RMS Lusitania on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

RMS ''Lusitania'' (named after the Roman province in Western Europe corresponding to modern Portugal) was a British ocean liner that was launched by the Cunard Line in 1906 and that held the

''Lusitania'' and were commissioned by

''Lusitania'' and were commissioned by

Cunard established a committee to decide upon the design for the new ships, of which James Bain, Cunard's Marine Superintendent was the chairman. Other members included Rear Admiral H. J. Oram, who had been involved in designs for

Cunard established a committee to decide upon the design for the new ships, of which James Bain, Cunard's Marine Superintendent was the chairman. Other members included Rear Admiral H. J. Oram, who had been involved in designs for  Peskett had built a large model of the proposed ship in 1902 showing a three-funnel design. A fourth funnel was implemented into the design in 1904 as it was necessary to vent the exhaust from additional boilers fitted after steam turbines had been settled on as the power plant. The original plan called for three propellers, but this was altered to four because it was felt the necessary power could not be transmitted through just three. Four turbines would drive four separate propellers, with additional reversing turbines to drive the two inboard shafts only. To improve efficiency, the two inboard propellers rotated inward, while those outboard rotated outward. The outboard turbines operated at high pressure; the exhaust steam then passing to those inboard at relatively low pressure.

The propellers were driven directly by the turbines, for sufficiently robust gearboxes had not yet been developed, and became available in only 1916. Instead, the turbines had to be designed to run at a much lower speed than those normally accepted as being optimum. Thus, the efficiency of the turbines installed was less at low speeds than a conventional

Peskett had built a large model of the proposed ship in 1902 showing a three-funnel design. A fourth funnel was implemented into the design in 1904 as it was necessary to vent the exhaust from additional boilers fitted after steam turbines had been settled on as the power plant. The original plan called for three propellers, but this was altered to four because it was felt the necessary power could not be transmitted through just three. Four turbines would drive four separate propellers, with additional reversing turbines to drive the two inboard shafts only. To improve efficiency, the two inboard propellers rotated inward, while those outboard rotated outward. The outboard turbines operated at high pressure; the exhaust steam then passing to those inboard at relatively low pressure.

The propellers were driven directly by the turbines, for sufficiently robust gearboxes had not yet been developed, and became available in only 1916. Instead, the turbines had to be designed to run at a much lower speed than those normally accepted as being optimum. Thus, the efficiency of the turbines installed was less at low speeds than a conventional  Work to refine the hull shape was conducted in the

Work to refine the hull shape was conducted in the

At the time of their introduction onto the North Atlantic, both ''Lusitania'' and ''Mauretania'' possessed among the most luxurious, spacious and comfortable interiors afloat. The Scottish architect James Miller was chosen to design ''Lusitania''s interiors, while Harold Peto was chosen to design ''Mauretania''. Miller chose to use plasterwork to create interiors whereas Peto made extensive use of wooden panelling, with the result that the overall impression given by ''Lusitania'' was brighter than ''Mauretania''.

The ship's passenger accommodation was spread across six decks; from the top deck down to the waterline they were Boat Deck (A Deck), the Promenade Deck (B Deck), the Shelter Deck (C Deck), the Upper Deck (D Deck), the Main Deck (E Deck) and the Lower Deck (F Deck), with each of the three passenger classes being allotted their own space on the ship. As seen aboard all passenger liners of the era, first-, second- and third-class passengers were strictly segregated from one another. According to her original configuration in 1907, she was designed to carry 2,198 passengers and 827 crew members. The Cunard Line prided itself with a record for passenger satisfaction.

At the time of their introduction onto the North Atlantic, both ''Lusitania'' and ''Mauretania'' possessed among the most luxurious, spacious and comfortable interiors afloat. The Scottish architect James Miller was chosen to design ''Lusitania''s interiors, while Harold Peto was chosen to design ''Mauretania''. Miller chose to use plasterwork to create interiors whereas Peto made extensive use of wooden panelling, with the result that the overall impression given by ''Lusitania'' was brighter than ''Mauretania''.

The ship's passenger accommodation was spread across six decks; from the top deck down to the waterline they were Boat Deck (A Deck), the Promenade Deck (B Deck), the Shelter Deck (C Deck), the Upper Deck (D Deck), the Main Deck (E Deck) and the Lower Deck (F Deck), with each of the three passenger classes being allotted their own space on the ship. As seen aboard all passenger liners of the era, first-, second- and third-class passengers were strictly segregated from one another. According to her original configuration in 1907, she was designed to carry 2,198 passengers and 827 crew members. The Cunard Line prided itself with a record for passenger satisfaction.

''Lusitania''s first-class accommodation was in the centre section of the ship on the five uppermost decks, mostly concentrated between the first and fourth funnels. When fully booked, ''Lusitania'' could cater to 552 first-class passengers. In common with all major liners of the period, ''Lusitania''s first-class interiors were decorated with a mélange of historical styles. The first-class dining saloon was the grandest of the ship's public rooms; arranged over two decks with an open circular well at its centre and crowned by an elaborate dome measuring , decorated with frescos in the style of François Boucher, it was elegantly realised throughout in the neoclassical

''Lusitania''s first-class accommodation was in the centre section of the ship on the five uppermost decks, mostly concentrated between the first and fourth funnels. When fully booked, ''Lusitania'' could cater to 552 first-class passengers. In common with all major liners of the period, ''Lusitania''s first-class interiors were decorated with a mélange of historical styles. The first-class dining saloon was the grandest of the ship's public rooms; arranged over two decks with an open circular well at its centre and crowned by an elaborate dome measuring , decorated with frescos in the style of François Boucher, it was elegantly realised throughout in the neoclassical

All other first-class public rooms were situated on the boat deck and comprised a lounge, reading and writing room, smoking room and veranda café. The last was an innovation on a Cunard liner and, in warm weather, one side of the café could be opened up to give the impression of sitting outdoors. This would have been a rarely used feature given the often inclement weather of the North Atlantic.

The first-class lounge was decorated in Georgian style with inlaid mahogany panels surrounding a jade green carpet with a yellow floral pattern, measuring overall . It had a barrel vaulted skylight rising to with stained glass windows each representing one month of the year.

All other first-class public rooms were situated on the boat deck and comprised a lounge, reading and writing room, smoking room and veranda café. The last was an innovation on a Cunard liner and, in warm weather, one side of the café could be opened up to give the impression of sitting outdoors. This would have been a rarely used feature given the often inclement weather of the North Atlantic.

The first-class lounge was decorated in Georgian style with inlaid mahogany panels surrounding a jade green carpet with a yellow floral pattern, measuring overall . It had a barrel vaulted skylight rising to with stained glass windows each representing one month of the year.

Each end of the lounge had a high green marble fireplace incorporating enamelled panels by Alexander Fisher. The design was linked overall with decorative plasterwork. The library walls were decorated with carved pilasters and mouldings marking out panels of grey and cream silk brocade. The carpet was rose, with Rose du Barry silk curtains and upholstery. The chairs and writing desks were

Each end of the lounge had a high green marble fireplace incorporating enamelled panels by Alexander Fisher. The design was linked overall with decorative plasterwork. The library walls were decorated with carved pilasters and mouldings marking out panels of grey and cream silk brocade. The carpet was rose, with Rose du Barry silk curtains and upholstery. The chairs and writing desks were

''Lusitania''s

''Lusitania''s

The vessels of the ''Olympic'' class also differed from ''Lusitania'' and ''Mauretania'' in the way in which they were compartmented below the waterline. The White Star vessels were divided by transverse watertight bulkheads. While ''Lusitania'' also had transverse bulkheads, it also had longitudinal bulkheads running along the ship on each side, between the boiler and engine rooms and the coal bunkers on the outside of the vessel. The British commission that had investigated the sinking of ''Titanic'' in 1912 heard testimony on the flooding of coal bunkers lying outside longitudinal bulkheads. Being of considerable length, when flooded, these could increase the ship's list and "make the lowering of the boats on the other side impracticable"—and this was precisely what later happened with ''Lusitania''. The ship's stability was insufficient for the bulkhead arrangement used: flooding of only three coal bunkers on one side could result in negative metacentric height. On the other hand, ''Titanic'' was given ample stability and sank with only a few degrees list, the design being such that there was very little risk of unequal flooding and possible capsize.

''Lusitania'' did not carry enough lifeboats for all her passengers, officers and crew on board at the time of her maiden voyage (carrying four lifeboats fewer than ''Titanic'' would carry in 1912). This was a common practice for large passenger ships at the time, since the belief was that in busy shipping lanes help would always be nearby and the few boats available would be adequate to ferry all aboard to rescue ships before a sinking. After the ''Titanic'' sank, ''Lusitania'' and ''Mauretania'' were equipped with an additional six clinker-built wooden boats under davits, making for a total of 22 boats rigged in davits. The rest of their lifeboat accommodations were supplemented with 26 collapsible lifeboats, 18 stored directly beneath the regular lifeboats and eight on the after deck. The collapsibles were built with hollow wooden bottoms and canvas sides, and needed assembly in the event they had to be used.

This contrasted with ''Olympic'' and which received a full complement of lifeboats all rigged under davits. This difference would have been a major contributor to the high loss of life involved with ''Lusitania''s sinking, since there was not sufficient time to assemble collapsible boats or life-rafts, had it not been for the fact that the ship's severe listing made it impossible for lifeboats on the port side of the vessel to be lowered, and the rapidity of the sinking did not allow the remaining lifeboats that could be directly lowered (as these were rigged under davits) to be filled and launched with passengers. When ''Britannic'', working as a hospital ship during

The vessels of the ''Olympic'' class also differed from ''Lusitania'' and ''Mauretania'' in the way in which they were compartmented below the waterline. The White Star vessels were divided by transverse watertight bulkheads. While ''Lusitania'' also had transverse bulkheads, it also had longitudinal bulkheads running along the ship on each side, between the boiler and engine rooms and the coal bunkers on the outside of the vessel. The British commission that had investigated the sinking of ''Titanic'' in 1912 heard testimony on the flooding of coal bunkers lying outside longitudinal bulkheads. Being of considerable length, when flooded, these could increase the ship's list and "make the lowering of the boats on the other side impracticable"—and this was precisely what later happened with ''Lusitania''. The ship's stability was insufficient for the bulkhead arrangement used: flooding of only three coal bunkers on one side could result in negative metacentric height. On the other hand, ''Titanic'' was given ample stability and sank with only a few degrees list, the design being such that there was very little risk of unequal flooding and possible capsize.

''Lusitania'' did not carry enough lifeboats for all her passengers, officers and crew on board at the time of her maiden voyage (carrying four lifeboats fewer than ''Titanic'' would carry in 1912). This was a common practice for large passenger ships at the time, since the belief was that in busy shipping lanes help would always be nearby and the few boats available would be adequate to ferry all aboard to rescue ships before a sinking. After the ''Titanic'' sank, ''Lusitania'' and ''Mauretania'' were equipped with an additional six clinker-built wooden boats under davits, making for a total of 22 boats rigged in davits. The rest of their lifeboat accommodations were supplemented with 26 collapsible lifeboats, 18 stored directly beneath the regular lifeboats and eight on the after deck. The collapsibles were built with hollow wooden bottoms and canvas sides, and needed assembly in the event they had to be used.

This contrasted with ''Olympic'' and which received a full complement of lifeboats all rigged under davits. This difference would have been a major contributor to the high loss of life involved with ''Lusitania''s sinking, since there was not sufficient time to assemble collapsible boats or life-rafts, had it not been for the fact that the ship's severe listing made it impossible for lifeboats on the port side of the vessel to be lowered, and the rapidity of the sinking did not allow the remaining lifeboats that could be directly lowered (as these were rigged under davits) to be filled and launched with passengers. When ''Britannic'', working as a hospital ship during

''Lusitania'', commanded by Commodore James Watt, moored at the

''Lusitania'', commanded by Commodore James Watt, moored at the

''Lusitania'' and other ships participated in the Hudson-Fulton Celebration in New York City from the end of September to early October 1909. The celebration was also a display of the different modes of transportation then in existence, ''Lusitania'' representing the newest advancement in steamship technology. A newer mode of travel was the

''Lusitania'' and other ships participated in the Hudson-Fulton Celebration in New York City from the end of September to early October 1909. The celebration was also a display of the different modes of transportation then in existence, ''Lusitania'' representing the newest advancement in steamship technology. A newer mode of travel was the

Many of the large liners were laid up in 1914–1915, in part due to falling demand for passenger travel across the Atlantic, and in part to protect them from damage due to mines or other dangers. Among the most recognisable of these liners, some were eventually used as troop transports, while others became hospital ships. ''Lusitania'' remained in commercial service; although bookings aboard her were by no means strong during that autumn and winter, demand was strong enough to keep her in civilian service. Economising measures were taken. One of these was the shutting down of her No. 4 boiler room to conserve coal and crew costs; this reduced her maximum speed from over to . With apparent dangers evaporating, the ship's disguised paint scheme was also dropped and she was returned to civilian colours. Her name was picked out in gilt, her funnels were repainted in their normal Cunard livery, and her superstructure was painted white again. One alteration was the addition of a bronze/gold-coloured band around the base of the superstructure just above the black paint.

Many of the large liners were laid up in 1914–1915, in part due to falling demand for passenger travel across the Atlantic, and in part to protect them from damage due to mines or other dangers. Among the most recognisable of these liners, some were eventually used as troop transports, while others became hospital ships. ''Lusitania'' remained in commercial service; although bookings aboard her were by no means strong during that autumn and winter, demand was strong enough to keep her in civilian service. Economising measures were taken. One of these was the shutting down of her No. 4 boiler room to conserve coal and crew costs; this reduced her maximum speed from over to . With apparent dangers evaporating, the ship's disguised paint scheme was also dropped and she was returned to civilian colours. Her name was picked out in gilt, her funnels were repainted in their normal Cunard livery, and her superstructure was painted white again. One alteration was the addition of a bronze/gold-coloured band around the base of the superstructure just above the black paint.

By early 1915, a new threat began to materialise: submarines. At first, they were used by the Germans only to attack naval vessels, something they achieved only occasionally but sometimes with spectacular success. Then the U-boats began to attack merchant vessels at times, although almost always in accordance with the old

By early 1915, a new threat began to materialise: submarines. At first, they were used by the Germans only to attack naval vessels, something they achieved only occasionally but sometimes with spectacular success. Then the U-boats began to attack merchant vessels at times, although almost always in accordance with the old  This warning was printed adjacent to an advertisement for ''Lusitania''s return voyage which led to many interpreting this as a direct message to the ''Lusitania''. The ship departed

This warning was printed adjacent to an advertisement for ''Lusitania''s return voyage which led to many interpreting this as a direct message to the ''Lusitania''. The ship departed

The sinking caused an international outcry, especially in Britain and across the

The sinking caused an international outcry, especially in Britain and across the

The wreck of ''Lusitania'' was located on 6 October 1935, south of the lighthouse at

The wreck of ''Lusitania'' was located on 6 October 1935, south of the lighthouse at

In 1935 a Glasgow-based expedition was launched to try and find the wreck of ''Lusitania''. The Argonaut Corporation Ltd was founded and the salvage ship ''

In 1935 a Glasgow-based expedition was launched to try and find the wreck of ''Lusitania''. The Argonaut Corporation Ltd was founded and the salvage ship ''

online

* *

* ttps://www.pbs.org/lostliners/lusitania.html RMS ''Lusitania'' Public Broadcasting Service (PBS)

''Lusitania'' pictures: Construction, engine, and interior photos; disaster and wreck illustrations'

– BigBadBattleships.com

''Sinking of the Lusitania'' (1918)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Lusitania Conflicts in 1915 Ships built on the River Clyde Ships of Scotland Ships sunk by German submarines in World War I World War I shipwrecks in the Atlantic Ocean Blue Riband holders Passenger ships of the United Kingdom Four funnel liners 1906 ships Shipwrecks of Ireland Maritime incidents in Ireland Maritime incidents in 1915 Conspiracy theories

Blue Riband

The Blue Riband () is an unofficial accolade given to the passenger liner crossing the Atlantic Ocean in regular service with the record highest average speed. The term was borrowed from horse racing and was not widely used until after 1910. ...

appellation for the fastest Atlantic crossing in 1908. It was briefly the world's largest passenger ship until the completion of the three months later. She was sunk on her 202nd trans-Atlantic crossing, on 7 May 1915, by a German U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare ro ...

off the southern coast of Ireland, killing 1,198 passengers and crew.

The sinking occurred about two years before the United States declaration of war on Germany. Although the ''Lusitania''s sinking was a major factor in building American support for a war, war was eventually declared only after the Imperial German Government resumed the use of unrestricted submarine warfare against American shipping in an attempt to break the Transatlantic supply chain from the US to Britain, as well as after the Zimmermann Telegram.

German shipping lines were Cunard's main competitors for the custom of Transatlantic passengers in the early 20th century, and Cunard responded by building two new 'ocean greyhounds': the ''Lusitania'' and the '' Mauretania''. Cunard used assistance from the British Admiralty

The Admiralty was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom responsible for the command of the Royal Navy until 1964, historically under its titular head, the Lord High Admiral – one of the Great Officers of State. For much of i ...

to build both new ships, on the understanding that the ship would be available for military duty in time of war. During construction gun mounts for deck cannons were installed but no guns were ever fitted. Both the ''Lusitania'' and ''Mauretania'' were fitted with turbine engines that enabled them to maintain a service speed of . They were equipped with lifts, wireless telegraph, and electric light, and provided 50 percent more passenger space than any other ship; the first-class decks were known for their sumptuous furnishings.

The Royal Navy had blockaded Germany at the start of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

; the UK had declared the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian ...

a war zone in the autumn of 1914 and mined the approaches. In the spring of 1915, all food imports for Germany were declared contraband. In response Germany had declared the seas around the United Kingdom a war zone too, and German submarine warfare was intensifying in the Atlantic. When RMS ''Lusitania'' left New York for Britain on 1 May 1915 the German embassy in the United States placed fifty newspaper advertisements warning people of the dangers of sailing on ''Lusitania''. Objections were made by the British that threatening to torpedo all ships indiscriminately was wrong, whether it was announced in advance or not.

On the afternoon of 7 May, a German U-boat torpedoed ''Lusitania'' off the southern coast of Ireland inside the declared war zone. A second internal explosion caused her to sink in 18 minutes, killing 1,198 passengers and crew. The German government justified treating ''Lusitania'' as a naval vessel because she was carrying 173 tons of war munitions and ammunition, making her a legitimate military target, and they argued that British merchant ships had violated the cruiser rules

Cruiser rules is a colloquial phrase referring to the conventions regarding the attacking of a merchant ship by an armed vessel. Here ''cruiser'' is meant in its original meaning of a ship sent on an independent mission such as commerce raiding. ...

from the very beginning of the war. The internationally recognised cruiser rules were obsolete by 1915; it had become more dangerous for submarines to surface and give warning with the introduction of Q-ship

Q-ships, also known as Q-boats, decoy vessels, special service ships, or mystery ships, were heavily armed merchant ships with concealed weaponry, designed to lure submarines into making surface attacks. This gave Q-ships the chance to open f ...

s in 1915 by the Royal Navy, which were armed with concealed deck guns. The Germans argued that ''Lusitania'' was regularly transporting "war munitions"; she operated under the control of the Admiralty; she could be converted into an armed auxiliary cruiser to join the war; her identity had been disguised; and she flew no flags. They claimed that she was a non-neutral vessel in a declared war zone, with orders to evade capture and ram challenging submarines.

However, the ship was not armed for battle and was carrying hundreds of civilian passengers, and the British government accused the Germans of breaching the cruiser rules. The sinking caused a storm of protest in the United States because 128 American citizens were among the dead. The sinking shifted public opinion in the United States against Germany and was one of the factors in the declaration of war nearly two years later. After the First World War, successive British governments maintained that there were no munitions on board ''Lusitania'', and the Germans were not justified in treating the ship as a naval vessel. In 1982, the head of the Foreign Office's American department finally admitted that there is a large amount of ammunition in the wreck, some of which is highly dangerous and poses a safety risk to salvage teams.

Development and construction

''Lusitania'' and were commissioned by

''Lusitania'' and were commissioned by Cunard

Cunard () is a British shipping and cruise line based at Carnival House at Southampton, England, operated by Carnival UK and owned by Carnival Corporation & plc. Since 2011, Cunard and its three ships have been registered in Hamilton, Ber ...

, responding to increasing competition from rival transatlantic passenger companies, particularly the German Norddeutscher Lloyd

Norddeutscher Lloyd (NDL; North German Lloyd) was a German shipping company. It was founded by Hermann Henrich Meier and Eduard Crüsemann in Bremen on 20 February 1857. It developed into one of the most important German shipping companies of ...

(NDL) and Hamburg America Line (HAPAG). They had larger, faster, more modern and more luxurious ships than Cunard, and were better placed, starting from German ports, to capture the lucrative trade in emigrants leaving Europe for North America. The NDL liner captured the Blue Riband from Cunard's in 1897, before the prize was taken in 1900 by the HAPAG ship . NDL soon wrested the prize back in 1903 with the new and . Cunard saw its passenger numbers affected as a result of the so-called "s".

American millionaire businessman J. P. Morgan had decided to invest in transatlantic shipping by creating a new company, International Mercantile Marine

The International Mercantile Marine Company, originally the International Navigation Company, was a trust formed in the early twentieth century as an attempt by J.P. Morgan to monopolize the shipping trade.

IMM was founded by shipping magnates ...

(IMM), and, in 1901, purchased the British freight shipper Frederick Leyland & Co. and a controlling interest in the British passenger White Star Line

The White Star Line was a British shipping company. Founded out of the remains of a defunct packet company, it gradually rose up to become one of the most prominent shipping lines in the world, providing passenger and cargo services between ...

and folded them into IMM. In 1902, IMM, NDL and HAPAG entered into a "Community of Interest" to fix prices and divide among them the transatlantic trade. The partners also acquired a 51% stake in the Dutch Holland America Line

Holland America Line is an American-owned cruise line, a subsidiary of Carnival Corporation & plc headquartered in Seattle, Washington, United States.

Holland America Line was founded in Rotterdam, Netherlands, and from 1873 to 1989, it operated ...

. IMM made offers to purchase Cunard which, along with the French Compagnie Générale Transatlantique

The Compagnie Générale Transatlantique (CGT, and commonly named "Transat"), typically known overseas as the French Line, was a French shipping company. Established in 1855 by the Péreire brothers, brothers Émile and Issac Péreire under the ...

(CGT), was now its principal rival.

Cunard chairman Lord Inverclyde thus approached the British government for assistance. Faced with the impending collapse of the British liner fleet and the consequent loss of national prestige, as well as the reserve of shipping for war purposes which it represented, they agreed to help. By an agreement signed in June 1903, Cunard was given a loan of £2.6 million to finance two ships, repayable over 20 years at a favourable interest rate of 2.75%. The ships would receive an annual operating subsidy of £75,000 each plus a mail contract worth £68,000. In return, the ships would be built to Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

specifications so that they could be used as auxiliary cruisers in wartime.

Design

Cunard established a committee to decide upon the design for the new ships, of which James Bain, Cunard's Marine Superintendent was the chairman. Other members included Rear Admiral H. J. Oram, who had been involved in designs for

Cunard established a committee to decide upon the design for the new ships, of which James Bain, Cunard's Marine Superintendent was the chairman. Other members included Rear Admiral H. J. Oram, who had been involved in designs for steam turbine

A steam turbine is a machine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work on a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Charles Parsons in 1884. Fabrication of a modern steam tu ...

-powered ships for the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

, and Charles Parsons, whose company Parsons Marine was now producing turbine engines.

Parsons maintained that he could design engines capable of maintaining a speed of , which would require . The largest turbine sets built so far had been of for the battleship, and for -class battlecruisers, which meant the engines would be of a new, untested design. Turbines offered the advantages of generating less vibration than the reciprocating engines and greater reliability in operation at high speeds, combined with lower fuel consumption. Having initially turned down the use of this relatively untried type of engine, Cunard was persuaded by the Admiralty to set up a committee of marine professionals to look at its possible use on the new liners. The relative merits of turbines and reciprocating engines were investigated in a series of trials between Newhaven and Dieppe using the turbine-driven cross-Channel ferry Brighton and the similarity-designed Arundel, which had reciprocating engines. The Turbine Committee was convinced by these and other tests that turbines were the way forward and recommended on 24 March 1904 that they should be used on the new express liners. In order to gain some experience of these new engines, Cunard asked John Brown to fit turbines on , the second of a pair of 19,500g-intermediate liners under construction at the yard. ''Carmania'' was completed in 1905 and this gave Cunard almost two years of experience before the introduction of their new super liners in 1907.

The ship was designed by Leonard Peskett

Leonard Peskett, OBE (1861 – 1924) was the Cunard Line's Senior naval architect This is the top category for all articles related to architecture and its practitioners.

{{Commons category, Architecture occupations

Design occupations

Occup ...

and built by John Brown and Company of Clydebank, Scotland. The ship's name was taken from Lusitania

Lusitania (; ) was an ancient Iberian Roman province located where modern Portugal (south of the Douro river) and

a portion of western Spain (the present Extremadura and the province of Salamanca) lie. It was named after the Lusitani or Lu ...

, an ancient Roman province on the west of the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, def ...

—the region that is now southern Portugal and Extremadura (Spain). The name had also been used by a previous ship built in 1871 and wrecked in 1901, making the name available from Lloyd's for Cunard's giant.

Peskett had built a large model of the proposed ship in 1902 showing a three-funnel design. A fourth funnel was implemented into the design in 1904 as it was necessary to vent the exhaust from additional boilers fitted after steam turbines had been settled on as the power plant. The original plan called for three propellers, but this was altered to four because it was felt the necessary power could not be transmitted through just three. Four turbines would drive four separate propellers, with additional reversing turbines to drive the two inboard shafts only. To improve efficiency, the two inboard propellers rotated inward, while those outboard rotated outward. The outboard turbines operated at high pressure; the exhaust steam then passing to those inboard at relatively low pressure.

The propellers were driven directly by the turbines, for sufficiently robust gearboxes had not yet been developed, and became available in only 1916. Instead, the turbines had to be designed to run at a much lower speed than those normally accepted as being optimum. Thus, the efficiency of the turbines installed was less at low speeds than a conventional

Peskett had built a large model of the proposed ship in 1902 showing a three-funnel design. A fourth funnel was implemented into the design in 1904 as it was necessary to vent the exhaust from additional boilers fitted after steam turbines had been settled on as the power plant. The original plan called for three propellers, but this was altered to four because it was felt the necessary power could not be transmitted through just three. Four turbines would drive four separate propellers, with additional reversing turbines to drive the two inboard shafts only. To improve efficiency, the two inboard propellers rotated inward, while those outboard rotated outward. The outboard turbines operated at high pressure; the exhaust steam then passing to those inboard at relatively low pressure.

The propellers were driven directly by the turbines, for sufficiently robust gearboxes had not yet been developed, and became available in only 1916. Instead, the turbines had to be designed to run at a much lower speed than those normally accepted as being optimum. Thus, the efficiency of the turbines installed was less at low speeds than a conventional reciprocating steam engine

A reciprocating engine, also often known as a piston engine, is typically a heat engine that uses one or more reciprocating pistons to convert high temperature and high pressure into a rotating motion. This article describes the common featu ...

, but significantly better when the engines were run at high speed, as was usually the case for an express liner. The ship was fitted with 23 double-ended and two single-ended boilers (which fitted the forward space where the ship narrowed), operating at a maximum 195 psi and containing 192 individual furnaces.

Work to refine the hull shape was conducted in the

Work to refine the hull shape was conducted in the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

experimental tank at Haslar

Haslar is on the south coast of England, at the southern tip of Alverstoke, on the Gosport peninsula, Hampshire. It takes its name from the Old English , meaning " hazel-landing place". It may have been named after a bank of hazel strewn on ...

, Gosport. As a result of experiments, the beam of the ship was increased by over that initially intended to improve stability. The hull immediately in front of the rudder and the balanced rudder itself followed naval design practice to improve the vessel's turning response. The Admiralty contract required that all machinery be below the waterline, where it was considered to be better protected from gunfire, and the aft third of the ship below water was used to house the turbines, the steering motors and four steam-driven turbo-generators. The central half contained four boiler rooms, with the remaining space at the forward end of the ship being reserved for cargo and other storage.

Coal bunkers were placed along the length of the ship outboard of the boiler rooms, with a large transverse bunker immediately in front of that most forward (number 1) boiler room. Apart from convenience ready for use, the coal was considered to provide added protection for the central spaces against attack. At the very front were the chain lockers for the huge anchor chains and ballast tanks to adjust the ship's trim.

The hull space was divided into twelve watertight compartments, any two of which could be flooded without risk of the ship sinking, connected by 35 hydraulically operated watertight doors. A critical flaw in the arrangement of the watertight compartments was that sliding doors to the coal bunkers needed to be open to provide a constant feed of coal whilst the ship was operating, and closing these in emergency conditions could be problematic. The ship had a double bottom with the space between divided into separate watertight cells. The ship's exceptional height was due to the six decks of passenger accommodation above the waterline, compared to the customary four decks in existing liners.

High-tensile steel was used for the ship's plating, as opposed to the more conventional mild steel. This allowed a reduction in plate thickness, reducing weight but still providing 26 per cent greater strength than otherwise. Plates were held together by triple rows of rivets. The ship was heated and cooled throughout by a thermo-tank ventilation system, which used steam-driven heat exchangers to warm air to a constant , while steam was injected into the airflow to maintain steady humidity.

Forty-nine separate units driven by electric fans provided seven complete changes of air per hour throughout the ship, through an interconnected system, so that individual units could be switched off for maintenance. A separate system of exhaust fans removed air from galleys and bathrooms. As built, the ship conformed fully with Board of Trade safety regulations which required sixteen lifeboats with a capacity of approximately 1,000 people.

At the time of her completion, ''Lusitania'' was briefly the largest ship ever built, but was soon eclipsed by the slightly larger ''Mauretania'' which entered service shortly afterwards. She was longer, a full faster, and had a capacity of 10,000 gross register tons over and above that of the most modern German liner, . Passenger accommodation was 50% larger than any of her competitors, providing for 552 saloon class, 460 cabin class and 1,186 in third class. Her crew comprised 69 on deck, 369 operating engines and boilers and 389 to attend to passengers. Both she and ''Mauretania'' had a wireless telegraph, electric lighting, electric lifts, sumptuous interiors and an early form of air-conditioning.

Interiors

At the time of their introduction onto the North Atlantic, both ''Lusitania'' and ''Mauretania'' possessed among the most luxurious, spacious and comfortable interiors afloat. The Scottish architect James Miller was chosen to design ''Lusitania''s interiors, while Harold Peto was chosen to design ''Mauretania''. Miller chose to use plasterwork to create interiors whereas Peto made extensive use of wooden panelling, with the result that the overall impression given by ''Lusitania'' was brighter than ''Mauretania''.

The ship's passenger accommodation was spread across six decks; from the top deck down to the waterline they were Boat Deck (A Deck), the Promenade Deck (B Deck), the Shelter Deck (C Deck), the Upper Deck (D Deck), the Main Deck (E Deck) and the Lower Deck (F Deck), with each of the three passenger classes being allotted their own space on the ship. As seen aboard all passenger liners of the era, first-, second- and third-class passengers were strictly segregated from one another. According to her original configuration in 1907, she was designed to carry 2,198 passengers and 827 crew members. The Cunard Line prided itself with a record for passenger satisfaction.

At the time of their introduction onto the North Atlantic, both ''Lusitania'' and ''Mauretania'' possessed among the most luxurious, spacious and comfortable interiors afloat. The Scottish architect James Miller was chosen to design ''Lusitania''s interiors, while Harold Peto was chosen to design ''Mauretania''. Miller chose to use plasterwork to create interiors whereas Peto made extensive use of wooden panelling, with the result that the overall impression given by ''Lusitania'' was brighter than ''Mauretania''.

The ship's passenger accommodation was spread across six decks; from the top deck down to the waterline they were Boat Deck (A Deck), the Promenade Deck (B Deck), the Shelter Deck (C Deck), the Upper Deck (D Deck), the Main Deck (E Deck) and the Lower Deck (F Deck), with each of the three passenger classes being allotted their own space on the ship. As seen aboard all passenger liners of the era, first-, second- and third-class passengers were strictly segregated from one another. According to her original configuration in 1907, she was designed to carry 2,198 passengers and 827 crew members. The Cunard Line prided itself with a record for passenger satisfaction.

''Lusitania''s first-class accommodation was in the centre section of the ship on the five uppermost decks, mostly concentrated between the first and fourth funnels. When fully booked, ''Lusitania'' could cater to 552 first-class passengers. In common with all major liners of the period, ''Lusitania''s first-class interiors were decorated with a mélange of historical styles. The first-class dining saloon was the grandest of the ship's public rooms; arranged over two decks with an open circular well at its centre and crowned by an elaborate dome measuring , decorated with frescos in the style of François Boucher, it was elegantly realised throughout in the neoclassical

''Lusitania''s first-class accommodation was in the centre section of the ship on the five uppermost decks, mostly concentrated between the first and fourth funnels. When fully booked, ''Lusitania'' could cater to 552 first-class passengers. In common with all major liners of the period, ''Lusitania''s first-class interiors were decorated with a mélange of historical styles. The first-class dining saloon was the grandest of the ship's public rooms; arranged over two decks with an open circular well at its centre and crowned by an elaborate dome measuring , decorated with frescos in the style of François Boucher, it was elegantly realised throughout in the neoclassical Louis XVI style

Louis XVI style, also called ''Louis Seize'', is a style of architecture, furniture, decoration and art which developed in France during the 19-year reign of Louis XVI (1774–1793), just before the French Revolution. It saw the final phase of t ...

. The lower floor measuring could seat 323, with a further 147 on the upper floor. The walls were finished with white and gilt carved mahogany panels, with Corinthian decorated columns which were required to support the floor above. The one concession to seaborne life was that furniture was bolted to the floor, meaning passengers could not rearrange their seating for their personal convenience.

All other first-class public rooms were situated on the boat deck and comprised a lounge, reading and writing room, smoking room and veranda café. The last was an innovation on a Cunard liner and, in warm weather, one side of the café could be opened up to give the impression of sitting outdoors. This would have been a rarely used feature given the often inclement weather of the North Atlantic.

The first-class lounge was decorated in Georgian style with inlaid mahogany panels surrounding a jade green carpet with a yellow floral pattern, measuring overall . It had a barrel vaulted skylight rising to with stained glass windows each representing one month of the year.

All other first-class public rooms were situated on the boat deck and comprised a lounge, reading and writing room, smoking room and veranda café. The last was an innovation on a Cunard liner and, in warm weather, one side of the café could be opened up to give the impression of sitting outdoors. This would have been a rarely used feature given the often inclement weather of the North Atlantic.

The first-class lounge was decorated in Georgian style with inlaid mahogany panels surrounding a jade green carpet with a yellow floral pattern, measuring overall . It had a barrel vaulted skylight rising to with stained glass windows each representing one month of the year.

Each end of the lounge had a high green marble fireplace incorporating enamelled panels by Alexander Fisher. The design was linked overall with decorative plasterwork. The library walls were decorated with carved pilasters and mouldings marking out panels of grey and cream silk brocade. The carpet was rose, with Rose du Barry silk curtains and upholstery. The chairs and writing desks were

Each end of the lounge had a high green marble fireplace incorporating enamelled panels by Alexander Fisher. The design was linked overall with decorative plasterwork. The library walls were decorated with carved pilasters and mouldings marking out panels of grey and cream silk brocade. The carpet was rose, with Rose du Barry silk curtains and upholstery. The chairs and writing desks were mahogany

Mahogany is a straight- grained, reddish-brown timber of three tropical hardwood species of the genus '' Swietenia'', indigenous to the AmericasBridgewater, Samuel (2012). ''A Natural History of Belize: Inside the Maya Forest''. Austin: U ...

, and the windows featured etched glass. The smoking room was Queen Anne style, with Italian walnut panelling and Italian red furnishings. The grand stairway linked all six decks of the passenger accommodation with wide hallways on each level and two lifts. First-class cabins ranged from one shared room through various ensuite arrangements in a choice of decorative styles culminating in the two regal suites which each had two bedrooms, dining room, parlour and bathroom. The port suite decoration was modelled on the Petit Trianon

The Petit Trianon (; French for "small Trianon") is a Neoclassical style château located on the grounds of the Palace of Versailles in Versailles, France. It was built between 1762 and 1768 during the reign of King Louis XV of France. ...

.

''Lusitania''s second-class accommodation was confined to the stern, behind the aft mast, where quarters for 460 second-class passengers were located. The second-class public rooms were situated on partitioned sections of boat and promenade decks housed in a separate section of the superstructure aft of the first-class passenger quarters. Design work was deputised to Robert Whyte, who was the architect employed by John Brown. Although smaller and plainer, the design of the dining room reflected that of first class, with just one floor of diners under a ceiling with a smaller dome and balcony. Walls were panelled and carved with decorated pillars, all in white. As seen in first class, the dining room was situated lower down in the ship on the saloon deck. The smoking and ladies' rooms occupied the accommodation space of the second-class promenade deck, with the lounge on the boat deck.

Cunard had not previously provided a separate lounge for second class; the room had mahogany tables, chairs and settees set on a rose carpet. The smoking room was with mahogany panelling, white plaster work ceiling and dome. One wall had a mosaic of a river scene in Brittany, while the sliding windows were blue-tinted. Second-class passengers were allotted shared, yet comfortable two- and four-berth cabins arranged on the shelter, upper and main decks.

Noted as being the prime breadwinner for trans-Atlantic shipping lines, third class aboard ''Lusitania'' was praised for the improvement in travel conditions it provided to emigrant passengers; ''Lusitania'' proved to be a quite popular ship for immigrants. In the days before ''Lusitania'' and even still during the years in which ''Lusitania'' was in service, third-class accommodation consisted of large open spaces where hundreds of people would share open berths and hastily constructed public spaces, often consisting of no more than a small portion of open deck space and a few tables constructed within their sleeping quarters. In an attempt to break that mould, the Cunard Line began designing ships such as ''Lusitania'' with more comfortable third-class accommodation.

As on all Cunard passenger liners, third-class accommodation aboard ''Lusitania'' was located at the forward end of the ship on the shelter, upper, main and lower decks, and in comparison to other ships of the period, it was comfortable and spacious. The dining room was at the bow of the ship on the saloon deck, finished in polished pine as were the other two third-class public rooms, being the smoke room and ladies room on the shelter deck.

When ''Lusitania'' was fully booked in third class, the smoking and ladies room could easily be converted into overflow dining rooms for added convenience. Meals were eaten at long tables with swivel chairs and there were two sittings for meals. A piano was provided for passenger use. What greatly appealed to immigrants and lower class travellers was that instead of being confined to open berth dormitories, aboard ''Lusitania'' was a honeycomb of two, four, six and eight berth cabins allotted to third-class passengers on the main and lower decks.

The Bromsgrove Guild

The Bromsgrove Guild of Applied Arts (1898–1966) was a company of modern artists and designers associated with the Arts and Crafts Movement, founded by Walter Gilbert. The guild worked in metal, wood, plaster, bronze, tapestry, glass and ...

had designed and constructed most of the trim on ''Lusitania''. Waring and Gillow tendered for the contract to furnish the whole ship, but failing to obtain this still supplied a number of the furnishings.

Construction and trials

''Lusitania''s

''Lusitania''s keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element on a vessel. On some sailboats, it may have a hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose, as well. As the laying down of the keel is the initial step in the construction of a ship, in Br ...

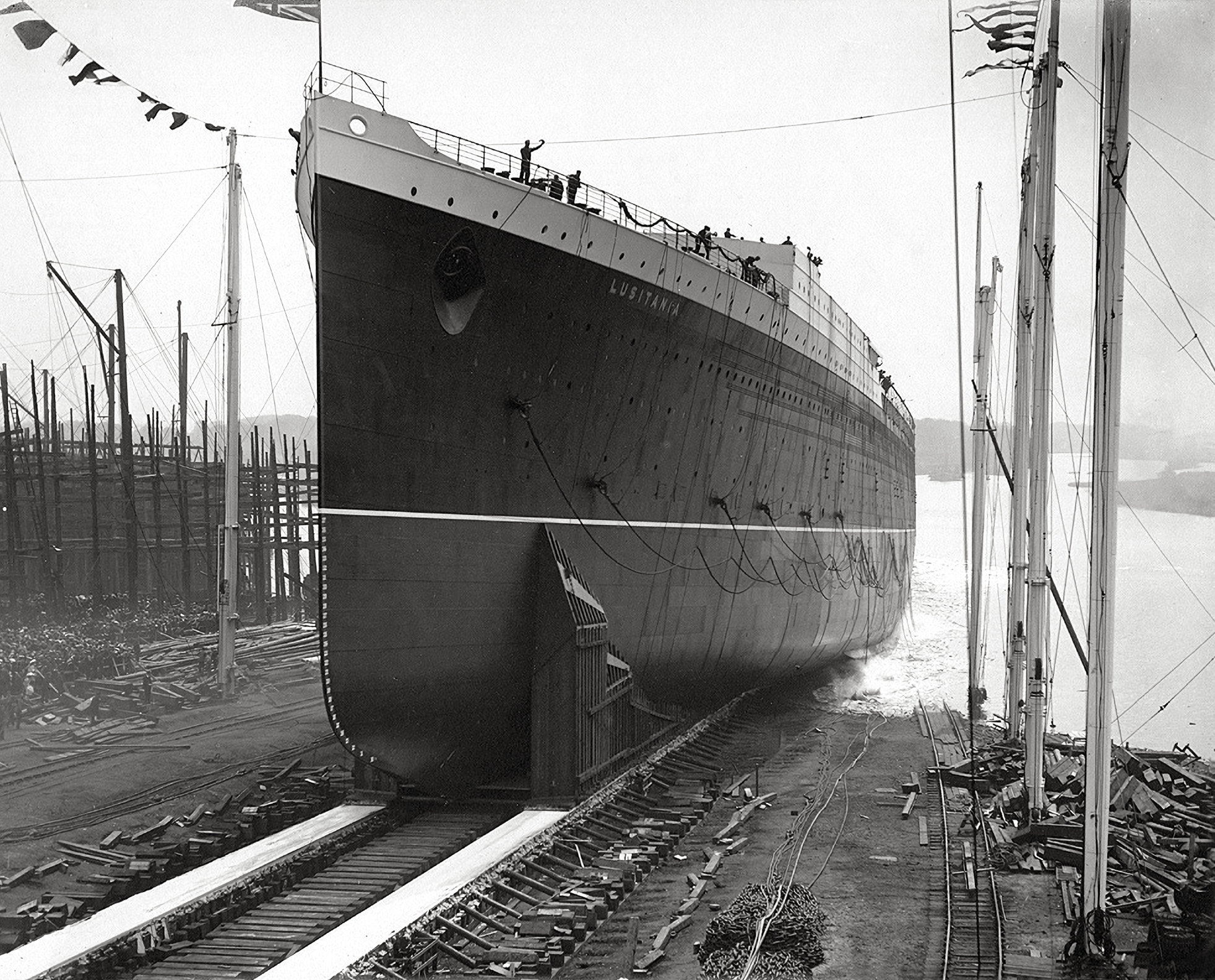

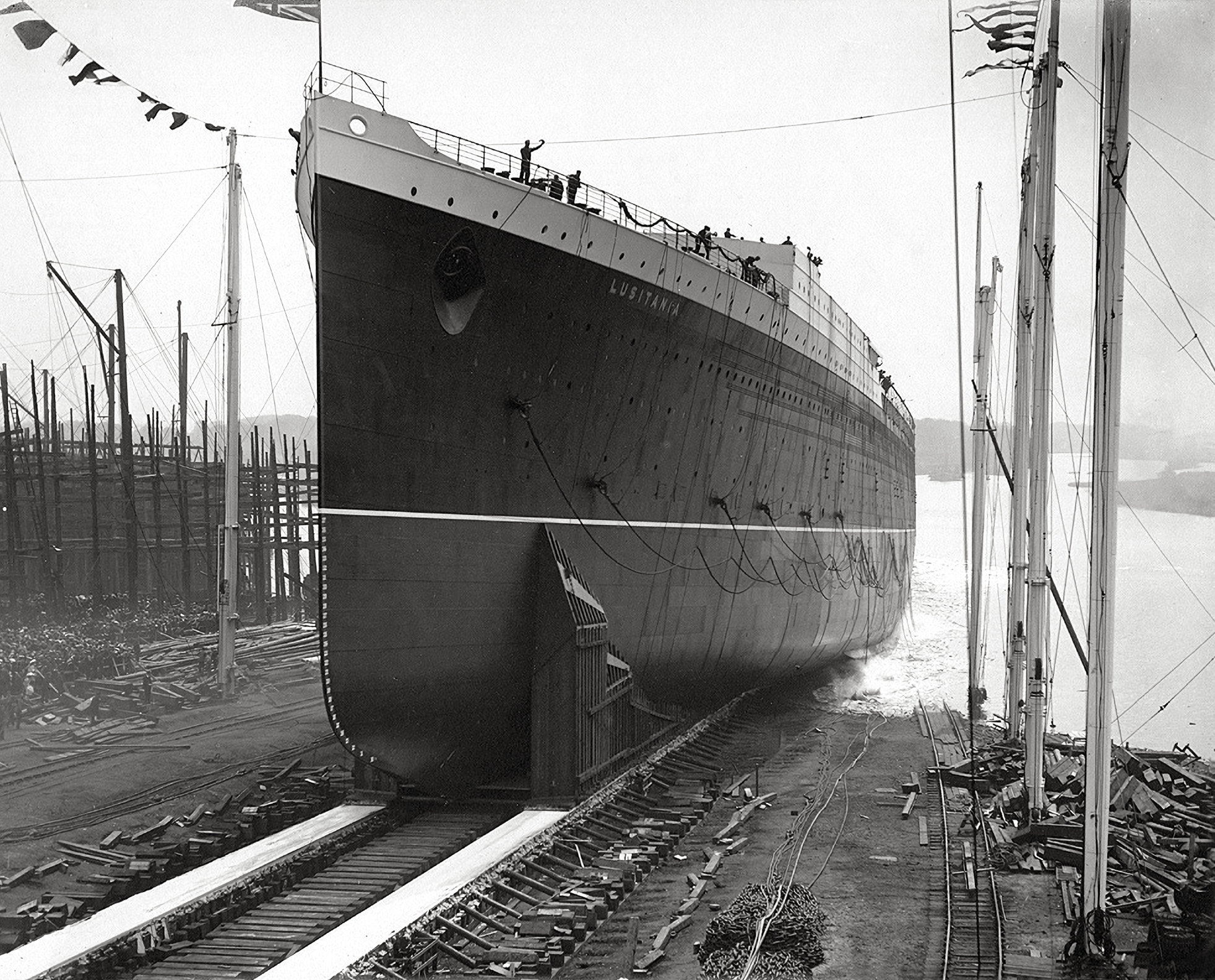

was laid at John Brown on Clydebank as yard no. 367 on 17 August 1904, Lord Inverclyde hammering home the first rivet. Cunard nicknamed her 'the Scottish ship' in contrast to ''Mauretania'' whose contract went to Swan Hunter in England and who started building three months later. Final details of the two ships were left to designers at the two yards so that the ships differed in details of hull design and finished structure. The ships may most readily be distinguished in photographs through the flat-topped ventilators used on ''Lusitania'', whereas those on ''Mauretania'' used a more conventional rounded top. ''Mauretania'' was designed a little longer, wider, heavier and with an extra power stage fitted to the turbines.

The shipyard at John Brown had to be reorganised because of her size so that she could be launched diagonally across the widest available part of the river Clyde where it met a tributary, the ordinary width of the river being only compared to the long ship. The new slipway took up the space of two existing ones and was built on reinforcing piles driven deeply into the ground to ensure it could take the temporary concentrated weight of the whole ship as it slid into the water. In addition, the company spent £8,000 to dredge the Clyde, £6,500 on new gas plant, £6,500 on a new electrical plant, £18,000 to extend the dock and £19,000 for a new crane capable of lifting 150 tons as well as £20,000 on additional machinery and equipment.

Construction commenced at the bow working backwards, rather than the traditional approach of building both ends towards the middle. This was because designs for the stern and engine layout were not finalised when construction commenced. Railway tracks were laid alongside the ship and across deck plating to bring materials as required. The hull, completed to the level of the main deck but not fitted with equipment weighed approximately 16,000 tons.

The ship's stockless bower anchors weighed 10 tons, attached to 125 ton, 330 fathom chains all manufactured by N. Hingley & Sons Ltd. The steam capstans to raise them were constructed by Napier Brothers Ltd, of Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popu ...

. The turbines were long with diameter rotors, the large diameter necessary because of the relatively low speeds at which they operated. The rotors were constructed on site, while the casings and shafting were constructed in John Brown's Atlas works in Sheffield

Sheffield is a city in South Yorkshire, England, whose name derives from the River Sheaf which runs through it. The city serves as the administrative centre of the City of Sheffield. It is historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire ...

. The machinery to drive the 56-ton rudder was constructed by Brown Brothers of Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

. A main steering engine drove the rudder through worm gear and clutch operating on a toothed quadrant rack, with a reserve engine operating separately on the rack via a chain drive for emergency use. The three-bladed propellers were fitted and then cased in wood to protect them during the launch.

The ship was launched on 7 June 1906, eight weeks later than planned due to labour strikes and eight months after Lord Inverclyde's death. Princess Louise Princess Louise may refer to:

;People:

* Princess Louise, Duchess of Argyll, 1848–1939, the sixth child and fourth daughter of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom

* Princess Louise, Princess Royal and Duchess of Fife, 1867–1931, the ...

was invited to name the ship but could not attend, so the honour fell to Inverclyde's widow Mary. The launch was attended by 600 invited guests and thousands of spectators. One thousand tons of drag chains were attached to the hull by temporary rings to slow it once it entered the water. The wooden supporting structure was held back by cables so that once the ship entered the water it would slip forward out of its support. Six tugs were on hand to capture the hull and move it to the fitting out berth.

Testing of the ship's engines took place in June 1907 prior to full trials scheduled for July. A preliminary cruise, or ''Builder's Trial'', was arranged for 27 July with representatives of Cunard, the Admiralty, the Board of Trade, and John Brown aboard. The ship achieved speeds of over a measured at Skelmorlie

Skelmorlie is a village in North Ayrshire in the south-west of Scotland. Although it is the northernmost settlement in the council area of North Ayrshire, it is contiguous with Wemyss Bay, which is in Inverclyde. The dividing line is the Kell ...

with turbines running at 194 revolutions per minute producing 76,000 shp. At high speeds the ship was found to suffer such vibration at the stern as to render the second-class accommodation uninhabitable. VIP invited guests now came on board for a two-day shakedown cruise during which the ship was tested under continuous running at speeds of 15, 18 and 21 knots but not her maximum speed. On 29 July, the guests departed and three days of full trials commenced. The ship travelled four times between the Corsewall Light off Scotland to the Longship Light off Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a Historic counties of England, historic county and Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people ...

at 23 and 25 knots, between the Corsewall Light and the Isle of Man

)

, anthem = " O Land of Our Birth"

, image = Isle of Man by Sentinel-2.jpg

, image_map = Europe-Isle_of_Man.svg

, mapsize =

, map_alt = Location of the Isle of Man in Europe

, map_caption = Location of the Isle of Man (green)

in Europ ...

, and the Isle of Arran and Ailsa Craig. Over an average speed of 25.4 knots was achieved, comfortably greater than the 24 knots required under the Admiralty contract. The ship could stop in 4 minutes in 3/4 of a mile starting from 23 knots at 166 rpm and then applying full reverse. She achieved a speed of 26 knots over a measured mile loaded to a draught of , and managed 26.5 knots over a course drawing . At 180 revolutions a turning test was conducted and the ship performed a complete circle of diameter 1000 yards in 50 seconds. The rudder required 20 seconds to be turned hard to 35 degrees.

The vibration was determined to be caused by interference between the wake of the outer propellers and inner and became worse when turning. At high speeds the vibration frequency resonated with the ship's stern making the matter worse. The solution was to add internal stiffening to the stern of the ship but this necessitated gutting the second-class areas and then rebuilding them. This required the addition of a number of pillars and arches to the decorative scheme. The ship was finally delivered to Cunard on 26 August although the problem of vibration was never entirely solved and further remedial work went on through her life.

Comparison with the ''Olympic'' class

TheWhite Star Line

The White Star Line was a British shipping company. Founded out of the remains of a defunct packet company, it gradually rose up to become one of the most prominent shipping lines in the world, providing passenger and cargo services between ...

's vessels were almost longer and slightly wider than ''Lusitania'' and ''Mauretania''. This made the White Star vessels about 15,000 tons

Tons can refer to:

* Tons River, a major river in India

* Tamsa River, locally called Tons in its lower parts (Allahabad district, Uttar pradesh, India).

* the plural of ton, a unit of mass, force, volume, energy or power

:* short ton, 2,000 poun ...

larger than the Cunard vessels. Both ''Lusitania'' and ''Mauretania'' were launched and had been in service for several years before ''Olympic'', and ''Britannic'' were ready for the North Atlantic run. Although significantly faster than the ''Olympic'' class would be, the speed of Cunard's vessels was not sufficient to allow the line to run a weekly two-ship transatlantic service from each side of the Atlantic. A third ship was needed for a weekly service, and in response to White Star's announced plan to build the three ''Olympic''-class ships, Cunard ordered a third ship: . Like , Cunard's ''Aquitania'' had a lower service speed, but was a larger and more luxurious vessel.

Due to their increased size the ''Olympic''-class liners could offer many more amenities than ''Lusitania'' and ''Mauretania''. Both ''Olympic'' and ''Titanic'' offered swimming pools, Turkish baths, a gymnasium, a squash court, large reception rooms, À la Carte restaurants separate from the dining saloons, and many more staterooms with private bathroom facilities than their two Cunard rivals.

Heavy vibrations as a by-product of the four steam turbine

A steam turbine is a machine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work on a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Charles Parsons in 1884. Fabrication of a modern steam tu ...

s on ''Lusitania'' and ''Mauretania'' would plague both ships throughout their voyages. When ''Lusitania'' sailed at top speed the resultant vibrations were so severe that second- and third-class sections of the ship could become uninhabitable. In contrast, the ''Olympic''-class liners used two traditional reciprocating engine

A reciprocating engine, also often known as a piston engine, is typically a heat engine that uses one or more reciprocating pistons to convert high temperature and high pressure into a rotating motion. This article describes the common fe ...

s and only one turbine for the central propeller, which greatly reduced vibration. Because of their greater tonnage and wider beam, the ''Olympic''-class liners were also more stable at sea and less prone to rolling. ''Lusitania'' and ''Mauretania'' both featured straight prows in contrast to the angled prows of the ''Olympic'' class. Designed so that the ships could plunge through a wave rather than crest it, the unforeseen consequence was that the Cunard liners would pitch forward alarmingly, even in calm weather, allowing huge waves to splash the bow and forward part of the superstructure. This would be a major factor in damage that ''Lusitania'' suffered at the hands of a rogue wave in January 1910.

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, sank in 1916 after hitting a mine in the Kea Channel the already davited boats were swiftly lowered saving nearly all on board, but the ship took nearly three times as long to sink as ''Lusitania'' and thus the crew had more time to evacuate passengers.

Career

''Lusitania'', commanded by Commodore James Watt, moored at the

''Lusitania'', commanded by Commodore James Watt, moored at the Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

landing stage for her maiden voyage at 4:30 pm on Saturday 7 September 1907 as the onetime Blue Riband holder vacated the pier. At the time ''Lusitania'' was the largest ocean liner in service and would continue to be until the introduction of ''Mauretania'' in November that year. A crowd of 200,000 people gathered to see her departure at 9:00 pm for Queenstown (renamed Cobh in 1920), where she was to take on more passengers. She anchored again at Roche's Point, off Queenstown, at 9:20 am the following morning, where she was shortly joined by ''Lucania'', which she had passed in the night, and 120 passengers were brought out to the ship by tender bringing her total of passengers to 2,320.

At 12:10 pm on Sunday ''Lusitania'' was again under way and passing the Daunt Rock Lightship. In the first 24 hours she achieved , with further daily totals of 575, 570, 593 and before arriving at Sandy Hook

Sandy Hook is a barrier spit in Middletown Township, Monmouth County, New Jersey, United States.

The barrier spit, approximately in length and varying from wide, is located at the north end of the Jersey Shore. It encloses the southern ...

at 9:05 am Friday 13 September, taking in total 5 days and 54 minutes, 30 minutes outside the record time held by of the North German Lloyd

Norddeutscher Lloyd (NDL; North German Lloyd) was a German shipping company. It was founded by Hermann Henrich Meier and Eduard Crüsemann in Bremen on 20 February 1857. It developed into one of the most important German shipping companies of th ...

line. Fog had delayed the ship on two days, and her engines were not yet run in. In New York hundreds of thousands of people gathered on the bank of the Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between Ne ...

from Battery Park to pier 56. All New York's police had been called out to control the crowd. From the start of the day, 100 horse-drawn cabs had been queuing, ready to take away passengers. During the week's stay the ship was made available for guided tours. At 3 pm on Saturday 21 September, the ship departed on the return journey, arriving Queenstown 4 am 27 September and Liverpool 12 hours later. The return journey was 5 days 4 hours and 19 minutes, again delayed by fog.

On her second voyage in better weather, ''Lusitania'' arrived at Sandy Hook on 11 October 1907 in the Blue Riband record time of 4 days, 19 hours and 53 minutes. She had to wait for the tide to enter harbour where news had preceded her and she was met by a fleet of small craft, whistles blaring. ''Lusitania'' averaged westbound and eastbound. In December 1907, ''Mauretania'' entered service and took the record for the fastest eastbound crossing. ''Lusitania'' made her fastest westbound crossing in 1909 after her propellers were changed, averaging . She briefly recovered the record in July of that year, but ''Mauretania'' recaptured the Blue Riband the same month, retaining it until 1929, when it was taken by . During her eight-year service, she made a total of 201 crossings on the Cunard Line's Liverpool-New York Route, carrying a total of 155,795 passengers westbound and another 106,180 eastbound.

Hudson Fulton Celebration

''Lusitania'' and other ships participated in the Hudson-Fulton Celebration in New York City from the end of September to early October 1909. The celebration was also a display of the different modes of transportation then in existence, ''Lusitania'' representing the newest advancement in steamship technology. A newer mode of travel was the

''Lusitania'' and other ships participated in the Hudson-Fulton Celebration in New York City from the end of September to early October 1909. The celebration was also a display of the different modes of transportation then in existence, ''Lusitania'' representing the newest advancement in steamship technology. A newer mode of travel was the aeroplane

An airplane or aeroplane (informally plane) is a fixed-wing aircraft that is propelled forward by thrust from a jet engine, propeller, or rocket engine. Airplanes come in a variety of sizes, shapes, and wing configurations. The broad spec ...

. Wilbur Wright had brought a Flyer to Governors Island and made demonstration flights before millions of New Yorkers who had never seen an aircraft. Some of Wright's trips were directly over ''Lusitania''; several photographs of ''Lusitania'' from that week still exist.

Rogue wave crash

On 10 January 1910, ''Lusitania'' was on a voyage from Liverpool to New York, when, two days into the trip, she encountered a rogue wave that was 23 metres (75 ft) high. The design of the ship's bow allowed for her to break through waves instead of riding on top of them. This, however, came with a cost, as the wave rolled over ''Lusitanias bow and slammed into the bridge. As a result, the forecastle deck was damaged, the bridge windows were smashed, the bridge was shifted a couple of inches aft, and both the deck and the bridge were given a permanent depression of a few inches. No one was injured, and the ''Lusitania'' continued on as normal, albeit arriving a few hours late in New York with some shaken-up passengers.Outbreak of the First World War

When ''Lusitania'' was built, her construction and operating expenses were subsidised by the British government, with the proviso that she could be converted to anarmed merchant cruiser

An armed merchantman is a merchant ship equipped with guns, usually for defensive purposes, either by design or after the fact. In the days of sail, piracy and privateers, many merchantmen would be routinely armed, especially those engaging in lo ...

(AMC) if need be. A secret compartment was designed in for the purpose of carrying arms and ammunition. When war was declared she was requisitioned by the British Admiralty as an armed merchant cruiser, and she was put on the official list of AMCs. ''Lusitania'' remained on the official AMC list and was listed as an auxiliary cruiser in the 1914 edition of ''Jane's All the World's Fighting Ships'', along with ''Mauretania''.

The 1856 Declaration of Paris codified the rules for naval engagements involving civilian vessels. The so-called Cruiser Rules

Cruiser rules is a colloquial phrase referring to the conventions regarding the attacking of a merchant ship by an armed vessel. Here ''cruiser'' is meant in its original meaning of a ship sent on an independent mission such as commerce raiding. ...

required that the crew and passengers of civilian ships be safeguarded in the event that the ship is to be confiscated or sunk. These rules also placed some onus on the ship itself, in that the merchant ship had to be flying its own flag, and not pretending to be of a different nationality. Also, it had to stop when confronted and allow itself to be boarded and searched, and it was not allowed to be armed or to take any hostile or evasive actions. When war was declared, British merchant ships were given orders to ram submarines that surfaced to issue the warnings required by the Cruiser Rules.

At the outbreak of hostilities, fears for the safety of ''Lusitania'' and other great liners ran high. During the ship's first east-bound crossing after the war started, she was painted in a grey colour scheme in an attempt to mask her identity and make her more difficult to detect visually.

Many of the large liners were laid up in 1914–1915, in part due to falling demand for passenger travel across the Atlantic, and in part to protect them from damage due to mines or other dangers. Among the most recognisable of these liners, some were eventually used as troop transports, while others became hospital ships. ''Lusitania'' remained in commercial service; although bookings aboard her were by no means strong during that autumn and winter, demand was strong enough to keep her in civilian service. Economising measures were taken. One of these was the shutting down of her No. 4 boiler room to conserve coal and crew costs; this reduced her maximum speed from over to . With apparent dangers evaporating, the ship's disguised paint scheme was also dropped and she was returned to civilian colours. Her name was picked out in gilt, her funnels were repainted in their normal Cunard livery, and her superstructure was painted white again. One alteration was the addition of a bronze/gold-coloured band around the base of the superstructure just above the black paint.

Many of the large liners were laid up in 1914–1915, in part due to falling demand for passenger travel across the Atlantic, and in part to protect them from damage due to mines or other dangers. Among the most recognisable of these liners, some were eventually used as troop transports, while others became hospital ships. ''Lusitania'' remained in commercial service; although bookings aboard her were by no means strong during that autumn and winter, demand was strong enough to keep her in civilian service. Economising measures were taken. One of these was the shutting down of her No. 4 boiler room to conserve coal and crew costs; this reduced her maximum speed from over to . With apparent dangers evaporating, the ship's disguised paint scheme was also dropped and she was returned to civilian colours. Her name was picked out in gilt, her funnels were repainted in their normal Cunard livery, and her superstructure was painted white again. One alteration was the addition of a bronze/gold-coloured band around the base of the superstructure just above the black paint.

1915

By early 1915, a new threat began to materialise: submarines. At first, they were used by the Germans only to attack naval vessels, something they achieved only occasionally but sometimes with spectacular success. Then the U-boats began to attack merchant vessels at times, although almost always in accordance with the old

By early 1915, a new threat began to materialise: submarines. At first, they were used by the Germans only to attack naval vessels, something they achieved only occasionally but sometimes with spectacular success. Then the U-boats began to attack merchant vessels at times, although almost always in accordance with the old Cruiser Rules

Cruiser rules is a colloquial phrase referring to the conventions regarding the attacking of a merchant ship by an armed vessel. Here ''cruiser'' is meant in its original meaning of a ship sent on an independent mission such as commerce raiding. ...

. Desperate to gain an advantage on the Atlantic, the German government decided to step up their submarine campaign, as a result of the British declaring the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian ...

a war zone in November 1914. On 4 February 1915, Germany declared the seas around Great Britain and Ireland a war zone: from 18 February Allied ships in the area would be sunk without warning. This was not wholly unrestricted submarine warfare

Unrestricted submarine warfare is a type of naval warfare in which submarines sink merchant ships such as freighters and tankers without warning, as opposed to attacks per prize rules (also known as "cruiser rules") that call for warships to s ...

as efforts would be taken to avoid sinking neutral ships.

''Lusitania'' was scheduled to arrive in Liverpool on 6 March 1915. The Admiralty issued her specific instructions on how to avoid submarines. Admiral Henry Oliver ordered HMS ''Louis'' and HMS ''Laverock'' to escort ''Lusitania'', and took the further precaution of sending the Q-ship

Q-ships, also known as Q-boats, decoy vessels, special service ships, or mystery ships, were heavily armed merchant ships with concealed weaponry, designed to lure submarines into making surface attacks. This gave Q-ships the chance to open f ...

HMS ''Lyons'' to patrol Liverpool Bay. The destroyer commander attempted to discover the whereabouts of ''Lusitania'' by telephoning Cunard, who refused to give out any information and referred him to the Admiralty. At sea, the ships contacted ''Lusitania'' by radio but did not have the codes used to communicate with merchant ships. Captain Dow of ''Lusitania'' refused to give his own position except in code, and since he was, in any case, some distance from the positions they gave, continued to Liverpool unescorted.

In response to this new submarine threat, some alterations were made to the ship's protocols. In contravention to the Cruiser Rules she was ordered not to fly any flags in the war zone. Some messages were sent to the ship's commander to help him decide how to best protect his ship against the new threat, and it also seems that her funnels were most likely painted dark grey to help make her less visible to enemy submarines. Clearly, there was no hope of disguising her identity, as her profile was so well known, and no attempt was made to paint out the ship's name at the bow.

Captain Dow, apparently suffering from stress from operating his ship in the war zone, and after a significant " false flag" controversy, left the ship; Cunard later explained that he was "tired and really ill". He was replaced by Captain William Thomas Turner

Commander William Thomas Turner, OBE, RNR (23 October 1856 – 23 June 1933) was a British merchant navy captain. He is best known as the captain of when she was sunk by a German torpedo in May 1915.

Career and honors Early life and c ...

, who had previously commanded ''Lusitania'', ''Mauretania'', and ''Aquitania'' in the years before the war.

On 17 April 1915, ''Lusitania'' left Liverpool on her 201st transatlantic voyage, arriving in New York on 24 April. A group of German-Americans, hoping to avoid controversy if ''Lusitania'' was attacked by a U-boat, discussed their concerns with a representative of the German Embassy. The embassy decided to warn passengers before her next crossing not to sail aboard ''Lusitania''. The Imperial German Embassy placed a warning advertisement in 50 American newspapers, including those in New York:

This warning was printed adjacent to an advertisement for ''Lusitania''s return voyage which led to many interpreting this as a direct message to the ''Lusitania''. The ship departed

This warning was printed adjacent to an advertisement for ''Lusitania''s return voyage which led to many interpreting this as a direct message to the ''Lusitania''. The ship departed Pier 54

Chelsea Piers is a series of piers in Chelsea, on the West Side of Manhattan in New York City. Located to the west of the West Side Highway ( Eleventh Avenue) and Hudson River Park and to the east of the Hudson River, they were originally a ...