Post–civil rights era in African-American history on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In African-American history, the post–civil rights era is defined as the time period in the United States since Congressional passage of the

On February 21, 1965,

On February 21, 1965,

"All Rise for the National Anthem of Hip-Hop"

''New York Times'', 29 October 2006. Retrieved on 9 September 2008. In January 1973, gunmen stormed a house in Washington DC, and drowned four African-American children in bathtubs, and shot and killed two men and a boy. The house was occupied by members of the Hanafi Muslim sect, whose leader was in a dispute with the

"An Update on the Demographics of Jonestown"

San Diego State University, March 6, 2019. The religious group, led by

File:1520 Sedwick Ave., Bronx, New York1.JPG, 1520 Sedgwick Avenue where DJ Kool Herc threw his first parties in

The crack cocaine epidemic had a devastating effect on Black America. As early as 1981, reports of crack were appearing in

The crack cocaine epidemic had a devastating effect on Black America. As early as 1981, reports of crack were appearing in

DoJ-DEA-History-1985-1990

In 1984, the distribution and use of crack exploded. In 1984, in some major cities such as

. Box Office Mojo. Accessed Dec. 9, 2011. Set in the early 20th Century, ''The Color Purple'' tells the story of a young Black girl named Celie Harris who faces issues both public and socially hidden, including

File:Michael Jackson 1984.jpg,

File:Jordan elgrafico 1992.jpg,

In 2008 presidential elections, Illinois senator

In 2008 presidential elections, Illinois senator

May 18, 2017 24% of all Black male newlyweds in 2015 married outside their race, compared with 12% of Black female newlyweds.

Despite the gains of the

Despite the gains of the "One in 31: The Long Reach of American Corrections"

, Pew Research Center, released March 2, 2009

Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, and national origin. It prohibits unequal application of voter registration requi ...

, the Voting Rights Act of 1965

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of federal legislation in the United States that prohibits racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson during the height of the civil rights m ...

, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968, major federal legislation that ended legal segregation, gained federal oversight and enforcement of voter registration and electoral practices in states or areas with a history of discriminatory practices, and ended discrimination in renting or buying housing.

Politically, African Americans have made substantial strides in the post–civil rights era. Civil rights leader Jesse Jackson

Jesse Louis Jackson (né Burns; born October 8, 1941) is an American political activist, Baptist minister, and politician. He was a candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1984 and 1988 and served as a shadow U.S. senato ...

ran for the Democratic Party's presidential nomination in 1984

Events

January

* January 1 – The Bornean Sultanate of Brunei gains full independence from the United Kingdom, having become a British protectorate in 1888.

* January 7 – Brunei becomes the sixth member of the Association of Southeas ...

and 1988, attracting more African Americans into politics and unprecedented support and leverage for people of colour in politics. In 2008, Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, Obama was the first Af ...

was elected as the first President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal gove ...

of African descent.

In the same period, African Americans have suffered disproportionate unemployment rates following industrial and corporate restructuring, with a rate of poverty in the 21st century that is equal to that in the 1960s. African Americans have the highest rates of incarceration of any minority group, especially in the southern states of the former Confederacy.

1965–1970

On February 21, 1965,

On February 21, 1965, Malcolm X

Malcolm X (born Malcolm Little, later Malik el-Shabazz; May 19, 1925 – February 21, 1965) was an American Muslim minister and human rights activist who was a prominent figure during the civil rights movement. A spokesman for the Nation of I ...

, an African-American rights activist with national and international prominence, was shot and killed in New York City.

1966 was the last year of publication of '' The Negro Motorist Green Book'', informally known as "The Green Book". It provided advice to African-American travelers, during years of legal segregation and overt discrimination, about places where they could stay, get gas, and eat while traveling cross-country. For example, in 1956 only three New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

motels served African Americans, and most motels and hotels in the South were segregated. Rugh, p. 77. After the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, and national origin. It prohibits unequal application of voter registration requi ...

, the ''Green Book'' largely became obsolete. Hinckley, p. 127.

The African-American cultural holiday Kwanzaa was first celebrated in 1966–1967. Kwanzaa was founded by Maulana Karenga as a Pan-Africanist

Pan-Africanism is a worldwide movement that aims to encourage and strengthen bonds of solidarity between all Indigenous and diaspora peoples of African ancestry. Based on a common goal dating back to the Atlantic slave trade, the movement exte ...

cultural and racial-identity event, as an alternative to cultural events of the dominant society such as Christmas and Hanukkah.

The April 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr., an African-American clergyman and civil rights leader, was fatally shot at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 4, 1968, at 6:01 p.m. CST. He was rushed to St. Joseph's Hospital, where he died at ...

led to protests and riots in multiple U.S. cities, primarily in black-majority communities. Beginning in 1971, Martin Luther King Jr. Day was established as a holiday in numerous cities and states. A U.S. federal holiday was established in King's name in 1986. Since his death, hundreds of streets in the U.S. have been renamed in his honour. King has become a national icon in the history of American liberalism and American progressivism.

Fred Hampton

Fredrick Allen Hampton Sr. (August 30, 1948 – December 4, 1969) was an American activist. He came to prominence in Chicago as deputy chairman of the national Black Panther Party and chair of the Illinois chapter. As a progressive African Ame ...

, a prominent Black Panther

A black panther is the melanistic colour variant of the leopard (''Panthera pardus'') and the jaguar (''Panthera onca''). Black panthers of both species have excess black pigments, but their typical rosettes are also present. They have been ...

activist, was murdered by police while sleeping in Chicago on December 4, 1969.

1970s

On April 8, 1970, the nomination of G. Harrold Carswell to the US Supreme Court was defeated by the US Senate, in part because of his history of racist remarks and actions. On May 27, 1970, the film '' Watermelon Man'' was released, directed by Melvin Van Peebles and starringGodfrey Cambridge

Godfrey MacArthur Cambridge (February 26, 1933 – November 29, 1976) was an American stand-up comic and actor. Alongside Bill Cosby, Dick Gregory, and Nipsey Russell, he was acclaimed by '' Time'' in 1965 as "one of the country's foremost cele ...

.

In 1971 the release of '' Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song'' and ''Shaft

Shaft may refer to:

Rotating machine elements

* Shaft (mechanical engineering), a rotating machine element used to transmit power

* Line shaft, a power transmission system

* Drive shaft, a shaft for transferring torque

* Axle, a shaft around whi ...

'' marked the start of Blaxploitation

Blaxploitation is an ethnic subgenre of the exploitation film that emerged in the United States during the early 1970s. The term, a portmanteau of the words "black" and "exploitation", was coined in August 1972 by Junius Griffin, the president ...

films. The Blaxploitation genre catered to Black male fantasies surrounding violence, sex, the drug trade, pimping and overcoming "The Man".

On April 20, 1971, the Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

, in ''Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education

''Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education'', 402 U.S. 1 (1971), was a landmark United States Supreme Court case dealing with the busing of students to promote integration in public schools. The Court held that busing was an appropriate ...

'', upheld busing

Race-integration busing in the United States (also known simply as busing, Integrated busing or by its critics as forced busing) was the practice of assigning and transporting students to schools within or outside their local school districts in ...

of students to achieve integration. In December 1971, Jesse Jackson

Jesse Louis Jackson (né Burns; born October 8, 1941) is an American political activist, Baptist minister, and politician. He was a candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1984 and 1988 and served as a shadow U.S. senato ...

organized Operation PUSH

Rainbow/PUSH is a Chicago-based nonprofit organization formed as a merger of two nonprofit organizations founded by Jesse Jackson; Operation PUSH (People United to Save Humanity) and the National Rainbow Coalition. The organizations pursue soci ...

in Chicago.

In 1972, Shirley Chisholm

Shirley Anita Chisholm ( ; ; November 30, 1924 – January 1, 2005) was an American politician who, in 1968, became the first black woman to be elected to the United States Congress. Chisholm represented New York's 12th congressional distr ...

became the first major-party African-American candidate for President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal gove ...

and the first woman to run for the Democratic presidential nomination. In 1976, Black History Month

Black History Month is an annual observance originating in the United States, where it is also known as African-American History Month. It has received official recognition from governments in the United States and Canada, and more recently ...

was founded by Professor Carter Woodson and the Association for the Study of Afro-American Life and History.

In 1972, DJ Kool Herc developed the musical blueprint for what later became hip-hop, later playing live shows for high school-age students in the Bronx

The Bronx () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Bronx County, in the state of New York. It is south of Westchester County; north and east of the New York City borough of Manhattan, across the Harlem River; and north of the New ...

, New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

.Hermes, Will"All Rise for the National Anthem of Hip-Hop"

''New York Times'', 29 October 2006. Retrieved on 9 September 2008. In January 1973, gunmen stormed a house in Washington DC, and drowned four African-American children in bathtubs, and shot and killed two men and a boy. The house was occupied by members of the Hanafi Muslim sect, whose leader was in a dispute with the

Nation of Islam

The Nation of Islam (NOI) is a religious and political organization founded in the United States by Wallace Fard Muhammad in 1930.

A black nationalist organization, the NOI focuses its attention on the African diaspora, especially on African ...

. In 1977 the leader of the Hanafi sect led an armed takeover of 3 buildings in Washington DC, taking 149 hostages, to bring attention to the murder of his family. Two people were killed during the incident.

In the 1973 and 1974 MLB seasons, African-American baseball player Hank Aaron sought to pass Babe Ruth’s career home-run record. Between 1973 and 1974, Aaron broke the world record for most mail received in one year with over 950,000 letters. Over one-third of those letters were hate mail letters for beating a white man’s record, including death threats.

Alex Haley

Alexander Murray Palmer Haley (August 11, 1921 – February 10, 1992) was an American writer and the author of the 1976 book '' Roots: The Saga of an American Family.'' ABC adapted the book as a television miniseries of the same name and ...

published his novel '' Roots: The Saga of an American Family'' in 1976; it became a bestseller and generated great levels of interest in African-American genealogy and history. Roots was adapted into an eight part 1977 TV series that attracted a huge audience across the country.

President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he previously served as th ...

appointed Andrew Young to serve as Ambassador to the United Nations in 1977, the first African American to serve in the position. In '' Regents of the University of California v. Bakke'' (1978), the US Supreme Court barred racial quota

Racial quotas in employment and education are numerical requirements for hiring, promoting, admitting and/or graduating members of a particular racial group. Racial quotas are often established as means of diminishing racial discrimination, addr ...

systems in college admissions but affirmed the constitutionality of affirmative action programs giving equal access to minorities.

On November 18, 1978, six hundred and forty eight African-Americans died in the mass murder/suicide of the Peoples Temple

The Peoples Temple of the Disciples of Christ, originally Peoples Temple Full Gospel Church and commonly shortened to Peoples Temple, was an American new religious organization which existed between 1954 and 1978. Founded in Indianapolis, Ind ...

religious group in Jonestown, Guyana

Guyana ( or ), officially the Cooperative Republic of Guyana, is a country on the northern mainland of South America. Guyana is an indigenous word which means "Land of Many Waters". The capital city is Georgetown. Guyana is bordered by the ...

.Rebecca Moore"An Update on the Demographics of Jonestown"

San Diego State University, March 6, 2019. The religious group, led by

Jim Jones

James Warren Jones (May 13, 1931 – November 18, 1978) was an American preacher, political activist and mass murderer. He led the Peoples Temple, a new religious movement, between 1955 and 1978. In what he called "revolutionary suicide ...

, had relocated from California to establish a community in Guyana, South America.

The Atlanta Child Murders between 1979 and 1981 set Atlanta's Black community on edge. At least 28 Black children and teenagers were abducted and murdered in similar circumstances in less than two years before their killer was caught.

the Bronx

The Bronx () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Bronx County, in the state of New York. It is south of Westchester County; north and east of the New York City borough of Manhattan, across the Harlem River; and north of the New ...

, New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

in 1973, considered to be the birth of hip-hop.

File:Sherman Hemsley Isabel Sanford Zara Cully The Jeffersons 1976.JPG, The cast of ''The Jeffersons

''The Jeffersons'' is an American sitcom television series that was broadcast on CBS from January 18, 1975, to July 2, 1985, lasting 11 seasons and a total of 253 episodes. ''The Jeffersons'' is one of the longest-running sitcoms in history, ...

'' in 1976. ''The Jeffersons'' ran from 1975 to 1985, and was the second-longest running TV series with a mainly African-American cast.

File:Peoples Temple members attended an anti-eviction rally at the I-Hotel in January 1977.jpg, Followers of Jim Jones

James Warren Jones (May 13, 1931 – November 18, 1978) was an American preacher, political activist and mass murderer. He led the Peoples Temple, a new religious movement, between 1955 and 1978. In what he called "revolutionary suicide ...

in San Francisco in January 1977

1980s

In 1982,Michael Jackson

Michael Joseph Jackson (August 29, 1958 – June 25, 2009) was an American singer, songwriter, dancer, and philanthropist. Dubbed the " King of Pop", he is regarded as one of the most significant cultural figures of the 20th century. Over ...

released ''Thriller

Thriller may refer to:

* Thriller (genre), a broad genre of literature, film and television

** Thriller film, a film genre under the general thriller genre

Comics

* ''Thriller'' (DC Comics), a comic book series published 1983–84 by DC Comics i ...

'', which became the best-selling album of all time.

The Miracle Valley shootout in October 1982 saw two Black churchgoers killed and seven Arizona law enforcement officers injured.

In 1983, Guion Bluford became the first African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

to go into space in NASA's program. Established by legislation in 1983, Martin Luther King Jr. Day was first celebrated as a national holiday on January 20, 1986.

Alice Walker

Alice Malsenior Tallulah-Kate Walker (born February 9, 1944) is an American novelist, short story writer, poet, and social activist. In 1982, she became the first African-American woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, which she was awa ...

received the Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prize () is an award for achievements in newspaper, magazine, online journalism, literature, and musical composition within the United States. It was established in 1917 by provisions in the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made ...

in 1983 for her novel ''The Color Purple

''The Color Purple'' is a 1982 epistolary novel by American author Alice Walker which won the 1983 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and the National Book Award for Fiction.

''. In September 1983, Vanessa L. Williams became the first African American to win the title of Miss America

Miss America is an annual competition that is open to women from the United States between the ages of 17 and 25. Originating in 1921 as a "bathing beauty revue", the contest is now judged on competitors' talent performances and interviews. As ...

as Miss America 1984.

The crack cocaine epidemic had a devastating effect on Black America. As early as 1981, reports of crack were appearing in

The crack cocaine epidemic had a devastating effect on Black America. As early as 1981, reports of crack were appearing in Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world ...

, San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the eighth most populous city in the United States ...

, Miami

Miami ( ), officially the City of Miami, known as "the 305", "The Magic City", and "Gateway to the Americas", is a coastal metropolis and the county seat of Miami-Dade County in South Florida, United States. With a population of 442,241 at ...

, and Houston

Houston (; ) is the most populous city in Texas, the most populous city in the Southern United States, the fourth-most populous city in the United States, and the sixth-most populous city in North America, with a population of 2,304,580 ...

." DEA History Book, 1876–1990" (drug usage & enforcement), US Department of Justice

The United States Department of Justice (DOJ), also known as the Justice Department, is a federal executive department of the United States government tasked with the enforcement of federal law and administration of justice in the United Stat ...

, 1991, USDoJ.gov webpageDoJ-DEA-History-1985-1990

In 1984, the distribution and use of crack exploded. In 1984, in some major cities such as

New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

, Houston, Los Angeles, and Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at t ...

, one dosage unit of crack could be obtained for as little as $2.50 ().

Between 1984 and 1989, the homicide rate for black males aged 14 to 17 more than doubled, and the homicide rate for black males aged 18 to 24 increased nearly as much. During this period, the black community also suffered a 20%–100% increase in fetal death rates, low birth-weight babies, weapons arrests, and the number of children in foster care.

The beginning of the crack epidemic coincided with the rise of hip hop music in the Black community in the mid-1980s, strongly influencing the evolution of hardcore hip hop

Hardcore hip hop (also hardcore rap) is a genre of hip hop music that developed through the East Coast hip hop scene in the 1980s. Pioneered by such artists as Run-DMC, Schoolly D, Boogie Down Productions and Public Enemy, it is generally ch ...

and gangsta rap

Gangsta rap or gangster rap, initially called reality rap, emerged in the mid- to late 1980s as a controversial hip-hop subgenre whose lyrics assert the culture and values typical of American street gangs and street hustlers. Many gangsta rappe ...

, as crack and hip hop became the two leading fundamentals of urban street culture.

''The Cosby Show

''The Cosby Show'' is an American television sitcom co-created by and starring Bill Cosby, which aired Thursday nights for eight seasons on NBC between September 20, 1984, until April 30, 1992. The show focuses on an upper middle-class Africa ...

'' begins as a TV series in 1984. Featuring an upper-middle-class family with comedian Bill Cosby as a physician and head of the family, it is regarded as one of the defining television shows of the decade.

11 members of the Black liberation and back-to-nature group MOVE died during a standoff with police in West Philadelphia

West Philadelphia, nicknamed West Philly, is a section of the city of Philadelphia. Alhough there are no officially defined boundaries, it is generally considered to reach from the western shore of the Schuylkill River, to City Avenue to the nort ...

on May 13, 1985. John Africa

John Africa (July 26, 1931 – May 13, 1985), born Vincent Leaphart, was the founder of MOVE, a Philadelphia-based, predominantly black organization active from the early 1970s and still active. He and his followers were killed at a residential ...

, the founder of MOVE was killed, as well as five other adults and five children. 65 homes were destroyed after a police helicopter dropped an incendiary device, causing an out of control fire in surrounding houses.

The film ''The Color Purple

''The Color Purple'' is a 1982 epistolary novel by American author Alice Walker which won the 1983 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and the National Book Award for Fiction.

'' was released to box office success in December 1985.The Color Purple. Box Office Mojo. Accessed Dec. 9, 2011. Set in the early 20th Century, ''The Color Purple'' tells the story of a young Black girl named Celie Harris who faces issues both public and socially hidden, including

domestic violence

Domestic violence (also known as domestic abuse or family violence) is violence or other abuse that occurs in a domestic setting, such as in a marriage or cohabitation. ''Domestic violence'' is often used as a synonym for '' intimate partn ...

, incest

Incest ( ) is human sexual activity between family members or close relatives. This typically includes sexual activity between people in consanguinity (blood relations), and sometimes those related by affinity ( marriage or stepfamily), ado ...

, pedophilia

Pedophilia ( alternatively spelt paedophilia) is a psychiatric disorder in which an adult or older adolescent experiences a primary or exclusive sexual attraction to prepubescent children. Although girls typically begin the process of puberty ...

, poverty

Poverty is the state of having few material possessions or little income. Poverty can have diverse

, racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagoni ...

, and sexism

Sexism is prejudice or discrimination based on one's sex or gender. Sexism can affect anyone, but it primarily affects women and girls.There is a clear and broad consensus among academic scholars in multiple fields that sexism refers pri ...

. ''The Color Purple'' has been described as "a plea for respect for Black women."

''Beloved

Beloved may refer to:

Books

* ''Beloved'' (novel), a 1987 novel by Toni Morrison

* ''The Beloved'' (Faulkner novel), a 2012 novel by Australian author Annah Faulkner

*''Beloved'', a 1993 historical romance about Zenobia, by Bertrice Small

Film ...

'' by Toni Morrison

Chloe Anthony Wofford Morrison (born Chloe Ardelia Wofford; February 18, 1931 – August 5, 2019), known as Toni Morrison, was an American novelist. Her first novel, '' The Bluest Eye'', was published in 1970. The critically acclaimed '' S ...

was published in 1987. In 2006, a ''New York Times'' survey of writers and literary critics ranked it as the best work of American fiction in the last 25 years. After producing additional masterworks, Toni Morrison was later awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

1988 saw the first major African-American gangsta rap

Gangsta rap or gangster rap, initially called reality rap, emerged in the mid- to late 1980s as a controversial hip-hop subgenre whose lyrics assert the culture and values typical of American street gangs and street hustlers. Many gangsta rappe ...

album - N.W.A

N.W.A (an abbreviation for Niggaz Wit Attitudes) was an American hip hop group whose members were among the earliest and most significant popularizers and controversial figures of the gangsta rap subgenre, and the group is widely considered ...

's ''Straight Outta Compton

''Straight Outta Compton'' is the debut studio album by rap group N.W.A, which, led by Eazy-E, formed in Los Angeles County's City of Compton in early 1987. Released by his label, Ruthless Records, on August 8, 1988, the album was produced ...

''. Gangsta rap would be recurrently accused of promoting anti-social behavior

Antisocial behavior is a behavior that is defined as the violation of the rights of others by committing crime, such as stealing and physical attack in addition to other behaviors such as lying and manipulation. It is considered to be disrupti ...

and broad criminality

In ordinary language, a crime is an unlawful act punishable by a state or other authority. The term ''crime'' does not, in modern criminal law, have any simple and universally accepted definition,Farmer, Lindsay: "Crime, definitions of", in Ca ...

, especially assault, homicide

Homicide occurs when a person kills another person. A homicide requires only a volitional act or omission that causes the death of another, and thus a homicide may result from accidental, reckless, or negligent acts even if there is no inten ...

and drug dealing, misogyny

Misogyny () is hatred of, contempt for, or prejudice against women. It is a form of sexism that is used to keep women at a lower social status than men, thus maintaining the societal roles of patriarchy. Misogyny has been widely practice ...

, promiscuity

Promiscuity is the practice of engaging in sexual activity frequently with different partners or being indiscriminate in the choice of sexual partners. The term can carry a moral judgment. A common example of behavior viewed as promiscuous by ma ...

and materialism

Materialism is a form of philosophical monism which holds matter to be the fundamental substance in nature, and all things, including mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. According to philosophical materialis ...

.

In 1988, track and field athlete Florence Griffith Joyner

Florence Delorez Griffith Joyner (born Florence Delorez Griffith; December 21, 1959 – September 21, 1998), also known as Flo-Jo, was an American track and field athlete. She set world records in 1988 for the 100 m and 200 m. During the late 1 ...

, also known as "Flo Jo", won three gold and one silver medal at the 1988 Summer Olympics

The 1988 Summer Olympics (), officially known as the Games of the XXIV Olympiad () and commonly known as Seoul 1988 ( ko, 서울 1988, Seoul Cheon gubaek palsip-pal), was an international multi-sport event held from 17 September to 2 October ...

. At the time, her medal haul was the second most for a female track and field athlete in history.

Ron Brown was elected chairman of the Democratic National Committee

The Democratic National Committee (DNC) is the governing body of the United States Democratic Party. The committee coordinates strategy to support Democratic Party candidates throughout the country for local, state, and national office, as well ...

in 1989, becoming the first African American to lead a major United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

political party

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular country's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific ideological or p ...

. Colin Powell

Colin Luther Powell ( ; April 5, 1937 – October 18, 2021) was an American politician, statesman, diplomat, and United States Army officer who served as the 65th United States Secretary of State from 2001 to 2005. He was the first Africa ...

was appointed as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is the body of the most senior uniformed leaders within the United States Department of Defense, that advises the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council and the ...

in 1989.

In 1989

File:1989 Events Collage.png, From left, clockwise: The Cypress Street Viaduct, Cypress structure collapses as a result of the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, killing motorists below; The proposal document for the World Wide Web is submitted; The Exxo ...

, Douglas Wilder

Lawrence Douglas Wilder (born January 17, 1931) is an American lawyer and politician who served as the 66th Governor of Virginia from 1990 to 1994. He was the first African American to serve as governor of a U.S. state since the Reconstructi ...

was elected as the first African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ensl ...

governor of Virginia

The governor of the Commonwealth of Virginia serves as the head of government of Virginia for a four-year term. The incumbent, Glenn Youngkin, was sworn in on January 15, 2022.

Oath of office

On inauguration day, the Governor-elect takes th ...

, and the first African-American elected governor of the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

.

Michael Jackson

Michael Joseph Jackson (August 29, 1958 – June 25, 2009) was an American singer, songwriter, dancer, and philanthropist. Dubbed the " King of Pop", he is regarded as one of the most significant cultural figures of the 20th century. Over ...

's 1982 album ''Thriller

Thriller may refer to:

* Thriller (genre), a broad genre of literature, film and television

** Thriller film, a film genre under the general thriller genre

Comics

* ''Thriller'' (DC Comics), a comic book series published 1983–84 by DC Comics i ...

'' became the best selling album of all time.

File:Florence Griffith Joyner2.jpg, Track and field star Florence Griffith Joyner

Florence Delorez Griffith Joyner (born Florence Delorez Griffith; December 21, 1959 – September 21, 1998), also known as Flo-Jo, was an American track and field athlete. She set world records in 1988 for the 100 m and 200 m. During the late 1 ...

won three gold and one silver medal at the 1988 Summer Olympics

The 1988 Summer Olympics (), officially known as the Games of the XXIV Olympiad () and commonly known as Seoul 1988 ( ko, 서울 1988, Seoul Cheon gubaek palsip-pal), was an international multi-sport event held from 17 September to 2 October ...

.

1990s

Clarence Thomas

Clarence Thomas (born June 23, 1948) is an American jurist who serves as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. He was nominated by President George H. W. Bush to succeed Thurgood Marshall and has served since 1 ...

was confirmed to the US Supreme Court in 1991.

In July 1991, serial killer and cannibal Jeffrey Dahmer

Jeffrey Lionel Dahmer (; May 21, 1960 – November 28, 1994), also known as the Milwaukee Cannibal or the Milwaukee Monster, was an American serial killer and sex offender who killed and dismemberment, dismembered seventeen men and boys ...

was arrested. Eleven of Dahmer's 17 victims were African-Americans.

The 1992 Los Angeles riots

The 1992 Los Angeles riots, sometimes called the 1992 Los Angeles uprising and the Los Angeles Race Riots, were a series of riots and civil disturbances that occurred in Los Angeles County, California, in April and May 1992. Unrest began in So ...

erupted after the officers accused of beating Rodney King in March 1991 were acquitted. In 1992 Mae Carol Jemison became the first African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ensl ...

woman to travel in space when she went into orbit aboard the Space Shuttle ''Endeavour''. Carol Moseley Braun (D-Illinois) became the first African-American woman to be elected to the United States Senate on November 3, 1992.

Director Spike Lee

Shelton Jackson "Spike" Lee (born March 20, 1957) is an American film director, producer, screenwriter, and actor. His production company, 40 Acres and a Mule Filmworks, has produced more than 35 films since 1983. He made his directorial debut ...

's film ''Malcolm X

Malcolm X (born Malcolm Little, later Malik el-Shabazz; May 19, 1925 – February 21, 1965) was an American Muslim minister and human rights activist who was a prominent figure during the civil rights movement. A spokesman for the Nation of I ...

'' was released in 1992, a serious biography of the leader of the Nation of Islam

The Nation of Islam (NOI) is a religious and political organization founded in the United States by Wallace Fard Muhammad in 1930.

A black nationalist organization, the NOI focuses its attention on the African diaspora, especially on African ...

.

In 1993, civil rights activist C. Delores Tucker

Cynthia Delores Tucker (née Nottage; October 4, 1927 – October 12, 2005) was an American politician and civil rights activist. She had a long history of involvement in the American Civil Rights Movement. From the 1990s onward, she engaged in a ...

started publicly campaigning against misogyny in rap music. Tucker believed that the attacks upon Black women in hip-hop lyrics threatened the moral foundation of African American society. In response, Delores Tucker was lyrically disparaged by multiple rappers, including Tupac, and Eminem

Marshall Bruce Mathers III (born October 17, 1972), known professionally as Eminem (; often stylized as EMINƎM), is an American rapper and record producer. He is credited with popularizing Hip hop music, hip hop in Middle America (United Sta ...

.

Cornel West's text, ''Race Matters

''Race Matters'' is a social sciences book by Cornel West. The book was first published on April 1, 1993, by Beacon Press. The book analyzes moral authority and racial debates concerning skin color in the United States. The book questions matters ...

,'' was published in 1994.

The Million Man March was held on October 16, 1995, in Washington, D.C., co-initiated by Louis Farrakhan

Louis Farrakhan (; born Louis Eugene Walcott, May 11, 1933) is an American religious leader, Black supremacy, black supremacist, Racism, anti-white and Antisemitism, antisemitic Conspiracy theory, conspiracy theorist, and former singer who hea ...

and James Bevel. The Million Woman March

The Million Woman March was a protest march organized on October 25, 1997 involving approximately half a million people in Benjamin Franklin Parkway,Philadelphia and Pennsylvania. A major theme of the march was family unity and what it means to ...

was held on October 25, 1997, in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

.

The racially charged murder trial of O.J. Simpson transfixed America between January and October 1995. The trial of the already famous NFL star and actor O. J. Simpson was the most publicized in US history.

Michael Jordan

Michael Jeffrey Jordan (born February 17, 1963), also known by his initials MJ, is an American businessman and former professional basketball player. His biography on the official NBA website states: "By acclamation, Michael Jordan is the g ...

was the most dominant basketball player of the 1990s, becoming a global cultural icon

A cultural icon is a person or an artifact that is identified by members of a culture as representative of that culture. The process of identification is subjective, and "icons" are judged by the extent to which they can be seen as an authentic ...

.

2000s

Colin Powell

Colin Luther Powell ( ; April 5, 1937 – October 18, 2021) was an American politician, statesman, diplomat, and United States Army officer who served as the 65th United States Secretary of State from 2001 to 2005. He was the first Africa ...

was appointed as the first African American to be Secretary of State on January 20, 2001. Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

in '' Grutter v. Bollinger'' upheld the University of Michigan Law School

The University of Michigan Law School (Michigan Law) is the law school of the University of Michigan, a public research university in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Founded in 1859, the school offers Master of Laws (LLM), Master of Comparative Law (MCL ...

's admission policy on June 23, 2003. However, in the simultaneously heard ''Gratz v. Bollinger

''Gratz v. Bollinger'', 539 U.S. 244 (2003), was a United States Supreme Court case regarding the University of Michigan undergraduate affirmative action admissions policy. In a 6–3 decision announced on June 23, 2003, Chief Justice Rehnq ...

,'' the university is required to change a policy.

In 2004, the founder of the New York based Nuwaubian Nation

The Nuwaubian Nation, Nuwaubian movement, or United Nuwaubian Nation () is an American new religious movement founded and led by Dwight York, also known as Malachi Z. York. York began founding several black Muslim groups in New York in 1967. H ...

, Dwight York, was sentenced to 135 years for child molestation and racketeering.

The Millions More Movement held a march in Washington D.C on October 15, 2005. Rosa Parks died at the age of 92 on October 25, 2005. Rosa Parks was a noted civil rights activist who had helped initiate the Montgomery bus boycott

The Montgomery bus boycott was a political and social protest campaign against the policy of racial segregation on the public transit system of Montgomery, Alabama. It was a foundational event in the civil rights movement in the United States ...

in 1955. As an honor, her body lay in state in the Capitol Rotunda

The United States Capitol rotunda is the tall central rotunda of the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C. It has been described as the Capitol's "symbolic and physical heart". Built between 1818 and 1824, the rotunda is located below the ...

in Washington, D.C. before her funeral.

In March 2007, the Cherokee Nation

The Cherokee Nation ( Cherokee: ᏣᎳᎩᎯ ᎠᏰᎵ ''Tsalagihi Ayeli'' or ᏣᎳᎩᏰᎵ ''Tsalagiyehli''), also known as the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, is the largest of three Cherokee federally recognized tribes in the United States. ...

voted to expel African American descendants of slaves held by the Cherokee from the Cherokee tribe. This ruling ignited a 10-year legal battle, with the Black Cherokee freedmen regaining their legal status within the Cherokee Nation in 2017.

On June 28, 2007, the US Supreme Court in ''Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1

''Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1'', 551 U.S. 701 (2007), also known as the ''PICS case'', is a United States Supreme Court case which found it unconstitutional for a school district to use race as a factor ...

,'' decided along with '' Meredith v. Jefferson County Board of Education,'' ruled that school districts could not assign students to particular public schools solely for the purpose of achieving racial integration; it declined to recognize racial balancing as a compelling state interest.

On June 3, 2008, Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, Obama was the first Af ...

received enough delegates by the end of state primaries to be the presumptive Democratic Party of the United States nominee. On August 28, 2008, at the 2008 Democratic National Convention, in a stadium filled with supporters, Obama accepted the Democratic nomination for President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal gove ...

. Obama was elected 44th President of the United States of America on November 4, 2008, opening his victory speech with, "If there is anyone out there who still doubts that America is a place where all things are possible; who still wonders if the dream of our founders is alive in our time; who still questions the power of our democracy, tonight is your answer."

On January 20, 2009, Obama was sworn in as the 44th President of the United States, the first African American to become president. Former Maryland Lt. Governor Michael Steele, an African American, was elected as Chairman of the Republican National Committee

The Republican National Committee (RNC) is a U.S. political committee that assists the Republican Party of the United States. It is responsible for developing and promoting the Republican brand and political platform, as well as assisting in ...

on January 30, 2009.

The U.S. Postal Service issued a commemorative six-stamp set portraying twelve civil rights pioneers in 2010. Obama was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Chemistry, Physics, Physiolo ...

on October 9, 2009.

2010s

On July 19, 2010, Shirley Sherrod was pressured to resign from the U.S. Department of Agriculture because of controversial publicity; the department apologized to her for her being inaccurately portrayed as racist toward white Americans. In 2013, protests were held across the United States following the death of an unarmed African-American teenager, Trayvon Martin, who was shot by George Zimmerman in Florida. Zimmerman was charged with murder, but later acquitted. In reaction to Martin's death and Zimmerman's acquittal, Black activistsAlicia Garza

Alicia Garza (born January 4, 1981) is an American civil rights activist and writer known for co-founding the international Black Lives Matter movement. She has organized around the issues of health, student services and rights, rights for d ...

, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi

Opal is a hydrated amorphous form of silica (SiO2·''n''H2O); its water content may range from 3 to 21% by weight, but is usually between 6 and 10%. Due to its amorphous property, it is classified as a mineraloid, unlike crystalline forms of ...

popularized the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter.

In 2014, massive protests were held in Ferguson, Missouri, following the shooting death of Michael Brown, Jr. by Ferguson police. The death of Eric Garner while being held in a chokehold by a New York City policeman, Daniel Pantaleo, in July 2014, sparked additional outrage and protests across the country. In the wake of these deaths, and others, Black Lives Matter

Black Lives Matter (abbreviated BLM) is a decentralized political and social movement that seeks to highlight racism, discrimination, and racial inequality experienced by black people. Its primary concerns are incidents of police bruta ...

developed into a nationwide non-violent movement.

Nine Black churchgoers were murdered in the racially motivated Charleston church shooting

On June 17, 2015, a mass shooting occurred in Charleston, South Carolina, in which nine African Americans were killed during a Bible study at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church. Among those people who were killed was the senior past ...

on June 17, 2015.

From 2019, the American Descendants of Slavery

American Descendants of Slavery (ADOS) is a term referring to descendants of enslaved Africans in the area that would become the United States (from its colonial period onward), and to the political movement of the same name. Both the concept an ...

(ADOS) political movement began to differentiate themselves from the growing number of Black African immigrants in the United States and Black immigrants in the US from the Caribbean.

2020s

In later May 2020, a video was posted onFacebook

Facebook is an online social media and social networking service owned by American company Meta Platforms. Founded in 2004 by Mark Zuckerberg with fellow Harvard College students and roommates Eduardo Saverin, Andrew McCollum, Dust ...

and Instagram

Instagram is a photo and video sharing social networking service owned by American company Meta Platforms. The app allows users to upload media that can be edited with filters and organized by hashtags and geographical tagging. Posts can ...

showing George Floyd

George Perry Floyd Jr. (October 14, 1973 – May 25, 2020) was an African-American man who was murdered by a police officer in Minneapolis, Minnesota, during an arrest made after a store clerk suspected Floyd may have used a counterfeit tw ...

being murdered by a Minneapolis Police Department

The Minneapolis Police Department (MPD) is the primary law enforcement agency in Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States. It is also the largest police department in Minnesota. Formed in 1867, it is the second-oldest police department in Minnesot ...

officer, Derek Chauvin

Derek Michael Chauvin ( ; born March 19, 1976) is an American former police officer who was convicted for the murder of George Floyd, a 46-year-old African-American man, in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Chauvin was a member of the Minneapolis Police ...

, who knelt on Floyd's neck for over ten minutes. Floyd's murder sparked outrage and condemnation across the country and the globe. Despite restrictions on public gatherings of large sizes due to the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic, also known as the coronavirus pandemic, is an ongoing global pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The novel virus was first identi ...

, large protests were held in cities across the United States as well as in many other nations.

On August 28, 2020, thousands of people gathered at the Lincoln Memorial

The Lincoln Memorial is a U.S. national memorial built to honor the 16th president of the United States, Abraham Lincoln. It is on the western end of the National Mall in Washington, D.C., across from the Washington Monument, and is in ...

in Washington, D.C. for the Commitment March, organized by Rev. Al Sharpton and joined by Martin Luther King III, in support of black civil rights.

The Portland foreclosure protest

The Red House eviction defense was an Occupation (protest), occupation protest at a foreclosed house on North Mississippi Avenue in the Humboldt, Portland, Oregon, Humboldt neighborhood in the Albina, Portland, Oregon, Albina district, a histori ...

was a response to the eviction of an Afro-indigenous family in Portland, Oregon

Portland (, ) is a port city in the Pacific Northwest and the largest city in the U.S. state of Oregon. Situated at the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers, Portland is the county seat of Multnomah County, the most populous ...

.

Across 2020 the COVID-19 pandemic had a disproportionately negative impact upon Black America. Black Americans died from the virus at a higher rate than the general population. Black America also suffered significant economic hardship due to the virus.

On November 3, 2020, Kamala Harris

Kamala Devi Harris ( ; born October 20, 1964) is an American politician and attorney who is the 49th vice president of the United States. She is the first female vice president and the highest-ranking female official in U.S. history, as well ...

was elected the first black Vice President of the United States

The vice president of the United States (VPOTUS) is the second-highest officer in the executive branch of the U.S. federal government, after the president of the United States, and ranks first in the presidential line of succession. The vice p ...

.

Political representation

In 1989,Douglas Wilder

Lawrence Douglas Wilder (born January 17, 1931) is an American lawyer and politician who served as the 66th Governor of Virginia from 1990 to 1994. He was the first African American to serve as governor of a U.S. state since the Reconstructi ...

became the first African American to be elected governor in U.S. history. In 1992 Carol Moseley-Braun of Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rock ...

became the first black woman to be elected to the U.S. Senate. In 2000 there were 8,936 black officeholders in the United States, showing a net increase of 7,467 since 1970. In 2001 there were 484 black mayors.

The 38 African-American members of Congress formed the Congressional Black Caucus

The Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) is a caucus made up of most African-American members of the United States Congress. Representative Karen Bass from California chaired the caucus from 2019 to 2021; she was succeeded by Representative Joyce B ...

, which serves as a political bloc for issues relating to African Americans. The appointment of blacks to high federal offices—including General Colin Powell

Colin Luther Powell ( ; April 5, 1937 – October 18, 2021) was an American politician, statesman, diplomat, and United States Army officer who served as the 65th United States Secretary of State from 2001 to 2005. He was the first Africa ...

, Chairman of the U.S. Armed Forces Joint Chiefs of Staff, 1989–1993, United States Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State. The office holder is one of the highest ranking members of the president's Ca ...

, 2001–2005; Condoleezza Rice

Condoleezza Rice ( ; born November 14, 1954) is an American diplomat and political scientist who is the current director of the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. A member of the Republican Party, she previously served as the 66th Un ...

, Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs, 2001–2004, Secretary of State in, 2005–2009; Ron Brown, United States Secretary of Commerce

The United States secretary of commerce (SecCom) is the head of the United States Department of Commerce. The secretary serves as the principal advisor to the president of the United States on all matters relating to commerce. The secretary rep ...

, 1993–1996, Eric Holder, Attorney General of the United States

The United States attorney general (AG) is the head of the United States Department of Justice, and is the chief law enforcement officer of the federal government of the United States. The attorney general serves as the principal advisor to the ...

, 2009–present; and Supreme Court justices Thurgood Marshall

Thurgood Marshall (July 2, 1908 – January 24, 1993) was an American civil rights lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1967 until 1991. He was the Supreme Court's first African-A ...

and Clarence Thomas

Clarence Thomas (born June 23, 1948) is an American jurist who serves as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. He was nominated by President George H. W. Bush to succeed Thurgood Marshall and has served since 1 ...

—also demonstrates the increasing contributions of blacks in the political arena.

In 2009 Michael S. Steele

Michael Stephen Steele (born October 19, 1958) is an American political commentator, attorney, and Republican Party politician. Steele served as the seventh lieutenant governor of Maryland from 2003 to 2007; he was the first African-American ...

was elected as the first African-American chairman of the national Republican Party

The National Republican Party, also known as the Anti-Jacksonian Party or simply Republicans, was a political party in the United States that evolved from a conservative-leaning faction of the Democratic-Republican Party that supported John ...

.

In 2021 Ebenezer Baptist Church pastor Raphael Warnock became the first African American Democratic Senator from a former Confederate state. 2008 presidential election of Barack Obama

In 2008 presidential elections, Illinois senator

In 2008 presidential elections, Illinois senator Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, Obama was the first Af ...

became the first black presidential nominee of the Democratic Party, the first Black presidential candidate from a major political party. He was elected as the 44th President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal gove ...

on November 4, 2008, and inaugurated on January 20, 2009.

At least 95 percent of African-American voters voted for Obama. Obama won big among young and minority voters, bringing a number of new states to the Democratic electoral column. Obama became the first Democrat since Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he previously served as th ...

to win a popular vote majority. He also received overwhelming support from whites, a majority of Asians, and Americans of Hispanic origin. Obama lost the overall white vote, but he won a larger proportion of white votes than any previous non-incumbent Democratic presidential candidate since Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he previously served as th ...

.

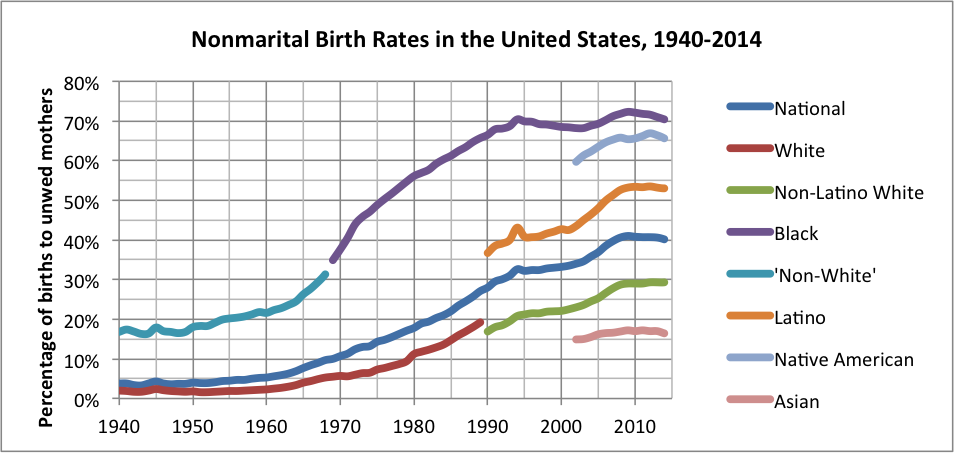

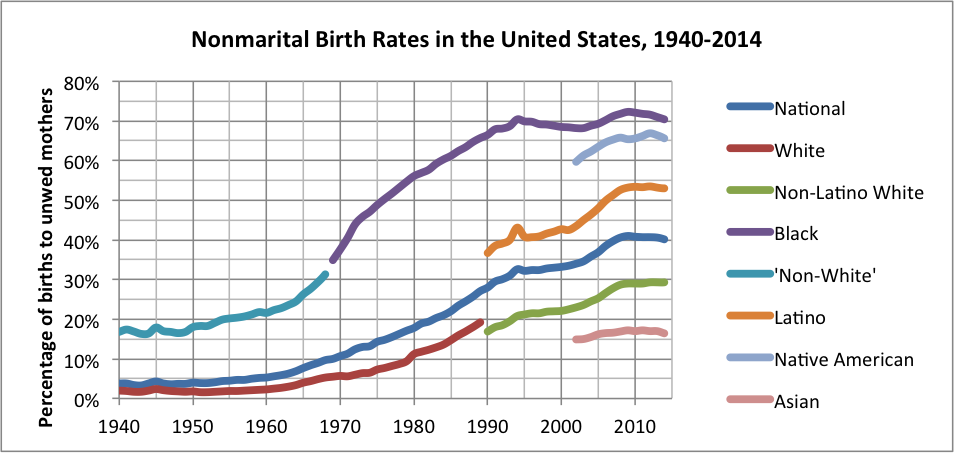

Interracial marriages

Marriages between African-Americans and people of other races have significantly increased since all race-based legal restrictions on interracial marriage ended following '' Loving v. Virginia'' in 1967. The overall rate of African-Americans marrying non-Black spouses more than tripled between 1980 and 2015, from 5% to 18%.Pew Research Intermarriage in the U.S. 50 Years After Loving v. VirginiaMay 18, 2017 24% of all Black male newlyweds in 2015 married outside their race, compared with 12% of Black female newlyweds.

Economic situation

Nearly 25% of black Americans in the early 21st century live below thepoverty line

The poverty threshold, poverty limit, poverty line or breadline is the minimum level of income deemed adequate in a particular country. The poverty line is usually calculated by estimating the total cost of one year's worth of necessities for ...

, approximately the same percentage as in 1968. The child poverty rate has also increased among African Americans and their unemployment is disproportionately high in comparison to other ethnic groups.

These sobering facts have been masked in the public opinion by the sometimes spectacular achievements of successful individuals. African Americans are underrepresented in the rapidly expanding and lucrative fields related to computer programming and technology, where innovations have led to some people making huge new fortunes.

Economic progress for blacks' reaching the extremes of wealth has been slow. According to ''Forbes

''Forbes'' () is an American business magazine owned by Integrated Whale Media Investments and the Forbes family. Published eight times a year, it features articles on finance, industry, investing, and marketing topics. ''Forbes'' also r ...

'' "richest" lists, Oprah Winfrey

Oprah Gail Winfrey (; born Orpah Gail Winfrey; January 29, 1954), or simply Oprah, is an American talk show host, television producer, actress, author, and philanthropist. She is best known for her talk show, ''The Oprah Winfrey Show'', b ...

was the richest African American of the 20th century and has been the world's only black billionaire in 2004, 2005, and 2006. Not only was Winfrey the world's only black billionaire but she has been the only black on the Forbes 400 list nearly every year since 1995. BET

Black Entertainment Television (acronym BET) is an American basic cable channel targeting African-American audiences. It is owned by the CBS Entertainment Group unit of Paramount Global via BET Networks and has offices in New York City, Los ...

founder Bob Johnson briefly joined her on the list from 2001 to 2003 before his ex-wife acquired part of his fortune; although he returned to the list in 2006, he did not make it in 2007. Blacks currently comprise 0.25% of America's economic elite; they make up 13% of the total U.S. population.

Social issues

Despite the gains of the

Despite the gains of the civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the Unite ...

, other factors have resulted in African-American communities suffering from extremely high incarceration rates of their young males. Contributing factors have been the drug war waged by successive administrations, imposition of sentencing guidelines at the federal and state levels, cutbacks in government assistance, restructuring of industry since the mid-20th century and extensive loss of working-class jobs leading to high poverty rates, and government neglect, an erosion of African American two parent families, and unfavorable social policies. African Americans have the highest imprisonment rate of any major ethnic group in the United States and the world, and are sentenced to death at a rate higher than any other ethnic group.

The southern states of the former Confederacy, which historically had maintained slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

longer than in the remainder of the country and imposed post-Reconstruction oppression, have the highest rates of incarceration and application of the death penalty

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that ...

., Pew Research Center, released March 2, 2009

See also

* Timeline of African-American history *Timeline of the civil rights movement

This is a timeline of the civil rights movement in the United States, a nonviolent mid-20th century freedom movement to gain legal equality and the enforcement of constitutional rights for people of color. The goals of the movement included sec ...

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Post-Civil Rights era in African-American history