Rachel's Tomb on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Rachel's Tomb ( ''QЗқbЕ«rat RДҒбёҘД“l''; Modern he, Ч§Ч‘ЧЁ ЧЁЧ—Чң ''Qever RaбёҘel;'' ar, ЩӮШЁШұ ШұШ§ШӯЩҠЩ„ ''Qabr RДҒбёҘД«l'') is a site revered as the burial place of the Biblical matriarch

Rachel

Rachel () was a Biblical figure, the favorite of Jacob's two wives, and the mother of Joseph and Benjamin, two of the twelve progenitors of the tribes of Israel. Rachel's father was Laban. Her older sister was Leah, Jacob's first wife. Her aun ...

. The site is also referred to as the Bilal bin Rabah mosque ( ar, Щ…ШіШ¬ШҜ ШЁЩ„Ш§Щ„ ШЁЩҶ ШұШЁШ§Шӯ). The tomb is held in esteem by Jews

Jews ( he, ЧҷЦ°Ч”Ч•ЦјЧ“ЦҙЧҷЧқ, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

, Christians

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words '' Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''ChristГіs'' (О§ПҒ ...

, and Muslims

Muslims ( ar, Ш§Щ„Щ…ШіЩ„Щ…ЩҲЩҶ, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

.: вҖңRather than being content with half a dozen or even a full dozen witnesses, we have tried to compile as many sources as possible. During the Roman and Byzantine era, when Christians dominated there was really not much attention given to Rachel's Tomb in Bethlehem. It was only when the Muslims took control that the shrine became an important site. Yet it was rarely considered a shrine exclusive to one religion. To be sure, most of the witnesses were Christian, yet there were also Jewish and Muslim visitors to the tomb. Equally important, the Christian witnesses call attention to the devotion shown to the shrine throughout much of this period by local Muslims and then later also by Jews. As far as the building itself, it appears to be a cooperative venture. There is absolutely no evidence of a pillar erected by Jacob. The earliest form of the structure was that of a pyramid typical of Roman period architecture. Improvements were made first by Crusader Christians a thousand years later, then Muslims in several stages, and finally by the Jewish philanthropist Moses Montefiore in the nineteenth century. If there is one lesson to be learned, it is that this is a shrine held in esteem equally by Jews, Muslims, and Christians. As far as authenticity we are on shaky ground. It may be that the current shrine has physical roots in the biblical era. However, the evidence points to the appropriation of a tomb from the Herod family. If there was a memorial to Rachel in Bethlehem during the late biblical era, it was likely not at the current site of Rachel's Tomb.вҖқ The tomb, located at the northern entrance to the Palestinian

Palestinians ( ar, Ш§Щ„ЩҒЩ„ШіШ·ЩҠЩҶЩҠЩҲЩҶ, ; he, ЧӨЦёЧңЦ·ЧЎЦ°ЧҳЦҙЧҷЧ ЦҙЧҷЧқ, ) or Palestinian people ( ar, Ш§Щ„ШҙШ№ШЁ Ш§Щ„ЩҒЩ„ШіШ·ЩҠЩҶЩҠ, label=none, ), also referred to as Palestinian Arabs ( ar, Ш§Щ„ЩҒЩ„ШіШ·ЩҠЩҶЩҠЩҠЩҶ Ш§Щ„Ш№ШұШЁ, label=non ...

city of Bethlehem

Bethlehem (; ar, ШЁЩҠШӘ Щ„ШӯЩ… ; he, Ч‘ЦөЦјЧҷЧӘ ЧңЦ¶Ч—Ц¶Чқ '' '') is a city in the central West Bank, Palestine, about south of Jerusalem. Its population is approximately 25,000,Amara, 1999p. 18.Brynen, 2000p. 202. and it is the capital o ...

, next to the Rachel's Tomb checkpoint, is built in the style of a traditional maqam, Arabic for shrine.

The burial place of the matriarch Rachel

Rachel () was a Biblical figure, the favorite of Jacob's two wives, and the mother of Joseph and Benjamin, two of the twelve progenitors of the tribes of Israel. Rachel's father was Laban. Her older sister was Leah, Jacob's first wife. Her aun ...

as mentioned in the Jewish Tanakh

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

'' Old Testament and in Muslim literature is contested between this site and several others to the north. Although the site is considered by some scholars as unlikely to be the actual site of the grave, it is by far the most recognized candidate. The earliest extra-biblical records describing this tomb as Rachel's burial place date to the first decades of the 4th century CE. The structure in its current form dates from the Ottoman period, and is situated in a Christian and Muslim cemetery dating from at least the

Descriptive Geography and Brief Historical Sketch of Palestine

1850. "It was always believed that this stood over the grave of the beloved wife of Jacob. But about twenty-five years ago, when the structure needed some repairs, they were compelled to dig down at the foot of this monument; and it was then found that it was not erected over the cavity in which the grave of Rachel actually is; but at a little distance from the monument there was discovered an uncommonly deep cavern, the opening and direction of which was not precisely under the superstructure in question."

176

/ref>

''Biblical researches in Palestine and the adjacent regions: a journal of travels in the years 1838 & 1852, Volume 1''

J. Murray, 1856. p. 218. During the 10th century, Muqaddasi and other geographers fail to mention the tomb, which indicates that it may have lost importance until the

547

/ref> He also noted a drinking water trough at its side and reported that "this place is venerated alike by Muslims, Jews, and Christians".

Thomas Nelson Inc, 2008. p. 57. Pietro Casola (1494) described it as being "beautiful and much honoured by the

202

/ref>

Pilgrimage: from the Ganges to Graceland : an encyclopedia, Volume 1

ABC-CLIO, 2002, p. 511. In 1626,

The Annual Review of Women in World Religions, Volume 4

SUNY Press, 1991, pp. 21вҖ“24. A 1659 Venetian publication of Uri ben Simeon's ''Yichus ha-Abot'' included a small and apparently inaccurate illustration.

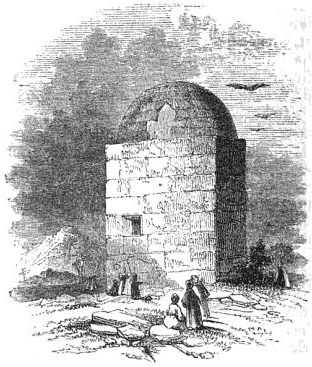

In 1806 François-René Chateaubriand described it as "a square edifice, surmounted with a small dome: it enjoys the privileges of a

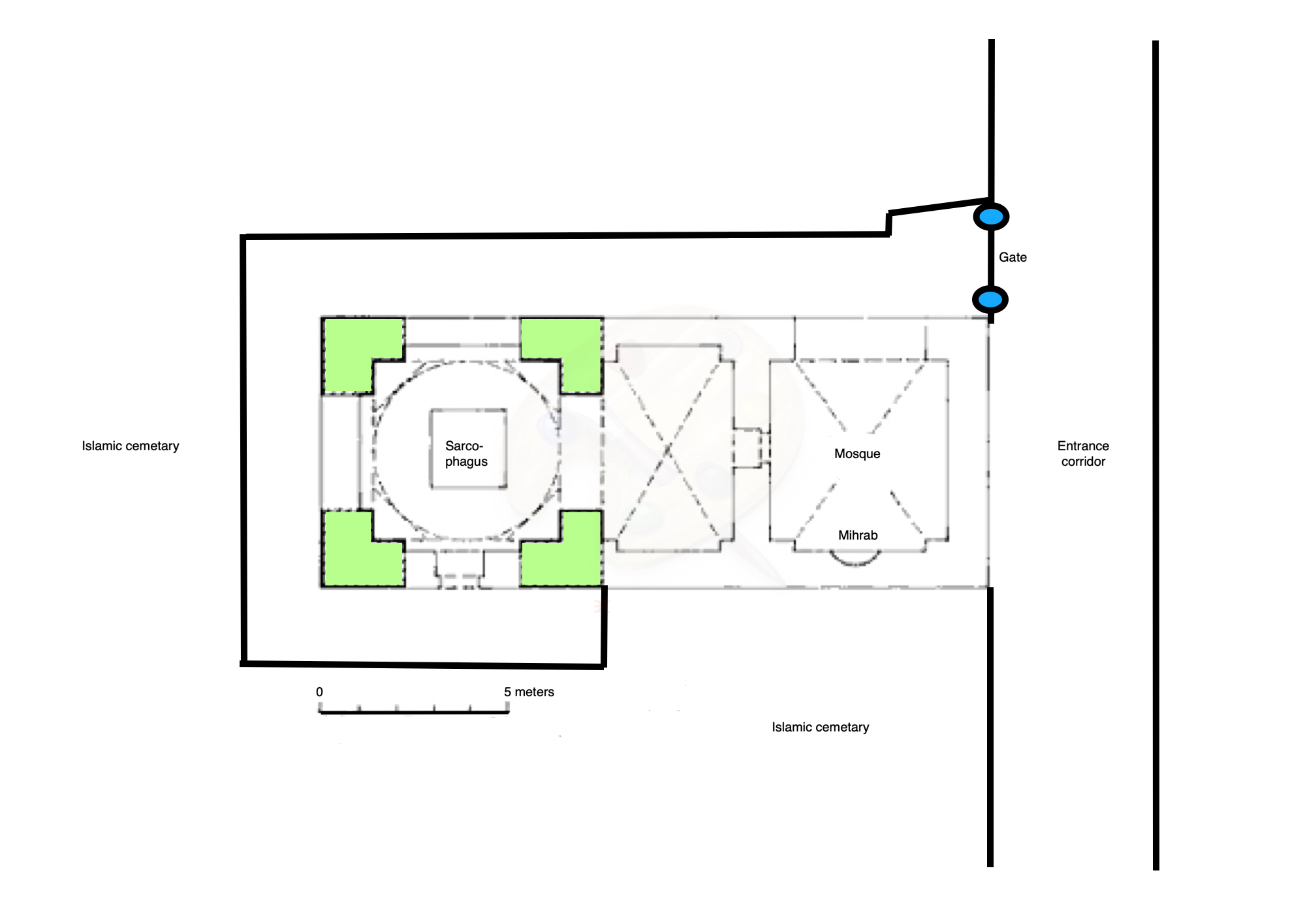

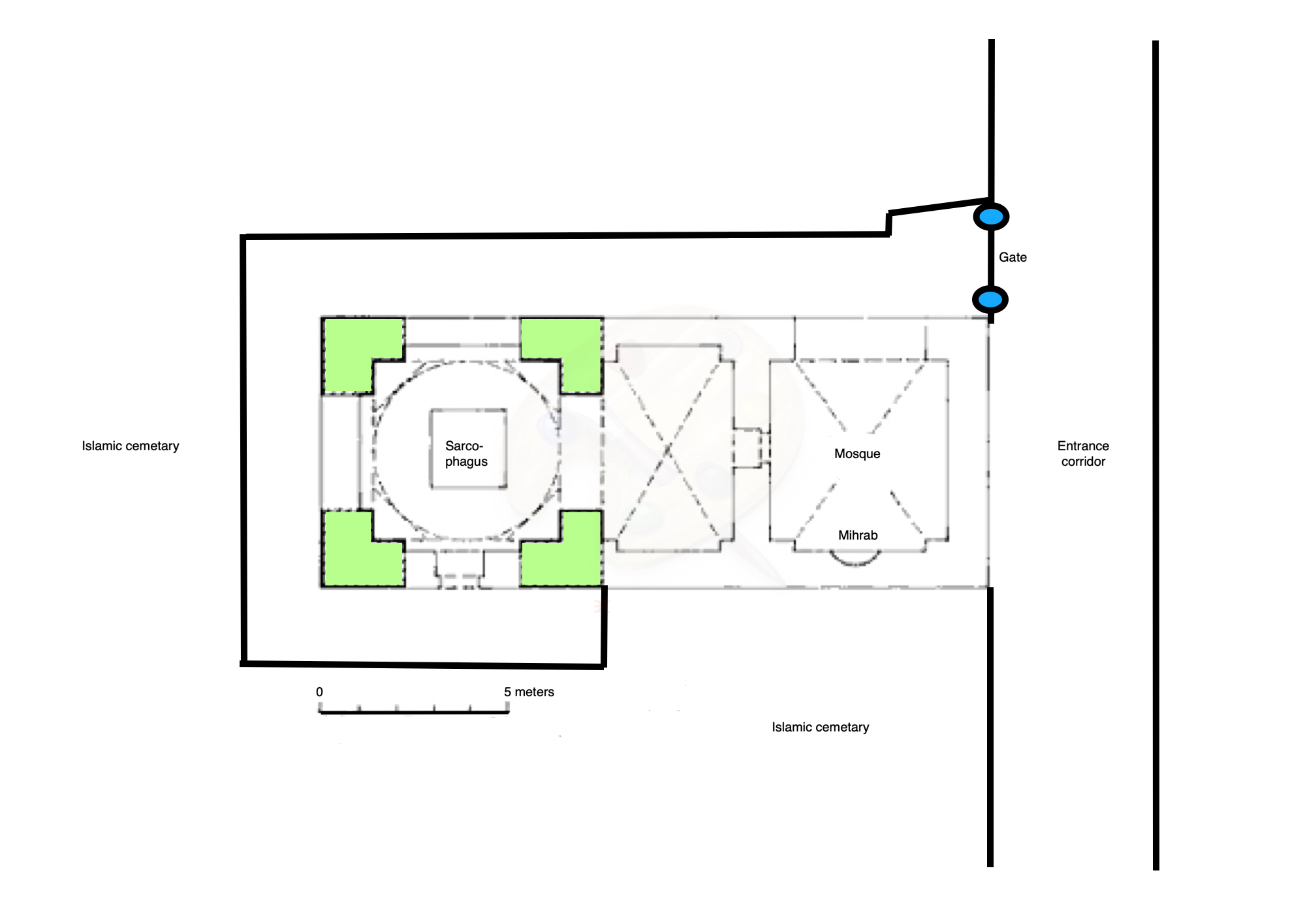

In 1806 FranГ§ois-RenГ© Chateaubriand described it as "a square edifice, surmounted with a small dome: it enjoys the privileges of a  In 1841, Montefiore renovated the site and obtained for the Jews the key of the tomb. He renovated the entire structure, reconstructing and re-plastering its white dome, and added an antechamber, including a mihrab for Muslim prayer, to ease Muslim fears. Professor Glenn Bowman notes that some writers have described this as a вҖңpurchaseвҖқ of the tomb by Montefiore, asserting that this was not the case.

In 1843,

In 1841, Montefiore renovated the site and obtained for the Jews the key of the tomb. He renovated the entire structure, reconstructing and re-plastering its white dome, and added an antechamber, including a mihrab for Muslim prayer, to ease Muslim fears. Professor Glenn Bowman notes that some writers have described this as a вҖңpurchaseвҖқ of the tomb by Montefiore, asserting that this was not the case.

In 1843,

129

/ref>

Three months after the British occupation of Palestine the whole place was cleaned and whitewashed by the Jews without protest from the Muslims. However, in 1921 when the

Three months after the British occupation of Palestine the whole place was cleaned and whitewashed by the Jews without protest from the Muslims. However, in 1921 when the

In view of this, the High Commissioner ruled that, pending appointment of the Holy Places Commission provided for under the Mandate, all repairs should be undertaken by the Government. However, so much indignation was caused in Jewish circles by this decision that the matter was dropped, the repairs not being considered urgent. In 1925 the Sephardic Jewish community requested permission to repair the tomb. The building was then made structurally sound and exterior repairs were effected by the Government, but permission was refused by the Jews (who had the keys) for the Government to repair the interior of the shrine. As the interior repairs were unimportant, the Government dropped the matter, in order to avoid controversy. In 1926 Max Bodenheimer blamed the Jews for letting one of their holy sites appear so neglected and uncared for. During this period, both Jews and Muslims visited the site. From the 1940s, it came to be viewed as a symbol of the Jewish people's return to Zion, to its ancient homeland, For Jewish women, the tomb was associated with fertility and became a place of pilgrimage to pray for successful childbirth. Depictions of the Tomb of Rachel have appeared in Jewish religious books and works of art. Muslims prayed inside the mosque there and the cemetery at the tomb was the main Muslim cemetery in the Bethlehem area. The building was also used for Islamic funeral rituals. It is reported that Jews and Muslims respected each other and accommodated each other's rituals. During the riots of 1929, violence hampered regular visits by Jews to the tomb. Both Jews and Muslims demanded control of the site, with the Muslims claiming it was an integral part of the Muslim cemetery within which it is situated. It also demanded a renewal of the old Muslim custom of purifying corpses in the tomb's antechamber.

'' Old Testament and in Muslim literature is contested between this site and several others to the north. Although the site is considered by some scholars as unlikely to be the actual site of the grave, it is by far the most recognized candidate. The earliest extra-biblical records describing this tomb as Rachel's burial place date to the first decades of the 4th century CE. The structure in its current form dates from the Ottoman period, and is situated in a Christian and Muslim cemetery dating from at least the

Mamluk

Mamluk ( ar, Щ…Щ…Щ„ЩҲЩғ, mamlЕ«k (singular), , ''mamДҒlД«k'' (plural), translated as "one who is owned", meaning " slave", also transliterated as ''Mameluke'', ''mamluq'', ''mamluke'', ''mameluk'', ''mameluke'', ''mamaluke'', or ''marmeluke'') ...

period. When Sir Moses Montefiore

Sir Moses Haim Montefiore, 1st Baronet, (24 October 1784 вҖ“ 28 July 1885) was a British financier and banker, activist, philanthropist and Sheriff of London. Born to an Italian Sephardic Jewish family based in London, afte ...

renovated the site in 1841 and obtained the keys for the Jewish community,, page 47: "The Jews claim possession of the Tomb as they hold the keys and by virtue of the fact that the building which had fallen into complete decay was entirely rebuilt in 1845 by Sir M. Montefiore. It is also asserted that in 1615 Muhammad, Pasha of Jerusalem, rebuilt the Tomb on their behalf, and by firman granted them the exclusive use of it. The Moslems, on the other hand, claim the ownership of the building as being a place of prayer for Moslems of the neighbourhood, and an integral part of the Moslem cemetery within whose precincts it lies. They state that the Turkish Government recognised it as such, and sent an embroidered covering with Arabic inscriptions for the sarcophagus; again, that it is included among the Tombs of the Prophets for which identity signboards were provided by the Ministry of Waqfs in 1328. A.H. In consequence, objection is made to any repair of the building by the Jews, though free access is allowed to it at all times. From local evidence it appears that the keys were obtained by the Jews from the last Moslem guardian, by name Osman Ibrahim al Atayat, some 80 years ago. This would be at the time of the restoration by Sir Moses Montefiore. It is also stated that the antechamber was specially built, at the time of the restoration, as a place of prayer for the Moslems." he also added an antechamber, including a '' mihrab'' for Muslim prayer, to ease Muslim fears. According to , a mazzebah was erected at the site of Rachel's grave in ancient Israel

The history of ancient Israel and Judah begins in the Southern Levant during the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age. "Israel" as a people or tribal confederation (see Israelites) appears for the first time in the Merneptah Stele, an inscri ...

, leading scholars to consider the site to have been a place of worship in ancient Israel. Sered, Rachel's tomb: Societal liminality and the revitalization of a shrine, Religion, January 1989, Vol.19(1):27вҖ“40, , p. 30, "Although the references in Jeremiah and in Genesis 35:22 perhaps hint at the existence of an early cult of some sort at her Tomb, the first concrete evidence of pilgrimage to Rachel's Tomb appears in reports of Christian pilgrims from the first centuries of the Christian Era and Jewish pilgrims from approximately the 10th century. However, in almost all of the pilgrims' records the references to Rachel'sTomb are incidental вҖ“ it is one more shrine on the road from Bethlehem to Jerusalem. Rachel's Tomb continued to appear as a minor shrine in the itineraries of Jewish and Christian pilgrims through the early 20th century." According to Martin Gilbert

Sir Martin John Gilbert (25 October 1936 вҖ“ 3 February 2015) was a British historian and honorary Fellow of Merton College, Oxford. He was the author of eighty-eight books, including works on Winston Churchill, the 20th century, and Jewish h ...

, Jews have made pilgrimage to the tomb since ancient times. According to Frederick Strickert, the first historically recorded pilgrimages to the site were by early Christians, and Christian witnesses wrote of the devotion shown to the shrine "by local Muslims and then later also by Jews"; throughout history, the site was rarely considered a shrine exclusive to one religion and is described as being "held in esteem equally by Jews, Muslims, and Christians". Though Rachel's Tomb has been a common site of Jewish pilgrimage since the twelfth century, in the modern era, a cult with uniquely Rachel elements developed. In contemporary Jewish society it is now considered the third holiest site in Judaism and has become one of the cornerstones of Jewish-Israeli identity.

Following a 1929 British memorandum, in 1949 the UN ruled that the '' Status Quo'', an arrangement approved by the 1878 Treaty of Berlin concerning rights, privileges and practices in certain Holy Places, applies to the site. According to the 1947 United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine

The United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine was a proposal by the United Nations, which recommended a partition of Mandatory Palestine at the end of the British Mandate. On 29 November 1947, the UN General Assembly adopted the Plan as ...

, the tomb was to be part of the internationally administered zone of Jerusalem, but the area was ruled by Jordan

Jordan ( ar, Ш§Щ„ШЈШұШҜЩҶ; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

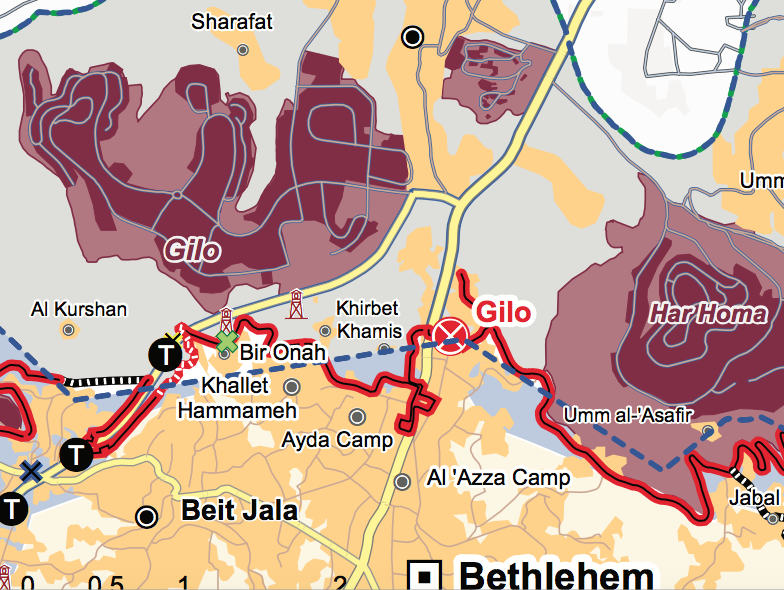

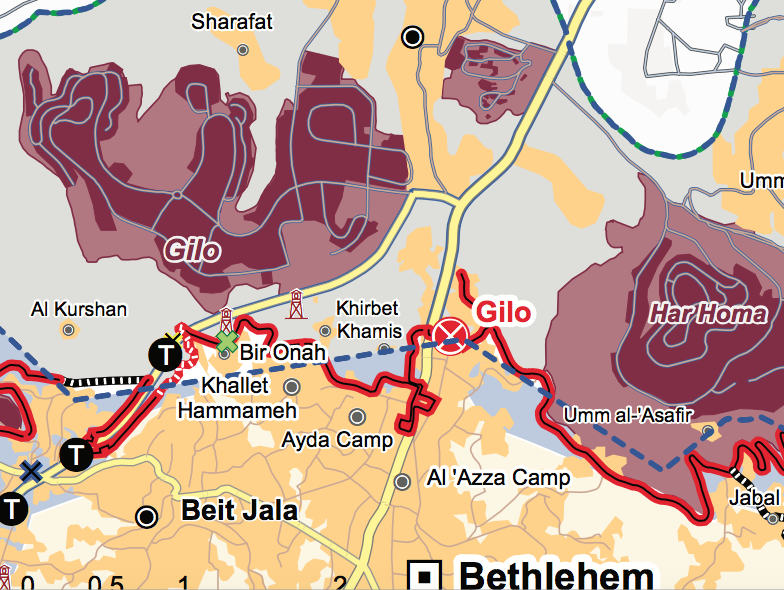

, which prohibited Jews from entering the area. Following the Israeli occupation of the West Bank in 1967, the site's position was formalized in 1995 under the Oslo II Accord in a Palestinian enclave (Area A), with a special arrangement making it subject to the security responsibility of Israel. In 2005, following Israeli approval on 11 September 2002, the Israeli West Bank barrier

The Israeli West Bank barrier, comprising the West Bank Wall and the West Bank fence, is a separation barrier built by Israel along the Green Line and inside parts of the West Bank. It is a contentious element of the IsraeliвҖ“Palestinian ...

was built around the tomb, effectively annexing it to Jerusalem; Checkpoint 300 вҖ“ also known as Rachel's Tomb Checkpoint вҖ“ was built adjacent to the site.: "RachelвҖҷs Tomb was originally assigned to Palestinian Area A under the 28 September 1995 IsraelвҖ“Palestine Interim Accords and thus came under full Palestinian responsibility for internal security, public order and civil affairs. Annex I, Article 5 provided that вҖңduring the Interim PeriodвҖқ Israel will have security control of the road leading to the Tomb and may place guards at the Tomb. On 11 September, 2002, the Israeli security cabinet approved placing Rachel's Tomb on the Jerusalem side of the Security Wall, thus placing Rachel's Tomb within the вҖңJerusalem Security Envelope,вҖқ and de facto annexing it to Jerusalem." A 2005 report from OHCHR

The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, commonly known as the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) or the United Nations Human Rights Office, is a department of the Secretariat of the United Nat ...

Special Rapporteur John Dugard

Christopher John Robert Dugard (born 23 August 1936 in Fort Beaufort), known as John Dugard, is a South African professor of international law. His main academic specializations are in Roman-Dutch law, public international law, jurisprudence, hum ...

noted that: "Although Rachel's Tomb is a site holy to Jews, Muslims and Christians, it has effectively been closed to Muslims and Christians." On October 21, 2015, UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

adopted a resolution reaffirming a 2010 statement that Rachel's Tomb was: "an integral part of Palestine." On 22 October 2015, the tomb was separated from Bethlehem with a series of concrete barriers.

Biblical accounts and disputed location

Northern vs. southern version

Biblical scholarship identifies two different traditions in theHebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

'' Ramah Ramah may refer to: In ancient Israel * Ramathaim-Zophim, the birthplace of Samuel * Ramoth-Gilead, a Levite city of refuge * Ramah in Benjamin, mentioned in the Book of Jeremiah and also in the Gospel of Matthew * Baalath-Beer, also known as Ramo ...

, modern '' Ramah Ramah may refer to: In ancient Israel * Ramathaim-Zophim, the birthplace of Samuel * Ramoth-Gilead, a Levite city of refuge * Ramah in Benjamin, mentioned in the Book of Jeremiah and also in the Gospel of Matthew * Baalath-Beer, also known as Ramo ...

Al-Ram

Al-Ram ( ar, Ш§Щ„ШұЩ‘Ш§Щ…), also transcribed as Al-Ramm, El-Ram, Er-Ram, and A-Ram, is a Palestinian town which lies northeast of Jerusalem, just outside the city's municipal border. The village is part of the built-up urban area of Jerusalem, the ...

, and a southern narrative locating it close to Bethlehem. In rabbinical tradition the duality is resolved by using two different terms in Hebrew to designate these different localities. In the Hebrew version given in Genesis, Rachel

Rachel () was a Biblical figure, the favorite of Jacob's two wives, and the mother of Joseph and Benjamin, two of the twelve progenitors of the tribes of Israel. Rachel's father was Laban. Her older sister was Leah, Jacob's first wife. Her aun ...

and Jacob

Jacob (; ; ar, ЩҠЩҺШ№Щ’ЩӮЩҸЩҲШЁ, YaКҝqЕ«b; gr, бјёОұОәПҺОІ, Iakṓb), later given the name Israel, is regarded as a patriarch of the Israelites and is an important figure in Abrahamic religions, such as Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. J ...

journey from Shechem

Shechem ( ), also spelled Sichem ( ; he, Ч©Ц°ЧҒЧӣЦ¶Чқ, ''Е Йҷбёөem''; ; grc, ОЈП…ПҮОӯОј, SykhГ©m; Samaritan Hebrew: , ), was a Canaanite and Israelite city mentioned in the Amarna Letters, later appearing in the Hebrew Bible as the first c ...

to Hebron

Hebron ( ar, Ш§Щ„Ш®Щ„ЩҠЩ„ or ; he, Ч—Ц¶Ч‘Ц°ЧЁЧ•Ц№Чҹ ) is a Palestinian. city in the southern West Bank, south of Jerusalem. Nestled in the Judaean Mountains, it lies above sea level. The second-largest city in the West Bank (after Eas ...

, a short distance from Ephrath

Ephrath or Ephrathah or Ephratah ( he, ЧҗЦ¶ЧӨЦ°ЧЁЦёЧӘ \ ЧҗЦ¶ЧӨЦ°ЧЁЦёЧӘЦёЧ”) is a biblically-referenced former name of Bethlehem, meaning "fruitful". It is also a personal name.

Biblical place

A very old tradition is that Ephrath refers to Bethleh ...

, which is glossed as Bethlehem

Bethlehem (; ar, ШЁЩҠШӘ Щ„ШӯЩ… ; he, Ч‘ЦөЦјЧҷЧӘ ЧңЦ¶Ч—Ц¶Чқ '' '') is a city in the central West Bank, Palestine, about south of Jerusalem. Its population is approximately 25,000,Amara, 1999p. 18.Brynen, 2000p. 202. and it is the capital o ...

(35:16вҖ“21, 48:7). She dies on the way giving birth to Benjamin:

''"And Rachel died, and was buried on the way to Ephrath, which is Bethlehem. And Jacob set a pillar upon her grave: that is the pillar of Rachel's grave unto this day."'' вҖ” Genesis 35:19вҖ“20Tom Selwyn notes that

R. A. S. Macalister

Robert Alexander Stewart Macalister (8 July 1870 вҖ“ 26 April 1950) was an Irish archaeologist.

Biography

Macalister was born in Dublin, Ireland, the son of Alexander Macalister, then Professor of Zoology, University of Dublin. His father wa ...

, the most authoritative voice on the topography of Rachel's tomb, advanced the view in 1912 that the identification with Bethlehem was based on a copyist's mistake.

The Judean scribal gloss "(Ephrath, ) which is Bethlehem" was added to distinguish it from a similar toponym Ephrathah in the Bethlehem region. Some consider as certain, however, that Rachel's tomb lay to the north, in Benjamite, not in Judean territory, and that the Bethlehem gloss represents a Judean appropriation of the grave, originally in the north, to enhance Judah's prestige. At 1 Samuel 10:2, Rachel's tomb is located in the 'territory of Benjamin at Zelzah.' In the monarchic period

The history of ancient Israel and Judah begins in the Southern Levant during the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age. "Israel" as a people or tribal confederation (see Israelites) appears for the first time in the Merneptah Stele, an inscripti ...

down to the Babylonian captivity, it would follow, Rachel's tomb was thought to lie in Ramah. The indications for this are based on 1 Sam 10:2 and Jer. 31:15, which give an alternative location north of Jerusalem, in the vicinity of ar-Ram

Al-Ram ( ar, Ш§Щ„ШұЩ‘Ш§Щ…), also transcribed as Al-Ramm, El-Ram, Er-Ram, and A-Ram, is a Palestinian town which lies northeast of Jerusalem, just outside the city's municipal border. The village is part of the built-up urban area of Jerusalem, the ...

, biblical Ramah Ramah may refer to:

In ancient Israel

* Ramathaim-Zophim, the birthplace of Samuel

* Ramoth-Gilead, a Levite city of refuge

* Ramah in Benjamin, mentioned in the Book of Jeremiah and also in the Gospel of Matthew

* Baalath-Beer, also known as Ramo ...

, five miles south of Bethel. One conjecture is that before David's conquest of Jerusalem, the ridge road from Bethel might have been called "the Ephrath road" (''derek вҖҷeprДҒtДҒh''. ; ''derekвҖҷeprДҒt,'' ), hence the passage in Genesis meant 'the road ''to'' Ephrath or Bethlehem,' on which Ramah, if that word refers to a toponym

Toponymy, toponymics, or toponomastics is the study of '' toponyms'' (proper names of places, also known as place names and geographic names), including their origins, meanings, usage and types. Toponym is the general term for a proper name of ...

, lay. A possible location in Ramah could be the five stone monuments north of Hizma. Known as '' Qubur Bene Isra'in'', the largest so-called tomb of the group, the function of which is obscure, has the name ''Qabr Umm beni Isra'in'', that is, "tomb of the mother of the descendants of Israel".

Bethlehem structure

As to the structure outside Bethlehem being placed exactly over an ancient tomb, it was revealed during excavations in around 1825 that it was not built over a cavern; however, a deep cavern was discovered a small distance from the site.Schwarz, JosephDescriptive Geography and Brief Historical Sketch of Palestine

1850. "It was always believed that this stood over the grave of the beloved wife of Jacob. But about twenty-five years ago, when the structure needed some repairs, they were compelled to dig down at the foot of this monument; and it was then found that it was not erected over the cavity in which the grave of Rachel actually is; but at a little distance from the monument there was discovered an uncommonly deep cavern, the opening and direction of which was not precisely under the superstructure in question."

History

Byzantine period

Traditions regarding the tomb at this location date back to the beginning of the 4th century AD.Pringle, 1998, p176

/ref>

Eusebius

Eusebius of Caesarea (; grc-gre, О•бҪҗПғОӯОІО№ОҝПӮ ; 260/265 вҖ“ 30 May 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilus (from the grc-gre, О•бҪҗПғОӯОІО№ОҝПӮ П„ОҝбҝҰ О ОұОјПҶОҜО»ОҝП…), was a Greek historian of Christianity, exegete, and Chris ...

' ''Onomasticon'' (written before 324) and the Bordeaux Pilgrim (333вҖ“334) mention the tomb as being located 4 miles from Jerusalem.

Early Muslim period

In the late 7th century, the tomb was marked with a stone pyramid, devoid of any ornamentation.Edward Robinson, Eli Smith''Biblical researches in Palestine and the adjacent regions: a journal of travels in the years 1838 & 1852, Volume 1''

J. Murray, 1856. p. 218. During the 10th century, Muqaddasi and other geographers fail to mention the tomb, which indicates that it may have lost importance until the

Crusaders

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were in ...

revived its veneration.

Crusader period

Muhammad al-Idrisi

Abu Abdullah Muhammad al-Idrisi al-Qurtubi al-Hasani as-Sabti, or simply al-Idrisi ( ar, ШЈШЁЩҲ Ш№ШЁШҜ Ш§Щ„Щ„ЩҮ Щ…ШӯЩ…ШҜ Ш§Щ„ШҘШҜШұЩҠШіЩҠ Ш§Щ„ЩӮШұШ·ШЁЩҠ Ш§Щ„ШӯШіЩҶЩҠ Ш§Щ„ШіШЁШӘЩҠ; la, Dreses; 1100 вҖ“ 1165), was a Muslim geographer, cartogra ...

(1154) writes, "Half-way down the road etween Bethlehem and Jerusalemis the tomb of Rachel (''Rahil''), the mother of Joseph

Joseph is a common male given name, derived from the Hebrew Yosef (ЧҷЧ•Ц№ЧЎЦөЧЈ). "Joseph" is used, along with "Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the mo ...

and of Benjamin, the two sons of Jacob

Jacob (; ; ar, ЩҠЩҺШ№Щ’ЩӮЩҸЩҲШЁ, YaКҝqЕ«b; gr, бјёОұОәПҺОІ, Iakṓb), later given the name Israel, is regarded as a patriarch of the Israelites and is an important figure in Abrahamic religions, such as Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. J ...

peace upon them all! The tomb is covered by twelve stones, and above it is a dome vaulted."

Benjamin of Tudela (1169вҖ“71) was the first Jewish pilgrim to describe his visit to the tomb. He mentioned a pillar made of 11 stones and a cupola resting on four columns "and all the Jews that pass by carve their names upon the stones of the pillar." Petachiah of Regensburg explains that the 11 stones represented the tribes of Israel, excluding Benjamin, since Rachel had died during his birth. All were marble, with that of Jacob on top."

Mamluk period

In the 14th century, Antony of Cremona referred to the cenotaph as "the most wonderful tomb that I shall ever see. I do not think that with 20 pairs of oxen it would be possible to extract or move one of its stones." It was described by Franciscan pilgrim Nicolas of Poggibonsi (1346вҖ“50) as being 7 feet high and enclosed by a rounded tomb with three gates. From around the 15th century onwards, if not earlier, the tomb was occupied and maintained by the Muslim rulers. The Russian deacon Zozimos describes it as being a mosque in 1421. A guide published in 1467 credits Shahin al-Dhahiri with the building of a cupola, cistern and drinking fountain at the site. The Muslim rebuilding of the "dome on four columns" was also mentioned byFrancesco Suriano

Francesco Suriano (1445-after 1481) was an Italian friar of the Franciscan order, who wrote a guide for travel to the Holy Land.

He was born in 1445 to a noble family of Venice. He may have first travelled to Alexandria, Egypt in 1462, as a young ...

in 1485. Felix Fabri

Felix Fabri (also spelt Faber; 1441 вҖ“ 1502) was a Swiss Dominican theologian. He left vivid and detailed descriptions of his pilgrimages to Palestine and also in 1489 authored a book on the history of Swabia, entitled ''Historia Suevorum''.

...

(1480вҖ“83) described it as being "a lofty pyramid, built of square and polished white stone";Fabri, 1896, p547

/ref> He also noted a drinking water trough at its side and reported that "this place is venerated alike by Muslims, Jews, and Christians".

Bernhard von Breidenbach

Bernhard von Breidenbach (also ''Breydenbach'') (ca. 1440 вҖ“ 1497) was a politician in the Electorate of Mainz. He wrote a travel report, ''Peregrinatio in terram sanctam'' (1486), from his travels to the Holy Land.

In Jerusalem he met Felix F ...

of Mainz (1483) described women praying at the tomb and collecting stones to take home, believing that they would ease their labour. Reflections of God's Holy Land: A Personal Journey Through IsraelThomas Nelson Inc, 2008. p. 57. Pietro Casola (1494) described it as being "beautiful and much honoured by the

Moors

The term Moor, derived from the ancient Mauri, is an exonym first used by Christian Europeans to designate the Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily and Malta during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a distinct or ...

." Mujir al-Din al-'Ulaymi

MujД«r al-DД«n al-КҝUlaymД« (Arabic: ) (1456вҖ“1522), often simply Mujir al-Din, was a Jerusalemite ''qadi'' and historian whose principal work chronicled the history of Jerusalem and Hebron in the Middle Ages.Little, 1995, p. 237.van Donze ...

(1495), the Jerusalemite ''qadi

A qДҒбёҚД« ( ar, ЩӮШ§Ш¶ЩҠ, QДҒбёҚД«; otherwise transliterated as qazi, cadi, kadi, or kazi) is the magistrate or judge of a '' sharД«Кҝa'' court, who also exercises extrajudicial functions such as mediation, guardianship over orphans and mino ...

'' and Arab historian, writes under the heading of ''Qoubbeh RГўhГ®l'' ("Dome of Rachel") that Rachel's tomb lies under this dome on the road between Bethlehem and Bayt Jala and that the edifice is turned towards the '' Sakhrah'' (the rock inside the Dome of the Rock) and widely visited by pilgrims.Mujir al-Dyn, 1876, p202

/ref>

Ottoman period

Seventeenth century

In 1615 Muhammad Pasha of Jerusalem repaired the structure and transferred exclusive use of the site to the Jews.Linda Kay Davidson, David Martin GitlitzPilgrimage: from the Ganges to Graceland : an encyclopedia, Volume 1

ABC-CLIO, 2002, p. 511. In 1626,

Franciscus Quaresmius

Francisco Quaresmio or Quaresmi (4 April 1583 вҖ“ 25 October 1650), better known by his Latin name Franciscus Quaresmius, was an Italian writer and Orientalist.

Life

Quaresmius was born at Lodi. His father was the nobleman Alberto Quare ...

visited the site and found that the tomb had been rebuilt by the locals several times. He also found near it a cistern and many Muslim graves.

George Sandys

George Sandys ( "sands"; 2 March 1578''Sandys, George''

in: ''EncyclopГҰdia Britannica'' online ...

wrote in 1632 that вҖңThe sepulchre of Rachel... is mounted on a square... within which another sepulchre is used for a place of prayer by the Mohometans".

Rabbi Moses Surait of Prague (1650) described a high dome on the top of the tomb, an opening on one side, and a big courtyard surrounded by bricks. He also described a local Jewish cult associated with the site. Sered, Our Mother Rachel, in Arvind Sharma, Katherine K. Young (eds.)in: ''EncyclopГҰdia Britannica'' online ...

The Annual Review of Women in World Religions, Volume 4

SUNY Press, 1991, pp. 21вҖ“24. A 1659 Venetian publication of Uri ben Simeon's ''Yichus ha-Abot'' included a small and apparently inaccurate illustration.

Eighteenth century

In March 1756, the Istanbul Jewish Committee for the Jews of Palestine instructed that 500kuruЕҹ

KuruЕҹ ( ; ), also gurush, ersh, gersh, grush, grosha, and grosi, are all names for currency denominations in and around the territories formerly part of the Ottoman Empire. The variation in the name stems from the different languages it is us ...

used by the Jews of Jerusalem to fix a wall at the tomb were to be repaid and used instead for more deserving causes. In 1788, walls were built to enclose the arches. According to Richard Pococke

Richard Pococke (19 November 1704 вҖ“ 25 September 1765)''Notes and Queries'', p. 129. was an English-born churchman, inveterate traveller and travel writer. He was the Bishop of Ossory (1756вҖ“65) and Meath (1765), both dioceses of the Church ...

, this was done to "hinder the Jews from going into it". Pococke also reports that the site was highly regarded by Turks as a place of burial.

Nineteenth century

mosque

A mosque (; from ar, Щ…ЩҺШіЩ’Ш¬ЩҗШҜ, masjid, ; literally "place of ritual prostration"), also called masjid, is a place of prayer for Muslims. Mosques are usually covered buildings, but can be any place where prayers ( sujud) are performed, ...

, for the Turks as well as the Arabs, honour the families of the patriarchs. .it is evidently a Turkish edifice, erected in memory of a santon.

An 1824 report described "a stone building, evidently of Turkish construction, which terminates at the top in a dome. Within this edifice is the tomb. It is a pile of stones covered with white plaster, about 10 feet long and nearly as high. The inner wall of the building and the sides of the tomb are covered with Hebrew names, inscribed by Jews."

When the structure was undergoing repairs in around 1825, excavations at the foot of the monument revealed that it was not built directly over an underground cavity. However, a small distance from the site, an unusually deep cavern was discovered.

Proto-Zionist banker Sir Moses Montefiore

Sir Moses Haim Montefiore, 1st Baronet, (24 October 1784 вҖ“ 28 July 1885) was a British financier and banker, activist, philanthropist and Sheriff of London. Born to an Italian Sephardic Jewish family based in London, aft ...

visited Rachel's Tomb together with his wife on their first visit to the Holy Land in 1828. The couple were childless, and Lady Montefiore was deeply moved by the tomb, which was in good condition at that time. Before the couple's next visit, in 1839, the Galilee earthquake of 1837

The Galilee earthquake of 1837, often called the Safed earthquake, shook the Galilee on January 1 and is one of a number of moderate to large events that have occurred along the Dead Sea Transform (DST) fault system that marks the boundary of t ...

had heavily damaged the tomb. In 1838 the tomb was described as "merely an ordinary Muslim Wely, or tomb of a holy person; a small square building of stone with a dome, and within it a tomb in the ordinary Muhammedan form; the whole plastered over with mortar. It is neglected and falling to decay; though pilgrimages are still made to it by the Jews. The naked walls are covered with names in several languages; many of them Hebrew."

In 1841, Montefiore renovated the site and obtained for the Jews the key of the tomb. He renovated the entire structure, reconstructing and re-plastering its white dome, and added an antechamber, including a mihrab for Muslim prayer, to ease Muslim fears. Professor Glenn Bowman notes that some writers have described this as a вҖңpurchaseвҖқ of the tomb by Montefiore, asserting that this was not the case.

In 1843,

In 1841, Montefiore renovated the site and obtained for the Jews the key of the tomb. He renovated the entire structure, reconstructing and re-plastering its white dome, and added an antechamber, including a mihrab for Muslim prayer, to ease Muslim fears. Professor Glenn Bowman notes that some writers have described this as a вҖңpurchaseвҖқ of the tomb by Montefiore, asserting that this was not the case.

In 1843, Ridley Haim Herschell

Ridley Haim Herschell (7 April 1807 вҖ“ 14 April 1864) was a Polish-born British minister who converted from Judaism to evangelical Christianity. He was a founder of the British Society for the Propagation of the Gospel Among the Jews (1842) and ...

described the building as an ordinary Muslim tomb. He reported that Jews, including Montefiore, were obliged to remain outside the tomb, and prayed at a hole in the wall, so that their voices enter into the tomb. In 1844, William Henry Bartlett

William Henry Bartlett (March 26, 1809 вҖ“ September 13, 1854) was a British artist, best known for his numerous drawings rendered into steel engravings.

Biography

Bartlett was born in Kentish Town, London in 1809. He was apprenticed to John Bri ...

referred to the tomb as a "Turkish Mosque", following a visit to the area in 1842.

In 1845, Montefiore made further architectural improvements at the tomb. He extended the building by constructing an adjacent vaulted ante-chamber on the east for Muslim prayer

Prayer is an invocation or act that seeks to activate a rapport with an object of worship through deliberate communication. In the narrow sense, the term refers to an act of supplication or intercession directed towards a deity or a deified ...

use and burial preparation, possibly as an act of conciliation. The room included a '' mihrab'' facing Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow ...

.

In the mid-1850s, the marauding Arab e-Ta'amreh tribe forced the Jews to furnish them with an annual ВЈ30 payment to prevent them from damaging the tomb.

According to Elizabeth Anne Finn

Elizabeth Anne Finn (1825вҖ“1921) was a British writer and the wife of James Finn, British Consul in Jerusalem, in Ottoman Palestine between 1846 and 1863. She and her daughter co-founded the Distressed Gentlefolk's Aid Association, the predec ...

, wife of the British consul, James Finn, the only time the Sephardic Jewish community left the Old City of Jerusalem was for monthly prayers at "Rachel's Sepulchre" or Hebron.

In 1864, the Jews of Bombay

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay вҖ” the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' financial centre of India. According to the United Nations, as of 2018, Mumbai is the second-m ...

donated money to dig a well. Although Rachel's Tomb was only an hour and a half walk from the Old City of Jerusalem, many pilgrims found themselves very thirsty and unable to obtain fresh water. Every ''Rosh Chodesh

Rosh Chodesh or Rosh Hodesh ( he, ЧЁЧҗЧ© Ч—Ч•Ч“Ч©; trans. ''Beginning of the Month''; lit. ''Head of the Month'') is the name for the first day of every month in the Hebrew calendar, marked by the birth of a new moon. It is considered a minor ...

'' (beginning of the Jewish month), the Maiden of Ludmir would lead her followers to Rachel's tomb and lead a prayer service with various rituals, which included spreading out requests of the past four weeks over the tomb. On the traditional anniversary of Rachel's death, she would lead a solemn procession to the tomb where she chanted psalms

The Book of Psalms ( or ; he, ЧӘЦ°ЦјЧ”ЦҙЧңЦҙЦјЧҷЧқ, , lit. "praises"), also known as the Psalms, or the Psalter, is the first book of the ("Writings"), the third section of the Tanakh, and a book of the Old Testament. The title is derived ...

in a night-long vigil.

In 1868 a publication by the Catholic missionary society the Paulist Fathers

The Paulist Fathers, officially named the Missionary Society of Saint Paul the Apostle ( la, Societas Sacerdotum Missionariorum a Sancto Paulo Apostolo), abbreviated CSP, is a Catholic society of apostolic life of Pontifical Right for men founded ...

noted that " achel'smemory has always been held in respect by the Jews and Christians, and even now the former go there every Thursday, to pray and read the old, old history of this mother of their race. When leaving Bethlehem for the fourth and last time, after we had passed the tomb of Rachel, on our way to Jerusalem, Father Luigi and I met a hundred or more Jews on their weekly visit to the venerated spot."

The Hebrew monthly ''ha-Levanon'' of August 19, 1869, rumored that a group of Christians had purchased land around the tomb and were in the process of demolishing Montefiore's vestibule in order to erect a church there. During the following years, land in the vicinity of the tomb was acquired by Nathan Straus

Nathan Straus (January 31, 1848 вҖ“ January 11, 1931) was an American merchant and philanthropist who co-owned two of New York City's biggest department stores, R. H. Macy & Company and Abraham & Straus. He is a founding father and namesake f ...

. In October 1875, Rabbi Zvi Hirsch Kalischer

Zvi (Zwi) Hirsch Kalischer (24 March 1795 вҖ“ 16 October 1874) was an Orthodox German rabbi who expressed views, from a religious perspective, in favour of the Jewish re-settlement of the Land of Israel, which predate Theodor Herzl and the Zionist ...

purchased three dunams of land near the tomb intending to establish a Jewish farming colony there. Custody of the land was transferred to the Perushim community in Jerusalem. In the 1883 volume of the PEF Survey of Palestine, Conder and Kitchener noted: "A modern Moslem building stands over the site, and there are Jewish graves near it... The court... is used as a praying-place by Moslems... The inner chambers... are visited by Jewish men and women on Fridays."Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, p.129

/ref>

Twentieth century

In 1912 the Ottoman Government permitted the Jews to repair the shrine itself, but not the antechamber. In 1915 the structure had four walls, each about 7 m (23 ft.) long and 6 m (20 ft.) high. The dome, rising about 3 m (10 ft.), "is used by the Moslems for prayer; its holy character has hindered them from removing the Hebrew letters from its walls."British Mandate period

Chief Rabbinate

Chief Rabbi ( he, ЧЁЧ‘ ЧЁЧҗЧ©Чҷ ''Rav Rashi'') is a title given in several countries to the recognized religious leader of that country's Jewish community, or to a rabbinic leader appointed by the local secular authorities. Since 1911, through a ...

applied to the Municipality of Bethlehem for permission to perform repairs at the site, local Muslims objected.United Nations Conciliation Commission For Palestine: Committee on Jerusalem. (April 8, 1949)In view of this, the High Commissioner ruled that, pending appointment of the Holy Places Commission provided for under the Mandate, all repairs should be undertaken by the Government. However, so much indignation was caused in Jewish circles by this decision that the matter was dropped, the repairs not being considered urgent. In 1925 the Sephardic Jewish community requested permission to repair the tomb. The building was then made structurally sound and exterior repairs were effected by the Government, but permission was refused by the Jews (who had the keys) for the Government to repair the interior of the shrine. As the interior repairs were unimportant, the Government dropped the matter, in order to avoid controversy. In 1926 Max Bodenheimer blamed the Jews for letting one of their holy sites appear so neglected and uncared for. During this period, both Jews and Muslims visited the site. From the 1940s, it came to be viewed as a symbol of the Jewish people's return to Zion, to its ancient homeland, For Jewish women, the tomb was associated with fertility and became a place of pilgrimage to pray for successful childbirth. Depictions of the Tomb of Rachel have appeared in Jewish religious books and works of art. Muslims prayed inside the mosque there and the cemetery at the tomb was the main Muslim cemetery in the Bethlehem area. The building was also used for Islamic funeral rituals. It is reported that Jews and Muslims respected each other and accommodated each other's rituals. During the riots of 1929, violence hampered regular visits by Jews to the tomb. Both Jews and Muslims demanded control of the site, with the Muslims claiming it was an integral part of the Muslim cemetery within which it is situated. It also demanded a renewal of the old Muslim custom of purifying corpses in the tomb's antechamber.

Jordanian period

Following the 1948 ArabвҖ“Israeli War till 1967, the site was occupied then annexed by Jordan. the site was overseen by the Islamicwaqf

A waqf ( ar, ЩҲЩҺЩӮЩ’ЩҒ; ), also known as hubous () or '' mortmain'' property is an inalienable charitable endowment under Islamic law. It typically involves donating a building, plot of land or other assets for Muslim religious or charitab ...

. On December 11, 1948, the UN General Assembly passed Resolution 194

United Nations General Assembly Resolution 194 is a resolution adopted near the end of the 1947вҖ“1949 Palestine war. The Resolution defines principles for reaching a final settlement and returning Palestine refugees to their homes. Article 11 o ...

which called for free access to all the holy places in Israel and the remainder of the territory of the former Palestine Mandate of Great Britain. In April 1949, the Jerusalem Committee prepared a document for the UN Secretariat in order to establish the status of the different holy places in the area of the former British Mandate for Palestine. It noted that ownership of Rachel's Tomb was claimed by both Jews and Muslims. The Jews claimed possession by virtue of a 1615 firman granted by the Pasha of Jerusalem which gave them exclusive use of the site and that the building, which had fallen into decay, was entirely restored by Moses Montefiore in 1845; the keys were obtained by the Jews from the last Muslim guardian at this time. The Muslims claimed the site was a place of Muslim prayer and an integral part of the Muslim cemetery within which it was situated. They stated that the Ottoman Government had recognised it as such and that it is included among the Tombs of the Prophets for which identity signboards were issued by the Ministry of Waqfs in 1898. They also asserted that the antechamber built by Montefiore was specially built as a place of prayer for Muslims. The UN ruled that the ''status quo'', an arrangement approved by the Ottoman Decree of 1757 concerning rights, privileges and practices in certain Holy Places, apply to the site.

In theory, free access was to be granted as stipulated in the 1949 Armistice Agreements

The 1949 Armistice Agreements were signed between Israel and Egypt,Israel and the Palestinian territories

Rough Guides, 1998. p. 395. Non-Israeli Jews, however, continued to visit the site. During this period the Muslim cemetery was expanded.

Following the

Following the

Son of the Cypresses: Memories, Reflections, and Regrets from a Political Life

University of California Press, 2007, pp. 44вҖ“45. Islamic crescents, inscribed into the rooms of the structure, were subsequently erased. Muslims were prevented from using the mosque, although they were allowed to use the cemetery for a while. Starting in 1993, Muslims were barred from using the cemetery. According to Bethlehem University, " cess to Rachel's Tomb is now restricted to tourists entering from Israel."

.

In 1996, Israel began an 18-month fortification of the site at a cost of $2m. It included a wall and adjacent military post.

After an attack on

.

In 1996, Israel began an 18-month fortification of the site at a cost of $2m. It included a wall and adjacent military post.

After an attack on  At the end of 2000, when the Second Intifada broke out, the tomb came under attack for 41 days. In May 2001, fifty Jews found themselves trapped inside by a firefight between the IDF and Palestinian Authority gunmen. In March 2002 the IDF returned to Bethlehem as part of Operation Defensive Shield and remained there for an extended period of time.

On 11 September 2002, the Israeli security cabinet approved incorporating the tomb on the Israeli side of the West Bank barrier and surrounded by a concrete wall and watchtowers. This has been described as "de facto annexing it to Jerusalem." In February 2005, the

At the end of 2000, when the Second Intifada broke out, the tomb came under attack for 41 days. In May 2001, fifty Jews found themselves trapped inside by a firefight between the IDF and Palestinian Authority gunmen. In March 2002 the IDF returned to Bethlehem as part of Operation Defensive Shield and remained there for an extended period of time.

On 11 September 2002, the Israeli security cabinet approved incorporating the tomb on the Israeli side of the West Bank barrier and surrounded by a concrete wall and watchtowers. This has been described as "de facto annexing it to Jerusalem." In February 2005, the

Ynet, 10/29/2010

The tomb of Sir

The tomb of Sir

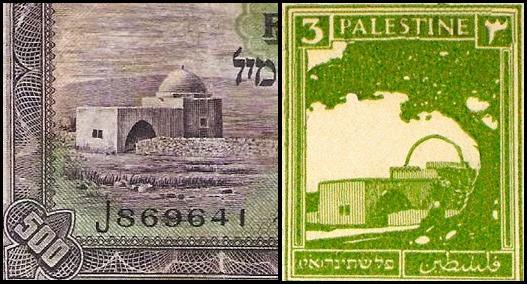

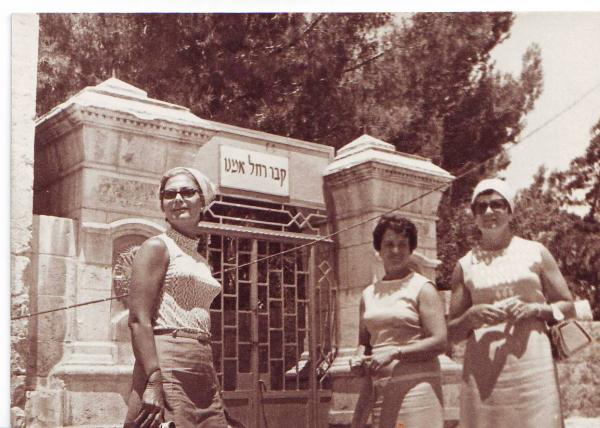

Bethlehem rachel tomb 1880.jpg, c.1880

Bethlehem. Rachel's Tomb, 68.Holy land photographed. Daniel B. Shepp. 1894.jpg, 1894

File:Rachel's Tomb c1910.jpg, c.1910

File:RACHEL'S TOMB IN BETHLEHEM. Ч§Ч‘ЧЁ ЧЁЧ—Чң Ч‘Ч‘ЧҷЧӘ ЧңЧ—Чқ.D21-004.jpg, 1933

File:TOMB-GATE.JPG, 2005 showing the two Ottoman

* Mid 1990s North-east perspective available externally:

* 2008 picture of the same North-east perspective:

File:Rachel's tomb 1930s II.jpg, 1930s

File:Ludwig Blum - Rachel's Tomb, 1931.JPG, 1939 painting of Rachel's Tomb by Ludwig Blum

RACHEL'S TOMB NEAR THE ENTRANCE TO BETHLEHEM. Ч§Ч‘ЧЁ ЧЁЧ—Чң Ч‘Ч‘ЧҷЧӘ ЧңЧ—Чқ.D11-133.jpg, 1940

File:Muslim cemetery Bethlehem 03.jpg, 2016

File:RachelвҖҷs Tomb, Bethlehem, from the West, March 2018.jpg, 2018

File:Roman aqueduct near Rachel's Tomb LOC matpc.16575.jpg, 1934вҖ“1939

File:Raakelinhauta.png, 1978

* A 2014 photo from Hebrew Wikipedia: :he:Ч§Ч•Ч‘ЧҘ:Keverachel01.jpg

File:PikiWiki Israel 13447 Rachels Tomb.jpg, 1912

File:Tomb of Rachel in Bethlehem.jpg, Unknown

File:Rachel's Tomb LOC matpc.09188.tif, 1898вҖ“1946

File:Rachel's tomb 1930s.jpg, 1930s

File:131011 11403ЧҗЧ•Ч§Ч”.jpg, 1940s?

File:RachelвҖҷs tomb 2018, close up.jpg, 2018

File:Rachel's Tomb, near Bethlehem, 1891.jpg, 1891

PikiWiki Israel 4649 Rachels Tomb.jpg, 1934

Sharing and Exclusion: The Case of Rachel's Tomb

Җқ Jerusalem Quarterly 58 (July): 30вҖ“49. * * * * * * * Gitlitz, David M. & Linda Kay Davidson. вҖңPilgrimage and the JewsвҖҷвҖҷ (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2006). * * * * Pullan, W. (2013). Bible and Gun: Militarism in Jerusalem's Holy Places. Space and Polity, 17 (3), 335вҖ“56, dx.doi.org/10.1080/13562576.2013.853490 * Selwyn, T. (2009) Ghettoizing a matriarch and a city: An everyday story from the Palestinian/Israeli borderlands, Journal of Borderlands Studies, 24(3), pp. 39вҖ“ 55 *

p. 177

ff) * * UNESCO (19 March 2010), 184 EX/37

The Two Palestinian Sites of Al-Haram Al-Ibrahimi/Tomb of the Patriarchs in Al-Khalil/Hebron and the Bilal bin Rabah Mosques/Rachael's Tomb in Bethlehem

Fact Sheet on Israeli Consolidation of Palestinian Heritage Sites in the Occupied Palestinian Territory: The Case if Hebron and Bethlehem *

Rachel's Tomb Website

General Info., History, Pictures, Video, Visitor Info., Transportation

Is this Rachel's Tomb? A geographical and historical review

A site dedicated to Rachel's Tomb

* Survey of Western Palestine, Map 17:

IAA

Rough Guides, 1998. p. 395. Non-Israeli Jews, however, continued to visit the site. During this period the Muslim cemetery was expanded.

Israeli control

Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, Ш§Щ„ЩҶЩғШіШ©, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 ArabвҖ“Israeli War or Third ArabвҖ“Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab states (primarily Egypt, Syria, and Jordan) from 5 to 10 Ju ...

in 1967, Israel occupied of the West Bank

The West Bank ( ar, Ш§Щ„Ш¶ЩҒШ© Ш§Щ„ШәШұШЁЩҠШ©, translit=aбёҚ-бёҢiffah al-Д arbiyyah; he, Ч”Ч’Ч“Ч” Ч”ЧһЧўЧЁЧ‘ЧҷЧӘ, translit=HaGadah HaMaКҪaravit, also referred to by some Israelis as ) is a landlocked territory near the coast of the Mediter ...

, which included the tomb. The tomb was placed under Israeli military administration. Prime minister Levi Eshkol

Levi Eshkol ( he, ЧңЦөЧ•ЦҙЧҷ ЧҗЦ¶Ч©Ц°ЧҒЧӣЦјЧ•Ц№Чң ; 25 October 1895 вҖ“ 26 February 1969), born Levi Yitzhak Shkolnik ( he, ЧңЧ•Чҷ ЧҷЧҰЧ—Ч§ Ч©Ч§Ч•ЧңЧ ЧҷЧ§, links=no), was an Israeli statesman who served as the third Prime Minister of Israe ...

instructed that the tomb be included within the new expanded municipal borders of Jerusalem, but citing security concerns, Moshe Dayan decided not to include it within the territory that was annexed to Jerusalem.BenveniЕӣtГ®, MГӘrГҙnSon of the Cypresses: Memories, Reflections, and Regrets from a Political Life

University of California Press, 2007, pp. 44вҖ“45. Islamic crescents, inscribed into the rooms of the structure, were subsequently erased. Muslims were prevented from using the mosque, although they were allowed to use the cemetery for a while. Starting in 1993, Muslims were barred from using the cemetery. According to Bethlehem University, " cess to Rachel's Tomb is now restricted to tourists entering from Israel."

Oslo negotiations: Area A and Special Security Arrangement

The Oslo II Accord of September 28, 1995 placed Rachel's Tomb in a Palestinian enclave (Area A), with a special arrangement making it вҖ“ together with the main Jerusalem-Bethlehem access road вҖ“ subject to the security responsibility of Israel. Initially the arrangement was intended to be the same as that forJoseph's Tomb

Joseph's Tomb ( he, Ч§Ч‘ЧЁ ЧҷЧ•ЧЎЧЈ, ''Qever Yosef''; ar, ЩӮШЁШұ ЩҠЩҲШіЩҒ, ''Qabr YЕ«suf'') is a funerary monument located in Balata village at the eastern entrance to the valley that separates Mounts Gerizim and Ebal, 300 metres northwest of ...

near Nablus; however this was reconsidered following a significant reaction from IsraelвҖҷs right-wing religious parties. With the explicit intention of creating facts on the ground

Facts on the ground is a diplomatic and geopolitical term that means the situation in reality as opposed to in the abstract.

The term was popularised in the 1970s in discussions of the IsraeliвҖ“Palestinian conflict to refer to Israeli settlement ...

, in July 1995 MK Hanan Porat

Hanan Porat ( he, Ч—Ч Чҹ ЧӨЧ•ЧЁЧӘ, 5 December 1943 вҖ“ 4 October 2011) was an Israeli Orthodox rabbi, educator, and politician who served as a member of the Knesset for Tehiya, the National Religious Party, Tkuma, and the National Union betwee ...

established a yeshiva

A yeshiva (; he, ЧҷЧ©ЧҷЧ‘Ч”, , sitting; pl. , or ) is a traditional Jewish educational institution focused on the study of Rabbinic literature, primarily the Talmud and halacha (Jewish law), while Torah and Jewish philosophy are st ...

at the tomb, and right-wing activists began trying to acquire land around the tomb to create contiguity with Israeli-annexed areas of Jerusalem. On 17 July 1995, following a meeting of RabinвҖҷs cabinet and security forces, the Israeli position was changed to demand that an Israeli force provide security at the tomb and control the access road to it. When this demand was put to Yasser Arafat

Mohammed Abdel Rahman Abdel Raouf al-Qudwa al-Husseini (4 / 24 August 1929 вҖ“ 11 November 2004), popularly known as Yasser Arafat ( , ; ar, Щ…ШӯЩ…ШҜ ЩҠШ§ШіШұ Ш№ШЁШҜ Ш§Щ„ШұШӯЩ…ЩҶ Ш№ШЁШҜ Ш§Щ„ШұШӨЩҲЩҒ Ш№ШұЩҒШ§ШӘ Ш§Щ„ЩӮШҜЩҲШ© Ш§Щ„ШӯШіЩҠЩҶЩҠ, Mu ...

during the negotations, he is said to have responded:

The Palestinians were also strongly against conceding control of the road linking Bethlehem to Jerusalem, but ultimately conceded in order not to threaten the overall accords.

On December 1, 1995, the rest of Bethlehem, with the sole exception of the tomb enclave, passed under the full control of the Palestinian Authority.

Fortification

.

In 1996, Israel began an 18-month fortification of the site at a cost of $2m. It included a wall and adjacent military post.

After an attack on

.

In 1996, Israel began an 18-month fortification of the site at a cost of $2m. It included a wall and adjacent military post.

After an attack on Joseph's Tomb

Joseph's Tomb ( he, Ч§Ч‘ЧЁ ЧҷЧ•ЧЎЧЈ, ''Qever Yosef''; ar, ЩӮШЁШұ ЩҠЩҲШіЩҒ, ''Qabr YЕ«suf'') is a funerary monument located in Balata village at the eastern entrance to the valley that separates Mounts Gerizim and Ebal, 300 metres northwest of ...

and its subsequent takeover and desecration by Arabs, hundreds of residents of Bethlehem and the Aida refugee camp, led by the Palestinian Authority-appointed governor of Bethlehem, Muhammad Rashad al-Jabari, attacked Rachel's Tomb. They set the scaffolding that had been erected around it on fire and tried to break in. The IDF dispersed the mob with gunfire and stun grenade

A stun grenade, also known as a flash grenade, flashbang, thunderflash, or sound bomb, is a less-lethal explosive device used to temporarily disorient an enemy's senses. Upon detonation, they produce a blinding flash of light and an extremely lo ...

s, and dozens were wounded. In the following years, the Israeli-controlled site became a flashpoint between young Palestinians who hurled stones, bottles and firebombs and IDF troops, who responded with tear gas and rubber bullets.

At the end of 2000, when the Second Intifada broke out, the tomb came under attack for 41 days. In May 2001, fifty Jews found themselves trapped inside by a firefight between the IDF and Palestinian Authority gunmen. In March 2002 the IDF returned to Bethlehem as part of Operation Defensive Shield and remained there for an extended period of time.

On 11 September 2002, the Israeli security cabinet approved incorporating the tomb on the Israeli side of the West Bank barrier and surrounded by a concrete wall and watchtowers. This has been described as "de facto annexing it to Jerusalem." In February 2005, the

At the end of 2000, when the Second Intifada broke out, the tomb came under attack for 41 days. In May 2001, fifty Jews found themselves trapped inside by a firefight between the IDF and Palestinian Authority gunmen. In March 2002 the IDF returned to Bethlehem as part of Operation Defensive Shield and remained there for an extended period of time.

On 11 September 2002, the Israeli security cabinet approved incorporating the tomb on the Israeli side of the West Bank barrier and surrounded by a concrete wall and watchtowers. This has been described as "de facto annexing it to Jerusalem." In February 2005, the Israel Supreme Court

ar, Ш§Щ„Щ…ШӯЩғЩ…Ш© Ш§Щ„Ш№Щ„ЩҠШ§

, image = Emblem of Israel dark blue full.svg

, imagesize = 100px

, caption = Emblem of Israel

, motto =

, established =

, location = Givat Ram, Jerusalem

, coordinat ...

rejected a Palestinian appeal to change the route of the barrier in the region of the tomb. Israeli construction destroyed the Palestinian neighbourhood of ''Qubbet Rahil'' (Tomb of Rachel), which comprised 11% of metropolitan Bethlehem. Israel also declared the area to be a part of Jerusalem. From 2011, a "Wall Museum" was created by Palestinians on the North wall of the Israeli separation barrier surrounding Rachel's tomb.

In February 2010, Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu announced that the tomb would become a part of the national Jewish heritage sites rehabilitation plan. The decision was opposed by the Palestinian Authority, who saw it as a political decision associated with Israel's settlement project. The UN's special coordinator for the Middle East, Robert Serry, issued a statement of concern over the move, saying that the site is in Palestinian territory and has significance in both Judaism and Islam. The Jordanian government said that the move would derail peace efforts in the Middle East and condemned "unilateral Israeli measures which affect holy places and offend sentiments of Muslims throughout the world". UNESCO urged Israel to remove the site from its heritage list, stating that it was "an integral part of the occupied Palestinian territories". A resolution was passed at UNESCO that acknowledged both the Jewish and Islamic significance of the site, describing the site as both Bilal ibn Rabah Mosque and as Rachel's Tomb. The resolution passed with 44 countries supporting it, twelve countries abstaining, and only the United States voting to oppose. Also writing in the ''Jerusalem Post'', Larry Derfner defended the UNESCO position. He pointed out that UNESCO had explicitly recognized the Jewish connection to the site, having only denounced Israeli claims of sovereignty, while also acknowledging the Islamic and Christian significance of the site. The Israeli Prime Minister's Office criticised the resolution, claiming that: "the attempt to detach the Nation of Israel from its heritage is absurd. ... If the nearly 4,000-year-old burial sites of the Patriarchs and Matriarchs of the Jewish Nation вҖ“ Abraham

Abraham, ; ar, , , name=, group= (originally Abram) is the common Hebrew patriarch of the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In Judaism, he is the founding father of the special relationship between the Je ...

, Isaac

Isaac; grc, бјёПғОұО¬Оә, IsaГЎk; ar, ШҘШіШӯЩ°ЩӮ/ШҘШіШӯШ§ЩӮ, IsбёҘДҒq; am, бӢӯбҲөбҲҗбү… is one of the three patriarchs of the Israelites and an important figure in the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. He was th ...

, Jacob

Jacob (; ; ar, ЩҠЩҺШ№Щ’ЩӮЩҸЩҲШЁ, YaКҝqЕ«b; gr, бјёОұОәПҺОІ, Iakṓb), later given the name Israel, is regarded as a patriarch of the Israelites and is an important figure in Abrahamic religions, such as Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. J ...

, Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel and Leah

Leah ''La'ya;'' from (; ) appears in the Hebrew Bible as one of the two wives of the Biblical patriarch Jacob. Leah was Jacob's first wife, and the older sister of his second (and favored) wife Rachel. She is the mother of Jacob's first son ...

вҖ“ are not part of its culture and tradition, then what is a national cultural site?"PM insists Rachel's Tomb is heritage siteYnet, 10/29/2010

Jewish religious significance

Rabbinic traditions

In Jewish lore, Rachel passed away on 11 Cheshvan 1553 BCE. * According to theMidrash

''Midrash'' (;"midrash"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. he, ЧһЦҙЧ“Ц°ЧЁЦёЧ©ЧҒ; ...

, the first person to pray at Rachel's tomb was her eldest son, ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. he, ЧһЦҙЧ“Ц°ЧЁЦёЧ©ЧҒ; ...

Joseph

Joseph is a common male given name, derived from the Hebrew Yosef (ЧҷЧ•Ц№ЧЎЦөЧЈ). "Joseph" is used, along with "Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the mo ...

. While he was being carried away to Egypt after his brothers had sold him into slavery, he broke away from his captors and ran to his mother's grave. He threw himself upon the ground, wept aloud and cried "Mother! mother! Wake up. Arise and see my suffering." He heard his mother respond: "Do not fear. Go with them, and God will be with you."

* A number of reasons are given why Rachel was buried by the road side and not in the Cave of Machpela with the other Patriarchs and Matriarchs:

** Jacob foresaw that following the destruction of the First Temple

Solomon's Temple, also known as the First Temple (, , ), was the Temple in Jerusalem between the 10th century BC and . According to the Hebrew Bible, it was commissioned by Solomon in the United Kingdom of Israel before being inherited by th ...

the Jews would be exiled to Babylon. They would cry out as they passed her grave, and be comforted by her. She would intercede on their behalf, asking for mercy from God who would hear her prayer.

** Although Rachel was buried within the boundaries of the Holy Land, she was not buried in the Cave of Machpelah due to her sudden and unexpected death. Jacob, looking after his children and herds of cattle, simply did not have the opportunity to embalm her body to allow for the slow journey to Hebron.Ramban. Genesis, Volume 2. Mesorah Publications Ltd, 2005. pp. 545вҖ“47.

** Jacob was intent on not burying Rachel at Hebron, as he wished to prevent himself feeling ashamed before his forefathers, lest it appear he still regarded both sisters as his wives вҖ“ a biblically forbidden union.

* According to the mystical work, Zohar, when the Messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of '' mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach ...

appears, he will lead the dispersed Jews back to the Land of Israel, along the road which passes Rachel's grave.

Location

Early Jewish scholars noticed an apparent contradiction in the Bible with regards to the location of Rachel's grave. In Genesis, the Bible states that Rachel was buried "on the way to Ephrath, which is Bethlehem." Yet a reference to her tomb in Samuel states: "When you go from me today, you will find two men by Rachel's tomb, in the border of Benjamin, in Zelzah" (1 Sam 10:2).Rashi

Shlomo Yitzchaki ( he, ЧЁЧ‘Чҷ Ч©ЧңЧһЧ” ЧҷЧҰЧ—Ч§Чҷ; la, Salomon Isaacides; french: Salomon de Troyes, 22 February 1040 вҖ“ 13 July 1105), today generally known by the acronym Rashi (see below), was a medieval French rabbi and author of a compre ...

asks: "Now, isn't Rachel's tomb in the border of Judah, in Bethlehem?" He explains that the verse rather means: "Now they are by Rachel's tomb, and when you will meet them, you will find them in the border of Benjamin, in Zelzah." Similarly, Ramban assumes that the site shown today near Bethlehem reflects an authentic tradition. After he had arrived in Jerusalem and seen "with his own eyes" that Rachel's tomb was on the outskirts of Bethlehem, he retracted his original understanding of her tomb being located north of Jerusalem and concluded that the reference in Jeremiah

Jeremiah, Modern: , Tiberian: ; el, бјёОөПҒОөОјОҜОұПӮ, IeremГӯДҒs; meaning " Yah shall raise" (c. 650 вҖ“ c. 570 BC), also called Jeremias or the "weeping prophet", was one of the major prophets of the Hebrew Bible. According to Jewi ...

(Jer 31:15) which seemed to place her burial place in Ramah Ramah may refer to:

In ancient Israel

* Ramathaim-Zophim, the birthplace of Samuel

* Ramoth-Gilead, a Levite city of refuge

* Ramah in Benjamin, mentioned in the Book of Jeremiah and also in the Gospel of Matthew

* Baalath-Beer, also known as Ramo ...

, is to be understood allegorically. There remains however, a dispute as to whether her tomb near Bethlehem was in the tribal territory of Judah, or of her son Benjamin.

Customs

A Jewish tradition teaches that Rachel weeps for her children and that when the Jews were taken into exile, she wept as they passed by her grave on the way to Babylonia. Jews have made pilgrimage to the tomb since ancient times. There is a tradition regarding the key that unlocked the door to the tomb. The key was about long and made of brass. Thebeadle

A beadle, sometimes spelled bedel, is an official of a church or synagogue who may usher, keep order, make reports, and assist in religious functions; or a minor official who carries out various civil, educational, or ceremonial duties on the ...

kept it with him at all times, and it was not uncommon that someone would knock at his door in the middle of the night requesting it to ease the labor pains of an expectant mother. The key was placed under her pillow and almost immediately, the pains would subside and the delivery would take place peacefully.

Till this day there is an ancient tradition regarding a ''segulah'' or charm which is the most famous women's ritual at the tomb. Sered, "Rachel's Tomb and the Milk Grotto of the Virgin Mary: Two Women's Shrines in Bethlehem", ''Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion'', vol 2, 1986, pp. 7вҖ“22. A red string is tied around the tomb seven times then worn as a charm for fertility. This use of the string is comparatively recent, though there is a report of its use to ward off diseases in the 1880s. Sered, "Rachel's Tomb: The Development of a Cult", ''Jewish Studies Quarterly'', vol 2, 1995, pp. 103вҖ“48.

The Torah Ark

A Torah ark (also known as the ''Heikhal'', or the ''Aron Kodesh'') refers to an ornamental chamber in the synagogue that houses the Torah scrolls.

History

The ark, also known as the ''ark of law'', or in Hebrew the ''Aron Kodesh'' or ''aron ha- ...

in Rachel's Tomb is covered with a curtain (Hebrew: ''parokhet'') made from the wedding gown of Nava Applebaum, a young Israeli woman who was killed by a Palestinian terrorist in a suicide bombing at CafГ© Hillel in Jerusalem in 2003, on the eve of her wedding.

Connection to Bilal ibn Rabah

Palestinian sources have stated that the structure was in fact a mosque built at the time of the Arab conquest in honour of Bilal ibn Rabah, anEthiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, бҠўбүөбӢ®бҢөбӢ«, ГҚtiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

n known in Islamic history as the first muezzin

The muezzin ( ar, Щ…ЩҸШӨЩҺШ°ЩҗЩ‘ЩҶ) is the person who proclaims the call to the daily prayer ( б№ЈalДҒt) five times a day ( Fajr prayer, Zuhr prayer, Asr prayer, Maghrib prayer and Isha prayer) at a mosque. The muezzin plays an important r ...

.

Replicas

Moses Montefiore

Sir Moses Haim Montefiore, 1st Baronet, (24 October 1784 вҖ“ 28 July 1885) was a British financier and banker, activist, philanthropist and Sheriff of London. Born to an Italian Sephardic Jewish family based in London, aft ...

, adjacent to the Montefiore synagogue in Ramsgate, England, is a replica of Rachel's Tomb.

In 1934, the Michigan Memorial Park planned to reproduce the tomb. When built, it was used to house the sound system and pipe organ used during funerals, but it has since been demolished.

See also

*List of National Heritage Sites of Israel

List of National Heritage Sites of Israel, as designated by the Cabinet of Israel, government of the State of Israel:

*Atlit detainee camp, Atlit: Detention center for Aliyah Bet, Jewish immigrants seeking refuge in Palestine (region), Palestine d ...

Gallery

North-east perspective

Sebil

A sebil or sabil ( ar, ШіШЁЩҠЩ„, sabД«l ; Turkish: ''sebil'') is a small kiosk in the Islamic architectural tradition where water is freely dispensed to members of the public by an attendant behind a grilled window. The term is sometimes also ...

s (now inside the expanded compound)

File:Fortified entrance road to Kever Rachel in Jerusalem, West Bank.jpg, 2011

North perspective

West perspective

East perspective

South perspective

South-east perspective

References

Bibliography

* Bowman, Glenn W. 2014. вSharing and Exclusion: The Case of Rachel's Tomb

Җқ Jerusalem Quarterly 58 (July): 30вҖ“49. * * * * * * * Gitlitz, David M. & Linda Kay Davidson. вҖңPilgrimage and the JewsвҖҷвҖҷ (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2006). * * * * Pullan, W. (2013). Bible and Gun: Militarism in Jerusalem's Holy Places. Space and Polity, 17 (3), 335вҖ“56, dx.doi.org/10.1080/13562576.2013.853490 * Selwyn, T. (2009) Ghettoizing a matriarch and a city: An everyday story from the Palestinian/Israeli borderlands, Journal of Borderlands Studies, 24(3), pp. 39вҖ“ 55 *

p. 177

ff) * * UNESCO (19 March 2010), 184 EX/37

The Two Palestinian Sites of Al-Haram Al-Ibrahimi/Tomb of the Patriarchs in Al-Khalil/Hebron and the Bilal bin Rabah Mosques/Rachael's Tomb in Bethlehem

Fact Sheet on Israeli Consolidation of Palestinian Heritage Sites in the Occupied Palestinian Territory: The Case if Hebron and Bethlehem *

External links

Rachel's Tomb Website

General Info., History, Pictures, Video, Visitor Info., Transportation

Is this Rachel's Tomb? A geographical and historical review

A site dedicated to Rachel's Tomb

* Survey of Western Palestine, Map 17:

IAA

Wikimedia commons

Wikimedia Commons (or simply Commons) is a media repository of free-to-use images, sounds, videos and other media. It is a project of the Wikimedia Foundation.

Files from Wikimedia Commons can be used across all of the Wikimedia projects in ...

{{Authority control

Bethlehem

Torah places

Jewish mausoleums

Synagogues in the West Bank

Tombs of biblical people

Jewish pilgrimage sites

Women and death

Status quo holy places

Mosques in Bethlehem

Tombs in the State of Palestine