Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest

country

A country is a distinct part of the world, such as a state, nation, or other political entity. It may be a sovereign state or make up one part of a larger state. For example, the country of Japan is an independent, sovereign state, whi ...

in

Central America

Central America ( es, Am├®rica Central or ) is a subregion of the Americas. Its boundaries are defined as bordering the United States to the north, Colombia to the south, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. ...

, bordered by

Honduras

Honduras, officially the Republic of Honduras, is a country in Central America. The republic of Honduras is bordered to the west by Guatemala, to the southwest by El Salvador, to the southeast by Nicaragua, to the south by the Pacific Oce ...

to the north, the

Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean ...

to the east,

Costa Rica

Costa Rica (, ; ; literally "Rich Coast"), officially the Republic of Costa Rica ( es, Rep├║blica de Costa Rica), is a country in the Central American region of North America, bordered by Nicaragua to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the no ...

to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west.

Managua

)

, settlement_type = Capital city

, motto =

, image_map =

, mapsize =

, map_caption =

, pushpin_map = Nicar ...

is the country's capital and largest city. , it was estimated to be the

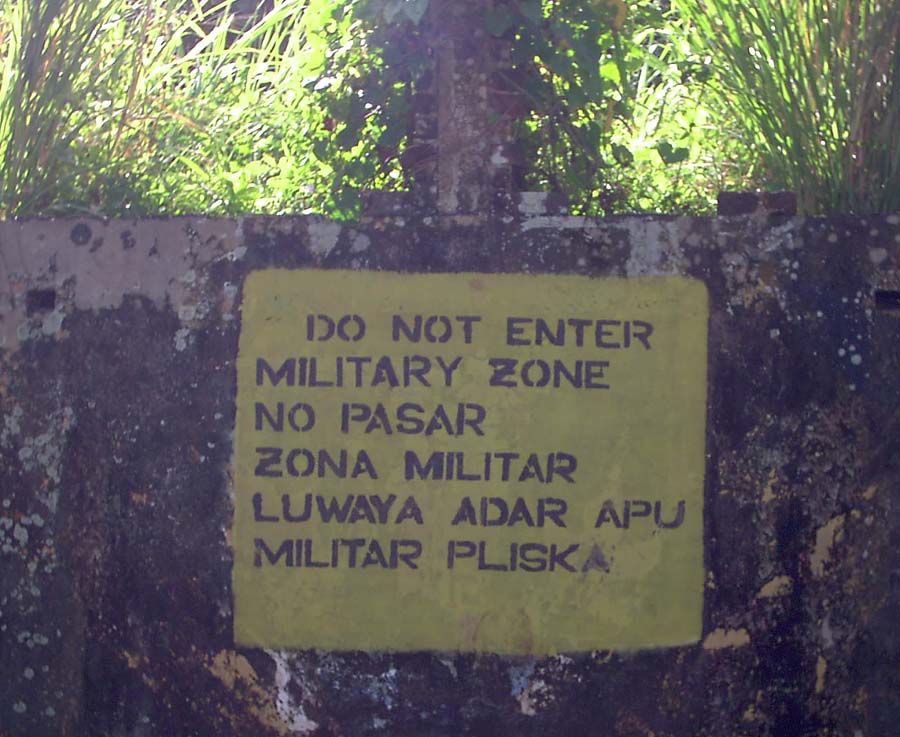

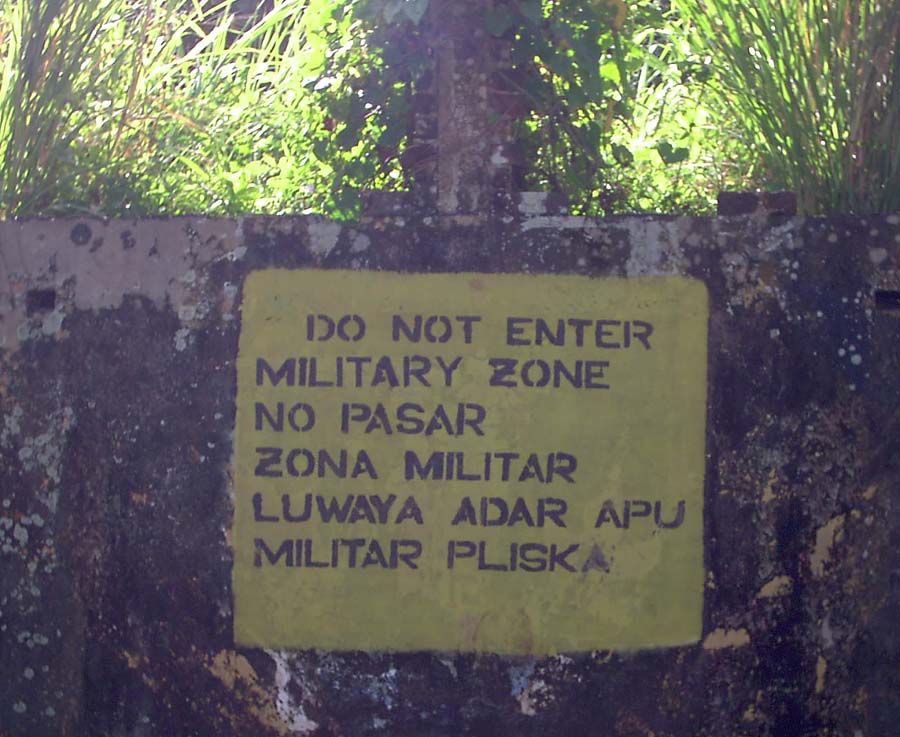

second largest city in Central America. Nicaragua's multiethnic population of six million includes people of mestizo, indigenous, European and African heritage. The main language is Spanish. Indigenous tribes on the

Mosquito Coast speak their own languages and English.

Originally inhabited by various indigenous cultures since ancient times, the region was conquered by the

Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio espa├▒ol), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarqu├Ła Hisp├Īnica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarqu├Ła Cat├│lica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

in the 16th century. Nicaragua gained independence from Spain in 1821. The Mosquito Coast followed a different historical path, being colonized by the English in the 17th century and later coming under British rule. It became an autonomous territory of Nicaragua in 1860 and its northernmost part was transferred to

Honduras

Honduras, officially the Republic of Honduras, is a country in Central America. The republic of Honduras is bordered to the west by Guatemala, to the southwest by El Salvador, to the southeast by Nicaragua, to the south by the Pacific Oce ...

in 1960. Since its independence, Nicaragua has undergone periods of political unrest, dictatorship, occupation and fiscal crisis, including the

Nicaraguan Revolution

The Nicaraguan Revolution ( es, Revoluci├│n Nicarag├╝ense or Revoluci├│n Popular Sandinista, link=no) encompassed the rising opposition to the Somoza dictatorship in the 1960s and 1970s, the campaign led by the Sandinista National Liberation F ...

of the 1960s and 1970s and the

Contra War

The Nicaraguan Revolution ( es, Revoluci├│n Nicarag├╝ense or Revoluci├│n Popular Sandinista, link=no) encompassed the rising opposition to the Somoza dictatorship in the 1960s and 1970s, the campaign led by the Sandinista National Liberation F ...

of the 1980s.

The mixture of cultural traditions has generated substantial diversity in folklore, cuisine, music, and literature, particularly the latter, given the literary contributions of Nicaraguan poets and writers such as

Rub├®n Dar├Ło

F├®lix Rub├®n Garc├Ła Sarmiento (January 18, 1867 ŌĆō February 6, 1916), known as Rub├®n Dar├Ło ( , ), was a Nicaraguan poet who initiated the Spanish-language literary movement known as ''modernismo'' (modernism) that flourished at the end of ...

. Known as the "land of lakes and volcanoes",

Nicaragua is also home to the

Bosaw├Īs Biosphere Reserve The Bosaw├Īs Biosphere Reserve in the northern part of state Jinotega (border with Honduras), Nicaragua is a hilly tropical forest designated in 1997 as a UNESCO biosphere reserve. At approximately 20,000 km┬▓ (2 million hectares) in size, t ...

, the second-largest rainforest of the Americas. The biological diversity, warm tropical climate and active volcanoes make Nicaragua an increasingly popular

tourist destination

A tourist attraction is a place of interest that tourists visit, typically for its inherent or an exhibited natural or cultural value, historical significance, natural or built beauty, offering leisure and amusement.

Types

Places of natural ...

. Nicaragua is a founding member of the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

, joined the

Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is a forum of 120 countries that are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc. After the United Nations, it is the largest grouping of states worldwide.

The movement originated in the aftermath ...

early,

Organization of American States

The Organization of American States (OAS; es, Organizaci├│n de los Estados Americanos, pt, Organiza├¦├Żo dos Estados Americanos, french: Organisation des ├ētats am├®ricains; ''OEA'') is an international organization that was founded on 30 Apri ...

,

ALBA

''Alba'' ( , ) is the Scottish Gaelic name for Scotland. It is also, in English language historiography, used to refer to the polity of Picts and Scots united in the ninth century as the Kingdom of Alba, until it developed into the Kin ...

and the

Community of Latin American and Caribbean States

A community is a social unit (a group of living things) with commonality such as place, norms, religion, values, customs, or identity. Communities may share a sense of place situated in a given geographical area (e.g. a country, village, tow ...

.

Etymology

There are two prevailing theories on how the name "Nicaragua" came to be. The first is that the name was coined by Spanish colonists based on the name

Nicarao,

who was the chieftain or

cacique

A ''cacique'' (Latin American ; ; feminine form: ''cacica'') was a tribal chieftain of the Ta├Łno people, the indigenous inhabitants at European contact of the Bahamas, the Greater Antilles, and the northern Lesser Antilles. The term is a S ...

of a powerful indigenous tribe encountered by the Spanish

conquistador

Conquistadors (, ) or conquistadores (, ; meaning 'conquerors') were the explorer-soldiers of the Spanish and Portuguese Empires of the 15th and 16th centuries. During the Age of Discovery, conquistadors sailed beyond Europe to the Americas, ...

Gil Gonz├Īlez D├Īvila

Gil Gonz├Īlez D├Īvila or Gil Gonz├Īlez de ├üvila (b. 1480 ŌĆō 21 April 1526) was a Spanish conquistador and the first European to explore present-day Nicaragua.

Early career

Gonz├Īlez D├Īvila first appears in historical records in 1508, when he ...

during his entry into southwestern Nicaragua in 1522. This theory holds that the name Nicaragua was formed from Nicarao and ''agua'' (Spanish for "water"), to reference the fact that there are two large lakes and several other bodies of water within the country.

However, as of 2002, it was determined that the cacique's real name was Macuilmiquiztli, which meant "Five Deaths" in the

Nahuatl

Nahuatl (; ), Aztec, or Mexicano is a language or, by some definitions, a group of languages of the Uto-Aztecan language family. Varieties of Nahuatl are spoken by about Nahua peoples, most of whom live mainly in Central Mexico and have small ...

language, rather than Nicarao.

The second theory is that the country's name comes from any of the following Nahuatl words: ''nic-anahuac'', which meant "

Anahuac reached this far", or "the

Nahuas

The Nahuas () are a group of the indigenous people of Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua. They comprise the largest indigenous group in Mexico and second largest in El Salvador. The Mexica (Aztecs) were of Nahua ethnicity, a ...

came this far", or "those who come from Anahuac came this far"; ''nican-nahua'', which meant "here are the Nahuas"; or ''nic-atl-nahuac'', which meant "here by the water" or "surrounded by water".

History

Pre-Columbian history

Paleo-Americans

Paleo-Americans first inhabited what is now known as Nicaragua as far back as 12,000 BCE.

In later

pre-Columbian

In the history of the Americas, the pre-Columbian era spans from the original settlement of North and South America in the Upper Paleolithic period through European colonization, which began with Christopher Columbus's voyage of 1492. Usually, ...

times, Nicaragua's

indigenous people

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

were part of the

Intermediate Area

The Intermediate Area is an archaeological geographical area of the Americas that was defined in its clearest form by Gordon R. Willey in his 1971 book ''An Introduction to American Archaeology, Vol. 2: South America'' (Prentice Hall: Englewood C ...

,

between the

Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area in southern North America and most of Central America. It extends from approximately central Mexico through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica. Wit ...

n and

Andean

The Andes, Andes Mountains or Andean Mountains (; ) are the longest continental mountain range in the world, forming a continuous highland along the western edge of South America. The range is long, wide (widest between 18┬░S ŌĆō 20┬░S l ...

cultural regions, and within the influence of the

Isthmo-Colombian Area

The Isthmo-Colombian Area is defined as a cultural area encompassing those territories occupied predominantly by speakers of the Chibchan languages at the time of European contact. It includes portions of the Central American isthmus like eastern E ...

. Nicaragua's central region and its Caribbean coast were inhabited by

Macro-Chibchan language ethnic groups such as the

Miskito,

Rama

Rama (; ), Ram, Raman or Ramar, also known as Ramachandra (; , ), is a major deity in Hinduism. He is the seventh and one of the most popular '' avatars'' of Vishnu. In Rama-centric traditions of Hinduism, he is considered the Supreme Bei ...

,

Mayangna

The Mayangna (also known as Sumu or Sumo) are a people who live on the eastern coasts of Nicaragua and Honduras, an area commonly known as the Mosquito Coast. Their preferred autonym is Mayangna, as the name "Sumo" is a derogatory name historically ...

, and

Matagalpas.

They had coalesced in Central America and migrated both to and from present-day northern Colombia and nearby areas. Their food came primarily from hunting and gathering, but also fishing and

slash-and-burn

Slash-and-burn agriculture is a farming method that involves the cutting and burning of plants in a forest or woodland to create a field called a swidden. The method begins by cutting down the trees and woody plants in an area. The downed veget ...

agriculture.

At the end of the 15th century, western Nicaragua was inhabited by several indigenous peoples related by culture to the Mesoamerican civilizations of the

Aztec

The Aztecs () were a Mesoamerican culture that flourished in central Mexico in the post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the Nahuatl ...

and

Maya

Maya may refer to:

Civilizations

* Maya peoples, of southern Mexico and northern Central America

** Maya civilization, the historical civilization of the Maya peoples

** Maya language, the languages of the Maya peoples

* Maya (Ethiopia), a popul ...

, and by language to the

Mesoamerican language area The Mesoamerican language area is a ''sprachbund'' containing many of the languages natively spoken in the cultural area of Mesoamerica. This sprachbund is defined by an array of syntactic, lexical and phonological traits as well as a number of ethn ...

.

[, interpretation of statement: "the native peoples were linguistically and culturally similar to the Aztec and the Maya"] The Chorotegas were

Mangue language ethnic groups who had arrived in Nicaragua from what is now the Mexican state of

Chiapas

Chiapas (; Tzotzil and Tzeltal: ''Chyapas'' ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Chiapas ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Chiapas), is one of the states that make up the 32 federal entities of Mexico. It comprises 124 municipalities ...

sometime around 800 CE.

The

Nicarao people

The Nicarao people were a Nahuat-speaking Mesoamerican people who migrated from central and southern Mexico over the course of several centuries from approximately 700 CE onwards. Around 1200 CE, the Nicarao split from the Pipil people and moved ...

were a branch of

Nahuas

The Nahuas () are a group of the indigenous people of Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua. They comprise the largest indigenous group in Mexico and second largest in El Salvador. The Mexica (Aztecs) were of Nahua ethnicity, a ...

who spoke the

Nawat

Nawat (academically Pipil, also known as Nicarao) is a Nahuan language native to Central America. It is the southernmost extant member of the Uto-Aztecan family. It was spoken in several parts of present-day Central America before the Spanish c ...

dialect and also came from Chiapas, around 1200 CE.

Prior to that, the Nicaraos had been associated with the

Toltec

The Toltec culture () was a pre-Columbian Mesoamerican culture that ruled a state centered in Tula, Hidalgo, Mexico, during the Epiclassic and the early Post-Classic period of Mesoamerican chronology, reaching prominence from 950 to 1150 CE. T ...

civilization.

Both Chorotegas and Nicaraos originated in Mexico's

Cholula valley,

and migrated south.

A third group, the

Subtiabas, were an

Oto-Manguean

The Oto-Manguean or Otomanguean languages are a large family comprising several subfamilies of indigenous languages of the Americas. All of the Oto-Manguean languages that are now spoken are indigenous to Mexico, but the Manguean branch of the ...

people who migrated from the Mexican state of

Guerrero

Guerrero is one of the 32 states that comprise the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided in 81 municipalities and its capital city is Chilpancingo and its largest city is Acapulcocopied from article, GuerreroAs of 2020, Guerrero the pop ...

around 1200 CE.

Additionally, there were trade-related colonies in Nicaragua set up by the Aztecs starting in the 14th century.

Spanish era (1523ŌĆō1821)

In 1502, on his fourth voyage,

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Crist├│bal Col├│n

* pt, Crist├│v├Żo Colombo

* ca, Crist├▓for (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

became the first European known to have reached what is now Nicaragua as he sailed southeast toward the

Isthmus of Panama

The Isthmus of Panama ( es, Istmo de Panam├Ī), also historically known as the Isthmus of Darien (), is the narrow strip of land that lies between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, linking North and South America. It contains the country ...

.

Columbus explored the

Mosquito Coast on the Atlantic side of Nicaragua but did not encounter any indigenous people. 20 years later, the Spaniards returned to Nicaragua, this time to its southwestern part. The first attempt to conquer Nicaragua was by the conquistador

Gil Gonz├Īlez D├Īvila

Gil Gonz├Īlez D├Īvila or Gil Gonz├Īlez de ├üvila (b. 1480 ŌĆō 21 April 1526) was a Spanish conquistador and the first European to explore present-day Nicaragua.

Early career

Gonz├Īlez D├Īvila first appears in historical records in 1508, when he ...

,

who had arrived in Panama in January 1520. In 1522, Gonz├Īlez D├Īvila ventured to the area that later became the

Rivas Department

Rivas () is a department of the Republic of Nicaragua. It covers an area of 2,162 km2 and has a population of 183,611 (2021 estimate). The department's capital is the city of Rivas.

Overview

Rivas is known for its fertile soil and beautif ...

of Nicaragua.

There he encountered an indigenous Nahua tribe led by chief Macuilmiquiztli, whose name has sometimes been erroneously referred to as "

Nicarao" or "Nicaragua". The tribe's capital was Quauhcapolca.

Gonz├Īlez D├Īvila conversed with Macuilmiquiztli thanks to two indigenous interpreters who had learned Spanish, whom he had brought along.

After exploring and gathering gold

in the fertile western valleys, Gonz├Īlez D├Īvila and his men were attacked and driven off by the Chorotega, led by chief

Diriang├®n.

The Spanish tried to convert the tribes to Christianity; Macuilmiquiztli's tribe was baptized,

but Diriang├®n was openly hostile to the Spaniards. Western Nicaragua, at the Pacific Coast, became a port and shipbuilding facility for the Galleons plying the waters between Manila, Philippines and Acapulco, Mexico.

The first Spanish permanent settlements were founded in 1524.

[ That year, the conquistador Francisco Hern├Īndez de C├│rdoba founded two of Nicaragua's main cities: ]Granada

Granada (,, DIN: ; grc, ß╝ś╬╗╬╣╬▓ŽŹŽü╬│╬Ę, Elib├Įrg─ō; la, Illiberis or . ) is the capital city of the province of Granada, in the autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada mountains, at the c ...

on Lake Nicaragua

Lake Nicaragua or Cocibolca or Granada ( es, Lago de Nicaragua, , or ) is a freshwater lake in Nicaragua. Of tectonic origin and with an area of , it is the largest lake in Central America, the 19th largest lake in the world (by area) and the t ...

, and then Le├│n, west of Lake Managua

Lake Managua ( es, Lago de Managua, ), also known as Lake Xolotl├Īn (), is a lake in Nicaragua. At 1,042 km┬▓, it is approximately long and wide. Similarly to the name of Lake Nicaragua, its other name comes from the Nahuatl language, possi ...

.beheaded

Decapitation or beheading is the total separation of the head from the body. Such an injury is invariably fatal to humans and most other animals, since it deprives the brain of oxygenated blood, while all other organs are deprived of the au ...

for having defied his superior, Pedro Arias D├Īvila

Pedro Arias de ├üvila (1440 ŌĆō March 6, 1531) (often Pedrarias D├Īvila) was a Spanish soldier and colonial administrator. He led the first great Spanish expedition to the mainland of the New World. There he served as governor of Panama (1514ŌĆ ...

.[

Without women in their parties,]mestizo

(; ; fem. ) is a term used for racial classification to refer to a person of mixed European and Indigenous American ancestry. In certain regions such as Latin America, it may also refer to people who are culturally European even though thei ...

''", which constitutes the great majority of the population in western Nicaragua.[ Many indigenous people were killed by European ]infectious disease

An infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable di ...

s, compounded by neglect by the Spaniards, who controlled their subsistence.[ Many other indigenous peoples were captured and transported as slaves to Panama and Peru between 1526 and 1540.]Momotombo

Momotombo is a stratovolcano in Nicaragua, not far from the city of Le├│n. It stands on the shores of Lago de Managua. An eruption of the volcano in 1610 forced inhabitants of the Spanish city of Le├│n to relocate about west. The ruins of th ...

volcano erupted, destroying the city of Le├│n.American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 ŌĆō September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, Central America was subject to conflict between Britain and Spain. British navy admiral Horatio Nelson

Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte (29 September 1758 ŌĆō 21 October 1805) was a British flag officer in the Royal Navy. His inspirational leadership, grasp of strategy, and unconventional tactics brought a ...

led expeditions in the Battle of San Fernando de Omoa

The Battle of San Fernando de Omoa was a short siege and battle between British and Spanish forces fought not long after Spain entered the American Revolutionary War on the American side. On the 16 October 1779, following a brief attempt at siege ...

in 1779 and on the San Juan River in 1780, the latter of which had temporary success before being abandoned due to disease.

Independent Nicaragua from 1821 to 1909

The

The Act of Independence of Central America

The Act of Independence of Central America ( es, Acta de Independencia Centroamericana), also known as the Act of Independence of Guatemala, is the legal document by which the Provincial Council of the Province of Guatemala proclaimed the indepen ...

dissolved the Captaincy General of Guatemala

The Captaincy General of Guatemala ( es, Capitan├Ła General de Guatemala), also known as the Kingdom of Guatemala ( es, Reino de Guatemala), was an administrative division of the Spanish Empire, under the viceroyalty of New Spain in Central ...

in September 1821, and Nicaragua soon became part of the First Mexican Empire

The Mexican Empire ( es, Imperio Mexicano, ) was a constitutional monarchy, the first independent government of Mexico and the only former colony of the Spanish Empire to establish a monarchy after independence. It is one of the few modern-era ...

. In July 1823, after the overthrow of the Mexican monarchy in March of the same year, Nicaragua joined the newly formed United Provinces of Central America

The Federal Republic of Central America ( es, Rep├║blica Federal de Centroam├®rica), originally named the United Provinces of Central America ( es, Provincias Unidas del Centro de Am├®rica), and sometimes simply called Central America, in it ...

, country later known as the Federal Republic of Central America. Nicaragua definitively became an independent republic in 1838.

The early years of independence were characterized by rivalry between the Liberal elite of Le├│n and the Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

elite of Granada, which often degenerated into civil war, particularly during the 1840s and 1850s. Managua

)

, settlement_type = Capital city

, motto =

, image_map =

, mapsize =

, map_caption =

, pushpin_map = Nicar ...

rose to undisputed preeminence as the nation's capital in 1852 to allay the rivalry between the two feuding cities.California Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush (1848ŌĆō1855) was a gold rush that began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California f ...

, Nicaragua provided a route for travelers from the eastern United States to journey to California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

by sea, via the San Juan River and Lake Nicaragua.filibuster

A filibuster is a political procedure in which one or more members of a legislative body prolong debate on proposed legislation so as to delay or entirely prevent decision. It is sometimes referred to as "talking a bill to death" or "talking out ...

William Walker set himself up as President of Nicaragua

The president of Nicaragua ( es, Presidente de Nicaragua), officially known as the president of the Republic of Nicaragua ( es, Presidente de la Rep├║blica de Nicaragua), is the head of state and head of government of Nicaragua. The office was ...

after conducting a farcical election in 1856; his presidency lasted less than a year.protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over most of its in ...

since 1655, delegated the area to Honduras in 1859 before transferring it to Nicaragua in 1860. The Mosquito Coast remained an autonomous area

In developmental psychology and moral, political, and bioethical philosophy, autonomy, from , ''autonomos'', from ╬▒ßĮÉŽä╬┐- ''auto-'' "self" and ╬ĮŽī╬╝╬┐Žé ''nomos'', "law", hence when combined understood to mean "one who gives oneself one's ...

until 1894. Jos├® Santos Zelaya, President of Nicaragua from 1893 to 1909, negotiated the integration of the Mosquito Coast into Nicaragua. In his honor, the region became "Zelaya Department

Zelaya is a former department in Nicaragua. The department was located along the Mosquito Coast bordering the Caribbean Sea and was named after former President of Nicaragua Jos├® Santos Zelaya, who conquered the region for Nicaragua from t ...

".

Throughout the late 19th-century, the United States and several European powers considered various schemes to link the Pacific Ocean to the Atlantic by building a canal across Nicaragua.

United States occupation (1909ŌĆō1933)

In 1909, the United States supported the conservative-led forces rebelling against President Zelaya. U.S. motives included differences over the proposed Nicaragua Canal

The Nicaraguan Canal ( es, Canal de Nicaragua), formally the Nicaraguan Canal and Development Project (also referred to as the Nicaragua Grand Canal, or the Grand Interoceanic Canal) was a proposed shipping route through Nicaragua to connect t ...

, Nicaragua's potential to destabilize the region, and Zelaya's attempts to regulate foreign access to Nicaraguan natural resources. On November 18, 1909, U.S. warships were sent to the area after 500 revolutionaries (including two Americans) were executed by order of Zelaya. The U.S. justified the intervention by claiming to protect U.S. lives and property. Zelaya resigned later that year.

In August 1912, the President of Nicaragua, Adolfo D├Łaz

Adolfo D├Łaz Recinos (15 July 1875 in Alajuela, Costa Rica ŌĆō 29 January 1964 in San Jos├®, Costa Rica) served as the President of Nicaragua between 9 May 1911 and 1 January 1917 and again between 14 November 1926 and 1 January 1929. Born in C ...

, requested the secretary of war, General Luis Mena, to resign for fear he was leading an insurrection. Mena fled Managua with his brother, the chief of police of Managua, to start an insurrection. After Mena's troops captured steam boats of an American company, the U.S. delegation asked President D├Łaz to ensure the safety of American citizens and property during the insurrection. He replied he could not, and asked the U.S. to intervene in the conflict.

U.S. Marines occupied Nicaragua from 1912 to 1933,Augusto C├®sar Sandino

Augusto C. Sandino (; May 18, 1895 February 21, 1934), full name Augusto Nicol├Īs Calder├│n de Sandino y Jos├® de Mar├Ła Sandino, was a Nicaraguan revolutionary and leader of a rebellion between 1927 and 1933 against the United States occupat ...

led a sustained guerrilla war against the Conservative regime and then against the U.S. Marines, whom he fought for over five years. When the Americans left in 1933, they set up the '' Guardia Nacional'' (national guard),Juan Bautista Sacasa

Juan Bautista Sacasa (21 December 1874 in Le├│n, Nicaragua ŌĆō 17 April 1946 in Los Angeles, California) was the President of Nicaragua from 1 January 1933 to 9 June 1936. He was the eldest son of Roberto Sacasa and ├üngela Sacasa Cuadra, the for ...

reached an agreement that Sandino would cease his guerrilla activities in return for amnesty, a land grant for an agricultural colony, and retention of an armed band of 100 men for a year. However, due to a growing hostility between Sandino and National Guard director Anastasio Somoza Garc├Ła

Anastasio Somoza Garc├Ła (1 February 1896 ŌĆō 29 September 1956) was the leader of Nicaragua from 1937 until his assassination in 1956. He was only officially the 21st President of Nicaragua from 1 January 1937 to 1 May 1947 and from 21 May 195 ...

and a fear of armed opposition from Sandino, Somoza Garc├Ła ordered his assassination.[ Sacasa invited Sandino for dinner and to sign a peace treaty at the Presidential House on the night of February 21, 1934. After leaving the Presidential House, Sandino's car was stopped by National Guard soldiers and they kidnapped him. Later that night, Sandino was assassinated by National Guard soldiers. Later, hundreds of men, women, and children from Sandino's agricultural colony were murdered.]

Somoza dynasty (1927ŌĆō1979)

Nicaragua has experienced several military dictatorships, the longest being the hereditary dictatorship of the

Nicaragua has experienced several military dictatorships, the longest being the hereditary dictatorship of the Somoza family

The Somoza family ( es, Familia Somoza) is a former political family that ruled Nicaragua for forty-three years from 1936 to 1979. Their family dictatorship was founded by Anastasio Somoza Garc├Ła and was continued by his two sons Luis Somoza ...

, who ruled for 43 nonconsecutive years during the 20th century. The Somoza family came to power as part of a U.S.-engineered pact in 1927 that stipulated the formation of the ''Guardia Nacional'' to replace the marines who had long reigned in the country. Somoza Garc├Ła slowly eliminated officers in the national guard who might have stood in his way, and then deposed Sacasa and became president on January 1, 1937, in a rigged election.[

In 1941, during the Second World War, Nicaragua declared war on ]Japan

Japan ( ja, µŚźµ£¼, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

(8 December), Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

(11 December), Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

(11 December), Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, ąæčŖą╗ą│ą░čĆąĖčÅ, BŪÄlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

(19 December), Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarorsz├Īg ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Cr ...

(19 December) and Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

(19 December). Only Romania reciprocated, declaring war on Nicaragua on the same day (19 December 1941). No soldiers were sent to the war, but Somoza Garc├Ła confiscated properties held by German Nicaraguan

German Nicaraguan is a Nicaraguan having German ancestry, or a German-born naturalized citizen of Nicaragua. This includes Poles due to the Partitions of Poland and Sudeten Germans from present Czech Republic. During the Second World War, afte ...

residents. In 1945, Nicaragua was among the first countries to ratify the United Nations Charter.

On September 29, 1956, Somoza Garc├Ła was shot to death by

On September 29, 1956, Somoza Garc├Ła was shot to death by Rigoberto L├│pez P├®rez

Rigoberto L├│pez P├®rez (May 13, 1929 ŌĆō September 21, 1956) was a Nicaraguan poet, artist and composer. He assassinated Anastasio Somoza Garc├Ła, the longtime dictator of Nicaragua.

On September 21, 1981, 25 years after his death, the Sandin ...

, a 27-year-old Liberal Nicaraguan poet. Luis Somoza Debayle

Luis Anastasio Somoza Debayle (18 November 1922 ŌĆō 13 April 1967) was the 26th President of Nicaragua from 21 September 1956 to 1 May 1963.

Somoza Debayle was born in Le├│n. At the age of 14, he and his younger brother Anastasio attended ...

, the eldest son of the late president, was appointed president by the congress and officially took charge of the country.[ He is remembered by some as moderate, but after only a few years in power died of a heart attack. His successor as president was ]Ren├® Schick Guti├®rrez

Ren├® (''born again'' or ''reborn'' in French) is a common first name in French-speaking, Spanish-speaking, and German-speaking countries. It derives from the Latin name Renatus.

Ren├® is the masculine form of the name ( Ren├®e being the feminin ...

, whom most Nicaraguans viewed "as nothing more than a puppet of the Somozas". Somoza Garc├Ła's youngest son, Anastasio Somoza Debayle

Anastasio "Tachito" Somoza Debayle (; 5 December 1925 ŌĆō 17 September 1980) was the President of Nicaragua from 1 May 1967 to 1 May 1972 and from 1 December 1974 to 17 July 1979. As head of the National Guard, he was ''de facto'' ruler of t ...

, often referred to simply as "Somoza", became president in 1967.

An earthquake in 1972 destroyed nearly 90% of Managua, including much of its infrastructure. Instead of helping to rebuild the city, Somoza siphoned off relief money. The mishandling of relief money also prompted Pittsburgh Pirates

The Pittsburgh Pirates are an American professional baseball team based in Pittsburgh. The Pirates compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the National League (NL) Central division. Founded as part of the American Associati ...

star Roberto Clemente

Roberto Enrique Clemente Walker (; August 18, 1934 ŌĆō December 31, 1972) was a Puerto Rican professional baseball right fielder who played 18 seasons in Major League Baseball (MLB) for the Pittsburgh Pirates. After his early death, he was pos ...

to personally fly to Managua on December 31, 1972, but he died ''en route'' in an airplane accident. Even the economic elite were reluctant to support Somoza, as he had acquired monopolies in industries that were key to rebuilding the nation.

The Somoza family was among a few families or groups of influential firms which reaped most of the benefits of the country's growth from the 1950s to the 1970s. When Somoza was deposed by the Sandinistas in 1979, the family's worth was estimated to be between $500 million and $1.5 billion.

Nicaraguan Revolution (1960sŌĆō1990)

In 1961,

In 1961, Carlos Fonseca

Carlos Fonseca Amador (23 June 1936 ŌĆō 8 November 1976) was a Nicaraguan teacher, librarian and revolutionary who founded the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN). Fonseca was later killed in the mountains of the Zelaya Department, Nicar ...

looked back to the historical figure of Sandino, and along with two other people (one of whom was believed to be Casimiro Sotelo, who was later assassinated), founded the Sandinista National Liberation Front

The Sandinista National Liberation Front ( es, Frente Sandinista de Liberaci├│n Nacional, FSLN) is a socialist political party in Nicaragua. Its members are called Sandinistas () in both English and Spanish. The party is named after Augusto ...

(FSLN).[ After the 1972 earthquake and Somoza's apparent corruption, the ranks of the Sandinistas were flooded with young disaffected Nicaraguans who no longer had anything to lose.]Pedro Joaqu├Łn Chamorro Cardenal

Pedro Joaqu├Łn Chamorro Cardenal (23 September 1924 ŌĆō 10 January 1978) was a Nicaraguan journalist and publisher. He was the editor of '' La Prensa'', the only significant opposition newspaper to the long rule of the Somoza family. He is a 1 ...

, the editor of the national newspaper ''La Prensa ''La Prensa'' ("The Press") is a frequently used name for newspapers in the Spanish-speaking world. It may refer to:

Argentina

* ''La Prensa'' (Buenos Aires)

* , a current publication of Caleta Olivia, Santa Cruz

Bolivia

* ''La Prensa'' (La Paz ...

'' and ardent opponent of Somoza, was assassinated.[

The Sandinistas forcefully took power in July 1979, ousting Somoza, and prompting the exodus of the majority of Nicaragua's middle class, wealthy landowners, and professionals, many of whom settled in the United States. The Carter administration decided to work with the new government, while attaching a provision for aid forfeiture if it was found to be assisting insurgencies in neighboring countries. Somoza fled the country and eventually ended up in ]Paraguay

Paraguay (; ), officially the Republic of Paraguay ( es, Rep├║blica del Paraguay, links=no; gn, Tavakuairet├Ż Paragu├Īi, links=si), is a landlocked country in South America. It is bordered by Argentina to the south and southwest, Brazil to t ...

, where he was assassinated in September 1980, allegedly by members of the Argentinian Revolutionary Workers' Party

Argentines (mistakenly translated Argentineans in the past; in Spanish (masculine) or ( feminine)) are people identified with the country of Argentina. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Argentines, ...

.

In 1980, the Carter administration provided $60 million in aid to Nicaragua under the Sandinistas, but the aid was suspended when the administration obtained evidence of Nicaraguan shipment of arms to El Salvadoran rebels. Most people sided with Nicaragua against the Sandinistas. In response to the coming to power of the Sandinistas, various rebel groups collectively known as the "Contras

The Contras were the various U.S.-backed and funded right-wing rebel groups that were active from 1979 to 1990 in opposition to the Marxist Sandinista Junta of National Reconstruction Government in Nicaragua, which came to power in 1979 foll ...

" were formed to oppose the new government. The Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

administration authorized the CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

to help the Contra rebels with funding, weapons and training.[

] They engaged in a systematic campaign of terror among rural Nicaraguans to disrupt the social reform projects of the Sandinistas. Several historians have criticized the Contra campaign and the Reagan administration's support for the Contras, citing the brutality and numerous human rights violations of the Contras. LaRamee and Polakoff, for example, describe the destruction of health centers, schools, and cooperatives at the hands of the rebels, and others have contended that murder, rape, and torture occurred on a large scale in Contra-dominated areas. The U.S. also carried out a campaign of economic sabotage, and disrupted shipping by planting underwater mines in Nicaragua's port of Corinto, an action condemned by the

They engaged in a systematic campaign of terror among rural Nicaraguans to disrupt the social reform projects of the Sandinistas. Several historians have criticized the Contra campaign and the Reagan administration's support for the Contras, citing the brutality and numerous human rights violations of the Contras. LaRamee and Polakoff, for example, describe the destruction of health centers, schools, and cooperatives at the hands of the rebels, and others have contended that murder, rape, and torture occurred on a large scale in Contra-dominated areas. The U.S. also carried out a campaign of economic sabotage, and disrupted shipping by planting underwater mines in Nicaragua's port of Corinto, an action condemned by the International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; french: Cour internationale de justice, links=no; ), sometimes known as the World Court, is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN). It settles disputes between states in accordan ...

as illegal. The court also found that the U.S. encouraged acts contrary to humanitarian law by producing the manual '' Psychological Operations in Guerrilla Warfare'' and disseminating it to the Contras. The manual, among other things, advised on how to rationalize killings of civilians.["In the case of shooting "a citizen who was trying to leave the town or city in which the guerrillas are carrying out armed propaganda or political proselytism," the manual suggests that the Contras "...explain that if that citizen had managed to escape, he would have alerted the enemy." As seen at: Sklar 1988, p. 179] The U.S. also sought to place economic pressure on the Sandinistas, and the Reagan administration imposed a full trade embargo.

The Sandinistas were also accused of human rights abuses including torture, disappearances and mass executions. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (the IACHR or, in the three other official languages Spanish, French, and Portuguese CIDH, ''Comisi├│n Interamericana de los Derechos Humanos'', ''Commission Interam├®ricaine des Droits de l'Homme'' ...

investigated abuses by Sandinista forces, including an execution of 35 to 40 Miskitos in December 1981, and an execution of 75 people in November 1984.

In the Nicaraguan general elections of 1984, which were judged by at least one visiting 30-person delegation of NGO representatives to have been free and fair, the Sandinistas won the parliamentary election and their leader Daniel Ortega

Jos├® Daniel Ortega Saavedra (; born 11 November 1945) is a Nicaraguan revolutionary and politician serving as President of Nicaragua since 2007. Previously he was leader of Nicaragua from 1979 to 1990, first as coordinator of the Junta of Na ...

won the presidential election. The Reagan administration criticized the elections as a "sham" based on the claim that Arturo Cruz

Arturo Jos├® Cruz Porras (December 18, 1923 ŌĆō July 9, 2013), sometimes called Arturo Cruz Sr. to distinguish him from his son, was a Nicaraguan banker and technocrat. He became prominent in politics during the Sandinista (FSLN) era. After repeate ...

, the candidate nominated by the Coordinadora Democr├Ītica Nicarag├╝ense, comprising three right wing political parties, did not participate in the elections. However, the administration privately argued against Cruz's participation for fear that his involvement would legitimize the elections, and thus weaken the case for American aid to the Contras. According to Martin Kriele, the results of the election were rigged.

In 1983 the U.S. Congress prohibited federal funding of the Contras, but the Reagan administration illegally continued to back them by covertly selling arms to Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

and channeling the proceeds to the Contras in the IranŌĆōContra affair

The IranŌĆōContra affair ( fa, ┘ģž¦ž¼ž▒ž¦█ī ž¦█īž▒ž¦┘å-┌®┘垬ž▒ž¦, es, Caso Ir├ĪnŌĆōContra), often referred to as the IranŌĆōContra scandal, the McFarlane affair (in Iran), or simply IranŌĆōContra, was a political scandal in the United States ...

, for which several members of the Reagan administration were convicted of felonies. The International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; french: Cour internationale de justice, links=no; ), sometimes known as the World Court, is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN). It settles disputes between states in accordan ...

, in regard to the case of Nicaragua v. United States in 1986, found, "the United States of America was under an obligation to make reparation to the Republic of Nicaragua for all injury caused to Nicaragua by certain breaches of obligations under customary international law and treaty-law committed by the United States of America".

Post-war (1990ŌĆōpresent)

In the

In the Nicaraguan general election, 1990

General elections were held in Nicaragua on 25 February 1990 to elect the President and the members of the National Assembly. Dieter Nohlen (2005) ''Elections in the Americas: A data handbook, Volume I'', p489 The result was a victory for the ...

, a coalition of anti-Sandinista parties (from the left and right of the political spectrum) led by Violeta Chamorro

Violeta Barrios Torres de Chamorro (; 18 October 1929) is a Nicaraguan politician who served as President of Nicaragua from 1990 to 1997. She was the first and, as of 2022, only woman to hold the position of president of Nicaragua.

Born into ...

, the widow of Pedro Joaqu├Łn Chamorro Cardenal, defeated the Sandinistas. The defeat shocked the Sandinistas, who had expected to win.

Exit polls of Nicaraguans reported Chamorro's victory over Ortega was achieved with a 55% majority. Chamorro was the first woman president of Nicaragua. Ortega vowed he would govern ''desde abajo'' (from below). Chamorro came to office with an economy in ruins, primarily because of the financial and social costs of the Contra War with the Sandinista-led government. In the next election, the Nicaraguan general election, 1996

General elections were held in Nicaragua on 20 October 1996 to elect the President and the members of the National Assembly.Dieter Nohlen (2005) ''Elections in the Americas: A data handbook, Volume I'', p489 Arnoldo Alem├Īn of the Liberal Alli ...

, Daniel Ortega and the Sandinistas of the FSLN lost again, this time to Arnoldo Alem├Īn

Jos├® Arnoldo Alem├Īn Lacayo (born 23 January 1946) is a Nicaraguan politician who served as the 81st president of Nicaragua from 10 January 1997 to 10 January 2002. In 2003, he was convicted of corruption and sentenced to a 20-year prison term; ...

of the Constitutional Liberal Party

The Constitutionalist Liberal Party ( es, Partido Liberal Constitucionalista, PLC) is a political party in Nicaragua. At the Nicaraguan general election of 5 November 2006, the party won 25 of 92 seats in the National Assembly. However, the pa ...

(PLC).

In the 2001 elections, the PLC again defeated the FSLN, with Alem├Īn's Vice President

In the 2001 elections, the PLC again defeated the FSLN, with Alem├Īn's Vice President Enrique Bola├▒os

Enrique Jos├® Bola├▒os Geyer (; 13 May 1928 ŌĆō 14 June 2021) was a Nicaraguan politician who served as President of Nicaragua from 10 January 2002 to 10 January 2007.

From 1997 to 2002, Bola├▒os served as vice president under Arnoldo Alem├Īn ...

succeeding him as president. However, Alem├Īn was convicted and sentenced in 2003 to 20 years in prison for embezzlement

Embezzlement is a crime that consists of withholding assets for the purpose of conversion of such assets, by one or more persons to whom the assets were entrusted, either to be held or to be used for specific purposes. Embezzlement is a type ...

, money laundering

Money laundering is the process of concealing the origin of money, obtained from illicit activities such as drug trafficking, corruption, embezzlement or gambling, by converting it into a legitimate source. It is a crime in many jurisdicti ...

, and corruption; liberal and Sandinista parliament members combined to strip the presidential powers of President Bola├▒os and his ministers, calling for his resignation and threatening impeachment

Impeachment is the process by which a legislative body or other legally constituted tribunal initiates charges against a public official for misconduct. It may be understood as a unique process involving both political and legal elements.

In ...

. The Sandinistas said they no longer supported Bola├▒os after U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell

Colin Luther Powell ( ; April 5, 1937 ŌĆō October 18, 2021) was an American politician, statesman, diplomat, and United States Army officer who served as the 65th United States Secretary of State from 2001 to 2005. He was the first Africa ...

told Bola├▒os to distance from the FSLN. This "slow motion ''coup d'├®tat''" was averted partially by pressure from the Central American presidents, who vowed not to recognize any movement that removed Bola├▒os; the U.S., the OAS, and the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are located primarily in Europe, Europe. The union has a total area of ...

also opposed the action.

Before the general elections on November 5, 2006, the National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the r ...

passed a bill further restricting abortion in Nicaragua. As a result, Nicaragua is one of five countries in the world where abortion is illegal with no exceptions. Legislative and presidential elections took place on November 5, 2006. Ortega returned to the presidency with 37.99% of the vote. This percentage was enough to win the presidency outright, because of a change in electoral law which lowered the percentage requiring a runoff election from 45% to 35% (with a 5% margin of victory). Nicaragua's 2011 general election resulted in re-election of Ortega, with a landslide victory and 62.46% of the vote. In 2014 the National Assembly approved changes to the constitution allowing Ortega to run for a third successive term.

In November 2016, Ortega was elected for his third consecutive term (his fourth overall). International monitoring of the elections was initially prohibited, and as a result the validity of the elections

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has opera ...

has been disputed, but observation by the OAS was announced in October. Ortega was reported by Nicaraguan election officials as having received 72% of the vote. However the Broad Front for Democracy

The Broad Front for Democracy ( es, link=no, Frente Amplio por la Democracia) was a Panamanian political party originally founded in 2013.

At the 2014 Panamanian general election, the candidate's party was Genaro L├│pez for the Presidency

A pre ...

(FAD), having promoted boycotts of the elections, claimed that 70% of voters had abstained (while election officials claimed 65.8% participation).

In April 2018, demonstrations

Demonstration may refer to:

* Demonstration (acting), part of the Brechtian approach to acting

* Demonstration (military), an attack or show of force on a front where a decision is not sought

* Demonstration (political), a political rally or prote ...

opposed a decree increasing taxes and reducing benefits in the country's pension system. Local independent press organizations had documented at least 19 dead and over 100 missing in the ensuing conflict. A reporter from NPR spoke to protestors who explained that while the initial issue was about the pension reform, the uprisings that spread across the country reflected many grievances about the government's time in office, and that the fight is for President Ortega and his vice president wife to step down. April 24, 2018 marked the day of the greatest march in opposition of the Sandinista party. On May 2, 2018, university-student leaders publicly announced that they give the government seven days to set a date and time for a dialogue that was promised to the people due to the recent events of repression. The students also scheduled another march on that same day for a peaceful protest. As of May 2018, estimates of the death toll were as high as 63, many of them student protesters, and the wounded totalled more than 400. Following a working visit from May 17 to 21, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights adopted precautionary measures aimed at protecting members of the student movement and their families after testimonies indicated the majority of them had suffered acts of violence and death threats for their participation. In the last week of May, thousands who accuse Mr. Ortega and his wife of acting like dictators joined in resuming anti-government rallies after attempted peace talks have remained unresolved.

Geography and climate

Nicaragua occupies a landmass of , which makes it slightly larger than England. Nicaragua has three distinct geographical regions: the Pacific lowlands ŌĆō fertile valleys which the Spanish colonists settled, the

Nicaragua occupies a landmass of , which makes it slightly larger than England. Nicaragua has three distinct geographical regions: the Pacific lowlands ŌĆō fertile valleys which the Spanish colonists settled, the Amerrisque Mountains

The Amerrisque Mountains ( es, Serran├Łas de Amerrisque, Cordillera de Amerrisque, links=no) are the central spine of Nicaragua and part of the Central American Range which extends throughout central Nicaragua for about from Honduras in the nor ...

(North-central highlands), and the Mosquito Coast (Atlantic lowlands/Caribbean lowlands

The Caribbean Lowlands are a plains region along eastern areas of Central American nations. The area is usually between mountain ranges and the coastlines of the Caribbean Sea.

Geography

The lowlands are mainly between the major American Cordille ...

).

The low plains of the Atlantic Coast are wide in areas. They have long been exploited for their natural resources.

On the Pacific side of Nicaragua are the two largest fresh water lakes in Central AmericaŌĆöLake Managua

Lake Managua ( es, Lago de Managua, ), also known as Lake Xolotl├Īn (), is a lake in Nicaragua. At 1,042 km┬▓, it is approximately long and wide. Similarly to the name of Lake Nicaragua, its other name comes from the Nahuatl language, possi ...

and Lake Nicaragua

Lake Nicaragua or Cocibolca or Granada ( es, Lago de Nicaragua, , or ) is a freshwater lake in Nicaragua. Of tectonic origin and with an area of , it is the largest lake in Central America, the 19th largest lake in the world (by area) and the t ...

. Surrounding these lakes and extending to their northwest along the rift valley

A rift valley is a linear shaped lowland between several highlands or mountain ranges created by the action of a geologic rift. Rifts are formed as a result of the pulling apart of the lithosphere due to extensional tectonics. The linear d ...

of the Gulf of Fonseca

The Gulf of Fonseca ( es, Golfo de Fonseca; ), a part of the Pacific Ocean, is a gulf in Central America, bordering El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua.

History

Fonseca Bay was discovered for Europeans in 1522 by Gil Gonz├Īlez de ├üv ...

are fertile lowland plains, with soil highly enriched by ash

Ash or ashes are the solid remnants of fires. Specifically, ''ash'' refers to all non-aqueous, non-gaseous residues that remain after something burns. In analytical chemistry, to analyse the mineral and metal content of chemical samples, ash ...

from nearby volcano

A volcano is a rupture in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often found where tectonic plates ...

es of the central highlands. Nicaragua's abundance of biologically significant and unique ecosystem

An ecosystem (or ecological system) consists of all the organisms and the physical environment with which they interact. These biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and energy flows. Energy enters the syst ...

s contribute to Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area in southern North America and most of Central America. It extends from approximately central Mexico through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica. Wit ...

's designation as a biodiversity hotspot

A biodiversity hotspot is a biogeographic region with significant levels of biodiversity that is threatened by human habitation. Norman Myers wrote about the concept in two articles in ''The Environmentalist'' in 1988 and 1990, after which the c ...

. Nicaragua has made efforts to become less dependent on fossil fuels, and it expects to acquire 90% of its energy from renewable resources by 2020.COP21

The 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference, COP 21 or CMP 11 was held in Paris, France, from 30 November to 12 December 2015. It was the 21st yearly session of the Conference of the Parties (COP) to the 1992 United Nations Framework Conve ...

. Nicaragua initially chose not to join the Paris Climate Accord because it felt that "much more action is required" by individual countries on restricting global temperature rise.protected areas

Protected areas or conservation areas are locations which receive protection because of their recognized natural, ecological or cultural values. There are several kinds of protected areas, which vary by level of protection depending on the ena ...

like national parks, nature reserves, and biological reserves. The country had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index

The Forest Landscape Integrity Index (FLII) is an annual global index of forest condition measured by degree of anthropogenic modification. Created by a team of 48 scientists, the FLII, in its measurement of 300m pixels of forest across the globe ...

mean score of 3.63/10, ranking it 146th globally out of 172 countries.Geophysical

Geophysics () is a subject of natural science concerned with the physical processes and physical properties of the Earth and its surrounding space environment, and the use of quantitative methods for their analysis. The term ''geophysics'' some ...

ly, Nicaragua is surrounded by the Caribbean Plate

The Caribbean Plate is a mostly oceanic tectonic plate underlying Central America and the Caribbean Sea off the north coast of South America.

Roughly 3.2 million square kilometers (1.2 million square miles) in area, the Caribbean Plate border ...

, an oceanic tectonic plate

Plate tectonics (from the la, label=Late Latin, tectonicus, from the grc, Žä╬Ą╬║Žä╬┐╬Į╬╣╬║ŽīŽé, lit=pertaining to building) is the generally accepted scientific theory that considers the Earth's lithosphere to comprise a number of large te ...

underlying Central America and the Cocos Plate

The Cocos Plate is a young oceanic tectonic plate beneath the Pacific Ocean off the west coast of Central America, named for Cocos Island, which rides upon it. The Cocos Plate was created approximately 23 million years ago when the Farallon Plat ...

. Since Central America is a major subduction

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, ...

zone, Nicaragua hosts most of the Central American Volcanic Arc

The Central American Volcanic Arc (often abbreviated to CAVA) is a chain of volcanoes which extends parallel to the Pacific coastline of the Central American Isthmus, from Mexico to Panama. This volcanic arc, which has a length of 1,100 kilom ...

. On 9 June 2021, Nicaragua launched a new volcanic supersite research in strengthening the monitoring and surveillance of the country's 21 active volcanoes.

Pacific lowlands

In the west of the country, these lowlands consist of a broad, hot, fertile plain. Punctuating this plain are several large volcanoes of the

In the west of the country, these lowlands consist of a broad, hot, fertile plain. Punctuating this plain are several large volcanoes of the Cordillera Los Maribios

Cordillera de Maribios (or Cordillera de Marrabios) is a mountain range in Le├│n and Chinandega departments, western Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by ...

mountain range, including Mombacho

Mombacho is a stratovolcano in Nicaragua, near the city of Granada. It is high. The Mombacho Volcano Nature Reserve is one of 78 protected areas of Nicaragua. MombachoŌĆÖs last eruption occurred in 1570. There is no historical knowledge of earli ...

just outside Granada, and Momotombo

Momotombo is a stratovolcano in Nicaragua, not far from the city of Le├│n. It stands on the shores of Lago de Managua. An eruption of the volcano in 1610 forced inhabitants of the Spanish city of Le├│n to relocate about west. The ruins of th ...

near Le├│n. The lowland area runs from the Gulf of Fonseca

The Gulf of Fonseca ( es, Golfo de Fonseca; ), a part of the Pacific Ocean, is a gulf in Central America, bordering El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua.

History

Fonseca Bay was discovered for Europeans in 1522 by Gil Gonz├Īlez de ├üv ...

to Nicaragua's Pacific border with Costa Rica south of Lake Nicaragua

Lake Nicaragua or Cocibolca or Granada ( es, Lago de Nicaragua, , or ) is a freshwater lake in Nicaragua. Of tectonic origin and with an area of , it is the largest lake in Central America, the 19th largest lake in the world (by area) and the t ...

. Lake Nicaragua is the largest freshwater lake in Central America (20th largest in the world), and is home to some of the world's rare freshwater sharks ( Nicaraguan shark). The Pacific lowlands region is the most populous, with over half of the nation's population.

The eruptions of western Nicaragua's 40 volcanoes, many of which are still active, have sometimes devastated settlements but also have enriched the land with layers of fertile ash. The geologic activity that produces vulcanism also breeds powerful earthquakes. Tremors occur regularly throughout the Pacific zone, and earthquakes have nearly destroyed the capital city, Managua, more than once.["Nicaragua."](_blank)

''Encyclopedia Americana''. Grolier Online. (200-11-20

/ref>

Most of the Pacific zone is ''tierra caliente

''Tierra caliente'' is an informal term used in Latin America to refer to places with a distinctly tropical climate. These are usually regions from sea level from 0ŌĆō3,000 feet.Zech, W. and Hintermaier-Erhard, G. (2002); B├Čden der Welt ŌĆō Ein Bi ...

'', the "hot land" of tropical Spanish America at elevations under . Temperatures remain virtually constant throughout the year, with highs ranging between . After a dry season lasting from November to April, rains begin in May and continue to October, giving the Pacific lowlands of precipitation. Good soils and a favourable climate combine to make western Nicaragua the country's economic and demographic centre. The southwestern shore of Lake Nicaragua lies within of the Pacific Ocean. Thus the lake and the San Juan River were often proposed in the 19th century as the longest part of a canal route across the Central American isthmus. Canal proposals were periodically revived in the 20th and 21st centuries.[ Roughly a century after the opening of the ]Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panam├Ī, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a condui ...

, the prospect of a Nicaraguan ecocanal remains a topic of interest.

In addition to its beach and resort communities, the Pacific lowlands contains most of Nicaragua's Spanish colonial architecture and artifacts. Cities such as Le├│n and Granada

Granada (,, DIN: ; grc, ß╝ś╬╗╬╣╬▓ŽŹŽü╬│╬Ę, Elib├Įrg─ō; la, Illiberis or . ) is the capital city of the province of Granada, in the autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada mountains, at the c ...

abound in colonial architecture; founded in 1524, Granada is the oldest colonial city in the Americas.

North central highlands

Northern Nicaragua is the most diversified region producing coffee, cattle, milk products, vegetables, wood, gold, and flowers. Its extensive forests, rivers and geography are suited for ecotourism.

The central highlands are a significantly less populated and economically developed area in the north, between Lake Nicaragua and the Caribbean. Forming the country's

Northern Nicaragua is the most diversified region producing coffee, cattle, milk products, vegetables, wood, gold, and flowers. Its extensive forests, rivers and geography are suited for ecotourism.

The central highlands are a significantly less populated and economically developed area in the north, between Lake Nicaragua and the Caribbean. Forming the country's tierra templada Tierra templada (Spanish for ''temperate land'') is a pseudo-climatological term used in Latin America to refer to places which are either located in the tropics at a moderately high elevation or are marginally outside the astronomical tropics, prod ...

, or "temperate land", at elevations between , the highlands enjoy mild temperatures with daily highs of . This region has a longer, wetter rainy season than the Pacific lowlands, making erosion a problem on its steep slopes. Rugged terrain, poor soils, and low population density characterize the area as a whole, but the northwestern valleys are fertile and well settled.[

The area has a cooler climate than the Pacific lowlands. About a quarter of the country's agriculture takes place in this region, with coffee grown on the higher slopes. Oaks, ]pine

A pine is any conifer tree or shrub in the genus ''Pinus'' () of the family (biology), family Pinaceae. ''Pinus'' is the sole genus in the subfamily Pinoideae. The World Flora Online created by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and Missouri Botanic ...

s, moss

Mosses are small, non-vascular flowerless plants in the taxonomic division Bryophyta (, ) '' sensu stricto''. Bryophyta ('' sensu lato'', Schimp. 1879) may also refer to the parent group bryophytes, which comprise liverworts, mosses, and ...

, fern

A fern (Polypodiopsida or Polypodiophyta ) is a member of a group of vascular plants (plants with xylem and phloem) that reproduce via spores and have neither seeds nor flowers. The polypodiophytes include all living pteridophytes exce ...

s and orchids

Orchids are plants that belong to the family Orchidaceae (), a diverse and widespread group of flowering plants with blooms that are often colourful and fragrant.

Along with the Asteraceae, they are one of the two largest families of flowering ...

are abundant in the cloud forest

A cloud forest, also called a water forest, primas forest, or tropical montane cloud forest (TMCF), is a generally tropical or subtropical, evergreen, montane, moist forest characterized by a persistent, frequent or seasonal low-level cloud ...

s of the region.

Bird life in the forests of the central region includes resplendent quetzal

The resplendent quetzal (''Pharomachrus mocinno'') is a small bird found in southern Mexico and Central America, with two recognized subspecies, ''P. m. mocinno'' and ''P. m. costaricensis''. These animals live in tropical forests, particularly ...

s, goldfinches, hummingbird

Hummingbirds are birds native to the Americas and comprise the Family (biology), biological family Trochilidae. With about 361 species and 113 genus, genera, they occur from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego, but the vast majority of the species are ...

s, jays and toucanets.

Caribbean lowlands

This large rainforest

Rainforests are characterized by a closed and continuous tree canopy, moisture-dependent vegetation, the presence of epiphytes and lianas and the absence of wildfire. Rainforest can be classified as tropical rainforest or temperate rainfores ...

region is irrigated by several large rivers and is sparsely populated. The area has 57% of the territory of the nation and most of its mineral resources. It has been heavily exploited, but much natural diversity remains. The Rio Coco is the largest river in Central America; it forms the border with Honduras. The Caribbean coastline is much more sinuous than its generally straight Pacific counterpart; lagoons and deltas make it very irregular.

Nicaragua's Bosaw├Īs Biosphere Reserve The Bosaw├Īs Biosphere Reserve in the northern part of state Jinotega (border with Honduras), Nicaragua is a hilly tropical forest designated in 1997 as a UNESCO biosphere reserve. At approximately 20,000 km┬▓ (2 million hectares) in size, t ...

is in the Atlantic lowlands, part of which is located in the municipality of Siuna

Siuna is a county-sized administrative municipality in Nicaragua, located approximately northeast of the capital city of Managua and west of the coastal city and regional capital Puerto Cabezas in the North Caribbean Autonomous Region ( ...

; it protects of La Mosquitia forest ŌĆō almost 7% of the country's area ŌĆō making it the largest rainforest north of the Amazon

Amazon most often refers to:

* Amazons, a tribe of female warriors in Greek mythology

* Amazon rainforest, a rainforest covering most of the Amazon basin

* Amazon River, in South America

* Amazon (company), an American multinational technolog ...

in Brazil.

The municipalities of Siuna

Siuna is a county-sized administrative municipality in Nicaragua, located approximately northeast of the capital city of Managua and west of the coastal city and regional capital Puerto Cabezas in the North Caribbean Autonomous Region ( ...

, Rosita, and Bonanza

''Bonanza'' is an American Western television series that ran on NBC from September 13, 1959, to January 16, 1973. Lasting 14 seasons and 432 episodes, ''Bonanza'' is NBC's longest-running western, the second-longest-running western series on ...

, known as the "Mining Triangle", are located in the region known as the North Caribbean Coast Autonomous Region

The North Caribbean Coast Autonomous Region is one of two autonomous regions in Nicaragua. It was created by the Autonomy Statute of 7 September 1987. It covers an area of 33,106 km2 and has a population of 541,189 (2021 estimate). It is the ...

, in the Caribbean lowlands. Bonanza still contains an active gold mine owned by HEMCO. Siuna and Rosita do not have active mines but panning for gold is still very common in the region.

Nicaragua's tropical east coast is very different from the rest of the country. The climate is predominantly tropical, with high temperature and high humidity. Around the area's principal city of Bluefields, English is widely spoken along with the official Spanish. The population more closely resembles that found in many typical Caribbean ports than the rest of Nicaragua.

A great variety of birds can be observed including eagle

Eagle is the common name for many large birds of prey of the family Accipitridae. Eagles belong to several groups of genera, some of which are closely related. Most of the 68 species of eagle are from Eurasia and Africa. Outside this area, j ...

s, toucan

Toucans (, ) are members of the Neotropical near passerine bird family Ramphastidae. The Ramphastidae are most closely related to the American barbets. They are brightly marked and have large, often colorful bills. The family includes five g ...

s, parakeet

A parakeet is any one of many small to medium-sized species of parrot, in multiple genera, that generally has long tail feathers.

Etymology and naming

The name ''parakeet'' is derived from the French wor''perroquet'' which is reflected in ...

s and macaw

Macaws are a group of New World parrots that are long-tailed and often colorful. They are popular in aviculture or as companion parrots, although there are conservation concerns about several species in the wild.

Biology

Of the many differ ...

s. Other animal life in the area includes different species of monkey

Monkey is a common name that may refer to most mammals of the infraorder Simiiformes, also known as the simians. Traditionally, all animals in the group now known as simians are counted as monkeys except the apes, which constitutes an incomple ...

s, anteater

Anteater is a common name for the four extant mammal species of the suborder Vermilingua (meaning "worm tongue") commonly known for eating ants and termites. The individual species have other names in English and other languages. Together wit ...

s, white-tailed deer

Deer or true deer are hoofed ruminant mammals forming the family Cervidae. The two main groups of deer are the Cervinae, including the muntjac, the elk (wapiti), the red deer, and the fallow deer; and the Capreolinae, including the re ...

and tapir

Tapirs ( ) are large, herbivorous mammals belonging to the family Tapiridae. They are similar in shape to a pig, with a short, prehensile nose trunk. Tapirs inhabit jungle and forest regions of South and Central America, with one species inh ...

s.

Flora and fauna

Nicaragua is home to a rich variety of plants and animals. Nicaragua is located in the middle of the Americas and this privileged location has enabled the country to serve as host to a great biodiversity. This factor, along with the weather and light altitudinal variations, allows the country to harbor 248 species of amphibians and reptiles, 183 species of mammals, 705 bird species, 640 fish species, and about 5,796 species of plants.

The region of great forests is located on the eastern side of the country. Rainforests are found in the

Nicaragua is home to a rich variety of plants and animals. Nicaragua is located in the middle of the Americas and this privileged location has enabled the country to serve as host to a great biodiversity. This factor, along with the weather and light altitudinal variations, allows the country to harbor 248 species of amphibians and reptiles, 183 species of mammals, 705 bird species, 640 fish species, and about 5,796 species of plants.

The region of great forests is located on the eastern side of the country. Rainforests are found in the R├Ło San Juan Department

R├Ło San Juan () is a department in Nicaragua. It was formed in 1957 from parts of Chontales and Zelaya departments. It covers an area of 7,543 km2 and has a population of 137,189 (2021 estimate). The capital is San Carlos. The departm ...

and in the autonomous regions of RAAN and RAAS. This biome groups together the greatest biodiversity in the country and is largely protected by the Indio Ma├Łz Biological Reserve in the south and the Bosaw├Īs Biosphere Reserve The Bosaw├Īs Biosphere Reserve in the northern part of state Jinotega (border with Honduras), Nicaragua is a hilly tropical forest designated in 1997 as a UNESCO biosphere reserve. At approximately 20,000 km┬▓ (2 million hectares) in size, t ...

in the north. The Nicaraguan jungles, which represent about , are considered the lungs of Central America and comprise the second largest-sized rainforest of the Americas.

There are currently 78 protected areas in Nicaragua, covering more than , or about 17% of its landmass. These include wildlife refuge

A nature reserve (also known as a wildlife refuge, wildlife sanctuary, biosphere reserve or bioreserve, natural or nature preserve, or nature conservation area) is a protected area of importance for flora, fauna, or features of geological or ...

s and nature reserve

A nature reserve (also known as a wildlife refuge, wildlife sanctuary, biosphere reserve or bioreserve, natural or nature preserve, or nature conservation area) is a protected area of importance for flora, fauna, or features of geological o ...

s that shelter a wide range of ecosystem