Propiska in the Soviet Union on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A propiska ( rus, –ø—Ä–æ–ø–∏ÃÅ—Å–∫–∞, p=pr…êÀàp ≤isk…ô, a=Ru-–ø—Ä–æ–ø–∏—Å–∫–∞.ogg, plural: ''propiski'') was both a

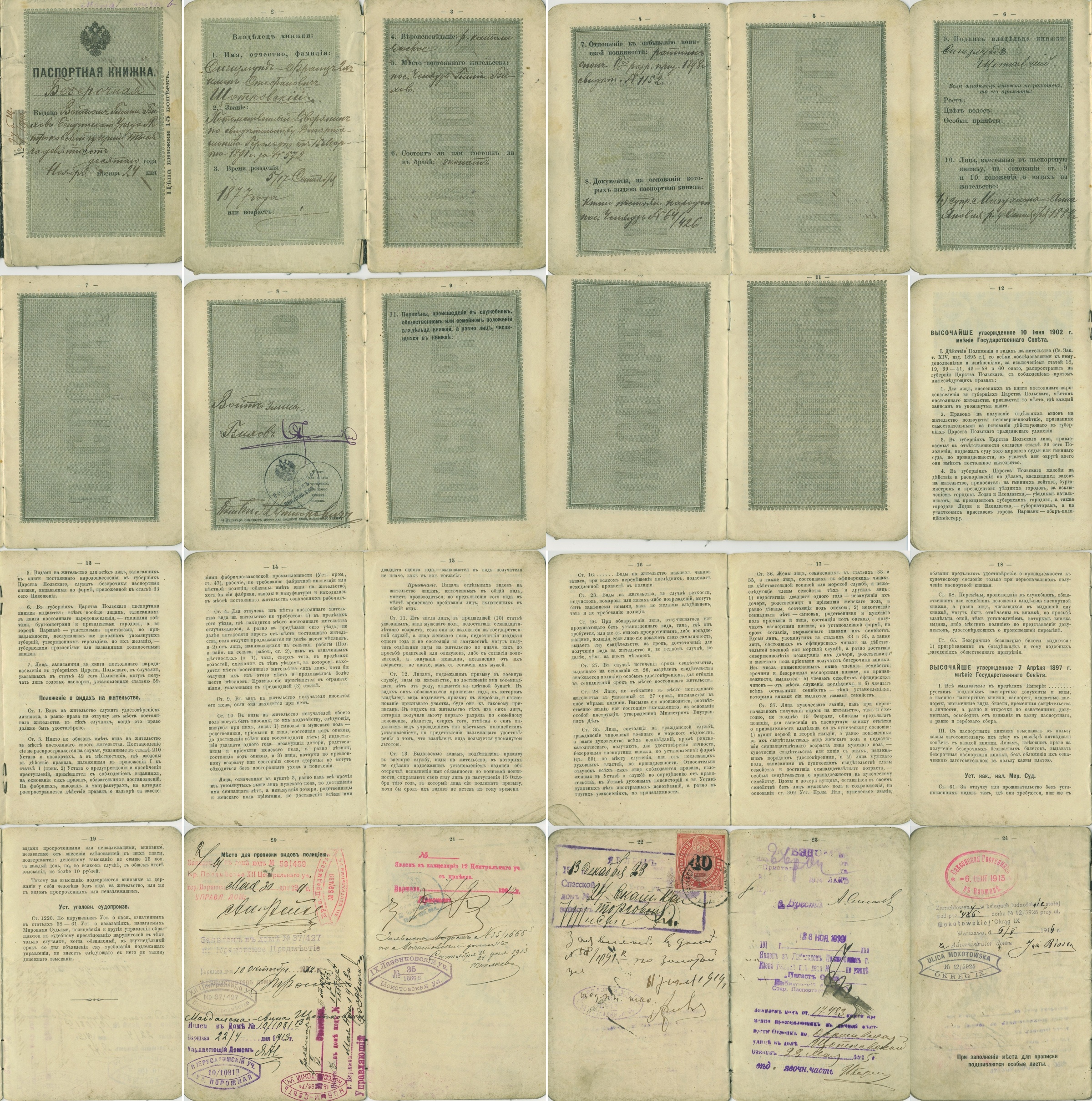

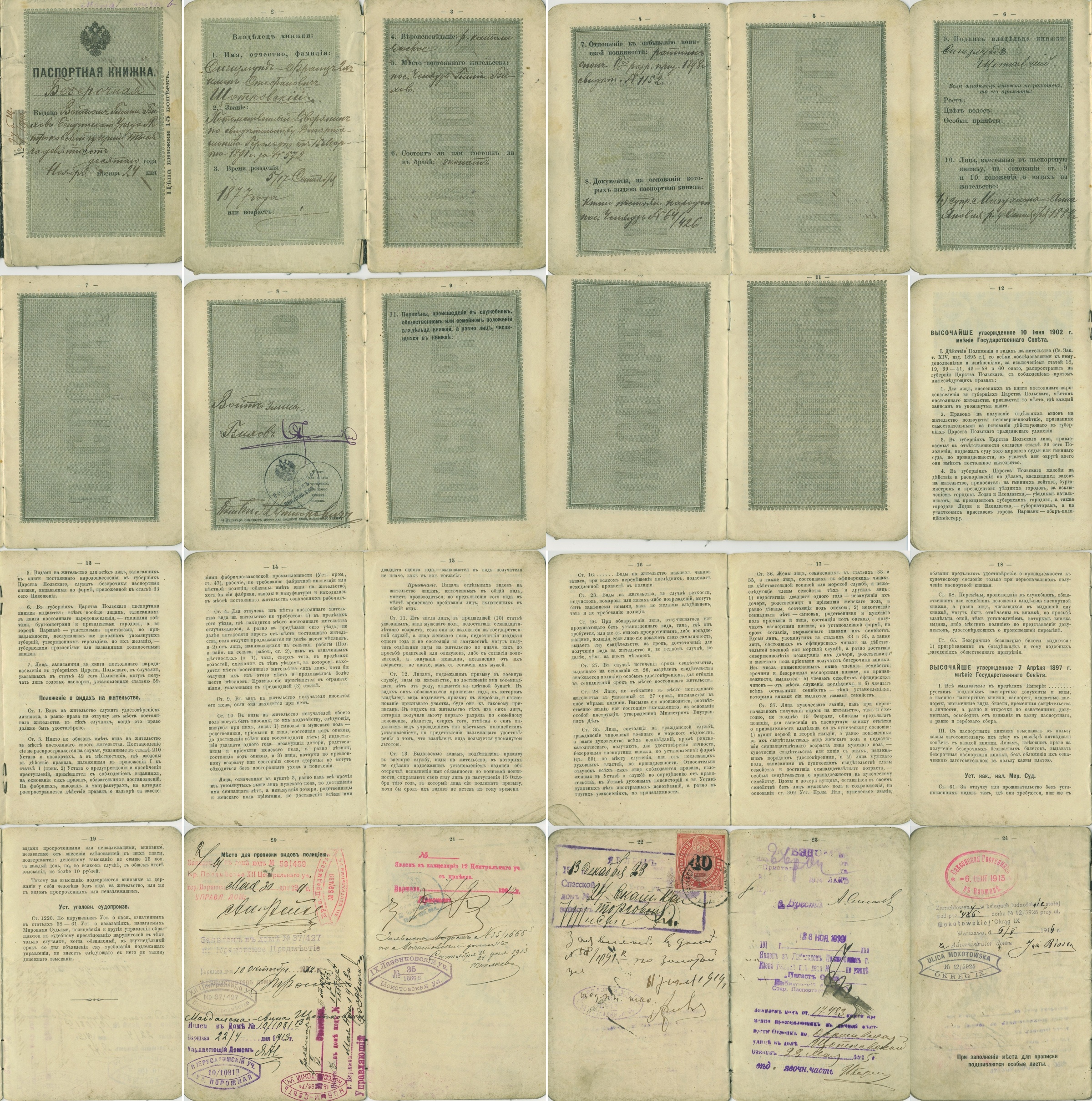

Originally, the noun ''propiska'' meant the clerical procedure of ''registration'', of enrolling the person (writing his or her name) into the police records of the local population (or writing down the police permission into the person's identification document - see below). Dahl's Explanatory Dictionary describes this procedure as "to enroll he documentin a book and stamp it". Page 20 of the internal passport of the Russian Empire (see illustration) was entitled ''Место для пропи́ски ви́довъ поли́цiею'' ("Space for registration of ''vid''s by police"). Five blank pages (20 to 24) were gradually filled with stamps with the residential address written in. It allowed a person to reside in his/her relevant locality. Article 61 of the Regulations adopted on February 7, 1897 (see p. 18–19 of the passport) imposed a fine for those found outside the administrative unit (as a rule,

Originally, the noun ''propiska'' meant the clerical procedure of ''registration'', of enrolling the person (writing his or her name) into the police records of the local population (or writing down the police permission into the person's identification document - see below). Dahl's Explanatory Dictionary describes this procedure as "to enroll he documentin a book and stamp it". Page 20 of the internal passport of the Russian Empire (see illustration) was entitled ''Место для пропи́ски ви́довъ поли́цiею'' ("Space for registration of ''vid''s by police"). Five blank pages (20 to 24) were gradually filled with stamps with the residential address written in. It allowed a person to reside in his/her relevant locality. Article 61 of the Regulations adopted on February 7, 1897 (see p. 18–19 of the passport) imposed a fine for those found outside the administrative unit (as a rule,

Following the

Following the

Constitutional Court strikes down internal passport system

Äîarticle in ''

Russian ombudsman on propiska in modern Russia

Civil registries Soviet law Soviet internal politics Identity documents of the Soviet Union

residency permit

A residence permit (less commonly ''residency permit'') is a document or card required in some regions, allowing a foreign national to reside in a country for a fixed or indefinite length of time.

These may be permits for temporary residency, or p ...

and a migration-recording tool, used in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

before 1917 and in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

from the 1930s. Literally, the word ''propiska'' means "inscription", alluding to the inscription in a state internal passport permitting a person to reside in a given place. For a state-owned or third-party-owned property, having a ''propiska'' meant the inclusion of a person in the rental contract associated with a dwelling. A propiska was certified via local police (Militsiya

''Militsiya'' ( rus, –º–∏–ª–∏—Ü–∏—è, , m ≤…™Ààl ≤its…®j…ô) was the name of the police forces in the Soviet Union (until 1991) and in several Eastern Bloc countries (1945‚Äì1992), as well as in the non-aligned SFR Yugoslavia (1945‚Äì1992). The ...

) registers and stamped in this internal passport

An internal passport or a domestic passport is an identity document. Uses for internal passports have included restricting citizens of a subdivided state to employment in their own area (preventing their migration to richer cities or regions), cle ...

s. Undocumented residence anywhere for longer than a few weeks was prohibited.

The USSR had both permanent (''–ø—Ä–æ–ø–∏—Å–∫–∞ –ø–æ –º–µ—Å—Ç—É –∂–∏—Ç–µ–ª—å—Å—Ç–≤–∞'' or ''–ø–æ—Å—Ç–æ—è–Ω–Ω–∞—è –ø—Ä–æ–ø–∏—Å–∫–∞'') and temporary (''–≤—Ä–µ–º–µ–Ω–Ω–∞—è –ø—Ä–æ–ø–∏—Å–∫–∞'') propiskas. A third, intermediate type, the employment propiska (''—Å–ª—É–∂–µ–±–Ω–∞—è –ø—Ä–æ–ø–∏—Å–∫–∞''), permitted a person and his or her family to live in an apartment built by an economic entity (factory, ministry) as long as the person worked for the owner of the housing (similar to inclusion of house rent into a labour contract). In the transition period to a market economy in the aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union

The dissolution of the Soviet Union, also negatively connoted as rus, –Ý–∞–∑–≤–∞ÃÅ–ª –°–æ–≤–µÃÅ—Ç—Å–∫–æ–≥–æ –°–æ—éÃÅ–∑–∞, r=Razv√°l Sov√©tskogo Soy√∫za, ''Ruining of the Soviet Union''. was the process of internal disintegration within the Sov ...

in late 1991, the ''permanent propiska'' in municipal apartments was one factor leading to the emergence of private-property rights during privatization

Privatization (also privatisation in British English) can mean several different things, most commonly referring to moving something from the public sector into the private sector. It is also sometimes used as a synonym for deregulation when ...

(those who built housing at their own expense obtained a ''permanent propiska'' there by definition).

Etymology

The Russian verb ''прописа́ть'' (''propisát'') is formed by adding the prefix ''про~'' (''pro~'') to the verb ''писа́ть'' ("to scribe, to write"). Here this prefix emphasizes the completion of the action, which supposes permission (like in ''пусти́ть'' "let o, ''пропусти́ть'' "yield he way) or other related formal action (like in ''дать'' "give", ''прода́ть'' "sell"). Originally, the noun ''propiska'' meant the clerical procedure of ''registration'', of enrolling the person (writing his or her name) into the police records of the local population (or writing down the police permission into the person's identification document - see below). Dahl's Explanatory Dictionary describes this procedure as "to enroll he documentin a book and stamp it". Page 20 of the internal passport of the Russian Empire (see illustration) was entitled ''Место для пропи́ски ви́довъ поли́цiею'' ("Space for registration of ''vid''s by police"). Five blank pages (20 to 24) were gradually filled with stamps with the residential address written in. It allowed a person to reside in his/her relevant locality. Article 61 of the Regulations adopted on February 7, 1897 (see p. 18–19 of the passport) imposed a fine for those found outside the administrative unit (as a rule,

Originally, the noun ''propiska'' meant the clerical procedure of ''registration'', of enrolling the person (writing his or her name) into the police records of the local population (or writing down the police permission into the person's identification document - see below). Dahl's Explanatory Dictionary describes this procedure as "to enroll he documentin a book and stamp it". Page 20 of the internal passport of the Russian Empire (see illustration) was entitled ''Место для пропи́ски ви́довъ поли́цiею'' ("Space for registration of ''vid''s by police"). Five blank pages (20 to 24) were gradually filled with stamps with the residential address written in. It allowed a person to reside in his/her relevant locality. Article 61 of the Regulations adopted on February 7, 1897 (see p. 18–19 of the passport) imposed a fine for those found outside the administrative unit (as a rule, uezd

An uezd (also spelled uyezd; rus, —É–µÃÅ–∑–¥, p= äÀàjest), or povit in a Ukrainian context ( uk, –ø–æ–≤—ñ—Ç), or Kreis in Baltic-German context, was a type of administrative subdivision of the Grand Duchy of Moscow, the Russian Empire, and the ea ...

) in which they were registered to live.

As a clerical term, the noun ''вид'' (''vid'') is short for ''вид на жи́тельство'' (''vid na žítel'stvo''). Although translated into English as a "residential ''permit''", in Russian, this combination of words also conveys a presence of the right of a resident to live somewhere. In the sense of a "egal Egal or Égal may refer to:

People

* Ali Sugule Egal (1936–2016), Somali composer, poet and playwright

* Fabienne Égal (born 1954), French announcer and television host

* Liban Abdi Egal, Somali entrepreneur

* Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal (1928– ...

right" the word ''vid'' also appears in the phrase ''–∏–º–µ—Ç—å –Ω–∞ –Ω–µ—ë –≤–∏–¥—ã'' (''imet' na nejo vidy'', "planning to gain husband's rights with her"). Among many explanations of ''–≤–∏–¥'', Dahl's Explanatory Dictionary indicates a "certificate of any kind for free passage, travel and living", mentioning "passport" as its synonym.

Propiska stamps (handwritten texts as an exception) in the passports of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

used one of two verbs to describe the civil act committed: ''яви́ть'' (''yavít'') "to present", or ''заяви́ть'' (''zayavít'') "to claim". Their non-reflexive form (no postfix ''~ся'') clearly rules out the binding of this act to the owner of the document, so it is not the person who appeared (''presented'' himself) in a police department but the passport itself. Vladimir Dahl mentions both verbs in his description of "propiska" procedure as related to passport. Presenting a passport to the officer implied the claim of a person to stay at a designated location.

History

The origin of the ''propiska'' dates back to whenPeter the Great

Peter I ( ‚Äì ), most commonly known as Peter the Great,) or Pyotr Aleks√©yevich ( rus, –ü—ë—Ç—Ä –ê–ª–µ–∫—Å–µÃÅ–µ–≤–∏—á, p=Ààp ≤…µtr …êl ≤…™Ààks ≤ej…™v ≤…™t…ï, , group=pron was a Russian monarch who ruled the Tsardom of Russia from t ...

wanted to ensure "that sers stayed in the fields where they belonged."

In the pre-Soviet Russian Empire, a person arriving for a new residency was obliged (depending on the estate) to enroll in the registers of the local police authorities. The latter could deny undesirable persons the right to settle (in this case, no stamps were made in passports). In most cases, this would mean the person had to return to their permanent domicile. The verb "propisat" was used as a transitive verb with "vid" being the direct object.

After the reintroduction of the passport system in the Soviet Union in the 1930s, the noun ''propiska'' was also associated with the result of residential registration. In common speech, the stamp in the passport into which the residential address was written was also called "propiska". ''Permanent propiska'' (russian: link=no, "постоя́нная пропи́ска") confirmed the housing rights of its owner. ''Temporary propiska'' (russian: link=no, "вре́менная пропи́ска") could be provided alongside a permanent one when a resident had to live outside the permanent residence for a long period of time. As an example, students and workers leaving to study or work in other cities received ''temporary propiskas'' at their dorms, apartments, or hostels.

When reintroduced in the 1930s, the passport system in the USSR was similar to that of the Russian Empire where passports were required mainly in the largest cities and in the territories adjacent to the country's external borders. Officers and soldiers always had special identity documents, while peasants could obtain internal passports only by a special application. In the USSR, the term ''residential permit'' (russian: link=no, Вид на жи́тельство, lit=, translit=vid na zhitelstvo, italic=yes) was used as a synonym for ''temporary propiska'', particularly with regard to foreign nationals. By the end of the 1980s, when emigrants from the USSR could return, those who had lost Soviet citizenship could also apply for an identity document with this title. The "passportization" of the citizen of the USSR reached its all-encompassing scope only in the 1970s: the right (and obligation) of every adult (from 16) to have a passport promoted the propiska as the primary lever of the regulation of migration. On the other hand, the propiska underlined the mechanism of the constitutional obligation of the state to provide everyone a dwelling: no one could be stripped of the propiska at one location without substitution with another ''permanent propiska'' location, even amidst the then-rarely-granted right to emigrate.

All employers were strictly forbidden to give jobs to anybody without a local "propiska". To hire additional employees, the largest enterprises had to build housing for their staff beforehand. While some built dormitories, others made conventional apartment blocks for individual resettlement. Registration in these apartments was called a ''"work-related" residency permit'' (russian: link=no, "ве́домственная" or "служе́бная" пропи́ска, translit="vedomstvennaya" or "sluzhebnaya" propiska). The lack of free movement resulted in poor housing allocation. Adding an additional layer of bureaucracy stopped efficient movement of labor, because people couldn't move in with family in areas where work was in demand and extra housing lay dormant in towns where people with work related residency permits were moving from.

Implementation

The limit system for migrant workers

The system of a propiska limit existed in the last 30 or so years of the USSR. This was the only means by which outsiders could settle in big cities like Moscow and Leningrad, except marriage. This meant that enterprises in large cities builthostel

A hostel is a form of low-cost, short-term shared sociable lodging where guests can rent a bed, usually a bunk bed in a dormitory, with shared use of a lounge and sometimes a kitchen. Rooms can be mixed or single-sex and have private or share ...

s with dormitories at their own expense, to provide accommodation (with "vedomstvennaya propiska") for migrant workers from smaller towns and rural areas. After long-term employment at an enterprise (around 20 years), a worker could be given an apartment (as opposed to an individual hostel room, which often shared a single bathroom and kitchen per floor and was ill-suited for family life), with permanent "propiska" rights to it. Millions of people were using this system.

The system was introduced with the aim of social fairness in the allocation of housing which was in very short supply, and in a way replaced the Western system of mortgage

A mortgage loan or simply mortgage (), in civil law jurisdicions known also as a hypothec loan, is a loan used either by purchasers of real property to raise funds to buy real estate, or by existing property owners to raise funds for any ...

(except that years of working at the person's workplace were used instead of money). Nevertheless, conditions in these hostels were often poor, worsened by the mandatory security outposts on the hostels' entrance, who would disallow any non-dwellers (without proper documents) to the hostel. While reducing the chances of the hostel being used for criminal purposes, it was a major hindrance for relations with the opposite sex and for planning, starting, and raising a family. There was usually no official gender segregation in the hostels, but since many jobs and student specialities were and are gender-imbalanced (the future teacher was usually female, and the future engineer, more or less usually male, with nearly exclusively males in all military schools), there was often ''de facto'' gender segregation in the hostels.

Students from rural areas or smaller towns lived in very similar hostels, with the termination of right of abode in the hostel on graduation or on exclusion from their schools. The native populations of large cities like Moscow often despised these migrant workers ('limit-dwellers'), considering them rude, uncultured, and violent. The derogatory term "limita" (limit-scum) was used to refer to them.

Details of propiska

The verb "propisat" was used with both the passport and its owner as a direct object. Reciprocally, "propiska" became an object which one can ''have'', e.g.: "to have a propiska in Moscow" (russian: link=no, име́ть пропи́ску в Москве́, translit=). The ''propiska'' was recorded both in theinternal passport

An internal passport or a domestic passport is an identity document. Uses for internal passports have included restricting citizens of a subdivided state to employment in their own area (preventing their migration to richer cities or regions), cle ...

of a Soviet citizen and at local governmental offices. In cities it was a local office of a utility organisation, such as –Ý–≠–£ (District Production Department), –ñ–≠–ö (Housing Committee Office), or –ñ–°–ö (Housing and Construction Cooperative). The passports were stamped at the local police precinct's Ministry of Internal Affairs

An interior ministry (sometimes called a ministry of internal affairs or ministry of home affairs) is a government department that is responsible for internal affairs.

Lists of current ministries of internal affairs

Named "ministry"

* Ministry ...

(MVD) office, with the Military Comissariat (the draft body) also involved. In rural areas, it was a selsoviet

Selsoviet ( be, —Å–µ–ª—å—Å–∞–≤–µ—Ç, r=sieƒ∫saviet, tr. ''sieƒ∫saviet''; rus, —Å–µ–ª—å—Å–æ–≤–µ—Ç, p=Ààs ≤el ≤s…êÀàv ≤…õt, r=selsovet; uk, —Å—ñ–ª—å—Ä–∞–¥–∞, silrada) is a shortened name for a rural council and for the area governed by such a cou ...

, or "village council", a governing body of a rural territory. A propiska could be permanent or temporary. The administrations of hostels, student dormitories, and landlords (very rare case in the USSR, since the "sanitary norm" (a minimum of per person, see below for further details) would usually cause rejection of temporary propiska for such a person) were obliged to maintain temporary propiska records of their guests. The ''propiska'' played the role of both residence permit and resident registration of a person.

Acquiring a propiska to move to a large city, especially Moscow, was extremely difficult for migrants and was a matter of prestige. Even moving to live with relatives did not automatically provide a person with a permanent propiska because of a minimum area limit () for each resident of a specific apartment.

Owing to Soviet property regulations (officially based on the Universal Right to Housing for all), the permanent propiska (which provided the permanent right to dwell in this housing) was nearly impossible for authorities to terminate. The only major exception was a second criminal sentence (after serving the penalty for the first sentence, the inmate returned to the old permanent propiska). If the authorities needed to rule in a certain case, they might refuse a permanent propiska for an individual, but usually not revoking the existing permanent propiska. This also resulted in a situation in which if a spouse agreed (at marriage) to provide the marriage partner with permanent propiska at their apartment, the propiska could not be terminated by divorce, and so exchanging the apartment for two smaller ones was often the only possibility.

Sanitary norm

Spouses could always provide one another a permanent propiska, but explicit consent was required for this. Children were granted a permanent propiska at one of the parents' permanent propiska locations, and this could not be terminated during the lifetime of the child even as an adult (with the exception of a second criminal sentence), unless the grown-up child voluntarily relocated to another place (and was granted a permanent propiska there). It was not this easy for any other relatives. For such cases, as also for any unrelated people, the so-called "sanitary norm" was used: a propiska would not be issued if it would cause the apartment area to fall below per person. Also, the number of rooms in the apartment was important: two persons of different gender, one or both being 9 years or older, were forbidden to share a single room. If the new "propiska" of the new dweller violated this rule, the propiska would not be granted (spouses being an exception). This was officially meant to prevent unhealthy overcrowding of apartments and sexual abuse, but since most Soviet people had only a little over per person, it was also an effective method of migration control. These norms were very similar to getting onto the governmental (not dependent on particular employer) "housing list", which was yet another Soviet form of mortgage (again with real money replaced by years of working at one's workplace—the queue was free in terms of money). The main difference was that to gain admission to the housing list the space had to fall below the required per person in an existing apartment (and, due to the dwelling-area rule already mentioned, children of different gender also raised the chances of getting to the queue). This housing list was very slow (much slower than employers' list), and sometimes it took a person's whole life to get an apartment. As a result, practically the only way for a person legally to improve their living conditions was marriage or childbirth. This was also a serious driving force in migration of young people to " monocities", the new cities built from scratch, often in Siberia or the Arctic, some around a single facility (factory, oil region, or the like).Housing property rights and mortgage: pre/post Soviet

In 1993, after the collapse of the Soviet Union in December 1991, propiska was restructured as resident registration, so the modern Russian legislation does not use the terms "propiska" and "propisat" (with the exception of situations where a reference is needed for the Soviet period). However, it is still used as a colloquial abbreviation for ''permanent residency registration''. In the USSR, there had been some so-called "cooperative" apartments, owned on a Western-style mortgage basis, but they were scarce and getting one was very difficult. The three major post-Soviet reforms, to "not show ethnic background" on this still-vital document, private ownership (something previously disallowed), and seemingly free movement, being "able to register to live anywhere, once they arrange a written lease or buy a house" also ended the situation where these were the only apartments which passed down to children by inheritance. In normal apartments, when the last dweller died, the apartment was returned to the government: when the grandparents became older, they usually preferred to live separately from their children and grandchildren. This was usually connected to cheating of the propiska system: the grandparents were registered not for the apartment in which they lived but the apartment of their children, to avoid the return of their apartment to the government after their death. Violations of the ''propiska'' system within a single city/town were rarely actually punished. Also, Moscow employers were allowed to employ people from the vicinity of Moscow living in a given radius (around ) from Moscow. In theory, it was possible to exchange apartments over mutual agreement between parties. Few people wanted to move from a large city to a smaller one, even with additional money, but the exchange of two flats for one in a larger city was sometimes possible. Also, apartment exchange with money involved was something of a "gray area" bordering on a criminal offence, and there was a real possibility that the participants would be prosecuted as for an economic crime, and real estate agents arranging such things were strictly outlawed and prosecuted, living in a "gray area" and hiding their activities from the authorities. Many people used subterfuge to get a Moscow ''propiska'', includingmarriages of convenience

A marriage of convenience is a marriage contracted for reasons other than that of love and commitment. Instead, such a marriage is entered into for personal gain, or some other sort of strategic purpose, such as a political marriage. There are ...

and bribery. Another way of obtaining Moscow residency was to become a '' limitchik'': to enter Moscow to take certain understaffed job positions, such as at cleaning services, according to a certain workforce quota (''limit''). Such people were provided with a permanent living place (usually a flat or a room in a shared flat) for free, in exchange for working for a certain number of years. Some valuable specialists, such as scientists or engineers, could also be invited by enterprises, which provided them with flats at the expense of the enterprise.

At a certain period, residents of rural areas had their passports stored at selsoviet

Selsoviet ( be, —Å–µ–ª—å—Å–∞–≤–µ—Ç, r=sieƒ∫saviet, tr. ''sieƒ∫saviet''; rus, —Å–µ–ª—å—Å–æ–≤–µ—Ç, p=Ààs ≤el ≤s…êÀàv ≤…õt, r=selsovet; uk, —Å—ñ–ª—å—Ä–∞–¥–∞, silrada) is a shortened name for a rural council and for the area governed by such a cou ...

s (officially "for safekeeping") which prevented them from unofficial migration to the areas where they did not have apartments. This was intended to prevent cities from having an influx of migrants who sought higher living standards in large cities but had permanent registration far away from their actual place of residence.

Propiska fee in Moscow

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, just before the collapse of the USSR, the authorities in Moscow introduced an official charge to be permanently registered in Moscow even in their own property. The fee was around US$5,000, around a quarter of the price of a small apartment at that time. This system lasted several years, causing major public uproar from human rights activists and other liberals, and was abolished after several rulings of the Russian Constitutional Court, the last one in late 1997.Propiska and education

Students not of the city in question were provided a temporary propiska in the dormitories of their university campuses (generally, dormitory space was not provided to students studying in the same city as their parents' residence, but they often wanted it to be free from their parents). After graduation or leaving school early (expulsion, withdrawal, etc.), this temporary propiska was terminated. In Soviet times, this was connected to a "distribution" system which was a mandatory official allocation of a first job placement for university graduates (even from the same city), where they had to work for around 2 years "to pay back the cost of their education". Only postgraduates were exempted from this requirement. This system was despised as being a violation of freedom, since nobody wanted to relocate from a larger city to a smaller one, but it still provided at least a propiska (and the dwelling space connected to it) to a graduate. Also, a "young specialist" could nearly never be fired, the same as a pregnant woman and other specific (in terms of labor laws) categories of people who were entitled to such benefits. After the end of the USSR, the distribution system was almost immediately abolished, leaving graduates with the choice of returning to their home town/village, to their parents or other relatives or struggling to find work in the large city where the school was located. To do the latter, some people became "propiska hunters", i.e. people marrying anybody with permanent propiska in a large city, just to retain their legal right to stay there after graduation. Since, once provided the permanent propiska was not revocable, the natives of the large city were very suspicious about senior-age students from smaller towns or villages when it came to marriage.Modern usage

collapse of the Soviet Union

The dissolution of the Soviet Union, also negatively connoted as rus, –Ý–∞–∑–≤–∞ÃÅ–ª –°–æ–≤–µÃÅ—Ç—Å–∫–æ–≥–æ –°–æ—éÃÅ–∑–∞, r=Razv√°l Sov√©tskogo Soy√∫za, ''Ruining of the Soviet Union''. was the process of internal disintegration within the Sov ...

, the ''propiska'' system was officially abolished. The Russian Supreme Court has ruled the propiska to be unconstitutional on several occasions since the fall of communism and it is considered by human rights organizations to be in direct violation of the Russian constitution, which guarantees freedom of movement. Several former Soviet republics

The Republics of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics or the Union Republics ( rus, –°–æ—éÃÅ–∑–Ω—ã–µ –Ý–µ—Å–ø—ÉÃÅ–±–ª–∏–∫–∏, r=Soy√∫znye Resp√∫bliki) were national-based administrative units of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics ( ...

, such as Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, –Ý–µ—Å–ø—É–±–ª–∏–∫–∞ –ë–µ–ª–∞—Ä—É—Å—å, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by ...

, Ukraine, Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan,, pronounced or the Kyrgyz Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Asia. Kyrgyzstan is bordered by Kazakhstan to the north, Uzbekistan to the west, Tajikistan to the south, and the People's Republic of China to the ea ...

, and Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

, chose to keep their ''propiska'' systems, or at least a scaled-down version of them.

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

changed ''propiska'' to ''registration

Register or registration may refer to:

Arts entertainment, and media Music

* Register (music), the relative "height" or range of a note, melody, part, instrument, etc.

* ''Register'', a 2017 album by Travis Miller

* Registration (organ), th ...

'', though the word ''propiska'' is still widely used to refer to it colloquially. Citizens must register if they live in the same place for 90 days (Belarusian citizens in Russia and vice versa, 30 days). There are two types of registration, permanent and temporary. A place of permanent registration is indicated on a stamp made in an internal passport

An internal passport or a domestic passport is an identity document. Uses for internal passports have included restricting citizens of a subdivided state to employment in their own area (preventing their migration to richer cities or regions), cle ...

, and a place of temporary registration is written on a separate paper. Living in a dwelling without a permanent or temporary registration is considered an administrative offence.

Registration is used for economic, law enforcement and other purposes, such as accounting for social benefits, housing and utility payments, taxes, conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to Ancient history, antiquity and it continues in some countries to th ...

, and medical care.

Today, registration plays little role in questions of property. In Soviet times, for example, if after a marriage, a wife was registered in accommodation her husband rented from the state, in case of divorce, she could obtain some part of her husband's place of residence for her own usage. In modern Russia, this was mostly abandoned due to apartment privatisation, but if a person has no other place to live, he still cannot be evicted without substitution, acting as a powerful deterrent for registering others on their property title.

At the same time, many documents and rights may be obtained only at the place where a citizen has permanent registration, which causes problems, for example, with obtaining or changing passports, voting, obtaining inquiry papers, which are often needed in Russia. Unfortunately, officials tend to ignore laws that allow people to obtain such things and rights if they exist.

For foreigners, registration is called "migration control" and is stamped on a migration card Migration card (russian: –ú–∏–≥—Ä–∞—Ü–∏–æ–Ω–Ω–∞—è –∫–∞—Ä—Ç–∞) is an identity document in the Union State of Russia and Belarus for foreign nationals. Originally they were bilingual (Russian/English), but were changed into Russian-only. The responses ...

and/or coupon, approximately one third the size of an A4 paper, which must be returned to officials before departure.

Migration control is much stricter than internal registration. For instance, to employ any Russian citizen, even with the permanent registration out of the city in question, the employer needs no special permit; only the employee must be registered.

Employing unregistered people is an administrative offence for the employer, but penalties are rare: sometimes even Western companies in Moscow employ unregistered people (usually university graduates who have lost their dormitory registration due to graduation). The penalty is much stricter in the case of foreigners. To employ foreigners, employers must have a permit from the Federal Migration Service.

Belarusian citizens have the same employment rights as Russian citizens in Russia.

In Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inva ...

, the Constitutional Court

A constitutional court is a high court that deals primarily with constitutional law. Its main authority is to rule on whether laws that are challenged are in fact unconstitutional, i.e. whether they conflict with constitutionally established ...

ruled that ''propiska'' was unconstitutional in 2001 (November 14) and a new "informational" registration mechanism was planned by the government, though it never came to fruition. Additionally, access to social benefits such as housing, pensions, medical care, and schooling are still based on a ''propiska'' as are the location for a driving test and the associated lessons.

In Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan (, ; uz, Ozbekiston, italic=yes / , ; russian: –£–∑–±–µ–∫–∏—Å—Ç–∞–Ω), officially the Republic of Uzbekistan ( uz, Ozbekiston Respublikasi, italic=yes / ; russian: –Ý–µ—Å–ø—É–±–ª–∏–∫–∞ –£–∑–±–µ–∫–∏—Å—Ç–∞–Ω), is a doubly landlocked co ...

, even though citizens are issued a single passport, severe restrictions on movement within the country apply, particularly in the capital Tashkent

Tashkent (, uz, Toshkent, –¢–æ—à–∫–µ–Ω—Ç/, ) (from russian: –¢–∞—à–∫–µ–Ω—Ç), or Toshkent (; ), also historically known as Chach is the capital and largest city of Uzbekistan. It is the most populous city in Central Asia, with a population of 2 ...

. After the 1999 Tashkent bombings

The 1999 Tashkent bombings occurred on 16 February when six car bombs exploded in Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan. The bombs exploded over the course of an hour and a half, and targeted multiple government buildings. It is possible that five o ...

, the former Soviet era restrictions were reimposed, making it virtually impossible to acquire propiska in Tashkent.

See also

*Eastern Bloc emigration and defection

After World War II, emigration restrictions were imposed by countries in the Eastern Bloc, which consisted of the Soviet Union and its satellite states in Central and Eastern Europe. Legal emigration was in most cases only possible in order to r ...

* Passport system in the Soviet Union

*Resident registration in Russia

Registration in the Russian Federation is the system that records the residence and internal migration of Russian citizens. The present system was introduced on October 1, 1993, and replaced the prior repressive mandatory Soviet system of '' ...

*Russian passport

The Russian passport (russian: –ó–∞–≥—Ä–∞–Ω–∏—á–Ω—ã–π –ø–∞—Å–ø–æ—Ä—Ç –≥—Ä–∞–∂–¥–∞–Ω–∏–Ω–∞ –Ý–æ—Å—Å–∏–π—Å–∫–æ–π –§–µ–¥–µ—Ä–∞—Ü–∏–∏, Zagranichnyy pasport grazhdanina Rossiyskoy Federatsii, Transborder passport of a citizen of the Russian Federati ...

* 101st km

*Hukou system

''Hukou'' () is a system of household registration used in mainland China. The system itself is more properly called "''huji''" (), and has origins in ancient China; ''hukou'' is the registration of an individual in the system (''kou'' lit ...

References

{{ReflistExternal links

Constitutional Court strikes down internal passport system

Äîarticle in ''

The Ukrainian Weekly

''The Ukrainian Weekly'' is the oldest English-language newspaper of the Ukrainian diaspora in the United States, and North America.

Founded by the Ukrainian National Association, and published continuously since October 6, 1933, archived copies ...

''

Russian ombudsman on propiska in modern Russia

Civil registries Soviet law Soviet internal politics Identity documents of the Soviet Union