Religious antisemitism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Religious antisemitism is aversion to or discrimination against Jews as a whole, based on religious doctrines of

"Life of Constantine (Book III)"

337 CE. Retrieved March 12, 2006.

"In Poland, new 'Passion' plays on old hatreds"

''

Blood libels are false accusations that Jews use human blood in religious

Blood libels are false accusations that Jews use human blood in religious

German for "Jews' sow", ''

German for "Jews' sow", '' On many occasions, Jews were subjected to

On many occasions, Jews were subjected to

by Richard Gottheil, Meyer Kayserling, ''

PEW Global Attitudes Report

statistics on how the world views different religious groups

George Gruen attributes the increased animosity towards Jews in the Arab world to several factors, including the breakdown of the

"The Other Refugees: Jews of the Arab World"

''The Jerusalem Letter'', Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, June 1, 1988.

The Catholic Church and Antisemitism Poland, 1933-1939

* *

Anti-Semitism or anti-Judaism?

The Spanish Inquisition - Presentation with images and videos

{{DEFAULTSORT:Religious Antisemitism Christianity and antisemitism Islam and antisemitism

supersession

Supersessionism, also called replacement theology or fulfillment theology, is a Christian theology which asserts that the New Covenant through Jesus Christ has superseded or replaced the Mosaic covenant exclusive to the Jews. Supersessionist theo ...

that expect or demand the disappearance of Judaism

Judaism ( he, ''Yahăḏūṯ'') is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in th ...

and the conversion of Jews, and which figure their political enemies in Jewish terms. This often has led to false claims against Judaism and religious antisemitic canards

Antisemitic tropes, canards, or myths are " sensational reports, misrepresentations, or fabrications" that are defamatory towards Judaism as a religion or defamatory towards Jews as an ethnic or religious group. Since the Middle Ages, such rep ...

. It is sometimes called theological antisemitism.

Some scholars have argued that modern antisemitism is primarily based on nonreligious factors, John Higham being emblematic of this school of thought. However, this interpretation has been challenged. In 1966 Charles Glock and Rodney Stark

Rodney William Stark (July 8, 1934 — July 21, 2022) was an American sociologist of religion who was a longtime professor of sociology and of comparative religion at the University of Washington. At the time of his death he was the Distinguished ...

first published public option polling data showing that most Americans based their stereotypes of Jews

Stereotypes of Jews are generalized representations of Jews, often caricatured and of a prejudiced and antisemitic nature.

Common objects, phrases and traditions which are used to emphasize or ridicule Jewishness include bagels, the complaining ...

on religion. Further opinion polling since in America and Europe has supported this conclusion.

Origins

Father Edward Flannery, in his ''The Anguish of the Jew: Twenty-Three Centuries of Antisemitism'', traces the first clear examples of specific anti-Jewish sentiment back toAlexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

in the third century BCE. Flannery writes that it was the Jews' refusal to accept Greek religious and social standards that marked them out. Hecataetus of Abdera, a Greek historian of the early third century BCE, wrote that Moses "in remembrance of the exile of his people, instituted for them a misanthropic and inhospitable way of life." Manetho

Manetho (; grc-koi, Μανέθων ''Manéthōn'', ''gen''.: Μανέθωνος) is believed to have been an Egyptian priest from Sebennytos ( cop, Ϫⲉⲙⲛⲟⲩϯ, translit=Čemnouti) who lived in the Ptolemaic Kingdom in the early third ...

, an Egyptian historian, wrote that the Jews were expelled Egyptian lepers

Leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease (HD), is a long-term infection by the bacteria ''Mycobacterium leprae'' or ''Mycobacterium lepromatosis''. Infection can lead to damage of the nerves, respiratory tract, skin, and eyes. This nerve dama ...

who had been taught by Moses

Moses hbo, מֹשֶׁה, Mōše; also known as Moshe or Moshe Rabbeinu ( Mishnaic Hebrew: מֹשֶׁה רַבֵּינוּ, ); syr, ܡܘܫܐ, Mūše; ar, موسى, Mūsā; grc, Mωϋσῆς, Mōÿsēs () is considered the most important pr ...

"not to adore the gods". The same themes appeared in the works of Chaeremon

Chaeremon (; grc-gre, Χαιρήμων, ''gen.:'' Χαιρήμονος) was an Athenian dramatist of the first half of the fourth century BCE. He was generally considered a tragic poet like Choerilus. Aristotle said his works were intended for ...

, Lysimachus

Lysimachus (; Greek: Λυσίμαχος, ''Lysimachos''; c. 360 BC – 281 BC) was a Thessalian officer and successor of Alexander the Great, who in 306 BC, became King of Thrace, Asia Minor and Macedon.

Early life and career

Lysimachus wa ...

, Poseidonius, Apollonius Molon Apollonius Molon or Molo of Rhodes (or simply Molon; grc, Ἀπολλώνιος ὁ Μόλων), was a Greek rhetorician. He was a native of Alabanda, a pupil of Menecles, and settled at Rhodes, where he opened a school of rhetoric. Prior to tha ...

, and in Apion

Apion Pleistoneices ( el, Ἀπίων Πλειστονίκου ''Apíōn Pleistoníkēs''; 30–20 BC – c. AD 45–48), also called Apion Mochthos, was a Hellenized Egyptian grammarian, sophist, and commentator on Homer. He was born at the Siw ...

and Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his two major works—the ...

. Agatharchides of Cnidus wrote about the "ridiculous practices" of the Jews and of the "absurdity of their Law", and how Ptolemy Lagus

Ptolemy I Soter (; gr, Πτολεμαῖος Σωτήρ, ''Ptolemaîos Sōtḗr'' "Ptolemy the Savior"; c. 367 BC – January 282 BC) was a Macedonian Greek general, historian and companion of Alexander the Great from the Kingdom of Macedo ...

was able to invade Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

in 320 BCE because its inhabitants were observing the Sabbath

In Abrahamic religions, the Sabbath () or Shabbat (from Hebrew ) is a day set aside for rest and worship. According to the Book of Exodus, the Sabbath is a day of rest on the seventh day, commanded by God to be kept as a holy day of rest, as ...

.Flannery, Edward H. ''The Anguish of the Jews: Twenty-Three Centuries of Antisemitism''. Paulist Press, first published in 1985; this edition 2004, pp. 11-12. David Nirenberg

David Nirenberg is a medievalist and intellectual historian. He is the Director and Leon Levy Professor at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, NJ. He previously taught at the University of Chicago, where he was Dean of the Divinity Sc ...

also charts this history in '' Antijudaism: The Western Tradition''.

Christian antisemitism

Christian religious antisemitism is often expressed as anti-Judaism (i.e., it is argued that the antipathy is to the practices ofJudaism

Judaism ( he, ''Yahăḏūṯ'') is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in th ...

). As such, it is argued, antisemitism would cease if Jews stopped practicing or changed their public faith, especially by conversion

Conversion or convert may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* "Conversion" (''Doctor Who'' audio), an episode of the audio drama ''Cyberman''

* "Conversion" (''Stargate Atlantis''), an episode of the television series

* "The Conversion" ...

to Christianity, the official or right religion. However, there have been times when converts were also discriminated against, as in the case of liturgical exclusion of Jewish converts in the case of Christianized ''Marranos

Marranos were Spanish and Portuguese Jews living in the Iberian Peninsula who converted or were forced to convert to Christianity during the Middle Ages, but continued to practice Judaism in secrecy.

The term specifically refers to the cha ...

'' or Iberian Jews in the late 15th century and 16th century accused of secretly practising Judaism or Jewish customs.

New Testament and antisemitism

Frederick Schweitzer and Marvin Perry write that the authors of the gospel accounts sought to place responsibility for theCrucifixion of Jesus

The crucifixion and death of Jesus occurred in 1st-century Judea, most likely in AD 30 or AD 33. It is described in the four canonical gospels, referred to in the New Testament epistles, attested to by other ancient sources, and consider ...

and his death on Jews, rather than the Roman emperor or Pontius Pilate

Pontius Pilate (; grc-gre, Πόντιος Πιλᾶτος, ) was the fifth governor of the Roman province of Judaea, serving under Emperor Tiberius from 26/27 to 36/37 AD. He is best known for being the official who presided over the trial of ...

. As a result, Christians for centuries viewed Jews as "the Christ Killers".Perry & Schweitzer (2002), p. 18. The destruction of the Second Temple

The Second Temple (, , ), later known as Herod's Temple, was the reconstructed Temple in Jerusalem between and 70 CE. It replaced Solomon's Temple, which had been built at the same location in the United Kingdom of Israel before being inherited ...

was seen as judgment from God to the Jews for that death, and Jews were seen as "a people condemned forever to suffer exile and degradation". According to historian Edward H. Flannery

Edward H. Flannery (August 20, 1912 – October 19, 1998) was an American priest in the Roman Catholic Diocese of Providence, and the author of ''The Anguish of the Jews: Twenty-Three Centuries of Antisemitism'', first published in 1965.

Fr. ...

, the Gospel of John

The Gospel of John ( grc, Εὐαγγέλιον κατὰ Ἰωάννην, translit=Euangélion katà Iōánnēn) is the fourth of the four canonical gospels. It contains a highly schematic account of the ministry of Jesus, with seven "sig ...

in particular contains many verses that refer to Jews in a pejorative manner.

In , Paul

Paul may refer to:

*Paul (given name), a given name (includes a list of people with that name)

* Paul (surname), a list of people

People

Christianity

*Paul the Apostle (AD c.5–c.64/65), also known as Saul of Tarsus or Saint Paul, early Chri ...

states that the Churches in Judea had been persecuted by the Jews who killed Jesus and that such people displease God, oppose all men, and had prevented Paul from speaking to the gentile nations concerning the New Testament message. Described by Hyam Maccoby

Hyam Maccoby ( he, חיים מכובי, 1924–2004) was a Jewish-British scholar and dramatist specialising in the study of the Jewish and Christian religious traditions. He was known for his theories of the historical Jesus and the origins of C ...

as "the most explicit outburst against Jews in Paul's Epistles",Hyam Maccoby

Hyam Maccoby ( he, חיים מכובי, 1924–2004) was a Jewish-British scholar and dramatist specialising in the study of the Jewish and Christian religious traditions. He was known for his theories of the historical Jesus and the origins of C ...

, ''The Mythmaker: Paul and the Invention of Christianity'', Harper & Row

Harper is an American publishing house, the flagship imprint of global publisher HarperCollins based in New York City.

History

J. & J. Harper (1817–1833)

James Harper and his brother John, printers by training, started their book publishin ...

, 1986, , p. 203. these verses have repeatedly been employed for antisemitic purposes. Maccoby views it as one of Paul's innovations responsible for creating Christian antisemitism, though he notes that some have argued these particular verses are later interpolations not written by Paul. Craig Blomberg argues that viewing them as antisemitic is a mistake, but "understandable in light of aul'sharsh words". In his view, Paul is not condemning all Jews forever, but merely those he believed had specifically persecuted the prophets, Jesus, or the 1st-century church. Blomberg sees Paul's words here as no different in kind than the harsh words the prophets of the Old Testament have for the Jews.

The Codex Sinaiticus

The Codex Sinaiticus ( Shelfmark: London, British Library, Add MS 43725), designated by siglum [Aleph] or 01 (in the Gregory-Aland numbering of New Testament manuscripts), δ 2 (in the von Soden numbering of New Testament manuscript ...

contains two extra books in the New Testament—the Shepherd of Hermas

A shepherd or sheepherder is a person who tends, herds, feeds, or guards flocks of sheep. ''Shepherd'' derives from Old English ''sceaphierde (''sceap'' 'sheep' + ''hierde'' 'herder'). ''Shepherding is one of the world's oldest occupations, i ...

and the Epistle of Barnabas

The ''Epistle of Barnabas'' ( el, Βαρνάβα Ἐπιστολή) is a Greek epistle written between AD 70 and 132. The complete text is preserved in the 4th-century ''Codex Sinaiticus'', where it appears immediately after the New Testament ...

. The latter emphasizes the claim that it was the Jews, not the Romans, who killed Jesus, and is full of antisemitism. The Epistle of Barnabas was not accepted as part of the canon; Professor Bart Ehrman

Bart Denton Ehrman (born 1955) is an American New Testament scholar focusing on textual criticism of the New Testament, the historical Jesus, and the origins and development of early Christianity. He has written and edited 30 books, includin ...

has stated "the suffering of Jews in the subsequent centuries would, if possible, have been even worse had the Epistle of Barnabas remained".

Early Christianity

A number of early and influential Church works—such as the dialogues ofJustin Martyr

Justin Martyr ( el, Ἰουστῖνος ὁ μάρτυς, Ioustinos ho martys; c. AD 100 – c. AD 165), also known as Justin the Philosopher, was an early Christian apologist and philosopher.

Most of his works are lost, but two apologies and ...

, the homilies of John Chrysostom

John Chrysostom (; gr, Ἰωάννης ὁ Χρυσόστομος; 14 September 407) was an important Early Church Father who served as archbishop of Constantinople. He is known for his preaching and public speaking, his denunciation of ...

, and the testimonies of church father Cyprian

Cyprian (; la, Thaschus Caecilius Cyprianus; 210 – 14 September 258 AD''The Liturgy of the Hours according to the Roman Rite: Vol. IV.'' New York: Catholic Book Publishing Company, 1975. p. 1406.) was a bishop of Carthage and an early Christ ...

—are strongly anti-Jewish.

During a discussion on the celebration of Easter

Easter,Traditional names for the feast in English are "Easter Day", as in the '' Book of Common Prayer''; "Easter Sunday", used by James Ussher''The Whole Works of the Most Rev. James Ussher, Volume 4'') and Samuel Pepys''The Diary of Samue ...

during the First Council of Nicaea

The First Council of Nicaea (; grc, Νίκαια ) was a council of Christian bishops convened in the Bithynian city of Nicaea (now İznik, Turkey) by the Roman Emperor Constantine I in AD 325.

This ecumenical council was the first effort ...

in 325 CE, Roman emperor Constantine said,Eusebius

Eusebius of Caesarea (; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος ; 260/265 – 30 May 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilus (from the grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος τοῦ Παμφίλου), was a Greek historian of Christianity, exegete, and Chris ...

"Life of Constantine (Book III)"

337 CE. Retrieved March 12, 2006.

... it appeared an unworthy thing that in the celebration of this most holy feast we should follow the practice of the Jews, who have impiously defiled their hands with enormous sin, and are, therefore, deservedly afflicted with blindness of soul. ... Let us then have nothing in common with the detestable Jewish crowd; for we have received from our Saviour a different way.Prejudice against Jews in the

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

was formalized in 438, when the ''Code of Theodosius II

Theodosius II ( grc-gre, Θεοδόσιος, Theodosios; 10 April 401 – 28 July 450) was Roman emperor for most of his life, proclaimed ''augustus'' as an infant in 402 and ruling as the eastern Empire's sole emperor after the death of his ...

'' established Christianity as the only legal religion in the Roman Empire. The Justinian Code

The ''Corpus Juris'' (or ''Iuris'') ''Civilis'' ("Body of Civil Law") is the modern name for a collection of fundamental works in jurisprudence, issued from 529 to 534 by order of Justinian I, Byzantine Emperor. It is also sometimes referred ...

a century later stripped Jews of many of their rights, and Church councils throughout the 6th and 7th century, including the Council of Orleans, further enforced anti-Jewish provisions. These restrictions began as early as 305, when, in Elvira (now Granada

Granada (,, DIN: ; grc, Ἐλιβύργη, Elibýrgē; la, Illiberis or . ) is the capital city of the province of Granada, in the autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada mountains, at the c ...

), a Spanish town in Andalucia

Andalusia (, ; es, Andalucía ) is the southernmost autonomous community in Peninsular Spain. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomous community in the country. It is officially recognised as a "historical nationality". The ...

, the first known laws of any church council against Jews appeared. Christian women were forbidden to marry Jews unless the Jew first converted to Catholicism. Jews were forbidden to extend hospitality to Catholics. Jews could not keep Catholic Christian concubine

Concubinage is an interpersonal and sexual relationship between a man and a woman in which the couple does not want, or cannot enter into a full marriage. Concubinage and marriage are often regarded as similar but mutually exclusive.

Concubi ...

s and were forbidden to bless the fields of Catholics. In 589, in Catholic Iberia

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese language, Aragonese and Occitan language, Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a pe ...

, the Third Council of Toledo

The Third Council of Toledo (589) marks the entry of Visigothic Spain into the Catholic Church, and is known for codifying the filioque clause into Western Christianity."Filioque." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. ...

ordered that children born of marriage between Jews and Catholic be baptized by force. By the Twelfth Council of Toledo (681) a policy of forced conversion of all Jews was initiated (Liber Judicum, II.2 as given in Roth).Roth, A. M. Roth, and Roth, Norman. ''Jews, Visigoths and Muslims in Medieval Spain'', Brill Academic, 1994. Thousands fled, and thousands of others converted to Roman Catholicism.

Accusations of deicide

Although never a part ofChristian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι� ...

dogma

Dogma is a belief or set of beliefs that is accepted by the members of a group without being questioned or doubted. It may be in the form of an official system of principles or doctrines of a religion, such as Roman Catholicism, Judaism, Islam ...

, many Christians, including members of the clergy

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

, held the Jewish people under an antisemitic canard

Antisemitic tropes, canards, or myths are " sensational reports, misrepresentations, or fabrications" that are defamatory towards Judaism as a religion or defamatory towards Jews as an ethnic or religious group. Since the Middle Ages, such repo ...

to be collectively responsible for deicide, the killing of Jesus, who they believed was the son of God. According to this interpretation, the Jews present at Jesus' death as well as the Jewish people collectively and for all time had committed the sin of deicide, or God-killing. The accusation has been the most powerful warrant for antisemitism by Christians.

Passion plays are dramatic stagings representing the trial and death of Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label= Hebrew/ Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and relig ...

and they have historically been used in remembrance of Jesus' death during Lent

Lent ( la, Quadragesima, 'Fortieth') is a solemn religious moveable feast#Lent, observance in the liturgical calendar commemorating the 40 days Jesus spent fasting in the desert and enduring Temptation of Jesus, temptation by Satan, according ...

. These plays historically blamed the Jews for the death of Jesus in a polemic

Polemic () is contentious rhetoric intended to support a specific position by forthright claims and to undermine the opposing position. The practice of such argumentation is called ''polemics'', which are seen in arguments on controversial topic ...

al fashion, depicting a crowd of Jewish people condemning Jesus to death by crucifixion

Crucifixion is a method of capital punishment in which the victim is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross or beam and left to hang until eventual death from exhaustion and asphyxiation. It was used as a punishment by the Persians, Carthagi ...

and a Jewish leader assuming eternal collective guilt

Collective responsibility, also known as collective guilt, refers to responsibilities of organizations, groups and societies. Collective responsibility in the form of collective punishment is often used as a disciplinary measure in closed insti ...

for the crowd for the murder of Jesus, which, ''The Boston Globe

''The Boston Globe'' is an American daily newspaper founded and based in Boston, Massachusetts. The newspaper has won a total of 27 Pulitzer Prizes, and has a total circulation of close to 300,000 print and digital subscribers. ''The Boston Glob ...

'' explains, "for centuries prompted vicious attacks—or pogrom

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russian ...

s—on Europe's Jewish communities".Sennott, Charles "In Poland, new 'Passion' plays on old hatreds"

''

The Boston Globe

''The Boston Globe'' is an American daily newspaper founded and based in Boston, Massachusetts. The newspaper has won a total of 27 Pulitzer Prizes, and has a total circulation of close to 300,000 print and digital subscribers. ''The Boston Glob ...

'', April 10, 2004.

Blood libel

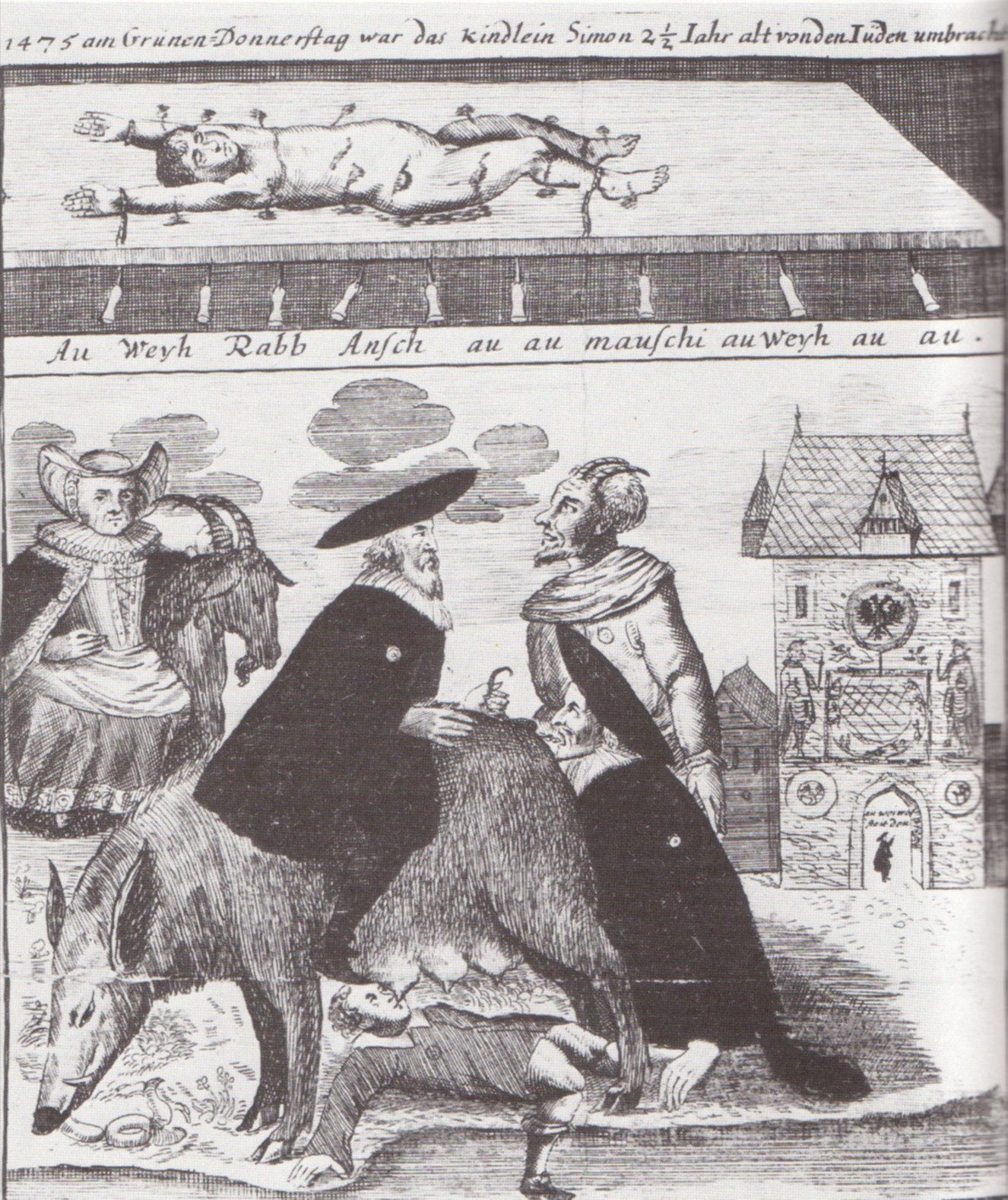

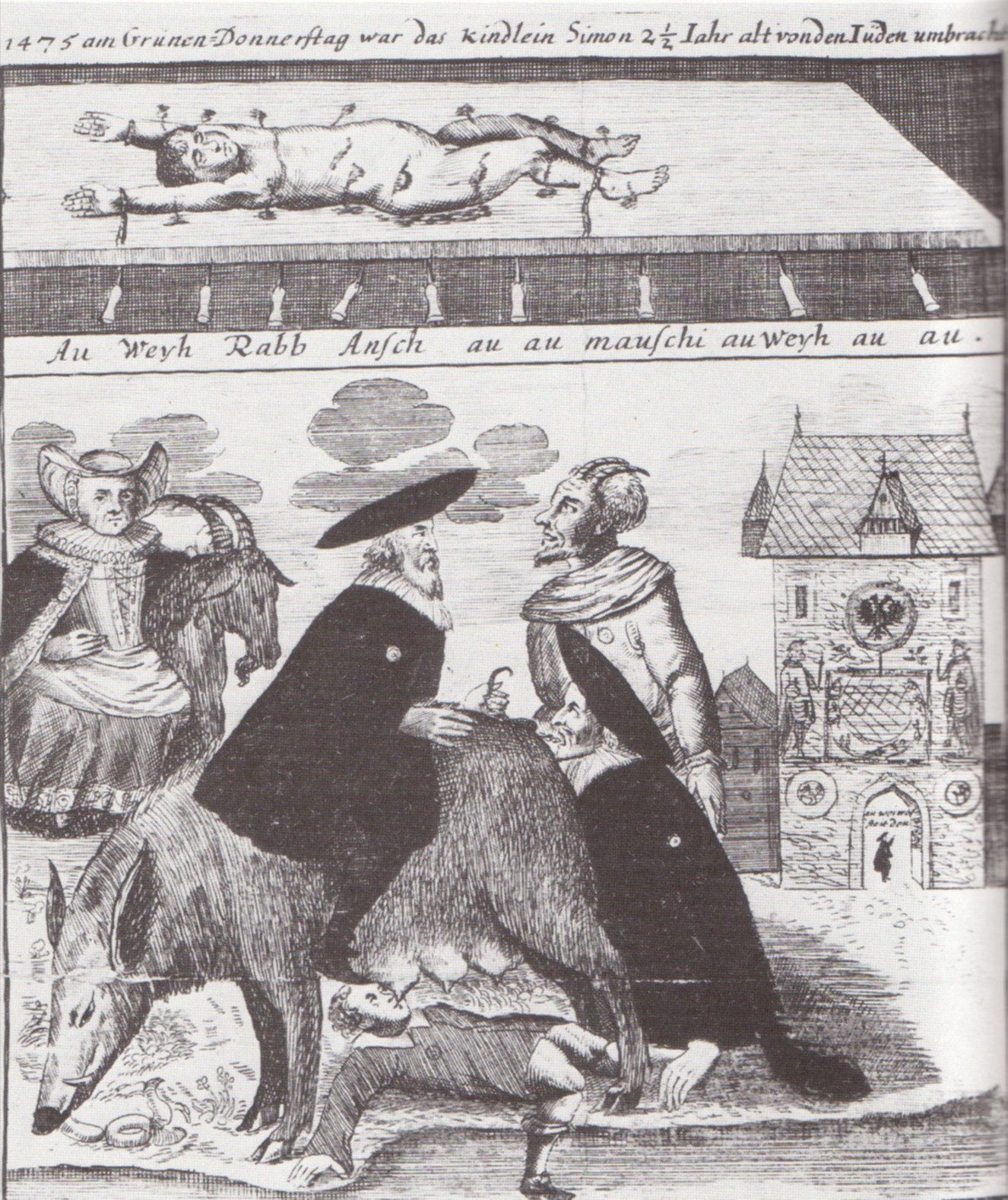

Blood libels are false accusations that Jews use human blood in religious

Blood libels are false accusations that Jews use human blood in religious rituals

A ritual is a sequence of activities involving gestures, words, actions, or objects, performed according to a set sequence. Rituals may be prescribed by the traditions of a community, including a religious community. Rituals are characterized, b ...

. Historically these are accusations that the blood of Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι� ...

children is especially coveted. In many cases, blood libels served as the basis for a blood libel cult

In modern English, ''cult'' is usually a pejorative term for a social group that is defined by its unusual religious, spiritual, or philosophical beliefs and rituals, or its common interest in a particular personality, object, or goal. Thi ...

, in which the alleged victim of human sacrifice was elevated to the status of a martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an externa ...

and, in some cases, canonized

Canonization is the declaration of a deceased person as an officially recognized saint, specifically, the official act of a Christian communion declaring a person worthy of public veneration and entering their name in the canon catalogue of s ...

.

Although the first known instance of a blood libel is found in the writings of Apion

Apion Pleistoneices ( el, Ἀπίων Πλειστονίκου ''Apíōn Pleistoníkēs''; 30–20 BC – c. AD 45–48), also called Apion Mochthos, was a Hellenized Egyptian grammarian, sophist, and commentator on Homer. He was born at the Siw ...

, who claimed that the Jews sacrificed Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

victims in the Temple, no further incidents are recorded until the 12th century, when blood libels began to proliferate. These libels have persisted from then through the 21st century.

In the modern era, the blood libel continues to be a major aspect of antisemitism. It has extended its reach to accuse Jews of many different forms of harm that can be carried out against other people.

Medieval and Renaissance Europe

Antisemitism was widespread in Europe during theMiddle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

. In those times, a main cause of prejudice against Jews in Europe was the religious one. Although not part of Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

dogma

Dogma is a belief or set of beliefs that is accepted by the members of a group without being questioned or doubted. It may be in the form of an official system of principles or doctrines of a religion, such as Roman Catholicism, Judaism, Islam ...

, many Christians, including members of the clergy

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

, held the Jewish people collectively responsible for the death of Jesus, a practice originated by Melito of Sardis

Melito of Sardis ( el, Μελίτων Σάρδεων ''Melítōn Sárdeōn''; died ) was the bishop of Sardis near Smyrna in western Anatolia, and a great authority in early Christianity. Melito held a foremost place in terms of bishops in Asia ...

.

Among socio-economic factors were restrictions by the authorities. Local rulers and church officials closed the doors for many professions to the Jews, pushing them into occupations considered socially inferior such as accounting, rent-collecting and moneylending

In finance, a loan is the lending of money by one or more individuals, organizations, or other entities to other individuals, organizations, etc. The recipient (i.e., the borrower) incurs a debt and is usually liable to pay interest on that de ...

, which was tolerated then as a " necessary evil".Paley, Susan and Koesters, Adrian Gibbons, eds. . Retrieved March 12, 2006. During the Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

, Jews were accused as being the cause, and were often killed.See Stéphane Barry and Norbert Gualde, ''La plus grande épidémie de l'histoire'' ("The greatest epidemics in history"), in ''L'Histoire

''L'Histoire'' is a monthly mainstream French magazine dedicated to historical studies, recognized by peers as the most important historical popular magazine (as opposed to specific university journals or less scientific popular historical magaz ...

'' magazine, n°310, June 2006, p.47 There were expulsions of Jews from England, France, Germany, Portugal and Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

during the Middle Ages as a result of antisemitism.

German for "Jews' sow", ''

German for "Jews' sow", ''Judensau

A ''Judensau'' (German for "Jews' sow") is a folk art image of Jews in obscene contact with a large sow (female pig), which in Judaism is an unclean animal, that appeared during the 13th century in Germany and some other European countries; i ...

'' was the derogatory and dehumanizing imagery of Jews that appeared around the 13th century. Its popularity lasted for over 600 years and was revived by the Nazis. The Jews, typically portrayed in obscene

An obscenity is any utterance or act that strongly offends the prevalent morality of the time. It is derived from the Latin ''obscēnus'', ''obscaenus'', "boding ill; disgusting; indecent", of uncertain etymology. Such loaded language can be us ...

contact with unclean animals

In some religions, an unclean animal is an animal whose consumption or handling is taboo. According to these religions, persons who handle such animals may need to ritually purify themselves to get rid of their uncleanliness.

Judaism

In Jud ...

such as pigs or owls or representing a devil

A devil is the personification of evil as it is conceived in various cultures and religious traditions. It is seen as the objectification of a hostile and destructive force. Jeffrey Burton Russell states that the different conceptions of ...

, appeared on cathedral

A cathedral is a church that contains the ''cathedra'' () of a bishop, thus serving as the central church of a diocese, conference, or episcopate. Churches with the function of "cathedral" are usually specific to those Christian denominations ...

or church

Church may refer to:

Religion

* Church (building), a building for Christian religious activities

* Church (congregation), a local congregation of a Christian denomination

* Church service, a formalized period of Christian communal worship

* Chri ...

ceilings, pillars, utensils, etchings, etc. Often, the images combined several antisemitic motifs and included derisive prose or poetry.

"Dozens of Judensaus... intersect with the portrayal of the Jew as a Christ killer. Various illustrations of the murder of Simon of Trent blended images of Judensau, the devil, the murder of little Simon himself, and theInCrucifixion Crucifixion is a method of capital punishment in which the victim is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross or beam and left to hang until eventual death from exhaustion and asphyxiation. It was used as a punishment by the Persians, Carthagi .... In the 17th-century engraving from Frankfurt... a well-dressed, very contemporary-looking Jew has mounted the sow backward and holds her tail, while a second Jew sucks at her milk and a third eats her feces. The horned devil, himself wearing aJewish badge Yellow badges (or yellow patches), also referred to as Jewish badges (german: Judenstern, lit=Jew's star), are badges that Jews were ordered to wear at various times during the Middle Ages by some caliphates, at various times during the Medieva ..., looks on and the butchered Simon, splayed as if on a cross, appears on a panel above."

Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

's ''Merchant of Venice

''The Merchant of Venice'' is a play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written between 1596 and 1598. A merchant in Venice named Antonio defaults on a large loan provided by a Jewish moneylender, Shylock.

Although classified as a ...

'', considered to be one of the greatest romantic comedies of all time, the villain Shylock

Shylock is a fictional character in William Shakespeare's play ''The Merchant of Venice'' (c. 1600). A Venetian Jewish moneylender, Shylock is the play's principal antagonist. His defeat and conversion to Christianity form the climax of the ...

was a Jewish moneylender. By the end of the play he is mocked on the streets after his daughter elopes with a Christian. Shylock, then, compulsorily converts to Christianity as a part of a deal gone wrong. This has raised profound implications regarding Shakespeare and antisemitism.

During the Middle Ages, the story of Jephonias, the Jew who tried to overturn Mary's funeral bier, changed from his converting to Christianity into his simply having his hands cut off by an angel.

On many occasions, Jews were subjected to

On many occasions, Jews were subjected to blood libels

Blood libel or ritual murder libel (also blood accusation) is an antisemitic canardTurvey, Brent E. ''Criminal Profiling: An Introduction to Behavioral Evidence Analysis'', Academic Press, 2008, p. 3. "Blood libel: An accusation of ritual mur ...

, false accusations of drinking the blood of Christian children in mockery of the Christian Eucharist

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was institu ...

.

Jews were subject to a wide range of legal restrictions throughout the Middle Ages, some of which lasted until the end of the 19th century. Jews were excluded from many trades, the occupations varying with place and time, and determined by the influence of various non-Jewish competing interests. Often Jews were barred from all occupations but money-lending and peddling, with even these at times forbidden.

19th century

Throughout the 19th century and into the 20th, theRoman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

still incorporated strong antisemitic elements, despite increasing attempts to separate anti-Judaism

Anti-Judaism is the "total or partial opposition to Judaism as a religion—and the total or partial opposition to Jews as adherents of it—by persons who accept a competing system of beliefs and practices and consider certain genuine Judai ...

, the opposition to the Jewish religion on religious grounds, and racial antisemitism

Racial antisemitism is prejudice against Jews based on a belief or assertion that Jews constitute a distinct race that has inherent traits or characteristics that appear in some way abhorrent or inherently inferior or otherwise different from ...

. Pope Pius VII

Pope Pius VII ( it, Pio VII; born Barnaba Niccolò Maria Luigi Chiaramonti; 14 August 1742 – 20 August 1823), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 14 March 1800 to his death in August 1823. Chiaramonti was also a m ...

(1800–1823) had the walls of the Jewish Ghetto

A ghetto, often called ''the'' ghetto, is a part of a city in which members of a minority group live, especially as a result of political, social, legal, environmental or economic pressure. Ghettos are often known for being more impoverished ...

in Rome rebuilt after the Jews were released by Napoleon, and Jews were restricted to the Ghetto through the end of the Papal States in 1870.

Additionally, official organizations such as the Jesuits

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders = ...

banned candidates "who are descended from the Jewish race unless it is clear that their father, grandfather, and great-grandfather have belonged to the Catholic Church" until 1946. Brown University historian David Kertzer

David Israel Kertzer (born February 20, 1948) is an American anthropologist, historian, and academic, specializing in the political, demographic, and religious history of Italy. He is the Paul Dupee, Jr. University Professor of Social Science, P ...

, working from the Vatican archive, has further argued in his book '' The Popes Against the Jews'' that in the 19th century and early 20th century the Church adhered to a distinction between "good antisemitism" and "bad antisemitism".

The "bad" kind promoted hatred of Jews because of their descent. This was considered un-Christian because the Christian message was intended for all of humanity regardless of ethnicity; anyone could become a Christian. The "good" kind criticized alleged Jewish conspiracies to control newspapers, banks, and other institutions, to care only about accumulation of wealth, etc. Many Catholic bishops wrote articles criticizing Jews on such grounds, and, when accused of promoting hatred of Jews, would remind people that they condemned the "bad" kind of antisemitism. Kertzer's work is not, therefore, without critics; scholar of Jewish-Christian relations Rabbi David G. Dalin

David G. Dalin (born 28 June 1949) is an American rabbi and historian, and the author, co-author, or editor of twelve books on American Jewish history and politics, and Jewish-Christian relations.

Career

Dalin received a B.A. from the University ...

, for example, criticized Kertzer in the ''Weekly Standard

''The Weekly Standard'' was an American neoconservative political magazine of news, analysis and commentary, published 48 times per year. Originally edited by founders Bill Kristol and Fred Barnes, the ''Standard'' had been described as a "red ...

'' for using evidence selectively.

The Holocaust

The Nazis usedMartin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

's book, ''On the Jews and Their Lies

''On the Jews and Their Lies'' (german: Von den Jüden und iren Lügen; in modern spelling ) is a 65,000-word anti-Judaic and antisemitic treatise written in 1543 by the German Reformation leader Martin Luther (1483–1546).

Luther's attitude t ...

'' (1543), to claim a moral righteousness for their ideology. Luther even went so far as to advocate the murder of those Jews who refused to convert to Christianity, writing that "we are at fault in not slaying them"

Archbishop Robert Runcie

Robert Alexander Kennedy Runcie, Baron Runcie, (2 October 1921 – 11 July 2000) was an English Anglican bishop. He was the Archbishop of Canterbury from 1980 to 1991, having previously been Bishop of St Albans. He travelled the world widely ...

has asserted that: "Without centuries of Christian antisemitism, Hitler's passionate hatred would never have been so fervently echoed...because for centuries Christians have held Jews collectively responsible for the death of Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label= Hebrew/ Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and relig ...

. On Good Friday Jews, have in times past, cowered behind locked doors with fear of a Christian mob seeking 'revenge' for deicide. Without the poisoning of Christian minds through the centuries, the Holocaust is unthinkable." The dissident Catholic priest Hans Küng

Hans Küng (; 19 March 1928 – 6 April 2021) was a Swiss Catholic priest, theologian, and author. From 1995 he was president of the Foundation for a Global Ethic (Stiftung Weltethos).

Küng was ordained a priest in 1954, joined the faculty o ...

has written in his book ''On Being a Christian'' that "Nazi anti-Judaism was the work of godless, anti-Christian criminals. But it would not have been possible without the almost two thousand years' pre-history of 'Christian' anti-Judaism..."

The document Dabru Emet was issued by many American Jewish scholars in 2000 as a statement about Jewish-Christian relations. This document states,Nazism was not a Christian phenomenon. Without the long history of Christian anti-Judaism and Christian violence against Jews, Nazi ideology could not have taken hold nor could it have been carried out. Too many Christians participated in, or were sympathetic to, Nazi atrocities against Jews. Other Christians did not protest sufficiently against these atrocities. But Nazism itself was not an inevitable outcome of Christianity.According to American

historian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human race; as well as the st ...

Lucy Dawidowicz, antisemitism has a long history within Christianity. The line of "antisemitic descent" from Luther, the author of ''On the Jews and Their Lies'', to Hitler is "easy to draw". In her '' The War Against the Jews, 1933-1945'', she contends that Luther and Hitler were obsessed by the "demonologized universe" inhabited by Jews. Dawidowicz writes that the similarities between Luther's anti-Jewish writings and modern antisemitism are no coincidence, because they derived from a common history of ''Judenhass'', which can be traced to Haman's advice to Ahasuerus

Ahasuerus ( ; , commonly ''Achashverosh'';; fa, اخشورش, Axšoreš; fa, label= New Persian, خشایار, Xašāyār; grc, Ξέρξης, Xérxēs. grc, label= Koine Greek, Ἀσουήρος, Asouḗros, in the Septuagint; la, Assue ...

. Although modern German antisemitism also has its roots in German nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

and the liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

revolution of 1848, Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι� ...

antisemitism she writes is a foundation that was laid by the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and "upon which Luther built". Dawidowicz' allegations and positions are criticized and not accepted by most historians however. For example, in ''Studying the Jew'' Alan Steinweis notes that, "Old-fashioned antisemitism, Hitler argued, was insufficient, and would lead only to pogroms, which contribute little to a permanent solution. This is why, Hitler maintained, it was important to promote 'an antisemitism of reason,' one that acknowledged the racial basis of Jewry." Interviews with Nazis by other historians show that the Nazis thought that their views were rooted in biology, not historical prejudices. For example, "S. became a missionary for this biomedical vision... As for anti-Semitic attitudes and actions, he insisted that 'the racial question... ndresentment of the Jewish race... had nothing to do with medieval anti-Semitism...' That is, it was all a matter of scientific biology and of community."

Post-Holocaust

TheSecond Vatican Council

The Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the , or , was the 21st ecumenical council of the Roman Catholic Church. The council met in St. Peter's Basilica in Rome for four periods (or sessions), each lasting between 8 and ...

, the ''Nostra aetate

(from Latin: "In our time") is the incipit of the Declaration on the Relation of the Church with Non-Christian Religions of the Second Vatican Council. Passed by a vote of 2,221 to 88 of the assembled bishops, this declaration was promulgated o ...

'' document, and the efforts of Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II ( la, Ioannes Paulus II; it, Giovanni Paolo II; pl, Jan Paweł II; born Karol Józef Wojtyła ; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 1978 until his ...

helped reconcile Jews and Catholicism in recent decades, however. According to Catholic Holocaust scholar Michael Phayer

Michael Phayer (born 1935) is an American historian and professor emeritus at Marquette University in Milwaukee and has written on 19th- and 20th-century European history and the Holocaust.

Phayer received his PhD from the University of Munich i ...

, the Church as a whole recognized its failings during the council, when it corrected the traditional beliefs of the Jews having committed deicide and affirmed that they remained God's chosen people.

In 1994, the Church Council of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America

The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA) is a mainline Protestant Lutheran church headquartered in Chicago, Illinois. The ELCA was officially formed on January 1, 1988, by the merging of three Lutheran church bodies. , it has approxim ...

, the largest Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched ...

denomination in the United States and a member of the Lutheran World Federation

The Lutheran World Federation (LWF; german: Lutherischer Weltbund) is a global communion of national and regional Lutheran denominations headquartered in the Ecumenical Centre in Geneva, Switzerland. The federation was founded in the Swedish ...

publicly rejected

''Rejected'' is an animated film directed by Don Hertzfeldt that was released in 2000. It was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film the following year at the 73rd Academy Awards, and received 27 awards from film festivals ...

Luther's antisemitic writings.

Islamic antisemitism

With the origin ofIslam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

in the 7th century AD and its rapid spread through the Arabian peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plat ...

and beyond, Jews (and many other peoples) became subject to the will of Muslim rulers. The quality of the rule varied considerably in different periods, as did the attitudes of the rulers, government officials, clergy and general population to various subject peoples from time to time, which was reflected in their treatment of these subjects.

Various definitions of antisemitism in the context of Islam are given. The extent of antisemitism among Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

s varies depending on the chosen definition:

*Scholars like Claude Cahen

Claude Cahen (26 February 1909 – 18 November 1991) was a 20th-century French Marxist orientalist and historian. He specialized in the studies of the Islamic Middle Ages, Muslim sources about the Crusades, and social history of the medieval Isla ...

and Shelomo Dov Goitein

Shelomo Dov Goitein (April 3, 1900 – February 6, 1985) was a German-Jewish ethnographer, historian and Arabist known for his research on Jewish life in the Islamic Middle Ages, and particularly on the Cairo Geniza.

Biography

Shelomo Dov (Frit ...

define it to be the animosity specifically applied to Jews only and do not include discriminations practiced against Non-Muslims in general.Shelomo Dov Goitein

Shelomo Dov Goitein (April 3, 1900 – February 6, 1985) was a German-Jewish ethnographer, historian and Arabist known for his research on Jewish life in the Islamic Middle Ages, and particularly on the Cairo Geniza.

Biography

Shelomo Dov (Frit ...

, A Mediterranean Society: An Abridgment in One Volume, p. 293"Dhimma" by Claude Cahen in Encyclopedia of Islam

The ''Encyclopaedia of Islam'' (''EI'') is an encyclopaedia of the academic discipline of Islamic studies published by Brill. It is considered to be the standard reference work in the field of Islamic studies. The first edition was published ...

The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion,''Antisemitism'' For these scholars, antisemitism in Medieval Islam has been local and sporadic rather than general and endemic helomo Dov Goitein not at all present laude Cahen

The ''lauda'' (Italian pl. ''laude'') or ''lauda spirituale'' was the most important form of vernacular sacred song in Italy in the late medieval music, medieval era and Renaissance music, Renaissance. ''Laude'' remained popular into the ninetee ...

or rarely present.

*According to Bernard Lewis

Bernard Lewis, (31 May 1916 – 19 May 2018) was a British American historian specialized in Oriental studies. He was also known as a public intellectual and political commentator. Lewis was the Cleveland E. Dodge Professor Emeritus of Near ...

, antisemitism is marked by two distinct features: Jews are judged according to a standard different from that applied to others, and they are accused of "cosmic evil". For Lewis, from the late 19th century, movements appear among Muslims of which for the first time one can legitimately use the technical term antisemitic. However, he describes demonizing beliefs, anti-Jewish discrimination and systematic humiliations, as an "inherent" part of the traditional Muslim world, even if violent persecutions were relatively rare.

Pre-modern times

According to Jane Gerber, "the Muslim is continually influenced by the theological threads of anti-Semitism embedded in the earliest chapters of Islamic history."Gerber (1986), p. 82 In the light of the Jewish defeat at the hands ofMuhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mon ...

, Muslims traditionally viewed Jews with contempt and as objects of ridicule. Jews were seen as hostile, cunning, and vindictive, but nevertheless weak and ineffectual. Cowardice was the quality most frequently attributed to Jews. Another stereotype associated with the Jews was their alleged propensity to trickery and deceit. While most anti-Jewish polemicists saw those qualities as inherently Jewish, Ibn Khaldun

Ibn Khaldun (; ar, أبو زيد عبد الرحمن بن محمد بن خلدون الحضرمي, ; 27 May 1332 – 17 March 1406, 732-808 AH) was an Arab

The Historical Muhammad', Irving M. Zeitlin, (Polity Press, 2007), p. 21; "It is, of ...

attributed them to the mistreatment of Jews at the hands of the dominant nations. For that reason, says Ibn Khaldun, Jews "are renowned, in every age and climate, for their wickedness and their slyness".

Muhammad's attitude towards Jews was basically neutral at the beginning. During his lifetime, Jews lived on the Arabian Peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plat ...

, especially in and around Medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the Holiest sites in Islam, second-holiest city in Islam, ...

. They refused to accept Muhammad's teachings. Eventually he fought them, defeated them, and most of them were killed. The traditional biographies of Muhammad describe the expulsion of the Banu Qaynuqa

The Banu Qaynuqa ( ar, بنو قينقاع; he, בני קינוקאע; also spelled Banu Kainuka, Banu Kaynuka, Banu Qainuqa, Banu Qaynuqa) was one of the three main Jewish tribes living in the 7th century of Medina, now in Saudi Arabia. The grea ...

in the post Badr Badr (Arabic: بدر) as a given name below is an Arabic masculine and feminine name given to the "full moon on its fourteenth night" or the ecclesiastical full moon.

Badr may refer to: .and it is also one of the oldest and rarest names in the Arabi ...

period, after a marketplace quarrel broke out between the Muslims and the Jews in Medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the Holiest sites in Islam, second-holiest city in Islam, ...

and Muhammad's negotiations with the tribe failed.

Following his defeat in the Battle of Uhud

The Battle of Uhud ( ar, غَزْوَة أُحُد, ) was fought on Saturday, 23 March 625 AD (7 Shawwal, 3 AH), in the valley north of Mount Uhud.Watt (1974) p. 136. The Qurayshi Meccans, led by Abu Sufyan ibn Harb, commanded an army of 3,000 ...

, Muhammad said he received a divine revelation that the Jewish tribe of the Banu Nadir

The Banu Nadir ( ar, بَنُو ٱلنَّضِير, he, בני נצ'יר) were a Jewish Arab tribe which lived in northern Arabia at the oasis of Medina until the 7th century. The tribe refused to convert to Islam as Muhammad had ordered it t ...

wanted to assassinate him. Muhammad besieged the Banu Nadir and expelled them from Medina. Muhammad also attacked the Jews of the Khaybar oasis near Medina and defeated them, after they had betrayed the Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

in a time of war, and he only allowed them to stay in the oasis on the condition that they deliver one-half of their annual produce to Muslims.

Anti-Jewish sentiments usually flared up during times of Muslim political or military weakness or when Muslims felt that some Jews had overstepped the boundaries of humiliation prescribed to them by Islamic law.Lewis (1999), p. 130; Gerber (1986), p. 83 In Spain, ibn Hazm and Abu Ishaq focused their anti-Jewish writings on the latter allegation. This was also the chief motivating factor behind the massacres of Jews in Granada

Granada (,, DIN: ; grc, Ἐλιβύργη, Elibýrgē; la, Illiberis or . ) is the capital city of the province of Granada, in the autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada mountains, at the c ...

in 1066, when nearly 3,000 Jews were killed, and in Fez in 1033, when 6,000 Jews were killed.Morris, Benny

Benny Morris ( he, בני מוריס; born 8 December 1948) is an Israeli historian. He was a professor of history in the Middle East Studies department of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in the city of Beersheba, Israel. He is a member of t ...

. ''Righteous Victims: A History of the Zionist-Arab Conflict, 1881-2001''. Vintage Books, 2001, pp. 10-11. There were further massacres in Fez in 1276 and 1465.Gerber (1986), p. 84

Islamic law does not differentiate between Jews and Christians in their status as ''dhimmi

' ( ar, ذمي ', , collectively ''/'' "the people of the covenant") or () is a historical term for non-Muslims living in an Islamic state with legal protection. The word literally means "protected person", referring to the state's obligatio ...

s''. According to Bernard Lewis

Bernard Lewis, (31 May 1916 – 19 May 2018) was a British American historian specialized in Oriental studies. He was also known as a public intellectual and political commentator. Lewis was the Cleveland E. Dodge Professor Emeritus of Near ...

, the normal practice of Muslim governments until modern times was consistent with this aspect of sharia

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the H ...

law. This view is countered by Jane Gerber, who maintains that of all dhimmis, Jews had the lowest status. Gerber maintains that this situation was especially pronounced in the latter centuries in the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

, where Christian communities enjoyed protection from the European countries, which was unavailable to the Jews. For example, in 18th-century Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

, a Muslim noble held a festival, inviting to it all social classes in descending order, according to their social status: the Jews outranked only the peasants and the prostitutes.

Jews in Islamic texts

Leon Poliakov

Leon, Léon (French) or León (Spanish) may refer to:

Places

Europe

* León, Spain, capital city of the Province of León

* Province of León, Spain

* Kingdom of León, an independent state in the Iberian Peninsula from 910 to 1230 and again fro ...

,Poliakov Walter Laqueur

Walter Ze'ev Laqueur (26 May 1921 – 30 September 2018) was a German-born American historian, journalist and political commentator. He was an influential scholar on the subjects of terrorism and political violence.

Biography

Walter Laqueur was ...

, and Jane Gerber

Jane S. Gerber (born 1938) is a professor of Jewish history and director of the Institute for Sephardic Studies at the City University of New York.

Life and education

Gerber, née Jane Satlow was born in 1938 to Israeli mother Elise Kliegman ...

, suggest that later passages in the Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , ...

contain very sharp attacks on Jews for their refusal to recognize Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mon ...

as a prophet

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings from the ...

of God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

. There are also Quranic verses, particularly from the earliest Quranic sura

A ''surah'' (; ar, سورة, sūrah, , ), is the equivalent of "chapter" in the Qur'an. There are 114 ''surahs'' in the Quran, each divided into '' ayats'' (verses). The chapters or ''surahs'' are of unequal length; the shortest surah ('' Al-K ...

hs, showing respect for the Jews (e.g. see , )Poliakov (1961), pg. 27 and preaching tolerance (e.g. see ).Laqueur 192 This positive view tended to disappear in the later Surahs. Taking it all together, the Quran differentiates between "good and bad" Jews, Poliakov states. Laqueur argues that the conflicting statements about Jews in the Muslim holy text have defined Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

and Muslim attitudes towards Jews to this day, especially during periods of rising Islamic fundamentalism

Islamic fundamentalism has been defined as a puritanical, revivalist, and reform movement of Muslims who aim to return to the founding scriptures of Islam. Islamic fundamentalists are of the view that Muslim-majority countries should return ...

.

Differences with Christianity

Bernard Lewis

Bernard Lewis, (31 May 1916 – 19 May 2018) was a British American historian specialized in Oriental studies. He was also known as a public intellectual and political commentator. Lewis was the Cleveland E. Dodge Professor Emeritus of Near ...

holds that Muslims were not antisemitic in the way Christians were for the most part because:

# The Gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christian message (" the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words a ...

s are not part of the educational system in Muslim societies and therefore, Muslims are not brought up with the stories of Jewish deicide

Jewish deicide is the notion that the Jews as a people were collectively responsible for the killing of Jesus. A Biblical justification for the charge of Jewish deicide is derived from Matthew 27:24–25. Some rabbinical authorities, such as Ma ...

; on the contrary, the notion of deicide is rejected by the Quran as a blasphemous absurdity.

# Muhammad and his early followers were not Jews and therefore, they did not present themselves as the true Israel or feel threatened by the survival of the old Israel.

# The Quran was not viewed by Muslims as a fulfillment of the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

'' Judaism Judaism ( he, ''Yahăḏūṯ'') is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in th ...

and Islam could arise.

# Muhammad was not killed by the Jewish community and he was ultimately victorious in his clash with the Jewish community in Medina.

# Muhammad did not claim to be either the Son of God or the Messiah. Instead, he claimed that he was only a prophet; a claim which Jews repudiated less.

# Muslims saw the conflict between Muhammad and the Jews as something of minor importance in Muhammad's career.Lewis (1999), pp. 117-118

'' Judaism Judaism ( he, ''Yahăḏūṯ'') is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in th ...

Status of Jews under Muslim rule

Traditionally Jews living in Muslim lands, known (along with Christians) asdhimmis

' ( ar, ذمي ', , collectively ''/'' "the people of the covenant") or () is a historical term for non-Muslims living in an Islamic state with legal protection. The word literally means "protected person", referring to the state's obligatio ...

, were allowed to practice their religion and to administer their internal affairs, subject to certain conditions.Lewis (1984), pp.10,20 They had to pay the jizya

Jizya ( ar, جِزْيَة / ) is a per capita yearly taxation historically levied in the form of financial charge on dhimmis, that is, permanent non-Muslim subjects of a state governed by Islamic law. The jizya tax has been understood in ...

(a per capita tax imposed on free adult non-Muslim males) to Muslims. Dhimmis had an inferior status under Islamic rule. They had several social and legal disabilities

Disability is the experience of any condition that makes it more difficult for a person to do certain activities or have equitable access within a given society. Disabilities may be cognitive, developmental, intellectual, mental, physical, ...

such as prohibitions against bearing arms or giving testimony in courts in cases involving Muslims. The most degrading one was the requirement of distinctive clothing, not found in the Quran or hadith but invented in early medieval

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

; its enforcement was highly erratic. Jews rarely faced martyrdom or exile, or forced compulsion to change their religion, and they were mostly free in their choice of residence and profession.

The notable examples of massacre of Jews include the 1066 Granada massacre

The 1066 Granada massacre took place on 30 December 1066 (9 Tevet 4827; 10 Safar 459 AH) when a Muslim mob stormed the royal palace in Granada, in the Taifa of Granada, killed and crucified the Jewish vizier Joseph ibn Naghrela, and massacred m ...

, when a Muslim mob stormed the royal palace in Granada

Granada (,, DIN: ; grc, Ἐλιβύργη, Elibýrgē; la, Illiberis or . ) is the capital city of the province of Granada, in the autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada mountains, at the c ...

, crucified

Crucifixion is a method of capital punishment in which the victim is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross or beam and left to hang until eventual death from exhaustion and asphyxiation. It was used as a punishment by the Persians, Carthagin ...

Jewish vizier

A vizier (; ar, وزير, wazīr; fa, وزیر, vazīr), or wazir, is a high-ranking political advisor or minister in the near east. The Abbasid caliphs gave the title ''wazir'' to a minister formerly called '' katib'' (secretary), who was ...

Joseph ibn Naghrela

Joseph is a common male given name, derived from the Hebrew Yosef (יוֹסֵף). "Joseph" is used, along with "Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the mo ...

and massacred most of the Jewish population of the city. "More than 1,500 Jewish families, numbering 4,000 persons, fell in one day."Granadaby Richard Gottheil, Meyer Kayserling, ''

Jewish Encyclopedia

''The Jewish Encyclopedia: A Descriptive Record of the History, Religion, Literature, and Customs of the Jewish People from the Earliest Times to the Present Day'' is an English-language encyclopedia containing over 15,000 articles on th ...

''. 1906 ed. This was the first persecution of Jews on the Peninsula under Islamic rule. There was also the killing or forcibly conversion of them by the rulers of the Almohad

The Almohad Caliphate (; ar, خِلَافَةُ ٱلْمُوَحِّدِينَ or or from ar, ٱلْمُوَحِّدُونَ, translit=al-Muwaḥḥidūn, lit=those who profess the unity of God) was a North African Berber Muslim empire fou ...

dynasty in Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the M ...

in the 12th century. Notable examples of the cases where the choice of residence was taken away from them includes confining Jews to walled quarters (mellah

A ''mellah'' ( or 'saline area'; and he, מלאח) is a Jewish quarter of a city in Morocco. Starting in the 15th century and especially since the beginning of the 19th century, Jewish communities in Morocco were constrained to live in ''mellah' ...

s) in Morocco beginning from the 15th century and especially since the early 19th century. Most conversions were voluntary and happened for various reasons. However, there were some forced conversions in the 12th century under the Almohad

The Almohad Caliphate (; ar, خِلَافَةُ ٱلْمُوَحِّدِينَ or or from ar, ٱلْمُوَحِّدُونَ, translit=al-Muwaḥḥidūn, lit=those who profess the unity of God) was a North African Berber Muslim empire fou ...

dynasty of North Africa and al-Andalus as well as in Persia.

Medieval period

The portrayal of the Jews in the early Islamic texts played a key role in shaping the attitudes towards them in the Muslim societies. According toJane Gerber

Jane S. Gerber (born 1938) is a professor of Jewish history and director of the Institute for Sephardic Studies at the City University of New York.

Life and education

Gerber, née Jane Satlow was born in 1938 to Israeli mother Elise Kliegman ...

, "the Muslim is continually influenced by the theological threads of anti-Semitism embedded in the earliest chapters of Islamic history." In the light of the Jewish defeat at the hands of Muhammad, Muslims traditionally viewed Jews with contempt and as objects of ridicule. Jews were seen as hostile, cunning, and vindictive, but nevertheless weak and ineffectual. Cowardice was the quality most frequently attributed to Jews. Another stereotype associated with the Jews was their alleged propensity to trickery and deceit. While most anti-Jewish polemicists saw those qualities as inherently Jewish, Ibn Khaldun

Ibn Khaldun (; ar, أبو زيد عبد الرحمن بن محمد بن خلدون الحضرمي, ; 27 May 1332 – 17 March 1406, 732-808 AH) was an Arab

The Historical Muhammad', Irving M. Zeitlin, (Polity Press, 2007), p. 21; "It is, of ...

attributed them to the mistreatment of Jews at the hands of the dominant nations. For that reason, says ibn Khaldun, Jews "are renowned, in every age and climate, for their wickedness and their slyness".

Some Muslim writers have inserted racial overtones in their anti-Jewish polemics. Al-Jahiz

Abū ʿUthman ʿAmr ibn Baḥr al-Kinānī al-Baṣrī ( ar, أبو عثمان عمرو بن بحر الكناني البصري), commonly known as al-Jāḥiẓ ( ar, links=no, الجاحظ, ''The Bug Eyed'', born 776 – died December 868/Jan ...

speaks of the deterioration of the Jewish stock due to excessive inbreeding. Ibn Hazm

Abū Muḥammad ʿAlī ibn Aḥmad ibn Saʿīd ibn Ḥazm ( ar, أبو محمد علي بن احمد بن سعيد بن حزم; also sometimes known as al-Andalusī aẓ-Ẓāhirī; 7 November 994 – 15 August 1064Ibn Hazm. ' (Preface). Tr ...

also implies racial qualities in his attacks on the Jews. However, these were exceptions, and the racial theme left little or no trace in the medieval Muslim anti-Jewish writings.

Anti-Jewish sentiments usually flared up at times of the Muslim political or military weakness or when Muslims felt that some Jews had overstepped the boundary of humiliation prescribed to them by the Islamic law. In Moorish Iberia, ibn Hazm and Abu Ishaq focused their anti-Jewish writings on the latter allegation. This was also the chief motivation behind the 1066 Granada massacre, when " re than 1,500 Jewish families, numbering 4,000 persons, fell in one day", and in Fez in 1033, when 6,000 Jews were killed. There were further massacres in Fez in 1276 and 1465.

Islamic law does not differentiate between Jews and Christians in their status as dhimmis. According to Bernard Lewis

Bernard Lewis, (31 May 1916 – 19 May 2018) was a British American historian specialized in Oriental studies. He was also known as a public intellectual and political commentator. Lewis was the Cleveland E. Dodge Professor Emeritus of Near ...

, the normal practice of Muslim governments until modern times was consistent with this aspect of sharia

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the H ...

law.Lewis (1999), p. 128 This view is countered by Jane Gerber, who maintains that of all dhimmis, Jews had the lowest status. Gerber maintains that this situation was especially pronounced in the latter centuries, when Christian communities enjoyed protection, unavailable to the Jews, under the provisions of Capitulations of the Ottoman Empire

Capitulations of the Ottoman Empire were contracts between the Ottoman Empire and other powers in Europe, particularly France. Turkish capitulations, or Ahidnâmes were generally bilateral acts whereby definite arrangements were entered int ...

. For example, in 18th century Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

, a Muslim noble held a festival, inviting to it all social classes in descending order, according to their social status: the Jews outranked only the peasants and prostitutes. In 1865, when the equality of all subjects of the Ottoman Empire was proclaimed, Ahmed Cevdet Pasha

Ahmed Cevdet Pasha or Jevdet Pasha in English (22 March 1822 – 25 May 1895) was an Ottoman scholar, intellectual, bureaucrat, administrator, and historian who was a prominent figure in the Tanzimat reforms of the Ottoman Empire. He was the h ...

, a high-ranking official observed: "whereas in former times, in the Ottoman State, the communities were ranked, with the Muslims first, then the Greeks, then the Armenians, then the Jews, now all of them were put on the same level. Some Greeks objected to this, saying: 'The government has put us together with the Jews. We were content with the supremacy of Islam.

Some scholars have questioned the correctness of the term "antisemitism" to Muslim culture in pre-modern times. Robert Chazan and Alan Davies argue that the most obvious difference between pre-modern Islam and pre-modern Christendom was the "rich melange of racial, ethic, and religious communities" in Islamic countries, within which "the Jews were by no means obvious as lone dissenters, as they had been earlier in the world of polytheism or subsequently in most of medieval Christendom." According to Chazan and Davies, this lack of uniqueness ameliorated the circumstances of Jews in the medieval world of Islam. According to Norman Stillman

Norman Stillman, Bar-Ilan University

Norman Arthur Stillman, also Noam (נועם, in Hebrew), b. 1945, is an American academic, historian, and Orientalist, serving as the emeritus Schusterman-Josey Professor and emeritus Chair of Judaic Histo ...

, antisemitism, understood as hatred of Jews as Jews, "did exist in the medieval Arab world even in the period of greatest tolerance". Also see Bostom, Bat Ye'or, and the CSPI issued text, supporting Stillman and cited in the bibliography.

Nineteenth century

Historian Martin Gilbert writes that in the 19th century the position of Jews worsened in Muslim countries. There was a massacre of Jews inBaghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

in 1828 and in 1839, in the eastern Persian city of Meshed, a mob burst into the Jewish Quarter, burned the synagogue, and destroyed the Torah scrolls