Religion in Black America on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Religion of black Americans refers to the religious and spiritual practices of African Americans. Historians generally agree that the religious life of black Americans "forms the foundation of their community life". Before 1775 there was scattered evidence of organized religion among black people in the

Religion of black Americans refers to the religious and spiritual practices of African Americans. Historians generally agree that the religious life of black Americans "forms the foundation of their community life". Before 1775 there was scattered evidence of organized religion among black people in the

In 1787, Richard Allen and his colleagues in Philadelphia broke away from the

In 1787, Richard Allen and his colleagues in Philadelphia broke away from the  After the Civil War Bishop

After the Civil War Bishop

Giggie finds that black Methodists and Baptists sought middle class respectability. In sharp contrast the new Holiness Pentecostalism, in addition to the Holiness Methodist belief in entire sanctification, which was based on a sudden religious experience that could empower people to avoid sin, also taught a belief in a

Giggie finds that black Methodists and Baptists sought middle class respectability. In sharp contrast the new Holiness Pentecostalism, in addition to the Holiness Methodist belief in entire sanctification, which was based on a sudden religious experience that could empower people to avoid sin, also taught a belief in a

Arnold, Bruce Makoto. "Shepherding a Flock of a Different Fleece: A Historical and Social Analysis of the Unique Attributes of the African American Pastoral Caregiver." The Journal of Pastoral Care and Counseling 66, no. 2 (June 2012).

* Brooks, Walter H. "The Evolution of the Negro Baptist Church." ''Journal of Negro History'' (1922) 7#1 pp. 11–22

in JSTOR

* Brunner, Edmund D. ''Church Life in the Rural South'' (1923) pp. 80–92, based on the survey in the early 1920s of 30 communities across the rural South * Calhoun-Brown, Allison. "The image of God: Black theology and racial empowerment in the African American community." ''Review of Religious Research'' (1999): 197–212

in JSTOR

* Chapman, Mark L. ''Christianity on trial: African-American religious thought before and after Black power'' (2006) * Collier-Thomas, Bettye. ''Jesus, jobs, and justice: African American women and religion'' (2010) * Curtis, Edward E. "African-American Islamization Reconsidered: Black history Narratives and Muslim identity." ''Journal of the American Academy of Religion'' (2005) 73#3 pp. 659–84. * Davis, Cyprian. ''The History of Black Catholics in the United States'' (1990). * Fallin Jr., Wilson. ''Uplifting the People: Three Centuries of Black Baptists in Alabama'' (2007) * Fitts, Leroy. ''A history of black Baptists'' (Broadman Press, 1985) * Frey, Sylvia R. and

online

basic introduction * Raboteau, Albert J. ''Canaan land: A religious history of African Americans'' (2001). * Salvatore, Nick. ''Singing in a Strange Land: C. L. Franklin, the Black Church, and the Transformation of America'' (2005) on the politics of the National Baptist Convention * Sensbach, Jon F. ''Rebecca’s Revival: Creating Black Christianity in the Atlantic World'' (2005) * Smith, R. Drew, ed. ''Long March ahead: African American churches and public policy in post-civil rights America'' (2004). * Sobel, M. '' Trabelin’ On: The Slave Journey to an Afro-Baptist Faith'' (1979) * Southern, Eileen. ''The Music of Black Americans: A History'' (1997) * Spencer, Jon Michael. ''Black hymnody: a hymnological history of the African-American church'' (1992) * Wills, David W. and Richard Newman, eds. ''Black Apostles at Home and Abroad: Afro-Americans and the Christian Mission from the Revolution to Reconstruction'' (1982) *Woodson, Carter. ''The History of the Negro Church'' (1921

online free

comprehensive history by leading black scholar * Yong, Amos, and Estrelda Y. Alexander. ''Afro-Pentecostalism: Black Pentecostal and Charismatic Christianity in History and Culture'' (2012)

in JSTOR

Religion of black Americans refers to the religious and spiritual practices of African Americans. Historians generally agree that the religious life of black Americans "forms the foundation of their community life". Before 1775 there was scattered evidence of organized religion among black people in the

Religion of black Americans refers to the religious and spiritual practices of African Americans. Historians generally agree that the religious life of black Americans "forms the foundation of their community life". Before 1775 there was scattered evidence of organized religion among black people in the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th cent ...

. The Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's ...

and Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compe ...

churches became much more active in the 1780s. Their growth was quite rapid for the next 150 years, until their membership included the majority of black Americans.

After Emancipation

Emancipation generally means to free a person from a previous restraint or legal disability. More broadly, it is also used for efforts to procure economic and social rights, political rights or equality, often for a specifically disenfranch ...

in 1863, Freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), emancipation (granted freedom a ...

organized their own churches, chiefly Baptist, followed by Methodists. Other Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

denominations, and the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, played smaller roles. In the 19th century, the Wesleyan-Holiness movement

The Holiness movement is a Christian movement that emerged chiefly within 19th-century Methodism, and to a lesser extent other traditions such as Quakerism, Anabaptism, and Restorationism. The movement is historically distinguished by its emph ...

, which emerged in Methodism, as well as Holiness Pentecostalism in the 20th century were important, and later the Jehovah's Witnesses. The Nation of Islam and el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz (also known as Malcolm X

Malcolm X (born Malcolm Little, later Malik el-Shabazz; May 19, 1925 – February 21, 1965) was an American Muslim minister and human rights activist who was a prominent figure during the civil rights movement. A spokesman for the Nation of I ...

) added a Muslim factor in the 20th century. Powerful pastor

A pastor (abbreviated as "Pr" or "Ptr" , or "Ps" ) is the leader of a Christian congregation who also gives advice and counsel to people from the community or congregation. In Lutheranism, Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy and ...

s often played prominent roles in politics, often through their leadership in the American civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the Unite ...

, as typified by Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

, Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton

Alfred Charles Sharpton Jr. (born October 3, 1954) is an American civil rights activist, Baptist minister, talk show host and politician. Sharpton is the founder of the National Action Network. In 2004, he was a candidate for the Democrati ...

.

Religious demographics

The vast majority of Black Americans are Protestants, with descendants of American chattel slavery being largely Baptists or adhering to other forms ofEvangelical Protestantism

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide interdenominational movement within Protestant Christianity that affirms the centrality of being "born again", in which an individual experi ...

. A 2007 Pew Research survey found that African-Americans were more religious than the U.S. population as a whole. 87% of African Americans were affiliated with a religion, compared with 83% of the wider population. 79% of African Americans stated that "religion is very important in their life", compared to 56% of the wider US population.

83% of Black Americans identified as Christian, including 45% who identified as baptist. Catholics accounted for 5% of the population. 1% of black Americans identified as Muslims. About 12% of African American people didn't identify with an established religion and identified as either unaffiliated, atheist or agnostic, slightly lower than the figure for the whole of the US.

In 2019 there were approximately three million African American Catholics in the US, 24% of whom worshiped in the country's 798 predominantly African American parishes.

History

Colonial era

Africans brought religion with them from Africa, including Islam, Catholicism, and traditional religions. In the 1770s no more than 1% of black people in the United States had connections with organized churches. The numbers grew rapidly after 1789. TheAnglican Church

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the ...

had made a systematic effort to proselytize, especially in Virginia, and to spread information about Christianity, and the ability to read the Bible, without making many converts.

No organized Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

n religious practices are known to have taken place in the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th cent ...

. In the mid-20th century scholars debated whether there were distinctive African elements embedded in black American religious practices, as in music and dancing. Scholars no longer look for such cultural transfers regarding religion.

Muslims practiced Islam surreptitiously or underground throughout the era of the enslavement of African people in North America. The story of Abdul Rahman Ibrahima Sori

Abdul Rahman Ibrahima ibn Sori ( ar, عبد الرحمن ابراهيم سوري; 1762—July 6, 1829) was a prince and Amir (commander) from the Fouta Djallon region of Guinea, West Africa, who was captured and sold to slave trad ...

, a Muslim prince from West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, M ...

who spent 40 years enslaved in the United States from 1788 onwards before being freed, demonstrates the survival of Muslim belief and practice among enslaved Africans in America.

Prior to the American Revolution, masters and revivalists spread Christianity to slave communities, including Catholicism in Spanish Florida and California, and in French and Spanish Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

, and Protestantism in English colonies, supported by the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel

United Society Partners in the Gospel (USPG) is a United Kingdom-based charitable organization (registered charity no. 234518).

It was first incorporated under Royal Charter in 1701 as the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Part ...

.

In the First Great Awakening

The First Great Awakening (sometimes Great Awakening) or the Evangelical Revival was a series of Christian revivals that swept Britain and its thirteen North American colonies in the 1730s and 1740s. The revival movement permanently affecte ...

(ca. 1730–1755) Baptists were drawing Virginians, especially poor-white farmers, into a new, much more democratic religion. Baptist gatherings made slaves welcome at their services, and a few Baptist congregations contained as many as 25% slaves. Baptists and Methodists from New England preached a message against slavery, encouraged masters to free their slaves, converted both slaves and free blacks, and gave them active roles in new congregations. The first independent black congregations were started in the South before the Revolution, in South Carolina and Georgia. Believing that, "slavery was contrary to the ethics of Jesus", Christian congregations and church clergy, especially in the North, played a role in the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. ...

, especially Wesleyan Methodists The Wesleyan Church is a Methodist Christian denomination aligned with the holiness movement.

Wesleyan Church may also refer to:

* Wesleyan Methodist Church of Australia, the Australian branch of the Wesleyan Church

Denominations

* Allegheny We ...

, Quakers and Congregationalists.

White clergy within evangelical Protestantism actively promoted the idea that all Christians were equal in the sight of God, a message that provided hope and sustenance to oppressed slaves.

Over the decades and with the growth of slavery throughout the South, some Baptist and Methodist ministers gradually changed their messages to accommodate the institution. After 1830, white Southerners

White Southerners, from the Southern United States, are considered an ethnic group by some historians, sociologists and journalists, although this categorization has proven controversial, and other academics have argued that Southern identity do ...

argued for the compatibility of Christianity and slavery, with a multitude of both Old and New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Chri ...

citations. They promoted Christianity as encouraging better treatment of slaves and argued for a paternalistic approach. In the 1840s and 1850s, the issue of accepting slavery split the nation's largest religious denominations (the Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's ...

, Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compe ...

and Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

churches) into separate Northern and Southern organizations; see Methodist Episcopal Church, South, Southern Baptist Convention, and Presbyterian Church in the Confederate States of America

The Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS, originally Presbyterian Church in the Confederate States of America) was a Protestant denomination in the Southern and border states of the United States that existed from 1861 to 1983. That y ...

). Schisms occurred, such as that between the Wesleyan Methodist Church and the Methodist Episcopal Church

The Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC) was the oldest and largest Methodist denomination in the United States from its founding in 1784 until 1939. It was also the first religious denomination in the US to organize itself on a national basis. In ...

.

Southern slaves generally attended their masters' white churches, where they often outnumbered the white congregants. They were usually permitted to sit only in the back or in the balcony. They listened to white preachers, who emphasized the obligation of slaves to keep in their place, and acknowledged the slave's identity as both person and property. Preachers taught the master's responsibility and the concept of appropriate paternal treatment, using Christianity to improve conditions for slaves, and to treat them "justly and fairly" (Col. 4:1). This included masters having self-control, not disciplining under anger, not threatening, and ultimately fostering Christianity among their slaves by example.

Slaves also created their own religious observances, meeting alone without the supervision of their white masters or ministers. The larger plantations with groups of slaves numbering 20, or more, tended to be centers of nighttime meetings of one or several plantation slave populations. These congregations revolved around a singular preacher, often illiterate with limited knowledge of theology, who was marked by his personal piety and ability to foster a spiritual environment. African Americans developed a theology related to Biblical stories having the most meaning for them, including the hope for deliverance from slavery by their own Exodus. One lasting influence of these secret congregations is the African American spiritual.

Black religious music

Religious music (also sacred music) is a type of music that is performed or composed for religious use or through religious influence. It may overlap with ritual music, which is music, sacred or not, performed or composed for or as ritual. Relig ...

is distinct from traditional European religious music; it uses dances and ring shout

A shout or ring shout is an ecstatic, transcendent religious ritual, first practiced by African slaves in the West Indies and the United States, in which worshipers move in a circle while shuffling and stomping their feet and clapping their hands. ...

s, and emphasizes emotion and repetition more intensely.

Formation of churches (18th century)

Scholars disagree about the extent of the native African content of black Christianity as it emerged in 18th-century America, but there is no dispute that the Christianity of the black population was grounded in evangelicalism. Central to the growth of community among black people was theblack church

The black church (sometimes termed Black Christianity or African American Christianity) is the faith and body of Christian congregations and denominations in the United States that minister predominantly to African Americans, as well as their ...

, usually the first community institution to be established. Starting around 1800 with the African Methodist Episcopal Church

The African Methodist Episcopal Church, usually called the AME Church or AME, is a predominantly African American Methodist denomination. It adheres to Wesleyan-Arminian theology and has a connexional polity. The African Methodist Episcopal ...

, African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church and other churches, the black church grew to be the focal point of the black community. The black church was both an expression of community and unique African-American spirituality, and a reaction to discrimination.Albert J. Raboteau, ''Canaan Land: A Religious History of African Americans'' (2001)

The church also served as neighborhood centers where free black people could celebrate their African heritage without intrusion by white detractors. The church also the center of education. Since the church was part of the community and wanted to provide education; they educated the freed and enslaved black community. Seeking autonomy, some black religious leaders like Richard Allen founded separate black denominations.

The Second Great Awakening

The Second Great Awakening was a Protestant religious revival during the early 19th century in the United States. The Second Great Awakening, which spread religion through revivals and emotional preaching, sparked a number of reform movements. R ...

(1800–20s) has been called the "central and defining event in the development of Afro-Christianity".

Free black religious leaders also established black churches in the South before 1860. After the Great Awakening, many black Christians joined the Baptist Church, which allowed for their participation, including roles as elders and preachers. For instance, First Baptist Church and Gillfield Baptist Church of Petersburg, Virginia

Petersburg is an independent city (United States), independent city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. As of the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census, the population was 33,458. The Bureau of Econ ...

, both had organized congregations by 1800 and were the first Baptist churches in the city.

Preaching

Historian Bruce Arnold argues that successful black pastors historically undertook multiple roles. These include: *The black pastor is the paterfamilias of his church, responsible for shepherding and holding the community together, passing on its history and traditions, and acting as spiritual leader, wise counselor, and prophetic guide. *The black pastor is a counselor and comforter stressing transforming, sustaining, and nurturing abilities of God to help the flock through times of discord, doubts, and counsels them to protect themselves against emotional deterioration. *The black pastor is a community organizer and intermediary. Raboteau describes a common style of black preaching first developed in the early nineteenth century, and common throughout the 20th and into the 21st centuries: :The preacher begins calmly, speaking in conversational, if oratorical and occasionally grandiloquent, prose; he then gradually begins to speak more rapidly, excitedly, and to chant his words and time to a regular beat; finally, he reaches an emotional peak in which the chanted speech becomes tonal and merges with the singing, clapping, and shouting of the congregation. Many Americans interpreted great events in religious terms. Historian Wilson Fallin contrasts the interpretation of theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

and Reconstruction in white versus black Baptist sermons in Alabama. White Baptists expressed the view that:

: God had chastised them and given them a special mission – to maintain orthodoxy, strict biblicism, personal piety, and traditional race relations. Slavery, they insisted, had not been sinful. Rather, emancipation was a historical tragedy and the end of Reconstruction was a clear sign of God's favor.

In sharp contrast, black Baptists interpreted the Civil War, Emancipation and Reconstruction as:

: God's gift of freedom. They appreciated opportunities to exercise their independence, to worship in their own way, to affirm their worth and dignity, and to proclaim the fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man. Most of all, they could form their own churches, associations, and conventions. These institutions offered self-help and racial uplift, and provided places where the gospel of liberation could be proclaimed. As a result, black preachers continued to insist that God would protect and help him; God would be their rock in a stormy land.

Black sociologist Benjamin Mays analyzed the content of sermons in the 1930s and concluded:

:They are conducive to developing in the Negro a complacent, laissez-faire attitude toward life. They support the view that God in His good time and in His own way will bring about the conditions that will lead to the fulfillment of social needs. They encourage Negroes to feel that God will see to it that things work out all right; if not in this world, certainly in the world to come. They make God influential chiefly in the beyond, and preparing a home for the faithful – a home where His suffering servants will be free of the trials and tribulations which beset them on earth.

After 1865

Black Americans, once freed from slavery, were very active in forming their own churches, most of them Baptist or Methodist, and giving their ministers both moral and political leadership roles. In a process of self-segregation, practically all black Americans left white churches so that few racially integrated congregations remained (apart from some Catholic churches in Louisiana). Four main organizations competed with each other across the South to form new Methodist churches composed of freedmen. They were theAfrican Methodist Episcopal Church

The African Methodist Episcopal Church, usually called the AME Church or AME, is a predominantly African American Methodist denomination. It adheres to Wesleyan-Arminian theology and has a connexional polity. The African Methodist Episcopal ...

; the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church; the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church

The Christian Methodist Episcopal (C.M.E.) Church is a historically black denomination within the broader context of Wesleyan Methodism founded and organized by John Wesley in England in 1744 and established in America as the Methodist Episcopal ...

(founded 1870 and composed of the former black members of the white Methodist Episcopal Church, South) and the well-funded Methodist Episcopal Church

The Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC) was the oldest and largest Methodist denomination in the United States from its founding in 1784 until 1939. It was also the first religious denomination in the US to organize itself on a national basis. In ...

(Northern white Methodists), which organized Mission Conferences. By 1871 the Northern Methodists had 88,000 black members in the South, and had opened numerous schools for them.

African-Americans during Reconstruction Era were politically the core element of the Republican Party and the minister played a powerful political role. Their ministers had powerful political roles that were distinctive since they did not primarily depend on white support, in contrast to teachers, politicians, businessmen, and tenant farmers. Acting on the principle expounded by Charles H. Pearce, an AME minister in Florida: "A man in this State cannot do his whole duty as a minister except he looks out for the political interests of his people," over 100 black ministers were elected to state legislatures during Reconstruction. Several served in Congress and one, Hiram Revels, in the U.S. Senate.

Urban churches

The great majority of African-Americans lived in rural areas where services were held in small makeshift buildings. In the cities black churches were more visible. Besides their regular religious services, the urban churches had numerous other activities, such as scheduled prayer meetings, missionary societies, women's clubs, youth groups, public lectures, and musical concerts. Regularly scheduled revivals operated over a period of weeks reaching large and appreciative crowds.Howard N. Rabinowitz, ''Race Relations in the Urban South: 1865–1890'' (1978), pp. 208–13 Charitable activities abounded concerning the care of the sick and needy. The larger churches had a systematic education program, besides the Sunday schools, and Bible study groups. They held literacy classes to enable older members to read the Bible. Private black colleges, such as Fisk in Nashville, often began in the basement of the churches. Church supported the struggling small business community. Most important was the political role. Churches hosted protest meetings, rallies, and Republican party conventions. Prominent laymen and ministers negotiated political deals, and often ran for office until disfranchisement took effect in the 1890s. In the 1880s, the prohibition of liquor was a major political concern that allowed for collaboration with like-minded white Protestants. In every case, the pastor was the dominant decision-maker. His salary ranged from $400 a year to upwards of $1500, plus housing – at a time when 50 cents a day was good pay for unskilled physical labor. Increasingly the Methodists reached out to college or seminary graduates for their ministers, but most of Baptists felt that education was a negative factor that undercut the intense religiosity and oratorical skills they demanded of their ministers. After 1910, as black people migrated to major cities in both the North and the South, there emerged the pattern of a few very large churches with thousands of members and a paid staff, headed by an influential preacher. At the same time there were many "storefront" churches with a few dozen members.Historically black Christian denominations

Methodism (inclusive of the holiness movement)

African Methodist Episcopal Church

In 1787, Richard Allen and his colleagues in Philadelphia broke away from the

In 1787, Richard Allen and his colleagues in Philadelphia broke away from the Methodist Episcopal Church

The Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC) was the oldest and largest Methodist denomination in the United States from its founding in 1784 until 1939. It was also the first religious denomination in the US to organize itself on a national basis. In ...

and in 1816 founded the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME). It began with 8 clergy and 5 churches, and by 1846 had grown to 176 clergy, 296 churches, and 17,375 members. The 20,000 members in 1856 were located primarily in the North. AME national membership (including probationers and preachers) jumped from 70,000 in 1866 to 207,000 in 1876

AME put a high premium on education. In the 19th century, the AME Church of Ohio collaborated with the Methodist Episcopal Church, a predominantly white denomination, in sponsoring the second independent historically black college (HBCU), Wilberforce University

Wilberforce University is a private historically black university in Wilberforce, Ohio. Affiliated with the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), it was the first college to be owned and operated by African Americans. It participates ...

in Ohio. By 1880, AME operated over 2,000 schools, chiefly in the South, with 155,000 students. For school houses they used church buildings; the ministers and their wives were the teachers; the congregations raised the money to keep schools operating at a time the segregated public schools were starved of funds.

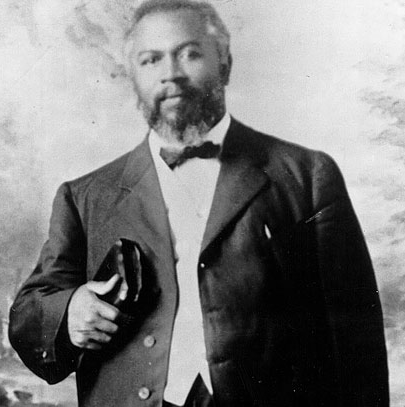

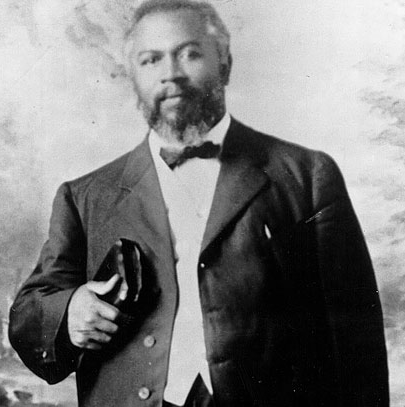

After the Civil War Bishop

After the Civil War Bishop Henry McNeal Turner

Henry McNeal Turner (February 1, 1834 – May 8, 1915) was an American minister, politician, and the 12th elected and consecrated bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME). After the American Civil War, he worked to establish new A.M ...

(1834–1915) was a major leader of the AME and played a role in Republican Party politics. In 1863 during the Civil War, Turner was appointed as the first black chaplain in the United States Colored Troops. Afterward, he was appointed to the Freedmen's Bureau in Georgia. He settled in Macon and was elected to the state legislature in 1868 during Reconstruction. He planted many AME churches in Georgia after the war.Stephen Ward Angell, ''Henry McNeal Turner and African-American Religion in the South'', (1992)

In 1880 he was elected as the first southern bishop of the AME Church after a fierce battle within the denomination. Angered by the Democrats' regaining power and instituting Jim Crow laws in the late nineteenth century South, Turner was the leader of black nationalism and proposed emigration of the black community to Africa.

In terms of social status, the Methodist churches have typically attracted the black leadership and the middle class. Like all American denominations, there were numerous schisms and new groups were formed every year.

African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church

The AMEZ denomination was officially formed in 1821 in New York City, but operated for a number of years before then. The total membership in 1866 was about 42,000. The church-sponsoredLivingstone College

Livingstone College is a private, historically black Christian college in Salisbury, North Carolina. It is affiliated with the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church. Livingstone College is accredited by the Commission on Colleges of the S ...

in Salisbury, North Carolina was founded to train missionaries for Africa. Today the AME Zion Church is especially active in mission work in Africa and the Caribbean, especially in Nigeria, Liberia, Malawi, Mozambique, Angola, Ivory Coast, Ghana, England, India, Jamaica, Virgin Islands, Trinidad, and Tobago.

Wesleyan-Holiness movement

The Holiness Movement emerged within the Methodist Church in the late 19th century. It emphasized the Methodist belief of " Christian perfection"–the belief that it is possible to live free of voluntary sin, and particularly by the belief that this may be accomplished instantaneously through asecond work of grace

According to some Christian traditions, a second work of grace (also second blessing) is a transforming interaction with God which may occur in the life of an individual Christian. The defining characteristics of the second work of grace are ...

. Although many within the holiness movement remained within the mainline Methodist Church, new denominations were established, such as the Free Methodist Church

The Free Methodist Church (FMC) is a Methodist Christian denomination within the holiness movement, based in the United States. It is evangelical in nature and is Wesleyan–Arminian in theology.

The Free Methodist Church has members in over 100 ...

, Wesleyan Methodist Church, and Church of God. The Wesleyan Methodist Church was founded to herald Methodist doctrine, in addition to promoting abolitionism.

The Church of God (Anderson, Indiana)

The Church of God (Anderson, Indiana) is a holiness Christian denomination with roots in Wesleyan-Arminianism and also in the restorationist traditions. The organization grew out of the evangelistic efforts of several Holiness evangelists in Ind ...

, with its beginnings in 1881, held that "interracial worship was a sign of the true Church", with both whites and blacks ministering regularly in Church of God congregations, which invited people of all races to worship there. Those who were entirely sanctified testified that they were "saved, sanctified, and prejudice removed". When Church of God ministers, such as Lena Shoffner, visited the camp meeting

The camp meeting is a form of Protestant Christian religious service originating in England and Scotland as an evangelical event in association with the communion season. It was held for worship, preaching and communion on the American frontier ...

s of other denominations, the rope in the congregation that separated whites and blacks was untied "and worshipers of both races approached the altar to pray". Though outsiders would sometimes attack Church of God services and camp meetings for their stand for racial equality, Church of God members were "undeterred even by violence" and "maintained their strong interracial position as the core of their message of the unity of all believers".

Other Methodist connexions

* African Union First Colored Methodist Protestant Church and Connection * African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church * Christian Methodist Episcopal Church *Church of Christ (Holiness) U.S.A.

The Church of Christ (Holiness) U.S.A. is a Holiness body of Christians headquartered in Jackson, Mississippi. In 2010, there were 14,000 members in 154 churches.

History

The Church of Christ (Holiness) U.S.A. shares a common early history wi ...

*Lumber River Conference of the Holiness Methodist Church

The Lumber River Conference of the Holiness Methodist Church is a Methodist connexion within the holiness movement.

The foundation of the Lumber River Conference of the Holiness Methodist Church is part of the history of Methodism in the United ...

Baptists

After the Civil War, black Baptists desiring to practice Christianity away from racial discrimination, rapidly set up separate churches and separate state Baptist conventions. In 1866, black Baptists of the South and West combined to form the Consolidated American Baptist Convention. This Convention eventually collapsed but three national conventions formed in response. In 1895 the three conventions merged to create the National Baptist Convention. It is now the largest African-American religious organization in the United States. Since the late 19th century to the present, a large majority of black Christians belong to Baptist churches. Baptist churches are locally controlled by the congregation, and select their own ministers. They choose local men – often quite young – with a reputation for religiosity, preaching skill, and ability to touch the deepest emotions of the congregations. Few were well-educated until the mid-twentieth century, when Bible Colleges became common. Until the late twentieth century, few of them were paid; most were farmers or had other employment. They became spokesman for their communities, and were among the few black people in the South allowed to vote in Jim Crow days before 1965. National Baptist Convention The National Baptist Convention was first organized in 1880 as the Foreign Mission Baptist Convention inMontgomery, Alabama

Montgomery is the capital city of the U.S. state of Alabama and the county seat of Montgomery County. Named for the Irish soldier Richard Montgomery, it stands beside the Alabama River, on the coastal Plain of the Gulf of Mexico. In the 202 ...

. Its founders, including Elias Camp Morris, stressed the preaching of the gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christian message (" the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words a ...

as an answer to the shortcomings of a segregated church. In 1895, Morris moved to Atlanta, Georgia

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,7 ...

, and founded the National Baptist Convention, USA, Inc., as a merger of the Foreign Mission Convention, the American National Baptist Convention, and the Baptist National Education Convention. The National Baptist Convention, USA, Inc., is the largest African-American religious organization.

The civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s was highly controversial in many black churches, where the minister preached spiritual salvation rather than political activism. The National Baptist Convention became deeply split. Its autocratic leader, Rev. Joseph H. Jackson had supported the Montgomery bus boycott of 1956, but by 1960 he told his denomination they should not become involved in civil rights activism.Peter J. Paris, ''Black Leaders in Conflict: Joseph H. Jackson, Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, Adam Clayton Powell, Jr.'' (1978); Nick Salvatore, ''Singing in a strange land: C.L. Franklin, the black church, and the transformation of America'' (2007)

Jackson was based in Chicago and was a close ally of Mayor Richard J. Daley

Richard Joseph Daley (May 15, 1902 – December 20, 1976) was an American politician who served as the Mayor of Chicago from 1955 and the chairman of the Cook County Democratic Party Central Committee from 1953 until his death. He has been cal ...

and the Chicago Democratic machine against the efforts of Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

and his aide the young Jesse Jackson Jr. (no relation to Joseph Jackson). In the end, King led his activists out of the National Baptist Convention into their own rival group, the Progressive National Baptist Convention

The Progressive National Baptist Convention (PNBC), incorporated as the Progressive National Baptist Convention, Inc., is a mainline predominantly African-American Baptist denomination emphasizing civil rights and social justice. The headquarte ...

, which supported the extensive activism of the King's Southern Christian Leadership Conference

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) is an African-American civil rights organization based in Atlanta, Georgia. SCLC is closely associated with its first president, Martin Luther King Jr., who had a large role in the American civ ...

.

Other Baptist denominations

*Full Gospel Baptist Church Fellowship

The Full Gospel Baptist Church Fellowship (FGBCF) or Full Gospel Baptist Church Fellowship International (FGBCFI) is a predominantly African-American Charismatic Baptist denomination established by Bishop Paul Sylvester Morton, a former National ...

* National Baptist Convention of America, Inc.

*National Missionary Baptist Convention of America

The National Missionary Baptist Convention of America (NMBCA) is an African-American Baptist convention.

History

The National Missionary Baptist Convention of America (NMBCA) was formed during a meeting attended by Dr. S. J. Gilbert, Sr. and Dr ...

*Progressive National Baptist Convention

The Progressive National Baptist Convention (PNBC), incorporated as the Progressive National Baptist Convention, Inc., is a mainline predominantly African-American Baptist denomination emphasizing civil rights and social justice. The headquarte ...

Pentecostalism

Giggie finds that black Methodists and Baptists sought middle class respectability. In sharp contrast the new Holiness Pentecostalism, in addition to the Holiness Methodist belief in entire sanctification, which was based on a sudden religious experience that could empower people to avoid sin, also taught a belief in a

Giggie finds that black Methodists and Baptists sought middle class respectability. In sharp contrast the new Holiness Pentecostalism, in addition to the Holiness Methodist belief in entire sanctification, which was based on a sudden religious experience that could empower people to avoid sin, also taught a belief in a third work of grace

In Christian theology, baptism with the Holy Spirit, also called baptism in the Holy Spirit or baptism in the Holy Ghost, has been interpreted by different Christian denominations and traditions in a variety of ways due to differences in the doctr ...

accompanied by glossolalia

Speaking in tongues, also known as glossolalia, is a practice in which people utter words or speech-like sounds, often thought by believers to be languages unknown to the speaker. One definition used by linguists is the fluid vocalizing of sp ...

. These groups stressed the role of the direct witness of the Holy Spirit, and emphasized the traditional emotionalism of black worship.

William J. Seymour, a black preacher, traveled to Los Angeles where his preaching sparked the three-year-long Azusa Street Revival

The Azusa Street Revival was a historic series of revival meetings that took place in Los Angeles, California. It was led by William J. Seymour, an African-American preacher. The revival began on April 9, 1906, and continued until roughly 1915. ...

in 1906. Worship at the racially integrated Azusa Mission featured an absence of any order of service. People preached and testified as moved by the Spirit, spoke and sung in tongues, and fell in the Spirit. The revival attracted both religious and secular media attention, and thousands of visitors flocked to the mission, carrying the "fire" back to their home churches.

The crowds of black people and white people worshiping together at Seymour's Azusa Street Mission set the tone for much of the early Pentecostal movement. Pentecostals defied social, cultural and political norms of the time that called for racial segregation and Jim Crow. Holiness Pentecostal denominations (the Church of God in Christ, the Church of God, the Pentecostal Holiness Church

The International Pentecostal Holiness Church (IPHC) or simply Pentecostal Holiness Church (PHC) is a Holiness-Pentecostal Christian denomination founded in 1911 with the merger of two older denominations. Historically centered in the Southeaste ...

), and the Pentecostal Assemblies of the World

The Pentecostal Assemblies of the World, Inc. (P.A.W.) is one of the world's largest Oneness Pentecostal denominations, and is headquartered in Indianapolis, Indiana. While it began in 1906 with Trinitarian beliefs, it was re-organized in 1916 a ...

(a Oneness Finished Work Pentecostal denomination) were all interracial denominations before the 1920s. These groups, especially in the Jim Crow South were under great pressure to conform to segregation.Synan, ''The Holiness–Pentecostal Tradition: Charismatic Movements in the Twentieth Century'' (1997) pp. 167–186.

Ultimately, North American Pentecostalism would divide into white and African-American branches. Though it never entirely disappeared, interracial worship within Pentecostalism would not reemerge as a widespread practice until after the Civil Rights Movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the Unite ...

. The Church of God in Christ (COGIC), an African American Pentecostal denomination founded in 1896, has become the largest Pentecostal denomination in the United States

today.

Other Pentecostal denominations

* Apostolic Faith Mission *Church of Our Lord Jesus Christ of the Apostolic Faith

The Church of Our Lord Jesus Christ of the Apostolic Faith is a Oneness Pentecostal church with headquarters in Manhattan. It was founded in 1919 by Robert C. Lawson.

The church's mission statement is: "To evangelize the world for Jesus Christ; ...

* Fire Baptized Holiness Church of God of the Americas

*Mount Sinai Holy Church of America

The Mount Sinai Holy Church of America(MSHCA), is a Christian church in the Holiness-Pentecostal tradition. The church is episcopal in governance. It has approximately 130 congregations in 14 states and 4 countries and a membership of over 50,000 ...

*Pentecostal Assemblies of the World

The Pentecostal Assemblies of the World, Inc. (P.A.W.) is one of the world's largest Oneness Pentecostal denominations, and is headquartered in Indianapolis, Indiana. While it began in 1906 with Trinitarian beliefs, it was re-organized in 1916 a ...

*United House of Prayer for All People

The United House of Prayer for All People of the Church on the Rock of the Apostolic Faith was founded by Cabo Verdean Marcelino Manuel da Graça. In 1919, Grace built the first United House of Prayer For All People in West Wareham, Massachusetts, ...

* United Pentecostal Council of the Assemblies of God, Incorporated

Non-Christian religions

African religions

The syncretist religionLouisiana Voodoo

Louisiana Voodoo (french: Vaudou louisianais, es, Vudú de Luisiana), also known as New Orleans Voodoo, is an African diasporic religion which originated in Louisiana, now in the southern United States. It arose through a process of syncreti ...

has traditionally been practiced by Creoles of color

The Creoles of color are a historic ethnic group of Creole people that developed in the former French and Spanish colonies of Louisiana (especially in the city of New Orleans), Mississippi, Alabama, and Northwestern Florida i.e. Pensacola, Flor ...

and African-Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of enslav ...

in Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

, while Hoodoo is a system of beliefs and rituals historically associated with Gullah

The Gullah () are an African American ethnic group who predominantly live in the Lowcountry region of the U.S. states of Georgia, Florida, South Carolina, and North Carolina, within the coastal plain and the Sea Islands. Their language and cultu ...

and Black Seminoles

The Black Seminoles, or Afro-Seminoles are Native American-Africans associated with the Seminole people in Florida and Oklahoma. They are mostly blood descendants of the Seminole people, free Africans, and escaped slaves, who allied with Seminole ...

. Hoodoo and Voudou are still active religions in African-American communities in the United States, and there is a reclamation of these traditions by African-American youth.

Islam

Historically, between 15% and 30% of enslaved Africans brought to the Americas wereMuslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

, but most of these Africans were forced into Christianity during the era of American slavery. Islam had taken hold in Africa through Arab Muslim expansionism that began following Muhammad's death, and its presence solidified through trade, occupation, of the enduring 1300 year Middle Eastern slave trade of Africans that lasted well into until the 1900s. During the twentieth century, many African Americans who were seeking to reconnect with their African heritage converted to Islam, mainly through the influence of black nationalist

Black nationalism is a type of racial nationalism or pan-nationalism which espouses the belief that black people are a race, and which seeks to develop and maintain a black racial and national identity. Black nationalist activism revolves aro ...

groups with distinctive beliefs and practices. These included the Moorish Science Temple of America

The Moorish Science Temple of America is an American national and religious organization founded by Noble Drew Ali (born as Timothy Drew) in the early twentieth century. He based it on the premise that African Americans are descendants of the M ...

, and the largest organization, the Nation of Islam, founded in the 1930s, which had at least 20,000 members by 1963.,

Prominent members of the Nation of Islam included the human rights

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hu ...

activist Malcolm X

Malcolm X (born Malcolm Little, later Malik el-Shabazz; May 19, 1925 – February 21, 1965) was an American Muslim minister and human rights activist who was a prominent figure during the civil rights movement. A spokesman for the Nation of I ...

and the boxer Muhammad Ali. Malcolm X is considered the first person to have started the conversion of African Americans to mainstream Sunni Islam, after he left the Nation and made the pilgrimage

A pilgrimage is a journey, often into an unknown or foreign place, where a person goes in search of new or expanded meaning about their self, others, nature, or a higher good, through the experience. It can lead to a personal transformation, aft ...

to Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow ...

and changed his name to el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz. In 1975, Warith Deen Mohammed

Warith Deen Mohammed (born Wallace D. Muhammad; October 30, 1933 – September 9, 2008), also known as W. Deen Mohammed, Imam W. Deen Muhammad and Imam Warith Deen, was an African-American Muslim leader, theologian, philosopher, Muslim revi ...

, the son of Elijah Muhammad, took control of the Nation after his father's death and converted the majority of its members to orthodox Sunni Islam.

African-American Muslims constitute 20% of the total U.S. Muslim population. The majority of black Muslims are Sunni or orthodox Muslims. A 2014 Pew survey showed that 23% of American Muslims were converts to Islam, including 8% who converted to Islam from historically black Protestant traditions.

Other religions claim to be Islamic, including the Moorish Science Temple of America

The Moorish Science Temple of America is an American national and religious organization founded by Noble Drew Ali (born as Timothy Drew) in the early twentieth century. He based it on the premise that African Americans are descendants of the M ...

and offshoots of it, such as the Nation of Islam and the Five Percenters

5 is a number, numeral, and glyph.

5, five or number 5 may also refer to:

* AD 5, the fifth year of the AD era

* 5 BC, the fifth year before the AD era

Literature

* ''5'' (visual novel), a 2008 visual novel by Ram

* ''5'' (comics), an awa ...

.

Judaism

The American Jewish community includes Jews with African-American backgrounds. African-American Jews belong to each of the major American Jewish denominations—Orthodox

Orthodox, Orthodoxy, or Orthodoxism may refer to:

Religion

* Orthodoxy, adherence to accepted norms, more specifically adherence to creeds, especially within Christianity and Judaism, but also less commonly in non-Abrahamic religions like Neo-pa ...

, Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

, Reform

Reform ( lat, reformo) means the improvement or amendment of what is wrong, corrupt, unsatisfactory, etc. The use of the word in this way emerges in the late 18th century and is believed to originate from Christopher Wyvill's Association movement ...

—as well as minor religious movements within Judaism. Like Jews with other racial backgrounds, there are also African-American Jewish secularists and Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

who may rarely or never participate in religious practices. Estimates of the number of black Jews in the United States range from 20,000 to 200,000. Most black Jews have mixed ethnic backgrounds, or they are Jewish by either birth or conversion.

Black Hebrew Israelites

Black Hebrew Israelites (also called black Hebrews, African Hebrew Israelites, and Hebrew Israelites) are groups of African Americans who believe that they are the descendants of the ancientIsraelites

The Israelites (; , , ) were a group of Semitic-speaking tribes in the ancient Near East who, during the Iron Age, inhabited a part of Canaan.

The earliest recorded evidence of a people by the name of Israel appears in the Merneptah Stele o ...

. To varying degrees, Black Hebrews adhere to the religious beliefs and practices of both Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

and Judaism

Judaism ( he, ''Yahăḏūṯ'') is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in t ...

. They are not recognized as Jews by the greater Jewish community. Many of them choose to call themselves Hebrew Israelites or black Hebrews rather than Jews in order to indicate their claimed historic connections.

Others

There are African-Americans, mostly converts, who adhere to other faiths, namely theBaháʼí Faith

The Baháʼí Faith is a religion founded in the 19th century that teaches the essential worth of all religions and the unity of all people. Established by Baháʼu'lláh in the 19th century, it initially developed in Iran and parts of the ...

, Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religions, Indian religion or Indian philosophy#Buddhist philosophy, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha. ...

, Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Indian religion or '' dharma'', a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. As a religion, it is the world's third-largest, with over 1.2–1.35 billion followers, or 15–16% of the global p ...

, Jainism

Jainism ( ), also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religion. Jainism traces its spiritual ideas and history through the succession of twenty-four tirthankaras (supreme preachers of ''Dharma''), with the first in the current time cycle bein ...

, Scientology

Scientology is a set of beliefs and practices invented by American author L. Ron Hubbard, and an associated movement. It has been variously defined as a cult, a Scientology as a business, business, or a new religious movement. The most recent ...

, and Rastafari.

A 2019 report examined a sect of African-American women who venerated the African deity Oshun

Ọṣun, is an orisha, a spirit, a deity, or a goddess that reflects one of the manifestations of the Yorùbá Supreme Being in the Ifá oral tradition and Yoruba-based religions of West Africa. She is one of the most popular and venerated ...

in a form of Modern Paganism.

Some African Americans practice Louisiana Voodoo

Louisiana Voodoo (french: Vaudou louisianais, es, Vudú de Luisiana), also known as New Orleans Voodoo, is an African diasporic religion which originated in Louisiana, now in the southern United States. It arose through a process of syncreti ...

, especially African Americans in Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

. Louisiana Voodoo was brought to Louisiana by African slaves from Benin

Benin ( , ; french: Bénin , ff, Benen), officially the Republic of Benin (french: République du Bénin), and formerly Dahomey, is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Togo to the west, Nigeria to the east, Burkina Faso to the nort ...

during the French colonial era.

See also

* Black theology *National Black Catholic Congress

The National Black Catholic Congress (NBCC) is a Black Catholic advocacy group and quinquennial conference in the United States. It is a spiritual successor to Daniel Rudd's Colored Catholic Congress movement of the late 19th and early 20th centur ...

* Southern Christian Leadership Conference

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) is an African-American civil rights organization based in Atlanta, Georgia. SCLC is closely associated with its first president, Martin Luther King Jr., who had a large role in the American civ ...

* Louisiana black church fires

Three Louisiana black churches were set alight by a suspected arsonist between March 26 and April 4, 2019. The first fire occurred at St. Mary Baptist Church in Port Barre, Louisiana, Port Barre on March 26. Ten days later, two other historic b ...

* African diaspora religions

* Black church

The black church (sometimes termed Black Christianity or African American Christianity) is the faith and body of Christian congregations and denominations in the United States that minister predominantly to African Americans, as well as their ...

* Atheism in the African diaspora

* Islam in the African diaspora The practice of Islam by members of the African diaspora may be a consequence of African Muslims retaining their religion after leaving Africa (as for many Muslims in Europe) or of people of African ethnicity converting to Islam, as among many Afric ...

* African American–Jewish relations

African or Africans may refer to:

* Anything from or pertaining to the continent of Africa:

** People who are native to Africa, descendants of natives of Africa, or individuals who trace their ancestry to indigenous inhabitants of Africa

*** Ethn ...

* African-American Jews

* Black Mormons

Since Mormonism’s foundation, Black people have been members, however the church placed restrictions on proselytization efforts among black people. Before 1978, black membership was small. It has since grown, and in 1997, there were approximatel ...

* Black people and Mormonism

Over the past two centuries, the relationship between black people and Mormonism has included both official and unofficial discrimination.

From the mid-1800s to 1978, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) prevented mos ...

* Black Catholicism

Black Catholicism or African-American Catholicism comprises the African American people, beliefs, and practices in the Catholic Church.

There are currently around 3 million Black Catholics in the United States, making up 6% of the total popula ...

* T. D. Jakes

* Christian hip hop

* Black Gospel music

Black gospel music, often called gospel music or gospel, is a genre of African-American Christian music. It is rooted in the conversion of enslaved Africans to Christianity, both during and after the trans-atlantic slave trade, starting with wo ...

* Louisiana Voodoo

Louisiana Voodoo (french: Vaudou louisianais, es, Vudú de Luisiana), also known as New Orleans Voodoo, is an African diasporic religion which originated in Louisiana, now in the southern United States. It arose through a process of syncreti ...

History:

* Methodist Episcopal Church, South

* Wesleyanism

Wesleyan theology, otherwise known as Wesleyan–Arminian theology, or Methodist theology, is a theological tradition in Protestant Christianity based upon the ministry of the 18th-century evangelical reformer brothers John Wesley and Charles W ...

* Colored Episcopal Mission

*Racial segregation of churches in the United States

Racial segregation of churches in the United States is a pattern of Christian churches maintaining segregated congregations based on race. As of 2001, as many as 87% of Christian churches in the United States were completely made up of only white ...

* Religion in the United States

*History of religion in the United States

Religion in the United States began with the religions and spiritual practices of Native Americans. Later, religion also played a role in the founding of some colonies, as many colonists, such as the Puritans, came to escape religious persecutio ...

Notes

Further reading

Arnold, Bruce Makoto. "Shepherding a Flock of a Different Fleece: A Historical and Social Analysis of the Unique Attributes of the African American Pastoral Caregiver." The Journal of Pastoral Care and Counseling 66, no. 2 (June 2012).

* Brooks, Walter H. "The Evolution of the Negro Baptist Church." ''Journal of Negro History'' (1922) 7#1 pp. 11–22

in JSTOR

* Brunner, Edmund D. ''Church Life in the Rural South'' (1923) pp. 80–92, based on the survey in the early 1920s of 30 communities across the rural South * Calhoun-Brown, Allison. "The image of God: Black theology and racial empowerment in the African American community." ''Review of Religious Research'' (1999): 197–212

in JSTOR

* Chapman, Mark L. ''Christianity on trial: African-American religious thought before and after Black power'' (2006) * Collier-Thomas, Bettye. ''Jesus, jobs, and justice: African American women and religion'' (2010) * Curtis, Edward E. "African-American Islamization Reconsidered: Black history Narratives and Muslim identity." ''Journal of the American Academy of Religion'' (2005) 73#3 pp. 659–84. * Davis, Cyprian. ''The History of Black Catholics in the United States'' (1990). * Fallin Jr., Wilson. ''Uplifting the People: Three Centuries of Black Baptists in Alabama'' (2007) * Fitts, Leroy. ''A history of black Baptists'' (Broadman Press, 1985) * Frey, Sylvia R. and

Betty Wood

Betty C. Wood (23 February 1945 – 3 September 2021) was a British historian and academic, who specialised in early American history, Atlantic history, social history, and slavery in eighteenth and early nineteenth century. She was a Fellow of ...

. ''Come Shouting to Zion: African American Protestantism in the American South and British Caribbean to 1830'' (1998).

* Garrow, David. ''Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference'' (1986).

* Giggie, John Michael. ''After redemption: Jim Crow and the transformation of African American religion in the Delta, 1875–1915'' (2007)

* * Harper, Matthew. ''The End of Days: African American Religion and Politics in the Age of Emancipation'' (U of North Carolina Press, 2016) xii, 211 pp.

* Harris, Fredrick C. ''Something within: Religion in African-American political activism'' (1999)

* Higginbotham, Evelyn Brooks. ''Righteous Discontent: The Woman’s Movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880–1920'' (1993), highly influential study

* Jackson, Joseph H. ''A Story of Christian Activism: The History of the National Baptist Convention, USA. Inc'' (Nashville: Townsend Press, 1980); official history

* Johnson, Paul E., ed. ''African-American Christianity: Essays in History'' (1994).

* Mays, Benjamin E., and Joseph W. Nicholson. ''The Negro Church'' New York: Institute of Social and Religious Research (1933), sociological survey of rural and urban black churches in 1930

* Mays, Benjamin E. ''The Negro's God as reflected in his literature'' (1938), based on sermons

* Montgomery, William E. ''Under Their Own Vine and Fig Tree: The African-American Church in the South, 1865–1900'' (1993)

* Moody, Joycelyn. ''Sentimental Confessions: Spiritual Narratives of Nineteenth-century African American Women'' (2001)

* Owens, A. Nevell. ''Formation of the African Methodist Episcopal Church in the Nineteenth Century: Rhetoric of Identification'' (2014)

* Paris, Peter J. ''The Social Teaching of the Black Churches'' (Fortress Press, 1985)

* Raboteau, Albert. ''Slave Religion: The "Invisible Institution" in the Antebellum South'' (1978)

* Raboteau, Albert. ''African American-Religion'' (1999) 145ponline

basic introduction * Raboteau, Albert J. ''Canaan land: A religious history of African Americans'' (2001). * Salvatore, Nick. ''Singing in a Strange Land: C. L. Franklin, the Black Church, and the Transformation of America'' (2005) on the politics of the National Baptist Convention * Sensbach, Jon F. ''Rebecca’s Revival: Creating Black Christianity in the Atlantic World'' (2005) * Smith, R. Drew, ed. ''Long March ahead: African American churches and public policy in post-civil rights America'' (2004). * Sobel, M. '' Trabelin’ On: The Slave Journey to an Afro-Baptist Faith'' (1979) * Southern, Eileen. ''The Music of Black Americans: A History'' (1997) * Spencer, Jon Michael. ''Black hymnody: a hymnological history of the African-American church'' (1992) * Wills, David W. and Richard Newman, eds. ''Black Apostles at Home and Abroad: Afro-Americans and the Christian Mission from the Revolution to Reconstruction'' (1982) *Woodson, Carter. ''The History of the Negro Church'' (1921

online free

comprehensive history by leading black scholar * Yong, Amos, and Estrelda Y. Alexander. ''Afro-Pentecostalism: Black Pentecostal and Charismatic Christianity in History and Culture'' (2012)

Historiography

* Evans, Curtis J. ''The Burden of Black Religion'' (2008); traces ideas about Black religion from the antebellum period to 1950 * Frey, Sylvia R. "The Visible Church: Historiography of African American Religion since Raboteau," ''Slavery & Abolition'' (2008) 29#1 pp. 83–110 * Fulop, Timothy Earl, and Albert J. Raboteau, eds. ''African-American religion: interpretive essays in history and culture'' (1997) * Vaughn, Steve. "Making Jesus black: the historiographical debate on the roots of African-American Christianity." ''Journal of Negro History'' (1997): 25–41in JSTOR

Primary sources

* DuBois, W. E. B. ''The Negro Church: Report of a Social Study Made under the Direction of Atlanta University'' (1903) tp://65.186.223.235/FreeAgent_Black/Documents%20103110/Misc/The%20Negro%20Church.docx online* Sernett, Milton C., ed. ''Afro-American Religious History: A Documentary Witness'' (Duke University Press, 1985; 2nd ed. 1999) * West, Cornel, andEddie S. Glaude

Eddie S. Glaude Jr. (born September 4, 1968) is an American academic. He is the James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor of African American Studies at Princeton University, where he is also the Chair of the Center for African Amer ...

, eds. ''African American religious thought: An anthology'' (2003).

{{DEFAULTSORT:Religion In Black America

Black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white ...

Black studies

African-American society

African Americans and religion

African-American Christianity

African-American culture