance against wrongdoers was considered natural and customary: "Embedded in the Greek morality of retaliation is the right of vengeance... Feud is a war, just as war is an indefinite series of revenges; and such acts of vengeance are sanctioned by the gods". In the Ancient Israel, ancient Hebraic context, it was considered the duty of the individual and family to avenge unlawful bloodshed, on behalf of God and on behalf of the deceased. The executor of the law of blood-revenge who personally put the initial killer to death was given a special designation: ''go'el haddam'', the blood-avenger or blood-redeemer (Book of Numbers 35: 19, etc.). Six Cities of Refuge were established to provide protection and due process for any unintentional manslayers. The avenger was forbidden from harming an :he:רוצח בשגגה, unintentional killer if the killer took refuge in one of these cities. As the ''Oxford Companion to the Bible'' states: "Since life was viewed as sacred (Book of Genesis, Genesis 9.6), no amount of blood money (term), blood money could be given as recompense for the loss of the life of an innocent person; it had to be lex talionis, "life for life" (Book of Exodus, Exodus 21.23; Deuteronomy 19.21)". According to historian Marc Bloch: Rita of Cascia, a popular 15th-century Italian saint, was canonized by the Catholic Church due mainly to her great effort to end a feud in which her family was involved and which claimed the life of her husband.

Rita of Cascia, a popular 15th-century Italian saint, was canonized by the Catholic Church due mainly to her great effort to end a feud in which her family was involved and which claimed the life of her husband.

Feuds in pre-industrial tribes

The blood feud has certain similarities to the ritualized warfare found in many pre-industrial tribes. For instance, more than a third of Ya̧nomamö males, on average, died from Prehistoric warfare, warfare. The accounts of missionaries to the area have recounted constant infighting in the tribes for women or prestige, and evidence of continuous warfare for the enslavement of neighboring tribes, such as the Marueta people, Macu, before the arrival of European settlers and government.Keeley, Lawrence H. ''War Before Civilization, War Before Civilization: The Myth of the Peaceful Savage'' Oxford University Press, 1996Samurai honours and feuds

In Japan's feudal past, the samurai class upheld the honor of their family, clan, and their lord by ''katakiuchi'' (), or revenge killings. These killings could also involve the relatives of an offender. While some vendettas were punished by the government, such as that of the Forty-seven Ronin, others were given official permission with specific targets.Feuds in Medieval and Renaissance Europe

At the Holy Roman Empire's Diet of Worms (1495), ''Reichstag'' at Worms in 1495 AD, the right of waging feuds was abolished. The Imperial Reform proclaimed an "eternal public peace" (''Ewiger Landfriede'') to put an end to the abounding feuds and the anarchy of the Robber baron (feudalism), robber barons, and it defined a new standing army, standing imperial army to enforce that peace. However, it took a few more decades until the new regulation was universally accepted. In 1506, for example, knight Jan Kopidlansky killed a family rival in Prague, and the town councillors sentenced him to death and had him executed. His brother, Jiri Kopidlansky, declared a private war against the city of Prague. Another case was the Nuremberg v. Konrad Schott von Schottenstein, Nuremberg-Schott feud, in which Maximilian was forced to step in to halt the damages done by robber knight Schott. In Greece, the custom of blood feud is found in several parts of the country, for instance in Crete and Mani Peninsula, Mani. Throughout history, the Maniots have been regarded by their neighbors and their enemies as fearless warriors who practice Maniots#Vendettas, blood feuds, known in the Maniot dialect of Greek as "Γδικιωμός" (Gdikiomos). Many vendettas went on for months, some for years. The families involved would lock themselves in their towers and, when they got the chance, would murder members of the opposing family. The Maniot vendetta is considered the most vicious and ruthless; it has led to entire family lines being wiped out. The last vendetta on record required the Greek Army with artillery support to force it to a stop. Regardless of this, the Maniot Greeks still practice vendettas, even today. Maniots in America, Australia, Canada and Corsica still have on-going vendettas which have led to the creation of mafia families known as "Γδικιωμέοι" (Gdikiomeoi). In Corsica, vendettas were a social code (mores) that required Corsicans to kill anyone who wronged the family honor. Between 1821 and 1852, no less than 4,300 murders were perpetrated in Corsica.

In the Spanish Late Middle Ages, the Basque Country (greater region), Vascongadas was ravaged by the War of the Bands, which were bitter partisan wars between local ruling families. In the region of Navarre, next to Vascongadas, these conflicts became polarised in a violent struggle between the Agramont and Beaumont parties. In Biscay, in Vascongadas, the two major warring factions were named Oinaz and Gamboa. (''Cf.'' the Guelphs and Ghibellines in Italy). High defensive structures ("towers") built by local noble families, few of which survive today, were frequently razed by fires, and sometimes by royal decree.

Leontiy Lyulye, an expert on conditions in the Caucasus, wrote in the mid-19th century: "Among the Peoples of the Caucasus, mountain people the blood feud is not an uncontrollable permanent feeling such as the vendetta is among the Corsicans. It is more like an obligation imposed by the public opinion." In the Dagestani ''aul'' of Kadar, Russia, Kadar, one such blood feud between two antagonistic clans lasted for nearly 260 years, from the 17th century until the 1860s.

In Corsica, vendettas were a social code (mores) that required Corsicans to kill anyone who wronged the family honor. Between 1821 and 1852, no less than 4,300 murders were perpetrated in Corsica.

In the Spanish Late Middle Ages, the Basque Country (greater region), Vascongadas was ravaged by the War of the Bands, which were bitter partisan wars between local ruling families. In the region of Navarre, next to Vascongadas, these conflicts became polarised in a violent struggle between the Agramont and Beaumont parties. In Biscay, in Vascongadas, the two major warring factions were named Oinaz and Gamboa. (''Cf.'' the Guelphs and Ghibellines in Italy). High defensive structures ("towers") built by local noble families, few of which survive today, were frequently razed by fires, and sometimes by royal decree.

Leontiy Lyulye, an expert on conditions in the Caucasus, wrote in the mid-19th century: "Among the Peoples of the Caucasus, mountain people the blood feud is not an uncontrollable permanent feeling such as the vendetta is among the Corsicans. It is more like an obligation imposed by the public opinion." In the Dagestani ''aul'' of Kadar, Russia, Kadar, one such blood feud between two antagonistic clans lasted for nearly 260 years, from the 17th century until the 1860s.

Pre-Christian Northern Europe

The Celts, Celtic phenomenon of the ''blood feud'' demanded "an eye for an eye," and usually descended into murder. Disagreements between clans might last for generations in Scotland and Ireland. In Scandinavia in the Viking era, feuds were common, as the lack of a central government left dealing with disputes up to the individuals or families involved. Sometimes, these would descend into "blood revenges", and in some cases would devastate whole families. The ravages of the feuds as well as the dissolution of them is a central theme in several of the Icelandic sagas. An alternative to feud was ''blood money (term), blood money'' (or ''weregild'' in the Norsemen, Norse culture), which demanded a set value to be paid by those responsible for a wrongful permanent disfigurement or death, even if accidental. If these payments were not made, or were refused by the offended party, a blood feud could ensue.Feuds in 19th century rural USA

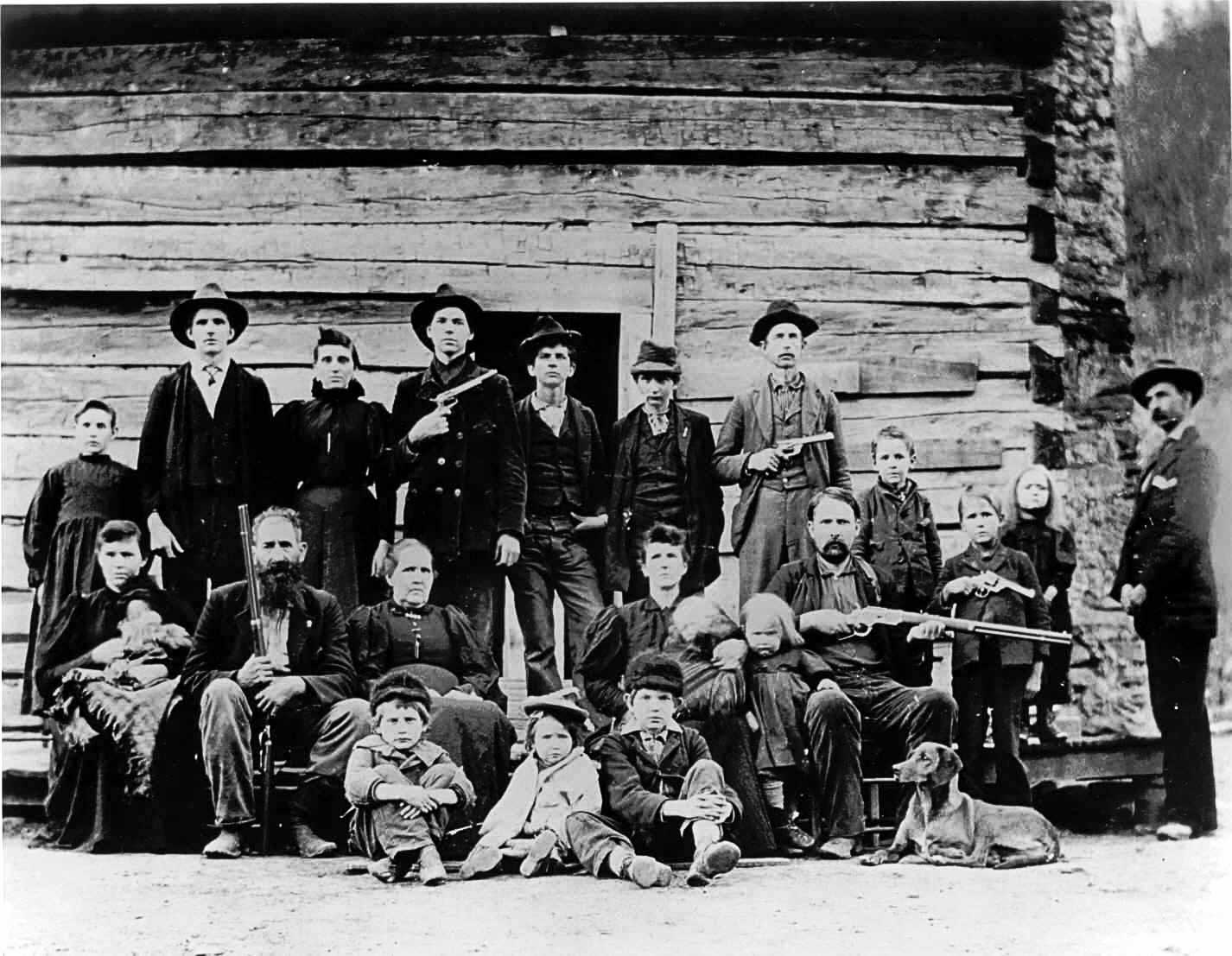

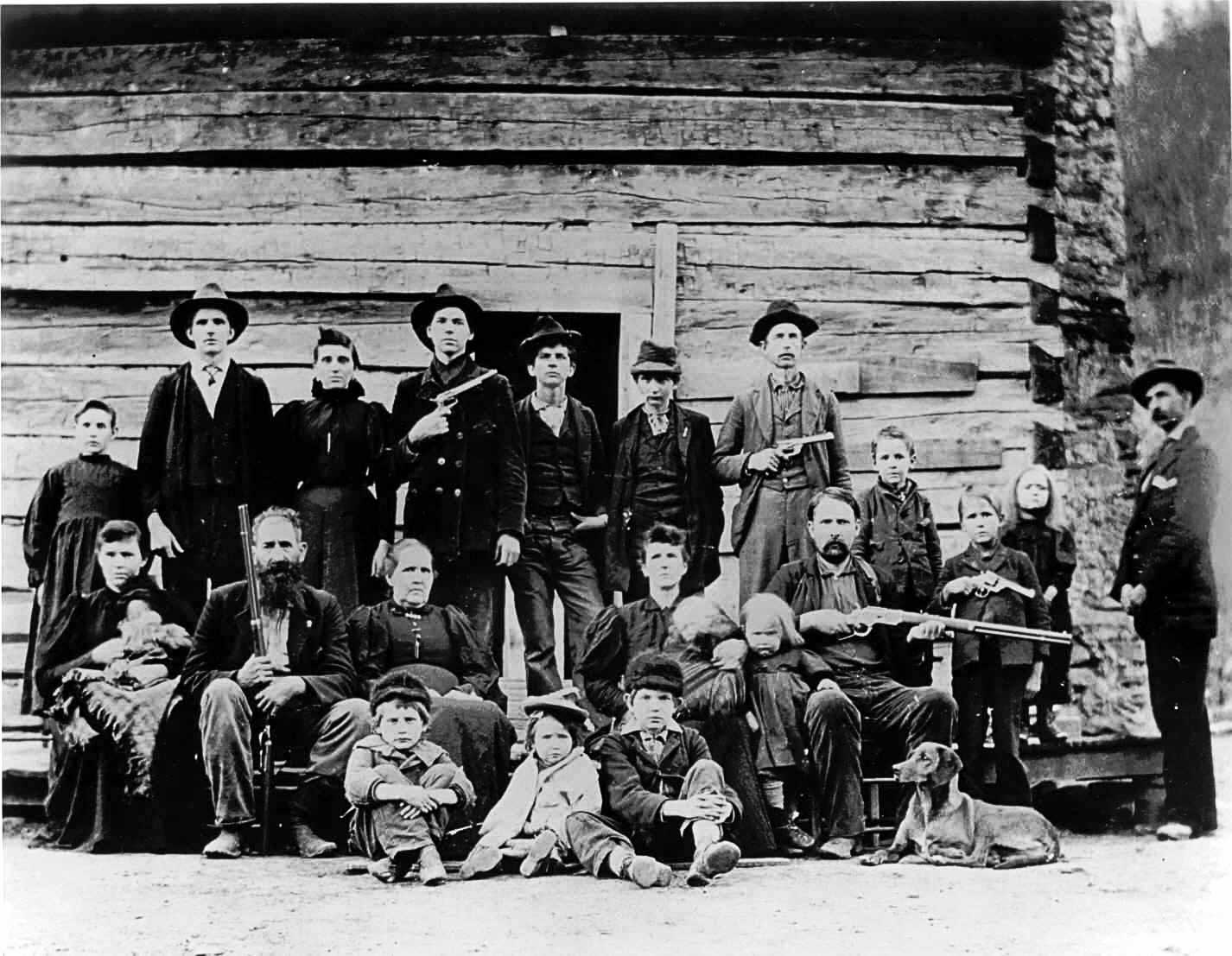

Due to the Celtic heritage of many people living in Appalachia, a series of prolonged violent engagements in late nineteenth-century Kentucky and West Virginia were referred to commonly as feuds, a tendency that was partly due to the nineteenth-century popularity of William Shakespeare and Sir Walter Scott, both of whom had written historical fiction, semihistorical accounts of blood feuds. These incidents, the most famous of which was the Hatfield–McCoy feud, were regularly featured in the newspapers of the eastern U.S. between the Reconstruction Era and the early twentieth century, and are seen by some as linked to a Culture of honor (Southern United States), Southern culture of honor with its roots in the Scotch-Irish American, Scots-Irish forebears of the residents of the area. Another prominent example was the Regulator–Moderator War, which took place between rival factions in the Republic of Texas. It is sometimes considered the largest blood feud in American history.Feuds in modern times

Blood feuds are still practised in some areas in:

* France (especially Corsica and within Sinti, Manush communities)

* Sardinia, where a blood feud is called Sardinian language, in the local language "Disamistade".

* Ireland (especially Dublin and Limerick)

* Southern Italy (especially Sicily, Campania, Calabria, Apulia and other areas of the same territory) and neighbouring Malta

* Greece (Mani Peninsula, Mani and Crete)

* Between White British, British Asian or Black British working-class families, crime groups and clans throughout Britain and Ireland. Feuds amongst Irish Travellers, Traveller clans are also relatively common throughout Britain and Ireland. Multiple diaspora communities also partake in feuding, such as British Turks, Turkish and British Kurds, Kurdish communities.

* Between rival Galician mafia, crime families in Galicia, Spain

* Between so-called ''woonwagenbewoners'' (ethnic Dutch people who live in mobile homes) in the Netherlands

* Among Kurdish people, Kurdish and Turkish people, Turkish clans in Turkey (as well as between Kurdish clans in Iraq and Iran)

* Between Turkish Cypriots

* Between rival clans in northern Albania and Kosovo

* Between Aboriginal peoples in Canada, Canadian Aboriginal tribes

* Among Pashtuns in Afghanistan

* Among tribes of Montenegro

*Among the Bosniaks of Sandžak, although to lesser extent in the present-day.

* Among Somali clans

* Among the Berber people, Berbers of Algeria and Morocco

* Between Yoruba people, Yoruba and Igbo people, Igbo clans over land in Nigeria

* Between clans in India and between rival tribes in the north-east Indian state of Assam

* Among Sikh clans in Punjab, India, Punjab

*Rayalaseema of Andhra Pradesh in India

* Between Mirpur, Azad Kashmir, Mirpuri clans in Azad Kashmir (as well as between British Pakistanis of Mirpuri descent in England)

* Among rival clans in China, and especially in Fujian and Guangdong provinces

* In the Philippines (especially in Mindanao between Muslim Moro people, Moro and Christian Cebuano people, Cebuano clans)

* Between Burakumin clans in Japan

* In the lawless Va people, Wa territories of northern Burma

* Among the Arab Bedouins and other Arab tribes inhabiting the mountains of Yemen

* Between Shiites and Sunnis in Iraq

* Among Palestinian people, Palestinian clans in Gaza City, Gaza

* Between Maronite clans, and between Shiites and Sunnis, in Lebanon

* Between Mhallami clans in Lebanon

* In northwest and southern Ethiopia

* Among the highland tribes of New Guinea

* In Svaneti, in Georgia (country), Georgia (especially between Svan people, Svan clans)

* In the mountainous areas of Dagestan

* Between Kyrgyz people, Kyrgyz and Uzbek people, Uzbek clans

* Between Yazidi clans in Armenia and Azerbaijan

* In republics of the northern Caucasus, such as Chechnya and Ingushetia

* Among Chechen people, Chechen teips where those seeking retribution do not accept or respect the local law enforcement authority

Blood feuds within Russian people, Russian communities do exist (mostly related to criminal gangs), but are neither as common nor as pervasive as they are in the Caucasus. In the United States, gang warfare also often takes the form of blood feuds. African-Americans, African-American, Italian-American Mafia, Italian-American, Khmer people, Cambodian, Cuban people, Cuban Marielito, Dominican people (Dominican Republic), Dominican, Guatemalan people, Guatemalan, Haitian people, Haitian, Hmong people, Hmong, Sino-Vietnamese Hoa people, Hoa, Irish Mob, Irish-American, Jamaican people, Jamaican, Korean people, Korean, Lao people, Laotian, Puerto Rican people, Puerto Rican, Salvadorans, Salvadoran and Vietnamese people, Vietnamese gangs and organized crime conflicts very often have taken the form of blood feuds, in which a family member in the gang is killed and a relative takes revenge by killing the murderer as well as other members of the rival gang. This can also be observed in particular cases in conflicts among Colombian, Mexicans, Mexican, Brazilians, Brazilian, and other Latin American gangs, drug cartels, and paramilitary groups; in turf wars among Cape Coloureds, Cape Coloured gangs in South Africa; in gang fights among Dutch Antilleans, Dutch Antillean, Surinamese people, Surinamese and Moluccans, Moluccan gangs in the Netherlands; and in criminal feuds between Scottish people, Scottish, White British, Black British, Black and Mixed British gangs in the UK. This has resulted in gun violence and murders in cities like Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles, Miami, Ciudad Juarez, Medellin, Rio de Janeiro, Cape Town, Amsterdam, London, Liverpool, and Glasgow, to name just a few.

Blood feuds also have a long history within the White Southerners, White Southerner population (and in particular among the Scots-Irish American, "Scots-Irish" or Ulster Scots American population) of the Southern United States, where it is called the "Culture of honor (Southern United States), culture of honor", and still exists to the present day.

Blood feuds are still practised in some areas in:

* France (especially Corsica and within Sinti, Manush communities)

* Sardinia, where a blood feud is called Sardinian language, in the local language "Disamistade".

* Ireland (especially Dublin and Limerick)

* Southern Italy (especially Sicily, Campania, Calabria, Apulia and other areas of the same territory) and neighbouring Malta

* Greece (Mani Peninsula, Mani and Crete)

* Between White British, British Asian or Black British working-class families, crime groups and clans throughout Britain and Ireland. Feuds amongst Irish Travellers, Traveller clans are also relatively common throughout Britain and Ireland. Multiple diaspora communities also partake in feuding, such as British Turks, Turkish and British Kurds, Kurdish communities.

* Between rival Galician mafia, crime families in Galicia, Spain

* Between so-called ''woonwagenbewoners'' (ethnic Dutch people who live in mobile homes) in the Netherlands

* Among Kurdish people, Kurdish and Turkish people, Turkish clans in Turkey (as well as between Kurdish clans in Iraq and Iran)

* Between Turkish Cypriots

* Between rival clans in northern Albania and Kosovo

* Between Aboriginal peoples in Canada, Canadian Aboriginal tribes

* Among Pashtuns in Afghanistan

* Among tribes of Montenegro

*Among the Bosniaks of Sandžak, although to lesser extent in the present-day.

* Among Somali clans

* Among the Berber people, Berbers of Algeria and Morocco

* Between Yoruba people, Yoruba and Igbo people, Igbo clans over land in Nigeria

* Between clans in India and between rival tribes in the north-east Indian state of Assam

* Among Sikh clans in Punjab, India, Punjab

*Rayalaseema of Andhra Pradesh in India

* Between Mirpur, Azad Kashmir, Mirpuri clans in Azad Kashmir (as well as between British Pakistanis of Mirpuri descent in England)

* Among rival clans in China, and especially in Fujian and Guangdong provinces

* In the Philippines (especially in Mindanao between Muslim Moro people, Moro and Christian Cebuano people, Cebuano clans)

* Between Burakumin clans in Japan

* In the lawless Va people, Wa territories of northern Burma

* Among the Arab Bedouins and other Arab tribes inhabiting the mountains of Yemen

* Between Shiites and Sunnis in Iraq

* Among Palestinian people, Palestinian clans in Gaza City, Gaza

* Between Maronite clans, and between Shiites and Sunnis, in Lebanon

* Between Mhallami clans in Lebanon

* In northwest and southern Ethiopia

* Among the highland tribes of New Guinea

* In Svaneti, in Georgia (country), Georgia (especially between Svan people, Svan clans)

* In the mountainous areas of Dagestan

* Between Kyrgyz people, Kyrgyz and Uzbek people, Uzbek clans

* Between Yazidi clans in Armenia and Azerbaijan

* In republics of the northern Caucasus, such as Chechnya and Ingushetia

* Among Chechen people, Chechen teips where those seeking retribution do not accept or respect the local law enforcement authority

Blood feuds within Russian people, Russian communities do exist (mostly related to criminal gangs), but are neither as common nor as pervasive as they are in the Caucasus. In the United States, gang warfare also often takes the form of blood feuds. African-Americans, African-American, Italian-American Mafia, Italian-American, Khmer people, Cambodian, Cuban people, Cuban Marielito, Dominican people (Dominican Republic), Dominican, Guatemalan people, Guatemalan, Haitian people, Haitian, Hmong people, Hmong, Sino-Vietnamese Hoa people, Hoa, Irish Mob, Irish-American, Jamaican people, Jamaican, Korean people, Korean, Lao people, Laotian, Puerto Rican people, Puerto Rican, Salvadorans, Salvadoran and Vietnamese people, Vietnamese gangs and organized crime conflicts very often have taken the form of blood feuds, in which a family member in the gang is killed and a relative takes revenge by killing the murderer as well as other members of the rival gang. This can also be observed in particular cases in conflicts among Colombian, Mexicans, Mexican, Brazilians, Brazilian, and other Latin American gangs, drug cartels, and paramilitary groups; in turf wars among Cape Coloureds, Cape Coloured gangs in South Africa; in gang fights among Dutch Antilleans, Dutch Antillean, Surinamese people, Surinamese and Moluccans, Moluccan gangs in the Netherlands; and in criminal feuds between Scottish people, Scottish, White British, Black British, Black and Mixed British gangs in the UK. This has resulted in gun violence and murders in cities like Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles, Miami, Ciudad Juarez, Medellin, Rio de Janeiro, Cape Town, Amsterdam, London, Liverpool, and Glasgow, to name just a few.

Blood feuds also have a long history within the White Southerners, White Southerner population (and in particular among the Scots-Irish American, "Scots-Irish" or Ulster Scots American population) of the Southern United States, where it is called the "Culture of honor (Southern United States), culture of honor", and still exists to the present day.

Albania

In Albania, ''gjakmarrja'' (blood feuding) is a tradition. Blood feuds in Albania trace back to the Kanun (Albania), Kanun, this custom is also practiced among the Albanians of Kosovo. It returned to rural areas after more than 40 years of being abolished by Albanian Communists led by Enver Hoxha.

In 1980, Albanian author Ismail Kadare published ''Broken April'', about the centuries-old tradition of hospitality, blood feuds, and revenge killing in the highlands of north Albania in the 1930s. ''The New York Times'', reviewing it, wrote: "''Broken April'' is written with masterly simplicity in a bardic style, as if the author is saying: Sit quietly and let me recite a terrible story about a blood feud and the inevitability of death by gunfire in my country. You know it must happen because that is the way life is lived in these mountains. Insults must be avenged; family honor must be upheld...." The novel was made into a 2001 movie entitled ''Behind the Sun (film), Behind the Sun'' by filmmaker Walter Salles, set in 1910 Brazil and starring Rodrigo Santoro, which was nominated for a BAFTA Award for Best Film Not in the English Language and a Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Language Film.

There are now more than 1,600 families who live under an ever-present death sentence because of feuds, and since 1992, at least 10,000 Albanians have been killed in them.

In Albania, ''gjakmarrja'' (blood feuding) is a tradition. Blood feuds in Albania trace back to the Kanun (Albania), Kanun, this custom is also practiced among the Albanians of Kosovo. It returned to rural areas after more than 40 years of being abolished by Albanian Communists led by Enver Hoxha.

In 1980, Albanian author Ismail Kadare published ''Broken April'', about the centuries-old tradition of hospitality, blood feuds, and revenge killing in the highlands of north Albania in the 1930s. ''The New York Times'', reviewing it, wrote: "''Broken April'' is written with masterly simplicity in a bardic style, as if the author is saying: Sit quietly and let me recite a terrible story about a blood feud and the inevitability of death by gunfire in my country. You know it must happen because that is the way life is lived in these mountains. Insults must be avenged; family honor must be upheld...." The novel was made into a 2001 movie entitled ''Behind the Sun (film), Behind the Sun'' by filmmaker Walter Salles, set in 1910 Brazil and starring Rodrigo Santoro, which was nominated for a BAFTA Award for Best Film Not in the English Language and a Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Language Film.

There are now more than 1,600 families who live under an ever-present death sentence because of feuds, and since 1992, at least 10,000 Albanians have been killed in them.Kosovo

Blood feuds have also been part of a centuries-old tradition in Kosovo, tracing back to the Kanun (Albania), Kanun, a 15th-century codification of Albanian customary rules. In the early 1990s, most cases of blood feuds were reconciled in the course of a large-scale reconciliation movement to end blood feuds led by Anton Çetta. The largest reconciliation gathering took place at Verrat e Llukës on 1 May 1990, which had between 100,000 and 500,000 participants. By 1992, the reconciliation campaign ended at least 1,200 deadly blood feuds, and in 1993, not a single homicide occurred in Kosovo.Republic of Ireland

Criminal gang feuds also exist in Dublin, Ireland and in the Republic's third-largest city, Limerick. Irish Travellers, Traveller feuds are also common in towns across the country. Feuds can be due to personal issues, money, or disrespect, and grudges can last generations. Since 2001, over 300 people have been killed in feuds between different drugs gangs, dissident republicans, and Irish Travellers, Traveller families.Philippines

Family and clan feuds, known locally as ''rido'', are characterized by sporadic outbursts of retaliatory violence between families and kinship groups, as well as between communities. It can occur in areas where the government or a central authority is weak, as well as in areas where there is a perceived lack of justice and security. ''Rido'' is a Maranao language, Maranao term commonly used in Mindanao to refer to clan feuds. It is considered one of the major problems in Mindanao because, apart from numerous casualties, ''rido'' has caused destruction of property, crippled local economies, and displaced families. Located in the southern Philippines, Mindanao is home to a majority of the country’s Muslim community, and includes the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao. Mindanao "is a region suffering from poor infrastructure, high poverty, and violence that has claimed the lives of more than 120,000 in the last three decades." There is a widely held stereotype that the violence is perpetrated by armed groups that resort to terrorism to further their political goals, but the actual situation is far more complex. While the Muslim-Christian conflict and the state-rebel conflicts dominate popular perceptions and media attention, a survey commissioned by The Asia Foundation in 2002—and further verified by a recent Social Weather Stations survey—revealed that citizens are more concerned about the prevalence of ''rido'' and its negative impact on their communities than the conflict between the state and rebel groups. The unfortunate interaction and subsequent confusion of ''rido''-based violence with secessionism, communist insurgency, banditry, military involvement and other forms of armed violence shows that violence in Mindanao is more complicated than what is commonly believed. ''Rido'' has wider implications for conflict in Mindanao, primarily because it tends to interact in unfortunate ways with separatist conflict and other forms of armed violence. Many armed confrontations in the past involving insurgent groups and the military were triggered by a local ''rido''. The studies cited above investigated the dynamics of ''rido'' with the intention of helping design strategic interventions to address such conflicts.=Causes

= The causes of ''rido'' are varied and may be further complicated by a society's concept of Face (sociological concept), honor and shame, an integral aspect of the social rules that determine accepted practices in the affected communities. The triggers for conflicts range from petty offenses, such as theft and jesting, to more serious crimes, like homicide. These are further aggravated by land disputes and political rivalries, the most common causes of ''rido''. Proliferation of firearms, lack of law enforcement and credible mediators in conflict-prone areas, and an inefficient justice system further contribute to instances of ''rido''.=Statistics

= Studies on ''rido'' have documented a total of 1,266 ''rido'' cases between the 1930s and 2005, which have killed over 5,500 people and displaced thousands. The four provinces with the highest numbers of ''rido'' incidences are: Lanao del Sur (377), Maguindanao (218), Lanao del Norte (164), and Sulu Province, Sulu (145). Incidences in these four provinces account for 71% of the total documented cases. The findings also show a steady rise in ''rido'' conflicts in the eleven provinces surveyed from the 1980s to 2004. According to the studies, during 2002–2004, 50% (637 cases) of total ''rido'' incidences occurred, equaling about 127 new ''rido'' cases per year. Out of the total number of ''rido'' cases documented, 64% remain unresolved.= Resolution

= ''Rido'' conflicts are either resolved, unresolved, or reoccurring. Although the majority of these cases remain unresolved, there have been many resolutions through different conflict-resolving bodies and mechanisms. These cases can utilize the formal procedures of the Philippine government or the various indigenous systems. Formal methods may involve official courts, local government officials, police, and the military. Indigenous methods to resolve conflicts usually involve elder leaders who use local knowledge, beliefs, and practices, as well as their own personal influence, to help repair and restore damaged relationships. Some cases using this approach involve the payment of blood money (term), blood money to resolve the conflict. Hybrid mechanisms include the collaboration of government, religious, and traditional leaders in resolving conflicts through the formation of collaborative groups. Furthermore, the institutionalization of traditional conflict resolution processes into laws and ordinances has been successful with the hybrid method approach. Other conflict-resolution methods include the establishment of ceasefires and the intervention of youth organizations.Well-known blood feuds

*Three Kingdoms period, feuding warlords during the fall of the Han Dynasty (184–280 AD; China)

*Njál's saga, an Icelandic account of a Norsemen, Norse blood feud (960–1020; Iceland, Ireland and Norway)

* (975/977–980) in Kyivan Rus'

*The Clan Mackintosh, Mackintosh-Clan Cameron, Cameron Stand-off at the Fords of Arkaig, feud (1290s–1665; Scotland)

*The Battle of the North Inch; the battle is fictionalised in the novel ''The Fair Maid of Perth'' by Sir Walter Scott (Michaelmas 1396; Scotland)

*The Krummedige-Tre Rosor feud (1448–1502; Norway)

*The Bonville–Courtenay feud (1450s; England)

*The Percy–Neville feud (1450s; England)

*The Wars of the Roses (1455–1487; England)

*The Viscount Lisle, Talbot–Baron Berkeley, Berkeley feud (1455–1485 England) (concurrent with the Wars of the Roses)

*The Clan Gunn, Gunn–Clan Keith, Keith feud (1464–1978; Scotland)

*The Clan Campbell, Campbell–Clan MacDonald, MacDonald feud, including the Massacre of Glencoe (1692; Scotland)

*The Clan Forbes–Clan Gordon feud, (1500s–1571; Scotland)

*The Clan Forbes–Clan Leslie feud, (1520s–1530s; Scotland)

*The Clan Forbes–City of Aberdeen feud, (1529–1539; Scotland)

*The Regulator-Moderator War, (1839–1844; Republic of Texas)

*The Punti–Hakka Clan Wars, (1855–1868; Guangdong, China)

*The Black Donnellys#The feud, Donnelly–Biddulph community feud (1857–1880; Ontario, Canada)

*The Lincoln County War (1878–1881; New Mexico, United States)

*The Lincoln County Feud (1878–1890; West Virginia, United States)

*The Hatfield-McCoy feud (1878–1891; West Virginia & Kentucky, United States)

*The Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, Clanton/McLaury–Earp feud (see also Earp Vendetta Ride), also known as the "Gunfight at the O.K. Corral" (1881; Arizona, United States)

*The Pleasant Valley War, also known as the "Tonto Basin Feud" (1882–1892; Arizona, United States)

*The Al Capone, Capone–Bugs Moran, Moran feud, including the St. Valentine's Day massacre (1925–1930; Chicago, Illinois, United States)

*The Castellammarese War (1929–1931; New York City, New York United States)

*The Cohen crime family, Battle of the Sunset Strip (1947–1951; Los Angeles, California United States)

*The First Colombo crime family, Colombo Family War (1960–1963; New York City, United States)

*The Second Colombo Family War (1971–1975; New York City, United States)

*The Philadelphia crime family, Riccobene War (1982–1984; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States)

*The Internal Patriarca crime family, Patriarca War (1991–1996; Boston, Massachusetts, United States)

*Second Mafia War, Great Mafia War (1981–1983; Sicily, Italy)

*The Feud of Scampia (2004–2005; Naples, Italy)

*The Maguindanao Massacre (2009; Ampatuan, Maguindanao, Ampatuan, Philippines)

*The Limerick feud (2000–present; Limerick, Ireland)

*The Rizzuto crime family, Montreal Mafia War (2009–present; mostly the Canada, Canadian provinces of Quebec and Ontario)

*Three Kingdoms period, feuding warlords during the fall of the Han Dynasty (184–280 AD; China)

*Njál's saga, an Icelandic account of a Norsemen, Norse blood feud (960–1020; Iceland, Ireland and Norway)

* (975/977–980) in Kyivan Rus'

*The Clan Mackintosh, Mackintosh-Clan Cameron, Cameron Stand-off at the Fords of Arkaig, feud (1290s–1665; Scotland)

*The Battle of the North Inch; the battle is fictionalised in the novel ''The Fair Maid of Perth'' by Sir Walter Scott (Michaelmas 1396; Scotland)

*The Krummedige-Tre Rosor feud (1448–1502; Norway)

*The Bonville–Courtenay feud (1450s; England)

*The Percy–Neville feud (1450s; England)

*The Wars of the Roses (1455–1487; England)

*The Viscount Lisle, Talbot–Baron Berkeley, Berkeley feud (1455–1485 England) (concurrent with the Wars of the Roses)

*The Clan Gunn, Gunn–Clan Keith, Keith feud (1464–1978; Scotland)

*The Clan Campbell, Campbell–Clan MacDonald, MacDonald feud, including the Massacre of Glencoe (1692; Scotland)

*The Clan Forbes–Clan Gordon feud, (1500s–1571; Scotland)

*The Clan Forbes–Clan Leslie feud, (1520s–1530s; Scotland)

*The Clan Forbes–City of Aberdeen feud, (1529–1539; Scotland)

*The Regulator-Moderator War, (1839–1844; Republic of Texas)

*The Punti–Hakka Clan Wars, (1855–1868; Guangdong, China)

*The Black Donnellys#The feud, Donnelly–Biddulph community feud (1857–1880; Ontario, Canada)

*The Lincoln County War (1878–1881; New Mexico, United States)

*The Lincoln County Feud (1878–1890; West Virginia, United States)

*The Hatfield-McCoy feud (1878–1891; West Virginia & Kentucky, United States)

*The Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, Clanton/McLaury–Earp feud (see also Earp Vendetta Ride), also known as the "Gunfight at the O.K. Corral" (1881; Arizona, United States)

*The Pleasant Valley War, also known as the "Tonto Basin Feud" (1882–1892; Arizona, United States)

*The Al Capone, Capone–Bugs Moran, Moran feud, including the St. Valentine's Day massacre (1925–1930; Chicago, Illinois, United States)

*The Castellammarese War (1929–1931; New York City, New York United States)

*The Cohen crime family, Battle of the Sunset Strip (1947–1951; Los Angeles, California United States)

*The First Colombo crime family, Colombo Family War (1960–1963; New York City, United States)

*The Second Colombo Family War (1971–1975; New York City, United States)

*The Philadelphia crime family, Riccobene War (1982–1984; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States)

*The Internal Patriarca crime family, Patriarca War (1991–1996; Boston, Massachusetts, United States)

*Second Mafia War, Great Mafia War (1981–1983; Sicily, Italy)

*The Feud of Scampia (2004–2005; Naples, Italy)

*The Maguindanao Massacre (2009; Ampatuan, Maguindanao, Ampatuan, Philippines)

*The Limerick feud (2000–present; Limerick, Ireland)

*The Rizzuto crime family, Montreal Mafia War (2009–present; mostly the Canada, Canadian provinces of Quebec and Ontario)

See also

*Dassler brothers feud *Bedouin systems of justice#Blood feud protocols, Bedouin blood feud *Blood Law *Communal conflicts in Nigeria *Endemic warfare *Ethnic violence in South Sudan *Feud (professional wrestling) *Frontier justice *Gjakmarrja *Kin punishment *List of feuds in the United States *Mobbing *Punti–Hakka Clan Wars *San Luca feud *Sippenhaft *Sudanese nomadic conflicts *WarriorNotes

Further reading

* Grutzpalk, Jonas. "Blood Feud and Modernity. Max Weber's and Émile Durkheim's Theory." ''Journal of Classical Sociology'' 2 (2002); p. 115–134. *Hyams, Paul. 2003. ''Rancor and Reconciliation in Medieval England''. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. * Kreuzer, Peter. 2005. "Political Clans and Violence in the Southern Philippines." Frankfurt: Peace Research Institute Frankfurt* Miller, William Ian. 1990. ''Bloodtaking and peacemaking : feud, law, and society in Saga Iceland''. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. * Torres, Wilfredo M. (ed). 2007. ''Rido: Clan Feuding and Conflict Management in Mindanao''. Makati: The Asia Foundation

* Torres, Wilfredo M. 2010. "Letting A Thousand Flowers Bloom: Clan Conflicts and their Management." ''Challenges to Human Security in Complex Situations: The Case of Conflict in the Southern Philippines''. Kuala Lumpur: Asian Disaster Reduction and Response Network (ADRRN)

* Boehm, Christopher. 1984. ''Blood Revenge: The Anthropology of Feuding in Montenegro and Other Tribal Societies''. Lawrence, Kansas, Lawrence: University of Kansas

at Google Books

External links

BBC: "In pictures: Egypt vendetta ends"

May, 2005. "One of the most enduring and bloody family feuds of modern times in Upper Egypt has ended with a tense ceremony of humiliation and forgiveness. [...] Police are edgy. After lengthy peace talks, no one knows if the penance — and a large payment of blood money — will end the vendetta which began in 1991 with a children's fight."

15 clan feuds settled in Lanao; rido tops cause of evacuation more than war

from the MindaNews website. Posted on 13 July 2007.

2 clans in Matanog settle rido, sign peace pact

from the MindaNews website. Posted on 30 January 2008.

Albania: Feuding families…bitter lives

Children as teacher-facilitators for peace

from the Inquirer website. Posted on 29 September 2007.

from the blog of Datu Jamal Ashley Yahya Abbas, originally in "Reflections on the Bangsa Moro." Posted on 1 May 2007.

Mexico drugs cartels feud erupts

*

Rido

', from The Asia Foundation's ''Rido'' Map website.

''Rido'' and its Influence on the Academe, NGOs and the Military

an essay from the website of the Balay Mindanaw Foundation, Inc. Posted on 28 February 2007.

'Rido' seen [as] major Mindanao security concern

from the Inquirer website. Posted on 18 November 2006.

Villages in "rido" area return home

from the MindaNews website. Posted on 1 November 2007.

*[http://www.stippy.com/japan-news-and-media/a-yakuza-war-has-started-in-central-tokyo/ A "Yakuza War" has started in Central Tokyo] {{Authority control Feuds, Gangland warfare tactics Revenge Violence Violent crime Interpersonal conflict