Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and The Five on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In mid- to late-19th-century Russia,

In mid- to late-19th-century Russia,

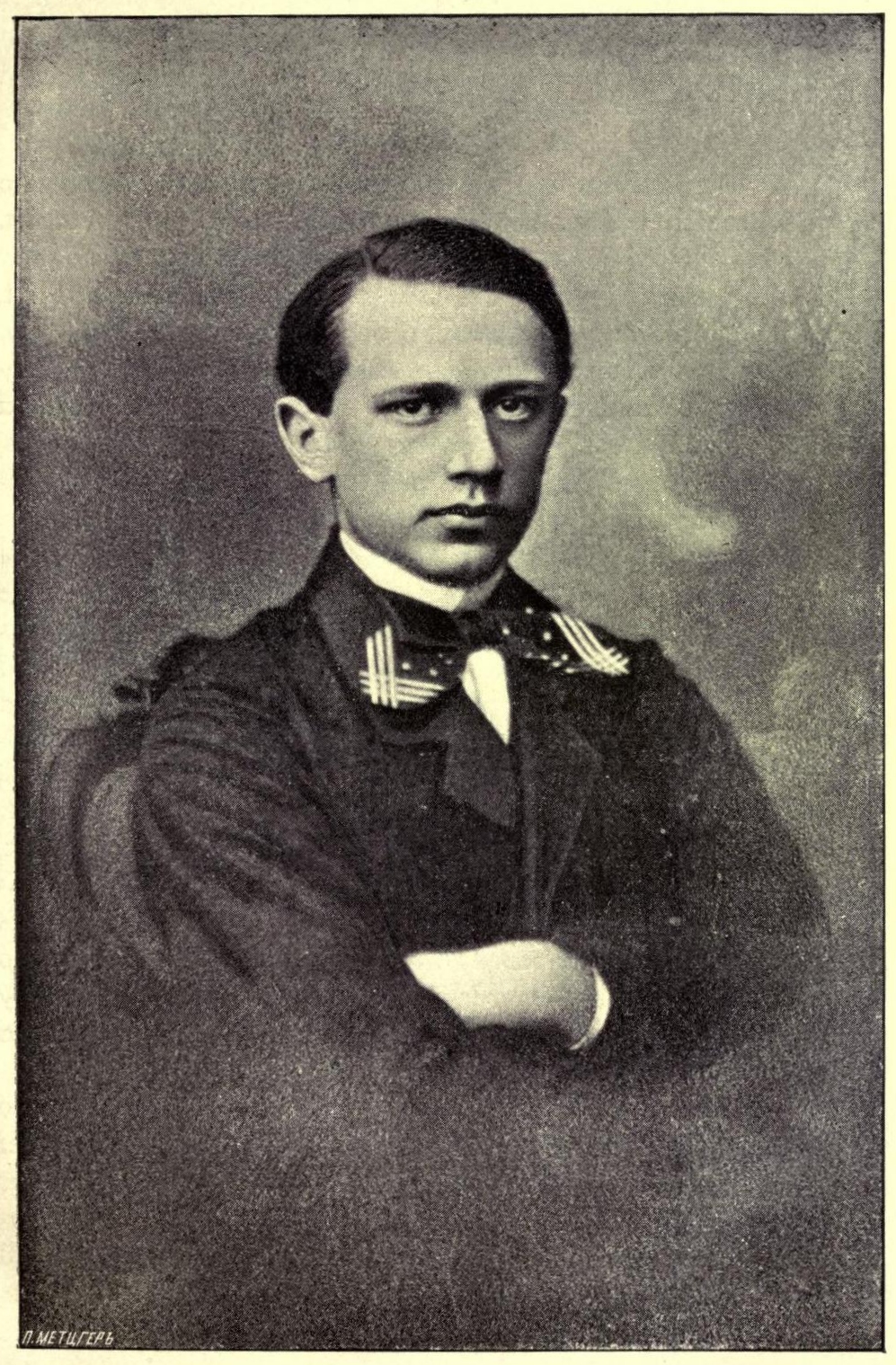

Tchaikovsky was born in 1840 in

Tchaikovsky was born in 1840 in

Around Christmas 1855, Glinka was visited by

Around Christmas 1855, Glinka was visited by

Anton Rubinstein was a famous Russian pianist who had lived, performed and composed in Western and Central Europe before he returned to Russia in 1858. He saw Russia as a musical desert compared to

Anton Rubinstein was a famous Russian pianist who had lived, performed and composed in Western and Central Europe before he returned to Russia in 1858. He saw Russia as a musical desert compared to

In 1867, Rubinstein handed over the directorship of the Conservatory to Zaremba. Later that year he resigned his conductorship of the Russian Music Society orchestra, to be replaced by Balakirev. Tchaikovsky had already promised his ''Characteristic Dances'' (then called ''Dances of the Hay Maidens'') from his opera '' The Voyevoda'' to the society. In submitting the manuscript (and perhaps mindful of Cui's review of the cantata), Tchaikovsky included a note to Balakirev that ended with a request for a word of encouragement should the ''Dances'' not be performed.

At this point The Five as a unit was dispersing. Mussorgsky and Rimsky-Korsakov wanted to remove themselves from Balakirev's influence, which they now found stifling, and go in their individual directions as composers. Balakirev might have sensed a potential new disciple in Tchaikovsky. He explained in his reply from Saint Petersburg that while he preferred to give his opinions in person and at length to press his points home, he was couching his reply "with complete frankness", adding, with a deft touch of flattery, that he felt that Tchaikovsky was "a fully fledged artist" and that he looked forward to discussing the piece with him on an upcoming trip to Moscow.

These letters set the tone for Tchaikovsky's relationship with Balakirev over the next two years. At the end of this period, in 1869, Tchaikovsky was a 28-year-old professor at the Moscow Conservatory. Having written his first symphony and an opera, he next composed a symphonic poem entitled '' Fatum''. Initially pleased with the piece when Nikolai Rubinstein conducted it in Moscow, Tchaikovsky dedicated it to Balakirev and sent it to him to conduct in Saint Petersburg. ''Fatum'' received only a lukewarm reception there. Balakirev wrote a detailed letter to Tchaikovsky in which he explained what he felt were defects in ''Fatum'' but also gave some encouragement. He added that he considered the dedication of the music to him as "precious to me as a sign of your sympathy towards me—and I feel a great weakness for you". Tchaikovsky was too self-critical not to see the truth behind these comments. He accepted Balakirev's criticism, and the two continued to correspond. Tchaikovsky would later destroy the score of ''Fatum''. (The score would be reconstructed posthumously by using the orchestral parts.)Brown, ''Man and Music'', 46.

In 1867, Rubinstein handed over the directorship of the Conservatory to Zaremba. Later that year he resigned his conductorship of the Russian Music Society orchestra, to be replaced by Balakirev. Tchaikovsky had already promised his ''Characteristic Dances'' (then called ''Dances of the Hay Maidens'') from his opera '' The Voyevoda'' to the society. In submitting the manuscript (and perhaps mindful of Cui's review of the cantata), Tchaikovsky included a note to Balakirev that ended with a request for a word of encouragement should the ''Dances'' not be performed.

At this point The Five as a unit was dispersing. Mussorgsky and Rimsky-Korsakov wanted to remove themselves from Balakirev's influence, which they now found stifling, and go in their individual directions as composers. Balakirev might have sensed a potential new disciple in Tchaikovsky. He explained in his reply from Saint Petersburg that while he preferred to give his opinions in person and at length to press his points home, he was couching his reply "with complete frankness", adding, with a deft touch of flattery, that he felt that Tchaikovsky was "a fully fledged artist" and that he looked forward to discussing the piece with him on an upcoming trip to Moscow.

These letters set the tone for Tchaikovsky's relationship with Balakirev over the next two years. At the end of this period, in 1869, Tchaikovsky was a 28-year-old professor at the Moscow Conservatory. Having written his first symphony and an opera, he next composed a symphonic poem entitled '' Fatum''. Initially pleased with the piece when Nikolai Rubinstein conducted it in Moscow, Tchaikovsky dedicated it to Balakirev and sent it to him to conduct in Saint Petersburg. ''Fatum'' received only a lukewarm reception there. Balakirev wrote a detailed letter to Tchaikovsky in which he explained what he felt were defects in ''Fatum'' but also gave some encouragement. He added that he considered the dedication of the music to him as "precious to me as a sign of your sympathy towards me—and I feel a great weakness for you". Tchaikovsky was too self-critical not to see the truth behind these comments. He accepted Balakirev's criticism, and the two continued to correspond. Tchaikovsky would later destroy the score of ''Fatum''. (The score would be reconstructed posthumously by using the orchestral parts.)Brown, ''Man and Music'', 46.

Balakirev's despotism strained the relationship between him and Tchaikovsky but both men still appreciated each other's abilities.Brown, ''New Grove Russian Masters'', 157–158. Despite their friction, Balakirev proved the only man to persuade Tchaikovsky to rewrite a work several times, as he would with ''

Balakirev's despotism strained the relationship between him and Tchaikovsky but both men still appreciated each other's abilities.Brown, ''New Grove Russian Masters'', 157–158. Despite their friction, Balakirev proved the only man to persuade Tchaikovsky to rewrite a work several times, as he would with ''

In 1871, Nikolai Zaremba resigned from the directorship of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory. His successor, Mikhaíl Azanchevsky, was more progressive-minded musically and wanted new blood to freshen up teaching in the Conservatory. He offered Rimsky-Korsakov a professorship in Practical Composition and Instrumentation (orchestration), as well as leadership of the Orchestra Class. Balakirev, who had formerly opposed academicism with tremendous vigor, encouraged him to assume the post, thinking it might be useful having one of his own in the midst of the enemy camp.

Nevertheless, by the time of his appointment, Rimsky-Korsakov had become painfully aware of his technical shortcomings as a composer; he later wrote, "I was a dilettante and knew nothing". Moreover, he had come to a creative dead-end upon completing his opera '' The Maid of Pskov'' and realized that developing a solid musical technique was the only way he could continue composing. He turned to Tchaikovsky for advice and guidance. When Rimsky-Korsakov underwent a change in attitude on music education and began his own intensive studies privately, his fellow nationalists accused him of throwing away his Russian heritage to compose fugues and sonatas. Tchaikovsky continued to support him morally. He told Rimsky-Korsakov that he fully applauded what he was doing and admired both his artistic modesty and his strength of character.

Before Rimsky-Korsakov went to the Conservatory, in March 1868, Tchaikovsky wrote a review of his '' Fantasy on Serbian Themes''. In discussing this work, Tchaikovsky compared it to the only other Rimsky-Korsakov piece he had heard so far, the First Symphony, mentioning "its charming orchestration ... its structural novelty, and most of all ... the freshness of its purely Russian harmonic turns ... immediately howingMr. Rimsky-Korsakov to be a remarkable symphonic talent". Tchaikovsky's notice, worded in precisely a way to find favor within the Balakirev circle, did exactly that. He met the rest of The Five on a visit to Balakirev's house in Saint Petersburg the following month. The meeting went well. Rimsky-Korsakov later wrote,

In 1871, Nikolai Zaremba resigned from the directorship of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory. His successor, Mikhaíl Azanchevsky, was more progressive-minded musically and wanted new blood to freshen up teaching in the Conservatory. He offered Rimsky-Korsakov a professorship in Practical Composition and Instrumentation (orchestration), as well as leadership of the Orchestra Class. Balakirev, who had formerly opposed academicism with tremendous vigor, encouraged him to assume the post, thinking it might be useful having one of his own in the midst of the enemy camp.

Nevertheless, by the time of his appointment, Rimsky-Korsakov had become painfully aware of his technical shortcomings as a composer; he later wrote, "I was a dilettante and knew nothing". Moreover, he had come to a creative dead-end upon completing his opera '' The Maid of Pskov'' and realized that developing a solid musical technique was the only way he could continue composing. He turned to Tchaikovsky for advice and guidance. When Rimsky-Korsakov underwent a change in attitude on music education and began his own intensive studies privately, his fellow nationalists accused him of throwing away his Russian heritage to compose fugues and sonatas. Tchaikovsky continued to support him morally. He told Rimsky-Korsakov that he fully applauded what he was doing and admired both his artistic modesty and his strength of character.

Before Rimsky-Korsakov went to the Conservatory, in March 1868, Tchaikovsky wrote a review of his '' Fantasy on Serbian Themes''. In discussing this work, Tchaikovsky compared it to the only other Rimsky-Korsakov piece he had heard so far, the First Symphony, mentioning "its charming orchestration ... its structural novelty, and most of all ... the freshness of its purely Russian harmonic turns ... immediately howingMr. Rimsky-Korsakov to be a remarkable symphonic talent". Tchaikovsky's notice, worded in precisely a way to find favor within the Balakirev circle, did exactly that. He met the rest of The Five on a visit to Balakirev's house in Saint Petersburg the following month. The meeting went well. Rimsky-Korsakov later wrote,

Tchaikovsky played the finale of his Second Symphony, subtitled the ''Little Russian'', at a gathering at Rimsky-Korsakov's house in Saint Petersburg on 7 January 1873, before the official premiere of the entire work. To his brother Modest, he wrote, " e whole company almost tore me to pieces with rapture—and Madame Rimskaya-Korsakova begged me in tears to let her arrange it for piano duet". Rimskaya-Korsakova was a noted pianist, composer and arranger in her own right, transcribing works by other members of the ''kuchka'' as well as those of her husband and Tchaikovsky's ''Romeo and Juliet''. Borodin was present and may have approved of the work himself.Brown, ''Early Years'', 283 Also present was Vladimir Stasov. Impressed by what he had heard, Stasov asked Tchaikovsky what he would consider writing next, and would soon influence the composer in writing the symphonic poem ''The Tempest''.

What endeared the ''Little Russian'' to the ''kuchka'' was not simply that Tchaikovsky had used Ukrainian folk songs as melodic material. It was how, especially in the outer movements, he allowed the unique characteristics of Russian folk song to dictate symphonic form. This was a goal toward which the ''kuchka'' strived, both collectively and individually. Tchaikovsky, with his Conservatory grounding, could sustain such development longer and more cohesively than his colleagues in the ''kuchka''. (Though the comparison may seem unfair, Tchaikovsky authority David Brown has pointed out that, because of their similar time-frames, the finale of the ''Little Russian'' shows what Mussorgsky could have done with "The Great Gate of Kiev" from ''

Tchaikovsky played the finale of his Second Symphony, subtitled the ''Little Russian'', at a gathering at Rimsky-Korsakov's house in Saint Petersburg on 7 January 1873, before the official premiere of the entire work. To his brother Modest, he wrote, " e whole company almost tore me to pieces with rapture—and Madame Rimskaya-Korsakova begged me in tears to let her arrange it for piano duet". Rimskaya-Korsakova was a noted pianist, composer and arranger in her own right, transcribing works by other members of the ''kuchka'' as well as those of her husband and Tchaikovsky's ''Romeo and Juliet''. Borodin was present and may have approved of the work himself.Brown, ''Early Years'', 283 Also present was Vladimir Stasov. Impressed by what he had heard, Stasov asked Tchaikovsky what he would consider writing next, and would soon influence the composer in writing the symphonic poem ''The Tempest''.

What endeared the ''Little Russian'' to the ''kuchka'' was not simply that Tchaikovsky had used Ukrainian folk songs as melodic material. It was how, especially in the outer movements, he allowed the unique characteristics of Russian folk song to dictate symphonic form. This was a goal toward which the ''kuchka'' strived, both collectively and individually. Tchaikovsky, with his Conservatory grounding, could sustain such development longer and more cohesively than his colleagues in the ''kuchka''. (Though the comparison may seem unfair, Tchaikovsky authority David Brown has pointed out that, because of their similar time-frames, the finale of the ''Little Russian'' shows what Mussorgsky could have done with "The Great Gate of Kiev" from ''

The Five was among the myriad of subjects Tchaikovsky discussed with his benefactress,

The Five was among the myriad of subjects Tchaikovsky discussed with his benefactress,

Tchaikovsky finished his final revision of ''Romeo and Juliet'' in 1880, and felt it a courtesy to send a copy of the score to Balakirev. Balakirev, however, had dropped out of the music scene in the early 1870s and Tchaikovsky had lost touch with him. He asked the publisher Bessel to forward a copy to Balakirev. A year later Balakirev replied. In the same letter that he thanked Tchaikovsky profusely for the score, Balakirev suggested "the programme for a symphony which you would handle wonderfully well", a detailed plan for a symphony based on Lord Byron's '' Manfred''. Originally drafted by Stasov in 1868 for Hector Berlioz as a sequel to that composer's ''

Tchaikovsky finished his final revision of ''Romeo and Juliet'' in 1880, and felt it a courtesy to send a copy of the score to Balakirev. Balakirev, however, had dropped out of the music scene in the early 1870s and Tchaikovsky had lost touch with him. He asked the publisher Bessel to forward a copy to Balakirev. A year later Balakirev replied. In the same letter that he thanked Tchaikovsky profusely for the score, Balakirev suggested "the programme for a symphony which you would handle wonderfully well", a detailed plan for a symphony based on Lord Byron's '' Manfred''. Originally drafted by Stasov in 1868 for Hector Berlioz as a sequel to that composer's ''

In November 1887, Tchaikovsky arrived in Saint Petersburg in time to hear several of the Russian Symphony Concerts, one of which included the first complete performance of the final version of his First Symphony and another the premiere of the revised version of Rimsky-Korsakov's Third Symphony.Brown, ''Final Years'', 91. Before this visit he had spent much time keeping in touch with Rimsky-Korsakov and those around him. Rimsky-Korsakov, along with Alexander Glazunov, Anatoly Lyadov and several other nationalistically-minded composers and musicians, had formed a group called the Belyayev circle. This group was named after timber merchant Mitrofan Belyayev, an amateur musician who became an influential music patron and publisher after he had taken an interest in Glazunov's work. During Tchaikovsky's visit, he spent much time in the company of these men, and his somewhat fraught relationship with The Five would meld into a more harmonious one with the Belyayev circle. This relationship would last until his death in late 1893.Poznansky, 564.

As for The Five, the group had long since dispersed, Mussorgsky had died in 1881 and Borodin had followed in 1887. Cui continued to write negative reviews of Tchaikovsky's music but was seen by the composer as merely a critical irritant. Balakirev lived in isolation and was confined to the musical sidelines. Only Rimsky-Korsakov remained fully active as a composer.

A side benefit of Tchaikovsky's friendship with Glazunov, Lyadov and Rimsky-Korsakov was an increased confidence in his own abilities as a composer, along with a willingness to let his musical works stand alongside those of his contemporaries. Tchaikovsky wrote to von Meck in January 1889, after being once again well represented in Belyayev's concerts, that he had "always tried to place myself ''outside'' all parties and to show in every way possible that I love and respect every honorable and gifted public figure in music, whatever his tendency", and that he considered himself "flattered to appear on the concert platform" beside composers in the Belyayev circle. This was an acknowledgment of wholehearted readiness for his music to be heard with that of these composers, delivered in a tone of implicit confidence that there were no comparisons from which to fear.

In November 1887, Tchaikovsky arrived in Saint Petersburg in time to hear several of the Russian Symphony Concerts, one of which included the first complete performance of the final version of his First Symphony and another the premiere of the revised version of Rimsky-Korsakov's Third Symphony.Brown, ''Final Years'', 91. Before this visit he had spent much time keeping in touch with Rimsky-Korsakov and those around him. Rimsky-Korsakov, along with Alexander Glazunov, Anatoly Lyadov and several other nationalistically-minded composers and musicians, had formed a group called the Belyayev circle. This group was named after timber merchant Mitrofan Belyayev, an amateur musician who became an influential music patron and publisher after he had taken an interest in Glazunov's work. During Tchaikovsky's visit, he spent much time in the company of these men, and his somewhat fraught relationship with The Five would meld into a more harmonious one with the Belyayev circle. This relationship would last until his death in late 1893.Poznansky, 564.

As for The Five, the group had long since dispersed, Mussorgsky had died in 1881 and Borodin had followed in 1887. Cui continued to write negative reviews of Tchaikovsky's music but was seen by the composer as merely a critical irritant. Balakirev lived in isolation and was confined to the musical sidelines. Only Rimsky-Korsakov remained fully active as a composer.

A side benefit of Tchaikovsky's friendship with Glazunov, Lyadov and Rimsky-Korsakov was an increased confidence in his own abilities as a composer, along with a willingness to let his musical works stand alongside those of his contemporaries. Tchaikovsky wrote to von Meck in January 1889, after being once again well represented in Belyayev's concerts, that he had "always tried to place myself ''outside'' all parties and to show in every way possible that I love and respect every honorable and gifted public figure in music, whatever his tendency", and that he considered himself "flattered to appear on the concert platform" beside composers in the Belyayev circle. This was an acknowledgment of wholehearted readiness for his music to be heard with that of these composers, delivered in a tone of implicit confidence that there were no comparisons from which to fear.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky , group=n ( ; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer of the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music would make a lasting impression internationally. He wrote some of the most popu ...

and a group of composer

A composer is a person who writes music. The term is especially used to indicate composers of Western classical music, or those who are composers by occupation. Many composers are, or were, also skilled performers of music.

Etymology and Def ...

s known as The Five had differing opinions as to whether Russian classical music

Russian classical music is a genre of classical music related to Russia's culture, people, or character. The 19th-century romantic period saw the largest development of this genre, with the emergence in particular of The Five, a group of composer ...

should be composed following Western or native practices. Tchaikovsky wanted to write professional compositions of such quality that they would stand up to Western scrutiny and thus transcend national barriers, yet remain distinctively Russian in melody, rhythm and other compositional characteristics. The Five, made up of composers Mily Balakirev

Mily Alexeyevich Balakirev (russian: Милий Алексеевич Балакирев,BGN/PCGN transliteration of Russian: Miliy Alekseyevich Balakirev; ALA-LC system: ''Miliĭ Alekseevich Balakirev''; ISO 9 system: ''Milij Alekseevič Balakir ...

, Alexander Borodin

Alexander Porfiryevich Borodin ( rus, link=no, Александр Порфирьевич Бородин, Aleksandr Porfir’yevich Borodin , p=ɐlʲɪkˈsandr pɐrˈfʲi rʲjɪvʲɪtɕ bərɐˈdʲin, a=RU-Alexander Porfiryevich Borodin.ogg, ...

, César Cui

César Antonovich Cui ( rus, Це́зарь Анто́нович Кюи́, , ˈt͡sjezərʲ ɐnˈtonəvʲɪt͡ɕ kʲʊˈi, links=no, Ru-Tsezar-Antonovich-Kyui.ogg; french: Cesarius Benjaminus Cui, links=no, italic=no; 13 March 1918) was a Ru ...

, Modest Mussorgsky

Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky ( rus, link=no, Модест Петрович Мусоргский, Modest Petrovich Musorgsky , mɐˈdɛst pʲɪˈtrovʲɪtɕ ˈmusərkskʲɪj, Ru-Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky version.ogg; – ) was a Russian compo ...

, and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov . At the time, his name was spelled Николай Андреевичъ Римскій-Корсаковъ. la, Nicolaus Andreae filius Rimskij-Korsakov. The composer romanized his name as ''Nicolas Rimsk ...

, sought to produce a specifically Russian kind of art music

Art music (alternatively called classical music, cultivated music, serious music, and canonic music) is music considered to be of high phonoaesthetic value. It typically implies advanced structural and theoretical considerationsJacques Siron, ...

, rather than one that imitated older European music or relied on European-style conservatory training. While Tchaikovsky himself used folk songs in some of his works, for the most part he tried to follow Western practices of composition, especially in terms of tonality and tonal progression. Also, unlike Tchaikovsky, none of The Five were academically trained in composition; in fact, their leader, Balakirev, considered academicism a threat to musical imagination. Along with critic Vladimir Stasov

Vladimir Vasilievich Stasov (also Stassov; rus, Влади́мир Васи́льевич Ста́сов; 14 January Adoption_of_the_Gregorian_calendar#Adoption_in_Eastern_Europe.html" ;"title="/nowiki> O.S._2_January.html" ;"title="Adoption of ...

, who supported The Five, Balakirev attacked relentlessly both the Saint Petersburg Conservatory

The N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov Saint Petersburg State Conservatory (russian: Санкт-Петербургская государственная консерватория имени Н. А. Римского-Корсакова) (formerly known as th ...

, from which Tchaikovsky had graduated, and its founder Anton Rubinstein

Anton Grigoryevich Rubinstein ( rus, Антон Григорьевич Рубинштейн, r=Anton Grigor'evič Rubinštejn; ) was a Russian pianist, composer and conductor who became a pivotal figure in Russian culture when he founded the Sa ...

, orally and in print.Maes, 39.

As Tchaikovsky had become Rubinstein's best-known student, he was initially considered by association as a natural target for attack, especially as fodder for Cui's printed critical reviews. This attitude changed slightly when Rubinstein left the Saint Petersburg musical scene in 1867. In 1869 Tchaikovsky entered into a working relationship with Balakirev; the result was Tchaikovsky's first recognized masterpiece, the fantasy-overture ''Romeo and Juliet

''Romeo and Juliet'' is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare early in his career about the romance between two Italian youths from feuding families. It was among Shakespeare's most popular plays during his lifetime and, along with ''Ham ...

'', a work which The Five wholeheartedly embraced.Brown, ''Man and Music'', 49. When Tchaikovsky wrote a positive review of Rimsky-Korsakov's '' Fantasy on Serbian Themes'' he was welcomed into the circle, despite concerns about the academic nature of his musical background.Maes, 44. The finale of his Second Symphony, nicknamed the ''Little Russian'', was also received enthusiastically by the group on its first performance in 1872.

Tchaikovsky remained friendly but never intimate with most of The Five, ambivalent about their music; their goals and aesthetics did not match his.Maes, 49. He took pains to ensure his musical independence from them as well as from the conservative faction at the Conservatory—an outcome facilitated by his acceptance of a professorship at the Moscow Conservatory

The Moscow Conservatory, also officially Moscow State Tchaikovsky Conservatory (russian: Московская государственная консерватория им. П. И. Чайковского, link=no) is a musical educational inst ...

offered to him by Nikolai Rubinstein

Nikolai Grigoryevich Rubinstein (russian: Николай Григорьевич Рубинштейн; – ) was a Russian pianist, conductor, and composer. He was the younger brother of Anton Rubinstein and a close friend of Pyotr Ilyich Tc ...

, Anton's brother.Holden, 64. When Rimsky-Korsakov was offered a professorship at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, it was to Tchaikovsky that he turned for advice and guidance.Maes, 48. Later, when Rimsky-Korsakov was under pressure from his fellow nationalists for his change in attitude on music education and his own intensive studies in music,Schonberg, 363. Tchaikovsky continued to support him morally, told him that he fully applauded what he was doing and admired both his artistic modesty and his strength of character.Rimsky-Korsakov, 157 ft. 30. In the 1880s, long after the members of The Five had gone their separate ways, another group called the Belyayev circle

The Belyayev circle (russian: Беляевский кружок) was a society of Russian musicians who met in Saint Petersburg, Russia between 1885 and 1908, and whose members included Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Alexander Glazunov, Vladimir Stasov, ...

took up where they left off. Tchaikovsky enjoyed close relations with the leading members of this group—Alexander Glazunov

Alexander Konstantinovich Glazunov; ger, Glasunow (, 10 August 1865 – 21 March 1936) was a Russian composer, music teacher, and conductor of the late Russian Romantic period. He was director of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory between 190 ...

, Anatoly Lyadov

Anatoly Konstantinovich Lyadov (russian: Анато́лий Константи́нович Ля́дов; ) was a Russian composer, teacher, and conductor (music), conductor.

Biography

Lyadov was born in 1855 in Saint Petersburg, St. Petersbur ...

and, by then, Rimsky-Korsakov.Rimsky-Korsakov, 308.

Prologue: growing debate

With the exception ofMikhail Glinka

Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka ( rus, link=no, Михаил Иванович Глинка, Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka., mʲɪxɐˈil ɪˈvanəvʲɪdʑ ˈɡlʲinkə, Ru-Mikhail-Ivanovich-Glinka.ogg; ) was the first Russian composer to gain wide recogni ...

, who became the first "truly Russian" composer, the only music indigenous to Russia before Tchaikovsky's birthday in 1840 were folk and sacred music; the Russian Orthodox Church

, native_name_lang = ru

, image = Moscow July 2011-7a.jpg

, imagewidth =

, alt =

, caption = Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, Russia

, abbreviation = ROC

, type ...

's proscription of secular music had effectively stifled its development. Beginning in the 1830s, Russian intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the i ...

debated the issue of whether artists negated their Russianness when they borrowed from European culture or took vital steps toward renewing and developing Russian culture. Two groups sought to answer this question. Slavophile

Slavophilia (russian: Славянофильство) was an intellectual movement originating from the 19th century that wanted the Russian Empire to be developed on the basis of values and institutions derived from Russia's early history. Slavoph ...

s idealized Russian history before Peter the Great and claimed the country possessed a distinct culture, rooted in Byzantium

Byzantium () or Byzantion ( grc, Βυζάντιον) was an ancient Greek city in classical antiquity that became known as Constantinople in late antiquity and Istanbul today. The Greek name ''Byzantion'' and its Latinization ''Byzantium' ...

and spread by the Russian Orthodox Church. The ''Zapadniki'' ("Westernizers"), on the other hand, lauded Peter as a patriot who wanted to reform his country and bring it on a par with Europe. Looking forward instead of backward, they saw Russia as a youthful and inexperienced but with the potential of becoming the most advanced European civilization by borrowing from Europe and turning its liabilities into assets.

In 1836, Glinka's opera ''A Life for the Tsar

''A Life for the Tsar'' ( rus, "Жизнь за царя", italic=yes, Zhizn za tsarya ) is a "patriotic-heroic tragic opera" in four acts with an epilogue by Mikhail Glinka. During the Soviet era the opera was known under the name ''Ivan Susanin'' ...

'' was premiered in Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

. This was an event long-awaited by the intelligentsia. The opera was the first conceived by a Russian composer on a grand scale, set to a Russian text and patriotic in its appeal. Its plot fit neatly into the doctrine of Official Nationality being promulgated by Nicholas I, thus assuring Imperial approval. In formal and stylistic terms, ''A Life'' was very much an Italian opera but also showed a sophisticated thematic structure and a boldness in orchestral scoring. It was the first tragic opera to enter the Russian repertoire, with Ivan Susanin's death at the end underlining and adding gravitas to the patriotism running through the whole opera. (In Cavos's version, Ivan is spared at the last minute.)Maes, 22. It was also the first Russian opera where the music continued throughout, uninterrupted by spoken dialogue.Maes, 17; Taruskin, ''Grove Opera'', 2:447–448, 4:99–100. Moreover—and this is what amazed contemporaries about the work—the music included folk songs and Russian national idioms, incorporating them into the drama. Glinka meant his use of folk songs to reflect the presence of popular characters in the opera, rather than an overt attempt at nationalism. Nor do they play a major part in the opera.Maes, 23. Nevertheless, despite a few derogatory comments about Glinka's use of "coachman's music," ''A Life'' became popular enough to earn obtain permanent repertory status, the first Russian opera to do so in that country.

Ironically, the success of Rossini

Gioachino Antonio Rossini (29 February 1792 – 13 November 1868) was an Italian composer who gained fame for his 39 operas, although he also wrote many songs, some chamber music and piano pieces, and some sacred music. He set new standards ...

's ''Semiramide

''Semiramide'' () is an opera in two acts by Gioachino Rossini.

The libretto by Gaetano Rossi is based on Voltaire's tragedy ''Semiramis'', which in turn was based on the legend of Semiramis of Assyria. The opera was first performed at La Fe ...

'' earlier the same season was what allowed ''A Life'' to be staged at all, with virtually all the cast from ''Semiramide'' retained for ''A Life''. Despite ''A Life's'' success, the furor over ''Semiramide'' aroused an overwhelming demand for Italian opera. This proved a setback for Russian opera in general and particularly for Glinka's next opera, '' Ruslan and Lyudmila'' when it was produced in 1842. Its failure prompted Glinka to leave Russia; he died in exile.

Drawing sides

Despite Glinka's international attention, which included the admiration ofLiszt

Franz Liszt, in modern usage ''Liszt Ferenc'' . Liszt's Hungarian passport spelled his given name as "Ferencz". An orthographic reform of the Hungarian language in 1922 (which was 36 years after Liszt's death) changed the letter "cz" to simpl ...

and Berlioz for his musicMaes, 28. and his heralding by the latter as "among the outstanding composers of his time", Russian aristocrats remained focused exclusively on foreign music.Campbell, ''New Grove (2001)'', 10:3. Music itself was bound by class structure, and except for a modest role in public life was still considered a privilege of the aristocracy. Nobles spent enormous sums on musical performances for their exclusive enjoyment and hosted visiting artists such as Clara Schumann

Clara Josephine Schumann (; née Wieck; 13 September 1819 – 20 May 1896) was a German pianist, composer, and piano teacher. Regarded as one of the most distinguished pianists of the Romantic era, she exerted her influence over the course of a ...

and Franz Liszt but there were no ongoing concert societies, no critical press and no public eagerly anticipating new works. No competent level of music education existed. Private tutors were available in some cities but tended to be badly trained. Anyone desiring a quality education had to travel abroad. Composer and pianist Anton Rubinstein

Anton Grigoryevich Rubinstein ( rus, Антон Григорьевич Рубинштейн, r=Anton Grigor'evič Rubinštejn; ) was a Russian pianist, composer and conductor who became a pivotal figure in Russian culture when he founded the Sa ...

's founding of the Russian Musical Society

The Russian Musical Society (RMS) (russian: Русское музыкальное общество) was the first music school in Russia open to the general public. It was launched in 1859 by the Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna and Anton Rubinstei ...

in 1859 and the Saint Petersburg Conservatory

The N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov Saint Petersburg State Conservatory (russian: Санкт-Петербургская государственная консерватория имени Н. А. Римского-Корсакова) (formerly known as th ...

three years later were giant steps toward remedying this situation but also proved highly controversial ones.Maes, 42. Among this group was a young legal clerk named Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky.

Tchaikovsky

Votkinsk

Votkinsk (russian: Во́ткинск; udm, Вотка, ''Votka'') is an industrial town in the Udmurt Republic, Russia. Population:

History

It was established in April 1759, initially as a center for metallurgical enterprises, and the economic ...

, a small town in present-day Udmurtia

Udmurtia (russian: Удму́ртия, r=Udmúrtiya, p=ʊˈdmurtʲɪjə; udm, Удмуртия, ''Udmurtija''), or the Udmurt Republic (russian: Удмуртская Республика, udm, Удмурт Республика, Удмурт � ...

, formerly the Imperial Russian

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. Th ...

province of Vyatka. A precocious pupil, he began piano lessons at the age of five, and could read music as adeptly as his teacher within three years. However, his parents' passion for his musical talent soon cooled. In 1850, the family decided to send Tchaikovsky to the Imperial School of Jurisprudence in Saint Petersburg. This establishment mainly served the lesser nobility or gentry, and would prepare him for a career as a civil servant. As the minimum age for acceptance was 12, Tchaikovsky was sent by his family to board at the Imperial School of Jurisprudence's preparatory school in Saint Petersburg, from his family home in Alapayevsk

Alapayevsk (russian: Алапа́евск) is a town in Sverdlovsk Oblast, Russia, located at the confluence of the Neyva and Alapaikha rivers. Population: 44,263 ( 2002 census); 50,060 ( 1989 census); 49,000 (1968).

History

Alapayevsk is ...

. Once Tchaikovsky came of age for acceptance, he was transferred to the Imperial School of Jurisprudence to begin a seven-year course of studies.

Music was not a priority at the School, but Tchaikovsky regularly attended the theater and the opera with other students. He was fond of works by Rossini, Bellini, Verdi

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi (; 9 or 10 October 1813 – 27 January 1901) was an Italian composer best known for his operas. He was born near Busseto to a provincial family of moderate means, receiving a musical education with the ...

and Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 17565 December 1791), baptised as Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart, was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period. Despite his short life, his rapid pace of composition r ...

. Piano manufacturer Franz Becker made occasional visits to the School as a token music teacher. This was the only formal music instruction Tchaikovsky received there. From 1855 the composer's father, Ilya Tchaikovsky, funded private lessons with Rudolph Kündinger, a well-known piano teacher from Nuremberg

Nuremberg ( ; german: link=no, Nürnberg ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the second-largest city of the German state of Bavaria after its capital Munich, and its 518,370 (2019) inhabitants make it the 14th-largest ...

, and questioned Kündinger about a musical career for his son. Kündinger replied that nothing suggested a potential composer or even a fine performer. Tchaikovsky was told to finish his course and then try for a post in the Ministry of Justice.

Tchaikovsky graduated on 25 May 1859 with the rank of titular counselor, a low rung on the civil service ladder. On 15 June, he was appointed to the Ministry of Justice in Saint Petersburg. Six months later he became a junior assistant and two months after that, a senior assistant. Tchaikovsky remained there for the rest of his three-year civil service career.

In 1861, Tchaikovsky attended classes in music theory

Music theory is the study of the practices and possibilities of music. ''The Oxford Companion to Music'' describes three interrelated uses of the term "music theory". The first is the " rudiments", that are needed to understand music notation (k ...

organized by the Russian Musical Society and taught by Nikolai Zaremba. A year later he followed Zaremba to the Saint Petersburg Conservatory. Tchaikovsky would not give up his Ministry post "until I am quite certain that I am destined to be a musician rather than a civil servant." From 1862 to 1865 he studied harmony

In music, harmony is the process by which individual sounds are joined together or composed into whole units or compositions. Often, the term harmony refers to simultaneously occurring frequencies, pitches ( tones, notes), or chords. Howeve ...

, counterpoint

In music, counterpoint is the relationship between two or more musical lines (or voices) which are harmonically interdependent yet independent in rhythm and melodic contour. It has been most commonly identified in the European classical tra ...

and fugue

In music, a fugue () is a contrapuntal compositional technique in two or more voices, built on a subject (a musical theme) that is introduced at the beginning in imitation (repetition at different pitches) and which recurs frequently in the co ...

with Zaremba, while Rubinstein taught him instrumentation and composition.Brown, ''Man and Music'', 20; Warrack, 36–38. In 1863 he abandoned his civil service career and studied music full-time, graduating in December 1865.

The Five

Around Christmas 1855, Glinka was visited by

Around Christmas 1855, Glinka was visited by Alexander Ulybyshev

Alexander Dmitryevich Ulybyshev or Alexandre Oulibicheff (Russian: Александр Дмитриевич Улыбышев) (1794-1858) was a wealthy landowner, an influential biographer of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and the most important early patr ...

, a rich Russian amateur critic, and his 18-year-old protégé Mily Balakirev, who was reportedly on his way to becoming a great pianist.Maes, 37. Balakirev played his fantasy based on themes from ''A Life for the Tsar'' for Glinka. Glinka, pleasantly surprised, praised Balakirev as a musician with a bright future.

In 1856, Balakirev and critic Vladimir Stasov, who publicly espoused a nationalist agenda for Russian arts, started gathering young composers through whom to spread ideas and gain a following.Maes, 38. First to meet with them that year was César Cui, an army officer who specialized in the science of fortifications. Modest Mussorgsky, a Preobrazhensky Lifeguard officer, joined them in 1857; Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, a naval cadet, in 1861; and Alexander Borodin, a chemist, in 1862. Balakirev, Borodin, Cui, Mussorgsky and Rimsky-Korsakov composed in their spare time, and all five of them were young men in 1862, with Rimsky-Korsakov at just 18 the youngest and Borodin the oldest at 28.Figes, 179. All five were essentially self-taught and eschewed conservative and "routine" musical techniques.Garden, ''New Grove (2001)'', 8:913. They became known as the ''kuchka'', variously translated as The Five, The Russian Five and The Mighty Handful after a review written by Stasov about their music. Stasov wrote, "May God grant that he audience retainsfor ever a memory of how much poetry, feeling, talent and ability is possessed by the small but already mighty handful 'moguchaya kuchka''of Russian musicians". The term ''moguchaya kuchka'', which literally means "mighty little heap", stuck, although Stasov referred to them in print generally as the "New Russian School."

The aim of this group was to create an independent Russian school of music in the footsteps of Glinka. They were to strive for "national character," gravitate toward "Oriental" (by that they meant near-Eastern) melodies and favor program music over absolute Absolute may refer to:

Companies

* Absolute Entertainment, a video game publisher

* Absolute Radio, (formerly Virgin Radio), independent national radio station in the UK

* Absolute Software Corporation, specializes in security and data risk manag ...

—in other words, symphonic poem

A symphonic poem or tone poem is a piece of orchestral music, usually in a single continuous movement, which illustrates or evokes the content of a poem, short story, novel, painting, landscape, or other (non-musical) source. The German term ''T ...

s and related music over symphonies, concertos and chamber music.Taruskin, ''Stravinsky'', 24. To create this Russian style of classical music, Stasov wrote that the group incorporated four characteristics. The first was a rejection of academicism and fixed Western forms of composition. The second was the incorporation of musical elements from eastern nations inside the Russian empire; this was a quality that would later become known as musical orientalism. The third was a progressive and anti-academic approach to music. The fourth was the incorporation of compositional devices linked with folk music. These four points would distinguish the Five from its contemporaries in the cosmopolitan camp of composition.

Rubinstein and the Conservatory

Anton Rubinstein was a famous Russian pianist who had lived, performed and composed in Western and Central Europe before he returned to Russia in 1858. He saw Russia as a musical desert compared to

Anton Rubinstein was a famous Russian pianist who had lived, performed and composed in Western and Central Europe before he returned to Russia in 1858. He saw Russia as a musical desert compared to Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

, Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

and Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as ...

, whose music conservatories he had visited. Musical life flourished in those places; composers were held in high regard, and musicians were wholeheartedly devoted to their art. With a similar ideal in mind for Russia, he had conceived an idea for a conservatory in Russia years before his 1858 return, and had finally aroused the interest of influential people to help him realize the idea.

Rubinstein's first step was to found the Russian Musical Society (RMS) in 1859. Its objectives were to educate people in music, cultivate their musical tastes and develop their talents in that area of their lives. The first priority of the RMS acted was to expose to the public the music of native composers. In addition to a considerable amount of Western European music, works by Mussorgsky and Cui were premiered by the RMS under Rubinstein's baton. A few weeks after the Society's premiere concert, Rubinstein started organizing music classes, which were open to everyone. Interest in these classes grew until Rubinstein founded the Saint Petersburg Conservatory in 1862.Maes, 35.

According to musicologist Francis Maes, Rubinstein could not be accused of any lack of artistic integrity. He fought for change and progress in musical life in Russia. Only his musical tastes were conservative—from Haydn

Franz Joseph Haydn ( , ; 31 March 173231 May 1809) was an Austrian composer of the Classical period. He was instrumental in the development of chamber music such as the string quartet and piano trio. His contributions to musical form have led ...

, Mozart and Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classic ...

to the early Romantics up to Chopin. Liszt and Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most op ...

were not included. Neither did he welcome many ideas then new about music, including the role of nationalism in classical music. For Rubinstein, national music existed only in folk song and folk dance. There was no place for national music in larger works, especially not in opera.Maes, 52–53. Rubinstein's public reaction to the attacks was simply not to react. His classes and concerts were well attended, so he felt no reply was actually necessary. He even forbade his students to take sides.

With The Five

As The Five's campaign against Rubinstein continued in the press, Tchaikovsky found himself almost as much a target as his former teacher. Cui reviewed the performance of Tchaikovsky's graduationcantata

A cantata (; ; literally "sung", past participle feminine singular of the Italian verb ''cantare'', "to sing") is a vocal composition with an instrumental accompaniment, typically in several movements, often involving a choir.

The meaning o ...

and lambasted the composer as "utterly feeble.... If he had any talent at all ... it would surely at some point in the piece have broken free of the chains imposed by the Conservatory."Holden, 45. The review's effect on the sensitive composer was devastating. Eventually, an uneasy truce developed as Tchaikovsky became friendly with Balakirev and eventually with the other four composers of the group. A working relationship between Balakirev and Tchaikovsky resulted in ''Romeo and Juliet''. The Five's approval of this work was further followed by their enthusiasm for Tchaikovsky's Second Symphony. Subtitled the ''Little Russian'' (Little Russia was the term at that time for what is now called Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inva ...

) for its use of Ukrainian folk songs, the symphony in its initial version also used several compositional devices similar to those used by the Five in their work. Stasov suggested the subject of Shakespeare's '' The Tempest'' to Tchaikovsky, who wrote a tone poem

A symphonic poem or tone poem is a piece of orchestral music, usually in a single continuous movement, which illustrates or evokes the content of a poem, short story, novel, painting, landscape, or other (non-musical) source. The German term ''T ...

based on this subject. After a lapse of several years, Balakirev reentered Tchaikovsky's creative life; the result was Tchaikovsky's ''Manfred'' Symphony, composed to a program after Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824), known simply as Lord Byron, was an English romantic poet and peer. He was one of the leading figures of the Romantic movement, and has been regarded as among the ...

originally written by Stasov and supplied by Balakirev. Overall, however, Tchaikovsky continued down an independent creative path, traveling a middle course between those of his nationalistic peers and the traditionalists.

Balakirev

Initial correspondence

In 1867, Rubinstein handed over the directorship of the Conservatory to Zaremba. Later that year he resigned his conductorship of the Russian Music Society orchestra, to be replaced by Balakirev. Tchaikovsky had already promised his ''Characteristic Dances'' (then called ''Dances of the Hay Maidens'') from his opera '' The Voyevoda'' to the society. In submitting the manuscript (and perhaps mindful of Cui's review of the cantata), Tchaikovsky included a note to Balakirev that ended with a request for a word of encouragement should the ''Dances'' not be performed.

At this point The Five as a unit was dispersing. Mussorgsky and Rimsky-Korsakov wanted to remove themselves from Balakirev's influence, which they now found stifling, and go in their individual directions as composers. Balakirev might have sensed a potential new disciple in Tchaikovsky. He explained in his reply from Saint Petersburg that while he preferred to give his opinions in person and at length to press his points home, he was couching his reply "with complete frankness", adding, with a deft touch of flattery, that he felt that Tchaikovsky was "a fully fledged artist" and that he looked forward to discussing the piece with him on an upcoming trip to Moscow.

These letters set the tone for Tchaikovsky's relationship with Balakirev over the next two years. At the end of this period, in 1869, Tchaikovsky was a 28-year-old professor at the Moscow Conservatory. Having written his first symphony and an opera, he next composed a symphonic poem entitled '' Fatum''. Initially pleased with the piece when Nikolai Rubinstein conducted it in Moscow, Tchaikovsky dedicated it to Balakirev and sent it to him to conduct in Saint Petersburg. ''Fatum'' received only a lukewarm reception there. Balakirev wrote a detailed letter to Tchaikovsky in which he explained what he felt were defects in ''Fatum'' but also gave some encouragement. He added that he considered the dedication of the music to him as "precious to me as a sign of your sympathy towards me—and I feel a great weakness for you". Tchaikovsky was too self-critical not to see the truth behind these comments. He accepted Balakirev's criticism, and the two continued to correspond. Tchaikovsky would later destroy the score of ''Fatum''. (The score would be reconstructed posthumously by using the orchestral parts.)Brown, ''Man and Music'', 46.

In 1867, Rubinstein handed over the directorship of the Conservatory to Zaremba. Later that year he resigned his conductorship of the Russian Music Society orchestra, to be replaced by Balakirev. Tchaikovsky had already promised his ''Characteristic Dances'' (then called ''Dances of the Hay Maidens'') from his opera '' The Voyevoda'' to the society. In submitting the manuscript (and perhaps mindful of Cui's review of the cantata), Tchaikovsky included a note to Balakirev that ended with a request for a word of encouragement should the ''Dances'' not be performed.

At this point The Five as a unit was dispersing. Mussorgsky and Rimsky-Korsakov wanted to remove themselves from Balakirev's influence, which they now found stifling, and go in their individual directions as composers. Balakirev might have sensed a potential new disciple in Tchaikovsky. He explained in his reply from Saint Petersburg that while he preferred to give his opinions in person and at length to press his points home, he was couching his reply "with complete frankness", adding, with a deft touch of flattery, that he felt that Tchaikovsky was "a fully fledged artist" and that he looked forward to discussing the piece with him on an upcoming trip to Moscow.

These letters set the tone for Tchaikovsky's relationship with Balakirev over the next two years. At the end of this period, in 1869, Tchaikovsky was a 28-year-old professor at the Moscow Conservatory. Having written his first symphony and an opera, he next composed a symphonic poem entitled '' Fatum''. Initially pleased with the piece when Nikolai Rubinstein conducted it in Moscow, Tchaikovsky dedicated it to Balakirev and sent it to him to conduct in Saint Petersburg. ''Fatum'' received only a lukewarm reception there. Balakirev wrote a detailed letter to Tchaikovsky in which he explained what he felt were defects in ''Fatum'' but also gave some encouragement. He added that he considered the dedication of the music to him as "precious to me as a sign of your sympathy towards me—and I feel a great weakness for you". Tchaikovsky was too self-critical not to see the truth behind these comments. He accepted Balakirev's criticism, and the two continued to correspond. Tchaikovsky would later destroy the score of ''Fatum''. (The score would be reconstructed posthumously by using the orchestral parts.)Brown, ''Man and Music'', 46.

Writing ''Romeo and Juliet''

Balakirev's despotism strained the relationship between him and Tchaikovsky but both men still appreciated each other's abilities.Brown, ''New Grove Russian Masters'', 157–158. Despite their friction, Balakirev proved the only man to persuade Tchaikovsky to rewrite a work several times, as he would with ''

Balakirev's despotism strained the relationship between him and Tchaikovsky but both men still appreciated each other's abilities.Brown, ''New Grove Russian Masters'', 157–158. Despite their friction, Balakirev proved the only man to persuade Tchaikovsky to rewrite a work several times, as he would with ''Romeo and Juliet

''Romeo and Juliet'' is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare early in his career about the romance between two Italian youths from feuding families. It was among Shakespeare's most popular plays during his lifetime and, along with ''Ham ...

''.Brown, ''New Grove Russian Masters'', 158. At Balakirev's suggestion, Tchaikovsky based the work on Balakirev's ''King Lear'', a tragic overture in sonata form

Sonata form (also ''sonata-allegro form'' or ''first movement form'') is a musical structure generally consisting of three main sections: an exposition, a development, and a recapitulation. It has been used widely since the middle of the 18th c ...

after the example of Beethoven's concert overtures. It was Tchaikovsky's idea to reduce the plot to one central conflict and represent it musically with the binary structure of sonata form. However, the execution of that plot in the music we know today came only after two radical revisions. Balakirev discarded many of the early drafts Tchaikovsky sent him and, with the flurry of suggestions between the two men, the piece was constantly in the mail between Moscow and Saint Petersburg.Maes, 74.

Tchaikovsky allowed the first version to be premiered by Nikolai Rubinstein on 16 March 1870, after the composer had incorporated only some of Balakirev's suggestions. The premiere was a disaster. Stung by this rejection, Tchaikovsky took Balakirev's strictures to heart. He forced himself to reach beyond his musical training and rewrote much of the music into the form we know it today. ''Romeo'' would bring Tchaikovsky his first national and international acclaim and become a work the ''kuchka'' lauded unconditionally. On hearing the love theme from ''Romeo'', Stasov told the group, "There were five of you; now there are six". Such was the enthusiasm of the Five for ''Romeo'' that at their gatherings Balakirev was always asked to play it through at the piano. He did this so many times that he learned to perform it from memory.

Some critics, among them Tchaikovsky biographers Lawrence and Elisabeth Hanson, have wondered what would have happened if Tchaikovsky had joined Balakirev in 1862 instead of attending the Conservatory. They suggest that he might have developed much more quickly as an independent composer, and offer as proof the fact that Tchaikovsky did not write his first wholly distinct work until Balakirev goaded and inspired him to write ''Romeo''. How well Tchaikovsky might have developed in the long run is another matter. He owed much of his musical ability, including his skill at orchestration, to the thorough grounding in counterpoint, harmony and musical theory he received at the Conservatory. Without that grounding, Tchaikovsky might not have been able to write what would become his greatest works.

Rimsky-Korsakov

In 1871, Nikolai Zaremba resigned from the directorship of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory. His successor, Mikhaíl Azanchevsky, was more progressive-minded musically and wanted new blood to freshen up teaching in the Conservatory. He offered Rimsky-Korsakov a professorship in Practical Composition and Instrumentation (orchestration), as well as leadership of the Orchestra Class. Balakirev, who had formerly opposed academicism with tremendous vigor, encouraged him to assume the post, thinking it might be useful having one of his own in the midst of the enemy camp.

Nevertheless, by the time of his appointment, Rimsky-Korsakov had become painfully aware of his technical shortcomings as a composer; he later wrote, "I was a dilettante and knew nothing". Moreover, he had come to a creative dead-end upon completing his opera '' The Maid of Pskov'' and realized that developing a solid musical technique was the only way he could continue composing. He turned to Tchaikovsky for advice and guidance. When Rimsky-Korsakov underwent a change in attitude on music education and began his own intensive studies privately, his fellow nationalists accused him of throwing away his Russian heritage to compose fugues and sonatas. Tchaikovsky continued to support him morally. He told Rimsky-Korsakov that he fully applauded what he was doing and admired both his artistic modesty and his strength of character.

Before Rimsky-Korsakov went to the Conservatory, in March 1868, Tchaikovsky wrote a review of his '' Fantasy on Serbian Themes''. In discussing this work, Tchaikovsky compared it to the only other Rimsky-Korsakov piece he had heard so far, the First Symphony, mentioning "its charming orchestration ... its structural novelty, and most of all ... the freshness of its purely Russian harmonic turns ... immediately howingMr. Rimsky-Korsakov to be a remarkable symphonic talent". Tchaikovsky's notice, worded in precisely a way to find favor within the Balakirev circle, did exactly that. He met the rest of The Five on a visit to Balakirev's house in Saint Petersburg the following month. The meeting went well. Rimsky-Korsakov later wrote,

In 1871, Nikolai Zaremba resigned from the directorship of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory. His successor, Mikhaíl Azanchevsky, was more progressive-minded musically and wanted new blood to freshen up teaching in the Conservatory. He offered Rimsky-Korsakov a professorship in Practical Composition and Instrumentation (orchestration), as well as leadership of the Orchestra Class. Balakirev, who had formerly opposed academicism with tremendous vigor, encouraged him to assume the post, thinking it might be useful having one of his own in the midst of the enemy camp.

Nevertheless, by the time of his appointment, Rimsky-Korsakov had become painfully aware of his technical shortcomings as a composer; he later wrote, "I was a dilettante and knew nothing". Moreover, he had come to a creative dead-end upon completing his opera '' The Maid of Pskov'' and realized that developing a solid musical technique was the only way he could continue composing. He turned to Tchaikovsky for advice and guidance. When Rimsky-Korsakov underwent a change in attitude on music education and began his own intensive studies privately, his fellow nationalists accused him of throwing away his Russian heritage to compose fugues and sonatas. Tchaikovsky continued to support him morally. He told Rimsky-Korsakov that he fully applauded what he was doing and admired both his artistic modesty and his strength of character.

Before Rimsky-Korsakov went to the Conservatory, in March 1868, Tchaikovsky wrote a review of his '' Fantasy on Serbian Themes''. In discussing this work, Tchaikovsky compared it to the only other Rimsky-Korsakov piece he had heard so far, the First Symphony, mentioning "its charming orchestration ... its structural novelty, and most of all ... the freshness of its purely Russian harmonic turns ... immediately howingMr. Rimsky-Korsakov to be a remarkable symphonic talent". Tchaikovsky's notice, worded in precisely a way to find favor within the Balakirev circle, did exactly that. He met the rest of The Five on a visit to Balakirev's house in Saint Petersburg the following month. The meeting went well. Rimsky-Korsakov later wrote,

As a product of the Conservatory, Tchaikovsky was viewed rather negligently if not haughtily by our circle, and, owing to his being away from St. Petersburg, personal acquaintanceship was impossible....Rimsky-Korsakov added that "during the following years, when visiting St. Petersburg,chaikovsky Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky , group=n ( ; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer of the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music would make a lasting impression internationally. He wrote some of the most popu ...proved to be a pleasing and sympathetic man to talk with, one who knew how to be simple of manner and always speak with evident sincerity and heartiness. The evening of our first meetingchaikovsky Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky , group=n ( ; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer of the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music would make a lasting impression internationally. He wrote some of the most popu ...played for us, at Balakirev's request, the first movement of his Symphony in G minor chaikovsky's First Symphony it proved quite to our liking; and our former opinion of him changed and gave way to a more sympathetic one, although Tchaikovsky's Conservatory training still constituted a considerable barrier between him and us.Rimsky-Korsakov, 75.

chaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky , group=n ( ; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer of the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music would make a lasting impression internationally. He wrote some of the most popu ...

usually came to Balakirev's, and we saw him." Nevertheless, as much as Tchaikovsky may have desired acceptance from both The Five and the traditionalists, he needed the independence that Moscow afforded to find his own direction, away from both parties. This was especially true in light of Rimsky-Korsakov's comment about the "considerable barrier" of Tchaikovsky's Conservatory training, as well as Anton Rubinstein's opinion that Tchaikovsky had strayed too far from the examples of the great Western masters. Tchaikovsky was ready for the nourishment of new attitudes and styles so he could continue growing as a composer, and his brother Modest writes that he was impressed by the "force and vitality" in some of the Five's work.Tchaikovsky, Modest, abr. and trans. Newmarch, Rosa, ''The Life & Letters of Peter Ilich Tchaikovsky'' (1906). As quoted in Holden, 64. However, he was too balanced an individual to totally reject the best in the music and values that Zaremba and Rubinstein had cherished. In his brother Modest's opinion, Tchaikovsky's relations with the Saint Petersburg group resembled "those between two friendly neighboring states ... cautiously prepared to meet on common ground, but jealously guarding their separate interests".

Stasov and the ''Little Russian'' symphony

Tchaikovsky played the finale of his Second Symphony, subtitled the ''Little Russian'', at a gathering at Rimsky-Korsakov's house in Saint Petersburg on 7 January 1873, before the official premiere of the entire work. To his brother Modest, he wrote, " e whole company almost tore me to pieces with rapture—and Madame Rimskaya-Korsakova begged me in tears to let her arrange it for piano duet". Rimskaya-Korsakova was a noted pianist, composer and arranger in her own right, transcribing works by other members of the ''kuchka'' as well as those of her husband and Tchaikovsky's ''Romeo and Juliet''. Borodin was present and may have approved of the work himself.Brown, ''Early Years'', 283 Also present was Vladimir Stasov. Impressed by what he had heard, Stasov asked Tchaikovsky what he would consider writing next, and would soon influence the composer in writing the symphonic poem ''The Tempest''.

What endeared the ''Little Russian'' to the ''kuchka'' was not simply that Tchaikovsky had used Ukrainian folk songs as melodic material. It was how, especially in the outer movements, he allowed the unique characteristics of Russian folk song to dictate symphonic form. This was a goal toward which the ''kuchka'' strived, both collectively and individually. Tchaikovsky, with his Conservatory grounding, could sustain such development longer and more cohesively than his colleagues in the ''kuchka''. (Though the comparison may seem unfair, Tchaikovsky authority David Brown has pointed out that, because of their similar time-frames, the finale of the ''Little Russian'' shows what Mussorgsky could have done with "The Great Gate of Kiev" from ''

Tchaikovsky played the finale of his Second Symphony, subtitled the ''Little Russian'', at a gathering at Rimsky-Korsakov's house in Saint Petersburg on 7 January 1873, before the official premiere of the entire work. To his brother Modest, he wrote, " e whole company almost tore me to pieces with rapture—and Madame Rimskaya-Korsakova begged me in tears to let her arrange it for piano duet". Rimskaya-Korsakova was a noted pianist, composer and arranger in her own right, transcribing works by other members of the ''kuchka'' as well as those of her husband and Tchaikovsky's ''Romeo and Juliet''. Borodin was present and may have approved of the work himself.Brown, ''Early Years'', 283 Also present was Vladimir Stasov. Impressed by what he had heard, Stasov asked Tchaikovsky what he would consider writing next, and would soon influence the composer in writing the symphonic poem ''The Tempest''.

What endeared the ''Little Russian'' to the ''kuchka'' was not simply that Tchaikovsky had used Ukrainian folk songs as melodic material. It was how, especially in the outer movements, he allowed the unique characteristics of Russian folk song to dictate symphonic form. This was a goal toward which the ''kuchka'' strived, both collectively and individually. Tchaikovsky, with his Conservatory grounding, could sustain such development longer and more cohesively than his colleagues in the ''kuchka''. (Though the comparison may seem unfair, Tchaikovsky authority David Brown has pointed out that, because of their similar time-frames, the finale of the ''Little Russian'' shows what Mussorgsky could have done with "The Great Gate of Kiev" from ''Pictures at an Exhibition

''Pictures at an Exhibition'', french: Tableaux d'une exposition, link=no is a suite of ten piano pieces, plus a recurring, varied Promenade theme, composed by Russian composer Modest Mussorgsky in 1874. The piece is Mussorgsky's most famous pia ...

'' had he possessed academic training comparable to that of Tchaikovsky.)Brown, ''Early Years'', 265–269.

Tchaikovsky's private concerns about The Five

The Five was among the myriad of subjects Tchaikovsky discussed with his benefactress,

The Five was among the myriad of subjects Tchaikovsky discussed with his benefactress, Nadezhda von Meck

Nadezhda Filaretovna von Meck (russian: Надежда Филаретовна фон Мекк; 13 January 1894) was a Russian businesswoman who became an influential patron of the arts, especially music. She is best known today for her artistic ...

. By January 1878, when he wrote to Mrs. von Meck about its members, he had drifted far from their musical world and ideals. In addition, The Five's finest days had long passed. Despite considerable effort in writing operas and songs, Cui had become better known as a critic than as a composer, and even his critical efforts competed for time with his career as an army engineer and expert in the science of fortification

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere ...

. Balakirev had withdrawn completely from the musical scene, Mussorgsky was sinking ever deeper into alcoholism, and Borodin's creative activities increasingly took a back seat to his official duties as a professor of chemistry.Brown, ''Crisis Years'', 228.

Only Rimsky-Korsakov actively pursued a full-time musical career, and he was under increasing fire from his fellow nationalists for much the same reason as Tchaikovsky had been. Like Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov had found that, for his own artistic growth to continue unabated, he had to study and master Western classical forms and techniques. Borodin called it "apostasy

Apostasy (; grc-gre, ἀποστασία , 'a defection or revolt') is the formal disaffiliation from, abandonment of, or renunciation of a religion by a person. It can also be defined within the broader context of embracing an opinion that ...

", adding, "Many are grieved at present by the fact that Korsakov has turned back, has thrown himself into a study of musical antiquity. I do not bemoan it. It is understandable...." Mussorgsky was harsher: " e mighty ''kuchka'' had degenerated into soulless traitors."

Tchaikovsky's analysis of each of The Five was unsparing. According to Brown, while at least some of his observations may seem distorted and prejudiced, he also mentions some details which ring clear and true. His diagnosis of Rimsky-Korsakov's creative crisis is very accurate. He also calls Mussorgsky the most gifted musically of the Five, though Tchaikovsky could not appreciate the forms Mussorgsky's originality took. Nonetheless, Brown concludes that he badly underestimates Borodin's technique and gives Balakirev far less than his full due—all the more telling in light of Balakirev's help in conceiving and shaping ''Romeo and Juliet''.

Tchaikovsky wrote to Nadezhda von Meck that all of the ''kuchka'' were talented but also "infected to the core" with conceit and "a purely dilettantish confidence in their superiority." He went into some detail about Rimsky-Korsakov's epiphany and turnaround regarding musical training, and his efforts to remedy this situation for himself. Tchaikovsky then called Cui "a talented dilettante" whose music "has no originality, but is clever and graceful"; Borodin a man who "has talent, even a strong one, but it has perished through neglect ... and his technique is so weak that he cannot write a single line f musicwithout outside help"; Mussorgsky "a hopeless case", superior in talent but "narrow-minded, devoid of any urge towards self-perfection"; and Balakirev as one with "enormous talent" yet who had also "done much harm" as "the general inventor of all the theories of this strange group".

Balakirev returns

Tchaikovsky finished his final revision of ''Romeo and Juliet'' in 1880, and felt it a courtesy to send a copy of the score to Balakirev. Balakirev, however, had dropped out of the music scene in the early 1870s and Tchaikovsky had lost touch with him. He asked the publisher Bessel to forward a copy to Balakirev. A year later Balakirev replied. In the same letter that he thanked Tchaikovsky profusely for the score, Balakirev suggested "the programme for a symphony which you would handle wonderfully well", a detailed plan for a symphony based on Lord Byron's '' Manfred''. Originally drafted by Stasov in 1868 for Hector Berlioz as a sequel to that composer's ''

Tchaikovsky finished his final revision of ''Romeo and Juliet'' in 1880, and felt it a courtesy to send a copy of the score to Balakirev. Balakirev, however, had dropped out of the music scene in the early 1870s and Tchaikovsky had lost touch with him. He asked the publisher Bessel to forward a copy to Balakirev. A year later Balakirev replied. In the same letter that he thanked Tchaikovsky profusely for the score, Balakirev suggested "the programme for a symphony which you would handle wonderfully well", a detailed plan for a symphony based on Lord Byron's '' Manfred''. Originally drafted by Stasov in 1868 for Hector Berlioz as a sequel to that composer's ''Harold en Italie

''Harold en Italie,'' ''symphonie avec un alto principal'' (English: ''Harold in Italy,'' ''symphony with viola obbligato''), as the manuscript calls and describes it, is a four-movement orchestral work by Hector Berlioz, his Opus number, Opus 1 ...

'', the program had since been in Balakirev's care.Holden, 248–249.

Tchaikovsky declined the project at first, saying the subject left him cold. Balakirev persisted. "You must, of course, ''make an effort''", Balakirev exhorted, "take a more self-critical approach, don't hurry things".Holden, 249. Tchaikovsky's mind was changed two years later, in the Swiss Alps, while tending to his friend Iosif Kotek and after he had re-read ''Manfred'' in the milieu in which the poem is set. Once he returned home, Tchaikovsky revised the draft Balakirev had made from Stasov's program and began sketching the first movement.

The ''Manfred'' Symphony would cost Tchaikovsky more time, effort and soul-searching than anything else he would write, even the ''Pathetique'' Symphony. It also became the longest, most complex work he had written up to that point, and though it owes an obvious debt to Berlioz due to its program, Tchaikovsky was still able to make the theme of ''Manfred'' his own. Near the end of seven months of intensive effort, in late September 1885, he wrote Balakirev, "Never in my life, believe me, have I labored so long and hard, and felt so drained by my efforts. The Symphony is written in four movements, as per your program, although—forgive me—as much as I wanted to, I have not been able to keep all the keys and modulations you suggested ... It is of course dedicated to you".

Once he had finished the symphony, Tchaikovsky was reluctant to further tolerate Balakirev's interference, and severed all contact; he told his publisher P. Jurgenson

P. Jurgenson (in Russian: П. Юргенсон) was, in the early twentieth century, the largest publisher of classical sheet music in Russia.

History

Founded in 1861, the firm — in its original form, or as it was amalgamated in 1918 with ...

that he considered Balakirev a "madman". Tchaikovsky and Balakirev exchanged only a few formal, not overly friendly letters after this breach.Holden, 251.

Belyayev circle

In November 1887, Tchaikovsky arrived in Saint Petersburg in time to hear several of the Russian Symphony Concerts, one of which included the first complete performance of the final version of his First Symphony and another the premiere of the revised version of Rimsky-Korsakov's Third Symphony.Brown, ''Final Years'', 91. Before this visit he had spent much time keeping in touch with Rimsky-Korsakov and those around him. Rimsky-Korsakov, along with Alexander Glazunov, Anatoly Lyadov and several other nationalistically-minded composers and musicians, had formed a group called the Belyayev circle. This group was named after timber merchant Mitrofan Belyayev, an amateur musician who became an influential music patron and publisher after he had taken an interest in Glazunov's work. During Tchaikovsky's visit, he spent much time in the company of these men, and his somewhat fraught relationship with The Five would meld into a more harmonious one with the Belyayev circle. This relationship would last until his death in late 1893.Poznansky, 564.

As for The Five, the group had long since dispersed, Mussorgsky had died in 1881 and Borodin had followed in 1887. Cui continued to write negative reviews of Tchaikovsky's music but was seen by the composer as merely a critical irritant. Balakirev lived in isolation and was confined to the musical sidelines. Only Rimsky-Korsakov remained fully active as a composer.