Richard III on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Richard III (2 October 145222 August 1485) was King of England and

Richard spent several years during his childhood at

Richard spent several years during his childhood at

Following a decisive Yorkist victory over the Lancastrians at the Battle of Tewkesbury, Richard married Anne Neville on 12 July 1472. Anne had previously been wedded to Edward of Westminster, only son of Henry VI, to seal her father's allegiance to the Lancastrian party, Edward died at the Battle of Tewkesbury on 4 May 1471, while Warwick had died at the Battle of Barnet on 14 April 1471. Richard's marriage plans brought him into conflict with his brother George. John Paston's letter of 17 February 1472 makes it clear that George was not happy about the marriage but grudgingly accepted it on the basis that "he may well have my Lady his sister-in-law, but they shall part no livelihood". The reason was the inheritance Anne shared with her elder sister Isabel, whom George had married in 1469. It was not only the earldom that was at stake; Richard Neville had inherited it as a result of his marriage to

Following a decisive Yorkist victory over the Lancastrians at the Battle of Tewkesbury, Richard married Anne Neville on 12 July 1472. Anne had previously been wedded to Edward of Westminster, only son of Henry VI, to seal her father's allegiance to the Lancastrian party, Edward died at the Battle of Tewkesbury on 4 May 1471, while Warwick had died at the Battle of Barnet on 14 April 1471. Richard's marriage plans brought him into conflict with his brother George. John Paston's letter of 17 February 1472 makes it clear that George was not happy about the marriage but grudgingly accepted it on the basis that "he may well have my Lady his sister-in-law, but they shall part no livelihood". The reason was the inheritance Anne shared with her elder sister Isabel, whom George had married in 1469. It was not only the earldom that was at stake; Richard Neville had inherited it as a result of his marriage to  The requisite papal dispensation was obtained dated 22 April 1472. Michael Hicks has suggested that the terms of the dispensation deliberately understated the degrees of consanguinity between the couple, and the marriage was therefore illegal on the ground of first degree consanguinity following George's marriage to Anne's sister Isabel. There would have been first-degree consanguinity if Richard had sought to marry Isabel (in case of widowhood) after she had married his brother George, but no such consanguinity applied for Anne and Richard. Richard's marriage to Anne was never declared null, and it was public to everyone including secular and canon lawyers for 13 years.

In June 1473, Richard persuaded his mother-in-law to leave the sanctuary and come to live under his protection at Middleham. Later in the year, under the terms of the 1473 Act of Resumption, George lost some of the property he held under royal grant and made no secret of his displeasure. John Paston's letter of November 1473 says that King Edward planned to put both his younger brothers in their place by acting as "a stifler atween them". Early in 1474, Parliament assembled and Edward attempted to reconcile his brothers by stating that both men, and their wives, would enjoy the Warwick inheritance just as if the Countess of Warwick "was naturally dead". The doubts cast by George on the validity of Richard and Anne's marriage were addressed by a clause protecting their rights in the event they were divorced (i.e. of their marriage being declared null and void by the Church) and then legally remarried to each other, and also protected Richard's rights while waiting for such a valid second marriage with Anne. The following year, Richard was rewarded with all the Neville lands in the north of England, at the expense of Anne's cousin, George Neville, 1st Duke of Bedford. From this point, George seems to have fallen steadily out of King Edward's favour, his discontent coming to a head in 1477 when, following Isabel's death, he was denied the opportunity to marry Mary of Burgundy, the stepdaughter of his sister Margaret, even though Margaret approved the proposed match. There is no evidence of Richard's involvement in George's subsequent conviction and execution on a charge of treason.

The requisite papal dispensation was obtained dated 22 April 1472. Michael Hicks has suggested that the terms of the dispensation deliberately understated the degrees of consanguinity between the couple, and the marriage was therefore illegal on the ground of first degree consanguinity following George's marriage to Anne's sister Isabel. There would have been first-degree consanguinity if Richard had sought to marry Isabel (in case of widowhood) after she had married his brother George, but no such consanguinity applied for Anne and Richard. Richard's marriage to Anne was never declared null, and it was public to everyone including secular and canon lawyers for 13 years.

In June 1473, Richard persuaded his mother-in-law to leave the sanctuary and come to live under his protection at Middleham. Later in the year, under the terms of the 1473 Act of Resumption, George lost some of the property he held under royal grant and made no secret of his displeasure. John Paston's letter of November 1473 says that King Edward planned to put both his younger brothers in their place by acting as "a stifler atween them". Early in 1474, Parliament assembled and Edward attempted to reconcile his brothers by stating that both men, and their wives, would enjoy the Warwick inheritance just as if the Countess of Warwick "was naturally dead". The doubts cast by George on the validity of Richard and Anne's marriage were addressed by a clause protecting their rights in the event they were divorced (i.e. of their marriage being declared null and void by the Church) and then legally remarried to each other, and also protected Richard's rights while waiting for such a valid second marriage with Anne. The following year, Richard was rewarded with all the Neville lands in the north of England, at the expense of Anne's cousin, George Neville, 1st Duke of Bedford. From this point, George seems to have fallen steadily out of King Edward's favour, his discontent coming to a head in 1477 when, following Isabel's death, he was denied the opportunity to marry Mary of Burgundy, the stepdaughter of his sister Margaret, even though Margaret approved the proposed match. There is no evidence of Richard's involvement in George's subsequent conviction and execution on a charge of treason.

Bishop Robert Stillington, the Bishop of Bath and Wells, is said to have informed Richard that Edward IV's marriage to Elizabeth Woodville was invalid because of Edward's earlier union with Eleanor Butler, making Edward V and his siblings illegitimate. The identity of Stillington was known only through the memoirs of French diplomat Philippe de Commines. On 22 June, a sermon was preached outside

Bishop Robert Stillington, the Bishop of Bath and Wells, is said to have informed Richard that Edward IV's marriage to Elizabeth Woodville was invalid because of Edward's earlier union with Eleanor Butler, making Edward V and his siblings illegitimate. The identity of Stillington was known only through the memoirs of French diplomat Philippe de Commines. On 22 June, a sermon was preached outside

On 22 August 1485, Richard met the outnumbered forces of Henry Tudor at the

On 22 August 1485, Richard met the outnumbered forces of Henry Tudor at the  All accounts note that King Richard fought bravely and ably during this manoeuvre, unhorsing Sir John Cheyne, a well-known jousting champion, killing Henry's standard bearer Sir William Brandon and coming within a sword's length of Henry Tudor before being surrounded by Sir William Stanley's men and killed.

All accounts note that King Richard fought bravely and ably during this manoeuvre, unhorsing Sir John Cheyne, a well-known jousting champion, killing Henry's standard bearer Sir William Brandon and coming within a sword's length of Henry Tudor before being surrounded by Sir William Stanley's men and killed.

There are numerous contemporary, or near-contemporary, sources of information about the reign of Richard III. These include the ''Croyland Chronicle'', Commines' ''Mémoires'', the report of Dominic Mancini, the Paston Letters, the Chronicles of Robert Fabyan and numerous court and official records, including a few letters by Richard himself. However, the debate about Richard's true character and motives continues, both because of the subjectivity of many of the written sources, reflecting the generally partisan nature of writers of this period, and because none was written by men with an intimate knowledge of Richard.

During Richard's reign, the historian

There are numerous contemporary, or near-contemporary, sources of information about the reign of Richard III. These include the ''Croyland Chronicle'', Commines' ''Mémoires'', the report of Dominic Mancini, the Paston Letters, the Chronicles of Robert Fabyan and numerous court and official records, including a few letters by Richard himself. However, the debate about Richard's true character and motives continues, both because of the subjectivity of many of the written sources, reflecting the generally partisan nature of writers of this period, and because none was written by men with an intimate knowledge of Richard.

During Richard's reign, the historian  Richard's reputation as a promoter of legal fairness persisted, however.

Richard's reputation as a promoter of legal fairness persisted, however.

Richard III is the protagonist of '' Richard III'', one of

Richard III is the protagonist of '' Richard III'', one of

The diggers found Greyfriars Church by 5 September 2012 and two days later announced that they had found Robert Herrick's garden, where the memorial to Richard III stood in the early 17th century. A human skeleton was found beneath the Church's

The diggers found Greyfriars Church by 5 September 2012 and two days later announced that they had found Robert Herrick's garden, where the memorial to Richard III stood in the early 17th century. A human skeleton was found beneath the Church's  On 12 September, it was announced that the skeleton discovered during the search might be that of Richard III. Several reasons were given: the body was of an adult male; it was buried beneath the choir of the church; and there was severe

On 12 September, it was announced that the skeleton discovered during the search might be that of Richard III. Several reasons were given: the body was of an adult male; it was buried beneath the choir of the church; and there was severe

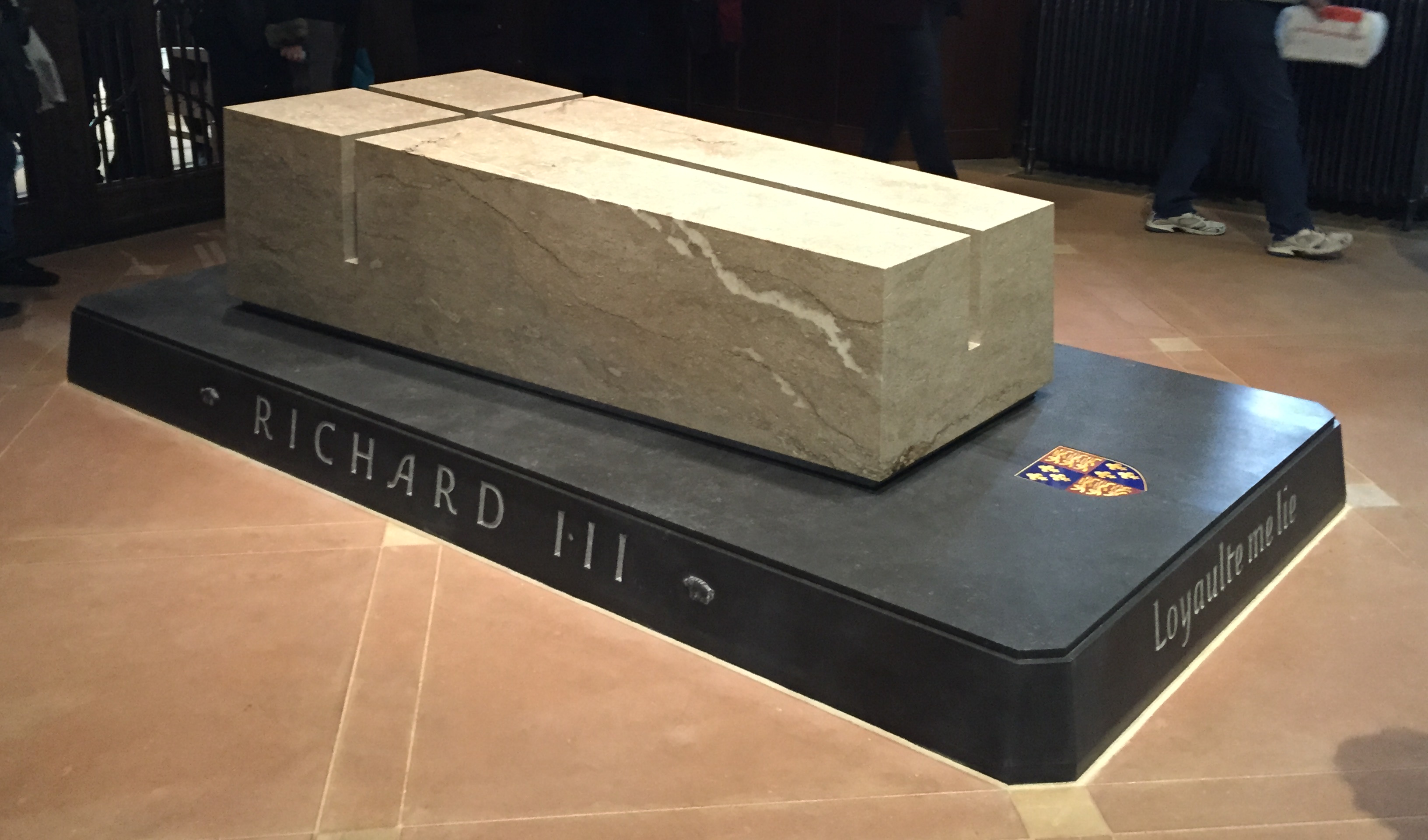

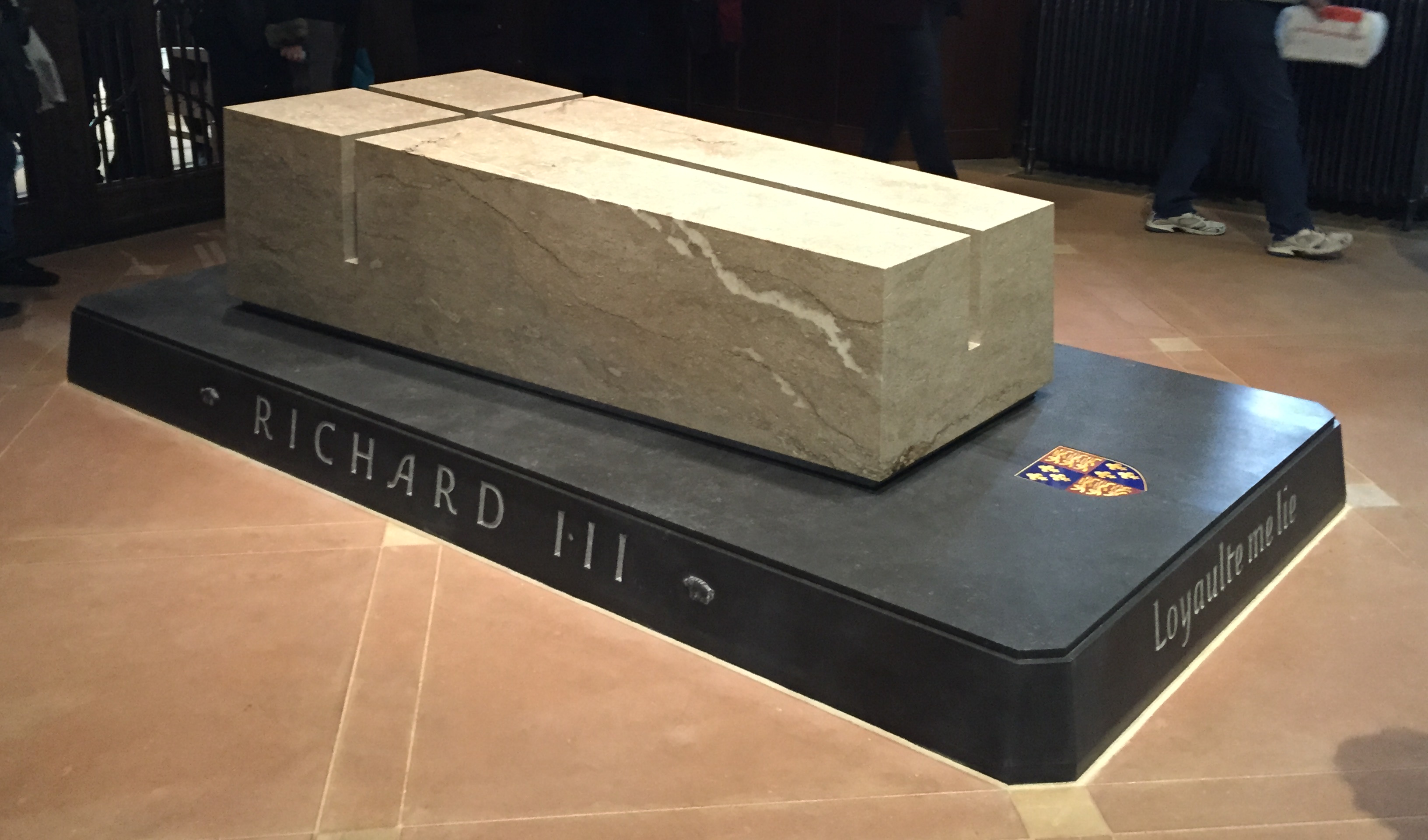

After his death in battle in 1485, Richard III's body was buried in Greyfriars Church in Leicester. Following the discoveries of Richard's remains in 2012, it was decided that they should be reburied at Leicester Cathedral, despite feelings in some quarters that he should have been reburied in York Minster. Those who challenged the decision included fifteen "collateral on-directdescendants of Richard III", represented by the Plantagenet Alliance, who believed that the body should be reburied in York, as they claim the king wished. In August 2013, they filed a court case in order to contest Leicester's claim to re-inter the body within its cathedral, and propose the body be buried in York instead. However, Michael Ibsen, who gave the DNA sample that identified the king, gave his support to Leicester's claim to re-inter the body in their cathedral. On 20 August, a judge ruled that the opponents had the legal standing to contest his burial in Leicester Cathedral, despite a clause in the contract which had authorized the excavations requiring his burial there. He urged the parties, though, to settle out of court in order to "avoid embarking on the Wars of the Roses, Part Two".013WHCB13(Admin)"/> The Plantagenet Alliance, and the supporting fifteen collateral descendants, also faced the challenge that "Basic maths shows Richard, who had no surviving children but five siblings, could have millions of 'collateral' descendants" undermining the group's claim to represent "the only people who can speak on behalf of him". A ruling in May 2014 decreed that there are "no public law grounds for the Court interfering with the decisions in question".014WHC1662(QB)"/> The remains were taken to Leicester Cathedral on 22 March 2015 and reinterred on 26 March.

His remains were carried in procession to the cathedral on 22 March 2015, and reburied on 26 March 2015 at a religious re-burial service at which both Tim Stevens, the Bishop of Leicester, and

After his death in battle in 1485, Richard III's body was buried in Greyfriars Church in Leicester. Following the discoveries of Richard's remains in 2012, it was decided that they should be reburied at Leicester Cathedral, despite feelings in some quarters that he should have been reburied in York Minster. Those who challenged the decision included fifteen "collateral on-directdescendants of Richard III", represented by the Plantagenet Alliance, who believed that the body should be reburied in York, as they claim the king wished. In August 2013, they filed a court case in order to contest Leicester's claim to re-inter the body within its cathedral, and propose the body be buried in York instead. However, Michael Ibsen, who gave the DNA sample that identified the king, gave his support to Leicester's claim to re-inter the body in their cathedral. On 20 August, a judge ruled that the opponents had the legal standing to contest his burial in Leicester Cathedral, despite a clause in the contract which had authorized the excavations requiring his burial there. He urged the parties, though, to settle out of court in order to "avoid embarking on the Wars of the Roses, Part Two".013WHCB13(Admin)"/> The Plantagenet Alliance, and the supporting fifteen collateral descendants, also faced the challenge that "Basic maths shows Richard, who had no surviving children but five siblings, could have millions of 'collateral' descendants" undermining the group's claim to represent "the only people who can speak on behalf of him". A ruling in May 2014 decreed that there are "no public law grounds for the Court interfering with the decisions in question".014WHC1662(QB)"/> The remains were taken to Leicester Cathedral on 22 March 2015 and reinterred on 26 March.

His remains were carried in procession to the cathedral on 22 March 2015, and reburied on 26 March 2015 at a religious re-burial service at which both Tim Stevens, the Bishop of Leicester, and

Archived

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

King Richard III Visitor Centre

Leicester

The Richard III Society website

The Richard III Society, American Branch website

Information about the discovery of Richard III

from the

Lord of Ireland

The Lordship of Ireland ( ga, Tiarnas na hÉireann), sometimes referred to retroactively as Norman Ireland, was the part of Ireland ruled by the King of England (styled as "Lord of Ireland") and controlled by loyal Anglo-Norman lords between ...

from 26 June 1483 until his death in 1485. He was the last king of the House of York

The House of York was a cadet branch of the English royal House of Plantagenet. Three of its members became kings of England in the late 15th century. The House of York descended in the male line from Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of Yor ...

and the last of the Plantagenet dynasty. His defeat and death at the Battle of Bosworth Field

The Battle of Bosworth or Bosworth Field was the last significant battle of the Wars of the Roses, the civil war between the houses of Lancaster and York that extended across England in the latter half of the 15th century. Fought on 22 Augu ...

, the last decisive battle of the Wars of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses (1455–1487), known at the time and for more than a century after as the Civil Wars, were a series of civil wars fought over control of the throne of England, English throne in the mid-to-late fifteenth century. These w ...

, marked the end of the Middle Ages in England

England in the Middle Ages concerns the history of England during the medieval period, from the end of the 5th century through to the start of the Early Modern period in 1485. When England emerged from the collapse of the Roman Empire, the econ ...

.

Richard was created Duke of Gloucester in 1461 after the accession of his brother King Edward IV

Edward IV (28 April 1442 – 9 April 1483) was King of England from 4 March 1461 to 3 October 1470, then again from 11 April 1471 until his death in 1483. He was a central figure in the Wars of the Roses, a series of civil wars in Englan ...

. In 1472, he married Anne Neville

Anne Neville (11 June 1456 – 16 March 1485) was Queen of England as the wife of King Richard III. She was the younger of the two daughters and co-heiresses of Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick (the "Kingmaker"). Before her marriage to Ri ...

, daughter of Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick. He governed northern England during Edward's reign, and played a role in the invasion of Scotland in 1482. When Edward IV died in April 1483, Richard was named Lord Protector

Lord Protector (plural: ''Lords Protector'') was a title that has been used in British constitutional law for the head of state. It was also a particular title for the British heads of state in respect to the established church. It was sometimes ...

of the realm for Edward's eldest son and successor, the 12-year-old Edward V

Edward V (2 November 1470 – mid-1483)R. F. Walker, "Princes in the Tower", in S. H. Steinberg et al, ''A New Dictionary of British History'', St. Martin's Press, New York, 1963, p. 286. was ''de jure'' King of England and Lord of Ireland fr ...

. Arrangements were made for Edward V's coronation on 22 June 1483. Before the king could be crowned, the marriage of his parents was declared bigamous and therefore invalid. Now officially illegitimate, their children were barred from inheriting the throne. On 25 June, an assembly of lords and commoners endorsed a declaration to this effect, and proclaimed Richard as the rightful king. He was crowned on 6 July 1483. Edward and his younger brother Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York, called the " Princes in the Tower", were not seen in public after August, and accusations circulated that they had been murdered on King Richard's orders, after the Tudor dynasty established their rule a few years later.

There were two major rebellions against Richard during his reign. In October 1483, an unsuccessful revolt was led by staunch allies of Edward IV and Richard's former ally, Henry Stafford, 2nd Duke of Buckingham. Then, in August 1485, Henry Tudor and his uncle, Jasper Tudor, landed in southern Wales

South Wales ( cy, De Cymru) is a loosely defined region of Wales bordered by England to the east and mid Wales to the north. Generally considered to include the historic counties of Glamorgan and Monmouthshire, south Wales extends westwards t ...

with a contingent of French troops, and marched through Pembrokeshire

Pembrokeshire ( ; cy, Sir Benfro ) is a county in the south-west of Wales. It is bordered by Carmarthenshire to the east, Ceredigion to the northeast, and the rest by sea. The county is home to Pembrokeshire Coast National Park. The Park oc ...

, recruiting soldiers. Henry's forces defeated Richard's army near the Leicestershire

Leicestershire ( ; postal abbreviation Leics.) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the East Midlands, England. The county borders Nottinghamshire to the north, Lincolnshire to the north-east, Rutland to the east, Northamptonshire ...

town of Market Bosworth. Richard was slain, making him the last English king to die in battle. Henry Tudor then ascended the throne as Henry VII.

Richard's corpse was taken to the nearby town of Leicester

Leicester ( ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, city, Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority and the county town of Leicestershire in the East Midlands of England. It is the largest settlement in the East Midlands.

The city l ...

and buried without ceremony. His original tomb monument is believed to have been removed during the English Reformation

The English Reformation took place in 16th-century England when the Church of England broke away from the authority of the pope and the Catholic Church. These events were part of the wider European Protestant Reformation, a religious and poli ...

, and his remains were wrongly thought to have been thrown into the River Soar

The River Soar () is a major tributary of the River Trent in the English East Midlands and is the principal river of Leicestershire. The source of the river is midway between Hinckley and Lutterworth. The river then flows north through Leices ...

. In 2012, an archaeological excavation was commissioned by the Richard III Society

Ricardians are people interested in altering the posthumous reputation of King Richard III of England (reigned 1483–1485). Richard III has long been portrayed unfavourably, most notably in William Shakespeare's play ''Richard III'', in which R ...

on the site previously occupied by Grey Friars Priory

Greyfriars, Leicester, was a friary of the Order of Friars Minor, commonly known as the Franciscans, established on the west side of Leicester by 1250, and dissolved in 1538. Following dissolution the friary was demolished and the site levelle ...

. The University of Leicester

, mottoeng = So that they may have life

, established =

, type = public research university

, endowment = £20.0 million

, budget = £326 million

, chancellor = David Willetts

, vice_chancellor = Nishan Canagarajah

, head_lab ...

identified the skeleton found in the excavation as that of Richard III as a result of radiocarbon dating

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of radiocarbon, a radioactive isotope of carbon.

The method was de ...

, comparison with contemporary reports of his appearance, identification of trauma sustained at the Battle of Bosworth Field and comparison of his mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA or mDNA) is the DNA located in mitochondria, cellular organelles within eukaryotic cells that convert chemical energy from food into a form that cells can use, such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial D ...

with that of two matrilineal

Matrilineality is the tracing of kinship through the female line. It may also correlate with a social system in which each person is identified with their matriline – their mother's lineage – and which can involve the inheritance ...

descendants of his sister Anne. He was reburied in Leicester Cathedral on 26 March 2015.

Early life

Richard was born on 2 October 1452, at Fotheringhay Castle inNorthamptonshire

Northamptonshire (; abbreviated Northants.) is a county in the East Midlands of England. In 2015, it had a population of 723,000. The county is administered by

two unitary authorities: North Northamptonshire and West Northamptonshire. It ...

, the eleventh of the twelve children of Richard, 3rd Duke of York, and Cecily Neville, and the youngest to survive infancy. His childhood coincided with the beginning of what has traditionally been labelled the 'Wars of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses (1455–1487), known at the time and for more than a century after as the Civil Wars, were a series of civil wars fought over control of the throne of England, English throne in the mid-to-late fifteenth century. These w ...

', a period of political instability and periodic open civil war in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

during the second half of the fifteenth century, between the Yorkists, who supported Richard's father (a potential claimant to the throne of King Henry VI from birth), and opposed the regime of Henry VI and his wife, Margaret of Anjou, and the Lancastrians, who were loyal to the crown. In 1459, his father and the Yorkists were forced to flee England, whereupon Richard and his older brother George were placed in the custody of their aunt Anne Neville, Duchess of Buckingham

Anne Neville (c. 1408 – 20 September 1480) was a daughter of Ralph Neville, 1st Earl of Westmorland, and his second wife Lady Joan Beaufort. Her first husband was Humphrey Stafford, 1st Duke of Buckingham, and she was an important English no ...

, and possibly of Cardinal Thomas Bourchier, Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Just ...

.

When their father and elder brother Edmund, Earl of Rutland

Edmund, Earl of Rutland (17 May 1443 – 30 December 1460) was the fourth child and second surviving son of Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York, and Cecily Neville. He was a younger brother of Edward IV of England, Edward, Earl of March, the ...

, were killed at the Battle of Wakefield

The Battle of Wakefield took place in Sandal Magna near Wakefield in northern England, on 30 December 1460. It was a major battle of the Wars of the Roses. The opposing forces were an army led by nobles loyal to the captive King Henry VI o ...

on 30 December 1460, Richard and George were sent by their mother to the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

. They returned to England following the defeat of the Lancastrians at the Battle of Towton

The Battle of Towton took place on 29 March 1461 during the Wars of the Roses, near Towton in North Yorkshire, and "has the dubious distinction of being probably the largest and bloodiest battle on English soil". Fought for ten hours between a ...

. They participated in the coronation of their eldest brother as King Edward IV

Edward IV (28 April 1442 – 9 April 1483) was King of England from 4 March 1461 to 3 October 1470, then again from 11 April 1471 until his death in 1483. He was a central figure in the Wars of the Roses, a series of civil wars in Englan ...

on 28 June 1461, when Richard was named Duke of Gloucester and made both a Knight of the Garter and a Knight of the Bath. Edward appointed him the sole Commissioner of Array

A commission of array was a commission given by English sovereigns to officers or gentry in a given territory to muster and array the inhabitants and to see them in a condition for war, or to put soldiers of a country in a condition for military ...

for the Western Counties in 1464 when he was 11. By the age of 17, he had an independent command.

Richard spent several years during his childhood at

Richard spent several years during his childhood at Middleham Castle

Middleham Castle is a ruined castle in Middleham in Wensleydale, in the county of North Yorkshire, England. It was built by Robert Fitzrandolph, 3rd Lord of Middleham and Spennithorne, commencing in 1190. The castle was the childhood home of ...

in Wensleydale, Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a Historic counties of England, historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other Eng ...

, under the tutelage of his cousin Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick, later known as 'the Kingmaker' because of his role in the Wars of the Roses. Warwick supervised Richard's training as a knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the Christian denomination, church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood ...

; in the autumn of 1465, Edward IV granted Warwick 1,000 pounds for the expenses of his younger brother's tutelage. With some interruptions, Richard stayed at Middleham either from late 1461 until early 1465, when he was 12 or from 1465 until his coming of age in 1468, when he turned 16. While at Warwick's estate, it is likely that he met both Francis Lovell, who was his firm supporter later in his life, and Warwick's younger daughter, his future wife Anne Neville

Anne Neville (11 June 1456 – 16 March 1485) was Queen of England as the wife of King Richard III. She was the younger of the two daughters and co-heiresses of Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick (the "Kingmaker"). Before her marriage to Ri ...

.

It is possible that even at this early stage Warwick was considering the king's brothers as strategic matches for his daughters, Isabel and Anne: young aristocrats were often sent to be raised in the households of their intended future partners, as had been the case for the young dukes' father, Richard of York. As the relationship between the king and Warwick became strained, Edward IV opposed the match. During Warwick's lifetime, George was the only royal brother to marry one of his daughters, the elder, Isabel, on 12 July 1469, without the king's permission. George joined his father-in-law's revolt against the king, while Richard remained loyal to Edward, even though he was rumoured to have been sleeping with Anne.

Richard and Edward were forced to flee to Burgundy in October 1470 after Warwick defected to the side of the former Lancastrian queen Margaret of Anjou. In 1468, Richard's sister Margaret had married Charles the Bold, the Duke of Burgundy, and the brothers could expect a welcome there. Edward was restored to the throne in the spring of 1471, following the battles of Barnet and Tewkesbury

Tewkesbury ( ) is a medieval market town and civil parish in the north of Gloucestershire, England. The town has significant history in the Wars of the Roses and grew since the building of Tewkesbury Abbey. It stands at the confluence of the Ri ...

, in both of which the 18-year-old Richard played a crucial role.

During his adolescence, and due to a cause that is unknown, Richard developed a sideways curvature of the spine (Scoliosis

Scoliosis is a condition in which a person's spine has a sideways curve. The curve is usually "S"- or "C"-shaped over three dimensions. In some, the degree of curve is stable, while in others, it increases over time. Mild scoliosis does not ty ...

). In 2014, after the discovery of Richard's remains, the osteoarchaeologist Dr. Jo Appleby, of Leicester University's School of Archaeology and Ancient History, imaged the spinal column, and reconstructed a model using 3D printing, and concluded that though the spinal scoliosis looked dramatic, it probably did not cause any major physical deformity that could not be disguised by clothing.

Marriage and family relationships

Following a decisive Yorkist victory over the Lancastrians at the Battle of Tewkesbury, Richard married Anne Neville on 12 July 1472. Anne had previously been wedded to Edward of Westminster, only son of Henry VI, to seal her father's allegiance to the Lancastrian party, Edward died at the Battle of Tewkesbury on 4 May 1471, while Warwick had died at the Battle of Barnet on 14 April 1471. Richard's marriage plans brought him into conflict with his brother George. John Paston's letter of 17 February 1472 makes it clear that George was not happy about the marriage but grudgingly accepted it on the basis that "he may well have my Lady his sister-in-law, but they shall part no livelihood". The reason was the inheritance Anne shared with her elder sister Isabel, whom George had married in 1469. It was not only the earldom that was at stake; Richard Neville had inherited it as a result of his marriage to

Following a decisive Yorkist victory over the Lancastrians at the Battle of Tewkesbury, Richard married Anne Neville on 12 July 1472. Anne had previously been wedded to Edward of Westminster, only son of Henry VI, to seal her father's allegiance to the Lancastrian party, Edward died at the Battle of Tewkesbury on 4 May 1471, while Warwick had died at the Battle of Barnet on 14 April 1471. Richard's marriage plans brought him into conflict with his brother George. John Paston's letter of 17 February 1472 makes it clear that George was not happy about the marriage but grudgingly accepted it on the basis that "he may well have my Lady his sister-in-law, but they shall part no livelihood". The reason was the inheritance Anne shared with her elder sister Isabel, whom George had married in 1469. It was not only the earldom that was at stake; Richard Neville had inherited it as a result of his marriage to Anne Beauchamp, 16th Countess of Warwick

Anne Beauchamp, 16th Countess of Warwick (13 July 1426 – 20 September 1492) was an important late medieval English noblewoman. She was the daughter of Richard Beauchamp, 13th Earl of Warwick, and his second wife Isabel le Despenser, a daught ...

. The Countess, who was still alive, was technically the owner of the substantial Beauchamp estates, her father having left no male heirs.

The Croyland Chronicle records that Richard agreed to a prenuptial contract in the following terms: "the marriage of the Duke of Gloucester with Anne before-named was to take place, and he was to have such and so much of the earl's lands as should be agreed upon between them through the mediation of arbitrators; while all the rest were to remain in the possession of the Duke of Clarence". The date of Paston's letter suggests the marriage was still being negotiated in February 1472. In order to win George's final consent to the marriage, Richard renounced most of the Earl of Warwick's land and property including the earldoms of Warwick (which the Kingmaker had held in his wife's right) and Salisbury and surrendered to George the office of Great Chamberlain of England. Richard retained Neville's forfeit estates he had already been granted in the summer of 1471: Penrith, Sheriff Hutton and Middleham, where he later established his marital household.

The requisite papal dispensation was obtained dated 22 April 1472. Michael Hicks has suggested that the terms of the dispensation deliberately understated the degrees of consanguinity between the couple, and the marriage was therefore illegal on the ground of first degree consanguinity following George's marriage to Anne's sister Isabel. There would have been first-degree consanguinity if Richard had sought to marry Isabel (in case of widowhood) after she had married his brother George, but no such consanguinity applied for Anne and Richard. Richard's marriage to Anne was never declared null, and it was public to everyone including secular and canon lawyers for 13 years.

In June 1473, Richard persuaded his mother-in-law to leave the sanctuary and come to live under his protection at Middleham. Later in the year, under the terms of the 1473 Act of Resumption, George lost some of the property he held under royal grant and made no secret of his displeasure. John Paston's letter of November 1473 says that King Edward planned to put both his younger brothers in their place by acting as "a stifler atween them". Early in 1474, Parliament assembled and Edward attempted to reconcile his brothers by stating that both men, and their wives, would enjoy the Warwick inheritance just as if the Countess of Warwick "was naturally dead". The doubts cast by George on the validity of Richard and Anne's marriage were addressed by a clause protecting their rights in the event they were divorced (i.e. of their marriage being declared null and void by the Church) and then legally remarried to each other, and also protected Richard's rights while waiting for such a valid second marriage with Anne. The following year, Richard was rewarded with all the Neville lands in the north of England, at the expense of Anne's cousin, George Neville, 1st Duke of Bedford. From this point, George seems to have fallen steadily out of King Edward's favour, his discontent coming to a head in 1477 when, following Isabel's death, he was denied the opportunity to marry Mary of Burgundy, the stepdaughter of his sister Margaret, even though Margaret approved the proposed match. There is no evidence of Richard's involvement in George's subsequent conviction and execution on a charge of treason.

The requisite papal dispensation was obtained dated 22 April 1472. Michael Hicks has suggested that the terms of the dispensation deliberately understated the degrees of consanguinity between the couple, and the marriage was therefore illegal on the ground of first degree consanguinity following George's marriage to Anne's sister Isabel. There would have been first-degree consanguinity if Richard had sought to marry Isabel (in case of widowhood) after she had married his brother George, but no such consanguinity applied for Anne and Richard. Richard's marriage to Anne was never declared null, and it was public to everyone including secular and canon lawyers for 13 years.

In June 1473, Richard persuaded his mother-in-law to leave the sanctuary and come to live under his protection at Middleham. Later in the year, under the terms of the 1473 Act of Resumption, George lost some of the property he held under royal grant and made no secret of his displeasure. John Paston's letter of November 1473 says that King Edward planned to put both his younger brothers in their place by acting as "a stifler atween them". Early in 1474, Parliament assembled and Edward attempted to reconcile his brothers by stating that both men, and their wives, would enjoy the Warwick inheritance just as if the Countess of Warwick "was naturally dead". The doubts cast by George on the validity of Richard and Anne's marriage were addressed by a clause protecting their rights in the event they were divorced (i.e. of their marriage being declared null and void by the Church) and then legally remarried to each other, and also protected Richard's rights while waiting for such a valid second marriage with Anne. The following year, Richard was rewarded with all the Neville lands in the north of England, at the expense of Anne's cousin, George Neville, 1st Duke of Bedford. From this point, George seems to have fallen steadily out of King Edward's favour, his discontent coming to a head in 1477 when, following Isabel's death, he was denied the opportunity to marry Mary of Burgundy, the stepdaughter of his sister Margaret, even though Margaret approved the proposed match. There is no evidence of Richard's involvement in George's subsequent conviction and execution on a charge of treason.

Reign of Edward IV

Estates and titles

Richard was granted the Duchy of Gloucester on 1 November 1461, and on 12 August the next year was awarded large estates innorthern England

Northern England, also known as the North of England, the North Country, or simply the North, is the northern area of England. It broadly corresponds to the former borders of Angles, Angle Northumbria, the Anglo-Scandinavian Scandinavian York, K ...

, including the lordships of Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, Californi ...

in Yorkshire, and Pembroke in Wales. He gained the forfeited lands of the Lancastrian John de Vere, 12th Earl of Oxford, in East Anglia

East Anglia is an area in the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire. The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, a people whose name originated in Anglia, in ...

. In 1462, on his birthday, he was made Constable of Gloucester

Gloucester ( ) is a cathedral city and the county town of Gloucestershire in the South West of England. Gloucester lies on the River Severn, between the Cotswolds to the east and the Forest of Dean to the west, east of Monmouth and east o ...

and Corfe Castles and Admiral of England, Ireland and Aquitaine and appointed Governor of the North, becoming the richest and most powerful noble in England. On 17 October 1469, he was made Constable of England

The Lord High Constable of England is the seventh of the Great Officers of State, ranking beneath the Lord Great Chamberlain and above the Earl Marshal. This office is now called out of abeyance only for coronations. The Lord High Constable w ...

. In November, he replaced William Hastings, 1st Baron Hastings, as Chief Justice of North Wales. The following year, he was appointed Chief Steward and Chamberlain of Wales. On 18 May 1471, Richard was named Great Chamberlain and Lord High Admiral of England. Other positions followed: High Sheriff of Cumberland for life, Lieutenant of the North and Commander-in-Chief against the Scots and hereditary Warden of the West March. Two months later, on 14 July, he gained the Lordships of the strongholds Sheriff Hutton

Sheriff Hutton is a village and civil parish in the Ryedale district of North Yorkshire, England. It lies about north by north-east of York.

History

The village is mentioned twice in the Domesday Book of 1086, as ''Hotun'' in the Bulford hun ...

and Middleham in Yorkshire and Penrith in Cumberland, which had belonged to Warwick the Kingmaker. It is possible that the grant of Middleham seconded Richard's personal wishes.

Exile and return

During the latter part of Edward IV's reign, Richard demonstrated his loyalty to the king, in contrast to their brother George who had allied himself with the Earl of Warwick when the latter rebelled towards the end of the 1460s. Following Warwick's 1470 rebellion, before which he had made peace with Margaret of Anjou and promised the restoration of Henry VI to the English throne, Richard, the Baron Hastings and Anthony Woodville, 2nd Earl Rivers, escaped capture atDoncaster

Doncaster (, ) is a city in South Yorkshire, England. Named after the River Don, it is the administrative centre of the larger City of Doncaster. It is the second largest settlement in South Yorkshire after Sheffield. Doncaster is situated in ...

by Warwick's brother, John Neville, 1st Marquess of Montagu

John Neville, 1st Marquess of Montagu (c. 1431 – 14 April 1471) was a major magnate of fifteenth-century England. He was a younger son of Richard Neville, 5th Earl of Salisbury, and the younger brother of Richard Neville, Earl of Warwi ...

. On 2 October they sailed from King's Lynn in two ships; Edward landed at Marsdiep and Richard at Zeeland. It was said that, having left England in such haste as to possess almost nothing, Edward was forced to pay their passage with his fur cloak; certainly, Richard borrowed three pounds from Zeeland's town bailiff. They were attainted

In English criminal law, attainder or attinctura was the metaphorical "stain" or "corruption of blood" which arose from being condemned for a serious capital crime (felony or treason). It entailed losing not only one's life, property and heredit ...

by Warwick's only Parliament on 26 November. They resided in Bruges

Bruges ( , nl, Brugge ) is the capital and largest City status in Belgium, city of the Provinces of Belgium, province of West Flanders in the Flemish Region of Belgium, in the northwest of the country, and the sixth-largest city of the countr ...

with Louis de Gruthuse, who had been the Burgundian Ambassador to Edward's court, but it was not until Louis XI of France declared war on Burgundy that Charles, Duke of Burgundy, assisted their return, providing, along with the Hanseatic merchants, 20,000 pounds, 36 ships and 1,200 men. They departed Flushing for England on 11 March 1471. Warwick's arrest of local sympathisers prevented them from landing in Yorkist East Anglia and on 14 March, after being separated in a storm, their ships ran ashore at Holderness. The town of Hull

Hull may refer to:

Structures

* Chassis, of an armored fighting vehicle

* Fuselage, of an aircraft

* Hull (botany), the outer covering of seeds

* Hull (watercraft), the body or frame of a ship

* Submarine hull

Mathematics

* Affine hull, in affi ...

refused Edward entry. He gained entry to York by using the same claim as Henry of Bolingbroke had before deposing Richard II in 1399; that is, that he was merely reclaiming the Dukedom of York rather than the crown. It was in Edward's attempt to regain his throne that Richard began to demonstrate his skill as a military commander.

1471 military campaign

Once Edward had regained the support of his brother George, he mounted a swift and decisive campaign to regain the crown through combat; it is believed that Richard was his principal lieutenant as some of the king's earliest support came from members of Richard's affinity, including Sir James Harrington and Sir William Parr, who brought 600 men-at-arms to them at Doncaster. Richard may have led the vanguard at the Battle of Barnet, in his first command, on 14 April 1471, where he outflanked the wing of Henry Holland, 3rd Duke of Exeter, although the degree to which his command was fundamental may have been exaggerated. That Richard's personal household sustained losses indicates he was in the thick of the fighting. A contemporary source is clear about his holding the vanguard for Edward at Tewkesbury, deployed against the Lancastrian vanguard under Edmund Beaufort, 4th Duke of Somerset, on 4 May 1471, and his role two days later, as Constable of England, sitting alongsideJohn Howard

John Winston Howard (born 26 July 1939) is an Australian former politician who served as the 25th prime minister of Australia from 1996 to 2007, holding office as leader of the Liberal Party. His eleven-year tenure as prime minister is the ...

as Earl Marshal, in the trial and sentencing of leading Lancastrians captured after the battle.

1475 invasion of France

At least in part resentful of King Louis XI's previous support of his Lancastrian opponents, and possibly in support of his brother-in-law Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, Edward went to parliament in October 1472 for funding a military campaign, and eventually landed inCalais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Although Calais is by far the largest city in Pas-de-Calais, the department's prefecture is its third-largest city of Arras. Th ...

on 4 July 1475. Richard's was the largest private contingent of his army. Although well known to have publicly been against the eventual treaty signed with Louis XI at Picquigny

Picquigny () is a commune in the Somme department in Hauts-de-France in northern France.

Geography

Picquigny is situated at the junction of the N235, the D141 and D3 roads, on the banks of the river Somme, some northwest (and downstream) of ...

(and absent from the negotiations, in which one of his rank would have been expected to take a leading role), he acted as Edward's witness when the king instructed his delegates to the French court, and received 'some very fine presents' from Louis on a visit to the French king at Amiens

Amiens (English: or ; ; pcd, Anmien, or ) is a city and commune in northern France, located north of Paris and south-west of Lille. It is the capital of the Somme department in the region of Hauts-de-France. In 2021, the population of ...

. In refusing other gifts, which included 'pensions' in the guise of 'tribute', he was joined only by Cardinal Bourchier

Thomas Bourchier (140430 March 1486) was a medieval English cardinal, Archbishop of Canterbury, and Lord Chancellor of England.

Origins

Bourchier was a younger son of William Bourchier, 1st Count of Eu (died 1420) by his wife Anne of Gloucest ...

. He supposedly disapproved of Edward's policy of personally benefiting—politically and financially—from a campaign paid for out of a parliamentary grant, and hence out of public funds. Any military prowess was therefore not to be revealed further until the last years of Edward's reign.

The North, and the Council in the North

Richard was the dominant magnate in the north of England until Edward IV's death. There, and especially in the city ofYork

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

, he was highly regarded; although it has been questioned whether this view was reciprocated by Richard. Edward IV delegated significant authority to Richard in the region. Kendall and later historians have suggested that this was with the intention of making Richard the ''Lord of the North''; Peter Booth, however, has argued that "instead of allowing his brother Richard '' carte blanche'', dward restricted his influence by using his own agent, Sir William Parr." Following Richard's accession to the throne, he first established the Council of the North

The Council of the North was an administrative body first set up in 1484 by King Richard III of England, to improve access to conciliar justice in Northern England. This built upon steps by King Edward IV of England in delegating authority in the ...

and made his nephew John de la Pole, 1st Earl of Lincoln, president and formally institutionalised this body as an offshoot of the royal Council; all its letters and judgements were issued on behalf of the king and in his name. The council had a budget of 2,000 marks per annum and had issued "Regulations" by July of that year: councillors to act impartially, declare vested interests and to meet at least every three months. Its main focus of operations was Yorkshire and the north-east and its responsibilities included land disputes, keeping of the king's peace and punishing lawbreakers.

War with Scotland

Richard's increasing role in the north from the mid-1470s to some extent explains his withdrawal from the royal court. He had been Warden of the West March on the Scottish border since 10 September 1470, and again from May 1471; he used Penrith as a base while 'taking effectual measures' against the Scots, and 'enjoyed the revenues of the estates' of the Forest of Cumberland while doing so. It was at the same time that the Duke of Gloucester was appointed sheriff of Cumberland five consecutive years, being described as 'of Penrith Castle' in 1478. By 1480, war with Scotland was looming; on 12 May that year he was appointed Lieutenant-General of the North (a position created for the occasion) as fears of a Scottish invasion grew. Louis XI of France had attempted to negotiate a military alliance with Scotland (in the tradition of the " Auld Alliance"), with the aim of attacking England, according to a contemporary French chronicler. Richard had the authority to summon the Border Levies and issue Commissions of Array to repel the Border raids. Together with the Earl of Northumberland, he launched counter-raids, and when the king and council formally declared war in November 1480, he was granted 10,000 pounds for wages. The king failed to arrive to lead the English army and the result was intermittent skirmishing until early 1482. Richard witnessed the treaty withAlexander, Duke of Albany

Alexander Stewart, Duke of Albany (7 August 1485), was a Scottish prince and the second surviving son of King James II of Scotland. He fell out with his older brother, King James III, and fled to France, where he unsuccessfully sought help. In 1 ...

, brother of King James III of Scotland

James III (10 July 1451/May 1452 – 11 June 1488) was King of Scots from 1460 until his death at the Battle of Sauchieburn in 1488. He inherited the throne as a child following the death of his father, King James II, at the siege of Roxburgh C ...

. Northumberland, Stanley, Dorset, Sir Edward Woodville, and Richard with approximately 20,000 men took the town of Berwick almost immediately. The castle held until 24 August 1482, when Richard recaptured Berwick-upon-Tweed from the Kingdom of Scotland

The Kingdom of Scotland (; , ) was a sovereign state in northwest Europe traditionally said to have been founded in 843. Its territories expanded and shrank, but it came to occupy the northern third of the island of Great Britain, sharing a l ...

. Although it is debatable whether the English victory was due more to internal Scottish divisions rather than any outstanding military prowess by Richard, it was the last time that the Royal Burgh

A royal burgh () was a type of Scottish burgh which had been founded by, or subsequently granted, a royal charter. Although abolished by law in 1975, the term is still used by many former royal burghs.

Most royal burghs were either created by ...

of Berwick changed hands between the two realms.

Lord Protector

On the death of Edward IV on 9 April 1483, his 12-year-old son,Edward V

Edward V (2 November 1470 – mid-1483)R. F. Walker, "Princes in the Tower", in S. H. Steinberg et al, ''A New Dictionary of British History'', St. Martin's Press, New York, 1963, p. 286. was ''de jure'' King of England and Lord of Ireland fr ...

, succeeded him. Richard was named Lord Protector of the Realm and at Baron Hastings' urging, Richard assumed his role and left his base in Yorkshire for London. On 29 April, as previously agreed, Richard and his cousin, Henry Stafford, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, met Queen Elizabeth's brother, Anthony Woodville, Earl Rivers, at Northampton

Northampton () is a market town and civil parish in the East Midlands of England, on the River Nene, north-west of London and south-east of Birmingham. The county town of Northamptonshire, Northampton is one of the largest towns in England ...

. At the queen's request, Earl Rivers was escorting the young king to London with an armed escort of 2,000 men, while Richard and Buckingham's joint escort was 600 men. Edward V had been sent further south to Stony Stratford

Stony Stratford is a constituent town of Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire, England. Historically it was a market town on the important route from London to Chester ( Watling Street, now the A5). It is also the name of a civil parish with a town ...

. At first convivial, Richard had Earl Rivers, his nephew Richard Grey and his associate, Thomas Vaughan, arrested. They were taken to Pontefract Castle, where they were executed on 25 June on the charge of treason against the Lord Protector after appearing before a tribunal led by Henry Percy, 4th Earl of Northumberland. Rivers had appointed Richard as executor of his will.

After having Rivers arrested, Richard and Buckingham moved to Stony Stratford, where Richard informed Edward V of a plot aimed at denying him his role as protector and whose perpetrators had been dealt with. He proceeded to escort the king to London. They entered the city on 4 May, displaying the carriages of weapons Rivers had taken with his 2,000-man army. Richard first accommodated Edward in the Bishop's apartments; then, on Buckingham's suggestion, the king was moved to the royal apartments of the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

, where kings customarily awaited their coronation. Within the year 1483, Richard had moved himself to the grandeur of Crosby Hall, London

Crosby Hall is a historic building in London. The Great Hall was built in 1466 and originally known as Crosby Place in Bishopsgate, in the City of London. It was moved in 1910 to its present site in Cheyne Walk, Chelsea. It now forms part of a ...

, then in Bishopsgate in the City of London. Robert Fabyan, in his 'The new chronicles of England and of France', writes that "the Duke caused the King (Edward V) to be removed unto the Tower and his broder with hym, and the Duke lodged himselfe in Crosbyes Place in Bisshoppesgate Strete." In '' Holinshed's Chronicles'' of England, Scotland, and Ireland, he accounts that "little by little all folke withdrew from the Tower, and drew unto Crosbies in Bishops gates Street, where the Protector kept his houshold. The Protector had the resort; the King in maner desolate."

On hearing the news of her brother's 30 April arrest, the dowager queen fled to sanctuary in Westminster Abbey. Joining her were her son by her first marriage, Thomas Grey, 1st Marquess of Dorset; her five daughters; and her youngest son, Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York. On 10/11 June, Richard wrote to Ralph, Lord Neville, the City of York and others asking for their support against "the Queen, her blood adherents and affinity" whom he suspected of plotting his murder. At a council meeting on 13 June at the Tower of London, Richard accused Hastings and others of having conspired against him with the Woodvilles and accusing Jane Shore, lover to both Hastings and Thomas Grey, of acting as a go-between. According to Thomas More, Hastings was taken out of the council chambers and summarily executed in the courtyard, while others, like Lord Thomas Stanley and John Morton, Bishop of Ely, were arrested. Hastings was not attainted and Richard sealed an indenture that placed Hastings' widow, Katherine, under his protection. Bishop Morton was released into the custody of Buckingham. On 16 June, the dowager queen agreed to hand over the Duke of York to the Archbishop of Canterbury so that he might attend his brother Edward's coronation, still planned for 22 June.

King of England

Bishop Robert Stillington, the Bishop of Bath and Wells, is said to have informed Richard that Edward IV's marriage to Elizabeth Woodville was invalid because of Edward's earlier union with Eleanor Butler, making Edward V and his siblings illegitimate. The identity of Stillington was known only through the memoirs of French diplomat Philippe de Commines. On 22 June, a sermon was preached outside

Bishop Robert Stillington, the Bishop of Bath and Wells, is said to have informed Richard that Edward IV's marriage to Elizabeth Woodville was invalid because of Edward's earlier union with Eleanor Butler, making Edward V and his siblings illegitimate. The identity of Stillington was known only through the memoirs of French diplomat Philippe de Commines. On 22 June, a sermon was preached outside Old St. Paul's Cathedral

Old St Paul's Cathedral was the cathedral of the City of London that, until the Great Fire of 1666, stood on the site of the present St Paul's Cathedral. Built from 1087 to 1314 and dedicated to Saint Paul, the cathedral was perhaps the fourth ...

by Ralph Shaa

Ralph Shaa (sometimes erroneouslyWestminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

on 6 July. His title to the throne was confirmed by Parliament in January 1484 by the document '' Titulus Regius''.

The princes

A prince is a male ruler (ranked below a king, grand prince, and grand duke) or a male member of a monarch's or former monarch's family. ''Prince'' is also a title of nobility (often highest), often hereditary, in some European states. The ...

, who were still lodged in the royal residence of the Tower of London at the time of Richard's coronation, disappeared from sight after the summer of 1483. Although after his death Richard III was accused of having Edward and his brother killed, notably by More and in Shakespeare's play, the facts surrounding their disappearance remain unknown. Other culprits have been suggested, including Buckingham and even Henry VII, although Richard remains a suspect.

After the coronation ceremony, Richard and Anne set out on a royal progress to meet their subjects. During this journey through the country, the king and queen endowed King's College and Queens' College

Queens' College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Queens' is one of the oldest colleges of the university, founded in 1448 by Margaret of Anjou. The college spans the River Cam, colloquially referred to as the "light sid ...

at Cambridge University

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

, and made grants to the church. Still feeling a strong bond with his northern estates, Richard later planned the establishment of a large chantry chapel in York Minster with over 100 priests. He also founded the College of Arms

The College of Arms, or Heralds' College, is a royal corporation consisting of professional officers of arms, with jurisdiction over England, Wales, Northern Ireland and some Commonwealth realms. The heralds are appointed by the British Sover ...

.

Buckingham's rebellion of 1483

In 1483, aconspiracy

A conspiracy, also known as a plot, is a secret plan or agreement between persons (called conspirers or conspirators) for an unlawful or harmful purpose, such as murder or treason, especially with political motivation, while keeping their agr ...

arose among a number of disaffected gentry, many of whom had been supporters of Edward IV and the "whole Yorkist establishment". The conspiracy was nominally led by Richard's former ally, the Duke of Buckingham, although it had begun as a Woodville-Beaufort conspiracy (being "well underway" by the time of the Duke's involvement). Davies has suggested that it was "only the subsequent parliamentary attainder that placed Buckingham at the centre of events", to blame a disaffected magnate motivated by greed, rather than "the embarrassing truth" that those opposing Richard were actually "overwhelmingly Edwardian loyalists". It is possible that they planned to depose Richard III and place Edward V back on the throne, and that when rumours arose that Edward and his brother were dead, Buckingham proposed that Henry Tudor should return from exile, take the throne and marry Elizabeth, eldest daughter of Edward IV. It has also been pointed out that as this narrative stems from Richard's parliament of 1484, it should probably be treated "with caution". For his part, Buckingham raised a substantial force from his estates in Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the Bristol Channel to the south. It had a population in ...

and the Marches. Henry, in exile in Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica during the period ...

, enjoyed the support of the Breton treasurer Pierre Landais, who hoped Buckingham's victory would cement an alliance between Brittany and England.

Some of Henry Tudor's ships ran into a storm and were forced to return to Brittany or Normandy, while Henry anchored off Plymouth for a week before learning of Buckingham's failure. Buckingham's army was troubled by the same storm and deserted when Richard's forces came against them. Buckingham tried to escape in disguise, but was either turned in by a retainer for the bounty

Bounty or bounties commonly refers to:

* Bounty (reward), an amount of money or other reward offered by an organization for a specific task done with a person or thing

Bounty or bounties may also refer to:

Geography

* Bounty, Saskatchewan, a g ...

Richard had put on his head, or was discovered in hiding with him. He was convicted of treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

and beheaded in Salisbury

Salisbury ( ) is a cathedral city in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers Avon, Nadder and Bourne. The city is approximately from Southampton and from Bath.

Salisbury is in the southeast of ...

, near the Bull's Head Inn, on 2 November. His widow, Catherine Woodville, later married Jasper Tudor, the uncle of Henry Tudor. Richard made overtures to Landais, offering military support for Landais's weak regime under Francis II, Duke of Brittany, in exchange for Henry. Henry fled to Paris, where he secured support from the French regent Anne of Beaujeu

Anne of France (or Anne de Beaujeu; 3 April 146114 November 1522) was a French princess and regent, the eldest daughter of Louis XI by Charlotte of Savoy. Anne was the sister of Charles VIII, for whom she acted as regent during his minority from ...

, who supplied troops for an invasion in 1485.

Death at the Battle of Bosworth Field

On 22 August 1485, Richard met the outnumbered forces of Henry Tudor at the

On 22 August 1485, Richard met the outnumbered forces of Henry Tudor at the Battle of Bosworth Field

The Battle of Bosworth or Bosworth Field was the last significant battle of the Wars of the Roses, the civil war between the houses of Lancaster and York that extended across England in the latter half of the 15th century. Fought on 22 Augu ...

. Richard rode a white courser (an especially swift and strong horse). The size of Richard's army has been estimated at 8,000 and Henry's at 5,000, but exact numbers are not known, though the royal army is believed to have "substantially" outnumbered Henry's. The traditional view of the king's famous cries of "Treason!" before falling was that during the battle Richard was abandoned by Baron Stanley (made Earl of Derby in October), Sir William Stanley, and Henry Percy, 4th Earl of Northumberland. The role of Northumberland is unclear; his position was with the reserve—behind the king's line—and he could not easily have moved forward without a general royal advance, which did not take place. The physical confines behind the crest of Ambion Hill, combined with a difficulty of communications, probably physically hampered any attempt he made to join the fray. Despite appearing "a pillar of the Ricardian regime" and his previous loyalty to Edward IV, Baron Stanley was the stepfather of Henry Tudor and Stanley's inaction combined with his brother's entering the battle on Tudor's behalf was fundamental to Richard's defeat. The death of Richard's close companion John Howard, Duke of Norfolk

John Howard, 1st Duke of Norfolk (c. 142522 August 1485), was an English nobleman, soldier, politician, and the first Howard Duke of Norfolk. He was a close friend and loyal supporter of King Richard III, with whom he was slain at the Bat ...

, may have had a demoralising effect on the king and his men. Either way, Richard led a cavalry charge deep into the enemy ranks in an attempt to end the battle quickly by striking at Henry Tudor.

All accounts note that King Richard fought bravely and ably during this manoeuvre, unhorsing Sir John Cheyne, a well-known jousting champion, killing Henry's standard bearer Sir William Brandon and coming within a sword's length of Henry Tudor before being surrounded by Sir William Stanley's men and killed.

All accounts note that King Richard fought bravely and ably during this manoeuvre, unhorsing Sir John Cheyne, a well-known jousting champion, killing Henry's standard bearer Sir William Brandon and coming within a sword's length of Henry Tudor before being surrounded by Sir William Stanley's men and killed. Polydore Vergil

Polydore Vergil or Virgil (Italian: ''Polidoro Virgili''; commonly Latinised as ''Polydorus Vergilius''; – 18 April 1555), widely known as Polydore Vergil of Urbino, was an Italian humanist scholar, historian, priest and diplomat, who spent ...

, Henry VII's official historian, recorded that "King Richard, alone, was killed fighting manfully in the thickest press of his enemies". The Burgundian chronicler, Jean Molinet, states that a Welshman struck the death-blow with a halberd

A halberd (also called halbard, halbert or Swiss voulge) is a two-handed pole weapon that came to prominent use during the 13th, 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries. The word ''halberd'' is cognate with the German word ''Hellebarde'', deriving from ...

while Richard's horse was stuck in the marshy ground. It was said that the blows were so violent that the king's helmet was driven into his skull. The contemporary Welsh poet Guto'r Glyn

Guto'r Glyn (c. 1412 – c. 1493) was a Welsh language poet and soldier of the era of the ''Beirdd yr Uchelwyr'' ("Poets of the Nobility") or ''Cywyddwyr'' ("cywydd-men"), the itinerant professional poets of the later Middle Ages. He is consid ...

implies a leading Welsh Lancastrian, Rhys ap Thomas

Sir Rhys ap Thomas (1449–1525) was a Welsh soldier and landholder who rose to prominence during the Wars of the Roses, and was instrumental in the victory of Henry Tudor at the Battle of Bosworth. He remained a faithful supporter of Henry ...

, or one of his men killed the king, writing that he "killed the boar, shaved his head". The identification in 2013 of King Richard's body shows that the skeleton had 11 wounds, eight of them to the skull, clearly inflicted in battle and suggesting he had lost his helmet. Professor Guy Rutty, from the University of Leicester, said: "The most likely injuries to have caused the king's death are the two to the inferior aspect of the skull—a large sharp force trauma possibly from a sword or staff weapon, such as a halberd or bill, and a penetrating injury from the tip of an edged weapon." The skull showed that a blade had hacked away part of the rear of the skull. Richard III was the last English king to be killed in battle. Henry Tudor succeeded Richard as King Henry VII. He married the Yorkist heiress Elizabeth of York, Edward IV's daughter and Richard III's niece.

After the Battle of Bosworth, Richard's naked body was then carried back to Leicester tied to a horse, and early sources strongly suggest that it was displayed in the collegiate Church of the Annunciation of Our Lady of the Newarke

The Church of the Annunciation of Our Lady of the Newarke in Leicester, was a collegiate church founded by Henry of Grosmont, 1st Duke of Lancaster, in 1353. The name "Newarke" is a translation of the Latin "novum opus" i.e. "new work" and was use ...

, prior to being hastily and discreetly buried in the choir of Greyfriars Church in Leicester

Leicester ( ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, city, Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority and the county town of Leicestershire in the East Midlands of England. It is the largest settlement in the East Midlands.

The city l ...

. In 1495, Henry VII paid 50 pounds for a marble and alabaster monument. According to a discredited tradition, during the Dissolution of the Monasteries, his body was thrown into the River Soar

The River Soar () is a major tributary of the River Trent in the English East Midlands and is the principal river of Leicestershire. The source of the river is midway between Hinckley and Lutterworth. The river then flows north through Leices ...

, although other evidence suggests that a memorial stone was visible in 1612, in a garden built on the site of Greyfriars. The exact location was then lost, owing to more than 400 years of subsequent development, until archaeological investigations in 2012 revealed the site of the garden and Greyfriars Church. There was a memorial ledger stone in the choir of the cathedral, since replaced by the tomb of the king, and a stone plaque on Bow Bridge where tradition had falsely suggested that his remains had been thrown into the river.

According to another tradition, Richard consulted a seer in Leicester before the battle who foretold that "where your spur should strike on the ride into battle, your head shall be broken on the return". On the ride into battle, his spur struck the bridge stone of Bow Bridge in the city; legend states that as his corpse was carried from the battle over the back of a horse, his head struck the same stone and was broken open.

Issue

Richard and Anne had one son,Edward of Middleham

cy, Edward o Middleham

, house = York

, father = Richard III of England

, mother = Anne Neville

, birth_date = or 1476

, birth_place = Middleham, Wensleydale, England

, death_date = 9 April 1484 (aged 7–10)

, death_place ...

, who was born between 1474 and 1476. He was created Earl of Salisbury on 15 February 1478, and Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rule ...

on 24 August 1483, and died in March 1484, less than two months after he had been formally declared heir apparent

An heir apparent, often shortened to heir, is a person who is first in an order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person; a person who is first in the order of succession but can be displaced by the b ...

. After the death of his son, Richard appointed his nephew John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln, as Lieutenant of Ireland, an office previously held by his son Edward. Lincoln was the son of Richard's older sister, Elizabeth, Duchess of Suffolk

Elizabeth of York, Duchess of Suffolk also known as Elizabeth Plantagenet (22 April 1444 – c. 1503) was the sixth child and third daughter of Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York (a great-grandson of King Edward III) and Cecily Neville.Halst ...

. After his wife's death, Richard commenced negotiations with John II of Portugal to marry John's pious sister, Joanna, Princess of Portugal. She had already turned down several suitors because of her preference for the religious life.

Richard had two acknowledged illegitimate children, John of Gloucester

John of Gloucester (or John of Pontefract) (c. 1468 - c. 1499 (based on historical hypothesis)) was an illegitimate son of King Richard III of England. John is so called because his father was Duke of Gloucester at the time of his birth. His fathe ...

and Katherine Plantagenet. Also known as 'John of Pontefract', John of Gloucester was appointed Captain of Calais in 1485. Katherine married William Herbert, 2nd Earl of Pembroke

William Herbert, 2nd Earl of Pembroke (5 March 145116 July 1491) was an English nobleman and politician.

Early life

He was the son of William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke and Anne Devereux. His paternal grandparents were William ap Thomas an ...

, in 1484. Neither the birth dates nor the names of the mothers of either of the children is known. Katherine was old enough to be wedded in 1484, when the age of consent was twelve, and John was knighted in September 1483 in York Minster, and so most historians agree that they were both fathered when Richard was a teenager. There is no evidence of infidelity on Richard's part after his marriage to Anne Neville in 1472 when he was around 20. This has led to a suggestion by the historian A. L. Rowse

Alfred Leslie Rowse (4 December 1903 – 3 October 1997) was a British historian and writer, best known for his work on Elizabethan England and books relating to Cornwall.

Born in Cornwall and raised in modest circumstances, he was encour ...

that Richard "had no interest in sex".

Michael Hicks and Josephine Wilkinson have suggested that Katherine's mother may have been Katherine Haute, on the basis of the grant of an annual payment of 100 shillings made to her in 1477. The Haute family was related to the Woodvilles through the marriage of Elizabeth Woodville's aunt, Joan Wydeville, to William Haute. One of their children was Richard Haute, Controller of the Prince's Household. Their daughter, Alice, married Sir John Fogge; they were ancestors to Catherine Parr, sixth wife of King Henry VIII. They also suggest that John's mother may have been Alice Burgh. Richard visited Pontefract from 1471, in April and October 1473, and in early March 1474, for a week. On 1 March 1474, he granted Alice Burgh 20 pounds a year for life "for certain special causes and considerations". She later received another allowance, apparently for being engaged as a nurse for his brother George's son, Edward of Warwick

Edward Plantagenet, 17th Earl of Warwick (25 February 1475 – 28 November 1499) was the son of Isabel Neville and George Plantagenet, 1st Duke of Clarence, and a potential claimant to the English throne during the reigns of both his uncle, ...

. Richard continued her annuity when he became king. John Ashdown-Hill has suggested that John was conceived during Richard's first solo expedition to the eastern counties in the summer of 1467 at the invitation of John Howard and that the boy was born in 1468 and named after his friend and supporter. Richard himself noted John was still a minor (not being yet 21) when he issued the royal patent appointing him Captain of Calais on 11 March 1485, possibly on his seventeenth birthday.

Both of Richard's illegitimate children survived him, but they seem to have died without issue and their fate after Richard's demise at Bosworth is not certain. John received a 20 pound annuity from Henry VII, but there are no mentions of him in contemporary records after 1487 (the year of the Battle of Stoke Field