Proteolytic on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Proteolysis is the breakdown of

Proteolysis is the breakdown of

Research on Biological Roles and Variation of Snake Venoms.

Loma Linda University. including effects that are: * cytotoxic (cell-destroying) *

The Journal of Proteolysis

is an open access journal that provides an international forum for the electronic publication of the whole spectrum of high-quality articles and reviews in all areas of proteolysis and proteolytic pathways.

Proteolysis MAP from Center on Proteolytic Pathways

{{Enzymes Post-translational modification Metabolism EC 3.4

protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, res ...

s into smaller polypeptides or amino acids. Uncatalysed, the hydrolysis

Hydrolysis (; ) is any chemical reaction in which a molecule of water breaks one or more chemical bonds. The term is used broadly for substitution, elimination, and solvation reactions in which water is the nucleophile.

Biological hydrolys ...

of peptide bonds is extremely slow, taking hundreds of years. Proteolysis is typically catalysed

Catalysis () is the process of increasing the rate of a chemical reaction by adding a substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed in the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recyc ...

by cellular enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products ...

s called protease

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalyzes (increases reaction rate or "speeds up") proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the ...

s, but may also occur by intra-molecular digestion.

Proteolysis in organisms serves many purposes; for example, digestive enzymes

Digestive enzymes are a group of enzymes that break down polymeric macromolecules into their smaller building blocks, in order to facilitate their absorption into the cells of the body. Digestive enzymes are found in the digestive tracts of anima ...

break down proteins in food to provide amino acids for the organism, while proteolytic processing of a polypeptide chain after its synthesis may be necessary for the production of an active protein. It is also important in the regulation of some physiological and cellular processes including apoptosis, as well as preventing the accumulation of unwanted or misfolded proteins in cells. Consequently, abnormality in the regulation of proteolysis can cause disease.

Proteolysis can also be used as an analytical tool for studying proteins in the laboratory, and it may also be used in industry, for example in food processing and stain removal.

Biological functions

Post-translational proteolytic processing

Limited proteolysis of a polypeptide during or aftertranslation

Translation is the communication of the meaning of a source-language text by means of an equivalent target-language text. The English language draws a terminological distinction (which does not exist in every language) between ''transla ...

in protein synthesis often occurs for many proteins. This may involve removal of the N-terminal methionine, signal peptide, and/or the conversion of an inactive or non-functional protein to an active one. The precursor to the final functional form of protein is termed proprotein, and these proproteins may be first synthesized as preproprotein. For example, albumin

Albumin is a family of globular proteins, the most common of which are the serum albumins. All the proteins of the albumin family are water-soluble, moderately soluble in concentrated salt solutions, and experience heat denaturation. Albumins ...

is first synthesized as preproalbumin and contains an uncleaved signal peptide. This forms the proalbumin after the signal peptide is cleaved, and a further processing to remove the N-terminal 6-residue propeptide yields the mature form of the protein.

Removal of N-terminal methionine

The initiating methionine (and, in prokaryotes, fMet) may be removed during translation of the nascent protein. For '' E. coli'', fMet is efficiently removed if the second residue is small and uncharged, but not if the second residue is bulky and charged. In both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, the exposed N-terminal residue may determine the half-life of the protein according to theN-end rule The ''N''-end rule is a rule that governs the rate of protein degradation through recognition of the N-terminal residue of proteins. The rule states that the ''N''-terminal amino acid of a protein determines its half-life (time after which half of ...

.

Removal of the signal sequence

Proteins that are to be targeted to a particular organelle or for secretion have an N-terminal signal peptide that directs the protein to its final destination. This signal peptide is removed by proteolysis after their transport through amembrane

A membrane is a selective barrier; it allows some things to pass through but stops others. Such things may be molecules, ions, or other small particles. Membranes can be generally classified into synthetic membranes and biological membranes. ...

.

Cleavage of polyproteins

Some proteins and most eukaryotic polypeptide hormones are synthesized as a large precursor polypeptide known as a polyprotein that requires proteolytic cleavage into individual smaller polypeptide chains. The polyprotein pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) contains many polypeptide hormones. The cleavage pattern of POMC, however, may vary between different tissues, yielding different sets of polypeptide hormones from the same polyprotein. Manyviruses

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's ...

also produce their proteins initially as a single polypeptide chain that were translated from a polycistronic mRNA. This polypeptide is subsequently cleaved into individual polypeptide chains. Common names for the polyprotein include ''gag'' ( group-specific antigen) in retroviruses and '' ORF1ab'' in Nidovirales. The latter name refers to the fact that a slippery sequence

A slippery sequence is a small section of codon nucleotide sequences (usually UUUAAAC) that controls the rate and chance of ribosomal frameshifting. A slippery sequence causes a faster ribosomal transfer which in turn can cause the reading ribosom ...

in the mRNA that codes for the polypeptide causes ribosomal frameshifting, leading to two different lengths of peptidic chains (''a'' and ''ab'') at an approximately fixed ratio.

Cleavage of precursor proteins

Many proteins and hormones are synthesized in the form of their precursors -zymogen

In biochemistry, a zymogen (), also called a proenzyme (), is an inactive precursor of an enzyme. A zymogen requires a biochemical change (such as a hydrolysis reaction revealing the active site, or changing the configuration to reveal the activ ...

s, proenzymes, and prehormones. These proteins are cleaved to form their final active structures. Insulin, for example, is synthesized as preproinsulin, which yields proinsulin

Proinsulin is the prohormone precursor to insulin made in the beta cells of the islets of Langerhans, specialized regions of the pancreas. In humans, proinsulin is encoded by the ''INS'' gene. The islets of Langerhans only secrete between 1% and ...

after the signal peptide has been cleaved. The proinsulin is then cleaved at two positions to yield two polypeptide chains linked by two disulfide bonds

In biochemistry, a disulfide (or disulphide in British English) refers to a functional group with the structure . The linkage is also called an SS-bond or sometimes a disulfide bridge and is usually derived by the coupling of two thiol groups. In ...

. Removal of two C-terminal residues from the B-chain then yields the mature insulin. Protein folding

Protein folding is the physical process by which a protein chain is translated to its native three-dimensional structure, typically a "folded" conformation by which the protein becomes biologically functional. Via an expeditious and reproduc ...

occurs in the single-chain proinsulin form which facilitates formation of the ultimate inter-peptide disulfide bonds, and the ultimate intra-peptide disulfide bond, found in the native structure of insulin.

Proteases in particular are synthesized in the inactive form so that they may be safely stored in cells, and ready for release in sufficient quantity when required. This is to ensure that the protease is activated only in the correct location or context, as inappropriate activation of these proteases can be very destructive for an organism. Proteolysis of the zymogen yields an active protein; for example, when trypsinogen Trypsinogen () is the precursor form (or zymogen) of trypsin, a digestive enzyme. It is produced by the pancreas and found in pancreatic juice, along with amylase, lipase, and chymotrypsinogen. It is cleaved to its active form, trypsin, by ent ...

is cleaved to form trypsin

Trypsin is an enzyme in the first section of the small intestine that starts the digestion of protein molecules by cutting these long chains of amino acids into smaller pieces. It is a serine protease from the PA clan superfamily, found in the d ...

, a slight rearrangement of the protein structure that completes the active site of the protease occurs, thereby activating the protein.

Proteolysis can, therefore, be a method of regulating biological processes by turning inactive proteins into active ones. A good example is the blood clotting cascade whereby an initial event triggers a cascade of sequential proteolytic activation of many specific proteases, resulting in blood coagulation. The complement system of the immune response also involves a complex sequential proteolytic activation and interaction that result in an attack on invading pathogens.

Protein degradation

Protein degradation may take place intracellularly or extracellularly. In digestion of food, digestive enzymes may be released into the environment forextracellular digestion

Extracellular phototropic digestion is a process in which saprobionts feed by secreting enzymes through the cell membrane onto the food. The enzymes catalyze the digestion of the food ie diffusion, transport, osmotrophy or phagocytosis. Since dige ...

whereby proteolytic cleavage breaks proteins into smaller peptides and amino acids so that they may be absorbed and used. In animals the food may be processed extracellularly in specialized organs or guts, but in many bacteria the food may be internalized via phagocytosis

Phagocytosis () is the process by which a cell uses its plasma membrane to engulf a large particle (≥ 0.5 μm), giving rise to an internal compartment called the phagosome. It is one type of endocytosis. A cell that performs phagocytosis is ...

. Microbial degradation of protein in the environment can be regulated by nutrient availability. For example, limitation for major elements in proteins (carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur) induces proteolytic activity in the fungus ''Neurospora crassa

''Neurospora crassa'' is a type of red bread mold of the phylum Ascomycota. The genus name, meaning "nerve spore" in Greek, refers to the characteristic striations on the spores. The first published account of this fungus was from an infestation ...

'' as well as in of soil organism communities.

Proteins in cells are broken into amino acids. This intracellular degradation of protein serves multiple functions: It removes damaged and abnormal proteins and prevents their accumulation. It also serves to regulate cellular processes by removing enzymes and regulatory proteins that are no longer needed. The amino acids may then be reused for protein synthesis.

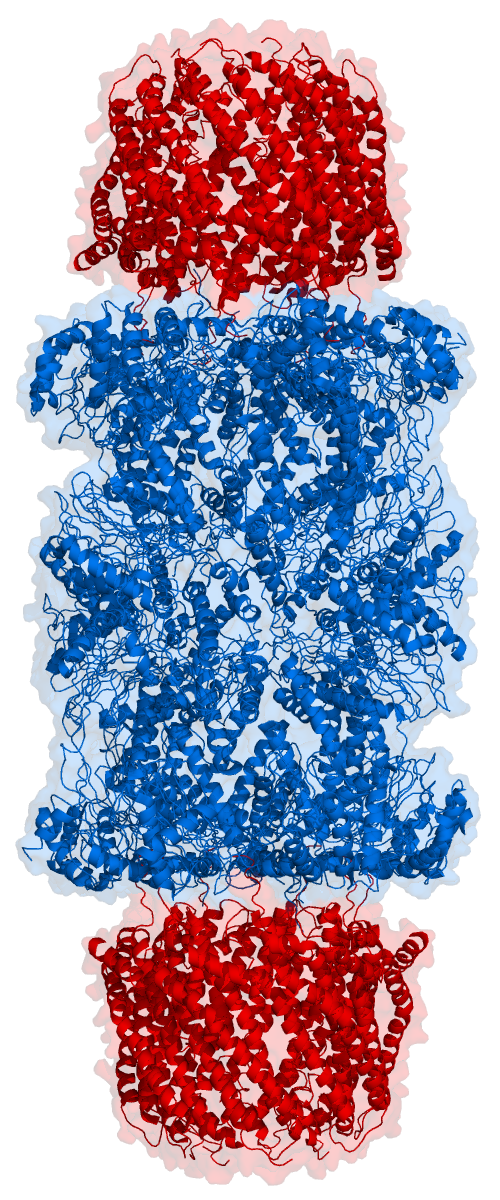

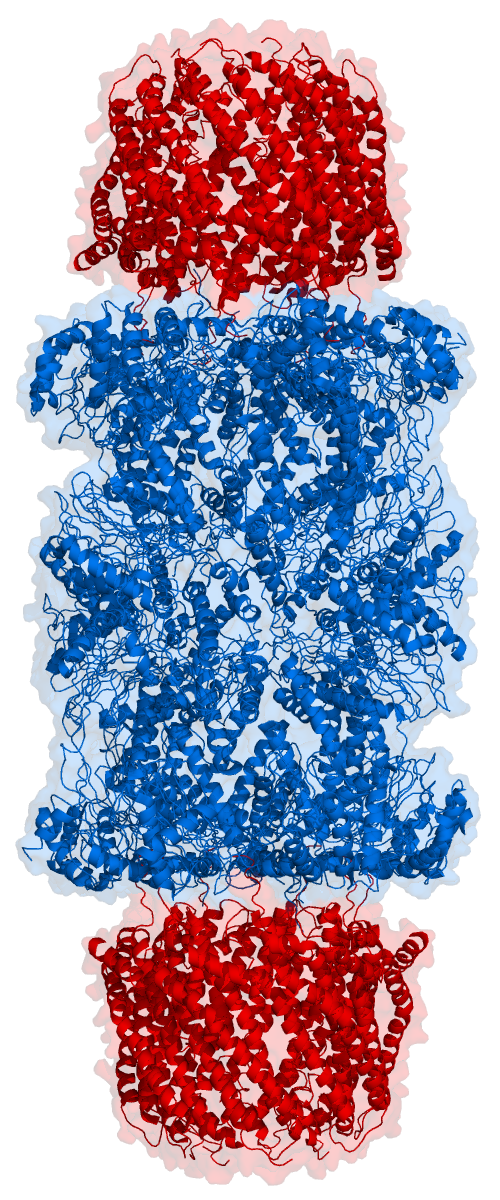

Lysosome and proteasome

The intracellular degradation of protein may be achieved in two ways - proteolysis inlysosome

A lysosome () is a membrane-bound organelle found in many animal cells. They are spherical vesicles that contain hydrolytic enzymes that can break down many kinds of biomolecules. A lysosome has a specific composition, of both its membrane pr ...

, or a ubiquitin

Ubiquitin is a small (8.6 kDa) regulatory protein found in most tissues of eukaryotic organisms, i.e., it is found ''ubiquitously''. It was discovered in 1975 by Gideon Goldstein and further characterized throughout the late 1970s and 1980s. Fo ...

-dependent process that targets unwanted proteins to proteasome. The autophagy-lysosomal pathway is normally a non-selective process, but it may become selective upon starvation whereby proteins with peptide sequence KFERQ or similar are selectively broken down. The lysosome contains a large number of proteases such as cathepsins

Cathepsins (Ancient Greek ''kata-'' "down" and ''hepsein'' "boil"; abbreviated CTS) are proteases (enzymes that degrade proteins) found in all animals as well as other organisms. There are approximately a dozen members of this family, which are di ...

.

The ubiquitin-mediated process is selective. Proteins marked for degradation are covalently linked to ubiquitin. Many molecules of ubiquitin may be linked in tandem to a protein destined for degradation. The polyubiquinated protein is targeted to an ATP-dependent protease complex, the proteasome. The ubiquitin is released and reused, while the targeted protein is degraded.

Rate of intracellular protein degradation

Different proteins are degraded at different rates. Abnormal proteins are quickly degraded, whereas the rate of degradation of normal proteins may vary widely depending on their functions. Enzymes at important metabolic control points may be degraded much faster than those enzymes whose activity is largely constant under all physiological conditions. One of the most rapidly degraded proteins isornithine decarboxylase

The enzyme ornithine decarboxylase (, ODC) catalyzes the decarboxylation of ornithine (a product of the urea cycle) to form putrescine. This reaction is the committed step in polyamine synthesis. In humans, this protein has 461 amino acids a ...

, which has a half-life of 11 minutes. In contrast, other proteins like actin

Actin is a family of globular multi-functional proteins that form microfilaments in the cytoskeleton, and the thin filaments in muscle fibrils. It is found in essentially all eukaryotic cells, where it may be present at a concentration of ov ...

and myosin have a half-life of a month or more, while, in essence, haemoglobin

Hemoglobin (haemoglobin BrE) (from the Greek word αἷμα, ''haîma'' 'blood' + Latin ''globus'' 'ball, sphere' + ''-in'') (), abbreviated Hb or Hgb, is the iron-containing oxygen-transport metalloprotein present in red blood cells (erythrocyte ...

lasts for the entire life-time of an erythrocyte

Red blood cells (RBCs), also referred to as red cells, red blood corpuscles (in humans or other animals not having nucleus in red blood cells), haematids, erythroid cells or erythrocytes (from Greek ''erythros'' for "red" and ''kytos'' for "holl ...

.

The N-end rule The ''N''-end rule is a rule that governs the rate of protein degradation through recognition of the N-terminal residue of proteins. The rule states that the ''N''-terminal amino acid of a protein determines its half-life (time after which half of ...

may partially determine the half-life of a protein, and proteins with segments rich in proline, glutamic acid, serine, and threonine (the so-called PEST proteins) have short half-life. Other factors suspected to affect degradation rate include the rate deamination of glutamine and asparagine

Asparagine (symbol Asn or N) is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated −NH form under biological conditions), an α-carboxylic acid group (which is in the depro ...

and oxidation of cystein, histidine

Histidine (symbol His or H) is an essential amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated –NH3+ form under biological conditions), a carboxylic acid group (which is in the d ...

, and methionine, the absence of stabilizing ligands, the presence of attached carbohydrate or phosphate groups, the presence of free α-amino group, the negative charge of protein, and the flexibility and stability of the protein. Proteins with larger degrees of intrinsic disorder also tend to have short cellular half-life, with disordered segments having been proposed to facilitate efficient initiation of degradation by the proteasome.

The rate of proteolysis may also depend on the physiological state of the organism, such as its hormonal state as well as nutritional status. In time of starvation, the rate of protein degradation increases.

Digestion

In humandigestion

Digestion is the breakdown of large insoluble food molecules into small water-soluble food molecules so that they can be absorbed into the watery blood plasma. In certain organisms, these smaller substances are absorbed through the small intest ...

, proteins in food are broken down into smaller peptide chains by digestive enzymes

Digestive enzymes are a group of enzymes that break down polymeric macromolecules into their smaller building blocks, in order to facilitate their absorption into the cells of the body. Digestive enzymes are found in the digestive tracts of anima ...

such as pepsin

Pepsin is an endopeptidase that breaks down proteins into smaller peptides. It is produced in the gastric chief cells of the stomach lining and is one of the main digestive enzymes in the digestive systems of humans and many other animals, w ...

, trypsin

Trypsin is an enzyme in the first section of the small intestine that starts the digestion of protein molecules by cutting these long chains of amino acids into smaller pieces. It is a serine protease from the PA clan superfamily, found in the d ...

, chymotrypsin, and elastase

In molecular biology, elastase is an enzyme from the class of ''proteases (peptidases)'' that break down proteins. In particular, it is a serine protease.

Forms and classification

Eight human genes exist for elastase:

Some bacteria (includin ...

, and into amino acids by various enzymes such as carboxypeptidase, aminopeptidase, and dipeptidase

Dipeptidases are enzymes secreted by enterocytes into the small intestine. Dipeptidases hydrolyze bound pairs of amino acids, called dipeptides.

Dipeptidases are secreted onto the brush border of the villi in the small intestine, where they cleave ...

. It is necessary to break down proteins into small peptides (tripeptides and dipeptides) and amino acids so they can be absorbed by the intestines, and the absorbed tripeptides and dipeptides are also further broken into amino acids intracellularly before they enter the bloodstream. Different enzymes have different specificity for their substrate; trypsin, for example, cleaves the peptide bond after a positively charged residue ( arginine and lysine); chymotrypsin cleaves the bond after an aromatic residue ( phenylalanine, tyrosine

-Tyrosine or tyrosine (symbol Tyr or Y) or 4-hydroxyphenylalanine is one of the 20 standard amino acids that are used by cells to synthesize proteins. It is a non-essential amino acid with a polar side group. The word "tyrosine" is from the G ...

, and tryptophan

Tryptophan (symbol Trp or W)

is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. Tryptophan contains an α-amino group, an α-carboxylic acid group, and a side chain indole, making it a polar molecule with a non-polar aromatic ...

); elastase cleaves the bond after a small non-polar residue such as alanine or glycine.

In order to prevent inappropriate or premature activation of the digestive enzymes (they may, for example, trigger pancreatic self-digestion causing pancreatitis), these enzymes are secreted as inactive zymogen. The precursor of pepsin

Pepsin is an endopeptidase that breaks down proteins into smaller peptides. It is produced in the gastric chief cells of the stomach lining and is one of the main digestive enzymes in the digestive systems of humans and many other animals, w ...

, pepsinogen, is secreted by the stomach, and is activated only in the acidic environment found in stomach. The pancreas

The pancreas is an organ of the digestive system and endocrine system of vertebrates. In humans, it is located in the abdomen behind the stomach and functions as a gland. The pancreas is a mixed or heterocrine gland, i.e. it has both an en ...

secretes the precursors of a number of proteases such as trypsin

Trypsin is an enzyme in the first section of the small intestine that starts the digestion of protein molecules by cutting these long chains of amino acids into smaller pieces. It is a serine protease from the PA clan superfamily, found in the d ...

and chymotrypsin. The zymogen of trypsin is trypsinogen Trypsinogen () is the precursor form (or zymogen) of trypsin, a digestive enzyme. It is produced by the pancreas and found in pancreatic juice, along with amylase, lipase, and chymotrypsinogen. It is cleaved to its active form, trypsin, by ent ...

, which is activated by a very specific protease, enterokinase, secreted by the mucosa of the duodenum. The trypsin, once activated, can also cleave other trypsinogens as well as the precursors of other proteases such as chymotrypsin and carboxypeptidase to activate them.

In bacteria, a similar strategy of employing an inactive zymogen or prezymogen is used. Subtilisin, which is produced by ''Bacillus subtilis

''Bacillus subtilis'', known also as the hay bacillus or grass bacillus, is a Gram-positive, catalase-positive bacterium, found in soil and the gastrointestinal tract of ruminants, humans and marine sponges. As a member of the genus ''Bacillus ...

'', is produced as preprosubtilisin, and is released only if the signal peptide is cleaved and autocatalytic proteolytic activation has occurred.

Cellular regulation

Proteolysis is also involved in the regulation of many cellular processes by activating or deactivating enzymes, transcription factors, and receptors, for example in the biosynthesis of cholesterol, or the mediation of thrombin signalling throughprotease-activated receptor

Protease-activated receptors (PAR) are a subfamily of related G protein-coupled receptors that are activated by cleavage of part of their extracellular domain. They are highly expressed in platelets, and also on endothelial cells, myocytes an ...

s.

Some enzymes at important metabolic control points such as ornithine decarboxylase is regulated entirely by its rate of synthesis and its rate of degradation. Other rapidly degraded proteins include the protein products of proto-oncogenes, which play central roles in the regulation of cell growth.

Cell cycle regulation

Cyclins are a group of proteins that activate kinases involved in cell division. The degradation of cyclins is the key step that governs the exit from mitosis and progress into the nextcell cycle

The cell cycle, or cell-division cycle, is the series of events that take place in a cell that cause it to divide into two daughter cells. These events include the duplication of its DNA (DNA replication) and some of its organelles, and sub ...

. Cyclins accumulate in the course the cell cycle, then abruptly disappear just before the anaphase

Anaphase () is the stage of mitosis after the process of metaphase, when replicated chromosomes are split and the newly-copied chromosomes (daughter chromatids) are moved to opposite poles of the cell. Chromosomes also reach their overall maxim ...

of mitosis. The cyclins are removed via a ubiquitin-mediated proteolytic pathway.

Apoptosis

Caspases are an important group of proteases involved in apoptosis orprogrammed cell death

Programmed cell death (PCD; sometimes referred to as cellular suicide) is the death of a cell (biology), cell as a result of events inside of a cell, such as apoptosis or autophagy. PCD is carried out in a biological process, which usually confers ...

. The precursors of caspase, procaspase, may be activated by proteolysis through its association with a protein complex that forms apoptosome

The apoptosome is a large quaternary protein structure formed in the process of apoptosis. Its formation is triggered by the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria in response to an internal (intrinsic) or external (extrinsic) cell death st ...

, or by granzyme B

Granzyme B (GrB) is one of the serine protease granzymes most commonly found in the granules of natural killer cells (NK cells) and cytotoxic T cells. It is secreted by these cells along with the pore forming protein perforin to mediate apoptosi ...

, or via the death receptor

The tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily (TNFRSF) is a protein superfamily of cytokine receptors characterized by the ability to bind tumor necrosis factors (TNFs) via an extracellular cysteine-rich domain. With the exception of nerve growt ...

pathways.

Autoproteolysis

Autoproteolysis takes place in some proteins, whereby the peptide bond is cleaved in a self-catalyzed intramolecular reaction. Unlikezymogen

In biochemistry, a zymogen (), also called a proenzyme (), is an inactive precursor of an enzyme. A zymogen requires a biochemical change (such as a hydrolysis reaction revealing the active site, or changing the configuration to reveal the activ ...

s, these autoproteolytic proteins participate in a "single turnover" reaction and do not catalyze further reactions post-cleavage. Examples include cleavage of the Asp-Pro bond in a subset of von Willebrand factor

Von Willebrand factor (VWF) () is a blood glycoprotein involved in hemostasis, specifically, platelet adhesion. It is deficient and/or defective in von Willebrand disease and is involved in many other diseases, including thrombotic thrombocytope ...

type D (VWD) domains and ''Neisseria meningitidis

''Neisseria meningitidis'', often referred to as meningococcus, is a Gram-negative bacterium that can cause meningitis and other forms of meningococcal disease such as meningococcemia, a life-threatening sepsis. The bacterium is referred to as a ...

'' FrpC self-processing domain, cleavage of the Asn-Pro bond in '' Salmonella'' FlhB protein, ''Yersinia

''Yersinia'' is a genus of bacteria in the family Yersiniaceae. ''Yersinia'' species are Gram-negative, coccobacilli bacteria, a few micrometers long and fractions of a micrometer in diameter, and are facultative anaerobes. Some members of ''Yer ...

'' YscU protein, as well as cleavage of the Gly-Ser bond in a subset of sea urchin sperm protein, enterokinase, and agrin (SEA) domains. In some cases, the autoproteolytic cleavage is promoted by conformational strain of the peptide bond.

Proteolysis and diseases

Abnormal proteolytic activity is associated with many diseases. In pancreatitis, leakage of proteases and their premature activation in the pancreas results in the self-digestion of thepancreas

The pancreas is an organ of the digestive system and endocrine system of vertebrates. In humans, it is located in the abdomen behind the stomach and functions as a gland. The pancreas is a mixed or heterocrine gland, i.e. it has both an en ...

. People with diabetes mellitus

Diabetes, also known as diabetes mellitus, is a group of metabolic disorders characterized by a high blood sugar level ( hyperglycemia) over a prolonged period of time. Symptoms often include frequent urination, increased thirst and increased ...

may have increased lysosomal activity and the degradation of some proteins can increase significantly. Chronic inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a long-term autoimmune disorder that primarily affects joints. It typically results in warm, swollen, and painful joints. Pain and stiffness often worsen following rest. Most commonly, the wrist and hands are invol ...

may involve the release of lysosomal enzymes into extracellular space that break down surrounding tissues. Abnormal proteolysis may result in many age-related neurological diseases such as Alzheimer's due to generation and ineffective removal of peptides that aggregate in cells.

Proteases may be regulated by antiproteases or protease inhibitors

Protease inhibitors (PIs) are medications that act by interfering with enzymes that cleave proteins. Some of the most well known are antiviral drugs widely used to treat HIV/AIDS and hepatitis C. These protease inhibitors prevent viral replicat ...

, and imbalance between proteases and antiproteases can result in diseases, for example, in the destruction of lung tissues in emphysema brought on by smoking tobacco. Smoking is thought to increase the neutrophils and macrophages

Macrophages (abbreviated as M φ, MΦ or MP) ( el, large eaters, from Greek ''μακρός'' (') = large, ''φαγεῖν'' (') = to eat) are a type of white blood cell of the immune system that engulfs and digests pathogens, such as cancer ce ...

in the lung which release excessive amount of proteolytic enzymes such as elastase

In molecular biology, elastase is an enzyme from the class of ''proteases (peptidases)'' that break down proteins. In particular, it is a serine protease.

Forms and classification

Eight human genes exist for elastase:

Some bacteria (includin ...

, such that they can no longer be inhibited by serpin

Serpins are a superfamily of proteins with similar structures that were first identified for their protease inhibition activity and are found in all kingdoms of life. The acronym serpin was originally coined because the first serpins to be id ...

s such as α1-antitrypsin, thereby resulting in the breaking down of connective tissues in the lung. Other proteases and their inhibitors may also be involved in this disease, for example matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs).

Other diseases linked to aberrant proteolysis include muscular dystrophy, degenerative skin disorders, respiratory and gastrointestinal diseases, and malignancy

Malignancy () is the tendency of a medical condition to become progressively worse.

Malignancy is most familiar as a characterization of cancer. A ''malignant'' tumor contrasts with a non-cancerous ''benign'' tumor in that a malignancy is not s ...

.

Non-enzymatic processes

Protein backbones are very stable in water at neutral pH and room temperature, although the rate of hydrolysis of different peptide bonds can vary. The half life of a peptide bond under normal conditions can range from 7 years to 350 years, even higher for peptides protected by modified terminus or within the protein interior. The rate of hydrolysis however can be significantly increased by extremes of pH and heat. Spontaneous cleavage of proteins may also involve catalysis by zinc on serine and threonine. Strong mineral acids can readily hydrolyse the peptide bonds in a protein (acid hydrolysis

In organic chemistry, acid hydrolysis is a hydrolysis process in which a protic acid is used to catalyze the cleavage of a chemical bond via a nucleophilic substitution reaction, with the addition of the elements of water (H2O). For example, in th ...

). The standard way to hydrolyze a protein or peptide into its constituent amino acids for analysis is to heat it to 105 °C for around 24 hours in 6M hydrochloric acid

Hydrochloric acid, also known as muriatic acid, is an aqueous solution of hydrogen chloride. It is a colorless solution with a distinctive pungent smell. It is classified as a strong acid

Acid strength is the tendency of an acid, symbol ...

. However, some proteins are resistant to acid hydrolysis. One well-known example is ribonuclease A

Pancreatic ribonuclease family (, ''RNase'', ''RNase I'', ''RNase A'', ''pancreatic RNase'', ''ribonuclease I'', ''endoribonuclease I'', ''ribonucleic phosphatase'', ''alkaline ribonuclease'', ''ribonuclease'', ''gene S glycoproteins'', ''Ceratit ...

, which can be purified by treating crude extracts with hot sulfuric acid so that other proteins become degraded while ribonuclease A is left intact.

Certain chemicals cause proteolysis only after specific residues, and these can be used to selectively break down a protein into smaller polypeptides for laboratory analysis. For example, cyanogen bromide

Cyanogen bromide is the inorganic compound with the formula (CN)Br or BrCN. It is a colorless solid that is widely used to modify biopolymers, fragment proteins and peptides (cuts the C-terminus of methionine), and synthesize other compounds. ...

cleaves the peptide bond after a methionine. Similar methods may be used to specifically cleave tryptophan

Tryptophan (symbol Trp or W)

is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. Tryptophan contains an α-amino group, an α-carboxylic acid group, and a side chain indole, making it a polar molecule with a non-polar aromatic ...

yl, aspartyl

Aspartic acid (symbol Asp or D; the ionic form is known as aspartate), is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. Like all other amino acids, it contains an amino group and a carboxylic acid. Its α-amino group is in the pro ...

, cysteinyl

Cysteine (symbol Cys or C; ) is a semiessential proteinogenic amino acid with the formula . The thiol side chain in cysteine often participates in enzymatic reactions as a nucleophile.

When present as a deprotonated catalytic residue, some ...

, and asparaginyl peptide bonds. Acids such as trifluoroacetic acid

Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) is an organofluorine compound with the chemical formula CF3CO2H. It is a structural analogue of acetic acid with all three of the acetyl group's hydrogen atoms replaced by fluorine atoms and is a colorless liquid with ...

and formic acid may be used for cleavage.

Like other biomolecules, proteins can also be broken down by high heat alone. At 250 °C, the peptide bond may be easily hydrolyzed, with its half-life dropping to about a minute. Protein may also be broken down without hydrolysis through pyrolysis

The pyrolysis (or devolatilization) process is the thermal decomposition of materials at elevated temperatures, often in an inert atmosphere. It involves a change of chemical composition. The word is coined from the Greek-derived elements ''py ...

; small heterocyclic compounds may start to form upon degradation. Above 500 °C, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon

A polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) is a class of organic compounds that is composed of multiple aromatic rings. The simplest representative is naphthalene, having two aromatic rings and the three-ring compounds anthracene and phenanthrene. ...

s may also form, which is of interest in the study of generation of carcinogens in tobacco smoke and cooking at high heat.

Laboratory applications

Proteolysis is also used in research and diagnostic applications: * Cleavage of fusion protein so that the fusion partner andprotein tag

Protein tags are peptide sequences genetically grafted onto a recombinant protein. Tags are attached to proteins for various purposes. They can be added to either end of the target protein, so they are either C-terminus or N-terminus specific or a ...

used in protein expression and purification may be removed. The proteases used have high degree of specificity, such as thrombin

Thrombin (, ''fibrinogenase'', ''thrombase'', ''thrombofort'', ''topical'', ''thrombin-C'', ''tropostasin'', ''activated blood-coagulation factor II'', ''blood-coagulation factor IIa'', ''factor IIa'', ''E thrombin'', ''beta-thrombin'', ''gamma- ...

, enterokinase, and TEV protease, so that only the targeted sequence may be cleaved.

* Complete inactivation of undesirable enzymatic activity or removal of unwanted proteins. For example, proteinase K

In molecular biology Proteinase K (, ''protease K'', ''endopeptidase K'', ''Tritirachium alkaline proteinase'', ''Tritirachium album serine proteinase'', ''Tritirachium album proteinase K'') is a broad-spectrum serine protease. The enzyme was dis ...

, a broad-spectrum proteinase stable in urea

Urea, also known as carbamide, is an organic compound with chemical formula . This amide has two amino groups (–) joined by a carbonyl functional group (–C(=O)–). It is thus the simplest amide of carbamic acid.

Urea serves an important ...

and SDS, is often used in the preparation of nucleic acids

Nucleic acids are biopolymers, macromolecules, essential to all known forms of life. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomers made of three components: a 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main cl ...

to remove unwanted nuclease contaminants that may otherwise degrade the DNA or RNA.

* Partial inactivation, or changing the functionality, of specific protein. For example, treatment of DNA polymerase I with subtilisin yields the Klenow fragment, which retains its polymerase function but lacks 5'-exonuclease activity.

* Digestion of proteins in solution for proteome analysis by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

A liquid is a nearly incompressible fluid that conforms to the shape of its container but retains a (nearly) constant volume independent of pressure. As such, it is one of the four fundamental states of matter (the others being solid, gas, a ...

(LC-MS). This may also be done by in-gel digestion The in-gel digestion step is a part of the sample preparation for the mass spectrometric identification of proteins in course of proteomic analysis. The method was introduced in 1992 by Rosenfeld.Rosenfeld, J et al., ''Anal Biochem'', 1992, 203 ( ...

of proteins after separation by gel electrophoresis for the identification by mass spectrometry.

* Analysis of the stability of folded domain under a wide range of conditions.

* Increasing success rate of crystallisation projects

* Production of digested protein used in growth media to culture bacteria and other organisms, e.g. tryptone in Lysogeny Broth.

Protease enzymes

Proteases may be classified according to the catalytic group involved in its active site. *Cysteine protease

Cysteine proteases, also known as thiol proteases, are hydrolase enzymes that degrade proteins. These proteases share a common catalytic mechanism that involves a nucleophilic cysteine thiol in a catalytic triad or dyad.

Discovered by Gopal Ch ...

*Serine protease

Serine proteases (or serine endopeptidases) are enzymes that cleave peptide bonds in proteins. Serine serves as the nucleophilic amino acid at the (enzyme's) active site.

They are found ubiquitously in both eukaryotes and prokaryotes. Seri ...

*Threonine protease

Threonine proteases are a family of proteolytic enzymes harbouring a threonine (Thr) residue within the active site. The prototype members of this class of enzymes are the catalytic subunits of the proteasome, however the acyltransferases conver ...

*Aspartic protease

Aspartic proteases are a catalytic type of protease enzymes that use an activated water molecule bound to one or more aspartate residues for catalysis of their peptide substrates. In general, they have two highly conserved aspartates in the activ ...

* Glutamic protease

*Metalloprotease

A metalloproteinase, or metalloprotease, is any protease enzyme whose catalytic mechanism involves a metal. An example is ADAM12 which plays a significant role in the fusion of muscle cells during embryo development, in a process known as myo ...

* Asparagine peptide lyase

Venoms

Certain types of venom, such as those produced by venomoussnake

Snakes are elongated, limbless, carnivorous reptiles of the suborder Serpentes . Like all other squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping scales. Many species of snakes have skulls with several more j ...

s, can also cause proteolysis. These venoms are, in fact, complex digestive fluids that begin their work outside of the body. Proteolytic venoms cause a wide range of toxic effects,Hayes WK. 2005Research on Biological Roles and Variation of Snake Venoms.

Loma Linda University. including effects that are: * cytotoxic (cell-destroying) *

hemotoxic

Hemotoxins, haemotoxins or hematotoxins are toxins that destroy red blood cells, disrupt blood clotting, and/or cause organ degeneration and generalized tissue damage. The term ''hemotoxin'' is to some degree a misnomer since toxins that damage t ...

(blood-destroying)

* myotoxic (muscle-destroying)

* hemorrhagic

Bleeding, hemorrhage, haemorrhage or blood loss, is blood escaping from the circulatory system from damaged blood vessels. Bleeding can occur internally, or externally either through a natural opening such as the mouth, nose, ear, urethra, vag ...

(bleeding)

See also

*The Proteolysis Map

The Proteolysis MAP (PMAP) is an integrated web resource focused on proteases.

Rationale

PMAP is to aid the protease researchers in reasoning about proteolytic networks and metabolic pathways.

History and funding

PMAP was originally created ...

* PROTOMAP a proteomic technology for identifying proteolytic substrates

* Proteasome

* In-gel digestion The in-gel digestion step is a part of the sample preparation for the mass spectrometric identification of proteins in course of proteomic analysis. The method was introduced in 1992 by Rosenfeld.Rosenfeld, J et al., ''Anal Biochem'', 1992, 203 ( ...

* Ubiquitin

Ubiquitin is a small (8.6 kDa) regulatory protein found in most tissues of eukaryotic organisms, i.e., it is found ''ubiquitously''. It was discovered in 1975 by Gideon Goldstein and further characterized throughout the late 1970s and 1980s. Fo ...

References

Further reading

*External links

The Journal of Proteolysis

is an open access journal that provides an international forum for the electronic publication of the whole spectrum of high-quality articles and reviews in all areas of proteolysis and proteolytic pathways.

Proteolysis MAP from Center on Proteolytic Pathways

{{Enzymes Post-translational modification Metabolism EC 3.4