Presidency of James Buchanan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The presidency of James Buchanan began on March 4, 1857, when

After

After  By 1856, the Whig Party, which had long been the main opposition to the Democrats, had collapsed. Buchanan faced not just one but two candidates in the general election: former Whig President

By 1856, the Whig Party, which had long been the main opposition to the Democrats, had collapsed. Buchanan faced not just one but two candidates in the general election: former Whig President

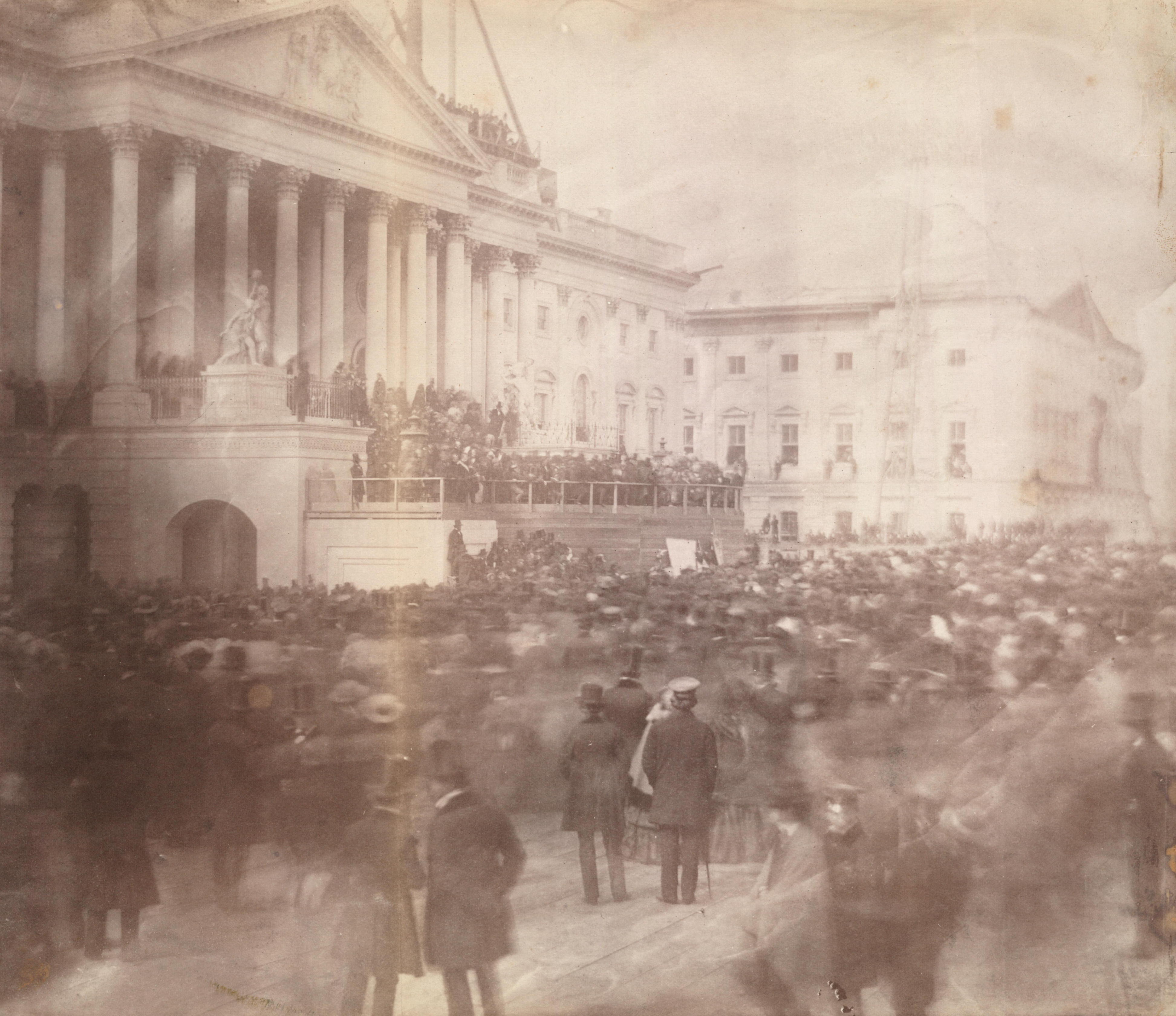

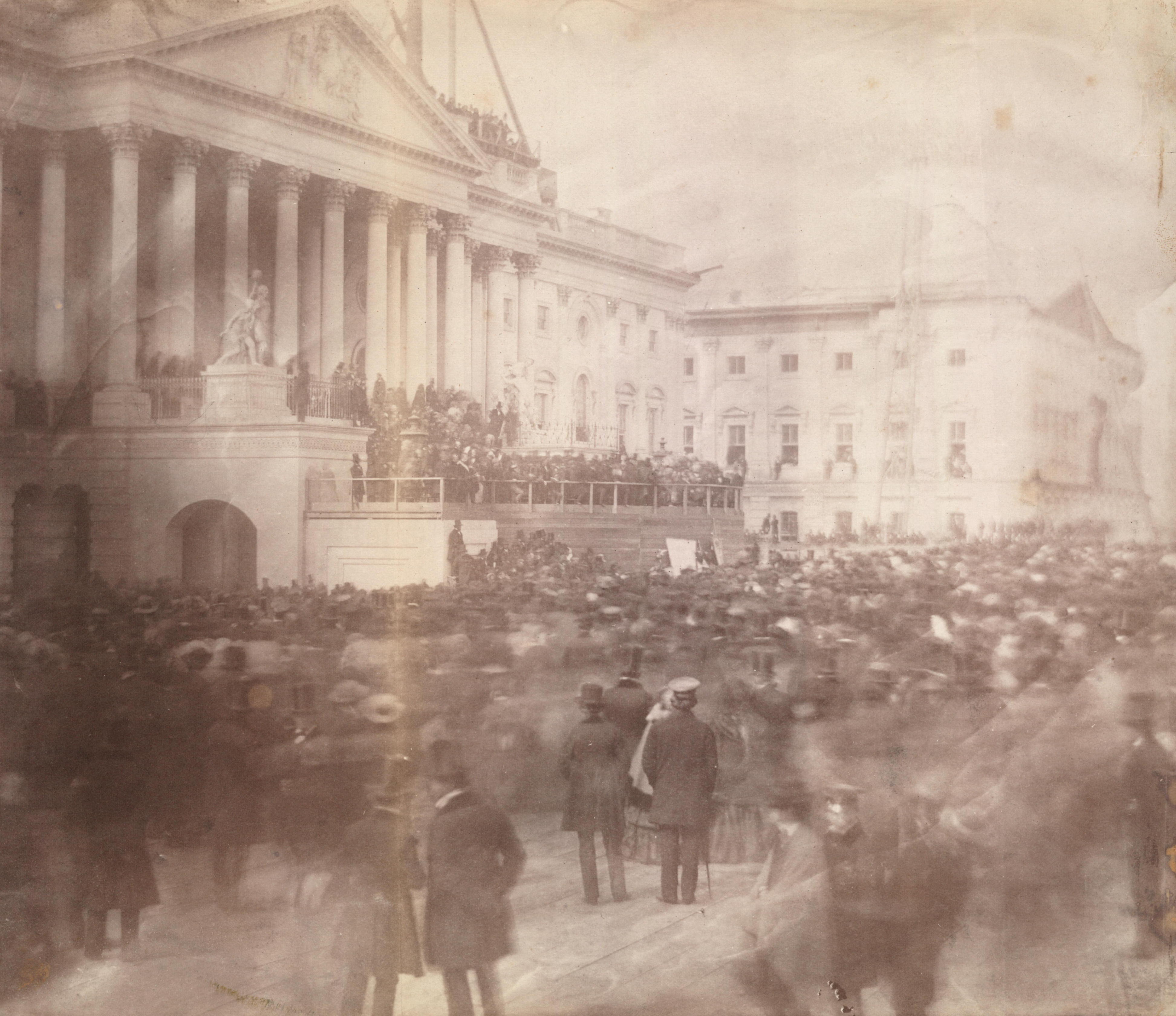

Buchanan was inaugurated as the nation's 15th president on March 4, 1857, on the East Portico of the

Buchanan was inaugurated as the nation's 15th president on March 4, 1857, on the East Portico of the

As his inauguration approached, Buchanan sought to establish a harmonious cabinet that would not fall victim to the in-fighting that had plagued

As his inauguration approached, Buchanan sought to establish a harmonious cabinet that would not fall victim to the in-fighting that had plagued

In the aftermath of the

In the aftermath of the

The

The  The 1860 election was essentially two races; in the North, Lincoln competed with Douglas for votes, while in the South, Breckinridge and Bell garnered the most support. Like his successful Whig predecessors, Lincoln largely refrained from campaigning after the convention, instead leaving that to others in the party. In his silence, Lincoln failed to refute the charge of Southern radicals that he hoped to abolish slavery. During the summer and fall of 1860, Southern governors corresponded about potentially seceding from the union, and Buchanan did little to denounce secessionists. Douglas, on the other hand, focused much of his campaign on attacking secessionists, who he worried would attempt to seize control of the federal government in the aftermath of a Lincoln victory. As Breckinridge and Bell lacked support in the North, the defeat of Lincoln required the victory of Douglas in at least some Northern states, but Buchanan remained focused on defeating Douglas. Some anti-Republican leaders attempted to form a fusion ticket in the North, but they achieved little success outside of New Jersey.

With the Democrats divided, Lincoln won the 1860 election with a plurality of the popular vote and a majority of the electoral vote. Lincoln won virtually no support in the South, but his strong performance over Douglas in the North gave him a majority of the electoral vote. Breckinridge won most of the South, Bell won Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee, and Douglas won Missouri and three electoral votes in New Jersey. Despite Lincoln's presidential victory, Republicans failed to win a majority in the House or Senate, and the Supreme Court membership remained largely the same as it had been when it issued the ''Dred Scott'' decision. Thus, despite the election of a Republican president, slavery in the South faced no immediate danger.

As early as October, the army's

The 1860 election was essentially two races; in the North, Lincoln competed with Douglas for votes, while in the South, Breckinridge and Bell garnered the most support. Like his successful Whig predecessors, Lincoln largely refrained from campaigning after the convention, instead leaving that to others in the party. In his silence, Lincoln failed to refute the charge of Southern radicals that he hoped to abolish slavery. During the summer and fall of 1860, Southern governors corresponded about potentially seceding from the union, and Buchanan did little to denounce secessionists. Douglas, on the other hand, focused much of his campaign on attacking secessionists, who he worried would attempt to seize control of the federal government in the aftermath of a Lincoln victory. As Breckinridge and Bell lacked support in the North, the defeat of Lincoln required the victory of Douglas in at least some Northern states, but Buchanan remained focused on defeating Douglas. Some anti-Republican leaders attempted to form a fusion ticket in the North, but they achieved little success outside of New Jersey.

With the Democrats divided, Lincoln won the 1860 election with a plurality of the popular vote and a majority of the electoral vote. Lincoln won virtually no support in the South, but his strong performance over Douglas in the North gave him a majority of the electoral vote. Breckinridge won most of the South, Bell won Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee, and Douglas won Missouri and three electoral votes in New Jersey. Despite Lincoln's presidential victory, Republicans failed to win a majority in the House or Senate, and the Supreme Court membership remained largely the same as it had been when it issued the ''Dred Scott'' decision. Thus, despite the election of a Republican president, slavery in the South faced no immediate danger.

As early as October, the army's

In 1850, Southern extremists had called the

In 1850, Southern extremists had called the

Fourth Annual Message to Congress.

' (1860, December 3). * Buchanan, James. ''The messages of President Buchanan. With an appendix containing sundry letters from members of his cabinet at the close of his presidential term, etc'' (1888

online

* Buchanan, James.

' (1866); his self defense was not very convincing. see Allen F. Cole, "Asserting His Authority: James Buchanan's Failed Vindication." ''Pennsylvania History'' 70.1 (2003): 81-9

online

online

* Auchampaugh, Phillip G. "James Buchanan and Some Far Western Leaders, 1860-1861." ''Pacific Historical Review'' 12.2 (1943): 169-180

online

* Auchampaugh, Philip G. “James Buchanan, The Conservatives’ Choice, 1856: A Political Portrait.” ''Historian'' 7#2 (1945), pp. 77–90

online

* Balcerski, Thomas J. "Harriet Rebecca Lane Johnston." in ''A Companion to First Ladies'' (2016): 197-213. * Balcerski, Thomas J. ''Bosom Friends: The Intimate World of James Buchanan and William Rufus King'' (Oxford University Press, 2019

online review

* Bigler, David L. and Will Bagley. ''The Mormon Rebellion: America’s First Civil War, 1857-1858'' (2011) * Binder, Frederick Moore. "James Buchanan: Jacksonian Expansionist" ''Historian'' 1992 55(1): 69–84. ISSN 0018-2370 Full text: in Ebsco * Binder, Frederick Moore. ''James Buchanan and the American Empire.'' Susquehanna U. Press, 1994

online

* Binder, Frederick Moore. "James Buchanan and the earl of Clarendon: An uncertain relationship." ''Diplomacy and Statecraft'' 6.2 (1995): 323-341. The Earl was British foreign minister; both men wanted control of the Caribbean * Birkner, Michael J., ed. ''James Buchanan and the Political Crisis of the 1850s.'' (Susquehanna U. Press, 1996(. * Birkner, Michael J., et al. eds. ''The Worlds of James Buchanan and Thaddeus Stevens: Place, Personality, and Politics in the Civil War Era'' (Louisiana State University Press, 2019) * Bonar, Hugh Samuel. "Attitude of Buchanan as President Toward Secession" (PhD dissertation, The University of Chicago ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1924. TM14183. * Boulard, Garry. ''The Worst President—The Story of James Buchanan'' iUniverse, 2015. . *

* Davis, Robert Ralph. "James Buchanan and the Suppression of the Slave Trade, 1858-1861" ''Pennsylvania History'' 33#4 (1966), pp. 446–59

online

* Etcheson, Nicole. ''Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty in the Civil War Era'' (University Presses of Kansas, 2004). * Freehling, William W. ''The Road to Disunion: Volume II; Secessionists Triumphant'' (Oxford UP, 2008). * Furniss, Norman E. ''The Mormon Conflict 1850-1859'' (Yale University Press, 1960

online

* Genovese, Michael A., and Alysa Landry. "The Jacksonian Hammer: Andrew Jackson to James Buchanan." in ''US Presidents and the Destruction of the Native American Nations'' (Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2021) pp. 67-103. * Gienapp, William E. “No Bed of Roses: James Buchanan, Abraham Lincoln, and Presidential Leadership in the Civil War Era,” in Michael J. Birkner, ed. ''James Buchanan and the Political Crisis of the 1850s'' (1996). * Graff, Henry F., ed. ''The Presidents: A Reference History'' (3rd ed. 2002)

online

* Greenstein, Fred I. ''Presidents and the Dissolution of the Union: Leadership Style from Polk to Lincoln'' (Princeton UP, 2013). * Harmon, George D. “President James Buchanan’s Betrayal of Governor Robert J. Walker of Kansas.” ''Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography'' 53#1 (1929), pp. 51–91

online

* Harmon, George D. "An Indictment of the Administration of President James Buchanan and His Kansas Policy." ''The Historian'' 3.1 (1940): 52-68

online

* Hunt, Gaillard. "Narrative and Letter of William Henry Trescot, Concerning the Negotiations between South Carolina and President Buchanan in December, 1860." ''American Historical Review'' 13.3 (1908): 528-556

online

* King, Horatio C. ''Turning on the Light: A Dispassionate Survey of President Buchanan’s Administration from 1860 to Its Close'' (J. B. Lippincott, 1895), pro-Buchanan study by his Postmaster General. * Klein, Philip Shriver. "James Buchanan's Policy of Expansion" (Phd Dissertation, The University of Chicago; Proquest Dissertations Publishing, 1932. Tm164710. * Landis, Michael Todd. "Old Buck's Lieutenant: Glancy Jones, James Buchanan, and the Antebellum Northern Democracy." ''Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography'' 140.2 (2016): 183-210

online

* Landis, Michael Todd. ''Northern Men with Southern Loyalties: The Democratic Party and the Sectional Crisis'' (Cornell UP, 2014). * Leonard, Elizabeth D. ''Lincoln’s Forgotten Ally: Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt of Kentucky'' (U of North Carolina Press, 2011). * Levinson, Sanford. “James Buchanan and John J. Crittenden.” in ''The U.S. Constitution and Secession: A Documentary Anthology of Slavery and White Supremacy,'' edited by Dwight T. Pitcaithley, (University Press of Kansas, 2018), pp. 61–92

online

* Lynn, Joshua A. “Doughface Triumphant: James Buchanan’s Manly Conservatism and the Election of 1856.” in ''Preserving the White Man’s Republic: Jacksonian Democracy, Race, and the Transformation of American Conservatism'' (University of Virginia Press, 2019), pp. 119–45

online

* Lynn, Joshua A. "A Manly Doughface: James Buchanan and the Sectional Politics of Gender." ''Journal of the Civil War Era'' 8.4 (2018): 591-62

online

* Mackinnon, William P. "Hammering Utah, Squeezing Mexico, and Coveting Cuba: James Buchanan's White House Intriques" ''Utah Historical Quarterly'', 80#2 (2012), pp. 132-15 https://doi.org/10.2307/45063308 * Mackinnon, William P. "And the War Came: James Buchanan, the Utah Expedition, and the Decision to Intervene," ''Utah Historical Quarterly'' 76 (Winter 2008): 22-37. * Meerse, David. "Buchanan, the Patronage, and the Lecompton Constitution: A Case Study" ''Civil War History'' (1995) 41(4): 291–312. ISSN 0009-8078 * Meerse, David E. "Origins of the Buchanan-Douglas Feud Reconsidered." ''Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society '' 67#2 (1974): 154–174 online

online

* Meerse, David E. "Buchanan, Corruption and the Election of 1860."

online

* Meerse, David Edward. "James Buchanan, the Patronage, and the Northern Democratic Party, 1857-1858" (PhD dissertation, University Of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; Proquest Dissertations Publishing, 1969. 7013419). * Nevins, Allan. ''The Emergence of Lincoln'' 2 vols. (1960) highly detailed narrative of his presidency

vol 1 online

also se

vol 2 online

* Nichols, Roy Franklin. ''The Disruption of American Democracy'' (1948), the Democratic Party in 1850s

online

* Pendleton, Lawson Alan. "James Buchanan's Attitude Toward Slavery" (PhD Dissertation, The University Of North Carolina At Chapel Hill; Proquest Dissertations Publishing, 1964. 6509047). * Pinnegar, Charles. ''Brand of Infamy: A Biography of John Buchanan Floyd'' (Greenwood Press, 2002). * * Rosenberger, Homer T. "Inauguration of President Buchanan a Century Ago." ''Records of the Columbia Historical Society'' 57 (1957): 96-12

online

* * Sears, Louis Martin. "Slidell and Buchanan." ''American Historical Review'' 27.4 (1922): 709-730

online

* * Stenberg, Richard R. "An Unnoted Factor in the Buchanan-Douglas Feud." ''Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society'' (1933): 271-284

online

* Weatherman, Donald V. “James Buchanan on Slavery and Secession.” ''Presidential Studies Quarterly'' 15#4 (1985), pp. 796–805

online

* Wells, Damon. "Douglas and Goliath." in ''Stephen Douglas'' (University of Texas Press, 1971) pp. 12-54. on Douglas and Buchanan

online

* Williams, David A. "President Buchanan Receives a Proposal for an Anti-Mormon Crusade, 1857." ''Brigham Young University Studies'' 14.1 (1973): 103-105

online

Essay on James Buchanan and shorter essays on each member of his cabinet and First Lady

from the

James Buchanan: A Resource Guide

from the Library of Congress * Th

spanning the entirety of his legal, political and diplomatic career, are available for research use at the

University of Virginia article: Buchanan biography

"Life Portrait of James Buchanan"

from

''Mr. Buchanans Administration on the Eve of the Rebellion''. President Buchanans memoirs.

Fourth Annual Message to Congress, December 3, 1860

{{Authority control 1850s in the United States 1860s in the United States Buchanan, James 1857 establishments in the United States 1861 disestablishments in the United States

James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was an American lawyer, diplomat and politician who served as the 15th president of the United States from 1857 to 1861. He previously served as secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and repr ...

was inaugurated

In government and politics, inauguration is the process of swearing a person into office and thus making that person the incumbent. Such an inauguration commonly occurs through a formal ceremony or special event, which may also include an inaugur ...

as 15th president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal gove ...

, and ended on March 4, 1861. Buchanan, a Democrat from Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, took office as the 15th United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

president after defeating former President Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800March 8, 1874) was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853; he was the last to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House. A former member of the U.S. House of Represen ...

of the American Party, and John C. Frémont

John Charles Frémont or Fremont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was an American explorer, military officer, and politician. He was a U.S. Senator from California and was the first Republican nominee for president of the United States in 1856 ...

of the Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

* Republican Party (Liberia)

*Republican Party ...

in the 1856 presidential election.

Buchanan was nominated by the Democratic Party at its 1856 convention, where he defeated both the incumbent President Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. He was a northern Democrat who believed that the abolitionist movement was a fundamental threat to the nation's unity ...

and Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas. Despite his long experience in government, Buchanan was unable to calm the growing sectional crisis that would divide the nation at the close of his term. Prior to taking office, Buchanan lobbied the Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

to issue a broad ruling in ''Dred Scott v. Sandford

''Dred Scott v. Sandford'', 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1857), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that held the U.S. Constitution did not extend American citizenship to people of black African descent, enslaved or free; th ...

''. Though Buchanan hoped that the Court's ruling would end the dispute over slavery in the territories, Buchanan's support of the ruling deeply alienated many Northerners. Buchanan also joined with Southern leaders in attempting to gain the admission of Kansas

Kansas () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its Capital city, capital is Topeka, Kansas, Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita, Kansas, Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebras ...

to the Union as a slave state

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were not. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave states ...

under the Lecompton Constitution. In the midst of the growing chasm between slave states and free states

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were not. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave states ...

, the Panic of 1857

The Panic of 1857 was a financial panic in the United States caused by the declining international economy and over-expansion of the domestic economy. Because of the invention of the telegraph by Samuel F. Morse in 1844, the Panic of 1857 was ...

struck the nation, causing widespread business failures and high unemployment.

Tensions over slavery continued to the end of Buchanan's term. Buchanan had promised in his inaugural address to serve just one term, and with the ongoing national turmoil over slavery and the nature of the Union, there was a deep yearning for fresh leadership within the Democratic Party. Republican nominee Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

, running on a platform devoted to keeping slavery out of all Western territories, defeated the splintered Democratic Party and Constitutional Union candidate John Bell to win the 1860 election. In response to Lincoln's victory, seven Southern states declared their secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics l ...

from the Union. Buchanan refused to confront the seceded states with military force, but retained control of Fort Sumter

Fort Sumter is a sea fort built on an artificial island protecting Charleston, South Carolina from naval invasion. Its origin dates to the War of 1812 when the British invaded Washington by sea. It was still incomplete in 1861 when the Battle ...

. However in its last two months the Buchanan Administration took a much stiffer anti-Confederate position, as Southerners resigned. The president announced that he would do all within his power to defend Fort Sumter, thereby rallying Northern support. Key anti-Confederate leaders included the new Attorney General Edwin Stanton

Edwin McMasters Stanton (December 19, 1814December 24, 1869) was an American lawyer and politician who served as U.S. Secretary of War under the Lincoln Administration during most of the American Civil War. Stanton's management helped organize ...

and the new Secretary of War Joseph Holt. The secession crisis culminated in the outbreak of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

shortly after Buchanan left office. Historians condemn him for not forestalling the secession of southern states or addressing the issue of slavery. He is consistently ranked as one of the worst presidents in American history, often being ranked as the worst president.

Election of 1856

After

After Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. He was a northern Democrat who believed that the abolitionist movement was a fundamental threat to the nation's unity ...

won the 1852 presidential election, Buchanan agreed to serve as the United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom

The United States ambassador to the United Kingdom (known formally as the ambassador of the United States to the Court of St James's) is the official representative of the president of the United States and the American government to the monarc ...

. Buchanan's service abroad conveniently placed him outside of the country while a debate over the Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law ...

roiled the nation. While Buchanan did not overtly seek the 1856 Democratic presidential nomination, he most deliberately chose not to discourage the movement on his behalf, something that was well within his power on many occasions. The 1856 Democratic National Convention

The 1856 Democratic National Convention was a presidential nominating convention that met from June 2 to June 6 in Cincinnati, Ohio. It was held to nominate the Democratic Party's candidates for president and vice president in the 1856 election ...

met in June 1856, writing a platform that largely reflected Buchanan's views, including support for the Fugitive Slave Law

The fugitive slave laws were laws passed by the United States Congress in 1793 and 1850 to provide for the return of enslaved people who escaped from one state into another state or territory. The idea of the fugitive slave law was derived from ...

, an end to anti-slavery agitation, and U.S. "ascendancy in the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United ...

." Buchanan led on the first ballot, boosted by the support of powerful Senators John Slidell

John Slidell (1793July 9, 1871) was an American politician, lawyer, and businessman. A native of New York, Slidell moved to Louisiana as a young man and became a Representative and Senator. He was one of two Confederate diplomats captured by the ...

, Jesse Bright, and James A. Bayard, who presented Buchanan as an experienced leader who could appeal to the North and South. President Pierce and Senator Stephen A. Douglas also sought the nomination, but Buchanan was selected as the Democratic presidential nominee on the seventeenth ballot of the convention. He was joined on the Democratic ticket by John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky.

By 1856, the Whig Party, which had long been the main opposition to the Democrats, had collapsed. Buchanan faced not just one but two candidates in the general election: former Whig President

By 1856, the Whig Party, which had long been the main opposition to the Democrats, had collapsed. Buchanan faced not just one but two candidates in the general election: former Whig President Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800March 8, 1874) was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853; he was the last to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House. A former member of the U.S. House of Represen ...

ran as the American Party (or "Know-Nothing

The Know Nothing party was a nativist political party and movement in the United States in the mid-1850s. The party was officially known as the "Native American Party" prior to 1855 and thereafter, it was simply known as the "American Party". ...

") candidate, while John C. Frémont

John Charles Frémont or Fremont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was an American explorer, military officer, and politician. He was a U.S. Senator from California and was the first Republican nominee for president of the United States in 1856 ...

ran as the Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

nominee. Much of the private rhetoric of the campaign focused on unfounded rumors regarding Frémont—talk of him as president taking charge of a large army that would support slave insurrections, the likelihood of widespread lynchings of slaves, and whispered hope among slaves for freedom and political equality.

Sticking with the convention of the times, Buchanan did not himself campaign, but he wrote letters and pledged to uphold the Democratic platform. In the election, Buchanan carried every slave state except for Maryland, as well as five free states, including his home state of Pennsylvania. He won 45 percent of the popular vote and 174 electoral votes, compared to Frémont's 114 electoral votes and Fillmore's 8 electoral votes. Buchanan's election made him the first and until 2021 only president from Pennsylvania. In his victory speech, Buchanan denounced Republicans, calling the Republican Party a "dangerous" and "geographical" party that had unfairly attacked the South. President-elect Buchanan would also state, "the object of my administration will be to destroy sectional party, North or South, and to restore harmony to the Union under a national and conservative government."

Inauguration

Buchanan was inaugurated as the nation's 15th president on March 4, 1857, on the East Portico of the

Buchanan was inaugurated as the nation's 15th president on March 4, 1857, on the East Portico of the United States Capitol

The United States Capitol, often called The Capitol or the Capitol Building, is the seat of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, which is formally known as the United States Congress. It is located on Capitol Hill ...

. Chief Justice Roger Taney

Roger Brooke Taney (; March 17, 1777 – October 12, 1864) was the fifth chief justice of the United States, holding that office from 1836 until his death in 1864. Although an opponent of slavery, believing it to be an evil practice, Taney belie ...

administered the Oath of office

An oath of office is an oath or affirmation a person takes before assuming the duties of an office, usually a position in government or within a religious body, although such oaths are sometimes required of officers of other organizations. Suc ...

. This is the first inauguration ceremony known to have been photographed. In his inaugural address, Buchanan committed himself to serving only one term. He also spoke critically about the growing divisions over slavery and its status in the territories, stating,

Furthermore, Buchanan argued that a federal slave code

The slave codes were laws relating to slavery and enslaved people, specifically regarding the Atlantic slave trade and chattel slavery in the Americas.

Most slave codes were concerned with the rights and duties of free people in regards to ensla ...

should protect the rights of slave owners in any federal territory. He alluded to a pending Supreme Court case, ''Dred Scott v. Sandford

''Dred Scott v. Sandford'', 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1857), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that held the U.S. Constitution did not extend American citizenship to people of black African descent, enslaved or free; th ...

'', which he stated would permanently settle the issue of slavery.

Buchanan already knew the outcome of the case and had even played a part in its disposition. Associate Justice Robert C. Grier

Robert Cooper Grier (March 5, 1794 – September 25, 1870) was an American jurist who served on the Supreme Court of the United States.

A Jacksonian Democrat from Pennsylvania who served from 1846 to 1870, Grier weighed in on some of the most i ...

leaked the decision of the "Dred Scott" case early to Buchanan. In his inaugural address Buchanan declared that the issue of slavery in the territories would be "speedily and finally settled" by the Supreme Court. According to historian Paul Finkelman:Buchanan already knew what the Court was going to decide. In a major breach of Court etiquette, Justice Grier, who, like Buchanan, was from Pennsylvania, had kept the President-elect fully informed about the progress of the case and the internal debates within the Court. When Buchanan urged the nation to support the decision, he already knew what Taney would say. Republican suspicions of impropriety turned out to be fully justified.Historians agree that the address was a major disaster for Buchanan as the ''Dred Scott'' decision dramatically inflamed tensions leading to the Civil Wwar. In 2022 historian David W. Blight argues that the year 1857 was, "the great pivot on the road to disunion...largely because of the Dred Scott case, which stoked the fear, distrust and conspiratorial hatred already common in both the North and the South to new levels of intensity."

Administration

As his inauguration approached, Buchanan sought to establish a harmonious cabinet that would not fall victim to the in-fighting that had plagued

As his inauguration approached, Buchanan sought to establish a harmonious cabinet that would not fall victim to the in-fighting that had plagued Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

's top officials. One of his closest advisers—who was named ambassador to Britain—was Jehu Glancy Jones.

Buchanan sought to be the clear leader of the cabinet, and chose men who would agree with his views. Anticipating that his administration would concentrate on foreign policy and that Buchanan himself would largely direct foreign policy, he appointed the aging Lewis Cass

Lewis Cass (October 9, 1782June 17, 1866) was an American military officer, politician, and statesman. He represented Michigan in the United States Senate and served in the Cabinets of two U.S. Presidents, Andrew Jackson and James Buchanan. He w ...

as Secretary of State. Cass would become marginalized in Buchanan's administration, with Buchanan and Assistant Secretary of State Assistant Secretary of State (A/S) is a title used for many executive positions in the United States Department of State, ranking below the under secretaries. A set of six assistant secretaries reporting to the under secretary for political affairs ...

John Appleton

John Appleton (February 11, 1815 – August 22, 1864) was an American lawyer, politician and diplomat who served as the United States' first ''chargé d'affaires'' to Bolivia, and later as special envoy to Great Britain and Russia. Born i ...

instead directing foreign affairs. In filling out his cabinet, Buchanan chose four Southerners and three Northerners, one of whom was Secretary of the Navy Isaac Toucey

Isaac Toucey (November 15, 1792July 30, 1869) was an American politician who served as a U.S. senator, U.S. Secretary of the Navy, U.S. Attorney General and the 33rd Governor of Connecticut.

Biography

Born in Newtown, Connecticut, Toucey p ...

, widely considered to be a "doughface," or Southern-sympathizer. Aside from the nearly-senile Cass, only Attorney General Jeremiah S. Black

Jeremiah Sullivan Black (January 10, 1810 – August 19, 1883) was an American statesman and lawyer. He served as a justice on the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania (1851–1857) and as the Court's Chief Justice (1851–1854). He also served in the ...

lacked partiality towards the South, but Black despised abolitionists and free-soilers.

Battling Stephen Douglas of Illinois

Buchanan's appointment of Southerners and Southern sympathizers alienated many in the North, and his failure to appoint any followers of Stephen Douglas divided the party. Though Buchanan owed his nomination to Douglas's decision to withdraw from consideration at the 1856 Democratic convention, he disliked Douglas personally and favored Jesse D. Bright, who hoped to unseat Douglas as the leader of the Midwestern Democrats. Outside of the cabinet, Buchanan left in place many of Pierce's appointments, but removed a disproportionate number of Northerners who had ties to Pierce or Douglas. Buchanan quickly alienated his vice president, Breckinridge, and the latter played little role in the Buchanan administration. Buchanan and his allies in Congress worked systematically to undermine Douglas. By 1860 they had weakened his influence in the Party; they had stripped away his patronage, and removed him from the powerful chairmanship of the Committee on Territories. He was much weaker inside the Senate than before. Nevertheless, Douglas had a powerful base outside Washington in the northern wing of the Democratic Party that was increasingly hostile to the president and his southern supporters. The battle with Lincoln in 1858 drew national attention, with Democrats reading Douglas's debates and hailing him as the victor, thereby allowing Douglas to emerge as the favorite to win the party nomination for president in 1860.Judicial appointments

Buchanan appointed one Justice to theSupreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. Federal tribunals in the United States, federal court cases, and over Stat ...

, Nathan Clifford of Maine. Clifford had served with Buchanan in James K. Polk's cabinet, and his views on major issues largely aligned with those of Buchanan. Clifford succeeded Benjamin Robbins Curtis

Benjamin Robbins Curtis (November 4, 1809 – September 15, 1874) was an American lawyer and judge. He served as an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court from 1851 to 1857. Curtis was the first and only Whig justice of the ...

, who had resigned in protest of the ''Dred Scott'' decision. Clifford's nomination was opposed by many Northern senators, but he won confirmation in a 26-to-23 vote. A second vacancy arose after the death of Peter Vivian Daniel in 1860, and Buchanan nominated Attorney General Black to fill the opening. In the aftermath of the election of 1860, Black fell just one vote short of confirmation, leaving one Supreme Court seat open as Buchanan left office. Aside from Clifford, Buchanan appointed only seven other Article III federal judges, all to United States district court

The United States district courts are the trial courts of the U.S. federal judiciary. There is one district court for each federal judicial district, which each cover one U.S. state or, in some cases, a portion of a state. Each district co ...

s.

Dred Scott case

In the aftermath of the

In the aftermath of the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the ...

, a new debate had arisen over the status of slavery in the western territories. While abolitionism

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

had not emerged as a strong force, many Northerners saw slavery as a moral blight and opposed the extension of slavery into the territories

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, particularly belonging or connected to a country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually either the total area from which a state may extract power resources or a ...

. Many Southerners, meanwhile, were deeply offended by the moral assault on the institution of slavery and feared that an attack on slavery in the territories could lead to an attack on slavery in the South. The Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that defused a political confrontation between slave and free states on the status of territories acquired in the Mexican–Am ...

had temporarily defused the situation, but every Northern defiance of the Fugitive Slave Act

A fugitive (or runaway) is a person who is fleeing from custody, whether it be from jail, a government arrest, government or non-government questioning, vigilante violence, or outraged private individuals. A fugitive from justice, also know ...

(passed as part of the compromise) inflamed tensions in the South. The 1852 publication of ''Uncle Tom's Cabin

''Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly'' is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in two volumes in 1852, the novel had a profound effect on attitudes toward African Americans and slavery in the U ...

'' further divided opinion. In 1854, the Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law ...

repealed the Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise was a federal legislation of the United States that balanced desires of northern states to prevent expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand it. It admitted Missouri as a Slave states an ...

, which had excluded slavery from territories north of the 36°30′ parallel. Each new state would instead decide upon the status of slavery under the concept of popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty is the principle that the authority of a state and its government are created and sustained by the consent of its people, who are the source of all political power. Popular sovereignty, being a principle, does not imply any ...

. The bill was very unpopular in the North, and its passage contributed to the collapse of the Whig Party and the rise of the Republican Party, which consisted almost entirely of Northerners opposed to the expansion of slavery into the territories. Though few Republicans sought to abolish slavery in the South, Southerners saw the very existence of the Republican Party as an affront, and the Republicans made little effort to appeal to the South with any of their other policies, such as support for high tariffs

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and po ...

and federally-funded internal improvements.

Upon taking office, Buchanan hoped to not only end the tensions over slavery but also vanquish what he saw as a dangerously-sectional Republican Party. The most pressing issue regarding slavery was its status in the territories, and whether popular sovereignty meant that territorial legislatures could bar the entrance of slaves. Seeing an opening in a pending Supreme Court case to settle the issue, President-Elect Buchanan had involved himself in the decision-making process of the Court in the months leading up to his own inauguration.

Two days after Buchanan's inauguration, Chief Justice Taney delivered the ''Dred Scott'' decision, which asserted that Congress had no constitutional power to exclude slavery in the territories. Prior to his inauguration, Buchanan had written to Justice John Catron

John Catron (January 7, 1786 – May 30, 1865) was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1837 to 1865, during the Taney Court.

Early and family life

Little is known of Catron's ...

in January 1857, inquiring about the outcome of the case and suggesting that a broader decision would be more prudent. Catron, who was from Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 36th-largest by ...

, replied on February 10 that the Supreme Court's Southern majority would decide against Scott, but would likely have to publish the decision on narrow grounds if there was no support from the Court's northern justices—unless Buchanan could convince his fellow Pennsylvanian, Justice Robert Cooper Grier

Robert Cooper Grier (March 5, 1794 – September 25, 1870) was an American jurist who served on the Supreme Court of the United States.

A Jacksonian Democrat from Pennsylvania who served from 1846 to 1870, Grier weighed in on some of the most ...

, to join the majority. Buchanan hoped that a broad Supreme Court decision protecting slavery in the territories could lay the issue to rest once and for all, allowing the country to focus on other issues, including the possible annexation of Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

and the acquisition of more Mexican territory. So Buchanan wrote to Grier and successfully prevailed upon him, allowing the majority leverage to issue a broad-ranging decision that transcended the specific circumstances of Scott's case to declare the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional. When the Court's decision in ''Dred Scott'' was issued two days after Buchanan's inauguration, Republicans began spreading word that Taney had revealed to Buchanan the forthcoming result. Buchanan's strong public support of the decision earned him and his party the enmity of many Northerners from the outset of his presidency.

Panic of 1857 and economic policy

ThePanic of 1857

The Panic of 1857 was a financial panic in the United States caused by the declining international economy and over-expansion of the domestic economy. Because of the invention of the telegraph by Samuel F. Morse in 1844, the Panic of 1857 was ...

began in the middle of that year, ushered in by the sequential collapse of fourteen hundred state banks and five thousand businesses. While the South escaped largely unscathed, Northern cities saw numerous unemployed men and women take to the streets to beg. Reflecting his Jacksonian background, Buchanan's response was "reform not relief". While the government was "without the power to extend relief", it would continue to pay its debts in specie, and while it would not curtail public works, none would be added. Buchanan urged the states to restrict the banks to a credit level of $3 to $1 of specie, and discouraged the use of federal or state bonds as security for bank note issues. Though the economy recovered by 1859, the panic inflamed sectional tensions, as many Northerners blamed the Southern-backed Tariff of 1857

The Tariff of 1857 was a major tax reduction in the United States that amended the Walker Tariff of 1846 by lowering rates to between 15% and 24%.

The Tariff of 1857 was developed in response to a federal budget surplus in the mid-1850s. The firs ...

(passed during Pierce's last day in office) for the panic. Southerners, as well as Buchanan, instead blamed the over-speculation of Northern bankers. In part due to the worsened economy, by the time Buchanan left office the federal deficit stood at $17 million, higher than it had been when Buchanan took office.

Throughout 1858 and 1859, Congress continued to debate perennial issues such as the tariff and infrastructure spending. Southern and Western congressmen succeeded in retaining the low rates of the Tariff of 1857 until 1861. Many in Congress pushed for the construction of a transcontinental railroad

A transcontinental railroad or transcontinental railway is contiguous railroad trackage, that crosses a continental land mass and has terminals at different oceans or continental borders. Such networks can be via the tracks of either a single ...

, but its construction was prevented by a combination of Southern and New England congressmen. Among the pieces of legislation that Buchanan vetoed were the Homestead Act

The Homestead Acts were several laws in the United States by which an applicant could acquire ownership of government land or the public domain, typically called a homestead. In all, more than of public land, or nearly 10 percent of t ...

, which would have given 160 acres of public land to settlers who remained on settled land for five years, and the Morrill Act

The Morrill Land-Grant Acts are United States statutes that allowed for the creation of land-grant colleges in U.S. states using the proceeds from sales of federally-owned land, often obtained from indigenous tribes through treaty, cession, or s ...

, which would have granted public lands to establish land-grant colleges

A land-grant university (also called land-grant college or land-grant institution) is an institution of higher education in the United States designated by a state to receive the benefits of the Morrill Acts of 1862 and 1890.

Signed by Abraha ...

. Buchanan argued that these acts were beyond the power of the federal government as established by the Constitution. Following the secession of several Southern states, Congress passed the Morrill Tariff, significantly raising rates. Despite his long opposition to higher tariffs, Buchanan signed the tariff into law on March 2, 1861. The Morrill Tariff raised the tariff to the highest levels seen since the 1840s, and passage of the law marked a new period of protectionist tariffs that would continue long after Buchanan left office.

Utah War

Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to its ...

had been settled by Mormons

Mormons are a religious and cultural group related to Mormonism, the principal branch of the Latter Day Saint movement started by Joseph Smith in upstate New York during the 1820s. After Smith's death in 1844, the movement split into sever ...

in the decades preceding Buchanan's presidency, and under the leadership of Brigham Young

Brigham Young (; June 1, 1801August 29, 1877) was an American religious leader and politician. He was the second president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), from 1847 until his death in 1877. During his time as chu ...

the Mormons had grown increasingly hostile to federal intervention. Young harassed federal officers and discouraged outsiders from settling in the Salt Lake City

Salt Lake City (often shortened to Salt Lake and abbreviated as SLC) is the capital and most populous city of Utah, United States. It is the seat of Salt Lake County, the most populous county in Utah. With a population of 200,133 in 2020, th ...

area, and in September 1857 the Utah Territorial Militia perpetrated the Mountain Meadows massacre

The Mountain Meadows Massacre (September 7–11, 1857) was a series of attacks during the Utah War that resulted in the mass murder of at least 120 members of the Baker–Fancher emigrant wagon train. The massacre occurred in the southern U ...

against Arkansans headed for California. Buchanan was also personally offended by the polygamous

Crimes

Polygamy (from Late Greek (') "state of marriage to many spouses") is the practice of marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, sociologists call this polygyny. When a woman is marri ...

behavior of Young.

Accepting the wildest rumors and believing the Mormons to be in open rebellion against the United States, Buchanan sent the army in November 1857 to replace Young as governor with the non-Mormon Alfred Cumming. While the Mormons had frequently defied federal authority, some question whether Buchanan's action was a justifiable or prudent response to uncorroborated reports. Complicating matters, Young's notice of his replacement was not delivered because the Pierce administration had annulled the Utah mail contract. After Young reacted to the military action by mustering a two-week expedition destroying wagon trains, oxen, and other Army property, Buchanan dispatched Thomas L. Kane

Thomas Leiper Kane (January 27, 1822 – December 26, 1883) was an American attorney, abolitionist, philanthropist, and military officer who was influential in the western migration of the Latter-day Saint movement and served as a Union Army colon ...

as a private agent to negotiate peace. The mission succeeded, the new governor was shortly placed in office, and the Utah War

The Utah War (1857–1858), also known as the Utah Expedition, Utah Campaign, Buchanan's Blunder, the Mormon War, or the Mormon Rebellion was an armed confrontation between Mormon settlers in the Utah Territory and the armed forces of the US go ...

ended. The president granted amnesty to all inhabitants who would respect the authority of the government, and moved the federal troops to a nonthreatening distance for the balance of his administration. Though he continued to practice polygamy, Young largely accepted federal authority after the conclusion of the Utah War.

Bleeding Kansas

After the passage of the Kansas–Nebraska Act in 1854, two competing governments had been formed inKansas Territory

The Territory of Kansas was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 30, 1854, until January 29, 1861, when the eastern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the free state of Kansas.

...

. The anti-slavery settlers organized a government in Topeka

Topeka ( ; Kansa: ; iow, Dópikˀe, script=Latn or ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Kansas and the seat of Shawnee County. It is along the Kansas River in the central part of Shawnee County, in northeast Kansas, in the Central Uni ...

, while pro-slavery settlers established a seat of government in Lecompton, Kansas. For Kansas to be admitted as a state, a constitution had to be submitted to Congress with the approval of a majority of residents. Under President Pierce, a series of violent confrontations known as "Bleeding Kansas

Bleeding Kansas, Bloody Kansas, or the Border War was a series of violent civil confrontations in Kansas Territory, and to a lesser extent in western Missouri, between 1854 and 1859. It emerged from a political and ideological debate over the ...

" occurred as supporters of the two governments clashed. The situation in Kansas was watched closely throughout the country, and some in Georgia and Mississippi advocated secession should Kansas be admitted as a free state. Buchanan himself did not particularly care whether or not Kansas entered as a slave state, and instead sought to admit Kansas as a state as soon as possible since it would likely tilt towards the Democratic Party. Rather than restarting the process and establishing one territorial government, Buchanan chose to recognize the pro-slavery Lecompton government. In his first Annual Message to Congress, in December 1857, he urged that Kansas be admitted as a slave state under the Lecompton Constitution.

Historians have taken one of two approaches to the Kansas policy. Allan Nevins

Joseph Allan Nevins (May 20, 1890 – March 5, 1971) was an American historian and journalist, known for his extensive work on the history of the Civil War and his biographies of such figures as Grover Cleveland, Hamilton Fish, Henry Ford, and J ...

presents a "melodramatic" interpretation. He argues that Buchanan honestly wanted a constitution ratified by genuine residents. His firmness weakened in the face of pro-Southern factions in his cabinet and party and he retreated. Roy Nichols

Roy Ernest Nichols (October 21, 1932 – July 3, 2001) was an American country music guitarist best known as the lead guitarist for Merle Haggard's band The Strangers for more than two decades. He was known for his guitar technique, a mix o ...

takes a "legalist" approach arguing that Buchanan only submitted one issue, slavery itself, to the voters. But he became distracted by the financial panic of 1857 and accepted the Lecompton Constitution. Nevins and Nichols agree on Buchanan's weak leadership, but offer subtle variations on how Buchanan tried to hold the middle ground by accepting a ''de facto'' slavery settlement.

Upon taking office, Buchanan appointed Robert J. Walker to replace John W. Geary as territorial governor of Kansas, with the mission of reconciling the settler factions and approving a constitution. Walker, who was from the slave state of Mississippi, was expected to assist the pro-slavery faction in gaining approval of a new constitution. Buchanan overcame Walker's initial reluctance to accept the appointment by persuading Walker that a successful resolution to the Kansas issue could catapult Walker to the presidency in 1860. Buchanan also promised Walker that Kansas would hold a free and fair referendum on any state constitution. Shortly after arriving in Kansas, Walker remarked that an "isothermal line" (i.e. the climate) had made Kansas unsuitable to slavery, angering pro-slavery leaders in Kansas and across the United States. In October 1857, the Lecompton government organized territorial elections that resulted in a pro-slavery legislature, despite Walker's discovery of fraud in several counties.

The convention framed a pro-slavery state constitution (known as the " Lecompton Constitution") and, rather than risking a referendum, sent it directly to Buchanan. Though eager for Kansas statehood, even Buchanan was forced to reject the entrance of Kansas without a state constitutional referendum, and he dispatched federal agents to bring about a compromise. The Lecompton government agreed to a limited referendum in which Kansas would vote not on the constitution overall, but rather merely on whether or not Kansas would allow slavery after becoming a state. The anti-slavery Topeka government boycotted the December 1857 referendum, in which slavery overwhelmingly won the approval of those who did vote. A month later, the Topeka government held its own referendum in which voters overwhelmingly rejected the Lecompton Constitution.

Despite the protests of Walker and two former governors of Kansas, Buchanan decided to accept the Lecompton Constitution. In a December 1857 meeting with Stephen Douglas, the chairman of the Senate Committee on Territories and an important Northern Democrat, Buchanan demanded that all Democrats support the administration's position of admitting Kansas under the Lecompton Constitution. Facing re-election and outraged by the perceived fraud in Kansas, Douglas broke with Buchanan and attacked the Lecompton Constitution. On February 2, Buchanan transmitted the Lecompton Constitution to Congress. He also transmitted a message that attacked the "revolutionary government" in Topeka, conflating them with the Mormons in Utah. Buchanan made every effort to secure congressional approval, offering favors, patronage appointments, and even cash for votes. The Lecompton Constitution won the approval of the Senate in March, but a combination of Know-Nothings, Republicans, and Northern Democrats defeated the bill in the House. Rather than accepting defeat, Buchanan backed the English Bill, which offered Kansans immediate statehood and vast public lands in exchange for accepting the Lecompton Constitution. Despite the continued opposition of Douglas, the English bill won passage in both houses of Congress.

Despite congressional approval of the constitution, Kansas voters strongly rejected the Lecompton Constitution in an August 1858 referendum. Southerners were outraged that the Lecompton Constitution had been defeated by a supposed Northern conspiracy led by Douglas, while many Northerners now saw Buchanan as a tool of the Southern " Slave Power." Anti-slavery delegates won a majority of the elections to the 1859 state constitutional convention, and Kansas won admission as a free state in the final months of Buchanan's presidency; the Southern senators blocking a free Kansas had withdrawn, because their states had seceded. Guerrilla warfare in the state would continue throughout Buchanan's presidency and extend into 1860s, when it became a relatively minor theater of the wider American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

.

The battle over Kansas escalated into a battle for control of the Democratic Party. On one side were Buchanan, most Southern Democrats, and "doughface" Northern Democrats; on the other side were Douglas and most Northern Democrats, as well as a few Southerners. Douglas's faction continued to support the doctrine of popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty is the principle that the authority of a state and its government are created and sustained by the consent of its people, who are the source of all political power. Popular sovereignty, being a principle, does not imply any ...

, while Buchanan insisted that Democrats respect the ''Dred Scott'' decision and its repudiation of federal interference with slavery in the territories. The struggle lasted the remainder of Buchanan's presidency. Buchanan used his patronage powers to remove Douglas' sympathizers in favor of pro-administration Democrats.

1858 mid-term elections

Douglas's Senate term ended in 1859, so the Illinois legislature elected in 1858 would determine whether Douglas would win re-election. The Senate election was the primary issue of the legislative election, marked by the Lincoln-Douglas debates between Douglas and the Republican candidate, former CongressmanAbraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

. Buchanan, working through federal patronage appointees in Illinois, ran candidates for the legislature in competition with both the Republicans and the Douglas Democrats. This could easily have thrown the election to the Republicans—which showed the depth of Buchanan's animosity toward Douglas.

In his 1858 re-election bid, Douglas defeated Lincoln, who warned that the Supreme Court would soon bar states from excluding slavery. As part of his campaign, Douglas laid out his "Freeport Doctrine

The Freeport Doctrine was articulated by Stephen A. Douglas at the second of the Lincoln-Douglas debates on August 27, 1858, in Freeport, Illinois. Former one-term U.S. Representative Abraham Lincoln was campaigning to take Douglas's U.S. Senate ...

," which held that territorial legislatures retained the de facto right to exclude slavery despite the ''Dred Scott'' decision, because said legislatures could refuse to recognize slavery as property. In the 1858 elections, Douglas forces took control of the Democratic Party throughout the North, except in Buchanan's home state of Pennsylvania, leaving Buchanan with a narrow base of Southern supporters. However, the Freeport Doctrine further diminished Douglas's support in the South, which was already in decline following his refusal to support the Lecompton Constitution.

The division between Northern and Southern Democrats helped the Republicans win a plurality in the House in the elections of 1858. While campaigning for a Republican congressional candidate in New York, Republican Senator William Seward

William Henry Seward (May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States Senator. A determined oppon ...

described the party struggle between Republicans and Democrats as part of a larger "irrepressible conflict" between systems of free and slave labor. Though Seward quickly walked back his remarks and relatively few Northerners actually sought the immediate abolition of slavery in the South, Seward's remarks and the subsequent Republican victories in the 1858 elections caused many in the South to believe that the election of a Republican president would lead to the abolition of slavery. The election losses served as a Northern rebuke to the Buchanan administration, and Republican control of the House allowed Republicans to block much of Buchanan's agenda in the second half of his term.

Continuing tensions over slavery

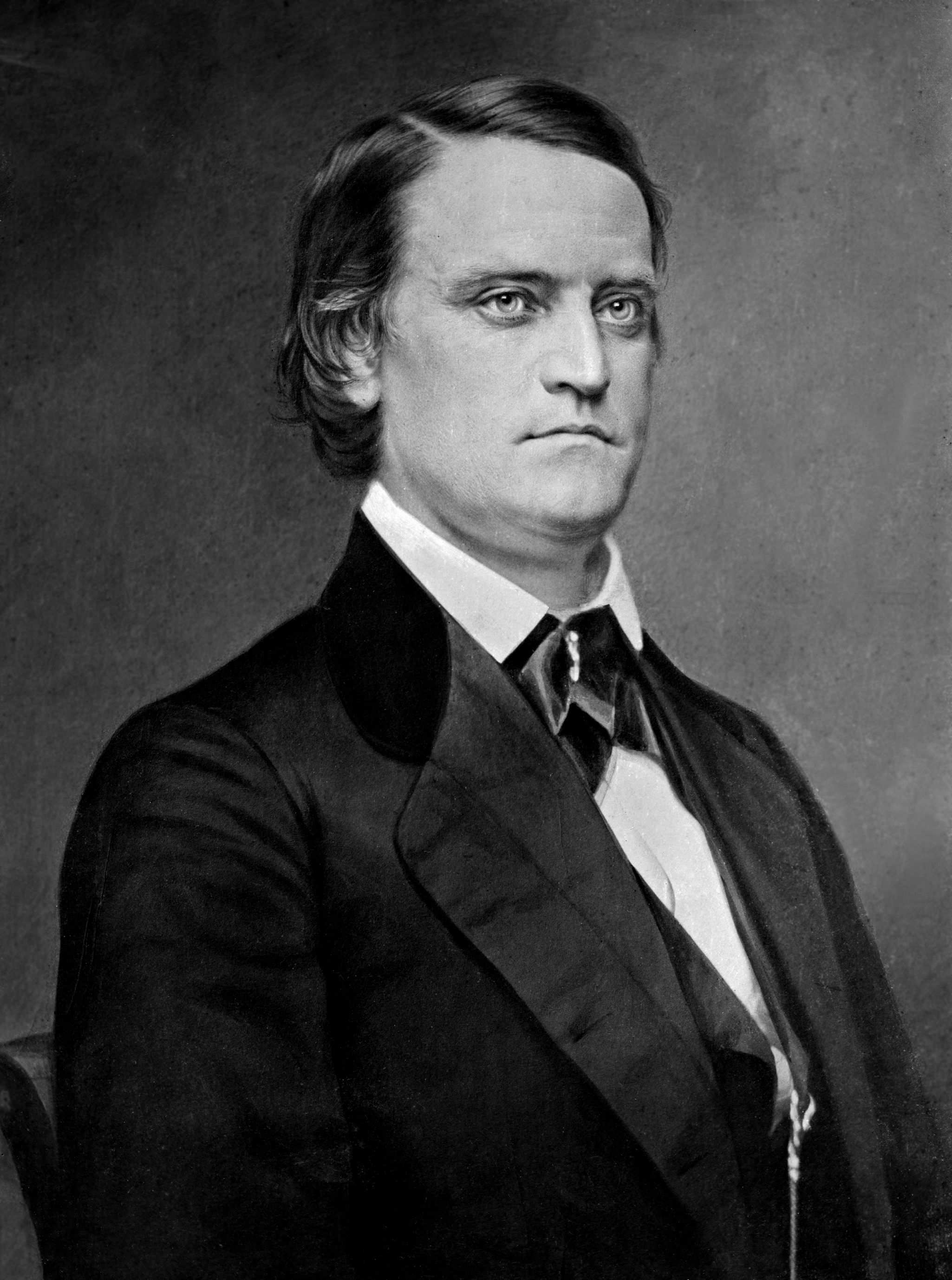

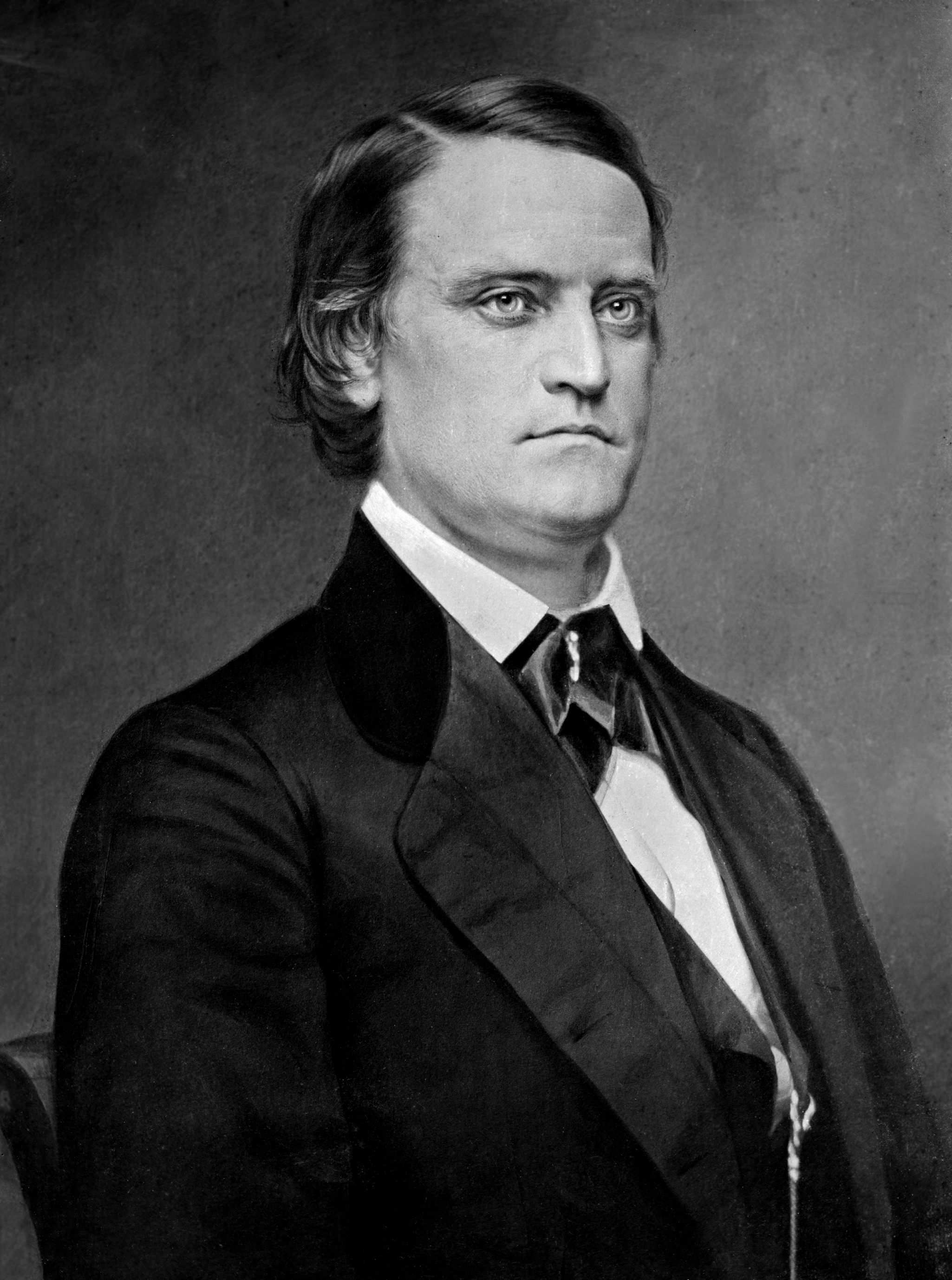

Following the 1858 elections, SenatorJefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives as ...

of Mississippi and fellow Southern radicals sought to pass a federal slave code

The slave codes were laws relating to slavery and enslaved people, specifically regarding the Atlantic slave trade and chattel slavery in the Americas.

Most slave codes were concerned with the rights and duties of free people in regards to ensla ...

that would protect slavery in the territories, thereby closing the loophole contemplated by Douglas's Freeport Doctrine. In February 1859, as debate over the federal slave code began, Davis and other Southerners announced that they would leave the party if the 1860 party platform included popular sovereignty, while Douglas and his supporters likewise stated that they would bolt the party if the party platform included a federal slave code. Despite this continuing debate over slavery in the territories, the decline of Kansas as a major issue allowed unionists to remain a powerful force in the South.

In October 1859, abolitionist John Brown led raid

Raid, RAID or Raids may refer to:

Attack

* Raid (military), a sudden attack behind the enemy's lines without the intention of holding ground

* Corporate raid, a type of hostile takeover in business

* Panty raid, a prankish raid by male college ...

on a federal armory in Harpers Ferry

Harpers Ferry is a historic town in Jefferson County, West Virginia. It is located in the lower Shenandoah Valley. The population was 285 at the 2020 census. Situated at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers, where the U.S. stat ...

, Virginia, in hopes of initiating a slave revolt

A slave rebellion is an armed uprising by enslaved people, as a way of fighting for their freedom. Rebellions of enslaved people have occurred in nearly all societies that practice slavery or have practiced slavery in the past. A desire for freed ...

. Brown's plan failed miserably, and the majority of his party was killed or captured. In the aftermath of the attack, Republican leaders denied any connection to Brown, who was executed in December 1859 by the state of Virginia. Though few leaders in the North approved of Brown's actions, Southerners were outraged, and many accused Republican leaders such as Seward of having masterminded the raid. In his December 1859 annual message to Congress, Buchanan characterized the raid as part of an "open war by the North to abolish slavery in the South," and he called for the establishment of a federal slave code. Senate hearings led by Senator James Murray Mason

James Murray Mason (November 3, 1798April 28, 1871) was an American lawyer and politician. He served as senator from Virginia, having previously represented Frederick County, Virginia, in the Virginia House of Delegates.

A grandson of George Ma ...

of Virginia cleared the Republican Party of responsibility for the raid after a long investigation, but Southern Congressmen remained suspicious of their Republican colleagues.

Foreign policy

Buchanan entered the White House with an ambitious foreign policy centered around establishing U.S. hegemony over Central America at the expense of Great Britain. He hoped to re-negotiate theClayton–Bulwer Treaty

The Clayton–Bulwer Treaty was a treaty signed in 1850 between the United States and the United Kingdom. The treaty was negotiated by John M. Clayton and Sir Henry Bulwer, amidst growing tensions between the two nations over Central America, a ...

, which he viewed as a mistake that limited U.S. influence in the region. He also sought to establish American protectorates over the Mexican states of Chihuahua Chihuahua may refer to:

Places

* Chihuahua (state), a Mexican state

**Chihuahua (dog), a breed of dog named after the state

**Chihuahua cheese, a type of cheese originating in the state

**Chihuahua City, the capital city of the state

**Chihuahua Mu ...

and Sonora

Sonora (), officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Sonora ( en, Free and Sovereign State of Sonora), is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the Federal Entities of Mexico. The state is divided into 72 municipalities; the ...

, partly to serve as a destination for Mormons. Aware of the decrepit state of the Spanish Empire, he hoped to finally achieve his long-term goal of acquiring Cuba, where state slavery still flourished. After long negotiations with the British, he convinced them to agree to cede the Bay Islands Bay Islands may refer to:

* Bay Islands Department, Honduras

* Southern Moreton Bay Islands, Queensland, Australia

See also

* Bay of Islands

* Bay of Isles

* Island Bay, Wellington

* Little Bay Islands

Little Bay Islands is a vacant town in ...

to Honduras

Honduras, officially the Republic of Honduras, is a country in Central America. The republic of Honduras is bordered to the west by Guatemala, to the southwest by El Salvador, to the southeast by Nicaragua, to the south by the Pacific Oce ...

and the Mosquito Coast to Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the coun ...

. However, Buchanan's ambitions in Cuba and Mexico were blocked in the House of Representatives, where the anti-slavery forces strenuously opposed any move to acquire new slave territory. Buchanan also considered buying Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U ...

from the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

, possibly as a colony for Mormon settlers, but the U.S. and Russia were unable to agree upon a price.

In China, the U.S. was neutral in the Second Opium War

The Second Opium War (), also known as the Second Anglo-Sino War, the Second China War, the Arrow War, or the Anglo-French expedition to China, was a colonial war lasting from 1856 to 1860, which pitted the British Empire#Britain's imperial ...

of 1856–58. Buchanan appointed William Bradford Reed

William Bradford Reed (June 30, 1806 – February 18, 1876) was an American attorney, politician, diplomat, academic and journalist from Pennsylvania. He served as a member of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives from 1834 to 1835. He w ...

as Minister to China in 1857–58. Reed helped Buchanan win in 1856 by persuading old-line Whigs to support a Democrat. Reed's goal in China was to negotiate a new treaty that would win for the United States the privileges Britain and France had forced on China in the war. Reed did well. The Treaty of Tientsin

The Treaty of Tientsin, also known as the Treaty of Tianjin, is a collective name for several documents signed at Tianjin (then romanized as Tientsin) in June 1858. The Qing dynasty, Russian Empire, Second French Empire, United Kingdom, and t ...

(1858) granted American diplomats the right to reside in Peking, reduced tariff levels for American goods, and guaranteed the free exercise of religion by foreigners in China. The treaty helped set the roots of what later became Washington's Open Door Policy

The Open Door Policy () is the United States diplomatic policy established in the late 19th and early 20th century that called for a system of equal trade and investment and to guarantee the territorial integrity of Qing China. The policy wa ...

.

In 1858, Buchanan ordered the Paraguay expedition

The Paraguay expedition (1858–1859) was an American diplomatic mission and nineteen-ship squadron ordered by President James Buchanan to South America to demand redress for certain wrongs alleged to have been done by Paraguay, and seize its capi ...

to punish Paraguay

Paraguay (; ), officially the Republic of Paraguay ( es, República del Paraguay, links=no; gn, Tavakuairetã Paraguái, links=si), is a landlocked country in South America. It is bordered by Argentina to the south and southwest, Brazil to t ...

for firing on the , which was on a scientific mission. The punitive expedition resulted in a Paraguayan apology and the payment of an indemnity.

Covode committee

Buchanan and his allies awarded no-bid contracts to political supporters, used government money to wage political campaigns and bribe judges, and sold government property for less than its worth to cronies. According to historian Michael F. Holt, the Buchanan administration was "undoubtedly the most corrupt dministrationbefore the Civil War and one of the most corrupt in American history." In March 1860, the House created the Covode Committee to investigate the administration for evidence of corruption, bribery, and extortion. The committee, with three Republicans and two Democrats, was accused by Buchanan's supporters of being nakedly partisan; they also charged its chairman, Republican CongressmanJohn Covode

John Covode (March 17, 1808 – January 11, 1871) was an American businessman and abolitionist politician. He served three terms in the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania.

Early life

Covode was born in Fairfield Towns ...

, with acting on a personal grudge due to Buchanan's veto of a land grant bill for agricultural colleges. Despite this criticism, the Democratic committee members, as well as Democratic witnesses, were equally enthusiastic in their pursuit of Buchanan as were the Republicans.

The committee was unable to establish grounds for impeaching Buchanan; however, the majority report issued on June 17 exposed corruption and abuse of power among members of his cabinet, as well as allegations (if not impeachable evidence) from the Republican members of the Committee, that Buchanan had attempted to bribe members of Congress in connection with the Lecompton constitution. The Democratic report, issued separately the same day, pointed out that evidence was scarce, but did not refute the allegations; one of the Democratic members, Rep. James Robinson, stated publicly that he agreed with the Republican report even though he did not sign it. Buchanan claimed to have "passed triumphantly through this ordeal" with complete vindication. Nonetheless, Republican operatives distributed thousands of copies of the Covode Committee report throughout the nation as campaign material in that year's presidential election.

Election of 1860

The

The 1860 Democratic National Convention

The 1860 Democratic National Conventions were a series of presidential nominating conventions held to nominate the Democratic Party's candidates for president and vice president in the 1860 election. The first convention, held from April 23 to ...

convened in April 1860 in Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint o ...

. Buchanan had decided to stick to his pledge to serve just one term, but his administration actively sought a successor who would uphold his policies. Stephen Douglas had emerged as the most popular Northern Democratic leader after the 1858 elections, but he had alienated Buchanan and much of the South with his stance on slavery in the territories. Some Southern Democrats, especially those from the Deep South, preferred a Republican president to Douglas because the election of a Republican president would encourage secession. After a long and acrimonious fight, the convention adopted a platform favoring Douglas's conception of popular sovereignty and rejecting a federal slave code. Seven Southern delegation chairmen walked out on the convention in reaction to the party platform.

After Southern leaders bolted from the convention, Caleb Cushing

Caleb Cushing (January 17, 1800 – January 2, 1879) was an American Democratic politician and diplomat who served as a Congressman from Massachusetts and Attorney General under President Franklin Pierce. He was an eager proponent of territoria ...

, a Buchanan ally who had won election as chair of the convention, ruled that the presidential ballot would require a two-thirds majority of all delegates (including the bolters), meaning that the nominee would have to win support from five-sixths of the delegates present. After fifty-seven ballots, all of which Douglas led, the convention adjourned with plans to reconvene in June in Baltimore, Maryland

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore wa ...

. After re-convening, most of the remaining Southern delegates, as well as some Northern delegates loyal to Buchanan, left the convention after losing a vote to re-seat the delegates that had bolted in Charleston. The remaining delegates nominated Douglas for president. Douglas preferred Alexander H. Stephens

Alexander Hamilton Stephens (February 11, 1812 – March 4, 1883) was an American politician who served as the vice president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865, and later as the 50th governor of Georgia from 1882 until his death in ...

as his running mate, but left the decision to the remaining Southern delegates, who eventually picked former Governor Herschel Johnson of Georgia.

The delegates who had bolted from the Charleston and Baltimore conventions met elsewhere in Baltimore. After stating that he did not believe that the South should secede if Republicans won the 1860 election, Vice President Breckinridge was nominated on the first ballot of the convention. Senator Joseph Lane

Joseph "Joe" Lane (December 14, 1801 – April 19, 1881) was an American politician and soldier. He was a state legislator representing Evansville, Indiana, and then served in the Mexican–American War, becoming a general. President James K. ...

of Oregon was nominated as Breckinridge's running mate. Buchanan and former President Franklin Pierce both endorsed Breckinridge and his platform, which called for the federal protection of slavery in the territories. A group of former Whigs opposed to both Breckinridge and the Republicans, and unable to reach an accommodation with Douglas, formed the Constitutional Union Party and nominated John Bell of Tennessee for president and Edward Everett

Edward Everett (April 11, 1794 – January 15, 1865) was an American politician, Unitarian pastor, educator, diplomat, and orator from Massachusetts. Everett, as a Whig, served as U.S. representative, U.S. senator, the 15th governor of Mass ...

of Massachusetts for vice president. The nascent party emphasized unionism and sought to push aside the issue of slavery. Though the party initially hoped to compete in both the North and the South, some Constitutional Unionists in the South endorsed a federal slave code, which destroyed the party's support in the North.

The 1860 Republican National Convention