File:1930s decade montage.png, From left, clockwise: Dorothea Lange

Dorothea Lange (born Dorothea Margaretta Nutzhorn; May 26, 1895 – October 11, 1965) was an American documentary photographer and photojournalist, best known for her Great Depression, Depression-era work for the Farm Security Administratio ...

's photo of the homeless Florence Thompson shows the effects of the Great Depression; due to extreme drought conditions, farms across the south-central United States become dry and the Dust Bowl

The Dust Bowl was a period of severe dust storms that greatly damaged the ecology and agriculture of the American and Canadian prairies during the 1930s. The phenomenon was caused by a combination of both natural factors (severe drought) a ...

spreads; The Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of Japan, 1947 constitu ...

invades China, which eventually leads to the Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific Th ...

. In 1937, Japanese soldiers massacre civilians in Nanking

Nanjing (; , Mandarin pronunciation: ), alternately romanized as Nanking, is the capital of Jiangsu province of the People's Republic of China. It is a sub-provincial city, a megacity, and the second largest city in the East China region. T ...

; aviator Amelia Earhart becomes an American flight icon; German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

dictator

A dictator is a political leader who possesses absolute power. A dictatorship is a state ruled by one dictator or by a small clique. The word originated as the title of a Roman dictator elected by the Roman Senate to rule the republic in tim ...

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

and the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

attempt to establish a New Order of German hegemony

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one State (polity), state over other states. In Ancient Greece (8th BC – AD 6th ), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of the ''hegemon'' city-state over oth ...

in Europe, which culminates in 1939 when Germany invades Poland, leading to the outbreak of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

. The Nazis also persecute Jews in Germany, specifically with Kristallnacht

() or the Night of Broken Glass, also called the November pogrom(s) (german: Novemberpogrome, ), was a pogrom against Jews carried out by the Nazi Party's (SA) paramilitary and (SS) paramilitary forces along with some participation fro ...

in 1938; the '' Hindenburg'' explodes over a small New Jersey airfield, causing 36 deaths and effectively ending commercial airship travel; Mohandas Gandhi walks to the Arabian Sea in the Salt March

The Salt March, also known as the Salt Satyagraha, Dandi March and the Dandi Satyagraha, was an act of nonviolent civil disobedience in colonial India led by Mahatma Gandhi. The twenty-four day march lasted from 12 March to 6 April 1930 as a di ...

of 1930., 410px, thumb

rect 1 1 174 226 Great Depression

rect 177 1 375 121 Dust Bowl

The Dust Bowl was a period of severe dust storms that greatly damaged the ecology and agriculture of the American and Canadian prairies during the 1930s. The phenomenon was caused by a combination of both natural factors (severe drought) a ...

rect 177 124 275 226 Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific Th ...

rect 276 124 375 226 Rape of Nanking

The Nanjing Massacre (, ja, 南京大虐殺, Nankin Daigyakusatsu) or the Rape of Nanjing (formerly romanized as ''Nanking'') was the mass murder of Chinese civilians in Nanjing, the capital of the Republic of China, immediately after the Ba ...

rect 378 1 497 226 Amelia Earhart

rect 1 229 221 353 Salt March

The Salt March, also known as the Salt Satyagraha, Dandi March and the Dandi Satyagraha, was an act of nonviolent civil disobedience in colonial India led by Mahatma Gandhi. The twenty-four day march lasted from 12 March to 6 April 1930 as a di ...

rect 1 357 221 488 Hindenburg disaster

The ''Hindenburg'' disaster was an airship accident that occurred on May 6, 1937, in Manchester Township, New Jersey, United States. The German passenger airship LZ 129 ''Hindenburg'' caught fire and was destroyed during its attemp ...

rect 225 230 359 488 Nazi Invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week afte ...

rect 361 230 497 488 Kristallnacht

() or the Night of Broken Glass, also called the November pogrom(s) (german: Novemberpogrome, ), was a pogrom against Jews carried out by the Nazi Party's (SA) paramilitary and (SS) paramilitary forces along with some participation fro ...

The 1930s (pronounced "nineteen-thirties" and commonly abbreviated as "the '30s" or "the Thirties") was a

decade

A decade () is a period of ten years. Decades may describe any ten-year period, such as those of a person's life, or refer to specific groupings of calendar years.

Usage

Any period of ten years is a "decade". For example, the statement that "du ...

that began on January 1, 1930, and ended on December 31, 1939. In the United States, the

Dust Bowl

The Dust Bowl was a period of severe dust storms that greatly damaged the ecology and agriculture of the American and Canadian prairies during the 1930s. The phenomenon was caused by a combination of both natural factors (severe drought) a ...

led to the nickname the "Dirty Thirties".

The decade was defined by a global economic and political crisis that culminated in the

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

. It saw the collapse of the international financial system, beginning with the

Wall Street Crash of 1929

The Wall Street Crash of 1929, also known as the Great Crash, was a major American stock market crash that occurred in the autumn of 1929. It started in September and ended late in October, when share prices on the New York Stock Exchange coll ...

, the largest

stock market crash

A stock market crash is a sudden dramatic decline of stock prices across a major cross-section of a stock market, resulting in a significant loss of paper wealth. Crashes are driven by panic selling and underlying economic factors. They often foll ...

in American history. The subsequent economic downfall, called the

Great Depression, had traumatic social effects worldwide, leading to widespread

poverty and

unemployment

Unemployment, according to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), is people above a specified age (usually 15) not being in paid employment or self-employment but currently available for work during the refere ...

, especially in the economic superpower of the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

and in

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, which was already struggling with the payment of reparations for the

First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. The

Dust Bowl

The Dust Bowl was a period of severe dust storms that greatly damaged the ecology and agriculture of the American and Canadian prairies during the 1930s. The phenomenon was caused by a combination of both natural factors (severe drought) a ...

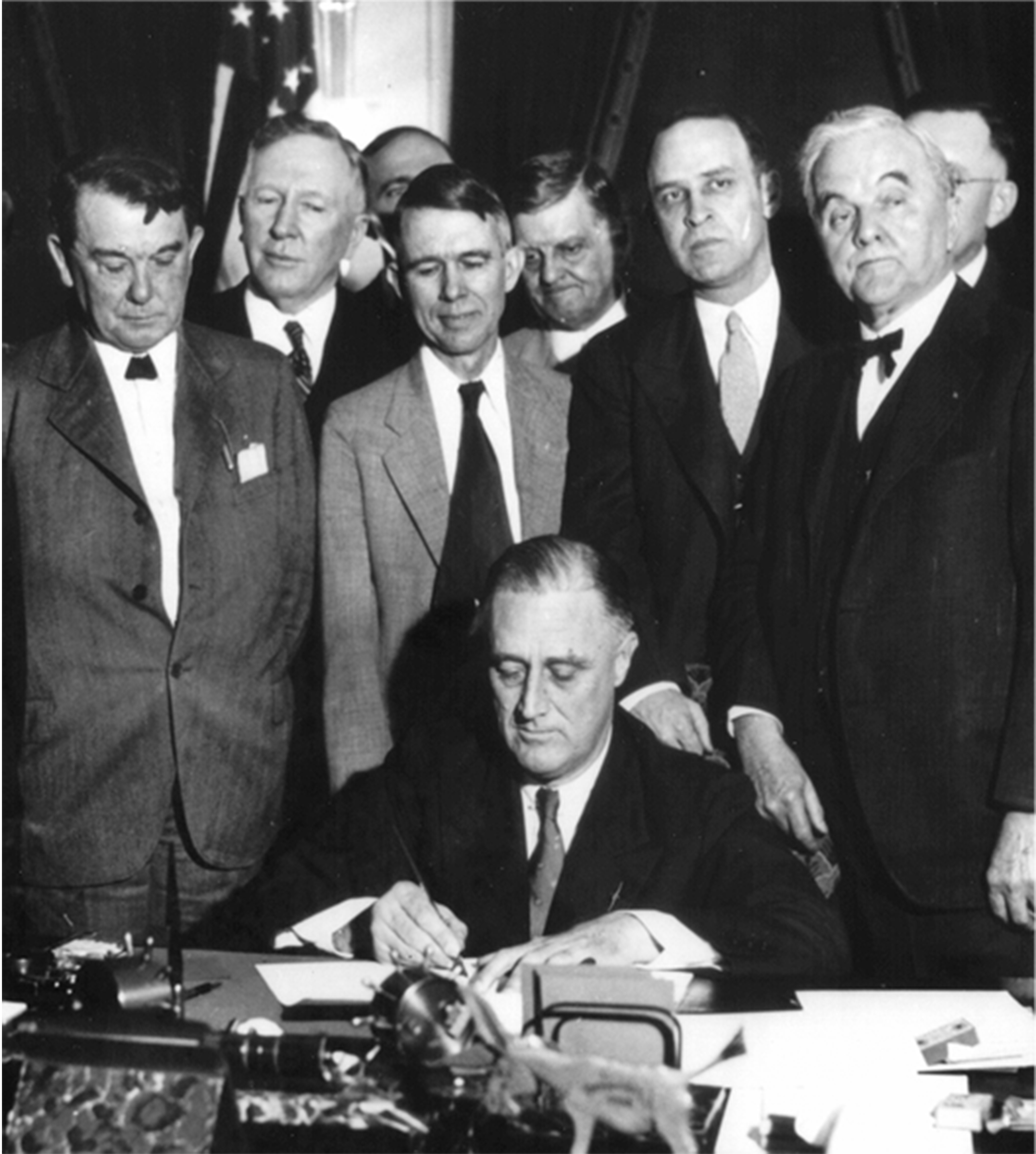

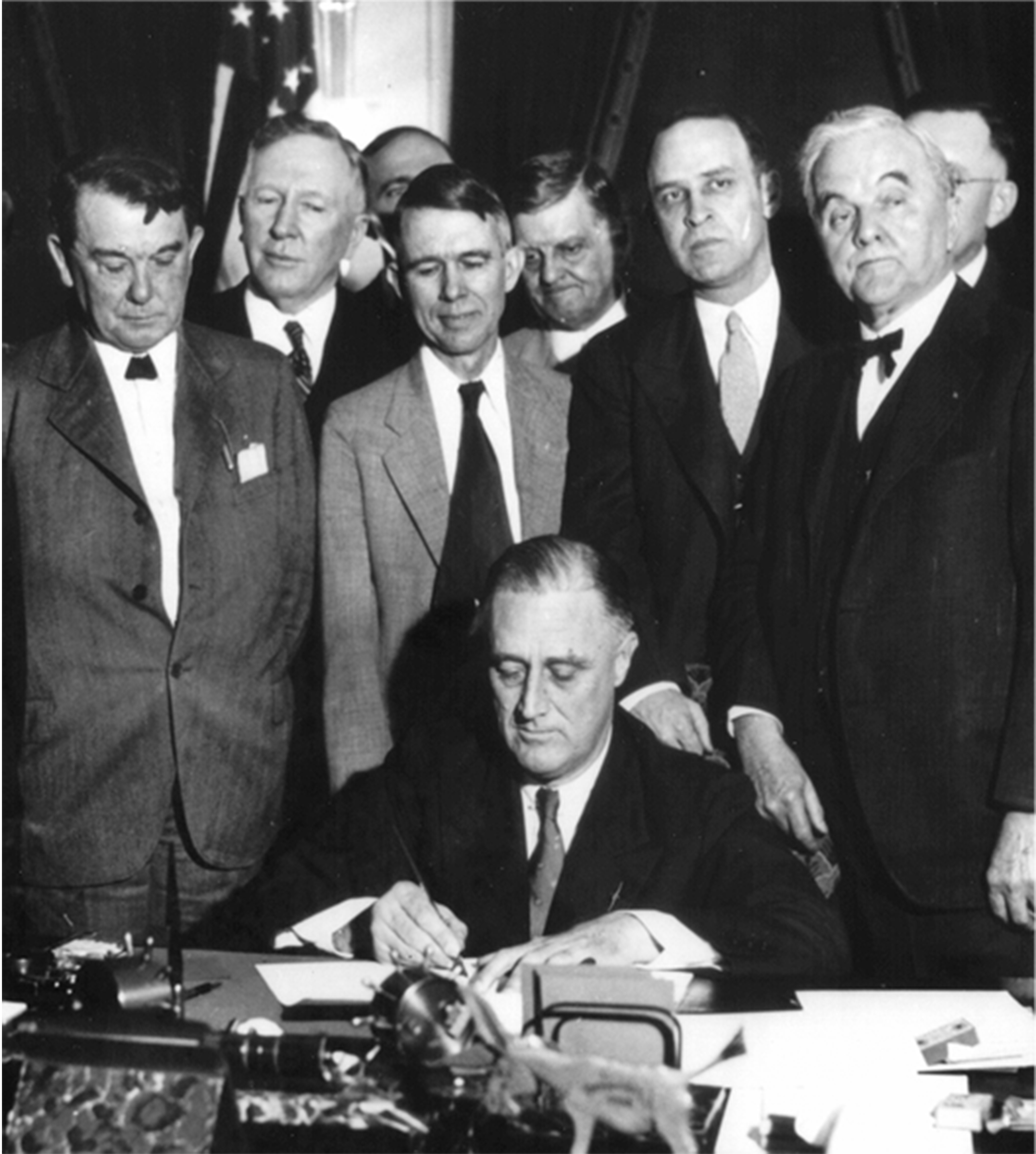

in the United States (which led to the nickname the "Dirty Thirties") exacerbated the scarcity of wealth. U.S. President

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, elected in 1933, introduced a program of broad-scale social reforms and stimulus plans called the

New Deal in response to the crisis. The Soviet's

second five-year plan gave heavy industry top priority, putting the Soviet Union not far behind

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

as one of the major steel-producing countries of the world, while also improving communications.

First-wave feminism

First-wave feminism was a period of feminist activity and thought that occurred during the 19th and early 20th century throughout the Western world. It focused on legal issues, primarily on securing women's right to vote. The term is often used s ...

made advances, with women gaining the right to vote in

South Africa (1930, whites only),

Brazil (1933), and

Cuba (1933). Following the

rise of Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler's rise to power began in the newly established Weimar Republic in September 1919 when Hitler joined the '' Deutsche Arbeiterpartei'' (DAP; German Workers' Party). He rose to a place of prominence in the early years of the party. Be ...

and the emergence of the

NSDAP

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

as the country's sole legal party in 1933, Germany imposed

a series of laws which discriminated against

Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

and other ethnic minorities.

Germany adopted an aggressive foreign policy,

remilitarizing the Rhineland (1936), annexing

Austria (1938) and the

Sudetenland (1938), before

invading Poland (1939) and starting

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

near the end of the decade. Italy likewise continued its already aggressive foreign policy,

defeating the Libyan resistance (1932) and

invading Ethiopia (1936) and

Albania (1939). Both Germany and Italy

became involved in the

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, link ...

, supporting the eventually victorious

Nationalists

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

led by

Francisco Franco against the

Republicans, who were in turn

supported by the Soviet Union. The

Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on m ...

was halted due to the need to confront Japanese imperial ambitions, with the

Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Tai ...

and the

Chinese Communist Party

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), officially the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the founding and sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victorious in the Chinese Civil ...

forming a

Second United Front to fight Japan in the

Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific Th ...

. Lesser conflicts included interstate wars such as the

Colombia–Peru War (1932–1933), the

Chaco War (1932–1935) and the

Saudi–Yemeni War (1934), as well as internal conflicts in

Brazil (1932),

Ecuador (1932),

El Salvador (1932),

Austria (1934) and

Palestine (1936–1939).

Severe famine took place in the major grain-producing areas of the Soviet Union between 1930 and 1933, leading to 5.7 to 8.7 million deaths. Major contributing factors to the famine include: the forced

collectivization in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union introduced the collectivization (russian: Коллективизация) of its agricultural sector between 1928 and 1940 during the ascension of Joseph Stalin. It began during and was part of the first five-year plan. Th ...

of agriculture as a part of the

First Five-Year Plan

The first five-year plan (russian: I пятилетний план, ) of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was a list of economic goals, created by Communist Party General Secretary Joseph Stalin, based on his policy of socialism in ...

, forced grain procurement, combined with rapid industrialization, a decreasing agricultural workforce, and several severe droughts. A

famine of similar scope also took place in China from 1936 to 1937, killing 5 million people. The

1931 China floods caused 422,499–4,000,000 deaths. Major earthquakes of this decade include the

1935 Quetta earthquake

Events

January

* January 7 – Italian premier Benito Mussolini and French Foreign Minister Pierre Laval conclude Franco-Italian Agreement of 1935, an agreement, in which each power agrees not to oppose the other's colonial claims.

* ...

(30,000–60,000 deaths) and the

1939 Erzincan earthquake

The 1939 Erzincan earthquake struck eastern Turkey at with a moment magnitude of 7.8 and a maximum Mercalli intensity of XII (''Extreme''). It was the second most powerful earthquake recorded in Turkey, after the 1668 North Anatolia earthqua ...

(32,700–32,968 deaths).

With the advent of

sound

In physics, sound is a vibration that propagates as an acoustic wave, through a transmission medium such as a gas, liquid or solid.

In human physiology and psychology, sound is the ''reception'' of such waves and their ''perception'' b ...

in 1927, the

musical—the genre best placed to showcase the new technology—took over as the most popular type of film with audiences, with the

animated

Animation is a method by which still figures are manipulated to appear as moving images. In traditional animation, images are drawn or painted by hand on transparent celluloid sheets to be photographed and exhibited on film. Today, most ani ...

musical fantasy film ''

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs

"Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" is a 19th-century German fairy tale that is today known widely across the Western world. The Brothers Grimm published it in 1812 in the first edition of their collection ''Grimms' Fairy Tales'' and numbered as T ...

'' (1937) becoming the highest-grossing film of this decade in terms of gross rentals. In terms of distributor rentals,

''Gone with the Wind'' (1939), an

epic historical romance film

Romance films or movies involve romantic love stories recorded in visual media for broadcast in theatres or on television that focus on passion, emotion, and the affectionate romantic involvement of the main characters. Typically their journey ...

, was the highest-grossing film of this decade and remains the

highest-grossing film (when adjusted for inflation) to this day. Popular novels of this decade include the

historical fiction novels ''

The Good Earth

''The Good Earth'' is a historical fiction novel by Pearl S. Buck published in 1931 that dramatizes family life in a Chinese village in the early 20th century. It is the first book in her ''House of Earth'' trilogy, continued in ''Sons'' (1932) ...

,'' ''

Anthony Adverse

''Anthony Adverse'' is a 1936 American epic film, epic historical drama film directed by Mervyn LeRoy and starring Fredric March and Olivia de Havilland. The screenplay by Sheridan Gibney draws elements of its plot from eight of the nine books i ...

'' and ''

Gone with the Wind

Gone with the Wind most often refers to:

* ''Gone with the Wind'' (novel), a 1936 novel by Margaret Mitchell

* ''Gone with the Wind'' (film), the 1939 adaptation of the novel

Gone with the Wind may also refer to:

Music

* ''Gone with the Wind'' ...

'', all three of which were

best-selling novels in the United States for 2 consecutive years.

Cole Porter was a popular music artist in the 1930s, with 2 of his songs, "

Night and Day" and "

Begin the Beguine

"Begin the Beguine" is a popular song written by Cole Porter. Porter composed the song between Kalabahi, Indonesia, and Fiji during a 1935 Pacific cruise aboard Cunard's ocean liner ''Franconia''. In October 1935, it was introduced by June Kni ...

" becoming No. 1 hits in 1932 and 1935 respectively. The latter song was of the

Swing genre, which had

begun to emerge as the most popular form of music in the United States since 1933.

Politics and wars

Wars

*

Colombia–Peru War

The Colombia–Peru War, also called the Leticia War, was a short-lived armed conflict between Colombia and Peru over territory in the Amazon rainforest that lasted from September 1, 1932 to May 24, 1933. In the end, an agreement was reached to d ...

(September 1, 1932 – May 24, 1933) – fought between the

Republic of Colombia

Colombia (, ; ), officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country in South America with insular regions in North America—near Nicaragua's Caribbean coast—as well as in the Pacific Ocean. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Cari ...

and the

Republic of Peru

*

Chaco War

The Chaco War ( es, link=no, Guerra del Chaco, gn, Cháko Ñorairõ[Bolivia and ](_blank)Paraguay

Paraguay (; ), officially the Republic of Paraguay ( es, República del Paraguay, links=no; gn, Tavakuairetã Paraguái, links=si), is a landlocked country in South America. It is bordered by Argentina to the south and southwest, Brazil to th ...

over the disputed territory of Gran Chaco

The Gran Chaco or Dry Chaco is a sparsely populated, hot and semiarid lowland natural region of the Río de la Plata basin, divided among eastern Bolivia, western Paraguay, northern Argentina, and a portion of the Brazilian states of Mato ...

, resulting in a Paraguayan victory in 1935; an agreement dividing the territory was made in 1938, formally ending the conflict

* Saudi–Yemeni War (March 1934 – May 12, 1934) – fought between Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in Western Asia. It covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and has a land area of about , making it the fifth-largest country in Asia, the second-largest in the A ...

and the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen

* Second Italo-Ethiopian War

The Second Italo-Ethiopian War, also referred to as the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, was a war of aggression which was fought between Italy and Ethiopia from October 1935 to February 1937. In Ethiopia it is often referred to simply as the Itali ...

(October 3, 1935 – February 19, 1937)

* Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific Th ...

(July 7, 1937 – September 9, 1945) – fought between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of Japan, 1947 constitu ...

. It was the largest Asian war of the 20th century, and made up more than 50% of the casualties in the Pacific theater of World War II

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War, was the Theater (warfare), theater of World War II that was fought in Asia, the Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean, and Oceania. It was geographically the largest theater of the war, ...

.

* World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

(September 1, 1939 – September 2, 1945) – global war centered in Europe and the Pacific but involving the majority of the world's countries, including all of the major powers such as Germany, Russia, America, Italy, Japan, France and the United Kingdom.

Internal conflicts

* Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on m ...

(1927–1949) – The ruling Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Tai ...

and the rebel Chinese Communist Party

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), officially the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the founding and sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victorious in the Chinese Civil ...

fought a civil war for control of China. The Communists consolidated territory in the early 1930s and proclaimed a short-lived Chinese Soviet Republic

The Chinese Soviet Republic (CSR) was an East Asian proto-state in China, proclaimed on 7 November 1931 by Chinese communist leaders Mao Zedong and Zhu De in the early stages of the Chinese Civil War. The discontiguous territories of the ...

that collapsed upon Kuomintang attacks, forcing a mass retreat known as the Long March

The Long March (, lit. ''Long Expedition'') was a military retreat undertaken by the Red Army of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the forerunner of the People's Liberation Army, to evade the pursuit of the National Army of the Chinese ...

. The Kuomintang and Communists attempted to put away their differences after 1937 to fight the Japanese invasion of China

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific Th ...

, but intermittent clashes continued through the remainder of the 1930s. Even with some clashes they all fought the Japanese.

* Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, link ...

(July 17, 1936 – April 1, 1939) – Germany and Italy backed the anti-communist Falange

The Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista (FET y de las JONS; ), frequently shortened to just "FET", was the sole legal party of the Francoist regime in Spain. It was created by General Francisco ...

forces of Francisco Franco. The Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

and international communist parties (see Abraham Lincoln Brigade

The Abraham Lincoln Brigade ( es, Brigada Abraham Lincoln), officially the XV International Brigade (''XV Brigada Internacional''), was a mixed brigade that fought for the Spanish Republic in the Spanish Civil War as a part of the Internation ...

) backed the left-wing republican faction in the war. The war ended in April 1939 with Franco's nationalist forces defeating the republican forces. Franco became Head of State of Spain and President of Government, and the Republic of Spain gave way to the Spanish State, an authoritarian dictatorship

A dictatorship is a form of government which is characterized by a leader, or a group of leaders, which holds governmental powers with few to no limitations on them. The leader of a dictatorship is called a dictator. Politics in a dictatorship a ...

.

* Castellammarese War (1929 – September 10, 1931) – Italian-American criminal organizations engaged in a gang war for control of the American Mafia

"Mafia" is an informal term that is used to describe criminal organizations that bear a strong similarity to the original “Mafia”, the Sicilian Mafia and Italian Mafia. The central activity of such an organization would be the arbitration of d ...

on the East Coast of the United States.

Major political changes

Germany – Rise of Nazism

* The NSDAP

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

(Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

) under Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

wins the German federal election, March 1933

Federal elections were held in Germany on 5 March 1933, after the Nazis lawfully acquired power pursuant to the terms of Weimar Constitution on 30 January 1933 and just six days after the Reichstag fire. Nazi stormtroopers had unleashed a wide ...

. Hitler becomes Chancellor of Germany. Following the 1934 death in office of Paul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (; abbreviated ; 2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German field marshal and statesman who led the Imperial German Army during World War I and later became President of Germany fr ...

, President of Germany

The president of Germany, officially the Federal President of the Federal Republic of Germany (german: link=no, Bundespräsident der Bundesrepublik Deutschland),The official title within Germany is ', with ' being added in international corres ...

, Hitler's cabinet passes a law proclaiming the presidency vacant and transferring the role and powers of the head of state to Hitler, hereafter known as ''Führer und Reichskanzler

( ; , spelled or ''Fuhrer'' when the umlaut is not available) is a German word meaning "leader" or "guide". As a political title, it is strongly associated with the Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler.

Nazi Germany cultivated the ("leader principl ...

'' (leader and chancellor). The Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is ...

effectively gives way to Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, a Totalitarian

Totalitarianism is a form of government and a political system that prohibits all opposition parties, outlaws individual and group opposition to the state and its claims, and exercises an extremely high if not complete degree of control and reg ...

autocratic

Autocracy is a system of government in which absolute power over a state is concentrated in the hands of one person, whose decisions are subject neither to external legal restraints nor to regularized mechanisms of popular control (except per ...

national socialist

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

dictatorship

A dictatorship is a form of government which is characterized by a leader, or a group of leaders, which holds governmental powers with few to no limitations on them. The leader of a dictatorship is called a dictator. Politics in a dictatorship a ...

committed to repudiating the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

, persecuting and removing Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

and other minorities from German society, expanding Germany's territory, and opposing the spread of communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a ...

.

* Hitler pulls Germany out of the League of Nations, but hosts the 1936 Summer Olympics to show his new Reich to the world as well as the supposed superior athleticism of his Aryan troops/athletes.

* Neville Chamberlain, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As modern ...

(1937–1940), attempts the appeasement of Hitler in hope of avoiding war by allowing the dictator to annex the Sudetenland (the German-speaking regions of Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

) and later signing the Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy. It provided "cession to Germany ...

and promising constituents " Peace for our time". He is ousted in favor of Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

in May 1940, following the German invasion of Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the ...

.

* The assassination of the German diplomat Ernst vom Rath

Ernst Eduard vom Rath (3 June 1909 – 9 November 1938) was a member of the German nobility, a Nazi Party member, and German Foreign Office diplomat. He is mainly remembered for his assassination in Paris in 1938 by a Polish Jewish teenager, ...

by a German-born Polish Jew triggers the ''Kristallnacht

() or the Night of Broken Glass, also called the November pogrom(s) (german: Novemberpogrome, ), was a pogrom against Jews carried out by the Nazi Party's (SA) paramilitary and (SS) paramilitary forces along with some participation fro ...

'' ("Night of Broken Glass") which occurred between 9 and 10 November 1938, carried out by the Hitler Youth

The Hitler Youth (german: Hitlerjugend , often abbreviated as HJ, ) was the youth organisation of the Nazi Party in Germany. Its origins date back to 1922 and it received the name ("Hitler Youth, League of German Worker Youth") in July 1926. ...

, the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one orga ...

, and the SS, during which much of the Jewish population living in Nazi Germany and Austria was attacked – 91 Jews were murdered, and between 25,000 and 30,000 more were arrested and sent to Nazi concentration camps. Some 267 synagogues were destroyed, and thousands of homes and businesses were ransacked. ''Kristallnacht'' also served as the pretext for the wholesale confiscation of firearms from German Jews.

* Germany and Italy pursue territorial expansionist agendas. Germany demands the annexation of the Federal State of Austria

The Federal State of Austria ( de-AT, Bundesstaat Österreich; colloquially known as the , "Corporate State") was a continuation of the First Austrian Republic between 1934 and 1938 when it was a one-party state led by the clerical fascist Fa ...

and of other German-speaking territories in Europe. Between 1935 and 1936, Germany recovers the Saar and re-militarizes the Rhineland

The Rhineland (german: Rheinland; french: Rhénanie; nl, Rijnland; ksh, Rhingland; Latinised name: ''Rhenania'') is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly its middle section.

Term

Historically, the Rhinelands ...

. Italy initially opposes Germany's aims for Austria, but in 1936 the two countries resolve their differences in the aftermath of Italy's diplomatic isolation following the start of the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, and Germany becomes Italy's only remaining ally. Germany and Italy improve relations by forming an alliance against communism in 1936 with the signing of the Anti-Comintern Pact

The Anti-Comintern Pact, officially the Agreement against the Communist International was an anti-Communist pact concluded between Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan on 25 November 1936 and was directed against the Communist International (C ...

. Germany annexes Austria in the Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, en, Annexation of Austria), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into the German Reich on 13 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a " Greater Germany ...

; the annexation of the Sudetenland follows negotiations which result in the Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy. It provided "cession to Germany ...

of 1938. The Italian invasion of Albania

The Italian invasion of Albania (April 7–12, 1939) was a brief military campaign which was launched by the Kingdom of Italy against the Albanian Kingdom in 1939. The conflict was a result of the imperialistic policies of the Italian prime m ...

in 1939 succeeds in turning the Kingdom of Albania into an Italian protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over most of its int ...

. The vacant Albanian throne is claimed by Victor Emmanuel III of Italy

Victor Emmanuel III (Vittorio Emanuele Ferdinando Maria Gennaro di Savoia; 11 November 1869 – 28 December 1947) was King of Italy from 29 July 1900 until his abdication on 9 May 1946. He also reigned as Emperor of Ethiopia (1936–1941) and ...

.Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

, and finally invades the Second Polish Republic, the last of these events resulting in the outbreak of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

.

* In 1939, several countries of the Americas, including Canada, Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

, and the United States, controversially deny asylum to hundreds of German Jewish refugees on board the MS ''St. Louis'' who are fleeing the Nazi regime's racist agenda of anti-Semitic persecution in Germany. In the end, no country accepts the refugees, and the ship returns to Germany with most of its passengers on board. Some commit suicide, rather than return to Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

.

United States – Combating the Depression

*

* Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

is elected President of the United States in November 1932. Roosevelt initiates a widespread social welfare strategy called the " New Deal" to combat the economic and social devastation of the Great Depression. The economic agenda of the "New Deal" was a radical departure from previous laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( ; from french: laissez faire , ) is an economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies) deriving from special interest groups ...

economics.

Saudi Arabia – Founding

* The Kingdom of Hejaz and Nejd

The Kingdom of Hejaz and Nejd ( ar, مملكة الحجاز ونجد, '), initially the Kingdom of Hejaz and Sultanate of Nejd (, '), was a dual monarchy ruled by Abdulaziz following the victory of the Saudi Sultanate of Nejd over the Hashemite ...

is proclaimed the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in Western Asia. It covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and has a land area of about , making it the fifth-largest country in Asia, the second-largest in the A ...

, concluding the country's unification under the rule of Ibn Saud.

Spain – Turmoil and Civil War

* The Republican parties win the local elections

In many parts of the world, local elections take place to select office-holders in local government, such as mayors and councillors. Elections to positions within a city or town are often known as "municipal elections". Their form and conduct vary ...

, and proclaim the Second Republic, kicking out the monarchy of Alfonso XIII of Borbón.

* The Spanish coup of July 1936 against the Republic marks the beginning of the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, link ...

.

Colonization

* The Ethiopian Empire

The Ethiopian Empire (), also formerly known by the exonym Abyssinia, or just simply known as Ethiopia (; Amharic and Tigrinya: ኢትዮጵያ , , Oromo: Itoophiyaa, Somali: Itoobiya, Afar: ''Itiyoophiyaa''), was an empire that histori ...

is invaded by the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia was proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to an institutional referendum to abandon the monarchy and f ...

during the Second Italo-Abyssinian War from 1935 to 1936. The occupied territory merges with Eritrea and Italian Somaliland

Italian Somalia ( it, Somalia Italiana; ar, الصومال الإيطالي, Al-Sumal Al-Italiy; so, Dhulka Talyaaniga ee Soomaalida), was a protectorate and later colony of the Kingdom of Italy in present-day Somalia. Ruled in the 19th centu ...

into the colony of Italian East Africa

Italian East Africa ( it, Africa Orientale Italiana, AOI) was an Italian colony in the Horn of Africa. It was formed in 1936 through the merger of Italian Somalia, Italian Eritrea, and the newly occupied Ethiopian Empire, conquered in the S ...

.

* The Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of Japan, 1947 constitu ...

captures Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer M ...

in 1931, creating the puppet state

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside power and subject to its orders.Compare: Puppet states have nominal sove ...

of Manchukuo. A puppet government was created, with Puyi

Aisin-Gioro Puyi (; 7 February 1906 – 17 October 1967), courtesy name Yaozhi (曜之), was the last emperor of China as the eleventh and final Qing dynasty monarch. He became emperor at the age of two in 1908, but was forced to abdicate on 1 ...

, the last Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-spea ...

Emperor of China

''Huangdi'' (), translated into English as Emperor, was the superlative title held by monarchs of China who ruled various imperial regimes in Chinese history. In traditional Chinese political theory, the emperor was considered the Son of Heav ...

, installed as the nominal regent and emperor.

Decolonization and independence

* In March 1930 Mohandas Gandhi leads the non-violent Satyagraha movement in the Declaration of the Independence of India

The declaration of Purna Swaraj was made because the youth of India and many leaders of INC were not satisfied with the Dominion, Dominion Status. The word Purna Swaraj was derived , or Declaration of the Independence of India, it was promulg ...

and the Salt March

The Salt March, also known as the Salt Satyagraha, Dandi March and the Dandi Satyagraha, was an act of nonviolent civil disobedience in colonial India led by Mahatma Gandhi. The twenty-four day march lasted from 12 March to 6 April 1930 as a di ...

.

* The Government of India Act 1935 creates new directly elected bodies, although with a limited franchise, and increases the autonomy of the Presidencies and provinces of British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

.

Other prominent political events

*The Great Depression seriously affects the economic, political, and social aspects of society across the world.

*The League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

collapses as countries like Germany, the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia was proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to an institutional referendum to abandon the monarchy and f ...

, and the Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of Japan, 1947 constitu ...

abdicate the League.

Europe

* In 1930,

* In 1930, Miguel Primo de Rivera

Miguel Primo de Rivera y Orbaneja, 2nd Marquess of Estella (8 January 1870 – 16 March 1930), was a dictator, aristocrat, and military officer who served as Prime Minister of Spain from 1923 to 1930 during Spain's Restoration era. He deepl ...

, Prime Minister of Spain

The prime minister of Spain, officially president of the Government ( es, link=no, Presidente del Gobierno), is the head of government of Spain. The office was established in its current form by the Constitution of Spain, Constitution of 1978 a ...

and head of a military dictatorship is forced to resign in response to a financial crisis (part of the Great Depression). Alfonso XIII of Spain, who had previously backed the dictatorship, attempts to return gradually to the previous system and restore his prestige. This failed utterly, as the King was considered a supporter of the dictatorship, and more and more political forces called for the establishment of a republic. In 1931, republican and socialist parties won a major victory in the local elections, while the monarchists were in decline. Street riots ensued, calling for the removal of the monarchy. The Spanish Army declared that they would not defend the King. Alfonso flees the country, effectively abdicating and ending the Bourbon Restoration phase which had started in the 1870s. A Second Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931, after the deposition of King Alfonso XIII, and was dissolved on 1 ...

emerges.

* In the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

, agricultural collectivization and rapid industrialization take place. Millions died during the Holodomor.

* More than 25 million people migrate to cities in the Soviet Union.

* Anglo-German Naval Agreement

The Anglo-German Naval Agreement (AGNA) of 18 June 1935 was a naval agreement between the United Kingdom and Germany regulating the size of the '' Kriegsmarine'' in relation to the Royal Navy.

The Anglo-German Naval Agreement fixed a ratio whe ...

is signed in 1935, removing the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

' level of limitation on the size of the '' Kriegsmarine'' (navy). The agreement allows Germany to build a larger naval force.

* Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera (, ; first registered as George de Valero; changed some time before 1901 to Edward de Valera; 14 October 1882 – 29 August 1975) was a prominent Irish statesman and political leader. He served several terms as head of govern ...

introduces a new constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princ ...

for the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State ( ga, Saorstát Éireann, , ; 6 December 192229 December 1937) was a state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-year Irish War of Independence between ...

in 1937, effectively ending its status as a British Dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 1926 Im ...

.

* The "Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secret ...

" of " Old Bolsheviks" from the Communist Party of the Soviet Union takes place from 1936 to 1938, as ordered by Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

leader Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

, resulting in hundreds of thousands of people being killed. This purge was due to mistrust and political differences, as well as the massive drop in Grain produce. This was due to the method of collectivization in Russia. The Soviet Union produced 16 million lbs of grain less in 1934 compared to 1930. This led to the starvation of millions of Russians.

* The 1937 World's Fair in Paris, France displays the growing political tensions in Europe. The pavilions of the rival countries of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

face each other. Germany at the time was internationally condemned for Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

(its air force) having performed a bombing of the Basque

Basque may refer to:

* Basques, an ethnic group of Spain and France

* Basque language, their language

Places

* Basque Country (greater region), the homeland of the Basque people with parts in both Spain and France

* Basque Country (autonomous co ...

town of Guernica

Guernica (, ), official name (reflecting the Basque language) Gernika (), is a town in the province of Biscay, in the Autonomous Community of the Basque Country, Spain. The town of Guernica is one part (along with neighbouring Lumo) of the mu ...

in Spain during the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, link ...

. Spanish artist Pablo Picasso

Pablo Ruiz Picasso (25 October 1881 – 8 April 1973) was a Spanish painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist and Scenic design, theatre designer who spent most of his adult life in France. One of the most influential artists of the 20th ce ...

depicted the bombing in his masterpiece painting ''Guernica

Guernica (, ), official name (reflecting the Basque language) Gernika (), is a town in the province of Biscay, in the Autonomous Community of the Basque Country, Spain. The town of Guernica is one part (along with neighbouring Lumo) of the mu ...

'' at the World Fair, which was a surrealist

Surrealism is a cultural movement that developed in Europe in the aftermath of World War I in which artists depicted unnerving, illogical scenes and developed techniques to allow the unconscious mind to express itself. Its aim was, according to ...

depiction of the horror of the bombing.

* Referendum in the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State ( ga, Saorstát Éireann, , ; 6 December 192229 December 1937) was a state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-year Irish War of Independence between ...

in December 1937 on whether Ireland should continue to be a constitutional monarchy under King George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death in 1952. He was also the last Emperor of I ...

or to become a republic results in citizens voting in favour of a republic, ending the remains of British sovereignty through monarchial authority over the state.

Africa

* Hertzog of South Africa, whose National Party had won the 1929 election alone after splitting with the Labour Party, received much of the blame for the devastating economic impact of the Depression.

America

* Canada and other countries under the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

sign the Statute of Westminster in 1931, establishing effective parliamentary independence of Canada from the parliament of the United Kingdom.

* United States Marine Corps

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines, is the maritime land force service branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for conducting expeditionary and amphibious operations through combi ...

general Smedley Butler

Major general (United States), Major General Smedley Darlington Butler (July 30, 1881June 21, 1940), nicknamed the "Maverick Marine", was a senior United States Marine Corps Officer (armed forces), officer who fought in the Philippine–American ...

confesses to the U.S. Congress in 1934 that a group of industrialists contacted him, requesting his aid to overthrow the U.S. government of Roosevelt and establish what he claimed would be a fascist regime in the United States.

* 1939 New York World's Fair, the USA displays the pavilions showing art, culture, and technology from the whole world.

* Newfoundland voluntarily returns to British colonial rule in 1934 amid its economic crisis during the Great Depression with the creation of the Commission of Government

The Commission of Government was a non-elected body that governed the Dominion of Newfoundland from 1934 to 1949. Established following the collapse of Newfoundland's economy during the Great Depression, it was dissolved when the dominion beca ...

, a non-elected body.

* Canadian Prime Minister

The prime minister of Canada (french: premier ministre du Canada, link=no) is the head of government of Canada. Under the Westminster system, the prime minister governs with the confidence of a majority the elected House of Commons; as such ...

W. L. Mackenzie King meets with German Führer

( ; , spelled or ''Fuhrer'' when the umlaut is not available) is a German word meaning "leader" or " guide". As a political title, it is strongly associated with the Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler.

Nazi Germany cultivated the ("leader princip ...

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

in 1937 in Berlin. King is the only North American head of government to meet with Hitler.

* Amelia Earhart receives major attention in the 1930s as the first woman pilot to conduct major air flights. Her disappearance for unknown reasons in 1937 while on flight prompted search efforts that failed.

* Southern Great Plains devastated by decades-long Dust Bowl

The Dust Bowl was a period of severe dust storms that greatly damaged the ecology and agriculture of the American and Canadian prairies during the 1930s. The phenomenon was caused by a combination of both natural factors (severe drought) a ...

* In 1932, the Polish Cipher Bureau broke the German Enigma cipher and overcame the ever-growing structural and operating complexities of the evolving Enigma machine with plugboard

A plugboard or control panel (the term used depends on the application area) is an array of jacks or sockets (often called hubs) into which patch cords can be inserted to complete an electrical circuit. Control panels are sometimes used to di ...

, the main German cipher device during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

.

* Board of Temperance Strategy The Anti-Saloon League launched the Board of Temperance Strategy to coordinate resistance to the growing public demand for the repeal of prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term re ...

established in the U.S. to fight repeal of prohibition

The repeal of Prohibition in the United States was accomplished with the passage of the Twenty-first Amendment to the United States Constitution on December 5, 1933.

Background

In 1919, the requisite number of state legislatures ratified the Eig ...

* Getúlio Vargas

Getúlio Dornelles Vargas (; 19 April 1882 – 24 August 1954) was a Brazilian lawyer and politician who served as the 14th and 17th president of Brazil, from 1930 to 1945 and from 1951 to 1954. Due to his long and controversial tenure as Brazi ...

became the President of Brazil after the 1930 coup d'état.

Asia

* Major international media attention follows Mohandas Gandhi's peaceful resistance movement against the British colonial rule in India.

*

* Major international media attention follows Mohandas Gandhi's peaceful resistance movement against the British colonial rule in India.

* Chinese Communist Party

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), officially the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the founding and sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victorious in the Chinese Civil ...

leader Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the founder of the People's Republic of China (PRC) ...

forms the small enclave state called the Chinese Soviet Republic

The Chinese Soviet Republic (CSR) was an East Asian proto-state in China, proclaimed on 7 November 1931 by Chinese communist leaders Mao Zedong and Zhu De in the early stages of the Chinese Civil War. The discontiguous territories of the ...

in 1931.

* The Gandhi–Irwin Pact

The Gandhi–Irwin Pact was a political agreement signed by Mahatma Gandhi and Lord Irwin, Viceroy of India, on 5 March 1931 before the Second Round Table Conference in London. Before this, Irwin, the Viceroy, had announced in October 1929 a ...

is signed by Mohandas Gandhi and Lord Irwin

Edward Frederick Lindley Wood, 1st Earl of Halifax, (16 April 1881 – 23 December 1959), known as The Lord Irwin from 1925 until 1934 and The Viscount Halifax from 1934 until 1944, was a senior British Conservative politician of the 19 ...

, Viceroy of India

The Governor-General of India (1773–1950, from 1858 to 1947 the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, commonly shortened to Viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom and after Indian independence in 19 ...

, on March 5, 1931. Gandhi agrees to end the campaign of civil disobedience being carried out by the Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party but often simply the Congress, is a political party in India with widespread roots. Founded in 1885, it was the first modern nationalist movement to emerge in the British E ...

(INC) in exchange for Irwin accepting the INC to participate in roundtable talks on British colonial policy in India.

* The Government of India Act of 1935 is enacted by the Governor-General of India

The Governor-General of India (1773–1950, from 1858 to 1947 the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, commonly shortened to Viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom and after Indian independence in 1 ...

, separating British Burma to become a separate British possession and also increasing the political autonomy of the remaining presidencies and provinces of British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

.

* Mao Zedong's Chinese communists begin a large retreat from advancing nationalist forces, called the Long March

The Long March (, lit. ''Long Expedition'') was a military retreat undertaken by the Red Army of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the forerunner of the People's Liberation Army, to evade the pursuit of the National Army of the Chinese ...

, beginning in October 1934 and ending in October 1936 and resulting in the collapse of the Chinese Soviet Republic.

* Colonial India's Muslim League Muslim League may refer to:

Political parties Subcontinent

; British India

*All-India Muslim League, Mohammed Ali Jinah, led the demand for the partition of India resulting in the creation of Pakistan.

**Punjab Muslim League, a branch of the organ ...

leader Muhammed Ali Jinnah

Muhammad Ali Jinnah (, ; born Mahomedali Jinnahbhai; 25 December 1876 – 11 September 1948) was a barrister, politician, and the founder of Pakistan. Jinnah served as the leader of the All-India Muslim League from 1913 until the ...

delivers his " Day of Deliverance" speech on December 2, 1939, calling upon Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

to begin to engage in civil disobedience against the British colonial government starting on December 12. Jinnah demands redress and resolution to tensions and violence occurring between Muslims and Hindus

Hindus (; ) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pages 35–37 Historically, the term has also been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for ...

in India. Jinnah's actions are not supported by the largely Hindu-dominated Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party but often simply the Congress, is a political party in India with widespread roots. Founded in 1885, it was the first modern nationalist movement to emerge in the British E ...

whom he had previously closely allied with. The decision is seen as part of an agenda by Jinnah to support the eventual creation of an independent Muslim state called Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 243 million people, and has the world's second-lar ...

from British Empire.

Australia

* Australia and New Zealand sign the Statute of Westminster in 1931 which established legislative equality between the self-governing dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 192 ...

s of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

and the United Kingdom, with a few residual exceptions. The Parliament of Australia

The Parliament of Australia (officially the Federal Parliament, also called the Commonwealth Parliament) is the legislature, legislative branch of the government of Australia. It consists of three elements: the monarch (represented by the ...

and Parliament of New Zealand

The New Zealand Parliament ( mi, Pāremata Aotearoa) is the unicameral legislature of New Zealand, consisting of the King of New Zealand (King-in-Parliament) and the New Zealand House of Representatives. The King is usually represented by hi ...

gain full legislative authority over their territories, no longer sharing powers with the Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative suprema ...

.

Disasters

* The China floods of 1931 are among the deadliest natural disasters ever recorded.

* The

* The 1935 Labor Day Hurricane

The Great Labor Day Hurricane of 1935 was the most intense Atlantic hurricane to make landfall on record by pressure, with winds of up to 185 mph (297 km/h). The fourth tropical cyclone, third tropical storm, second hurricane, and sec ...

makes landfall in the Florida Keys as a Category 5 hurricane and the most intense hurricane to ever make landfall in the Atlantic basin. It caused an estimated $6 million (1935 USD) in damages and killed around 408 people. The hurricane's strong winds and storm surge destroyed nearly all of the structures between Tavernier and Marathon, and the town of Islamorada

Islamorada (also sometimes Islas Morada) is an incorporated village in Monroe County, Florida. It is located directly between Miami and Key West on five islands— Tea Table Key, Lower Matecumbe Key, Upper Matecumbe Key, Windley Key and Plant ...

was obliterated.

* The German dirigible airship

An airship or dirigible balloon is a type of aerostat or lighter-than-air aircraft that can navigate through the air under its own power. Aerostats gain their lift from a lifting gas that is less dense than the surrounding air.

In early ...

'' Hindenburg'' explodes in the sky above Lakehurst, New Jersey

Lakehurst is a borough in Ocean County, New Jersey, United States. As of the 2010 United States Census, the borough's population was 2,654,[hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic ...]

-inflated airships and seriously damages the reputation of the Zeppelin company.

* The New London School in New London, Texas

New London is a city in Rusk County, Texas, United States. The population was 958 at the 2020 census.

New London was originally known as just "London". Because Kimble County Texas had already established a US Post Office station named London, ...

, is destroyed by an explosion, killing in excess of 300 students and teachers (1937).

* The New England Hurricane of 1938

The 1938 New England Hurricane (also referred to as the Great New England Hurricane and the Long Island Express Hurricane) was one of the deadliest and most destructive tropical cyclones to strike Long Island, New York, and New England. The stor ...

, which became a Category 5 hurricane before making landfall as a Category 3. The hurricane was estimated to have caused property losses of US$306 million ($4.72 billion in 2010), killed between 682 and 800 people, and damaged or destroyed over 57,000 homes, including the home of famed actress Katharine Hepburn, who had been staying in her family's Old Saybrook, Connecticut

Old Saybrook is a town in Middlesex County, Connecticut, United States. The population was 10,481 at the 2020 census. It contains the incorporated borough of Fenwick, as well as the census-designated places of Old Saybrook Center and Saybroo ...

, beach home when the hurricane struck.

* The Dust Bowl

The Dust Bowl was a period of severe dust storms that greatly damaged the ecology and agriculture of the American and Canadian prairies during the 1930s. The phenomenon was caused by a combination of both natural factors (severe drought) a ...

, or "Dirty Thirties", a period of severe dust storms

A dust storm, also called a sandstorm, is a meteorological phenomenon common in arid and semi-arid regions. Dust storms arise when a gust front or other strong wind blows loose sand and dirt from a dry surface. Fine particles are trans ...

causing major ecological and agricultural damage to American and Canadian prairie

Prairies are ecosystems considered part of the temperate grasslands, savannas, and shrublands biome by ecologists, based on similar temperate climates, moderate rainfall, and a composition of grasses, herbs, and shrubs, rather than trees, as the ...

lands from 1930 to 1936 (in some areas until 1940). Caused by extreme drought

A drought is defined as drier than normal conditions.Douville, H., K. Raghavan, J. Renwick, R.P. Allan, P.A. Arias, M. Barlow, R. Cerezo-Mota, A. Cherchi, T.Y. Gan, J. Gergis, D. Jiang, A. Khan, W. Pokam Mba, D. Rosenfeld, J. Tierney, an ...

coupled with strong winds and decades of extensive farming without crop rotation

Crop rotation is the practice of growing a series of different types of crops in the same area across a sequence of growing seasons. It reduces reliance on one set of nutrients, pest and weed pressure, and the probability of developing resistant ...

, fallow fields, cover crops, or other techniques to prevent erosion, it affected an estimated of land (traveling as far east as New York and the Atlantic Ocean), caused mass migration (which was the inspiration for the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel ''The Grapes of Wrath

''The Grapes of Wrath'' is an American realist novel written by John Steinbeck and published in 1939. The book won the National Book Award

and Pulitzer Prize for fiction, and it was cited prominently when Steinbeck was awarded the Nobel Priz ...

'' by John Steinbeck), food shortages, multiple deaths and illness from sand inhalation (se

History in Motion

, and a severe reduction in the going wage rate.

* The 1938 Yellow River flood

The 1938 Yellow River flood (, literally "Huayuankou embankment breach incident") was a flood created by the Nationalist Government in central China during the early stage of the Second Sino-Japanese War in an attempt to halt the rapid advance o ...

pours out from Huayuankou, China, inundating of land and killing an estimated 500,000 people.

Assassinations and attempts

Prominent assassinations, targeted killings, and assassination attempts include:

* A plan to kill the English film star Charlie Chaplin, who had arrived in Japan on May 14, 1932, at a reception for him, was planned by activists eager to ingest a nativist Yamato spirit into politics. Chaplin's murder would facilitate war with the U.S., and anxiety in Japan, and lead on to "restoration" in the name of the emperor. However, excepting the death of the prime minister, the coup came to nothing, and the murderers gave themselves in to the police willingly.

* French president

* A plan to kill the English film star Charlie Chaplin, who had arrived in Japan on May 14, 1932, at a reception for him, was planned by activists eager to ingest a nativist Yamato spirit into politics. Chaplin's murder would facilitate war with the U.S., and anxiety in Japan, and lead on to "restoration" in the name of the emperor. However, excepting the death of the prime minister, the coup came to nothing, and the murderers gave themselves in to the police willingly.

* French president Paul Doumer

Joseph Athanase Doumer, commonly known as Paul Doumer (; 22 March 18577 May 1932), was the President of France from 13 June 1931 until his assassination on 7 May 1932.

Biography

Joseph Athanase Doumer was born in Aurillac, in the Cantal ''dépar ...

is assassinated in 1932 by Paul Gorguloff, a mentally unstable Russian émigré.

* U.S. presidential candidate and former Governor of Louisiana Huey Long

Huey Pierce Long Jr. (August 30, 1893September 10, 1935), nicknamed "the Kingfish", was an American politician who served as the 40th governor of Louisiana from 1928 to 1932 and as a United States senator from 1932 until his assassination ...

is assassinated in 1935 by Carl Weiss.

* Engelbert Dollfuss

Engelbert Dollfuß (alternatively: ''Dolfuss'', ; 4 October 1892 – 25 July 1934) was an Austrian clerical fascist politician who served as Chancellor of Austria between 1932 and 1934. Having served as Minister for Forests and Agriculture, he ...

, Chancellor of Austria

The chancellor of the Republic of Austria () is the head of government of the Republic of Austria. The position corresponds to that of Prime Minister in several other parliamentary democracies.

Current officeholder is Karl Nehammer of the Aus ...

and leading figure of Austrofascism

The Fatherland Front ( de-AT, Vaterländische Front, ''VF'') was the right-wing conservative, nationalist and corporatist ruling political organisation of the Federal State of Austria. It claimed to be a nonpartisan

Nonpartisanism is a lack ...