Ralph Vaughan Williams on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

, WorldCat, retrieved 18 October 2015 the ''Serenade to Music'', and the Fifth Symphony, recorded in 1951 and 1952, respectively. There is a recording of Vaughan Williams conducting the ''St Matthew Passion'' with his Leith Hill Festival forces. In the early days of LP in the 1950s Vaughan Williams was better represented in the record catalogues than most British composers. ''The Record Guide'' (1955) contained nine pages of listings of his music on disc, compared with five for

, WorldCat, retrieved 18 October 2015 Most of the orchestral recordings have been by British orchestras and conductors, but notable non-British conductors who have made recordings of Vaughan Williams's works include

"Plaque: Ralph Vaughan Williams—Bust"

, London Remembers, retrieved 19 October

The Ralph Vaughan Williams Society

The Letters of Ralph Vaughan Williams

* * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Vaughan Williams, Ralph 1872 births 1958 deaths 19th-century British composers 19th-century British male musicians 19th-century classical composers 19th-century English musicians 20th-century British male musicians 20th-century classical composers 20th-century English composers 20th-century English musicians Academics of Birkbeck, University of London Alumni of the Royal College of Music Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge Brass band composers British Army personnel of World War I British ballet composers Burials at Westminster Abbey Choral composers Classical composers of church music Composers for harmonica Darwin–Wedgwood family Deaf classical musicians Deaf people from England Decca Records artists English agnostics English classical composers English folk-song collectors English male classical composers English opera composers English people of Welsh descent English Romantic composers Golders Green Crematorium Male opera composers Military personnel from Gloucestershire Members of the Order of Merit Music in Gloucestershire Musicians from Gloucestershire Oratorio composers People educated at Charterhouse School People from Cotswold District People of the Victorian era Pupils of Charles Villiers Stanford Royal Army Medical Corps soldiers Royal Artillery officers Royal Philharmonic Society Gold Medallists

Ralph Vaughan Williams, (; 12 October 1872– 26 August 1958) was an English composer. His works include operas, ballets, chamber music, secular and religious vocal pieces and orchestral compositions including nine symphonies, written over sixty years. Strongly influenced by

"Williams, Ralph Vaughan (1872–1958)"

, ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, retrieved 10 October 2015 His paternal forebears were of mixed English and Welsh descent; many of them went into the law or the Arthur Vaughan Williams died suddenly in February 1875, and his widow took the children to live in her family home, Leith Hill Place,

Arthur Vaughan Williams died suddenly in February 1875, and his widow took the children to live in her family home, Leith Hill Place,

Vaughan Williams had a modest private income, which in his early career he supplemented with a variety of musical activities. Although the organ was not his preferred instrument, the only post he ever held for an annual salary was as a church organist and choirmaster. He held the position at St Barnabas, in the inner London district of South Lambeth, from 1895 to 1899 for a salary of £50 a year. He disliked the job, but working closely with a choir was valuable experience for his later undertakings.

Vaughan Williams had a modest private income, which in his early career he supplemented with a variety of musical activities. Although the organ was not his preferred instrument, the only post he ever held for an annual salary was as a church organist and choirmaster. He held the position at St Barnabas, in the inner London district of South Lambeth, from 1895 to 1899 for a salary of £50 a year. He disliked the job, but working closely with a choir was valuable experience for his later undertakings.

In October 1897 Adeline and Vaughan Williams were married. They honeymooned for several months in Berlin, where he studied with

In October 1897 Adeline and Vaughan Williams were married. They honeymooned for several months in Berlin, where he studied with

''Who Was Who'', Oxford University Press, 2014, retrieved 10 October 2015 The song "Linden Lea" became the first of his works to appear in print, published in the magazine ''The Vocalist'' in April 1902 and then as separate sheet music. In addition to composition he occupied himself in several capacities during the first decade of the century. He wrote articles for musical journals and for the second edition of ''

Ravel took few pupils, and was known as a demanding taskmaster for those he agreed to teach. Vaughan Williams spent three months in Paris in the winter of 1907–1908, working with him four or five times each week. There is little documentation of Vaughan Williams's time with Ravel; the musicologist Byron Adams advises caution in relying on Vaughan Williams's recollections in the ''Musical Autobiography'' written forty-three years after the event. The degree to which the French composer influenced the Englishman's style is debated. Ravel declared Vaughan Williams to be "my only pupil who does not write my music";Adams (2013), p. 40 nevertheless, commentators including Kennedy, Adams, Hugh Ottaway and Alain Frogley find Vaughan Williams's instrumental textures lighter and sharper in the music written after his return from Paris, such as the String Quartet in G minor, '' On Wenlock Edge'', the Overture to ''

Ravel took few pupils, and was known as a demanding taskmaster for those he agreed to teach. Vaughan Williams spent three months in Paris in the winter of 1907–1908, working with him four or five times each week. There is little documentation of Vaughan Williams's time with Ravel; the musicologist Byron Adams advises caution in relying on Vaughan Williams's recollections in the ''Musical Autobiography'' written forty-three years after the event. The degree to which the French composer influenced the Englishman's style is debated. Ravel declared Vaughan Williams to be "my only pupil who does not write my music";Adams (2013), p. 40 nevertheless, commentators including Kennedy, Adams, Hugh Ottaway and Alain Frogley find Vaughan Williams's instrumental textures lighter and sharper in the music written after his return from Paris, such as the String Quartet in G minor, '' On Wenlock Edge'', the Overture to ''

"The merry widow"

, ''The Daily Telegraph'', 4 May 2002 Ursula recorded that during air raids all three slept in the same room in adjacent beds, holding hands for comfort. In 1943 Vaughan Williams conducted the premiere of his Fifth Symphony at the

In 1943 Vaughan Williams conducted the premiere of his Fifth Symphony at the

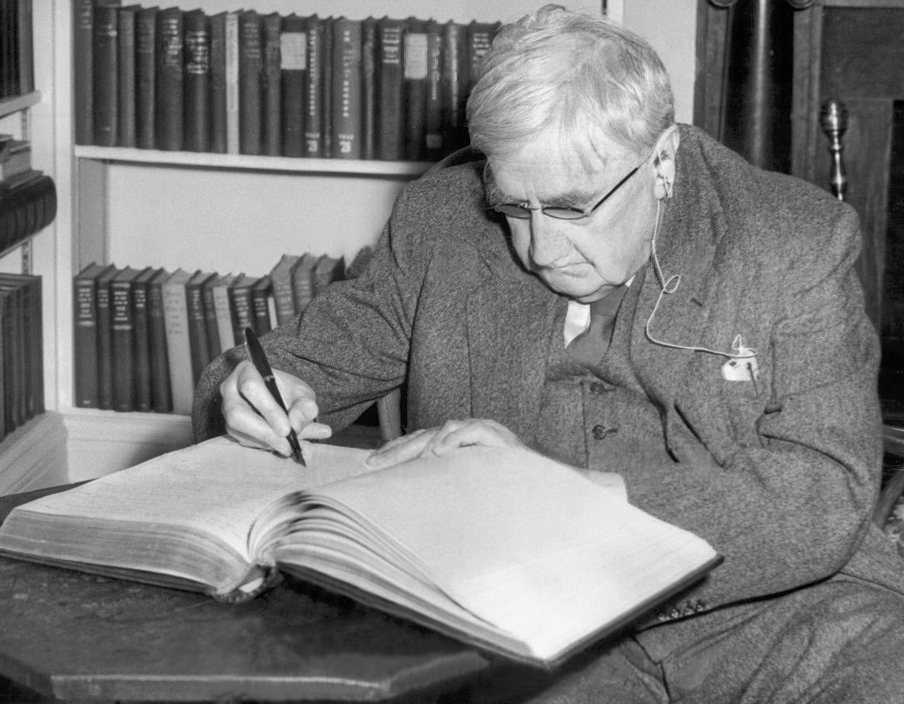

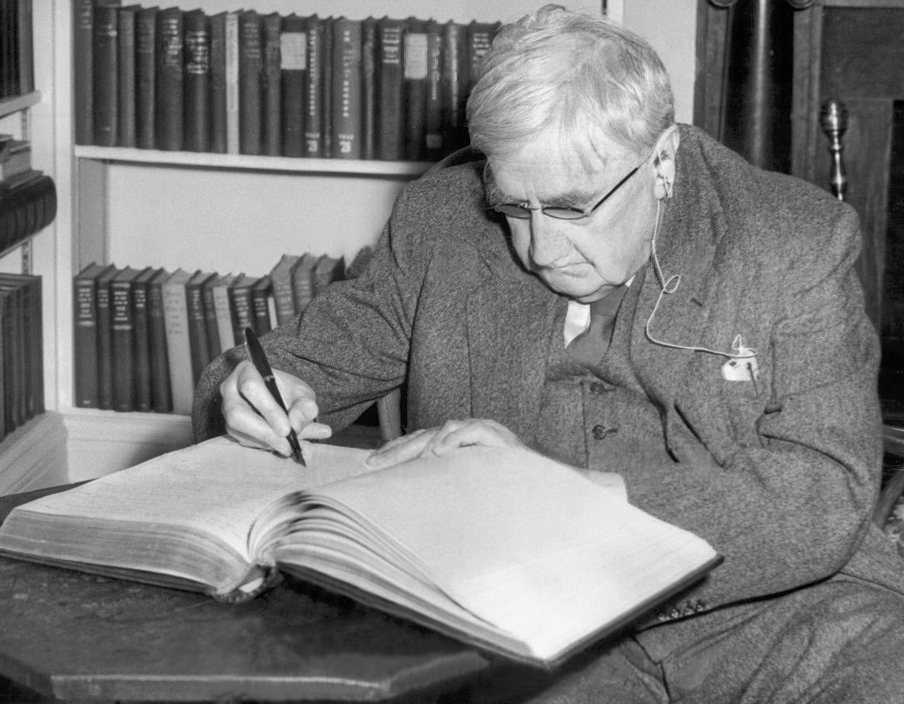

Having returned to live in London, Vaughan Williams, with Ursula's encouragement, became much more active socially and in '' pro bono publico'' activities. He was a leading figure in the Society for the Promotion of New Music, and in 1954 he set up and endowed the RVW Trust to support young composers and promote new or neglected music. He and his wife travelled extensively in Europe, and in 1954 he visited the US once again, having been invited to lecture at

Having returned to live in London, Vaughan Williams, with Ursula's encouragement, became much more active socially and in '' pro bono publico'' activities. He was a leading figure in the Society for the Promotion of New Music, and in 1954 he set up and endowed the RVW Trust to support young composers and promote new or neglected music. He and his wife travelled extensively in Europe, and in 1954 he visited the US once again, having been invited to lecture at

"Vaughan Williams, Ralph"

''The Oxford Dictionary of Music'', 2nd edition, Oxford University Press, retrieved 10 October 2015 Vaughan Williams's music is often described as visionary; Kennedy cites the masque ''Job'' and the Fifth and Ninth Symphonies. Vaughan Williams's output was prolific and wide-ranging. For the voice he composed songs, operas, and choral works ranging from simpler pieces suitable for amateurs to demanding works for professional choruses. His comparatively few chamber works are not among his better-known compositions. Some of his finest works elude conventional categorisation, such as the '' Serenade to Music'' (1938) for sixteen solo singers and orchestra; ''Flos Campi'' (1925) for solo viola, small orchestra, and small chorus; and his most important chamber work, in Howes's view—not purely instrumental but a song cycle—''On Wenlock Edge'' (1909) with accompaniment for string quartet and piano. In 1955 the authors of ''The Record Guide'', Edward Sackville-West and Desmond Shawe-Taylor, wrote that Vaughan Williams's music showed an exceptionally strong individual voice: Vaughan Williams's style is "not remarkable for grace or politeness or inventive colour", but expresses "a consistent vision in which thought and feeling and their equivalent images in music never fall below a certain high level of natural distinction". They commented that the composer's vision is expressed in two main contrasting moods: "the one contemplative and trance-like, the other pugnacious and sinister". The first mood, generally predominant in the composer's output, was more popular, as audiences preferred "the stained-glass beauty of the Tallis Fantasia, the direct melodic appeal of the ''Serenade to Music'', the pastoral poetry of ''The Lark Ascending'', and the grave serenity of the Fifth Symphony". By contrast, as in the ferocity of the Fourth and Sixth Symphonies and the Concerto for Two Pianos: "in his grimmer moods Vaughan Williams can be as frightening as Sibelius and Bartók".

"Vaughan Williams, Ralph"

''Grove Music Online'', Oxford University Press, retrieved 10 October 2015 In addition to large woodwind and percussion sections the score features a prominent part for

''Grove'' lists more than thirty works by Vaughan Williams for orchestra or band over and above the symphonies. They include two of his most popular works—the ''

''Grove'' lists more than thirty works by Vaughan Williams for orchestra or band over and above the symphonies. They include two of his most popular works—the ''

Despite his agnosticism Vaughan Williams composed many works for church performance. His two best known hymn tunes, both from c. 1905, are "Down Ampney" to the words "Come Down, O Love Divine", and "''Sine nomine''" "

Despite his agnosticism Vaughan Williams composed many works for church performance. His two best known hymn tunes, both from c. 1905, are "Down Ampney" to the words "Come Down, O Love Divine", and "''Sine nomine''" "

"Hugh the Drover"

''The Stage'', 25 November 2010, retrieved 13 October 2015 In the view of the critic ''Job: A Masque for Dancing'' (1930) was the first large-scale ballet by a modern British composer. Vaughan Williams's liking for long ''tableaux'', however disadvantageous in his operas, worked to successful effect in this ballet. The work is inspired by

''Job: A Masque for Dancing'' (1930) was the first large-scale ballet by a modern British composer. Vaughan Williams's liking for long ''tableaux'', however disadvantageous in his operas, worked to successful effect in this ballet. The work is inspired by

television. Vaughan Williams later recast it a cantata, ''Epithalamion'' (1957).

''The Pilgrim's Progress'' (1951), the composer's last opera, was the culmination of more than forty years' intermittent work on the theme of Bunyan's religious allegory. Vaughan Williams had written incidental music for an amateur dramatisation in 1906, and had returned to the theme in 1921 with the one-act ''The Shepherds of the Delectable Mountains'' (finally incorporated, with amendments, into the 1951 opera). The work has been criticised for a preponderance of slow music and stretches lacking in dramatic action,Kennedy (1997), p. 428 but some commentators believe the work to be one of Vaughan Williams's supreme achievements. Summaries of the music vary from "beautiful, if something of a stylistic jumble" (Saylor) to "a synthesis of Vaughan Williams's stylistic progress over the years, from the pastoral mediation of the 1920s to the angry music of the middle symphonies and eventually the more experimental phase of the ''Sinfonia antartica'' in his last decade" (Kennedy).

Tudor music

Early music of Britain and Ireland, from the earliest recorded times until the beginnings of the Baroque in the 17th century, was a diverse and rich culture, including sacred and secular music and ranging from the popular to the elite. Each of the ...

and English folk-song

The folk music of England is a tradition-based music which has existed since the later medieval period. It is often contrasted with courtly, classical and later commercial music. Folk music traditionally was preserved and passed on orally wit ...

, his output marked a decisive break in British music from its German-dominated style of the 19th century.

Vaughan Williams was born to a well-to-do family with strong moral views and a progressive social life. Throughout his life he sought to be of service to his fellow citizens, and believed in making music as available as possible to everybody. He wrote many works for amateur and student performance. He was musically a late developer, not finding his true voice until his late thirties; his studies in 1907–1908 with the French composer Maurice Ravel helped him clarify the textures of his music and free it from Teutonic influences.

Vaughan Williams is among the best-known British symphonists, noted for his very wide range of moods, from stormy and impassioned to tranquil, from mysterious to exuberant. Among the most familiar of his other concert works are ''Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis

''Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis'', also known as the ''Tallis Fantasia'', is a one-movement work for string orchestra by Ralph Vaughan Williams. The theme is by the 16th-century English composer Thomas Tallis. The Fantasia was first perf ...

'' (1910) and '' The Lark Ascending'' (1914). His vocal works include hymns, folk-song arrangements and large-scale choral pieces. He wrote eight works for stage performance between 1919 and 1951. Although none of his operas became popular repertoire pieces, his ballet '' Job: A Masque for Dancing'' (1930) was successful and has been frequently staged.

Two episodes made notably deep impressions in Vaughan Williams's personal life. The First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, in which he served in the army, had a lasting emotional effect. Twenty years later, though in his sixties and devotedly married, he was reinvigorated by a love affair with a much younger woman, who later became his second wife. He went on composing through his seventies and eighties, producing his last symphony months before his death at the age of eighty-five. His works have continued to be a staple of the British concert repertoire, and all his major compositions and many of the minor ones have been recorded.

Life and career

Early years

Vaughan Williams was born atDown Ampney

Down Ampney (pronounced ''Amney'') is a medium-sized village located in Cotswold district in Gloucestershire, in England. The population taken at the 2011 census was 644.

It is off the A417 which runs between Cirencester and Faringdon (in ...

, Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire ( abbreviated Glos) is a county in South West England. The county comprises part of the Cotswold Hills, part of the flat fertile valley of the River Severn and the entire Forest of Dean.

The county town is the city of Gl ...

, the third child and younger son of the vicar

A vicar (; Latin: '' vicarius'') is a representative, deputy or substitute; anyone acting "in the person of" or agent for a superior (compare "vicarious" in the sense of "at second hand"). Linguistically, ''vicar'' is cognate with the English pre ...

, the Reverend Arthur Vaughan Williams (1834–1875), and his wife, Margaret, ''née'' Wedgwood (1842–1937).Frogley, Alain"Williams, Ralph Vaughan (1872–1958)"

, ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, retrieved 10 October 2015 His paternal forebears were of mixed English and Welsh descent; many of them went into the law or the

Church

Church may refer to:

Religion

* Church (building), a building for Christian religious activities

* Church (congregation), a local congregation of a Christian denomination

* Church service, a formalized period of Christian communal worship

* C ...

. The judges Sir Edward and Sir Roland Vaughan Williams were respectively Arthur's father and brother. Margaret Vaughan Williams was a great-granddaughter of Josiah Wedgwood

Josiah Wedgwood (12 July 1730 – 3 January 1795) was an English potter, entrepreneur and abolitionist. Founding the Wedgwood company in 1759, he developed improved pottery bodies by systematic experimentation, and was the leader in the indus ...

and niece of Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

.

Arthur Vaughan Williams died suddenly in February 1875, and his widow took the children to live in her family home, Leith Hill Place,

Arthur Vaughan Williams died suddenly in February 1875, and his widow took the children to live in her family home, Leith Hill Place, Wotton, Surrey

Wotton is a well-wooded parish with one main settlement, a small village mostly south of the A25 between Guildford in the west and Dorking in the east. The nearest village with a small number of shops is Westcott. Wotton lies in a narrow va ...

. The children were under the care of a nurse, Sara Wager, who instilled in them not only polite manners and good behaviour but also liberal social and philosophical opinions. Such views were consistent with the progressive-minded tradition of both sides of the family. When the young Vaughan Williams asked his mother about Darwin's controversial book ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life''),The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by Me ...

'', she answered, "The Bible says that God made the world in six days. Great Uncle Charles thinks it took longer: but we need not worry about it, for it is equally wonderful either way".

In 1878, at the age of five, Vaughan Williams began receiving piano lessons from his aunt, Sophy Wedgwood. He displayed signs of musical talent early on, composing his first piece of music, a four-bar piano piece called "The Robin's Nest", in the same year. He did not greatly like the piano, and was pleased to begin violin lessons the following year.De Savage, pp. xvii–xxKennedy (1980), p. 11 In 1880, when he was eight, he took a correspondence course in music from Edinburgh University

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted ...

and passed the associated examinations.

In September 1883 he went as a boarder to Field House preparatory school in Rottingdean

Rottingdean is a village in the city of Brighton and Hove, on the south coast of England. It borders the villages of Saltdean, Ovingdean and Woodingdean, and has a historic centre, often the subject of picture postcards.

Name

The name Rotting ...

on the south coast of England, forty miles from Wotton. He was generally happy there, although he was shocked to encounter for the first time social snobbery and political conservatism, which were rife among his fellow pupils. From there he moved on to the public school Charterhouse

Charterhouse may refer to:

* Charterhouse (monastery), of the Carthusian religious order

Charterhouse may also refer to:

Places

* The Charterhouse, Coventry, a former monastery

* Charterhouse School, an English public school in Surrey

Londo ...

in January 1887. His academic and sporting achievements there were satisfactory, and the school encouraged his musical development. In 1888 he organised a concert in the school hall, which included a performance of his G major Piano Trio (now lost) with the composer as violinist.

While at Charterhouse Vaughan Williams found that religion meant less and less to him, and for a while he was an atheist. This softened into "a cheerful agnosticism", and he continued to attend church regularly to avoid upsetting the family. His views on religion did not affect his love of the Authorised Version of the Bible, the beauty of which, in the words of Ursula Vaughan Williams

Joan Ursula Penton Vaughan Williams (née Lock, formerly Wood; 15 March 1911 – 23 October 2007) was an English poet and author, and biographer of her second husband, the composer Ralph Vaughan Williams.

Biography

Born in Valletta, Malta, th ...

in her 1964 biography of the composer, remained "one of his essential companions through life."Vaughan Williams (1964), p. 29 In this, as in many other things in his life, he was, according to his biographer Michael Kennedy, "that extremely English product the natural nonconformist with a conservative regard for the best tradition".

Royal College of Music and Trinity College, Cambridge

alt=A man in late middle age, bald and moustached, up Hubert Parry, Vaughan Williams's first composition teacher at the Royal College of Music In July 1890 Vaughan Williams left Charterhouse and in September he was enrolled as a student at the Royal College of Music (RCM), London. After a compulsory course in harmony with Francis Edward Gladstone, professor of organ, counterpoint and harmony, he studied organ withWalter Parratt

Sir Walter Parratt (10 February 184127 March 1924) was an English organist and composer.

Biography

Born in Huddersfield, son of a parish organist, Parratt began to play the pipe organ from an early age, and held posts as an organist while sti ...

and composition with Hubert Parry

Sir Charles Hubert Hastings Parry, 1st Baronet (27 February 18487 October 1918) was an English composer, teacher and historian of music. Born in Richmond Hill in Bournemouth, Parry's first major works appeared in 1880. As a composer he is be ...

. He idolised Parry, and recalled in his ''Musical Autobiography'' (1950):

Vaughan Williams's family would have preferred him to have remained at Charterhouse for two more years and then go on to Cambridge University

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209 and granted a royal charter by Henry III of England, Henry III in 1231, Cambridge is the world' ...

. They were not convinced that he was talented enough to pursue a musical career, but feeling it would be wrong to prevent him from trying, they had allowed him to go to the RCM. Nevertheless, a university education was expected of him, and in 1892 he temporarily left the RCM and entered Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any college at either Cambridge or Oxford. ...

, where he spent three years, studying music and history.

Among those with whom Vaughan Williams became friendly at Cambridge were the philosophers G. E. Moore

George Edward Moore (4 November 1873 – 24 October 1958) was an English philosopher, who with Bertrand Russell, Ludwig Wittgenstein and earlier Gottlob Frege was among the founders of analytic philosophy. He and Russell led the turn from ideal ...

and Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British mathematician, philosopher, logician, and public intellectual. He had a considerable influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, linguistics, ...

, the historian G. M. Trevelyan

George Macaulay Trevelyan (16 February 1876 – 21 July 1962) was a British historian and academic. He was a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, from 1898 to 1903. He then spent more than twenty years as a full-time author. He returned to the ...

and the musician Hugh Allen. He felt intellectually overshadowed by some of his companions, but he learned much from them and formed lifelong friendships with several. Among the women with whom he mixed socially at Cambridge was Adeline Fisher, the daughter of Herbert Fisher, an old friend of the Vaughan Williams family. She and Vaughan Williams grew close, and in June 1897, after he had left Cambridge, they became engaged to be married.

alt=Man in late middle age, wearing pince-nez and a moustache, upleft, Charles Villiers Stanford, Vaughan Williams's second composition teacher at the RCM

During his time at Cambridge Vaughan Williams continued his weekly lessons with Parry, and studied composition with Charles Wood and organ with Alan Gray

Alan Gray (23 December 1855 – 27 September 1935) was an English organist and composer.

Life and career

Gray was born in into a well-known York family (the Grays of Grays Court). His father William Gray was a solicitor and (in 1844) Lord ...

. He graduated as Bachelor of Music

Bachelor of Music (BM or BMus) is an academic degree awarded by a college, university, or conservatory upon completion of a program of study in music. In the United States, it is a professional degree, and the majority of work consists of pre ...

in 1894 and Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four year ...

the following year. After leaving the university he returned to complete his training at the RCM. Parry had by then succeeded Sir George Grove as director of the college, and Vaughan Williams's new professor of composition was Charles Villiers Stanford

Sir Charles Villiers Stanford (30 September 1852 – 29 March 1924) was an Anglo-Irish composer, music teacher, and conductor of the late Romantic era. Born to a well-off and highly musical family in Dublin, Stanford was educated at the ...

. Relations between teacher and student were stormy but affectionate. Stanford, who had been adventurous in his younger days, had grown deeply conservative; he clashed vigorously with his modern-minded pupil. Vaughan Williams had no wish to follow in the traditions of Stanford's idols, Brahms

Johannes Brahms (; 7 May 1833 – 3 April 1897) was a German composer, pianist, and conductor of the mid-Romantic period. Born in Hamburg into a Lutheran family, he spent much of his professional life in Vienna. He is sometimes grouped with ...

and Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most op ...

, and he stood up to his teacher as few students dared to do. Beneath Stanford's severity lay a recognition of Vaughan Williams's talent and a desire to help the young man correct his opaque orchestration and extreme predilection for modal music.

In his second spell at the RCM (1895–1896) Vaughan Williams got to know a fellow student, Gustav Holst

Gustav Theodore Holst (born Gustavus Theodore von Holst; 21 September 1874 – 25 May 1934) was an English composer, arranger and teacher. Best known for his orchestral suite ''The Planets'', he composed many other works across a range ...

, who became a lifelong friend. Stanford emphasised the need for his students to be self-critical, but Vaughan Williams and Holst became, and remained, one another's most valued critics; each would play his latest composition to the other while still working on it. Vaughan Williams later observed, "What one really learns from an Academy or College is not so much from one's official teachers as from one's fellow-students ... e discussedevery subject under the sun from the lowest note of the double bassoon to the philosophy of ''Jude the Obscure

''Jude the Obscure'' is a novel by Thomas Hardy, which began as a magazine serial in December 1894 and was first published in book form in 1895 (though the title page says 1896). It is Hardy's last completed novel. The protagonist, Jude Fawley ...

''". In 1949 he wrote of their relationship, "Holst declared that his music was influenced by that of his friend: the converse is certainly true."

Early career

Vaughan Williams had a modest private income, which in his early career he supplemented with a variety of musical activities. Although the organ was not his preferred instrument, the only post he ever held for an annual salary was as a church organist and choirmaster. He held the position at St Barnabas, in the inner London district of South Lambeth, from 1895 to 1899 for a salary of £50 a year. He disliked the job, but working closely with a choir was valuable experience for his later undertakings.

Vaughan Williams had a modest private income, which in his early career he supplemented with a variety of musical activities. Although the organ was not his preferred instrument, the only post he ever held for an annual salary was as a church organist and choirmaster. He held the position at St Barnabas, in the inner London district of South Lambeth, from 1895 to 1899 for a salary of £50 a year. He disliked the job, but working closely with a choir was valuable experience for his later undertakings.

In October 1897 Adeline and Vaughan Williams were married. They honeymooned for several months in Berlin, where he studied with

In October 1897 Adeline and Vaughan Williams were married. They honeymooned for several months in Berlin, where he studied with Max Bruch

Max Bruch (6 January 1838 – 2 October 1920) was a German Romantic composer, violinist, teacher, and conductor who wrote more than 200 works, including three violin concertos, the first of which has become a prominent staple of the standard ...

. On their return they settled in London, originally in Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

and, from 1905, in Chelsea

Chelsea or Chelsey may refer to:

Places Australia

* Chelsea, Victoria

Canada

* Chelsea, Nova Scotia

* Chelsea, Quebec

United Kingdom

* Chelsea, London, an area of London, bounded to the south by the River Thames

** Chelsea (UK Parliament consti ...

. There were no children of the marriage.

In 1899 Vaughan Williams passed the examination for the degree of Doctor of Music at Cambridge; the title was formally conferred on him in 1901."Vaughan Williams, Ralph"''Who Was Who'', Oxford University Press, 2014, retrieved 10 October 2015 The song "Linden Lea" became the first of his works to appear in print, published in the magazine ''The Vocalist'' in April 1902 and then as separate sheet music. In addition to composition he occupied himself in several capacities during the first decade of the century. He wrote articles for musical journals and for the second edition of ''

Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians

''The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians'' is an encyclopedic dictionary of music and musicians. Along with the German-language ''Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart'', it is one of the largest reference works on the history and theo ...

'', edited the first volume of Purcell's ''Welcome Songs'' for the Purcell Society {{primary sources, date=March 2015

The Purcell Society, founded in 1876 (principally by William Hayman Cummings) is an organization dedicated to making the complete musical works of Henry Purcell available. Between 1876 and 1965, scores of all the ...

, and was for a while involved in adult education in the University Extension Lectures. From 1904 to 1906 he was music editor of a new hymn-book, ''The English Hymnal

''The English Hymnal'' is a hymn book which was published in 1906 for the Church of England by Oxford University Press. It was edited by the clergyman and writer Percy Dearmer and the composer and music historian Ralph Vaughan Williams, and wa ...

'', of which he later said, "I now know that two years of close association with some of the best (as well as some of the worst) tunes in the world was a better musical education than any amount of sonatas and fugues". Always committed to music-making for the whole community, he helped found the amateur Leith Hill Musical Festival in 1905, and was appointed its principal conductor, a post he held until 1953.

In 1903–1904 Vaughan Williams started collecting folk-songs. He had always been interested in them, and now followed the example of a recent generation of enthusiasts such as Cecil Sharp

Cecil James Sharp (22 November 1859 – 23 June 1924) was an English-born collector of folk songs, folk dances and instrumental music, as well as a lecturer, teacher, composer and musician. He was the pre-eminent activist in the development of t ...

and Lucy Broadwood

Lucy Etheldred Broadwood (9 August 1858 – 22 August 1929) was an English folksong collector and researcher, and great-granddaughter of John Broadwood, founder of the piano manufacturers Broadwood and Sons. As one of the founder members of the Fo ...

in going into the English countryside noting down and transcribing songs traditionally sung in various locations. Collections of the songs were published, preserving many that could otherwise have vanished as oral traditions died out. Vaughan Williams incorporated some into his own compositions, and more generally was influenced by their prevailing modal forms. This, together with his love of Tudor and Stuart music, helped shape his compositional style for the rest of his career.

Over this period Vaughan Williams composed steadily, producing songs, choral music, chamber works and orchestral pieces, gradually finding the beginnings of his mature style. His compositions included the tone poem

A symphonic poem or tone poem is a piece of orchestral music, usually in a single continuous movement, which illustrates or evokes the content of a poem, short story, novel, painting, landscape, or other (non-musical) source. The German term ''T ...

'' In the Fen Country'' (1904) and the '' Norfolk Rhapsody No. 1'' (1906). He remained unsatisfied with his technique as a composer. After unsuccessfully seeking lessons from Sir Edward Elgar

Sir Edward William Elgar, 1st Baronet, (; 2 June 1857 – 23 February 1934) was an English composer, many of whose works have entered the British and international classical concert repertoire. Among his best-known compositions are orchestr ...

,Adams (2013), p. 38 he contemplated studying with Vincent d'Indy

Paul Marie Théodore Vincent d'Indy (; 27 March 18512 December 1931) was a French composer and teacher. His influence as a teacher, in particular, was considerable. He was a co-founder of the Schola Cantorum de Paris and also taught at the P ...

in Paris. Instead, he was introduced by the critic and musicologist M.D.Calvocoressi to Maurice Ravel, a more modernist, less dogmatic musician than d'Indy.

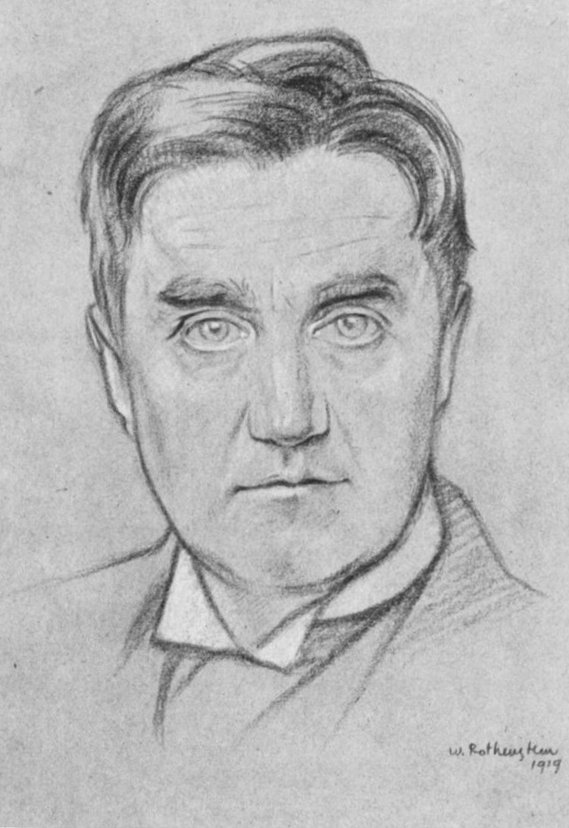

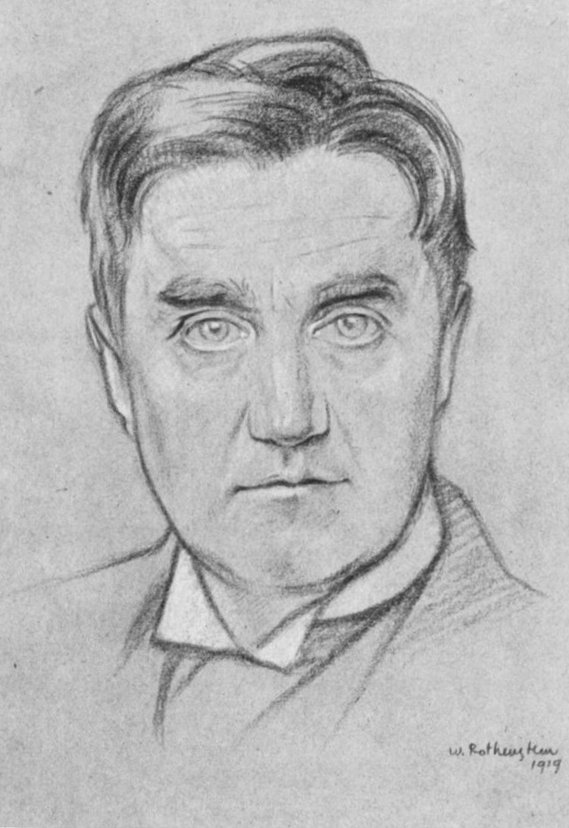

Ravel; rising fame; First World War

Ravel took few pupils, and was known as a demanding taskmaster for those he agreed to teach. Vaughan Williams spent three months in Paris in the winter of 1907–1908, working with him four or five times each week. There is little documentation of Vaughan Williams's time with Ravel; the musicologist Byron Adams advises caution in relying on Vaughan Williams's recollections in the ''Musical Autobiography'' written forty-three years after the event. The degree to which the French composer influenced the Englishman's style is debated. Ravel declared Vaughan Williams to be "my only pupil who does not write my music";Adams (2013), p. 40 nevertheless, commentators including Kennedy, Adams, Hugh Ottaway and Alain Frogley find Vaughan Williams's instrumental textures lighter and sharper in the music written after his return from Paris, such as the String Quartet in G minor, '' On Wenlock Edge'', the Overture to ''

Ravel took few pupils, and was known as a demanding taskmaster for those he agreed to teach. Vaughan Williams spent three months in Paris in the winter of 1907–1908, working with him four or five times each week. There is little documentation of Vaughan Williams's time with Ravel; the musicologist Byron Adams advises caution in relying on Vaughan Williams's recollections in the ''Musical Autobiography'' written forty-three years after the event. The degree to which the French composer influenced the Englishman's style is debated. Ravel declared Vaughan Williams to be "my only pupil who does not write my music";Adams (2013), p. 40 nevertheless, commentators including Kennedy, Adams, Hugh Ottaway and Alain Frogley find Vaughan Williams's instrumental textures lighter and sharper in the music written after his return from Paris, such as the String Quartet in G minor, '' On Wenlock Edge'', the Overture to ''The Wasps

''The Wasps'' ( grc-x-classical, Σφῆκες, translit=Sphēkes) is the fourth in chronological order of the eleven surviving plays by Aristophanes. It was produced at the Lenaia festival in 422 BC, during Athens' short-lived respite from the ...

'' and ''A Sea Symphony

''A Sea Symphony'' is an hour-long work for soprano, baritone, chorus and large orchestra written by Ralph Vaughan Williams between 1903 and 1909. The first and longest of his nine symphonies, it was first performed at the Leeds Festival in ...

''. Vaughan Williams himself said that Ravel had helped him escape from "the heavy contrapuntal Teutonic manner".

In the years between his return from Paris in 1908 and the outbreak of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in 1914, Vaughan Williams increasingly established himself as a figure in British music. For a rising composer it was important to receive performances at the big provincial music festivals, which generated publicity and royalties. In 1910 his music featured at two of the largest and most prestigious festivals, with the premieres of the ''Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis

''Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis'', also known as the ''Tallis Fantasia'', is a one-movement work for string orchestra by Ralph Vaughan Williams. The theme is by the 16th-century English composer Thomas Tallis. The Fantasia was first perf ...

'' at the Three Choirs Festival

200px, Worcester cathedral

200px, Gloucester cathedral

The Three Choirs Festival is a music festival held annually at the end of July, rotating among the cathedrals of the Three Counties (Hereford, Gloucester and Worcester) and originally featu ...

in Gloucester Cathedral in September and ''A Sea Symphony'' at the Leeds Festival

The Reading and Leeds Festivals are a pair of annual music festivals that take place in Reading and Leeds in England. The events take place simultaneously on the Friday, Saturday and Sunday of the August bank holiday weekend. The Reading Festiv ...

the following month."Music", ''The Times'', 7 September 1910, p. 11 The leading British music critics of the time, J. A. Fuller Maitland of ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' (f ...

'' and Samuel Langford

Samuel Langford (1863 - 8 May 1927) was an influential English music critic of the early twentieth century.

Trained as a pianist, Langford became chief music critic of ''The Manchester Guardian'' in 1906, serving in that post until his death. ...

of ''The Manchester Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'', were strong in their praise. The former wrote of the fantasia, "The work is wonderful because it seems to lift one into some unknown region of musical thought and feeling. Throughout its course one is never sure whether one is listening to something very old or very new". Langford declared that the symphony "definitely places a new figure in the first rank of our English composers". Between these successes and the start of war Vaughan Williams's largest-scale work was the first version of '' A London Symphony'' (1914). In the same year he wrote '' The Lark Ascending'' in its original form for violin and piano.

Despite his age—he was forty-two in 1914—Vaughan Williams volunteered for military service on the outbreak of the First World War. Joining the Royal Army Medical Corps as a private, he drove ambulance wagons in France and later in Greece. Frogley writes of this period that Vaughan Williams was considerably older than most of his comrades, and "the back-breaking labour of dangerous night-time journeys through mud and rain must have been more than usually punishing". The war left its emotional mark on Vaughan Williams, who lost many comrades and friends, including the young composer George Butterworth

George Sainton Kaye Butterworth, MC (12 July 18855 August 1916) was an English composer who was best known for the orchestral idyll '' The Banks of Green Willow'' and his song settings of A. E. Housman's poems from ''A Shropshire Lad''.

Early ...

. In 1917 Vaughan Williams was commissioned as a lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often ...

in the Royal Artillery

The Royal Regiment of Artillery, commonly referred to as the Royal Artillery (RA) and colloquially known as "The Gunners", is one of two regiments that make up the artillery arm of the British Army. The Royal Regiment of Artillery comprises t ...

, seeing action in France from March 1918. The continual noise of the guns damaged his hearing, and led to deafness in his later years. After the armistice in 1918 he served as director of music for the British First Army until demobilised in February 1919.

Inter-war years

During the war Vaughan Williams stopped writing music, and after returning to civilian life he took some time before feeling ready to compose new works. He revised some earlier pieces, and turned his attention to other musical activities. In 1919 he accepted an invitation from Hugh Allen, who had succeeded Parry as director, to teach composition at the RCM; he remained on the faculty of the college for the next twenty years. In 1921 he succeeded Allen as conductor of theBach Choir

The Bach Choir is a large independent musical organisation founded in London, England in 1876 to give the first performance of J. S. Bach's '' Mass in B minor'' in Britain.

The choir has around 240 active members. Directed by David Hill MBE ( Y ...

, London. It was not until 1922 that he produced a major new composition, '' A Pastoral Symphony''; the work was given its first performance in London in May conducted by Adrian Boult and its American premiere in June conducted by the composer.

Throughout the 1920s Vaughan Williams continued to compose, conduct and teach. Kennedy lists forty works premiered during the decade, including the Mass in G minor (1922), the ballet ''Old King Cole'' (1923), the operas '' Hugh the Drover'' and '' Sir John in Love'' (1924 and 1928), the suite ''Flos Campi

''Flos Campi'': suite for solo viola, small chorus and small orchestra is a composition by the English composer Ralph Vaughan Williams, completed in 1925. Its title is Latin for "flower of the field". It is neither a concerto nor a choral piec ...

'' (1925) and the oratorio ''Sancta Civitas

''Sancta Civitas'' (The Holy City) is an oratorio by Ralph Vaughan Williams. Written between 1923 and 1925, it was his first major work since the Mass in G minor two years previously. Vaughan Williams began working on the piece from a rented fur ...

'' (1925).

During the decade Adeline became increasingly immobilised by arthritis, and the numerous stairs in their London house finally caused the Vaughan Williamses to move in 1929 to a more manageable home, "The White Gates", Dorking, where they lived until Adeline's death in 1951. Vaughan Williams, who thought of himself as a complete Londoner, was sorry to leave the capital, but his wife was anxious to live in the country, and Dorking was within reasonably convenient reach of town.

In 1932 Vaughan Williams was elected president of the English Folk Dance and Song Society

The English Folk Dance and Song Society (EFDSS, or pronounced 'EFF-diss') is an organisation that promotes English folk music and folk dance. EFDSS was formed in 1932 when two organisations merged: the Folk-Song Society and the English Folk Dan ...

. From September to December of that year he was in the US as a visiting lecturer at Bryn Mawr College

Bryn Mawr College ( ; Welsh: ) is a women's liberal arts college in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania. Founded as a Quaker institution in 1885, Bryn Mawr is one of the Seven Sister colleges, a group of elite, historically women's colleges in the United ...

, Pennsylvania. The texts of his lectures were published under the title ''National Music'' in 1934; they sum up his artistic and social credo more fully than anything he had published previously, and remained in print for most of the remainder of the century.

During the 1930s Vaughan Williams came to be regarded as a leading figure in British music, particularly after the deaths of Elgar, Delius and Holst in 1934. Holst's death was a severe personal and professional blow to Vaughan Williams; the two had been each other's closest friends and musical advisers since their college days. After Holst's death Vaughan Williams was glad of the advice and support of other friends including Boult and the composer Gerald Finzi

Gerald Raphael Finzi (14 July 1901 – 27 September 1956) was a British composer. Finzi is best known as a choral composer, but also wrote in other genres. Large-scale compositions by Finzi include the cantata '' Dies natalis'' for solo voice and ...

, but his relationship with Holst was irreplaceable.

In some of Vaughan Williams's music of the 1930s there is an explicitly dark, even violent tone. The ballet '' Job: A Masque for Dancing'' (1930) and the Fourth Symphony (1935) surprised the public and critics. The discordant and violent tone of the symphony, written at a time of growing international tension, led many critics to suppose the symphony to be programmatic. Hubert Foss dubbed it "The Romantic" and Frank Howes

Frank Stewart Howes (2 April 1891 – 28 September 1974) was an English music critic. From 1943 to 1960 he was chief music critic of ''The Times''. From his student days Howes gravitated towards criticism as his musical specialism, guided by the a ...

called it "The Fascist".Schwartz. p. 74 The composer dismissed such interpretations, and insisted that the work was absolute music

Absolute music (sometimes abstract music) is music that is not explicitly 'about' anything; in contrast to program music, it is non- representational.M. C. Horowitz (ed.), ''New Dictionary of the History of Ideas'', , vol.1, p. 5 The idea of abs ...

, with no programme of any kind; nonetheless, some of those close to him, including Foss and Boult, remained convinced that something of the troubled spirit of the age was captured in the work.

As the decade progressed, Vaughan Williams found musical inspiration lacking, and experienced his first fallow period since his wartime musical silence. After his anti-war cantata ''Dona nobis pacem Dona nobis pacem (Latin for "Grant us peace") is a phrase in the Agnus Dei section of the mass. The phrase, in isolation, has been appropriated for a number of musical works, which include:

Classical music

* " Dona nobis pacem", a traditional ro ...

'' in 1936 he did not complete another work of substantial length until late in 1941, when the first version of the Fifth Symphony was completed.

In 1938 Vaughan Williams met Ursula Wood (1911–2007), the wife of an army officer, Captain (later Lieutenant-Colonel) Michael Forrester Wood. She was a poet, and had approached the composer with a proposed scenario for a ballet. Despite their both being married, and a four-decade age-gap, they fell in love almost from their first meeting; they maintained a secret love affair for more than a decade. Ursula became the composer's muse, helper and London companion, and later helped him care for his ailing wife. Whether Adeline knew, or suspected, that Ursula and Vaughan Williams were lovers is uncertain, but the relations between the two women were of warm friendship throughout the years they knew each other. The composer's concern for his first wife never faltered, according to Ursula, who admitted in the 1980s that she had been jealous of Adeline, whose place in Vaughan Williams's life and affections was unchallengeable.Neighbour, pp. 337–338 and 345

1939–1952

During the Second World War Vaughan Williams was active in civilian war work, chairing the Home Office Committee for the Release of Interned Alien Musicians, helpingMyra Hess

Dame Julia Myra Hess, (25 February 1890 – 25 November 1965) was an English pianist best known for her performances of the works of Bach, Mozart, Beethoven and Schumann.

Career Early life

Julia Myra Hess was born on 25 February 1890 to a J ...

with the organisation of the daily National Gallery

The National Gallery is an art museum in Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, in Central London, England. Founded in 1824, it houses a collection of over 2,300 paintings dating from the mid-13th century to 1900. The current Director ...

concerts, serving on a committee for refugees from Nazi oppression, and on the Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts (CEMA), the forerunner of the Arts Council. In 1940 he composed his first film score, for the propaganda film '' 49th Parallel''.

In 1942 Michael Wood died suddenly of heart failure. At Adeline's behest the widowed Ursula was invited to stay with the Vaughan Williamses in Dorking, and thereafter was a regular visitor there, sometimes staying for weeks at a time. The critic Michael White suggests that Adeline "appears, in the most amicable way, to have adopted Ursula as her successor".White, Michael"The merry widow"

, ''The Daily Telegraph'', 4 May 2002 Ursula recorded that during air raids all three slept in the same room in adjacent beds, holding hands for comfort.

Proms

The BBC Proms or Proms, formally named the Henry Wood Promenade Concerts Presented by the BBC, is an eight-week summer season of daily orchestral classical music concerts and other events held annually, predominantly in the Royal Albert Hal ...

. Its serene tone contrasted with the stormy Fourth, and led some commentators to think it a symphonic valediction. William Glock

Sir William Frederick Glock, CBE (3 May 190828 June 2000) was a British music critic and musical administrator who was instrumental in introducing the Continental avant-garde, notably promoting the career of Pierre Boulez.

Biography

Glock was bo ...

wrote that it was "like the work of a distinguished poet who has nothing very new to say, but says it in exquisitely flowing language". The music Vaughan Williams wrote for the BBC to celebrate the end of the war, ''Thanksgiving for Victory'', was marked by what the critic Edward Lockspeiser called the composer's characteristic avoidance of "any suggestion of rhetorical pompousness". Any suspicion that the septuagenarian composer had settled into benign tranquillity was dispelled by his Sixth Symphony (1948), described by the critic Gwyn Parry-Jones as "one of the most disturbing musical statements of the 20th century", opening with a "primal scream, plunging the listener immediately into a world of aggression and impending chaos." Coming as it did near the start of the Cold War, many critics thought its ''pianissimo'' last movement a depiction of a nuclear-scorched wasteland. The composer was dismissive of programmatic theories: "It never seems to occur to people that a man might just want to write a piece of music."Kennedy (1980), p. 302

In 1951 Adeline died, aged eighty. In the same year Vaughan Williams's last opera, ''The Pilgrim's Progress

''The Pilgrim's Progress from This World, to That Which Is to Come'' is a 1678 Christianity, Christian allegory written by John Bunyan. It is regarded as one of the most significant works of theological fiction in English literature and a prog ...

'', was staged at Covent Garden as part of the Festival of Britain

The Festival of Britain was a national exhibition and fair that reached millions of visitors throughout the United Kingdom in the summer of 1951. Historian Kenneth O. Morgan says the Festival was a "triumphant success" during which people:

...

. He had been working intermittently on a musical treatment of John Bunyan

John Bunyan (; baptised 30 November 162831 August 1688) was an English writer and Puritan preacher best remembered as the author of the Christian allegory ''The Pilgrim's Progress,'' which also became an influential literary model. In addition ...

's allegory for forty-five years, and the 1951 "morality" was the final result. The reviews were respectful, but the work did not catch the opera-going public's imagination, and the Royal Opera House's production was "insultingly half-hearted" according to Frogley. The piece was revived the following year, but was still not a great success. Vaughan Williams commented to Ursula, "They don't like it, they won't like it, they don't want an opera with no heroine and no love duets—and I don't care, it's what I meant, and there it is."

Second marriage and last years

In February 1953 Vaughan Williams and Ursula were married. He left the Dorking house and they took a lease of 10Hanover Terrace

Hanover Terrace overlooks Regent's Park in City of Westminster, London, England. The terrace is a Grade I listed building.

History

It was designed by John Nash in 1822. It has a centre and two wing buildings, of the Doric order, the acroterion, ...

, Regent's Park

Regent's Park (officially The Regent's Park) is one of the Royal Parks of London. It occupies of high ground in north-west Inner London, administratively split between the City of Westminster and the Borough of Camden (and historically betwee ...

, London. It was the year of Queen Elizabeth II's coronation; Vaughan Williams's contribution was an arrangement of the Old Hundredth

"Old 100th" or "Old Hundredth" (also known as "Old Hundred") is a hymn tune in long metre, from the second edition of the Genevan Psalter. It is one of the best known melodies in many occidental Christian musical traditions. The tune is usually ...

psalm tune, and a new setting of "O taste and see" from Psalm 34

Psalm 34 is the 34th psalm of the Book of Psalms, beginning in English in the King James Version: "I will bless the LORD at all times: his praise shall continually be in my mouth." The Book of Psalms is part of the third section of the Hebrew B ...

, performed at the service in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the Unite ...

.

Having returned to live in London, Vaughan Williams, with Ursula's encouragement, became much more active socially and in '' pro bono publico'' activities. He was a leading figure in the Society for the Promotion of New Music, and in 1954 he set up and endowed the RVW Trust to support young composers and promote new or neglected music. He and his wife travelled extensively in Europe, and in 1954 he visited the US once again, having been invited to lecture at

Having returned to live in London, Vaughan Williams, with Ursula's encouragement, became much more active socially and in '' pro bono publico'' activities. He was a leading figure in the Society for the Promotion of New Music, and in 1954 he set up and endowed the RVW Trust to support young composers and promote new or neglected music. He and his wife travelled extensively in Europe, and in 1954 he visited the US once again, having been invited to lecture at Cornell

Cornell University is a private statutory land-grant research university based in Ithaca, New York. It is a member of the Ivy League. Founded in 1865 by Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, Cornell was founded with the intention to teach a ...

and other universities and to conduct. He received an enthusiastic welcome from large audiences, and was overwhelmed at the warmth of his reception. Kennedy describes it as "like a musical state occasion".

Of Vaughan Williams's works from the 1950s, ''Grove'' makes particular mention of '' Three Shakespeare Songs'' (1951) for unaccompanied chorus, the Christmas cantata ''Hodie

''Hodie'' (''This Day'') is a cantata by Ralph Vaughan Williams. Composed between 1953 and 1954, it is the composer's last major choral-orchestral composition, and was premiered under his baton at Worcester Cathedral, as part of the Three Choi ...

'' (1953–1954), the Violin Sonata, and, most particularly, the '' Ten Blake Songs'' (1957) for voice and oboe, "a masterpiece of economy and precision". Unfinished works from the decade were a cello concerto and a new opera, ''Thomas the Rhymer''. The predominant works of the 1950s were his three last symphonies. The seventh—officially unnumbered, and titled ''Sinfonia antartica

''Sinfonia antartica'' ("Antarctic Symphony") is the Italian title given by Ralph Vaughan Williams to his seventh symphony, first performed in 1953. It drew on incidental music the composer had written for the 1948 film ''Scott of the Antarctic' ...

''—divided opinion; the score is a reworking of music Vaughan Williams had written for the 1948 film '' Scott of the Antarctic'', and some critics thought it not truly symphonic. The Eighth, though wistful in parts, is predominantly lighthearted in tone; it was received enthusiastically at its premiere in 1956, given by the Hallé Orchestra under the dedicatee, Sir John Barbirolli

Sir John Barbirolli ( Giovanni Battista Barbirolli; 2 December 189929 July 1970) was a British conductor and cellist. He is remembered above all as conductor of the Hallé Orchestra in Manchester, which he helped save from dissolution in 194 ...

. The Ninth, premiered at a Royal Philharmonic Society

The Royal Philharmonic Society (RPS) is a British music society, formed in 1813. Its original purpose was to promote performances of instrumental music in London. Many composers and performers have taken part in its concerts. It is now a memb ...

concert conducted by Sir Malcolm Sargent in April 1958, puzzled critics with its sombre, questing tone, and did not immediately achieve the recognition it later gained.

Having been in excellent health, Vaughan Williams died suddenly in the early hours of 26 August 1958 at Hanover Terrace, aged 85. Two days later, after a private funeral at Golders Green

Golders Green is an area in the London Borough of Barnet in England. A smaller suburban linear settlement, near a farm and public grazing area green of medieval origins, dates to the early 19th century. Its bulk forms a late 19th century and ea ...

, he was cremated. On 19 September, at a crowded memorial service, his ashes were interred near the burial plots of Purcell and Stanford in the north choir aisle of Westminster Abbey.

Music

Michael Kennedy characterises Vaughan Williams's music as a strongly individual blending of the modal harmonies familiar from folk‐song with the French influence of Ravel and Debussy. The basis of his work is melody, his rhythms, in Kennedy's view, being unsubtle at times.Kennedy, Michael (ed)"Vaughan Williams, Ralph"

''The Oxford Dictionary of Music'', 2nd edition, Oxford University Press, retrieved 10 October 2015 Vaughan Williams's music is often described as visionary; Kennedy cites the masque ''Job'' and the Fifth and Ninth Symphonies. Vaughan Williams's output was prolific and wide-ranging. For the voice he composed songs, operas, and choral works ranging from simpler pieces suitable for amateurs to demanding works for professional choruses. His comparatively few chamber works are not among his better-known compositions. Some of his finest works elude conventional categorisation, such as the '' Serenade to Music'' (1938) for sixteen solo singers and orchestra; ''Flos Campi'' (1925) for solo viola, small orchestra, and small chorus; and his most important chamber work, in Howes's view—not purely instrumental but a song cycle—''On Wenlock Edge'' (1909) with accompaniment for string quartet and piano. In 1955 the authors of ''The Record Guide'', Edward Sackville-West and Desmond Shawe-Taylor, wrote that Vaughan Williams's music showed an exceptionally strong individual voice: Vaughan Williams's style is "not remarkable for grace or politeness or inventive colour", but expresses "a consistent vision in which thought and feeling and their equivalent images in music never fall below a certain high level of natural distinction". They commented that the composer's vision is expressed in two main contrasting moods: "the one contemplative and trance-like, the other pugnacious and sinister". The first mood, generally predominant in the composer's output, was more popular, as audiences preferred "the stained-glass beauty of the Tallis Fantasia, the direct melodic appeal of the ''Serenade to Music'', the pastoral poetry of ''The Lark Ascending'', and the grave serenity of the Fifth Symphony". By contrast, as in the ferocity of the Fourth and Sixth Symphonies and the Concerto for Two Pianos: "in his grimmer moods Vaughan Williams can be as frightening as Sibelius and Bartók".

Symphonies

It is as a symphonist that Vaughan Williams is best known. The composer and academicElliott Schwartz

Elliott Shelling Schwartz (January 19, 1936 – December 7, 2016) was an American composer. A graduate of Columbia University, he was Beckwith Professor Emeritus of music at Bowdoin College joining the faculty in 1964. In 2006, the Library of ...

wrote (1964), "It may be said with truth that Vaughan Williams, Sibelius

Jean Sibelius ( ; ; born Johan Julius Christian Sibelius; 8 December 186520 September 1957) was a Finnish composer of the late Romantic and early-modern periods. He is widely regarded as his country's greatest composer, and his music is often ...

and Prokofieff are the symphonists of this century".Schwartz, p. 201 Although Vaughan Williams did not complete the first of them until he was thirty-eight years old, the nine symphonies span nearly half a century of his creative life. In his 1964 analysis of the nine, Schwartz found it striking that no two of the symphonies are alike, either in structure or in mood. Commentators have found it useful to consider the nine in three groups of three—early, middle and late.

''Sea'', ''London'' and ''Pastoral'' Symphonies (1910–1922)

The first three symphonies, to which Vaughan Williams assigned titles rather than numbers, form a sub-group within the nine, having programmatic elements absent from the later six.Schwartz, p. 18 ''A Sea Symphony

''A Sea Symphony'' is an hour-long work for soprano, baritone, chorus and large orchestra written by Ralph Vaughan Williams between 1903 and 1909. The first and longest of his nine symphonies, it was first performed at the Leeds Festival in ...

'' (1910), the only one of the series to include a part for full choir, differs from most earlier choral symphonies

A choir ( ; also known as a chorale or chorus) is a musical ensemble of singers. Choral music, in turn, is the music written specifically for such an ensemble to perform. Choirs may perform music from the classical music repertoire, which ...

in that the choir sings in all the movements. The extent to which it is a true symphony has been debated; in a 2013 study, Alain Frogley describes it as a hybrid work, with elements of symphony, oratorio and cantata.Frogley, p. 93 Its sheer length—about eighty minutes—was unprecedented for an English symphonic work, and within its thoroughly tonal construction it contains harmonic dissonances that pre-echo the early works of Stravinsky which were soon to follow.

'' A London Symphony'' (1911–1913) which the composer later observed might more accurately be called a "symphony by a Londoner", is for the most part not overtly pictorial in its presentation of London. Vaughan Williams insisted that it is "self-expressive, and must stand or fall as 'absolute' music". There are some references to the urban soundscape: brief impressions of street music, with the sound of the barrel organ

A barrel organ (also called roller organ or crank organ) is a French mechanical musical instrument consisting of bellows and one or more ranks of pipes housed in a case, usually of wood, and often highly decorated. The basic principle is the sam ...

mimicked by the orchestra; the characteristic chant of the lavender-seller; the jingle of hansom cab

The hansom cab is a kind of horse-drawn carriage designed and patented in 1834 by Joseph Hansom, an architect from York. The vehicle was developed and tested by Hansom in Hinckley, Leicestershire, England. Originally called the Hansom safety ca ...

s; and the chimes of Big Ben played by harp and clarinet. But commentators have heard—and the composer never denied or confirmed—some social comment in sinister echoes at the end of the scherzo and an orchestral outburst of pain and despair at the opening of the finale. Schwartz comments that the symphony, in its "unified presentation of widely heterogeneous elements", is "very much like the city itself". Vaughan Williams said in his later years that this was his favourite of the symphonies.

The last of the first group is '' A Pastoral Symphony'' (1921). The first three movements are for orchestra alone; a wordless solo soprano or tenor voice is added in the finale. Despite the title the symphony draws little on the folk-songs beloved of the composer, and the pastoral landscape evoked is not a tranquil English scene, but the French countryside ravaged by war. Some English musicians who had not fought in the First World War misunderstood the work and heard only the slow tempi and quiet tone, failing to notice the character of a requiem in the music and mistaking the piece for a rustic idyll. Kennedy comments that it was not until after the Second World War that "the spectral 'Last Post' in the second movement and the girl's lamenting voice in the finale" were widely noticed and understood.

Symphonies 4–6 (1935–1948)

The middle three symphonies are purely orchestral, and generally conventional in form, withsonata form

Sonata form (also ''sonata-allegro form'' or ''first movement form'') is a musical structure generally consisting of three main sections: an exposition, a development, and a recapitulation. It has been used widely since the middle of the 18th c ...

(modified in places), specified home keys, and four-movement structure. The orchestral forces required are not large by the standards of the first half of the 20th century, although the Fourth calls for an augmented woodwind section and the Sixth includes a part for tenor saxophone

The tenor saxophone is a medium-sized member of the saxophone family, a group of instruments invented by Adolphe Sax in the 1840s. The tenor and the alto are the two most commonly used saxophones. The tenor is pitched in the key of B (while ...

. The Fourth Symphony (1935) astonished listeners with its striking dissonance, far removed from the prevailing quiet tone of the previous symphony. The composer firmly contradicted any notions that the work was programmatical in any respect, and Kennedy calls attempts to give the work "a meretricious programme ... a poor compliment to its musical vitality and self-sufficiency".

The Fifth Symphony (1943) was in complete contrast to its predecessor. Vaughan Williams had been working on and off for many years on his operatic version of Bunyan's ''The Pilgrim's Progress''. Fearing—wrongly as it turned out—that the opera would never be completed, Vaughan Williams reworked some of the music already written for it into a new symphony. Despite the internal tensions caused by the deliberate conflict of modality in places, the work is generally serene in character, and was particularly well received for the comfort it gave at a time of all-out war. Neville Cardus

Sir John Frederick Neville Cardus, Commander of the Order of the British Empire, CBE (2 April 188828 February 1975) was an English writer and critic. From an impoverished home background, and mainly self-educated, he became ''The Manchester Gua ...

later wrote, "The Fifth Symphony contains the most benedictory and consoling music of our time."

With the Sixth Symphony (1948) Vaughan Williams once again confounded expectations. Many had seen the Fifth, composed when he was seventy, as a valedictory work, and the turbulent, troubled Sixth came as a shock. After violent orchestral clashes in the first movement, the obsessive '' ostinato'' of the second and the "diabolic" scherzo, the finale perplexed many listeners. Described as "one of the strangest journeys ever undertaken in music", it is marked ''pianissimo'' throughout its 10–12-minute duration.

''Sinfonia antartica'', Symphonies 8 and 9 (1952–1957)

The seventh symphony, the ''Sinfonia antartica

''Sinfonia antartica'' ("Antarctic Symphony") is the Italian title given by Ralph Vaughan Williams to his seventh symphony, first performed in 1953. It drew on incidental music the composer had written for the 1948 film ''Scott of the Antarctic' ...

'' (1952), a by-product of the composer's score for ''Scott of the Antarctic'', has consistently divided critical opinion on whether it can be properly classed as a symphony.Schwartz, p. 135 Alain Frogley in ''Grove'' argues that though the work can make a deep impression on the listener, it is neither a true symphony in the understood sense of the term nor a tone poem and is consequently the least successful of the mature symphonies. The work is in five movements, with wordless vocal lines for female chorus and solo soprano in the first and last movements.Ottaway, Hugh and Alain Frogley"Vaughan Williams, Ralph"

''Grove Music Online'', Oxford University Press, retrieved 10 October 2015 In addition to large woodwind and percussion sections the score features a prominent part for

wind machine

The wind machine (also called an aeoliphone or aelophon) is a friction idiophone used to produce the sound of wind for orchestral compositions and musical theater productions.

Construction

The wind machine is constructed of a large cyli ...

.

The Eighth Symphony (1956) in D minor is noticeably different from its seven predecessors by virtue of its brevity and, despite its minor key, its general light-heartedness. The orchestra is smaller than for most of the symphonies, with the exception of the percussion section, which is particularly large, with, as Vaughan Williams put it, "all the 'phones' and 'spiels' known to the composer".Kennedy (2013), p. 293 The work was enthusiastically received at its early performances, and has remained among Vaughan Williams's most popular works.

The final symphony, the Ninth, was completed in late 1957 and premiered in April 1958, four months before the composer's death. It is scored for a large orchestra, including three saxophones, a flugelhorn, and an enlarged percussion section. The mood is more sombre than that of the Eighth; ''Grove'' calls its mood "at once heroic and contemplative, defiant and wistfully absorbed". The work received an ovation at its premiere, but at first the critics were not sure what to make of it, and it took some years for it to be generally ranked alongside its eight predecessors.

Other orchestral music

''Grove'' lists more than thirty works by Vaughan Williams for orchestra or band over and above the symphonies. They include two of his most popular works—the ''

''Grove'' lists more than thirty works by Vaughan Williams for orchestra or band over and above the symphonies. They include two of his most popular works—the ''Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis

''Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis'', also known as the ''Tallis Fantasia'', is a one-movement work for string orchestra by Ralph Vaughan Williams. The theme is by the 16th-century English composer Thomas Tallis. The Fantasia was first perf ...

'' (1910, revised 1919), and '' The Lark Ascending'', originally for violin and piano (1914); orchestrated 1920. Other works that survive in the repertoire in Britain are the ''Norfolk Rhapsody No 1'' (1905–1906), ''The Wasps, Aristophanic suite''—particularly the overture (1909), the '' English Folk Song Suite'' (1923) and the ''Fantasia on Greensleeves'' (1934).

Vaughan Williams wrote four concertos: for violin (1925), piano

The piano is a stringed keyboard instrument in which the strings are struck by wooden hammers that are coated with a softer material (modern hammers are covered with dense wool felt; some early pianos used leather). It is played using a keybo ...

(1926), oboe

The oboe ( ) is a type of double reed woodwind instrument. Oboes are usually made of wood, but may also be made of synthetic materials, such as plastic, resin, or hybrid composites. The most common oboe plays in the treble or soprano range.

...

(1944) and tuba

The tuba (; ) is the lowest-pitched musical instrument in the brass family. As with all brass instruments, the sound is produced by lip vibrationa buzzinto a mouthpiece. It first appeared in the mid-19th century, making it one of the ne ...

(1954); another concertante piece is his Romance for harmonica, strings and piano (1951). None of these works has rivalled the popularity of the symphonies or the short orchestral works mentioned above. Bartók was among the admirers of the Piano Concerto, written for and championed by Harriet Cohen

Harriet(t) may refer to:

* Harriet (name), a female name ''(includes list of people with the name)''

Places

* Harriet, Queensland, rural locality in Australia

* Harriet, Arkansas, unincorporated community in the United States

* Harriett, Texas, ...

, but it has remained, in the words of the critic Andrew Achenbach, a neglected masterpiece.

In addition to the music for ''Scott of the Antarctic'', Vaughan Williams composed incidental music for eleven other films, from ''49th Parallel'' (1941) to ''The Vision of William Blake'' (1957).

Chamber and instrumental

By comparison with his output in other genres, Vaughan Williams's music for chamber ensembles and solo instruments forms a small part of his oeuvre. ''Grove'' lists twenty-four pieces under the heading "Chamber and instrumental"; three are early, unpublished works. Vaughan Williams, like most leading British 20th-century composers, was not drawn to the solo piano and wrote little for it. From his mature years, there survive for standard chamber groupings two string quartets (1908–1909, revised 1921; and 1943–1944), a "phantasy" string quintet (1912), and a sonata for violin and piano (1954). The first quartet was written soon after Vaughan Williams's studies in Paris with Ravel, whose influence is strongly evident. In 2002 the magazine '' Gramophone'' described the second quartet as a masterpiece that should be, but is not, part of the international chamber repertory. It is from the same period as the Sixth Symphony, and has something of that work's severity and anguish. The quintet (1912) was written two years after the success of the ''Tallis Fantasia'', with which it has elements in common, both in terms of instrumental layout and the mood of rapt contemplation. The violin sonata has made little impact.Vocal music

Ursula Vaughan Williams wrote of her husband's love of literature, and listed some of his favourite writers and writings: In addition to his love of poetry, Vaughan Williams's vocal music is inspired by his lifelong belief that the voice "can be made the medium of the best and deepest human emotion."Songs

Between the mid-1890s and the late 1950s Vaughan Williams set more than eighty poems for voice and piano accompaniment. The earliest to survive is "A Cradle Song", toColeridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who, with his friend William Wordsworth, was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lake ...

's words, from about 1894. The songs include many that have entered the repertory, such as "Linden Lea" (1902), "Silent Noon" (1904) and the song cycles ''Songs of Travel