Profumo Affair on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Profumo affair was a major scandal in twentieth-century British politics. John Profumo, the

The Profumo affair was a major scandal in twentieth-century British politics. John Profumo, the

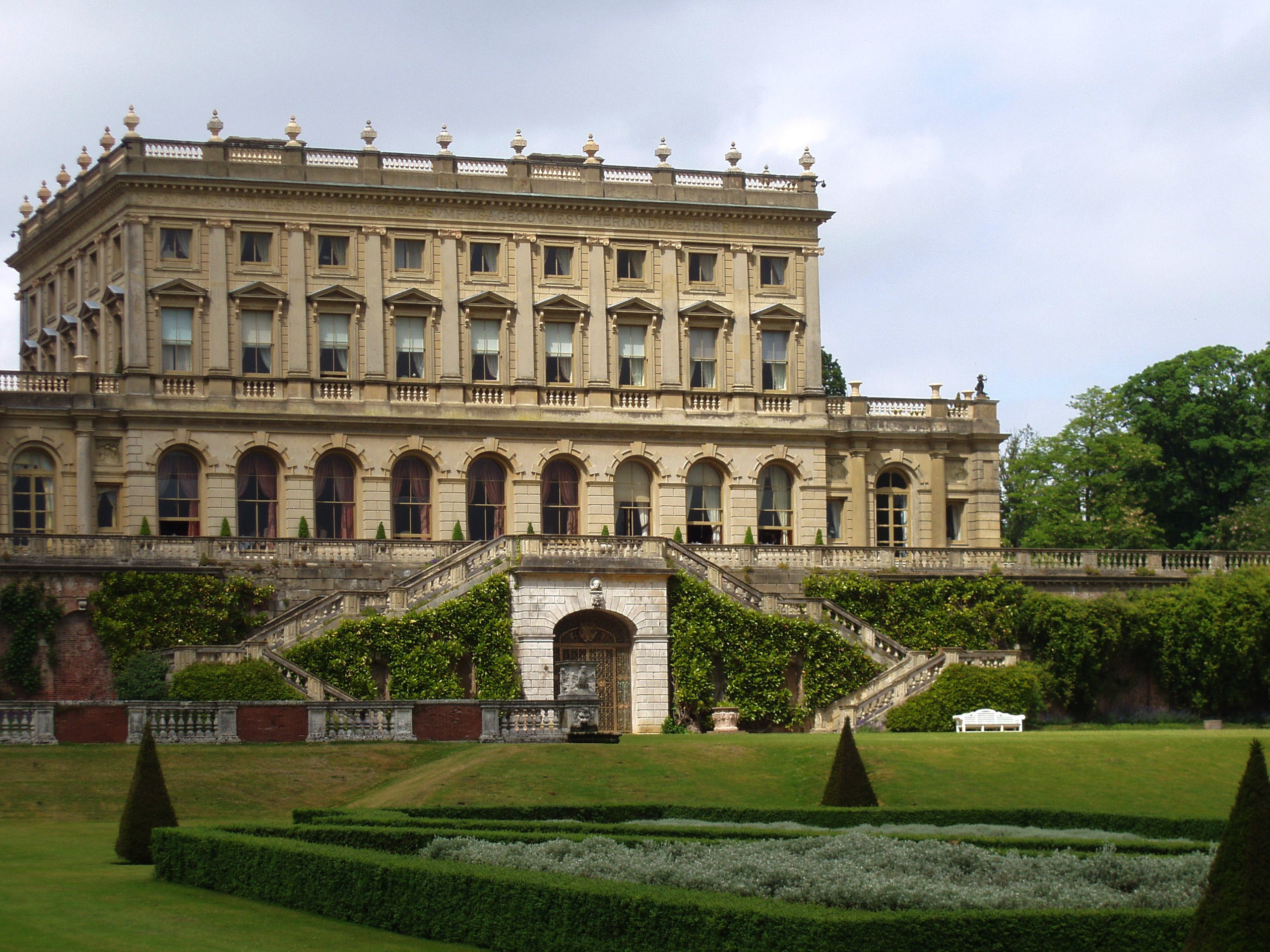

During the weekend of 8–9 July 1961, Keeler was among several guests of Ward at the Spring Cottage at Cliveden. That same weekend, at the main house, Profumo and his wife Valerie were among the large gathering from the worlds of politics and the arts which Astor was hosting in honour of

During the weekend of 8–9 July 1961, Keeler was among several guests of Ward at the Spring Cottage at Cliveden. That same weekend, at the main house, Profumo and his wife Valerie were among the large gathering from the worlds of politics and the arts which Astor was hosting in honour of

In October 1961 Keeler accompanied Ward to Notting Hill, then a run-down district of London replete with West Indian music clubs and

In October 1961 Keeler accompanied Ward to Notting Hill, then a run-down district of London replete with West Indian music clubs and

After expressing his "deep remorse" to the prime minister, to his constituents and to the Conservative Party, Profumo disappeared from public view. In April 1964 he began working as a volunteer at the Toynbee Hall settlement, a charitable organisation based in Spitalfields which supports the most deprived residents in the

After expressing his "deep remorse" to the prime minister, to his constituents and to the Conservative Party, Profumo disappeared from public view. In April 1964 he began working as a volunteer at the Toynbee Hall settlement, a charitable organisation based in Spitalfields which supports the most deprived residents in the

There have been several dramatised versions of the Profumo affair. The 1989 film '' Scandal'' featured Ian McKellen as Profumo and John Hurt as Ward. It was favourably reviewed, but the revival of interest in the affair upset the Profumo family. The focus of Hugh Whitemore's play ''A Letter of Resignation'', first staged at the Comedy Theatre in October 1997, was Macmillan's reactions to Profumo's resignation letter, which he received while on holiday in Scotland. The ITV series '' Endeavour'' pilot episode makes reference to the affair and used elements of the affair as similar plot devices in the 2011 pilot episode. Andrew Lloyd Webber's musical '' Stephen Ward'' opened at London's Aldwych Theatre on 3 December 2013. Among generally favourable reviews, the ''Daily Telegraph''s critic recommended the production as "sharp, funny – and, at times, genuinely touching". Robertson records that the script is "remarkably faithful to the facts".Robertson, p. 168 In his song, " We Didn't Start the Fire", Billy Joel refers to the scandal with the line "British politician sex". Scottish folk musician Al Stewart also refers to the scandal in his song "Post World War II Blues" on the album Past Present Future.

There have been several dramatised versions of the Profumo affair. The 1989 film '' Scandal'' featured Ian McKellen as Profumo and John Hurt as Ward. It was favourably reviewed, but the revival of interest in the affair upset the Profumo family. The focus of Hugh Whitemore's play ''A Letter of Resignation'', first staged at the Comedy Theatre in October 1997, was Macmillan's reactions to Profumo's resignation letter, which he received while on holiday in Scotland. The ITV series '' Endeavour'' pilot episode makes reference to the affair and used elements of the affair as similar plot devices in the 2011 pilot episode. Andrew Lloyd Webber's musical '' Stephen Ward'' opened at London's Aldwych Theatre on 3 December 2013. Among generally favourable reviews, the ''Daily Telegraph''s critic recommended the production as "sharp, funny – and, at times, genuinely touching". Robertson records that the script is "remarkably faithful to the facts".Robertson, p. 168 In his song, " We Didn't Start the Fire", Billy Joel refers to the scandal with the line "British politician sex". Scottish folk musician Al Stewart also refers to the scandal in his song "Post World War II Blues" on the album Past Present Future.

1963 Denning Report – Parliament & the 1960s UK Parliament Living Heritage

* {{Harold Macmillan Espionage scandals and incidents Political sex scandals in the United Kingdom Conservative Party (UK) scandals Soviet Union–United Kingdom relations 1963 in the United Kingdom 1963 in international relations 1963 in British politics

The Profumo affair was a major scandal in twentieth-century British politics. John Profumo, the

The Profumo affair was a major scandal in twentieth-century British politics. John Profumo, the Secretary of State for War

The Secretary of State for War, commonly called War Secretary, was a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, which existed from 1794 to 1801 and from 1854 to 1964. The Secretary of State for War headed the War Office and ...

in Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton, (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986) was a British Conservative statesman and politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. Caricatured as " Supermac", ...

's Conservative government, had an extramarital affair

An affair is a sexual relationship, romantic friendship, or passionate attachment in which at least one of its participants has a formal or informal commitment to a third person who may neither agree to such relationship nor even be aware of ...

with 19-year-old model Christine Keeler

Christine Margaret Keeler (22 February 1942 – 4 December 2017) was an English model and showgirl. Her meeting at a dance club with society osteopath Stephen Ward drew her into fashionable circles. At the height of the Cold War, she became s ...

beginning in 1961. Profumo denied the affair in a statement to the House of Commons, but weeks later a police investigation exposed the truth, proving that Profumo had lied to the House of Commons. The scandal severely damaged the credibility of Macmillan's government, and Macmillan resigned as Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

in October 1963, citing ill health. Ultimately, the fallout contributed to the Conservative government's defeat by the Labour Party in the 1964 general election.

When the Profumo affair was first revealed, public interest was heightened by reports that Keeler may have been simultaneously involved with Captain Yevgeny Ivanov, a Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

naval attaché, thereby creating a possible national security

National security, or national defence, is the security and defence of a sovereign state, including its citizens, economy, and institutions, which is regarded as a duty of government. Originally conceived as protection against military att ...

risk. Keeler knew both Profumo and Ivanov through her friendship with Stephen Ward, an osteopath and socialite who had taken her under his wing. The exposure of the affair generated rumours of other sex scandals and drew official attention to the activities of Ward, who was charged with a series of immorality offences. Perceiving himself as a scapegoat for the misdeeds of others, Ward took a fatal overdose during the final stages of his trial, which found him guilty of living off the immoral earnings of Keeler and her friend Mandy Rice-Davies.

An inquiry into the Profumo affair by a senior judge, Lord Denning

Alfred Thompson "Tom" Denning, Baron Denning (23 January 1899 – 5 March 1999) was an English lawyer and judge. He was called to the bar of England and Wales in 1923 and became a King's Counsel in 1938. Denning became a judge in 1944 whe ...

, assisted by a senior civil servant, T. A. Critchley, concluded that there had been no breaches of security arising from the Ivanov connection, although Denning's report was later described as superficial and unsatisfactory. Profumo subsequently worked as a volunteer at Toynbee Hall, an East London charitable trust. By 1975 he had been officially rehabilitated, although he did not return to public life. He died, honoured and respected, in 2006. By contrast, Keeler found it difficult to escape the negative image attached to her by press, law, and parliament throughout the scandal. In various, sometimes contradictory, accounts, she challenged Denning's conclusions relating to security issues. Ward's conviction has been described by analysts as an act of establishment revenge, rather than serving justice. In the 2010s the Criminal Cases Review Commission

The Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC) is the statutory body responsible for investigating alleged miscarriages of justice in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. It was established by Section 8 of the Criminal Appeal Act 1995 and ...

reviewed his case, but ultimately decided against referring it to the Court of Appeal. Dramatizations of the Profumo affair have been shown on stage and screen.

Background

Government and press

In the early 1960s, the British news media were dominated by several high-profile spying stories: the breaking of the Portland Spy Ring in 1961, the capture and sentencing of George Blake in the same year and, in 1962, the case of John Vassall, a homosexualAdmiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

clerk who had been blackmail

Blackmail is an act of coercion using the threat of revealing or publicizing either substantially true or false information about a person or people unless certain demands are met. It is often damaging information, and it may be revealed to fa ...

ed into spying by the Soviets

Soviet people ( rus, сове́тский наро́д, r=sovyétsky naród), or citizens of the USSR ( rus, гра́ждане СССР, grázhdanye SSSR), was an umbrella demonym for the population of the Soviet Union.

Nationality policy in ...

. Vassall was subsequently sentenced to 18 years in prison. After suggestions in the press that Vassall had been shielded by his political masters, the responsible minister, Thomas Galbraith, resigned from the government pending inquiries. Galbraith was later exonerated by the Vassall Tribunal, after which judge Lord Radcliffe sent two newspaper journalists to prison for refusing to reveal their sources for sensational and uncorroborated stories about Vassall's private life. The imprisonment severely damaged relations between the press and the Conservative government Conservative or Tory government may refer to:

Canada

In Canadian politics, a Conservative government may refer to the following governments administered by the Conservative Party of Canada or one of its historical predecessors:

* 1st Canadian Min ...

of Prime Minister Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton, (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986) was a British Conservative statesman and politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. Caricatured as " Supermac", ...

; columnist Paul Johnson of the ''New Statesman

The ''New Statesman'' is a British political and cultural magazine published in London. Founded as a weekly review of politics and literature on 12 April 1913, it was at first connected with Sidney and Beatrice Webb and other leading members ...

'' warned: " y Tory minister or MP ... who gets involved in a scandal during the next year or so must expect—I regret to say—the full treatment".

John Profumo

John Profumo was born in 1915 and was of Italian descent. He first enteredParliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

in 1940 as the Conservative member for Kettering

Kettering is a market and industrial town in North Northamptonshire, England. It is located north of London and north-east of Northampton, west of the River Ise, a tributary of the River Nene. The name means "the place (or territory) ...

while serving with the Northamptonshire Yeomanry, and combined his political and military duties through the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

. Profumo lost his seat in the 1945 general election, but was elected again in 1950 for Stratford-on-Avon. From 1951 he held junior ministerial office in successive Conservative administrations. In 1960, Macmillan promoted Profumo to Secretary of State for War

The Secretary of State for War, commonly called War Secretary, was a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, which existed from 1794 to 1801 and from 1854 to 1964. The Secretary of State for War headed the War Office and ...

, a senior post outside the Cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filin ...

. After his marriage in 1954 to Valerie Hobson

Babette Louisa Valerie Hobson (14 April 1917 – 13 November 1998) was a British actress whose film career spanned the 1930s to the early 1950s. Her second husband was John Profumo, a British government minister who became the subject of the Pro ...

, one of Britain's leading film actresses, Profumo may have conducted casual affairs, using late-night parliamentary sittings as his cover. His tenure as war minister coincided with a period of transition in the armed forces, involving the end of conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to Ancient history, antiquity and it continues in some countries to th ...

and the development of a wholly professional army. Profumo's performance was watched with a critical eye by his opposition counterpart George Wigg, a former regular soldier.

Christine Keeler, Mandy Rice-Davies, and Lord Astor

Christine Keeler

Christine Margaret Keeler (22 February 1942 – 4 December 2017) was an English model and showgirl. Her meeting at a dance club with society osteopath Stephen Ward drew her into fashionable circles. At the height of the Cold War, she became s ...

, born in 1942, left school at 15 with no qualifications and took a series of short-lived jobs in shops, offices and cafés. She aspired to be a model, and at 16 had a photograph published in '' Tit-Bits'' magazine. In August 1959, Keeler found work as a topless showgirl at Murray's Cabaret Club

Murray's Cabaret Club was a cabaret club in Beak Street in Soho, central London, England.

History

The club was first opened in 1913 by an American, Jack Mays, and an Englishman, Ernest A. Cordell. The club is known for its scantily-clad showg ...

in Beak Street, Soho

Soho is an area of the City of Westminster, part of the West End of London. Originally a fashionable district for the aristocracy, it has been one of the main entertainment districts in the capital since the 19th century.

The area was deve ...

. This long-established club attracted a distinguished clientele who, Keeler wrote, "could look but could not touch". Shortly after starting at Murray's, Keeler was introduced to a client, the society osteopath Stephen Ward. Captivated by Ward's charm, she agreed to move into his flat, in a relationship she has described as "like brother and sister"—affectionate but not sexual. She left Ward after a few months to become the mistress of the property dealer Peter Rachman, and later shared lodgings with Mandy Rice-Davies, a fellow Murray's dancer two and a half years her junior. The two girls left Murray's and attempted without success to pursue careers as freelance models. Keeler also lived for short periods with various boyfriends, but regularly returned to Ward, who had acquired a house in Wimpole Mews

Wimpole Mews is a mews street in Marylebone, London W1, England. It is known for being a key location in the Profumo affair in the early 1960s.

The street runs north–south, with Weymouth Street to the north and New Cavendish Street to the s ...

, Marylebone

Marylebone (usually , also , ) is a district in the West End of London, in the City of Westminster. Oxford Street, Europe's busiest shopping street, forms its southern boundary.

An ancient parish and latterly a metropolitan borough, it ...

. There she met many of Ward's friends, among them Lord Astor, a long-time patient who was also a political ally of Profumo. She often spent weekends at a riverside cottage that Ward rented on Astor's country estate, Cliveden, in Buckinghamshire

Buckinghamshire (), abbreviated Bucks, is a ceremonial county in South East England that borders Greater London to the south-east, Berkshire to the south, Oxfordshire to the west, Northamptonshire to the north, Bedfordshire to the north-e ...

.

Stephen Ward and Yevgeny Ivanov

Stephen Ward, born inHertfordshire

Hertfordshire ( or ; often abbreviated Herts) is one of the home counties in southern England. It borders Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire to the north, Essex to the east, Greater London to the south, and Buckinghamshire to the west. For gov ...

in 1912, qualified as an osteopath in the United States. After the Second World War he began practising in Cavendish Square

Cavendish Square is a public garden square in Marylebone in the West End of London. It has a double-helix underground commercial car park. Its northern road forms ends of four streets: of Wigmore Street that runs to Portman Square in the much ...

, London, where he rapidly established a good reputation and attracted many distinguished patients. These connections, together with his personal charm, brought him considerable social success. In his spare time Ward attended art classes at the Slade school, and developed a profitable sideline in portrait sketches. In 1960 he was commissioned by '' The Illustrated London News'' to provide a series of portraits of national and international figures. These included members of the Royal Family

A royal family is the immediate family of kings/queens, emirs/emiras, sultans/ sultanas, or raja/ rani and sometimes their extended family. The term imperial family appropriately describes the family of an emperor or empress, and the term pa ...

, among them Prince Philip and Princess Margaret.

Ward hoped to visit the Soviet Union to draw portraits of Russian leaders. To help him, one of his patients, the ''Daily Telegraph

Daily or The Daily may refer to:

Journalism

* Daily newspaper, newspaper issued on five to seven day of most weeks

* ''The Daily'' (podcast), a podcast by ''The New York Times''

* ''The Daily'' (News Corporation), a defunct US-based iPad new ...

'' editor Sir Colin Coote, arranged an introduction to Captain Yevgeny Ivanov (anglicised as "Eugene"), listed as a naval attaché at the Soviet Embassy. British Intelligence ( MI5) knew from the double agent Oleg Penkovsky that Ivanov was an intelligence officer in the Soviet GRU. Ward and Ivanov became firm friends. Ivanov frequently visited Ward at Wimpole Mews, where he met Keeler and Rice-Davies, and sometimes joined Ward's weekend parties at Cliveden.Denning, p. 8 MI5 considered Ivanov a potential defector, and sought Ward's help to this end, providing him with a case officer known as "Woods". Ward was later used by the Foreign Office as a backchannel

Backchannel is the use of networked computers to maintain a real-time online conversation alongside the primary group activity or live spoken remarks. The term was coined from the linguistics term to describe listeners' behaviours during verbal ...

, through Ivanov, to the Soviet Union, and was involved in unofficial diplomacy at the time of the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (of 1962) ( es, Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, the Caribbean Crisis () in Russia, or the Missile Scare, was a 35-day (16 October – 20 November 1962) confrontation between the United S ...

. His closeness to Ivanov raised concerns about his loyalty; according to Lord Denning

Alfred Thompson "Tom" Denning, Baron Denning (23 January 1899 – 5 March 1999) was an English lawyer and judge. He was called to the bar of England and Wales in 1923 and became a King's Counsel in 1938. Denning became a judge in 1944 whe ...

's September 1963 report, Ivanov often asked Ward questions about British foreign policy, and Ward did his best to provide answers.

Origins

Cliveden, July 1961

Ayub Khan

Ayub Khan is a compound masculine name; Ayub is the Arabic version of the name of the Biblical figure Job, while Khan or Khaan is taken from the title used first by the Mongol rulers and then, in particular, their Islamic and Persian-influenced s ...

, the president of Pakistan. On the Saturday evening, Ward's and Astor's parties mingled at the Cliveden swimming pool, which Ward and his guests had permission to use. Keeler, who had been swimming naked, was introduced to Profumo while trying to cover herself with a skimpy towel. She was, Profumo informed his son many years later, "a very pretty girl and very sweet". Keeler did not initially know who Profumo was, but was impressed that he was the husband of a famous film star and was prepared to have "a bit of fun" with him.

The next afternoon the two parties reconvened at the pool and were joined by Ivanov, who had arrived that morning. There followed what Lord Denning described as "a light-hearted and frolicsome bathing party, where everyone was in bathing costumes and nothing indecent took place at all". Profumo was greatly attracted to Keeler, and promised to be in touch with her. Ward asked Ivanov to accompany Keeler back to London where, according to Keeler, they had sex. Some commentators doubt this—Keeler was generally outspoken about her sexual relationships, yet said nothing openly about sex with Ivanov until she informed a newspaper eighteen months later.

On 12 July 1961, Ward reported on the weekend's events to MI5. He told Woods that Ivanov and Profumo had met and that the latter had shown considerable interest in Keeler. Ward also stated that he had been asked by Ivanov for information about the future arming of West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 ...

with nuclear weapons. This request for military information did not greatly disturb MI5, who expected a GRU officer to ask such questions. Profumo's interest in Keeler was an unwelcome complication in MI5's plans to use her in a honey trap operation against Ivanov, to help secure his defection. Woods therefore referred the issue to MI5's director-general, Sir Roger Hollis.

Affair

A few days after the Cliveden weekend, Profumo contacted Keeler. The affair that ensued was brief; some commentators have suggested that it ended after a few weeks, while others believe that it continued, with decreasing fervour, until December 1961.Davenport-Hines, pp. 250–53Profumo, pp. 165–66 The relationship was characterised by Keeler as an unromantic relationship without expectations, a "screw of convenience", although she also states that Profumo hoped for a longer-term commitment and that he offered to set her up in a flat. More than twenty years later, Profumo described Keeler in conversation with his son as someone who "seem dto like sexual intercourse", but who was "completely uneducated", with no conversation beyond make-up, hair and gramophone records. The couple usually met at Wimpole Mews, when Ward was absent, although once, when Hobson was away, Profumo took Keeler to his home atChester Terrace

Chester Terrace is one of the neo-classical terraces in Regent's Park, London. The terrace has the longest unbroken facade in Regent's Park, of about . It takes its name from one of the titles of George IV before he became king, Earl of Cheste ...

in Regent's Park

Regent's Park (officially The Regent's Park) is one of the Royal Parks of London. It occupies of high ground in north-west Inner London, administratively split between the City of Westminster and the Borough of Camden (and historically betwee ...

. On one occasion he borrowed a Bentley

Bentley Motors Limited is a British designer, manufacturer and marketer of luxury cars and SUVs. Headquartered in Crewe, England, the company was founded as Bentley Motors Limited by W. O. Bentley (1888–1971) in 1919 in Cricklewood, Nort ...

from his ministerial colleague John Hare and took Keeler for a drive around London, and another time the couple had a drink with Viscount Ward, the former Secretary of State for Air. During their time together, Profumo gave Keeler a few small presents, and once, a sum of £20 as a gift for her mother. Keeler maintains that although Stephen Ward asked her to obtain information from Profumo about the deployment of nuclear weapons, she did not do so. Profumo was equally adamant that no such discussions took place.

On 9 August, Profumo was interviewed informally by Sir Norman Brook, the Cabinet Secretary, who had been advised by Hollis of Profumo's involvement with the Stephen Ward circle. Brook warned the minister of the dangers of mixing with Ward's group, since MI5 were at this stage unsure of Ward's dependability. It is possible that Brook asked Profumo to help MI5 in its efforts to secure Ivanov's defection—a request which Profumo declined. Although Brook did not indicate knowledge of Profumo's relationship with Keeler, Profumo may have suspected that he knew. That same day, Profumo wrote Keeler a letter, beginning "Darling ...", cancelling an assignation they had made for the following day. Some commentators have assumed that this letter ended the association;Knightley and Kennedy, pp. 86–89 Keeler insisted that the affair ended later, after her persistent refusals to stop living with Ward.

Developing scandal

Gordon and Edgecombe

In October 1961 Keeler accompanied Ward to Notting Hill, then a run-down district of London replete with West Indian music clubs and

In October 1961 Keeler accompanied Ward to Notting Hill, then a run-down district of London replete with West Indian music clubs and cannabis

''Cannabis'' () is a genus of flowering plants in the family Cannabaceae. The number of species within the genus is disputed. Three species may be recognized: '' Cannabis sativa'', '' C. indica'', and '' C. ruderalis''. Alternative ...

dealers. At the Rio Café they encountered Aloysius "Lucky" Gordon, a Jamaican jazz singer with a history of violence and petty crime. He and Keeler embarked on an affair which, in her own accounts, was marked by equal measures of violence and tenderness on his part. Gordon became very possessive towards Keeler, jealous of her other social contacts. He began confronting her friends, and often telephoned her at unsocial hours. In November Keeler left Wimpole Mews and moved to a flat in Dolphin Square, overlooking the Thames at Pimlico, where she entertained friends. When Gordon continued to harass Keeler he was arrested by the police and charged with assault. Keeler later agreed to drop the charge.

In July 1962 the first inklings of a possible Profumo-Keeler-Ivanov triangle had been hinted, in coded terms, in the gossip column of the society magazine ''Queen

Queen or QUEEN may refer to:

Monarchy

* Queen regnant, a female monarch of a Kingdom

** List of queens regnant

* Queen consort, the wife of a reigning king

* Queen dowager, the widow of a king

* Queen mother, a queen dowager who is the mother ...

''. Under the heading, "Sentences I'd like to hear the end of" appeared the wording: "... called in MI5 because every time the chauffeur-driven Zils drew up at her ''front'' door, out of her ''back'' door into a chauffeur-driven Humber

The Humber is a large tidal estuary on the east coast of Northern England. It is formed at Trent Falls, Faxfleet, by the confluence of the tidal rivers Ouse and Trent. From there to the North Sea, it forms part of the boundary between ...

slipped..."Young, p. 9, quoting from ''Queen'' Keeler was then in New York City with Rice-Davies, in an abortive attempt to launch their modelling careers there. On her return, to counter Gordon's threats, Keeler formed a relationship with Johnny Edgecombe

John Arthur Alexander Edgecombe (22 October 1932 – 26 September 2010) was a British jazz promoter, whose involvement with Christine Keeler inadvertently alerted authorities to the Profumo affair.

Early life

Edgecombe was born on 22 October 19 ...

, an ex-merchant seaman from Antigua, with whom she lived for a while in Brentford

Brentford is a suburban town in West London, England and part of the London Borough of Hounslow. It lies at the confluence of the River Brent and the Thames, west of Charing Cross.

Its economy has diverse company headquarters buildings wh ...

, just west of London.Davenport-Hines, p. 258 Edgecombe became similarly possessive himself after he and Gordon clashed violently on 27 October 1962, when Edgecombe slashed his rival with a knife. Keeler broke up with Edgecombe shortly afterwards because of his domineering behaviour.

On 14 December 1962 Keeler and Rice-Davies were together at 17 Wimpole Mews when Edgecombe arrived, demanding to see Keeler. When he was not allowed in, he fired several shots at the front door. Shortly afterwards, Edgecombe was arrested and charged with attempted murder

Attempted murder is a crime of attempt in various jurisdictions.

Canada

Section 239 of the ''Criminal Code'' makes attempted murder punishable by a maximum of life imprisonment. If a gun is used, the minimum sentence is four, five or seven y ...

and other offences. In brief press accounts, Keeler was described as "a free-lance model" and "Miss Marilyn Davies" as "an actress". In the wake of the incident, Keeler began to talk indiscreetly about Ward, Profumo, Ivanov and the Edgecombe shooting. Among those to whom she told her story was John Lewis, a former Labour MP whom she had met by chance in a night club. Lewis, a long-standing enemy of Ward, passed the information to Wigg, his one-time parliamentary colleague, who began his own investigation.

Mounting pressures

On 22 January 1963 the Soviet government, sensing a possible scandal, recalled Ivanov. Aware of increasing public interest, Keeler attempted to sell her story to the national newspapers.Davenport-Hines, pp. 262–63 The Radcliffe tribunal's ongoing inquiry into press behaviour during the Vassall case was making newspapers nervous, and only two showed interest in Keeler's story: the ''Sunday Pictorial

The ''Sunday Mirror'' is the Sunday sister paper of the ''Daily Mirror''. It began life in 1915 as the ''Sunday Pictorial'' and was renamed the ''Sunday Mirror'' in 1963. In 2016 it had an average weekly circulation of 620,861, dropping marke ...

'' and the ''News of the World

The ''News of the World'' was a weekly national red top tabloid newspaper published every Sunday in the United Kingdom from 1843 to 2011. It was at one time the world's highest-selling English-language newspaper, and at closure still had one ...

''. As the latter would not join an auction, Keeler accepted the ''Pictorial''s offer of a £200 down payment and a further £800 when the story was published. The ''Pictorial'' retained a copy of the "Darling" letter. Meanwhile, the ''News of the World'' alerted Ward and Astor—whose names had been mentioned by Keeler—and they in turn informed Profumo. When Profumo's lawyers tried to persuade Keeler not to publish, the compensation she demanded was so large that they considered charges of extortion

Extortion is the practice of obtaining benefit through coercion. In most jurisdictions it is likely to constitute a criminal offence; the bulk of this article deals with such cases. Robbery is the simplest and most common form of extortion, ...

.Robertson, pp. 34–35 Ward informed the ''Pictorial'' that Keeler's story was largely false, and that he and others would sue if it was printed, whereupon the paper withdrew its offer, although Keeler kept the £200.

Keeler then gave details of her affair with Profumo to a police officer, who did not pass on this information to MI5 or the legal authorities.Parris, p. 159 By this time, many of Profumo's political colleagues had heard rumours of his entanglement, and of the existence of a potentially incriminating letter. Nevertheless, his denials were accepted by the government's principal law officers and the Conservative Chief Whip

The Chief Whip is a political leader whose task is to enforce the whipping system, which aims to ensure that legislators who are members of a political party attend and vote on legislation as the party leadership prescribes.

United Kingdom

...

, although with some private scepticism. Macmillan, mindful of the injustice done to Galbraith on the basis of rumours, was determined to support his minister and took no action.

Edgecombe's trial began on 14 March but Keeler, one of the Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has differ ...

's key witnesses, was missing. She had, without informing the court, gone to Spain, although at this stage her whereabouts were unknown. Keeler's unexplained absence caused a press sensation.Knightley and Kennedy, pp. 149–50 Every newspaper knew the rumours linking Keeler with Profumo, but refrained from reporting any direct connection; in the wake of the Radcliffe inquiry they were, in Wigg's later words, "willing to wound but afraid to strike".Young, pp. 14–15 They could only hint, by front-page juxtapositions of stories and photographs, that Profumo might be connected to Keeler's disappearance. Despite Keeler's absence the judge proceeded with the case; Edgecombe was found guilty on a lesser charge of possessing a firearm with intent to endanger life, and sentenced to seven years' imprisonment. A few days after the trial, on 21 March, the satirical magazine '' Private Eye'' printed the most detailed summary so far of the rumours, with the main characters lightly disguised: "Mr James Montesi", "Miss Gaye Funloving", "Dr Spook" and "Vladimir Bolokhov".

Personal statement

The newly elected leader of the opposition Labour Party,Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, (11 March 1916 – 24 May 1995) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from October 1964 to June 1970, and again from March 1974 to April 1976. He ...

, was initially advised by his colleagues to have nothing to do with Wigg's private dossier on the Profumo rumours. On 21 March, with the press furore over the "missing witness" at its height, the party changed its stance. During a House of Commons debate, Wigg used parliamentary privilege

Parliamentary privilege is a legal immunity enjoyed by members of certain legislatures, in which legislators are granted protection against civil or criminal liability for actions done or statements made in the course of their legislative duties ...

to ask the Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all nationa ...

to categorically deny the truth of rumours connecting "a minister" to Keeler, Rice-Davies and the Edgecombe shooting. He did not name Profumo, who was not in the House. Later in the debate Barbara Castle, the Labour MP for Blackburn, referred to the "missing witness" and hinted at a possible perversion of justice.Irving et al, pp 100–01 The Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all nationa ...

, Henry Brooke, refused to comment, adding that Wigg and Castle should "seek other means of making these insinuations if they are prepared to substantiate them".

At the conclusion of the debate the government's law officers and Chief Whip met, and decided that Profumo should assert his innocence in a personal statement to the House. Such statements are, by long-standing tradition, made on the particular honour of the member and are accepted by the House without question.Young, p. 17 In the early hours of 22 March Profumo and his lawyers met with ministers and together agreed an appropriate wording. Later that morning Profumo made his statement to a crowded House. He acknowledged friendships with Keeler and Ward, the former of whom, he said, he had last seen in December 1961. He had met "a Mr Ivanov" twice, also in 1961. He stated: "There was no impropriety whatsoever in my acquaintanceship with Miss Keeler", and added: "I shall not hesitate to issue writs for libel and slander if scandalous allegations are made or repeated outside the House." That afternoon, Profumo was photographed at Sandown Park Racecourse

Sandown Park is a horse racing course and leisure venue in Esher, Surrey, England, located in the outer suburbs of London. It hosts 5 Grade One National Hunt races and one Group 1 flat race, the Eclipse Stakes. It regularly has horse ...

in the company of the Queen Mother

A queen mother is a former queen, often a queen dowager, who is the mother of the reigning monarch. The term has been used in English since the early 1560s. It arises in hereditary monarchies in Europe and is also used to describe a number of ...

.Davenport-Hines, pp. 276–77

While officially the matter was considered closed, many individual MPs had doubts, although none openly expressed disbelief at this stage. Wigg later said that he left the House that morning "with black rage in my heart because I knew what the facts were. I knew the truth." Most newspapers were editorially non-committal; only ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers '' The Observer'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the ...

'', under the headline "Mr Profumo clears the air", stated openly that the statement should be taken at its face value. Within a few days press attention was distracted by the re-emergence of Keeler in Madrid. She expressed astonishment at the fuss her absence had caused, adding that her friendship with Profumo and his wife was entirely innocent and that she had many friends in important positions. Keeler claimed that she had not deliberately missed the Edgecombe trial but had been confused about the date. She was required to forfeit her recognizance

In some common law nations, a recognizance is a conditional pledge of money undertaken by a person before a court which, if the person defaults, the person or their sureties will forfeit that sum. It is an obligation of record, entered into before ...

of £40, but no other action was taken against her.

Exposure

Investigation and resignation

Shortly after Profumo's Commons statement, Ward appeared on Independent Television News, where he endorsed Profumo's version and dismissed all rumours and insinuations as "baseless". Ward's own activities had become a matter of official concern, and on 1 April 1963 theMetropolitan Police

The Metropolitan Police Service (MPS), formerly and still commonly known as the Metropolitan Police (and informally as the Met Police, the Met, Scotland Yard, or the Yard), is the territorial police force responsible for law enforcement and ...

began to investigate his affairs. They interviewed 140 of Ward's friends, associates and patients, maintained a 24-hour watch on his home, and tapped his telephone—this last action requiring direct authorisation from Brooke.Robertson, pp. 44–45 Among those who gave statements was Keeler, who contradicted her earlier assurances and confirmed her sexual relationship with Profumo, providing corroborative details of the interior of the Chester Terrace house. The police put pressure on reluctant witnesses; Rice-Davies was remanded to HM Prison Holloway

HM Prison Holloway was a closed category prison for adult women and young offenders in Holloway, London, England, operated by His Majesty's Prison Service. It was the largest women's prison in western Europe, until its closure in 2016.

His ...

for a driving licence offence and held there for eight days until she agreed to testify against Ward. Meanwhile, Profumo was awarded costs and £50 damages against the British distributors of an Italian magazine that had printed a story hinting at his guilt. He donated the proceeds to an army charity.

This did not deter ''Private Eye'' from including "Sextus Profano" in their parody of Gibbon's '' Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire''.

On 18 April 1963 Keeler was attacked at the home of a friend. She accused Gordon, who was arrested and held. According to Knightley and Kennedy's account, the police offered to drop the charges if Gordon would testify against Ward, but he refused. The effects of the police inquiry were proving ruinous to Ward, whose practice was collapsing rapidly. On 7 May he met Macmillan's private secretary, Timothy Bligh, to ask that the police inquiry into his affairs be halted. He added that he had been covering for Profumo, whose Commons statement was substantially false. Bligh took notes but failed to take action.Davenport-Hines, pp. 287–89 On 19 May Ward wrote to Brooke, with essentially the same request as that to Bligh, to be told that the Home Secretary had no power to interfere with the police inquiry. Ward then gave details to the press, but no paper would print the story. He also wrote to Wilson, who showed the letter to Macmillan. Although privately disdainful of Wilson's motives, after discussions with Hollis the prime minister was sufficiently concerned about Ward's general activities to ask the Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. Th ...

, Lord Dilhorne, to inquire into possible security breaches.

On 31 May 1963 at the start of the parliamentary Whitsun recess, Profumo and his wife flew to Venice for a short holiday. At their hotel they received a message asking Profumo to return as soon as possible. Believing that his bluff had been called, Profumo then told his wife the truth, and they decided to return immediately. They found that Macmillan was on holiday in Scotland. On Tuesday 4 June, Profumo confessed the truth to Bligh, confirming that he had lied, resigned from the government, and applied for the office of steward of the Chiltern Hundreds in order to give up his House of Commons seat. Bligh informed Macmillan of these events by telephone. The resignation was announced on 5 June, when the formal exchange of letters between Profumo and Macmillan was published.Irving et al, pp. 137–38 ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ( ...

'' called Profumo's lies "a great tragedy for the probity of public life in Britain"; and the ''Daily Mirror

The ''Daily Mirror'' is a British national daily Tabloid journalism, tabloid. Founded in 1903, it is owned by parent company Reach plc. From 1985 to 1987, and from 1997 to 2002, the title on its Masthead (British publishing), masthead was simpl ...

'' hinted that not all the truth had been told, and referred to "skeletons in many cupboards".

Retribution

Gordon's trial for the attack on Keeler began on the day Profumo's resignation was made public. He maintained that his innocence would be established by two witnesses who, the police told the court, could not be found. On 7 June, principally on the evidence of Keeler, Gordon was found guilty and sentenced to three years' imprisonment. The following day, Ward was arrested and charged with immorality offences. On 9 June, freed from Profumo'slibel

Defamation is the act of communicating to a third party false statements about a person, place or thing that results in damage to its reputation. It can be spoken (slander) or written (libel). It constitutes a tort or a crime. The legal defi ...

threats, the ''News of the World'' published "The Confessions of Christine", an account which helped to fashion the public image of Ward as a sexual predator and probable tool of the Soviets.Robertson, pp. 52–55 The ''Sunday Mirror'' (formerly the ''Sunday Pictorial'') printed Profumo's "Darling" letter.

In advance of the House of Commons debate on Profumo's resignation, due 17 June, David Watt in ''The Spectator

''The Spectator'' is a weekly British magazine on politics, culture, and current affairs. It was first published in July 1828, making it the oldest surviving weekly magazine in the world.

It is owned by Frederick Barclay, who also owns ''Th ...

'' defined Macmillan's position as "an intolerable dilemma from which he can only escape by being proved either ludicrously naïve or incompetent or deceitful—or all three". Meanwhile, the press speculated about possible Cabinet resignations, and several ministers felt it necessary to demonstrate their loyalty to the prime minister. In a BBC interview on 13 June Lord Hailsham, holder of several ministerial offices, denounced Profumo in a manner which, according to ''The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. It is a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', whose parent company Guardian Media Group Limited acquired it in 1993. First published in 1791, it is the ...

'', "had to be seen to be believed". Hailsham said that "a great party is not to be brought down because of a squalid affair between a woman of easy virtue and a proven liar".

In the debate, Wilson concentrated almost exclusively on the extent to which Macmillan and his colleagues had been dilatory in not identifying a clear security risk arising from Profumo's association with Ward and his circle. Macmillan responded that he should not be held culpable for believing a colleague who had repeatedly asserted his innocence. He mentioned the false allegations against Galbraith, and the failure of the security services to share their detailed information with him. In the general debate the sexual aspects of the scandal were fully discussed; Nigel Birch, the Conservative MP for West Flintshire, referred to Keeler as a "professional prostitute" and asked rhetorically: "What are whores about?" Keeler was otherwise branded a "tart" and a "poor little slut". Ward was vilified throughout as a likely Soviet agent; one Conservative referred to "the treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

of Dr Ward". Most Conservatives, whatever their reservations, were supportive of Macmillan, with only Birch suggesting that he should consider retirement.Knightley and Kennedy, p. 195 In the subsequent vote on the government's handling of the affair, 27 Conservatives abstained, reducing the government's majority to 69. Most newspapers considered the extent of the defection significant, and several forecast that Macmillan would soon resign.

After the parliamentary debate, newspapers published further sensational stories, hinting at widespread immorality within Britain's governing class. A story emanating from Rice-Davies concerned a naked masked man, who acted as a waiter at sex parties; rumours suggested that he was a cabinet minister, or possibly a member of the Royal Family. Malcolm Muggeridge in the ''Sunday Mirror'' wrote of "The Slow, Sure Death of the Upper Classes". On 21 June Macmillan instructed Lord Denning, the Master of the Rolls, to investigate and report on the growing range of rumours. Ward's committal proceedings began a week later, at Marylebone magistrates' court, where the Crown's evidence was fully reported in the press. Ward was committed for trial on charges of "living off the earnings of prostitution" and "procuration of girl under twenty-one", and released on bail.

With the Ward case now '' sub judice'', the press pursued related stories. '' The People'' reported that Scotland Yard

Scotland Yard (officially New Scotland Yard) is the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police, the territorial police force responsible for policing Greater London's 32 boroughs, but not the City of London, the square mile that forms London's ...

had begun an inquiry, in parallel with Denning's, into "homosexual practices as well as sexual laxity" among civil servants, military officers and MPs. On 24 June the ''Daily Mirror'', under a banner heading "Prince Philip and the Profumo Scandal", dismissed what it termed the "foul rumour" that the prince had been involved in the affair, without disclosing the nature of the rumour.

Ward's trial began at the Old Bailey on 28 July. He was charged with living off the earnings of Keeler, Rice-Davies and two other prostitutes, and with procuring women under 21 to have sex with other persons. The thrust of the prosecution's case related to Keeler and Rice-Davies, and turned on whether the small contributions to household expenses or loan repayments they had given to Ward while living with him amounted to his living off their prostitution. Ward's approximate income at the time, from his practice and from his portraiture, had been around £5,500 a year, a substantial sum at that time. In his speeches and examination of witnesses, the prosecuting counsel Mervyn Griffith-Jones portrayed Ward as representing "the very depths of lechery and depravity". The judge, Sir Archie Marshall, was equally hostile, drawing particular attention to the fact that none of Ward's supposed society friends had been prepared to speak up for him. Towards the end of the trial, news came that Gordon's conviction for assault had been overturned; Marshall did not disclose to the jury that Gordon's witnesses had turned up and testified that Keeler, a key prosecution witness against Ward, had given false evidence at Gordon's trial.

After listening to Marshall's damning summing-up, on the evening of 30 July Ward took an overdose of sleeping tablets and was taken to hospital. On the next day, he was found guilty '' in absentia'' on the charges relating to Keeler and Rice-Davies, and acquitted on the other counts. Sentence was postponed until Ward was fit to appear, but on 3 August he died without regaining consciousness. On 9 August, a coroner's jury ruled Ward's death as suicide by barbiturate

Barbiturates are a class of depressant drugs that are chemically derived from barbituric acid. They are effective when used medically as anxiolytics, hypnotics, and anticonvulsants, but have physical and psychological addiction potential a ...

poisoning, though some biographers consider the possibility that he was murdered.

Aftermath

Lord Denning's report was awaited with great anticipation by the public. Published on 26 September 1963, it concluded that there had been no security leaks in the Profumo affair and that the security services and government ministers had acted appropriately. Profumo had been guilty of an "indiscretion", but no one could doubt his loyalty. Denning also found no evidence to link members of the government with associated scandals such as the "man in the mask". He laid most of the blame for the affair on Ward, an "utterly immoral" man whose diplomatic activities were "misconceived and misdirected". Although ''The Spectator'' considered that the report marked the end of the affair, many commentators were disappointed with its content. Young found many questions unanswered and some of the reasoning defective, while Davenport-Hines, writing long after the event, condemns the report as disgraceful, slipshod and prurient. After the Denning Report, in defiance of general expectations that he would resign shortly, Macmillan announced his intention to stay on. On the eve of the Conservative Party's annual conference in October 1963 he fell ill; his condition was less serious than he imagined, and his life was not in danger but, convinced he had cancer, he resigned abruptly. Macmillan's successor as prime minister was Lord Home, who renounced his peerage and served as Sir Alec Douglas-Home. In the October 1964 general election the Conservative Party was narrowly defeated, and Wilson became prime minister.Knightley and Kennedy, pp. 257–58 A later commentator opined that the Profumo affair had destroyed the old, aristocratic Conservative Party: "It wouldn't be too much to say that the Profumo scandal was the necessary prelude to the new Toryism, based on meritocracy, which would eventually emerge under Margaret Thatcher". ''The Economist

''The Economist'' is a British weekly newspaper printed in demitab format and published digitally. It focuses on current affairs, international business, politics, technology, and culture. Based in London, the newspaper is owned by The Eco ...

'' suggested that the scandal had effected a fundamental and permanent change in relations between politicians and press. Davenport-Hines posits a longer-term consequence of the affair—the gradual ending of traditional notions of deference: "Authority, however disinterested, well-qualified and experienced, was fter June 1963increasingly greeted with suspicion rather than trust".

After expressing his "deep remorse" to the prime minister, to his constituents and to the Conservative Party, Profumo disappeared from public view. In April 1964 he began working as a volunteer at the Toynbee Hall settlement, a charitable organisation based in Spitalfields which supports the most deprived residents in the

After expressing his "deep remorse" to the prime minister, to his constituents and to the Conservative Party, Profumo disappeared from public view. In April 1964 he began working as a volunteer at the Toynbee Hall settlement, a charitable organisation based in Spitalfields which supports the most deprived residents in the East End of London

The East End of London, often referred to within the London area simply as the East End, is the historic core of wider East London, east of the Roman and medieval walls of the City of London and north of the River Thames. It does not have univ ...

. Profumo continued his association with the settlement for the remainder of his life, at first in a menial capacity, then as administrator, fund-raiser, council member, chairman and finally president. Profumo's charitable work was recognised when he was appointed a Companion of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in 1975. He was later described by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. She was the first female British prime ...

as a national hero, and was a guest at her 80th birthday celebrations in 2005. His marriage to Valerie Hobson lasted until her death on 13 November 1998, aged 81; Profumo died, aged 91, on 9 March 2006.

In December 1963 Keeler pleaded guilty to committing perjury at Gordon's June trial, and she was sentenced to nine months' imprisonment, of which she served six months. After two brief marriages in 1965–66 to James Levermore and in 1971–72 to Anthony Platt that produced a child each, the eldest of whom was largely raised by Keeler's mother Julie, Keeler largely lived alone from the mid-1990s until her death. Most of the considerable amount of money that she made from newspaper stories was dissipated by legal fees; during the 1970s, she said, "I was not living, I was surviving". She published several inconsistent accounts of her life, in which Ward has been variously represented as a "gentleman", her truest love, a Soviet spy, and a traitor ranking alongside Kim Philby

Harold Adrian Russell "Kim" Philby (1 January 191211 May 1988) was a British intelligence officer and a double agent for the Soviet Union. In 1963 he was revealed to be a member of the Cambridge Five, a spy ring which had divulged British s ...

, Guy Burgess

Guy Francis de Moncy Burgess (16 April 1911 – 30 August 1963) was a British diplomat and Soviet agent, and a member of the Cambridge Five spy ring that operated from the mid-1930s to the early years of the Cold War era. His defection in 1951 ...

and Donald Maclean. Keeler also claimed that Profumo impregnated her and that she subsequently underwent a painful abortion

Abortion is the termination of a pregnancy by removal or expulsion of an embryo or fetus. An abortion that occurs without intervention is known as a miscarriage or "spontaneous abortion"; these occur in approximately 30% to 40% of pre ...

. Her portrait, by Ward, was acquired by the National Portrait Gallery in 1984. Christine Keeler died on 4 December 2017, aged 75. Rice-Davies enjoyed a more successful post-scandal career, as nightclub owner, businesswoman, minor actress and novelist. She was married three times, in what she described as her "slow descent into respectability". Of adverse press publicity she observed: "Like royalty, I simply do not complain". Mandy Rice-Davies died on 18 December 2014, aged 70.

Ward's role on behalf of MI5 was confirmed in 1982, when ''The Sunday Times

''The Sunday Times'' is a British newspaper whose circulation makes it the largest in Britain's quality press market category. It was founded in 1821 as ''The New Observer''. It is published by Times Newspapers Ltd, a subsidiary of News UK, whi ...

'' located his former contact "Woods". Although Denning always asserted that Ward's trial and conviction were fair and proper, most commentators believe that it was deeply flawed—an "historical injustice" according to Davenport-Hines, who argues that the trial was an act of political revenge. One High Court judge said privately that he would have stopped the trial before it reached the jury. The human rights lawyer Geoffrey Robertson has campaigned for the case to be reopened on several grounds, including the premature scheduling of the trial, lack of evidence to support the main charges, and various misdirections by the trial judge in his summing up. Above all, the judge failed to advise the jury of the evidence revealed in the Gordon appeal that Keeler, the prosecution's chief witness against Ward, had committed perjury at the Gordon trial. The Criminal Cases Review Commission

The Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC) is the statutory body responsible for investigating alleged miscarriages of justice in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. It was established by Section 8 of the Criminal Appeal Act 1995 and ...

, which has the power to investigate suspected miscarriages of justice, reviewed his case starting in early 2014, but in 2017 decided not to refer it to the Court of Appeal after failing to find the original transcript of the judge's summing up.

After his recall in January 1963, Ivanov disappeared for several decades. In 1992 his memoirs, ''The Naked Spy'', were serialised in ''The Sunday Times''. When this account was challenged by Profumo's lawyers, the publishers removed offending material. In August 2015 ''The Independent

''The Independent'' is a British online newspaper. It was established in 1986 as a national morning printed paper. Nicknamed the ''Indy'', it began as a broadsheet and changed to tabloid format in 2003. The last printed edition was publish ...

'' newspaper published a preview of a forthcoming history of Soviet intelligence activities, by Jonathan Haslam. This book suggests that the relationship between Ivanov and Profumo was closer than the latter admitted. It is alleged that Ivanov visited Profumo's home, and that such was the slackness of security arrangements that the Russian was able to photograph sensitive documents left lying about in the minister's study.

Keeler describes a 1993 meeting with Ivanov in Moscow; she also records that he died the following year, aged 68. Astor was deeply upset at finding himself under police investigation, and by the social ostracism that followed the Ward trial. After his death in 1966, Cliveden was sold. It became first the property of Stanford University

Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, is a private research university in Stanford, California. The campus occupies , among the largest in the United States, and enrolls over 17,000 students. Stanford is conside ...

, and later a luxury hotel. Rachman, who had first come to public notice as a sometime-boyfriend of both Keeler and Rice-Davies, was revealed as an unscrupulous slum landlord; the word "Rachmanism" entered English dictionaries as the standard term for landlords who exploit or intimidate their tenants.

In popular culture

See also

*Chris Pincher scandal

The Chris Pincher scandal is a political controversy in the United Kingdom related to allegations of sexual misconduct by the former Conservative Party Deputy Chief Whip, Chris Pincher. In early July 2022, allegations of Pincher's misconduct ...

Notes and references

;Commentary notes ;CitationsSources

* * * * Originally published as Cmnd. 2152 by Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1963 * * * * * * * * * *External links

1963 Denning Report – Parliament & the 1960s UK Parliament Living Heritage

* {{Harold Macmillan Espionage scandals and incidents Political sex scandals in the United Kingdom Conservative Party (UK) scandals Soviet Union–United Kingdom relations 1963 in the United Kingdom 1963 in international relations 1963 in British politics