Protoceratops andrewsi on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Protoceratops'' (; ) is a

In 1900

In 1900  After spending much of 1924 making plans for the next fieldwork seasons, in 1925 Andrews and team explored the Flaming Cliffs yet again. During this year more eggs and nests were collected, alongside well-preserved and complete specimens of ''Protoceratops''. By this time, ''Protoceratops'' had become one of the most abundant dinosaurs of the region with more than 100 specimens known, including skulls and skeletons of multiple individuals at different growth stages. Though more remains of ''Protoceratops'' were collected in later years of the expeditions, they were most abundant in the 1922 to 1925 seasons. Gregory and

After spending much of 1924 making plans for the next fieldwork seasons, in 1925 Andrews and team explored the Flaming Cliffs yet again. During this year more eggs and nests were collected, alongside well-preserved and complete specimens of ''Protoceratops''. By this time, ''Protoceratops'' had become one of the most abundant dinosaurs of the region with more than 100 specimens known, including skulls and skeletons of multiple individuals at different growth stages. Though more remains of ''Protoceratops'' were collected in later years of the expeditions, they were most abundant in the 1922 to 1925 seasons. Gregory and

Protoceratopsid remains were recovered in the 1970s from the Khulsan locality of the

Protoceratopsid remains were recovered in the 1970s from the Khulsan locality of the

As part of the Third Central Asiatic Expedition of 1923, Andrews and team discovered the holotype specimen of ''

As part of the Third Central Asiatic Expedition of 1923, Andrews and team discovered the holotype specimen of '' However, also during 1994, Norell and colleagues reported and briefly described a fossilized

However, also during 1994, Norell and colleagues reported and briefly described a fossilized

The

The

''Protoceratops'' was a relatively small-sized

''Protoceratops'' was a relatively small-sized

The

The

Furthermore, with the re-examinations of '' Turanoceratops'' in 2009 and ''

Furthermore, with the re-examinations of '' Turanoceratops'' in 2009 and ''

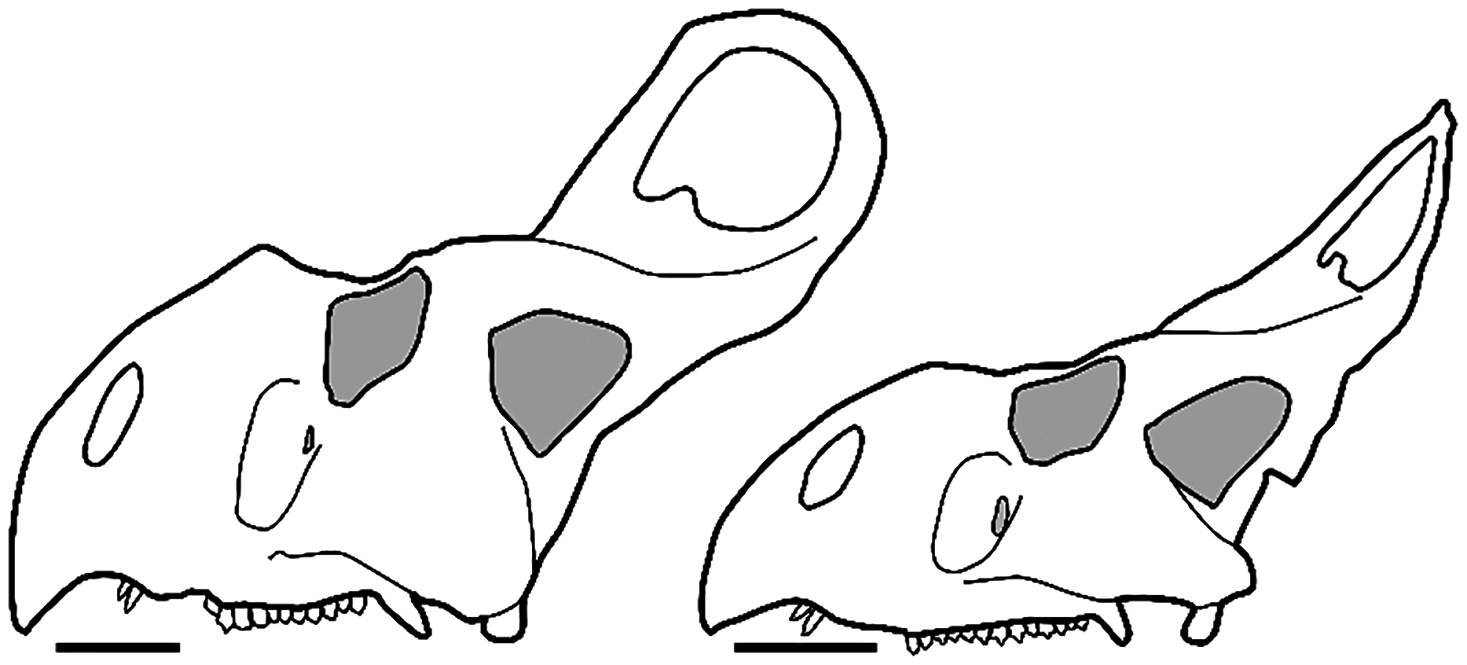

Longrich and team in 2010 indicated that highly derived morphology of ''P. hellenikorhinus''—when compared to ''P. andrewsi''—indicates that this species may represent a lineage of ''Protoceratops'' that had a longer evolutionary history compared to ''P. andrewsi'', or simply a direct descendant of ''P. andrewsi''. The difference in morphologies between ''Protoceratops'' also suggests that the nearby

Longrich and team in 2010 indicated that highly derived morphology of ''P. hellenikorhinus''—when compared to ''P. andrewsi''—indicates that this species may represent a lineage of ''Protoceratops'' that had a longer evolutionary history compared to ''P. andrewsi'', or simply a direct descendant of ''P. andrewsi''. The difference in morphologies between ''Protoceratops'' also suggests that the nearby

In 2017 Mototaka Saneyoshi with team analyzed several ''Protoceratops'' specimens from the

In 2017 Mototaka Saneyoshi with team analyzed several ''Protoceratops'' specimens from the

In 1996 Tereshchenko reconstructed the walking model of ''Protoceratops'' where he considered the most likely scenario to be ''Protoceratops'' as an obligate

In 1996 Tereshchenko reconstructed the walking model of ''Protoceratops'' where he considered the most likely scenario to be ''Protoceratops'' as an obligate

Longrich in 2010 proposed that ''Protoceratops'' may have used its hindlimbs to dig burrows or take shelter under

Longrich in 2010 proposed that ''Protoceratops'' may have used its hindlimbs to dig burrows or take shelter under

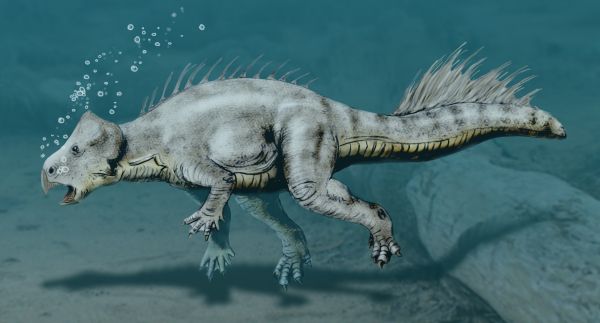

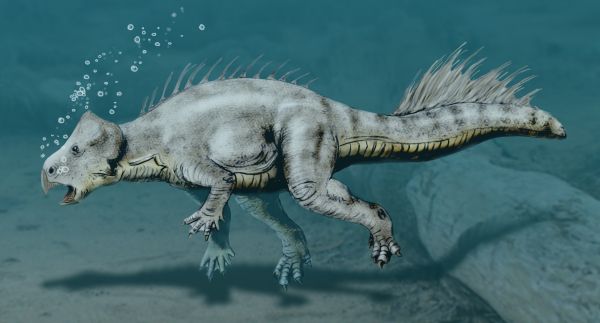

Gregory and Mook in 1925 suggested that ''Protoceratops'' was partially aquatic because of its large feet—being larger than the hands—and the very long neural spines found in the caudal (tail) vertebrae. Brown and Schlaikjer in 1940 and indicated that the expansion of the distal (lower) ischial end may reflect a strong ischiocaudalis muscle, which together with the high tail neural spines were used for

Gregory and Mook in 1925 suggested that ''Protoceratops'' was partially aquatic because of its large feet—being larger than the hands—and the very long neural spines found in the caudal (tail) vertebrae. Brown and Schlaikjer in 1940 and indicated that the expansion of the distal (lower) ischial end may reflect a strong ischiocaudalis muscle, which together with the high tail neural spines were used for  In 2011 during the description of ''

In 2011 during the description of ''

Brown and Schlaikjer in 1940 upon their large analysis of ''Protoceratops'' noted the potential presence of

Brown and Schlaikjer in 1940 upon their large analysis of ''Protoceratops'' noted the potential presence of  However, Leonardo Maiorino with team in 2015 performed a large geometric morphometric analysis using 29 skulls of ''P. andrewsi'' in order to evaluate actual sexual dimorphism. Obtained results indicated that other than the nasal horn—which remained as the only skull trait with potential sexual dimorphism—all previously suggested characters to differentiate hyphotetical males from females were more linked to ontogenic changes and intraspecific variation independent of sex, most notably the neck frill. The geometrics showed no consistent morphological differences between specimens that were regarded as males and females by previous authors, but also a slight support for differences in the rostrum across the sample. Maiorino and team nevertheless, cited that the typical regarded ''Protoceratops'' male, AMNH 6438, pretty much resembles the rostrum morphology of AMNH 6466, a typical regarded female. However, they suggested that authentic differences between sexes could be still present in the postcranial skeleton. Although previously suggested for ''P. hellenikorhinus'', the team argued that the sample used for this species was not sufficient, and given that sexual dimorphism was not recovered in ''P. andrewsi'', it is unlikely that it occurred in ''P. hellenikorhinus''.

In 2016 Hone and colleagues analyzed 37 skulls of ''P. andrewsi'', finding that the neck frill of ''Protoceratops'' (in both length and width) underwent positive allometry during ontongeny, that is, a faster growth/development of this region than the rest of the animal. The jugal bones also showed a trend towards an increase in relative size. These results suggest that they functioned as socio-sexual dominance signals, or, they were mostly used in display. The use of the frill as a displaying structure may be related to other anatomical features of ''Protoceratops'' such as the premaxillary teeth (at least for ''P. andrewsi'') which could have been used in display or intraspecific combat, or the high neural spines of tail. On the other hand, Hone and team argued that if neck frills were instead used for protective purposes, a large frill may have acted as an

However, Leonardo Maiorino with team in 2015 performed a large geometric morphometric analysis using 29 skulls of ''P. andrewsi'' in order to evaluate actual sexual dimorphism. Obtained results indicated that other than the nasal horn—which remained as the only skull trait with potential sexual dimorphism—all previously suggested characters to differentiate hyphotetical males from females were more linked to ontogenic changes and intraspecific variation independent of sex, most notably the neck frill. The geometrics showed no consistent morphological differences between specimens that were regarded as males and females by previous authors, but also a slight support for differences in the rostrum across the sample. Maiorino and team nevertheless, cited that the typical regarded ''Protoceratops'' male, AMNH 6438, pretty much resembles the rostrum morphology of AMNH 6466, a typical regarded female. However, they suggested that authentic differences between sexes could be still present in the postcranial skeleton. Although previously suggested for ''P. hellenikorhinus'', the team argued that the sample used for this species was not sufficient, and given that sexual dimorphism was not recovered in ''P. andrewsi'', it is unlikely that it occurred in ''P. hellenikorhinus''.

In 2016 Hone and colleagues analyzed 37 skulls of ''P. andrewsi'', finding that the neck frill of ''Protoceratops'' (in both length and width) underwent positive allometry during ontongeny, that is, a faster growth/development of this region than the rest of the animal. The jugal bones also showed a trend towards an increase in relative size. These results suggest that they functioned as socio-sexual dominance signals, or, they were mostly used in display. The use of the frill as a displaying structure may be related to other anatomical features of ''Protoceratops'' such as the premaxillary teeth (at least for ''P. andrewsi'') which could have been used in display or intraspecific combat, or the high neural spines of tail. On the other hand, Hone and team argued that if neck frills were instead used for protective purposes, a large frill may have acted as an

In 1989, Walter P. Coombs concluded that

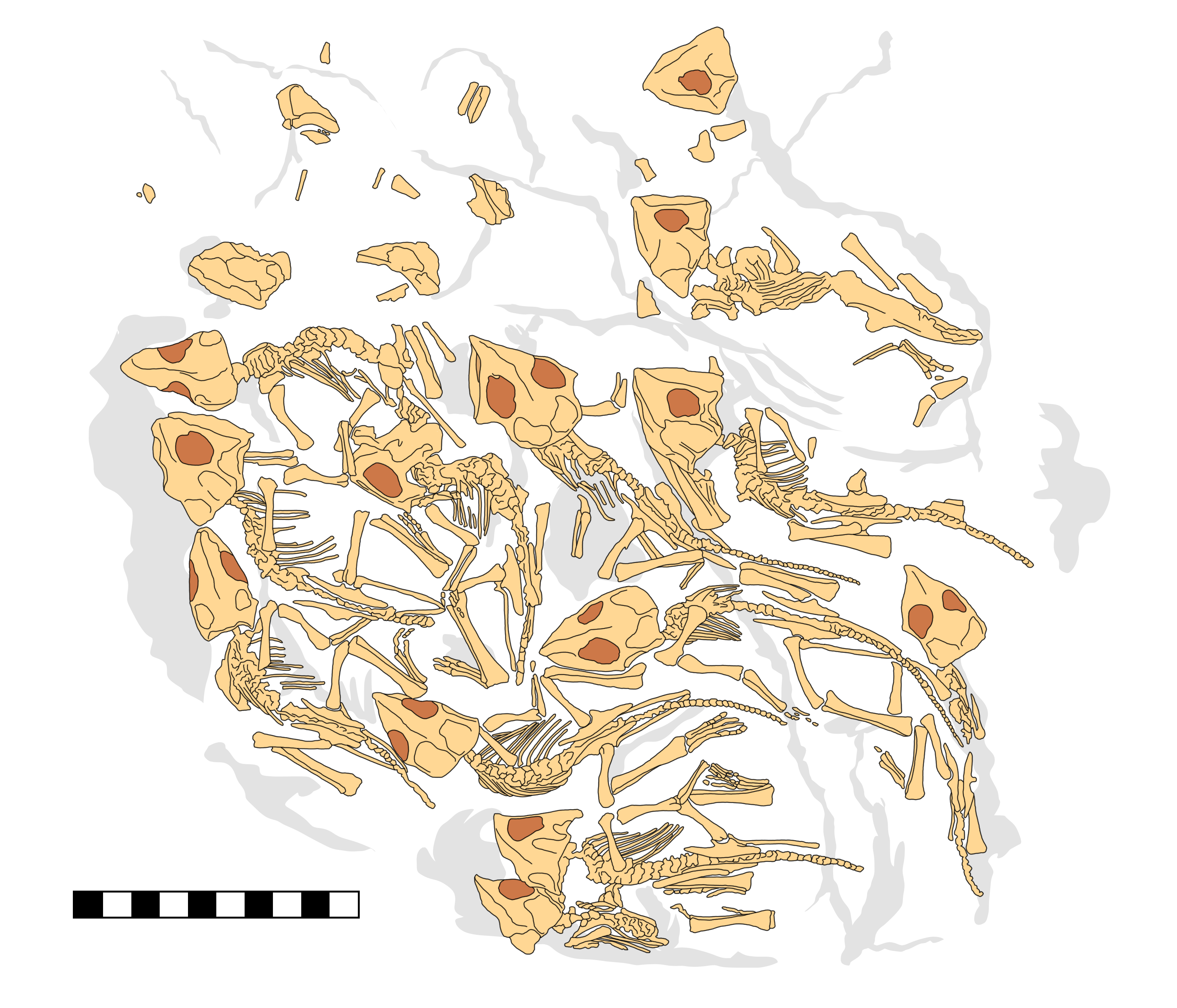

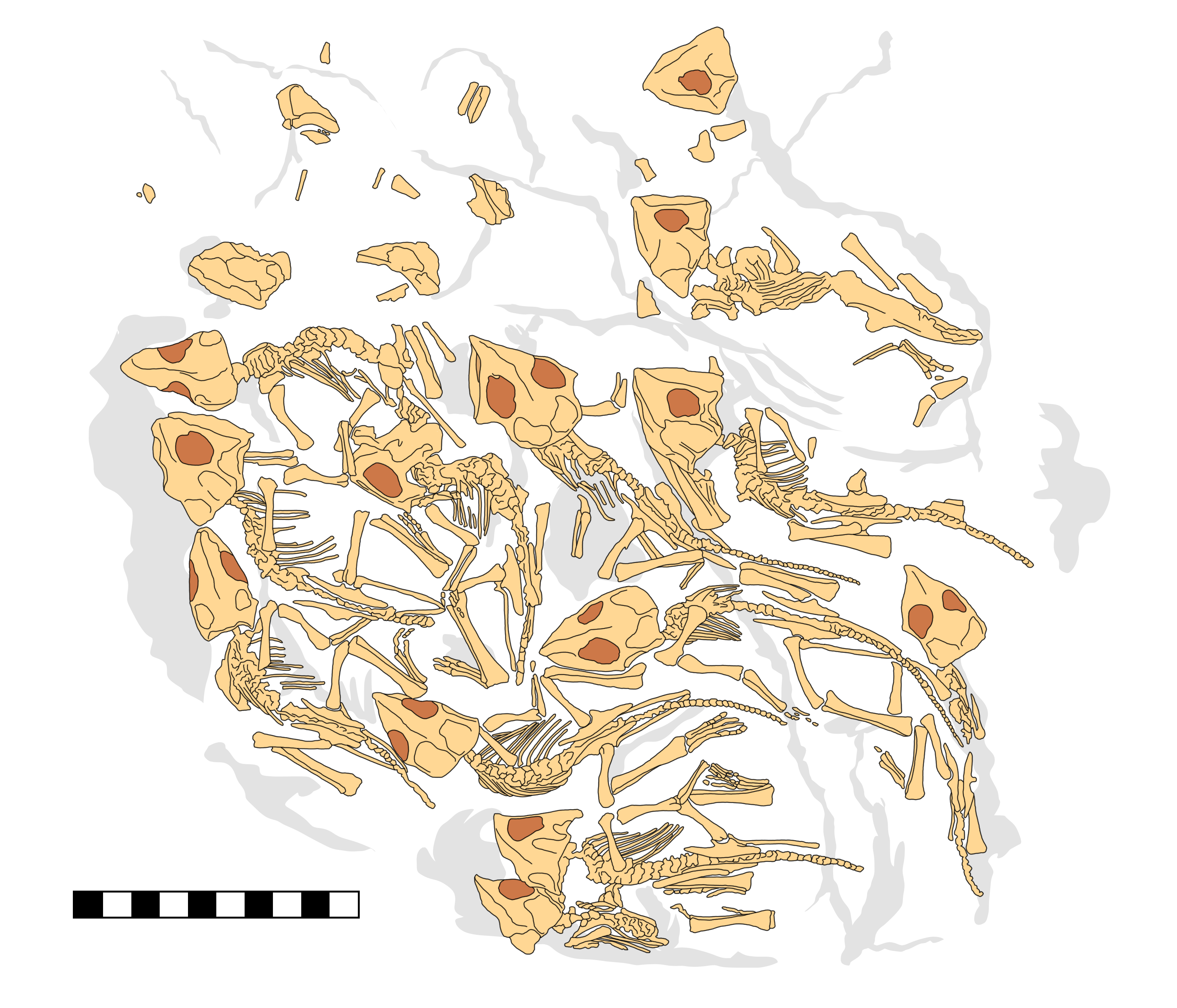

In 1989, Walter P. Coombs concluded that  In 2011 the first authentic nest of ''Protoceratops'' (MPC-D 100/530) from the Tugriken Shireh locality was described by David E. Fastovsky and team. As some individuals are closely appressed along the well-defined margin of the nest, it may have had a circular or semi-circular shape—as previously hypothetized—with a diameter of . Most of the individuals within the nest had nearly the same age, size and growth, suggesting that they belonged to a single nest, rather than an aggregate of individuals. Fastovsky and team also suggested that even though the individuals were young, they were not perinates based on the absence of

In 2011 the first authentic nest of ''Protoceratops'' (MPC-D 100/530) from the Tugriken Shireh locality was described by David E. Fastovsky and team. As some individuals are closely appressed along the well-defined margin of the nest, it may have had a circular or semi-circular shape—as previously hypothetized—with a diameter of . Most of the individuals within the nest had nearly the same age, size and growth, suggesting that they belonged to a single nest, rather than an aggregate of individuals. Fastovsky and team also suggested that even though the individuals were young, they were not perinates based on the absence of

In 2010 Nick Longrich examined the relatively large orbital ratio and

In 2010 Nick Longrich examined the relatively large orbital ratio and

Based on general similarities between the vertebrate fauna and sediments of Bayan Mandahu and the Djadokhta Formation, the

Based on general similarities between the vertebrate fauna and sediments of Bayan Mandahu and the Djadokhta Formation, the

''Protoceratops'' is known from most localities of the

''Protoceratops'' is known from most localities of the

In 1998 during a conference abstract at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, James I. Kirkland and team reported multiple arthropod pupae casts and borings (tunnels) on a largely articulated ''Protoceratops'' specimen from Tugriken Shireh, found in 1997. A notorious amount of pupae were found in clusters and singly along the bone surfaces, mostly in the joint areas, where the trace makers would have feed on dried ligaments, tendons and cartilage. The examined pupae from the specimen are more cylindrical structures with rounded ends. The pupae found in this ''Protoceratops'' individual were reported as measuring as much a long and wide and compare best with pupae attributed to Hunting wasp, solitary wasps. Additionally, the reported borings have a structure that differs from traces made by dermestid beetles. The team indicated that both pupae and boring traces reflect a marked

In 1998 during a conference abstract at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, James I. Kirkland and team reported multiple arthropod pupae casts and borings (tunnels) on a largely articulated ''Protoceratops'' specimen from Tugriken Shireh, found in 1997. A notorious amount of pupae were found in clusters and singly along the bone surfaces, mostly in the joint areas, where the trace makers would have feed on dried ligaments, tendons and cartilage. The examined pupae from the specimen are more cylindrical structures with rounded ends. The pupae found in this ''Protoceratops'' individual were reported as measuring as much a long and wide and compare best with pupae attributed to Hunting wasp, solitary wasps. Additionally, the reported borings have a structure that differs from traces made by dermestid beetles. The team indicated that both pupae and boring traces reflect a marked  In 2010 the paleontologists Yukihide Matsumoto and Mototaka Saneyoshi reported multiple borings and bite traces on joint areas of articulated ''Bagaceratops'' and ''Protoceratops'' specimens from the Tugriken Shireh locality of the

In 2010 the paleontologists Yukihide Matsumoto and Mototaka Saneyoshi reported multiple borings and bite traces on joint areas of articulated ''Bagaceratops'' and ''Protoceratops'' specimens from the Tugriken Shireh locality of the  Hone and colleagues in 2014 indicated that two assemblages of ''Protoceratops'' at Tugriken Shireh (MPC-D 100/526 and 100/534) suggest that individuals died simultaneously, rather than accumulating over time. For instance, the block of four juveniles preserves the individuals with near-identical postures, spatial positions, and all of them have their heads facing upwards, which indicates that they were alive at the time of burial. During burial, the animals were most likely not completely restricted in their movements at all, given that the individuals of MPC-D 100/526 are in relatively normal life positions and have not been disturbed. At least two individuals within this block are preserved with their arms at a level above the legs, suggestive of attempts of trying to move upwards with the purpose of free themselves. The team also noted the presence of borings on the skulls and skeletons of both assemblages, and these may have been produced by insect larvae after the animals died.

In 2016 Meguru Takeuchi and team reported numerous fossilized feeding traces preserved on skeletons of ''Protoceratops'' from the Bayn Dzak, Tugriken Shireh, and Udyn Sayr localities, and also from other dinosaurs. Preserved traces were reported as pits, notches, borings, and tunnels, which they attributed to scavengers. The diameter of the feeding traces preserved on a ''Protoceratops'' skull from Bayn Dzak was bigger than traces reported among other specimens, indicating that the scavengers responsible for these traces were notoriously different from other trace makers preserved on specimens.

Hone and colleagues in 2014 indicated that two assemblages of ''Protoceratops'' at Tugriken Shireh (MPC-D 100/526 and 100/534) suggest that individuals died simultaneously, rather than accumulating over time. For instance, the block of four juveniles preserves the individuals with near-identical postures, spatial positions, and all of them have their heads facing upwards, which indicates that they were alive at the time of burial. During burial, the animals were most likely not completely restricted in their movements at all, given that the individuals of MPC-D 100/526 are in relatively normal life positions and have not been disturbed. At least two individuals within this block are preserved with their arms at a level above the legs, suggestive of attempts of trying to move upwards with the purpose of free themselves. The team also noted the presence of borings on the skulls and skeletons of both assemblages, and these may have been produced by insect larvae after the animals died.

In 2016 Meguru Takeuchi and team reported numerous fossilized feeding traces preserved on skeletons of ''Protoceratops'' from the Bayn Dzak, Tugriken Shireh, and Udyn Sayr localities, and also from other dinosaurs. Preserved traces were reported as pits, notches, borings, and tunnels, which they attributed to scavengers. The diameter of the feeding traces preserved on a ''Protoceratops'' skull from Bayn Dzak was bigger than traces reported among other specimens, indicating that the scavengers responsible for these traces were notoriously different from other trace makers preserved on specimens.

In 1993 the Folklorist and historian of science Adrienne Mayor of Stanford University suggested that the exquisitely preserved fossil skeletons of ''Protoceratops'', '' Psittacosaurus'' and other beaked dinosaurs, found by ancient Scythian nomads who mined gold in the Tian Shan and Altai Mountains of Central Asia, may have been at the root of the image of the mythical creature known as the griffin. Griffins were described as lion-sized quadrupeds with large claws and a raptor-bird-like beak; they laid their eggs in nests on the ground.

In 1993 the Folklorist and historian of science Adrienne Mayor of Stanford University suggested that the exquisitely preserved fossil skeletons of ''Protoceratops'', '' Psittacosaurus'' and other beaked dinosaurs, found by ancient Scythian nomads who mined gold in the Tian Shan and Altai Mountains of Central Asia, may have been at the root of the image of the mythical creature known as the griffin. Griffins were described as lion-sized quadrupeds with large claws and a raptor-bird-like beak; they laid their eggs in nests on the ground.

Dodson in 1996 pointed out Greek writers began describing the griffin around 675 B.C., at the same time the Greeks first made contact with Scythian nomads. Griffins were described as guarding the gold deposits in the arid hills and red sandstone formations of the wilderness. The region of

Dodson in 1996 pointed out Greek writers began describing the griffin around 675 B.C., at the same time the Greeks first made contact with Scythian nomads. Griffins were described as guarding the gold deposits in the arid hills and red sandstone formations of the wilderness. The region of

Footage from the Third Central Asiatic Expedition

at YouTube

3D models of ''Protoceratops andrewsi''

at ArtStation

3D skull model of ''Protoceratops andrewsi''

at Sketchfab

Restored ''Protoceratops andrewsi'' nest

at Facebook

Photograph of current AMNH 6418

at Behance {{Taxonbar, from=Q14506 Coronosaurs Late Cretaceous dinosaurs of Asia Djadochta fauna Fossils of China Fossil taxa described in 1923 Taxa named by Walter W. Granger Taxa named by William King Gregory

genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nom ...

of small protoceratopsid

Protoceratopsidae is a family of basal (primitive) ceratopsians from the Late Cretaceous period. Although ceratopsians have been found all over the world, protoceratopsids are only definitively known from Cretaceous strata in Asia, with most spec ...

dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

s that lived in Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an are ...

during the Late Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the younger of two epochs into which the Cretaceous Period is divided in the geologic time scale. Rock strata from this epoch form the Upper Cretaceous Series. The Cretaceous is named after ''creta'', ...

, around 75 to 71 million years ago. The genus ''Protoceratops'' includes two species: ''P. andrewsi'' and the larger ''P. hellenikorhinus''. The former was described in 1923 with fossils from the Mongolian Djadokhta Formation

The Djadochta Formation (sometimes transcribed and also known as Djadokhta, Djadokata, or Dzhadokhtskaya) is a highly fossiliferous geological formation situated in Central Asia, Gobi Desert, dating from the Late Cretaceous period, about 75 mill ...

, and the latter in 2001 with fossils from the Chinese Bayan Mandahu Formation

The Bayan Mandahu Formation (also known as Wulansuhai Formation or Wuliangsuhai Formation) is a geological unit of "redbeds" located near the village of Bayan Mandahu in Inner Mongolia, China Asia (Gobi Desert) and dates from the late Cretaceous ...

. ''Protoceratops'' was initially believed to be an ancestor of ankylosauria

Ankylosauria is a group of herbivorous dinosaurs of the order Ornithischia. It includes the great majority of dinosaurs with armor in the form of bony osteoderms, similar to turtles. Ankylosaurs were bulky quadrupeds, with short, powerful limbs. ...

ns and larger ceratopsians, such as ''Triceratops

''Triceratops'' ( ; ) is a genus of herbivorous chasmosaurine ceratopsid dinosaur that first appeared during the late Maastrichtian stage of the Late Cretaceous period, about 68 million years ago in what is now North America. It is one ...

'' and relatives, until the discoveries of other protoceratopsids. Populations of ''P. andrewsi'' may have evolved

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variati ...

into ''Bagaceratops

''Bagaceratops'' (meaning "small-horned face") is a genus of small protoceratopsid dinosaurs that lived in Asia during the Late Cretaceous, around 72 to 71 million years ago. ''Bagaceratops'' remains have been reported from the Barun Goyot Form ...

'' through anagenesis

Anagenesis is the gradual evolution of a species that continues to exist as an interbreeding population. This contrasts with cladogenesis, which occurs when there is branching or splitting, leading to two or more lineages and resulting in separate ...

.

''Protoceratops'' were small ceratopsians, about long and in body mass. While adults were largely quadrupedal

Quadrupedalism is a form of locomotion where four limbs are used to bear weight and move around. An animal or machine that usually maintains a four-legged posture and moves using all four limbs is said to be a quadruped (from Latin ''quattuor ...

, juveniles had the capacity to walk around bipedally if necessary. They were characterized by a proportionally large skull

The skull is a bone protective cavity for the brain. The skull is composed of four types of bone i.e., cranial bones, facial bones, ear ossicles and hyoid bone. However two parts are more prominent: the cranium and the mandible. In humans, th ...

, short and stiff neck, and neck frill

A neck frill is the relatively extensive margin seen on the back of the heads of reptiles with either a bony support such as those present on the skulls of dinosaurs of the suborder Marginocephalia or a cartilaginous one as in the frill-necke ...

. The frill was likely used for display or intraspecific combat, as well as protection

Protection is any measure taken to guard a thing against damage caused by outside forces. Protection can be provided to physical objects, including organisms, to systems, and to intangible things like civil and political rights. Although th ...

of the neck and anchoring of jaw muscles. A horn-like structure was present over the nose, which varied from a single structure in ''P. andrewsi'' to a double, paired structure in ''P. hellenikorhinus''. The "horn" and frill were highly variable in shape and size across individuals of the same species, but there is no evidence of sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where the sexes of the same animal and/or plant species exhibit different morphological characteristics, particularly characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most an ...

. They had a prominent parrot

Parrots, also known as psittacines (), are birds of the roughly 398 species in 92 genera comprising the order Psittaciformes (), found mostly in tropical and subtropical regions. The order is subdivided into three superfamilies: the Psittacoide ...

-like beak at the tip of the jaws. ''P. andrewsi'' had a pair of cylindrical, blunt teeth

A tooth ( : teeth) is a hard, calcified structure found in the jaws (or mouths) of many vertebrates and used to break down food. Some animals, particularly carnivores and omnivores, also use teeth to help with capturing or wounding prey, ...

near the tip of the upper jaw. The forelimbs had five fingers

A finger is a limb of the body and a type of digit, an organ of manipulation and sensation found in the hands of most of the Tetrapods, so also with humans and other primates. Most land vertebrates have five fingers (Pentadactyly). Chambers 1 ...

of which only the first three bore wide and flat ungual

An ungual (from Latin ''unguis'', i.e. ''nail'') is a highly modified distal toe bone which ends in a hoof, claw, or nail. Elephants and ungulates have ungual phalanges, as did the sauropod

Sauropoda (), whose members are known as sauropods (; ...

s. The feet were wide and had four toes with flattened, shovel-like unguals, which would have been useful for digging

Digging, also referred to as excavation, is the process of using some implement such as claws, hands, manual tools or heavy equipment, to remove material from a solid surface, usually soil, sand or rock on the surface of Earth. Digging is act ...

through the sand. The hindlimbs were longer than the forelimbs. The tail was long and had an enigmatic sail

A sail is a tensile structure—which is made from fabric or other membrane materials—that uses wind power to propel sailing craft, including sailing ships, sailboats, windsurfers, ice boats, and even sail-powered land vehicles. Sails ma ...

-like structure, which may have been used for display, swimming

Swimming is the self-propulsion of a person through water, or other liquid, usually for recreation, sport, exercise, or survival. Locomotion is achieved through coordinated movement of the limbs and the body to achieve hydrodynamic thrust that r ...

, or metabolic

Metabolism (, from el, μεταβολή ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cell ...

reasons.

''Protoceratops'', like many other ceratopsians, were herbivore

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically adapted to eating plant material, for example foliage or marine algae, for the main component of its diet. As a result of their plant diet, herbivorous animals typically have mouthpar ...

s equipped with prominent jaws and teeth suited for chopping foliage

A leaf ( : leaves) is any of the principal appendages of a vascular plant stem, usually borne laterally aboveground and specialized for photosynthesis. Leaves are collectively called foliage, as in "autumn foliage", while the leaves, ...

and other plant

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae excl ...

material. They are thought to have lived in highly sociable

The sociable or buddy bike or side by side bicycle is a bicycle that supports two riders who sit next to one another, in contrast to a tandem bicycle, where the riders sit fore and aft. The name "sociable" alludes to the relative ease with which ...

groups of mixed ages. They appear to have cared for their young. They laid soft-shelled eggs

Humans and human ancestors have scavenged and eaten animal eggs for millions of years. Humans in Southeast Asia had domesticated chickens and harvested their eggs for food by 1,500 BCE. The most widely consumed eggs are those of fowl, especial ...

, a rare occurrence in dinosaurs. During maturation, the skull and neck frill underwent rapid growth. ''Protoceratops'' were hunted by ''Velociraptor

''Velociraptor'' (; ) is a genus of small dromaeosaurid dinosaur that lived in Asia during the Late Cretaceous epoch, about 75 million to 71 million years ago. Two species are currently recognized, although others have been assigned in th ...

'', and one particularly famous specimen (the Fighting Dinosaurs

The Fighting Dinosaurs is a fossil specimen which was found in the Late Cretaceous Djadokhta Formation of Mongolia. It preserves a ''Protoceratops andrewsi'' and ''Velociraptor mongoliensis'' trapped in combat and provides direct evidence of pr ...

) preserves a pair of them locked in combat. ''Protoceratops'' used to be characterized as nocturnal

Nocturnality is an animal behavior characterized by being active during the night and sleeping during the day. The common adjective is "nocturnal", versus diurnal meaning the opposite.

Nocturnal creatures generally have highly developed sens ...

because of the large sclerotic ring

Sclerotic rings are rings of bone found in the eyes of many animals in several groups of vertebrates, except for mammals and crocodilians. They can be made up of single bones or multiple segments and take their name from the sclera. They are bel ...

around the eye, but they are now thought to have been cathemeral

Cathemerality, sometimes called metaturnality, is an organismal activity pattern of irregular intervals during the day or night in which food is acquired, socializing with other organisms occurs, and any other activities necessary for livelihood ar ...

(active at dawn and dusk).

History of discovery

In 1900

In 1900 Henry Fairfield Osborn

Henry Fairfield Osborn, Sr. (August 8, 1857 – November 6, 1935) was an American paleontologist, geologist and eugenics advocate. He was the president of the American Museum of Natural History for 25 years and a cofounder of the American Euge ...

suggested that Central Asia may have been the center of origin of most animal species, including humans, which caught the attention of explorer

Exploration refers to the historical practice of discovering remote lands. It is studied by geographers and historians.

Two major eras of exploration occurred in human history: one of convergence, and one of divergence. The first, covering most ...

and zoologist

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, and d ...

Roy Chapman Andrews

Roy Chapman Andrews (January 26, 1884 – March 11, 1960) was an American explorer, adventurer and naturalist who became the director of the American Museum of Natural History. He led a series of expeditions through the politically disturbed ...

. This idea later gave rise to the First (1916 to 1917), Second (1919) and Third (1921 to 1930) Central Asiatic Expeditions to China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

and Mongolia

Mongolia; Mongolian script: , , ; lit. "Mongol Nation" or "State of Mongolia" () is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south. It covers an area of , with a population of just 3.3 million ...

, organized by the American Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History (abbreviated as AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. In Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 26 int ...

under the direction of Osborn and field leadership of Andrews. The team of the third expedition arrived in Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), Chinese postal romanization, alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the Capital city, capital of the China, People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's Li ...

in 1921 for the final preparations and started working in the field in 1922. During late 1922 the expedition explored the famous Flaming Cliffs

The Flaming Cliffs site (also known as Bayanzag ( zh, 巴彥扎格), Bain-Dzak or Bayn Dzak) ( mn, Баянзаг ''rich in saxaul''), with the alternative Mongolian name of mn, Улаан Эрэг (''red cliffs''), is a region of the Gobi Deser ...

of the Shabarakh Usu region of the Djadokhta Formation

The Djadochta Formation (sometimes transcribed and also known as Djadokhta, Djadokata, or Dzhadokhtskaya) is a highly fossiliferous geological formation situated in Central Asia, Gobi Desert, dating from the Late Cretaceous period, about 75 mill ...

, Gobi Desert

The Gobi Desert ( Chinese: 戈壁 (沙漠), Mongolian: Говь (ᠭᠣᠪᠢ)) () is a large desert or brushland region in East Asia, and is the sixth largest desert in the world.

Geography

The Gobi measures from southwest to northeast a ...

, now known as the Bayn Dzak region. On September 2, the photographer James B. Shackelford discovered a partial juvenile skull—which would become the holotype

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of seve ...

specimen (AMNH 6251) of ''Protoceratops''—in reddish sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicat ...

s. It was subsequently analyzed by the paleontologist Walter W. Granger

Walter Willis Granger (November 7, 1872 – September 6, 1941) was an American vertebrate paleontologist who participated in important fossil explorations in the United States, Egypt, China and Mongolia.

Early life and career

Born in Mid ...

who identified it as reptilia

Reptiles, as most commonly defined are the animals in the class Reptilia ( ), a paraphyletic grouping comprising all sauropsids except birds. Living reptiles comprise turtles, crocodilians, squamates (lizards and snakes) and rhynchocephalians ( ...

n. On September 21, the expedition returned to Beijing, and even though it was set up to look for remains of human ancestors, the team collected numerous dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

s and thus provided insights into the rich fossil record of Asia. Back in Beijing, the skull Shackelford had found was sent back to the American Museum of Natural History for further study, after which Osborn reached out to Andrews and team via cable, notifying them about the importance of the specimen.

In 1923 the expedition prospected the Flaming Cliffs again, this time discovering even more specimens of ''Protoceratops'' and also the first remains of ''Oviraptor

''Oviraptor'' (; ) is a genus of oviraptorid dinosaur that lived in Asia during the Late Cretaceous period. The first remains were collected from the Djadokhta Formation of Mongolia in 1923 during a paleontological expedition led by Roy Chapma ...

'', ''Saurornithoides

''Saurornithoides'' ( ) is a genus of troodontid maniraptoran dinosaur, which lived during the Late Cretaceous period. These creatures were predators, which could run fast on their hind legs and had excellent sight and hearing. The name is deri ...

'' and ''Velociraptor

''Velociraptor'' (; ) is a genus of small dromaeosaurid dinosaur that lived in Asia during the Late Cretaceous epoch, about 75 million to 71 million years ago. Two species are currently recognized, although others have been assigned in th ...

''. Most notably, the team discovered the first fossilized dinosaur eggs near the holotype of ''Oviraptor'' and given how abundant ''Protoceratops'' was, the nest was attributed to this taxon

In biology, a taxon ( back-formation from '' taxonomy''; plural taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular n ...

. This would later result in the interpretation of ''Oviraptor'' as an egg-thief. In the same year, Granger and William K. Gregory formally described the new genus and species ''Protoceratops andrewsi'' based on the holotype skull. The specific name, ''andrewsi'', is in honor of Andrews for his prominent leadership during the expeditions. They identified ''Protoceratops'' as an ornithischia

Ornithischia () is an extinct order of mainly herbivorous dinosaurs characterized by a pelvic structure superficially similar to that of birds. The name ''Ornithischia'', or "bird-hipped", reflects this similarity and is derived from the Greek ...

n dinosaur closely related to ceratopsians representing a possible common ancestor between ankylosaur

Ankylosauria is a group of herbivorous dinosaurs of the order Ornithischia. It includes the great majority of dinosaurs with armor in the form of bony osteoderms, similar to turtles. Ankylosaurs were bulky quadrupeds, with short, powerful limbs. ...

s and ceratopsia

Ceratopsia or Ceratopia ( or ; Greek: "horned faces") is a group of herbivorous, beaked dinosaurs that thrived in what are now North America, Europe, and Asia, during the Cretaceous Period, although ancestral forms lived earlier, in the Jurass ...

ns. Since ''Protoceratops'' was more primitive than any other known ceratopsian at that time, Granger and Gregory coined the new family Protoceratopsidae, mostly characterized by the lack of horns. The co-authors also agreed with Osborn in that Asia, if more explored, could solve many major evolutionary gaps in the fossil record. Although not stated in the original description, the generic name, ''Protoceratops'', is intended to mean "first horned face" as it was believed that ''Protoceratops'' represented an early ancestor of ceratopsid

Ceratopsidae (sometimes spelled Ceratopidae) is a family of ceratopsian dinosaurs including ''Triceratops'', ''Centrosaurus'', and ''Styracosaurus''. All known species were quadrupedal herbivores from the Upper Cretaceous. All but one species are ...

s. Other researchers immediately noted the importance of the ''Protoceratops'' finds, and the genus was hailed as the "long-sought ancestor of ''Triceratops''". Most fossils were in an excellent state of preservation with even sclerotic ring

Sclerotic rings are rings of bone found in the eyes of many animals in several groups of vertebrates, except for mammals and crocodilians. They can be made up of single bones or multiple segments and take their name from the sclera. They are bel ...

s (delicate ocular bones) preserved in some specimens, quickly making ''Protoceratops'' one of the best-known dinosaurs from Asia.

After spending much of 1924 making plans for the next fieldwork seasons, in 1925 Andrews and team explored the Flaming Cliffs yet again. During this year more eggs and nests were collected, alongside well-preserved and complete specimens of ''Protoceratops''. By this time, ''Protoceratops'' had become one of the most abundant dinosaurs of the region with more than 100 specimens known, including skulls and skeletons of multiple individuals at different growth stages. Though more remains of ''Protoceratops'' were collected in later years of the expeditions, they were most abundant in the 1922 to 1925 seasons. Gregory and

After spending much of 1924 making plans for the next fieldwork seasons, in 1925 Andrews and team explored the Flaming Cliffs yet again. During this year more eggs and nests were collected, alongside well-preserved and complete specimens of ''Protoceratops''. By this time, ''Protoceratops'' had become one of the most abundant dinosaurs of the region with more than 100 specimens known, including skulls and skeletons of multiple individuals at different growth stages. Though more remains of ''Protoceratops'' were collected in later years of the expeditions, they were most abundant in the 1922 to 1925 seasons. Gregory and Charles C. Mook

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English language, English and French language, French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic, Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*k ...

published another description of ''Protoceratops'' in 1925, discussing its anatomy and relationships. Thanks to the large collection of skulls found in the expeditions, they concluded that ''Protoceratops'' represented a ceratopsian more primitive than ceratopsids and not an ankylosaur-ceratopsian ancestor. In 1940, Barnum Brown

Barnum Brown (February 12, 1873 – February 5, 1963), commonly referred to as Mr. Bones, was an American paleontologist. Named after the circus showman P. T. Barnum, he discovered the first documented remains of '' Tyrannosaurus'' during a career ...

and Erich Maren Schlaikjer

Erich Maren Schlaikjer (; November 22, 1905 in Newtown, Ohio – November 5, 1972) was an American geologist and dinosaur hunter. Assisting Barnum Brown, he co-described ''Pachycephalosaurus'' and what is now ''Montanoceratops''. Other discoveries ...

described the anatomy of ''P. andrewsi'' in extensive detail using newly prepared specimens from the Asiatic expeditions.

In 1963, the Mongolian paleontologist Demberelyin Dashzeveg reported the discovery of a new fossiliferous locality of the Djadokhta Formation: Tugriken Shireh. Like the neighbouring Bayn Dzak, this new locality contained an abundance of ''Protoceratops'' fossils. During the 1960s

File:1960s montage.png, Clockwise from top left: U.S. soldiers during the Vietnam War; the Beatles led the British Invasion of the U.S. music market; a half-a-million people participate in the 1969 Woodstock Festival; Neil Armstrong and Buzz ...

to 1970s

File:1970s decade montage.jpg, Clockwise from top left: U.S. President Richard Nixon doing the V for Victory sign after his resignation from office following the Watergate scandal in 1974; The United States was still involved in the Vietnam War ...

, Polish-Mongolian and Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

n-Mongolian paleontological expeditions collected new, partial to complete specimens of ''Protoceratops'' at this locality, making this dinosaur species a common occurrence in Tugriken Shireh. Since its discovery, the Tugriken Shireh locality has yielded some of the most significant specimens of ''Protoceratops'', such as the Fighting Dinosaurs

The Fighting Dinosaurs is a fossil specimen which was found in the Late Cretaceous Djadokhta Formation of Mongolia. It preserves a ''Protoceratops andrewsi'' and ''Velociraptor mongoliensis'' trapped in combat and provides direct evidence of pr ...

, ''in situ

''In situ'' (; often not italicized in English) is a Latin phrase that translates literally to "on site" or "in position." It can mean "locally", "on site", "on the premises", or "in place" to describe where an event takes place and is used in ...

'' individuals—a preservation condition also known as "standing" individuals or specimens in some cases—, authentic nests, and small herd-like groups. Specimens from this locality are usually found in articulation, suggesting possible mass mortality events.

Stephan N. F. Spiekman and colleagues reported a partial ''P. andrewsi'' skull (RGM 818207) in the collections of the Naturalis Biodiversity Center

Naturalis Biodiversity Center ( nl, Nederlands Centrum voor Biodiversiteit Naturalis) is a national museum of natural history and a research center on biodiversity in Leiden, Netherlands. It was named the European Museum of the Year 2021. ...

, Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

in 2015. Since ''Protoceratops'' fossils are only found in the Gobi Desert of Mongolia and this specimen was likely discovered during the Central Asiatic Expeditions, the team concluded that this skull was probably acquired by the Delft University

Delft University of Technology ( nl, Technische Universiteit Delft), also known as TU Delft, is the oldest and largest Dutch public technical university, located in Delft, Netherlands. As of 2022 it is ranked by QS World University Rankings among ...

between 1940 and 1972 as part of a collection transfer.

Species and synonyms

Protoceratopsid remains were recovered in the 1970s from the Khulsan locality of the

Protoceratopsid remains were recovered in the 1970s from the Khulsan locality of the Barun Goyot Formation

The Barun Goyot Formation (also known as Baruungoyot Formation or West Goyot Formation) is a geological formation dating to the Late Cretaceous Period. It is located within and is widely represented in the Gobi Desert Basin, in the Ömnögovi Pr ...

, Mongolia, during the work of several Polish-Mongolian paleontological expeditions. In 1975, Polish paleontologists Teresa Maryańska

Teresa Maryańska (1937 – 3 October 2019) was a Polish paleontologist who specialized in Mongolian dinosaurs, particularly pachycephalosaurians and ankylosaurians. Peter Dodson (1998 p. 9) states that in 1974 Maryanska together with Hals ...

and Halszka Osmólska described a second species of ''Protoceratops'' which they named ''P. kozlowskii''. This new species was based on the Khulsan material, mostly consisting of juvenile skull specimens. The specific name, ''kozlowskii'', is in tribute to the Polish paleontologist Roman Kozłowski. They also named the new genus and species of protoceratopsid '' Bagaceratops rozhdestvenskyi'', known from specimens of the nearby Hermiin Tsav locality. In 1990 the Russian paleontologist Sergei Mikhailovich Kurzanov referred additional material from Hermiin Tsav to ''P. kozlowskii''. However, he noted that there were enough differences between ''P. andrewsi'' and ''P. kozlowskii'', and erected the new genus and combination ''Breviceratops kozlowskii

''Breviceratops'' (meaning "short horned face") is a genus of protoceratopsid dinosaur that lived during the Late Cretaceous in what is now the Barun Goyot Formation, Mongolia.

Discovery and naming

The first fossils were discovered during the 1 ...

''. Though ''Breviceratops'' has been regarded as a synonym

A synonym is a word, morpheme, or phrase that means exactly or nearly the same as another word, morpheme, or phrase in a given language. For example, in the English language, the words ''begin'', ''start'', ''commence'', and ''initiate'' are al ...

and juvenile stage of ''Bagaceratops'', Łukasz Czepiński in 2019 concluded that the former has enough anatomical differences to be considered as a separate taxon

In biology, a taxon ( back-formation from '' taxonomy''; plural taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular n ...

.

In 2001 Oliver Lambert with colleagues named a new and distinct species of ''Protoceratops'', ''P. hellenikorhinus''. The first known remains of ''P. hellenikorhinus'' were collected from the Bayan Mandahu locality of the Bayan Mandahu Formation

The Bayan Mandahu Formation (also known as Wulansuhai Formation or Wuliangsuhai Formation) is a geological unit of "redbeds" located near the village of Bayan Mandahu in Inner Mongolia, China Asia (Gobi Desert) and dates from the late Cretaceous ...

, Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia, officially the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China. Its border includes most of the length of China's border with the country of Mongolia. Inner Mongolia also accounts for a ...

, in 1995 and 1996 during Sino-Belgian

Belgian may refer to:

* Something of, or related to, Belgium

* Belgians, people from Belgium or of Belgian descent

* Languages of Belgium, languages spoken in Belgium, such as Dutch, French, and German

*Ancient Belgian language, an extinct languag ...

paleontological expeditions. The holotype (IMM 95BM1/1) and paratype

In zoology and botany, a paratype is a specimen of an organism that helps define what the scientific name of a species and other taxon actually represents, but it is not the holotype (and in botany is also neither an isotype nor a syntype). O ...

(IMM 96BM1/4) specimens consist of large skulls lacking body remains. The holotype skull was found facing upwards, a pose that has been reported in ''Protoceratops'' specimens from Tugriken Shireh. The specific name, ''hellenikorhinus'', is derived from Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

hellenikos (meaning Greek) and rhis (meaning nose) in reference to its broad and angular snout, which is reminiscent of the straight profiles of Greek sculptures. In 2017 abundant protoceratopsid material was reported from Alxa near Bayan Mandahu, and it may be referable to ''P. hellenikorhinus''.

Viktor Tereshchenko

The name Victor or Viktor may refer to:

* Victor (name), including a list of people with the given name, mononym, or surname

Arts and entertainment

Film

* ''Victor'' (1951 film), a French drama film

* ''Victor'' (1993 film), a French shor ...

and Vladimir R. Alifanov

Vladimir may refer to:

Names

* Vladimir (name) for the Bulgarian, Croatian, Czech, Macedonian, Romanian, Russian, Serbian, Slovak and Slovenian spellings of a Slavic name

* Uladzimir for the Belarusian version of the name

* Volodymyr for the Ukr ...

in 2003 named a new protoceratopsid dinosaur from the Bayn Dzak locality, ''Bainoceratops efremovi ''. This genus was based on a few dorsal (back) vertebrae that were stated to differ from those of ''Protoceratops''. In 2006 North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and th ...

n paleontologists Peter Makovicky and Mark A. Norell

Mark Allen Norell (born July 26, 1957) is an American paleontologist, acknowledged as one of the most important living Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution, vertebrate paleontologists. He is currently the chairman of paleontology and a research ...

suggested that ''Bainoceratops'' may be synonymous with ''Protoceratops'' as most of the traits used to separate the former from the latter have been reported from other ceratopsians including ''Protoceratops'' itself, and they are more likely to fall within the wide intraspecific variation range of the concurring ''P. andrewsi''. The authors Brenda J. Chinnery and Jhon R. Horner Jhon is a spelling variation of the English given name ''Juan, John''. Its usage is popular throughout English speaking regions of South America, but is mainly concentrated in Colombia, where the name is listed as one of the most common names in the ...

in 2007 during their description of ''Cerasinops

''Cerasinops'' (meaning 'cherry face') was a small ceratopsian dinosaur. It lived during the Campanian of the late Cretaceous Period.

'' stated that ''Bainoceratops'', along with other dubious genera, was determined to be either a variant or immature specimen of other genera. Based on this reasoning, they excluded ''Bainoceratops'' from their phylogenetic analysis.

Eggs and nests

As part of the Third Central Asiatic Expedition of 1923, Andrews and team discovered the holotype specimen of ''

As part of the Third Central Asiatic Expedition of 1923, Andrews and team discovered the holotype specimen of ''Oviraptor

''Oviraptor'' (; ) is a genus of oviraptorid dinosaur that lived in Asia during the Late Cretaceous period. The first remains were collected from the Djadokhta Formation of Mongolia in 1923 during a paleontological expedition led by Roy Chapma ...

'' in association with some of the first known fossilized dinosaur eggs (nest AMNH 6508), in the Djadokhta Formation. Each egg was elongated and hard-shelled, and due to the proximity and high abundance of ''Protoceratops'' in the formation

Formation may refer to:

Linguistics

* Back-formation, the process of creating a new lexeme by removing or affixes

* Word formation, the creation of a new word by adding affixes

Mathematics and science

* Cave formation or speleothem, a secondar ...

, these eggs were believed at the time to belong to this dinosaur. This resulted in the interpretation of the contemporary ''Oviraptor'' as an egg predatory animal, an interpretation also reflected in its generic name. In 1975

It was also declared the ''International Women's Year'' by the United Nations and the European Architectural Heritage Year by the Council of Europe.

Events

January

* January 1 - Watergate scandal (United States): John N. Mitchell, H. R. ...

, the Chinese paleontologist Zhao Zikui Zhao may refer to:

* Zhao (surname) (赵), a Chinese surname

** commonly spelled Chao in Taiwan or up until the early 20th century in other regions

** Chiu, from the Cantonese pronunciation

** Cho (Korean surname), represent the Hanja 趙 (Chinese ...

named the new oogenera ''Elongatoolithus

''Elongatoolithus'' is an oogenus of dinosaur eggs found in the Late Cretaceous formations of China and Mongolia. Like other elongatoolithids, they were laid by small theropods (probably oviraptorosaurs), and were cared for and incubated by thei ...

'' and ''Macroolithus

''Macroolithus'' is an oogenus (fossil-egg genus) of dinosaur egg belonging to the oofamily Elongatoolithidae. The type oospecies, ''M. rugustus'', was originally described under the now-defunct oogenus name ''Oolithes''. Three other oospecies ...

'', including them in a new oofamily

Egg fossils are the fossilized remains of eggs laid by ancient animals. As evidence of the physiological processes of an animal, egg fossils are considered a type of trace fossil. Under rare circumstances a fossil egg may preserve the remains of ...

: the Elongatoolithidae

Elongatoolithidae is an oofamily of fossil eggs, representing the eggs of oviraptorosaurs (with the exception of the Bird, avian ''Ornitholithus''). They are known for their highly elongated shape. Elongatoolithids have been found in Europe, Asia, ...

. As the name implies, they represent elongated dinosaur eggs, including some of referred ones to ''Protoceratops''.

In 1994 the Russian paleontologist Konstantin E. Mikhailov named the new oogenus '' Protoceratopsidovum'' from the Barun Goyot and Djadokhta formations, with the type species ''P. sincerum'' and additional ''P. fluxuosum'' and ''P. minimum''. This ootaxon

Egg fossils are the fossilized remains of eggs laid by ancient animals. As evidence of the physiological processes of an animal, egg fossils are considered a type of trace fossil. Under rare circumstances a fossil egg may preserve the remains of ...

was firmly stated as belonging to protoceratopsid dinosaurs since they were the predominant dinosaurs where the eggs were found and some skeletons of ''Protoceratops'' were found in close proximity to ''Protoceratopsidovum'' eggs. More specifically, Mikhailov stated that ''P. sincerum'' and ''P. minimum'' were laid by ''Protoceratops'', and ''P. fluxuosum'' by ''Breviceratops''.

theropod

Theropoda (; ), whose members are known as theropods, is a dinosaur clade that is characterized by hollow bones and three toes and claws on each limb. Theropods are generally classed as a group of saurischian dinosaurs. They were ancestrally c ...

embryo

An embryo is an initial stage of development of a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male spe ...

inside an egg (MPC-D 100/971) from the Djadokhta Formation. They identified this embryo as an oviraptorid

Oviraptoridae is a group of bird-like, herbivorous and omnivorous maniraptoran dinosaurs. Oviraptorids are characterized by their toothless, parrot-like beaks and, in some cases, elaborate crests. They were generally small, measuring between on ...

dinosaur and the eggshell, upon close examination, turned out be that of elongatoolithid eggs and thereby the oofamily Elongatoolithidae was concluded to represent the eggs of oviraptorids. This find proved that the nest AMNH 6508 belonged to ''Oviraptor'' and rather than an egg-thief, the holotype was actually a mature individual that perished brooding the eggs. Moreover, phylogenetic analyses

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek φυλή/ φῦλον [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:γενετικός, γενετικός [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups o ...

published in 2008 by Darla K. Zelenitsky and François Therrien have shown that ''Protoceratopsidovum'' represents the eggs of a maniraptoran more derived than oviraptorids and not ''Protoceratops''. The description of the eggshell of ''Protoceratopsidovum'' has further confirmed that they in fact belong to a maniraptoran, possibly deinonychosaur taxon.

Nevertheless, in 2011 an authentic nest of ''Protoceratops'' was reported and described by David E. Fastovsky and colleagues. The nest (MPC-D 100/530) containing 15 articulated juveniles was collected from the Tugriken Shireh locality of the Djadokhta Formation during the work of Mongolian-Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

ese paleontological expeditions. Gregory M. Erickson and team in 2017 reported an embryo-bearing egg clutch (MPC-D 100/1021) of ''Protoceratops'' from the also fossiliferous Ukhaa Tolgod locality, discovered during paleontological expeditions of the American Museum of Natural History and Mongolian Academy of Sciences

The Mongolian Academy of Sciences (, ''Mongol ulsyn Shinjlekh ukhaany Akademi'') is Mongolia's first centre of modern sciences. It came into being in 1921 when the government of newly

independent Mongolia issued a resolution declaring the establ ...

. This clutch comprises at least 12 eggs and embryos with only 6 embryos preserving nearly complete skeletons. Norell with colleagues in 2020 examined fossilized remains around the eggs of this clutch which indicate a soft-shelled composition.

Fighting Dinosaurs

The

The Fighting Dinosaurs

The Fighting Dinosaurs is a fossil specimen which was found in the Late Cretaceous Djadokhta Formation of Mongolia. It preserves a ''Protoceratops andrewsi'' and ''Velociraptor mongoliensis'' trapped in combat and provides direct evidence of pr ...

specimen preserves a ''Protoceratops'' (MPC-D 100/512) and ''Velociraptor'' (MPC-D 100/25) fossilized in combat and provides an important window regarding direct evidence of predator-prey behavior in non-avian dinosaurs. In the 1960s and early 1970s, many Polish-Mongolian paleontological expeditions were conducted to the Gobi Desert with the objective of fossil findings. In 1971, the expedition explored several localities of the Djadokhta and Nemegt formations. On August 3 several fossils of ''Protoceratops'' and ''Velociraptor'' were found including a block containing two of them at the Tugriken Shire locality (Djadokhta Formation) during fieldworks of the expedition. The individuals of this block were identified as a ''P. andrewsi'' and ''V. mongoliensis''. Although it was not fully understood the conditions surrounding their burial, it was clear that they died simultaneously in struggle.

The specimen shortly became notorious and was nicknamed the Fighting Dinosaurs. It has been examined and studied by numerous researchers and paleontologists, debating on how the animals got buried and preserved altogether. Though a drowning scenario has been proposed by Barsbold, such hypothesis is considered unlikely given the arid paleoenvironments or settings of the Djadokhta Formation. It is generally accepted that they were buried alive by either a collapsed dune

A dune is a landform composed of wind- or water-driven sand. It typically takes the form of a mound, ridge, or hill. An area with dunes is called a dune system or a dune complex. A large dune complex is called a dune field, while broad, f ...

or sandstorm.

Skin impressions and footprints

During the Third Central Asiatic Expedition in 1923, a nearly complete ''Protoceratops'' skeleton (specimen AMNH 6418) was collected at the Flaming Cliffs. Unlike other specimens, it was discovered in a rolled-up position with itsskull

The skull is a bone protective cavity for the brain. The skull is composed of four types of bone i.e., cranial bones, facial bones, ear ossicles and hyoid bone. However two parts are more prominent: the cranium and the mandible. In humans, th ...

preserving a thin, hard, and wrinkled layer of matrix

Matrix most commonly refers to:

* ''The Matrix'' (franchise), an American media franchise

** '' The Matrix'', a 1999 science-fiction action film

** "The Matrix", a fictional setting, a virtual reality environment, within ''The Matrix'' (franchi ...

(surrounding sediments

Sediment is a naturally occurring material that is broken down by processes of weathering and erosion, and is subsequently transported by the action of wind, water, or ice or by the force of gravity acting on the particles. For example, sa ...

). This specimen was later described in 1940 by Brown and Schlaikjer, who discussed the nature of the matrix portion. They stated that this layer had a very skin

Skin is the layer of usually soft, flexible outer tissue covering the body of a vertebrate animal, with three main functions: protection, regulation, and sensation.

Other animal coverings, such as the arthropod exoskeleton, have different ...

-like texture and covered mostly the left side of the skull from the snout

A snout is the protruding portion of an animal's face, consisting of its nose, mouth, and jaw. In many animals, the structure is called a muzzle, rostrum, or proboscis. The wet furless surface around the nostrils of the nose of many mammals is ...

to the neck frill

A neck frill is the relatively extensive margin seen on the back of the heads of reptiles with either a bony support such as those present on the skulls of dinosaurs of the suborder Marginocephalia or a cartilaginous one as in the frill-necke ...

. Brown and Schlaikjer discarded the idea of possible skin impressions as this skin-like layer was likely a product of the decay and burial of the individual, making the sediments become highly attached to the skull. The potential importance of these remains were not recognized and given attention, and by 2020 the specimen has already been completely prepared losing all traces of this skin-like layer. Some elements were damaged in the process such as the rostrum

Rostrum may refer to:

* Any kind of a platform for a speaker:

**dais

**pulpit

* Rostrum (anatomy), a beak, or anatomical structure resembling a beak, as in the mouthparts of many sucking insects

* Rostrum (ship), a form of bow on naval ships

* Ros ...

.

Also from the context of the Polish-Mongolian paleontological expeditions, in 1965 an articulated subadult ''Protoceratops'' skeleton (specimen ZPAL Mg D-II/3) was collected from the Bayn Dzak locality of the Djadokhta Formation. In the 2000s during the preparation of the specimen, a fossilized cast of a four-toed digitigrade

In terrestrial vertebrates, digitigrade () locomotion is walking or running on the toes (from the Latin ''digitus'', 'finger', and ''gradior'', 'walk'). A digitigrade animal is one that stands or walks with its toes (metatarsals) touching the groun ...

footprint was found below the pelvic girdle. This footprint was described in 2012 by Grzegorz Niedźwiedzki and colleagues who considered it to represent one of the first reported finds of a dinosaur footprint in association with an articulated skeleton, and also the first one reported for ''Protoceratops''. The limb elements of the skeleton of ZPAL Mg D-II/3 were described in 2019 by paleontologists Justyna Słowiak, Victor S. Tereshchenko and Łucja Fostowicz-Frelik. Tereshchenko in 2021 fully described the axial skeleton of this specimen.

Description

''Protoceratops'' was a relatively small-sized

''Protoceratops'' was a relatively small-sized ceratopsia

Ceratopsia or Ceratopia ( or ; Greek: "horned faces") is a group of herbivorous, beaked dinosaurs that thrived in what are now North America, Europe, and Asia, during the Cretaceous Period, although ancestral forms lived earlier, in the Jurass ...

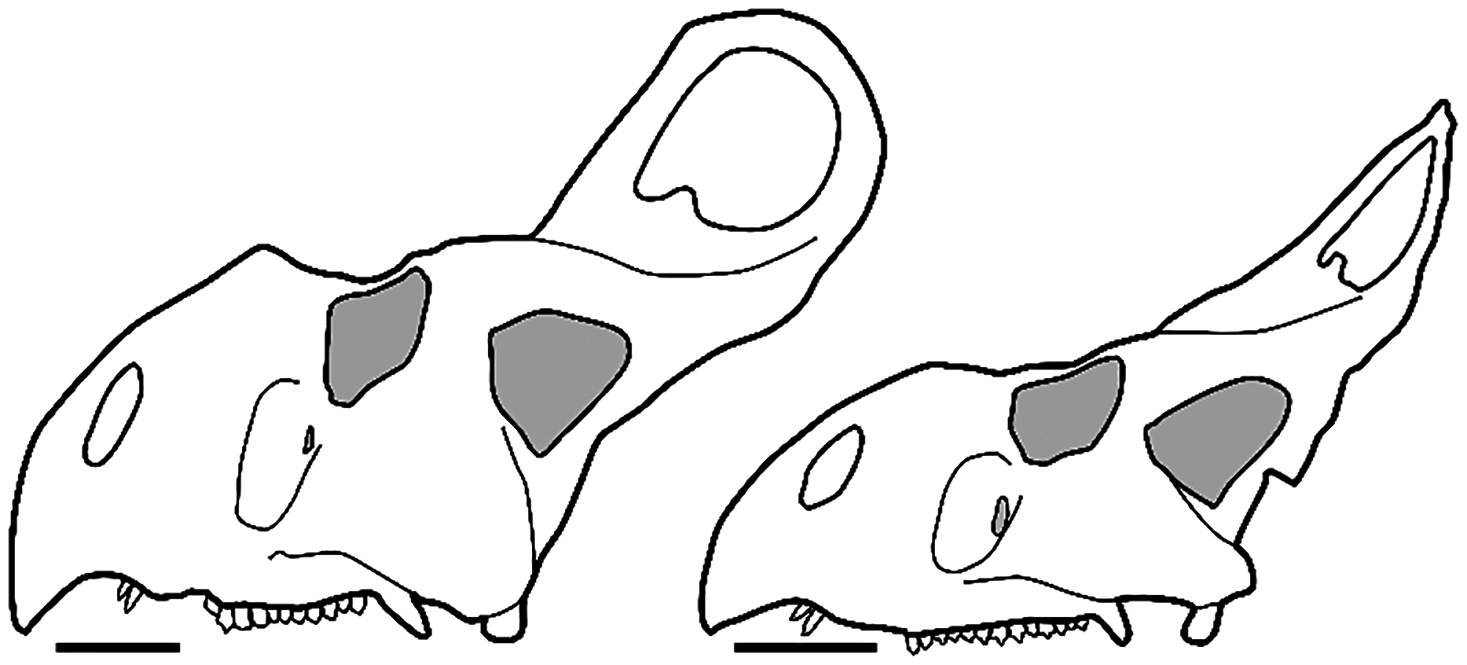

n, with both ''P. andrewsi'' and ''P. hellenikorhinus'' estimated around in length and in body mass. Although similar in overall body size, the latter had a relatively greater skull length. Both species can be differentiated by the following characteristics:

* ''P. andrewsi'' – Two teeth were present at the premaxilla; the snout was low and long; the nasal horn was a single, pointed structure; the bottom edge of the dentary was slightly curved.

* ''P. hellenikorhinus'' – Absence of premaxillary teeth; the snout was tall and broad; the nasal horn was divided into two pointed ridges; the bottom edge of the dentary was straight.

Skull

Theskull

The skull is a bone protective cavity for the brain. The skull is composed of four types of bone i.e., cranial bones, facial bones, ear ossicles and hyoid bone. However two parts are more prominent: the cranium and the mandible. In humans, th ...

of ''Protoceratops'' was relatively large compared to its body and robustly built. The skull of the type species, ''P. andrewsi'', had an average total length of nearly . On the other hand ''P. hellenikorhinus'' had a total skull length of about . The rear of the skull gave form to a pronounced neck frill

A neck frill is the relatively extensive margin seen on the back of the heads of reptiles with either a bony support such as those present on the skulls of dinosaurs of the suborder Marginocephalia or a cartilaginous one as in the frill-necke ...

(also known as "parietal frill") mostly composed of the and bones. The exact size and shape of the frill varied by individual; some had short, compact frills, while others had frills nearly half the length of the skull. The squamosal touched the (cheekbone) and was very enlarged and high having a curved end that built the borders of the frill. The parietals were the posteriormost bones of the skull and major elements of the frill. In a top view they had a triangular shape and were joined by the (bones of the skull roof

The skull roof, or the roofing bones of the skull, are a set of bones covering the brain, eyes and nostrils in bony fishes and all land-living vertebrates. The bones are derived from dermal bone and are part of the dermatocranium.

In compar ...

). Both parietals were coossified (fused), creating a long ridge on the center of the frill. The jugal was deep and sharply developed and along with the they formed a horn-like extension that pointed to below at the lateral sides of the skull. The (tip region of the jugal) was separated from the jugal by a prominent suture

Suture, literally meaning "seam", may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Suture'' (album), a 2000 album by American Industrial rock band Chemlab

* ''Suture'' (film), a 1993 film directed by Scott McGehee and David Siegel

* Suture (ban ...

; this suture was more noticeable in adults. The surfaces around the epijugal were coarse, indicating that it was covered by a horny sheath. Unlike the much derived ceratopsids

Ceratopsidae (sometimes spelled Ceratopidae) is a family of ceratopsian dinosaurs including ''Triceratops'', ''Centrosaurus'', and ''Styracosaurus''. All known species were quadrupedal herbivores from the Upper Cretaceous. All but one species ar ...

, the frontal and postorbital

The ''postorbital'' is one of the bones in vertebrate skulls which forms a portion of the dermal skull roof and, sometimes, a ring about the orbit. Generally, it is located behind the postfrontal and posteriorly to the orbital fenestra. In some ...

bones of ''Protoceratops'' were flat and lacked horn cores or supraorbital horns. The (small spur-like bone) joined the prefrontal over the front of the orbit

In celestial mechanics, an orbit is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an object or position in space such as ...

(eye socket). In ''P. hellenikorhinus'' the palpebral protruded upwards from the , just above the orbit and slightly meeting the frontal, creating a small horn-like structure. The was a near-rectangular bone located in front of the orbit, contributing to the shape of the latter. The sclerotic ring

Sclerotic rings are rings of bone found in the eyes of many animals in several groups of vertebrates, except for mammals and crocodilians. They can be made up of single bones or multiple segments and take their name from the sclera. They are bel ...

(structure that supports the eyeball

Eyes are organs of the visual system. They provide living organisms with vision, the ability to receive and process visual detail, as well as enabling several photo response functions that are independent of vision. Eyes detect light and con ...

), found inside the orbit, was circular in shape and formed by consecutive bony plates.

The snout

A snout is the protruding portion of an animal's face, consisting of its nose, mouth, and jaw. In many animals, the structure is called a muzzle, rostrum, or proboscis. The wet furless surface around the nostrils of the nose of many mammals is ...

was formed by the , r, r and bones. The nasal was generally rounded but some individuals had a sharp nasal boss (a feature that has been called "nasal horn"). In ''P. hellenikorhinus'' this boss was divided in two sharp and long ridges. The maxilla was very deep and had up to 15 alveoli Alveolus (; pl. alveoli, adj. alveolar) is a general anatomical term for a concave cavity or pit.

Uses in anatomy and zoology

* Pulmonary alveolus, an air sac in the lungs

** Alveolar cell or pneumocyte

** Alveolar duct

** Alveolar macrophage

* M ...

(tooth

A tooth ( : teeth) is a hard, calcified structure found in the jaws (or mouths) of many vertebrates and used to break down food. Some animals, particularly carnivores and omnivores, also use teeth to help with capturing or wounding prey, ...

sockets) on its underside or teeth bearing surface. The premaxilla had two alveoli on its lower edge—a character that was present at least on ''P. andrewsi''. The rostral bone was devoid of teeth, high and triangular in shape. It had a sharp end and rough texture, which reflects that a rhamphotheca

The beak, bill, or rostrum is an external anatomical structure found mostly in birds, but also in turtles, non-avian dinosaurs and a few mammals. A beak is used for eating, preening, manipulating objects, killing prey, fighting, probing for food, ...

(horny beak

The beak, bill, or rostrum is an external anatomical structure found mostly in birds, but also in turtles, non-avian dinosaurs and a few mammals. A beak is used for eating, preening, manipulating objects, killing prey, fighting, probing for fo ...

) was present. As a whole, the skull had four pairs of fenestra

A fenestra (fenestration; plural fenestrae or fenestrations) is any small opening or pore, commonly used as a term in the biological sciences. It is the Latin word for "window", and is used in various fields to describe a pore in an anatomical st ...

e (skull openings). The foremost hole, the nares (nostril opening), was oval-shaped and considerably smaller than the nostrils seen in ceratopsids. ''Protoceratops'' had large orbits, which measured around in diameter and had irregular shapes depending on the individual. The forward facing and closely located orbits combined with a narrow snout, gave ''Protoceratops'' a well-developed binocular vision

In biology, binocular vision is a type of vision in which an animal has two eyes capable of facing the same direction to perceive a single three-dimensional image of its surroundings. Binocular vision does not typically refer to vision where an ...

. Behind the eye was a slightly smaller fenestra known as the infratemporal fenestra, formed by the curves of the jugal and squamosal. The last openings of the skull were two parietal fenestrae (holes in the frill).

The lower jaw of ''Protoceratops'' was a large element composed of the , , , and . The predentary (frontmost bone) was very pointed and elongated, having a V-shaped symphyseal (bone union) region at the front. The dentary (teeth-bearing bone) was robust, deep, slightly recurved, and fused to the angular and surangular. A large and thick ridge ran along the lateral surface of the dentary that connected the coronoid process—a bony projection that extends upwards from the upper surface of the lower jaw behind the tooth row—and surangular. It bore up to 12-14 alveoli on its top margin. Both predentary and dentary had a series of foramina (small pits), the latter mostly on its anterior end. The coronoid (highest point of the lower jaw) was blunt-shaped and touched by the coronoid process of the dentary, being obscured by the jugal. The surangular was near triangular in shape and in old individuals it was coossified together with the coronoid process. The angular was located below the two latter bones and behind the dentary. It was a large and somewhat rounded bone that complemented the curvature of the dentary. On its inner surface it was attached to the . The articular was a smaller bone and had a concavity on its inner surface for the articulation with the quadrate.

''Protoceratops'' had leaf-shaped dentary and maxillary teeth that bore several denticles (serrations) on their respective edges. The crowns (upper exposed part) had two faces or lobes that were divided by a central ridge-like structure (also called "primary ridge"). The teeth were packed into a single row that created a shearing surface. Both dentary and maxillary teeth presented marked homodont

In anatomy, a heterodont (from Greek, meaning 'different teeth') is an animal which possesses more than a single tooth morphology.

In vertebrates, heterodont pertains to animals where teeth are differentiated into different forms. For example, ...

y—a dental condition where the teeth share a similar shape and size. ''P. andrewsi'' bore two small, peg to spike-like teeth that were located on the underside of each premaxilla. The second premaxillary tooth was larger than the first one. Unlike dentary and maxillary teeth, the premaxillary dentition was devoid of denticles, having a relatively smooth surface. All teeth had a single root (lower part inserted in the alveoli).

Postcranial skeleton

The

The vertebral column

The vertebral column, also known as the backbone or spine, is part of the axial skeleton. The vertebral column is the defining characteristic of a vertebrate in which the notochord (a flexible rod of uniform composition) found in all chordate ...

of ''Protoceratops'' had 9 cervical (neck), 12 dorsal (back), 8 sacral (pelvic) and over 40 caudal (tail) vertebrae. The centra

Centra is a convenience shop chain that operates throughout Ireland. The chain operates as a symbol group owned by Musgrave Group, the food wholesaler, meaning the stores are all owned by individual franchisees.

The chain has three different ...

(centrum; body of the vertebrae) of the first three cervicals were coossified together (, and third cervical respectively) creating a rigid structure. The neck was rather short and had poor flexibility. The atlas was the smallest cervical and consisted mainly of the centrum because the (upper, and pointy vertebral region) was a thin, narrow bar of bone that extended upwards and backwards to the base of the axis neural spine. The capitular facet (attachment site for chevron

Chevron (often relating to V-shaped patterns) may refer to:

Science and technology

* Chevron (aerospace), sawtooth patterns on some jet engines

* Chevron (anatomy), a bone