Prince Eugene of Savoy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Prince Eugene Francis of Savoy–Carignano, (18 October 1663 – 21 April 1736) better known as Prince Eugene, was a

Prince Eugene was born at the Hôtel de Soissons in Paris on 18 October 1663. His mother,

Prince Eugene was born at the Hôtel de Soissons in Paris on 18 October 1663. His mother,  Together they had had five sons (Eugene being the youngest) and three daughters, but neither parent spent much time with the children: the father, a French general officer, spent much of his time away campaigning, while Olympia's passion for court intrigue meant the children received little attention from her.

The King remained strongly attached to Olympia, so much so that many believed them to be lovers; but her scheming eventually led to her downfall. After falling out of favour at court, Olympia turned to

Catherine Deshayes (known as ''La Voisin''), and to the arts of

Together they had had five sons (Eugene being the youngest) and three daughters, but neither parent spent much time with the children: the father, a French general officer, spent much of his time away campaigning, while Olympia's passion for court intrigue meant the children received little attention from her.

The King remained strongly attached to Olympia, so much so that many believed them to be lovers; but her scheming eventually led to her downfall. After falling out of favour at court, Olympia turned to

Catherine Deshayes (known as ''La Voisin''), and to the arts of

Eugene had no doubt as to where his new allegiance lay, and this loyalty was immediately put to the test. By September, the Imperial forces under the

Eugene had no doubt as to where his new allegiance lay, and this loyalty was immediately put to the test. By September, the Imperial forces under the

In June 1686, the Duke of Lorraine besieged Buda (

In June 1686, the Duke of Lorraine besieged Buda (

The

The

Leopold I had warned Eugene that "he should act with extreme caution, forgo all risks and avoid engaging the enemy unless he has overwhelming strength and is practically certain of being completely victorious", but when the Imperial commander learnt of Sultan

Leopold I had warned Eugene that "he should act with extreme caution, forgo all risks and avoid engaging the enemy unless he has overwhelming strength and is practically certain of being completely victorious", but when the Imperial commander learnt of Sultan

With the death of the infirm and childless Charles II of Spain on 1 November 1700, the succession of the Spanish throne and subsequent control over her empire once again embroiled Europe in war—the

With the death of the infirm and childless Charles II of Spain on 1 November 1700, the succession of the Spanish throne and subsequent control over her empire once again embroiled Europe in war—the  Eugene crossed the

Eugene crossed the

Dissension between Villars and the Elector of Bavaria had prevented an assault on Vienna in 1703, but in the Courts of

Dissension between Villars and the Elector of Bavaria had prevented an assault on Vienna in 1703, but in the Courts of

Events elsewhere now had major consequences for the war in Italy. With Villeroi's crushing defeat by Marlborough at the

Events elsewhere now had major consequences for the war in Italy. With Villeroi's crushing defeat by Marlborough at the

Marlborough now favoured a bold advance along the coast to bypass the major French fortresses, followed by a march on Paris. But fearful of unprotected supply-lines, the Dutch and Eugene favoured a more cautious approach. Marlborough acquiesced and resolved upon the siege of Vauban's great fortress,

Marlborough now favoured a bold advance along the coast to bypass the major French fortresses, followed by a march on Paris. But fearful of unprotected supply-lines, the Dutch and Eugene favoured a more cautious approach. Marlborough acquiesced and resolved upon the siege of Vauban's great fortress,

Following the death of Joseph I on 17 April 1711 his brother,

Following the death of Joseph I on 17 April 1711 his brother,  Hoping to influence public opinion in England and force the French into making substantial concessions, Eugene prepared for a major campaign. But on 21 May 1712—when the Tories felt they had secured favourable terms with their unilateral talks with the French—the Duke of Ormonde (Marlborough's successor) received the so-called 'restraining orders', forbidding him to take part in any military action. Eugene took the fortress of Le Quesnoy in early July, before besieging

Hoping to influence public opinion in England and force the French into making substantial concessions, Eugene prepared for a major campaign. But on 21 May 1712—when the Tories felt they had secured favourable terms with their unilateral talks with the French—the Duke of Ormonde (Marlborough's successor) received the so-called 'restraining orders', forbidding him to take part in any military action. Eugene took the fortress of Le Quesnoy in early July, before besieging

Eugene left Vienna in early June 1716 with a field army of between 80,000 and 90,000 men. By early August 1716 the Ottoman Turks, some 200,000 men under the sultan's son-in-law, the Grand Vizier Damat Ali Pasha, were marching from Belgrade towards Eugene's position west of the fortress of

Eugene left Vienna in early June 1716 with a field army of between 80,000 and 90,000 men. By early August 1716 the Ottoman Turks, some 200,000 men under the sultan's son-in-law, the Grand Vizier Damat Ali Pasha, were marching from Belgrade towards Eugene's position west of the fortress of  Eugene proceeded to take the

Eugene proceeded to take the

While Eugene fought the Turks in the east, unresolved issues following the Utrecht/Rastatt settlements led to hostilities between the Emperor and Philip V of Spain in the west. Charles VI had refused to recognise Philip V as King of Spain, a title which he himself claimed; in return, Philip V had refused to renounce his claims to Naples, Milan, and the Netherlands, all of which had transferred to the House of Austria following the Spanish Succession war. Philip V was roused by his influential wife,

While Eugene fought the Turks in the east, unresolved issues following the Utrecht/Rastatt settlements led to hostilities between the Emperor and Philip V of Spain in the west. Charles VI had refused to recognise Philip V as King of Spain, a title which he himself claimed; in return, Philip V had refused to renounce his claims to Naples, Milan, and the Netherlands, all of which had transferred to the House of Austria following the Spanish Succession war. Philip V was roused by his influential wife,

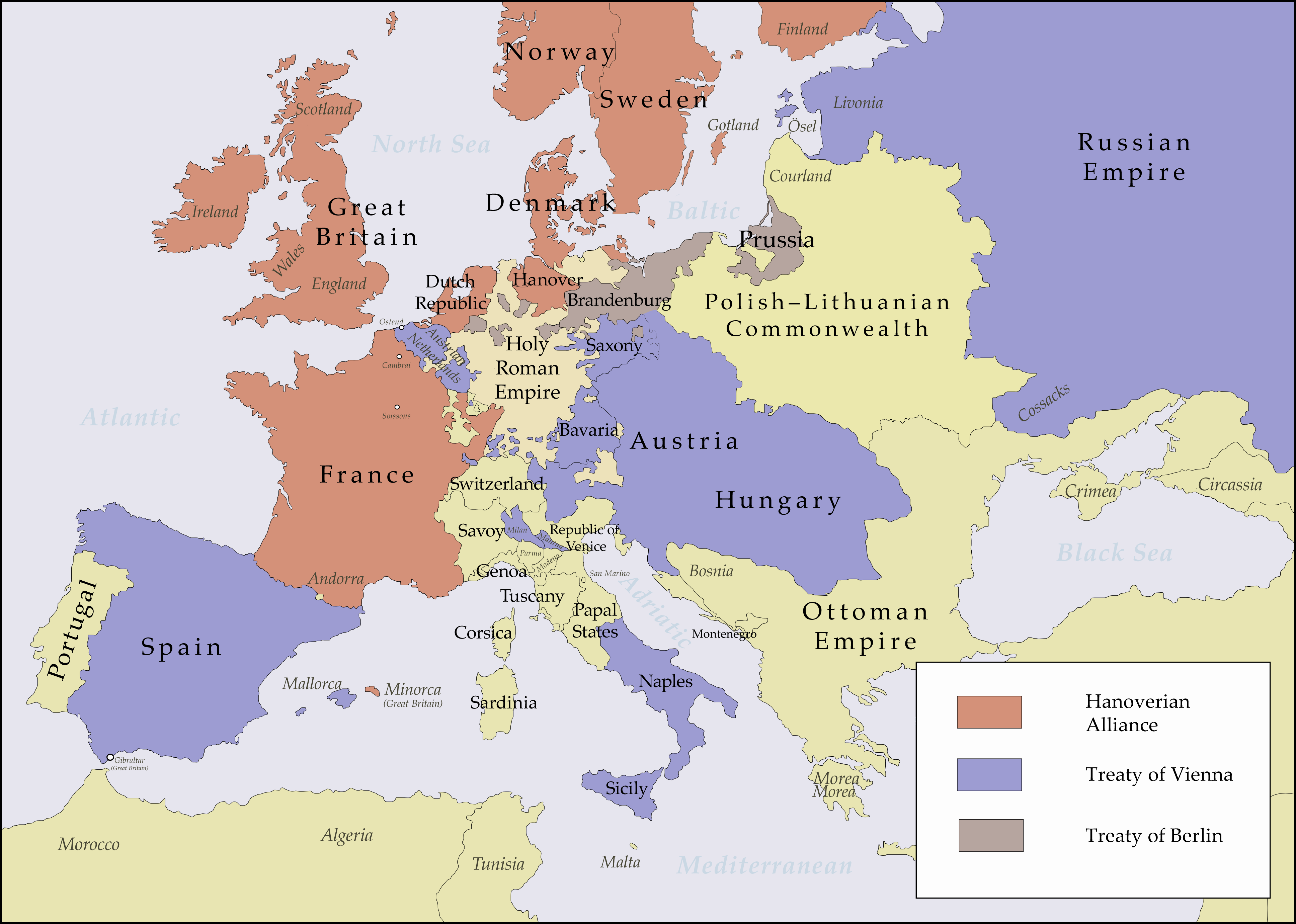

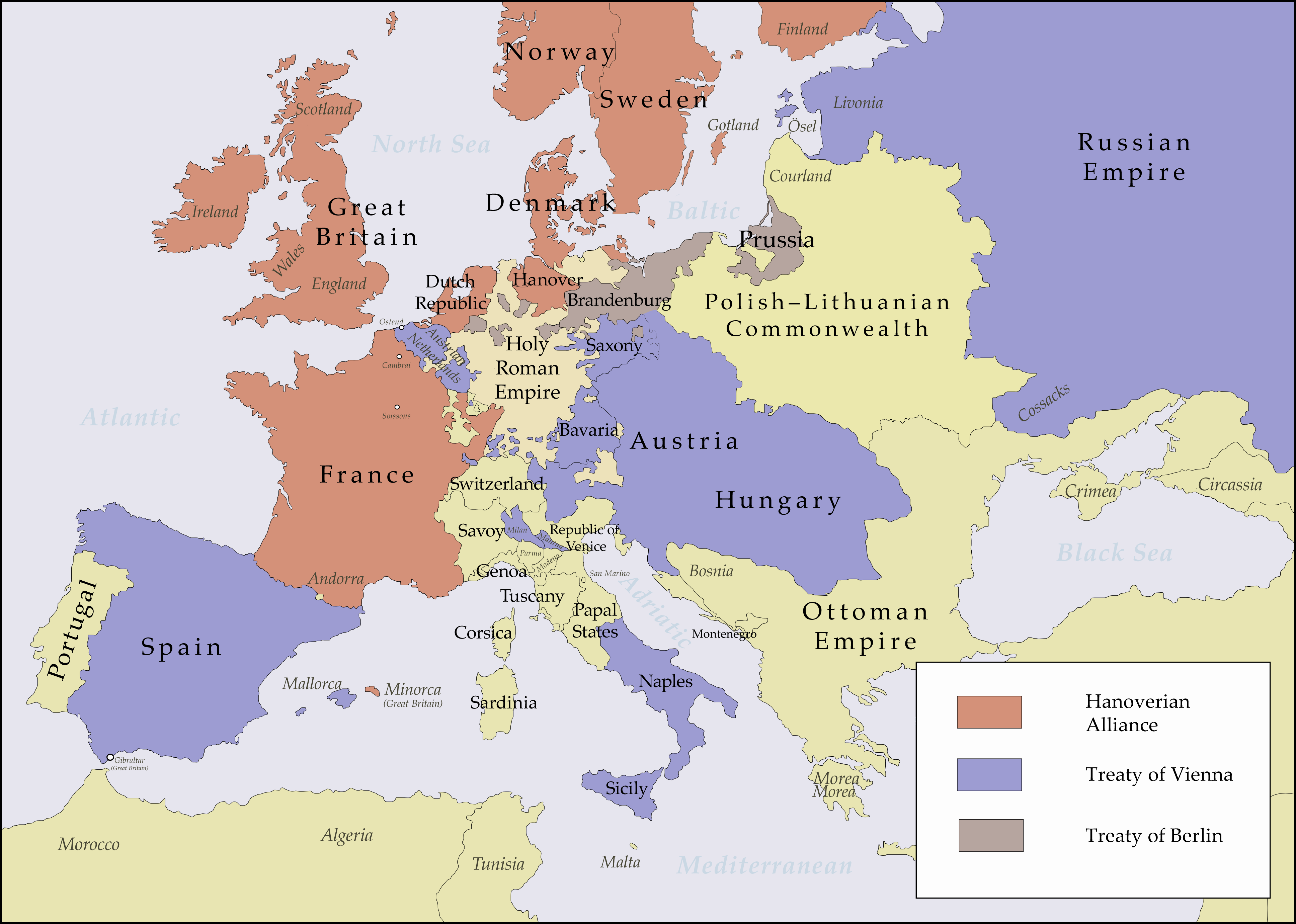

From 1726 Eugene gradually began to regain his political influence. With his many contacts throughout Europe Eugene, backed by Gundaker Starhemberg and Count Schönborn, the Imperial vice-chancellor, managed to secure powerful allies and strengthen the Emperor's position—his skill in managing the vast secret diplomatic network over the coming years was the main reason why Charles VI once again came to depend upon him. In August 1726 Russia acceded to the Austro-Spanish alliance, and in October Frederick William of Prussia followed suit by defecting from the Allies with the signing of a mutual defensive treaty with the Emperor.

From 1726 Eugene gradually began to regain his political influence. With his many contacts throughout Europe Eugene, backed by Gundaker Starhemberg and Count Schönborn, the Imperial vice-chancellor, managed to secure powerful allies and strengthen the Emperor's position—his skill in managing the vast secret diplomatic network over the coming years was the main reason why Charles VI once again came to depend upon him. In August 1726 Russia acceded to the Austro-Spanish alliance, and in October Frederick William of Prussia followed suit by defecting from the Allies with the signing of a mutual defensive treaty with the Emperor.

Despite the conclusion of the brief Anglo-Spanish conflict, war between the European powers persisted throughout 1727–28. In 1729 Elisabeth Farnese abandoned the Austro-Spanish alliance. Realizing that Charles VI could not be drawn into the marriage pact she wanted, Elisabeth concluded that the best way to secure her son's succession to Parma and Tuscany now lay with Britain and France. To Eugene it was 'an event that which is seldom to be found in history'. Following the Prince's determined lead to resist all pressure, Charles VI sent troops into Italy to prevent the entry of Spanish garrisons into the contested duchies. By the beginning of 1730 Eugene, who had remained bellicose throughout the whole period, was again in control of Austrian policy.

In Britain there now emerged a new political re-alignment as the Anglo-French ''entente'' became increasingly defunct. Believing that a resurgent France now posed the greatest danger to their security British ministers, headed by

Despite the conclusion of the brief Anglo-Spanish conflict, war between the European powers persisted throughout 1727–28. In 1729 Elisabeth Farnese abandoned the Austro-Spanish alliance. Realizing that Charles VI could not be drawn into the marriage pact she wanted, Elisabeth concluded that the best way to secure her son's succession to Parma and Tuscany now lay with Britain and France. To Eugene it was 'an event that which is seldom to be found in history'. Following the Prince's determined lead to resist all pressure, Charles VI sent troops into Italy to prevent the entry of Spanish garrisons into the contested duchies. By the beginning of 1730 Eugene, who had remained bellicose throughout the whole period, was again in control of Austrian policy.

In Britain there now emerged a new political re-alignment as the Anglo-French ''entente'' became increasingly defunct. Believing that a resurgent France now posed the greatest danger to their security British ministers, headed by

In 1733 the Polish King and Elector of Saxony,

In 1733 the Polish King and Elector of Saxony,

Eugene never married and was reported to have said that a woman was a hindrance in a war, and that a soldier should never marry, because of this he was called "Mars without Venus".

Eugene never married and was reported to have said that a woman was a hindrance in a war, and that a soldier should never marry, because of this he was called "Mars without Venus".

Eugene's rewards for his victories, his share of booty, his revenues from his abbeys in Savoy, and a steady income from his Imperial offices and governorships, enabled him to contribute to the landscape of

Eugene's rewards for his victories, his share of booty, his revenues from his abbeys in Savoy, and a steady income from his Imperial offices and governorships, enabled him to contribute to the landscape of  In the years following the Peace of Rastatt Eugene became acquainted with a large number of scholarly men. Given his position and responsiveness, they were keen to meet him: few could exist without patronage and this was probably the main reason for

In the years following the Peace of Rastatt Eugene became acquainted with a large number of scholarly men. Given his position and responsiveness, they were keen to meet him: few could exist without patronage and this was probably the main reason for

On the battlefield Eugene demanded courage in his subordinates, and expected his men to fight where and when he wanted; his criteria for promotion were based primarily on obedience to orders and courage on the battlefield rather than social position. On the whole, his men responded because he was willing to push himself as hard as them. His position as President of the Imperial War Council proved less successful. Following the long period of peace after the Austro-Turkish War, the idea of creating a separate field army or providing garrison troops with effective training for them to be turned into such an army quickly was never considered by Eugene. By the time of the War of the Polish Succession, therefore, the Austrians were outclassed by a better prepared French force. For this Eugene was largely to blame—in his view (unlike the drilling and manoeuvres carried out by the Prussians which to Eugene seemed irrelevant to real warfare) the time to create actual fighting men was when war came.

Although Frederick the Great had been struck by the muddle of the Austrian army and its poor organisation during the Polish Succession war, he later amended his initial harsh judgements. "If I understand anything of my trade," commented Frederick in 1758, "especially in the more difficult aspects, I owe that advantage to Prince Eugene. From him I learnt to hold grand objectives constantly in view, and direct all my resources to those ends."Duffy, ''Frederick the Great: A Military Life'', p. 17 To historian

On the battlefield Eugene demanded courage in his subordinates, and expected his men to fight where and when he wanted; his criteria for promotion were based primarily on obedience to orders and courage on the battlefield rather than social position. On the whole, his men responded because he was willing to push himself as hard as them. His position as President of the Imperial War Council proved less successful. Following the long period of peace after the Austro-Turkish War, the idea of creating a separate field army or providing garrison troops with effective training for them to be turned into such an army quickly was never considered by Eugene. By the time of the War of the Polish Succession, therefore, the Austrians were outclassed by a better prepared French force. For this Eugene was largely to blame—in his view (unlike the drilling and manoeuvres carried out by the Prussians which to Eugene seemed irrelevant to real warfare) the time to create actual fighting men was when war came.

Although Frederick the Great had been struck by the muddle of the Austrian army and its poor organisation during the Polish Succession war, he later amended his initial harsh judgements. "If I understand anything of my trade," commented Frederick in 1758, "especially in the more difficult aspects, I owe that advantage to Prince Eugene. From him I learnt to hold grand objectives constantly in view, and direct all my resources to those ends."Duffy, ''Frederick the Great: A Military Life'', p. 17 To historian

* A huge equestrian statue in the centre of Vienna commemorates Eugene's achievements. It is inscribed on one side, 'To the wise counsellor of three Emperors', and on the other, 'To the glorious conqueror of Austria's enemies'.

* Prinz-Eugen-Kapelle, A chapel located at the northern corner of St. Stephen's Cathedral in Vienna

* Prinz-Eugen-Straße a street in

* A huge equestrian statue in the centre of Vienna commemorates Eugene's achievements. It is inscribed on one side, 'To the wise counsellor of three Emperors', and on the other, 'To the glorious conqueror of Austria's enemies'.

* Prinz-Eugen-Kapelle, A chapel located at the northern corner of St. Stephen's Cathedral in Vienna

* Prinz-Eugen-Straße a street in

excerpt

* Hatton, Ragnhild (2001). ''George I.'' Yale University Press. * * * MacMunn, George (1933). ''Prince Eugene: Twin Marshal with Marlborough.'' Sampson Low, Marston & CO., Ltd. * * * * Paoletti, Ciro. "Prince Eugene of Savoy, the Toulon Expedition of 1707, and the English Historians--A Dissenting View." ''Journal of Military History'' 70.4 (2006): 939–962

online

* * * * * * * * Sweet, Paul R. "Prince Eugene of Savoy and Central Europe." ''American Historical Review'' 57.1 (1951): 47–62

in JSTOR

* Sweet, Paul R. "Prince Eugene of Savoy: Two New Biographies." ''Journal of Modern History'' 38.2 (1966): 181–186

in JSTOR

* * * * * * * * * *

field marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, ordinarily senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army and as such few persons are appointed to it. It is considered as ...

in the army of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

and of the Austrian Habsburg dynasty

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

during the 17th and 18th centuries. He was one of the most successful military commanders of his time, and rose to the highest offices of state at the Imperial court in Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

.

Born in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

, Eugene was brought up in the court of King Louis XIV of France

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of ...

. Based on the custom that the youngest sons of noble families were destined for the priesthood, the Prince was initially prepared for a clerical

Clerical may refer to:

* Pertaining to the clergy

* Pertaining to a clerical worker

* Clerical script, a style of Chinese calligraphy

* Clerical People's Party

See also

* Cleric (disambiguation)

Cleric is a member of the clergy.

Cleric may al ...

career, but by the age of 19, he had determined on a military career. Based on his poor physique and bearing, and maybe due to a scandal involving his mother Olympe, he was rejected by Louis XIV for service in the French army. Eugene moved to Austria and transferred his loyalty to the Holy Roman Empire.

In a career spanning six decades, Eugene served three Holy Roman emperors: Leopold I, Joseph I Joseph I or Josef I may refer to:

*Joseph I of Constantinople, Ecumenical Patriarch in 1266–1275 and 1282–1283

* Joseph I, Holy Roman Emperor (1678–1711)

*Joseph I (Chaldean Patriarch) (reigned 1681–1696)

*Joseph I of Portugal (1750–1777) ...

, and Charles VI. His first battle experiences were fought against the Ottomans

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

at the Siege of Vienna in 1683 and the subsequent War of the Holy League, before serving in the Nine Years' War

The Nine Years' War (1688–1697), often called the War of the Grand Alliance or the War of the League of Augsburg, was a conflict between Kingdom of France, France and a European coalition which mainly included the Holy Roman Empire (led by t ...

, in which he fought alongside his cousin, the Duke of Savoy

The titles of count, then of duke of Savoy are titles of nobility attached to the historical territory of Savoy. Since its creation, in the 11th century, the county was held by the House of Savoy. The County of Savoy was elevated to a duchy at ...

. The Prince's fame was secured with his decisive victory against the Ottomans at the Battle of Zenta

The Battle of Zenta, also known as the Battle of Senta, was fought on 11 September 1697, near Zenta, Ottoman Empire (modern-day Senta, Serbia), between Ottoman and Holy League armies during the Great Turkish War. The battle was the most de ...

in 1697, earning him Europe-wide fame. Eugene enhanced his standing during the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phil ...

, where his partnership with the Duke of Marlborough secured victories against the French on the fields of Blenheim Blenheim ( ) is the English name of Blindheim, a village in Bavaria, Germany, which was the site of the Battle of Blenheim in 1704. Almost all places and other things called Blenheim are named directly or indirectly in honour of the battle.

Places ...

(1704), Oudenarde (1708), and Malplaquet (1709); he gained further success in the war as Imperial commander in northern Italy, most notably at the Battle of Turin

The siege of Turin took place from June to September 1706, during the War of the Spanish Succession, when a French army led by Louis de la Feuillade besieged the Savoyard capital of Turin. The campaign by Prince Eugene of Savoy that led to i ...

(1706). Renewed hostilities against the Ottomans in the Austro-Turkish War consolidated his reputation, with victories at the battles of Petrovaradin

Petrovaradin ( sr-cyr, Петроварадин, ) is a historic town in the Serbian province of Vojvodina, now a part of the city of Novi Sad. As of 2011, the urban area has 14,810 inhabitants. Lying on the right bank of the Danube, across from t ...

(1716), and the decisive encounter at the Siege of Belgrade in 1717.

Throughout the late 1720s, Eugene's influence and skillful diplomacy managed to secure the Emperor powerful allies in his dynastic struggles with the Bourbon powers, but physically and mentally fragile in his later years, Eugene enjoyed less success as commander-in-chief of the army during his final conflict, the War of the Polish Succession

The War of the Polish Succession ( pl, Wojna o sukcesję polską; 1733–35) was a major European conflict sparked by a Polish civil war over the succession to Augustus II of Poland, which the other European powers widened in pursuit of thei ...

. Nevertheless, in Austria, Eugene's reputation remains unrivalled. Although opinions differ as to his character, there is no dispute over his great achievements: he helped to save the Habsburg Empire from French conquest; he broke the westward thrust of the Ottomans, liberating parts of Europe after a century and a half of Turkish occupation; and he was one of the great patrons of the arts whose building legacy can still be seen in Vienna today. Eugene died in his sleep at his home on 21 April 1736, aged 72.

Early years (1663–1699)

Hôtel de Soissons

Prince Eugene was born at the Hôtel de Soissons in Paris on 18 October 1663. His mother,

Prince Eugene was born at the Hôtel de Soissons in Paris on 18 October 1663. His mother, Olympia Mancini

Olympia Mancini, Countess of Soissons (French: ''Olympe Mancini''; 11 July 1638 – 9 October 1708) was the second-eldest of the five celebrated Mancini sisters, who along with two of their female Martinozzi cousins, were known at the court of Ki ...

, was one of Cardinal Mazarin

Cardinal Jules Mazarin (, also , , ; 14 July 1602 – 9 March 1661), born Giulio Raimondo Mazzarino () or Mazarini, was an Italian cardinal, diplomat and politician who served as the chief minister to the Kings of France Louis XIII and Louis X ...

's nieces whom the Cardinal had brought to Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

from Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

in 1647 to further his (and, to a lesser extent, their) ambitions. The Mancinis were raised at the Palais-Royal

The Palais-Royal () is a former royal palace located in the 1st arrondissement of Paris, France. The screened entrance court faces the Place du Palais-Royal, opposite the Louvre. Originally called the Palais-Cardinal, it was built for Cardinal R ...

along with the young Louis XIV, with whom Olympia formed an intimate relationship. Yet to her great disappointment, her chance to become queen passed by, and in 1657, she married Eugene Maurice, Count of Soissons, Count of Dreux and Prince of Savoy

Savoy (; frp, Savouè ; french: Savoie ) is a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps.

Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphiné in the south.

Sa ...

.

Together they had had five sons (Eugene being the youngest) and three daughters, but neither parent spent much time with the children: the father, a French general officer, spent much of his time away campaigning, while Olympia's passion for court intrigue meant the children received little attention from her.

The King remained strongly attached to Olympia, so much so that many believed them to be lovers; but her scheming eventually led to her downfall. After falling out of favour at court, Olympia turned to

Catherine Deshayes (known as ''La Voisin''), and to the arts of

Together they had had five sons (Eugene being the youngest) and three daughters, but neither parent spent much time with the children: the father, a French general officer, spent much of his time away campaigning, while Olympia's passion for court intrigue meant the children received little attention from her.

The King remained strongly attached to Olympia, so much so that many believed them to be lovers; but her scheming eventually led to her downfall. After falling out of favour at court, Olympia turned to

Catherine Deshayes (known as ''La Voisin''), and to the arts of black magic

Black magic, also known as dark magic, has traditionally referred to the use of supernatural powers or magic for evil and selfish purposes, specifically the seven magical arts prohibited by canon law, as expounded by Johannes Hartlieb in 14 ...

and astrology

Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that claim to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by studying the apparent positions of celestial objects. Di ...

. It proved a fatal relationship. She became embroiled in the "Affaire des poisons"; suspicions abounded of her involvement in her husband's premature death in 1673, and even implicated her in a plot to kill the King himself. Whatever the truth, Olympia, rather than face trial, subsequently fled France for Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

in January 1680, leaving Eugene in the care of his paternal grandmother, Marie de Bourbon, Countess of Soissons

Marie de Bourbon (3 May 1606 – 3 June 1692) was the wife of Thomas Francis, Prince of Carignano, and thus a princess of Savoy by marriage. At the death of her brother in 1641, she became Countess of Soissons in her own right, passing the titl ...

, and of his paternal aunt, Louise Christine of Savoy, Hereditary Princess of Baden, mother of Prince Louis of Baden.

From the age of ten, Eugene had been brought up for a career in the church since he was the youngest of his family. Eugene's appearance was not impressive — "He was never good-looking …" wrote the Duchess of Orléans

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are ranke ...

, "It is true that his eyes are not ugly, but his nose ruins his face; he has two large teeth which are visible at all times" According to the duchess, who was married to Louis XIV's bisexual brother, the Duke of Orléans

Duke of Orléans (french: Duc d'Orléans) was a French royal title usually granted by the King of France to one of his close relatives (usually a younger brother or son), or otherwise inherited through the male line. First created in 1344 by King ...

, Eugene lived a life of "debauchery" and belonged to a small, effeminate set that included the famous cross-dresser abbé François-Timoléon de Choisy. In February 1683, to the surprise of his family, the 19-year-old Eugene declared his intention of joining the army. Eugene applied directly to Louis XIV for command of a company in French service, but the King—who had shown no compassion for Olympia's children since her disgrace—refused him out of hand. "The request was modest, not so the petitioner", he remarked. "No one else ever presumed to stare me out so insolently." Whatever the case, Louis XIV's choice would cost him dearly twenty years later, for it would be precisely Eugene, in collaboration with the Duke of Marlborough, who would defeat the French army at Blenheim Blenheim ( ) is the English name of Blindheim, a village in Bavaria, Germany, which was the site of the Battle of Blenheim in 1704. Almost all places and other things called Blenheim are named directly or indirectly in honour of the battle.

Places ...

, a decisive battle which checked French military supremacy and political power.

Denied a military career in France, Eugene decided to seek service abroad. One of Eugene's brothers, Louis Julius, had entered Imperial service the previous year, but he had been immediately killed fighting the Ottoman Turks in 1683. When news of his death reached Paris, Eugene decided to travel to Austria in the hope of taking over his brother's command. It was not an unnatural decision: his cousin, Louis of Baden, was already a leading general in the Imperial army, as was a more distant cousin, Maximilian II Emanuel, Elector of Bavaria

Maximilian, Maximillian or Maximiliaan (Maximilien in French) is a male given name.

The name "Max" is considered a shortening of "Maximilian" as well as of several other names.

List of people

Monarchs

*Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor (1459– ...

. On the night of 26 July 1683, Eugene left Paris and headed east. Years later, in his memoirs, Eugene recalled his early years in France:

Great Turkish War

By May 1683, the Ottoman threat to Emperor Leopold I's capital,Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, was very evident. The Grand Vizier

Grand vizier ( fa, وزيرِ اعظم, vazîr-i aʾzam; ota, صدر اعظم, sadr-ı aʾzam; tr, sadrazam) was the title of the effective head of government of many sovereign states in the Islamic world. The office of Grand Vizier was first ...

, Kara Mustafa Pasha

Merzifonlu Kara Mustafa Pasha ( ota, مرزيفونلى قره مصطفى پاشا, tr, Merzifonlu Kara Mustafa Paşa; "Mustafa Pasha the Courageous of Merzifon"; 1634/1635 – 25 December 1683) was an Ottoman nobleman, military figure and ...

—encouraged by Imre Thököly

Imre is a Hungarian masculine first name, which is also in Estonian use, where the corresponding name day is 10 April. It has been suggested that it relates to the name Emeric, Emmerich or Heinrich. Its English equivalents are Emery and Henry ...

's Magyar rebellion—had invaded Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Cr ...

with between 100,000 and 200,000 men; within two months approximately 90,000 were beneath Vienna's walls. With the 'Turks at the gates', the Emperor fled for the safe refuge of Passau

Passau (; bar, label= Central Bavarian, Båssa) is a city in Lower Bavaria, Germany, also known as the Dreiflüssestadt ("City of Three Rivers") as the river Danube is joined by the Inn from the south and the Ilz from the north.

Passau's po ...

up the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

, a more distant and secure part of his dominion. It was at Leopold I's camp that Eugene arrived in mid-August.

Although Eugene was not of Austrian extraction, he did have Habsburg antecedents. His grandfather, Thomas Francis, founder of the Carignano line of the House of Savoy

The House of Savoy ( it, Casa Savoia) was a royal dynasty that was established in 1003 in the historical Savoy region. Through gradual expansion, the family grew in power from ruling a small Alpine county north-west of Italy to absolute rule of ...

, was the son of Catherine Michaela of Spain—a daughter of Philip II of Spain

Philip II) in Spain, while in Portugal and his Italian kingdoms he ruled as Philip I ( pt, Filipe I). (21 May 152713 September 1598), also known as Philip the Prudent ( es, Felipe el Prudente), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from ...

—and the great-grandson of the Emperor Charles V Charles V may refer to:

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661–1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338–1380), called the Wise

* Charles V, Duke of Lorraine (1643–1690)

* Infa ...

. But of more immediate consequence to Leopold I was the fact that Eugene was the second cousin of Victor Amadeus, the Duke of Savoy, a connection that the Emperor hoped might prove useful in any future confrontation with France. These ties, together with his ascetic manner and appearance (a positive advantage to him at the sombre court of Leopold I), ensured the refugee from the hated French king a warm welcome at Passau, and a position in Imperial service. Though French was his favored language, he communicated with Leopold in Italian, as the Emperor (though he knew it perfectly) disliked French. But Eugene also had a reasonable command of German, which he understood very easily, something that helped him much in the military.

Eugene had no doubt as to where his new allegiance lay, and this loyalty was immediately put to the test. By September, the Imperial forces under the

Eugene had no doubt as to where his new allegiance lay, and this loyalty was immediately put to the test. By September, the Imperial forces under the Duke of Lorraine

The rulers of Lorraine have held different posts under different governments over different regions, since its creation as the kingdom of Lotharingia by the Treaty of Prüm, in 855. The first rulers of the newly established region were kings of ...

, together with a powerful Polish army under King John III Sobieski

John III Sobieski ( pl, Jan III Sobieski; lt, Jonas III Sobieskis; la, Ioannes III Sobiscius; 17 August 1629 – 17 June 1696) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1674 until his death in 1696.

Born into Polish nobility, Sobi ...

, were poised to strike the Sultan's army. On the morning of 12 September, the Christian forces drew up in line of battle on the south-eastern slopes of the Vienna Woods

The Vienna Woods (german: Wienerwald) are forested highlands that form the northeastern foothills of the Northern Limestone Alps in the states of Lower Austria and Vienna. The and range of hills is heavily wooded and a popular recreation area ...

, looking down on the massed enemy camp. The day-long Battle of Vienna

The Battle of Vienna; pl, odsiecz wiedeńska, lit=Relief of Vienna or ''bitwa pod Wiedniem''; ota, Beç Ḳalʿası Muḥāṣarası, lit=siege of Beç; tr, İkinci Viyana Kuşatması, lit=second siege of Vienna took place at Kahlenberg Mo ...

resulted in the lifting of the 60-day siege, and the Sultan's forces were routed and in retreat. Serving under Baden, as a twenty-year-old volunteer, Eugene distinguished himself in the battle, earning commendation from Lorraine and the Emperor; he later received the nomination for the colonelcy and was awarded the Kufstein regiment of dragoons by Leopold I.

Holy League

In March 1684, Leopold I formed the Holy League withPoland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

and Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

to counter the Ottoman threat. For the next two years, Eugene continued to perform with distinction on campaign and establish himself as a dedicated, professional soldier; by the end of 1685, still only 22 years old, he was made a Major-General. Little is known of Eugene's life during these early campaigns. Contemporary observers make only passing comments of his actions, and his own surviving correspondence, largely to his cousin Victor Amadeus, are typically reticent about his own feelings and experiences. Nevertheless, it is clear that Baden was impressed with Eugene's qualities—"This young man will, with time, occupy the place of those whom the world regards as great leaders of armies."

In June 1686, the Duke of Lorraine besieged Buda (

In June 1686, the Duke of Lorraine besieged Buda (Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population o ...

), the centre of the Ottoman occupation in Hungary. After resisting for 78 days, the city fell on 2 September, and Turkish resistance collapsed throughout the region as far away as Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the A ...

and Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia ( Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin and the Balkans. It shares land borders with Hu ...

. Further success followed in 1687, where, commanding a cavalry brigade, Eugene made an important contribution to the victory at the Battle of Mohács

The Battle of Mohács (; hu, mohácsi csata, tr, Mohaç Muharebesi or Mohaç Savaşı) was fought on 29 August 1526 near Mohács, Kingdom of Hungary, between the forces of the Kingdom of Hungary and its allies, led by Louis II, and thos ...

on 12 August. Such was the scale of their defeat that the Ottoman army mutinied—a revolt which spread to Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

. The Grand Vizier, Suluieman Pasha, was executed and Sultan Mehmed IV

Mehmed IV ( ota, محمد رابع, Meḥmed-i rābi; tr, IV. Mehmed; 2 January 1642 – 6 January 1693) also known as Mehmed the Hunter ( tr, Avcı Mehmed) was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1648 to 1687. He came to the throne at the a ...

, deposed. Once again, Eugene's courage earned him recognition from his superiors, who granted him the honour of personally conveying the news of victory to the Emperor in Vienna. For his services, Eugene was promoted to Lieutenant-General in November 1687. He was also gaining wider recognition. King Charles II of Spain

Charles II of Spain (''Spanish: Carlos II,'' 6 November 1661 – 1 November 1700), known as the Bewitched (''Spanish: El Hechizado''), was the last Habsburg ruler of the Spanish Empire. Best remembered for his physical disabilities and the War ...

bestowed upon him the Order of the Golden Fleece

The Distinguished Order of the Golden Fleece ( es, Insigne Orden del Toisón de Oro, german: Orden vom Goldenen Vlies) is a Catholic order of chivalry founded in Bruges by Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, in 1430, to celebrate his marriag ...

, while his cousin, Victor Amadeus, provided him with money and two profitable abbeys in Piedmont

it, Piemontese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

. Eugene's military career suffered a temporary setback in 1688 when, on 6 September, the Prince suffered a severe wound to his knee by a musket ball during the Siege of Belgrade, and did not return to active service until January 1689.

Interlude in the west: Nine Years' War

Just asBelgrade

Belgrade ( , ;, ; names in other languages) is the capital and largest city in Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers and the crossroads of the Pannonian Plain and the Balkan Peninsula. Nearly 1,166,763 mi ...

was falling to Imperial forces under Max Emmanuel in the east, French troops in the west were crossing the Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, source ...

into the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

. Louis XIV had hoped that a show of force would lead to a quick resolution to his dynastic and territorial disputes with the princes of the Empire along his eastern border, but his intimidatory moves only strengthened German resolve, and in May 1689, Leopold I and the Dutch signed an offensive compact aimed at repelling French aggression.

The

The Nine Years' War

The Nine Years' War (1688–1697), often called the War of the Grand Alliance or the War of the League of Augsburg, was a conflict between Kingdom of France, France and a European coalition which mainly included the Holy Roman Empire (led by t ...

was professionally and personally frustrating for the Prince. Initially fighting on the Rhine with Max Emmanuel—receiving a slight head wound at the Siege of Mainz in 1689—Eugene subsequently transferred himself to Piedmont after Victor Amadeus joined the Alliance

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

against France in 1690. Promoted to general of cavalry, he arrived in Turin

Turin ( , Piedmontese language, Piedmontese: ; it, Torino ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in Northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital ...

with his friend the Prince of Commercy; but it proved an inauspicious start. Against Eugene's advice, Amadeus insisted on engaging the French at Staffarda and suffered a serious defeat—only Eugene's handling of the Savoyard cavalry in retreat saved his cousin from disaster. Eugene remained unimpressed with the men and their commanders throughout the war in Italy. "The enemy would long ago have been beaten," he wrote to Vienna, "if everyone had done their duty." So contemptuous was he of the Imperial commander, Count Caraffa, he threatened to leave Imperial service.

In Vienna, Eugene's attitude was dismissed as the arrogance of a young upstart, but so impressed was the Emperor by his passion for the Imperial cause, he promoted him to Field-Marshal in 1693. When Caraffa's replacement, Count Caprara, was himself transferred in 1694, it seemed that Eugene's chance for command and decisive action had finally arrived. But Amadeus, doubtful of victory and now more fearful of Habsburg influence in Italy than he was of French, had begun secret dealings with Louis XIV aimed at extricating himself from the war. By 1696, the deal was done, and Amadeus transferred his troops and his loyalty to the enemy. Eugene was never to fully trust his cousin again; although he continued to pay due reverence to the Duke as head of his family, their relationship would forever after remain strained.

Military honours in Italy undoubtedly belonged to the French commander Marshal Catinat, but Eugene, the one Allied general determined on action and decisive results, did well to emerge from the Nine Years' War with an enhanced reputation. With the signing of the Treaty of Ryswick

The Peace of Ryswick, or Rijswijk, was a series of treaties signed in the Dutch city of Rijswijk between 20 September and 30 October 1697. They ended the 1688 to 1697 Nine Years' War between France and the Grand Alliance (League of Augsburg), Gran ...

in September/October 1697, the desultory war in the west was finally brought to an inconclusive end, and Leopold I could once again devote all his martial energies into defeating the Ottoman Turks in the east.

Battle of Zenta

The distractions of the war against Louis XIV had enabled the Turks to recapture Belgrade in 1690. In August 1691, the Austrians, under Louis of Baden, regained the advantage by heavily defeating the Turks at theBattle of Slankamen

The Battle of Slankamen was fought on 19 August 1691, near Slankamen in the Ottoman Sanjak of Syrmia (modern-day Vojvodina, Serbia), between the Ottoman Empire, and Habsburg Austrian forces during the Great Turkish War.

The battle saw a T ...

on the Danube, securing Habsburg possession of Hungary and Transylvania. When Baden was transferred west to fight the French in 1692, his successors, first Caprara, then from 1696, Frederick Augustus, the Elector of Saxony, proved incapable of delivering the final blow. On the advice of the President of the Imperial War Council

The ''Hofkriegsrat'' (or Aulic War Council, sometimes Imperial War Council) established in 1556 was the central military administrative authority of the Habsburg monarchy until 1848 and the predecessor of the Austro-Hungarian Ministry of War. The ...

, Rüdiger Starhemberg, thirty-four-year old Eugene was offered supreme command of Imperial forces in April 1697. This was Eugene's first truly independent command—no longer need he suffer under the excessively cautious generalship of Caprara and Caraffa, or be thwarted by the deviations of Victor Amadeus. But on joining his army, he found it in a state of 'indescribable misery'. Confident and self-assured, the Prince of Savoy (ably assisted by Commercy and Guido Starhemberg

Guido Wald Rüdiger, count of Starhemberg (11 November 1657 – 7 March 1737) was an Austrian military officer (commander-in-chief) and by birth member of the House of Starhemberg.

He was a cousin of Ernst Rüdiger von Starhemberg (1638–170 ...

) set about restoring order and discipline.

Leopold I had warned Eugene that "he should act with extreme caution, forgo all risks and avoid engaging the enemy unless he has overwhelming strength and is practically certain of being completely victorious", but when the Imperial commander learnt of Sultan

Leopold I had warned Eugene that "he should act with extreme caution, forgo all risks and avoid engaging the enemy unless he has overwhelming strength and is practically certain of being completely victorious", but when the Imperial commander learnt of Sultan Mustafa II

Mustafa II (; ota, مصطفى ثانى ''Muṣṭafā-yi sānī''; 6 February 1664 – 29 December 1703) was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1695 to 1703.

Early life

He was born at Edirne Palace on 6 February 1664. He was the son of Sulta ...

's march on Transylvania, Eugene abandoned all ideas of a defensive campaign and moved to intercept the Turks as they crossed the River Tisza

The Tisza, Tysa or Tisa, is one of the major rivers of Central and Eastern Europe. Once, it was called "the most Hungarian river" because it flowed entirely within the Kingdom of Hungary. Today, it crosses several national borders.

The Tisza be ...

at Zenta on 11 September 1697.

It was late in the day before the Imperial army struck. The Turkish cavalry had already crossed the river so Eugene decided to attack immediately, arranging his men in a half-moon formation. The vigour of the assault wrought terror and confusion amongst the Turks, and by nightfall, the battle was won. For the loss of some 2,000 dead and wounded, Eugene had inflicted an overwhelming defeat upon the enemy with approximately 25,000 Turks killed—including the Grand Vizier, Elmas Mehmed Pasha

Elmas Mehmed Pasha (1661 – 11 September 1697) was an Ottoman statesman who served as grand vizier from 1695 to 1697. His epithet ''Elmas'' means "diamond" in Persian and refers to his fame as a handsome man.

Early years

He was a Greek fr ...

, the vizirs of Adana, Anatolia, and Bosnia, plus more than thirty aghas of the Janissaries

A Janissary ( ota, یڭیچری, yeŋiçeri, , ) was a member of the elite infantry units that formed the Ottoman Sultan's household troops and the first modern standing army in Europe. The corps was most likely established under sultan Orhan ...

, sipahi

''Sipahi'' ( ota, سپاهی, translit=sipâhi, label=Persian, ) were professional cavalrymen deployed by the Seljuks, and later the Ottoman Empire, including the land grant-holding (''timar'') provincial '' timarli sipahi'', which constituted ...

s, and silihdars, as well as seven horsetails (symbols of high authority), 100 pieces of heavy artillery, 423 banners, and the revered seal which the sultan always entrusted to the grand vizir on an important campaign, Eugene had annihilated the Turkish army and brought to an end the War of the Holy League. Although the Ottomans lacked western organisation and training, the Savoyard prince had revealed his tactical skill, his capacity for bold decision, and his ability to inspire his men to excel in battle against a dangerous foe.

After a brief terror-raid into Ottoman-held Bosnia, culminating in the sack of Sarajevo

Sarajevo ( ; cyrl, Сарајево, ; ''see names in other languages'') is the capital and largest city of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with a population of 275,524 in its administrative limits. The Sarajevo metropolitan area including Sarajevo ...

, Eugene returned to Vienna in November to a triumphal reception. His victory at Zenta had turned him into a European hero, and with victory came reward. Land in Hungary, given him by the Emperor, yielded a good income, enabling the Prince to cultivate his newly acquired tastes in art and architecture (see below); but for all his new-found wealth and property, he was, nevertheless, without personal ties or family commitments. Of his four brothers, only one was still alive at this time. His fourth brother, Emmanuel, had died aged 14 in 1676; his third, Louis Julius (already mentioned) had died on active service in 1683, and his second brother, Philippe, died of smallpox in 1693. Eugene's remaining brother, Louis Thomas—ostracised for incurring the displeasure of Louis XIV—travelled Europe in search of a career, before arriving in Vienna in 1699. With Eugene's help, Louis found employment in the Imperial army, only to be killed in action against the French in 1702. Of Eugene's sisters, the youngest had died in childhood. The other two, Marie Jeanne-Baptiste and Louise Philiberte, led dissolute lives. Expelled from France, Marie joined her mother in Brussels, before eloping with a renegade priest to Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaking part of Switzerland. Situa ...

, living with him unhappily until her premature death in 1705. Of Louise, little is known after her early salacious life in Paris, but in due course, she lived for a time in a convent in Savoy before her death in 1726.

The Battle of Zenta proved to be the decisive victory in the long war against the Turks. With Leopold I's interests now focused on Spain and the imminent death of Charles II, the Emperor terminated the conflict with the Sultan; he signed the Treaty of Karlowitz

The Treaty of Karlowitz was signed in Karlowitz, Military Frontier of Archduchy of Austria (present-day Sremski Karlovci, Serbia), on 26 January 1699, concluding the Great Turkish War of 1683–1697 in which the Ottoman Empire was defeated by ...

on 26 January 1699.

Middle life (1700–20)

War of the Spanish Succession

With the death of the infirm and childless Charles II of Spain on 1 November 1700, the succession of the Spanish throne and subsequent control over her empire once again embroiled Europe in war—the

With the death of the infirm and childless Charles II of Spain on 1 November 1700, the succession of the Spanish throne and subsequent control over her empire once again embroiled Europe in war—the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phil ...

. On his deathbed Charles II had bequeathed the entire Spanish inheritance to Louis XIV's grandson, Philip, Duke of Anjou. This threatened to unite the Spanish and French kingdoms under the House of Bourbon

The House of Bourbon (, also ; ) is a European dynasty of French origin, a branch of the Capetian dynasty, the royal House of France. Bourbon kings first ruled France and Navarre in the 16th century. By the 18th century, members of the Spani ...

—something unacceptable to England, the Dutch Republic, and Leopold I, who had himself a claim to the Spanish throne. From the beginning, the Emperor had refused to accept the will of Charles II, and he did not wait for England and the Dutch Republic to begin hostilities. Before a new Grand Alliance could be concluded Leopold I prepared to send an expedition to seize the Spanish lands in Italy.

Eugene crossed the

Eugene crossed the Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Sw ...

with some 30,000 men in May/June 1701. After a series of brilliant manoeuvres the Imperial commander defeated Catinat at the Battle of Carpi

The Battle of Carpi was a series of manoeuvres in the summer of 1701, and the first battle of the War of the Spanish Succession that took place on 9 July 1701 between France and Austria. It was a minor skirmish that the French commander decide ...

on 9 July. "I have warned you that you are dealing with an enterprising young prince," wrote Louis XIV to his commander, "he does not tie himself down to the rules of war." On 1 September Eugene defeated Catinat's successor, Marshal Villeroi, at the Battle of Chiari

The Battle of Chiari was fought on 1 September 1701 during the War of the Spanish Succession. The engagement was part of Prince Eugene of Savoy's campaign to seize the Spanish controlled Duchy of Milan in the Italian peninsula, and had followed hi ...

, in a clash as destructive as any in the Italian theatre. But as so often throughout his career the Prince faced war on two fronts—the enemy in the field and the government in Vienna.

Starved of supplies, money, and men, Eugene was forced into unconventional means against the vastly superior enemy. During a daring raid on Cremona on the night of 31 January/1 February 1702 Eugene captured the French commander-in-chief. Yet the coup was less successful than hoped: Cremona remained in French hands, and the Duke of Vendôme

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are ranke ...

, whose talents far exceeded Villeroi's, became the theatre's new commander. Villeroi's capture caused a sensation in Europe and had a galvanising effect on English public opinion. "The surprise at Cremona," wrote the diarist John Evelyn

John Evelyn (31 October 162027 February 1706) was an English writer, landowner, gardener, courtier and minor government official, who is now best known as a diarist. He was a founding Fellow of the Royal Society.

John Evelyn's diary, or m ...

, "… was the great discourse of this week"; but appeals for succour from Vienna remained unheeded, forcing Eugene to seek battle and gain a 'lucky hit'. The resulting Battle of Luzzara

The Battle of Luzzara took place in Lombardy on 15 August 1702 during the War of the Spanish Succession, between a combined French and Savoyard army under Louis Joseph, duc de Vendôme, and an Imperial force under Prince Eugene.

Conflict in ...

on 15 August proved inconclusive. Although Eugene's forces inflicted double the number of casualties on the French the battle settled little except to deter Vendôme trying an all-out assault on Imperial forces that year, enabling Eugene to hold on the south of the Alps. With his army rotting away, and personally grieving for his long-standing friend Prince Commercy who had died at Luzzara, Eugene returned to Vienna in January 1703.

President of the Imperial War Council

Eugene's European reputation was growing (Cremona and Luzzara had been celebrated as victories throughout the Allied capitals), yet because of the condition and morale of his troops the 1702 campaign had not been a success. Austria itself was now facing the direct threat of invasion from across the border inBavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total l ...

where the state's Elector, Maximilian Emanuel, had declared for the Bourbons in August the previous year. Meanwhile, in Hungary a small-scale revolt had broken out in May and was fast gaining momentum. With the monarchy at the point of complete financial breakdown Leopold I was at last persuaded to change the government. At the end of June 1703 Gundaker Starhemberg

Gundaker Thomas Starhemberg (Vienna, December 14, 1663 – Prague, July 8, 1745) was an Austrian economist and politician.

Early life

His parents were Konrad Balthasar von Starhemberg (1612–1687) and Countess Franziska Katharina Cavri ...

replaced Gotthard Salaburg as President of the Treasury, and Prince Eugene succeeded Henry Mansfeld as the new President of the Imperial War Council

A council of war is a term in military science that describes a meeting held to decide on a course of action, usually in the midst of a battle. Under normal circumstances, decisions are made by a commanding officer, optionally communicated ...

(''Hofkriegsratspräsident'').

As head of the war council Eugene was now part of the Emperor's inner circle, and the first president since Montecuccoli to remain an active commander. Immediate steps were taken to improve efficiency within the army: encouragement and, where possible, money, was sent to the commanders in the field; promotion and honours were distributed according to service rather than influence; and discipline improved. But the Austrian monarchy faced severe peril on several fronts in 1703: by June the Duke of Villars

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are r ...

had reinforced the Elector of Bavaria on the Danube thus posing a direct threat to Vienna, while Vendôme remained at the head of a large army in northern Italy opposing Guido Starhemberg's weak Imperial force. Of equal alarm was Francis II Rákóczi

Francis II Rákóczi ( hu, II. Rákóczi Ferenc, ; 27 March 1676 – 8 April 1735) was a Hungarian nobleman and leader of Rákóczi's War of Independence against the Habsburgs in 1703–11 as the prince ( hu, fejedelem) of the Estates Confedera ...

's revolt

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

which, by the end of the year, had reached as far as Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The ...

and Lower Austria

Lower Austria (german: Niederösterreich; Austro-Bavarian: ''Niedaöstareich'', ''Niedaestareich'') is one of the nine states of Austria, located in the northeastern corner of the country. Since 1986, the capital of Lower Austria has been Sankt P ...

.

Blenheim

Dissension between Villars and the Elector of Bavaria had prevented an assault on Vienna in 1703, but in the Courts of

Dissension between Villars and the Elector of Bavaria had prevented an assault on Vienna in 1703, but in the Courts of Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; french: Château de Versailles ) is a former royal residence built by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, about west of Paris, France. The palace is owned by the French Republic and since 1995 has been managed, ...

and Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

, ministers confidently anticipated the city's fall. The Imperial ambassador in London, Count Wratislaw, had pressed for Anglo-Dutch assistance on the Danube as early as February 1703, but the crisis in southern Europe seemed remote from the Court of St. James's

The Court of St James's is the royal court for the Sovereign of the United Kingdom. All ambassadors to the United Kingdom are formally received by the court. All ambassadors from the United Kingdom are formally accredited from the court – & ...

where colonial and commercial considerations were more to the fore of men's minds. Only a handful of statesmen in England or the Dutch Republic realised the true implications of Austria's peril; foremost amongst these was the English Captain-General, the Duke of Marlborough.

By early 1704 Marlborough had resolved to march south and rescue the situation in southern Germany and on the Danube, personally requesting the presence of Eugene on campaign so as to have "a supporter of his zeal and experience". The Allied commanders met for the first time at the small village of Mundelsheim

Mundelsheim is a municipality in the German state of Baden-Wuerttemberg. It is located in the Ludwigsburg district, about 30 km north of Stuttgart and 20 km south of Heilbronn, on the Neckar river. It belongs to the Stuttgart Metrop ...

on 10 June, and immediately formed a close rapport—the two men becoming, in the words of Thomas Lediard, 'Twin constellations in glory'. This professional and personal bond ensured mutual support on the battlefield, enabling many successes during the Spanish Succession war. The first of these victories, and the most celebrated, came on 13 August 1704 at the Battle of Blenheim

The Battle of Blenheim (german: Zweite Schlacht bei Höchstädt, link=no; french: Bataille de Höchstädt, link=no; nl, Slag bij Blenheim, link=no) fought on , was a major battle of the War of the Spanish Succession. The overwhelming Allied ...

. Eugene commanded the right wing of the Allied army, holding the Elector of Bavaria's and Marshal Marsin's superior forces, while Marlborough broke through the Marshal Tallard's center, inflicting over 30,000 casualties. The battle proved decisive: Vienna was saved and Bavaria was knocked out of the war. Both Allied commanders were full of praise for each other's performance. Eugene's holding operation, and his pressure for action leading up to the battle, proved crucial for the Allied success.

In Europe Blenheim is regarded as much a victory for Eugene as it is for Marlborough, a sentiment echoed by Sir Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

(Marlborough's descendant and biographer), who pays tribute to "the glory of Prince Eugene, whose fire and spirit had exhorted the wonderful exertions of his troops." France now faced the real danger of invasion, but Leopold I in Vienna was still under severe strain: Rákóczi

The House of Rákóczi (older spelling Rákóczy) was a Hungarian noble family in the Kingdom of Hungary between the 13th century and 18th century. Their name is also spelled ''Rákoci'' (in Slovakia), ''Rakoczi'' and ''Rakoczy'' in some forei ...

's revolt

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

was a major threat; and Guido Starhemberg and Victor Amadeus (who had once again switched loyalties and rejoined the Grand Alliance in 1703) had been unable to halt the French under Vendôme in northern Italy. Only Amadeus' capital, Turin

Turin ( , Piedmontese language, Piedmontese: ; it, Torino ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in Northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital ...

, held on.

Turin and Toulon

Eugene returned to Italy in April 1705, but his attempts to move west towards Turin were thwarted by Vendôme's skillful manoeuvres. Lacking boats and bridging materials, and with desertion and sickness rife within his army, the outnumbered Imperial commander was helpless. Leopold I's assurances of money and men had proved illusory, but desperate appeals from Amadeus and criticism from Vienna goaded the Prince into action, resulting in the Imperialists' bloody defeat at the Battle of Cassano on 16 August. Following Leopold I's death and the accession ofJoseph I Joseph I or Josef I may refer to:

*Joseph I of Constantinople, Ecumenical Patriarch in 1266–1275 and 1282–1283

* Joseph I, Holy Roman Emperor (1678–1711)

*Joseph I (Chaldean Patriarch) (reigned 1681–1696)

*Joseph I of Portugal (1750–1777) ...

to the Imperial throne in May 1705, Eugene began to receive the personal backing he desired. Joseph I proved to be a strong supporter of Eugene's supremacy in military affairs; he was the most effective emperor the Prince served and the one he was happiest under. Promising support, Joseph I persuaded Eugene to return to Italy and restore Habsburg honour.

The Imperial commander arrived in theatre in mid-April 1706, just in time to organise an orderly retreat of what was left of Count Reventlow's inferior army following his defeat by Vendôme at the Battle of Calcinato

The Battle of Calcinato took place near the town of Calcinato in Lombardy, Italy on 19 April 1706 during the War of the Spanish Succession between a French-led force under the duc de Vendôme and an Imperial army under Graf von Reventlow. I ...

on 19 April. Vendôme now prepared to defend the lines along the river Adige

The Adige (; german: Etsch ; vec, Àdexe ; rm, Adisch ; lld, Adesc; la, Athesis; grc, Ἄθεσις, Áthesis, or , ''Átagis'') is the second-longest river in Italy, after the Po. It rises near the Reschen Pass in the Vinschgau in the pro ...

, determined to keep Eugene cooped to the east while the Marquis of La Feuillade threatened Turin. Feigning attacks along the Adige, Eugene descended south across the river Po in mid-July, outmanoeuvring the French commander and gaining a favourable position from which he could at last move west towards Piedmont and relieve Savoy's capital.

Events elsewhere now had major consequences for the war in Italy. With Villeroi's crushing defeat by Marlborough at the

Events elsewhere now had major consequences for the war in Italy. With Villeroi's crushing defeat by Marlborough at the Battle of Ramillies

The Battle of Ramillies (), fought on 23 May 1706, was a battle of the War of the Spanish Succession. For the Grand Alliance – Austria, England, and the Dutch Republic – the battle had followed an indecisive campaign against the Bourbon a ...

on 23 May, Louis XIV recalled Vendôme north to take command of French forces in Flanders. It was a transfer that Saint-Simon considered something of a deliverance for the French commander who was "now beginning to feel the unlikelihood of success n Italy

N, or n, is the fourteenth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''en'' (pronounced ), plural ''ens''.

History

...

… for Prince Eugene, with the reinforcements that had joined him after the Battle of Calcinato, had entirely changed the outlook in that theatre of the war." The Duke of Orléans

Duke of Orléans (french: Duc d'Orléans) was a French royal title usually granted by the King of France to one of his close relatives (usually a younger brother or son), or otherwise inherited through the male line. First created in 1344 by King ...

, under the direction of Marsin, replaced Vendôme, but indecision and disorder in the French camp led to their undoing. After uniting his forces with Victor Amadeus at Villastellone

Villastellone is a '' comune'' (municipality) in the Metropolitan City of Turin in the Italian region Piedmont, located about 15 km south of Turin.

Villastellone borders the following municipalities: Moncalieri, Cambiano, Santena, Poirino, C ...

in early September, Eugene attacked, overwhelmed, and decisively defeated the French forces besieging Turin on 7 September. Eugene's success broke the French hold on northern Italy, and the whole Po valley fell under Allied control. Eugene had gained a victory as signal as his colleague had at Ramillies—"It is impossible for me to express the joy it has given me;" wrote Marlborough, "for I not only esteem but I really love the prince. This glorious action must bring France so low, that if our friends could but be persuaded to carry on the war with vigour one year longer, we cannot fail, with the blessing of God, to have such a peace as will give us quiet for all our days."

The Imperial victory in Italy marked the beginning of Austrian rule in Lombardy, and earned Eugene the Governorship of Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city ...

. But the following year was to prove a disappointment for the Prince and the Grand Alliance as a whole. The Emperor and Eugene (whose main goal after Turin was to take Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adm ...

and Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

from Philip duc d'Anjou's supporters), reluctantly agreed to Marlborough's plan for an attack on Toulon—the seat of French naval power in the Mediterranean. Disunion between the Allied commanders—Victor Amadeus, Eugene, and the English Admiral Shovell—doomed the Toulon enterprise to failure. Although Eugene favoured some sort of attack on France's south-eastern border it was clear he felt the expedition impractical, and showed none of the "alacrity which he had displayed on other occasions." Substantial French reinforcements finally brought an end to the venture, and on 22 August 1707, the Imperial army began its retirement. The subsequent capture of Susa

Susa ( ; Middle elx, 𒀸𒋗𒊺𒂗, translit=Šušen; Middle and Neo- elx, 𒋢𒋢𒌦, translit=Šušun; Neo- Elamite and Achaemenid elx, 𒀸𒋗𒐼𒀭, translit=Šušán; Achaemenid elx, 𒀸𒋗𒐼, translit=Šušá; fa, شوش ...

could not compensate for the total collapse of the Toulon expedition and with it any hope of an Allied war-winning blow that year.

Oudenarde and Malplaquet

At the beginning of 1708 Eugene successfully evaded calls for him to take charge in Spain (in the end Guido Starhemberg was sent), thus enabling him to take command of the Imperial army on theMoselle

The Moselle ( , ; german: Mosel ; lb, Musel ) is a river that rises in the Vosges mountains and flows through north-eastern France and Luxembourg to western Germany. It is a left bank tributary of the Rhine, which it joins at Koblenz. A ...

and once again unite with Marlborough in the Spanish Netherlands. Eugene (without his army) arrived at the Allied camp at Assche, west of Brussels, in early July, providing a welcome boost to morale after the early defection of Bruges

Bruges ( , nl, Brugge ) is the capital and largest City status in Belgium, city of the Provinces of Belgium, province of West Flanders in the Flemish Region of Belgium, in the northwest of the country, and the sixth-largest city of the countr ...

and Ghent

Ghent ( nl, Gent ; french: Gand ; traditional English: Gaunt) is a city and a municipality in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is the capital and largest city of the East Flanders province, and the third largest in the country, exceeded i ...

to the French. " … our affairs improved through God's support and Eugene's aid," wrote the Prussian General Natzmer Natzmer is a Pomeranian noble family. Heinrich August Pierer">Natzmer. In: Heinrich August Pierer, Julius Löbe: Universal-Lexikon der Gegenwart und Vergangenheit. 4. Auflage. Band 11. Altenburg 1860, S. 717/ref> Notable people with the surname incl ...

, "whose timely arrival raised the spirits of the army again and consoled us." Heartened by the Prince's confidence the Allied commanders devised a bold plan to engage the French army under Vendôme and the Duke of Burgundy

Duke of Burgundy (french: duc de Bourgogne) was a title used by the rulers of the Duchy of Burgundy, from its establishment in 843 to its annexation by France in 1477, and later by Holy Roman Emperors and Kings of Spain from the House of Habsburg ...

. On 10 July the Anglo-Dutch army made a forced march to surprise the French, reaching the river Scheldt

The Scheldt (french: Escaut ; nl, Schelde ) is a river that flows through northern France, western Belgium, and the southwestern part of the Netherlands, with its mouth at the North Sea. Its name is derived from an adjective corresponding to ...

just as the enemy was crossing to the north. The ensuing battle on 11 July—more a contact action rather than a set-piece engagement—ended in a resounding success for the Allies, aided by the dissension of the two French commanders. While Marlborough remained in overall command, Eugene had led the crucial right flank and centre. Once again the Allied commanders had co-operated remarkably well. "Prince Eugene and I," wrote the Duke, "shall never differ about our share of the laurels."

Marlborough now favoured a bold advance along the coast to bypass the major French fortresses, followed by a march on Paris. But fearful of unprotected supply-lines, the Dutch and Eugene favoured a more cautious approach. Marlborough acquiesced and resolved upon the siege of Vauban's great fortress,

Marlborough now favoured a bold advance along the coast to bypass the major French fortresses, followed by a march on Paris. But fearful of unprotected supply-lines, the Dutch and Eugene favoured a more cautious approach. Marlborough acquiesced and resolved upon the siege of Vauban's great fortress, Lille

Lille ( , ; nl, Rijsel ; pcd, Lile; vls, Rysel) is a city in the northern part of France, in French Flanders. On the river Deûle, near France's border with Belgium, it is the capital of the Hauts-de-France region, the prefecture of the No ...

. While the Duke commanded the covering force, Eugene oversaw the siege of the town which surrendered on 22 October but Marshal Boufflers did not yield the citadel

A citadel is the core fortified area of a town or city. It may be a castle, fortress, or fortified center. The term is a diminutive of "city", meaning "little city", because it is a smaller part of the city of which it is the defensive core.

In ...