Reinhard Gehlen on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

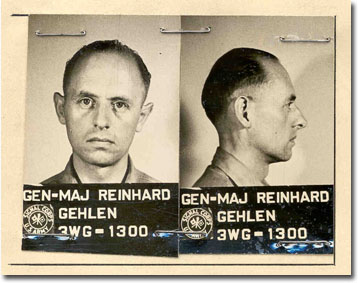

Reinhard Gehlen (3 April 1902 – 8 June 1979) was a

In spring of 1942, Gehlen assumed command of the Fremde Heere Ost (FHO) from Colonel Eberhard Kinzel. Before the Wehrmacht disasters in the

In spring of 1942, Gehlen assumed command of the Fremde Heere Ost (FHO) from Colonel Eberhard Kinzel. Before the Wehrmacht disasters in the

The FHO archives were unearthed and secretly taken to Camp King, ostensibly without the knowledge of the camp commander. By the end of summer 1945, Boker had the support of Brigadier General

The FHO archives were unearthed and secretly taken to Camp King, ostensibly without the knowledge of the camp commander. By the end of summer 1945, Boker had the support of Brigadier General

Between 1947 and 1955, agents of the Gehlen Organisation interviewed every German PoW who returned to West Germany from captivity in the Soviet Union. The network employed hundreds of former Wehrmacht and SS officers, and also had close contacts with the

Between 1947 and 1955, agents of the Gehlen Organisation interviewed every German PoW who returned to West Germany from captivity in the Soviet Union. The network employed hundreds of former Wehrmacht and SS officers, and also had close contacts with the

On 1 April 1956, 11 years after World War II had ended, the U.S. Government and the CIA formally transferred the Gehlen Organisation to the authority of what was by then the

On 1 April 1956, 11 years after World War II had ended, the U.S. Government and the CIA formally transferred the Gehlen Organisation to the authority of what was by then the

"The Secret Treaty of Fort Hunt."

''

"Disclosure" newsletter, Information promulgated by the U.S. National Archives & Records Administration

CIA declassified documents on the Gehlen Organization. * Reinhard Gehlen's CIA file on the

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

lieutenant-general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

and intelligence officer

An intelligence officer is a person employed by an organization to collect, compile or analyze information (known as intelligence) which is of use to that organization. The word of ''officer'' is a working title, not a rank, used in the same way ...

. He was chief of the Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the '' Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previo ...

Foreign Armies East Foreign Armies East, or Fremde Heere Ost (FHO), was a military intelligence organization of the ''Oberkommando des Heeres'' (OKH), the Supreme High Command of the German Army during World War II. It focused on analyzing the Soviet Union and other E ...

military intelligence

Military intelligence is a military discipline that uses information collection and analysis approaches to provide guidance and direction to assist commanders in their decisions. This aim is achieved by providing an assessment of data from a ...

service on the eastern front during World War II, spymaster

A spymaster is the person that leads a spy ring, or a secret service (such as an intelligence agency).

Historical spymasters

See also

*List of American spies

This is a list of spies who engaged in direct espionage. It includes Americans s ...

of the CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

-affiliated anticommunist Gehlen Organisation (1946–56) and the founding president of the Federal Intelligence Service (''Bundesnachrichtendienst'', BND) of West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 ...

(1956–68) during the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

.

Gehlen became a professional soldier in 1920 during the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a Constitutional republic, constitutional federal republic for the first time in ...

. In 1942, he became chief of Foreign Armies East Foreign Armies East, or Fremde Heere Ost (FHO), was a military intelligence organization of the ''Oberkommando des Heeres'' (OKH), the Supreme High Command of the German Army during World War II. It focused on analyzing the Soviet Union and other E ...

(FHO), the German Army's military intelligence

Military intelligence is a military discipline that uses information collection and analysis approaches to provide guidance and direction to assist commanders in their decisions. This aim is achieved by providing an assessment of data from a ...

unit on the Eastern Front (1941–45). He achieved the rank of major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

before he was fired by Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

in April 1945 because of the FHO's "defeatism", the pessimistic intelligence reports about Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

superiority.

In late 1945, following the 7 May surrender of Germany and the start of the Cold War, the U.S. military (G-2 Intelligence) recruited him to establish the Gehlen Organisation, an espionage network focusing on the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

. The organisation would employ former military officers of the Wehrmacht as well as former intelligence officers of the ''Schutzstaffel

The ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS; also stylized as ''ᛋᛋ'' with Armanen runes; ; "Protection Squadron") was a major paramilitary organization under Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany, and later throughout German-occupied Europe ...

'' (SS) and the ''Sicherheitsdienst

' (, ''Security Service''), full title ' (Security Service of the '' Reichsführer-SS''), or SD, was the intelligence agency of the SS and the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany. Established in 1931, the SD was the first Nazi intelligence organization ...

'' (SD). As head of the Gehlen Organization he sought cooperation with the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

(CIA), formed in 1947, resulting in the Gehlen Organization ultimately becoming closely affiliated with the CIA.

Gehlen was instrumental in negotiations to establish an official West German intelligence service based on the Gehlen Organisation of the early 1950s. In 1956, the Gehlen Organisation was transferred to the West German government and formed the core of the Federal Intelligence Service, the Federal Republic of Germany's official foreign intelligence service, with Gehlen serving as its first president until his retirement in 1968. While this was a civilian office, he was also a lieutenant-general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

in the Reserve forces of the Bundeswehr

The ''Bundeswehr'' (, meaning literally: ''Federal Defence'') is the armed forces of the Federal Republic of Germany. The ''Bundeswehr'' is divided into a military part (armed forces or ''Streitkräfte'') and a civil part, the military part con ...

, the highest-ranking reserve-officer in the military of West Germany. He received the Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

The Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany (german: Verdienstorden der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, or , BVO) is the only federal decoration of Germany. It is awarded for special achievements in political, economic, cultural, intellect ...

in 1968.

Early life

Gehlen was born 1902 into a Catholic family inErfurt

Erfurt () is the capital and largest city in the Central German state of Thuringia. It is located in the wide valley of the Gera river (progression: ), in the southern part of the Thuringian Basin, north of the Thuringian Forest. It sits in ...

. He had two brothers and a sister. He grew up in Breslau where his father, a former army officer became book publisher for the Ferdinand-Hirt-Verlag, a publishing house specializing in school books.

In 1920, Gehlen made Abitur

''Abitur'' (), often shortened colloquially to ''Abi'', is a qualification granted at the end of secondary education in Germany. It is conferred on students who pass their final exams at the end of ISCED 3, usually after twelve or thirteen ye ...

and joined the Reichswehr

''Reichswehr'' () was the official name of the German armed forces during the Weimar Republic and the first years of the Third Reich. After Germany was defeated in World War I, the Imperial German Army () was dissolved in order to be reshape ...

.

Career

After graduating from the German Staff College in 1935, Gehlen was promoted tocaptain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

and assigned to the German General Staff

The German General Staff, originally the Prussian General Staff and officially the Great General Staff (german: Großer Generalstab), was a full-time body at the head of the Prussian Army and later, the German Army, responsible for the continuou ...

.

Gehlen served on the General Staff until 1936 and was promoted to major in 1939; at the time of the German attack on Poland (1 September 1939), he was a staff officer in an infantry division. In 1940, he became liaison officer to Field Marshal Walther von Brauchitsch

Walther Heinrich Alfred Hermann von Brauchitsch (4 October 1881 – 18 October 1948) was a German field marshal and the Commander-in-Chief (''Oberbefehlshaber'') of the German Army during World War II. Born into an aristocratic military family, ...

, Army Commander-in-Chief; and later was transferred to the staff of General Franz Halder

Franz Halder (30 June 1884 – 2 April 1972) was a German general and the chief of staff of the Army High Command (OKH) in Nazi Germany from 1938 until September 1942. During World War II, he directed the planning and implementation of Operati ...

, the Chief of the German General Staff. In July 1941, he received a promotion to lieutenant-colonel and was sent to the Eastern Front, where he was assigned as senior intelligence-officer to the '' Fremde Heere Ost'' (FHO) section of the Staff.

Head of FHO

Battle of Stalingrad

The Battle of Stalingrad (23 August 19422 February 1943) was a major battle on the Eastern Front of World War II where Nazi Germany and its allies unsuccessfully fought the Soviet Union for control of the city of Stalingrad (later r ...

(23 August 1942 – 2 February 1943), a year into the German war against the Soviet Union, Gehlen understood that the FHO required fundamental re-organisation, and secured a staff of army linguists and geographers, anthropologists, lawyers, and junior military officers who would improve the FHO as a military-intelligence organisation despite the Nazi ideology of Slavic inferiority.

Hitler assassination plot, 1944

In summer 1944, ColonelHenning von Tresckow

Henning Hermann Karl Robert von Tresckow (; 10 January 1901 – 21 July 1944) was a German military officer with the rank of major general in the German Army who helped organize German resistance against Adolf Hitler. He attempted to assassina ...

, Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg

Colonel Claus Philipp Maria Justinian Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg (; 15 November 1907 – 21 July 1944) was a German army officer best known for his failed attempt on 20 July 1944 to assassinate Adolf Hitler at the Wolf's Lair.

Despite ...

, and General Adolf Heusinger

Adolf Bruno Heinrich Ernst Heusinger (4 August 1897 – 30 November 1982) was a German military officer whose career spanned the German Empire, the Weimar Republic, Nazi Germany and West Germany. He joined the German Army as a volunteer in 1915 ...

asked Gehlen to participate in their plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler. As head of the FHO, Gehlen allowed the military conspirators to make their plans under his protection, and he was present at their meetings at Berchtesgaden

Berchtesgaden () is a municipality in the district Berchtesgadener Land, Bavaria, in southeastern Germany, near the border with Austria, south of Salzburg and southeast of Munich. It lies in the Berchtesgaden Alps, south of Berchtesgaden; th ...

. However, after the bomb plot failed on 20 July

Events Pre-1600

* 70 – Siege of Jerusalem: Titus, son of emperor Vespasian, storms the Fortress of Antonia north of the Temple Mount. The Roman army is drawn into street fights with the Zealots.

* 792 – Kardam of Bulgaria defeat ...

, he escaped falling victim to Hitler's revenge.

Dismissal, 1945

Gehlen's cadre of FHO intelligence-officers produced accurate field-intelligence about the Red Army that frequently contradicted rear-echelon perceptions of the eastern battle front. Hitler dismissed the gathered information asdefeatism

Defeatism is the acceptance of defeat without struggle, often with negative connotations. It can be linked to pessimism in psychology, and may sometimes be used synonymously with fatalism or determinism.

History

The term ''defeatism'' is common ...

and philosophically harmful to the Nazi cause against " Judeo-Bolshevism" in Russia. In April 1945, despite the accuracy of the intelligence, Hitler dismissed Gehlen, soon after his promotion to major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

.

Preparation for Post-War

The FHO collection of both military and political intelligence from captured Red Army soldiers assured Gehlen's post–WWII survival as a Western anticommunist spymaster, with networks of spies and secret agents in the countries of Soviet-occupied Europe. During the German war against the Soviet Union in 1941 to 1945, Gehlen's FHO collected much tacticalmilitary intelligence

Military intelligence is a military discipline that uses information collection and analysis approaches to provide guidance and direction to assist commanders in their decisions. This aim is achieved by providing an assessment of data from a ...

about the Red Army, and much strategic political intelligence about the Soviet Union. Understanding that the Soviet Union would defeat and occupy the Third Reich

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, Gehlen ordered the FHO intelligence files copied to microfilm

Microforms are scaled-down reproductions of documents, typically either films or paper, made for the purposes of transmission, storage, reading, and printing. Microform images are commonly reduced to about 4% or of the original document size. ...

; the FHO files proper were stored in watertight drums and buried in various locations in the Austrian Alps.

They amounted to fifty cases of German intelligence about the Soviet Union, which were at Gehlen's disposal for sale to western intelligence services. Meanwhile, as of 1946, when the Soviets consolidated their hegemony and sphere of influence in Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe as agreed at the Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference (german: Potsdamer Konferenz) was held at Potsdam in the Soviet occupation zone from July 17 to August 2, 1945, to allow the three leading Allies to plan the postwar peace, while avoiding the mistakes of the Paris P ...

of 1945 and demarcated with what became known as the Iron Curtain

The Iron Curtain was the political boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1991. The term symbolizes the efforts by the Soviet Union (USSR) to block itself and its ...

, the Western Allies of World War II

The Allies, formally referred to as the Declaration by United Nations, United Nations from 1942, were an international Coalition#Military, military coalition formed during the World War II, Second World War (1939–1945) to oppose the Axis ...

, the U.S, Britain, France, had no sources of covert information within the countries in which the occupying Red Army had vanquished the Wehrmacht.

After Second World War

On 22 May 1945, Gehlen surrendered to theCounter Intelligence Corps

The Counter Intelligence Corps (Army CIC) was a World War II and early Cold War intelligence agency within the United States Army consisting of highly trained special agents. Its role was taken over by the U.S. Army Intelligence Corps in 1961 and ...

(CIC) of the U.S. Army in Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total l ...

and was taken to Camp King Camp King is a site on the outskirts of Oberursel, Taunus (in Germany), with a long history. It began as a school for agriculture under the auspices of the University of Frankfurt. During World War II, the lower fields became an interrogation cent ...

, near Oberursel

Oberursel (Taunus) () is a town in Germany and part of the Frankfurt Rhein-Main urban area. It is located to the north west of Frankfurt, in the Hochtaunuskreis county. It is the 13th largest town in Hesse. In 2011, the town hosted the 51st He ...

, and interrogated by Captain John R. Boker. The American Army recognised his potential value as a spymaster with great knowledge of Soviet forces and anticommunist intelligence contacts in the Soviet Union. In exchange for his liberty and the liberty of his command (prisoners of the US Army), Gehlen offered the Counter Intelligence Corps access to the FHO's intelligence archives and to his anticommunist espionage network in the Soviet Union, known later as the Gehlen Organization. Boker removed his name and those of his Wehrmacht command from the official lists of German prisoners of war, and transferred seven FHO senior officers to join Gehlen.

The FHO archives were unearthed and secretly taken to Camp King, ostensibly without the knowledge of the camp commander. By the end of summer 1945, Boker had the support of Brigadier General

The FHO archives were unearthed and secretly taken to Camp King, ostensibly without the knowledge of the camp commander. By the end of summer 1945, Boker had the support of Brigadier General Edwin Sibert

Edwin Luther Sibert Order of the British Empire, CBE (March 2, 1897 – December 16, 1977) was a United States Army officer with the rank of Major general (United States), major general and served as intelligence officer during World War II and p ...

, the G2 (senior intelligence officer) of the U.S. Twelfth Army Group,Simpson, pp. 41–42. who arranged the secret transport of Gehlen, his officers and the FHO intelligence archives, authorized by his superiors in the chain of command, General Walter Bedell Smith

General Walter Bedell "Beetle" Smith (5 October 1895 – 9 August 1961) was a senior officer of the United States Army who served as General Dwight D. Eisenhower's chief of staff at Allied Forces Headquarters (AFHQ) during the Tunisia Campai ...

(chief of staff for General Eisenhower), who worked with William Donovan William or Bill(y) Donovan may refer to:

Sports

*Bill Donovan (1876–1923), pitcher and manager in Major League Baseball

*Bill Donovan (Boston Braves pitcher) (1916–1997), pitcher in Major League Baseball

*Billy Donovan

William John Donovan ...

(former OSS chief) and Allen Dulles

Allen Welsh Dulles (, ; April 7, 1893 – January 29, 1969) was the first civilian Director of Central Intelligence (DCI), and its longest-serving director to date. As head of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) during the early Cold War, he ov ...

(OSS chief), who also was the OSS station-chief in Bern

german: Berner(in)french: Bernois(e) it, bernese

, neighboring_municipalities = Bremgarten bei Bern, Frauenkappelen, Ittigen, Kirchlindach, Köniz, Mühleberg, Muri bei Bern, Neuenegg, Ostermundigen, Wohlen bei Bern, Zollikofen

, website ...

. On 20 September 1945, Gehlen and three associates were flown from the American Zone of Occupation

Germany was already de facto occupied by the Allies from the real fall of Nazi Germany in World War II on 8 May 1945 to the establishment of the East Germany on 7 October 1949. The Allies (United States, United Kingdom, Soviet Union, and F ...

in Germany to the US, to become spies for the US government.

In July 1946, the US officially released Gehlen and returned him to occupied Germany. On 6 December 1946, he began espionage operations against the Soviet Union, by establishing what was known to US intelligence as the Gehlen Organisation or "the Org", a secret intelligence service composed of former intelligence officers of the Wehrmacht and members of the SS and the SD, which was headquartered first at Oberursel

Oberursel (Taunus) () is a town in Germany and part of the Frankfurt Rhein-Main urban area. It is located to the north west of Frankfurt, in the Hochtaunuskreis county. It is the 13th largest town in Hesse. In 2011, the town hosted the 51st He ...

, near Frankfurt, then at Pullach

Pullach, officially Pullach i. Isartal, is a municipality in the district of Munich in Bavaria in Germany. It lies on the Isar Valley Railway and is served by the S 7 line of the Munich S-Bahn, at the Großhesselohe Isartalbahnhof, Pullach ...

, near Munich. The organisation's cover-name was the South German Industrial Development Organization. Gehlen initially selected 350 ex-intelligence officers of the Wehrmacht as staff; eventually, the organisation comprised some 4,000 anticommunist secret agents.

Gehlen Organisation, 1947–56

After he started working for the U.S. Government, Gehlen was subordinate to US Army G-2 (Intelligence). He resented this arrangement and in 1947, the year after his Organisation was established, Gehlen arranged for a transfer and became subordinate to theCentral Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

(CIA). The agency kept close control of the Gehlen Organisation, because for many years during the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

of 1945–91, its agents were the CIA's only assets in the countries of the Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

.

Between 1947 and 1955, agents of the Gehlen Organisation interviewed every German PoW who returned to West Germany from captivity in the Soviet Union. The network employed hundreds of former Wehrmacht and SS officers, and also had close contacts with the

Between 1947 and 1955, agents of the Gehlen Organisation interviewed every German PoW who returned to West Germany from captivity in the Soviet Union. The network employed hundreds of former Wehrmacht and SS officers, and also had close contacts with the anti-Communist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when the United States and the ...

organisations of the East European émigré communities in Western Europe. They observed the operations of the railroad systems, airfields, and ports of the USSR, and their secret agents infiltrated the Baltic Soviet Republics and the Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic ( uk, Украї́нська Радя́нська Соціалісти́чна Респу́бліка, ; russian: Украи́нская Сове́тская Социалисти́ческая Респ ...

. Among their successes was Operation Bohemia, a major effort of anti-communist counter-espionage.

The security and efficacy of the Gehlen Organisation were compromised by East German moles within it, such as Johannes Clemens, Erwin Tiebel and Heinz Felfe

Heinz Paul Johann Felfe (March 18, 1918 – May 8, 2008) was a German spy.

At various times he worked for the intelligence services of Nazi Germany, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and West Germany. It is still not clear when he started ...

who were feeding information to the Soviets while in the Org and later, while in the BND that was headed by Gehlen. All three were eventually discovered and convicted in 1963.

There were also Communists and their sympathizers within the CIA and the SIS ( MI6), especially Kim Philby

Harold Adrian Russell "Kim" Philby (1 January 191211 May 1988) was a British intelligence officer and a double agent for the Soviet Union. In 1963 he was revealed to be a member of the Cambridge Five, a spy ring which had divulged British s ...

, himself a Soviet secret agent. As such information appeared, Gehlen, personally, and the Gehlen Organisation, officially, were attacked by the governments of the Western powers. The British government was especially hostile towards Gehlen, and the politically liberal British press ensured full publication of the existence of the Gehlen Organisation, which compromised the operation.

Federal Intelligence Service (BND), 1956–1968

On 1 April 1956, 11 years after World War II had ended, the U.S. Government and the CIA formally transferred the Gehlen Organisation to the authority of what was by then the

On 1 April 1956, 11 years after World War II had ended, the U.S. Government and the CIA formally transferred the Gehlen Organisation to the authority of what was by then the Federal Republic of Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated between ...

, under Chancellor Konrad Adenauer

Konrad Hermann Joseph Adenauer (; 5 January 1876 – 19 April 1967) was a German statesman who served as the first chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany from 1949 to 1963. From 1946 to 1966, he was the first leader of the Christian Dem ...

(1949–63). By way of that transfer of geopolitical sponsorship, the anti–Communist Gehlen Organisation became the nucleus of the Bundesnachrichtendienst

The Federal Intelligence Service (German: ; , BND) is the foreign intelligence agency of Germany, directly subordinate to the Chancellor's Office. The BND headquarters is located in central Berlin and is the world's largest intelligence h ...

(BND, Federal Intelligence Service).

Gehlen became president of the BND as an espionage service, until he was forced out of office in 1968. The end of Gehlen's career as a spymaster resulted from a confluence of events in West Germany: the exposure of a KGB mole, Heinz Felfe

Heinz Paul Johann Felfe (March 18, 1918 – May 8, 2008) was a German spy.

At various times he worked for the intelligence services of Nazi Germany, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and West Germany. It is still not clear when he started ...

, (a former SS lieutenant) working at BND headquarters; political estrangement from Adenauer, in 1963, which aggravated his professional problems; and the inefficiency of the BND consequent to Gehlen's poor leadership and continual inattention to the business of counter-espionage

Counterintelligence is an activity aimed at protecting an agency's intelligence program from an opposition's intelligence service. It includes gathering information and conducting activities to prevent espionage, sabotage, assassinations or ot ...

as national defence.

Gehlen's refusal to correct reports with questionable content strained the organization's credibility, and dazzling achievements became an infrequent commodity. A veteran agent remarked at the time that the BND pond then contained some sardines, though a few years earlier the pond had been alive with sharks.

The fact that the BND could score certain successes despite East German Stasi

The Ministry for State Security, commonly known as the (),An abbreviation of . was the state security service of the East Germany from 1950 to 1990.

The Stasi's function was similar to the KGB, serving as a means of maintaining state autho ...

interference, internal malpractice, inefficiencies and infighting, was primarily due to select members of the staff who took it upon themselves to step up and overcome then existing maladies. Abdication of responsibility by Reinhard Gehlen was the malignancy; bureaucracy

The term bureaucracy () refers to a body of non-elected governing officials as well as to an administrative policy-making group. Historically, a bureaucracy was a government administration managed by departments staffed with non-elected offi ...

and cronyism

Cronyism is the spoils system practice of Impartiality, partiality in awarding jobs and other advantages to friends or trusted colleagues, especially in politics and between politicians and supportive organizations. For example, cronyism occurs ...

remained pervasive, even nepotism

Nepotism is an advantage, privilege, or position that is granted to relatives and friends in an occupation or field. These fields may include but are not limited to, business, politics, academia, entertainment, sports, fitness, religion, an ...

(at one time Gehlen had 16 members of his extended family on the BND payroll).Höhne & Zolling, p. 245 Only slowly did the younger generation then advance to substitute new ideas for some of the bad habits caused mainly by Gehlen's semi-retired attitude and frequent holiday absences.

Gehlen was forced out of the BND due to "political scandal within the ranks", according to one source, He retired in 1968 as a civil servant of West Germany, classified as a ''Ministerialdirektor'', a senior grade with a generous pension. His successor, Bundeswehr

The ''Bundeswehr'' (, meaning literally: ''Federal Defence'') is the armed forces of the Federal Republic of Germany. The ''Bundeswehr'' is divided into a military part (armed forces or ''Streitkräfte'') and a civil part, the military part con ...

Brigadier General Gerhard Wessel, immediately called for a program of modernization and streamlining.

Honours

*Iron Cross

The Iron Cross (german: link=no, Eisernes Kreuz, , abbreviated EK) was a military decoration in the Kingdom of Prussia, and later in the German Empire (1871–1918) and Nazi Germany (1933–1945). King Frederick William III of Prussia es ...

second class

*War Merit Cross

The War Merit Cross (german: Kriegsverdienstkreuz) was a state decoration of Nazi Germany during World War II. By the end of the conflict it was issued in four degrees and had an equivalent civil award. A " de-Nazified" version of the War Meri ...

second and first class with swords

*German Cross

The War Order of the German Cross (german: Der Kriegsorden Deutsches Kreuz), normally abbreviated to the German Cross or ''Deutsches Kreuz'', was instituted by Adolf Hitler on 28 September 1941. It was awarded in two divisions: in gold for repe ...

in silver (1945)

*Grand Cross of the Order pro Merito Melitensi of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta

The Sovereign Military Order of Malta (SMOM), officially the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, of Rhodes and of Malta ( it, Sovrano Militare Ordine Ospedaliero di San Giovanni di Gerusalemme, di Rodi e di Malta; ...

(1948)

*Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

The Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany (german: Verdienstorden der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, or , BVO) is the only federal decoration of Germany. It is awarded for special achievements in political, economic, cultural, intellect ...

(1968)

*Good Conduct Medal (United States)

The Good Conduct Medal is one of the oldest military awards of the United States Armed Forces. The U.S. Navy's variant of the Good Conduct Medal was established in 1869, the Marine Corps version in 1896, the Coast Guard version in 1923, the Arm ...

Criticism

Several publications have criticized the fact that Gehlen allowed former Nazis to work for the agencies. The authors of the book ''A Nazi Past: Recasting German Identity in Postwar Europe'' stated that Reinhard Gehlen simply did not want to know the backgrounds of the men whom the BND hired in the 1950s. The American National Security Archive states that "he employed numerous former Nazis and known war criminals". An article in ''The Independent

''The Independent'' is a British online newspaper. It was established in 1986 as a national morning printed paper. Nicknamed the ''Indy'', it began as a broadsheet and changed to tabloid format in 2003. The last printed edition was publish ...

'' on 29 June 2018 made this statement about BND employees: "Operating until 1956, when it was superseded by the BND, the Gehlen Organisation was allowed to employ at least 100 former Gestapo or SS officers.... Among them were Adolf Eichmann’s deputyOn the other hand, Gehlen himself was cleared by the CIA'sAlois Brunner Alois Brunner (8 April 1912 – December 2001) was an Austrian (SS) SS-Hauptsturmführer who played a significant role in the implementation of the Holocaust through rounding up and deporting Jews in occupied Austria, Greece, Macedonia, France, ..., who would go on to die of old age despite having sent more than 100,000 Jews to ghettos or internment camps, and ex-SS major Emil Augsburg.... Many ex-Nazi functionaries including Silberbauer, the captor of Anne Frank, transferred over from the Gehlen Organisation to the BND.... Instead of expelling them, the BND even seems to have been willing to recruit more of them – at least for a few years".

James H. Critchfield

James Hardesty Critchfield (January 30, 1917 – April 22, 2003) was an officer of the US Central Intelligence Agency who rose to become the chief of its Near East and South Asia division. He also served as the CIA's national intelligence offic ...

, who worked with the Gehlen Organization from 1949 to 1956. In 2001, he said that "almost everything negative that has been written about Gehlen, s an

S, or s, is the nineteenth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''ess'' (pronounced ), plural ''esses''.

Histor ...

ardent ex-Nazi, one of Hitler's war criminals ... is all far from the fact," as quoted in the ''Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large na ...

''. Critchfield added that Gehlen hired the former Sicherheitsdienst

' (, ''Security Service''), full title ' (Security Service of the '' Reichsführer-SS''), or SD, was the intelligence agency of the SS and the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany. Established in 1931, the SD was the first Nazi intelligence organization ...

(Security Service of the Reichsführer-SS) men "reluctantly, under pressure from German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer

Konrad Hermann Joseph Adenauer (; 5 January 1876 – 19 April 1967) was a German statesman who served as the first chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany from 1949 to 1963. From 1946 to 1966, he was the first leader of the Christian Dem ...

to deal with 'the avalanche of subversion hitting them from East Germany'".

Legacy

Gehlen's memoirs were published in 1977 by World Publishers, New York. In the same year another book was published about him, ''The General Was a Spy,'' by Heinz Hoehne and Herman Zolling, Coward, McCann and Geoghegan, New York, A review of the latter, published by the CIA in 1996, calls it a "poor book" and goes on to allege that "so much of it is sheer garbage" because of many errors. The CIA review also discusses another book, ''Gehlen, Spy of the Century'', by E. H. Cookridge, Hodder and Stoughton,London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, 1971, and claims that it is "chock full of errors". The CIA review is kinder when speaking of Gehlen's memoirs but makes this comment: "Gehlen's descriptions of most of his so-called successes in the political intelligence field are, in my opinion, either wishful thinking or self-delusion.... Gehlen was never a good clandestine operator, nor was he a particularly good administrator. And therein lay his failures. The Gehlen Organization/BND always had a good record in the collection of military and economic intelligence on East Germany and the Soviet forces there. But this information, for the most part, came from observation and not from clandestine penetration".Upon Gehlen's retirement in 1968, a CIA note on Gehlen describes him as "essentially a military officer in habits and attitudes". He was also characterized as "essentially a conservative", who refrained from entertaining and drinking, was fluent in English, and was at ease among senior American officials.

References

Bibliography and sources

* Cookridge, E. H. (1971). ''Gehlen: Spy of the Century''. London:Hodder & Stoughton

Hodder & Stoughton is a British publishing house, now an imprint of Hachette.

History

Early history

The firm has its origins in the 1840s, with Matthew Hodder's employment, aged 14, with Messrs Jackson and Walford, the official publishe ...

; New York: Random House

Random House is an American book publisher and the largest general-interest paperback publisher in the world. The company has several independently managed subsidiaries around the world. It is part of Penguin Random House, which is owned by Germ ...

(1972).

* Critchfield, James H. (2003). ''Partners at Creation: The Men Behind Postwar Germany's Defense and Intelligence Establishments''. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press

The United States Naval Institute (USNI) is a private non-profit military association that offers independent, nonpartisan forums for debate of national security issues. In addition to publishing magazines and books, the Naval Institute holds se ...

. .

*

* Hersh, Burton (1992). ''The Old Boys: The American Elite and the Origins of the CIA''. New York: Scribner's

Charles Scribner's Sons, or simply Scribner's or Scribner, is an American publisher based in New York City, known for publishing American authors including Henry James, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Kurt Vonnegut, Marjorie Kinnan Ra ...

.

*

* Kross, Peter. "Intelligence" in ''Military Heritage'', October 2004, pp. 26–30

* Oglesby, Carl (Fall 1990)"The Secret Treaty of Fort Hunt."

''

CovertAction Information Bulletin

''CovertAction Quarterly'' (formerly ''CovertAction Information Bulletin'') was an American journal in publication from 1978 to 2005, focused primarily on watching and reporting global covert operations. It is generally critical of US Foreign Poli ...

''.

* Reese, Mary Ellen. ''General Reinhard Gehlen: The CIA Connection''. Fairfax, Vir.: George Mason University

George Mason University (George Mason, Mason, or GMU) is a public research university in Fairfax County, Virginia with an independent City of Fairfax, Virginia postal address in the Washington, D.C. Metropolitan Area. The university was origin ...

. 1990

* United States National Archives, Washington, D.C. NARA Collection of Foreign Records Seized, Microfilm T-77, T-78

* Weiner, Tim (2008). '' Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA''. Anchor Books

Vintage Books is a trade paperback publishing imprint of Penguin Random House originally established by Alfred A. Knopf in 1954. The company was purchased by Random House in April 1960, and a British division was set up in 1990. After Random Hou ...

, pp. 10–190. .

Literature

* John Douglas-Gray in his thriller ''The Novak Legacy'' * WEB Griffin, in his post-World War II novel ''Top Secret'' * Charles Whiting, ''Germany's Master Spy'' (1972)External links

"Disclosure" newsletter, Information promulgated by the U.S. National Archives & Records Administration

CIA declassified documents on the Gehlen Organization. * Reinhard Gehlen's CIA file on the

Internet Archive

The Internet Archive is an American digital library with the stated mission of "universal access to all knowledge". It provides free public access to collections of digitized materials, including websites, software applications/games, music, ...

.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Gehlen, Reinhard

1902 births

1979 deaths

German anti-communists

German Roman Catholics

Grand Crosses with Star and Sash of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

Lieutenant generals of the German Army

Major generals of the German Army (Wehrmacht)

Members of the 20 July plot

Military personnel from Erfurt

People from the Province of Saxony

People of the Federal Intelligence Service

Recipients of the Iron Cross (1939), 2nd class

Recipients of the War Merit Cross

Spies for the Federal Republic of Germany

World War II spies for Germany