Physics on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Physics is the natural science that studies

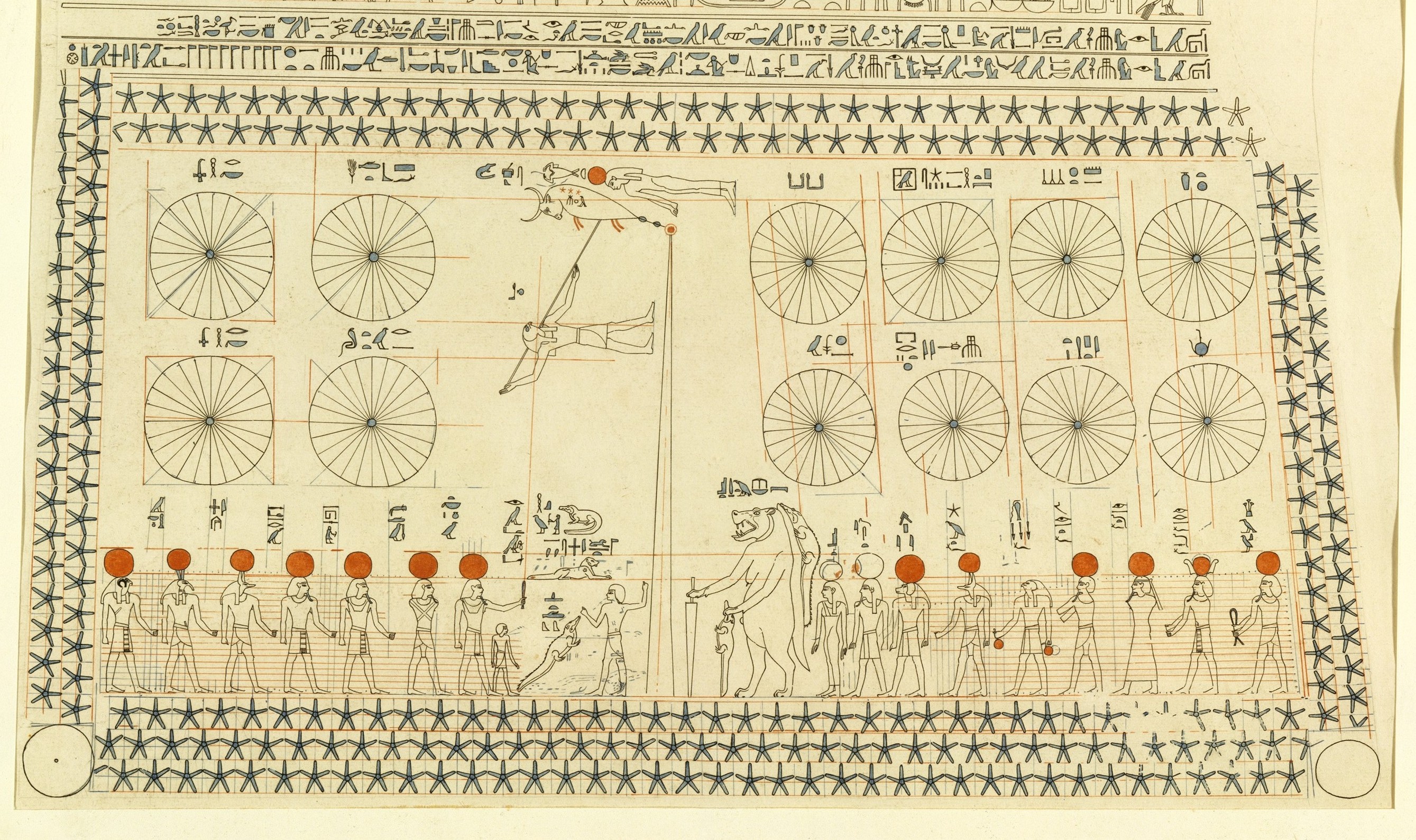

Astronomy is one of the oldest natural sciences. Early civilizations dating back before 3000 BCE, such as the Sumerians, ancient Egyptians, and the Indus Valley Civilisation, had a predictive knowledge and a basic awareness of the motions of the Sun, Moon, and stars. The stars and planets, believed to represent gods, were often worshipped. While the explanations for the observed positions of the stars were often unscientific and lacking in evidence, these early observations laid the foundation for later astronomy, as the stars were found to traverse great circles across the sky, which could not explain the positions of the planets.

According to Asger Aaboe, the origins of

Astronomy is one of the oldest natural sciences. Early civilizations dating back before 3000 BCE, such as the Sumerians, ancient Egyptians, and the Indus Valley Civilisation, had a predictive knowledge and a basic awareness of the motions of the Sun, Moon, and stars. The stars and planets, believed to represent gods, were often worshipped. While the explanations for the observed positions of the stars were often unscientific and lacking in evidence, these early observations laid the foundation for later astronomy, as the stars were found to traverse great circles across the sky, which could not explain the positions of the planets.

According to Asger Aaboe, the origins of

In sixth-century Europe

In sixth-century Europe

had its own natural place

Meaning that because of the density of these elements, they will revert back to their own specific place in the atmosphere. So, because of their weights, fire would be at the very top, air right underneath fire, then water, then lastly earth. He also stated that when a small amount of one element enters the natural place of another, the less abundant element will automatically go into its own natural place. For example, if there is a fire on the ground, if you pay attention, the flames go straight up into the air as an attempt to go back into its natural place where it belongs. Aristotle called his metaphysics “first philosophy” and characterized it as the study of “being as being”. Aristotle defined the paradigm of motion as a being or entity encompassing different areas in the same body. Meaning that if a person is at a certain location (A) they can move to a new location (B) and still take up the same amount of space. This is involved with Aristotle’s belief that motion is a continuum. In terms of matter, Aristotle believed that the change in category (ex. place) and quality (ex. color) of an object is defined as “alteration”. But, a change in substance is a change in matter. This is also very close to our idea of matter today. He also devised his own laws of motion that include 1) heavier objects will fall faster, the speed being proportional to the weight and 2) the speed of the object that is falling depends inversely on the density object it is falling through (ex. density of air). He also stated that, when it comes to violent motion (motion of an object when a force is applied to it by a second object) that the speed that object moves, will only be as fast or strong as the measure of force applied to it. This is also seen in the rules of velocity and force that is taught in physics classes today. These rules are not necessarily what we see in our physics today but, they are very similar. It is evident that these rules were the backbone for other scientists to come revise and edit his beliefs. The most notable innovations were in the field of optics and vision, which came from the works of many scientists like Ibn Sahl,

The most notable innovations were in the field of optics and vision, which came from the works of many scientists like Ibn Sahl,

Physics became a separate science when early modern Europeans used experimental and quantitative methods to discover what are now considered to be the laws of physics.

Major developments in this period include the replacement of the geocentric model of the Solar System with the heliocentric Copernican model, the laws governing the motion of planetary bodies (determined by Kepler between 1609 and 1619), Galileo's pioneering work on telescopes and observational astronomy in the 16th and 17th Centuries, and Isaac Newton's discovery and unification of the laws of motion and universal gravitation (that would come to bear his name). Newton also developed calculus, the mathematical study of continuous change, which provided new mathematical methods for solving physical problems.

The discovery of new laws in thermodynamics, chemistry, and

Physics became a separate science when early modern Europeans used experimental and quantitative methods to discover what are now considered to be the laws of physics.

Major developments in this period include the replacement of the geocentric model of the Solar System with the heliocentric Copernican model, the laws governing the motion of planetary bodies (determined by Kepler between 1609 and 1619), Galileo's pioneering work on telescopes and observational astronomy in the 16th and 17th Centuries, and Isaac Newton's discovery and unification of the laws of motion and universal gravitation (that would come to bear his name). Newton also developed calculus, the mathematical study of continuous change, which provided new mathematical methods for solving physical problems.

The discovery of new laws in thermodynamics, chemistry, and

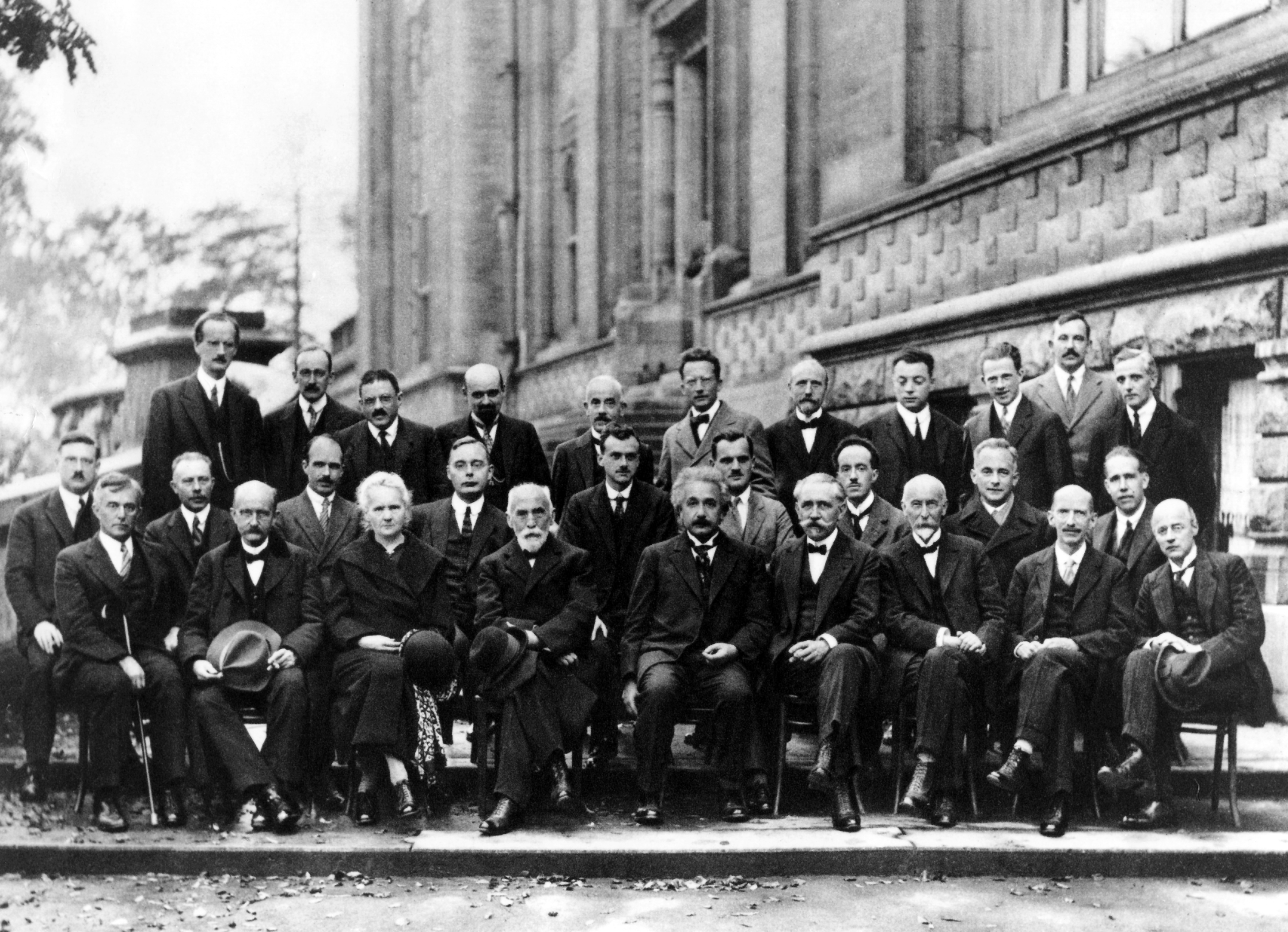

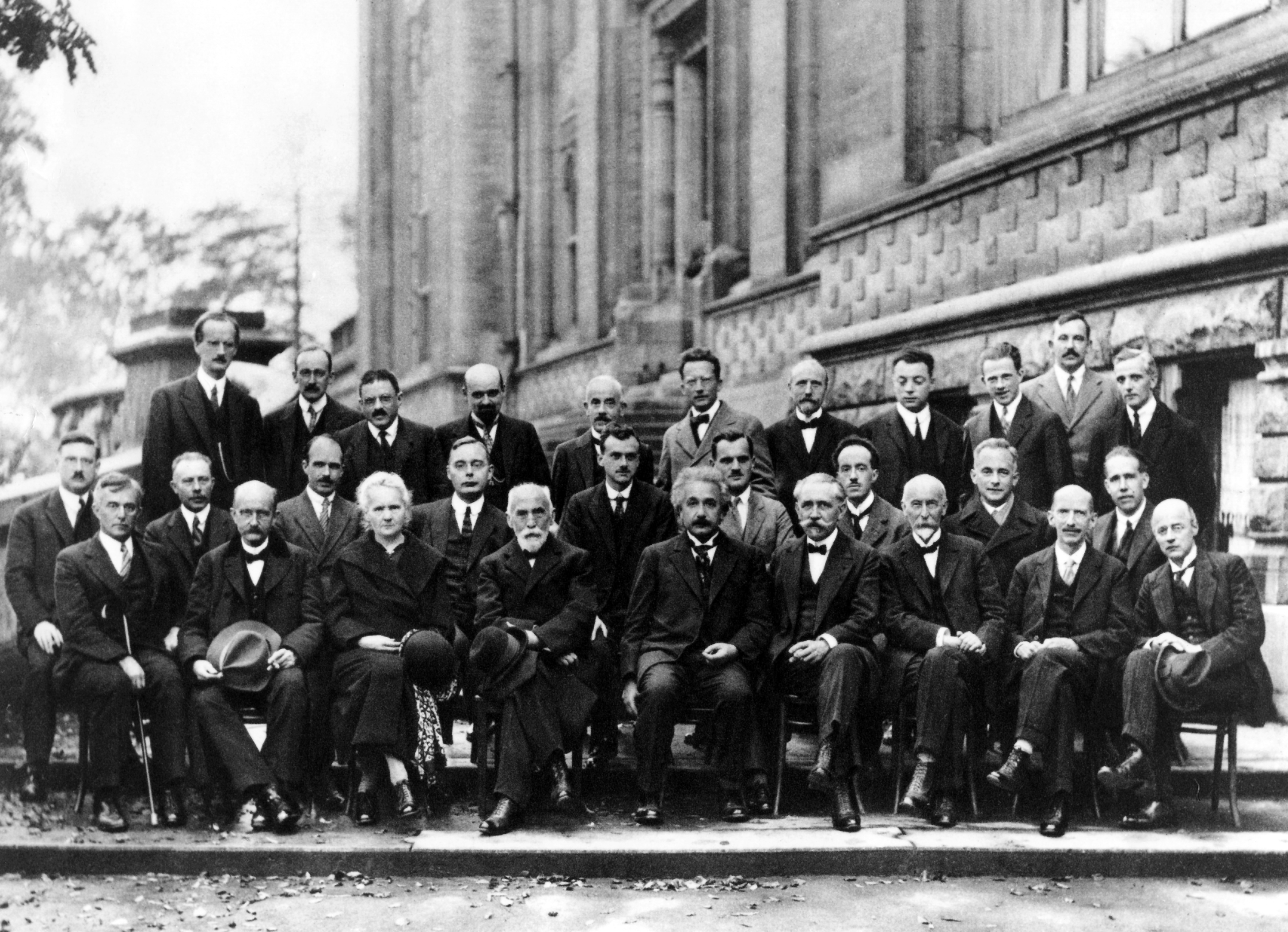

Modern physics began in the early 20th century with the work of

Modern physics began in the early 20th century with the work of

While physics aims to discover universal laws, its theories lie in explicit domains of applicability.

While physics aims to discover universal laws, its theories lie in explicit domains of applicability.

Loosely speaking, the laws of classical physics accurately describe systems whose important length scales are greater than the atomic scale and whose motions are much slower than the speed of light. Outside of this domain, observations do not match predictions provided by classical mechanics. Einstein contributed the framework of special relativity, which replaced notions of absolute time and space with spacetime and allowed an accurate description of systems whose components have speeds approaching the speed of light. Planck, Schrödinger, and others introduced quantum mechanics, a probabilistic notion of particles and interactions that allowed an accurate description of atomic and subatomic scales. Later, quantum field theory unified quantum mechanics and special relativity. General relativity allowed for a dynamical, curved spacetime, with which highly massive systems and the large-scale structure of the universe can be well-described. General relativity has not yet been unified with the other fundamental descriptions; several candidate theories of quantum gravity are being developed.

Loosely speaking, the laws of classical physics accurately describe systems whose important length scales are greater than the atomic scale and whose motions are much slower than the speed of light. Outside of this domain, observations do not match predictions provided by classical mechanics. Einstein contributed the framework of special relativity, which replaced notions of absolute time and space with spacetime and allowed an accurate description of systems whose components have speeds approaching the speed of light. Planck, Schrödinger, and others introduced quantum mechanics, a probabilistic notion of particles and interactions that allowed an accurate description of atomic and subatomic scales. Later, quantum field theory unified quantum mechanics and special relativity. General relativity allowed for a dynamical, curved spacetime, with which highly massive systems and the large-scale structure of the universe can be well-described. General relativity has not yet been unified with the other fundamental descriptions; several candidate theories of quantum gravity are being developed.

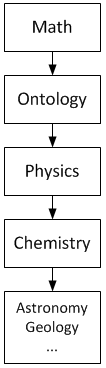

Ontology is a prerequisite for physics, but not for mathematics. It means physics is ultimately concerned with descriptions of the real world, while mathematics is concerned with abstract patterns, even beyond the real world. Thus physics statements are synthetic, while mathematical statements are analytic. Mathematics contains hypotheses, while physics contains theories. Mathematics statements have to be only logically true, while predictions of physics statements must match observed and experimental data.

The distinction is clear-cut, but not always obvious. For example, mathematical physics is the application of mathematics in physics. Its methods are mathematical, but its subject is physical. The problems in this field start with a "Boundary condition, mathematical model of a physical situation" (system) and a "mathematical description of a physical law" that will be applied to that system. Every mathematical statement used for solving has a hard-to-find physical meaning. The final mathematical solution has an easier-to-find meaning, because it is what the solver is looking for.

Pure physics is a branch of fundamental science (also called basic science). Physics is also called "''the'' fundamental science" because all branches of natural science like chemistry, astronomy, geology, and biology are constrained by laws of physics.The Feynman Lectures on Physics Vol. I Ch. 3: The Relation of Physics to Other Sciences

Ontology is a prerequisite for physics, but not for mathematics. It means physics is ultimately concerned with descriptions of the real world, while mathematics is concerned with abstract patterns, even beyond the real world. Thus physics statements are synthetic, while mathematical statements are analytic. Mathematics contains hypotheses, while physics contains theories. Mathematics statements have to be only logically true, while predictions of physics statements must match observed and experimental data.

The distinction is clear-cut, but not always obvious. For example, mathematical physics is the application of mathematics in physics. Its methods are mathematical, but its subject is physical. The problems in this field start with a "Boundary condition, mathematical model of a physical situation" (system) and a "mathematical description of a physical law" that will be applied to that system. Every mathematical statement used for solving has a hard-to-find physical meaning. The final mathematical solution has an easier-to-find meaning, because it is what the solver is looking for.

Pure physics is a branch of fundamental science (also called basic science). Physics is also called "''the'' fundamental science" because all branches of natural science like chemistry, astronomy, geology, and biology are constrained by laws of physics.The Feynman Lectures on Physics Vol. I Ch. 3: The Relation of Physics to Other Sciences

see also reductionism and special sciences Similarly, chemistry is often called the central science because of its role in linking the physical sciences. For example, chemistry studies properties, structures, and chemical reaction, reactions of matter (chemistry's focus on the molecular and atomic scale Difference between chemistry and physics, distinguishes it from physics). Structures are formed because particles exert electrical forces on each other, properties include physical characteristics of given substances, and reactions are bound by laws of physics, like conservation of energy, Conservation of mass, mass, and charge conservation, charge. Physics is applied in industries like engineering and medicine.

Applied physics is a general term for physics research, which is intended for a particular use. An applied physics curriculum usually contains a few classes in an applied discipline, like geology or electrical engineering. It usually differs from engineering in that an applied physicist may not be designing something in particular, but rather is using physics or conducting physics research with the aim of developing new technologies or solving a problem.

The approach is similar to that of applied mathematics. Applied physicists use physics in scientific research. For instance, people working on accelerator physics might seek to build better particle detectors for research in theoretical physics.

Physics is used heavily in engineering. For example, statics, a subfield of mechanics, is used in the building of bridges and other static structures. The understanding and use of acoustics results in sound control and better concert halls; similarly, the use of optics creates better optical devices. An understanding of physics makes for more realistic flight simulators, video games, and movies, and is often critical in forensic investigations.

With the Uniformitarianism (science), standard consensus that the Scientific law, laws of physics are universal and do not change with time, physics can be used to study things that would ordinarily be mired in uncertainty. For example, in the History of Earth#Origin of the Earth's core and first atmosphere, study of the origin of the earth, one can reasonably model earth's mass, temperature, and rate of rotation, as a function of time allowing one to extrapolate forward or backward in time and so predict future or prior events. It also allows for simulations in engineering that drastically speed up the development of a new technology.

But there is also considerable interdisciplinarity, so many other important fields are influenced by physics (e.g., the fields of econophysics and sociophysics).

Applied physics is a general term for physics research, which is intended for a particular use. An applied physics curriculum usually contains a few classes in an applied discipline, like geology or electrical engineering. It usually differs from engineering in that an applied physicist may not be designing something in particular, but rather is using physics or conducting physics research with the aim of developing new technologies or solving a problem.

The approach is similar to that of applied mathematics. Applied physicists use physics in scientific research. For instance, people working on accelerator physics might seek to build better particle detectors for research in theoretical physics.

Physics is used heavily in engineering. For example, statics, a subfield of mechanics, is used in the building of bridges and other static structures. The understanding and use of acoustics results in sound control and better concert halls; similarly, the use of optics creates better optical devices. An understanding of physics makes for more realistic flight simulators, video games, and movies, and is often critical in forensic investigations.

With the Uniformitarianism (science), standard consensus that the Scientific law, laws of physics are universal and do not change with time, physics can be used to study things that would ordinarily be mired in uncertainty. For example, in the History of Earth#Origin of the Earth's core and first atmosphere, study of the origin of the earth, one can reasonably model earth's mass, temperature, and rate of rotation, as a function of time allowing one to extrapolate forward or backward in time and so predict future or prior events. It also allows for simulations in engineering that drastically speed up the development of a new technology.

But there is also considerable interdisciplinarity, so many other important fields are influenced by physics (e.g., the fields of econophysics and sociophysics).

Theorists seek to develop mathematical models that both agree with existing experiments and successfully predict future experimental results, while Experimentalism, experimentalists devise and perform experiments to test theoretical predictions and explore new phenomena. Although theory and experiment are developed separately, they strongly affect and depend upon each other. Progress in physics frequently comes about when experimental results defy explanation by existing theories, prompting intense focus on applicable modelling, and when new theories generate experimentally testable predictions, which inspire the development of new experiments (and often related equipment).

Physicists who work at the interplay of theory and experiment are called Phenomenology (particle physics), phenomenologists, who study complex phenomena observed in experiment and work to relate them to a Theory of everything, fundamental theory.

Theoretical physics has historically taken inspiration from philosophy; electromagnetism was unified this way. Beyond the known universe, the field of theoretical physics also deals with hypothetical issues, such as Many-worlds interpretation, parallel universes, a multiverse, and higher dimensions. Theorists invoke these ideas in hopes of solving particular problems with existing theories; they then explore the consequences of these ideas and work toward making testable predictions.

Experimental physics expands, and is expanded by, engineering and technology. Experimental physicists who are involved in basic research design and perform experiments with equipment such as particle accelerators and lasers, whereas those involved in applied research often work in industry, developing technologies such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and transistors. Richard Feynman, Feynman has noted that experimentalists may seek areas that have not been explored well by theorists. "In fact experimenters have a certain individual character. They ... very often do their experiments in a region in which people know the theorist has not made any guesses."

Theorists seek to develop mathematical models that both agree with existing experiments and successfully predict future experimental results, while Experimentalism, experimentalists devise and perform experiments to test theoretical predictions and explore new phenomena. Although theory and experiment are developed separately, they strongly affect and depend upon each other. Progress in physics frequently comes about when experimental results defy explanation by existing theories, prompting intense focus on applicable modelling, and when new theories generate experimentally testable predictions, which inspire the development of new experiments (and often related equipment).

Physicists who work at the interplay of theory and experiment are called Phenomenology (particle physics), phenomenologists, who study complex phenomena observed in experiment and work to relate them to a Theory of everything, fundamental theory.

Theoretical physics has historically taken inspiration from philosophy; electromagnetism was unified this way. Beyond the known universe, the field of theoretical physics also deals with hypothetical issues, such as Many-worlds interpretation, parallel universes, a multiverse, and higher dimensions. Theorists invoke these ideas in hopes of solving particular problems with existing theories; they then explore the consequences of these ideas and work toward making testable predictions.

Experimental physics expands, and is expanded by, engineering and technology. Experimental physicists who are involved in basic research design and perform experiments with equipment such as particle accelerators and lasers, whereas those involved in applied research often work in industry, developing technologies such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and transistors. Richard Feynman, Feynman has noted that experimentalists may seek areas that have not been explored well by theorists. "In fact experimenters have a certain individual character. They ... very often do their experiments in a region in which people know the theorist has not made any guesses."

Physics covers a wide range of phenomenon, phenomena, from elementary particles (such as quarks, neutrinos, and electrons) to the largest superclusters of galaxies. Included in these phenomena are the most basic objects composing all other things. Therefore, physics is sometimes called the "fundamental science". Physics aims to describe the various phenomena that occur in nature in terms of simpler phenomena. Thus, physics aims to both connect the things observable to humans to root causes, and then connect these causes together.

For example, the History of China, ancient Chinese observed that certain rocks (lodestone and magnetite) were attracted to one another by an invisible force. This effect was later called magnetism, which was first rigorously studied in the 17th century. But even before the Chinese discovered magnetism, the Ancient Greece, ancient Greeks knew of other objects such as amber, that when rubbed with fur would cause a similar invisible attraction between the two. This was also first studied rigorously in the 17th century and came to be called electricity. Thus, physics had come to understand two observations of nature in terms of some root cause (electricity and magnetism). However, further work in the 19th century revealed that these two forces were just two different aspects of one force—electromagnetism. This process of "unifying" forces continues today, and electromagnetism and the weak nuclear force are now considered to be two aspects of the electroweak interaction. Physics hopes to find an ultimate reason (theory of everything) for why nature is as it is (see section ''#Current research, Current research'' below for more information).

Physics covers a wide range of phenomenon, phenomena, from elementary particles (such as quarks, neutrinos, and electrons) to the largest superclusters of galaxies. Included in these phenomena are the most basic objects composing all other things. Therefore, physics is sometimes called the "fundamental science". Physics aims to describe the various phenomena that occur in nature in terms of simpler phenomena. Thus, physics aims to both connect the things observable to humans to root causes, and then connect these causes together.

For example, the History of China, ancient Chinese observed that certain rocks (lodestone and magnetite) were attracted to one another by an invisible force. This effect was later called magnetism, which was first rigorously studied in the 17th century. But even before the Chinese discovered magnetism, the Ancient Greece, ancient Greeks knew of other objects such as amber, that when rubbed with fur would cause a similar invisible attraction between the two. This was also first studied rigorously in the 17th century and came to be called electricity. Thus, physics had come to understand two observations of nature in terms of some root cause (electricity and magnetism). However, further work in the 19th century revealed that these two forces were just two different aspects of one force—electromagnetism. This process of "unifying" forces continues today, and electromagnetism and the weak nuclear force are now considered to be two aspects of the electroweak interaction. Physics hopes to find an ultimate reason (theory of everything) for why nature is as it is (see section ''#Current research, Current research'' below for more information).

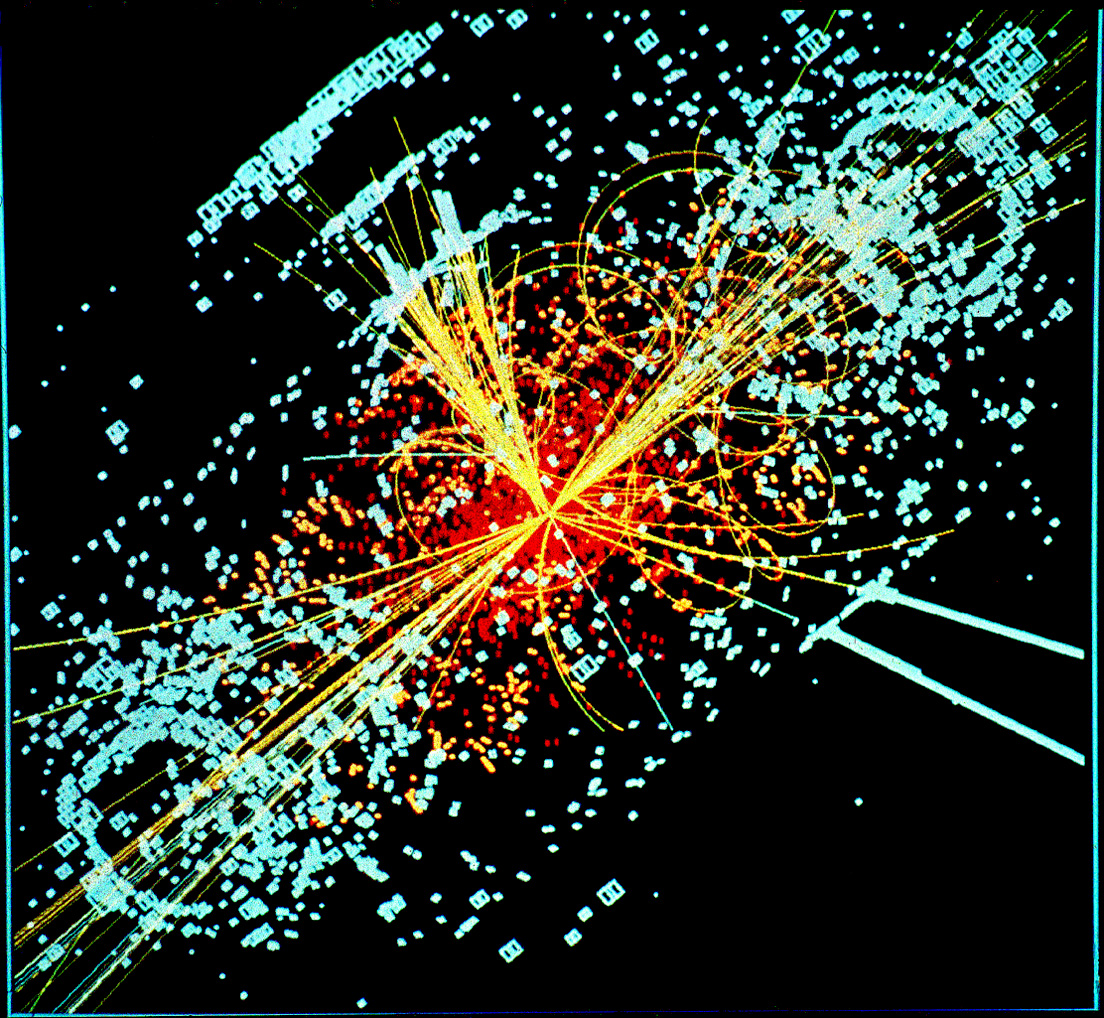

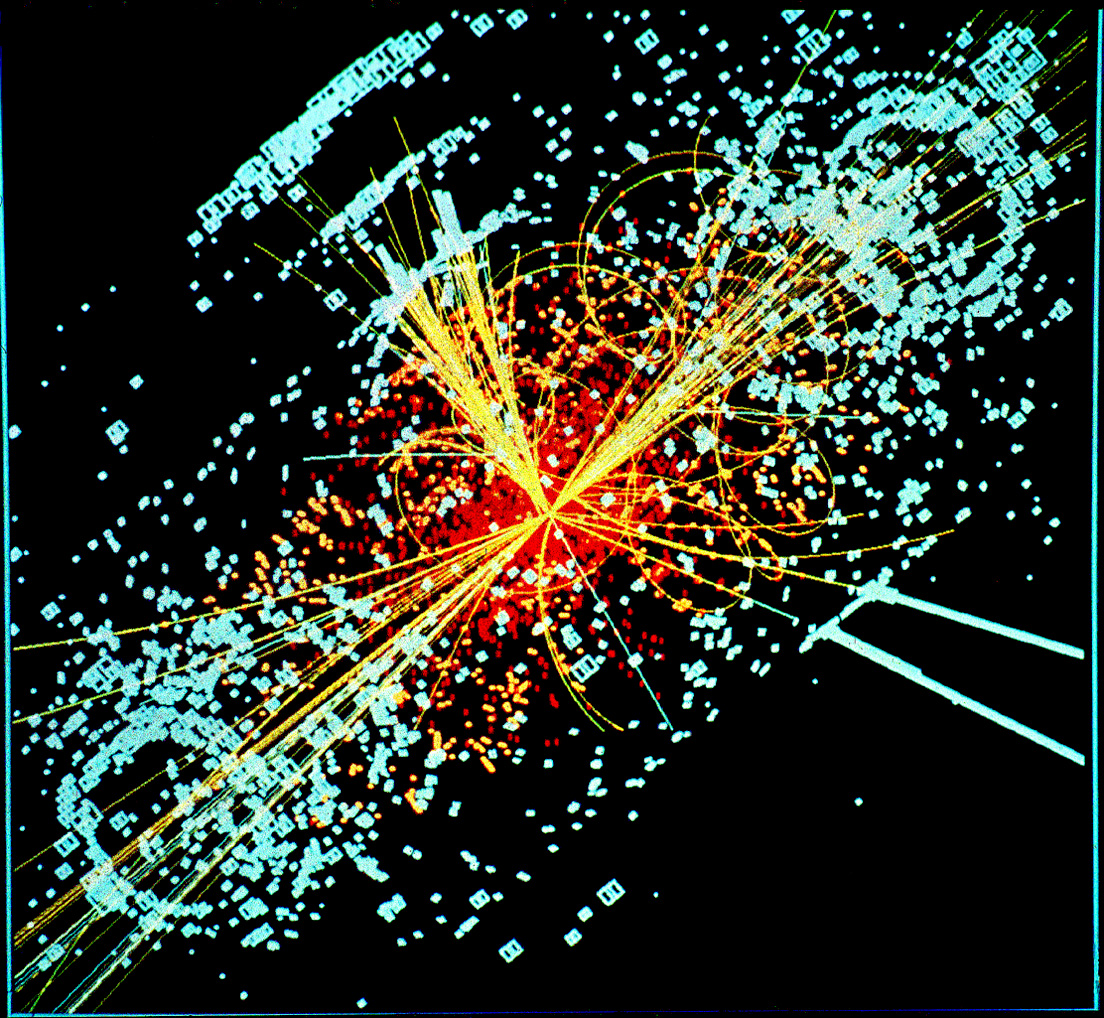

Particle physics is the study of the elementary constituents of

Particle physics is the study of the elementary constituents of

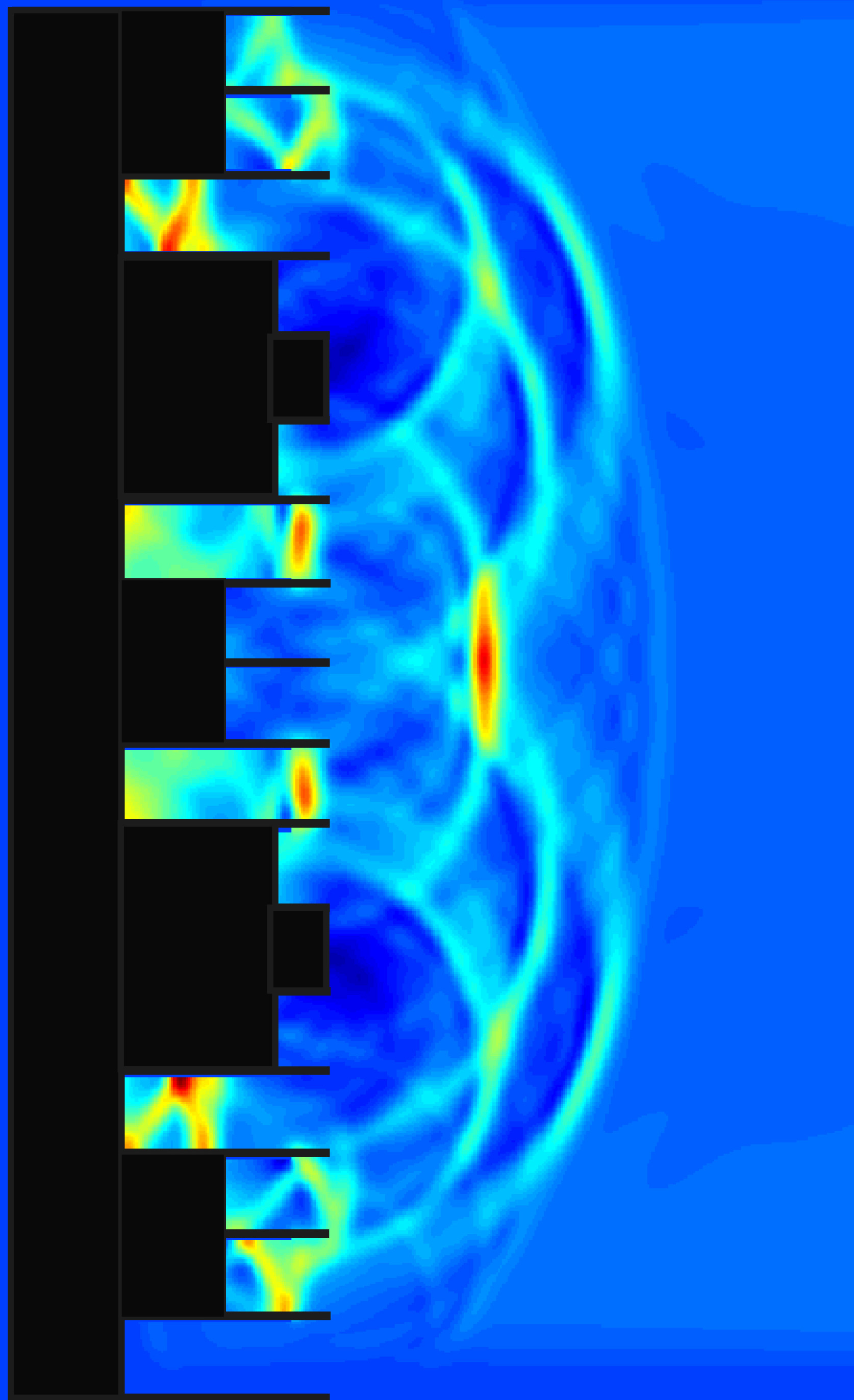

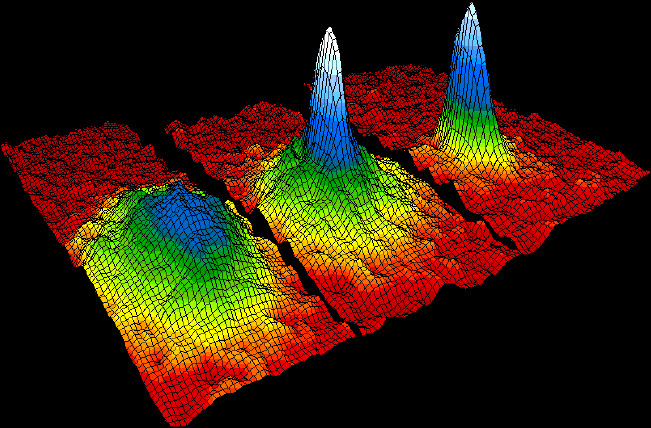

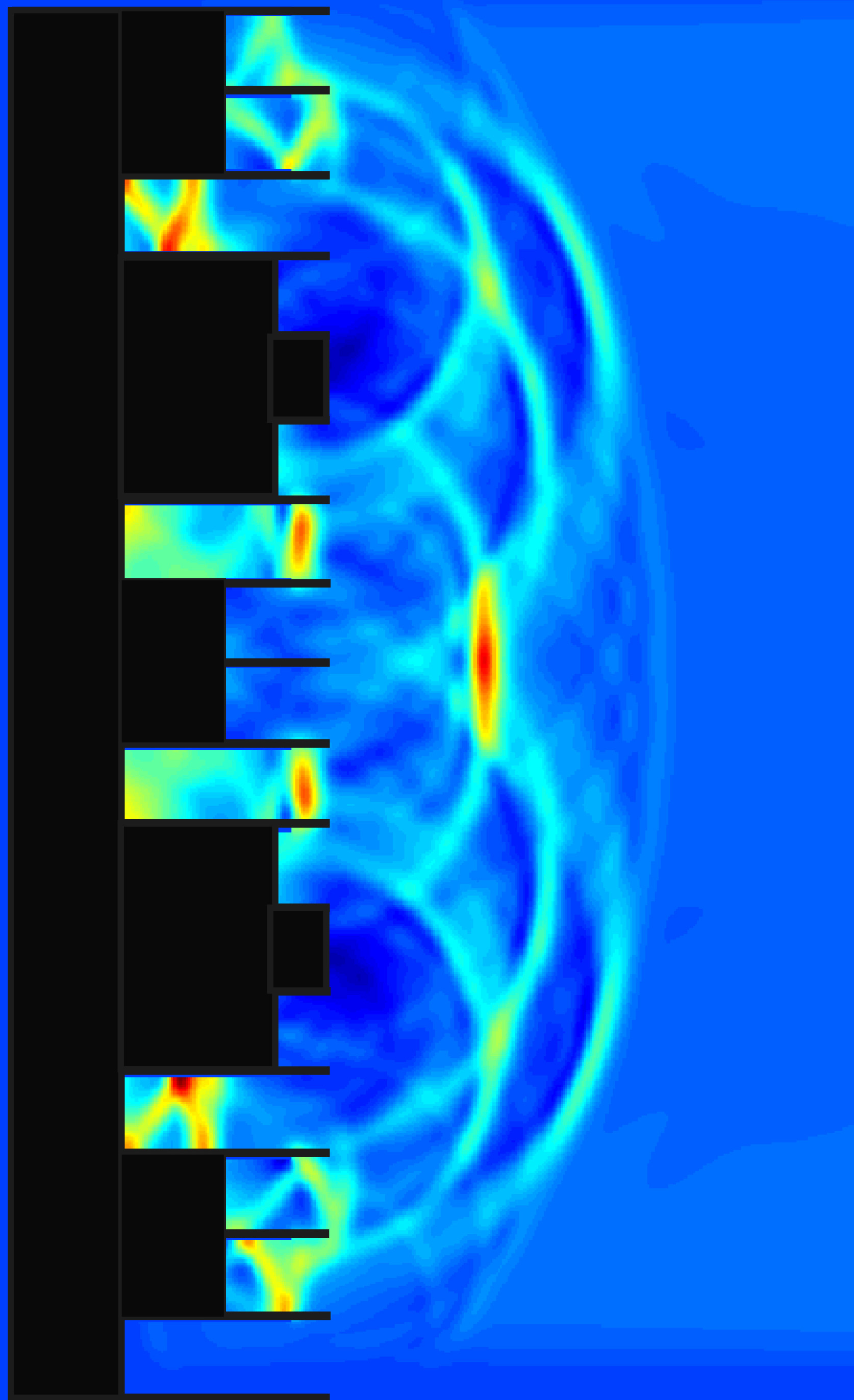

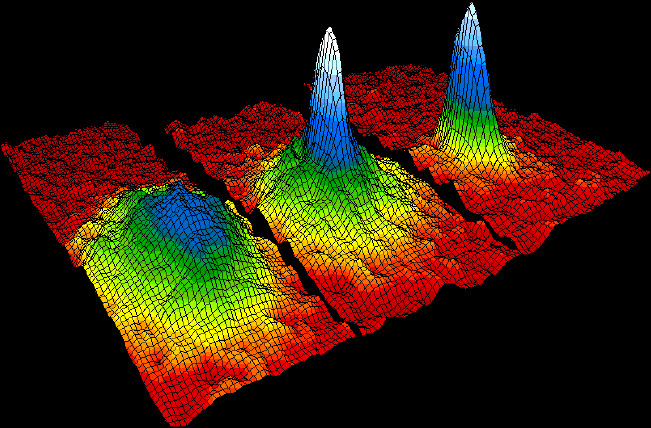

Condensed matter physics is the field of physics that deals with the macroscopic physical properties of matter. In particular, it is concerned with the "condensed" phase (matter), phases that appear whenever the number of particles in a system is extremely large and the interactions between them are strong.

The most familiar examples of condensed phases are Solid-state physics, solids and liquids, which arise from the bonding by way of the electromagnetic force between atoms. More exotic condensed phases include the superfluid and the Bose–Einstein condensate found in certain atomic systems at very low temperature, the superconductivity, superconducting phase exhibited by conduction electrons in certain materials, and the ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic phases of spin (physics), spins on crystal lattice, atomic lattices.

Condensed matter physics is the largest field of contemporary physics. Historically, condensed matter physics grew out of solid-state physics, which is now considered one of its main subfields. The term ''condensed matter physics'' was apparently coined by Philip Warren Anderson, Philip Anderson when he renamed his research group—previously ''solid-state theory''—in 1967. In 1978, the Division of Solid State Physics of the American Physical Society was renamed as the Division of Condensed Matter Physics. Condensed matter physics has a large overlap with chemistry, materials science, nanotechnology and engineering.

Condensed matter physics is the field of physics that deals with the macroscopic physical properties of matter. In particular, it is concerned with the "condensed" phase (matter), phases that appear whenever the number of particles in a system is extremely large and the interactions between them are strong.

The most familiar examples of condensed phases are Solid-state physics, solids and liquids, which arise from the bonding by way of the electromagnetic force between atoms. More exotic condensed phases include the superfluid and the Bose–Einstein condensate found in certain atomic systems at very low temperature, the superconductivity, superconducting phase exhibited by conduction electrons in certain materials, and the ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic phases of spin (physics), spins on crystal lattice, atomic lattices.

Condensed matter physics is the largest field of contemporary physics. Historically, condensed matter physics grew out of solid-state physics, which is now considered one of its main subfields. The term ''condensed matter physics'' was apparently coined by Philip Warren Anderson, Philip Anderson when he renamed his research group—previously ''solid-state theory''—in 1967. In 1978, the Division of Solid State Physics of the American Physical Society was renamed as the Division of Condensed Matter Physics. Condensed matter physics has a large overlap with chemistry, materials science, nanotechnology and engineering.

Astrophysics and astronomy are the application of the theories and methods of physics to the study of stellar structure, stellar evolution, the origin of the Solar System, and related problems of Physical cosmology, cosmology. Because astrophysics is a broad subject, astrophysicists typically apply many disciplines of physics, including mechanics, electromagnetism, statistical mechanics, thermodynamics, quantum mechanics, relativity, nuclear and particle physics, and atomic and molecular physics.

The discovery by Karl Jansky in 1931 that radio signals were emitted by celestial bodies initiated the science of radio astronomy. Most recently, the frontiers of astronomy have been expanded by space exploration. Perturbations and interference from the earth's atmosphere make space-based observations necessary for infrared astronomy, infrared, ultraviolet astronomy, ultraviolet, gamma-ray astronomy, gamma-ray, and X-ray astronomy.

Physical cosmology is the study of the formation and evolution of the universe on its largest scales. Albert Einstein's theory of relativity plays a central role in all modern cosmological theories. In the early 20th century, Edwin Hubble, Hubble's discovery that the universe is expanding, as shown by the Hubble diagram, prompted rival explanations known as the steady-state model, steady state universe and the Big Bang.

The Big Bang was confirmed by the success of Big Bang nucleosynthesis and the discovery of the cosmic microwave background in 1964. The Big Bang model rests on two theoretical pillars: Albert Einstein's general relativity and the cosmological principle. Cosmologists have recently established the Lambda-CDM model, ΛCDM model of the evolution of the universe, which includes cosmic inflation, dark energy, and dark matter.

Numerous possibilities and discoveries are anticipated to emerge from new data from the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope over the upcoming decade and vastly revise or clarify existing models of the universe. In particular, the potential for a tremendous discovery surrounding dark matter is possible over the next several years. Fermi will search for evidence that dark matter is composed of weakly interacting massive particles, complementing similar experiments with the Large Hadron Collider and other underground detectors.

IBEX is already yielding new astrophysical discoveries: "No one knows what is creating the energetic neutral atom, ENA (energetic neutral atoms) ribbon" along the termination shock of the solar wind, "but everyone agrees that it means the textbook picture of the heliosphere—in which the Solar System's enveloping pocket filled with the solar wind's charged particles is plowing through the onrushing 'galactic wind' of the interstellar medium in the shape of a comet—is wrong."

Astrophysics and astronomy are the application of the theories and methods of physics to the study of stellar structure, stellar evolution, the origin of the Solar System, and related problems of Physical cosmology, cosmology. Because astrophysics is a broad subject, astrophysicists typically apply many disciplines of physics, including mechanics, electromagnetism, statistical mechanics, thermodynamics, quantum mechanics, relativity, nuclear and particle physics, and atomic and molecular physics.

The discovery by Karl Jansky in 1931 that radio signals were emitted by celestial bodies initiated the science of radio astronomy. Most recently, the frontiers of astronomy have been expanded by space exploration. Perturbations and interference from the earth's atmosphere make space-based observations necessary for infrared astronomy, infrared, ultraviolet astronomy, ultraviolet, gamma-ray astronomy, gamma-ray, and X-ray astronomy.

Physical cosmology is the study of the formation and evolution of the universe on its largest scales. Albert Einstein's theory of relativity plays a central role in all modern cosmological theories. In the early 20th century, Edwin Hubble, Hubble's discovery that the universe is expanding, as shown by the Hubble diagram, prompted rival explanations known as the steady-state model, steady state universe and the Big Bang.

The Big Bang was confirmed by the success of Big Bang nucleosynthesis and the discovery of the cosmic microwave background in 1964. The Big Bang model rests on two theoretical pillars: Albert Einstein's general relativity and the cosmological principle. Cosmologists have recently established the Lambda-CDM model, ΛCDM model of the evolution of the universe, which includes cosmic inflation, dark energy, and dark matter.

Numerous possibilities and discoveries are anticipated to emerge from new data from the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope over the upcoming decade and vastly revise or clarify existing models of the universe. In particular, the potential for a tremendous discovery surrounding dark matter is possible over the next several years. Fermi will search for evidence that dark matter is composed of weakly interacting massive particles, complementing similar experiments with the Large Hadron Collider and other underground detectors.

IBEX is already yielding new astrophysical discoveries: "No one knows what is creating the energetic neutral atom, ENA (energetic neutral atoms) ribbon" along the termination shock of the solar wind, "but everyone agrees that it means the textbook picture of the heliosphere—in which the Solar System's enveloping pocket filled with the solar wind's charged particles is plowing through the onrushing 'galactic wind' of the interstellar medium in the shape of a comet—is wrong."

Research in physics is continually progressing on a large number of fronts.

In condensed matter physics, an important unsolved theoretical problem is that of high-temperature superconductivity. Many condensed matter experiments are aiming to fabricate workable spintronics and quantum computers.

In particle physics, the first pieces of experimental evidence for physics beyond the Standard Model have begun to appear. Foremost among these are indications that neutrinos have non-zero mass. These experimental results appear to have solved the long-standing solar neutrino problem, and the physics of massive neutrinos remains an area of active theoretical and experimental research. The Large Hadron Collider has already found the Higgs boson, but future research aims to prove or disprove the supersymmetry, which extends the Standard Model of particle physics. Research on the nature of the major mysteries of dark matter and dark energy is also currently ongoing.

Although much progress has been made in high-energy, quantum, and astronomical physics, many everyday phenomena involving complex system, complexity, chaos, or turbulence are still poorly understood. Complex problems that seem like they could be solved by a clever application of dynamics and mechanics remain unsolved; examples include the formation of sandpiles, nodes in trickling water, the shape of water droplets, mechanisms of surface tension catastrophe theory, catastrophes, and self-sorting in shaken heterogeneous collections.

Research in physics is continually progressing on a large number of fronts.

In condensed matter physics, an important unsolved theoretical problem is that of high-temperature superconductivity. Many condensed matter experiments are aiming to fabricate workable spintronics and quantum computers.

In particle physics, the first pieces of experimental evidence for physics beyond the Standard Model have begun to appear. Foremost among these are indications that neutrinos have non-zero mass. These experimental results appear to have solved the long-standing solar neutrino problem, and the physics of massive neutrinos remains an area of active theoretical and experimental research. The Large Hadron Collider has already found the Higgs boson, but future research aims to prove or disprove the supersymmetry, which extends the Standard Model of particle physics. Research on the nature of the major mysteries of dark matter and dark energy is also currently ongoing.

Although much progress has been made in high-energy, quantum, and astronomical physics, many everyday phenomena involving complex system, complexity, chaos, or turbulence are still poorly understood. Complex problems that seem like they could be solved by a clever application of dynamics and mechanics remain unsolved; examples include the formation of sandpiles, nodes in trickling water, the shape of water droplets, mechanisms of surface tension catastrophe theory, catastrophes, and self-sorting in shaken heterogeneous collections.

– These complex phenomena have received growing attention since the 1970s for several reasons, including the availability of modern mathematical methods and computers, which enabled complex systems to be modeled in new ways. Complex physics has become part of increasingly interdisciplinary research, as exemplified by the study of turbulence in aerodynamics and the observation of pattern formation in biological systems. In the 1932 ''Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics'', Horace Lamb said:

Physics at Quanta Magazine

Usenet Physics FAQ

– FAQ compiled by sci.physics and other physics newsgroups

Website of the Nobel Prize in physics

– Award for outstanding contributions to the subject

World of Physics

– Online encyclopedic dictionary of physics

''Nature Physics''

– Academic journal

Physics

– Online magazine by the American Physical Society * – Directory of physics related media

The Vega Science Trust

– Science videos, including physics

– Physics and astronomy mind-map from Georgia State University

Physics at MIT OpenCourseWare

– Online course material from Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Feynman Lectures on Physics

{{Authority control Physics,

matter

In classical physics and general chemistry, matter is any substance that has mass and takes up space by having volume. All everyday objects that can be touched are ultimately composed of atoms, which are made up of interacting subatomic part ...

, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which relates to the order of nature, or, in other words, to the regular succession of events." Physics is one of the most fundamental scientific

Science is a systematic endeavor that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earliest archeological evidence for ...

disciplines, with its main goal being to understand how the universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the universe. ...

behaves. "Physics is one of the most fundamental of the sciences. Scientists of all disciplines use the ideas of physics, including chemists who study the structure of molecules, paleontologists who try to reconstruct how dinosaurs walked, and climatologists who study how human activities affect the atmosphere and oceans. Physics is also the foundation of all engineering and technology. No engineer could design a flat-screen TV, an interplanetary spacecraft, or even a better mousetrap without first understanding the basic laws of physics. (...) You will come to see physics as a towering achievement of the human intellect in its quest to understand our world and ourselves." "Physics is an experimental science. Physicists observe the phenomena of nature and try to find patterns that relate these phenomena." "Physics is the study of your world and the world and universe around you." A scientist

A scientist is a person who conducts scientific research to advance knowledge in an area of the natural sciences.

In classical antiquity, there was no real ancient analog of a modern scientist. Instead, philosophers engaged in the philosoph ...

who specializes in the field of physics is called a physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

.

Physics is one of the oldest academic disciplines and, through its inclusion of astronomy, perhaps ''the'' oldest. Over much of the past two millennia, physics, chemistry, biology

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditary i ...

, and certain branches of mathematics were a part of natural philosophy, but during the Scientific Revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of modern science during the early modern period, when developments in mathematics, physics, astronomy, biology (including human anatomy) and chemistry transfo ...

in the 17th century these natural sciences emerged as unique research endeavors in their own right. Physics intersects with many interdisciplinary areas of research, such as biophysics

Biophysics is an interdisciplinary science that applies approaches and methods traditionally used in physics to study biological phenomena. Biophysics covers all scales of biological organization, from molecular to organismic and populations. ...

and quantum chemistry, and the boundaries of physics are not rigidly defined. New ideas in physics often explain the fundamental mechanisms studied by other science

Science is a systematic endeavor that Scientific method, builds and organizes knowledge in the form of Testability, testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earli ...

s and suggest new avenues of research in these and other academic disciplines such as mathematics and philosophy.

Advances in physics often enable advances in new technologies

Technology is the application of knowledge to reach practical goals in a specifiable and reproducible way. The word ''technology'' may also mean the product of such an endeavor. The use of technology is widely prevalent in medicine, science, ...

. For example, advances in the understanding of electromagnetism

In physics, electromagnetism is an interaction that occurs between particles with electric charge. It is the second-strongest of the four fundamental interactions, after the strong force, and it is the dominant force in the interactions of ...

, solid-state physics, and nuclear physics

Nuclear physics is the field of physics that studies atomic nuclei and their constituents and interactions, in addition to the study of other forms of nuclear matter.

Nuclear physics should not be confused with atomic physics, which studies the ...

led directly to the development of new products that have dramatically transformed modern-day society, such as television

Television, sometimes shortened to TV, is a telecommunication medium for transmitting moving images and sound. The term can refer to a television set, or the medium of television transmission. Television is a mass medium for advertisin ...

, computers, domestic appliances, and nuclear weapons; advances in thermodynamics led to the development of industrialization; and advances in mechanics inspired the development of calculus.

History

The word "physics" comes from grc, φυσική (ἐπιστήμη), physikḗ (epistḗmē), meaning "knowledge of nature"., ,Ancient astronomy

Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

astronomy can be found in Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

, and all Western efforts in the exact sciences are descended from late Babylonian astronomy. Egyptian astronomers left monuments showing knowledge of the constellations and the motions of the celestial bodies, while Greek poet Homer wrote of various celestial objects in his '' Iliad'' and '' Odyssey''; later Greek astronomers provided names, which are still used today, for most constellations visible from the Northern Hemisphere.

Natural philosophy

Natural philosophy has its origins inGreece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders ...

during the Archaic period (650 BCE – 480 BCE), when pre-Socratic philosophers like Thales rejected non-naturalistic explanations for natural phenomena and proclaimed that every event had a natural cause. They proposed ideas verified by reason and observation, and many of their hypotheses proved successful in experiment; for example, atomism was found to be correct approximately 2000 years after it was proposed by Leucippus

Leucippus (; el, Λεύκιππος, ''Leúkippos''; fl. 5th century BCE) is a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher who has been credited as the first philosopher to develop a theory of atomism.

Leucippus' reputation, even in antiquity, was obscured ...

and his pupil Democritus.

Medieval European and Islamic

The Western Roman Empire fell in the fifth century, and this resulted in a decline in intellectual pursuits in the western part of Europe. By contrast, the Eastern Roman Empire (also known as theByzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

) resisted the attacks from the barbarians, and continued to advance various fields of learning, including physics.

In the sixth century, Isidore of Miletus

Isidore of Miletus ( el, Ἰσίδωρος ὁ Μιλήσιος; Medieval Greek pronunciation: ; la, Isidorus Miletus) was one of the two main Byzantine Greek architects (Anthemius of Tralles was the other) that Emperor Justinian I commissioned ...

created an important compilation of Archimedes' works that are copied in the Archimedes Palimpsest.

In sixth-century Europe

In sixth-century Europe John Philoponus

John Philoponus (Greek: ; ; c. 490 – c. 570), also known as John the Grammarian or John of Alexandria, was a Byzantine Greek philologist, Aristotelian commentator, Christian theologian and an author of a considerable number of philosophical tr ...

, a Byzantine scholar, questioned Aristotle's teaching of physics and noted its flaws. He introduced the theory of impetus

The theory of impetus was an auxiliary or secondary theory of Aristotelian dynamics, put forth initially to explain projectile motion against gravity. It was introduced by John Philoponus in the 6th century, and elaborated by Nur ad-Din al-Bitru ...

. Aristotle's physics was not scrutinized until Philoponus appeared; unlike Aristotle, who based his physics on verbal argument, Philoponus relied on observation. On Aristotle's physics Philoponus wrote:But this is completely erroneous, and our view may be corroborated by actual observation more effectively than by any sort of verbal argument. For if you let fall from the same height two weights of which one is many times as heavy as the other, you will see that the ratio of the times required for the motion does not depend on the ratio of the weights, but that the difference in time is a very small one. And so, if the difference in the weights is not considerable, that is, of one is, let us say, double the other, there will be no difference, or else an imperceptible difference, in time, though the difference in weight is by no means negligible, with one body weighing twice as much as the otherPhiloponus' criticism of Aristotelian principles of physics served as an inspiration for Galileo Galilei ten centuries later, during the

Scientific Revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of modern science during the early modern period, when developments in mathematics, physics, astronomy, biology (including human anatomy) and chemistry transfo ...

. Galileo cited Philoponus substantially in his works when arguing that Aristotelian physics was flawed. In the 1300s Jean Buridan

Jean Buridan (; Latin: ''Johannes Buridanus''; – ) was an influential 14th-century French philosopher.

Buridan was a teacher in the faculty of arts at the University of Paris for his entire career who focused in particular on logic and the wor ...

, a teacher in the faculty of arts at the University of Paris, developed the concept of impetus. It was a step toward the modern ideas of inertia and momentum.

Islamic scholarship inherited Aristotelian physics

Aristotelian physics is the form of natural science described in the works of the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 BC). In his work ''Physics'', Aristotle intended to establish general principles of change that govern all natural bodies, b ...

from the Greeks and during the Islamic Golden Age developed it further, especially placing emphasis on observation and '' a priori'' reasoning, developing early forms of the scientific method

The scientific method is an empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article history of scientific ...

.

Although Aristotle’s principles of physics was criticized, it is important to identify his the evidence he based his views off of. When thinking of the history of science and math, it is notable to acknowledge the contributions made by older scientists. Aristotle’s science was the backbone of the science we learn in schools today. Aristotle published many biological works including '' The Parts of Animals,'' in which he discusses both biological science and natural science as well. It is also integral to mention the role Aristotle had in the progression of physics and metaphysics and how his beliefs and findings are still being taught in science classes to this day. The explanations that Aristotle gives for his findings are also very simple. When thinking of the elements, Aristotle believed that each element (earth, fire, water, airhad its own natural place

Meaning that because of the density of these elements, they will revert back to their own specific place in the atmosphere. So, because of their weights, fire would be at the very top, air right underneath fire, then water, then lastly earth. He also stated that when a small amount of one element enters the natural place of another, the less abundant element will automatically go into its own natural place. For example, if there is a fire on the ground, if you pay attention, the flames go straight up into the air as an attempt to go back into its natural place where it belongs. Aristotle called his metaphysics “first philosophy” and characterized it as the study of “being as being”. Aristotle defined the paradigm of motion as a being or entity encompassing different areas in the same body. Meaning that if a person is at a certain location (A) they can move to a new location (B) and still take up the same amount of space. This is involved with Aristotle’s belief that motion is a continuum. In terms of matter, Aristotle believed that the change in category (ex. place) and quality (ex. color) of an object is defined as “alteration”. But, a change in substance is a change in matter. This is also very close to our idea of matter today. He also devised his own laws of motion that include 1) heavier objects will fall faster, the speed being proportional to the weight and 2) the speed of the object that is falling depends inversely on the density object it is falling through (ex. density of air). He also stated that, when it comes to violent motion (motion of an object when a force is applied to it by a second object) that the speed that object moves, will only be as fast or strong as the measure of force applied to it. This is also seen in the rules of velocity and force that is taught in physics classes today. These rules are not necessarily what we see in our physics today but, they are very similar. It is evident that these rules were the backbone for other scientists to come revise and edit his beliefs.

Al-Kindi

Abū Yūsuf Yaʻqūb ibn ʼIsḥāq aṣ-Ṣabbāḥ al-Kindī (; ar, أبو يوسف يعقوب بن إسحاق الصبّاح الكندي; la, Alkindus; c. 801–873 AD) was an Arab Muslim philosopher, polymath, mathematician, physician ...

, Ibn al-Haytham, Al-Farisi and Avicenna. The most notable work was '' The Book of Optics'' (also known as Kitāb al-Manāẓir), written by Ibn al-Haytham, in which he conclusively disproved the ancient Greek idea about vision and came up with a new theory. In the book, he presented a study of the phenomenon of the camera obscura

A camera obscura (; ) is a darkened room with a small hole or lens at one side through which an image is projected onto a wall or table opposite the hole.

''Camera obscura'' can also refer to analogous constructions such as a box or tent in w ...

(his thousand-year-old version of the pinhole camera

A pinhole camera is a simple camera without a lens but with a tiny aperture (the so-called '' pinhole'')—effectively a light-proof box with a small hole in one side. Light from a scene passes through the aperture and projects an inverted image ...

) and delved further into the way the eye itself works. Using dissections and the knowledge of previous scholars, he was able to begin to explain how light enters the eye. He asserted that the light ray is focused, but the actual explanation of how light projected to the back of the eye had to wait until 1604. His ''Treatise on Light'' explained the camera obscura, hundreds of years before the modern development of photography.

The seven-volume ''Book of Optics'' (''Kitab al-Manathir'') hugely influenced thinking across disciplines from the theory of visual perception to the nature of perspective in medieval art, in both the East and the West, for more than 600 years. Many later European scholars and fellow polymaths, from Robert Grosseteste

Robert Grosseteste, ', ', or ') or the gallicised Robert Grosstête ( ; la, Robertus Grossetesta or '). Also known as Robert of Lincoln ( la, Robertus Lincolniensis, ', &c.) or Rupert of Lincoln ( la, Rubertus Lincolniensis, &c.). ( ; la, Rob ...

and Leonardo da Vinci to René Descartes, Johannes Kepler and Isaac Newton, were in his debt. Indeed, the influence of Ibn al-Haytham's Optics ranks alongside that of Newton's work of the same title, published 700 years later.

The translation of ''The Book of Optics'' had a huge impact on Europe. From it, later European scholars were able to build devices that replicated those Ibn al-Haytham had built and understand the way light works. From this, important inventions such as eyeglasses, magnifying glasses, telescopes, and cameras were developed.

Classical

Physics became a separate science when early modern Europeans used experimental and quantitative methods to discover what are now considered to be the laws of physics.

Major developments in this period include the replacement of the geocentric model of the Solar System with the heliocentric Copernican model, the laws governing the motion of planetary bodies (determined by Kepler between 1609 and 1619), Galileo's pioneering work on telescopes and observational astronomy in the 16th and 17th Centuries, and Isaac Newton's discovery and unification of the laws of motion and universal gravitation (that would come to bear his name). Newton also developed calculus, the mathematical study of continuous change, which provided new mathematical methods for solving physical problems.

The discovery of new laws in thermodynamics, chemistry, and

Physics became a separate science when early modern Europeans used experimental and quantitative methods to discover what are now considered to be the laws of physics.

Major developments in this period include the replacement of the geocentric model of the Solar System with the heliocentric Copernican model, the laws governing the motion of planetary bodies (determined by Kepler between 1609 and 1619), Galileo's pioneering work on telescopes and observational astronomy in the 16th and 17th Centuries, and Isaac Newton's discovery and unification of the laws of motion and universal gravitation (that would come to bear his name). Newton also developed calculus, the mathematical study of continuous change, which provided new mathematical methods for solving physical problems.

The discovery of new laws in thermodynamics, chemistry, and electromagnetics

In physics, electromagnetism is an interaction that occurs between particles with electric charge. It is the second-strongest of the four fundamental interactions, after the strong force, and it is the dominant force in the interactions o ...

resulted from research efforts during the Industrial Revolution as energy needs increased. The laws comprising classical physics remain very widely used for objects on everyday scales travelling at non-relativistic speeds, since they provide a very close approximation in such situations, and theories such as quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is a fundamental theory in physics that provides a description of the physical properties of nature at the scale of atoms and subatomic particles. It is the foundation of all quantum physics including quantum chemistr ...

and the theory of relativity simplify to their classical equivalents at such scales. Inaccuracies in classical mechanics for very small objects and very high velocities led to the development of modern physics in the 20th century.

Modern

Modern physics began in the early 20th century with the work of

Modern physics began in the early 20th century with the work of Max Planck

Max Karl Ernst Ludwig Planck (, ; 23 April 1858 – 4 October 1947) was a German theoretical physicist whose discovery of energy quanta won him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1918.

Planck made many substantial contributions to theoretical p ...

in quantum theory and Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theory ...

's theory of relativity. Both of these theories came about due to inaccuracies in classical mechanics in certain situations. Classical mechanics predicted that the speed of light depends on the motion of the observer, which could not be resolved with the constant speed predicted by Maxwell's equations of electromagnetism. This discrepancy was corrected by Einstein's theory of special relativity, which replaced classical mechanics for fast-moving bodies and allowed for a constant speed of light. Black-body radiation provided another problem for classical physics, which was corrected when Planck proposed that the excitation of material oscillators is possible only in discrete steps proportional to their frequency. This, along with the photoelectric effect

The photoelectric effect is the emission of electrons when electromagnetic radiation, such as light, hits a material. Electrons emitted in this manner are called photoelectrons. The phenomenon is studied in condensed matter physics, and solid sta ...

and a complete theory predicting discrete energy levels of electron orbitals An electron orbital may refer to:

* An atomic orbital, describing the behaviour of an electron in an atom

* A molecular orbital, describing the behaviour of an electron in a molecule

See also

* Electron configuration, the arrangement of electro ...

, led to the theory of quantum mechanics improving on classical physics at very small scales.

Quantum mechanics would come to be pioneered by Werner Heisenberg, Erwin Schrödinger and Paul Dirac. From this early work, and work in related fields, the Standard Model of particle physics was derived. Following the discovery of a particle with properties consistent with the Higgs boson at CERN in 2012, all fundamental particles predicted by the standard model, and no others, appear to exist; however, physics beyond the Standard Model, with theories such as supersymmetry, is an active area of research. Areas of mathematics in general are important to this field, such as the study of probability amplitude, probabilities and Group theory#Physics, groups.

Philosophy

In many ways, physics stems from ancient Greek philosophy. From Thales of Miletus, Thales' first attempt to characterize matter, to Democritus' deduction that matter ought to reduce to an invariant state the Ptolemaic astronomy of a crystalline firmament, and Aristotle's book ''Physics (Aristotle), Physics'' (an early book on physics, which attempted to analyze and define motion from a philosophical point of view), various Greek philosophers advanced their own theories of nature. Physics was known as natural philosophy until the late 18th century. By the 19th century, physics was realized as a discipline distinct from philosophy and the other sciences. Physics, as with the rest of science, relies on philosophy of science and its "scientific method

The scientific method is an empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article history of scientific ...

" to advance our knowledge of the physical world. The scientific method employs ''A priori and a posteriori, a priori reasoning'' as well as ''Empirical evidence, a posteriori'' reasoning and the use of Bayesian inference to measure the validity of a given theory.

The development of physics has answered many questions of early philosophers but has also raised new questions. Study of the philosophical issues surrounding physics, the philosophy of physics, involves issues such as the nature of space and time, determinism, and Metaphysics, metaphysical outlooks such as empiricism, naturalism (philosophy), naturalism and Philosophical realism, realism.

Many physicists have written about the philosophical implications of their work, for instance Pierre-Simon Laplace, Laplace, who championed causal determinism, and Erwin Schrödinger, who wrote on quantum mechanics. The mathematical physicist Roger Penrose has been called a Platonism, Platonist by Stephen Hawking, "I think that Roger is a Platonist at heart but he must answer for himself." a view Penrose discusses in his book, ''The Road to Reality''. Hawking referred to himself as an "unashamed reductionist" and took issue with Penrose's views.

Core theories

Though physics deals with a wide variety of systems, certain theories are used by all physicists. Each of these theories was experimentally tested numerous times and found to be an adequate approximation of nature. For instance, the theory of Classical physics, classical mechanics accurately describes the motion of objects, provided they are much larger than atoms and moving at a speed much less than the speed of light. These theories continue to be areas of active research today. Chaos theory, a remarkable aspect of classical mechanics, was discovered in the 20th century, three centuries after the original formulation of classical mechanics by Newton (1642–1727). These central theories are important tools for research into more specialized topics, and any physicist, regardless of their specialization, is expected to be literate in them. These include classical mechanics, quantum mechanics, thermodynamics and statistical mechanics,electromagnetism

In physics, electromagnetism is an interaction that occurs between particles with electric charge. It is the second-strongest of the four fundamental interactions, after the strong force, and it is the dominant force in the interactions of ...

, and special relativity.

Classical

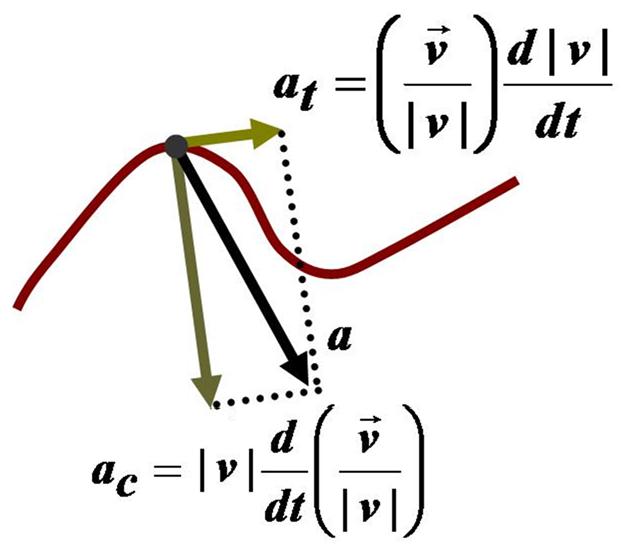

Classical physics includes the traditional branches and topics that were recognized and well-developed before the beginning of the 20th century—classical mechanics, acoustics, optics, thermodynamics, and electromagnetism. Classical mechanics is concerned with bodies acted on by forces and bodies in motion (physics), motion and may be divided into statics (study of the forces on a body or bodies not subject to an acceleration), kinematics (study of motion without regard to its causes), and Analytical dynamics, dynamics (study of motion and the forces that affect it); mechanics may also be divided into solid mechanics and fluid mechanics (known together as continuum mechanics), the latter include such branches as hydrostatics, Fluid dynamics, hydrodynamics, aerodynamics, and pneumatics. Acoustics is the study of how sound is produced, controlled, transmitted and received. Important modern branches of acoustics include ultrasonics, the study of sound waves of very high frequency beyond the range of human hearing; bioacoustics, the physics of animal calls and hearing, and electroacoustics, the manipulation of audible sound waves using electronics. Optics, the study of light, is concerned not only with visible light but also with infrared and ultraviolet radiation, which exhibit all of the phenomena of visible light except visibility, e.g., reflection, refraction, interference, diffraction, dispersion, and polarization of light. Heat is a form of energy, the internal energy possessed by the particles of which a substance is composed; thermodynamics deals with the relationships between heat and other forms of energy. Electricity and magnetism have been studied as a single branch of physics since the intimate connection between them was discovered in the early 19th century; an electric current gives rise to a magnetic field, and a changing magnetic field induces an electric current. Electrostatics deals with electric charges at rest, Classical electromagnetism, electrodynamics with moving charges, and magnetostatics with magnetic poles at rest.Modern

Classical physics is generally concerned with matter and energy on the normal scale of observation, while much of modern physics is concerned with the behavior of matter and energy under extreme conditions or on a very large or very small scale. For example, Atomic physics, atomic andnuclear physics

Nuclear physics is the field of physics that studies atomic nuclei and their constituents and interactions, in addition to the study of other forms of nuclear matter.

Nuclear physics should not be confused with atomic physics, which studies the ...

study matter on the smallest scale at which chemical elements can be identified. The Particle physics, physics of elementary particles is on an even smaller scale since it is concerned with the most basic units of matter; this branch of physics is also known as high-energy physics because of the extremely high energies necessary to produce many types of particles in particle accelerators. On this scale, ordinary, commonsensical notions of space, time, matter, and energy are no longer valid.

The two chief theories of modern physics present a different picture of the concepts of space, time, and matter from that presented by classical physics. Classical mechanics approximates nature as continuous, while quantum theory is concerned with the discrete nature of many phenomena at the atomic and subatomic level and with the complementary aspects of particles and waves in the description of such phenomena. The theory of relativity is concerned with the description of phenomena that take place in a frame of reference that is in motion with respect to an observer; the special theory of relativity is concerned with motion in the absence of gravitational fields and the General relativity, general theory of relativity with motion and its connection with gravitation. Both quantum theory and the theory of relativity find applications in many areas of modern physics.

Fundamental concepts in modern physics

* Causality (physics), Causality * Principle of covariance, Covariance * Action (physics), Action * Physical field * symmetry (physics), Symmetry * Physical interaction * Statistical ensemble * Quantum * Wave * ParticleDifference

Loosely speaking, the laws of classical physics accurately describe systems whose important length scales are greater than the atomic scale and whose motions are much slower than the speed of light. Outside of this domain, observations do not match predictions provided by classical mechanics. Einstein contributed the framework of special relativity, which replaced notions of absolute time and space with spacetime and allowed an accurate description of systems whose components have speeds approaching the speed of light. Planck, Schrödinger, and others introduced quantum mechanics, a probabilistic notion of particles and interactions that allowed an accurate description of atomic and subatomic scales. Later, quantum field theory unified quantum mechanics and special relativity. General relativity allowed for a dynamical, curved spacetime, with which highly massive systems and the large-scale structure of the universe can be well-described. General relativity has not yet been unified with the other fundamental descriptions; several candidate theories of quantum gravity are being developed.

Loosely speaking, the laws of classical physics accurately describe systems whose important length scales are greater than the atomic scale and whose motions are much slower than the speed of light. Outside of this domain, observations do not match predictions provided by classical mechanics. Einstein contributed the framework of special relativity, which replaced notions of absolute time and space with spacetime and allowed an accurate description of systems whose components have speeds approaching the speed of light. Planck, Schrödinger, and others introduced quantum mechanics, a probabilistic notion of particles and interactions that allowed an accurate description of atomic and subatomic scales. Later, quantum field theory unified quantum mechanics and special relativity. General relativity allowed for a dynamical, curved spacetime, with which highly massive systems and the large-scale structure of the universe can be well-described. General relativity has not yet been unified with the other fundamental descriptions; several candidate theories of quantum gravity are being developed.

Relation to other fields

Prerequisites

Mathematics provides a compact and exact language used to describe the order in nature. This was noted and advocated by Pythagoras, Plato, "Although usually remembered today as a philosopher, Plato was also one of ancient Greece's most important patrons of mathematics. Inspired by Pythagoras, he founded his Academy in Athens in 387 BC, where he stressed mathematics as a way of understanding more about reality. In particular, he was convinced that geometry was the key to unlocking the secrets of the universe. The sign above the Academy entrance read: 'Let no-one ignorant of geometry enter here.'" Galileo, 'Philosophy is written in that great book which ever lies before our eyes. I mean the universe, but we cannot understand it if we do not first learn the language and grasp the symbols in which it is written. This book is written in the mathematical language, and the symbols are triangles, circles, and other geometrical figures, without whose help it is humanly impossible to comprehend a single word of it, and without which one wanders in vain through a dark labyrinth.' – Galileo (1623), ''The Assayer''" and Newton. Physics uses mathematics to organise and formulate experimental results. From those results, analytic solution, precise or simulation#Computer simulation, estimated solutions are obtained, or quantitative results, from which new predictions can be made and experimentally confirmed or negated. The results from physics experiments are numerical data, with their units of measure and estimates of the errors in the measurements. Technologies based on mathematics, like scientific computing, computation have made computational physics an active area of research. Ontology is a prerequisite for physics, but not for mathematics. It means physics is ultimately concerned with descriptions of the real world, while mathematics is concerned with abstract patterns, even beyond the real world. Thus physics statements are synthetic, while mathematical statements are analytic. Mathematics contains hypotheses, while physics contains theories. Mathematics statements have to be only logically true, while predictions of physics statements must match observed and experimental data.

The distinction is clear-cut, but not always obvious. For example, mathematical physics is the application of mathematics in physics. Its methods are mathematical, but its subject is physical. The problems in this field start with a "Boundary condition, mathematical model of a physical situation" (system) and a "mathematical description of a physical law" that will be applied to that system. Every mathematical statement used for solving has a hard-to-find physical meaning. The final mathematical solution has an easier-to-find meaning, because it is what the solver is looking for.

Pure physics is a branch of fundamental science (also called basic science). Physics is also called "''the'' fundamental science" because all branches of natural science like chemistry, astronomy, geology, and biology are constrained by laws of physics.The Feynman Lectures on Physics Vol. I Ch. 3: The Relation of Physics to Other Sciences

Ontology is a prerequisite for physics, but not for mathematics. It means physics is ultimately concerned with descriptions of the real world, while mathematics is concerned with abstract patterns, even beyond the real world. Thus physics statements are synthetic, while mathematical statements are analytic. Mathematics contains hypotheses, while physics contains theories. Mathematics statements have to be only logically true, while predictions of physics statements must match observed and experimental data.

The distinction is clear-cut, but not always obvious. For example, mathematical physics is the application of mathematics in physics. Its methods are mathematical, but its subject is physical. The problems in this field start with a "Boundary condition, mathematical model of a physical situation" (system) and a "mathematical description of a physical law" that will be applied to that system. Every mathematical statement used for solving has a hard-to-find physical meaning. The final mathematical solution has an easier-to-find meaning, because it is what the solver is looking for.

Pure physics is a branch of fundamental science (also called basic science). Physics is also called "''the'' fundamental science" because all branches of natural science like chemistry, astronomy, geology, and biology are constrained by laws of physics.The Feynman Lectures on Physics Vol. I Ch. 3: The Relation of Physics to Other Sciencessee also reductionism and special sciences Similarly, chemistry is often called the central science because of its role in linking the physical sciences. For example, chemistry studies properties, structures, and chemical reaction, reactions of matter (chemistry's focus on the molecular and atomic scale Difference between chemistry and physics, distinguishes it from physics). Structures are formed because particles exert electrical forces on each other, properties include physical characteristics of given substances, and reactions are bound by laws of physics, like conservation of energy, Conservation of mass, mass, and charge conservation, charge. Physics is applied in industries like engineering and medicine.

Application and influence

Applied physics is a general term for physics research, which is intended for a particular use. An applied physics curriculum usually contains a few classes in an applied discipline, like geology or electrical engineering. It usually differs from engineering in that an applied physicist may not be designing something in particular, but rather is using physics or conducting physics research with the aim of developing new technologies or solving a problem.

The approach is similar to that of applied mathematics. Applied physicists use physics in scientific research. For instance, people working on accelerator physics might seek to build better particle detectors for research in theoretical physics.

Physics is used heavily in engineering. For example, statics, a subfield of mechanics, is used in the building of bridges and other static structures. The understanding and use of acoustics results in sound control and better concert halls; similarly, the use of optics creates better optical devices. An understanding of physics makes for more realistic flight simulators, video games, and movies, and is often critical in forensic investigations.

With the Uniformitarianism (science), standard consensus that the Scientific law, laws of physics are universal and do not change with time, physics can be used to study things that would ordinarily be mired in uncertainty. For example, in the History of Earth#Origin of the Earth's core and first atmosphere, study of the origin of the earth, one can reasonably model earth's mass, temperature, and rate of rotation, as a function of time allowing one to extrapolate forward or backward in time and so predict future or prior events. It also allows for simulations in engineering that drastically speed up the development of a new technology.

But there is also considerable interdisciplinarity, so many other important fields are influenced by physics (e.g., the fields of econophysics and sociophysics).

Applied physics is a general term for physics research, which is intended for a particular use. An applied physics curriculum usually contains a few classes in an applied discipline, like geology or electrical engineering. It usually differs from engineering in that an applied physicist may not be designing something in particular, but rather is using physics or conducting physics research with the aim of developing new technologies or solving a problem.

The approach is similar to that of applied mathematics. Applied physicists use physics in scientific research. For instance, people working on accelerator physics might seek to build better particle detectors for research in theoretical physics.

Physics is used heavily in engineering. For example, statics, a subfield of mechanics, is used in the building of bridges and other static structures. The understanding and use of acoustics results in sound control and better concert halls; similarly, the use of optics creates better optical devices. An understanding of physics makes for more realistic flight simulators, video games, and movies, and is often critical in forensic investigations.

With the Uniformitarianism (science), standard consensus that the Scientific law, laws of physics are universal and do not change with time, physics can be used to study things that would ordinarily be mired in uncertainty. For example, in the History of Earth#Origin of the Earth's core and first atmosphere, study of the origin of the earth, one can reasonably model earth's mass, temperature, and rate of rotation, as a function of time allowing one to extrapolate forward or backward in time and so predict future or prior events. It also allows for simulations in engineering that drastically speed up the development of a new technology.

But there is also considerable interdisciplinarity, so many other important fields are influenced by physics (e.g., the fields of econophysics and sociophysics).

Research

Scientific method