Rescue of Jews by Poles during the Holocaust on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Political Migrations on Polish Territories (1939–1950).

'

Messages of Murder: A Study of the Reports of the Einsatzgruppen of the Security Police and the Security Service, 1941–1943.

' Fairleigh Dickinson Univ. Press, pp. 125–126. . National minorities routinely participated in pogroms led by OUN-UPA, YB, TDA and BKA. Local participation in the Nazi German "cleansing" operations included the

An average Jew who survived in occupied Poland depended on many acts of assistance and tolerance, wrote Paulsson. "Nearly every Jew that was rescued, was rescued by the cooperative efforts of dozen or more people," as confirmed also by the Polish-Jewish historian Szymon Datner. Paulsson notes that during the six years of wartime and occupation, the average Jew sheltered by the Poles had three or four sets of false documents and faced recognition as a Jew multiple times. Datner explains also that hiding a Jew lasted often for several years thus increasing the risk involved for each Christian family exponentially. Polish-Jewish writer and Holocaust survivor

An average Jew who survived in occupied Poland depended on many acts of assistance and tolerance, wrote Paulsson. "Nearly every Jew that was rescued, was rescued by the cooperative efforts of dozen or more people," as confirmed also by the Polish-Jewish historian Szymon Datner. Paulsson notes that during the six years of wartime and occupation, the average Jew sheltered by the Poles had three or four sets of false documents and faced recognition as a Jew multiple times. Datner explains also that hiding a Jew lasted often for several years thus increasing the risk involved for each Christian family exponentially. Polish-Jewish writer and Holocaust survivor

Efforts at rescue were encumbered by several factors. The threat of the death penalty for aiding Jews and the limited ability to provide for the escapees were often responsible for the fact that many Poles were unwilling to provide direct help to a person of Jewish origin. This was exacerbated by the fact that the people who were in hiding did not have official ration cards and hence food for them had to be purchased on the black market at high prices. According to

Efforts at rescue were encumbered by several factors. The threat of the death penalty for aiding Jews and the limited ability to provide for the escapees were often responsible for the fact that many Poles were unwilling to provide direct help to a person of Jewish origin. This was exacerbated by the fact that the people who were in hiding did not have official ration cards and hence food for them had to be purchased on the black market at high prices. According to  Michael C. Steinlauf writes that not only the fear of the death penalty was an obstacle limiting Polish aid to Jews, but also antisemitism, which made many individuals uncertain of their neighbors' reaction to their attempts at rescue. Number of authors have noted the negative consequences of the hostility towards Jews by extremists advocating their eventual removal from Poland. Meanwhile, Alina Cala in her study of Jews in Polish folk culture argued also for the persistence of traditional religious antisemitism and anti-Jewish propaganda before and during the war both leading to indifference. Steinlauf however notes that despite these uncertainties, Jews were helped by countless thousands of individual Poles throughout the country. He writes that "not the informing or the indifference, but the existence of such individuals is one of the most remarkable features of Polish-Jewish relations during the Holocaust."

Michael C. Steinlauf writes that not only the fear of the death penalty was an obstacle limiting Polish aid to Jews, but also antisemitism, which made many individuals uncertain of their neighbors' reaction to their attempts at rescue. Number of authors have noted the negative consequences of the hostility towards Jews by extremists advocating their eventual removal from Poland. Meanwhile, Alina Cala in her study of Jews in Polish folk culture argued also for the persistence of traditional religious antisemitism and anti-Jewish propaganda before and during the war both leading to indifference. Steinlauf however notes that despite these uncertainties, Jews were helped by countless thousands of individual Poles throughout the country. He writes that "not the informing or the indifference, but the existence of such individuals is one of the most remarkable features of Polish-Jewish relations during the Holocaust."  Former Director of the Department of the Righteous at

Former Director of the Department of the Righteous at

In an attempt to discourage Poles from helping the Jews and to destroy any efforts of the resistance, the Germans applied a ruthless retaliation policy.

On 10 November 1941, the death penalty was introduced by

In an attempt to discourage Poles from helping the Jews and to destroy any efforts of the resistance, the Germans applied a ruthless retaliation policy.

On 10 November 1941, the death penalty was introduced by

In Poland's cities and larger towns, the Nazi occupiers created

In Poland's cities and larger towns, the Nazi occupiers created

Several organizations dedicated to saving Jews were created and run by Christian Poles with the help of the Polish Jewish underground. Among those, ''

Several organizations dedicated to saving Jews were created and run by Christian Poles with the help of the Polish Jewish underground. Among those, ''

The supreme political body of the underground government within Poland was the Delegatura Rządu Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej na Kraj, Delegatura. There were no Jewish representatives in it. Delegatura financed and sponsored ''

The supreme political body of the underground government within Poland was the Delegatura Rządu Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej na Kraj, Delegatura. There were no Jewish representatives in it. Delegatura financed and sponsored ''

"Righteous Among the Nations: Henryk Sławik and József Antall."

''Museum of the History of Polish Jews.'' Warsaw, 7 October 2010. ''See also:'

"The Sławik family" (ibidem).

Accessed 3 September 2011. With two members on the National Council, Polish Jews were sufficiently represented in the government in exile. Also, in 1943 a Jewish affairs section of the Underground State was set up by the Poland, with its unique underground state, was the only country in occupied Europe to have an extensive, underground justice system. These clandestine courts operated with attention to due process (although limited by circumstances), so it could take months to get a death sentence passed. However, Prekerowa notes that the death sentences by non-military courts only began to be issued in September 1943, which meant that blackmailers were able to operate for some time already since the first Nazi anti-Jewish measures of 1940. Overall, it took the Polish underground until late 1942 to legislate and organize non-military courts which were authorized to pass death sentences for civilian crimes, such as non-treasonous collaboration, extortion and blackmail. According to Joseph Kermish from Israel, among the thousands of collaborators sentenced to death by the Underground courts and executed by the Polish resistance fighters who risked death carrying out these verdicts, few were explicitly blackmailers or informers who had persecuted Jews. This, according to Kermish, led to increasing boldness of some of the blackmailers in their criminal activities. Marek Jan Chodakiewicz writes that a number of Polish Jews were executed for denouncing other Jews. He notes that since Nazi informers often denounced members of the underground as well as Jews in hiding, the charge of collaboration was a general one and sentences passed were for cumulative crimes.

The Home Army units under the command of officers from left-wing Sanacja, the Polish Socialist Party as well as the centrist Democratic Party (Poland), Democratic Party welcomed Jewish fighters to serve with Poles without problems stemming from their ethnic identity. However, some rightist units of the Armia Krajowa excluded Jews. Similarly, some members of the Delegate's Bureau saw Jews and ethnic Poles as separate entities. Historian

Poland, with its unique underground state, was the only country in occupied Europe to have an extensive, underground justice system. These clandestine courts operated with attention to due process (although limited by circumstances), so it could take months to get a death sentence passed. However, Prekerowa notes that the death sentences by non-military courts only began to be issued in September 1943, which meant that blackmailers were able to operate for some time already since the first Nazi anti-Jewish measures of 1940. Overall, it took the Polish underground until late 1942 to legislate and organize non-military courts which were authorized to pass death sentences for civilian crimes, such as non-treasonous collaboration, extortion and blackmail. According to Joseph Kermish from Israel, among the thousands of collaborators sentenced to death by the Underground courts and executed by the Polish resistance fighters who risked death carrying out these verdicts, few were explicitly blackmailers or informers who had persecuted Jews. This, according to Kermish, led to increasing boldness of some of the blackmailers in their criminal activities. Marek Jan Chodakiewicz writes that a number of Polish Jews were executed for denouncing other Jews. He notes that since Nazi informers often denounced members of the underground as well as Jews in hiding, the charge of collaboration was a general one and sentences passed were for cumulative crimes.

The Home Army units under the command of officers from left-wing Sanacja, the Polish Socialist Party as well as the centrist Democratic Party (Poland), Democratic Party welcomed Jewish fighters to serve with Poles without problems stemming from their ethnic identity. However, some rightist units of the Armia Krajowa excluded Jews. Similarly, some members of the Delegate's Bureau saw Jews and ethnic Poles as separate entities. Historian

Google Print, p. 107-123

in Joshua D. Zimmerman, ''Contested Memories: Poles and Jews During the Holocaust and Its Aftermath'', Rutgers University Press, 2003, * * * Tec, Nechama. ''When Light Pierced the Darkness: Christian Rescue of Jews in Nazi-Occupied Poland'', Oxford University Press US, 1987,

Google Print

* Tomaszewski, Irene. Werbowski, Tecia. ''Zegota: The Rescue of Jews in Wartime Poland'', Price-Patterson, 1994, * {{DEFAULTSORT:Rescue Of Jews By Poles During The Holocaust The Holocaust in Poland Rescue of Jews during the Holocaust Rescue of Jews by Poles in occupied Poland in 1939-1945

Polish Jews

The history of the Jews in Poland dates back at least 1,000 years. For centuries, Poland was home to the largest and most significant Ashkenazi Jewish community in the world. Poland was a principal center of Jewish culture, because of the l ...

were the primary victims of the German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

-organized Holocaust in Poland

The Holocaust in Poland was part of the European-wide Holocaust organized by Nazi Germany and took place in German-occupied Poland. During the genocide, three million Polish Jews were murdered, half of all Jews murdered during the Holocaust.

...

. Throughout the German occupation of Poland

Occupation commonly refers to:

* Occupation (human activity), or job, one's role in society, often a regular activity performed for payment

*Occupation (protest), political demonstration by holding public or symbolic spaces

*Military occupation, t ...

, many Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland in C ...

rescued Jews from the Holocaust, in the process risking their lives – and the lives of their families. Poles were, by nationality, the most numerous persons who rescued Jews during the Holocaust. To date, ethnic Poles have been recognized by the State of Israel as Righteous among the Nations

Righteous Among the Nations ( he, חֲסִידֵי אֻמּוֹת הָעוֹלָם, ; "righteous (plural) of the world's nations") is an honorific used by the State of Israel to describe non-Jews who risked their lives during the Holocaust to sa ...

– more, by far, than the citizens of any other country.

The Home Army

The Home Army ( pl, Armia Krajowa, abbreviated AK; ) was the dominant resistance movement in German-occupied Poland during World War II. The Home Army was formed in February 1942 from the earlier Związek Walki Zbrojnej (Armed Resistance) est ...

(the Polish Resistance) alerted the world to the Holocaust through the reports of Polish Army officer Witold Pilecki

Witold Pilecki (13 May 190125 May 1948; ; codenames ''Roman Jezierski, Tomasz Serafiński, Druh, Witold'') was a Polish World War II cavalry officer, intelligence agent, and resistance leader.

As a youth, Pilecki joined Polish underground s ...

, conveyed by Polish government-in-exile

The Polish government-in-exile, officially known as the Government of the Republic of Poland in exile ( pl, Rząd Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej na uchodźstwie), was the government in exile of Poland formed in the aftermath of the Invasion of Pola ...

courier Jan Karski

Jan Karski (24 June 1914 – 13 July 2000) was a Polish soldier, resistance-fighter, and diplomat during World War II. He is known for having acted as a courier in 1940–1943 to the Polish government-in-exile and to Poland's Western Allies ab ...

. The Polish government-in-exile and the Polish Secret State

The Polish Underground State ( pl, Polskie Państwo Podziemne, also known as the Polish Secret State) was a single political and military entity formed by the union of resistance organizations in occupied Poland that were loyal to the Gover ...

pleaded, to no avail, for American and British help to stop the Holocaust.

The rescue efforts were aided by one of the largest resistance movements

A resistance movement is an organized effort by some portion of the civil population of a country to withstand the legally established government or an occupying power and to disrupt civil order and stability. It may seek to achieve its objectives ...

in Europe, the Polish Underground State and its military arm, the Home Army

The Home Army ( pl, Armia Krajowa, abbreviated AK; ) was the dominant resistance movement in German-occupied Poland during World War II. The Home Army was formed in February 1942 from the earlier Związek Walki Zbrojnej (Armed Resistance) est ...

. Supported by the Government Delegation for Poland

The Government Delegation for Poland ( pl, Delegatura Rządu Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej na Kraj) was an agency of the Polish Government in Exile during World War II. It was the highest authority of the Polish Secret State in occupied Poland and was ...

, the most notable effort dedicated to helping Jews was spearheaded by the Żegota

Żegota (, full codename: the "Konrad Żegota Committee"Yad Vashem Shoa Resource CenterZegota/ref>) was the Polish Council to Aid Jews with the Government Delegation for Poland ( pl, Rada Pomocy Żydom przy Delegaturze Rządu RP na Kraj), an un ...

Council, based in Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officia ...

, with branches in Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

, Wilno

Vilnius ( , ; see also #Etymology and other names, other names) is the capital and List of cities in Lithuania#Cities, largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the munic ...

, and Lwów.

Polish rescuers were hampered by the murderous conditions of the German occupation. Any kind of help to Jews was punishable by death, for the rescuer and the rescuer's family. Of the estimated 3 million non-Jewish Poles killed in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, thousands were executed by the Germans solely for saving Jews.

Background

Before World War II, 3,300,000 Jewish people lived in Poland – ten percent of the general population of some 33 million. Poland was the center of the European Jewish world. The Second World War began with the Germaninvasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week aft ...

on 1 September 1939; and, on 17 September, in accordance with the Molotov-Ribbentrop agreement, the Soviet Union invaded Poland from the east. By October 1939, the Second Polish Republic was split in half between two totalitarian powers. Germany occupied 48.4 percent of western and central Poland.Piotr Eberhardt

Piotr Eberhardt (December 27, 1935 – September 10, 2020) was a Polish geographer, a professor at the Polish Academy of Science and author of studies in the field of demography and population geography. His works included the ethnic problems of Ce ...

(2011), Political Migrations on Polish Territories (1939–1950).

'

Polish Academy of Sciences

The Polish Academy of Sciences ( pl, Polska Akademia Nauk, PAN) is a Polish state-sponsored institution of higher learning. Headquartered in Warsaw, it is responsible for spearheading the development of science across the country by a society o ...

; Stanisław Leszczycki Institute, Monographies; 12, pp. 25–29; via Internet Archive. Racial policy of Nazi Germany regarded Poles as " sub-human" and Polish Jews beneath that category, validating a campaign of unrestricted violence. One aspect of German foreign policy in conquered Poland was to prevent its ethnically diverse population from uniting against Germany. The Nazi plan for Polish Jews was one of concentration, isolation, and eventually total annihilation in the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

also known as the ''Shoah''. Similar policy measures toward the Polish Catholic majority focused on the murder or suppression of political, religious, and intellectual leaders as well as the Germanization of the annexed lands which included a program to resettle ethnic Germans from the Baltic states and other regions onto farms, ventures and homes formerly owned by the expelled Poles including Polish Jews.

The response of the Polish majority to the Jewish Holocaust covered an extremely wide spectrum, often ranging from acts of altruism at the risk of endangering their own and their families lives, through compassion, to passivity, indifference, blackmail, and denunciation. Polish rescuers faced threats from unsympathetic neighbours, the Polish-German ''Volksdeutsche

In Nazi German terminology, ''Volksdeutsche'' () were "people whose language and culture had German origins but who did not hold German citizenship". The term is the nominalised plural of '' volksdeutsch'', with ''Volksdeutsche'' denoting a sin ...

'', the ethnic Ukrainian pro-Nazis, as well as blackmailers called szmalcownik

Szmalcownik (); in English, also sometimes spelled shmaltsovnik) is a pejorative Polish slang expression that originated during the Holocaust in Poland in World War II and refers to a person who blackmailed Jews who were in hiding, or who ...

s, along with the Jewish collaborators from Żagiew

Żagiew ("The Torch", ''Die Fackel''), also known as Żydowska Gwardia Wolności (the "Jewish Freedom Guard"), was a Nazi-collaborationist Jewish agent-provocateur group in German-occupied Poland, founded and sponsored by the Germans and led by ...

and Group 13

The Group 13 network ( pl, Trzynastka, Yiddish: ''דאָס דרײַצענטל'') was a Jewish Nazi collaborationist organization in the Warsaw Ghetto during the German occupation of Poland in World War II. The rise and fall of the Group ...

. The Catholic saviors of Jews were also betrayed under duress by the Jews in hiding following capture by the German Order Police battalions

The Order Police battalions were militarised formations of the German Order Police (uniformed police) during the Nazi era. During World War II, they were subordinated to the SS and deployed in German-occupied areas, specifically the Army Grou ...

and the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one orga ...

, which resulted in the Nazi murder of the entire networks of Polish helpers.

In 1941, at the onset of Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named after ...

, the invasion of the Soviet Union, the main architect of the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

, Reinhard Heydrich

Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich ( ; ; 7 March 1904 – 4 June 1942) was a high-ranking German SS and police official during the Nazi era and a principal architect of the Holocaust.

He was chief of the Reich Security Main Office (inclu ...

, issued his operational guidelines for the mass anti-Jewish actions carried out with the participation of local gentiles. Massacres of Polish Jews by the Ukrainian and Lithuanian auxiliary police battalions followed. Deadly pogroms were committed in over 30 locations across formerly Soviet-occupied parts of Poland, including in Brześć

Brest ( be, Брэст / Берасьце, Bieraście, ; russian: Брест, ; uk, Берестя, Berestia; lt, Brasta; pl, Brześć; yi, בריסק, Brisk), formerly Brest-Litovsk (russian: Брест-Литовск, lit=Lithuanian Br ...

, Tarnopol

Ternópil ( uk, Тернопіль, Ternopil' ; pl, Tarnopol; yi, טאַרנאָפּל, Tarnopl, or ; he, טארנופול (טַרְנוֹפּוֹל), Tarnopol; german: Tarnopol) is a city in the west of Ukraine. Administratively, Ternopi ...

, Białystok, Łuck

Lutsk ( uk, Луцьк, translit=Lutsk}, ; pl, Łuck ; yi, לוצק, Lutzk) is a city on the Styr River in northwestern Ukraine. It is the administrative center of the Volyn Oblast (province) and the administrative center of the surrounding L ...

, Lwów, Stanisławów, and in Wilno

Vilnius ( , ; see also #Etymology and other names, other names) is the capital and List of cities in Lithuania#Cities, largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the munic ...

where the Jews were murdered along with the Poles in the Ponary massacre

, location = Paneriai (Ponary), Vilnius (Wilno), Reichskommissariat Ostland

, coordinates =

, date = July 1941 – August 1944

, incident_type = Shootings by automatic and semi-automatic weapons,

genocide

, perpetrators ...

at a ratio of 3-to-1.Ronald Headland (1992), Messages of Murder: A Study of the Reports of the Einsatzgruppen of the Security Police and the Security Service, 1941–1943.

' Fairleigh Dickinson Univ. Press, pp. 125–126. . National minorities routinely participated in pogroms led by OUN-UPA, YB, TDA and BKA. Local participation in the Nazi German "cleansing" operations included the

Jedwabne pogrom

The Jedwabne pogrom was a massacre of Polish Jews in the town of Jedwabne, German-occupied Poland, on 10 July 1941, during World War II and the early stages of the Holocaust. At least 340 men, women and children were murdered, some 300 of whom ...

of 1941. The '' Einsatzkommandos'' were ordered to organize them in all eastern territories occupied by Germany. Less than one tenth of 1 per cent of native Poles collaborated, according to statistics of the Israeli War Crimes Commission.

Ethnic Poles assisted Jews by organized as well as by individual efforts. Many Poles offered food to Polish Jews or left it in places Jews would pass on their way to forced labor. Other Poles directed Jewish ghetto

A ghetto, often called ''the'' ghetto, is a part of a city in which members of a minority group live, especially as a result of political, social, legal, environmental or economic pressure. Ghettos are often known for being more impoverished t ...

escapees to Poles who could help them. Some Poles sheltered Jews for only one or a few nights; others assumed full responsibility for their survival, fully aware that the Germans punished by summary execution those (as well as their families) who helped Jews.

A special role fell to Polish physicians who saved thousands of Jews. Dr.

Doctor is an academic title that originates from the Latin word of the same spelling and meaning. The word is originally an agentive noun of the Latin verb 'to teach'. It has been used as an academic title in Europe since the 13th century, w ...

Eugeniusz Łazowski, known as the "Polish Schindler", saved 8,000 Polish Jews in Rozwadów

Rozwadów () is a suburb of Stalowa Wola, Poland. Founded as a town in 1690, it was incorporated into Stalowa Wola in 1973. The Rozwadów suburb of Stalowa Wola included a thriving Jewish shtetl prior to World War II, closely associated with ...

from deportation to death camps by simulating a typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure. ...

epidemic. Dr. Tadeusz Pankiewicz

Tadeusz Pankiewicz (November 21, 1908, in Sambor – November 5, 1993, buried in Kraków), was a Polish Roman Catholic pharmacist, operating in the Kraków Ghetto during the Nazi German occupation of Poland. He was recognized as "Righteous ...

gave out free medicines in the Kraków Ghetto

The Kraków Ghetto was one of five major metropolitan Nazi ghettos created by Germany in the new General Government territory during the German occupation of Poland in World War II. It was established for the purpose of exploitation, terror, and ...

, saving an unspecified number of Jews. Professor Rudolf Weigl

Rudolf Stefan Jan Weigl (2 September 1883 – 11 August 1957) was a Polish biologist, physician and inventor, known for creating the first effective vaccine

A vaccine is a biological preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a ...

, inventor of the first effective vaccine

A vaccine is a biological preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious or malignant disease. The safety and effectiveness of vaccines has been widely studied and verified.

against epidemic typhus, employed and protected Jews in his Weigl Institute in Lwów; his vaccines were smuggled into the Lwów and Warsaw Ghetto

The Warsaw Ghetto (german: Warschauer Ghetto, officially , "Jewish Residential District in Warsaw"; pl, getto warszawskie) was the largest of the Nazi ghettos during World War II and the Holocaust. It was established in November 1940 by the G ...

s, saving countless lives. Dr. Tadeusz Kosibowicz, director of the state hospital in Będzin

Będzin (; also ''Bendzin'' in English; german: Bendzin; yi, בענדין, Bendin) is a city in the Dąbrowa Basin, in southern Poland. It lies in the Silesian Highlands, on the Czarna Przemsza River (a tributary of the Vistula). Even though pa ...

, was sentenced to death for rescuing Jewish fugitives (but the sentence was commuted to camp imprisonment, and he survived the war).

Those who took full responsibility for Jews' survival, perhaps especially, merit recognition as Righteous among the Nations

Righteous Among the Nations ( he, חֲסִידֵי אֻמּוֹת הָעוֹלָם, ; "righteous (plural) of the world's nations") is an honorific used by the State of Israel to describe non-Jews who risked their lives during the Holocaust to sa ...

. 6,066 Poles have been recognized by Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

's Yad Vashem

Yad Vashem ( he, יָד וַשֵׁם; literally, "a memorial and a name") is Israel's official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust. It is dedicated to preserving the memory of the Jews who were murdered; honoring Jews who fought against th ...

as Polish Righteous among the Nations

The citizens of Poland have the world's highest count of individuals who have been recognized by Yad Vashem of Jerusalem as the Polish Righteous Among the Nations, for saving Jews from extermination during the Holocaust in World War II. There ...

for saving Jews during the Jewish Holocaust, making Poland the country with the highest number of such Righteous.

Statistics

The number of Poles who rescued Jews from the Nazi German persecution would be hard to determine in black-and-white terms and is still the subject of scholarly debate. According to Gunnar S. Paulsson, the number of rescuers that meetYad Vashem

Yad Vashem ( he, יָד וַשֵׁם; literally, "a memorial and a name") is Israel's official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust. It is dedicated to preserving the memory of the Jews who were murdered; honoring Jews who fought against th ...

's criteria is perhaps 100,000 and there may have been two or three times as many who offered minor help; the majority "were passively protective." In an article published in the ''Journal of Genocide Research

The ''Journal of Genocide Research'' is a quarterly peer-reviewed academic journal covering studies of genocide. Established in 1999, for the first six years it was not peer-reviewed. Since December 2005, it is the official journal of the Interna ...

'', Hans G. Furth estimated that there may have been as many as 1,200,000 Polish rescuers. Richard C. Lukas estimated that upwards of 1,000,000 Poles were involved in such rescue efforts, "but some estimates go as high as three million." Lukas also cites Władysław Bartoszewski

Władysław Bartoszewski (; 19 February 1922 – 24 April 2015) was a Polish politician, social activist, journalist, writer and historian. A former Auschwitz concentration camp prisoner, he was a World War II resistance fighter as part of th ...

, a wartime member of ''Żegota

Żegota (, full codename: the "Konrad Żegota Committee"Yad Vashem Shoa Resource CenterZegota/ref>) was the Polish Council to Aid Jews with the Government Delegation for Poland ( pl, Rada Pomocy Żydom przy Delegaturze Rządu RP na Kraj), an un ...

'', as having estimated that "at least several hundred thousand Poles ... participated in various ways and forms in the rescue action." Elsewhere, Bartoszewski has estimated that between 1 and 3 percent of the Polish population was actively involved in rescue efforts; Marcin Urynowicz estimates that a minimum of from 500,000 to over a million Poles actively tried to help Jews. The lower number was proposed by Teresa Prekerowa who claimed that between 160,000 and 360,000 Poles assisted in hiding Jews, amounting to between 1% and 2.5% of the 15 million adult Poles she categorized as "those who could offer help." Her estimation counts only those who were involved in hiding Jews directly. It also assumes that each Jew who hid among the non-Jewish populace stayed throughout the war in only one hiding place and as such had only one set of helpers. However, other historians indicate that a much higher number was involved. Paulsson wrote that, according to his research, an average Jew in hiding stayed in seven different places throughout the war.

An average Jew who survived in occupied Poland depended on many acts of assistance and tolerance, wrote Paulsson. "Nearly every Jew that was rescued, was rescued by the cooperative efforts of dozen or more people," as confirmed also by the Polish-Jewish historian Szymon Datner. Paulsson notes that during the six years of wartime and occupation, the average Jew sheltered by the Poles had three or four sets of false documents and faced recognition as a Jew multiple times. Datner explains also that hiding a Jew lasted often for several years thus increasing the risk involved for each Christian family exponentially. Polish-Jewish writer and Holocaust survivor

An average Jew who survived in occupied Poland depended on many acts of assistance and tolerance, wrote Paulsson. "Nearly every Jew that was rescued, was rescued by the cooperative efforts of dozen or more people," as confirmed also by the Polish-Jewish historian Szymon Datner. Paulsson notes that during the six years of wartime and occupation, the average Jew sheltered by the Poles had three or four sets of false documents and faced recognition as a Jew multiple times. Datner explains also that hiding a Jew lasted often for several years thus increasing the risk involved for each Christian family exponentially. Polish-Jewish writer and Holocaust survivor Hanna Krall

Hanna Krall (born 1935), is a Polish writer with a degree in journalism from the University of Warsaw, specializing among other subjects in the history of the Holocaust in occupied Poland.

Personal life

Krall is of Jewish origin, the daughter of ...

has identified 45 Poles who helped to shelter her from the Nazis and Władysław Szpilman

Władysław Szpilman (; 5 December 1911 – 6 July 2000) was a Polish pianist and classical composer of Jewish descent. Szpilman is widely known as the central figure in the 2002 Roman Polanski film '' The Pianist'', which was based on Szpilman ...

, the Jewish Polish musician whose wartime experiences were chronicled in his memoir '' The Pianist'' and the film of the same title identified 30 Poles who helped him to survive the Holocaust.

Meanwhile, Father John T. Pawlikowski from Chicago, referring to work by other historians, speculated that claims of hundreds of thousands of rescuers struck him as inflated. Likewise, Martin Gilbert

Sir Martin John Gilbert (25 October 1936 – 3 February 2015) was a British historian and honorary Fellow of Merton College, Oxford. He was the author of eighty-eight books, including works on Winston Churchill, the 20th century, and Jewish h ...

has written that under Nazi regime, rescuers were an exception, albeit one that could be found in towns and villages throughout Poland.

There is no official number of how many Polish Jews were hidden by their Christian countrymen during wartime. Lukas estimated that the number of Jews sheltered by Poles at one time might have been "as high as 450,000." However, concealment did not automatically assure complete safety from the Nazis, and the number of Jews in hiding who were caught has been estimated variously from 40,000 to 200,000.

Difficulties

Efforts at rescue were encumbered by several factors. The threat of the death penalty for aiding Jews and the limited ability to provide for the escapees were often responsible for the fact that many Poles were unwilling to provide direct help to a person of Jewish origin. This was exacerbated by the fact that the people who were in hiding did not have official ration cards and hence food for them had to be purchased on the black market at high prices. According to

Efforts at rescue were encumbered by several factors. The threat of the death penalty for aiding Jews and the limited ability to provide for the escapees were often responsible for the fact that many Poles were unwilling to provide direct help to a person of Jewish origin. This was exacerbated by the fact that the people who were in hiding did not have official ration cards and hence food for them had to be purchased on the black market at high prices. According to Emmanuel Ringelblum

Emanuel Ringelblum (November 21, 1900 – March 10 (most likely), 1944) was a Polish historian, politician and social worker, known for his ''Notes from the Warsaw Ghetto'', ''Notes on the Refugees in Zbąszyn'' chronicling the deportation of Jew ...

in most cases the money that Poles accepted from Jews they helped to hide, was taken not out of greed, but out of poverty which Poles had to endure during the German occupation. Israel Gutman

Israel Gutman ( he, ישראל גוטמן; 20 May 1923 – 1 October 2013) was a Polish-born Israeli historian and a survivor of the Holocaust.

Biography

Israel (Yisrael) Gutman was born in Warsaw, Second Polish Republic. After participati ...

has written that the majority of Jews who were sheltered by Poles paid for their own up-keep, but thousands of Polish protectors perished along with the people they were hiding.

There is general consensus among scholars that, unlike in Western Europe, Polish collaboration with the Nazi Germans was insignificant. However, the Nazi terror combined with the inadequacy of food rations, as well as German greed, along with the system of corruption as the only "one language the Germans understood well," wrecked traditional values. Poles helping Jews faced unparalleled dangers not only from the German occupiers but also from their own ethnically diverse countrymen including Polish-German ''Volksdeutsche

In Nazi German terminology, ''Volksdeutsche'' () were "people whose language and culture had German origins but who did not hold German citizenship". The term is the nominalised plural of '' volksdeutsch'', with ''Volksdeutsche'' denoting a sin ...

'', and Polish Ukrainians

Ukrainians ( uk, Українці, Ukraintsi, ) are an East Slavic ethnic group native to Ukraine. They are the seventh-largest nation in Europe. The native language of the Ukrainians is Ukrainian. The majority of Ukrainians are Eastern Ort ...

, many of whom were anti-Semitic and morally disoriented by the war. There were people, the so-called szmalcownicy ("shmalts people" from ''shmalts'' or ''szmalec'', slang term for money), who blackmailed the hiding Jews and Poles helping them, or who turned the Jews to the Germans for a reward. Outside the cities there were peasants of various ethnic backgrounds looking for Jews hiding in the forests, to demand money from them. There were also Jews turning in other Jews and ethnic Poles in order to alleviate hunger with the awarded prize. The vast majority of these individuals joined the criminal underworld after the German occupation and were responsible for the deaths of tens of thousands of people, both Jews and the Poles who were trying to save them.

According to one reviewer of Paulsson, with regard to the extortionists, "a single hooligan or blackmailer could wreak severe damage on Jews in hiding, but it took the silent passivity of a whole crowd to maintain their cover." He also notes that "hunters" were outnumbered by "helpers" by a ratio of one to 20 or 30. According to Lukas the number of renegades who blackmailed and denounced Jews and their Polish protectors probably did not number more than 1,000 individuals out of the 1,300,000 people living in Warsaw in 1939.

Michael C. Steinlauf writes that not only the fear of the death penalty was an obstacle limiting Polish aid to Jews, but also antisemitism, which made many individuals uncertain of their neighbors' reaction to their attempts at rescue. Number of authors have noted the negative consequences of the hostility towards Jews by extremists advocating their eventual removal from Poland. Meanwhile, Alina Cala in her study of Jews in Polish folk culture argued also for the persistence of traditional religious antisemitism and anti-Jewish propaganda before and during the war both leading to indifference. Steinlauf however notes that despite these uncertainties, Jews were helped by countless thousands of individual Poles throughout the country. He writes that "not the informing or the indifference, but the existence of such individuals is one of the most remarkable features of Polish-Jewish relations during the Holocaust."

Michael C. Steinlauf writes that not only the fear of the death penalty was an obstacle limiting Polish aid to Jews, but also antisemitism, which made many individuals uncertain of their neighbors' reaction to their attempts at rescue. Number of authors have noted the negative consequences of the hostility towards Jews by extremists advocating their eventual removal from Poland. Meanwhile, Alina Cala in her study of Jews in Polish folk culture argued also for the persistence of traditional religious antisemitism and anti-Jewish propaganda before and during the war both leading to indifference. Steinlauf however notes that despite these uncertainties, Jews were helped by countless thousands of individual Poles throughout the country. He writes that "not the informing or the indifference, but the existence of such individuals is one of the most remarkable features of Polish-Jewish relations during the Holocaust." Nechama Tec

Nechama Tec (née Bawnik) (born 15 May 1931) is a Professor Emerita of Sociology at the University of Connecticut. She received her Ph.D. in sociology at Columbia University, where she studied and worked with the sociologist Daniel Bell, and ...

, who herself survived the war aided by a group of Catholic Poles, noted that Polish rescuers worked within an environment that was hostile to Jews and unfavorable to their protection, in which rescuers feared both the disapproval of their neighbors and reprisals that such disapproval might bring. Tec also noted that Jews, for many complex and practical reasons, were not always prepared to accept assistance that was available to them. Some Jews were pleasantly surprised to have been aided by people whom they thought to have expressed antisemitic attitudes before the invasion of Poland.

Yad Vashem

Yad Vashem ( he, יָד וַשֵׁם; literally, "a memorial and a name") is Israel's official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust. It is dedicated to preserving the memory of the Jews who were murdered; honoring Jews who fought against th ...

, Mordecai Paldiel, wrote that the widespread revulsion among the Polish people at the murders being committed by the Nazis was sometimes accompanied by an alleged feeling of relief at the disappearance of Jews. Israeli historian Joseph Kermish (born 1907) who left Poland in 1950, had claimed at the Yad Vashem conference in 1977, that the Polish researchers overstate the achievements of the Żegota organization (including members of Żegota

Żegota (, full codename: the "Konrad Żegota Committee"Yad Vashem Shoa Resource CenterZegota/ref>) was the Polish Council to Aid Jews with the Government Delegation for Poland ( pl, Rada Pomocy Żydom przy Delegaturze Rządu RP na Kraj), an un ...

themselves, along with venerable historians like Prof. Madajczyk), but his assertions are not supported by the listed evidence. Paulsson and Pawlikowski wrote that wartime attitudes among some of the populace were not a major factor impeding the survival of sheltered Jews, or the work of the ''Żegota'' organization.

The fact that the Polish Jewish community was destroyed during World War II, coupled with stories about Polish collaborators, has contributed, especially among Israelis and American Jews, to a lingering stereotype that the Polish population has been passive in regard to, or even supportive of, Jewish suffering. However, modern scholarship has not validated the claim that Polish antisemitism was irredeemable or different from contemporary Western antisemitism; it has also found that such claims are among the stereotypes that comprise anti-Polonism. The presenting of selective evidence

Cherry picking, suppressing evidence, or the fallacy of incomplete evidence is the act of pointing to individual cases or data that seem to confirm a particular position while ignoring a significant portion of related and similar cases or data th ...

in support of preconceived notions have led some popular press to draw overly simplistic and often misleading conclusions regarding the role played by Poles at the time of the Holocaust.

Punishment for aiding the Jews

In an attempt to discourage Poles from helping the Jews and to destroy any efforts of the resistance, the Germans applied a ruthless retaliation policy.

On 10 November 1941, the death penalty was introduced by

In an attempt to discourage Poles from helping the Jews and to destroy any efforts of the resistance, the Germans applied a ruthless retaliation policy.

On 10 November 1941, the death penalty was introduced by Hans Frank

Hans Michael Frank (23 May 1900 – 16 October 1946) was a German politician and lawyer who served as head of the General Government in Nazi-occupied Poland during the Second World War.

Frank was an early member of the German Workers' Party ...

, governor of the General Government, to apply to Poles who helped Jews "in any way: by taking them in for the night, giving them a lift in a vehicle of any kind" or "feed ngrunaway Jews or sell ngthem foodstuffs." The law was made public by posters distributed in all cities and towns, to instill fear.

The imposition of the death penalty for Poles aiding Jews was unique to Poland among all German-occupied countries and was a result of the conspicuous and spontaneous nature of such an aid. For example, the Ulma family (father, mother and six children) of the village of Markowa

Markowa is a village in Łańcut County, Subcarpathian Voivodeship, in south-eastern Poland. It is the seat of the gmina (administrative district) called Gmina Markowa. It lies approximately south-east of Łańcut and east of the regional ca ...

near Łańcut

Łańcut (, approximately "wine-suit"; yi, לאַנצוט, Lantzut; uk, Ла́ньцут, Lánʹtsut; german: Landshut) is a town in south-eastern Poland, with 18,004 inhabitants, as of 2 June 2009. Situated in the Subcarpathian Voivodeship (si ...

– where many families concealed their Jewish neighbors – were executed jointly by the Nazis with the eight Jews they hid. The entire Wołyniec family in Romaszkańce was massacred for sheltering three Jewish refugees from a ghetto. In Maciuńce, for hiding Jews, the Germans shot eight members of Józef Borowski's family along with him and four guests who happened to be there. Nazi death squads carried out mass executions of the entire villages that were discovered to be aiding Jews on a communal level. In the villages of Białka near Parczew

Parczew is a town in eastern Poland, with a population of 10,281 (2006). It is the capital of Parczew County in the Lublin Voivodeship.

Parczew historically belongs to Lesser Poland (''Małopolska'') region. The town lies 60 kilometers north ...

and Sterdyń near Sokołów Podlaski, 150 villagers were massacred for sheltering Jews.

In November 1942, the Ukrainian SS squad executed 20 villagers from Berecz in Wołyń Voivodeship for giving aid to Jewish escapees from the ghetto in Povorsk. According to Peter Jaroszczak "Michał Kruk and several other people in Przemyśl were executed on September 6, 1943 (''pictured'') for the assistance they had rendered to the Jews. Altogether, in the town and its environs 415 Jews (including 60 children) were saved, in return for which the Germans killed 568 people of Polish nationality." Several hundred Poles were massacred with their priest, Adam Sztark, in Słonim

Slonim ( be, Сло́нім, russian: Сло́ним, lt, Slanimas, lv, Sloņima, pl, Słonim, yi, סלאָנים, ''Slonim'') is a city in Grodno Region, Belarus, capital of the Slonimski rajon. It is located at the junction of the Ščar ...

on 18 December 1942, for sheltering Jewish refugees of the Słonim Ghetto

The Słonim Ghetto ( pl, getto w Słonimiu, be, Слонімскае гета, german: Ghetto von Slonim, yi, סלאָנים) was a Nazi ghetto established in 1941 by the Schutzstaffel, SS in Slonim, Western Belarus during World War II. Prior to ...

in a Catholic church. In Huta Stara near Buczacz, Polish Christians and the Jewish countrymen they protected were herded into a church by the Nazis and burned alive on 4 March 1944. In the years 1942–1944 about 200 peasants were shot dead and burned alive as punishment in the Kielce region alone.

Entire communities that helped to shelter Jews were annihilated, such as the now-extinct village of Huta Werchobuska near Złoczów

Zolochiv ( uk, Золочів, pl, Złoczów, german: Solotschiw, yi, זלאָטשאָוו, ''Zlotshov'') is a small city of district significance in Lviv Oblast of Ukraine, the administrative center of Zolochiv Raion. It hosts the administrat ...

, Zahorze near Łachwa, Huta Pieniacka near Brody

Brody ( uk, Броди; russian: Броды, Brodï; pl, Brody; german: Brody; yi, בראָד, Brod) is a city in Zolochiv Raion of Lviv Oblast (province) of western Ukraine. It is located in the valley of the upper Styr River, approximately ...

or Stara Huta near Szumsk.

Additionally, after the end of the war Poles who saved Jews during the Nazi occupation very often became the victims of repression at the hands of the Communist security apparatus, due to their instinctive devotion to social justice which they saw as being abused by the government.

Richard C. Lukas estimated the number of Poles killed for helping Jews at about 50,000.

Jews in Polish villages

A number of Polish villages in their entirety provided shelter from Nazi apprehension, offering protection for their Jewish neighbors as well as the aid for refugees from other villages and escapees from the ghettos. Postwar research has confirmed that communal protection occurred in Głuchów nearŁańcut

Łańcut (, approximately "wine-suit"; yi, לאַנצוט, Lantzut; uk, Ла́ньцут, Lánʹtsut; german: Landshut) is a town in south-eastern Poland, with 18,004 inhabitants, as of 2 June 2009. Situated in the Subcarpathian Voivodeship (si ...

with everyone engaged, as well as in the villages of Główne, Ozorków

Ozorków ( yi, אוזורקוב, translit=Ozorkov) is a town on the Bzura River in central Poland, with 19,128 inhabitants (2020). It has been situated in the Łódź Voivodeship (Lodz Province) since 1919.

History

The city's history dates ba ...

, Borkowo near Sierpc

Sierpc ( Polish: ) is a town in north-central Poland, in the north-west part of the Masovian Voivodeship, about 125 km northwest of Warsaw. It is the capital of Sierpc County. Its population is 18,791 (2006). It is located near the national ...

, Dąbrowica near Ulanów

Ulanów is a town in Nisko County, Subcarpathian Voivodeship, Poland, with 1,491 inhabitants (02.06.2009).

It has grammar schools and high schools along with 2 churches. One of the churches was set on fire in 2004, and was closed for repairs. A ...

, in Głupianka near Otwock

Otwock is a city in east-central Poland, some southeast of Warsaw, with 44,635 inhabitants (2019). Otwock is a part of the Warsaw Agglomeration. It is situated on the right bank of Vistula River below the mouth of Swider River. Otwock is hom ...

, and Teresin near Chełm

Chełm (; uk, Холм, Kholm; german: Cholm; yi, כעלם, Khelm) is a city in southeastern Poland with 60,231 inhabitants as of December 2021. It is located to the south-east of Lublin, north of Zamość and south of Biała Podlaska, some ...

. In Cisie near Warsaw, 25 Poles were caught hiding Jews; all were killed and the village was burned to the ground as punishment.

The forms of protection varied from village to village. In Gołąbki

Gołąbki is the Polish name of a dish popular in cuisines of Central Europe, made from boiled cabbage leaves wrapped around a filling of minced pork or beef, chopped onions, and rice or barley.

Gołąbki are often served during the Christmas ...

, the farm of Jerzy and Irena Krępeć provided a hiding place for as many as 30 Jews; years after the war, the couple's son recalled in an interview with the ''Montreal Gazette

The ''Montreal Gazette'', formerly titled ''The Gazette'', is the only English-language daily newspaper published in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Three other daily English-language newspapers shuttered at various times during the second half of th ...

'' that their actions were "an open secret in the village hat

A hat is a head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorporate mecha ...

everyone knew they had to keep quiet" and that the other villagers helped, "if only to provide a meal." Another farm couple, Alfreda and Bolesław Pietraszek, provided shelter for Jewish families consisting of 18 people in Ceranów near Sokołów Podlaski, and their neighbors brought food to those being rescued.

Two decades after the end of the war, a Jewish partisan named Gustaw Alef-Bolkowiak identified the following villages in the Parczew

Parczew is a town in eastern Poland, with a population of 10,281 (2006). It is the capital of Parczew County in the Lublin Voivodeship.

Parczew historically belongs to Lesser Poland (''Małopolska'') region. The town lies 60 kilometers north ...

-Ostrów Lubelski

Ostrów Lubelski is a town in Gmina Ostrów Lubelski in Lubartów County, Lublin Voivodeship in Poland.

Geography

Within the territory of the town and commune there are three lakes: Miejskie Lake, Kleszczów Lake and Czarne Lake. The commun ...

area where "almost the entire population" assisted Jews: Rudka, Jedlanka, Makoszka, Tyśmienica, and Bójki. Historians have documented that a dozen villagers of Mętów near Głusk outside Lublin sheltered Polish Jews. In some well-confirmed cases, Polish Jews who were hidden, were circulated between homes in the village. Farmers in Zdziebórz near Wyszków

Wyszków (; yi, ווישקאָוו ''Vishkov'') is a town in eastern Poland with 26,500 inhabitants (2018). It is the capital of Wyszków County in Masovian Voivodeship.

History

The village of Wyszków was first documented in 1203. It was grant ...

sheltered two Jewish men by taking turns. Both of them later joined the Polish underground Home Army

The Home Army ( pl, Armia Krajowa, abbreviated AK; ) was the dominant resistance movement in German-occupied Poland during World War II. The Home Army was formed in February 1942 from the earlier Związek Walki Zbrojnej (Armed Resistance) est ...

. The entire village of Mulawicze near Bielsk Podlaski took responsibility for the survival of an orphaned nine-year-old Jewish boy. Different families took turns hiding a Jewish girl at various homes in Wola Przybysławska near Lublin, and around Jabłoń near Parczew

Parczew is a town in eastern Poland, with a population of 10,281 (2006). It is the capital of Parczew County in the Lublin Voivodeship.

Parczew historically belongs to Lesser Poland (''Małopolska'') region. The town lies 60 kilometers north ...

many Polish Jews successfully sought refuge.

Impoverished Polish Jews, unable to offer any money in return, were nonetheless provided with food, clothing, shelter and money by some small communities; historians have confirmed this took place in the villages of Czajków near Staszów as well as several villages near Łowicz

Łowicz is a town in central Poland with 27,896 inhabitants (2020). It is situated in the Łódź Voivodeship (since 1999); previously, it was in Skierniewice Voivodeship (1975–1998). Together with a nearby station of Bednary, Łowicz is a ma ...

, in Korzeniówka near Grójec

Grójec is a town in Poland, located in the Masovian Voivodeship, about south of Warsaw. It is the capital of the urban-rural administrative district Grójec and Grójec County. It has 16,674 inhabitants (2017). Grójec surroundings are consid ...

, near Żyrardów

Żyrardów is a town and former industrial hub in central Poland with approximately 41,400 inhabitants (2006). It is the capital of Żyrardów County situated in the Masovian Voivodeship (since 1999); previously, it was in Skierniewice Voivodes ...

, in Łaskarzew, and across Kielce Voivodship

Kielce Voivodeship ( pl, województwo kieleckie) is a former unit of administrative division and the local government in Poland. It was originally formed during Poland's return to independence in the aftermath of World War One, and recreated within ...

.

In tiny villages where there was no permanent Nazi military presence, such as Dąbrowa Rzeczycka, Kępa Rzeczycka and Wola Rzeczycka near Stalowa Wola

Stalowa Wola () is the largest city and capital of Stalowa Wola County with a population of 58,545 inhabitants, as of 31 December 2021. It is located in southeastern Poland in the Subcarpathian Voivodeship. The city lies in historic Lesser Polan ...

, some Jews were able to openly participate in the lives of their communities. Olga Lilien, recalling her wartime experience in the 2000 book ''To Save a Life: Stories of Holocaust Rescue'', was sheltered by a Polish family in a village near Tarnobrzeg, where she survived the war despite the posting of a 200 deutsche mark reward by the Nazi occupiers for information on Jews in hiding. Chava Grinberg-Brown from Gmina Wiskitki recalled in a postwar interview that some farmers used the threat of violence against a fellow villager who intimated the desire to betray her safety. Polish-born Israeli writer and Holocaust survivor Natan Gross, in his 2001 book ''Who Are You, Mr. Grymek?'', told of a village near Warsaw where a local Nazi collaborator was forced to flee when it became known he reported the location of a hidden Jew.

Nonetheless, there were cases where Poles who saved Jews were met with a different response after the war. Antonina Wyrzykowska from Janczewko village near Jedwabne managed to successfully shelter seven Jews for twenty-six months from November 1942 until liberation. Sometime earlier, during the Jedwabne pogrom

The Jedwabne pogrom was a massacre of Polish Jews in the town of Jedwabne, German-occupied Poland, on 10 July 1941, during World War II and the early stages of the Holocaust. At least 340 men, women and children were murdered, some 300 of whom ...

close by, a minimum of 300 Polish Jews were burned alive in a barn set on fire by a group of Polish men under the German command. Wyrzykowska was honored as Righteous Among the Nations for her heroism, but left her hometown after liberation for fear of retribution.

Jews in Polish cities

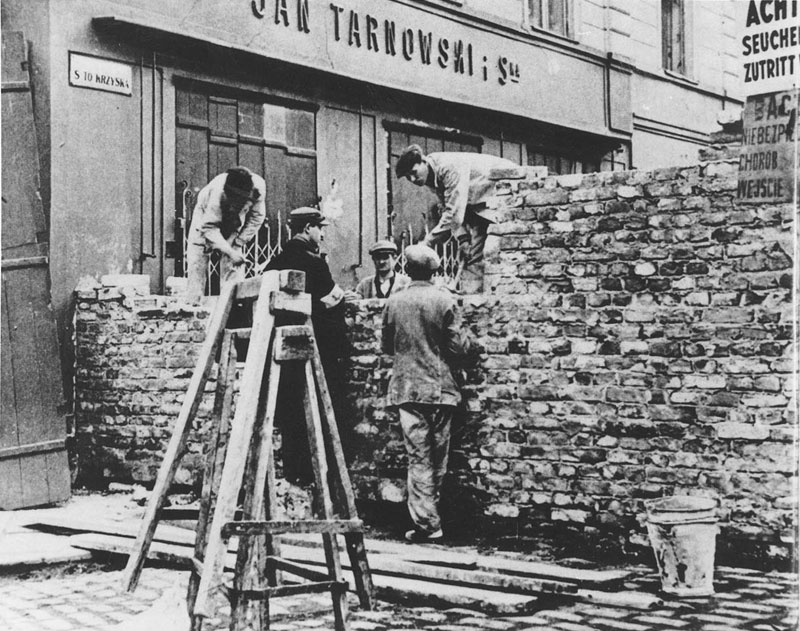

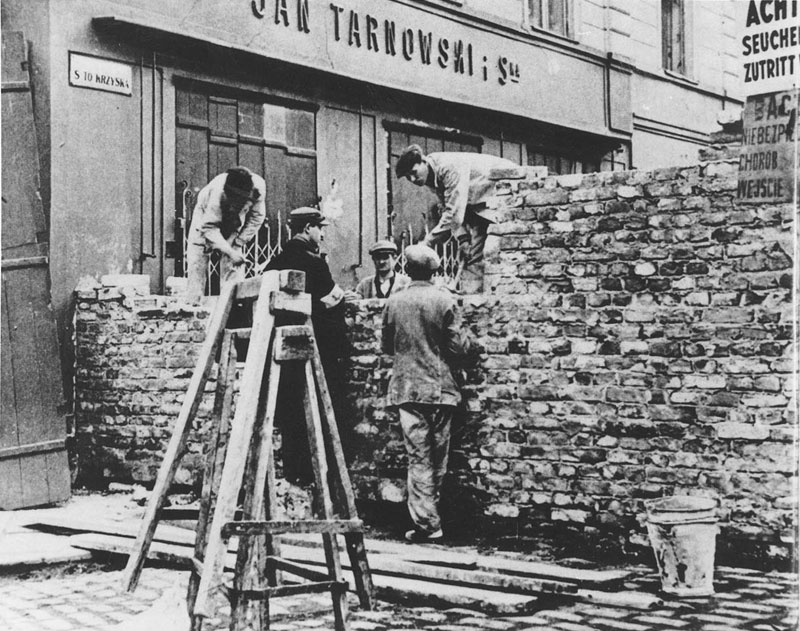

In Poland's cities and larger towns, the Nazi occupiers created

In Poland's cities and larger towns, the Nazi occupiers created ghetto

A ghetto, often called ''the'' ghetto, is a part of a city in which members of a minority group live, especially as a result of political, social, legal, environmental or economic pressure. Ghettos are often known for being more impoverished t ...

s that were designed to imprison the local Jewish populations. The food rations allocated by the Germans to the ghettos condemned their inhabitants to starvation. Smuggling of food into the ghettos and smuggling of goods out of the ghettos, organized by Jews and Poles, was the only means of subsistence of the Jewish population in the ghettos. The price difference between the Ghettos in Nazi-occupied Europe#Aryan side, Aryan and Jewish sides was large, reaching as much as 100%, but the Rescue of Jews by Poles during the Holocaust#Punishment for aiding the Jews, penalty for aiding Jews was death. Hundreds of Polish and Jewish smugglers would come in and out the ghettos, usually at night or at dawn, through openings in the walls, tunnels and sewers or through the guardposts by paying bribes.

The Polish Underground urged the Poles to support smuggling. The punishment for smuggling was death, carried out on the spot. Among the Jewish smuggler victims were scores of Jewish children aged five or six, whom the German shot at the ghetto exits and near the walls. While communal rescue was impossible under these circumstances, many Polish Christians concealed their Jewish neighbors. For example, Zofia Baniecka and her mother rescued over 50 Jews in their home between 1941 and 1944. Paulsson, in his research on the Jews of Warsaw, documented that Warsaw's Polish residents managed to support and conceal the same percentage of Jews as did residents in other European cities under Nazi occupation.

Ten percent of Warsaw's Polish population was actively engaged in sheltering their Jewish neighbors. It is estimated that the number of Jews living in hiding on the Aryan side of the capital city in 1944 was at least 15,000 to 30,000 and relied on the network of 50,000–60,000 Poles who provided shelter, and about half as many assisting in other ways.

Jews outside Poland

Poles living in Lithuania supported Chiune Sugihara producing false Japanese visas. The refugees arriving to Japan were helped by Polish ambassador Tadeusz Romer. Henryk Sławik issued false Polish passports to about 5000 Jews in Hungary. He was killed by Germans in 1944.Ładoś Group

The Ładoś Group also called the Bernese Group (Aleksander Ładoś, Konstanty Rokicki, Stefan Ryniewicz, Juliusz Kühl, Abraham Silberschein, Chaim Eiss) was a group of Poles, Polish diplomats and Jews, Jewish activists who elaborated in Switzerland a system of illegal production of Latin American passports aimed at saving European Jews from Holocaust. Ca 10.000 Jews received such passports, of which over 3000 have been saved. The group efforts are documented in the Eiss Archive.Organizations dedicated to saving Jews

Several organizations dedicated to saving Jews were created and run by Christian Poles with the help of the Polish Jewish underground. Among those, ''

Several organizations dedicated to saving Jews were created and run by Christian Poles with the help of the Polish Jewish underground. Among those, ''Żegota

Żegota (, full codename: the "Konrad Żegota Committee"Yad Vashem Shoa Resource CenterZegota/ref>) was the Polish Council to Aid Jews with the Government Delegation for Poland ( pl, Rada Pomocy Żydom przy Delegaturze Rządu RP na Kraj), an un ...

'', the Council to Aid Jews, was the most prominent. It was unique not only in Poland, but in all of Nazi-occupied Europe, as there was no other organization dedicated solely to that goal. ''Żegota'' concentrated its efforts on saving Jewish children toward whom the Germans were especially cruel. Tadeusz Piotrowski (sociologist), Tadeusz Piotrowski (1998) gives several wide-range estimates of a number of survivors including those who might have received assistance from ''Żegota'' in some form including financial, legal, medical, child care, and other help in times of trouble. The subject is shrouded in controversy according to Szymon Datner, but in Richard C. Lukas, Lukas' estimate about half of those who survived within the changing borders of Poland were helped by ''Żegota''. The number of Jews receiving assistance who did not survive the Holocaust is not known.

Perhaps the most famous member of ''Żegota'' was Irena Sendler, who managed to successfully smuggle 2,500 Jewish children out of the Warsaw Ghetto

The Warsaw Ghetto (german: Warschauer Ghetto, officially , "Jewish Residential District in Warsaw"; pl, getto warszawskie) was the largest of the Nazi ghettos during World War II and the Holocaust. It was established in November 1940 by the G ...

. ''Żegota'' was granted over 5 million dollars or nearly 29 million Polish złoty, zł by the government-in-exile (see below), for the relief payments to Jewish families in Poland. Besides ''Żegota'', there were smaller organizations such as KZ-LNPŻ, ZSP, SOS and others (along the Polish Red Cross), whose action agendas included help to the Jews. Some were associated with ''Żegota''.

Jews and the Church

The Roman Catholic Church in Poland provided many persecuted Jews with food and shelter during the war, even though monasteries gave no immunity to Polish priests and monks against the death penalty. Nearly every Catholic institution in Poland looked after a few Jews, usually children with forged Christian birth certificates and an assumed or vague identity. In particular, convents of Catholic nuns in Poland (see Anna Borkowska (Sister Bertranda), Sister Bertranda), played a major role in the effort to rescue and shelter Polish Jews, with the Franciscan Sisters credited with the largest number of Jewish children saved. Two thirds of all nunneries in Poland took part in the rescue, in all likelihood with the support and encouragement of the church hierarchy. These efforts were supported by local Polish bishops and the Holy See, Vatican itself. The convent leaders never disclosed the exact number of children saved in their institutions, and for security reasons the rescued children were never registered. Jewish institutions have no statistics that could clarify the matter. Systematic recording of testimonies did not begin until the early 1970s. In the villages of Ożarów, Ignaców, Mińsk County, Ignaców, Gmina Leżajsk, Szymanów, and Grodzisko Dolne, Grodzisko near Leżajsk, the Jewish children were cared for by Catholic convents and by the surrounding communities. In these villages, Christian parents did not remove their children from schools where Jewish children were in attendance. Irena Sendler head of children's sectionŻegota

Żegota (, full codename: the "Konrad Żegota Committee"Yad Vashem Shoa Resource CenterZegota/ref>) was the Polish Council to Aid Jews with the Government Delegation for Poland ( pl, Rada Pomocy Żydom przy Delegaturze Rządu RP na Kraj), an un ...

(the Council to Aid Jews) organisation cooperated very closely in saving Jewish children from the Warsaw Ghetto

The Warsaw Ghetto (german: Warschauer Ghetto, officially , "Jewish Residential District in Warsaw"; pl, getto warszawskie) was the largest of the Nazi ghettos during World War II and the Holocaust. It was established in November 1940 by the G ...

with social worker and nun, Catholic nun, mother provincial of Franciscan Sisters of the Family of Mary - Matylda Getter. The children were placed with Polish families, the Warsaw orphanage of the Sisters of the Family of Mary, or Roman Catholic convents such as the Little Sister Servants of the Blessed Virgin Mary Conceived Immaculate at Turkowice, Lublin Voivodeship, Turkowice and Chotomów. Sister Matylda Getter rescued between 250 and 550 Jewish children in different education and care facilities for children in Anin, Białołęka, Chotomów, Międzylesie, Płudy, Sejny, Vilnius and others. Getter's convent was located at the entrance to the Warsaw Ghetto

The Warsaw Ghetto (german: Warschauer Ghetto, officially , "Jewish Residential District in Warsaw"; pl, getto warszawskie) was the largest of the Nazi ghettos during World War II and the Holocaust. It was established in November 1940 by the G ...

. When the Nazis commenced the clearing of the Ghetto in 1941, Getter took in many orphans and dispersed them among Family of Mary homes. As the Nazis began sending orphans to the gas chambers, Getter issued fake baptismal certificates, providing the children with false identities. The sisters lived in daily fear of the Germans. Michael Phayer credits Getter and the Family of Mary with rescuing more than 750 Jews.

Historians have shown that in numerous villages, Jewish families survived the Holocaust by living under assumed identities as Christians with full knowledge of the local inhabitants who did not betray their identities. This has been confirmed in the settlements of Bielsko (Upper Silesia), in Dziurków near Radom, in near Częstochowa, in Korzeniówka near Grójec

Grójec is a town in Poland, located in the Masovian Voivodeship, about south of Warsaw. It is the capital of the urban-rural administrative district Grójec and Grójec County. It has 16,674 inhabitants (2017). Grójec surroundings are consid ...

, in Łaskarzew, Garwolin County, Sobolew, and Garwolin County, Wilga triangle, and in several villages near Łowicz

Łowicz is a town in central Poland with 27,896 inhabitants (2020). It is situated in the Łódź Voivodeship (since 1999); previously, it was in Skierniewice Voivodeship (1975–1998). Together with a nearby station of Bednary, Łowicz is a ma ...

.

Some officials in the senior Polish priesthood maintained the same theological attitude of hostility toward the Jews which was known from before the invasion of Poland. After the war ended, some convents were unwilling to return Jewish children to postwar institutions that asked for them, and at times refused to disclose the adoptive parents' identities, forcing government agencies and courts to intervene. ''See also:''

Jews and the Polish government

Lack of international effort to aid Jews resulted in political uproar on the part of the Polish government in exile residing in Great Britain. The government often publicly expressed outrage at German mass murders of Jews. In 1942, the Directorate of Civil Resistance, part of the Polish Underground State, issued the following declaration based on reports by the Polish underground: The Polish government was the first to inform the Allies of World War II, Western Allies about the Holocaust, although early reports were often met with disbelief, even by Jewish leaders themselves, and then, for much longer, by Western powers.Witold Pilecki

Witold Pilecki (13 May 190125 May 1948; ; codenames ''Roman Jezierski, Tomasz Serafiński, Druh, Witold'') was a Polish World War II cavalry officer, intelligence agent, and resistance leader.

As a youth, Pilecki joined Polish underground s ...

was a member of the Polish Armia Krajowa (AK) resistance, and the only person who volunteered to be imprisoned in Auschwitz. As an agent of the underground intelligence, he began sending numerous reports about the camp and genocide to the Polish resistance movement in World War II, Polish resistance headquarters in Warsaw through the resistance network he organized in Auschwitz. In March 1941, Witold's Report, Pilecki's reports were being forwarded via the Polish resistance to the British government in London, but the British government refused AK reports on atrocities as being gross exaggerations and propaganda of the Polish government.

Similarly, in 1942, Jan Karski

Jan Karski (24 June 1914 – 13 July 2000) was a Polish soldier, resistance-fighter, and diplomat during World War II. He is known for having acted as a courier in 1940–1943 to the Polish government-in-exile and to Poland's Western Allies ab ...

, who had been serving as a courier between the Polish underground and the Polish government in exile, was smuggled into the Warsaw Ghetto

The Warsaw Ghetto (german: Warschauer Ghetto, officially , "Jewish Residential District in Warsaw"; pl, getto warszawskie) was the largest of the Nazi ghettos during World War II and the Holocaust. It was established in November 1940 by the G ...

and reported to the Polish, British and American governments on the terrible situation of the Jews in Poland, in particular the destruction of the Ghetto. He met with Polish politicians in exile, including the prime minister, as well as members of political parties such as the Polish Socialist Party, National Party (Poland), National Party, Labour Faction (1937), Labor Party, People's Party (Poland), People's Party, General Jewish Labour Bund in Poland, Jewish Bund and Poalei Zion. He also spoke to Anthony Eden, the British foreign secretary, and included a detailed statement on what he had seen in Warsaw and Bełżec.

In 1943 in London, Karski met the well-known journalist Arthur Koestler. He then traveled to the United States and reported to U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt. In July 1943, Jan Karski again personally reported to Roosevelt about the plight of Polish Jews, but the president "interrupted and asked the Polish emissary about the situation of... horses" in Poland. He also met with many other government and civic leaders in the United States, including Felix Frankfurter, Cordell Hull, William J. Donovan, and Stephen Samuel Wise, Stephen Wise. Karski also presented his report to the news media, bishops of various denominations (including Cardinal Samuel Stritch), members of the Hollywood (film industry), Hollywood film industry, and artists, but without success. Many of those he spoke to did not believe him and again supposed that his testimony was much exaggerated or was propaganda from the Polish government in exile.

The supreme political body of the underground government within Poland was the Delegatura Rządu Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej na Kraj, Delegatura. There were no Jewish representatives in it. Delegatura financed and sponsored ''

The supreme political body of the underground government within Poland was the Delegatura Rządu Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej na Kraj, Delegatura. There were no Jewish representatives in it. Delegatura financed and sponsored ''Żegota

Żegota (, full codename: the "Konrad Żegota Committee"Yad Vashem Shoa Resource CenterZegota/ref>) was the Polish Council to Aid Jews with the Government Delegation for Poland ( pl, Rada Pomocy Żydom przy Delegaturze Rządu RP na Kraj), an un ...

'', the organization for help to the Polish Jews – run jointly by Jews and non-Jews. Since 1942 Żegota was granted by Government Delegation for Poland, Delegatura nearly 29 million zlotys (over $5 million; or, 13.56 times as much, in today's funds) for the relief payments to thousands of extended Jewish families in Poland. The government-in-exile also provided special assistance including funds, arms and other supplies to Jewish resistance during the Holocaust, Jewish resistance organizations (like ŻOB and ŻZW), particularly from 1942 onwards. The interim government transmitted messages to the West from the Jewish underground, and gave support to their requests for retaliation on German targets if the atrocities are not stopped – a request that was dismissed by the Allied governments. The Polish government also tried, without much success, to increase the chances of Polish refugees finding a safe haven in neutral countries and to prevent deportations of escaping Jews back to Nazi-occupied Poland.

Polish Delegate of the Government in Exile residing in Hungary, diplomat Henryk Sławik known as the Polish Raoul Wallenberg, Wallenberg,Grzegorz Łubczyk, ''Trybuna'' 120 (3717), 24 May 2002. helped rescue over 30,000 refugees including 5,000 Polish Jews in Budapest, by giving them false Polish passports as Christians. He founded an orphanage for Jewish children officially named ''School for Children of Polish Officers'' in Vác. ''Archiwum działalności Prezydenta RP w latach 1997–2005.'' BIP.Maria Zawadzka"Righteous Among the Nations: Henryk Sławik and József Antall."

''Museum of the History of Polish Jews.'' Warsaw, 7 October 2010. ''See also:'

"The Sławik family" (ibidem).

Accessed 3 September 2011. With two members on the National Council, Polish Jews were sufficiently represented in the government in exile. Also, in 1943 a Jewish affairs section of the Underground State was set up by the

Government Delegation for Poland

The Government Delegation for Poland ( pl, Delegatura Rządu Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej na Kraj) was an agency of the Polish Government in Exile during World War II. It was the highest authority of the Polish Secret State in occupied Poland and was ...

; it was headed by Witold Bieńkowski and Władysław Bartoszewski

Władysław Bartoszewski (; 19 February 1922 – 24 April 2015) was a Polish politician, social activist, journalist, writer and historian. A former Auschwitz concentration camp prisoner, he was a World War II resistance fighter as part of th ...

. Its purpose was to organize efforts concerning the Polish Jewish population, to coordinate with ''Zegota'', and to prepare documentation about the fate of the Jews for the government in London. Regrettably, the great number of Polish Jews had been killed already even before the Government-in-exile fully realized the totality of the Final Solution. According to David Engel and Dariusz Stola, the government-in-exile concerned itself with the fate of Polish people in general, the re-recreation of the independent Polish state, and with establishing itself as an equal partner amongst the Allied forces. On top of its relative weakness, the government in exile was subject to the scrutiny of the West, in particular, American and British Jews reluctant to criticize their own governments for inaction in regard to saving their fellow Jews.

The Polish government and its underground representatives at home issued declarations that people acting against the Jews (blackmailers and others) would be punished by death. General Władysław Sikorski, the Prime Minister and Commander-in-Chief of the Polish Armed Forces, signed a decree calling upon the Polish population to extend aid to the persecuted Jews; including the following stern warning.