Poland in antiquity was characterized by peoples from various

archeological cultures living in and migrating through various parts of what is now Poland, from about 400

BC to 450–500

AD. These people are identified as

Slavs,

Celts

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancien ...

,

Germanic peoples

The Germanic peoples were historical groups of people that once occupied Central Europe and Scandinavia during antiquity and into the early Middle Ages. Since the 19th century, they have traditionally been defined by the use of ancient and e ...

,

Balts

The Balts or Baltic peoples ( lt, baltai, lv, balti) are an ethno-linguistic group of peoples who speak the Baltic languages of the Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages.

One of the features of Baltic languages is the number ...

,

Thracians

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied t ...

,

Avars, and

Scythians

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Centra ...

. Other groups, difficult to identify, were most likely also present, as the

ethnic

An ethnic group or an ethnicity is a grouping of people who identify with each other on the basis of shared attributes that distinguish them from other groups. Those attributes can include common sets of traditions, ancestry, language, history, ...

composition of archeological cultures is often poorly recognized. While lacking any written language to speak of, many of them developed a relatively advanced

material culture and

social organization

In sociology, a social organization is a pattern of relationships between and among individuals and social groups.

Characteristics of social organization can include qualities such as sexual composition, spatiotemporal cohesion, leadership, s ...

, as evidenced by the archeological record; for example, richly furnished, "princely"

dynastic

A dynasty is a sequence of rulers from the same family,''Oxford English Dictionary'', "dynasty, ''n''." Oxford University Press (Oxford), 1897. usually in the context of a monarchical system, but sometimes also appearing in republics. A d ...

grave

A grave is a location where a dead body (typically that of a human, although sometimes that of an animal) is buried or interred after a funeral. Graves are usually located in special areas set aside for the purpose of burial, such as grav ...

s.

Characteristic of the period was a high rate of

migration

Migration, migratory, or migrate may refer to: Human migration

* Human migration, physical movement by humans from one region to another

** International migration, when peoples cross state boundaries and stay in the host state for some minimum le ...

of large groups of people, even equivalents of modern nations. This article covers the continuation of the

Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age ( Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age ( Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostl ...

(see

Bronze and Iron Age Poland), the

La Tène and

Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

influence, and

Migration

Migration, migratory, or migrate may refer to: Human migration

* Human migration, physical movement by humans from one region to another

** International migration, when peoples cross state boundaries and stay in the host state for some minimum le ...

periods. The La Tène era is divided into:

* La Tène A, 450–400 BC

* La Tène B, 400–250 BC

* La Tène C, 250–150 BC

* La Tène D, 150–0 BC

400–200 BC is also considered the early pre-

Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

period,

and 200–0 BC the younger pre-Roman period (A). These eras were followed by the period of Roman influence:

* Early stage: 0–150 AD

** 0–80 B

1

** 80–150 B

2

* Late stage: 150–375 AD

** 150–250 C

1

** 250–300 C

2

** 300–375 C

3

The years 375–500 CE constituted the (pre-

Slavic)

Migration Period (D and E).

Beginning in the early 4th century BC, Celts established a number of settlement centers. Most of these were in what is now southern Poland, which was at the outer edge of their expansion. Through their highly developed

economy

An economy is an area of the production, distribution and trade, as well as consumption of goods and services. In general, it is defined as a social domain that emphasize the practices, discourses, and material expressions associated with the ...

and

crafts

A craft or trade is a pastime or an occupation that requires particular skills and knowledge of skilled work. In a historical sense, particularly the Middle Ages and earlier, the term is usually applied to people occupied in small scale prod ...

, they exerted lasting cultural influence disproportional to their small numbers in the region.

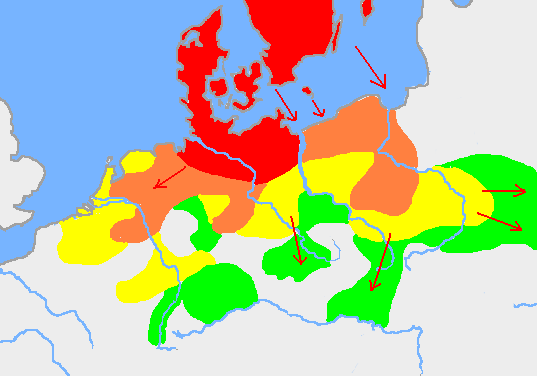

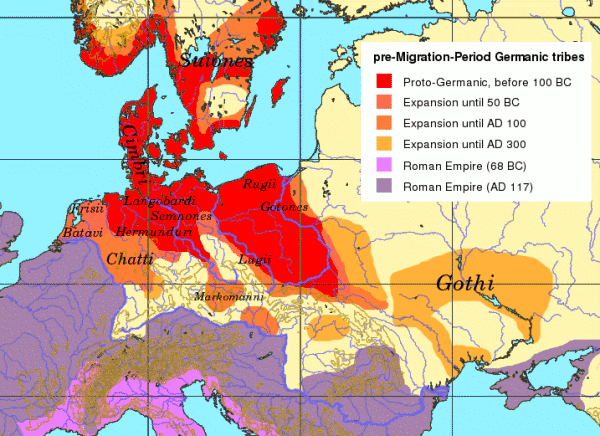

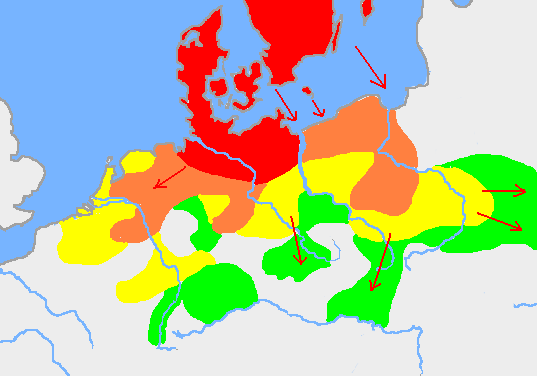

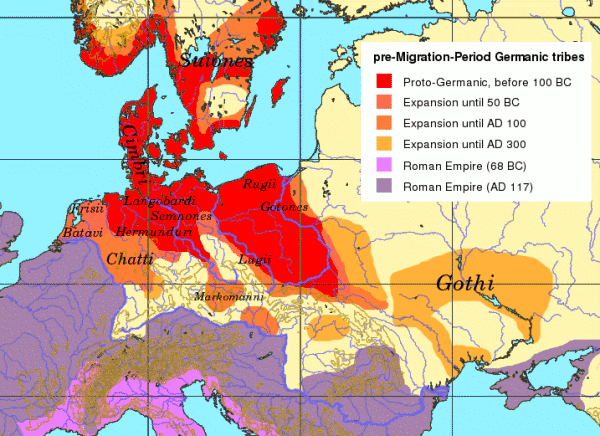

Expanding and moving out of their homeland in

Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Swe ...

and

Northern Germany,

Germanic peoples

The Germanic peoples were historical groups of people that once occupied Central Europe and Scandinavia during antiquity and into the early Middle Ages. Since the 19th century, they have traditionally been defined by the use of ancient and e ...

lived in Poland for several centuries, during which period many of their tribes also migrated outward to the south and east (see

Wielbark culture

The Wielbark culture (german: Wielbark-Willenberg-Kultur; pl, Kultura wielbarska) or East Pomeranian-Mazovian is an Iron Age archaeological complex which flourished on the territory of today's Poland from the 1st century AD to the 5th century AD. ...

). With the expansion of the Roman Empire, the Germanic tribes came under Roman cultural influence. Some written remarks by Roman authors that are relevant to the developments on Polish lands have been preserved; they give additional insight when compared with the archeological record. In the end, as the Roman Empire was nearing its collapse and the

nomad

A nomad is a member of a community without fixed habitation who regularly moves to and from the same areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the po ...

ic peoples invading from the east destroyed, damaged, or destabilized the various extant Germanic cultures and societies, the Germanic tribes left

Central and

Eastern

Eastern may refer to:

Transportation

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

*Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 1926 to 1991

*Eastern Air Li ...

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located entirel ...

for the safer and wealthier

western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

and

southern parts of the European continent.

The northeast corner of today's Poland was and remained populated by Baltic tribes. They were at the outer limits of the significant cultural influence of the Roman Empire.

Celtic peoples

Archeological cultures and groups

Celts

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancien ...

first arrived in Poland from

Bohemia and

Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The m ...

around or after 400 BC, just a few decades after their La Tène culture emerged. They formed several enclaves mostly in the south of the country, within the

Pomeranian or

Lusatian populations or in areas abandoned by those peoples. The cultures or groups that were Celtic or had a Celtic element (mixed Celtic and

autochthonous

Autochthon, autochthons or autochthonous may refer to:

Fiction

* Autochthon (Atlantis), a character in Plato's myth of Atlantis

* Autochthons, characters in the novel ''The Divine Invasion'' by Philip K. Dick

* Autochthon, a Primordial in the ...

) lasted at their furthest extent to 170 CE (

Púchov culture The Púchov culture was an archaeological culture named after site of Púchov-Skalka in Slovakia. Its probable bearer was the Celtic Cotini and/or Anartes tribes. It existed in northern and central Slovakia (although it also plausibly spread to the ...

). After the Celts appeared and during their tenure (they were always a small minority), the bulk of the population had begun acquiring the traits of

archaeological cultures with a dominant Germanic component. In Europe, the expansion of Rome and the pressures exerted by Germanic peoples checked and reversed the Celtic expansion.

Initially, two groups established themselves on fertile grounds in

Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

: one on the left bank of the

Oder River south of

Wrocław

Wrocław (; german: Breslau, or . ; Silesian German: ''Brassel'') is a city in southwestern Poland and the largest city in the historical region of Silesia. It lies on the banks of the River Oder in the Silesian Lowlands of Central Europe, rou ...

, in the area that included

Mount Ślęża

Mount is often used as part of the name of specific mountains, e.g. Mount Everest.

Mount or Mounts may also refer to:

Places

* Mount, Cornwall, a village in Warleggan parish, England

* Mount, Perranzabuloe, a hamlet in Perranzabuloe parish, ...

; the other around the

Głubczyce

Głubczyce ( cs, Hlubčice or sparsely ''Glubčice'', german: Leobschütz, Silesian German: ''Lischwitz'') is a town in Opole Voivodeship in southern Poland, near the border with the Czech Republic. It is the administrative seat of Głubczyce C ...

highlands. Both these groups stayed in their respective regions in 400–120 BC. Burials and other significant Celtic sites in Głubczyce County have been investigated in

Kietrz and nearby Nowa Cerekwia. The Ślęża group eventually assimilated into the local population, while the one in the Głubczyce highlands apparently migrated south. More-recent discoveries include Celtic settlements in

Wrocław

Wrocław (; german: Breslau, or . ; Silesian German: ''Brassel'') is a city in southwestern Poland and the largest city in the historical region of Silesia. It lies on the banks of the River Oder in the Silesian Lowlands of Central Europe, rou ...

County, such as, in Wojkowice, the well-preserved 3rd-century-BC grave of a woman with

bronze and

iron

Iron () is a chemical element with Symbol (chemistry), symbol Fe (from la, Wikt:ferrum, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 element, group 8 of the periodic table. It is, Abundanc ...

bracelet

A bracelet is an article of jewellery that is worn around the wrist. Bracelets may serve different uses, such as being worn as an ornament. When worn as ornaments, bracelets may have a supportive function to hold other items of decoration, suc ...

s,

brooch

A brooch (, also ) is a decorative jewelry item designed to be attached to garments, often to fasten them together. It is usually made of metal, often silver or gold or some other material. Brooches are frequently decorated with enamel or with g ...

es,

rings

Ring may refer to:

* Ring (jewellery), a round band, usually made of metal, worn as ornamental jewelry

* To make a sound with a bell, and the sound made by a bell

:(hence) to initiate a telephone connection

Arts, entertainment and media Film and ...

, and

chains.

Later, two more groups arrived and settled the upper

San River

The San ( pl, San; uk, Сян ''Sian''; german: Saan) is a river in southeastern Poland and western Ukraine, a tributary of the river Vistula, with a length of (it is the 6th-longest Polish river) and a basin area of 16,877 km2 (14,42 ...

basin (270–170 BC) and the

Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

area. The latter group, together with the local population that was at about that time developing the characteristics of the

Przeworsk culture

The Przeworsk culture () was an Iron Age material culture in the region of what is now Poland, that dates from the 3rd century BC to the 5th century AD. It takes its name from the town Przeworsk, near the village where the first Artifact (arch ...

(see next section), formed the mixed

Tyniec

Tyniec is a historic village in Poland on the Vistula river, since 1973 a part of the city of Kraków (currently in the district of Dębniki). Tyniec is notable for its Benedictine abbey founded by King Casimir the Restorer in 1044.

Etymology

T ...

group, which existed 270–30 BC. The Tyniec group's era of dominance was c. 80–70 BC, when the existing settlements got Celtic reinforcements from the more southerly populations that were being displaced from

Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the s ...

by the

Dacians.

In the 1st century BC, another small group settled in future Poland, probably much further north, in

Kujawy

Kuyavia ( pl, Kujawy; german: Kujawien; la, Cuiavia), also referred to as Cuyavia, is a historical region in north-central Poland, situated on the left bank of Vistula, as well as east from Noteć River and Lake Gopło. It is divided into three ...

. Finally, there was the long-lasting (270 BC–170 CE) mixed Púchov culture, whom Roman sources associated with the Celtic

Cotini The Gotini (in Tacitus), who are generally equated to the Cotini in other sources, were a Gaulish tribe living during Roman times in the mountains approximately near the modern borders of the Czech Republic, Poland,

and Slovakia.

The spelling "Got ...

, whose northern reaches included parts of the

Beskids

The Beskids or Beskid Mountains ( pl, Beskidy, cs, Beskydy, sk, Beskydy, rue, Бескиды (''Beskydŷ''), ua, Бескиди (''Beskydy'')) are a series of mountain ranges in the Carpathians, stretching from the Czech Republic in the west ...

mountain range and even the

Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

area.

Agriculture, technology, art, and trade

Ancient Celtic

agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people t ...

was advanced. Celtic

farmers used

plows

A plough or plow ( US; both ) is a farm tool for loosening or turning the soil before sowing seed or planting. Ploughs were traditionally drawn by oxen and horses, but in modern farms are drawn by tractors. A plough may have a wooden, iron or ...

with iron

shares and fertilized fields with animal

manure

Manure is organic matter that is used as organic fertilizer in agriculture. Most manure consists of animal feces; other sources include compost and green manure. Manures contribute to the Soil fertility, fertility of soil by adding organic ma ...

. Their

livestock

Livestock are the domesticated animals raised in an agricultural setting to provide labor and produce diversified products for consumption such as meat, eggs, milk, fur, leather, and wool. The term is sometimes used to refer solely to animal ...

consisted of

selected breeds, especially

sheep

Sheep or domestic sheep (''Ovis aries'') are domesticated, ruminant mammals typically kept as livestock. Although the term ''sheep'' can apply to other species in the genus '' Ovis'', in everyday usage it almost always refers to domesticated ...

and large

cattle

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, cloven-hooved, herbivores. They are a prominent modern member of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus ''Bos''. Adult females are referred to as cows and adult ma ...

.

The Celts who settled in Poland brought with them and disseminated various achievements of La Tène culture, including a variety of

tools and other inventions. One of them was the

quern-stone

Quern-stones are stone tools for hand- grinding a wide variety of materials. They are used in pairs. The lower stationary stone of early examples is called a saddle quern, while the upper mobile stone is called a muller, rubber or handstone. The ...

, which had a stationary lower stone and an upper one rotated by a lever. They also introduced iron

furnaces

A furnace is a structure in which heat is produced with the help of combustion.

Furnace may also refer to:

Appliances Buildings

* Furnace (central heating): a furnace , or a heater or boiler , used to generate heat for buildings

* Boiler, used t ...

to Poland. Iron was obtained in greater quantities from locally available

turf

Sod, also known as turf, is the upper layer of soil with the grass growing on it that is often harvested into rolls.

In Australian and British English, sod is more commonly known as ''turf'', and the word "sod" is limited mainly to agricult ...

ores; its

metallurgy and processing were improved, resulting in the manufacture of stronger and more-resistant tools and

weapon

A weapon, arm or armament is any implement or device that can be used to deter, threaten, inflict physical damage, harm, or kill. Weapons are used to increase the efficacy and efficiency of activities such as hunting, crime, law enforcement, ...

s.

Ceramic

A ceramic is any of the various hard, brittle, heat-resistant and corrosion-resistant materials made by shaping and then firing an inorganic, nonmetallic material, such as clay, at a high temperature. Common examples are earthenware, porcelain ...

-makers used the

potter's wheel

In pottery, a potter's wheel is a machine used in the shaping (known as throwing) of clay into round ceramic ware. The wheel may also be used during the process of trimming excess clay from leather-hard dried ware that is stiff but malleable, a ...

and (especially the Tyniec group) produced, with great precision, thin-walled painted vessels, among the best in Europe. Domed bilevel furnaces were used; pots were placed on a perforated

clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4).

Clays develop plasticity when wet, due to a molecular film of water surrounding the clay par ...

shelf, with the

hearth beneath. The Celts also produced

glass

Glass is a non-crystalline, often transparent, amorphous solid that has widespread practical, technological, and decorative use in, for example, window panes, tableware, and optics. Glass is most often formed by rapid cooling ( quenching ...

and

enamel, and they processed

gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile me ...

and

semi-precious stones for

jewelry

Jewellery ( UK) or jewelry ( U.S.) consists of decorative items worn for personal adornment, such as brooches, rings, necklaces, earrings, pendants, bracelets, and cufflinks. Jewellery may be attached to the body or the clothes. From a w ...

.

The Celtic communities maintained extensive trade contacts with

Greek cities,

Etruria, and then

Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

. They were involved in the

amber

Amber is fossilized tree resin that has been appreciated for its color and natural beauty since Neolithic times. Much valued from antiquity to the present as a gemstone, amber is made into a variety of decorative objects."Amber" (2004). In ...

trade between the

Baltic

Baltic may refer to:

Peoples and languages

* Baltic languages, a subfamily of Indo-European languages, including Lithuanian, Latvian and extinct Old Prussian

*Balts (or Baltic peoples), ethnic groups speaking the Baltic languages and/or originati ...

and

Adriatic seas, but

amber

Amber is fossilized tree resin that has been appreciated for its color and natural beauty since Neolithic times. Much valued from antiquity to the present as a gemstone, amber is made into a variety of decorative objects."Amber" (2004). In ...

was also worked in local shops. In the 1st century BC,

coins

A coin is a small, flat (usually depending on the country or value), round piece of metal or plastic used primarily as a medium of exchange or legal tender. They are standardized in weight, and produced in large quantities at a mint in order t ...

of gold and silver, in addition to the more common metals, were used and

minted around Kraków and elsewhere. In Gorzów near

Oświęcim

Oświęcim (; german: Auschwitz ; yi, אָשפּיצין, Oshpitzin) is a city in the Lesser Poland ( pl, Małopolska) province of southern Poland, situated southeast of Katowice, near the confluence of the Vistula (''Wisła'') and Soła rive ...

, a treasure of Celtic coins was discovered. Original

Celtic art

Celtic art is associated with the peoples known as Celts; those who spoke the Celtic languages in Europe from pre-history through to the modern period, as well as the art of ancient peoples whose language is uncertain, but have cultural and styli ...

found its expression in numerous designs that incorporated plant, animal, and

anthropomorphic motifs. These various Celtic achievements were adopted by the native populations, but usually with considerable delay.

Prominent settlements and burial sites

The settlement in

Nowa Cerekwia was active from the beginning of 4th to the end of the 2nd century BC. A hundred people lived in over 20 houses supported by

pillars

A column or pillar in architecture and structural engineering is a structural element that transmits, through compression, the weight of the structure above to other structural elements below. In other words, a column is a compression member. ...

, with walls made of

beams, finished with clay and painted. Though Celtic settlements in Poland were established at various

elevation

The elevation of a geographic location is its height above or below a fixed reference point, most commonly a reference geoid, a mathematical model of the Earth's sea level as an equipotential gravitational surface (see Geodetic datum § Ver ...

s, they had no defensive reinforcements. After the Celts abandoned the area, the Nowa Cerekiew settlement remained uninhabited for 150 years before being reoccupied by

Przeworsk people and later,

Slavs. Objects recently found at Nowa Cerekiew include a collection of gold and silver coins minted by the

Boii

The Boii (Latin plural, singular ''Boius''; grc, Βόιοι) were a Celtic tribe of the later Iron Age, attested at various times in Cisalpine Gaul ( Northern Italy), Pannonia (Hungary), parts of Bavaria, in and around Bohemia (after whom ...

tribe (3rd–2nd century BC),

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

coins from

Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

and other colonies, and various metal decorative items. Clay containers, jewelry, and tools have been recovered in the past. Nowa Cerekiew was a major Celtic trade and political center, one of the very few in central Europe, a source of great profits and the northernmost of their

Amber Road

The Amber Road was an ancient trade route for the transfer of amber from coastal areas of the North Sea and the Baltic Sea to the Mediterranean Sea. Prehistoric trade routes between Northern and Southern Europe were defined by the amber trade.

...

stations.

Among the most significant Celtic finds in

Lesser Poland

Lesser Poland, often known by its Polish name Małopolska ( la, Polonia Minor), is a historical region situated in southern and south-eastern Poland. Its capital and largest city is Kraków. Throughout centuries, Lesser Poland developed a ...

are the extensive and wealthy settlement in Podłęże and its associated cemetery in

Zakrzowiec, both in

Wieliczka

Wieliczka (German: ''Groß Salze'', Latin: ''Magnum Sal'') is a historic town in southern Poland, situated within the Kraków metropolitan area in Lesser Poland Voivodeship since 1999. The town was initially founded in 1290 by Premislaus II of ...

County; and a multi-period settlement complex in

Aleksandrowice,

Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

County. The Podłęże site was occupied from the mid-3rd century BC onward and yielded many metal objects, coins and blank

coin molds, and a large collection of glass bracelets. The Celtic graves at Zakrzowiec are dugout rectangular enclosures several meters long that contain

ash

Ash or ashes are the solid remnants of fires. Specifically, ''ash'' refers to all non-aqueous, non- gaseous residues that remain after something burns. In analytical chemistry, to analyse the mineral and metal content of chemical samples, ash ...

es and grave offerings such as

pottery

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other ceramic materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. Major types include earthenware, stoneware and ...

and personal ornaments. Graves of the same type but of a later time, 1st–2nd century CE, are also found around Kraków, demonstrating the continuation of Celtic traditions even after the arrival of Germanic tribes in the area. The Celtic burial site investigated in Aleksandrowice contains a rich 2nd-century-BC assemblage of funerary gifts, including iron weapons. The unique elaborate designs of these items, including a

scabbard

A scabbard is a sheath for holding a sword, knife, or other large blade. As well, rifles may be stored in a scabbard by horse riders. Military cavalry and cowboys had scabbards for their saddle ring carbine rifles and lever-action rifles on the ...

with a recurring

dragon motif, have been found only in the areas of Celtic settlement in

Slovenia

Slovenia ( ; sl, Slovenija ), officially the Republic of Slovenia (Slovene: , abbr.: ''RS''), is a country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the southeast, an ...

and western

Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = "Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capit ...

.

Spiritual life and cult sites

Within the realm of Celtic

spiritual life, there was considerable variation. Fourth- and early-3rd-century BC burials in Wrocław and Ślęża region are skeletal. Sometimes a man and a woman were buried together, suggesting the known Celtic practice of sacrificing a wife during her husband's funeral, but women were usually buried separately, with their jewelry. Some of the dead were given meat and a knife for cutting it. From the 3rd century BC onward, bodies were

cremated

Cremation is a method of final disposition of a dead body through burning.

Cremation may serve as a funeral or post-funeral rite and as an alternative to burial. In some countries, including India and Nepal, cremation on an open-air pyre i ...

, which was also the case in all of the Lesser Poland burials. The graves of Celtic warriors (3rd century BC) in

Iwanowice, Kraków County contain a very rich assortment of weapons and ornaments.

The Mount Ślęża formation is believed by many to have been a place of exceptional

cult significance, over many centuries, possibly going back all the way to Lusatian times, but especially for Celts. In the early 11th century,

chronicler

A chronicle ( la, chronica, from Greek ''chroniká'', from , ''chrónos'' – "time") is a historical account of events arranged in chronological order, as in a timeline. Typically, equal weight is given for historically important events and lo ...

Thietmar of Merseburg

Thietmar (also Dietmar or Dithmar; 25 July 9751 December 1018), Prince-Bishop of Merseburg from 1009 until his death, was an important chronicler recording the reigns of German kings and Holy Roman Emperors of the Ottonian (Saxon) dynasty. Two ...

describes the mountain as a place of adoration because of its size and the "cursed"

pagan ceremonies carried out there. The

summits of this and neighboring mountains are circled by

standing stones and monumental

sculpture

Sculpture is the branch of the visual arts that operates in three dimensions. Sculpture is the three-dimensional art work which is physically presented in the dimensions of height, width and depth. It is one of the plastic arts. Durable ...

s. Diagonal

cross

A cross is a geometrical figure consisting of two intersecting lines or bars, usually perpendicular to each other. The lines usually run vertically and horizontally. A cross of oblique lines, in the shape of the Latin letter X, is termed a sa ...

signs found on many of the stone objects may have their origin in the

Hallstatt

Hallstatt ( , , ) is a small town in the district of Gmunden, in the Austrian state of Upper Austria. Situated between the southwestern shore of Hallstätter See and the steep slopes of the Dachstein massif, the town lies in the Salzkammergut ...

–Lusatian solar cult. Such signs can also be seen on the massive "

monk

A monk (, from el, μοναχός, ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a person who practices religious asceticism by monastic living, either alone or with any number of other monks. A monk may be a person who decides to dedica ...

" sculpture (actually more like a simple

chess

Chess is a board game for two players, called White and Black, each controlling an army of chess pieces in their color, with the objective to checkmate the opponent's king. It is sometimes called international chess or Western chess to dist ...

figure or

skittles pin

A pin is a device used for fastening objects or material together.

Pin or PIN may also refer to:

Computers and technology

* Personal identification number (PIN), to access a secured system

** PIN pad, a PIN entry device

* PIN, a former Dutch ...

), which was located inside the largest stone ring on Mount Ślęża itself and so is believed to originate from Hallstatt cultural circles. The stone rings also contain fragments of Lusatian ceramics. The younger sculptures ("

Maiden

Virginity is the state of a person who has never engaged in sexual intercourse. The term ''virgin'' originally only referred to sexually inexperienced women, but has evolved to encompass a range of definitions, as found in traditional, modern ...

with a fish", "Mushroom," and bear figures) have distant counterparts in the Celtic art of the

Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, def ...

and are thought to be by Celts, who further developed Ślęża as a cultic center. The Mount Ślęża cult was probably revived by the

Slavs, who arrived in the early

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

.

Early Germanic peoples

La Tène and Jastorf cultures and their roles

Germanic cultures in Poland developed gradually and diversely, beginning with the extant Lusatian and Pomeranian peoples, influenced and augmented first by

La Tène Celts, and then by

Jastorf

Bad Bevensen (West Low German: ''Bemsen'') is a town in the north of the district Uelzen in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is situated to the east of the Lüneburg Heath (''Lüneburger Heide''). The Ilmenau river, a tributary of the Elbe, flows th ...

tribes, who settled northwestern Poland beginning in the 4th century BC and later migrated southeast through and past the main stretch of Polish lands (mid-3rd century BC and after). The now-disappearing Celts had greatly reshaped central Europe and left a lasting legacy. Their advanced culture catalyzed economic and other progress within the contemporary as well as future populations, which had often had little or no Celtic component. The La Tène archeological period ended as the

Common Era

Common Era (CE) and Before the Common Era (BCE) are year notations for the Gregorian calendar (and its predecessor, the Julian calendar), the world's most widely used calendar era. Common Era and Before the Common Era are alternatives to the o ...

began. The origins of the Germanic people's powerful ascent, leading them to displace the Celts, are not easy to discern. For example, we do not know to what degree Pomeranian culture gave way to

Przeworsk culture

The Przeworsk culture () was an Iron Age material culture in the region of what is now Poland, that dates from the 3rd century BC to the 5th century AD. It takes its name from the town Przeworsk, near the village where the first Artifact (arch ...

by internal evolution, external population influx, or just permeation by the new regional cultural trends.

The early Germanic Jastorf cultural sphere was in the beginning an impoverished continuation of the North German

Urnfield culture

The Urnfield culture ( 1300 BC – 750 BC) was a late Bronze Age culture of Central Europe, often divided into several local cultures within a broader Urnfield tradition. The name comes from the custom of cremating the dead and p ...

and the

Nordic circle cultures. It formed c. 700–550 BC in Northern Germany and

Jutland

Jutland ( da, Jylland ; german: Jütland ; ang, Ēota land ), known anciently as the Cimbric or Cimbrian Peninsula ( la, Cimbricus Chersonesus; da, den Kimbriske Halvø, links=no or ; german: Kimbrische Halbinsel, links=no), is a peninsula of ...

under

Hallstatt

Hallstatt ( , , ) is a small town in the district of Gmunden, in the Austrian state of Upper Austria. Situated between the southwestern shore of Hallstätter See and the steep slopes of the Dachstein massif, the town lies in the Salzkammergut ...

influence; in its early stages, its funeral customs strongly resembled those of the contemporary

Pomeranian culture

The Pomeranian culture, also Pomeranian or Pomerelian Face Urn culture was an Iron Age culture with origins in parts of the area south of the Baltic Sea (which later became Pomerania, part of northern Germany/Poland), from the 7th century BC to ...

. From the Jastorf culture, which rapidly expanded from c. 500 BC onward, two groups arose and settled the western borderlands of Poland during 300–100 BCE: The Oder group in western Pomerania and the

Gubin group further south. These groups, which were peripheral to Jastorf culture, very likely originated as Pomeranian culture populations influenced by the Jastorf cultural model. Jastorf communities established large burial grounds, separate for men and women. The dead were cremated and the ashes placed in

urns

An urn is a vase, often with a cover, with a typically narrowed neck above a rounded body and a footed pedestal. Describing a vessel as an "urn", as opposed to a vase or other terms, generally reflects its use rather than any particular shape or ...

, which were covered by

bowls turned upside down. Funeral gifts were modest and rather uniform, indicating a society that was neither affluent nor socially diversified.

The Oder and Gubin groups probably included the tribes later called

Bastarnae

The Bastarnae ( Latin variants: ''Bastarni'', or ''Basternae''; grc, Βαστάρναι or Βαστέρναι) and Peucini ( grc, Πευκῖνοι) were two ancient peoples who between 200 BC and 300 AD inhabited areas north of the Roman front ...

and

Sciri in Greek written sources, noted because of their

military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

exploits around

Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders ...

and

its colonies in the later part of the 3rd century BC. Their route followed the

Warta

The river Warta ( , ; german: Warthe ; la, Varta) rises in central Poland and meanders greatly north-west to flow into the Oder, against the German border. About long, it is Poland's second-longest river within its borders after the Vistula, a ...

and

Noteć

Noteć (; , ) is a river in central Poland with a length of (7th longest) and a basin area of .Kujawy

Kuyavia ( pl, Kujawy; german: Kujawien; la, Cuiavia), also referred to as Cuyavia, is a historical region in north-central Poland, situated on the left bank of Vistula, as well as east from Noteć River and Lake Gopło. It is divided into three ...

and

Masovia

Mazovia or Masovia ( pl, Mazowsze) is a historical region in mid-north-eastern Poland. It spans the North European Plain, roughly between Łódź and Białystok, with Warsaw being the unofficial capital and largest city. Throughout the centurie ...

, turned south along the

Bug River

uk, Західний Буг be, Захо́дні Буг

, name_etymology =

, image = Wyszkow_Bug.jpg

, image_size = 250

, image_caption = Bug River in the vicinity of Wyszków, Poland

, map = Vi ...

, and continued on to what today is

Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic alphabet, Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and for ...

, where they settled and developed the

Poienesti-Lukasevka culture.

This route is marked by archeological findings, especially the characteristic bronze

crown

A crown is a traditional form of head adornment, or hat, worn by monarchs as a symbol of their power and dignity. A crown is often, by extension, a symbol of the monarch's government or items endorsed by it. The word itself is used, partic ...

-shaped

necklaces.

Oksywie culture and Przeworsk culture

It is not clear whether, to what degree, or for what duration some of these traveling Jastorf people settled in Poland.

However, their migration, together with the accelerated La Tène influence, catalyzed the emergence of the

Oksywie

Oksywie (german: Oxhöft, csb, Òksëwiô) is a neighbourhood of the city of Gdynia, Pomeranian Voivodeship, northern Poland. Formerly a separate settlement, it is older than Gdynia by several centuries.

Etymology

Both the Polish and then Ger ...

and

Przeworsk

Przeworsk (; uk, Переворськ, translit=Perevors'k; yi, פּרשעוואָרסק, translit=Prshevorsk) is a town in south-eastern Poland with 15,675 inhabitants, as of 2 June 2009. Since 1999 it has been in the Subcarpathian Voivodeship ...

cultures. Both new cultures were under strong Jastorf influence. The increasingly common presence within the Przeworsk culture area of objects made by Jastorf people reflects the penetration of Jastorf culture into their population. Both the Oksywie and Przeworsk cultures fully used iron processing technologies; unlike their predecessor cultures, they show no regional differentiation.

Oksywie culture (250 BC–30 CE) was named after a village (now within the city of

Gdynia

Gdynia ( ; ; german: Gdingen (currently), (1939–1945); csb, Gdiniô, , , ) is a city in northern Poland and a seaport on the Baltic Sea coast. With a population of 243,918, it is the 12th-largest city in Poland and the second-largest in th ...

) where a burial site was found. It originally occupied the

Vistula

The Vistula (; pl, Wisła, ) is the longest river in Poland and the ninth-longest river in Europe, at in length. The drainage basin, reaching into three other nations, covers , of which is in Poland.

The Vistula rises at Barania Góra in ...

delta

Delta commonly refers to:

* Delta (letter) (Δ or δ), a letter of the Greek alphabet

* River delta, at a river mouth

* D ( NATO phonetic alphabet: "Delta")

* Delta Air Lines, US

* Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 that causes COVID-19

Delta may also ...

region and then the rest of eastern Pomerania, expanded west up to the Jastorf Oder group area, and in the 1st century BE also included part of what had been that group's territory. Like other cultures of this period, it had basic La Tène cultural characteristics, plus those typical of the Baltic cultures. Oksywie culture ceramics and burial customs indicate strong ties with Przeworsk culture. Men's ashes were placed in well-made black urns with a fine finish and a decorative band. Unlike men's graves in Jastorf culture, theirs were furnished with

utensils and weapons, including the typical one-edged

sword, and were often covered with or marked by stones. Women's ashes were buried in hollows with feminine personal items. A clay vessel with relief animal images found in Gołębiowo Wielkie in

Gdańsk County (2nd half of 1st century BC) is among the finest in all of the Germanic cultural zone.

Przeworsk culture

The Przeworsk culture () was an Iron Age material culture in the region of what is now Poland, that dates from the 3rd century BC to the 5th century AD. It takes its name from the town Przeworsk, near the village where the first Artifact (arch ...

was named after a town in

Lesser Poland

Lesser Poland, often known by its Polish name Małopolska ( la, Polonia Minor), is a historical region situated in southern and south-eastern Poland. Its capital and largest city is Kraków. Throughout centuries, Lesser Poland developed a ...

, near which another burial ground was found. Like Oksywie, it originated c. 250 BC, but it lasted much longer. It went through many changes, formed tribal and political structures, fought wars (including with

the Romans), until in the 5th century CE its highly developed society of farmers,

artisans,

warriors

A warrior is a person specializing in combat or warfare, especially within the context of a tribal or clan-based warrior culture society that recognizes a separate warrior aristocracies, class, or caste.

History

Warriors seem to have be ...

, and chiefs succumbed to the temptations of the lands of the now-fallen empire. (For many of them it possibly happened rather quickly, in the first half of that century.).

Przeworsk culture initially became established in

Lower Silesia

Lower Silesia ( pl, Dolny Śląsk; cz, Dolní Slezsko; german: Niederschlesien; szl, Dolny Ślōnsk; hsb, Delnja Šleska; dsb, Dolna Šlazyńska; Silesian German: ''Niederschläsing''; la, Silesia Inferior) is the northwestern part of the ...

,

Greater Poland, central Poland, and western

Masovia

Mazovia or Masovia ( pl, Mazowsze) is a historical region in mid-north-eastern Poland. It spans the North European Plain, roughly between Łódź and Białystok, with Warsaw being the unofficial capital and largest city. Throughout the centurie ...

and Lesser Poland, gradually replacing (from west to east) Pomeranian culture and

Cloche Grave culture. It coexisted with these older cultures for a while (in some cases well into the younger pre-Roman period, 200–0 BC) and assimilated some of their characteristics, such as Cloche Grave funerary practice and ceramics. The Przeworsk people must have originated from the above two local cultures, because of the lack of any other archeologically viable possibility, but their different cremation rite and pottery style represent a striking cultural discontinuity from their predecessors.

In the 2nd and 1st centuries BC (late La Tène), the Przeworsk people followed the lead of the more advanced Celts, who had established population enclaves in southern and middle Poland. Przeworsk culture developed as a result of the local populations' adoption of La Tène culture models. The passage of the Bastarnae and Sciri and the associated unrest likely functioned as the outside catalyzing agent; Jastorf culture archeological material has been found in pre-Przeworsk

artifact assemblages and in some of the early Przeworsk range. The Przeworsk people mastered and implemented the various achievements of the Celts, most importantly developing large-scale production of iron, for which they used local

bog ores.

They sometimes formed mixed groups and cooperated within common settlements with the Celts, of which the Tyniec group in the

Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

region and another group in

Kujawy

Kuyavia ( pl, Kujawy; german: Kujawien; la, Cuiavia), also referred to as Cuyavia, is a historical region in north-central Poland, situated on the left bank of Vistula, as well as east from Noteć River and Lake Gopło. It is divided into three ...

are the best-known examples.

Arms

Arms or ARMS may refer to:

*Arm or arms, the upper limbs of the body

Arm, Arms, or ARMS may also refer to:

People

* Ida A. T. Arms (1856–1931), American missionary-educator, temperance leader

Coat of arms or weapons

*Armaments or weapons

**Fi ...

,

clothes, and ornaments were patterned after Celtic products. In the early stages of their culture, the Przeworsk people displayed no social distinctions; their graves were alike and flat, and ashes were usually buried together with funeral gifts and without urns. Religious practices of pagan Germanic peoples included offering ceremonies performed in

swamps, involving manmade objects,

produce

Produce is a generalized term for many farm-produced crops, including fruits and vegetables (grains, oats, etc. are also sometimes considered ''produce''). More specifically, the term ''produce'' often implies that the products are fresh and g ...

, farm animals, or even

human sacrifice

Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease gods, a human ruler, an authoritative/priestly figure or spirits of dead ancestors or as a retainer sacrifice, wherein ...

, as was the case at one site near Słowikowo in

Słupca

Słupca is a town in Greater Poland Voivodeship, central Poland, and the seat of Słupca County. It has 13,773 inhabitants (2018).

History

History of Słupca dates back to the Middle Ages. On November 15, 1290 Polish Duke Przemysł II granted ...

County and another in Otalążka,

Grójec

Grójec is a town in Poland, located in the Masovian Voivodeship, about south of Warsaw. It is the capital of the urban-rural administrative district Grójec and Grójec County. It has 16,674 inhabitants (2017). Grójec surroundings are consid ...

County. Dog burials within or around a

homestead

Homestead may refer to:

*Homestead (buildings), a farmhouse and its adjacent outbuildings; by extension, it can mean any small cluster of houses

* Homestead (unit), a unit of measurement equal to 160 acres

*Homestead principle, a legal concept t ...

were another form of protective offering.

As the Celtic domination in this part of Europe was coming to an end and the Roman Empire's borders had gotten much closer, the Przeworsk people were being subjected to the

Greco-Roman world's influence with a rapidly growing intensity.

Cultures and tribes in Roman times

Early Roman wars and movement of tribes

Much circumstantial evidence points to the participation of Germanic people from Polish lands in the events of the first half of the 1st century BCE, which culminated in

Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

in 58 BCE, as related in

Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

's ''

Commentarii de Bello Gallico

''Commentarii de Bello Gallico'' (; en, Commentaries on the Gallic War, italic=yes), also ''Bellum Gallicum'' ( en, Gallic War, italic=yes), is Julius Caesar's firsthand account of the Gallic Wars, written as a third-person narrative. In it C ...

''. At the time the

Suebi tribal

confederation

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a union of sovereign groups or states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

led by

Ariovistus arrived in Gaul, a rapid decrease of settlement density can be observed in the areas of the upper and middle Oder

River basin

A drainage basin is an area of land where all flowing surface water converges to a single point, such as a river mouth, or flows into another body of water, such as a lake or ocean. A basin is separated from adjacent basins by a perimeter, t ...

. In fact, the Gubin group of Jastorf culture then disappeared entirely, which may indicate that the group identified with one of the Suebi tribes. Also vacated were the western areas of Przeworsk culture (Lower Silesia,

Lubusz Land

Lubusz Land ( pl, Ziemia lubuska; german: Land Lebus) is a historical region and cultural landscape in Poland and Germany on both sides of the Oder river.

Originally the settlement area of the Lechites, the swampy area was located east of Branden ...

and western Greater Poland), the probable original territory of the tribes accompanying the Suebi. Burial sites and artifacts characteristic of Przeworsk culture have been found in

Saxony

Saxony (german: Sachsen ; Upper Saxon: ''Saggsn''; hsb, Sakska), officially the Free State of Saxony (german: Freistaat Sachsen, links=no ; Upper Saxon: ''Freischdaad Saggsn''; hsb, Swobodny stat Sakska, links=no), is a landlocked state of ...

,

Thuringia

Thuringia (; german: Thüringen ), officially the Free State of Thuringia ( ), is a state of central Germany, covering , the sixth smallest of the sixteen German states. It has a population of about 2.1 million.

Erfurt is the capital and lar ...

, and

Hesse

Hesse (, , ) or Hessia (, ; german: Hessen ), officially the State of Hessen (german: links=no, Land Hessen), is a state in Germany. Its capital city is Wiesbaden, and the largest urban area is Frankfurt. Two other major historic cities are Dar ...

, along the route of the Suebi

offensive. The abovementioned regions of western Poland were not repopulated and economically redeveloped until the 2nd century CE.

As a result of the Roman efforts to subjugate all of

Germania, the member tribes of the Suebi alliance were displaced, moved east, conquered the Celtic tribes who stood in their way, and settled: the

Quadi in

Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The m ...

, the

Marcomanni

The Marcomanni were a Germanic people

*

*

*

that established a powerful kingdom north of the Danube, somewhere near modern Bohemia, during the peak of power of the nearby Roman Empire. According to Tacitus and Strabo, they were Suebian.

Or ...

in

Bohemia. The latter tribe, under

Marbod

Maroboduus (d. AD 37) was a king of the Marcomanni, who were a Germanic Suebian people. He spent part of his youth in Rome, and returning, found his people under pressure from invasions by the Roman empire between the Rhine and Elbe. He led th ...

, formed a quasi-state with a huge

army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

and was able to conquer, among others, the

Lugii

The Lugii (or ''Lugi'', ''Lygii'', ''Ligii'', ''Lugiones'', ''Lygians'', ''Ligians'', ''Lugians'', or ''Lougoi'') were a large tribal confederation mentioned by Roman authors living in ca. 100 BC–300 AD in Central Europe, north of the Sude ...

tribal association. What archeologists see as the Przeworsk culture by this period (early 1st century CE) is believed to consist primarily of the Lugii, described by

Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his two major works—the ...

as a very large union of tribes. The Roman defeat at the

Battle of the Teutoburg Forest

The Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, described as the Varian Disaster () by Roman historians, took place at modern Kalkriese in AD 9, when an alliance of Germanic peoples ambushed Roman legions and their auxiliaries, led by Publius Quinctilius ...

(9 CE) stabilized the situation at the periphery of the Empire to some degree. Through Marcomanni and Quadi intermediaries, the Lugii and other tribes on Polish lands increasingly became involved in trade and other contacts with the Danubian provinces of Rome. In 50 CE they invaded and pillaged the Quadi state created by

Vannius

Vainius (flourished in 1st century AD) was the king of the Germanic tribe Quadi.

According to The Annals of Tacitus, Vannius came to power following the defeat of the Marcomannic king Catualda by the Hermunduri king of Vibilius, establishing t ...

, contributing to its fall. The catalyst for the expedition was rumors of the enormous riches that Vannius had accumulated by

plunder and by charging

duties

A duty (from "due" meaning "that which is owing"; fro, deu, did, past participle of ''devoir''; la, debere, debitum, whence "debt") is a commitment or expectation to perform some action in general or if certain circumstances arise. A duty may ...

. In 93 CE the Lugii, asked Emperor

Domitian

Domitian (; la, Domitianus; 24 October 51 – 18 September 96) was a Roman emperor who reigned from 81 to 96. The son of Vespasian and the younger brother of Titus, his two predecessors on the throne, he was the last member of the Fl ...

for help in their war against the Suebi and received 100 mounted soldiers.

Amber Road

Operations of the ancient

Amber Road

The Amber Road was an ancient trade route for the transfer of amber from coastal areas of the North Sea and the Baltic Sea to the Mediterranean Sea. Prehistoric trade routes between Northern and Southern Europe were defined by the amber trade.

...

, a trans-European, north–south

amber

Amber is fossilized tree resin that has been appreciated for its color and natural beauty since Neolithic times. Much valued from antiquity to the present as a gemstone, amber is made into a variety of decorative objects."Amber" (2004). In ...

trade route, continued and intensified during the Roman Empire. From the 1st century BCE the Amber Road connected the Baltic Sea shores and

Aquileia, an important amber processing center. This route was controlled first by the Celts, later by the Romans south of the

Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , p ...

, and then by Germanic tribes north of that river. It was used for transporting a variety of traded merchandise (and slaves) besides amber. As told in ''

Naturalis Historia

The ''Natural History'' ( la, Naturalis historia) is a work by Pliny the Elder. The largest single work to have survived from the Roman Empire to the modern day, the ''Natural History'' compiles information gleaned from other ancient authors. ...

'' by

Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ' ...

, during the reign of

Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68), was the fifth Roman emperor and final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 unti ...

an

equestrian

The word equestrian is a reference to equestrianism, or horseback riding, derived from Latin ' and ', "horse".

Horseback riding (or Riding in British English)

Examples of this are:

* Equestrian sports

*Equestrian order, one of the upper classes i ...

of unknown name led an expedition to the Baltic shorelines and returned to Rome with huge quantity of amber, which was subsequently used for

propagandist purposes during

gladiator matches and other public games. The infrastructure of the Amber Road was destroyed by Germanic and

Sarmatian

The Sarmatians (; grc, Σαρμαται, Sarmatai; Latin: ) were a large confederation of ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic peoples of classical antiquity who dominated the Pontic steppe from about the 3rd century BC to the 4th cen ...

attacks in the second half of the 3rd century CE, although it was still intermittently used until the mid-6th century. The Przeworsk culture sites provide a rich assortment of objects traded along the Amber Road.

Gustow and Lubusz groups

From the beginning of the Common Era until 140 CE, two local groups existed in northwest Poland. The

Gustow group The Gustow group (german: Gustow Gruppe or ''Gustower Gruppe'', pl, grupa gustowska) is an archaeological culture of the Roman Iron Age in Western Pomerania. The Gustow group is associated with the Germanic tribe of the Rugii.

Since the second h ...

(named after Gustow on

Rügen

Rügen (; la, Rugia, ) is Germany's largest island. It is located off the Pomeranian coast in the Baltic Sea and belongs to the state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania.

The "gateway" to Rügen island is the Hanseatic city of Stralsund, where ...

) lived in the area settled in the past by the Oder group. To the south, by the middle section of the Oder River (the area previously inhabited by the Gubin group), lived the

Lubusz group. These two groups were intermediary between the

Elbe

The Elbe (; cs, Labe ; nds, Ilv or ''Elv''; Upper and dsb, Łobjo) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Re ...

cultural circle to the west and the Przeworsk and

Wielbark cultures to the east (Wielbark replaced Oksywie culture after 30 CE).

Przeworsk culture settlements and burial sites

The Przeworsk people of the earlier Roman period lived in small, unprotected villages. Each village had a few dozen residents at most, living in several houses, each of which covered an area of 8–22

m2 and was usually set partly below ground level (semi-

sunken). Because Przeworsk people had

well

A well is an excavation or structure created in the ground by digging, driving, or drilling to access liquid resources, usually water. The oldest and most common kind of well is a water well, to access groundwater in underground aquifers. The ...

s, settlements did not need to be near bodies of water. Thirteen 2nd-century-CE wells of various construction with timber-lined walls have been found at a settlement in

Stanisławice,

Bochnia

Bochnia (german: Salzberg) is a town on the river Raba in southern Poland. The town lies approximately halfway between Tarnów (east) and the regional capital Kraków (west). Bochnia is most noted for its salt mine, the oldest functioning i ...

County.

Fields were used for crop cultivation for a while and then as pastures, as animal

manure

Manure is organic matter that is used as organic fertilizer in agriculture. Most manure consists of animal feces; other sources include compost and green manure. Manures contribute to the Soil fertility, fertility of soil by adding organic ma ...

helped refertilize the depleted soil. Once iron plowshares were introduced, Przeworsk fields alternated between

tillage

Tillage is the agricultural preparation of soil by mechanical agitation of various types, such as digging, stirring, and overturning. Examples of human-powered tilling methods using hand tools include shoveling, picking, mattock work, hoein ...

and

grazing

In agriculture, grazing is a method of animal husbandry whereby domestic livestock are allowed outdoors to roam around and consume wild vegetations in order to convert the otherwise indigestible (by human gut) cellulose within grass and other ...

.

Several or more settlements made up a micro-region within which the residents cooperated economically and buried their dead in a common cemetery. Each micro-region was separated from other micro-regions by

forest

A forest is an area of land dominated by trees. Hundreds of definitions of forest are used throughout the world, incorporating factors such as tree density, tree height, land use, legal standing, and ecological function. The United Nations' ...

s and barren land. A number of such micro-regions possibly made up a tribe, with tribes separated by empty space, which

Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his two major works—the ...

called zones "of mutual fear." However, tribes would at times form larger confederations, such as temporary alliances for waging wars or even early forms of states, especially if they were culturally closely related.

A Przeworsk culture turn-of-the-

millennium

A millennium (plural millennia or millenniums) is a period of one thousand years, sometimes called a kiloannum (ka), or kiloyear (ky). Normally, the word is used specifically for periods of a thousand years that begin at the starting point (ini ...

industrial complex for the extraction of salt from

salt springs was discovered in

Chabsko near

Mogilno

Mogilno (; ) is a town in central Poland, situated in the Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship (since 1999), previously in Bydgoszcz Voivodeship (1975–1998).

History

Mogilno is one of the oldest settlements along the border of the Greater Poland an ...

.

Examinations of Przeworsk burial grounds, of which even the largest was used continuously over periods of up to several centuries, have turned up no more than several hundred graves, showing that overall population density was low.

The dead were cremated and the ashes sometimes placed into urns with central engraved bulges. In the 1st century CE, this design was replaced with a horizontal ridge around the circumference of the urn, which produced a sharp profile.

In Siemiechów, a grave of a warrior who must have taken part in the

Ariovistus expedition (70–50 BC) was found; it contains Celtic weapons, a helmet manufactured in the

Alpine

Alpine may refer to any mountainous region. It may also refer to:

Places Europe

* Alps, a European mountain range

** Alpine states, which overlap with the European range

Australia

* Alpine, New South Wales, a Northern Village

* Alpine National Pa ...

region that was used as the warrior's burial urn, and local ceramics. Burial gifts were often, for unknown reasons, bent or broken and then burned with the body. The burials range from "poor" to "rich," the latter supplied with costly Celtic and then Roman

imports, reflecting the considerable social stratification that had developed by then.

Wielbark culture and burials

Wielbark culture

The Wielbark culture (german: Wielbark-Willenberg-Kultur; pl, Kultura wielbarska) or East Pomeranian-Mazovian is an Iron Age archaeological complex which flourished on the territory of today's Poland from the 1st century AD to the 5th century AD. ...

, named after

Wielbark in

Malbork County where a large cemetery was found, replaced

Oksywie culture

The Oksywie culture (German ') was an archaeological culture that existed in the area of modern-day Eastern Pomerania around the lower Vistula river from the 2nd century BC to the early 1st century AD. It is named after the village of Oksywie, ...

in Pomerania rather suddenly across its entire territory.

While Oksywie culture was closely related to Przeworsk culture, its successor Wielbark culture shows only minimal contacts with the Przeworsk areas, indicating clear tribal and geographical separation. Wielbark culture lasted on Polish lands from 30 to 400 CE, although most of its people left Poland long before the latter date. Some of this culture's burials are skeletal; the dead were inhumed in solid log

coffins

A coffin is a funerary box used for viewing or keeping a corpse, either for burial or cremation.

Sometimes referred to as a casket, any box in which the dead are buried is a coffin, and while a casket was originally regarded as a box for jewe ...

, while others were cremated; both such graves were identically equipped.

Cremated remains were either placed in urns or simply buried in hollows. Burial gifts did not include weapons or tools. They did include clay vessels, decorations, personal ornaments, and — if the deceased had been wealthy enough to own a horse — spurs. These various items, and especially the 1st and 2nd century CE jewelry made of bronze, silver, and gold, are works of the highest quality, surpassing the comparable products of the Przeworsk culture. This craftsmanship reached its apex with 2nd-century "

Baroque" jewelry, beautiful by any standard, that was placed in the graves of women in (as the Wielbark culture expanded south)

Poznań

Poznań () is a city on the River Warta in west-central Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business centre, and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint Joh ...

Szeląg and Kowalewko,

Oborniki

Oborniki (german: Obornik) is a town in Poland, in Greater Poland Voivodeship, about 30 km north of Poznań. It is the capital of Oborniki County and of Gmina Oborniki. Its population is 18,176 (2005).

History

Oborniki was granted town ri ...

County, among other places.

The Kowalewko cemetery in

Greater Poland is one of the largest Wielbark burial sites in Poland and is distinguished by a great number of beautiful relics, made locally or imported from the Empire. The total number of burials is estimated to exceed 500, most of which have been excavated. Sixty percent of bodies were not cremated but were typically placed in wooden coffins made of boards or planks. The burial ground was in use from the mid-1st century CE to about 220, meaning that approximately 80 local residents of each generation were inhumed there. Remnants of settlements in the region have also been investigated.

At Rogowo near

Chełmno

Chełmno (; older en, Culm; formerly ) is a town in northern Poland near the Vistula river with 18,915 inhabitants as of December 2021. It is the seat of the Chełmno County in the Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship.

Due to its regional impor ...

, a Wielbark settlement, an industrial production site and a 2nd-to-3rd-century bi-ritual cemetery with very richly furnished graves have been discovered.

In the area of Ulkowy,

Gdańsk County, a settlement consisting of sunken floors and post-construction dwellings has been found, as well as a burial ground in use from the mid-1st century to the second half of the 3rd century. Only part of the cemetery was excavated on the occasion of a motorway construction, but it yielded 110 inhumations (11 in hollowed-out log coffins) and 15 cremations (eight of them in urns) with a rich collection of decorative objects, mostly from the graves of women. Those include fancy jewelry and accessories made of gold, silver, bronze, amber, glass, and enamel. Ceramics, utility items, and tools, including

weaving

Weaving is a method of textile production in which two distinct sets of yarns or threads are interlaced at right angles to form a fabric or cloth. Other methods are knitting, crocheting, felting, and braiding or plaiting. The longitudinal ...

equipment, were recovered from the settlement site. Other significant Wielbark settlements in the area were encountered in Swarożyn and Stanisławie, both in

Tczew

Tczew (, csb, Dërszewò; formerly ) is a city on the Vistula River in Eastern Pomerania, Kociewie, northern Poland with 59,111 inhabitants (December 2021). The city is known for its Old Town and the Vistula Bridge, or Bridge of Tczew, which pl ...

County.

[''Archaeological Rescue Excavations'' by Mirosław Fudziński and Henryk Paner, ''Archeologia Żywa'' (Living Archeology), special English issue 2005][Museum of Archeology in Gdańsk web site]

Many Wielbark graves were flat, but

kurgan

A kurgan is a type of tumulus constructed over a grave, often characterized by containing a single human body along with grave vessels, weapons and horses. Originally in use on the Pontic–Caspian steppe, kurgans spread into much of Central As ...

s are also characteristic and common. In the case of kurgans, the grave was covered with stones, which were surrounded by a circle of larger stones. These were covered with earth and a solitary stone or

stela

A stele ( ),Anglicized plural steles ( ); Greek plural stelai ( ), from Greek , ''stēlē''. The Greek plural is written , ''stēlai'', but this is only rarely encountered in English. or occasionally stela (plural ''stelas'' or ''stelæ''), wh ...

often put on top. Such a kurgan could include one or several individual burials, have a diameter of up to a dozen or so meters, and be up to 1 meter high. Some burial grounds feature large

stone circles

A stone circle is a ring of standing stones. Most are found in Northwestern Europe – especially in Britain, Ireland, and Brittany – and typically date from the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age, with most being built from 3000 BC. The b ...

of massive boulders up to 1.7 meters high, separated by several meters of spaces, sometimes connected by smaller stones; the whole structure is 10–40 meters in diameter. In the middle of the circles, one to four stelae were placed, and sometimes a single grave. The stone circles are believed to be the locations of meetings of Scandinavian (see below)

tings (assemblies or courts). The single graves inside the circles are probably those of human sacrifices meant to propitiate the

gods

A deity or god is a supernatural being who is considered divine or sacred. The ''Oxford Dictionary of English'' defines deity as a god or goddess, or anything revered as divine. C. Scott Littleton defines a deity as "a being with powers greater ...

and assure their support for the deliberations. A stone kurgan cemetery was found in Węsiory,

Kartuzy

Kartuzy () ( Kashubian ''Kartuzë'', ''Kartëzë'', or ''Kartuzé''; formerly german: Karthaus) is a town in northern Poland, located in the historic Eastern Pomerania ( Pomerelia) region. It is the capital of Kartuzy County in Pomeranian Voivode ...

County; another burial site with 10 large stone circles was discovered in Odry,

Chojnice

Chojnice (; , or ''Chòjnice''; german: Konitz or ''Conitz'') is a town in northern Poland with 39,423 inhabitants as of December 2021, near the Tuchola Forest. It is the capital of the Chojnice County in the Pomeranian Voivodeship.

History

Pias ...

County, both dated 2nd century CE.

Origins and expansion of the Wielbark culture

How did Wielbark culture arise, and why did it so immediately replace Oksywie culture? According to the legend quoted in ''

The Origin and Deeds of the Goths

''De origine actibusque Getarum'' (''The Origin and Deeds of the Getae oths'), commonly abbreviated ''Getica'', written in Late Latin by Jordanes in or shortly after 551 AD, claims to be a summary of a voluminous account by Cassiodorus of the o ...

'' by the 6th-century

Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

historian

Jordanes