Pontic genocide on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Greek genocide (, ''Genoktonia ton Ellinon''), which included the Pontic genocide, was the systematic killing of the Christian Ottoman Greek population of

The Greek presence in

The Greek presence in

/ref> In another attack against Serenkieuy, in Menemen district, the villagers formed armed resistance groups but only a few managed to survive being outnumbered by the attacking Muslim irregular bands. During the summer of the same year the Special Organization (Teşkilat-ı Mahsusa), assisted by government and army officials, conscripted Greek men of military age from Following similar accords made with

Following similar accords made with

"Greece and Her Refugees"

''Foreign Affairs,'' The Council on Foreign Relations. July 1926. The swap was never completed due to the eruption of

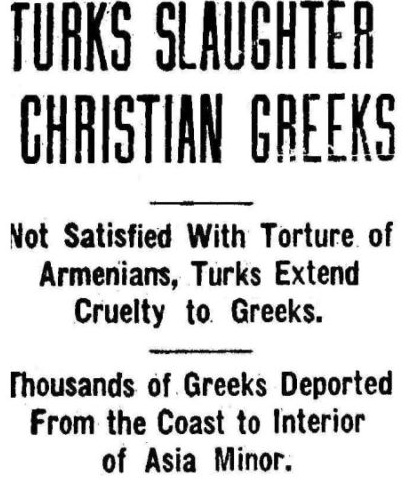

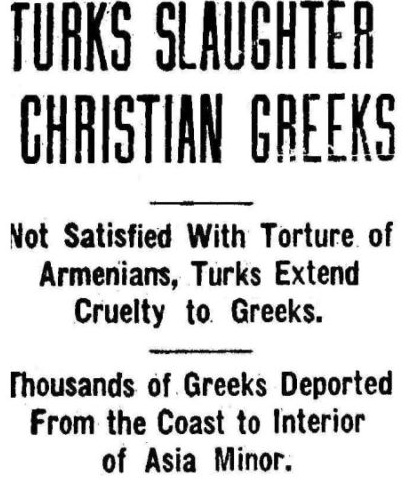

According to a newspaper of the time, in November 1914, Turkish troops destroyed Christian properties and murdered several Christians at

According to a newspaper of the time, in November 1914, Turkish troops destroyed Christian properties and murdered several Christians at  State policy towards Ottoman Greeks changed again in the fall of 1916. With Entente forces occupying

State policy towards Ottoman Greeks changed again in the fall of 1916. With Entente forces occupying

After the Ottoman Empire capitulated on 30 October 1918, it came under the de jure control of the victorious Entente Powers. However, the latter failed to bring the perpetrators of the genocide to justice, although in the

After the Ottoman Empire capitulated on 30 October 1918, it came under the de jure control of the victorious Entente Powers. However, the latter failed to bring the perpetrators of the genocide to justice, although in the

In 1917 a relief organization by the name of the Relief Committee for Greeks of Asia Minor was formed in response to the deportations and massacres of Greeks in the Ottoman Empire. The committee worked in cooperation with the Near East Relief in distributing aid to Ottoman Greeks in Thrace and Asia Minor. The organisation disbanded in the summer of 1921 but Greek relief work was continued by other aid organisations.

In 1917 a relief organization by the name of the Relief Committee for Greeks of Asia Minor was formed in response to the deportations and massacres of Greeks in the Ottoman Empire. The committee worked in cooperation with the Near East Relief in distributing aid to Ottoman Greeks in Thrace and Asia Minor. The organisation disbanded in the summer of 1921 but Greek relief work was continued by other aid organisations.

The accounts describe systematic massacres, rapes and burnings of Greek villages, and attribute intent to Ottoman officials, including the Ottoman Prime Minister

The accounts describe systematic massacres, rapes and burnings of Greek villages, and attribute intent to Ottoman officials, including the Ottoman Prime Minister

Advanced search engine for article and headline archives (subscription necessary for viewing article content).Alexander Westwood and Darren O'Brien

The Australian Institute for Holocaust and Genocide Studies

2006 Australian press also had some coverage of the events.Kateb, Vahe Georges (2003).

Australian Press Coverage of the Armenian Genocide 1915–1923

', University of Wollongong, Graduate School of Journalism Henry Morgenthau, the

According to Benny Morris and

According to Benny Morris and

In December 2007 the

In December 2007 the

The

The

According to Stefan Ihrig, Kemal's "model" remained active for the Nazi movement in

According to Stefan Ihrig, Kemal's "model" remained active for the Nazi movement in

Memorials commemorating the plight of Ottoman Greeks have been erected throughout Greece, as well as in a number of other countries including Australia, Canada, Germany, Sweden, and the United States.

Memorials commemorating the plight of Ottoman Greeks have been erected throughout Greece, as well as in a number of other countries including Australia, Canada, Germany, Sweden, and the United States.

Alt URL

* . * . * .

Bibliography at Greek Genocide Resource Center

*

,''The Atlanta Constitution.'' 17 June 1914. *

Reports Massacres of Greeks in Pontus; Central Council Says They Attend Execution of Prominent Natives for Alleged Rebellion

" ''The New York Times.'' Sunday 6 November 1921. {{DEFAULTSORT:Greek Genocide Greeks from the Ottoman Empire Ethnic cleansing in Europe Ethnic cleansing in Asia Massacres in the Ottoman Empire Ottoman Pontus World War I crimes by the Ottoman Empire Forced marches Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922) Turkish War of Independence History of Greece (1909–1924) Modern history of Turkey Committee of Union and Progress Greece–Turkey relations Anti-Christian sentiment in Asia Anti-Christian sentiment in Europe Anti-Greek sentiment Persecution of Greeks in Turkey Persecution of Christians in the Ottoman Empire Persecution of Greeks in the Ottoman Empire in the 20th century 1910s in the Ottoman Empire 1920s in the Ottoman Empire 1920s in Turkey Massacres of Christians Persecution by Muslims

Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The ...

which was carried out mainly during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and its aftermath (1914–1922) on the basis of their religion and ethnicity. It was perpetrated by the government of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

led by the Three Pashas

The Three Pashas also known as the Young Turk triumvirate or CUP triumvirate consisted of Mehmed Talaat Pasha (1874–1921), the Grand Vizier (prime minister) and Minister of the Interior; Ismail Enver Pasha (1881–1922), the Minister of War ...

and by the Government of the Grand National Assembly

The Government of the Grand National Assembly ( tr, Büyük Millet Meclisi Hükûmeti), self-identified as the State of Turkey () or Turkey (), commonly known as the Ankara Government (),Kemal Kirişci, Gareth M. Winrow: ''The Kurdish Question and ...

led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, against the indigenous Greek population of the Empire. The genocide included massacres, forced deportations involving death march

A death march is a forced march of prisoners of war or other captives or deportees in which individuals are left to die along the way. It is distinguished in this way from simple prisoner transport via foot march. Article 19 of the Geneva Conven ...

es through the Syrian Desert, expulsions, summary executions, and the destruction of Eastern Orthodox

Eastern Orthodoxy, also known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity, is one of the three main branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholicism and Protestantism.

Like the Pentarchy of the first millennium, the mainstream (or " canonical ...

cultural, historical, and religious monuments. Several hundred thousand Ottoman Greeks died during this period. Most of the refugees and survivors fled to Greece (adding over a quarter to the prior population of Greece). Some, especially those in Eastern provinces, took refuge in the neighbouring Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

.

By late 1922, most of the Greeks of Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

had either fled or had been killed. Those remaining were transferred to Greece under the terms of the later 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey

The 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey ( el, Ἡ Ἀνταλλαγή, I Antallagí, ota, مبادله, Mübâdele, tr, Mübadele) stemmed from the "Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations" signed at ...

, which formalized the exodus and barred the return of the refugees. Other ethnic groups were similarly attacked by the Ottoman Empire during this period, including Assyrians and Armenians

Armenians ( hy, հայեր, '' hayer'' ) are an ethnic group native to the Armenian highlands of Western Asia. Armenians constitute the main population of Armenia and the ''de facto'' independent Artsakh. There is a wide-ranging diasp ...

, and some scholars and organizations have recognized these events as part of the same genocidal policy..

The Allies of World War I

The Allies of World War I, Entente (alliance), Entente Powers, or Allied Powers were a coalition of countries led by French Third Republic, France, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom, Russian Empire, Russia, King ...

condemned the Ottoman government–sponsored massacres. In 2007, the International Association of Genocide Scholars

The International Association of Genocide Scholars (IAGS) is an international non-partisan organization that seeks to further research and teaching about the nature, causes, and consequences of genocide, including the Armenian genocide, the Holoca ...

passed a resolution recognising the Ottoman campaign against its Christian minorities, including the Greeks, as genocide. Some other organisations have also passed resolutions recognising the Ottoman campaign against these Christian minorities as genocide, as have the national legislatures of Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders ...

, Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ge ...

, the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

, Sweden, Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ' ...

, the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

and the Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, or simply Czechia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Historically known as Bohemia, it is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the southeast. The ...

.

Background

At the outbreak ofWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

was ethnically diverse, its population included Turks

Turk or Turks may refer to:

Communities and ethnic groups

* Turkic peoples, a collection of ethnic groups who speak Turkic languages

* Turkish people, or the Turks, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

* Turkish citizen, a citizen of the Republic ...

and Azeris

Azerbaijanis (; az, Azərbaycanlılar, ), Azeris ( az, Azərilər, ), or Azerbaijani Turks ( az, Azərbaycan Türkləri, ) are a Turkic people living mainly in northwestern Iran and the Republic of Azerbaijan. They are the second-most nume ...

, as well as groups that had inhabited the region prior to the Ottoman conquest, including Pontic Greeks

The Pontic Greeks ( pnt, Ρωμαίοι, Ρωμίοι, tr, Pontus Rumları or , el, Πόντιοι, or , , ka, პონტოელი ბერძნები, ), also Pontian Greeks or simply Pontians, are an ethnically Greek group i ...

, Caucasus Greeks

The Caucasus Greeks ( el, Έλληνες του Καυκάσου or more commonly , tr, Kafkas Rum), also known as the Greeks of Transcaucasia and Russian Asia Minor, are the ethnic Greeks of the North Caucasus and Transcaucasia in what is no ...

, Cappadocian Greeks, Armenians

Armenians ( hy, հայեր, '' hayer'' ) are an ethnic group native to the Armenian highlands of Western Asia. Armenians constitute the main population of Armenia and the ''de facto'' independent Artsakh. There is a wide-ranging diasp ...

, Kurds ug:كۇردلار

Kurds ( ku, کورد ,Kurd, italic=yes, rtl=yes) or Kurdish people are an Iranian ethnic group native to the mountainous region of Kurdistan in Western Asia, which spans southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, northern Ira ...

, Zazas, Georgians, Circassians

The Circassians (also referred to as Cherkess or Adyghe; Adyghe and Kabardian: Адыгэхэр, romanized: ''Adıgəxər'') are an indigenous Northwest Caucasian ethnic group and nation native to the historical country-region of Circassia ...

, Assyrians, Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

, and Laz people

The Laz people, or Lazi ( lzz, ლაზი ''Lazi''; ka, ლაზი, ''lazi''; or ჭანი, ''ch'ani''; tr, Laz), are an indigenous ethnic group who mainly live in Black Sea coastal regions of Turkey and Georgia. They traditionally speak ...

.

Among the causes of the Turkish campaign against the Greek-speaking Christian population was a fear that they would welcome liberation by the Ottoman Empire's enemies, and a belief among some Turks that to form a modern country in the era of nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

it was necessary to purge from their territories all minorities who could threaten the integrity of an ethnically-based Turkish nation.

According to a German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

attaché, the Ottoman minister of war Ismail Enver

İsmail Enver, better known as Enver Pasha ( ota, اسماعیل انور پاشا; tr, İsmail Enver Paşa; 22 November 1881 – 4 August 1922) was an Ottoman military officer, revolutionary, and convicted war criminal who formed one-third ...

had declared in October 1915 that he wanted to "solve the Greek problem during the war … in the same way he believe he solved the Armenian problem", referring to the Armenian genocide

The Armenian genocide was the systematic destruction of the Armenian people and identity in the Ottoman Empire during World War I. Spearheaded by the ruling Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), it was implemented primarily through t ...

. Germany and the Ottoman Empire were allies immediately before, and during, World War I. By 31 January 1917, the Chancellor of Germany Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg

Theobald Theodor Friedrich Alfred von Bethmann Hollweg (29 November 1856 – 1 January 1921) was a German politician who was the chancellor of the German Empire from 1909 to 1917. He oversaw the German entry into World War I. According to bio ...

reported that:

Origin of the Greek minority

The Greek presence in

The Greek presence in Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

dates at least from the Late Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second prin ...

(1450 BC). The Greek poet Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

lived in the region around 800 BC. The geographer Strabo referred to Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

as the first Greek city in Asia Minor, and numerous ancient Greek figures were natives of Anatolia, including the mathematician Thales

Thales of Miletus ( ; grc-gre, Θαλῆς; ) was a Greek mathematician, astronomer, statesman, and pre-Socratic philosopher from Miletus in Ionia, Asia Minor. He was one of the Seven Sages of Greece. Many, most notably Aristotle, regarded ...

of Miletus (7th century BC), the pre-Socratic philosopher Heraclitus

Heraclitus of Ephesus (; grc-gre, Ἡράκλειτος , "Glory of Hera"; ) was an ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher from the city of Ephesus, which was then part of the Persian Empire.

Little is known of Heraclitus's life. He wrot ...

of Ephesus (6th century BC), and the founder of Cynicism

Cynic or Cynicism may refer to:

Modes of thought

* Cynicism (philosophy), a school of ancient Greek philosophy

* Cynicism (contemporary), modern use of the word for distrust of others' motives

Books

* ''The Cynic'', James Gordon Stuart Grant 1 ...

Diogenes

Diogenes ( ; grc, Διογένης, Diogénēs ), also known as Diogenes the Cynic (, ) or Diogenes of Sinope, was a Greek philosopher and one of the founders of Cynicism (philosophy). He was born in Sinope, an Ionian colony on the Black Sea ...

of Sinope (4th century BC). Greeks referred to the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

as the "Euxinos Pontos" or "hospitable sea" and starting in the eighth century BC they began navigating its shores and settling along its Anatolian coast. The most notable Greek cities of the Black Sea were Trebizond, Sampsounta, Sinope and Heraclea Pontica

__NOTOC__

Heraclea Pontica (; gr, Ἡράκλεια Ποντική, Hērakleia Pontikē), known in Byzantine and later times as Pontoheraclea ( gr, Ποντοηράκλεια, Pontohērakleia), was an ancient city on the coast of Bithynia in Asi ...

.

During the Hellenistic period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

(334 BC – 1st century BC), which followed the conquests of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

, Greek culture and language began to dominate even the interior of Asia Minor. The Hellenization

Hellenization (other British spelling Hellenisation) or Hellenism is the adoption of Greek culture, religion, language and identity by non-Greeks. In the ancient period, colonization often led to the Hellenization of indigenous peoples; in the H ...

of the region accelerated under Roman and early Byzantine rule, and by the early centuries AD the local Indo-European Anatolian languages had become extinct, being replaced by the Koine Greek

Koine Greek (; Koine el, ἡ κοινὴ διάλεκτος, hē koinè diálektos, the common dialect; ), also known as Hellenistic Greek, common Attic, the Alexandrian dialect, Biblical Greek or New Testament Greek, was the common supra-reg ...

language. From this point until the late Middle Ages all of the indigenous inhabitants of Asia Minor practiced Christianity (called Greek Orthodox

The term Greek Orthodox Church ( Greek: Ἑλληνορθόδοξη Ἐκκλησία, ''Ellinorthódoxi Ekklisía'', ) has two meanings. The broader meaning designates "the entire body of Orthodox (Chalcedonian) Christianity, sometimes also cal ...

Christianity after the East–West Schism with the Catholics in 1054) and spoke Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

as their first language.

The resultant Greek culture in Asia Minor flourished during a millennium of rule (4th century – 15th century AD) under the mainly Greek-speaking Eastern Roman Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantin ...

. Those from Asia Minor constituted the bulk of the empire's Greek-speaking Orthodox Christians; thus, many renowned Greek figures during late antiquity, the Middle Ages, and the Renaissance came from Asia Minor, including Saint Nicholas (270–343 AD), rhetorician John Chrysostomos (349–407 AD), Hagia Sophia

Hagia Sophia ( 'Holy Wisdom'; ; ; ), officially the Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque ( tr, Ayasofya-i Kebir Cami-i Şerifi), is a mosque and major cultural and historical site in Istanbul, Turkey. The cathedral was originally built as a Greek Ortho ...

architect Isidore of Miletus

Isidore of Miletus ( el, Ἰσίδωρος ὁ Μιλήσιος; Medieval Greek pronunciation: ; la, Isidorus Miletus) was one of the two main Byzantine Greek architects (Anthemius of Tralles was the other) that Emperor Justinian I commissioned ...

(6th century AD), several imperial dynasties, including the Phokas (10th century) and Komnenos

Komnenos ( gr, Κομνηνός; Latinized Comnenus; plural Komnenoi or Comneni (Κομνηνοί, )) was a Byzantine Greek noble family who ruled the Byzantine Empire from 1081 to 1185, and later, as the Grand Komnenoi (Μεγαλοκομνην� ...

(11th century), and Renaissance scholars George of Trebizond

George of Trebizond ( el, Γεώργιος Τραπεζούντιος; 1395–1486) was a Byzantine Greek philosopher, scholar, and humanist. Life

He was born on the Greek island of Crete (then a Venetian colony known as the Kingdom of Candia), a ...

(1395–1472) and Basilios Bessarion

Bessarion ( el, Βησσαρίων; 2 January 1403 – 18 November 1472) was a Byzantine Greek Renaissance humanist, theologian, Catholic cardinal and one of the famed Greek scholars who contributed to the so-called great revival of letters ...

(1403–1472).

Thus, when the Turkic people

The Turkic peoples are a collection of diverse ethnic groups of West Asia, West, Central Asia, Central, East Asia, East, and North Asia as well as parts of Europe, who speak Turkic languages.. "Turkic peoples, any of various peoples whose memb ...

s began their late medieval conquest of Asia Minor, Byzantine Greek citizens were the largest group of inhabitants there. Even after the Turkic conquests of the interior, the mountainous Black Sea coast of Asia Minor remained the heart of a populous Greek Christian state, the Empire of Trebizond, until its eventual conquest by the Ottoman Turks in 1461, a year after the Ottomans conquered the area of Europe which is now the Greek mainland. Over the next four centuries the Greek natives of Asia Minor gradually became a minority in these lands under the now dominant Turkish culture.

Events

Post-Balkan Wars

Beginning in the spring of 1913, the Ottomans implemented a programme of expulsions and forcible migrations, focusing on Greeks of the Aegean region and eastern Thrace, whose presence in these areas was deemed a threat to national security. The Ottoman government adopted a "dual-track mechanism" allowing it to deny responsibility for and prior knowledge of this campaign of intimidation, emptying Christian villages. The involvement in certain cases of local military and civil functionaries in planning and executing anti-Greek violence and looting led ambassadors of Greece and the Great Powers and thePatriarchate

Patriarchate ( grc, πατριαρχεῖον, ''patriarcheîon'') is an ecclesiological term in Christianity, designating the office and jurisdiction of an ecclesiastical patriarch.

According to Christian tradition three patriarchates were est ...

to address complaints to the Sublime Porte

The Sublime Porte, also known as the Ottoman Porte or High Porte ( ota, باب عالی, Bāb-ı Ālī or ''Babıali'', from ar, باب, bāb, gate and , , ), was a synecdoche for the central government of the Ottoman Empire.

History

The name ...

. In protest to government inaction in the face of these attacks and to the so-called "Muslim boycott" of Greek products that had begun in 1913, the Patriarchate closed Greek churches and schools in June 1914. Responding to international and domestic pressure, Talat Pasha

Mehmed Talaat (1 September 187415 March 1921), commonly known as Talaat Pasha or Talat Pasha,; tr, Talat Paşa, links=no was an Ottoman politician and convicted war criminal of the late Ottoman Empire who served as its leader from 1913 t ...

headed a visit in Thrace in April 1914 and later in the Aegean to investigate reports and try to soothe bilateral tension with Greece. While claiming that he had no involvement or knowledge of these events, Talat met with Kuşçubaşı Eşref, head of the "cleansing" operation in the Aegean littoral, during his tour and advised him to be cautious not to be "visible". Also, after 1913 there were organized boycotts against the Greeks, initiated by the Ottoman Interior Ministry who asked the empire's provinces to start them.

One of the worst attacks of this campaign attack took place in Phocaea

Phocaea or Phokaia (Ancient Greek: Φώκαια, ''Phókaia''; modern-day Foça in Turkey) was an ancient Ionian Greek city on the western coast of Anatolia. Greek colonists from Phocaea founded the colony of Massalia (modern-day Marseille, in ...

(Greek: Φώκαια), on the night of 12 June 1914, a town in western Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The ...

next to Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

, where Turkish irregular troops destroyed the city, killing 50 or 100 civilians and causing its population to flee to Greece. French eyewitness Charles Manciet states that the atrocities he had witnessed at Phocaea were of an organized nature that aimed at circling Christian peasant populations of the region.A Multidimensional Analysis of the Events in Eski Foça (Παλαιά Φώκαια) on the period of Summer 1914-Emre Erol/ref> In another attack against Serenkieuy, in Menemen district, the villagers formed armed resistance groups but only a few managed to survive being outnumbered by the attacking Muslim irregular bands. During the summer of the same year the Special Organization (Teşkilat-ı Mahsusa), assisted by government and army officials, conscripted Greek men of military age from

Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to ...

and western Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The ...

into Labour Battalions in which hundreds of thousands died. These conscripts, after being sent hundreds of miles into the interior of Anatolia, were employed in road-making, building, tunnel excavating and other field work; but their numbers were heavily reduced through privations and ill-treatment and through outright massacre by their Ottoman guards.

Following similar accords made with

Following similar accords made with Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

and Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin and the Balkans. It shares land borders with Hungar ...

, the Ottoman Empire signed a small voluntary population exchange agreement with Greece on 14 November 1913. Another such agreement was signed 1 July 1914 for the exchange of some "Turks" (that is, Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

) of Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders ...

for some Greeks of Aydin and Western Thrace

Western Thrace or West Thrace ( el, �υτικήΘράκη, '' ytikíThráki'' ; tr, Batı Trakya; bg, Западна/Беломорска Тракия, ''Zapadna/Belomorska Trakiya''), also known as Greek Thrace, is a geographic and histori ...

, after the Ottomans had forced these Greeks from their homes in response to the Greek annexation of several islands.Howland, Charles P"Greece and Her Refugees"

''Foreign Affairs,'' The Council on Foreign Relations. July 1926. The swap was never completed due to the eruption of

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. While discussions for population exchanges were still conducted, Special Organization units attacked Greek villages forcing their inhabitants to abandon their homes for Greece, being replaced with Muslim refugees.

The forceful expulsion of Christians of western Anatolia, especially Ottoman Greeks, has many similarities with policy towards the Armenians, as observed by US ambassador Henry Morgenthau and historian Arnold Toynbee. In both cases, certain Ottoman officials, such as Şükrü Kaya

Şükrü Kaya (1883 – 10 January 1959) was a Turkish people, Turkish civil servant and politician, who served as government minister, Minister of Interior and List of Ministers of Foreign Affairs of Turkey, Minister of Foreign affairs in s ...

, Nazım Bey and Mehmed Reshid

Mehmed Reshid ( tr, Mehmet Reşit Şahingiray; 8 February 1873 – 6 February 1919) was an Ottoman physician, official of the Committee of Union and Progress, and governor of the Diyarbekir Vilayet (province) of the Ottoman Empire during World ...

, played a role; Special Organization units and labour battalions were involved; and a dual plan was implemented combining unofficial violence and the cover of state population policy. This policy of persecution and ethnic cleansing was expanded to other parts of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, including Greek communities in Pontus

Pontus or Pontos may refer to:

* Short Latin name for the Pontus Euxinus, the Greek name for the Black Sea (aka the Euxine sea)

* Pontus (mythology), a sea god in Greek mythology

* Pontus (region), on the southern coast of the Black Sea, in modern ...

, Cappadocia

Cappadocia or Capadocia (; tr, Kapadokya), is a historical region in Central Anatolia, Turkey. It largely is in the provinces Nevşehir, Kayseri, Aksaray, Kırşehir, Sivas and Niğde.

According to Herodotus, in the time of the Ionian Re ...

, and Cilicia

Cilicia (); el, Κιλικία, ''Kilikía''; Middle Persian: ''klkyʾy'' (''Klikiyā''); Parthian: ''kylkyʾ'' (''Kilikiyā''); tr, Kilikya). is a geographical region in southern Anatolia in Turkey, extending inland from the northeastern coa ...

.

World War I

According to a newspaper of the time, in November 1914, Turkish troops destroyed Christian properties and murdered several Christians at

According to a newspaper of the time, in November 1914, Turkish troops destroyed Christian properties and murdered several Christians at Trabzon

Trabzon (; Ancient Greek: Tραπεζοῦς (''Trapezous''), Ophitic Pontic Greek: Τραπεζούντα (''Trapezounta''); Georgian: ტრაპიზონი (''Trapizoni'')), historically known as Trebizond in English, is a city on the B ...

. After November 1914 Ottoman policy towards the Greek population shifted; state policy was restricted to the forceful migration to the Anatolian hinterland of Greeks living in coastal areas, particularly the Black Sea region, close to the Turkish-Russian front. This change of policy was due to a German demand for the persecution of Ottoman Greeks to stop, after Eleftherios Venizelos had made this a condition of Greece's neutrality when speaking to the German ambassador in Athens. Venizelos also threatened to undertake a similar campaign against Muslims that were living in Greece if Ottoman policy did not change. While the Ottoman government tried to implement this change in policy, it was unsuccessful and attacks, even murders, continued to occur unpunished by local officials in the provinces, despite repeated instructions in cables sent from the central administration. Arbitrary violence and extortion of money intensified later, providing ammunition for the Venizelists arguing that Greece should join the Entente.

In July 1915 the Greek chargé d'affaires claimed that the deportations "can not be any other issue than an annihilation war against the Greek nation in Turkey and as measures hereof they have been implementing forced conversions to Islam, in obvious aim to, that if after the end of the war there again would be a question of European intervention for the protection of the Christians, there will be as few of them left as possible." According to George W. Rendel of the British Foreign Office, by 1918 "over 500,000 Greeks were deported of whom comparatively few survived". In his memoirs, the United States ambassador to the Ottoman Empire between 1913 and 1916 wrote "Everywhere the Greeks were gathered in groups and, under the so-called protection of Turkish gendarmes, they were transported, the larger part on foot, into the interior. Just how many were scattered in this fashion is not definitely known, the estimates varying anywhere from 200,000 up to 1,000,000."

Despite the shift of policy, the practice of evacuating Greek settlements and relocating the inhabitants was continued, albeit on a limited scale. Relocation was targeted at specific regions that were considered militarily vulnerable, not the whole of the Greek population. As a 1919 Patriarchate account records, the evacuation of many villages was accompanied with looting and murders, while many died as a result of not having been given the time to make the necessary provisions or of being relocated to uninhabitable places.

State policy towards Ottoman Greeks changed again in the fall of 1916. With Entente forces occupying

State policy towards Ottoman Greeks changed again in the fall of 1916. With Entente forces occupying Lesbos

Lesbos or Lesvos ( el, Λέσβος, Lésvos ) is a Greek island located in the northeastern Aegean Sea. It has an area of with approximately of coastline, making it the third largest island in Greece. It is separated from Asia Minor by the nar ...

, Chios

Chios (; el, Χίος, Chíos , traditionally known as Scio in English) is the fifth largest Greek island, situated in the northern Aegean Sea. The island is separated from Turkey by the Chios Strait. Chios is notable for its exports of masti ...

and Samos

Samos (, also ; el, Σάμος ) is a Greece, Greek island in the eastern Aegean Sea, south of Chios, north of Patmos and the Dodecanese, and off the coast of western Turkey, from which it is separated by the -wide Mycale Strait. It is also a se ...

since spring, the Russians advancing in Anatolia and Greece expected to enter the war siding with the Allies, preparations were made for the deportation of Greeks living in border areas. In January 1917 Talat Pasha sent a cable for the deportation of Greeks from the Samsun

Samsun, historically known as Sampsounta ( gr, Σαμψούντα) and Amisos (Ancient Greek: Αμισός), is a city on the north coast of Turkey and is a major Black Sea port. In 2021, Samsun recorded a population of 710,000 people. The cit ...

district "thirty to fifty kilometres inland" taking care for "no assaults on any persons or property". However, the execution of government decrees, which took a systematic form from December 1916, when Behaeddin Shakir Baha al-Din or Bahaa ad-Din ( ar, بهاء الدين, Bahāʾ al-Dīn, splendour of the faith), or various variants like Bahauddin, Bahaeddine or (in Turkish) Bahattin, may refer to:

Surname

* A. K. M. Bahauddin, Bangladeshi politician and the M ...

came to the region, was not conducted as ordered: men were taken in labour battalions, women and children were attacked, villages were looted by Muslim neighbours. As such in March 1917 the population of Ayvalık

Ayvalık () is a seaside town on the northwestern Aegean coast of Turkey. It is a district of Balıkesir province. The town centre is connected to Cunda Island by a causeway and is surrounded by the archipelago of Ayvalık Islands, which fac ...

, a town of c. 30,000 inhabitants on the Aegean coast was forcibly deported to the interior of Anatolia under order by German General Liman von Sanders

Otto Viktor Karl Liman von Sanders (; 17 February 1855 – 22 August 1929) was an Imperial German Army general who served as a military adviser to the Ottoman Army during the First World War. In 1918 he commanded an Ottoman army during the Sin ...

. The operation included death marches

A death march is a forced march of prisoners of war or other captives or deportees in which individuals are left to die along the way. It is distinguished in this way from simple prisoner transport via foot march. Article 19 of the Geneva Conven ...

, looting, torture and massacre against the civilian population. Germanos Karavangelis

Germanos Karavangelis ( el, Γερμανός Καραβαγγέλης, also transliterated as ''Yermanos'' and ''Karavaggelis'' or ''Karavagelis'', 1866–1935) was known for his service as Metropolitan Bishop of Kastoria and later Amaseia, Pon ...

, the bishop of Samsun, reported to the Patriarchate that thirty thousands had been deported to the Ankara region and the convoys of the deportees had been attacked, with many being killed. Talat Pasha ordered an investigation for the looting and destruction of Greek villages by bandits. Later in 1917 instructions were sent to authorize military officials with the control of the operation and to broaden its scope, now including persons from cities in the coastal region. However, in certain areas Greek populations remained undeported.

Greek deportees were sent to live in Greek villages in the inner provinces or, in some case, villages where Armenians were living before being deported. Greek villages evacuated during the war due to military concerns were then resettled with Muslim immigrants and refugees. According to cables sent to the provinces during this time, abandoned movable and non-movable Greek property was not to be liquidated, as that of the Armenians, but "preserved".

On 14 January 1917 Cossva Anckarsvärd, Sweden's Ambassador to Constantinople, sent a dispatch regarding the decision to deport the Ottoman Greeks:

According to Rendel, atrocities such as deportation

Deportation is the expulsion of a person or group of people from a place or country. The term ''expulsion'' is often used as a synonym for deportation, though expulsion is more often used in the context of international law, while deportation ...

s involving death marches, starvation in labour camp

A labor camp (or labour camp, see spelling differences) or work camp is a detention facility where inmates are forced to engage in penal labor as a form of punishment. Labor camps have many common aspects with slavery and with prisons (especi ...

s etc. were referred to as "white massacres". Ottoman official Rafet Bey was active in the genocide of the Greeks and in November 1916, Austrian consul in Samsun

Samsun, historically known as Sampsounta ( gr, Σαμψούντα) and Amisos (Ancient Greek: Αμισός), is a city on the north coast of Turkey and is a major Black Sea port. In 2021, Samsun recorded a population of 710,000 people. The cit ...

, Kwiatkowski, reported that he said to him "We must finish off the Greeks as we did with the Armenians ... today I sent squads to the interior to kill every Greek on sight".

Pontic Greeks responded by forming insurgent groups, which carried weapons salvaged from the battlefields of the Caucasus Campaign of World War I or directly supplied by the Russian army. In 1920, the insurgents reached their peak in regard to manpower numbering 18,000 men. On 15 November 1917, Ozakom delegates agreed to create a unified army composed of ethnically homogeneous units, Greeks were allotted a division consisting of three regiments. The Greek Caucasus Division was thus formed out of ethnic Greeks serving in Russian units stationed in the Caucasus and raw recruits from among the local population including former insurgents. The division took part in numerous engagements against the Ottoman army as well as Muslim and Armenian irregulars, safeguarding the withdrawal of Greek refugees into the Russian held Caucasus, before being disbanded in the aftermath of the Treaty of Poti

The Treaty of Poti was a bilateral agreement between the German Empire and the Democratic Republic of Georgia in which the latter accepted German protection and recognition. The agreement was signed, on 28 May 1918, by General Otto von Lossow for ...

.

Greco-Turkish War

After the Ottoman Empire capitulated on 30 October 1918, it came under the de jure control of the victorious Entente Powers. However, the latter failed to bring the perpetrators of the genocide to justice, although in the

After the Ottoman Empire capitulated on 30 October 1918, it came under the de jure control of the victorious Entente Powers. However, the latter failed to bring the perpetrators of the genocide to justice, although in the Turkish Courts-Martial of 1919–20

Turkish may refer to:

*a Turkic language spoken by the Turks

* of or about Turkey

** Turkish language

*** Turkish alphabet

** Turkish people, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

*** Turkish citizen, a citizen of Turkey

*** Turkish communities and mi ...

a number of leading Ottoman officials were accused of ordering massacres against both Greeks and Armenians. Thus, killings, massacres and deportations continued under the pretext of the national movement of Mustafa Kemal

Mustafa ( ar, مصطفى

, Muṣṭafā) is one of the names of Prophet Muhammad, and the name means "chosen, selected, appointed, preferred", used as an Arabic given name and surname. Mustafa is a common name in the Muslim world.

Given name ...

(later Atatürk).

In an October 1920 report a British officer describes the aftermath of the massacres at İznik

İznik is a town and an administrative district in the Province of Bursa, Turkey. It was historically known as Nicaea ( el, Νίκαια, ''Níkaia''), from which its modern name also derives. The town lies in a fertile basin at the eastern end ...

in north-western Anatolia in which he estimated that at least 100 decomposed mutilated bodies of men, women and children were present in and around a large cave about 300 yards outside the city walls.

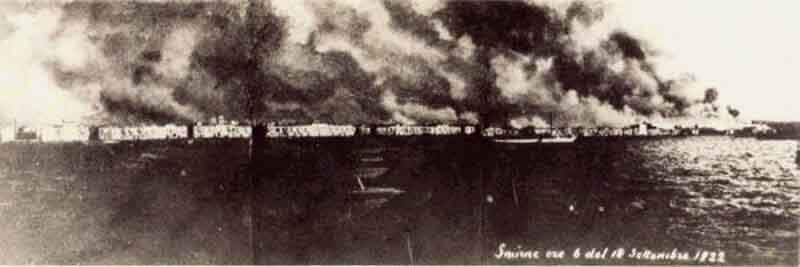

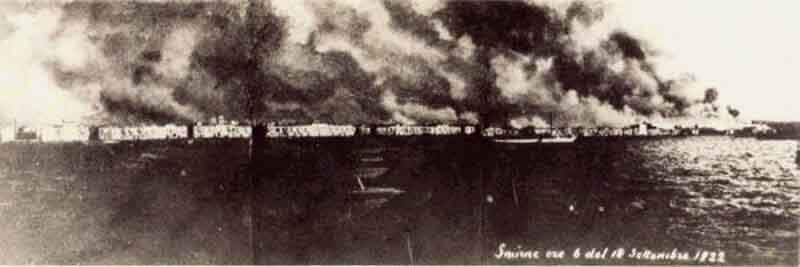

The systematic massacre and deportation of Greeks in Asia Minor, a program which had come into effect in 1914, was a precursor to the atrocities perpetrated by both the Greek and Turkish armies during the Greco-Turkish War, a conflict which followed the Greek landing at Smyrna in May 1919 and continued until the retaking of Smyrna by the Turks and the Great Fire of Smyrna

The burning of Smyrna ( el, Καταστροφή της Σμύρνης, "Smyrna Catastrophe"; tr, 1922 İzmir Yangını, "1922 Izmir Fire"; hy, Զմիւռնիոյ Մեծ Հրդեհ, ''Zmyuṙno Mets Hrdeh'') destroyed much of the port city of ...

in September 1922.Taner Akcam Taner (from Turkish ', "dawn", and ', "man") is usually a Turkish masculine given name and surname.

It may also refer to Taner, a former imperial Chinese commandery.

Given name

* Ahmet Taner Kışlalı (1939−1999), political scientist, au ...

, ''A Shameful Act

''A Shameful Act: The Armenian Genocide and the Question of Turkish Responsibility'' ( tr, İnsan Hakları ve Ermeni Sorunu, İttihat ve Terakki'den Kurtuluş Savaşı'na) is a 1999 book by Taner Akçam about Armenian genocide denial, originally p ...

'', p. 322 Rudolph Rummel estimated the death toll of the fire at 100,000 Greeks and Armenians, who perished in the fire and accompanying massacres. According to Norman M. Naimark "more realistic estimates range between 10,000 to 15,000" for the casualties of the Great Fire of Smyrna. Some 150,000 to 200,000 Greeks were expelled after the fire, while about 30,000 able-bodied Greek and Armenian men were deported to the interior of Asia Minor, most of whom were executed on the way or died under brutal conditions. George W. Rendel of the British Foreign Office noted the massacres and deportations of Greeks during the Greco-Turkish War. According to estimates by Rudolph Rummel, between 213,000 and 368,000 Anatolian Greeks were killed between 1919 and 1922. There were also massacres of Turks carried out by the Hellenic troops during the occupation of western Anatolia from May 1919 to September 1922.

For the massacres that occurred during the Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922, British historian Arnold J. Toynbee wrote that it was the Greek landings that created the Turkish National Movement led by Mustafa Kemal: "The Greeks of 'Pontus' and the Turks of the Greek occupied territories, were in some degree victims of Mr. Venizelos's and Mr. Lloyd George's original miscalculations at Paris."

Relief efforts

In 1917 a relief organization by the name of the Relief Committee for Greeks of Asia Minor was formed in response to the deportations and massacres of Greeks in the Ottoman Empire. The committee worked in cooperation with the Near East Relief in distributing aid to Ottoman Greeks in Thrace and Asia Minor. The organisation disbanded in the summer of 1921 but Greek relief work was continued by other aid organisations.

In 1917 a relief organization by the name of the Relief Committee for Greeks of Asia Minor was formed in response to the deportations and massacres of Greeks in the Ottoman Empire. The committee worked in cooperation with the Near East Relief in distributing aid to Ottoman Greeks in Thrace and Asia Minor. The organisation disbanded in the summer of 1921 but Greek relief work was continued by other aid organisations.

Contemporary accounts

German and Austro-Hungarian diplomats, as well as the 1922 memorandum compiled by British diplomat George W. Rendel on "Turkish Massacres and Persecutions", provided evidence for series of systematic massacres and ethnic cleansing of the Greeks in Asia Minor. The quotes have been attributed to various diplomats, including the German ambassadors Hans Freiherr von Wangenheim and Richard von Kühlmann, the German vice-consul inSamsun

Samsun, historically known as Sampsounta ( gr, Σαμψούντα) and Amisos (Ancient Greek: Αμισός), is a city on the north coast of Turkey and is a major Black Sea port. In 2021, Samsun recorded a population of 710,000 people. The cit ...

Kuchhoff, Austria's ambassador Pallavicini and Samsun consul Ernst von Kwiatkowski, and the Italian unofficial agent in Angora Signor Tuozzi. Other quotes are from clergymen and activists, including the German missionary Johannes Lepsius

Johannes Lepsius (15 December 1858, Potsdam, Germany – 3 February 1926, Meran, Italy) was a German Protestant missionary, Orientalist, and humanist with a special interest in trying to prevent the Armenian genocide in the Ottoman Empire. He ini ...

, and Stanley Hopkins of the Near East Relief. Germany and Austria-Hungary were allied to the Ottoman Empire in World War I.

The accounts describe systematic massacres, rapes and burnings of Greek villages, and attribute intent to Ottoman officials, including the Ottoman Prime Minister

The accounts describe systematic massacres, rapes and burnings of Greek villages, and attribute intent to Ottoman officials, including the Ottoman Prime Minister Mahmud Sevket Pasha

Mahmud Shevket Pasha ( ota, محمود شوكت پاشا, 1856 – 11 June 1913)David Kenneth Fieldhouse: ''Western imperialism in the Middle East 1914-1958''. Oxford University Press, 2006 p.17 was an Ottoman generalissimo and statesman, wh ...

, Rafet Bey, Talat Pasha

Mehmed Talaat (1 September 187415 March 1921), commonly known as Talaat Pasha or Talat Pasha,; tr, Talat Paşa, links=no was an Ottoman politician and convicted war criminal of the late Ottoman Empire who served as its leader from 1913 t ...

and Enver Pasha.

Additionally, ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' and its correspondents made extensive references to the events, recording massacres, deportations, individual killings, rapes, burning of entire Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

villages

A village is a clustered human settlement or community, larger than a hamlet but smaller than a town (although the word is often used to describe both hamlets and smaller towns), with a population typically ranging from a few hundred to ...

, destruction of Greek Orthodox

The term Greek Orthodox Church ( Greek: Ἑλληνορθόδοξη Ἐκκλησία, ''Ellinorthódoxi Ekklisía'', ) has two meanings. The broader meaning designates "the entire body of Orthodox (Chalcedonian) Christianity, sometimes also cal ...

churches and monasteries

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer which ...

, drafts for "Labor Brigades", looting, terrorism and other "atrocities" for Greek, Armenian and also for British and American citizens and government officials.''The New York Times''Advanced search engine for article and headline archives (subscription necessary for viewing article content).Alexander Westwood and Darren O'Brien

The Australian Institute for Holocaust and Genocide Studies

2006 Australian press also had some coverage of the events.Kateb, Vahe Georges (2003).

Australian Press Coverage of the Armenian Genocide 1915–1923

', University of Wollongong, Graduate School of Journalism Henry Morgenthau, the

United States ambassador to the Ottoman Empire

The United States has maintained many high level contacts with Turkey since the 19th century.

Ottoman Empire

Chargé d'Affaires

* George W. Erving (before 1831)

* David Porter (September 13, 1831 – May 23, 1840)

Minister Resident

* David Por ...

from 1913 to 1916, accused the "Turkish government" of a campaign of "outrageous terrorizing, cruel torturing, driving of women into harems, debauchery of innocent girls, the sale of many of them at 80 cents each, the murdering of hundreds of thousands and the deportation to and starvation in the desert of other hundreds of thousands, ndthe destruction of hundreds of villages and many cities", all part of "the willful execution" of a "scheme to annihilate the Armenian, Greek and Syrian Christians of Turkey". However, months prior to the First World War, 100,000 Greeks were deported to Greek islands or the interior which Morgenthau stated, "for the larger part these were bona-fide deportations; that is, the Greek inhabitants were actually removed to new places and were not subjected to wholesale massacre. It was probably the reason that the civilized world did not protest against these deportations".

US Consul-General George Horton, whose account has been criticised by scholars as anti-Turkish, claimed, "One of the cleverest statements circulated by the Turkish propagandists is to the effect that the massacred Christians were as bad as their executioners, that it was '50–50'." On this issue he comments: "Had the Greeks, after the massacres in the Pontus and at Smyrna, massacred all the Turks in Greece, the record would have been 50–50—almost." As an eye-witness, he also praises Greeks for their "conduct ... toward the thousands of Turks residing in Greece, while the ferocious massacres were going on", which, according to his opinion, was "one of the most inspiring and beautiful chapters in all that country's history".

Casualties

According to Benny Morris and

According to Benny Morris and Dror Ze'evi

Dror Ze'evi (born 1953, Haifa) is an Israeli historian who studies political, social and cultural history of the Ottoman Empire, Turkey and the Levant.

Ze'evi's father, , was deputy head of Mossad, and his mother, Galila, is an interior design ...

in '' The Thirty-Year Genocide'', as a result of Ottoman and Turkish state policy, "several hundred thousand Ottoman Greeks had died. Either they were murdered outright or were the intentional victims of hunger, disease, and exposure."

For the whole of the period between 1914 and 1922 and for the whole of Anatolia, there are academic estimates of death toll ranging from 289,000 to 750,000. The figure of 750,000 is suggested by political scientist Adam Jones. Scholar Rudolph Rummel

Rudolph Joseph Rummel (October 21, 1932 – March 2, 2014) was an American political scientist and professor at the Indiana University, Yale University, and University of Hawaiʻi. He spent his career studying data on collective violence and war w ...

compiled various figures from several studies to estimate lower and higher bounds for the death toll between 1914 and 1923. He estimates that 84,000 Greeks were exterminated from 1914 to 1918, and 264,000 from 1919 to 1922. The total number reaching 347,000. Historian Constantine G. Hatzidimitriou writes that "loss of life among Anatolian Greeks during the WWI period and its aftermath was approximately 735,370". Erik Sjöberg states that " tivists tend to inflate the overall total of Ottoman Greek deaths" over what he considers "the cautious estimates between 300,000 to 700,000".

Some contemporary sources claimed different death tolls. The Greek government collected figures together with the Patriarchate to claim that a total of one million people were massacred. A team of American researchers found in the early postwar period that the total number of Greeks killed may approach 900,000 people. Edward Hale Bierstadt, writing in 1924, stated that "According to official testimony, the Turks since 1914 have slaughtered in cold blood 1,500,000 Armenians, and 500,000 Greeks, men women and children, without the slightest provocation." On 4 November 1918, Emanuel Efendi, an Ottoman deputy of Aydin, criticised the ethnic cleansing of the previous government and reported that 550,000 Greeks had been killed in the coastal regions of Anatolia (including the Black Sea coast) and Aegean Islands during the deportations.

According to various sources the Greek death toll in the Pontus region of Anatolia ranges from 300,000 to 360,000. Merrill D. Peterson

Merrill Daniel Peterson (31 March 1921 – 23 September 2009) was a history professor at the University of Virginia and the editor of the prestigious Library of America edition of the selected writings of Thomas Jefferson. Peterson wrote several bo ...

cites the death toll of 360,000 for the Greeks of Pontus. According to George K. Valavanis, "The loss of human life among the Pontian Greeks, since the Great War (World War I) until March 1924, can be estimated at 353,000, as a result of murders, hangings, and from punishment, disease, and other hardships." Valavanis derived this figure from the 1922 record of the Central Pontian Council in Athens based on the ''Black Book'' of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, to which he adds "50,000 new martyrs", which "came to be included in the register by spring 1924".

Aftermath

Article 142 of the 1920Treaty of Sèvres

The Treaty of Sèvres (french: Traité de Sèvres) was a 1920 treaty signed between the Allies of World War I and the Ottoman Empire. The treaty ceded large parts of Ottoman territory to France, the United Kingdom, Greece and Italy, as well ...

, prepared after the first World War, called the Turkish regime "terrorist" and contained provisions "to repair so far as possible the wrongs inflicted on individuals in the course of the massacres perpetrated in Turkey during the war." The Treaty of Sèvres was never ratified by the Turkish government and ultimately was replaced by the Treaty of Lausanne. That treaty was accompanied by a "Declaration of Amnesty", without containing any provision in respect to punishment of war crimes.

In 1923, a population exchange between Greece and Turkey

The 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey ( el, Ἡ Ἀνταλλαγή, I Antallagí, ota, مبادله, Mübâdele, tr, Mübadele) stemmed from the "Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations" signed at ...

resulted in a near-complete ending of the Greek ethnic presence in Turkey and a similar ending of the Turkish ethnic presence in much of Greece. According to the Greek census of 1928, 1,104,216 Ottoman Greeks had reached Greece. It is impossible to know exactly how many Greek inhabitants of Turkey died between 1914 and 1923, and how many ethnic Greeks of Anatolia were expelled to Greece or fled to the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

. Some of the survivors and expelled took refuge in the neighboring Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

(later, Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

). Similar plans for a population exchange had been negotiated earlier, in 1913–1914, between Ottoman and Greek officials during the first stage of the Greek genocide but had been interrupted by the onset of World War I.

In December 1924, ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' reported that 400 tonnes of human bones consigned to manufacturers were transported from Mudania

Mudanya (Mudania, el, τα Μουδανιά, ''ta Moudaniá'' l. (the site of ancient Apamea Myrlea) is a town and district of Bursa Province in the Marmara region of Turkey. It is located on the Gulf of Gemlik, part of the southern coast of t ...

to Marseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Fra ...

, which might be the remains of massacred victims in Asia Minor.

In 1955, the Istanbul Pogrom caused most of the remaining Greek inhabitants of Istanbul to flee the country. Historian Alfred-Maurice de Zayas

Alfred-Maurice de Zayas (born 31 May 1947) is a Cuban-born American lawyer and writer, active in the field of human rights and international law. From 1 May 2012 to 30 April 2018, he served as the first UN Independent Expert on the Promotion o ...

identifies the pogrom as a crime against humanity and he states that the flight and migration of Greeks afterwards corresponds to the "intent to destroy in whole or in part" criteria of the Genocide Convention

The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG), or the Genocide Convention, is an international treaty that criminalizes genocide and obligates state parties to pursue the enforcement of its prohibition. It was ...

.

Genocide recognition

Terminology

The word ''genocide'' was coined in the early 1940s, the era of theHolocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

, by Raphael Lemkin, a Polish lawyer of Jewish descent. In his writings on genocide, Lemkin is known to have detailed the fate of Greeks in Turkey. In August 1946 the ''New York Times'' reported:

The 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide

The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG), or the Genocide Convention, is an international treaty that criminalizes genocide and obligates state parties to pursue the enforcement of its prohibition. It was ...

(CPPCG) was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; french: link=no, Assemblée générale, AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as the main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ of the UN. Curr ...

in December 1948 and came into force in January 1951. It includes a legal definition of genocide.

Before the creation of the term "genocide", the destruction of the Ottoman Greeks was known by Greeks as "the Massacre" (in Greek: ), "the Great Catastrophe" (), or "the Great Tragedy" (). The Ottoman and Kemalist nationalist massacres of the Greeks in Anatolia, constituted genocide under the initial definition and international criminal application of the term, as in the international criminal tribunals authorized by the United Nations.

Academic discussion

International Association of Genocide Scholars

The International Association of Genocide Scholars (IAGS) is an international non-partisan organization that seeks to further research and teaching about the nature, causes, and consequences of genocide, including the Armenian genocide, the Holoca ...

(IAGS) passed a resolution affirming that the 1914–23 campaign against Ottoman Greeks constituted genocide "qualitatively similar" to the Armenian genocide

The Armenian genocide was the systematic destruction of the Armenian people and identity in the Ottoman Empire during World War I. Spearheaded by the ruling Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), it was implemented primarily through t ...

. IAGS President Gregory Stanton

Gregory H. Stanton is the former Research Professor in Genocide Studies and Prevention at the George Mason University in Fairfax County, Virginia, United States. He is best known for his work in the area of genocide studies. He is the founder a ...

urged the Turkish government to finally acknowledge the three genocides: "The history of these genocides is clear, and there is no more excuse for the current Turkish government, which did not itself commit the crimes, to deny the facts." Drafted by Canadian scholar Adam Jones, the resolution was adopted on 1 December 2007 with the support of 83% of all voting IAGS members. Several scholars researching the Armenian genocide, such as Peter Balakian

Peter Balakian, born June 13, 1951, is an American poet, prose writer, and scholar. He is the author of many books including the 2016 Pulitzer prize winning book of poems ''Ozone Journal'', the memoir ''Black Dog of Fate'', winner of the PEN/Alb ...

, Taner Akçam, Richard Hovannisian

Richard Gable Hovannisian ( hy, Ռիչարդ Հովհաննիսյան, born November 9, 1932) is an Armenian American historian and professor emeritus at the University of California, Los Angeles. He is known mainly for his four-volume history o ...

and Robert Melson, however stated that "the issue had to be further researched before a resolution was passed."

Manus Midlarsky notes a disjunction between statements of genocidal intent

Genocidal intent is the '' mens rea'' for the crime of genocide. "Intent to destroy" is one of the elements of the crime of genocide according to the 1948 Genocide Convention. There are some analytic differences between the concept of intent under ...

against the Greeks by Ottoman officials and their actions, pointing to the containment of massacres in selected "sensitive" areas and the large numbers of Greek survivors at the end of the war. Because of cultural and political ties of the Ottoman Greeks with European powers, Midlarsky argues, genocide was "not a viable option for the Ottomans in their case." Taner Akçam refers to contemporary accounts noting the difference in government treatment of Ottoman Greeks and Armenians during WW I and concludes that "despite the increasingly severe wartime policies, in particular for the period between late 1916 and the first months of 1917, the government's treatment of the Greeks – although comparable in some ways to the measures against the Armenians – differed in scope, intent, and motivation."

Some historians, including , , and Andrekos Varnava

Professor Andrekos Varnava is a dual national Cypriot/Australian writer and historian, who is best known for his work confronting controversial moments in modern history and their consequences.

Life and works

Varnava was born in 1979 in Melb ...

argue that the persecution of Greeks was ethnic cleansing or deportation, but not genocide. This is also a position of some Greek mainstream historians; according to Aristide Caratzas this is due to a number of factors, "which range from governmental reticence to criticize Turkey to spilling over into the academic world, to ideological currents promoting a diffuse internationalism cultivated by a network of NGOs, often supported by western governments and western interests". Others, such as Dominik J. Schaller and Jürgen Zimmerer, argue that the "genocidal quality of the murderous campaigns against Greeks" was "obvious". The historians Samuel Totten

Samuel Totten is an American professor of history noted for his scholarship on genocide. Totten was a distinguished professor at the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville where he taught from 1987 to 2012 and served as the chief editor of the jour ...

and Paul R. Bartrop

Paul R. Bartrop (born November 3, 1955) is an Australian historian of the Holocaust and genocide. From August 2012 until December 2020 he was Professor of History and Director of the Center for Judaic, Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Florida Gu ...

, who specialize on the history of genocides, also call it a genocide; so is Alexander Kitroeff. Another scholar who considers it a genocide is Hannibal Travis; he also adds that the widespread attacks by the successive governments of Turkey, on the homes, places of worship, and heritage of minority communities since the 1930s, constitute cultural genocide as well.

Dror Ze'evi

Dror Ze'evi (born 1953, Haifa) is an Israeli historian who studies political, social and cultural history of the Ottoman Empire, Turkey and the Levant.

Ze'evi's father, , was deputy head of Mossad, and his mother, Galila, is an interior design ...

and Benny Morris, authors of ''The Thirty-Year Genocide'', write that "the story about what happened in Turkey is much broader and deeper han just the Armenian genocide It's deeper because it isn't just about World War I, but about a series of homicidal ethno-religious cleansings that took place from the late 1890s to the 1920s and beyond. It is wider because the victims weren't only Armenians. Alongside hundreds of thousands of Armenians... Greeks and Assyrians... were massacred in similar numbers... We estimate that during the 30 year period that we studied between a million and a half and two and a half million Christians from all three religious groups were murdered or intentionally left for dead of starvation and sickness, and millions of others were deported and lost everything. In addition, tens of thousands of Christians were forced to convert, and many thousands of girls and women were raped by their Muslim neighbors and the security forces. The Turks even set up markets where Christian girls were sold as sex slaves. These horrendous acts were committed by three entirely different regimes: the authoritarian- Islamist regime of Sultan Abdul Hamid II, the wartime regime of the Committee of Union and Progress

The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) ( ota, اتحاد و ترقى جمعيتی, translit=İttihad ve Terakki Cemiyeti, script=Arab), later the Union and Progress Party ( ota, اتحاد و ترقى فرقهسی, translit=İttihad ve Tera ...

("The Young Turks") led by Talaat and Enver, and the nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Th ...

-secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin ''saeculum'', "worldly" or "of a generation"), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. Anything that does not have an explicit reference to religion, either negativ ...

post-war regime of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk."

Political recognition

Following an initiative of MPs of the so-called "patriotic" wing of the rulingPASOK

The Panhellenic Socialist Movement ( el, Πανελλήνιο Σοσιαλιστικό Κίνημα, Panellínio Sosialistikó Kínima, ), known mostly by its acronym PASOK, (; , ) is a social-democratic political party in Greece. Until 2012, it ...

party's parliamentary group and like-minded MPs of conservative New Democracy

New Democracy, or the New Democratic Revolution, is a concept based on Mao Zedong's Bloc of Four Social Classes theory in post-revolutionary China which argued originally that democracy in China would take a path that was decisively distinc ...

, the Greek Parliament

The Hellenic Parliament ( el, Ελληνικό Κοινοβούλιο, Elliniko Kinovoulio; formally titled el, Βουλή των Ελλήνων, Voulí ton Ellínon, Boule of the Hellenes, label=none), also known as the Parliament of the He ...

passed two laws on the fate of the Ottoman Greeks; the first in 1994 and the second in 1998. The decrees were published in the Greek ''Government Gazette'' on 8 March 1994 and 13 October 1998 respectively. The 1994 decree, created by Georgios Daskalakis, affirmed the genocide in the Pontus region of Asia Minor and designated 19 May (the day Mustafa Kemal

Mustafa ( ar, مصطفى

, Muṣṭafā) is one of the names of Prophet Muhammad, and the name means "chosen, selected, appointed, preferred", used as an Arabic given name and surname. Mustafa is a common name in the Muslim world.

Given name ...

landed in Samsun

Samsun, historically known as Sampsounta ( gr, Σαμψούντα) and Amisos (Ancient Greek: Αμισός), is a city on the north coast of Turkey and is a major Black Sea port. In 2021, Samsun recorded a population of 710,000 people. The cit ...

in 1919) a day of commemoration,. (called Pontian Greek Genocide Remembrance Day) while the 1998 decree affirmed the genocide of Greeks in Asia Minor as a whole and designated 14 September a day of commemoration.. These laws were signed by the President of Greece but were not immediately ratified after political interventions. After leftist newspaper I Avgi initiated a campaign against the application of this law, the subject became subject of a political debate. The president of the left-ecologist Synaspismos party Nikos Konstantopoulos

Nikos Konstantopoulos (; born 8 June 1942 in Krestena, Elis) is a Greek politician, member of the Hellenic Parliament and former president of the left-wing Synaspismos. His daughter, Zoi, was until September 2015 the Speaker of the Hellenic Parl ...

and historian Angelos Elefantis, known for his books on the history of Greek communism, were two of the major figures of the political left who expressed their opposition to the decree. However, the non-parliamentary left-wing nationalist intellectual and author George Karabelias bitterly criticized Elefantis and others opposing the recognition of genocide and called them "revisionist historians", accusing the Greek mainstream left of a "distorted ideological evolution". He said that for the Greek left 19 May is a "day of amnesia".

In the late 2000s the Communist Party of Greece adopted the term "Genocide of the Pontic (Greeks)" () in its official newspaper '' Rizospastis'' and participates in memorial events.

The Republic of Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ge ...

has also officially called the events "Greek Genocide in Pontus of Asia Minor".

In response to the 1998 law, the Turkish government released a statement which claimed that describing the events as genocide was "without any historical basis". "We condemn and protest this resolution" a Turkish Foreign Ministry statement said. "With this resolution the Greek Parliament, which in fact has to apologize to the Turkish people for the large-scale destruction and massacres Greece perpetrated in Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The ...

, not only sustains the traditional Greek policy of distorting history, but it also displays that the expansionist Greek mentality is still alive," the statement added..

On 11 March 2010, Sweden's Riksdag passed a motion recognising "as an act of genocide the killing of Armenians, Assyrians/Syriacs/Chaldeans and Pontic Greeks in 1915".

On 14 May 2013, the government of New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg