Reyes Católicos on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

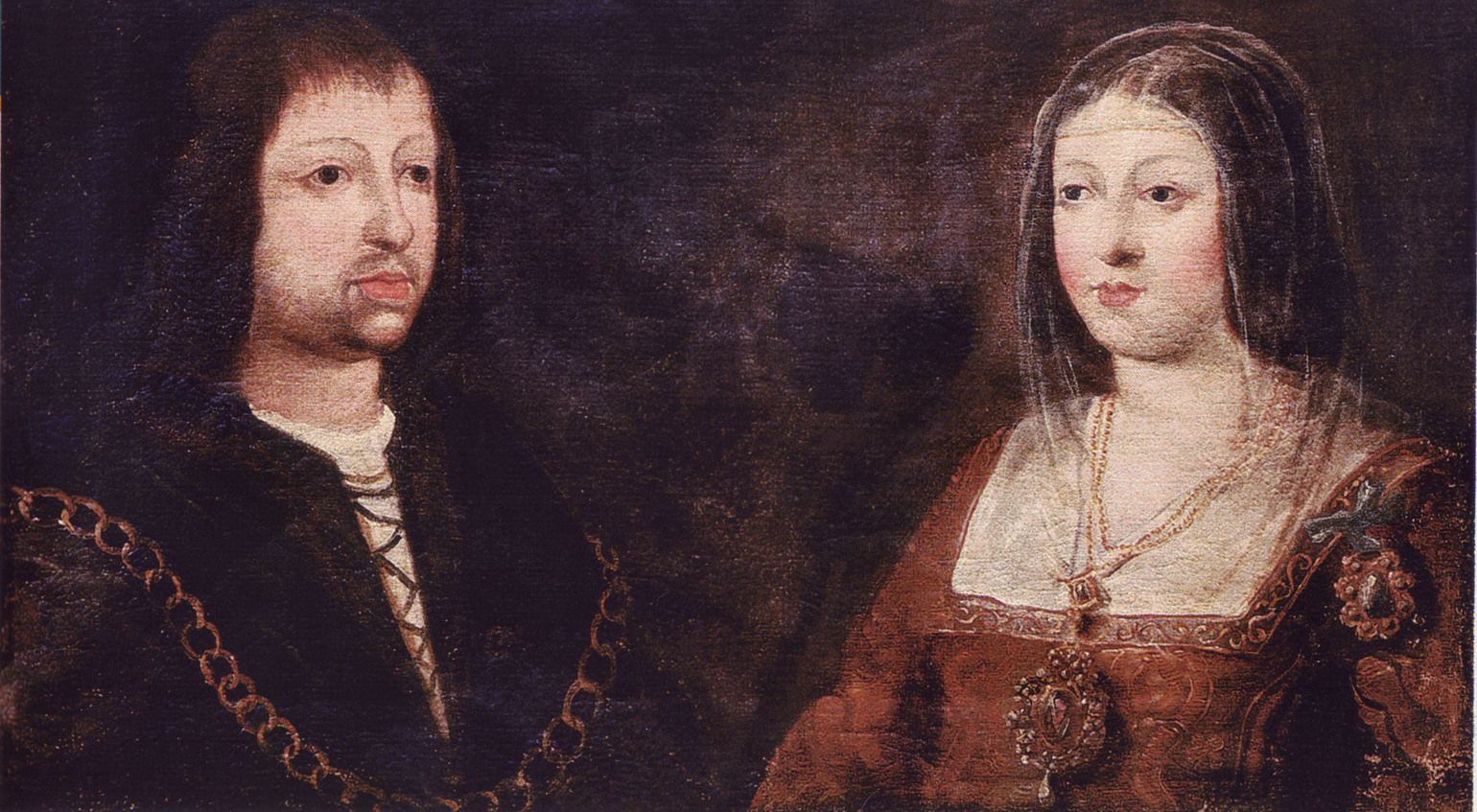

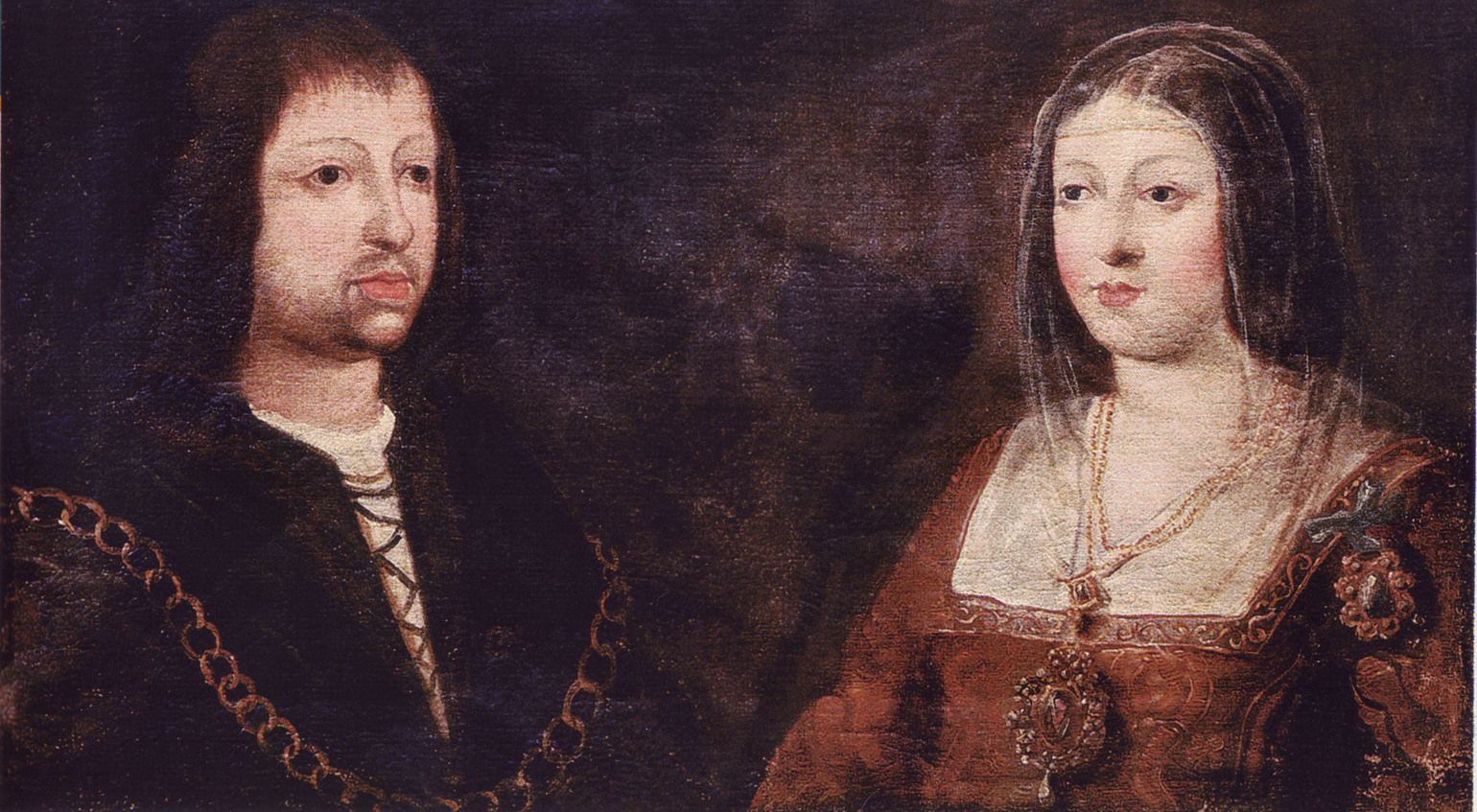

The Catholic Monarchs were

The Catholic Monarchs were

At the time of their marriage on October 19, 1469, Isabella was eighteen years old and the heiress presumptive to the Crown of Castile, while Ferdinand was seventeen and heir apparent to the

At the time of their marriage on October 19, 1469, Isabella was eighteen years old and the heiress presumptive to the Crown of Castile, while Ferdinand was seventeen and heir apparent to the

file:Royal Standard of the Catholic Monarchs (1475-1492).svg, First Royal Standard of the Catholic Monarchs (1475–92)

file:Estandarte real de 1475-1492.svg, Royal Banner of the Catholic Monarchs (1475–92)

file:Royal Standard of the Catholic Monarchs (1492-1506).svg, Second Royal Standard of the Catholic Monarchs (1492–1504/6)

file:Coat of Arms of Queen Isabella of Castile (1492-1504).svg, Coat of Arms of the Catholic Monarchs (1492–1504)

file:Pendón heráldico de los Reyes_Catolicos de 1492-1504.svg, Pennant of the Catholic Monarchs (1492–1504)

The Catholic Monarchs set out to restore royal authority in Spain. To accomplish their goal, they first created a group named the Holy Brotherhood. These men were used as a judicial police force for Castile, as well as to attempt to keep Castilian nobles in check. To establish a more uniform

The Catholic Monarchs set out to restore royal authority in Spain. To accomplish their goal, they first created a group named the Holy Brotherhood. These men were used as a judicial police force for Castile, as well as to attempt to keep Castilian nobles in check. To establish a more uniform

Along with the desire of the Catholic Monarchs to extend their dominion to all the kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula, their reign was characterised by religious unification of the peninsula through militant Catholicism. Petitioning the pope for authority, Pope Sixtus IV issued a bull in 1478 to establish a

Along with the desire of the Catholic Monarchs to extend their dominion to all the kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula, their reign was characterised by religious unification of the peninsula through militant Catholicism. Petitioning the pope for authority, Pope Sixtus IV issued a bull in 1478 to establish a

Through the

Through the

Isabella's death in 1504 ended the remarkably successful political partnership and personal relationship of their marriage. Ferdinand remarried

Isabella's death in 1504 ended the remarkably successful political partnership and personal relationship of their marriage. Ferdinand remarried

Country Studies

{{Authority control * * Married couples Spanish Renaissance people 15th century in Al-Andalus 15th-century Spanish monarchs 16th-century Spanish monarchs Reconquista Spanish Inquisition Spanish colonization of the Americas Spanish Empire Royal styles Founding monarchs Theocrats

The Catholic Monarchs were

The Catholic Monarchs were Queen Isabella I

Isabella I ( es, Isabel I; 22 April 1451 – 26 November 1504), also called Isabella the Catholic (Spanish: ''la Católica''), was Queen of Castile from 1474 until her death in 1504, as well as Queen consort of Aragon from 1479 until 1504 b ...

of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon, whose marriage and joint rule marked the ''de facto'' unification of Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

. They were both from the House of Trastámara

The House of Trastámara ( Spanish, Aragonese and Catalan: Casa de Trastámara) was a royal dynasty which first ruled in the Crown of Castile and then expanded to the Crown of Aragon in the late middle ages to the early modern period.

They were ...

and were second cousins, being both descended from John I of Castile

John I ( es, Juan I; 24 August 1358 – 9 October 1390) was King of Castile and León from 1379 until 1390. He was the son of Henry II and of his wife Juana Manuel of Castile.

Biography

His first marriage, to Eleanor of Aragon on 18 June 137 ...

; to remove the obstacle that this consanguinity

Consanguinity ("blood relation", from Latin '' consanguinitas'') is the characteristic of having a kinship with another person (being descended from a common ancestor).

Many jurisdictions have laws prohibiting people who are related by blood fr ...

would otherwise have posed to their marriage under canon law, they were given a papal dispensation

In the jurisprudence of the canon law of the Catholic Church, a dispensation is the exemption from the immediate obligation of law in certain cases.The Law of Christ Vol. I, pg. 284 Its object is to modify the hardship often arising from the ...

by Sixtus IV. They married on October 19, 1469, in the city of Valladolid

Valladolid () is a municipality in Spain and the primary seat of government and de facto capital of the autonomous community of Castile and León. It is also the capital of the province of the same name. It has a population around 300,000 peop ...

; Isabella was eighteen years old and Ferdinand a year younger. It is generally accepted by most scholars that the unification of Spain can essentially be traced back to the marriage of Ferdinand and Isabella.

Spain was formed as a dynastic union

A dynastic union is a type of union with only two different states that are governed under the same dynasty, with their boundaries, their laws, and their interests remaining distinct from each other.

Historical examples

Union of Kingdom of Arag ...

of two crowns rather than a unitary state, as Castile and Aragon remained separate kingdoms until the Nueva Planta decrees of 1707–16. The court of Ferdinand and Isabella was constantly on the move, in order to bolster local support for the crown from local feudal lords. The title of " Catholic King and Queen" was officially bestowed on Ferdinand and Isabella by Pope Alexander VI in 1494, in recognition of their defence of the Catholic faith within their realms.

Marriage

At the time of their marriage on October 19, 1469, Isabella was eighteen years old and the heiress presumptive to the Crown of Castile, while Ferdinand was seventeen and heir apparent to the

At the time of their marriage on October 19, 1469, Isabella was eighteen years old and the heiress presumptive to the Crown of Castile, while Ferdinand was seventeen and heir apparent to the Crown of Aragon

The Crown of Aragon ( , ) an, Corona d'Aragón ; ca, Corona d'Aragó, , , ; es, Corona de Aragón ; la, Corona Aragonum . was a composite monarchy ruled by one king, originated by the dynastic union of the Kingdom of Aragon and the County of ...

. They met for the first time in Valladolid in 1469 and married within a week. From the start, they had a close relationship and worked well together. Both knew that the crown of Castile was "the prize, and that they were both jointly gambling for it". However, it was a step toward the unification of the lands on the Iberian peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, def ...

, which would eventually become Spain.

They were second cousins, so in order to marry they needed a papal dispensation

In the jurisprudence of the canon law of the Catholic Church, a dispensation is the exemption from the immediate obligation of law in certain cases.The Law of Christ Vol. I, pg. 284 Its object is to modify the hardship often arising from the ...

. Pope Paul II

Pope Paul II ( la, Paulus II; it, Paolo II; 23 February 1417 – 26 July 1471), born Pietro Barbo, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States

from 30 August 1464 to his death in July 1471. When his maternal uncle Eugene IV ...

, an Italian pope opposed to Aragon's influence on the Mediterranean and to the rise of monarchies strong enough to challenge the Pope, refused to grant one,Los Reyes Católicos: la conquista del trono. Madrid: Rialp, 1989. . "La llegada al trono" so they falsified a papal bull of their own. Even though the bull is known to be false, it is uncertain who was the material author of the falsification. Some experts point at Carrillo de Acuña

Carrillo may refer to:

Places

* Carrillo (canton), the fifth division of Guanacaste Province, Costa Rica

* Puerto Carrillo, a small town in Guanacaste, Costa Rica

** Carrillo Airport, which serves Puerto Carrillo

** Carrillo (beach), a beach ...

, Archbishop of Toledo

This is a list of Bishops and Archbishops of Toledo ( la, Archidioecesis Metropolitae Toletana).

, and others point at Antonio Veneris. Pope Paul II remained a bitter enemy of Spain and the monarchy for all his life, and the following quote is attributed to him: "May all Spaniards be cursed by God, schismatics and heretics, the seed of Jews and Moors",

Isabella's claims to it were not secure, since her marriage to Ferdinand enraged her half-brother Henry IV of Castile

Henry IV of Castile ( Castilian: ''Enrique IV''; 5 January 1425 – 11 December 1474), King of Castile and León, nicknamed the Impotent, was the last of the weak late-medieval kings of Castile and León. During Henry's reign, the nobles became ...

and he withdrew his support for her being his heiress presumptive that had been codified in the Treaty of the Bulls of Guisando. Henry instead recognised Joanna of Castile

Joanna (6 November 1479 – 12 April 1555), historically known as Joanna the Mad ( es, link=no, Juana la Loca), was the nominal Queen of Castile from 1504 and Queen of Aragon from 1516 to her death in 1555. She was married by arrangement to P ...

, born during his marriage to Joanna of Portugal, but whose paternity was in doubt, since Henry was rumored to be impotent. When Henry died in 1474, Isabella asserted her claim to the throne, which was contested by thirteen-year-old Joanna. Joanna sought the aid of her husband (who was also her uncle), Afonso V of Portugal

Afonso V () (15 January 1432 – 28 August 1481), known by the sobriquet the African (), was King of Portugal from 1438 until his death in 1481, with a brief interruption in 1477. His sobriquet refers to his military conquests in Northern Afri ...

, to claim the throne. This dispute between rival claimants led to the War of 1475–79. Isabella called on the aid of Aragon, with her husband, the heir apparent, and his father, Juan II of Aragon providing it. Although Aragon provided support for Isabella's cause, Isabella's supporters had extracted concessions, Isabella was acknowledged as the sole heir to the crown of Castile. Juan II died in 1479, and Ferdinand succeeded to the throne in January 1479.

In September 1479, Portugal and the Catholic Monarchs of Aragon and Castile resolved major issues between them through the Treaty of Alcáçovas

The Treaty of Alcáçovas (also known as Treaty or Peace of Alcáçovas-Toledo) was signed on 4 September 1479 between the Catholic Monarchs of Castile and Aragon on one side and Afonso V and his son, Prince John of Portugal, on the other sid ...

, including the issue of Isabella's rights to the crown of Castile. Through close cooperation, the royal couple were successful in securing political power in the Iberian peninsula. Ferdinand's father had advised the couple that "neither was powerful without the other". Though their marriage united the two kingdoms, leading to the beginnings of modern Spain, they ruled independently and their kingdoms retained part of their own regional laws and governments for the next centuries.

Royal motto and emblems

The coat of arms of the Catholic Monarchs was designed byAntonio de Nebrija

Antonio de Nebrija (14445 July 1522) was the most influential Spanish humanist of his era. He wrote poetry, commented on literary works, and encouraged the study of classical languages and literature, but his most important contributions were i ...

with elements to show their cooperation and working in tandem. The royal motto they shared, '' Tanto monta'' ("as much one as the other"), came to signify their cooperation."Liss, "Isabel and Fernando", p. 380. The motto was originally used by Ferdinand as an allusion to the Gordian knot: ''Tanto monta, monta tanto, cortar como desatar'' ("It's one and the same, cutting or untying"), but later adopted as an expression of equality of the monarchs: ''Tanto monta, monta tanto, Isabel como Fernando'' ("It's one and the same, Isabella the same as Ferdinand").

Their emblems or heraldic devices, seen at the bottom of the coat of arms, were a yoke

A yoke is a wooden beam sometimes used between a pair of oxen or other animals to enable them to pull together on a load when working in pairs, as oxen usually do; some yokes are fitted to individual animals. There are several types of yoke, u ...

and a sheaf of arrows. ''Y'' and ''F'' are the initials of Ysabel (spelling at the time) and Fernando. A double yoke is worn by a team of oxen, emphasizing the couple's cooperation. Isabella's emblem of arrows showed the armed power of the crown, "a warning to Castilians not acknowledging the reach of royal authority or that greatest of royal functions, the right to mete out justice" by force of violence. The iconography of the royal crest was widely reproduced and was found on various works of art. These badges were later used by the fascist Spanish political party Falange

The Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista (FET y de las JONS; ), frequently shortened to just "FET", was the sole legal party of the Francoist regime in Spain. It was created by General Francisco ...

, which claimed to represent the inherited glory and the ideals of the Catholic Monarchs.

Royal Councils

The establishment of System of Royal Councils to oversee discrete regions or areas was Isabella succeeded to the throne of Castile in 1474 when Ferdinand was still heir-apparent to Aragon, and with Aragon's aid, Isabella's claim to the throne was secured. As Isabella's husband was king of Castile by his marriage and his father still ruled in Aragon, Ferdinand spent more time in Castile than Aragon at the beginning of their marriage. His pattern of residence Castile persisted even when he succeeded to the throne in 1479, and the absenteeism caused problems for Aragon. These were remedied to an extent by the creation of theCouncil of Aragon

The Council of Aragon, officially, the Royal and Supreme Council of Aragon (Spanish: Real y Supremo Consejo de Aragón; Catalan: Consell Suprem d'Aragó), was a ruling body and key part of the domestic government of the Spanish Empire in Europ ...

in 1494, joining the Council of Castile

The Council of Castile ( es, Real y Supremo Consejo de Castilla), known earlier as the Royal Council ( es, Consejo Real), was a ruling body and key part of the domestic government of the Crown of Castile, second only to the monarch himself. It ...

established in 1480. The Council of Castile was intended "to be the central governing body of Castile and the linch-pin of their governmental system" with wide powers and with royal officials who were loyal to them and excluded the old nobility from exercising power in it. The monarchs created the Spanish Inquisition

The Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition ( es, Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición), commonly known as the Spanish Inquisition ( es, Inquisición española), was established in 1478 by the Catholic Monarchs, King Ferdinand ...

in 1478 to ensure that individuals converting to Christianity did not revert to their old faith or continue practicing it. The Council of the Crusade was created under their rule to administer funds from the sale of crusading bulls. In 1498 after Ferdinand had gained control of the revenues of the wealthy and powerful Spanish military orders

This is a list of some of the modern orders, decorations and medals of Spain.

The bulk of the top current civil and military decorations granted by the Government of Spain in a discretionary manner trace their origins back to the 19th and 20th cen ...

, he created the Council of Military Orders to oversee them. The conciliar model was extended beyond the rule of the Catholic Monarchs, with their grandson, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor establishing the Council of the Indies

The Council of the Indies ( es, Consejo de las Indias), officially the Royal and Supreme Council of the Indies ( es, Real y Supremo Consejo de las Indias, link=no, ), was the most important administrative organ of the Spanish Empire for the Amer ...

, the Council of Finance, and the Council of State

A Council of State is a governmental body in a country, or a subdivision of a country, with a function that varies by jurisdiction. It may be the formal name for the cabinet or it may refer to a non-executive advisory body associated with a head o ...

.

Domestic policy

The Catholic Monarchs set out to restore royal authority in Spain. To accomplish their goal, they first created a group named the Holy Brotherhood. These men were used as a judicial police force for Castile, as well as to attempt to keep Castilian nobles in check. To establish a more uniform

The Catholic Monarchs set out to restore royal authority in Spain. To accomplish their goal, they first created a group named the Holy Brotherhood. These men were used as a judicial police force for Castile, as well as to attempt to keep Castilian nobles in check. To establish a more uniform judicial system

The judiciary (also known as the judicial system, judicature, judicial branch, judiciative branch, and court or judiciary system) is the system of courts that adjudicates legal disputes/disagreements and interprets, defends, and applies the law ...

, the Catholic Monarchs created the Royal Council, and appointed magistrates (judges) to run the towns and cities. This establishment of royal authority is known as the Pacification of Castile, and can be seen as one of the crucial steps toward the creation of one of Europe's first strong nation-states. Isabella also sought various ways to diminish the influence of the ''Cortes Generales

The Cortes Generales (; en, Spanish Parliament, lit=General Courts) are the bicameral legislative chambers of Spain, consisting of the Congress of Deputies (the lower house), and the Senate (the upper house).

The Congress of Deputies meet ...

'' in Castile, though Ferdinand was too thoroughly Aragonese to do anything of the sort with the equivalent systems in the Crown of Aragon. Even after his death and the union of the crowns under one monarch, the Aragonese, Catalan, and Valencian ''Corts'' (parliaments) retained significant power in their respective regions. Further, the monarchs continued ruling through a form of medieval contractualism, which made their rule pre-modern in a few ways. One of those is that they traveled from town to town throughout the kingdom in order to promote loyalty, rather than possessing any single administrative center. Another is that each community and region was connected to them via loyalty to the crown, rather than bureaucratic ties.

Religious policy

Along with the desire of the Catholic Monarchs to extend their dominion to all the kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula, their reign was characterised by religious unification of the peninsula through militant Catholicism. Petitioning the pope for authority, Pope Sixtus IV issued a bull in 1478 to establish a

Along with the desire of the Catholic Monarchs to extend their dominion to all the kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula, their reign was characterised by religious unification of the peninsula through militant Catholicism. Petitioning the pope for authority, Pope Sixtus IV issued a bull in 1478 to establish a Holy Office of the Inquisition

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy, conducting trials of suspected heretics. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances, ...

in Castile. This was to ensure that Jews and Muslims who converted to Christianity did not revert to their previous faiths. The papal bull gave the sovereigns full powers to name inquisitors, but the papacy retained the right to formally appoint the royal nominees. The inquisition did not have jurisdiction over Jews and Muslims who did not convert. Since in the kingdom of Aragon it had existed since 1248, the Spanish Inquisition was the only common institution for the two kingdoms. Pope Innocent VIII confirmed Dominican Tomás de Torquemada

Tomás de Torquemada (14 October 1420 – 16 September 1498), also anglicized as Thomas of Torquemada, was a Castilian Dominican friar and first Grand Inquisitor of the Tribunal of the Holy Office (otherwise known as the Spanish Inquisition). ...

, a confessor of Isabella, as Grand Inquisitor of Spain, following in the tradition in Aragon of Dominican inquisitors. Torquemada pursued aggressive policies toward converted Jews ('' conversos'') and ''morisco

Moriscos (, ; pt, mouriscos ; Spanish for "Moorish") were former Muslims and their descendants whom the Roman Catholic church and the Spanish Crown commanded to convert to Christianity or face compulsory exile after Spain outlawed the open ...

s''. The pope also granted the Catholic Monarchs the right of patronage over the ecclesiastical establishment in Granada and the Canary Islands, which meant the control of the state in religious affairs.

The monarchs began a series of campaigns known as the Granada War

The Granada War ( es, Guerra de Granada) was a series of military campaigns between 1482 and 1491 during the reign of the Catholic Monarchs, Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon, against the Nasrid dynasty's Emirate of Granada. It e ...

(1482–92), which was aided by Pope Sixtus IV's granting the tithe revenue and implementing a crusade tax so that the monarchs could finance the war. After 10 years of fighting the Granada War ended in 1492 when Emir Boabdil

Abu Abdallah Muhammad XII ( ar, أبو عبد الله محمد الثاني عشر, Abū ʿAbdi-llāh Muḥammad ath-thānī ʿashar) (c. 1460–1533), known in Europe as Boabdil (a Spanish rendering of the name ''Abu Abdallah''), was the ...

surrendered the keys of the Alhambra Palace in Granada to the Castilian soldiers. With the fall of Granada in January 1492, Isabella and Ferdinand pursued further policies of religious unification of their realms, in particular the expulsion of Jews who refused to convert to Christianity.

After a number of revolts, Ferdinand and Isabella ordered the expulsion

Expulsion or expelled may refer to:

General

* Deportation

* Ejection (sports)

* Eviction

* Exile

* Expeller pressing

* Expulsion (education)

* Expulsion from the United States Congress

* Extradition

* Forced migration

* Ostracism

* Persona non ...

of all Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

s from Spain. People who converted to Catholicism were not subject to expulsion, but between 1480 and 1492 hundreds of those who had converted (''conversos'' and ''moriscos'') were accused of secretly practicing their original religion (crypto-Judaism

Crypto-Judaism is the secret adherence to Judaism while publicly professing to be of another faith; practitioners are referred to as "crypto-Jews" (origin from Greek ''kryptos'' – , 'hidden').

The term is especially applied historically to Sp ...

or crypto-Islam

Crypto-Islam is the secret adherence to Islam while publicly professing to be of another faith; people who practice crypto-Islam are referred to as "crypto-Muslims." The word has mainly been used in reference to Spanish Muslims and Sicilian Musli ...

) and arrested, imprisoned, interrogated under torture, and in some cases burned to death, in both Castile and Aragon.

The Inquisition had been created in the twelfth century by Pope Lucius III

Pope Lucius III (c. 1097 – 25 November 1185), born Ubaldo Allucingoli, reigned from 1 September 1181 to his death in 1185. Born of an aristocratic family of Lucca, prior to being elected pope, he had a long career as a papal diplomat. His pa ...

to fight heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

in the south of what is now France and was constituted in a number of European kingdoms. The Catholic Monarchs decided to introduce the Inquisition to Castile, and requested the Pope's assent. On 1 November 1478, Pope Sixtus IV published the papal bull ''Exigit Sinceras Devotionis Affectus'', by which the Inquisition was established in the Kingdom of Castile; it was later extended to all of Spain. The bull gave the monarchs exclusive authority to name the inquisitors.

During the reign of the Catholic Monarchs and long afterwards the Inquisition was active in prosecuting people for violations of Catholic orthodoxy such as crypto-Judaism, heresy, Protestantism, blasphemy, and bigamy. The last trial for crypto-Judaism was held in 1818.

In 1492 the monarchs issued a decree of expulsion of Jews, known formally as the Alhambra Decree, which gave Jews in Spain four months to either convert to Catholicism or leave Spain. Tens of thousands of Jews emigrated to other lands such as Portugal, North Africa, the Low Countries, Italy and the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

.

Foreign policy

Although the Catholic Monarchs pursued a partnership in many matters, because of the histories of their respective kingdoms, they did not always have unified viewpoint in foreign policy. Despite that, they did have a successful expansionist foreign policy due to a number of factors. The victory over the Muslims in Granada allowed Ferdinand to involve himself in policy outside the Iberian peninsula.Edwards, ''The Spain of the Catholic Monarchs'', p. 241 The diplomatic initiative of King Ferdinand continued the traditional policy of the Crown of Aragon, with its interests set in the Mediterranean, with interests in Italy and sought conquests in North Africa. Aragon had a traditional rivalry withFrance

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

, which had been traditional allies with Castile. Castile's foreign interests were focused on the Atlantic, making Castile's funding of the voyage of Columbus an extension of existing interests.

Castile had traditionally had good relations with the neighboring Kingdom of Portugal, and after the Portuguese lost the War of the Castilian Succession

The War of the Castilian Succession was the military conflict contested from 1475 to 1479 for the succession of the Crown of Castile fought between the supporters of Joanna 'la Beltraneja', reputed daughter of the late monarch Henry IV of Castile ...

, Castile and Portugal concluded the Treaty of Alcáçovas. The treaty set boundaries for overseas expansion which were at the time disadvantageous to Castile, but the treaty resolved any further Portuguese claims on the crown of Castile. Portugal did not take advantage of Castile's and Aragon's focus on the reconquest of Granada. Following the reestablishment of good relations, the Catholic Monarchs made two strategic marriages to Portuguese royalty.

The matrimonial policy of the monarchs sought advantageous marriages for their five children, forging royal alliances for the long-term benefit of Spain. Their first-born, a daughter named Isabella

Isabella may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Isabella (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

* Isabella (surname), including a list of people

Places

United States

* Isabella, Alabama, an unincorpor ...

, married Afonso of Portugal, forging important ties between these two neighboring kingdoms that would lead to enduring peace and future alliance. Joanna

Joanna is a feminine given name deriving from from he, יוֹחָנָה, translit=Yôḥānāh, lit=God is gracious. Variants in English include Joan, Joann, Joanne, and Johanna. Other forms of the name in English are Jan, Jane, Janet, Janice ...

, their second daughter, married Philip the Handsome

Philip the Handsome, es, Felipe, french: Philippe, nl, Filips (22 July 1478 – 25 September 1506), also called the Fair, was ruler of the Burgundian Netherlands and titular Duke of Burgundy from 1482 to 1506, as well as the first Habsburg Ki ...

, the son of Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I. This ensured alliance with the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

, a powerful, far-reaching European territory which assured Spain's future political security. Their only son, John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

, married Margaret of Austria, seeking to maintain ties with the Habsburg dynasty, on which Spain relied heavily. Their fourth child, Maria

Maria may refer to:

People

* Mary, mother of Jesus

* Maria (given name), a popular given name in many languages

Place names Extraterrestrial

* 170 Maria, a Main belt S-type asteroid discovered in 1877

* Lunar maria (plural of ''mare''), large, ...

, married Manuel I of Portugal

Manuel I (; 31 May 146913 December 1521), known as the Fortunate ( pt, O Venturoso), was King of Portugal from 1495 to 1521. A member of the House of Aviz, Manuel was Duke of Beja and Viseu prior to succeeding his cousin, John II of Portuga ...

, strengthening the link forged by Isabella's elder sister's marriage. Their fifth child, Catherine

Katherine, also spelled Catherine, and other variations are feminine names. They are popular in Christian countries because of their derivation from the name of one of the first Christian saints, Catherine of Alexandria.

In the early Christ ...

, married Arthur, Prince of Wales and heir to the throne of England, in 1501; he died at the age of 15 a few months later, and she married his younger brother shortly after he became King Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

in 1509. These alliances were not all long lasting, with their only son and heir-apparent John dying young; Catherine was divorced by Henry VIII; and Joanna's husband Philip dying young, with the widowed Joanna deemed mentally unfit to rule.

Under the Catholic Monarchs an efficient army loyal to the Crown was created, commanded by Castilian Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba

Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba (1 September 1453 – 2 December 1515) was a Spanish general and statesman who led successful military campaigns during the Conquest of Granada and the Italian Wars. His military victories and widespread p ...

, known as the ''Great Captain''. Fernández de Córdoba reorganised the military troops on a new combat unit, tercios reales, which entailed the creation of the first modern army dependent on the crown, regardless of pretensions of the nobles.

Voyages of Christopher Columbus

Through the

Through the Capitulations of Santa Fe

The Capitulations of Santa Fe between Christopher Columbus and the Catholic Monarchs, Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon, were signed in Santa Fe, Granada on April 17, 1492. They granted Columbus the titles of admiral ...

, navigator Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

received finances and was authorised to sail west and claim lands for Spain. The monarchs accorded him the title of Admiral of the Ocean Sea and he was given broad privileges. His voyage west resulted in the European colonization of the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

and brought the knowledge of its existence to Europe.

Columbus' first expedition to the supposed Indies actually landed in the Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to 88% of the ar ...

on October 12, 1492. Since Queen Isabella had provided the funding and authorization for the voyage, the benefits accrued to the Kingdom of Castile. "Although the subjects of the Crown of Aragon played some part in the discovery and colonization of the New World, the Indies were formally annexed not to Spain but to the Crown of Castile." Elliott, J.H. ''Imperial Spain 1479–1716''. New York: New American Library 1963. He landed on the island of Guanahani

Guanahaní is an island in the Bahamas that was the first land in the New World sighted and visited by Christopher Columbus' first voyage, on 12 October 1492. It is a bean-shaped island that Columbus changed from its native Taíno name to San ...

, and called it San Salvador. He continued onto Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

, naming it Juana, and finished his journey on the island of the Dominican Republic and Haiti, calling it Hispaniola, or ''La Isla Española'' ("the Spanish sland in Castilian).

On his second trip, begun in 1493, he found more Caribbean islands including Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and unincorporated ...

. His main goal was to colonize the existing discoveries with the 1500 men that he had brought the second time around. Columbus finished his last expedition in 1498, and discovered Trinidad

Trinidad is the larger and more populous of the two major islands of Trinidad and Tobago. The island lies off the northeastern coast of Venezuela and sits on the continental shelf of South America. It is often referred to as the southernmos ...

and the coast of present-day Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in th ...

. The colonies Columbus established, and conquests in the Americas in later decades, generated an influx of wealth into the new unified state of Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

, leading it to be the major power of Europe from the end of the fifteenth century until the mid-seventeenth century, and the largest empire until 1810.

Death

Isabella's death in 1504 ended the remarkably successful political partnership and personal relationship of their marriage. Ferdinand remarried

Isabella's death in 1504 ended the remarkably successful political partnership and personal relationship of their marriage. Ferdinand remarried Germaine of Foix

Ursula Germaine of Foix (french: Ursule-Germaine de Foix; ca, Úrsula Germana de Foix; ; c. 1488 – 15 October 1536) was an early modern French noblewoman from the House of Foix. By marriage to King Ferdinand II of Aragon, she was Queen of Ar ...

in 1505, but they produced no living heir. Had there been one, Aragon would doubtless have been separated from Castile. The Catholic Monarchs' daughter Joanna succeeded to the crown of Castile, but was deemed unfit to rule and following the death of her husband Phillip the Fair, Ferdinand retained power in Castile as regent until his death, with Joanna confined. He died in 1516 and is buried alongside his first wife Isabella in Granada, the scene of their great triumph in 1492. Joanna's son Charles I of Spain

Charles V, french: Charles Quint, it, Carlo V, nl, Karel V, ca, Carles V, la, Carolus V (24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria from 1519 to 1556, King of Spain ( Castile and Aragon) fro ...

(also Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor) came to Spain, and she, kept confined in Tordesillas

Tordesillas () is a town and municipality in the province of Valladolid, Castile and León, central Spain. It is located southwest of the provincial capital, Valladolid at an elevation of . The population was c. 9,000 .

The town is located ...

, was nominal co-ruler of both Castile and Aragon until her death. With her death, Charles succeeded to the territories that his grandparents had accumulated and brought the Habsburg territories in Europe to the expanding Spanish Empire.

See also

*Black Propaganda against Portugal and Spain

The Black Legend ( es, Leyenda negra) or the Spanish Black Legend ( es, Leyenda negra española, link=no) is a theorised historiographical tendency which consists of anti-Spanish and anti-Catholic propaganda. Its proponents argue that its roo ...

*Iberian Union

pt, União Ibérica

, conventional_long_name =Iberian Union

, common_name =

, year_start = 1580

, date_start = 25 August

, life_span = 1580–1640

, event_start = War of the Portuguese Succession

, event_end = Portuguese Restoration War

, ...

* Portuguese Restoration War

Notes

References

Further reading

* Elliott, J.H., ''Imperial Spain, 1469–1716'' (1963; Pelican 1970) * Edwards, John. ''Ferdinand and Isabella: Profiles in Power.''Pearson Education. New York, New York. 2005. . * Edwards, John. ''The Spain of the Catholic Monarchs.'' Blackwell Publishers. Massachusetts, 2000. . * Kamen, Henry. ''Spain: 1469–1714 A Society of Conflict.'' Taylor & Francis. New York & London. 2014. .External links

Country Studies

{{Authority control * * Married couples Spanish Renaissance people 15th century in Al-Andalus 15th-century Spanish monarchs 16th-century Spanish monarchs Reconquista Spanish Inquisition Spanish colonization of the Americas Spanish Empire Royal styles Founding monarchs Theocrats