Rack (torture device) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The rack is a

The rack is a

In Russia up to the 18th century the rack (''дыба'', dyba) was a

In Russia up to the 18th century the rack (''дыба'', dyba) was a

О России, в царствование Алексея Михайловича. Современное сочинение Григория Котошихина.

— СПб.: Археографическая комиссия, 1859.

The term rack is also used, occasionally, for a number of simpler constructions that merely facilitate corporal punishment, after which it may be named specifically, e.g., '' caning rack'', as in a given jurisdiction it was often the custom to administer any given punishment in a specific position, for which the device (with or without fitting shackling and/or padding) would be chosen or specially made.

Several devices similar in principle to the rack have been used through the ages. One of these was the Wooden Horse, a device used to torture prisoners during the Roman Empire by stretching them on top of a tall wooden frame until the shoulders were dislocated followed by a violent drop into a hanging position and beating. In another variant used primarily in ancient times, the victim's feet were affixed to the ground and his/her hands were chained to a wheel. When the wheel was turned, the person was stretched in a manner similar to the rack. The ''Austrian ladder'' was basically a more vertically oriented rack. As part of the torture, victims would usually be burned under the arms with candles.

The term rack is also used, occasionally, for a number of simpler constructions that merely facilitate corporal punishment, after which it may be named specifically, e.g., '' caning rack'', as in a given jurisdiction it was often the custom to administer any given punishment in a specific position, for which the device (with or without fitting shackling and/or padding) would be chosen or specially made.

Several devices similar in principle to the rack have been used through the ages. One of these was the Wooden Horse, a device used to torture prisoners during the Roman Empire by stretching them on top of a tall wooden frame until the shoulders were dislocated followed by a violent drop into a hanging position and beating. In another variant used primarily in ancient times, the victim's feet were affixed to the ground and his/her hands were chained to a wheel. When the wheel was turned, the person was stretched in a manner similar to the rack. The ''Austrian ladder'' was basically a more vertically oriented rack. As part of the torture, victims would usually be burned under the arms with candles.

The rack is a

The rack is a torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons such as punishment, extracting a confession, interrogational torture, interrogation for information, or intimidating third parties. definitions of tortur ...

device consisting of a rectangular, usually wooden frame, slightly raised from the ground, with a roller at one or both ends. The victim's ankles are fastened to one roller and the wrists are chained to the other. As the interrogation progresses, a handle and ratchet mechanism attached to the top roller are used to very gradually retract the chains, slowly increasing the strain on the prisoner's shoulders, hips, knees, and elbows and causing excruciating pain. By means of pulleys and lever

A lever is a simple machine consisting of a beam or rigid rod pivoted at a fixed hinge, or '' fulcrum''. A lever is a rigid body capable of rotating on a point on itself. On the basis of the locations of fulcrum, load and effort, the lever is d ...

s, this roller could be rotated on its own axis, thus straining the ropes until the sufferer's joint

A joint or articulation (or articular surface) is the connection made between bones, ossicles, or other hard structures in the body which link an animal's skeletal system into a functional whole.Saladin, Ken. Anatomy & Physiology. 7th ed. McGraw- ...

s were dislocated

A joint dislocation, also called luxation, occurs when there is an abnormal separation in the joint, where two or more bones meet.Dislocations. Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital at Stanford. Retrieved 3 March 2013 A partial dislocation is refe ...

and eventually separated. Additionally, if muscle fibre

A muscle cell is also known as a myocyte when referring to either a cardiac muscle cell (cardiomyocyte), or a smooth muscle cell as these are both small cells. A skeletal muscle cell is long and threadlike with many nuclei and is called a muscle ...

s are stretched excessively, they lose their ability to contract

A contract is a legally enforceable agreement between two or more parties that creates, defines, and governs mutual rights and obligations between them. A contract typically involves the transfer of goods, services, money, or a promise to tr ...

, rendering them ineffective.

One gruesome aspect of being stretched too far on the rack is the loud popping noises made by snapping cartilage, ligaments or bone

A bone is a rigid organ that constitutes part of the skeleton in most vertebrate animals. Bones protect the various other organs of the body, produce red and white blood cells, store minerals, provide structure and support for the body, ...

s. Another method for putting pressure upon prisoners was to force them to watch someone else being subjected to the rack. Confining the prisoner on the rack enabled further tortures to be simultaneously applied, typically including burning the flanks with hot torches or candles or using "pincers made with specially roughened grips to tear out the nails of the fingers and toes" or sliding thin slivers of red-hot coal between pairs of adjacent toes. Usually, the victim's shoulders and hips would be separated and their elbows, knees, wrists, and ankles would be dislocated.

Uses

Early use

The rack was first used in antiquity and it is unclear exactly from which civilization it originated, though some of the earliest examples are from Greece. The Greeks may have first used the rack as a means of torturing slaves and non-citizens, and later in special cases, as in 356 BC, when it was applied to gain a confession fromHerostratus

Herostratus ( grc, Ἡρόστρατος) was a 4th-century BC Greek, accused of seeking notoriety as an arsonist by destroying the second Temple of Artemis in Ephesus (on the outskirts of present-day Selçuk). The conclusion prompted the creat ...

, who was later executed for burning down the Temple of Artemis

The Temple of Artemis or Artemision ( gr, Ἀρτεμίσιον; tr, Artemis Tapınağı), also known as the Temple of Diana, was a Greek temple dedicated to an ancient, local form of the goddess Artemis (identified with Diana, a Roman go ...

at Ephesus, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World

The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, also known as the Seven Wonders of the World or simply the Seven Wonders, is a list of seven notable structures present during classical antiquity. The first known list of seven wonders dates back to the 2 ...

. Arrian's ''Anabasis of Alexander

''The Anabasis of Alexander'' ( grc-gre, Ἀλεξάνδρου Ἀνάβασις, ''Alexándrou Anábasis''; la, Anabasis Alexandri) was composed by Arrian of Nicomedia in the second century AD, most probably during the reign of Hadrian. T ...

'' states that Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

had the pages who conspired to assassinate him, along with their mentor, his court historian Callisthenes

Callisthenes of Olynthus (; grc-gre, Καλλισθένης; 360327 BCE) was a well-connected Greek historian in Macedon, who accompanied Alexander the Great during his Asiatic expedition. The philosopher Aristotle was Callisthenes's great ...

, tortured on the rack in 328 BC.

According to Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his two major works—the ...

, the rack was used in a vain attempt to extract the names of the conspirators to assassinate Emperor Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68), was the fifth Roman emperor and final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 unt ...

in the Pisonian conspiracy

The conspiracy of Gaius Calpurnius Piso in AD 65 was a in the reign of the Roman emperor Nero (reign 54–68). The plot reflected the growing discontent among the ruling class of the Roman state with Nero's increasingly despotic leadership, a ...

from the freedwoman Epicharis in 65 A.D. The next day, after refusing to talk, she was dragged back to the rack on a chair (all of her limbs were dislocated

A joint dislocation, also called luxation, occurs when there is an abnormal separation in the joint, where two or more bones meet.Dislocations. Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital at Stanford. Retrieved 3 March 2013 A partial dislocation is refe ...

, so she could not stand), but strangled herself on a loop of cord on the back of the chair on the way. The rack, in Roman sources, was referred to with the name ''equuleus''; the word ''fidicula'', more commonly the name of a small lyre or stringed instrument, was used to describe a similar torture device, although its exact design has been lost.

The rack was also used on early Christians, such as St. Vincent (304 A.D.), and mentioned by the Church Fathers Tertullian

Tertullian (; la, Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullianus; 155 AD – 220 AD) was a prolific early Christian author from Carthage in the Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive corpus of L ...

and St. Jerome

Jerome (; la, Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος Σωφρόνιος Ἱερώνυμος; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was a Christian priest, confessor, theologian, and historian; he is com ...

(420 A.D.).

Britain

Its first appearance in England is said to have been due toJohn Holland, 2nd Duke of Exeter

John Holland, 2nd Duke of Exeter, 2nd Earl of Huntingdon, (29 March 1395 – 5 August 1447) was an English nobleman and military commander during the Hundred Years' War. His father, the 1st Duke of Exeter, was a maternal half-brother to Ri ...

, the constable of the Tower

The Constable of the Tower is the most senior appointment at the Tower of London. In the Middle Ages a constable was the person in charge of a castle when the owner—the king or a nobleman—was not in residence. The Constable of the Tower had a ...

in 1447, and was thus popularly known as "the Duke of Exeter's daughter".

The Protestant martyr Anne Askew

Anne Askew (sometimes spelled Ayscough or Ascue) married name Anne Kyme, (152116 July 1546) was an English writer, poet, and Anabaptist preacher who was condemned as a heretic during the reign of Henry VIII of England. She and Margaret Cheyne ...

, Daughter of Sir William Askew, Knight of Lincolnshire, was tortured on the rack before her execution in 1546 (age 25). She was well known for studying the Bible and memorizing verses; she remained apparently true to her beliefs even up to her execution. So damaged by the torture on the rack she had to be carried on a chair to her burning at the stake. The accusations against her were from: (1) the Bishop's Chancellor, who claimed that women were not allowed to speak the Scriptures, and (2) the Bishop of Winchester, because she would not profess that the sacraments were the literal flesh, blood and bone of Christ; this despite the fact that the English Reformation had already begun a decade earlier.

The Catholic martyr Nicholas Owen, a noted builder of priest hole

A priest hole is a hiding place for a priest built into many of the principal Catholic houses of England, Wales and Ireland during the period when Catholics were persecuted by law. When Queen Elizabeth I came to the throne in 1558, there were se ...

s, died under torture on the rack in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

in 1606. Guy Fawkes

Guy Fawkes (; 13 April 1570 – 31 January 1606), also known as Guido Fawkes while fighting for the Spanish, was a member of a group of provincial English Catholics involved in the failed Gunpowder Plot of 1605. He was born and educated ...

is also thought to have been put to the rack, since a royal warrant authorising his torture survives. The warrant states that "lesser tortures" should be applied to him at first, but if he remained recalcitrant he could be racked.

In 1615 a clergyman called Edmond Peacham, accused of high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

, was racked.

In 1628 the question of its legality was raised in connection with a proposal in the Privy Council to rack John Felton, the assassin of George Villiers, the 1st Duke of Buckingham. The judges resisted this, unanimously declaring its use to be contrary to the laws of England. The previous year Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

had authorised the Irish Courts to rack a Catholic priest

The priesthood is the office of the ministers of religion, who have been commissioned ("ordained") with the Holy orders of the Catholic Church. Technically, bishops are a priestly order as well; however, in layman's terms ''priest'' refers only ...

; this seems to have been the last time the rack was used in Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

.

In 1679 Miles Prance, a silversmith who was being questioned about the murder of the respected magistrate Sir Edmund Berry Godfrey

Sir Edmund Berry Godfrey (23 December 1621 – 12 October 1678) was an English magistrate whose mysterious death caused anti-Catholic uproar in England. Contemporary documents also spell the name Edmundbury Godfrey.

Early life

Edmund Berry Godf ...

, was threatened with the rack.

Russia

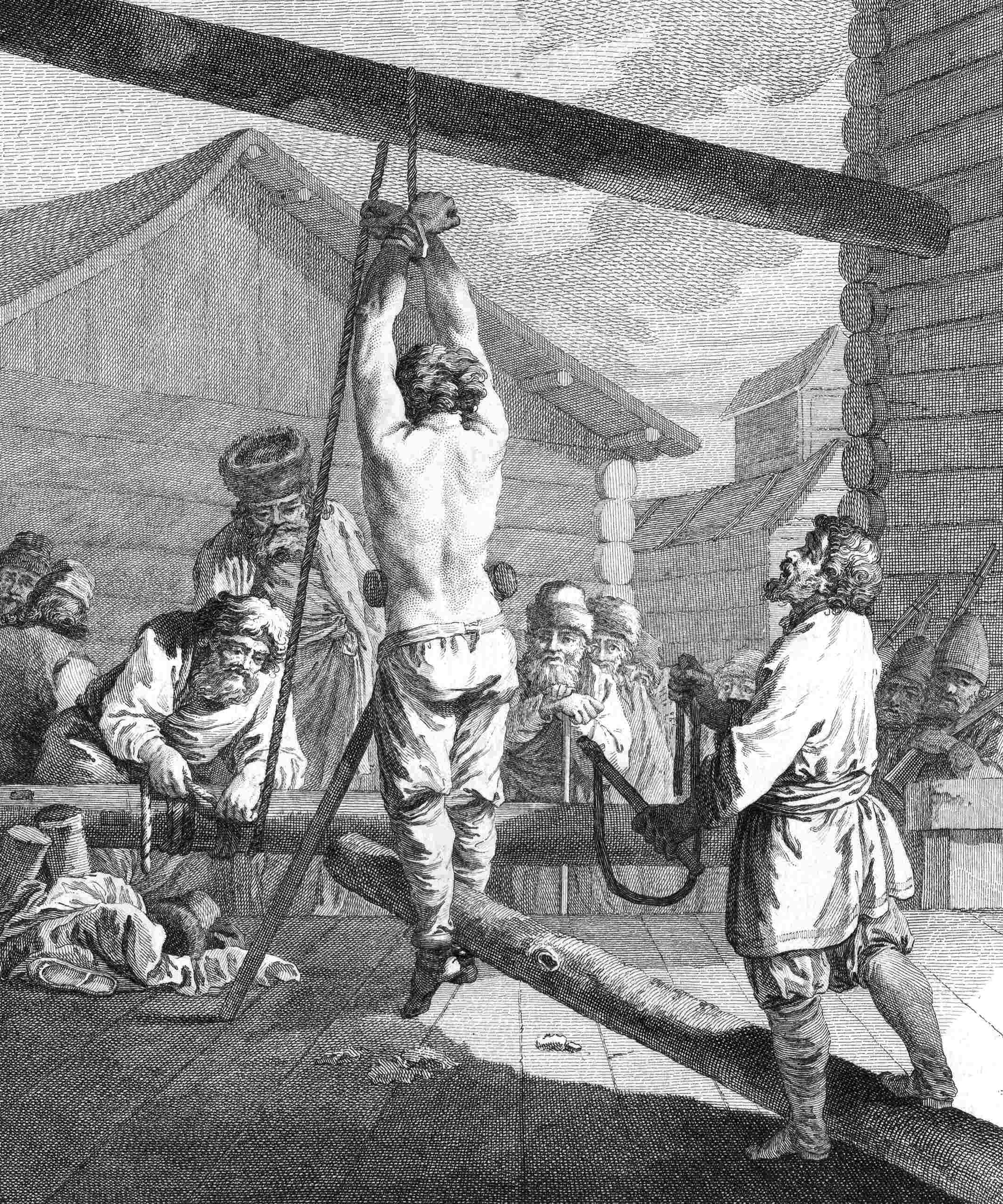

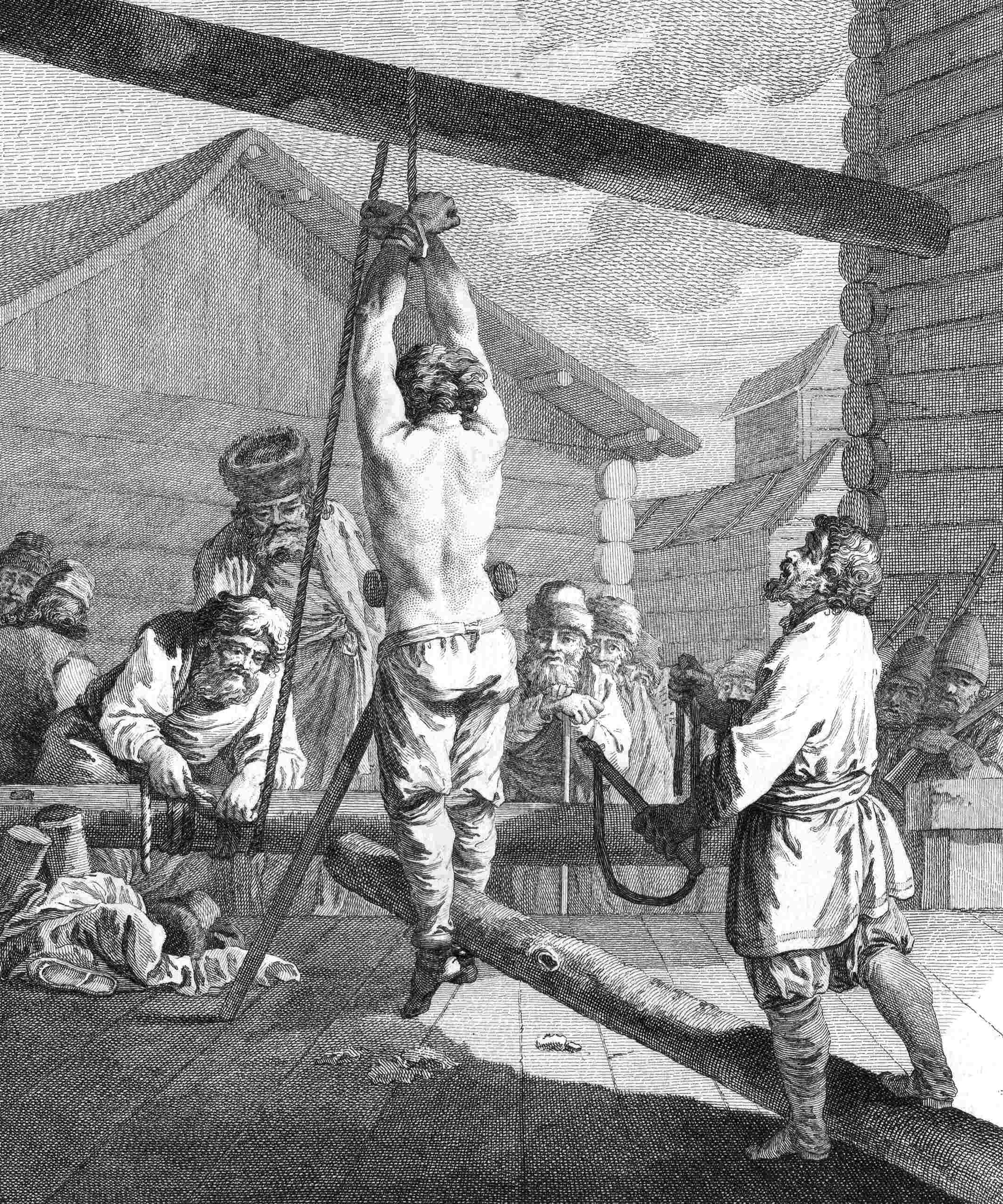

In Russia up to the 18th century the rack (''дыба'', dyba) was a

In Russia up to the 18th century the rack (''дыба'', dyba) was a gallows

A gallows (or scaffold) is a frame or elevated beam, typically wooden, from which objects can be suspended (i.e., hung) or "weighed". Gallows were thus widely used to suspend public weighing scales for large and heavy objects such as sacks ...

-like device for suspending the victims ( strappado). The suspended victims were whipped with a knout

A knout is a heavy scourge-like multiple whip, usually made of a series of rawhide thongs attached to a long handle, sometimes with metal wire or hooks incorporated. The English word stems from a spelling-pronunciation of a French translitera ...

and sometimes burned with torches.''Котошихин Г. К.'О России, в царствование Алексея Михайловича. Современное сочинение Григория Котошихина.

— СПб.: Археографическая комиссия, 1859.

Other punitive positioning devices

The term rack is also used, occasionally, for a number of simpler constructions that merely facilitate corporal punishment, after which it may be named specifically, e.g., '' caning rack'', as in a given jurisdiction it was often the custom to administer any given punishment in a specific position, for which the device (with or without fitting shackling and/or padding) would be chosen or specially made.

Several devices similar in principle to the rack have been used through the ages. One of these was the Wooden Horse, a device used to torture prisoners during the Roman Empire by stretching them on top of a tall wooden frame until the shoulders were dislocated followed by a violent drop into a hanging position and beating. In another variant used primarily in ancient times, the victim's feet were affixed to the ground and his/her hands were chained to a wheel. When the wheel was turned, the person was stretched in a manner similar to the rack. The ''Austrian ladder'' was basically a more vertically oriented rack. As part of the torture, victims would usually be burned under the arms with candles.

The term rack is also used, occasionally, for a number of simpler constructions that merely facilitate corporal punishment, after which it may be named specifically, e.g., '' caning rack'', as in a given jurisdiction it was often the custom to administer any given punishment in a specific position, for which the device (with or without fitting shackling and/or padding) would be chosen or specially made.

Several devices similar in principle to the rack have been used through the ages. One of these was the Wooden Horse, a device used to torture prisoners during the Roman Empire by stretching them on top of a tall wooden frame until the shoulders were dislocated followed by a violent drop into a hanging position and beating. In another variant used primarily in ancient times, the victim's feet were affixed to the ground and his/her hands were chained to a wheel. When the wheel was turned, the person was stretched in a manner similar to the rack. The ''Austrian ladder'' was basically a more vertically oriented rack. As part of the torture, victims would usually be burned under the arms with candles.

See also

*Procrustes

In Greek mythology, Procrustes (; Greek: Προκρούστης ''Prokroustes'', "the stretcher ho hammers out the metal), also known as Prokoptas, Damastes (Δαμαστής, "subduer") or Polypemon, was a rogue smith and bandit from Attica ...

* Strappado

* Breaking on the wheel

References

Sources

*Monestier, M. (1994) ''Peines de mort.'' Paris, France: Le Cherche Midi Éditeur. *Crocker, Harry W.; ''Triumph: The Power and Glory of the Catholic Church - A 2,000 Year History'' {{DEFAULTSORT:Rack (Torture) Ancient instruments of torture Medieval instruments of torture Modern instruments of torture European instruments of torture