Premiership of Tony Blair on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A significant achievement of Blair's first term was the signing, on 10 April 1998, of the Belfast Agreement, more commonly referred to as the "Good Friday Agreement". In the Good Friday Agreement, most Northern Irish political parties, together with the UK and Irish Governments, agreed upon an "exclusively peaceful and democratic" framework for the governance of Northern Ireland and a new set of political institutions for the province. In November 1998, Blair became the first UK Prime Minister to address

A significant achievement of Blair's first term was the signing, on 10 April 1998, of the Belfast Agreement, more commonly referred to as the "Good Friday Agreement". In the Good Friday Agreement, most Northern Irish political parties, together with the UK and Irish Governments, agreed upon an "exclusively peaceful and democratic" framework for the governance of Northern Ireland and a new set of political institutions for the province. In November 1998, Blair became the first UK Prime Minister to address

In the 2001 general election campaign, Blair emphasised the theme of improving

In the 2001 general election campaign, Blair emphasised the theme of improving

Blair gave strong support to US President George W. Bush's invasion of Iraq in 2003. He soon became the face of international support for the war, often clashing with French President

Blair gave strong support to US President George W. Bush's invasion of Iraq in 2003. He soon became the face of international support for the war, often clashing with French President

After fighting the 2001 general election on the theme of improving public services, Blair's government raised taxes in 2002 (described by the Conservatives as " stealth taxes") to increase spending on education and health. Blair insisted the increased funding would have to be matched by internal reforms. The government introduced the Foundation Hospitals scheme to allow NHS hospitals financial autonomy, although the eventual shape of the proposals, after an internal Labour Party struggle with

After fighting the 2001 general election on the theme of improving public services, Blair's government raised taxes in 2002 (described by the Conservatives as " stealth taxes") to increase spending on education and health. Blair insisted the increased funding would have to be matched by internal reforms. The government introduced the Foundation Hospitals scheme to allow NHS hospitals financial autonomy, although the eventual shape of the proposals, after an internal Labour Party struggle with

The Labour Party won the 2005 general election held on Thursday 5 May and a third consecutive term in office, for the first time ever. However, Labour won fewer votes in England than the Conservatives. The next day, Blair was invited to form a government by

The Labour Party won the 2005 general election held on Thursday 5 May and a third consecutive term in office, for the first time ever. However, Labour won fewer votes in England than the Conservatives. The next day, Blair was invited to form a government by

After the 2004 Labour Party conference, on 30 September 2004, Blair announced in a BBC interview that he would serve a "full third term" but would not contest a fourth general election. No

After the 2004 Labour Party conference, on 30 September 2004, Blair announced in a BBC interview that he would serve a "full third term" but would not contest a fourth general election. No

online

* Carter, N., & Jacobs, M. (2014). "Explaining radical policy change: the case of climate change and energy policy under the British Labour government 2006–10". ''Public Administration'', 92(1), 125–141. * Faucher-King, F., & Le Galès, P. (2010). ''The new Labour experiment: Change and reform under Blair and Brown'' (Stanford University Press). * * ; Blair and Gordon Brown. * * Powell, M. ed. (2008). ''Modernising the welfare state: The Blair legacy'' (Policy Press). * * * * * Shaw, Eric. "Understanding Labour Party Management under Tony Blair." ''Political Studies Review'' 14.2 (2016): 153-16

online

* *

online

* Daddow, O. (2013). "Margaret Thatcher, Tony Blair and the Eurosceptic Tradition in Britain" ''The British Journal of Politics and International Relations'' 15#2, 210–227. * Dyson, S. B. (2013). ''The Blair identity: leadership and foreign policy'' (Manchester University Press). * Henke, Marina E. (2018) "Tony Blair’s gamble: The Middle East Peace Process and British participation in the Iraq 2003 campaign." ''British Journal of Politics and International Relations'' 20.4 (2018): 773–78

online

* Mölder, Holger. (2018) "British Approach to the European Union: From Tony Blair to David Cameron." in ''Brexit'' (Springer, Cham, 2018) pp. 153–17

online

* Nelson, Ian. (2019

"Infinite conditions on the road to peace: the second New Labour government’s foreign policy approach to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict after 9/11"

''

Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He previously served as Leader of t ...

's term as the prime minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As modern p ...

began on 2 May 1997 when he accepted an invitation of Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states durin ...

to form a government, succeeding John Major

Sir John Major (born 29 March 1943) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1990 to 1997, and as Member of Parliament (MP) for Huntingdon, formerly Hunting ...

of the Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

, and ended on 27 June 2007 upon his resignation. While serving as prime minister, Blair also served as the first lord of the treasury

The first lord of the Treasury is the head of the Lords Commissioners of the Treasury exercising the ancient office of Lord High Treasurer in the United Kingdom, and is by convention also the prime minister. This office is not equivalent to the ...

, minister for the civil service

In the Government of the United Kingdom, the minister for the Civil Service is responsible for regulations regarding His Majesty's Civil Service, the role of which is to assist the governments of the United Kingdom in formulating and implementin ...

and leader of the Labour Party.

As prime minister, Blair used the term "New Labour

New Labour was a period in the history of the British Labour Party from the mid to late 1990s until 2010 under the leadership of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. The name dates from a conference slogan first used by the party in 1994, later seen ...

" to distinguish his pro- market policies from the more socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

policies which the party had espoused in the past. Many of his policies reflected a centrist

Centrism is a political outlook or position involving acceptance or support of a balance of social equality and a degree of social hierarchy while opposing political changes that would result in a significant shift of society strongly to the ...

"Third Way" political philosophy. In domestic government policy, Blair significantly increased public spending on healthcare and education while also introducing controversial market-based reforms in these areas. In addition, Blair's tenure saw the introduction of a minimum wage

A minimum wage is the lowest remuneration that employers can legally pay their employees—the price floor below which employees may not sell their labor. Most countries had introduced minimum wage legislation by the end of the 20th century. B ...

, tuition fees for higher education, constitutional reform

A constitutional amendment is a modification of the constitution of a polity, organization or other type of entity. Amendments are often interwoven into the relevant sections of an existing constitution, directly altering the text. Conversely, t ...

such as devolution in Scotland and Wales and progress in the Northern Ireland peace process. The UK economy performed well and the real incomes of Britons grew 18% during 1997–2006. Blair kept to Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

commitments not to increase income tax in the first term although rates of employee's National Insurance

National Insurance (NI) is a fundamental component of the welfare state in the United Kingdom. It acts as a form of social security, since payment of NI contributions establishes entitlement to certain state benefits for workers and their fami ...

(a payroll levy) were increased. He also presided over a significant expansion of the welfare state during his time in office, which led to a significant reduction in relative poverty.

Blair's governments enacted constitutional reforms, removing most hereditary peer

The hereditary peers form part of the peerage in the United Kingdom. As of September 2022, there are 807 hereditary peers: 29 dukes (including five royal dukes), 34 marquesses, 190 earls, 111 viscounts, and 443 barons (disregarding subsidi ...

s from the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

, while also establishing the UK's Supreme Court and reforming the office of lord chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. Th ...

(thereby separating judicial powers from the legislative and executive branches). His government held referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a Representative democr ...

s in which Scottish and Welsh electorates voted in favour of devolved administration

Devolution is the statutory delegation of powers from the central government of a sovereign state to govern at a subnational level, such as a regional or local level. It is a form of administrative decentralization. Devolved territories h ...

, paving the way for the establishment of the Scottish Parliament

The Scottish Parliament ( gd, Pàrlamaid na h-Alba ; sco, Scots Pairlament) is the devolved, unicameral legislature of Scotland. Located in the Holyrood area of the capital city, Edinburgh, it is frequently referred to by the metonym Holyr ...

and Welsh Assembly

The Senedd (; ), officially known as the Welsh Parliament in English and () in Welsh, is the devolved, unicameral legislature of Wales. A democratically elected body, it makes laws for Wales, agrees certain taxes and scrutinises the Welsh ...

in 1999. He was also involved in negotiating the Good Friday Agreement. His time in office occurred during a period of continued economic growth, but this became increasingly dependent on mounting debt. In 1997, his government gave the Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the English Government's banker, and still one of the bankers for the Government o ...

powers to set interest rates autonomously, and he later oversaw a large increase in public spending, especially in healthcare and education.

Blair championed multiculturalism

The term multiculturalism has a range of meanings within the contexts of sociology, political philosophy, and colloquial use. In sociology and in everyday usage, it is a synonym for " ethnic pluralism", with the two terms often used interchang ...

and, between 1997 and 2007, immigration rose considerably, especially after his government welcomed immigration from the new EU member states in 2004. This provided a cheap and flexible labour supply but also fuelled Euroscepticism

Euroscepticism, also spelled as Euroskepticism or EU-scepticism, is a political position involving criticism of the European Union (EU) and European integration. It ranges from those who oppose some EU institutions and policies, and seek refor ...

, especially among some of his party's core voters. His other social policies were generally progressive; he introduced the National Minimum Wage Act 1998

The National Minimum Wage Act 1998 creates a minimum wage across the United Kingdom.. E McGaughey, ''A Casebook on Labour Law'' (Hart 2019) ch 6(1) From 1 April 2022 this was £9.50 for people age 23 and over, £9.18 for 21- to 22-year-olds, £6 ...

, the Human Rights Act 1998

The Human Rights Act 1998 (c. 42) is an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom which received royal assent on 9 November 1998, and came into force on 2 October 2000. Its aim was to incorporate into UK law the rights contained in the European Con ...

, and the Freedom of Information Act 2000

The Freedom of Information Act 2000 (c. 36) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that creates a public "right of access" to information held by public authorities. It is the implementation of freedom of information legislation in ...

, and the Civil Partnership Act 2004. He declared himself tough on crime and oversaw increasing incarceration rates and new anti-social behaviour legislation, despite contradictory evidence about the change in crime rates. He was in office when the 7 July 2005 London bombings

The 7 July 2005 London bombings, often referred to as 7/7, were a series of four coordinated suicide attacks carried out by Islamic terrorists in London that targeted commuters travelling on the city's public transport system during the mo ...

took place and introduced a range of anti-terror legislation.

Blair oversaw British interventions in Kosovo

Kosovo ( sq, Kosova or ; sr-Cyrl, Косово ), officially the Republic of Kosovo ( sq, Republika e Kosovës, links=no; sr, Република Косово, Republika Kosovo, links=no), is a international recognition of Kosovo, partiall ...

in 1999 and Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone,)]. officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered by Liberia to the southeast and Guinea surrounds the northern half of the nation. Covering a total area of , Sierr ...

in 2000, which were generally perceived as successful. In 2003, Blair supported George W. Bush after he ordered an invasion of Iraq

The 2003 invasion of Iraq was a United States-led invasion of the Republic of Iraq and the first stage of the Iraq War. The invasion phase began on 19 March 2003 (air) and 20 March 2003 (ground) and lasted just over one month, including 26 ...

, alleging alongside Bush that the Saddam Hussein

Saddam Hussein ( ; ar, صدام حسين, Ṣaddām Ḥusayn; 28 April 1937 – 30 December 2006) was an Iraqi politician who served as the fifth president of Iraq from 16 July 1979 until 9 April 2003. A leading member of the revolutio ...

regime possessed weapons of mass destruction

A weapon of mass destruction (WMD) is a chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, or any other weapon that can kill and bring significant harm to numerous individuals or cause great damage to artificial structures (e.g., buildings), natu ...

. Intense criticism came when neither WMD stockpiles nor evidence of an operational relationship with al-Qaeda were found. The Afghanistan and Iraq wars continued throughout the rest of Blair's premiership. In 2006, Blair announced that he would resign as prime minister and Labour leader within a year. He resigned on 27 June 2007 and was succeeded by Gordon Brown

James Gordon Brown (born 20 February 1951) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Labour Party from 2007 to 2010. He previously served as Chancellor of the Exchequer in Tony ...

, who had been his chancellor of the Exchequer since 1997.

At various points in his premiership, Blair was among both the most popular and unpopular prime ministers in UK history. He received the highest recorded approval ratings during his first few years in office, but also one of the lowest such ratings during the Iraq War. Blair had notable electoral successes and reforms, though his legacy remains controversial largely due to the Iraq War and his relationship with Bush.

First term (1997–2001)

Independence for the Bank of England

Immediately after taking office,Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Ch ...

Gordon Brown

James Gordon Brown (born 20 February 1951) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Labour Party from 2007 to 2010. He previously served as Chancellor of the Exchequer in Tony ...

gave the Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the English Government's banker, and still one of the bankers for the Government o ...

the power to set the UK base rate of interest autonomously, as agreed in 1992 in the Maastricht Treaty

The Treaty on European Union, commonly known as the Maastricht Treaty, is the foundation treaty of the European Union (EU). Concluded in 1992 between the then-twelve member states of the European Communities, it announced "a new stage in the ...

. This decision was popular with the British financial establishment in London, which the Labour Party had been courting since the early-1990s. Together with the Government's decision to remain within projected Conservative spending limits for its first two years in office, it helped to reassure sceptics of the Labour Party's fiscal "prudence". Associated changes moved regulation of banks away from the Bank of England to the Financial Services Authority- and these changes were unwound in 2013 following perceived failures by the FSA in the banking crisis.

Euro

The Blair ministry decided against joining theEurozone

The euro area, commonly called eurozone (EZ), is a currency union of 19 member states of the European Union (EU) that have adopted the euro (€) as their primary currency and sole legal tender, and have thus fully implemented EMU pol ...

, and adopting the euro

The euro ( symbol: €; code: EUR) is the official currency of 19 out of the member states of the European Union (EU). This group of states is known as the eurozone or, officially, the euro area, and includes about 340 million citizens . ...

as the currency to replace the pound sterling

Sterling (abbreviation: stg; Other spelling styles, such as STG and Stg, are also seen. ISO code: GBP) is the currency of the United Kingdom and nine of its associated territories. The pound ( sign: £) is the main unit of sterling, and ...

. This decision was generally supported by the British public, and by all political parties in the UK, as well as the media.

On 24 June 1998, '' The Sun'' had famously put the front-page headline "Is THIS the most dangerous man in Britain?" beside a photograph of Blair, when it was still uncertain whether he would lead Britain into the Euro, or keep the sterling currency.

Domestic politics

In the early years of his first term, Blair relied on political advice from a close circle of his staff, among whom was hispress secretary

A press secretary or press officer is a senior advisor who provides advice on how to deal with the news media and, using news management techniques, helps their employer to maintain a positive public image and avoid negative media coverage.

Dut ...

and official spokesman Alastair Campbell

Alastair John Campbell (born 25 May 1957) is a British journalist, author, strategist, broadcaster and activist known for his roles during Tony Blair's leadership of the Labour Party. Campbell worked as Blair's spokesman and campaign director ...

. Campbell was permitted to give orders to civil servants, who had previously taken instructions only from ministers. Unlike some of his predecessors, Campbell was a political appointee and had not come up through the Civil Service

The civil service is a collective term for a sector of government composed mainly of career civil servants hired on professional merit rather than appointed or elected, whose institutional tenure typically survives transitions of political leaders ...

. Despite his overtly political role, he was paid from public funds

Government spending or expenditure includes all government consumption, investment, and transfer payments. In national income accounting, the acquisition by governments of goods and services for current use, to directly satisfy the individual o ...

as a civil servant. Also in Blair's team were a number of strong female aides, who acted as gatekeepers and go-betweens, including Anji Hunter, Kate Garvey

Kate Garvey (born ) is an English public relations executive and a former aide to British prime minister Tony Blair. She is a co-founder of Project Everyone, a communications and campaigning agency promoting the United Nations' Sustainable Dev ...

, Ruth Turner

Ruth Dixon Turner (1914 – April 30, 2000) was a pioneering U.S. marine biologist and malacologist. She was the world's expert on Teredinidae or shipworms, a taxonomic family of wood-boring bivalve mollusks which severely damage wooden mari ...

and Sally Morgan.

A significant achievement of Blair's first term was the signing, on 10 April 1998, of the Belfast Agreement, more commonly referred to as the "Good Friday Agreement". In the Good Friday Agreement, most Northern Irish political parties, together with the UK and Irish Governments, agreed upon an "exclusively peaceful and democratic" framework for the governance of Northern Ireland and a new set of political institutions for the province. In November 1998, Blair became the first UK Prime Minister to address

A significant achievement of Blair's first term was the signing, on 10 April 1998, of the Belfast Agreement, more commonly referred to as the "Good Friday Agreement". In the Good Friday Agreement, most Northern Irish political parties, together with the UK and Irish Governments, agreed upon an "exclusively peaceful and democratic" framework for the governance of Northern Ireland and a new set of political institutions for the province. In November 1998, Blair became the first UK Prime Minister to address Dáil Éireann

Dáil Éireann ( , ; ) is the lower house, and principal chamber, of the Oireachtas (Irish legislature), which also includes the President of Ireland and Seanad Éireann (the upper house).Article 15.1.2º of the Constitution of Ireland rea ...

.

Blair's first term saw an extensive programme of changes to the constitution. The Human Rights Act was introduced in 1998; a Scottish Parliament

The Scottish Parliament ( gd, Pàrlamaid na h-Alba ; sco, Scots Pairlament) is the devolved, unicameral legislature of Scotland. Located in the Holyrood area of the capital city, Edinburgh, it is frequently referred to by the metonym Holyr ...

and a Welsh Assembly

The Senedd (; ), officially known as the Welsh Parliament in English and () in Welsh, is the devolved, unicameral legislature of Wales. A democratically elected body, it makes laws for Wales, agrees certain taxes and scrutinises the Welsh ...

were established following referendums held with a majority voting in favour; most hereditary peers were removed from the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

in 1999

File:1999 Events Collage.png, From left, clockwise: The funeral procession of King Hussein of Jordan in Amman; the 1999 İzmit earthquake kills over 17,000 people in Turkey; the Columbine High School massacre, one of the first major school shoot ...

; the Greater London Authority

The Greater London Authority (GLA), colloquially known by the metonym "City Hall", is the devolved regional governance body of Greater London. It consists of two political branches: the executive Mayoralty (currently led by Sadiq Khan) and t ...

and the position of Mayor of London

The mayor of London is the chief executive of the Greater London Authority. The role was created in 2000 after the Greater London devolution referendum in 1998, and was the first directly elected mayor in the United Kingdom.

The current m ...

were established in 2000; and the Freedom of Information Act Freedom of Information Act may refer to the following legislations in different jurisdictions which mandate the national government to disclose certain data to the general public upon request:

* Freedom of Information Act 1982, the Australian act

* ...

was passed later in the same year, with its provisions coming into effect over the following decade. This last Act disappointed campaigners, whose hopes had been raised by a 1997 White Paper

A white paper is a report or guide that informs readers concisely about a complex issue and presents the issuing body's philosophy on the matter. It is meant to help readers understand an issue, solve a problem, or make a decision. A white paper ...

which had promised more robust legislation. Blair later described the FoIA as one of his "biggest regrets", writing in his autobiography, "I quake at the imbecility of it." Whether the House of Lords should be fully appointed, fully elected, or be subject to a combination of the two remains a disputed question to the present day. 2003 saw a series of inconclusive votes on the subject in the House of Commons.

Significant change took place to legislation relating to rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender

A transgender (often abbreviated as trans) person is someone whose gender identity or gender expression does not correspond with their sex assigned at birth. Many transgender people experience dysphoria, which they seek to alleviate through ...

people during Blair's period in office. During his first term, the age of consent

The age of consent is the age at which a person is considered to be legally competent to consent to sexual acts. Consequently, an adult who engages in sexual activity with a person younger than the age of consent is unable to legally cla ...

for homosexuals was equalised at sixteen years of age (see Sexual Offences (Amendment) Act 2000) and the ban on homosexuals in the armed forces was lifted. Subsequently, in 2005, a Civil Partnership

A civil union (also known as a civil partnership) is a legally recognized arrangement similar to marriage, created primarily as a means to provide recognition in law for same-sex couples. Civil unions grant some or all of the rights of marriage ...

Act came into effect, allowing gay couples to form legally recognised partnerships with the same rights as a traditional heterosexual marriage. At the end of September 2006, more than 30,000 Britons had entered into Civil Partnerships as a result of this law. Adoption by same-sex couples was legalised, and discrimination in the workplace (Employment Equality (Sexual Orientation) Regulations 2003

The Employment Equality (Sexual Orientation) Regulations 2003 were secondary legislation in the United Kingdom, which prohibited employers unreasonably discriminating against employees on grounds of sexual orientation, perceived sexual orientati ...

), and in relation to the provision of goods and services ( Equality Act (Sexual Orientation) Regulations) were both made illegal. Transgender people were given the right to change their birth certificate

A birth certificate is a vital record that documents the birth of a person. The term "birth certificate" can refer to either the original document certifying the circumstances of the birth or to a certified copy of or representation of the ensui ...

to reflect their new gender as a result of the Gender Recognition Act 2004

The Gender Recognition Act 2004 is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that allows people who have gender dysphoria to change their legal gender. It came into effect on 4 April 2005.

Operation of the law

The Gender Recognition A ...

.

Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He previously served as Leader of t ...

's touch was less sure with regard to the Millennium Dome

The Millennium Dome was the original name of the large dome-shaped building on the Greenwich Peninsula in South East London, England, which housed a major exhibition celebrating the beginning of the third millennium. As of 2022, it is the ni ...

project. The incoming government greatly expanded the size of the project and consequently increased expectations of what would be delivered. Just before its opening, Blair claimed the Dome would be "a triumph of confidence over cynicism, boldness over blandness, excellence over mediocrity". In the words of BBC correspondent Robert Orchard

Robert Orchard is a freelance British journalist and lecturer.

One of three children born to a Devonshire farmer and a Welsh nurse, he was educated at a grammar school in mid-Devon and read Politics, Philosophy and Economics (PPE) at Corpus ...

, "the Dome was to be highlighted as a glittering New Labour achievement in the next election manifesto".

Social policies

During his first term as Prime Minister, Blair raised taxes; introduced aNational Minimum Wage

The National Minimum Wage Act 1998 creates a minimum wage across the United Kingdom.. E McGaughey, ''A Casebook on Labour Law'' (Hart 2019) ch 6(1) From 1 April 2022 this was £9.50 for people age 23 and over, £9.18 for 21- to 22-year-olds, £ ...

and some new employment rights; introduced significant constitutional reforms; promoted new rights for gay people in the Civil Partnership Act 2004; and signed treaties integrating the UK more closely with the EU. He introduced substantial market-based reforms in the education and health sectors; introduced student tuition fees; sought to reduce certain categories of welfare payments, and introduced tough anti-terrorism and identity card legislation. Under Blair's government, the amount of new legislation increased which attracted criticism. Blair increased police powers by adding to the number of arrestable offences, compulsory DNA recording and the use of dispersal orders.

According to one study, in terms of promoting social equality, the first Blair Government "turned out to be the most redistributive in decades; it ran Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, (11 March 1916 – 24 May 1995) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from October 1964 to June 1970, and again from March 1974 to April 1976. He ...

's 1960s' government close." From 1997 to 2005, for instance, all the benefits targeted on children through Tax Credits, Child Benefit and Income Support had gone up by 72% in real terms. Improvements were also made in financial support to pensioners, and by 2004, the poorest third of pensioners were £1,750 a year better off than under the system as it used to be. As a means of reducing energy costs and therefore the incidence of fuel poverty, a new programme of grants for cavity wall and loft insulation and for draught proofing was launched, with some 670,000 homes taking up the scheme. Various adjustments were also made in social welfare benefits. Families were allowed to earn a little more before Housing Benefit was cut, and the benefit was raised for families where the main earner worked part-time, while 2,000,000 pensioners were offered automatic help with their council tax bills, worth £400 each, although many did not take advantage of this benefit. According to one study, the Blair ministry's record on benefits, taken in the round, was "unprecedented", with 3.7% real terms growth each year from 2002 to 2005.Better of Worse? Has Labour Delivered? By Polly Toynbee and David Walker

Under the years of the Blair ministry, expenditure on social services was increased, while various anti-poverty measures were introduced. From 2001 to 2005, public spending increased by an average of 4.8% in real terms, while spending on transport went up by 8.5% per annum, health by 8.2% per annum, and education by 5.4% per annum. Between 1997 and 2005, child poverty was more than halved in absolute terms as a result of measures such as the extension of maternity pay, increases in child benefit, and by the growth in the numbers of people in employment. During that same period, the number of pensioners living in poverty fell by over 75% in absolute terms as a result of initiatives such as the introduction of Winter Fuel Payments, the reduction of VAT on fuel, and the introduction of a Minimum Income Guarantee. To reduce poverty traps for those making the transition from welfare to work, a minimum wage was established, together with a Working Tax Credit and a Child Tax Credit. Together with various tax credit schemes to supplement low earnings, the Blair Government's policies significantly increased the earnings of the lowest income decile.Ten Years of New Labour edited by Matt Beech and Simon Lee In addition, under the Working Time Regulations of 1998, British workers gained a statutory entitlement to paid holidays.

Between 1997 and 2003, spending on early years education and childcare rose in real terms from £2.0 billion to £3.6 billion. During Blair's first term in office, 100 "Early Excellence" centres opened, together with new nurseries, while 500 Sure Start projects began. Although the number of children fell, the amount of state support to families with children increased, with money paid only to them (child contingent support) going up by 52% in real terms from 1999 to 2005. The Blair ministry also extended to three-year-olds the right to a free nursery place for half a day Monday to Friday. Tax credits assisted some 300,000 families (at January 2004) with childcare costs, while the 2004 budget exempted the first £50 of weekly payments to nannies and childminders from tax and National Insurance, restricted to couples earning not more than £43,000 per annum. The Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 extended a legal right to walk to about 3,200 square miles of open countryside, mainly in the North of England.

During its first year in office, the Blair Government made the controversial decision of cutting Lone Parent Benefit, which led to abstentions amongst many Labour MPs. In March 1998, however, Brown responded in his Budget statement by increasing child benefit by £2.50 a week above the rate of inflation, the largest ever increase in the benefit. Public expenditure on education, health, and social security rose more rapidly under the Blair government than it did under previous Labour governments, the latter due to initiatives such as the introduction of the Working Families Tax Credit and increases in pensions and child benefits. During the Blair Government's time in office, incomes for the bottom 10% of earners increased as a result of transfers through the social security system.

New rights for workers were introduced such as extended parental rights, a significant raising of the maximum compensation figure for unfair dismissal, a restoration of the qualifying period for protection against unfair dismissal to twelve months, and the right to be accompanied by a trade union official during a disciplinary or grievance hearing, whether or not a trade union is recognised. In addition, an Employee Relation Act was passed which introduced for the first time ever, the legal right of employees to trade union representation. In 2003, the Working Families Tax Credit was split into two benefits: a Working Tax Credit which was payable to all those in work, and a Child Tax Credit which was payable to all families with children, whether in work or not. During Blair's time in office, over 2,000,000 people had been lifted out of poverty.

A proportional voting system was introduced for the election of Britain's MEPs, while legislation changing executive structures in local government was passed. Regional Development Agencies were set up in the 8 English regions outside London, and changes were made to the regulation of political parties and referendums, with the introduction of a new Electoral Commission and stricter spending rules. In addition, voting experiments resulted in an opening up of postal voting and reform of electoral registration, while the right of hereditary peers to sit in the House of Lords was largely abolished after 700 years. In addition, the Water Industries Act 1999 ended the right of water companies to disconnect supplies "as a sanction against non-payment."

The Employment Act 2002

The Employment Act 2002c 22 is a UK Act of Parliament, which made a series of amendments to existing UK labour law.

Contents

The Employment Act 2002 contained new rules on maternity, paternity and adoption leave and pay, and changes to the trib ...

extended rights to paternity, maternity, and adoption leave and pay, while the Police Reform Act 2002 established community support officers and reorganised national intelligence gathering. The Adoption and Children Act 2002 enabled unmarried couples to apply to adopt while speeding up adoption procedures, while the Private Hire Vehicles (Carriage of Guide Dogs) Act 2002 banned charges for guide dogs in minicabs. The International Development Act 2002 required spending to be used to reduce poverty and improve the welfare of the poor. The Travel Concessions (Eligibility) Act 2002 equalised the age at which men and women become entitled to travel concessions. Under the Homelessness Act 2002, councils had to adopt homelessness strategies and do more for those homeless through no fault of their own, and the Commonhold and Leasehold Reform Act 2002

The Commonhold and Leasehold Reform Act 2002 (c.15) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It introduced commonhold, a new way of owning land similar to the Australian strata title or the American condominium, into English and Welsh ...

made it easier to convert long-term residential leasehold into freehold through "commonhold" tenures. The British Overseas Territories Act 2002 extended full British citizenship to 200,000 inhabitants of 14 British Overseas Territories, while the Office of Communications Act 2002 set up a new regulatory body known as the Office of Communications (Ofcom). The Enterprise Act 2002

The Enterprise Act 2002 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which made major changes to UK competition law with respect to mergers and also changed the law governing insolvency bankruptcy.

It made cartels illegal with a maximum pri ...

included measures to safeguard consumers, while also reforming bankruptcy and establishing a stronger Office of Fair Trading.

Immigration

Non-European immigration rose significantly during the period from 1997, not least because of thegovernment

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government i ...

's abolition of the primary purpose rule in June 1997. This change made it easier for UK residents to bring foreign spouses into the country.

The former government advisor Andrew Neather in the ''Evening Standard

The ''Evening Standard'', formerly ''The Standard'' (1827–1904), also known as the ''London Evening Standard'', is a local free daily newspaper in London, England, published Monday to Friday in tabloid format.

In October 2009, after be ...

'' stated that the deliberate policy of ministers from late-2000 until early-2008 was to open up the UK to mass migration.

Foreign policy

In 1999, Blair planned and presided over the declaration of theKosovo War

The Kosovo War was an armed conflict in Kosovo that started 28 February 1998 and lasted until 11 June 1999. It was fought by the forces of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (i.e. Serbia and Montenegro), which controlled Kosovo before the war ...

. While in opposition, the Labour Party had criticised the Conservatives for their perceived weakness during the Bosnia

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and Pars pro toto#Geography, often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of Southern Europe, south and southeast Euro ...

n war, and Blair was among those urging a strong line by NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two N ...

against Slobodan Milošević

Slobodan Milošević (, ; 20 August 1941 – 11 March 2006) was a Yugoslav and Serbian politician who was the president of Serbia within Yugoslavia from 1989 to 1997 (originally the Socialist Republic of Serbia, a constituent republic of ...

. Blair was criticised both by those on the left who opposed the war in principle and by some others who believed that the Serbs were fighting a legitimate war of self-defence

Self-defense (self-defence primarily in Commonwealth English) is a countermeasure that involves defending the health and well-being of oneself from harm. The use of the right of self-defense as a legal justification for the use of force ...

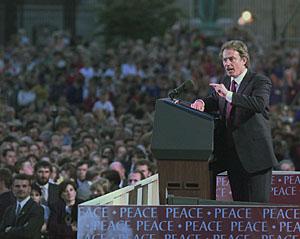

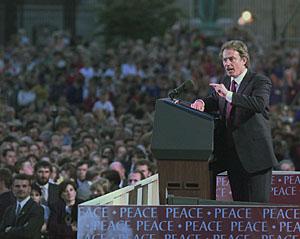

. One month into the war, on 22 April 1999, Blair made a speech in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

setting out his "Doctrine of the International Community". This later became known by the media as the " Blair doctrine", and played a part in Blair's decision to order the British military intervention in the Sierra Leone Civil War in May 2000.

Another significant change in 1997 was the creation of the Department for International Development

, type = Department

, logo = DfID.svg

, logo_width = 180px

, logo_caption =

, picture = File:Admiralty Screen (411824276).jpg

, picture_width = 180px

, picture_caption = Department for International Development (London office) (far right ...

, shifting global development policy away from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office

The Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) is a department of the Government of the United Kingdom. Equivalent to other countries' ministries of foreign affairs, it was created on 2 September 2020 through the merger of the Foreig ...

to an independent ministry with a Cabinet-level minister.

Also in 1999, Blair was awarded the Charlemagne Prize

The Charlemagne Prize (german: Karlspreis; full name originally ''Internationaler Karlspreis der Stadt Aachen'', International Charlemagne Prize of the City of Aachen, since 1988 ''Internationaler Karlspreis zu Aachen'', International Charlemagn ...

by the German city of Aachen

Aachen ( ; ; Aachen dialect: ''Oche'' ; French and traditional English: Aix-la-Chapelle; or ''Aquisgranum''; nl, Aken ; Polish: Akwizgran) is, with around 249,000 inhabitants, the 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia, and the 28th ...

for his contributions to the European ideal and to peace in Europe.

Second term (2001–2005)

In the 2001 general election campaign, Blair emphasised the theme of improving

In the 2001 general election campaign, Blair emphasised the theme of improving public service

A public service is any service intended to address specific needs pertaining to the aggregate members of a community. Public services are available to people within a government jurisdiction as provided directly through public sector agencies ...

s, notably the National Health Service

The National Health Service (NHS) is the umbrella term for the publicly funded healthcare systems of the United Kingdom (UK). Since 1948, they have been funded out of general taxation. There are three systems which are referred to using the " ...

and the State education system. The Conservatives concentrated on opposing British membership of the Euro, which did little to win over floating voters. The Labour Party retained its large parliamentary majority, and Blair became the first Labour Prime Minister to win a full second term. However, the election was notable for a large fall in voter turnout

In political science, voter turnout is the participation rate (often defined as those who cast a ballot) of a given election. This can be the percentage of registered voters, eligible voters, or all voting-age people. According to Stanford Univ ...

.

War in Afghanistan

Following the11 September 2001

The September 11 attacks, commonly known as 9/11, were four coordinated suicide terrorist attacks carried out by al-Qaeda against the United States on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. That morning, nineteen terrorists hijacked four commerc ...

attacks on New York City and Washington DC, Blair was very quick to align the UK with the United States, engaging in a round of shuttle diplomacy

In diplomacy and international relations, shuttle diplomacy is the action of an outside party in serving as an intermediary between (or among) principals in a dispute, without direct principal-to-principal contact. Originally and usually, the proc ...

to help form and maintain an international coalition prior to the 2001 war against Afghanistan. He maintains his diplomatic activity to this day, showing a willingness to visit countries that other world leaders might consider too dangerous to visit. In 2003, he became the first Briton since Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

to be awarded a Congressional Gold Medal

The Congressional Gold Medal is an award bestowed by the United States Congress. It is Congress's highest expression of national appreciation for distinguished achievements and contributions by individuals or institutions. The congressional pract ...

by the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is Bicameralism, bicameral, composed of a lower body, the United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives, and an upper body, ...

for being "a staunch and steadfast ally of the United States of America", although media attention has been drawn to the fact that Blair has yet to attend the ceremony to receive his medal. In 2003, Blair was also awarded an Ellis Island Medal of Honor

The Ellis Island Medal of Honor is an American award founded by the Ellis Island Honors Society (EIHS) (formerly known as the National Ethnic Coalition of Organizations (NECO)), which is presented annually to American citizens, both native-born a ...

for his support of the United States after 9/11—the first non-American to receive the honour.

War in Iraq

Blair gave strong support to US President George W. Bush's invasion of Iraq in 2003. He soon became the face of international support for the war, often clashing with French President

Blair gave strong support to US President George W. Bush's invasion of Iraq in 2003. He soon became the face of international support for the war, often clashing with French President Jacques Chirac

Jacques René Chirac (, , ; 29 November 193226 September 2019) was a Politics of France, French politician who served as President of France from 1995 to 2007. Chirac was previously Prime Minister of France from 1974 to 1976 and from 1986 to ...

, who became the face of international opposition. Widely regarded as a more persuasive speaker than Bush, Blair gave many speeches arguing for the overthrow of Saddam Hussein

Saddam Hussein ( ; ar, صدام حسين, Ṣaddām Ḥusayn; 28 April 1937 – 30 December 2006) was an Iraqi politician who served as the fifth president of Iraq from 16 July 1979 until 9 April 2003. A leading member of the revolutio ...

in the days leading up to the invasion.

Blair's case for war was based on Iraq's alleged possession of weapons of mass destruction

A weapon of mass destruction (WMD) is a chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, or any other weapon that can kill and bring significant harm to numerous individuals or cause great damage to artificial structures (e.g., buildings), natu ...

and consequent violation of UN resolutions. He was wary of making direct appeals for regime change

Regime change is the partly forcible or coercive replacement of one government regime with another. Regime change may replace all or part of the state's most critical leadership system, administrative apparatus, or bureaucracy. Regime change may ...

, since international law

International law (also known as public international law and the law of nations) is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognized as binding between states. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for ...

does not recognise this as a ground for war. A memorandum from a July 2002 meeting that was leaked in April 2005 showed that Blair believed that the British public would support regime change in the right political context; the document, however, stated that legal grounds for such action were weak. On 24 September 2002, the UK Government published a dossier based on the intelligence agencies' assessments of Iraq's weapons of mass destruction. Among the items in the dossier was a recently received intelligence report that "the Iraqi military are able to deploy chemical or biological weapons

A biological agent (also called bio-agent, biological threat agent, biological warfare agent, biological weapon, or bioweapon) is a bacterium, virus, protozoan, parasite, fungus, or toxin that can be used purposefully as a weapon in bioterrorism ...

within 45 minutes of an order to do so". A further briefing paper on Iraq's alleged WMDs was issued to journalists in February 2003. This document was discovered to have taken a large part of its text without attribution from a PhD thesis available on the internet. Where the thesis hypothesised about possible WMDs, the Downing Street

Downing Street is a street in Westminster in London that houses the official residences and offices of the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and the Chancellor of the Exchequer. Situated off Whitehall, it is long, and a few minutes' walk f ...

version presented the ideas as fact. The document subsequently became known as the "Dodgy Dossier

''Iraq – Its Infrastructure of Concealment, Deception and Intimidation'' (more commonly known as the ''Iraq Dossier'', the ''February Dossier'' From pages 35–42 o"The Decision to go to War in Iraq: Ninth Report of Session 2002-03" (PDF). or th ...

".

46,000 British troops, one-third of the total strength of the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurkha ...

(land forces), were deployed to assist with the invasion of Iraq. When after the war, no Weapons of Mass Destruction were found in Iraq, the two dossiers, together with Blair's other pre-war statements, became an issue of considerable controversy. Many Labour Party members, including a number who had supported the war, were among the critics. Successive independent inquiries (including those by the Foreign Affairs Select Committee Select committee may refer to:

*Select committee (parliamentary system) A select committee is a committee made up of a small number of parliamentary members appointed to deal with particular areas or issues originating in the Westminster system o ...

of the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

, the senior judge Lord Hutton, and the former senior civil servant Lord Butler of Brockwell) have found that Blair honestly stated what he believed to be true at the time, though Lord Butler's report did imply that the Government's presentation of the intelligence evidence had been subject to some degree of exaggeration. These findings have not prevented frequent accusations that Blair was deliberately deceitful, and, during the 2005 election campaign, Conservative leader Michael Howard made political capital

Political capital is the term used for an individual's ability to influence political decisions. This capital is built from what the opposition thinks of the politician, so radical politicians will lose capital. Political capital can be understoo ...

out of the issue.

Then Secretary General of the United Nations, Kofi Annan

Kofi Atta Annan (; 8 April 193818 August 2018) was a Ghanaian diplomat who served as the seventh secretary-general of the United Nations from 1997 to 2006. Annan and the UN were the co-recipients of the 2001 Nobel Peace Prize. He was the founde ...

, stated in September 2004 that the invasion was "illegal", but did not state the legal basis for this assertion. Prior to the war, the UK Attorney General Lord Goldsmith, who acts as the Government's legal advisor, had advised Blair that the war was legal.

British Armed Forces

The British Armed Forces, also known as His Majesty's Armed Forces, are the military forces responsible for the defence of the United Kingdom, its Overseas Territories and the Crown Dependencies. They also promote the UK's wider interests, s ...

were active in southern Iraq to stabilise the country in the run-up to the Iraqi elections of January 2005. In October 2004, the UK government agreed to a request from US forces to send a battalion of the Black Watch regiment to the American sector to free up US troops

The United States Armed Forces are the military forces of the United States. The armed forces consists of six service branches: the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, Space Force, and Coast Guard. The president of the United States is the ...

for an assault on Fallujah

Fallujah ( ar, ٱلْفَلُّوجَة, al-Fallūjah, Iraqi pronunciation: ) is a city in the Iraqi province of Al Anbar, located roughly west of Baghdad on the Euphrates. Fallujah dates from Babylonian times and was host to important Je ...

. The subsequent deployment of the Black Watch was criticised by some in Britain on the grounds that its alleged ultimate purpose was to assist George Bush's re-election in the 2004 US presidential election

The 2004 United States presidential election was the 55th quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 2, 2004. The Republican ticket of incumbent President George W. Bush and his running mate incumbent Vice President Dick Chen ...

. As of September 2006, 7,500 British forces remain in Southern Iraq, around the city of Basra

Basra ( ar, ٱلْبَصْرَة, al-Baṣrah) is an Iraqi city located on the Shatt al-Arab. It had an estimated population of 1.4 million in 2018. Basra is also Iraq's main port, although it does not have deep water access, which is han ...

. After the presidential election, Blair tried to use his relationship with President Bush to persuade the US to devote efforts to resolving the Israeli–Palestinian conflict

The Israeli–Palestinian conflict is one of the world's most enduring conflicts, beginning in the mid-20th century. Various attempts have been made to resolve the conflict as part of the Israeli–Palestinian peace process, alongside other ef ...

.

In an interview with David Frost

Sir David Paradine Frost (7 April 1939 – 31 August 2013) was a British television host, journalist, comedian and writer. He rose to prominence during the satire boom in the United Kingdom when he was chosen to host the satirical programme ...

on Al Jazeera

Al Jazeera ( ar, الجزيرة, translit-std=DIN, translit=al-jazīrah, , "The Island") is a state-owned Arabic-language international radio and TV broadcaster of Qatar. It is based in Doha and operated by the media conglomerate Al Jazee ...

in November 2006, Blair appeared to agree with Frost's assessment that the war had been "pretty much of a disaster", although a Downing Street spokesperson denied that this was an accurate reflection of Blair's view.

Domestic politics

After fighting the 2001 general election on the theme of improving public services, Blair's government raised taxes in 2002 (described by the Conservatives as " stealth taxes") to increase spending on education and health. Blair insisted the increased funding would have to be matched by internal reforms. The government introduced the Foundation Hospitals scheme to allow NHS hospitals financial autonomy, although the eventual shape of the proposals, after an internal Labour Party struggle with

After fighting the 2001 general election on the theme of improving public services, Blair's government raised taxes in 2002 (described by the Conservatives as " stealth taxes") to increase spending on education and health. Blair insisted the increased funding would have to be matched by internal reforms. The government introduced the Foundation Hospitals scheme to allow NHS hospitals financial autonomy, although the eventual shape of the proposals, after an internal Labour Party struggle with Gordon Brown

James Gordon Brown (born 20 February 1951) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Labour Party from 2007 to 2010. He previously served as Chancellor of the Exchequer in Tony ...

, allowed for less freedom than Blair had wished. By increasing funding, capacity and redesigning incentives, maximum waits for NHS planned operations fell from 18 months to 18 weeks, and public satisfaction with the NHS almost doubled.

The peace process in Northern Ireland hit a series of problems. In October 2002, the Northern Ireland Assembly

sco-ulster, Norlin Airlan Assemblie

, legislature = Seventh Assembly

, coa_pic = File:NI_Assembly.svg

, coa_res = 250px

, house_type = Unicameral

, house1 =

, leader1_type = S ...

established under the Good Friday Agreement was suspended. Attempts to persuade the IRA to decommission its weapons were unsuccessful, and, in the second set of elections to the Assembly in November 2003, the staunchly unionist Democratic Unionist Party

The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) is a unionist, loyalist, and national conservative political party in Northern Ireland. It was founded in 1971 during the Troubles by Ian Paisley, who led the party for the next 37 years. Currently led by J ...

replaced the more moderate Ulster Unionist Party

The Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) is a unionist political party in Northern Ireland. The party was founded in 1905, emerging from the Irish Unionist Alliance in Ulster. Under Edward Carson, it led unionist opposition to the Irish Home Rule m ...

as Northern Ireland's largest unionist party, making a return to devolved government more difficult. At the same time, Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( , ; en, " eOurselves") is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active throughout both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Gr ...

replaced the more moderate SDLP as the province's largest nationalist party.

On 3 August 2003, Blair became the longest continuously-serving Labour Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, surpassing Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. He was Deputy Prime Mini ...

's six-year term from 1945 to 1951. On 5 February 2005, Blair became the longest serving Labour Prime Minister in British history, surpassing the near eight-year total Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, (11 March 1916 – 24 May 1995) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from October 1964 to June 1970, and again from March 1974 to April 1976. He ...

served over his two terms in office.

The Hutton Inquiry

The Hutton Inquiry was a 2003 judicial inquiry in the UK chaired by Brian Hutton, Baron Hutton, Lord Hutton, who was appointed by the Labour Party (UK), Labour government to investigate the controversial circumstances surrounding the death of Dav ...

into the death of Dr. David Kelly reported on 2 August, ruled that he had committed suicide, and despite widespread expectations that the report would criticise Blair and his government, Hutton cleared the Government of deliberately inserting false intelligence into the September Dossier, while criticising the BBC editorial process which had allowed unfounded allegations to be broadcast. Evidence to the inquiry raised further questions over the use of intelligence in the run-up to the war, and the report did not satisfy opponents of Blair and of the war. After a similar decision by President Bush, Blair set up another inquiry—the Butler Review

The Review of Intelligence on Weapons of Mass Destruction, widely known as the Butler Review after its chairman Robin Butler, Baron Butler of Brockwell, was announced on 3 February 2004 by the British Government and published on 14 July 2004. It ...

—into the accuracy and presentation of the intelligence relating to Iraq's alleged weapons of mass destruction. Opponents of the war, especially the Liberal Democrats, refused to participate in this inquiry, since it did not meet their demands for a full public inquiry

A tribunal of inquiry is an official review of events or actions ordered by a government body. In many common law countries, such as the United Kingdom, Ireland, Australia and Canada, such a public inquiry differs from a royal commission in that ...

into whether the war was justified .

The political fallout from the Iraq War continued to dog Blair's premiership after the Butler Review. On 25 August 2004, Plaid Cymru

Plaid Cymru ( ; ; officially Plaid Cymru – the Party of Wales, often referred to simply as Plaid) is a centre-left to left-wing, Welsh nationalist political party in Wales, committed to Welsh independence from the United Kingdom.

Plaid wa ...

MP Adam Price

Adam Robert Price (born 23 September 1968) is a Welsh politician serving as the Leader of Plaid Cymru since 2018. , he has sat in the Senedd for Carmarthen East and Dinefwr, having previously been a Member of Parliament (MP) for the Carmart ...

announced he would attempt to impeach Blair, hoping to invoke a Parliamentary procedure

Parliamentary procedure is the accepted rules, ethics, and customs governing meetings of an assembly or organization. Its object is to allow orderly deliberation upon questions of interest to the organization and thus to arrive at the sense ...

that has lain dormant for 150 years but has never been abolished. However, of 640 MPs in the House of Commons only 23 backed the Commons motion—officially known as an Early day motion

In the Westminster parliamentary system, an early day motion (EDM) is a motion, expressed as a single sentence, tabled by members of Parliament that formally calls for debate "on an early day". In practice, they are rarely debated in the House ...

—in support of considering "whether there exist sufficient grounds to impeach" Blair (a 24th MP signed the motion but later withdrew his name). The Early Day Motion has now expired.

In April 2004, Blair announced that a referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a Representative democr ...

would be held on the ratification of the EU Constitution. This represented a significant development in British politics: only one nationwide referendum had previously been held (in 1975, on whether the UK should remain in the EEC), though a referendum had been promised if the Government decided to join the Euro, and referendums had been held on devolved structures of government in Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, Wales and Northern Ireland. It was a dramatic change of policy for Blair, who had previously dismissed calls for a referendum unless the constitution fundamentally altered the UK's relationship with the EU. Michael Howard

Michael Howard, Baron Howard of Lympne (born Michael Hecht; 7 July 1941) is a British politician who served as Leader of the Conservative Party and Leader of the Opposition from November 2003 to December 2005. He previously held cabinet posit ...

seized upon this "EU-turn", reminding Blair of his declaration to the 2003 Labour Party conference that "I can only go one way. I haven't got a reverse gear". The referendum was expected to be held in early 2006; however, after the French and Dutch rejections of the constitution, the Blair government announced it was suspending plans for a referendum for the foreseeable future.

During his second term, Blair was increasingly the target for protests. His speech to the 2004 Labour Party conference, for example, was interrupted both by a protester against the Iraq War and by a group that opposed the government's decision to allow the House of Commons to ban fox hunting

Fox hunting is an activity involving the tracking, chase and, if caught, the killing of a fox, traditionally a red fox, by trained foxhounds or other scent hounds. A group of unarmed followers, led by a "master of foxhounds" (or "master of ho ...

.

On 15 September 2004, Blair delivered a speech on the environment and the 'urgent issue' of climate change

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to ...

. In unusually direct language he concluded that "If what the science tells us about climate change is correct, then unabated it will result in catastrophic consequences for our world ... The science, almost certainly, is correct." The action he proposed to take appeared to be based on business and investment rather than legislative or tax-based attempts to reduce carbon dioxide emissions: "it is possible to combine reducing emissions with economic growth ... investment in science and technology and in the businesses associated with it".

Health problems

On 19 October 2003, it emerged Blair had received treatment for anirregular heartbeat

Arrhythmias, also known as cardiac arrhythmias, heart arrhythmias, or dysrhythmias, are irregularities in the heartbeat, including when it is too fast or too slow. A resting heart rate that is too fast – above 100 beats per minute in adults ...

. Having felt ill the previous day, he went to hospital and was diagnosed with supraventricular tachycardia. This was treated by cardioversion

Cardioversion is a medical procedure by which an abnormally fast heart rate ( tachycardia) or other cardiac arrhythmia is converted to a normal rhythm using electricity or drugs. Synchronized electrical cardioversion uses a therapeutic dose ...

and he returned home that night. He was reported to have taken the following day (20 October) more gently than usual and returned to a full schedule on 21 October. Downing Street aides later suggested the palpitations had been brought on by drinking lots of strong coffee at an EU summit and then working-out vigorously in the gym. However, former minister Lewis Moonie

Lewis George Moonie, Baron Moonie (born 25 February 1947) is a British politician. He was the Labour Co-operative Member of Parliament (MP) for Kirkcaldy from 1987 to 2005.

Early life

He attended the Grove Academy in Dundee. He studied medicin ...

, a doctor, said the treatment was more serious than Number 10 had admitted: "Anaesthetising somebody and giving their heart electric shocks is not something you just do in the routine run of medical practice."

In September 2004, in off-the-cuff remarks during an interview with ITV News

ITV News is the branding of news programmes on the British television network ITV. ITV has a long tradition of television news. Independent Television News (ITN) was founded to provide news bulletins for the network in 1955, and has since con ...

, Lord Bragg said Blair was "under colossal strain" over "considerations of his family" and that Blair had thought "things over very carefully." This led to speculation Blair would resign. Although details of a family problem were known by the press, no paper reported them because according to one journalist, to have done so would have breached "the bounds of privacy and media responsibility."

Blair underwent a catheter ablation

Catheter ablation is a procedure used to remove or terminate a faulty electrical pathway from sections of the heart of those who are prone to developing cardiac arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter and Wolff-Parkinson-White syn ...

to correct his irregular heartbeat on 1 October 2004, after announcing the procedure on the previous day, in a series of interviews in which he also declared he would seek a third term as Prime Minister, but not a fourth. The planned procedure was carried out at London's Hammersmith Hospital

Hammersmith Hospital, formerly the Military Orthopaedic Hospital, and later the Special Surgical Hospital, is a major teaching hospital in White City, West London. It is part of Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust in the London Borough ...

.

Third term (2005–2007)

The Labour Party won the 2005 general election held on Thursday 5 May and a third consecutive term in office, for the first time ever. However, Labour won fewer votes in England than the Conservatives. The next day, Blair was invited to form a government by

The Labour Party won the 2005 general election held on Thursday 5 May and a third consecutive term in office, for the first time ever. However, Labour won fewer votes in England than the Conservatives. The next day, Blair was invited to form a government by Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states during ...

. The reduction in the Labour Party's majority (from 167 to 66 seats) and the low share of the popular vote (35%) led to some Labour MPs calling for Blair to leave office sooner rather than later; among them was Frank Dobson, who had served in Blair's cabinet during his first term. However, dissenting voices quickly vanished as Blair took on European leaders over the future direction of the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are located primarily in Europe, Europe. The union has a total area of ...

in June 2005. This election also marks the most recent victory by the Labour Party.

G8 and EU presidencies

The rejection byFrance

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

of the treaty to establish a constitution for the European Union presented Blair with an opportunity to postpone a UK referendum and Foreign Secretary Jack Straw announced that the Parliamentary Bill to enact a referendum was suspended indefinitely. It had previously been agreed that ratification would continue unless the treaty had been rejected by at least five of the 25 European Union member states who must all ratify it. In an address to the European Parliament

The European Parliament (EP) is one of the Legislature, legislative bodies of the European Union and one of its seven Institutions of the European Union, institutions. Together with the Council of the European Union (known as the Council and in ...

, Blair stated: "I believe in Europe as a political project. I believe in Europe with a strong and caring social dimension."

Jacques Chirac held several meetings with Schröder and the pair pressed for the UK to give up the rebate won by Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. She was the first female British prime ...

in 1984. After verbal conflict over several weeks, Blair, along with the leaders of all 25 EU member states, descended on Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

for the EU Summit of 18 June 2005 to attempt to finalise the EU budget for 2007–13. Blair refused to renegotiate the rebate unless the proposals included a compensating overhaul of EU spending, particularly on the Common Agricultural Policy

The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) is the agricultural policy of the European Union. It implements a system of agricultural subsidies and other programmes. It was introduced in 1962 and has since then undergone several changes to reduce the ...

which composes 44% of the EU budget. The CAP stayed as it was agreed upon in 2002 and no decision about the budget was reached under the Luxembourg

Luxembourg ( ; lb, Lëtzebuerg ; french: link=no, Luxembourg; german: link=no, Luxemburg), officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, ; french: link=no, Grand-Duché de Luxembourg ; german: link=no, Großherzogtum Luxemburg is a small lan ...

presidency.

London to host the 2012 Summer Olympics

On 6 July 2005, during the 117thInternational Olympic Committee

The International Olympic Committee (IOC; french: link=no, Comité international olympique, ''CIO'') is a non-governmental sports organisation based in Lausanne, Switzerland. It is constituted in the form of an association under the Swis ...

(IOC) session in Singapore, the IOC announced that the 2012 Summer Olympics

The 2012 Summer Olympics (officially the Games of the XXX Olympiad and also known as London 2012) was an international multi-sport event held from 27 July to 12 August 2012 in London, England, United Kingdom. The first event, th ...

, the Games of the XXX Olympiad, were awarded to London over Paris by only four votes. The competition between Paris and London to host the Games had become increasingly heated particularly after French President Jacques Chirac

Jacques René Chirac (, , ; 29 November 193226 September 2019) was a Politics of France, French politician who served as President of France from 1995 to 2007. Chirac was previously Prime Minister of France from 1974 to 1976 and from 1986 to ...