Presidency of Rutherford B. Hayes on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The presidency of Rutherford B. Hayes began on March 4, 1877, when

With the retirement of President

With the retirement of President

There was considerable debate about which person or house of Congress was authorized to decide between the competing slates of electors, with the Republican Senate and the Democratic House each claiming priority. By January 1877, with the question still unresolved, Congress and President Grant agreed to submit the matter to a bipartisan

There was considerable debate about which person or house of Congress was authorized to decide between the competing slates of electors, with the Republican Senate and the Democratic House each claiming priority. By January 1877, with the question still unresolved, Congress and President Grant agreed to submit the matter to a bipartisan

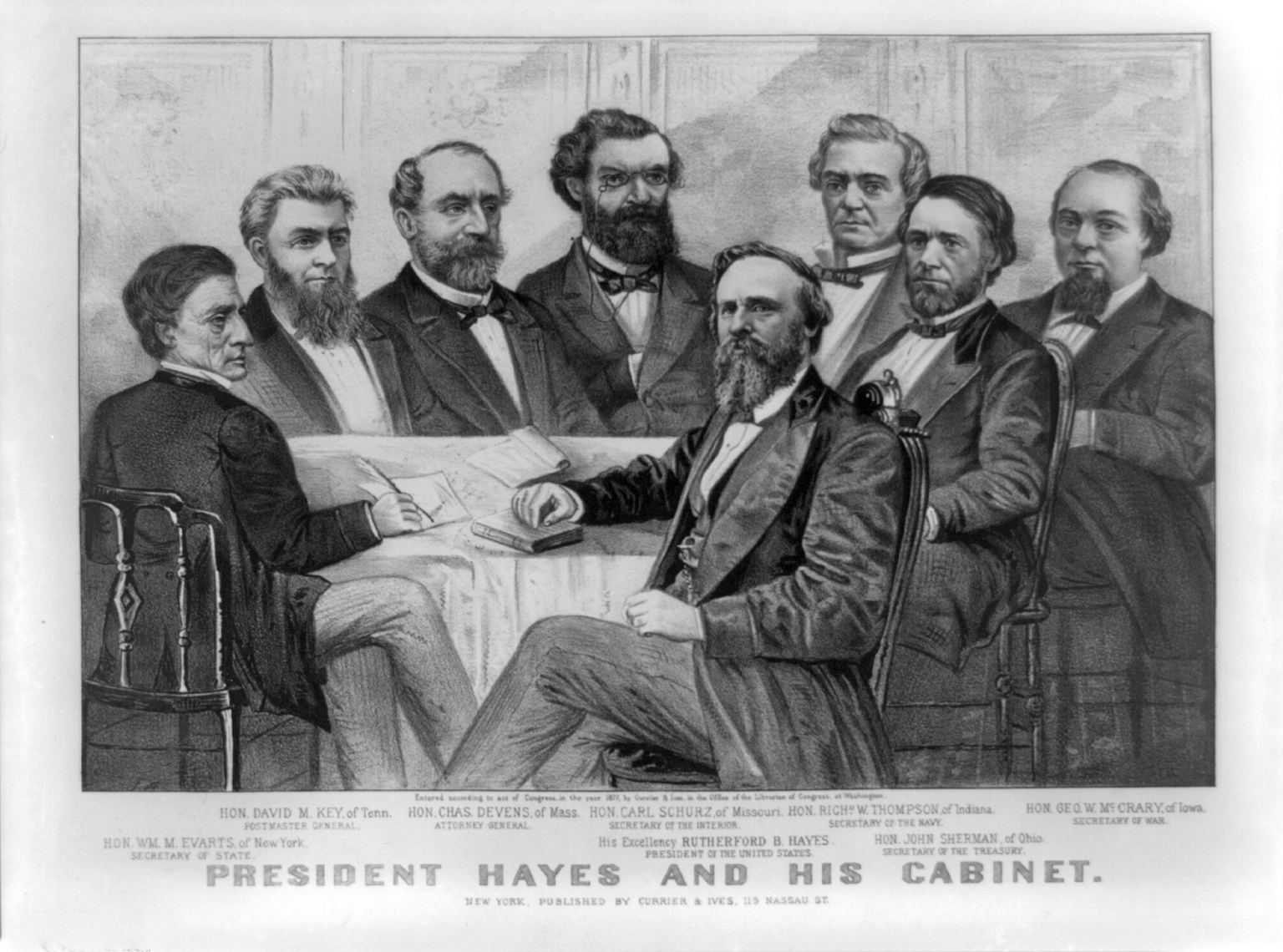

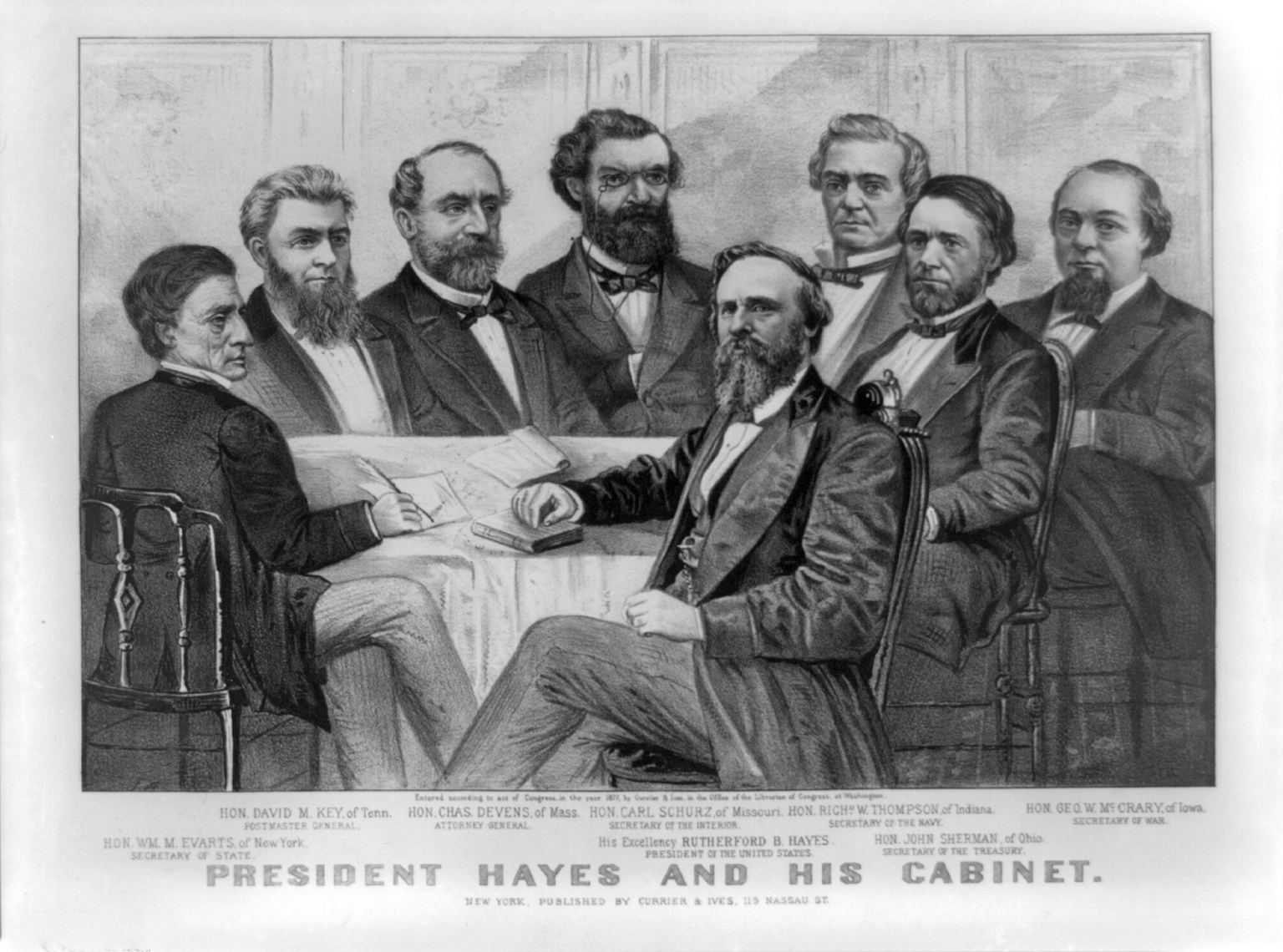

In choosing the members of his cabinet, Hayes spurned

In choosing the members of his cabinet, Hayes spurned

Hayes appointed two

Hayes appointed two

After ending Reconstruction, Hayes turned to the issue of civil service reform. Instead of giving federal jobs to political supporters or the favorites of powerful members of Congress, Hayes favored appointment based on performance in

After ending Reconstruction, Hayes turned to the issue of civil service reform. Instead of giving federal jobs to political supporters or the favorites of powerful members of Congress, Hayes favored appointment based on performance in

In his first year in office, Hayes was faced with the

In his first year in office, Hayes was faced with the

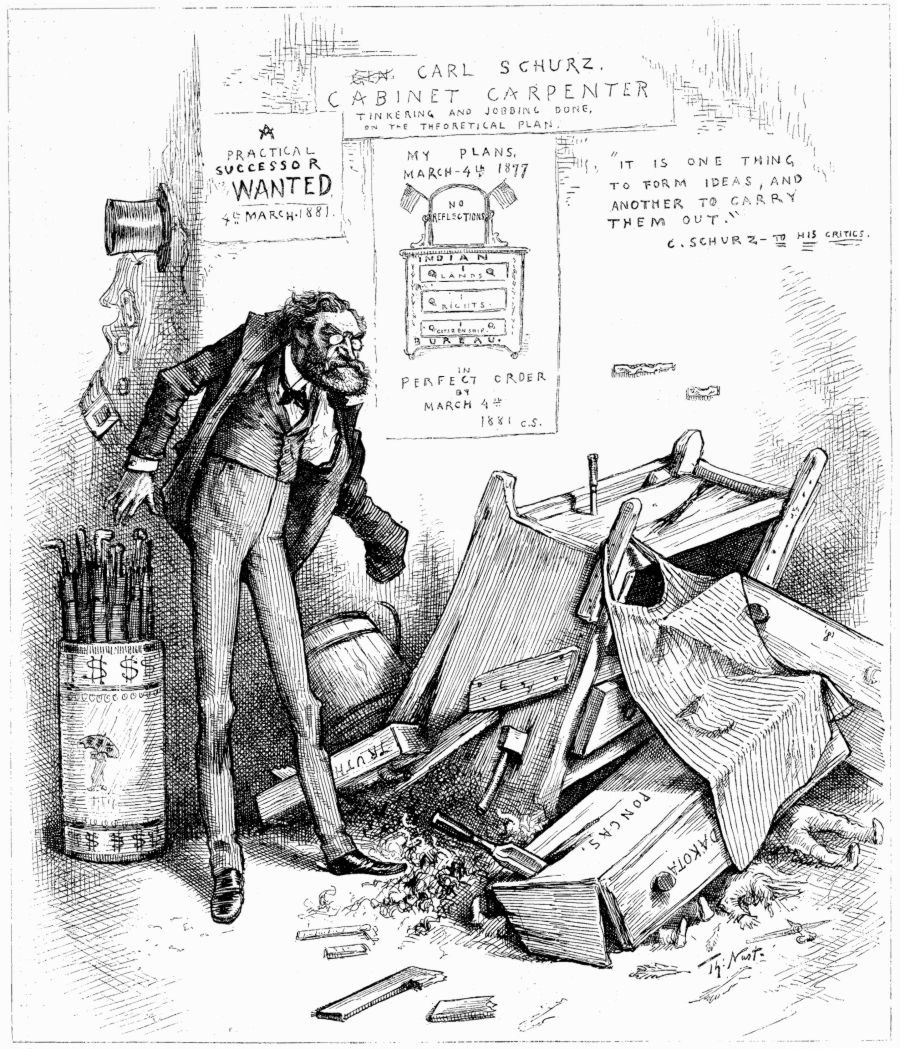

Interior Secretary Schurz carried out Hayes's American Indian policy, beginning with preventing the

Interior Secretary Schurz carried out Hayes's American Indian policy, beginning with preventing the

The

The

Although some Republicans urged Hayes to run for a second term, he was looking forward to retirement, and so stuck to his 1876 promise to serve only one term. When Republicans convened in June 1880, in Chicago, the fight for the nomination stood between former President Grant and Senator James Blaine. Congressman

Although some Republicans urged Hayes to run for a second term, he was looking forward to retirement, and so stuck to his 1876 promise to serve only one term. When Republicans convened in June 1880, in Chicago, the fight for the nomination stood between former President Grant and Senator James Blaine. Congressman

online free

* * * * * * Logan, Rayford W. ''The Betrayal of the Negro: From Rutherford B. Hayes to Woodrow Wilson'' (Collier Books, 1965). * Morris, Roy. ''Fraud of the century: Rutherford B. Hayes, Samuel Tilden, and the stolen election of 1876'' ( New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003). * * * Quince, Charles. ''Rutherford B. Hayes and the Restoration of Presidential Powers'' (2020). * * Rhodes, James Ford. ''History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850: 1877-1896'' (1919

online complete

pp 1-109; old, factual and heavily political, by winner of Pulitzer Prize * * * Simpson, Brooks D. ''The Reconstruction Presidents'' (1998) pp 198-228 on Hayes. * * * * * Williams, Charles Richard. ''Life of Rutherford Birchard Hayes'' (2 vol 1914);

vol 1 to 1877 online

als

vol 2 from 1877 online

* Woodward, C. Vann. ''Reunion and Reaction: The Compromise of 1877 and the End of Reconstruction'' (1951).

online

* * De Santis, Vincent P. "President Hayes's Southern Policy." ''Journal of Southern History'' 21.4 (1955): 476-494

online

* Deacon, Kristine. "On the Road with Rutherford B. Hayes: Oregon's First Presidential Visit, 1880." ''Oregon Historical Quarterly'' 112.2 (2011): 170-193

online

* Gallagher, Douglas Steven. "The 'smallest mistake': explaining the failures of the Hayes and Harrison presidencies." ''White House Studies'' 2.4 (2002): 395-414. * * McPherson, James M. "Coercion or conciliation? abolitionists debate President Hayes's southern policy." ''New England Quarterly'' (1966): 474-497

online

* Moore, Dorothy L. "William A. Howard and the Nomination of Rutherford B. Hayes for the Presidency." ''Vermont History'' 38#4 (1970) pp. 316–319.

online

* * Peskin, Allan. "Rutherford B. Hayes: the road to the white house." in Edward O. Frantz, ed. ''A Companion to the Reconstruction Presidents 1865–1881'' (2014): 403-414. * Polakoff, Keith Ian. "Rutherford B. Hayes" in Henry F. Graff. ed. ''The Presidents: A Reference History'' (3rd ed. 2002) pp 261–72

online

* Ross, Michael A. "Rutherford B. Hayes." in ''The Presidents and the Constitution'' (Volume One. New York University Press, 2020). 253-265. * Skidmore, Max J. ''Maligned Presidents: The Late 19th Century'' (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014) pp. 50–62. * * * * * * Vazzano, Frank P. "Rutherford B. Hayes and the Politics of Discord." ''Historian'' 68.3 (2006): 519-540

online

* Vazzano, Frank P. "President Hayes, Congress and the Appropriations Riders Vetoes." ''Congress & the Presidency: A Journal of Capital Studies'' 20#1 (1993).

online

*

White House biography

The Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Center

from the

Extensive essays on Rutherford B. Hayes

and shorter essays on each member of his cabinet and First Lady from the

"Life Portrait of Rutherford B. Hayes"

from C-SPAN's '' American Presidents: Life Portraits'', July 19, 1999 {{Authority control 1870s in the United States 1880s in the United States Hayes, Rutherford B. 1877 establishments in the United States 1881 disestablishments in the United States

Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governo ...

was inaugurated

In government and politics, inauguration is the process of swearing a person into office and thus making that person the incumbent. Such an inauguration commonly occurs through a formal ceremony or special event, which may also include an inaugur ...

as President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

, and ended on March 4, 1881. Hayes became the 19th

19 (nineteen) is the natural number following 18 and preceding 20. It is a prime number.

Mathematics

19 is the eighth prime number, and forms a sexy prime with 13, a twin prime with 17, and a cousin prime with 23. It is the third full re ...

president, after being awarded the closely contested 1876 presidential election by Republicans in Congress who agreed to the Compromise of 1877. That Compromise promised to pull federal troops out of the South, thus ending

Reconstruction. He refused to seek re-election and was succeeded by James A. Garfield

James Abram Garfield (November 19, 1831 – September 19, 1881) was the 20th president of the United States, serving from March 4, 1881 until his death six months latertwo months after he was shot by an assassin. A lawyer and Civil War gene ...

, a fellow Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

and ally.

In general he was a moderate and a pragmatist. He kept the promise to withdraw the last federal troops from the South, as Democrats took control of the last three Republican states. A paragon of honesty, he sponsored civil service reform, where he challenged the patronage hungry Republican politicians. Though he failed to enact long-term reform, he helped generate public support for the eventual passage of the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act

The Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act is a United States federal law passed by the 47th United States Congress and signed into law by President Chester A. Arthur on January 16, 1883. The act mandates that most positions within the federal govern ...

in 1883. The Republican Party in the South grew steadily weaker as his efforts to support the civil rights of blacks in the South were largely stymied by Democrats in Congress.

Insisting that maintenance of the gold standard

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from the l ...

was essential to economic recovery, he opposed Greenbacks (paper money not backed by gold or silver) and vetoed the Bland–Allison Act

The Bland–Allison Act, also referred to as the Grand Bland Plan of 1878, was an act of United States Congress requiring the U.S. Treasury to buy a certain amount of silver and put it into circulation as silver dollars. Though the bill was vetoe ...

that called for more silver in the money supply. Congress overrode his veto, but Hayes's monetary policy forged a compromise between inflationists and advocates of hard money. He used federal troops cautiously to avoid violence in the Great Railroad Strike of 1877

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877, sometimes referred to as the Great Upheaval, began on July 14 in Martinsburg, West Virginia, after the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) cut wages for the third time in a year. This strike finally ended 52 day ...

, one of the largest labor strikes in U.S. history. It marked the end of the economic depression called the "Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the ...

". Prosperity marked the rest of his term. His policy toward Native Americans emphasized minimizing fraud. He continued Grant's "peace plan" and anticipated the assimilationist program of the Dawes Act

The Dawes Act of 1887 (also known as the General Allotment Act or the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887) regulated land rights on tribal territories within the United States. Named after Senator Henry L. Dawes of Massachusetts, it authorized the Pres ...

of 1887. In foreign policy, he was a moderate who took few initiatives. He unsuccessfully opposed the De Lesseps plan for building a Panama Canal, which he thought should be an American only program, Hayes asserted U.S. influence in Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived f ...

and the continuing primacy of the Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine was a United States foreign policy position that opposed European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It held that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign powers was a potentially hostile act ...

. Polls of historians and political scientists generally rank

Rank is the relative position, value, worth, complexity, power, importance, authority, level, etc. of a person or object within a ranking, such as:

Level or position in a hierarchical organization

* Academic rank

* Diplomatic rank

* Hierarchy

* ...

Hayes as an average president.

Election of 1876

Nomination and general election

With the retirement of President

With the retirement of President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

after two terms, the Republicans had to settle on a new candidate for the 1876 election. Hayes's success as Governor of Ohio elevated him to the top ranks of Republican politicians under consideration for the presidency, alongside James G. Blaine of Maine, Senator Oliver P. Morton

Oliver Hazard Perry Throck Morton (August 4, 1823 – November 1, 1877), commonly known as Oliver P. Morton, was a U.S. Republican Party politician from Indiana. He served as the 14th governor (the first native-born) of Indiana during the Amer ...

of Indiana, and Senator Roscoe Conkling

Roscoe Conkling (October 30, 1829April 18, 1888) was an American lawyer and Republican politician who represented New York in the United States House of Representatives and the United States Senate. He is remembered today as the leader of the ...

of New York. The Ohio delegation to the 1876 Republican National Convention was united behind Hayes, and Senator John Sherman

John Sherman (May 10, 1823October 22, 1900) was an American politician from Ohio throughout the Civil War and into the late nineteenth century. A member of the Republican Party, he served in both houses of the U.S. Congress. He also served as ...

did all in his power to aid the nomination of his fellow Ohioan. In June 1876, the Republican National Convention assembled in Hayes's hometown of Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

, with Blaine as the favorite. Hayes placed fifth on the first ballot of the convention, behind Blaine, Morton, Secretary of the Treasury Benjamin Bristow

Benjamin Helm Bristow (June 20, 1832 – June 22, 1896) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 30th U.S. Treasury Secretary and the first Solicitor General.

A Union military officer, Bristow was a Republican Party reformer and ...

, and Conkling. After six ballots, Blaine remained in the lead, but on the seventh ballot, Blaine's adversaries rallied around Hayes, granting him the presidential nomination. For the vice presidency, the convention selected Representative William A. Wheeler, a man about whom Hayes had recently asked, "I am ashamed to say: who is Wheeler?"

Hayes's views were largely in accord with the party platform, which called for equal rights regardless of race or gender, a continuation of Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

, the prohibition of public funding for sectarian schools, and the resumption of specie

Specie may refer to:

* Coins or other metal money in mass circulation

* Bullion coins

* Hard money (policy)

* Commodity money

Commodity money is money whose value comes from a commodity of which it is made. Commodity money consists of objects ...

payments. Hayes's nomination was well received by the press, with even Democratic papers describing Hayes as honest and likable. In a public letter accepting the nomination, Hayes vowed to support civil service reform and pledged to serve for only one term. The Democratic nominee was Samuel J. Tilden, the Governor of New York. Tilden was generally considered to be a formidable adversary and, like Hayes, he had a reputation for honesty. Also, like Hayes, Tilden was a hard-money man and supported civil service reform. In accordance with the custom of the time, the campaign was conducted by surrogates, with Hayes and Tilden remaining in their respective home towns.

The poor economic conditions following the Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the ...

, combined with various Republican scandals, made the party in power unpopular, and Hayes personally believed that he might lose the election. Both candidates focused their attention on the swing states of New York and Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th s ...

, as well as the three Southern states—Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

, South Carolina

)'' Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

, and Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

—where Reconstruction governments still barely ruled amid recurring political violence. The Republicans emphasized the danger of letting Democrats run the nation so soon after the Civil War, which they claimed had been provoked by southern Democrats. To a lesser extent, they also campaigned on the danger a Democratic administration would pose to the recently won civil rights of Southern blacks. Democrats, for their part, trumpeted Tilden's record of reform and contrasted it with the corruption of the incumbent Grant administration. The election was marred by violence in the South, as Redeemers

The Redeemers were a political coalition in the Southern United States during the Reconstruction Era that followed the Civil War. Redeemers were the Southern wing of the Democratic Party. They sought to regain their political power and enforce ...

sought to suppress the black vote.

Post-election dispute

As the returns were tallied on election day, it was clear that the race was close: while Hayes had won much of the North, Tilden had carried most of the South, as well as New York, Indiana,Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its capita ...

, and New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

. On November 11, three days after election day, the 19 electoral votes of Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina were still in doubt. Tilden had won states with a collective total of 184 electoral votes, one short of a majority, while Hayes had won states with 166 electoral votes. Republicans and Democrats each claimed victory in the three disputed states, but the results in those states were rendered uncertain because of fraud by both parties. To further complicate matters, one of the three electors from Oregon

Oregon () is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of its eastern boundary with Idaho. T ...

(a state Hayes had won) was disqualified, reducing Hayes's total to 165, and raising the disputed votes to 20. If Tilden was awarded just one of the disputed electoral votes, he would become president, while a Hayes victory would require him to win all twenty of the disputed votes. With no clear victor in the election, the possibility of mass disorder hung over a country that remained deeply divided in the aftermath of the Civil War.

Electoral Commission

An election commission is a body charged with overseeing the implementation of electioneering process of any country. The formal names of election commissions vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, and may be styled an electoral commission, a c ...

, which would be authorized to determine the fate of the disputed electoral votes. The Commission was to be made up of five representatives, five senators, and five Supreme Court justices. To ensure partisan balance, there would be seven Democrats and seven Republicans, with Justice David Davis, an independent respected by both parties, as the fifteenth member. The balance was upset when Democrats in the Illinois legislature

The Illinois General Assembly is the legislature of the U.S. state of Illinois. It has two chambers, the Illinois House of Representatives and the Illinois Senate. The General Assembly was created by the first state constitution adopted in 18 ...

elected Davis to the Senate, hoping to sway his vote; Davis disappointed Democrats by subsequently refusing to serve on the Electoral Commission As all of the remaining Justices were Republicans, Justice Joseph P. Bradley

Joseph Philo Bradley (March 14, 1813 – January 22, 1892) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1870 to 1892. He was also a member of the Electoral Commission that decided t ...

, believed to be the most independent-minded of them, was selected to take Davis's place on the Commission. The Commission met in February and the eight Republicans voted to award all 20 electoral votes to Hayes.

Despite the Commission's holding, Democrats could still block certification of the election by refusing to convene the House. As the March 4 inauguration day neared, Republican and Democratic Congressional leaders met at Wormley's Hotel in Washington and negotiated a compromise settlement. Republicans promised concessions in exchange for Democratic acquiescence in the Committee's decision. The primary concessions Hayes promised were the withdrawal of federal troops from the South and an acceptance of the election of Democratic governments in the remaining "unredeemed" states of the South. Democrats accepted the compromise, and Hayes was certified as the winner of the election on March 2.

Inauguration

Because March 4, 1877 fell on a Sunday, Hayes took the oath of office privately on Saturday, March 3, in the Red Room of theWhite House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in ...

, becoming the first president to do so in the Executive Mansion. He took the oath publicly on the following Monday on the East Portico of the United States Capitol

The United States Capitol, often called The Capitol or the Capitol Building, is the seat of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, which is formally known as the United States Congress. It is located on Capitol Hill ...

. In his inaugural address, Hayes attempted to soothe the passions of the past few months, saying that "he serves his party best who serves his country best". He pledged to support "wise, honest, and peaceful local self-government" in the South, as well as reform of the civil service and a full return to the gold standard. Despite his message of conciliation, many Democrats never considered Hayes's election legitimate and referred to him as "Rutherfraud" or "His Fraudulency" for the next four years.

Administration

Cabinet

In choosing the members of his cabinet, Hayes spurned

In choosing the members of his cabinet, Hayes spurned Radical Republicans

The Radical Republicans (later also known as "Stalwarts") were a faction within the Republican Party, originating from the party's founding in 1854, some 6 years before the Civil War, until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Recons ...

in favor of moderates, and also disregarded anyone whom he considered a potential presidential contender. He chose William M. Evarts

William Maxwell Evarts (February 6, 1818February 28, 1901) was an American lawyer and statesman from New York who served as U.S. Secretary of State, U.S. Attorney General and U.S. Senator from New York. He was renowned for his skills as a li ...

, who had defended President Andrew Johnson against impeachment, as Secretary of State. George W. McCrary, who had helped establish the Electoral Commission of 1877, became Secretary of War. Carl Schurz, who had supported the Liberal Republican ticket in 1872

Events

January–March

* January 12 – Yohannes IV is crowned Emperor of Ethiopia in Axum, the first ruler crowned in that city in over 500 years.

* February 2 – The government of the United Kingdom buys a number of forts on ...

, was selected as Secretary of the Interior. In an effort to reach out to Southern moderates, Hayes selected David M. Key, a former Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

soldier, to serve as Postmaster General. Senator John Sherman, a close ally and currency issues expert, became Secretary of the Treasury, while Richard W. Thompson

Richard Wigginton Thompson (June 9, 1809 – February 9, 1900) was an American politician.

Thompson was born in Culpeper County, Virginia. He left Virginia in 1831 and lived briefly in Louisville, Kentucky before finally settling in Lawrence Cou ...

was selected as Secretary of the Navy to reward Oliver P. Morton

Oliver Hazard Perry Throck Morton (August 4, 1823 – November 1, 1877), commonly known as Oliver P. Morton, was a U.S. Republican Party politician from Indiana. He served as the 14th governor (the first native-born) of Indiana during the Amer ...

for the latter's support at the 1876 Republican National Convention. The Schurz and Evarts nominations alienated both the Stalwart and the Half-Breed

Half-breed is a term, now considered offensive, used to describe anyone who is of mixed race; although, in the United States, it usually refers to people who are half Native American and half European/white.

Use by governments United States

I ...

factions of the Republican Party, but Hayes's initial cabinet selections won confirmation in the Senate with the help of some Southern Senators.

Lemonade Lucy and the dry White House

Hayes and his wifeLucy

Lucy is an English feminine given name derived from the Latin masculine given name Lucius with the meaning ''as of light'' (''born at dawn or daylight'', maybe also ''shiny'', or ''of light complexion''). Alternative spellings are Luci, Luce, Lu ...

were known for their policy of keeping an alcohol-free White House, giving rise to her nickname "Lemonade Lucy." The first reception at the Hayes White House included wine

Wine is an alcoholic drink typically made from fermented grapes. Yeast consumes the sugar in the grapes and converts it to ethanol and carbon dioxide, releasing heat in the process. Different varieties of grapes and strains of yeasts are m ...

, but Hayes was dismayed at drunken behavior at receptions hosted by ambassadors around Washington. After the first reception, alcohol was not served again in the Hayes White House. Critics charged Hayes with parsimony, but Hayes spent more money (which came out of his personal budget) after the ban, ordering that any savings from eliminating alcohol be used on more lavish entertainment. His temperance policy also paid political dividends, strengthening his support among Protestant ministers. Although Secretary Evarts quipped that at the White House dinners, "water flowed like wine," the policy was a success in convincing prohibitionists

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic ...

to vote Republican.

Judicial appointments

Hayes appointed two

Hayes appointed two associate justices

Associate justice or associate judge (or simply associate) is a judicial panel member who is not the chief justice in some jurisdictions. The title "Associate Justice" is used for members of the Supreme Court of the United States and some state ...

to the Supreme Court. The first Supreme Court vacancy arose after David Davis resigned during the election controversy of 1876. On taking office, Hayes filled the vacancy caused by Davis's resignation by appointing John Marshall Harlan

John Marshall Harlan (June 1, 1833 – October 14, 1911) was an American lawyer and politician who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1877 until his death in 1911. He is often called "The Great Dissenter" due to his ...

, a close ally of Benjamin Bristow. Hayes submitted the nomination in October 1877, but the nomination aroused some dissent in the Senate because of Harlan's limited experience in public office. Harlan was nonetheless confirmed and served on the court for thirty-four years, in which he voted (usually in the minority) for an aggressive enforcement of civil rights laws. In 1880, a second seat became vacant upon the resignation of Justice William Strong. Hayes nominated William Burnham Woods, a carpetbagger Republican circuit court judge from Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,765 ...

. Woods served six years on the Court, ultimately proving a disappointment to Hayes as he interpreted the Constitution in a manner more similar to that of Southern Democrats than to Hayes's own preferences.

Hayes attempted, unsuccessfully, to fill a third vacancy in 1881. Justice Noah Haynes Swayne

Noah Haynes Swayne (December 7, 1804 – June 8, 1884) was an American jurist and politician. He was the first Republican appointed as a justice to the United States Supreme Court.

Birth and early life

Swayne was born in Frederick County, Vir ...

resigned with the expectation that Hayes would fill his seat by appointing Stanley Matthews

Sir Stanley Matthews, CBE (1 February 1915 – 23 February 2000) was an English footballer who played as an outside right. Often regarded as one of the greatest players of the British game, he is the only player to have been knighted while sti ...

, who was a friend of both men. Many Senators objected to the appointment, believing that Matthews was too close to corporate and railroad interests, especially those of Jay Gould

Jason Gould (; May 27, 1836 – December 2, 1892) was an American railroad magnate and financial speculator who is generally identified as one of the robber barons of the Gilded Age. His sharp and often unscrupulous business practices made him ...

. The Senate adjourned without voting on the nomination, but newly-elected President James A. Garfield

James Abram Garfield (November 19, 1831 – September 19, 1881) was the 20th president of the United States, serving from March 4, 1881 until his death six months latertwo months after he was shot by an assassin. A lawyer and Civil War gene ...

re-submitted Matthews's nomination to the Senate, and Matthews was confirmed by a one vote margin. Matthews served for eight years until his death in 1889. His opinion in '' Yick Wo v. Hopkins'' in 1886 advanced his and Hayes' views on the protection of ethnic minorities' rights.

In addition to his Supreme Court appointments, Hayes appointed four judges to the United States circuit court

The United States circuit courts were the original intermediate level courts of the United States federal court system. They were established by the Judiciary Act of 1789. They had trial court jurisdiction over civil suits of diversity jurisdic ...

s and sixteen judges to the United States district courts

The United States district courts are the trial courts of the U.S. federal judiciary. There is one district court for each federal judicial district, which each cover one U.S. state or, in some cases, a portion of a state. Each district cou ...

.

End of Reconstruction

Withdrawal from the South

When Hayes assumed office, only two Reconstruction governments remained, in South Carolina and Louisiana. Hayes had been a firm supporter of Republican Reconstruction policies throughout his political career, but the first major act of his presidency was to end Reconstruction and return the South to "home rule." In South Carolina, Hayes withdrew federal soldiers on April 10, 1877, after GovernorWade Hampton III

Wade Hampton III (March 28, 1818April 11, 1902) was an American military officer who served the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War and later a politician from South Carolina. He came from a wealthy planter family, and ...

promised to respect the civil rights of African Americans. In Louisiana, Hayes appointed a commission to mediate between the rival governments of Republican Stephen B. Packard and Democrat Francis T. Nicholls. The commission chose to support Nicholls's government, and Hayes ended Reconstruction in Louisiana, and the country as a whole, on April 20, 1877.

Some Republicans, such as Blaine, strongly criticized the end of Reconstruction. However, even without the conditions of the disputed 1876 election, Hayes would have been hard-pressed to continue the policies of his predecessors. The House of Representatives in the 45th Congress was controlled by the Democratic Party, and the Democrats refused to appropriate enough funds for the army to continue to garrison the South. Even among Republicans, devotion to continued military Reconstruction was fading in the face of persistent Southern insurgency and violence.

Voting Rights

Democrats consolidated their control in the South in the 1878 mid-term elections, creating a voting bloc known as theSolid South

The Solid South or Southern bloc was the electoral voting bloc of the states of the Southern United States for issues that were regarded as particularly important to the interests of Democrats in those states. The Southern bloc existed especial ...

. Just three of the 73 Representatives elected by the former Confederate states were members of the Republican Party. Democrats also took control of the Senate in the 1878 elections, and the new Democratic Congress immediately sought to strip away the remaining federal influence in the South.

The Democratic Congress passed an army appropriations bill in 1879 with a rider that repealed the Enforcement Acts, which had been used to suppress the Ku Klux Klan. Those acts, passed during Reconstruction, made it a crime to prevent someone from voting because of his race. Hayes was determined to preserve the law protecting black voters, and he vetoed the appropriation. The Democrats did not have enough votes to override the veto, but they passed a new bill with the same rider. Hayes vetoed this as well, and the process was repeated three times more. Finally, Hayes signed an appropriation without the offensive rider. Congress refused to pass another bill to fund federal marshals, who were vital to the enforcement of the Enforcement Acts. The election laws remained in effect, though the funds to enforce them were curtailed. Hayes's strong stance against the Democratic attempts to repeal the election laws earned him the support of civil rights advocates in the North and boosted his popularity among some Republicans who had been alienated by his civil service reform efforts.

Hayes tried to reconcile the social mores of the South with the civil rights laws by distributing patronage among Southern Democrats. "My task was to wipe out the color line, to abolish sectionalism, to end the war and bring peace," he wrote in his diary. "To do this, I was ready to resort to unusual measures and to risk my own standing and reputation within my party and the country." He also sought to build up a strong Republican Party in the South that appealed to both whites and blacks. All of his efforts were in vain; Hayes failed to convince the South to accept the idea of racial equality and failed to convince Congress to appropriate funds to enforce the civil rights laws. In the ensuing years and decades, African Americans would be almost completely disenfranchised.

National leadership

In the aftermath of the 1876 presidential election, power in national politics was very closely balanced. The Senate in 1877 contained 39 Republicans, 36 Democrats, and one independent, while the Democrats controlled the House of Representatives by the slim margin of 153 to 140. There were very few troublemakers or demagogues on either side as both parties saw the need to compromise and relax the heightened political tensions following the 1876 election. The economy had now recovered from the harsh depression that ended in 1873, and the nation welcomed economic expansion, farm prosperity, and the entrepreneurship that was building great industries such as iron and steel and petroleum. Historian Richard White most recently has emphasized the "Quest for Prosperity" that characterized the Gilded Age after Reconstruction ended.Civil service reform

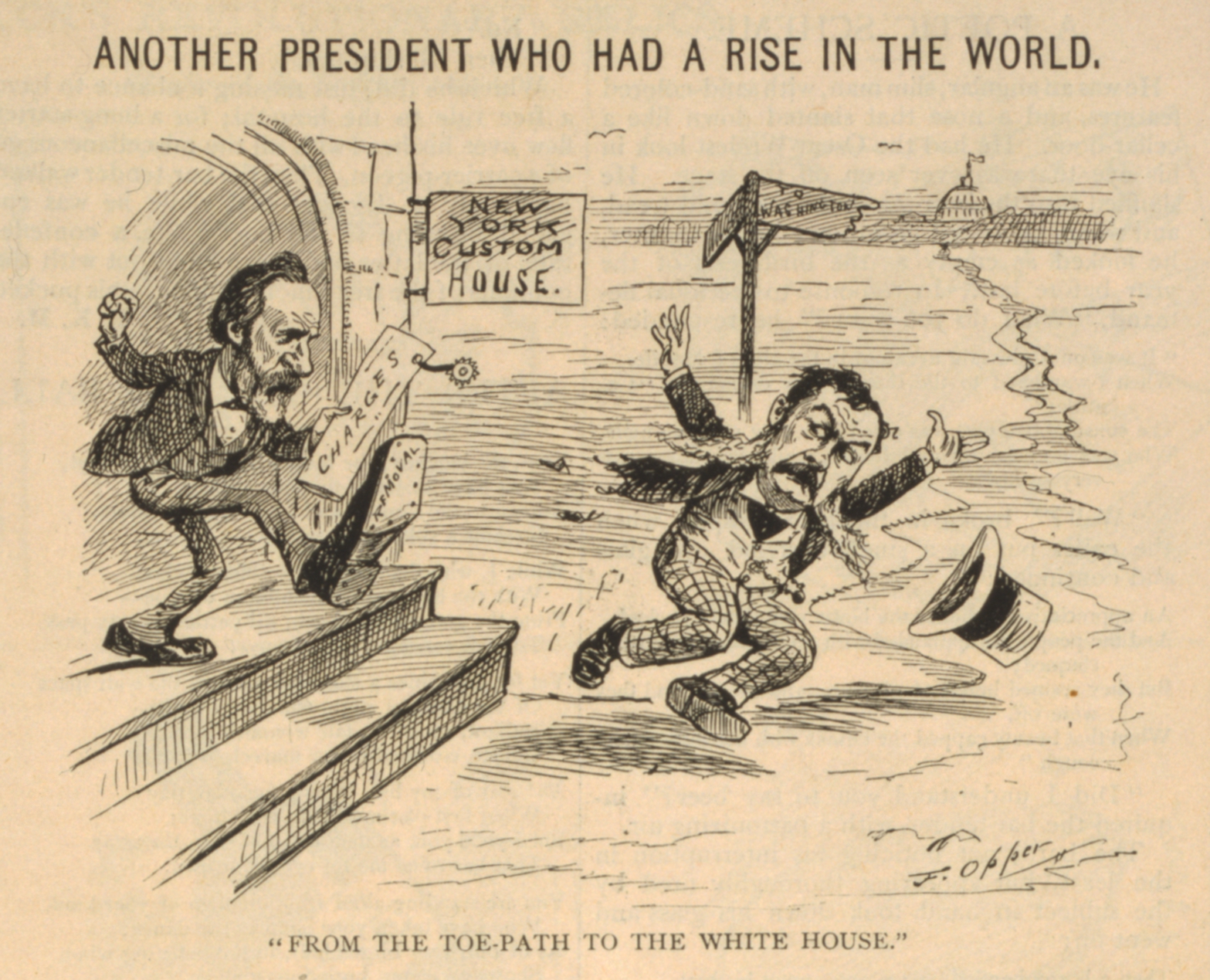

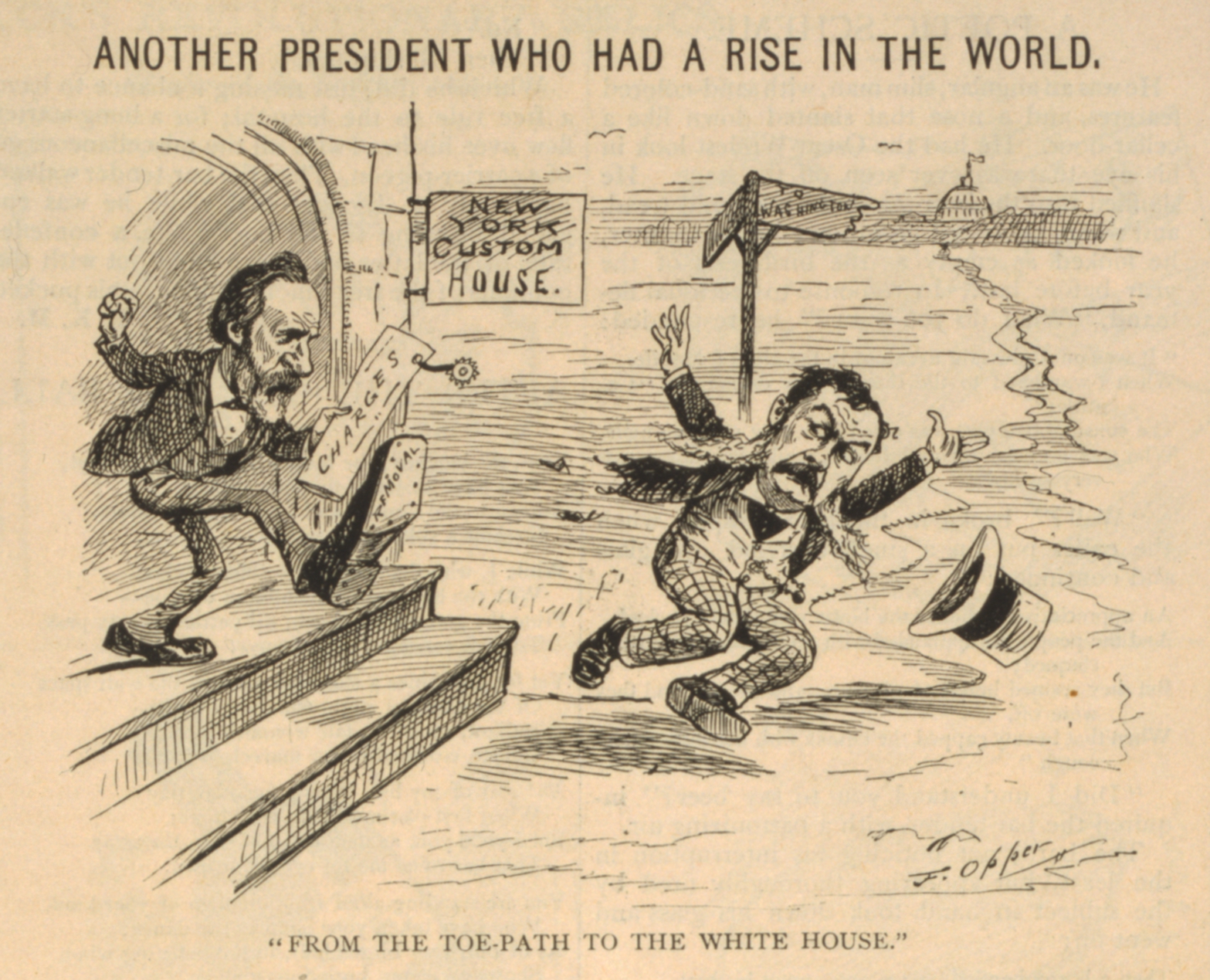

After ending Reconstruction, Hayes turned to the issue of civil service reform. Instead of giving federal jobs to political supporters or the favorites of powerful members of Congress, Hayes favored appointment based on performance in

After ending Reconstruction, Hayes turned to the issue of civil service reform. Instead of giving federal jobs to political supporters or the favorites of powerful members of Congress, Hayes favored appointment based on performance in civil service examination

Civil service examinations are examinations implemented in various countries for recruitment and admission to the civil service. They are intended as a method to achieve an effective, rational public administration on a merit system for recruitin ...

s. To show his commitment to reform, Hayes asked Secretary of the Interior Schurz and Secretary of State Evarts to lead a special cabinet committee charged with drawing up new rules for federal appointments. Senators of both parties who were accustomed to being consulted about political appointments turned against Hayes. Hayes's efforts for reform brought him into conflict with the Stalwart, or pro-spoils, branch of the Republican party, led by Senator Roscoe Conkling

Roscoe Conkling (October 30, 1829April 18, 1888) was an American lawyer and Republican politician who represented New York in the United States House of Representatives and the United States Senate. He is remembered today as the leader of the ...

of New York. Treasury Secretary Sherman ordered John Jay

John Jay (December 12, 1745 – May 17, 1829) was an American statesman, patriot, diplomat, abolitionist, signatory of the Treaty of Paris, and a Founding Father of the United States. He served as the second governor of New York and the f ...

to investigate the New York Custom House, which was stacked with Conkling's spoilsmen. Jay's report suggested that the New York Custom House was so overstaffed with political appointees and that 20 percent of the employees were expendable.

With Congress unwilling to take action on civil service reform, Hayes issued an executive order

In the United States, an executive order is a directive by the president of the United States that manages operations of the federal government. The legal or constitutional basis for executive orders has multiple sources. Article Two of t ...

that forbade federal office holders from being required to make campaign contributions or otherwise taking part in party politics. Chester A. Arthur

Chester Alan Arthur (October 5, 1829 – November 18, 1886) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 21st president of the United States from 1881 to 1885. He previously served as the 20th vice president under President James ...

, the Collector of the Port of New York

The Collector of Customs at the Port of New York, most often referred to as Collector of the Port of New York, was a federal officer who was in charge of the collection of import duties on foreign goods that entered the United States by ship at t ...

, and his subordinates Alonzo B. Cornell

Alonzo Barton Cornell (January 22, 1832 – October 15, 1904) was a New York (state), New York politician and businessman who was the List of Governors of New York, 27th Governor of New York from 1880 to 1882.

Early years

Cornell was born i ...

and George H. Sharpe, all Conkling supporters, refused to obey the president's order. In September 1877, Hayes demanded the three men's resignations, which they refused to give. He submitted appointments of Theodore Roosevelt Sr., L. Bradford Prince

LeBaron Bradford Prince (July 3, 1840December 8, 1922) was an American lawyer and politician who served as chief justice of the New Mexico Territorial Supreme Court from 1878 to 1882, and as the 14th Governor of New Mexico Territory from 1889 to ...

, and Edwin Merritt—all supporters of Secretary of State Evarts, Conkling's New York rival—to the Senate for confirmation as their replacements. The Senate Commerce Committee, which Conkling chaired, voted unanimously to reject the nominees, and the full Senate rejected Roosevelt and Prince by a vote of 31–25, confirming Merritt only because Sharpe's term had expired. Hayes was forced to wait until July 1878 when, during a Congressional recess, he sacked Arthur and Cornell and replaced them with recess appointment

In the United States, a recess appointment is an appointment by the president of a federal official when the U.S. Senate is in recess. Under the U.S. Constitution's Appointments Clause, the President is empowered to nominate, and with the a ...

s of Merritt and Silas W. Burt, respectively. Conkling opposed the appointees' confirmation when the Senate reconvened in February 1879, but Merritt was approved by a vote of 31–25, as was Burt by a 31–19 vote, giving Hayes his most significant civil service reform victory.

For the remainder of his term, Hayes pressed Congress to enact permanent reform legislation and fund the United States Civil Service Commission

The United States Civil Service Commission was a government agency of the federal government of the United States and was created to select employees of federal government on merit rather than relationships. In 1979, it was dissolved as part of t ...

, even using his last annual message to Congress in 1880 to appeal for reform. While reform legislation did not pass during Hayes's presidency, his advocacy provided the "political impetus" for the 1883 passage of the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act

The Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act is a United States federal law passed by the 47th United States Congress and signed into law by President Chester A. Arthur on January 16, 1883. The act mandates that most positions within the federal govern ...

. Hayes allowed some exceptions to the ban on assessments, permitting George Congdon Gorham, secretary of the Republican Congressional Committee, to solicit campaign contributions from federal office-holders during the Congressional elections of 1878. In 1880, Hayes quickly forced Secretary of Navy Richard W. Thompson

Richard Wigginton Thompson (June 9, 1809 – February 9, 1900) was an American politician.

Thompson was born in Culpeper County, Virginia. He left Virginia in 1831 and lived briefly in Louisville, Kentucky before finally settling in Lawrence Cou ...

to resign office after Thompson had accepted a $25,000 salary for a nominal job offered by French engineer Ferdinand de Lesseps

Ferdinand Marie, Comte de Lesseps (; 19 November 1805 – 7 December 1894) was a French diplomat and later developer of the Suez Canal, which in 1869 joined the Mediterranean and Red Seas, substantially reducing sailing distances and times ...

to promote a French canal in Panama.

Hayes also dealt with corruption in the postal service. In 1880, Schurz and Senator John A. Logan

John Alexander Logan (February 9, 1826 – December 26, 1886) was an American soldier and politician. He served in the Mexican–American War and was a general in the Union Army in the American Civil War. He served the state of Illinois as a st ...

asked Hayes to shut down the " star route" rings, a system of corrupt contract profiteering in the Postal Service, and to fire Second Assistant Postmaster-General Thomas J. Brady, the alleged ring leader. Hayes stopped granting new star route contracts, but let existing contracts continue to be enforced. Democrats accused Hayes of delaying proper investigation so as not to injure Republican chances in the 1880 elections but did not press the issue in their campaign literature, as members of both parties were implicated in the corruption. Historian Hans L. Trefousse writes that the president "hardly knew the chief suspect radyand certainly had no connection with the tar routecorruption." Although Hayes and the Congress both investigated the contracts and found no compelling evidence of wrongdoing, Brady and others were indicted for conspiracy in 1882. After two trials, the defendants were found not guilty in 1883.

1877 railroad strike

In his first year in office, Hayes was faced with the

In his first year in office, Hayes was faced with the Great Railroad Strike of 1877

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877, sometimes referred to as the Great Upheaval, began on July 14 in Martinsburg, West Virginia, after the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) cut wages for the third time in a year. This strike finally ended 52 day ...

, the largest labor disturbance up to that point in U.S. history. In order to make up for financial losses suffered since the Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the ...

, the major railroads had cut their employees' wages several times. The Pennsylvania Railroad, one of the largest railroads, reduced the average worker's pay by approximately 25% between 1873 and 1877, and the railroad also imposed longer hours and stricter managerial control. In July 1877, workers from the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the first common carrier railroad and the oldest railroad in the United States, with its first section opening in 1830. Merchants from Baltimore, which had benefited to some extent from the construction of ...

walked off the job in Martinsburg, West Virginia

Martinsburg is a city in and the seat of Berkeley County, West Virginia, in the tip of the state's Eastern Panhandle region in the lower Shenandoah Valley. Its population was 18,835 in the 2021 census estimate, making it the largest city in the E ...

, to protest their reduction in pay. The strike

Strike may refer to:

People

* Strike (surname)

Physical confrontation or removal

*Strike (attack), attack with an inanimate object or a part of the human body intended to cause harm

*Airstrike, military strike by air forces on either a suspected ...

quickly spread to workers of the New York Central, Erie

Erie (; ) is a city on the south shore of Lake Erie and the county seat of Erie County, Pennsylvania, United States. Erie is the fifth largest city in Pennsylvania and the largest city in Northwestern Pennsylvania with a population of 94,831 a ...

, and Pennsylvania railroads, with the strikers soon numbering in the thousands. In many communities, friends and family members of the railroad workers also became involved in the strike, and strike leaders struggled to control crowds. Fearing a riot, Governor Henry M. Mathews asked Hayes to send federal troops to Martinsburg, and Hayes did so, but when the troops arrived there was no riot, only a peaceful protest. In Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

, however, a riot did erupt on July 20 and Hayes ordered the troops at Fort McHenry

Fort McHenry is a historical American coastal pentagonal bastion fort on Locust Point, now a neighborhood of Baltimore, Maryland. It is best known for its role in the War of 1812, when it successfully defended Baltimore Harbor from an attack ...

to assist the governor in its suppression.

Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Western Pennsylvania, the second-most populous city in Pennsylva ...

next exploded into riots, but Hayes was reluctant to send in troops without the governor first requesting them. Other discontented citizens joined the railroad workers in rioting. After a few days, Hayes resolved to send in troops to protect federal property wherever it appeared to be threatened and gave Major General Winfield Scott Hancock

Winfield Scott Hancock (February 14, 1824 – February 9, 1886) was a United States Army officer and the Democratic nominee for President of the United States in 1880. He served with distinction in the Army for four decades, including service ...

overall command of the situation. The riot spread to Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

and St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

, where the Workingmen's Party

The Workingmen's Party of the United States (WPUS), established in 1876, was one of the first Marxist-influenced political parties in the United States. It is remembered as the forerunner of the Socialist Labor Party of America.

Organizational ...

organized a brief general strike. As the rioting spread, some began to fear a nationwide radical revolution inspired by the Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (french: Commune de Paris, ) was a revolutionary government that seized power in Paris, the capital of France, from 18 March to 28 May 1871.

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard had defended ...

. This fear did not come to pass, as by the end of July 1877, state, local, and federal authorities had brought the labor disturbances to an end. Although no federal troops had killed any of the strikers, or been killed themselves, clashes between state militia troops and strikers resulted in deaths on both sides.

The railroads were victorious in the short term, as the workers returned to their jobs and some wage cuts remained in effect. But the public blamed the railroads for the strikes and violence, and the railroads were compelled to improve working conditions and make no further cuts. Business leaders praised Hayes, but his own opinion was more equivocal; as he recorded in his diary: "The strikes have been put down by ''force;'' but now for the ''real'' remedy. Can't something edone by education of strikers, by judicious control of capitalists, by wise general policy to end or diminish the evil? The railroad strikers, as a rule, are good men, sober, intelligent, and industrious." Hayes was the first president to deploy the U.S. Army to intervene in a labor dispute in the states. In response to the strike and the deployment of federal soldiers, Congress passed the Posse Comitatus Act

The Posse Comitatus Act is a United States federal law (, original at ) signed on June 18, 1878, by President Rutherford B. Hayes which limits the powers of the federal government in the use of federal military personnel to enforce domestic p ...

, which limits the use of military personnel in resolving domestic disturbances.Women's Rights

The suffragette movement had been growing for many years prior to the presidency of Hayes. Although the issue of suffrage would not be resolved during the Hayes's tenure, another, albeit smaller issue would be. Prior to Hayes' ascension, a Belva Lockwood had attempted to be admitted to the supreme court bar. She had been rejected, not on grounds of merit or qualification, but due to her sex. She appealed to members of congress for legislation that, if enacted, would remove this type of barrier and allow for qualified women to submit and argue cases before the Supreme Court. After much debate, in 1879, congress passed, and Hayes signed into law the Act to Relieve Certain Legal Disabilities of Women, popularly known as the Lockwood Bill. Lockwood would go on to argue a number of cases in front of the court, and win one in 1906.Indian policy

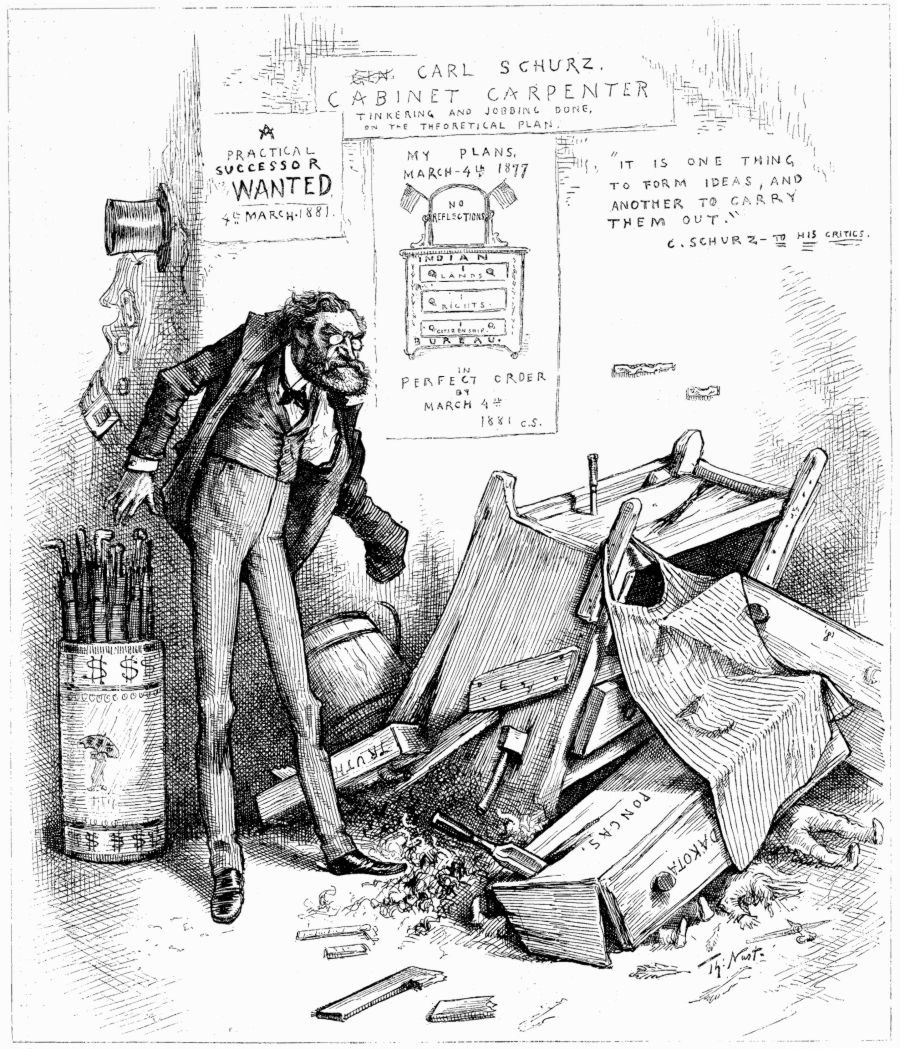

Interior Secretary Schurz carried out Hayes's American Indian policy, beginning with preventing the

Interior Secretary Schurz carried out Hayes's American Indian policy, beginning with preventing the War Department War Department may refer to:

* War Department (United Kingdom)

* United States Department of War (1789–1947)

See also

* War Office, a former department of the British Government

* Ministry of defence

* Ministry of War

* Ministry of Defence

* D ...

from taking over the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Hayes and Schurz carried out a policy that included assimilation into white culture, educational training, and dividing Indian land into individual household allotments. Hayes believed that his policies would lead to self-sufficiency and peace between Indians and whites. The allotment system was favored by liberal reformers at the time, including Schurz, but instead proved detrimental to American Indians. They lost much of their land through later sales to unscrupulous white speculators

In finance, speculation is the purchase of an asset (a commodity, goods, or real estate) with the hope that it will become more valuable shortly. (It can also refer to short sales in which the speculator hopes for a decline in value.)

Many s ...

. Hayes and Schurz reformed the Bureau of Indian Affairs to reduce fraud and gave Indians responsibility for policing their understaffed reservations.

Hayes dealt with several conflicts with Indian tribes. The Nez Perce

The Nez Percé (; autonym in Nez Perce language: , meaning "we, the people") are an Indigenous people of the Plateau who are presumed to have lived on the Columbia River Plateau in the Pacific Northwest region for at least 11,500 years.Ames, K ...

, led by Chief Joseph

''Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekt'' (or ''Hinmatóowyalahtq̓it'' in Americanist orthography), popularly known as Chief Joseph, Young Joseph, or Joseph the Younger (March 3, 1840 – September 21, 1904), was a leader of the Wal-lam-wat-kain (Wallowa ...

, began an uprising in June 1877 when Major General Oliver O. Howard ordered them to move on to a reservation. Howard's men defeated the Nez Perce in battle, and the tribe began a 1700-mile retreat into Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

. In October, after a decisive battle at Bear Paw, Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columb ...

, Chief Joseph surrendered and General William T. Sherman

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

ordered the tribe transported to Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to th ...

, where they were forced to remain until 1885. The Nez Perce war was not the last conflict in the West, as the Bannock

Bannock may mean:

* Bannock (food), a kind of bread, cooked on a stone or griddle

* Bannock (Indigenous American), various types of bread, usually prepared by pan-frying

* Bannock people, a Native American people of what is now southeastern Oregon ...

rose up in Spring 1878 and raided nearby settlements before being defeated by Howard's army in July of that year. War with the Ute tribe

Ute () are the Indigenous people of the Ute tribe and culture among the Indigenous peoples of the Great Basin. They had lived in sovereignty in the regions of present-day Utah and Colorado in the Southwestern United States for many centuries unt ...

broke out in 1879 when the Utes killed Indian agent Nathan Meeker

Nathan Cook Meeker (July 12, 1817 – September 30, 1879) was a 19th-century American journalist, homesteader, entrepreneur, and Indian agent for the federal government. He is noted for his founding in 1870 of the Union Colony, a cooperative ...

, who had been attempting to convert them to Christianity. The subsequent White River War ended when Schurz negotiated peace with the Ute and prevented the white Coloradans from taking revenge for Meeker's death.

Hayes also became involved in resolving the removal of the Ponca

The Ponca ( Páⁿka iyé: Páⁿka or Ppáⁿkka pronounced ) are a Midwestern Native American tribe of the Dhegihan branch of the Siouan language group. There are two federally recognized Ponca tribes: the Ponca Tribe of Nebraska and the Ponca ...

tribe from Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the sout ...

to Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title to their land as a sovereign ...

(present-day Oklahoma) because of a misunderstanding during the Grant Administration. The tribe's problems came to Hayes's attention after their chief, Standing Bear

Standing Bear (c. 1829–1908) (Ponca official orthography: Maⁿchú-Naⁿzhíⁿ/Macunajin;U.S. Indian Census Rolls, 1885 Ponca Indians of Dakota other spellings: Ma-chú-nu-zhe, Ma-chú-na-zhe or Mantcunanjin pronounced ) was a Ponca chief a ...

, filed a lawsuit to contest Schurz's demand that they stay in Indian Territory. Overruling Schurz, Hayes set up a commission in 1880 that ruled Ponca were free to return to Nebraska or stay on their reservation in Indian Territory. The Ponca were awarded compensation for their land rights, which had been previously granted to the Sioux. In a message to Congress in February 1881, Hayes insisted he would "give to these injured people that measure of redress which is required alike by justice and by humanity."

Finance and economics

Currency debate

The

The Coinage Act of 1873

The Coinage Act of 1873 or Mint Act of 1873, was a general revision of laws relating to the Mint of the United States. By ending the right of holders of silver bullion to have it coined into standard silver dollars, while allowing holders of go ...

had stopped the coinage of silver for all coins worth a dollar or more, effectively tying the dollar to the value of gold. As a result, the money supply contracted and the effects of the Panic of 1873 grew worse, making it more expensive for debtors to pay debts they had contracted when currency was less valuable. Farmers and laborers, especially, clamored for the return of coinage in both metals, believing the increased money supply would restore wages and property values. Democratic Representative Richard P. Bland of Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

proposed a bill that would require the United States to coin as much silver as miners could sell to the government, thus increasing the money supply and aiding debtors. William B. Allison

William Boyd Allison (March 2, 1829 – August 4, 1908) was an American politician. An early leader of the Iowa Republican Party, he represented northeastern Iowa in the United States House of Representatives before representing his state in th ...

, a Republican from Iowa

Iowa () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wisconsin to the northeast, Illinois to th ...

offered an amendment in the Senate limiting the coinage to two to four million dollars per month, and the resulting Bland–Allison Act

The Bland–Allison Act, also referred to as the Grand Bland Plan of 1878, was an act of United States Congress requiring the U.S. Treasury to buy a certain amount of silver and put it into circulation as silver dollars. Though the bill was vetoe ...

passed both houses of Congress in 1878.

Hayes feared that the Bland–Allison Act would cause inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reduct ...

that would be ruinous to business, effectively impairing contracts that were based on the gold dollar, as the silver dollar proposed in the bill would have an intrinsic value of 90 to 92 percent of the existing gold dollar. Further, Hayes believed that inflating the currency was an act of dishonesty, saying " pediency and justice both demand an honest currency." He vetoed the bill, but Congress overrode his veto, the only time it did so during his presidency. As the Bland–Allison Act gave the president discretion in determining the number of silver coins minted, Hayes limited the effect of the act by authorizing the coining of only a relatively small number of silver coins.

During the Civil War, the federal government had issued United States Notes (commonly called greenbacks), a form of fiat currency. The government accepted these notes as valid for payment of taxes and tariffs, but unlike ordinary dollars, they were not redeemable in gold. The Specie Payment Resumption Act The Specie Payment Resumption Act of January 14, 1875 was a law in the United States that restored the nation to the gold standard through the redemption of previously-unbacked United States Notes and reversed inflationary government policies promot ...

of 1875 required the treasury to redeem any outstanding greenbacks in gold, thus retiring them from circulation and restoring the gold standard

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from the l ...

. Hayes and Secretary of the Treasury Sherman both support a restoration of the gold standard, and the Hayes administration stockpiled gold in preparation for the exchange of greenbacks for gold. Once the public was confident that they could redeem greenbacks for specie (gold), however, few did so; when the act took effect in 1879, only $130,000 out of the $346,000,000 outstanding dollars in greenbacks were actually redeemed. Together with the Bland–Allison Act, the successful specie resumption effected a workable compromise between inflationists and hard money men. As the world economy began to improve, agitation for more greenbacks and silver coinage quieted down for the rest of Hayes's term in office.

Pensions and tariffs

In 1861, Congress had significantly raisedtariffs

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and po ...

with the passage of the Morrill Tariff, which funded the Civil War and also protected

Protection is any measure taken to guard a thing against damage caused by outside forces. Protection can be provided to physical objects, including organisms, to systems, and to intangible things like civil and political rights. Although th ...

American industries like iron and steel. The high rates of the Morrill Tariff remained in effect in the 1870s, leading to a federal budgetary surplus. Though the tariff was politically popular in the industrialized Northeast, it had many detractors in the South and Midwest, as high tariff rates led to higher prices. Seeking to shore up the tariff's popularity, Senator Henry W. Blair

Henry William Blair (December 6, 1834March 14, 1920) was a United States representative and Senator from New Hampshire. During the American Civil War, he was a Lieutenant Colonel in the Union Army.

A Radical Republican in his earlier political ...

proposed the Arrears Act, which Hayes signed in 1879. The Arrears Act expanded the pension system designed to benefit Union Civil War veterans by making pension payments retroactive to a soldier's discharge or death rather than the date of their application. In practice, this meant sending large checks to veterans and their families, and pension disbursements doubled between 1879 and 1881. The act proved extremely popular outside of the South and spread support for Republicans and high tariff rates.

Foreign affairs

Panamanian Canal

Hayes was perturbed over the plans ofFerdinand de Lesseps

Ferdinand Marie, Comte de Lesseps (; 19 November 1805 – 7 December 1894) was a French diplomat and later developer of the Suez Canal, which in 1869 joined the Mediterranean and Red Seas, substantially reducing sailing distances and times ...

, the builder of the Suez Canal, to construct a canal across the Isthmus of Panama, which was then owned by Colombia. Concerned about a repetition of French adventurism in Mexico, Hayes interpreted the Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine was a United States foreign policy position that opposed European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It held that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign powers was a potentially hostile act ...

firmly. In a message to Congress, Hayes explained his opinion on the canal: "The policy of this country is a canal under American control ... The United States cannot consent to the surrender of this control to any European power or any combination of European powers." De Lesseps went ahead anyway, raised very large sums, and began construction. Disease ravaged his workforce, and his project collapsed in corruption and incompetence.

Mexico

Throughout the 1870s, "lawless bands" often crossed theMexican border

Mexico shares international borders with three nations:

*To the north the United States–Mexico border, which extends for a length of through the states of Baja California, Sonora, Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo León and Tamaulipas.

*To the southe ...

on raids into Texas. Three months after taking office, Hayes granted the Army the power to pursue bandit

Banditry is a type of organized crime committed by outlaws typically involving the threat or use of violence. A person who engages in banditry is known as a bandit and primarily commits crimes such as extortion, robbery, and murder, either as an ...

s, even if it required crossing into Mexican territory. Porfirio Díaz, the Mexican president, protested the order and sent troops to the border. The situation calmed as Díaz and Hayes agreed to jointly pursue bandits and Hayes agreed not to allow Mexican revolutionaries to raise armies in the United States. The violence along the border decreased, and in 1880 Hayes revoked the order allowing pursuit into Mexico.

Chinese immigration

The Hayes administration gave significant attention to U.S.–China relations as Chinese immigration became a contentious issue during Hayes's presidency. In 1868, the Senate had ratified theBurlingame Treaty

The Burlingame Treaty (), also known as the Burlingame–Seward Treaty of 1868, was a landmark treaty between the United States and Qing China, amending the Treaty of Tientsin, to establish formal friendly relations between the two nations, with ...

with China, allowing an unrestricted flow of Chinese immigrants

Overseas Chinese () refers to people of Chinese birth or ethnicity who reside outside Mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan. As of 2011, there were over 40.3 million overseas Chinese.

Terminology

() or ''Hoan-kheh'' () in Hokkien, ref ...

into the country. As the economy soured after the Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the ...

, Chinese immigrants were blamed for depressing workmen's wages. During the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, anti-Chinese riots broke out in San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17th ...

, and a third party

Third party may refer to:

Business

* Third-party source, a supplier company not owned by the buyer or seller

* Third-party beneficiary, a person who could sue on a contract, despite not being an active party

* Third-party insurance, such as a V ...

, the Workingman's Party

The Workingmen's Party of California (WPC) was an American labor organization, founded in 1877 and led by Denis Kearney, J.G Day, and H. L. Knight.

Organizational history

As a result of heavy unemployment from the 1873-78 national depression, ...

, was formed with an emphasis on stopping Chinese immigration. In response, Congress passed a measure, the "Fifteen Passenger Bill" in 1879, aimed at limiting the number of Chinese passengers permitted on vessels arriving at U.S. ports. As the legislation would violate the terms of the Burlingame Treaty, Hayes, believing that the United States should not unilaterally abrogate treaties, vetoed it. The veto drew praise among eastern liberals, but Hayes was bitterly denounced in the West. In the subsequent furor, Democrats in the House of Representatives attempted to impeach him, but narrowly failed when Republicans prevented a quorum by refusing to vote. After the veto, Assistant Secretary of State Assistant Secretary of State (A/S) is a title used for many executive positions in the United States Department of State, ranking below the under secretaries. A set of six assistant secretaries reporting to the under secretary for political affairs ...

Frederick W. Seward

Frederick William Seward (July 8, 1830 – April 25, 1915) was an American politician and member of the Republican Party who twice served as the Assistant Secretary of State. The son of United States Secretary of State William H. Seward, ...

and James Burrill Angell

James Burrill Angell (January 7, 1829 – April 1, 1916) was an American educator and diplomat. He is best known for being the longest-serving president of the University of Michigan, from 1871 to 1909. He represented the transition from sma ...

negotiated with the Chinese to reduce the number of Chinese immigrants. The resulting accord, the Angell Treaty of 1880

The Angell Treaty of 1880 (), formally known as the Treaty Regulating Immigration from China, was a modification of the 1868 Burlingame Treaty between the United States and China, passed in Beijing, China, on November 17, 1880.

Historical con ...

, allowed the U.S. to suspend Chinese immigration, which Congress did (after Hayes left office) with the Chinese Exclusion Act

The Chinese Exclusion Act was a United States federal law signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882, prohibiting all immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years. The law excluded merchants, teachers, students, travelers, and diplo ...

of 1882.

Other issues

In 1878, following theParaguayan War

The Paraguayan War, also known as the War of the Triple Alliance, was a South American war that lasted from 1864 to 1870. It was fought between Paraguay and the Triple Alliance of Argentina, the Empire of Brazil, and Uruguay. It was the deadlies ...

, the president arbitrated a territorial dispute between Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

and Paraguay

Paraguay (; ), officially the Republic of Paraguay ( es, República del Paraguay, links=no; gn, Tavakuairetã Paraguái, links=si), is a landlocked country in South America. It is bordered by Argentina to the south and southwest, Brazil to th ...

. Hayes awarded the disputed land in the Gran Chaco

The Gran Chaco or Dry Chaco is a sparsely populated, hot and semiarid lowland natural region of the Río de la Plata basin, divided among eastern Bolivia, western Paraguay, northern Argentina, and a portion of the Brazilian states of Mato ...

region to Paraguay, and the Paraguayans honored him by renaming a city (Villa Hayes

Villa Hayes () is a city in Paraguay, and is the capital of Presidente Hayes Department.

Name

Known as "the City of the Five Names", it was eventually named in honor of Rutherford B. Hayes, 19th President of the United States.

Weather

The c ...

) and a department as ( Presidente Hayes) in his honor. The administration sought friendly relations with the major European powers, though not to the detriment of the Monroe Doctrine. Hayes upheld the Treaty of Washington, ending the dispute with Great Britain caused by the Alabama Claims

The ''Alabama'' Claims were a series of demands for damages sought by the federal government of the United States, government of the United States from the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom in 1869, for the attacks upon ...

. He refused the annexation request of Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa; sm, Sāmoa, and until 1997 known as Western Samoa, is a Polynesian island country consisting of two main islands ( Savai'i and Upolu); two smaller, inhabited islands ( Manono and Apolima); ...

, instead establishing a de facto tripartite protectorate with Great Britain and Germany.

Last year in office

Western tour, 1880

In 1880, Hayes embarked on a 71-day tour of the American West, becoming the first sitting President to travel west of the Rocky Mountains. Hayes' traveling party included his wife and GeneralWilliam Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman ( ; February 8, 1820February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), achieving recognition for his com ...

, who helped organize the trip. Hayes began his trip in September 1880, departing from Chicago on the transcontinental railroad

A transcontinental railroad or transcontinental railway is contiguous railroad trackage, that crosses a continental land mass and has terminals at different oceans or continental borders. Such networks can be via the tracks of either a single ...

. He journeyed across the continent, ultimately arriving in California, stopping first in Wyoming and then Utah and Nevada, reaching Sacramento and San Francisco. By railroad and stagecoach, the party traveled north to Oregon, arriving in Portland, and from there to Vancouver, Washington. Going by steamship, they visited Seattle, and then returned to San Francisco. Hayes then toured several southwestern states before returning to Ohio in November, in time to cast a vote in the 1880 presidential election.

1880 presidential election

James A. Garfield

James Abram Garfield (November 19, 1831 – September 19, 1881) was the 20th president of the United States, serving from March 4, 1881 until his death six months latertwo months after he was shot by an assassin. A lawyer and Civil War gene ...

, head of the Ohio delegation and chairman of the Convention Rules Committee, backed Treasury Secretary John Sherman. Elihu B. Washburne