Quisling regime on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Quisling regime or Quisling government are common names used to refer to the

With the establishment of Quisling's national government, Quisling, as minister-president, temporarily assumed the authority of both the King and the

With the establishment of Quisling's national government, Quisling, as minister-president, temporarily assumed the authority of both the King and the

One of Quisling's first actions was to reintroduce the prohibition of Jews entering Norway, which was formerly a part of the Constitution's §2 from 1814 to 1851.

Two of the early laws of the Quisling regime, ''Lov om nasjonal ungdomstjeneste'' (English: 'Law on national youth service') and ''Lov om Norges Lærersamband'' (English: 'The Norwegian Teacher Liaison'), both signed 5 February 1942, led to massive protests from parents, serious clashes with the teachers, and an escalating conflict with the

One of Quisling's first actions was to reintroduce the prohibition of Jews entering Norway, which was formerly a part of the Constitution's §2 from 1814 to 1851.

Two of the early laws of the Quisling regime, ''Lov om nasjonal ungdomstjeneste'' (English: 'Law on national youth service') and ''Lov om Norges Lærersamband'' (English: 'The Norwegian Teacher Liaison'), both signed 5 February 1942, led to massive protests from parents, serious clashes with the teachers, and an escalating conflict with the

The regime looked nostalgically to the

The regime looked nostalgically to the

/ref> Quisling's proposal was sent to both OKW chief

The ministers of the Quisling regime in 1942 were:

* Eivind Blehr (Minister of Trade and Minister of Supplies)

*

The ministers of the Quisling regime in 1942 were:

* Eivind Blehr (Minister of Trade and Minister of Supplies)

*

fascist

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and the ...

collaborationist

Wartime collaboration is cooperation with the enemy against one's country of citizenship in wartime, and in the words of historian Gerhard Hirschfeld, "is as old as war and the occupation of foreign territory".

The term ''collaborator'' dates to ...

government led by Vidkun Quisling

Vidkun Abraham Lauritz Jonssøn Quisling (, ; 18 July 1887 – 24 October 1945) was a Norwegian military officer, politician and Nazi collaborator who nominally list of heads of government of Norway, headed the government of Norway during t ...

in German-occupied Norway during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

. The official name of the regime from 1 February 1942 until its dissolution in May 1945 was Den nasjonale regjering ( en, the National Government). Actual executive power was retained by the Reichskommissariat Norwegen, headed by Josef Terboven

Josef Terboven (23 May 1898 – 8 May 1945) was a Nazi Party official and politician who was the long-serving '' Gauleiter'' of Gau Essen and the ''Reichskommissar'' for Norway during the German occupation.

Early life

Terboven was born in E ...

.

Given the use of the term quisling, the name ''Quisling regime'' can also be used as a derogatory term referring to political regimes perceived as treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

ous puppet government

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside power and subject to its orders.Compare: Puppet states have nominal sover ...

s imposed by occupying foreign enemies.

1940 coup

Vidkun Quisling, '' Fører'' of theNasjonal Samling

Nasjonal Samling (, NS; ) was a Norwegian far-right political party active from 1933 to 1945. It was the only legal party of Norway from 1942 to 1945. It was founded by former minister of defence Vidkun Quisling and a group of supporters such ...

party, had first tried to carry out a coup against the Norwegian government on 9 April 1940, the day of the German invasion of Norway. At 7:32 p.m., Quisling visited the studios of the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation

NRK, an abbreviation of the Norwegian ''Norsk Rikskringkasting AS'', generally expressed in English as the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation, is the Norwegian government-owned radio and television public broadcasting company, and the larges ...

and made a radio broadcast proclaiming himself Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

and ordering all resistance to halt at once. He announced that he and Nasjonal Samling were taking power due to Nygaardsvold's Cabinet

__NOTOC__

Nygaardsvold's Cabinet (later becoming the Norwegian government-in-exile, Norwegian: ''Norsk eksilregjering'') was appointed on 20 March 1935, the second Labour cabinet in Norway. It brought to an end the non-socialist minority Gover ...

having "raised armed resistance and promptly fled". He further declared that in the present situation it was "the duty and the right of the movement of Nasjonal Samling to take over governmental power". Quisling claimed that the Nygaardsvold Cabinet had given up power despite that it had only moved to Elverum

is a municipality in Innlandet county, Norway. It is located in the traditional district of Østerdalen. The administrative centre of the municipality is the town of Elverum. Other settlements in the municipality include Heradsbygd, Sørskog ...

, which is some 140 kilometers (85 miles) from Oslo

Oslo ( , , or ; sma, Oslove) is the capital and most populous city of Norway. It constitutes both a county and a municipality. The municipality of Oslo had a population of in 2022, while the city's greater urban area had a population of ...

, and was carrying out negotiations with the Germans.

The next day, German ambassador Curt Bräuer

Curt Bräuer (24 February 1889 – 8 September 1969) was a German career diplomat.

Born in Breslau, in what is modern-day Poland, Bräuer entered service in the German foreign ministry in 1920. From 1928 to 1930 he was a member of the German De ...

traveled to Elverum and demanded King Haakon VII return to Oslo

Oslo ( , , or ; sma, Oslove) is the capital and most populous city of Norway. It constitutes both a county and a municipality. The municipality of Oslo had a population of in 2022, while the city's greater urban area had a population of ...

and formally appoint Quisling as prime minister. Haakon stalled for time, telling the ambassador that Norwegian kings could not make political decisions on their own authority. At a Cabinet meeting later that night, Haakon said that he could not in good conscience appoint Quisling as prime minister because he knew neither the people nor the Storting

The Storting ( no, Stortinget ) (lit. the Great Thing) is the supreme legislature of Norway, established in 1814 by the Constitution of Norway. It is located in Oslo. The unicameral parliament has 169 members and is elected every four years ...

had confidence in him. Haakon further stated that he would abdicate rather than appoint a government headed by Quisling. By this time, news of Quisling's attempted coup had reached Elverum. Negotiations promptly collapsed, and the government unanimously advised Haakon not to appoint Quisling as prime minister.

Quisling tried to have the Nygaardsvold Cabinet arrested, but the officer he instructed to carry out the arrest ignored the warrant. Attempts at gaining control over the police force in Oslo by issuing orders to Kristian Welhaven, the chief of police, also failed. The coup failed after six days, despite German support for the first three days, and Quisling had to step aside in the occupied parts of Norway in favour of the Administrative Council (''Administrasjonsrådet''). The Administrative Council was formed on 15 April by members of the Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

and supported by Norwegian business leaders as well as Bräuer as an alternative to Quisling's Nasjonal Samling in the occupied areas.

Provisional Councillors of State

On 25 September 1940, German ''Reichskommissar

(, rendered as "Commissioner of the Empire", "Reich Commissioner" or "Imperial Commissioner"), in German history, was an official gubernatorial title used for various public offices during the period of the German Empire and Nazi Germany.

Ger ...

'' Josef Terboven

Josef Terboven (23 May 1898 – 8 May 1945) was a Nazi Party official and politician who was the long-serving '' Gauleiter'' of Gau Essen and the ''Reichskommissar'' for Norway during the German occupation.

Early life

Terboven was born in E ...

, who on 24 April 1940 had replaced Curt Bräuer as the top civilian commander in Norway, proclaimed the deposition of King Haakon VII

Haakon VII (; born Prince Carl of Denmark; 3 August 187221 September 1957) was the King of Norway from November 1905 until his death in September 1957.

Originally a Danish prince, he was born in Copenhagen as the son of the future Frederick ...

and the Nygaardsvold Cabinet, banning all political parties other than Nasjonal Samling. Terboven then appointed a group of 11 kommissariske statsråder ( en, provisional councillors of state) from Nasjonal Samling to help him in governing Norway. Although the provisional councillors of state did not form a government, the intention of the Germans was to use them to prepare the way for a Nasjonal Samling take-over of power in the future. Vidkun Quisling was made the political head of the councillors and all members of Nasjonal Samling had to swear a personal oath of allegiance to him. Most of the councillors worked diligently at introducing Nasjonal Samling ideals and politics. Amongst the schemes introduced during the council period was the introduction of labour duty, reforms of the labour market, the penal code and the system of justice, a reorganization of the police and the introduction of national socialist ideals in the Norwegian culture scene. The provisional councillors of state were intended as a temporary system while Nasjonal Samling built up its organization in preparation for assuming full governmental powers. On 25 September 1941, the one-year anniversary of the councillors, Terboven gave them the title of "ministers".

Government

With the establishment of Quisling's national government, Quisling, as minister-president, temporarily assumed the authority of both the King and the

With the establishment of Quisling's national government, Quisling, as minister-president, temporarily assumed the authority of both the King and the Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

.

In 1942, after two years of direct civilian administration by the Germans (which continued de facto until 1945), he was finally put in charge of a collaborationist government, which was officially proclaimed on 1 February 1942. The official name of the government was "Den nasjonale regjering" ( en, the National Government). The original intention of the Germans had been to hand over the sovereignty of Norway to the new government, but by mid-January 1942 Hitler decided to retain the civilian '' Reichskommissariat Norwegen'' under Terboven. The Quisling government was instead given the role of an occupying authority with wide-ranging authorisations. Quisling himself viewed the creation of his government as a "decisive step on the road towards the complete independence of Norway". Although having only temporarily assumed the King's authority, Quisling still made efforts to distance his regime from the exiled monarchy. After Quisling moved into the Royal Palace

This is a list of royal palaces, sorted by continent.

Africa

* Abdin Palace, Cairo

* Al-Gawhara Palace, Cairo

* Koubbeh Palace, Cairo

* Tahra Palace, Cairo

* Menelik Palace

* Jubilee Palace

* Guenete Leul Palace

* Imperial Palace- ...

he took back into use the official seal

Seal may refer to any of the following:

Common uses

* Pinniped, a diverse group of semi-aquatic marine mammals, many of which are commonly called seals, particularly:

** Earless seal, or "true seal"

** Fur seal

* Seal (emblem), a device to imp ...

of Norway, changing the wording from "Haakon VII Norges konge" to "Norges rikes segl" (in English translation, from "Haakon VII King of Norway" to "The Seal of the Norwegian Realm"). After establishing national government Quisling claimed to hold "the authority that according to the Constitution belonged to the King and Parliament".

Other important ministers of the collaborationist government were Jonas Lie (also head of the Norwegian wing of the SS from 1941) as Minister of the Police, Dr. Gulbrand Lunde

Gulbrand Oscar Johan Lunde (14 September 1901, Bergen – 26 October 1942, Våge, Rauma, Norway) was a Norwegian councillor of state in the NS government of Vidkun Quisling in 1940, acting councillor of state 1940-1941 and minister 1941–194 ...

as Minister of Culture and Enlightenment, as well as the opera singer Albert Viljam Hagelin

Albert Viljam Hagelin (24 April 1881 – 25 May 1946) was a Norwegian businessman and opera singer who became the Minister of Domestic Affairs in the Quisling regime, the puppet government headed by Vidkun Quisling during Germany's World W ...

, who was Minister of the Interior.

Politics

One of Quisling's first actions was to reintroduce the prohibition of Jews entering Norway, which was formerly a part of the Constitution's §2 from 1814 to 1851.

Two of the early laws of the Quisling regime, ''Lov om nasjonal ungdomstjeneste'' (English: 'Law on national youth service') and ''Lov om Norges Lærersamband'' (English: 'The Norwegian Teacher Liaison'), both signed 5 February 1942, led to massive protests from parents, serious clashes with the teachers, and an escalating conflict with the

One of Quisling's first actions was to reintroduce the prohibition of Jews entering Norway, which was formerly a part of the Constitution's §2 from 1814 to 1851.

Two of the early laws of the Quisling regime, ''Lov om nasjonal ungdomstjeneste'' (English: 'Law on national youth service') and ''Lov om Norges Lærersamband'' (English: 'The Norwegian Teacher Liaison'), both signed 5 February 1942, led to massive protests from parents, serious clashes with the teachers, and an escalating conflict with the Church of Norway

The Church of Norway ( nb, Den norske kirke, nn, Den norske kyrkja, se, Norgga girku, sma, Nöörjen gærhkoe) is an evangelical Lutheran denomination of Protestant Christianity and by far the largest Christian church in Norway. The church ...

. Schools were closed for one month, and in March 1942 around 1,100 teachers were arrested by the Norwegian police and sent to German prisons and concentration camps, and about 500 of the teachers were forced to Kirkenes as construction workers for the German occupants.

Goal of independence

Even after the official creation of the Quisling government,Josef Terboven

Josef Terboven (23 May 1898 – 8 May 1945) was a Nazi Party official and politician who was the long-serving '' Gauleiter'' of Gau Essen and the ''Reichskommissar'' for Norway during the German occupation.

Early life

Terboven was born in E ...

still ruled Norway as a dictator, taking orders from no-one but Hitler. Quisling's regime was a puppet government

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside power and subject to its orders.Compare: Puppet states have nominal sover ...

, although Quisling wanted independence and the recall of Terboven, something he constantly lobbied Hitler for, without success. Quisling wanted to achieve independence for Norway under his rule, with an end to the German occupation of Norway through a peace treaty and the recognition of Norway's sovereignty by Germany. He further wanted to ally Norway to Germany and join the Anti-Comintern Pact

The Anti-Comintern Pact, officially the Agreement against the Communist International was an anti-Communist pact concluded between Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan on 25 November 1936 and was directed against the Communist International (C ...

. After a reintroduction of national service in Norway, Norwegian troops were to fight with the Axis powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

in the Second World War.

Quisling also fronted the idea of a pan-European union led, but not dominated, by Germany, with a common currency and a common market

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organization created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lisbo ...

. Quisling presented his plans to Hitler repeatedly in memos and talks with the German dictator, the first time 13 February 1942 in the Reich Chancellery

The Reich Chancellery (german: Reichskanzlei) was the traditional name of the office of the Chancellor of Germany (then called ''Reichskanzler'') in the period of the German Reich from 1878 to 1945. The Chancellery's seat, selected and prepared ...

in Berlin and the last time on 28 January 1945, again in the Reich Chancellery. All of Quisling's ideas were rejected by Hitler, who did not want any permanent agreements before the war had been concluded, while also desiring Norway's outright annexation

Annexation (Latin ''ad'', to, and ''nexus'', joining), in international law, is the forcible acquisition of one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. It is generally held to be an illegal act ...

into Germany as the northernmost province of a Greater Germanic Reich

The Greater Germanic Reich (german: Großgermanisches Reich), fully styled the Greater Germanic Reich of the German Nation (german: Großgermanisches Reich deutscher Nation), was the official state name of the political entity that Nazi Germany ...

. Hitler did, however, in an April 1943 meeting promise Quisling that once the war was over Norway would regain its independence. This is the only known case of Hitler making such a promise to an occupied country.

The word '' Quisling'' has become synonymous with treachery and collaboration with the enemy.

Territorial claims

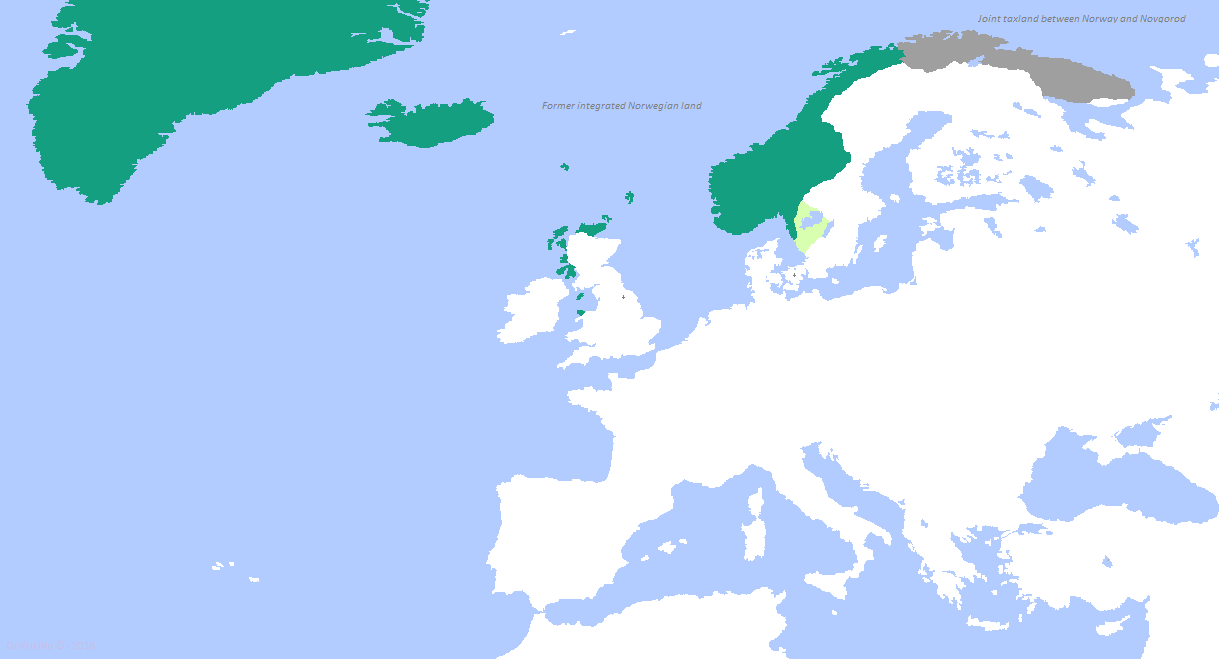

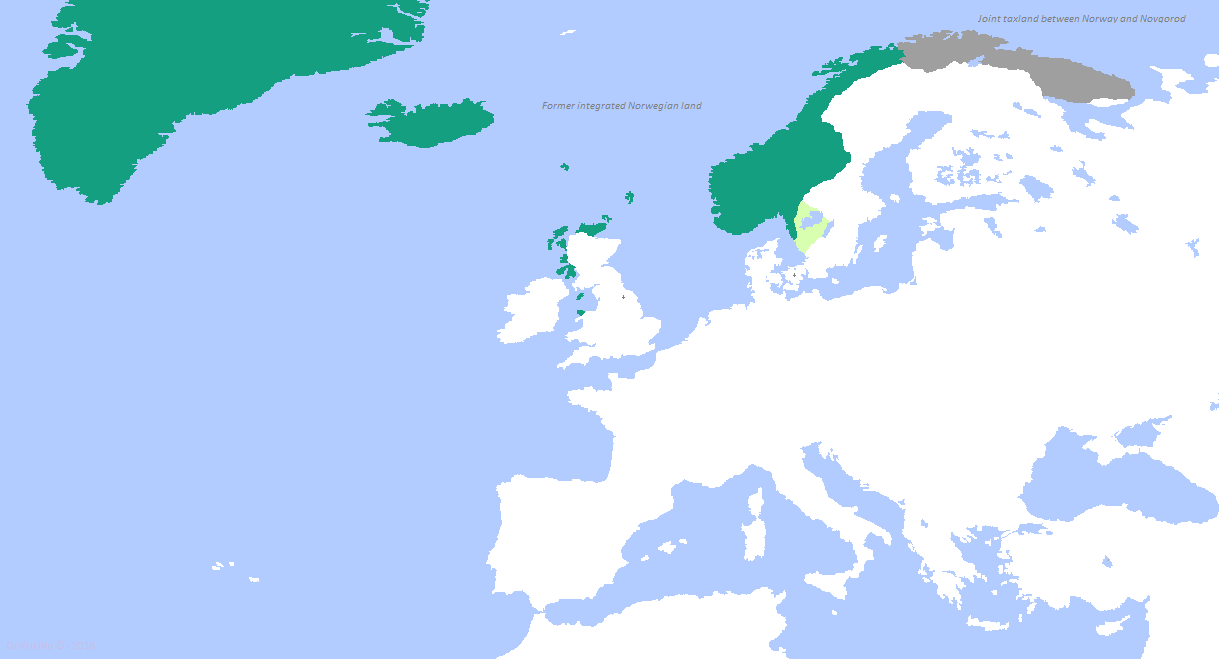

The regime looked nostalgically to the

The regime looked nostalgically to the High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the periodization, period of European history that lasted from AD 1000 to 1300. The High Middle Ages were preceded by the Early Middle Ages and were followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended ...

of the country's history, known in Norwegian historiography

Historiography is the study of the methods of historians in developing history as an academic discipline, and by extension is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiography of a specific topic covers how historians h ...

as ''Norgesveldet'', during which Norwegian territory extended beyond its current borders. Quisling envisioned an extension of the Norwegian state by its annexation of the Kola peninsula

The Kola Peninsula (russian: Кольский полуостров, Kolsky poluostrov; sjd, Куэлнэгк нёа̄ррк) is a peninsula in the extreme northwest of Russia, and one of the largest peninsulas of Europe. Constituting the bulk ...

with its small Norwegian minority, so a Greater Norway spanning the entire North European

The northern region of Europe has several definitions. A restrictive definition may describe Northern Europe as being roughly north of the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, which is about 54°N, or may be based on other geographical factors ...

coastline could be created. Further expansion was expected in Northern Finland, to link the Kola peninsula with Finnmark

Finnmark (; se, Finnmárku ; fkv, Finmarku; fi, Ruija ; russian: Финнмарк) was a county in the northern part of Norway, and it is scheduled to become a county again in 2024.

On 1 January 2020, Finnmark was merged with the neighbour ...

: Nasjonal Samling leaders had mixed views on the post-war Finnish-Norwegian border, but the potential Norwegian annexation of at least the Finnish municipalities of Petsamo Petsamo may refer to:

* Petsamo Province, a province of Finland from 1921 to 1922

* Petsamo, Tampere, a district in Tampere, Finland

* Pechengsky District

Pechengsky District (russian: Пе́ченгский райо́н; fi, Petsamo; no, Peisen ...

(Norwegian: ''Petsjenga'') and Inari (Norwegian: ''Enare'') was under consideration.

Nasjonal Samling publications called for the annexation of the historically Norwegian Swedish provinces of Jämtland

Jämtland (; no, Jemtland or , ; Jamtish: ''Jamtlann''; la, Iemptia) is a historical province () in the centre of Sweden in northern Europe. It borders Härjedalen and Medelpad to the south, Ångermanland to the east, Lapland to the nort ...

( Norwegian: ''Jemtland''), Härjedalen (Norwegian: ''Herjedalen'', see also '' Øst-Trøndelag'') and Bohuslän

Bohuslän (; da, Bohuslen; no, Båhuslen) is a Swedish province in Götaland, on the northernmost part of the country's west coast. It is bordered by Dalsland to the northeast, Västergötland to the southeast, the Skagerrak arm of the North ...

(Norwegian: ''Båhuslen'') In March 1944, Quisling met with Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the '' Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previo ...

general Rudolf Bamler, and urged the Germans to invade Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic countries, Nordic c ...

from Finnish Lapland (using the forces delegated to the German Lapland Army) and through the Baltic as a preemptive strike against Sweden joining the war on the Allied side.Hans Fredrik Dahl (1999). ''Quisling: a study in treachery''. Cambridge University Press, p. 34/ref> Quisling's proposal was sent to both OKW chief

Alfred Jodl

Alfred Josef Ferdinand Jodl (; 10 May 1890 – 16 October 1946) was a German '' Generaloberst'' who served as the chief of the Operations Staff of the '' Oberkommando der Wehrmacht'' – the German Armed Forces High Command – throughout Worl ...

and SS leader Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

.

Quisling and Jonas Lie, leader of the Germanic SS in Norway, also furthered irredentist

Irredentism is usually understood as a desire that one state annexes a territory of a neighboring state. This desire is motivated by ethnic reasons (because the population of the territory is ethnically similar to the population of the parent st ...

Norwegian claims to the Faroes

The Faroe Islands ( ), or simply the Faroes ( fo, Føroyar ; da, Færøerne ), are a North Atlantic island group and an autonomous territory of the Kingdom of Denmark.

They are located north-northwest of Scotland, and about halfway betw ...

(Norwegian: ''Færøyene''), Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its ...

(Norwegian: ''Island''), Orkney

Orkney (; sco, Orkney; on, Orkneyjar; nrn, Orknøjar), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated off the north coast of the island of Great Britain. Orkney is 10 miles (16 km) north ...

(Norwegian: ''Orknøyene''), Shetland

Shetland, also called the Shetland Islands and formerly Zetland, is a subarctic archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands and Norway. It is the northernmost region of the United Kingdom.

The islands lie about to the n ...

(Norwegian: ''Hjaltland''), the Outer Hebrides

The Outer Hebrides () or Western Isles ( gd, Na h-Eileanan Siar or or ("islands of the strangers"); sco, Waster Isles), sometimes known as the Long Isle/Long Island ( gd, An t-Eilean Fada, links=no), is an island chain off the west coas ...

(historically a part of the Norse Kingdom of Mann and the Isles

The Kingdom of the Isles consisted of the Isle of Man, the Hebrides and the islands of the Firth of Clyde from the 9th to the 13th centuries AD. The islands were known to the Norse as the , or "Southern Isles" as distinct from the or Nort ...

under the name ''Sørøyene'', "South Islands") and Franz Josef Land

, native_name =

, image_name = Map of Franz Josef Land-en.svg

, image_caption = Map of Franz Josef Land

, image_size =

, map_image = Franz Josef Land location-en.svg

, map_caption = Location of Franz Josef ...

(earlier claimed by Norway under the name ''Fridtjof Nansen

Fridtjof Wedel-Jarlsberg Nansen (; 10 October 186113 May 1930) was a Norwegian polymath and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. He gained prominence at various points in his life as an explorer, scientist, diplomat, and humanitarian. He led the team t ...

Land''), most of which were former Norwegian territories passed on to Danish rule after the dissolution of Denmark-Norway in 1814, while the rest were former Viking Age

The Viking Age () was the period during the Middle Ages when Norsemen known as Vikings undertook large-scale raiding, colonizing, conquest, and trading throughout Europe and reached North America. It followed the Migration Period and the Germ ...

settlements. Norway had already claimed a part of Eastern Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland ...

in 1931 (under the name '' Eirik Raudes Land''), but the claim was extended during the occupation period to cover Greenland as a whole. During the spring of 1941, Quisling laid out plans to "reconquer" the island using a task force of a hundred men, but the Germans deemed this plan unfeasible. In the person of propaganda minister Gulbrand Lunde

Gulbrand Oscar Johan Lunde (14 September 1901, Bergen – 26 October 1942, Våge, Rauma, Norway) was a Norwegian councillor of state in the NS government of Vidkun Quisling in 1940, acting councillor of state 1940-1941 and minister 1941–194 ...

the Norwegian puppet government further lay claim to the North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north ...

and South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole, Terrestrial South Pole or 90th Parallel South, is one of the two points where Earth's axis of rotation intersects its surface. It is the southernmost point on Earth and lies antipod ...

s. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Norway had gained prestige as a nation active in polar expedition: the South Pole was first reached by the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen (, ; ; 16 July 1872 – ) was a Norwegian explorer of polar regions. He was a key figure of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

Born in Borge, Østfold, Norway, Amundsen beg ...

in 1911, and in 1939 Norway had claimed a region of Antarctica under the name Queen Maud Land

Queen Maud Land ( no, Dronning Maud Land) is a roughly region of Antarctica claimed by Norway as a dependent territory. It borders the claimed British Antarctic Territory 20° west and the Australian Antarctic Territory 45° east. In addi ...

( no, Dronning Maud Land).

After Germany's invasion

An invasion is a military offensive in which large numbers of combatants of one geopolitical entity aggressively enter territory owned by another such entity, generally with the objective of either: conquering; liberating or re-establishing ...

of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

preparations were made for establishing Norwegian colonies

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the '' metropolitan state'' ...

in Northern Russia. Quisling designated the area reserved for Norwegian colonization as '' Bjarmeland'', a reference to the name featured in the Norse sagas

is a series of science fantasy role-playing video games by Square Enix. The series originated on the Game Boy in 1989 as the creation of Akitoshi Kawazu at Square. It has since continued across multiple platforms, from the Super NES to t ...

for Northern Russia.Dahl (1999), p. 296

Dissolution

Quisling's regime ceased to exist in 1945, with the end of World War II in Europe. Norway was still under occupation in May 1945, but Vidkun Quisling and most of his ministers surrendered atMøllergata 19

Møllergata 19 is an address in Oslo, Norway where the city's main police station and jail was located. The address gained notoriety during the German occupation from 1940 to 1945, when the Nazi security police kept its headquarters here. This is ...

police station on 9 May, one day after Germany's surrender. The new Norwegian unification government tried him on 20 August for numerous crimes; he was convicted on 10 September and was executed by firing squad on 24 October 1945. Other Nazi collaborators, as well as Germans accused of war crimes, were also arrested and tried during this legal purge.

Ministers of the Quisling regime

The ministers of the Quisling regime in 1942 were:

* Eivind Blehr (Minister of Trade and Minister of Supplies)

*

The ministers of the Quisling regime in 1942 were:

* Eivind Blehr (Minister of Trade and Minister of Supplies)

*Thorstein Fretheim

Thorstein John Ohnstad Fretheim (10 May 1886 – 29 June 1971) was a Norway, Norwegian acting councillor of state in the Nasjonal Samling, NS Quisling regime, government of Vidkun Quisling 1940–1941, and minister 1941–1945. Fretheim was ...

(Minister of Agriculture)

*Rolf Jørgen Fuglesang

Rolf Jørgen Fuglesang (31 January 1909, Fredrikstad – 25 November 1988) was a Norway, Norwegian secretary to the Nasjonal Samling Quisling regime, government of Vidkun Quisling 1940–1941 and minister 1941–1942 and 1942–1945. He was also P ...

(Minister of Party Affairs)

*Albert Viljam Hagelin

Albert Viljam Hagelin (24 April 1881 – 25 May 1946) was a Norwegian businessman and opera singer who became the Minister of Domestic Affairs in the Quisling regime, the puppet government headed by Vidkun Quisling during Germany's World W ...

(Minister of Domestic Affairs)

* Tormod Hustad (Minister of Labour)

* Kjeld Stub Irgens (Minister of Shipping)

* Jonas Lie (Minister of Police)

* Johan Andreas Lippestad (Minister of Social Affairs)

*Gulbrand Lunde

Gulbrand Oscar Johan Lunde (14 September 1901, Bergen – 26 October 1942, Våge, Rauma, Norway) was a Norwegian councillor of state in the NS government of Vidkun Quisling in 1940, acting councillor of state 1940-1941 and minister 1941–194 ...

(Minister of Culture)

* Frederik Prytz (Minister of Finance)

*Sverre Riisnæs

Sverre Parelius Riisnæs (6 November 1897 - 21 June 1988) was a Norwegian people, Norwegian jurist and public prosecutor. He was a member of the Collaborationism, collaborationist Quisling regime, government ''Nasjonal Samling'' in Occupation of No ...

(Minister of Justice)

*Ragnar Skancke

Ragnar Sigvald Skancke (9 November 1890 – 28 August 1948) was the Norwegian Minister for Church and Educational Affairs in Vidkun Quisling's Nasjonal Samling government during World War II. Shot for treason in the legal purges following th ...

(Minister for Church and Educational Affairs)

*Axel Heiberg Stang

Axel Heiberg Stang (21 February 1904 – 11 November 1974) was a Norwegian landowner and forester who served as a councillor of state, and later a minister, in the Nasjonal Samling government of Vidkun Quisling.

Early life and career

He was b ...

(Minister of the Labour Service and Sports)

The Quisling regime's leadership saw significant reshuffling and replacements during its existence. When Gulbrand Lunde died in 1942, Rolf Jørgen Fuglesang took over his ministry as well as retaining his own. Eivind Blehr's two ministries were merged in 1943 as the Ministry of Commerce. On 4 November 1943 Alf Whist

Alf Larsen Whist (6 August 1880 – 16 July 1962) was a Norwegian businessperson and politician for Nasjonal Samling.

Pre-war life and career

He was born in Fredrikshald as a son of Svend Larsen (1833–1893) and Sofie Mathilde Laumann (1842 ...

joined the government as a minister without portfolio

A minister without portfolio is either a government minister with no specific responsibilities or a minister who does not head a particular ministry. The sinecure is particularly common in countries ruled by coalition governments and a cabinet ...

.

Tormod Hustad was replaced by Hans Skarphagen on 1 February 1944. Both Kjeld Stub Irgens and Eivind Blehr were fired in June 1944. Their former ministries were merged and placed under the control of Alf Whist as Minister of Commerce. On 8 November 1944, Albert Viljam Hagelin was fired from his position and replaced by Arnvid Vasbotten. When Frederik Prytz died in February 1945, he was replaced by Per von Hirsch. Thorstein Fretheim was fired on 21 April 1945, to be replaced by Trygve Dehli Laurantzon.

References

Further reading

*Andenaes, Johs. ''Norway and the Second World War'' (1966) * Dahl, Hans Fredrik. ''Quisling: a study in treachery'' (Cambridge University Press, 1999) * Mann, Chris. ''British Policy and Strategy Towards Norway, 1941–45'' (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012) * Riste, Olav, and Berit Nøkleby. ''Norway 1940–45: the resistance movement'' (Tanum, 1970) * Vigness, Paul Gerhardt. ''The German Occupation of Norway'' (Vantage Press, 1970) {{Cabinets of Norway 1905-1945 Norway in World War II Government of Norway 1942 establishments in Norway 1945 disestablishments in Norway States and territories established in 1942 States and territories disestablished in 1945 Nasjonal Samling Cabinets established in 1942 Cabinets disestablished in 1945 Vidkun Quisling Client states of Nazi Germany German occupation of Norway Axis powers Collaboration with the Axis Powers Totalitarian states