Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an

ethnic,

national,

racial

A race is a categorization of humans based on shared physical or social qualities into groups generally viewed as distinct within a given society. The term came into common usage during the 1500s, when it was used to refer to groups of variou ...

, or

religious

Religion is usually defined as a social- cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatur ...

group—in whole or in part.

Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944,

[ combining the ]Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

word (, "race, people") with the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

suffix ("act of killing").[.]

In 1948, the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoniz ...

Genocide Convention defined genocide as any of five "acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group." These five acts were: killing members of the group, causing them serious bodily or mental harm, imposing living conditions intended to destroy the group, preventing births, and forcibly transferring children out of the group. Victims are targeted because of their real or perceived membership of a group, not randomly.Political Instability Task Force

The Political Instability Task Force (PITF), formerly known as State Failure Task Force, is a Federal government of the United States, U.S. government-sponsored research project to build a database on major domestic politics, political conflicts le ...

estimated that 43 genocides occurred between 1956 and 2016, resulting in about 50 million deaths.evil

Evil, in a general sense, is defined as the opposite or absence of good. It can be an extremely broad concept, although in everyday usage it is often more narrowly used to talk about profound wickedness and against common good. It is general ...

. As a label, it is contentious because it is moralizing, and has been used as a type of moral category since the late 1990s.

Etymology

Before the term ''genocide'' was coined, there were various ways of describing such events. Some languages already had words for such killings, including German (, ) and Polish (, ).[ (NB. Uses the term for the first time.)][ (NB. The editors cite ]August Graf von Platen

August is the eighth month of the year in the Julian and Gregorian calendars, and the fifth of seven months to have a length of 31 days. Its zodiac sign is Leo and was originally named ''Sextilis'' in Latin because it was the 6th month in ...

to have used the term in his 1831 ode.) In 1941, when describing the "methodical, merciless butchery" of "scores of thousands" of Russians by Nazi troops during the German invasion of the Soviet Union

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named afte ...

, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

spoke of "a crime without a name". In 1944, Raphael Lemkin coined the term ''genocide'' as a hybrid combination of the Ancient Greek word () 'race, people' with the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

, 'to kill'; his book ''Axis Rule in Occupied Europe'' (1944) describes the implementation of Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

policies in occupied Europe

German-occupied Europe refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly occupied and civil-occupied (including puppet governments) by the military forces and the government of Nazi Germany at various times between 1939 an ...

and mentions earlier mass killings

Mass killing is a concept which has been proposed by genocide scholars who wish to define incidents of non-combat killing which are perpetrated by a government or a state. A mass killing is commonly defined as the killing of group members withou ...

.assassination of Talat Pasha

On 15 March 1921, Armenian student Soghomon Tehlirian assassinated Talaat Pasha—former grand vizier of the Ottoman Empire and the main architect of the Armenian genocide—in Berlin. At his trial, Tehlirian argued, "I have killed a man, bu ...

, the main architect of the Armenian genocide, by Armenian Soghomon Tehlirian, Lemkin asked his professor why there was no law under which Talat could be charged.the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

at the Nuremberg Trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945, Nazi Germany invaded m ...

that the United Nations defined the crime of genocide under international law

International law (also known as public international law and the law of nations) is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognized as binding between states. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for ...

in the Genocide Convention.The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' announced that "Genocide Is the New Name for the Crime Fastened on the Nazi Leaders"; the word was used in indictments at the Nuremberg trials, held from 1945, but solely as a descriptive term, not yet as a formal legal term.Arthur Greiser

Arthur Karl Greiser (22 January 1897 – 21 July 1946) was a Nazi German politician, SS-''Obergruppenführer'', ''Gauleiter'' and ''Reichsstatthalter'' (Reich Governor) of the German-occupied territory of ''Wartheland''. He was one of the perso ...

and Amon Leopold Goth in 1946 were the first trials in which judgments included the term.

Prohibited acts

The Genocide Convention establishes five prohibited acts that, when committed with the requisite intent, amount to genocide. Although massacre-style killings are the most commonly identified and punished as genocide, the range of violence that is contemplated by the law is significantly broader.[Sareta Ashraph, Beyond Killing: Gender, Genocide, & Obligations Under International Law 3 (Global Justice Center 2018).]

Killing members of the group

While mass killing is not necessary for genocide to have been committed, it has been present in almost all recognized genocides. A near-uniform pattern has emerged throughout history in which men and adolescent boys are singled out for murder in the early stages, such as in the genocide of the Yazidis by Daesh, the Ottoman Turks' attack on the Armenians, and the Burmese security forces' attacks on the Rohingya. Men and boys are typically subject to "fast" killings, such as by gunshot. Women and girls are more likely to die slower deaths by slashing, burning, or as a result of sexual violence. The jurisprudence of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda

The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR; french: Tribunal pénal international pour le Rwanda; rw, Urukiko Mpanabyaha Mpuzamahanga Rwashyiriweho u Rwanda) was an international court established in November 1994 by the United Nation ...

(ICTR), among others, shows that both the initial executions and those that quickly follow other acts of extreme violence, such as rape

Rape is a type of sexual assault usually involving sexual intercourse or other forms of sexual penetration carried out against a person without their consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, coercion, abuse of authority, or ...

and torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons such as punishment, extracting a confession, interrogational torture, interrogation for information, or intimidating third parties. definitions of tortur ...

, are recognized as falling under the first prohibited act.

A less settled discussion is whether deaths that are further removed from the initial acts of violence can be addressed under this provision of the Genocide Convention. Legal scholars have posited, for example, that deaths resulting from other genocidal acts including causing serious bodily or mental harm or the successful deliberate infliction of conditions of life calculated to bring about physical destruction should be considered genocidal killings.

Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group ''Article II(b)''

This second prohibited act can encompass a wide range of non-fatal genocidal acts. The ICTR and International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) have held that rape and sexual violence may constitute the second prohibited act of genocide by causing both physical and mental harm. In its landmark Akayesu decision, the ICTR held that rapes and sexual violence resulted in "physical and psychological destruction". Sexual violence is a hallmark of genocidal violence, with most genocidal campaigns explicitly or implicitly sanctioning it.

Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction

The third prohibited act is distinguished from the genocidal act of killing because the deaths are not immediate (or may not even come to pass), but rather create circumstances that do not support prolonged life.[''Kayishema and Ruzindana,'' (Trial Chamber), 21 May 1999, para. 548] The drafters incorporated the act to account for the horrors of the Nazi concentration camps

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

and to ensure that similar conditions never be imposed again. However, it could also apply to the Armenian death marches, the siege of Mount Sinjar

The Sinjar Mountains ( ku, چیایێ شنگالێ, translit=Çiyayê Şingalê, ar, جبل سنجار, translit=Jabal Sinjār, syr, ܛܘܪܐ ܕܫܝܓܪ, Ṭura d'Shingar,) are a mountain range that runs east to west, rising above the surroundi ...

by Daesh, the deprivation of water and forcible deportation against ethnic groups in Darfur, and the destruction and razing of communities in Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

.

The ICTR provided guidance into what constitutes a violation of the third act. In Akayesu, it identified "subjecting a group of people to a subsistence diet, systematic expulsion from homes and the reduction of essential medical services below minimum requirement" as rising to genocide. In Kayishema and Ruzindana, it extended the list to include: "lack of proper housing, clothing, hygiene and medical care or excessive work or physical exertion" among the conditions.

Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group

The fourth prohibited act is aimed at preventing the protected group from regenerating through reproduction. It encompasses acts with the single intent of affecting reproduction and intimate relationships, such as involuntary sterilization, forced abortion, the prohibition of marriage, and long-term separation of men and women intended to prevent procreation.

Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group

The final prohibited act is the only prohibited act that does not lead to physical or biological destruction, but rather to destruction of the group as a cultural and social unit.

Crime

Pre-criminalization view

Before genocide was made a crime against national law, it was considered a sovereign right.

International law

After the Holocaust, which had been perpetrated by

After the Holocaust, which had been perpetrated by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

prior to and during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, Lemkin successfully campaigned for the universal acceptance of international laws defining and forbidding genocides. In 1946, the first session of the United Nations General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; french: link=no, Assemblée générale, AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as the main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ of the UN. Curr ...

adopted a resolution that affirmed genocide was a crime under international law and enumerated examples of such events (but did not provide a full legal definition of the crime). In 1948, the UN General Assembly adopted the '' Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide'' (CPPCG) which defined the crime of genocide for the first time.

The ''CPPCG'' was adopted by the UN General Assembly on 9 December 1948International Criminal Court

The International Criminal Court (ICC or ICCt) is an intergovernmental organization and international tribunal seated in The Hague, Netherlands. It is the first and only permanent international court with jurisdiction to prosecute individuals f ...

(ICC). Article II of the Convention defines genocide as:

Incitement to genocide is recognized as a separate crime under international law and an inchoate crime which does not require genocide to have taken place to be prosecutable.World Jewish Congress

The World Jewish Congress (WJC) was founded in Geneva, Switzerland in August 1936 as an international federation of Jewish communities and organizations. According to its mission statement, the World Jewish Congress' main purpose is to act as ...

and Raphael Lemkin's conception, with some scholars popularly emphasizing in literature the role of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

, a permanent United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, an ...

member. The Soviets argued that the convention's definition should follow the etymology of the term,Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

in particular may have feared greater international scrutiny of the country's political killings, such as the Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secret ...

. Lemkin, who coined ''genocide'', approached the Soviet delegation as the resolution vote came close to reassure the Soviets that there was no conspiracy against them; none in the Soviet-led bloc opposed the resolution, which passed unanimously in December 1946.United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

, feared that including political groups in the definition would invite international intervention in domestic politics.human rights

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hu ...

violation as genocide, and that many events deemed by Lemkin genocidal did not amount to genocide. As the Cold War began, this change was the result of Lemkin's turn to anti-communism

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when the United States and the ...

in an attempt to convince the United States to ratify the Genocide Convention.

Intent

Under international law, genocide has two mental ('' mens rea'') elements: the general mental element and the element of specific intent (''dolus specialis

References

Additional sources

*

*

{{Latin phrases

D

ca:Locució llatina#D

da:Latinske ord og vendinger#D

fr:Liste de locutions latines#D

id:Daftar frasa Latin#D

it:Locuzioni latine#D

nl:Lijst van Latijnse spreekwoorden en uitdru ...

''). The general element refers to whether the prohibited acts were committed with intent, knowledge, recklessness, or negligence. For most serious international crimes, including genocide, the requirement is that the perpetrator act with intent. The Rome Statute defines intent as meaning to engage in the conduct and, in relation to consequences, as meaning to cause that consequence or being "aware that it will occur in the ordinary course of events".

The specific intent element defines the purpose of committing the acts: "to destroy in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such". The specific intent is a core factor distinguishing genocide from other international crimes, such as war crimes or crimes against humanity.

"Intent to destroy"

In 2007, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) noted in its judgement on ''Jorgic v. Germany'' case that, in 1992, the majority of legal scholars took the narrow view that "intent to destroy" in the CPPCG meant the intended physical-biological destruction of the protected group, and that this was still the majority opinion. But the ECHR also noted that a minority took a broader view, and did not consider biological-physical destruction to be necessary, as the intent to destroy a national, racial, religious or ethnic group was enough to qualify as genocide.

In the same judgement, the ECHR reviewed the judgements of several international and municipal courts. It noted that the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia and the International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; french: Cour internationale de justice, links=no; ), sometimes known as the World Court, is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN). It settles disputes between states in accordanc ...

had agreed with the narrow interpretation (that biological-physical destruction was necessary for an act to qualify as genocide). The ECHR also noted that at the time of its judgement, apart from courts in Germany (which had taken a broad view), that there had been few cases of genocide under other Convention states' municipal laws, and that "There are no reported cases in which the courts of these States have defined the type of group destruction the perpetrator must have intended in order to be found guilty of genocide."

In the case of "Onesphore Rwabukombe", the German Supreme Court adhered to its previous judgement, and did not follow the narrow interpretation of the ICTY and the ICJ.

"In whole or in part"

The phrase "in whole or in part" has been subject to much discussion by scholars of international humanitarian law.

"A national, ethnic, racial or religious group"

The drafters of the CPPCG chose not to include political or social groups among the protected groups. Instead, they opted to focus on "stable" identities, attributes that are historically understood as being born into and unable or unlikely to change over time. This definition conflicts with modern conceptions of race as a social construct rather than innate fact and the practice of changing religion, etc.[Agnieszka Szpak, ''National, Ethnic, Racial, and Religious Groups Protected against Genocide in the Jurisprudence of the ad hoc International Criminal Tribunals'', 23 Eur. J. Int'L L. 155 (2012).]

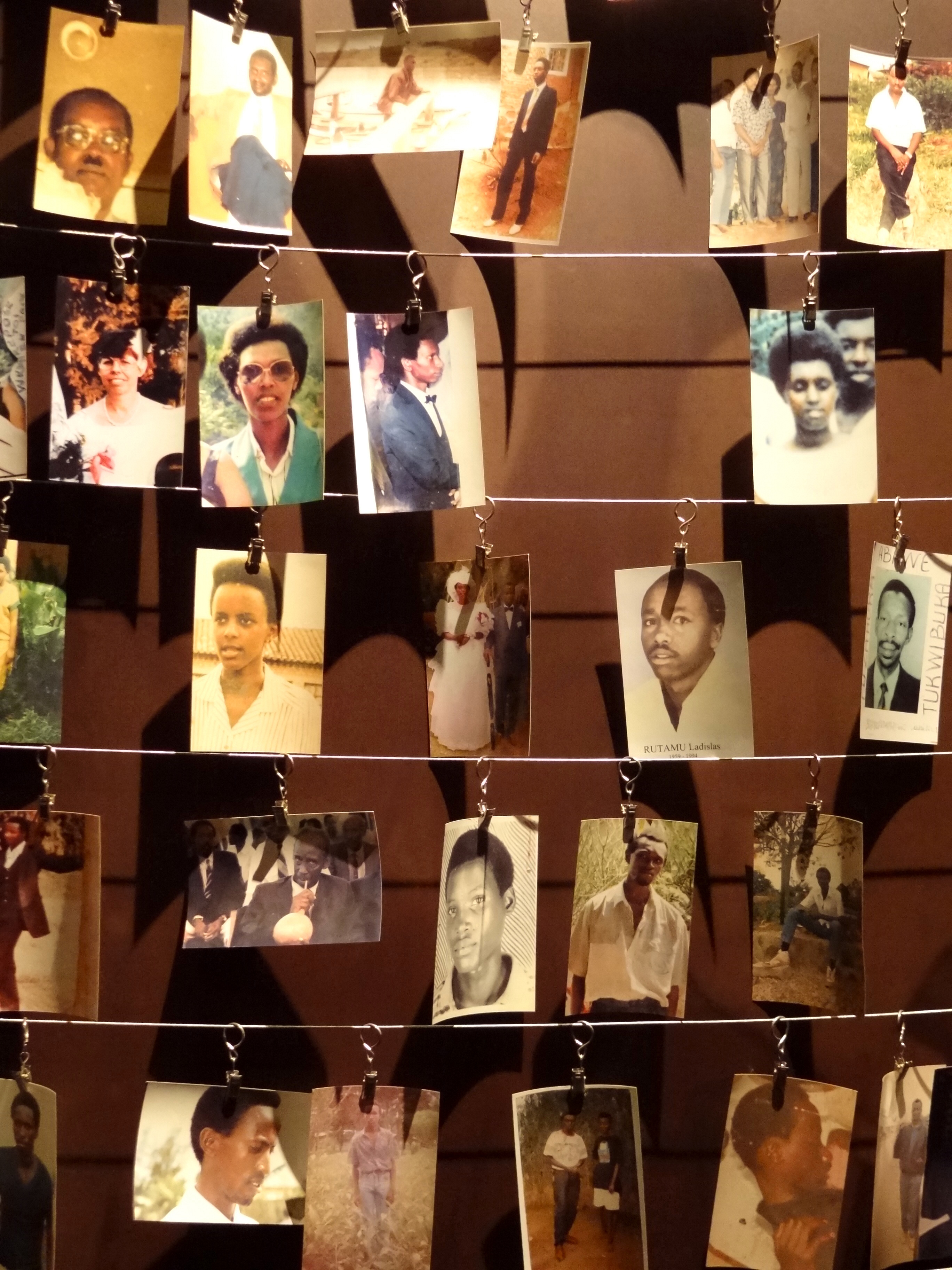

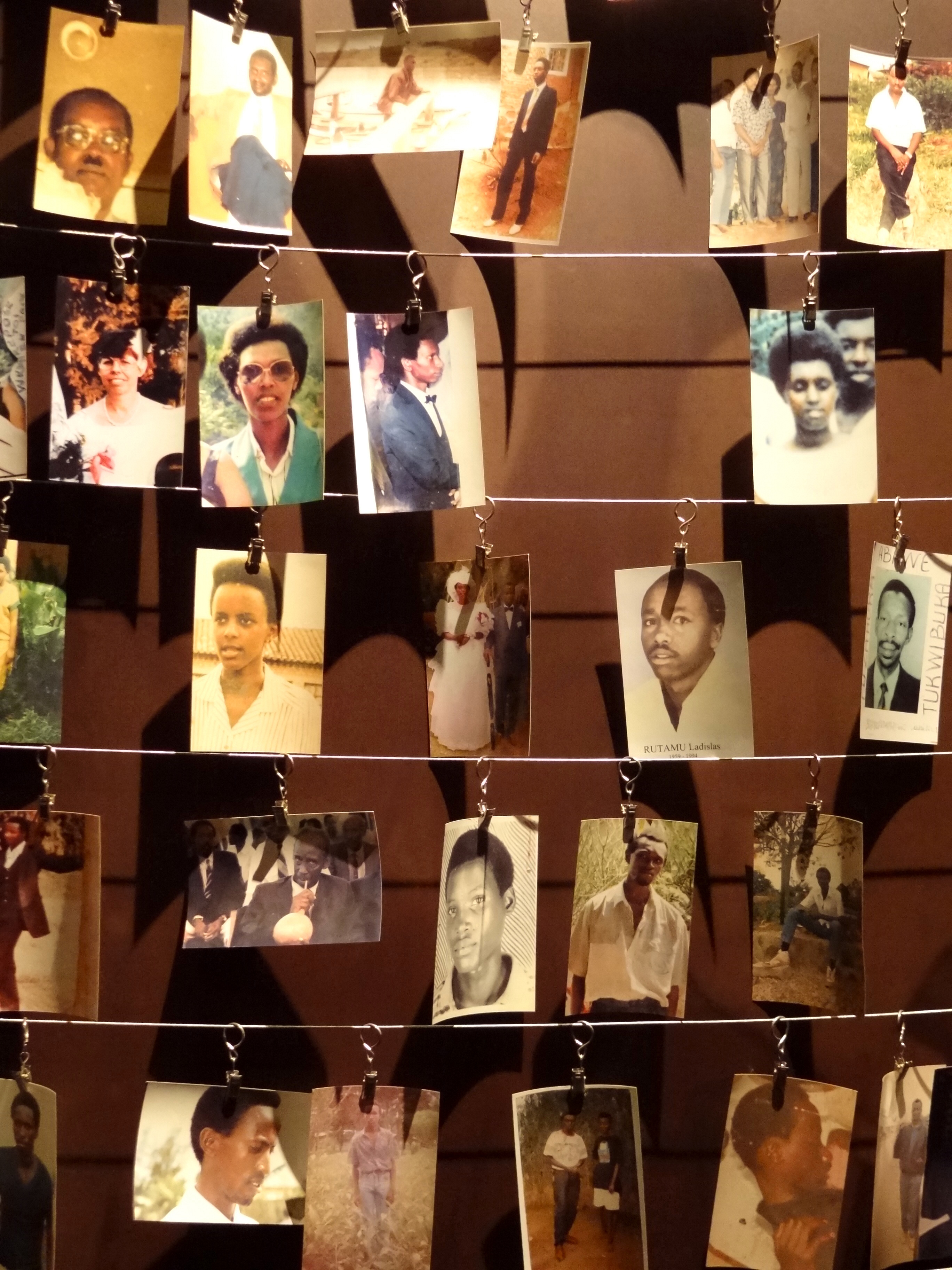

International criminal courts have typically applied a mix of objective and subjective markers for determining whether or not a targeted population is a distinct group. Differences in language, physical appearance, religion, and cultural practices are objective criteria that may show that the groups are distinct. However, in circumstances such as the Rwandan genocide

The Rwandan genocide occurred between 7 April and 15 July 1994 during the Rwandan Civil War. During this period of around 100 days, members of the Tutsi minority ethnic group, as well as some moderate Hutu and Twa, were killed by armed H ...

, Hutu

The Hutu (), also known as the Abahutu, are a Bantu ethnic or social group which is native to the African Great Lakes region. They mainly live in Rwanda, Burundi and the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, where they form one of the p ...

s and Tutsi

The Tutsi (), or Abatutsi (), are an ethnic group of the African Great Lakes region. They are a Bantu-speaking ethnic group and the second largest of three main ethnic groups in Rwanda and Burundi (the other two being the largest Bantu ethnic ...

s were often physically indistinguishable.William A. Schabas

William Anthony Schabas, OC (born 19 November 1950) is a Canadian academic specialising in international criminal and human rights law. He is professor of international law at Middlesex University in the United Kingdom, professor of internation ...

, Genocide in International Law: The Crime of Crimes 124–129 (2d. ed. 2009).

Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide

The convention came into force as international law on 12 January 1951 after the minimum 20 countries became parties. At that time however, only two of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council were parties to the treaty: France and the Republic of China. The Soviet Union ratified in 1954, the United Kingdom in 1970, the People's Republic of China in 1983 (having replaced the Taiwan-based Republic of China on the UNSC in 1971), and the United States in 1988.

William Schabas

William Anthony Schabas, OC (born 19 November 1950) is a Canadian academic specialising in international criminal and human rights law. He is professor of international law at Middlesex University in the United Kingdom, professor of internation ...

has suggested that a permanent body as recommended by the Whitaker Report to monitor the implementation of the Genocide Convention, and require states to issue reports on their compliance with the convention (such as were incorporated into the United Nations Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture), would make the convention more effective.

UN Security Council Resolution 1674

UN Security Council Resolution 1674, adopted by the United Nations Security Council on 28 April 2006, "reaffirms the provisions of paragraphs 138 and 139 of the 2005 World Summit Outcome Document

The 2005 World Summit, held between 14 and 16 September 2005, was a follow-up summit meeting to the United Nations' 2000 Millennium Summit, which had led to the Millennium Declaration of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Representatives ( ...

regarding the responsibility to protect populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity". The resolution committed the council to action to protect civilians in armed conflict.

In 2008 the UN Security Council adopted resolution 1820, which noted that "rape and other forms of sexual violence can constitute war crimes, crimes against humanity or a constitutive act with respect to genocide".

Municipal law

Since the Convention came into effect in January 1951 about 80 United Nations member states have passed legislation that incorporates the provisions of CPPCG into their municipal law.

Other definitions of genocide

Writing in 1998, Kurt Jonassohn and Karin Björnson stated that the CPPCG was a legal instrument resulting from a diplomatic compromise. As such the wording of the treaty is not intended to be a definition suitable as a research tool, and although it is used for this purpose, as it has international legal credibility that others lack, other genocide definitions have also been proposed. Jonassohn and Björnson go on to say that none of these alternative definitions have gained widespread support for various reasons.[ ] Jonassohn and Björnson postulate that the major reason why no single generally accepted genocide definition has emerged is because academics have adjusted their focus to emphasise different periods and have found it expedient to use slightly different definitions. For example, Frank Chalk and Kurt Jonassohn studied all human history, while Leo Kuper

Leo Kuper (20 November 1908 – 23 May 1994) was a South African sociologist specialising in the study of genocide.

Early life and legal career

Kuper was born to a Lithuanian Jewish family. His siblings included his sister Mary (d. 1948), who ...

and Rudolph Rummel in their more recent works concentrated on the 20th century, and Helen Fein, Barbara Harff

Barbara Harff (born 17 July 1942) is professor of political science emerita at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. In 2003 and again in 2005 she was a distinguished visiting professor at the Strassler Center for Holocaust and Genocide S ...

, and Ted Gurr have looked at post-World War II events.

Political and social groups

The exclusion of social and political groups as targets of genocide in the CPPCG legal definition has been criticized by some historians and sociologists, for example, M. Hassan Kakar in his book ''The Soviet Invasion and the Afghan Response, 1979–1982'' argues that the international definition of genocide is too restricted, and that it should include political groups or any group so defined by the perpetrator and quotes Chalk and Jonassohn: "Genocide is a form of one-sided mass killing in which a state or other authority intends to destroy a group, as that group and membership in it are defined by the perpetrator." In turn some states such as Ethiopia, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

, and Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

include political groups as legitimate genocide victims in their anti-genocide laws.

Harff and Gurr defined genocide as "the promotion and execution of policies by a state or its agents which result in the deaths of a substantial portion of a group ... hen

Hen commonly refers to a female animal: a female chicken, other gallinaceous bird, any type of bird in general, or a lobster. It is also a slang term for a woman.

Hen or Hens may also refer to:

Places Norway

*Hen, Buskerud, a village in Ringer ...

the victimized groups are defined primarily in terms of their communal characteristics, i.e., ethnicity, religion or nationality". Harff and Gurr also differentiate between genocides and politicide

Political cleansing of population is eliminating categories of people in specific areas for political reasons. The means may vary from forced migration to genocide.

Politicide

Politicide is the deliberate physical destruction or elimination o ...

s by the characteristics by which members of a group are identified by the state. In genocides, the victimized groups are defined primarily in terms of their communal characteristics, i.e., ethnicity, religion or nationality. In politicides the victim groups are defined primarily in terms of their hierarchical position or political opposition to the regime and dominant groups. Daniel D. Polsby and Don B. Kates, Jr. state that "we follow Harff's distinction between genocides and 'pogrom

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russia ...

s', which she describes as 'short-lived outbursts by mobs, which, although often condoned by authorities, rarely persist'. If the violence persists for long enough, however, Harff argues, the distinction between condonation and complicity collapses."gender identity

Gender identity is the personal sense of one's own gender. Gender identity can correlate with a person's assigned sex or can differ from it. In most individuals, the various biological determinants of sex are congruent, and consistent with the ...

.

Transgender genocide

In 2013 some international trans activists introduced the term ‘transcide’ to describe the elevated level of killings of trans people globally. A coalition of NGOs from South America and Europe started the “Stop Trans Genocide” campaign. The term "trancide" follows an earlier term, gendercide

Gendercide is the systematic killing of members of a specific gender. The term is related to the general concepts of assault and murder against victims due to their gender, with violence against women and men being problems dealt with by human r ...

. Legal scholars have argued that the definition of genocide should be expanded to cover transgender people, because they are victims of institutional discrimination, persecution, and violence.

International prosecution

By ''ad hoc'' tribunals

All signatories to the CPPCG are required to prevent and punish acts of genocide, both in peace and wartime, though some barriers make this enforcement difficult. In particular, some of the signatories—namely,

All signatories to the CPPCG are required to prevent and punish acts of genocide, both in peace and wartime, though some barriers make this enforcement difficult. In particular, some of the signatories—namely, Bahrain

Bahrain ( ; ; ar, البحرين, al-Bahrayn, locally ), officially the Kingdom of Bahrain, ' is an island country in Western Asia. It is situated on the Persian Gulf, and comprises a small archipelago made up of 50 natural islands and an ...

, Bangladesh

Bangladesh (}, ), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million people in an area of . Bangladesh is among the mos ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, Malaysia

Malaysia ( ; ) is a country in Southeast Asia. The federation, federal constitutional monarchy consists of States and federal territories of Malaysia, thirteen states and three federal territories, separated by the South China Sea into two r ...

, the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, bor ...

, the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

, Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

, Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, north and ...

, and former Yugoslavia

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, commonly referred to as SFR Yugoslavia or simply as Yugoslavia, was a country in Central and Southeast Europe. It emerged in 1945, following World War II, and lasted until 1992, with the breakup of Yu ...

—signed with the proviso that no claim of genocide could be brought against them at the International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; french: Cour internationale de justice, links=no; ), sometimes known as the World Court, is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN). It settles disputes between states in accordanc ...

without their consent. Despite official protests from other signatories (notably Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ge ...

and Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the ...

) on the ethics and legal standing of these reservations, the immunity from prosecution they grant has been invoked from time to time, as when the United States refused to allow a charge of genocide brought against it by former Yugoslavia following the 1999 Kosovo War

The Kosovo War was an armed conflict in Kosovo that started 28 February 1998 and lasted until 11 June 1999. It was fought by the forces of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (i.e. Serbia and Montenegro), which controlled Kosovo before the wa ...

.

It is commonly accepted that, at least since World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, genocide has been illegal under customary international law as a peremptory norm, as well as under conventional international law. Acts of genocide are generally difficult to establish for prosecution because a chain of accountability must be established. International criminal courts and tribunals function primarily because the states involved are incapable or unwilling to prosecute crimes of this magnitude themselves.

Nuremberg Tribunal (1945–1946)

The Nazi leaders who were prosecuted shortly after World War II for taking part in the Holocaust, and other mass murders, were charged under existing international law

International law (also known as public international law and the law of nations) is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognized as binding between states. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for ...

s, such as crimes against humanity, as the crime of "genocide' was not formally defined until the 1948 ''Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide'' (CPPCG). Nevertheless, the recently coined term appeared in the indictment of the Nazi leaders, Count 3, which stated that those charged had "conducted deliberate and systematic genocide—namely, the extermination of racial and national groups—against the civilian populations of certain occupied territories in order to destroy particular races and classes of people, and national, racial or religious groups, particularly Jews, Poles, Gypsies and others."

International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (1993–2017)

The term ''Bosnian genocide'' is used to refer either to the killings committed by Serb forces in

The term ''Bosnian genocide'' is used to refer either to the killings committed by Serb forces in Srebrenica

Srebrenica ( sr-cyrl, Сребреница, ) is a town and municipality located in the easternmost part of Republika Srpska, an entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is a small mountain town, with its main industry being salt mining and a nearby ...

in 1995, or to ethnic cleansing that took place elsewhere during the 1992–1995 Bosnian War.

In 2001, the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) judged that the 1995 Srebrenica massacre was an act of genocide. On 26 February 2007, the International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; french: Cour internationale de justice, links=no; ), sometimes known as the World Court, is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN). It settles disputes between states in accordanc ...

(ICJ), in the '' Bosnian Genocide Case'' upheld the ICTY's earlier finding that the massacre in Srebrenica and Zepa constituted genocide, but found that the Serbian government had not participated in a wider genocide on the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina during the war, as the Bosnian government had claimed.

On 12 July 2007, European Court of Human Rights when dismissing the appeal by Nikola Jorgić against his conviction for genocide by a German court ('' Jorgic v. Germany'') noted that the German courts wider interpretation of genocide has since been rejected by international courts considering similar cases. The ECHR also noted that in the 21st century "Amongst scholars, the majority have taken the view that ethnic cleansing, in the way in which it was carried out by the Serb forces in Bosnia and Herzegovina in order to expel Muslims and Croats from their homes, did not constitute genocide. However, there are also a considerable number of scholars who have suggested that these acts did amount to genocide, and the ICTY has found in the Momcilo Krajisnik case that the actus reus of genocide was met in Prijedor "With regard to the charge of genocide, the Chamber found that in spite of evidence of acts perpetrated in the municipalities which constituted the actus reus of genocide".

About 30 people have been indicted for participating in genocide or complicity in genocide during the early 1990s in Bosnia. To date, after several plea bargains and some convictions that were successfully challenged on appeal two men, Vujadin Popović and Ljubiša Beara, have been found guilty of committing genocide, Zdravko Tolimir has been found guilty of committing genocide and conspiracy to commit genocide, and two others, Radislav Krstić and Drago Nikolić, have been found guilty of aiding and abetting genocide. Three others have been found guilty of participating in genocides in Bosnia by German courts, one of whom Nikola Jorgić lost an appeal against his conviction in the European Court of Human Rights. A further eight men, former members of the Bosnian Serb security forces were found guilty of genocide by the State Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina :''This article refers to the Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina, a domestic court which includes international judges and prosecutors and a section for war crimes; it should not be confused with the separate International Criminal Tribunal for the For ...

(See List of Bosnian genocide prosecutions).

Slobodan Milošević, as the former President of Serbia and of Yugoslavia, was the most senior political figure to stand trial at the ICTY. He died on 11 March 2006 during his trial where he was accused of genocide or complicity in genocide in territories within Bosnia and Herzegovina, so no verdict was returned. In 1995, the ICTY issued a warrant for the arrest of Bosnian Serbs Radovan Karadžić

Radovan Karadžić ( sr-cyr, Радован Караџић, ; born 19 June 1945) is a Bosnian Serb politician, psychiatrist and poet. He was convicted of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes by the International Criminal Tr ...

and Ratko Mladić

Ratko Mladić ( sr-Cyrl, Ратко Младић, ; born 12 March 1942) is a Bosnian Serb convicted war criminal and colonel-general who led the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS) during the Yugoslav Wars. In 2017, he was found guilty of committing ...

on several charges including genocide. On 21 July 2008, Karadžić was arrested in Belgrade, and later tried in The Hague accused of genocide among other crimes. On 24 March 2016, Karadžić was found guilty of genocide in Srebrenica, war crimes and crimes against humanity, 10 of the 11 charges in total, and sentenced to 40 years' imprisonment.

International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (1994–present)

The

The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda

The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR; french: Tribunal pénal international pour le Rwanda; rw, Urukiko Mpanabyaha Mpuzamahanga Rwashyiriweho u Rwanda) was an international court established in November 1994 by the United Nation ...

(ICTR) is a court under the auspices of the United Nations for the prosecution of offenses committed in Rwanda during the genocide which occurred there during April 1994, commencing on 6 April. The ICTR was created on 8 November 1994 by the Security Council of the United Nations in order to judge those people responsible for the acts of genocide and other serious violations of the international law performed in the territory of Rwanda, or by Rwandan citizens in nearby states, between 1 January and 31 December 1994.

So far, the ICTR has finished nineteen trials and convicted twenty-seven accused persons. On 14 December 2009, two more men were accused and convicted for their crimes. Another twenty-five persons are still on trial. Twenty-one are awaiting trial in detention, two more added on 14 December 2009. Ten are still at large. The first trial, of Jean-Paul Akayesu

Jean-Paul Akayesu (born 1953 in Taba) is a former teacher, school inspector, and Republican Democratic Movement (MDR) politician from Rwanda, convicted of genocide for his role in inciting the Rwandan genocide. Life

Akayesu was the mayor of T ...

, began in 1997. Akayesu was the first person ever to be convicted of the crime of genocide. In October 1998, Akayesu was sentenced to life imprisonment. Jean Kambanda

Jean Kambanda (born October 19, 1955) is a Rwandan former politician who served as the Prime Minister of Rwanda in the caretaker government from the start of the 1994 Rwandan genocide. He is the only head of government to plead guilty to genocid ...

, interim Prime Minister, pleaded guilty.

Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (2003–present)

The Khmer Rouge, led by Pol Pot,

The Khmer Rouge, led by Pol Pot, Ta Mok

Ta Mok ( km, តាម៉ុក; born Chhit Choeun (); 1924 – 21 July 2006) also known as Nguon Kang, was a Cambodian military chief and soldier who was a senior figure in the Khmer Rouge and the leader of the national army of Democratic Kam ...

and other leaders, organized the mass killing of ideologically suspect groups. The total number of victims is estimated at 1.7 million Cambodia

Cambodia (; also Kampuchea ; km, កម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: ), officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, spanning an area of , bordered by Thailan ...

ns between 1975 and 1979, including deaths from slave labour.[Cambodian Genocide Program](_blank)

Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Sta ...

's MacMillan Center for International and Area Studies

On 6 June 2003 the Cambodian government and the United Nations reached an agreement to set up the (ECCC) which would focus exclusively on crimes committed by the most senior Khmer Rouge officials during the period of Khmer Rouge rule of 1975–1979. The judges were sworn in early July 2006.Vietnamese

Vietnamese may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Vietnam, a country in Southeast Asia

** A citizen of Vietnam. See Demographics of Vietnam.

* Vietnamese people, or Kinh people, a Southeast Asian ethnic group native to Vietnam

** Overse ...

and Cham

Cham or CHAM may refer to:

Ethnicities and languages

*Chams, people in Vietnam and Cambodia

**Cham language, the language of the Cham people

***Cham script

*** Cham (Unicode block), a block of Unicode characters of the Cham script

*Cham Albania ...

minorities, which is estimated to make up tens of thousand killings and possibly moreKang Kek Iew

Kang Kek Iew, also spelled Kaing Guek Eav ( km, កាំង ហ្គេកអ៊ាវ, ; 17 November 1942 – 2 September 2020), ''nom de guerre'' Comrade Duch ( km, មិត្តឌុច, ) or Hang Pin, was a Cambodian convicted war ...

was formally charged with a war crime and crimes against humanity and detained by the Tribunal on 31 July 2007. He was indicted on charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity on 12 August 2008.Khieu Samphan

Khieu Samphan ( km, ខៀវ សំផន; born 28 July 1931) is a Cambodian former communist politician and economist who was the chairman of the state presidium of Democratic Kampuchea (Cambodia) from 1976 until 1979. As such, he served as ...

, a former head of state, who was indicted on charges of genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and several other crimes under Cambodian law on 15 September 2010. He was transferred into the custody of the ECCC on 19 September 2007. His trial began on 27 June 2011.Ieng Sary

Ieng Sary ( km, អៀង សារី; 24 October 1925 – 14 March 2013) was a Cambodian politician who was the co-founder and senior member of the Khmer Rouge. He was a member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Kampuchea le ...

, a former foreign minister, who was indicted on charges of genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and several other crimes under Cambodian law on 15 September 2010. He was transferred into the custody of the ECCC on 12 November 2007. His trial started on 27 June 2011, and ended with his death on 14 March 2013. He was never convicted.[

]

By the International Criminal Court

Since 2002, the International Criminal Court can exercise its jurisdiction if national courts are unwilling or unable to investigate or prosecute genocide, thus being a "court of last resort," leaving the primary responsibility to exercise jurisdiction over alleged criminals to individual states. Due to the United States concerns over the ICC, the United States prefers to continue to use specially convened international tribunals for such investigations and potential prosecutions.

Darfur, Sudan

There has been much debate over categorizing the situation in Darfur as genocide. The ongoing conflict in Darfur, Sudan, which started in 2003, was declared a "genocide" by

There has been much debate over categorizing the situation in Darfur as genocide. The ongoing conflict in Darfur, Sudan, which started in 2003, was declared a "genocide" by United States Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State. The office holder is one of the highest ranking members of the president's Ca ...

Colin Powell on 9 September 2004 in testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee

The United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations is a standing committee of the U.S. Senate charged with leading foreign-policy legislation and debate in the Senate. It is generally responsible for overseeing and funding foreign aid p ...

. Since that time however, no other permanent member of the UN Security Council has done so. In fact, in January 2005, an International Commission of Inquiry on Darfur, authorized by UN Security Council Resolution 1564

United Nations Security Council Resolution 1564, adopted on 18 September 2004, after recalling resolutions 1502 (2003), 1547 (2004) and 1556 (2004), the Council threatened the imposition of sanctions against Sudan if it failed to comply with its ...

of 2004, issued a report to the Secretary-General stating that "the Government of Sudan has not pursued a policy of genocide."[ , 25 January 2005, at 4] Nevertheless, the Commission cautioned that "The conclusion that no genocidal policy has been pursued and implemented in Darfur by the Government authorities, directly or through the militias under their control, should not be taken in any way as detracting from the gravity of the crimes perpetrated in that region. International offences such as the crimes against humanity and war crimes that have been committed in Darfur may be no less serious and heinous than genocide."International Criminal Court

The International Criminal Court (ICC or ICCt) is an intergovernmental organization and international tribunal seated in The Hague, Netherlands. It is the first and only permanent international court with jurisdiction to prosecute individuals f ...

(ICC), filed ten charges of war crimes against Sudan's President Omar al-Bashir: three counts of genocide, five of crimes against humanity and two of murder. The ICC's prosecutors claimed that al-Bashir "masterminded and implemented a plan to destroy in substantial part" three tribal groups in Darfur because of their ethnicity.

On 4 March 2009, the ICC issued a warrant of arrest for Omar Al Bashir, President of Sudan as the ICC Pre-Trial Chamber I concluded that his position as head of state does not grant him immunity against prosecution before the ICC. The warrant was for war crimes and crimes against humanity. It did not include the crime of genocide because the majority of the Chamber did not find that the prosecutors had provided enough evidence to include such a charge. Later the decision was changed by the Appeals Panel and after issuing the second decision, charges against Omar al-Bashir include three counts of genocide.

Examples

The concept of genocide can be applied to historical events. The preamble of the

The concept of genocide can be applied to historical events. The preamble of the CPPCG

The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG), or the Genocide Convention, is an international treaty that criminalizes genocide and obligates state parties to pursue the enforcement of its prohibition. It was ...

states that "at all periods of history genocide has inflicted great losses on humanity." Revisionist attempts to challenge or affirm claims of genocide are illegal in some countries. Several European countries ban the denial of the Holocaust and the denial of the Armenian genocide, while in Turkey referring to the Armenian genocide, Greek genocide, and ''Sayfo

The Sayfo or the Seyfo (; see below), also known as the Assyrian genocide, was the mass slaughter and deportation of Assyrian / Syriac Christians in southeastern Anatolia and Persia's Azerbaijan province by Ottoman forces and some Kurdish t ...

'', and to the period of mass starvation during the Great Famine of Mount Lebanon

The Great Famine of Mount Lebanon (1915–1918) ( syc, ܟܦܢܐ, lit=Starvation, translit=Kafno; ar, مجاعة لبنان, translit=Majā'at Lubnān; tr, Lübnan Dağı'nın Büyük Kıtlığı) was a period of mass starvation during World War ...

affecting Maronites, as genocides may be prosecuted under Article 301.

Historian William Rubinstein argues that the origin of 20th-century genocides can be traced back to the collapse of the elite structure and normal modes of government in parts of Europe following World War I, commenting:

According to Esther Brito, the way in which states commit genocide has evolved in the 21st century and genocidal campaigns have attempted to circumvent international systems designed to prevent, mitigate, and prosecute genocide by adjusting the duration, intensity, and methodology of the genocide. Brito states that modern genocides often happen on a much longer time scale than traditional ones - taking years or decades - and that instead of traditional methods of beatings and executions less directly fatal tactics are used but with the same effect. Brito described the contemporary plights of the Rohingya

The Rohingya people () are a stateless Indo-Aryan ethnic group who predominantly follow Islam and reside in Rakhine State, Myanmar (previously known as Burma). Before the Rohingya genocide in 2017, when over 740,000 fled to Bangladesh, an ...

and Uyghurs

The Uyghurs; ; ; ; zh, s=, t=, p=Wéiwú'ěr, IPA: ( ), alternatively spelled Uighurs, Uygurs or Uigurs, are a Turkic ethnic group originating from and culturally affiliated with the general region of Central and East Asia. The Uyghur ...

as examples of this newer form of genocide. The abuses against West Papuans

West Papua ( id, Papua Barat), formerly Irian Jaya Barat (West Irian), is a province of Indonesia. It covers the two western peninsulas of the island of New Guinea, the eastern half of the Bird's Head Peninsula (or Doberai Peninsula) and the ...

in Indonesia have also been described as a slow-motion genocide.

Stages, risk factors, and prevention

Study of the risk factors and prevention of genocide was underway before the 1982 International Conference on the Holocaust and Genocide during which multiple papers on the subject were presented. In 1996 Gregory Stanton

Gregory H. Stanton is the former Research Professor in Genocide Studies and Prevention at the George Mason University in Fairfax County, Virginia, United States. He is best known for his work in the area of genocide studies. He is the founder a ...

, the president of Genocide Watch

Gregory H. Stanton is the former Research Professor in Genocide Studies and Prevention at the George Mason University in Fairfax County, Virginia, United States. He is best known for his work in the area of genocide studies. He is the founder a ...

, presented a briefing paper called " The 8 Stages of Genocide" at the United States Department of State

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an United States federal executive departments, executive department of the Federal government of the United States, U.S. federal government responsible for the country's fore ...

.Gregory Stanton

Gregory H. Stanton is the former Research Professor in Genocide Studies and Prevention at the George Mason University in Fairfax County, Virginia, United States. He is best known for his work in the area of genocide studies. He is the founder a ...

The 8 Stages of Genocide

Genocide Watch, 1996Dirk Moses

Anthony Dirk Moses (born 1967) is an Australian scholar who researches various aspects of genocide. In 2022 he became the Anne and Bernard Spitzer Professor of Political Science at the City College of New York, after having been the Frank Porter ...

criticised genocide studies due to its "rather poor record of ending genocide".

See also

* Outline of Genocide studies

* Allport's Scale

Allport's Scale is a measure of the manifestation of prejudice in a society. It is also referred to as Allport's Scale of Prejudice and Discrimination or Allport's Scale of Prejudice. It was devised by psychologist Gordon Allport in 1954.

The sc ...

* Countervalue

* Cultural genocide

Cultural genocide or cultural cleansing is a concept which was proposed by lawyer Raphael Lemkin in 1944 as a component of genocide. Though the precise definition of ''cultural genocide'' remains contested, the Armenian Genocide Museum defines i ...

* Death squad

* Democide

* Ethnic cleansing

* Gendercide

Gendercide is the systematic killing of members of a specific gender. The term is related to the general concepts of assault and murder against victims due to their gender, with violence against women and men being problems dealt with by human r ...

* Genocide education

* Genocide of indigenous peoples

The genocide of indigenous peoples, colonial genocide, or settler genocide is elimination of entire communities of indigenous peoples as part of colonialism. Genocide of the native population is especially likely in cases of settler colonialis ...

* Mass atrocity crimes

An atrocity crime is a violation of international criminal law that falls under the historically three legally defined international crimes of genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. Ethnic cleansing is widely regarded as a fourth mas ...

* Omnicide

* Policide

* Political cleansing of population

Political cleansing of population is eliminating categories of people in specific areas for political reasons. The means may vary from forced migration to genocide.

Politicide

Politicide is the deliberate physical destruction or elimination o ...

* Religious cleansing

* Utilitarian genocide

Research

* Center for the Study of Genocide and Human Rights

* International Association of Genocide Scholars

The International Association of Genocide Scholars (IAGS) is an international non-partisan organization that seeks to further research and teaching about the nature, causes, and consequences of genocide, including the Armenian genocide, the Holoca ...

References

Further reading

Articles

* (in Spanish) Aizenstatd, Najman Alexander. "Origen y Evolución del Concepto de Genocidio". Vol. 25 Revista de Derecho de la Universidad Francisco Marroquín 11 (2007).

* (in Spanish) Marco, Jorge. "Genocidio y Genocide Studies: Definiciones y debates", en: Aróstegui, Julio, Marco, Jorge y Gómez Bravo, Gutmaro (coord.): "De Genocidios, Holocaustos, Exterminios...", ''Hispania Nova'', 10 (2012). Véas

* Krain, M. (1997). "State-Sponsored Mass Murder: A Study of the Onset and Severity of Genocides and Politicides." Journal of Conflict Resolution 41(3): 331–360.

Books

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

* Lewy, Guenter (2012). ''Essays on Genocide and Humanitarian Intervention''. University of Utah Press. .

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

* Schmid, A. P. (1991). Repression, State Terrorism, and Genocide: Conceptual Clarifications. State Organized Terror: The Case of Violent Internal Repression. P. T. Bushnell. Boulder, Colorado, USA: Westview Press. 312 p.

*

* ''Overcoming Evil: Genocide, violent conflict and terrorism''. New York: Oxford University Press.

*

*

*

External links

Documents

*

*

*

*

Research institutes, advocacy groups, and other organizations

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

{{authority control

Genocide,

1940s neologisms

International criminal law

Mass murder

Racism

After the Holocaust, which had been perpetrated by

After the Holocaust, which had been perpetrated by  All signatories to the CPPCG are required to prevent and punish acts of genocide, both in peace and wartime, though some barriers make this enforcement difficult. In particular, some of the signatories—namely,

All signatories to the CPPCG are required to prevent and punish acts of genocide, both in peace and wartime, though some barriers make this enforcement difficult. In particular, some of the signatories—namely,  The term ''Bosnian genocide'' is used to refer either to the killings committed by Serb forces in

The term ''Bosnian genocide'' is used to refer either to the killings committed by Serb forces in  The

The  The Khmer Rouge, led by Pol Pot,

The Khmer Rouge, led by Pol Pot,  There has been much debate over categorizing the situation in Darfur as genocide. The ongoing conflict in Darfur, Sudan, which started in 2003, was declared a "genocide" by

There has been much debate over categorizing the situation in Darfur as genocide. The ongoing conflict in Darfur, Sudan, which started in 2003, was declared a "genocide" by  The concept of genocide can be applied to historical events. The preamble of the

The concept of genocide can be applied to historical events. The preamble of the