Reform War on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Reform War, or War of Reform ( es, Guerra de Reforma), also known as the Three Years' War ( es, Guerra de los Tres Años), was a

Juan Alvarez assumed power in November, 1855. His cabinet was radical and included the prominent liberals

Juan Alvarez assumed power in November, 1855. His cabinet was radical and included the prominent liberals

President Juárez and his ministers fled from Mexico City to

President Juárez and his ministers fled from Mexico City to

President Miramón's most important military priority was now the capture of Veracruz, the liberals' stronghold. He left the capital on February 16, leading the troops in person along with his minister of war.

President Miramón's most important military priority was now the capture of Veracruz, the liberals' stronghold. He left the capital on February 16, leading the troops in person along with his minister of war.

Miramón was preparing another siege of Veracruz, leaving the conservative capital of Mexico City on February 8, leading his troops in person along with his war minister, hoping to rendezvous with a small naval squadron led by the Mexican General Marin who was disembarking from Havana. The United States Navy however had orders to intercept it. Miramón arrived at

Miramón was preparing another siege of Veracruz, leaving the conservative capital of Mexico City on February 8, leading his troops in person along with his war minister, hoping to rendezvous with a small naval squadron led by the Mexican General Marin who was disembarking from Havana. The United States Navy however had orders to intercept it. Miramón arrived at

civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

in Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

lasting from January 11, 1858 to January 11, 1861, fought between liberals and conservatives, over the promulgation of Constitution of 1857

The Federal Constitution of the United Mexican States of 1857 ( es, Constitución Federal de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos de 1857), often called simply the Constitution of 1857, was the liberal constitution promulgated in 1857 by Constituent Co ...

, which had been drafted and published under the presidency of Ignacio Comonfort

Ignacio Gregorio Comonfort de los Ríos (; 12 March 1812 – 13 November 1863), known as Ignacio Comonfort, was a Mexican politician and soldier who was also president during one of the most eventful periods in 19th century Mexican history: La ...

. The constitution had codified a liberal program intended to limit the political, economic, and cultural power of the Catholic Church; separate church and state; reduce the power of the Mexican Army

The Mexican Army ( es, Ejército Mexicano) is the combined land and air branch and is the largest part of the Mexican Armed Forces; it is also known as the National Defense Army.

The Army is under the authority of the Secretariat of National ...

by elimination of the ''fuero

(), (), () or () is a Spanish legal term and concept. The word comes from Latin , an open space used as a market, tribunal and meeting place. The same Latin root is the origin of the French terms and , and the Portuguese terms and ; all ...

''; strengthen the secular state through public education; and economically develop the nation.

The constitution had been promulgated on February 5, 1857 with the intention of coming into power on September 16, only to be confronted with extreme opposition from Conservatives and the Catholic Church over its anti-clerical

Anti-clericalism is opposition to religious authority, typically in social or political matters. Historical anti-clericalism has mainly been opposed to the influence of Roman Catholicism. Anti-clericalism is related to secularism, which seeks to ...

provisions, most notably the Lerdo law

The Lerdo Law ( Spanish: ''Ley Lerdo'') was the common name for the Reform law that was formally known as the Confiscation of Law and Urban Ruins of the Civil and Religious Corporations of Mexico. It targeted not only property owned by the Catho ...

, which forced the sale of most of the Church's rural properties. The measure was not exclusively aimed at the Catholic Church, but also Mexico's indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

, which were forced to sell sizeable portions of their communal lands. Controversy was further inflamed when the Catholic Church decreed excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

to civil servants who took a government mandated oath upholding the new constitution, which left Catholic civil servants with the choice of keeping their jobs or being excommunicated.

As opposition to the constitution escalated, President Comonfort, a known moderate, joined conservative Félix Zuloaga

Felix may refer to:

* Felix (name), people and fictional characters with the name

Places

* Arabia Felix is the ancient Latin name of Yemen

* Felix, Spain, a municipality of the province Almería, in the autonomous community of Andalusia, ...

's Plan of Tacubaya

The Plan of Tacubaya ( es, Plan de Tacubaya), sometimes called the Plan of Zuloaga, was issued by conservative Mexican General Félix Zuloaga on 17 December 1857 in Tacubaya against the liberal Constitution of 1857. The plan nullified the Const ...

which amounted to a self-coup

A self-coup, also called autocoup (from the es, autogolpe), is a form of coup d'état in which a nation's head, having come to power through legal means, tries to stay in power through illegal means. The leader may dissolve or render powerless ...

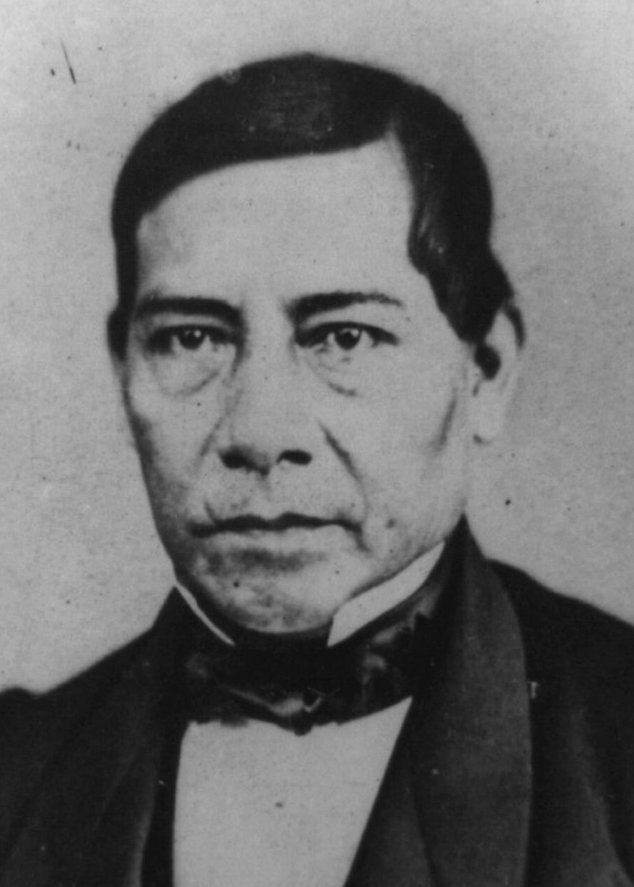

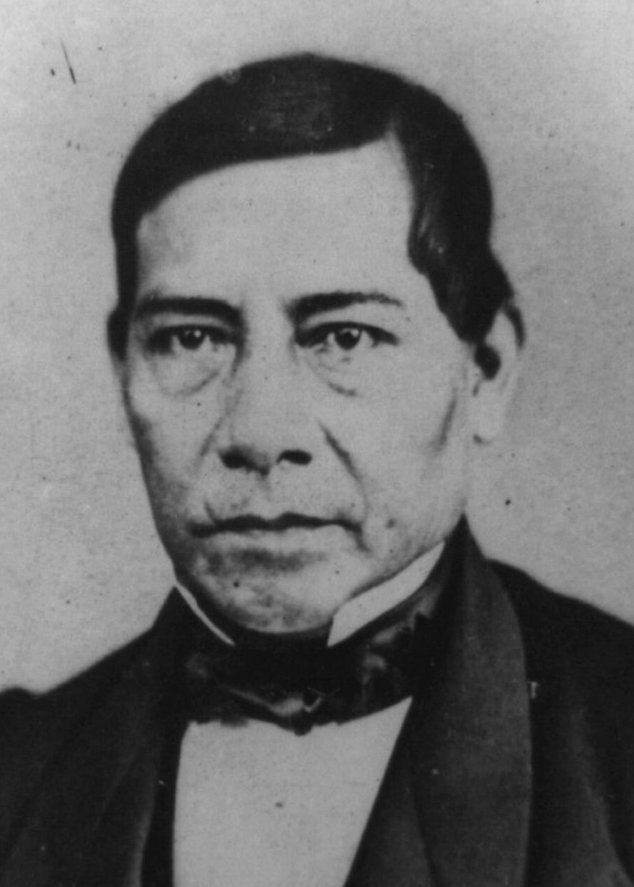

on December 17, 1857. The Constitutional Congress was closed, the constitution was nullified, and Comonfort gained emergency powers as President. Comonfort, hoping to establish a more moderate government however, found himself triggering a civil war. On January 11, 1858, Comonfort resigned and was constitutionally succeeded by president of the Supreme Court, Benito Juárez

Benito Pablo Juárez García (; 21 March 1806 – 18 July 1872) was a Mexican liberal politician and lawyer who served as the 26th president of Mexico from 1858 until his death in office in 1872. As a Zapotec, he was the first indigenous pre ...

. Mexican states subsequently chose to side with either the Mexico City based government of Zuloaga or that of Juárez which established itself at the strategic port of Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

. The first year of the war was marked by repeated conservative victories, but the liberals remained entrenched in the nation's coastal regions, including their capital at Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

giving them access to vital customs revenue.

Both governments attained international recognition, the Liberals by the United States, and the Conservatives by France, Great Britain, and Spain. Liberals negotiated the McLane–Ocampo Treaty with the United States in 1859. If ratified the treaty would have given the liberal regime cash but also would have granted the United States perpetual military and economic rights on Mexican territory. The treaty failed to pass in the U.S. Senate, but the U.S. Navy nonetheless helped protect Juárez's government in Veracruz.

Liberals thereafter accumulated victories on the battlefield until Conservative forces surrendered on December 22, 1860. Juárez returned to Mexico City on January 11, 1861 and held presidential elections in March. Although Conservative forces lost the war, guerrillas remained active in the countryside and would join the upcoming French intervention

This is a list of wars involving France and its predecessor states. It is an incomplete list of French and proto-French wars and battles from the foundation of Frankish Kingdom, Francia by Clovis I, the Merovingian dynasty, Merovingian king who uni ...

to help establish the Second Mexican Empire

The Second Mexican Empire (), officially the Mexican Empire (), was a constitutional monarchy established in Mexico by Mexican monarchists in conjunction with the Second French Empire. The period is sometimes referred to as the Second French i ...

.

Background

After achieving independence in 1821, Mexico would alternatively find itself governed by both liberal and conservative coalitions. The original Constitution of 1824 established the federalist system championed by the liberals, with Mexican states holding sovereign power and the central government being weak. The brief liberal administration of Valentín Gómez Farías attempted to implementanti-clerical

Anti-clericalism is opposition to religious authority, typically in social or political matters. Historical anti-clericalism has mainly been opposed to the influence of Roman Catholicism. Anti-clericalism is related to secularism, which seeks to ...

measures as early as 1833. The government closed church schools, assumed the right to make clerical appointments to the Catholic Church, and shut down monasteries. The ensuing backlash would result in Gómez Farías's government being overthrown and conservatives established a Centralist Republic in 1835 that lasted until the outbreak of the Mexican-American War

Mexican Americans ( es, mexicano-estadounidenses, , or ) are Americans of full or partial Mexican heritage. In 2019, Mexican Americans comprised 11.3% of the US population and 61.5% of all Hispanic and Latino Americans. In 2019, 71% of Mexica ...

in 1846.

In 1854 there was a liberal revolt, known as the Plan of Ayutla against the dictatorship of Santa Anna Santa Anna may refer to:

* Santa Anna, Texas, a town in Coleman County in Central Texas, United States

* Santa Anna, Starr County, Texas

* Santa Anna Township, DeWitt County, Illinois, one of townships in DeWitt County, Illinois, United States. ...

. A coalition of liberals, including Benito Juárez

Benito Pablo Juárez García (; 21 March 1806 – 18 July 1872) was a Mexican liberal politician and lawyer who served as the 26th president of Mexico from 1858 until his death in office in 1872. As a Zapotec, he was the first indigenous pre ...

, then governor of Oaxaca, and Melchor Ocampo

Melchor Ocampo (5 January 1814 – 3 June 1861) was a Mexican lawyer, scientist, and politician. A mestizo and a radical liberal, he was fiercely anticlerical, perhaps an atheist, and his early writings against the Catholic Church in Mexico ga ...

of Michoacán overthrew Santa Anna, and the presidency passed on to the liberal caudillo Juan Alvarez.

La Reforma

Juan Alvarez assumed power in November, 1855. His cabinet was radical and included the prominent liberals

Juan Alvarez assumed power in November, 1855. His cabinet was radical and included the prominent liberals Benito Juárez

Benito Pablo Juárez García (; 21 March 1806 – 18 July 1872) was a Mexican liberal politician and lawyer who served as the 26th president of Mexico from 1858 until his death in office in 1872. As a Zapotec, he was the first indigenous pre ...

, Miguel Lerdo de Tejada, Melchor Ocampo

Melchor Ocampo (5 January 1814 – 3 June 1861) was a Mexican lawyer, scientist, and politician. A mestizo and a radical liberal, he was fiercely anticlerical, perhaps an atheist, and his early writings against the Catholic Church in Mexico ga ...

, and Guillermo Prieto

Guillermo Prieto Pradillo (10 February 1818 – 2 March 1897) was a Mexican novelist, short-story writer, poet, chronicler, journalist, essayist, patriot and Liberal politician. According to Eladio Cortés, during his lifetime he was consi ...

, but also the more moderate Ignacio Comonfort.

Clashes in the cabinet led to the resignation of the radical Ocampo, but the administration was still determined to pass significant reforms. On November 23, 1855, the Juárez Law, named after the Minister of Justice, substantially reduced the jurisdiction of military and ecclesiastical courts which existed for soldiers and clergy.

Further dissension within liberal ranks led to Alvarez's resignation and the more moderate Comonfort becoming president on December 11, who chose a new cabinet. A constituent congress began meeting on February 14, 1856 and ratified the Juárez law. In June, another major controversy emerged over the promulgation of the Lerdo law

The Lerdo Law ( Spanish: ''Ley Lerdo'') was the common name for the Reform law that was formally known as the Confiscation of Law and Urban Ruins of the Civil and Religious Corporations of Mexico. It targeted not only property owned by the Catho ...

, named after the secretary of the treasury, Miguel Lerdo de Tejada. The law aimed at disentailing the collective ownership of real estate by the Roman Catholic Church and indigenous communities. It forced 'civil or ecclesiastical institutions' to sell any land that they owned, with the tenants receiving priority and generous terms for purchasing the community-held land they cultivated. The law sought to undermine the economic power of the Church and to force create a class of yeoman farmers of indigenous community members. The law was envisioned as a way to develop Mexico's economy by increasing the number of indigenous private property owners, but in practice the land was bought up by rich speculators. Most of the lost indigenous lands community lands increased the size of large landed estates, hacienda

An ''hacienda'' ( or ; or ) is an estate (or '' finca''), similar to a Roman '' latifundium'', in Spain and the former Spanish Empire. With origins in Andalusia, ''haciendas'' were variously plantations (perhaps including animals or orchard ...

s.

The Constitution of 1857 was promulgated on February 5, 1857 and it integrated both the Juárez and the Lerdo laws. It was meant to take into effect on September 16. On March 17 it was decreed that all civil servants had to publicly swear and sign and oath to it. The Catholic Church decreed excommunication for anyone that took the oath, and subsequently many Catholics in the Mexican government lost their jobs for refusing the oath.

Controversy over the constitution continued to rage, and Comonfort himself was rumored to be conspiring to form a new government. On December 17, 1857 General Félix Zuloaga proclaimed the Plan of Tacubaya

The Plan of Tacubaya ( es, Plan de Tacubaya), sometimes called the Plan of Zuloaga, was issued by conservative Mexican General Félix Zuloaga on 17 December 1857 in Tacubaya against the liberal Constitution of 1857. The plan nullified the Const ...

, declaring the Constitution of 1857 nullified, and offered supreme power to President Comonfort, who was to convoke a new constitutional convention to produce a new document more in accord with Mexican interests. In response, congress deposed President Comonfort, but Zuloaga's troops entered the capital on the 18th and dissolved congress. The following day, Comonfort accepted the Plan of Tacubaya, and released a manifesto making the case that more moderate reforms were needed under the current circumstances.

The Plan of Tacubaya did not lead to a national reconciliation, and as Comonfort realized this he began to back away from Zuloaga and the conservatives. He resigned from the presidency and even began to lead skirmishes against the Zuloaga government, but after he was abandoned by most of his loyal troops, Comonfort left the capital on January 11, 1858, with the constitutional presidency having passed to the President of the Supreme Court, Benito Juárez

Benito Pablo Juárez García (; 21 March 1806 – 18 July 1872) was a Mexican liberal politician and lawyer who served as the 26th president of Mexico from 1858 until his death in office in 1872. As a Zapotec, he was the first indigenous pre ...

. The Conservative government in the capital summoned a council of representatives that elected Zuloaga as president, and the states of Mexico proclaimed their loyalties to either the conservative Zuloaga or liberal Juárez governments. The Reform War had now begun.

The War

Flight of the Liberal Government

President Juárez and his ministers fled from Mexico City to

President Juárez and his ministers fled from Mexico City to Querétaro

Querétaro (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Querétaro ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Querétaro, links=no; Otomi: ''Hyodi Ndämxei''), is one of the 32 federal entities of Mexico. It is divided into 18 municipalities. Its cap ...

. General Zuloaga, knowing the strategic importance of the Gulf Coast state of Veracruz, tried to win over its governor, Gutierrez Zamora, who however affirmed his support for the government of Juárez. Santiago Vidaurri and Manuel Doblado

Manuel Doblado Partida (12 June 1818 – 19 June 1865) was a Mexican prominent liberal politician and lawyer who served as congressman, Governor of Guanajuato, Minister of Foreign Affairs (1861) in the cabinet of President Juárez and fought ...

organized Liberal forces in the north and led a liberal coalition in the interior headquartered in the town of Celaya

Celaya (; ) is a city and its surrounding municipality in the state of Guanajuato, Mexico, located in the southeast quadrant of the state. It is the third most populous city in the state, with a 2005 census population of 310,413. The municipality f ...

. On March 10, 1858, liberal forces under Anastasio Parrodi, governor of Jalisco

Jalisco (, , ; Nahuatl: Xalixco), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Jalisco ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Jalisco ; Nahuatl: Tlahtohcayotl Xalixco), is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the 32 Federal ...

, and Leandro Valle lost the Battle of Salamanca

The Battle of Salamanca (in French and Spanish known as the Battle of Arapiles) on 22July 1812 was a battle in which an Anglo-Portuguese army under the Earl of Wellington defeated Marshal Auguste Marmont's French forces at Arapiles, so ...

, which opened up the interior of the country to the conservatives.

Juárez was in Jalisco's capital Guadalajara at this time, when on 13-15 March part of the army there mutinied and imprisoned him, threatening his life. Liberal minister and fellow prisoner Guillermo Prieto

Guillermo Prieto Pradillo (10 February 1818 – 2 March 1897) was a Mexican novelist, short-story writer, poet, chronicler, journalist, essayist, patriot and Liberal politician. According to Eladio Cortés, during his lifetime he was consi ...

dissuaded the hostile soldiers from shooting Juárez, an event now memorialized by a statue. As rival factions struggled to control the city, Juárez and other liberal prisoners were released on agreement after which Guadalajara was fully captured by conservatives by the end of March. Conservatives took the silver mining center of Zacatecas on 12 April. Juárez reconstituted his regime in Veracruz, embarking from the west coast port of Manzanillo, crossing Panama, and arriving in Veracruz on May 4, 1858, making it the liberal capital.

Conservative Advances

Juárez made Santos Degollado the head of the Liberal's armies, who went on to defeat upon defeat. Miramón defeated him in the Battle of Atenquique July 2. On July 24, Miramón capturedGuanajuato

Guanajuato (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Guanajuato ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Guanajuato), is one of the 32 states that make up the Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into 46 municipalities and its capital city i ...

, and San Luis Potosi was captured by the conservatives on September 12. Vidaurri was defeated at the Battle of Ahualulco on September 29. By October the conservatives were at the height of their strength.

The liberals failed to take Mexico City on the 14th of October, but Santos Degollado captured Guadalajara on the 27th of October, after a thirty days siege that left a third of the city in ruins. This victory caused consternation at the conservative capital, but Guadalajara was taken back by Márquez on December 14.

The failure of Zuloaga's government to produce a constitution actually led to a conservative revolt against him led by General Echegaray. He resigned in favor of Manuel Robles Pezuela

Manuel Robles Pezuela (23 May 1817 - 23 March 1862) was a military engineer, military commander, and eventually interim president of Mexico during a civil war, the War of Reform, being waged between conservatives and liberals, in which he served ...

on December 23. On December 30 a conservative junta in Mexico City elected General Miguel Miramón

Miguel Gregorio de la Luz Atenógenes Miramón y Tarelo, known as Miguel Miramón, (29 September 1831 – 19 June 1867) was a Mexican conservative general who became president of Mexico at the age of twenty seven during the Reform War, serving ...

as president.First Veracruz Offensive

President Miramón's most important military priority was now the capture of Veracruz, the liberals' stronghold. He left the capital on February 16, leading the troops in person along with his minister of war.

President Miramón's most important military priority was now the capture of Veracruz, the liberals' stronghold. He left the capital on February 16, leading the troops in person along with his minister of war. Aguascalientes

Aguascalientes (; ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Aguascalientes ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Aguascalientes), is one of the 32 states which comprise the Federal Entities of Mexico. At 22°N and with an average altitude of a ...

and Guanajuato

Guanajuato (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Guanajuato ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Guanajuato), is one of the 32 states that make up the Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into 46 municipalities and its capital city i ...

had fallen to the liberals. Liberal troops in the West were led by Degollado and headquartered in Morelia

Morelia (; from 1545 to 1828 known as Valladolid) is a city and municipal seat of the municipality of Morelia in the north-central part of the state of Michoacán in central Mexico. The city is in the Guayangareo Valley and is the capital and lar ...

, which now served as a liberal arsenal. The conservatives fell ill with malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. ...

, endemic in the Gulf Coast, and abandoned the siege of Veracruz by March 29. Liberal General Degollado made another attempt on Mexico City in early April and was routed in the Battle of Tacubaya by Leonardo Márquez

Leonardo Márquez Araujo (8 January 1820 – 5 July 1913) was a conservative Mexican general. He led forces in opposition to the Liberals led by Benito Juarez, but following defeat in the reform war was forced to guerilla warfare. Later, he help ...

. Márquez captured a large amount of war materiel and gained infamy for including medics among those executed in the aftermath of the battle.

On April 6, the Juárez government was recognized by the United States during the Buchanan Buchanan may refer to:

People

* Buchanan (surname)

Places Africa

* Buchanan, Liberia, a large coastal town

Antarctica

* Buchanan Point, Laurie Island

Australia

* Buchanan, New South Wales

* Buchanan, Northern Territory, a locality

* Bucha ...

administration. Miramón unsuccessfully attempted to besiege Veracruz in June and July. On July 12, the liberal government nationalized the property of the Catholic church, and suppressed the monasteries and convents, the sale of which provided the liberal war effort with new funds, though not as much as had been hoped for since speculators were waiting for more stable times to make purchases.

Miramón met the liberal forces in November at which a truce was declared and a conference was held on the matter of the Constitution of 1857 and the possibility of a constituent congress. Negotiations broke down and hostilities resumed on the 12th after which Degollado was routed at the Battle of Las Vacas.

Second Veracruz Offensive

On December 14, 1859, Melchor Ocampo signed the McLane–Ocampo Treaty, which granted the United States perpetual rights to transport goods and troops across three key trade routes in Mexico and granted Americans an element ofextraterritoriality

In international law, extraterritoriality is the state of being exempted from the jurisdiction of local law, usually as the result of diplomatic negotiations.

Historically, this primarily applied to individuals, as jurisdiction was usually cl ...

. The treaty caused consternation among the conservatives and some liberals, the European press, and even members of Juarez's cabinet. The issue was rendered moot when the U.S. Senate failed to approve the treaty.

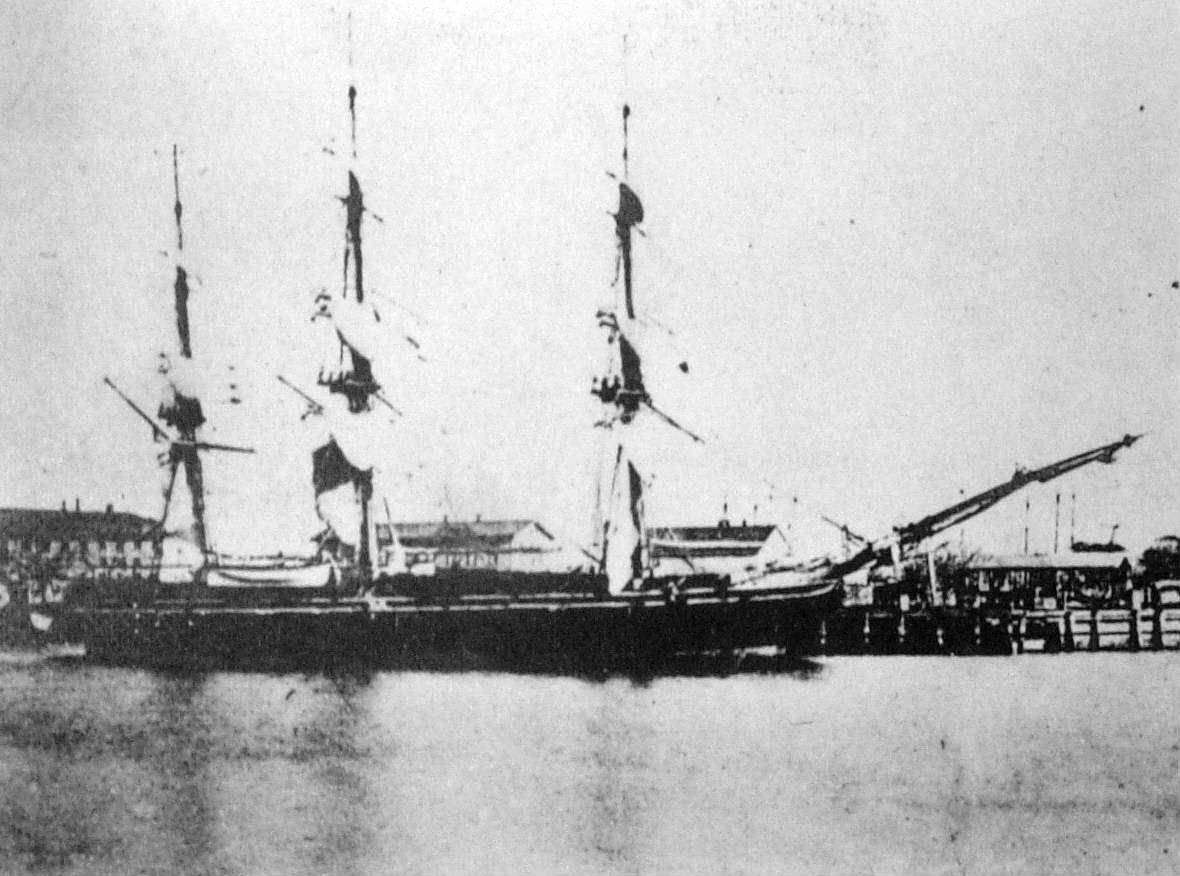

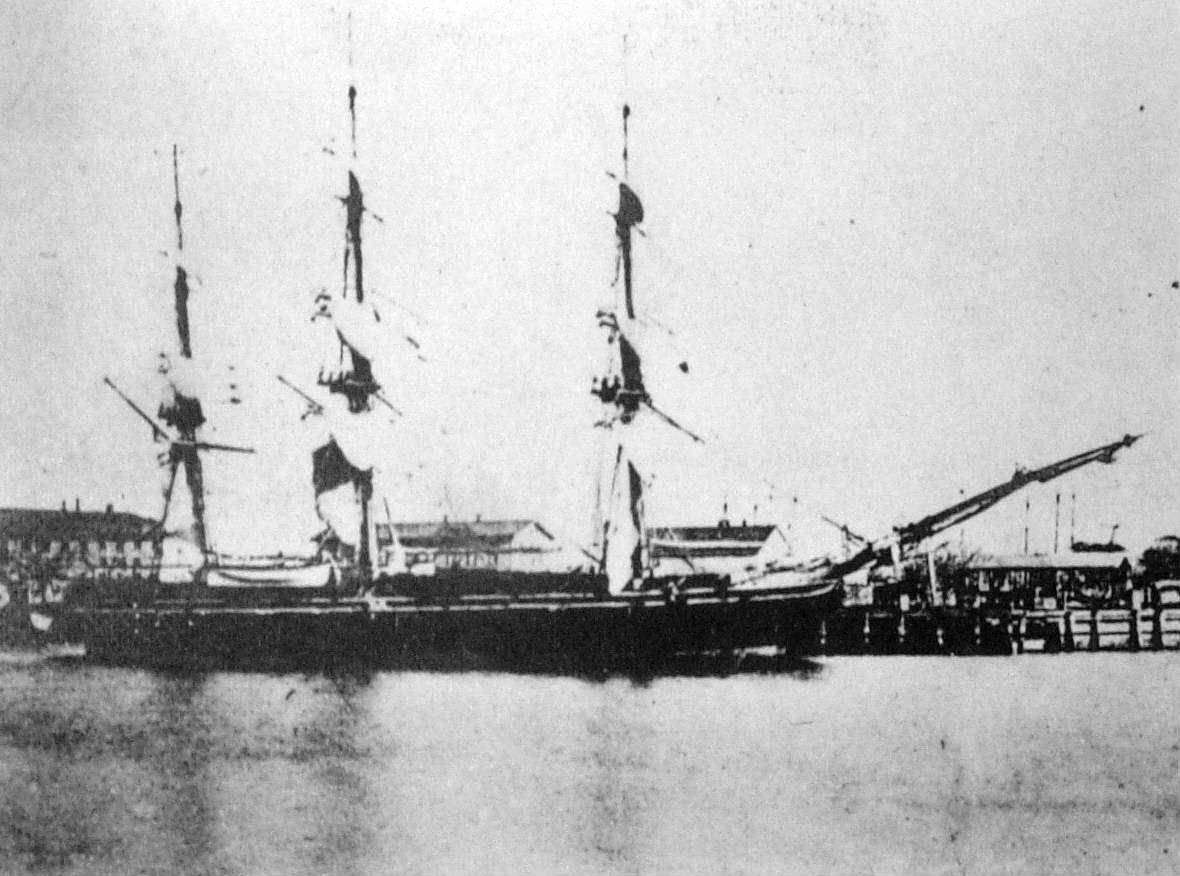

Miramón was preparing another siege of Veracruz, leaving the conservative capital of Mexico City on February 8, leading his troops in person along with his war minister, hoping to rendezvous with a small naval squadron led by the Mexican General Marin who was disembarking from Havana. The United States Navy however had orders to intercept it. Miramón arrived at

Miramón was preparing another siege of Veracruz, leaving the conservative capital of Mexico City on February 8, leading his troops in person along with his war minister, hoping to rendezvous with a small naval squadron led by the Mexican General Marin who was disembarking from Havana. The United States Navy however had orders to intercept it. Miramón arrived at Medellín

Medellín ( or ), officially the Municipality of Medellín ( es, Municipio de Medellín), is the second-largest city in Colombia, after Bogotá, and the capital of the department of Antioquia. It is located in the Aburrá Valley, a central re ...

on the 2nd of March, and awaited Marin's attack in order to begin the siege. The U.S. steamer ''Indianola'' had been anchored near the fortress of San Juan de Ulúa

San Juan de Ulúa, also known as Castle of San Juan de Ulúa, is a large complex of fortresses, prisons and one former palace on an island of the same name in the Gulf of Mexico overlooking the seaport of Veracruz, Mexico. Juan de Grijalva ...

, to defend Veracruz from attack.

On March 6, Marin's squadron arrived in Veracruz, and was captured by U.S. Navy Captain Joseph R. Jarvis in the Battle of Antón Lizardo

The Battle of Antón Lizardo was a naval engagement of the Mexican civil war between liberals and conservative governments, (the Reform War), which took place off the Gulf Coast town of Antón Lizardo, Mexico in 1860. A Mexican Navy officer, Rear ...

The ships were sent to New Orleans, along with the now imprisoned General Marin, depriving the conservatives of an attack force and the substantial artillery, guns, and rations that they were carrying onboard for delivery to Miramón. Miramón's effort to besiege Veracruz was abandoned on the 20th of March, and he arrived back in Mexico City on April 7.

Liberal Triumph

The conservatives also suffered defeats in the interior, losingAguascalientes

Aguascalientes (; ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Aguascalientes ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Aguascalientes), is one of the 32 states which comprise the Federal Entities of Mexico. At 22°N and with an average altitude of a ...

and San Luis Potosí

San Luis Potosí (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of San Luis Potosí ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de San Luis Potosí), is one of the 32 states which compose the Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided in 58 municipalities and i ...

before the end of April. Degollado was sent into the interior to lead the liberal campaign since their enemies had now exhausted their resources. He appointed José López Uraga as Quartermaster General Uraga split his troops and attempted to lure out Miramón to isolate him, but in late May Uraga then committed the strategic blunder of attempting to assault Guadalajara with Mirámon's troops behind him. The assault failed and Uraga was taken prisoner.

Miramón was routed on August 10, in Silao

Silao (), officially Silao de la Victoria, is a city in the west-central part of the state of Guanajuato in Mexico. It is the seat of the municipality with the same name. As of the 2005 census, the city had a population of 147,123, making it th ...

, which resulted in his commander Tomás Mejía Tomás may refer to:

* Tomás (given name)

* Tomás (surname) Tomás is a Spanish and Portuguese surname, equivalent of ''Thomas''.

It may refer to:

* Antonio Tomás (born 1985), professional Spanish footballer

* Belarmino Tomás (1892–1950) ...

being taken prisoner, and Miramón retreated to Mexico City. In response to the disaster, Miramón resigned as president to seek a vote of confidence. The conservative junta elected him president again after a two days interregnum. By the end of August, liberals were preparing for a decisive final battle. The Mexico City was cut off from the rest of the country. Guadalajara was surrounded by 17,000 liberal troops while the conservatives in the city only had 7000. The conservative commander Castillo surrendered without firing a shot and was allowed to leave the city with his troops. General Leonardo Márquez

Leonardo Márquez Araujo (8 January 1820 – 5 July 1913) was a conservative Mexican general. He led forces in opposition to the Liberals led by Benito Juarez, but following defeat in the reform war was forced to guerilla warfare. Later, he help ...

was routed on the 10th of November, attempting to reinforce General Castillo without being aware of his surrender.

Miramón on November 3 convoked a war council, including in it prominent citizens to meet the crisis and by November 5 it was resolved to fight until the end. The conservatives were not struggling with a shortage of funds and increasing defections. Nonetheless, Miramon gained a victory when he attacked the liberal headquarters of Toluca

Toluca , officially Toluca de Lerdo , is the state capital of the State of Mexico as well as the seat of the Municipality of Toluca. With a population of 910,608 as of the 2020 census, Toluca is the fifth most populous city in Mexico. The city ...

on the 9th of December, in which almost all of their forces were captured. With the tide turning to liberal victories, Juárez rejected the McLane-Ocampo Treaty in November, while the treaty had previously been rejected in the U.S. Senate May 31 and not ratified. Juárez had secured recognition from the U.S. government with the opening of negotiations with the United States, rejected outright sale of Mexican territory to the United States, and received aid from the U.S. Navy, in the end securing benefits to Mexico without actually concluding the treaty.

In early December as the tide of war had clearly turned to the liberals, Juárez signed the Law for the Liberty of Religious Worship on December 4, the final step in the liberals' program to disempower the Roman Catholic Church by allowing religious tolerance in Mexico.

General González Ortega approached Mexico City with reinforcements. The decisive battle took place on December 22, at Calpulalpan

Calpulalpan officially as Heroic City of Calpulalpan, is a mexican city, head and main urban center of the homonymous municipality, located to the west of the state of Tlaxcala. With 33 263 inhabitants in 2010 according to the population and hou ...

. The conservatives had 8,000 troops and the liberals 16,000. Miramon lost and retreated back towards the capital.

Another conservative war council agreed to surrender. The conservative government fled the city, and Miramón himself escaped to European exile. Márquez escaped to the mountains of Michoacan. The triumphant liberals entered the city with 25,000 troops on January 1, 1861, and Juárez entered the capital on January 11.

Foreign Powers

After Zuloaga's coup, the conservative government was recognized swiftly by Spain and France. Neither conservatives nor liberals ever had official foreign troops as part of their respective armed forces. The conservative government signed the Mon-Almonte Treaty with Spain, promising to pay the Spanish government indemnities in exchange for aid. The liberals also sought foreign support from the United States. Mexico signed the McLane-Ocampo Treaty, which would have granted the United States perpetual transit and extraterritorial rights in Mexico. This treaty was denounced by conservatives and some liberals, with Juárez countering that the territorial losses to the United States occurred under the conservatives. With the liberal victory, Juárez's government was unable to meet foreign debt obligations, some of which stemmed from the Mon-Almonte Treaty. When Juárez's government suspended payments, the pretext was used to inaugurate theSecond French Intervention in Mexico

The Second French Intervention in Mexico ( es, Segunda intervención francesa en México), also known as the Second Franco-Mexican War (1861–1867), was an invasion of Mexico, launched in late 1862 by the Second French Empire, which hoped to ...

.

During the Reform War as the military stalemate continued, some liberals considered the idea of foreign intervention. Brothers Miguel Lerdo de Tejada and Sebastián were liberal politicians from Veracruz and had commercial connections with the United States. Miguel Lerdo, Juárez's Minister of Finance, attempted to negotiate a loan with the United States He was reported to despair of Mexico's situation and saw some form of protection from the United States as the way forward and the way to prevent a resurgence of Spanish colonialism. Correspondence between Melchor Ocampo

Melchor Ocampo (5 January 1814 – 3 June 1861) was a Mexican lawyer, scientist, and politician. A mestizo and a radical liberal, he was fiercely anticlerical, perhaps an atheist, and his early writings against the Catholic Church in Mexico ga ...

and Santos Degollado discussing Lerdo's attempt to negotiate a loan was captured and published by conservatives. Degollado was later to advocate mediation through the diplomatic corps in Mexico to end the conflict. Juárez flatly refused Degollado's call to resign, since Juárez saw that as turning over Mexico's future to European powers.Hamnett, ''Juárez'', 124.

Aftermath

A French invasion and the establishment of the Second Mexican Empire followed almost immediately after the end of the Reform War, and key figures of the Reform War would continue to play roles during the rise and fall of the Empire. While the main fighting in the Reform War was over by the end of 1860, guerilla conflict continued to be waged in the countryside. After the fall of the conservative government, GeneralLeonardo Marquez

Leonardo is a masculine given name, the Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese equivalent of the English, German, and Dutch name, Leonard.

People

Notable people with the name include:

* Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), Italian Renaissance scientis ...

remained at large, and in June, 1861, he succeeded in assassinating Melchor Ocampo

Melchor Ocampo (5 January 1814 – 3 June 1861) was a Mexican lawyer, scientist, and politician. A mestizo and a radical liberal, he was fiercely anticlerical, perhaps an atheist, and his early writings against the Catholic Church in Mexico ga ...

. President Juarez sent the former head of his troops during the Reform War, Santos Degollado after Marquez, only for Marquez to succeed in killing Degollado as well.

Having been influenced by Mexican monarchist exiles, and using Juarez' suspension of foreign debts as a pretext, and with the American Civil War preventing the enforcement of the Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine was a United States foreign policy position that opposed European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It held that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign powers was a potentially hostile act ...

, Napoleon III invaded Mexico in 1862, and sought local help in setting up a monarchical client state. Former liberal president Ignacio Comonfort

Ignacio Gregorio Comonfort de los Ríos (; 12 March 1812 – 13 November 1863), known as Ignacio Comonfort, was a Mexican politician and soldier who was also president during one of the most eventful periods in 19th century Mexican history: La ...

, who had played such a key role in the outbreak of the Reform War, was killed in action that year, having returned to the country to fight the French, and having been given a military command. Former conservative president during the Reform War Manuel Robles Pezuela

Manuel Robles Pezuela (23 May 1817 - 23 March 1862) was a military engineer, military commander, and eventually interim president of Mexico during a civil war, the War of Reform, being waged between conservatives and liberals, in which he served ...

was also executed in 1862 by the Juarez government for attempting to help the French. Seeing the intervention as an opportunity to undo the Reform, conservative generals and statesmen who had played a role during the War of the Reform joined the French and a conservative assembly voted in 1863 to invite Habsburg archduke Maximilian to become Emperor of Mexico.

The Emperor however proved to be of liberal inclination, and ended up ratifying the Reform laws. Regardless, the liberal government of Benito Juárez, still resisted and fought the French and Mexican Imperial forces with the backing of the United States, whom after the end of the Civil War could now once again enforce the Monroe Doctrine. The French eventually withdrew in 1866, leading the monarchy to collapse in 1867. Former president Miguel Miramon, and conservative general Tomas Mejia Tomas may refer to:

People

* Tomás (given name), a Spanish, Portuguese, and Gaelic given name

* Tomas (given name), a Swedish, Dutch, and Lithuanian given name

* Tomáš, a Czech and Slovak given name

* Tomas (surname), a French and Croatian surna ...

would die alongside the Emperor, being executed by firing squad on June 19, 1867. Santiago Vidaurri, once Juarez' commander in the north during the Reform War had actually joined the imperialists, but he was captured and executed for his betrayal on July 8, 1867. Leonardo Marquez

Leonardo is a masculine given name, the Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese equivalent of the English, German, and Dutch name, Leonard.

People

Notable people with the name include:

* Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), Italian Renaissance scientis ...

would once again escape, this time to Cuba, living until 1913 and publishing a defense of his role in the Empire.

See also

*Cristero War

The Cristero War ( es, Guerra Cristera), also known as the Cristero Rebellion or es, La Cristiada, label=none, italics=no , was a widespread struggle in central and western Mexico from 1 August 1926 to 21 June 1929 in response to the implementa ...

*Carlist Wars

The Carlist Wars () were a series of civil wars that took place in Spain during the 19th century. The contenders fought over claims to the throne, although some political differences also existed. Several times during the period from 1833 to 18 ...

References

Further reading

*Hamnett, Brian. ''Juárez''. London: Longman 1994. *Olliff, Donathan. ''Reforma Mexico and the United States: A Search for Alternatives to Annexation, 1854-1861''. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press 1981. *Powell, T.G. "Priests and Peasants in Central Mexico: Social Conflict during La Reforma". ''Hispanic American Historical Review'' 57(1997): 296-313. *Sinkin, Richard. ''The Mexican Reform, 1855-1876: A Study in Liberal Nation Building''. Austin: Institute of Latin American Studies 1979. {{Authority control Conflicts in 1857 Conflicts in 1858 Conflicts in 1859 Conflicts in 1860 Conflicts in 1861 04 1857 in Mexico 1858 in Mexico 1859 in Mexico 1860 in Mexico 1861 in Mexico Civil wars involving the states and peoples of North America Second French intervention in Mexico Wars involving Mexico 19th century in Mexico Conservatism in Mexico Liberalism in Mexico Civil wars of the Industrial era